- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Self-Esteem?

Your Sense of Your Personal Worth or Value

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Verywell / Brianna Gilmartin

Theories of Self-Esteem

Healthy self-esteem, low self-esteem, excessive self-esteem.

- How to Improve

Self-esteem is your subjective sense of overall personal worth or value. Similar to self-respect, it describes your level of confidence in your abilities and attributes.

Having healthy self-esteem can influence your motivation, your mental well-being, and your overall quality of life. However, having self-esteem that is either too high or too low can be problematic. Better understanding what your unique level of self-esteem is can help you strike a balance that is just right for you.

Key elements of self-esteem include:

- Self-confidence

- Feelings of security

- Sense of belonging

- Feeling of competence

Other terms often used interchangeably with self-esteem include self-worth, self-regard, and self-respect.

Self-esteem tends to be lowest in childhood and increases during adolescence, as well as adulthood, eventually reaching a fairly stable and enduring level. This makes self-esteem similar to the stability of personality traits over time.

Why Self-Esteem Is Important

Self-esteem impacts your decision-making process, your relationships, your emotional health, and your overall well-being. It also influences motivation , as people with a healthy, positive view of themselves understand their potential and may feel inspired to take on new challenges.

Four key characteristics of healthy self-esteem are:

- A firm understanding of one's skills

- The ability to maintain healthy relationships with others as a result of having a healthy relationship with oneself

- Realistic and appropriate personal expectations

- An understanding of one's needs and the ability to express those needs

People with low self-esteem tend to feel less sure of their abilities and may doubt their decision-making process. They may not feel motivated to try novel things because they don’t believe they can reach their goals. Those with low self-esteem may have issues with relationships and expressing their needs. They may also experience low levels of confidence and feel unlovable and unworthy.

People with overly high self-esteem may overestimate their skills and may feel entitled to succeed, even without the abilities to back up their belief in themselves. They may struggle with relationship issues and block themselves from self-improvement because they are so fixated on seeing themselves as perfect .

Click Play to Learn More About Self-Esteem

This video has been medically reviewed by Rachel Goldman, PhD, FTOS .

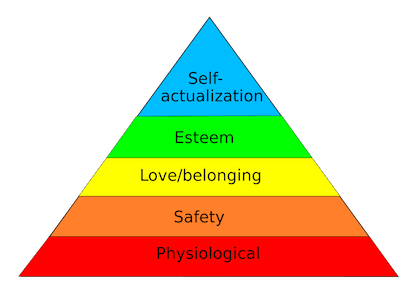

Many theorists have written about the dynamics involved in the development of self-esteem. The concept of self-esteem plays an important role in psychologist Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs , which depicts esteem as one of the basic human motivations.

Maslow suggested that individuals need both appreciation from other people and inner self-respect to build esteem. Both of these needs must be fulfilled in order for an individual to grow as a person and reach self-actualization .

It is important to note that self-esteem is a concept distinct from self-efficacy , which involves how well you believe you'll handle future actions, performance, or abilities.

Factors That Affect Self-Esteem

There are many factors that can influence self-esteem. Your self-esteem may be impacted by:

- Physical abilities

- Socioeconomic status

- Thought patterns

Racism and discrimination have also been shown to have negative effects on self-esteem. Additionally, genetic factors that help shape a person's personality can play a role, but life experiences are thought to be the most important factor.

It is often our experiences that form the basis for overall self-esteem. For example, low self-esteem might be caused by overly critical or negative assessments from family and friends. Those who experience what Carl Rogers referred to as unconditional positive regard will be more likely to have healthy self-esteem.

There are some simple ways to tell if you have healthy self-esteem. You probably have healthy self-esteem if you:

- Avoid dwelling on past negative experiences

- Believe you are equal to everyone else, no better and no worse

- Express your needs

- Feel confident

- Have a positive outlook on life

- Say no when you want to

- See your overall strengths and weaknesses and accept them

Having healthy self-esteem can help motivate you to reach your goals, because you are able to navigate life knowing that you are capable of accomplishing what you set your mind to. Additionally, when you have healthy self-esteem, you are able to set appropriate boundaries in relationships and maintain a healthy relationship with yourself and others.

Low self-esteem may manifest in a variety of ways. If you have low self-esteem:

- You may believe that others are better than you.

- You may find expressing your needs difficult.

- You may focus on your weaknesses.

- You may frequently experience fear, self-doubt, and worry.

- You may have a negative outlook on life and feel a lack of control.

- You may have an intense fear of failure.

- You may have trouble accepting positive feedback.

- You may have trouble saying no and setting boundaries.

- You may put other people's needs before your own.

- You may struggle with confidence .

Low self-esteem has the potential to lead to a variety of mental health disorders, including anxiety disorders and depressive disorders. You may also find it difficult to pursue your goals and maintain healthy relationships. Having low self-esteem can seriously impact your quality of life and increases your risk for experiencing suicidal thoughts.

If you are having suicidal thoughts, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

Overly high self-esteem is often mislabeled as narcissism , however there are some distinct traits that differentiate these terms. Individuals with narcissistic traits may appear to have high self-esteem, but their self-esteem may be high or low and is unstable, constantly shifting depending on the given situation. Those with excessive self-esteem:

- May be preoccupied with being perfect

- May focus on always being right

- May believe they cannot fail

- May believe they are more skilled or better than others

- May express grandiose ideas

- May grossly overestimate their skills and abilities

When self-esteem is too high, it can result in relationship problems, difficulty with social situations, and an inability to accept criticism.

How to Improve Self-Esteem

Fortunately, there are steps that you can take to address problems with your perceptions of yourself and faith in your abilities. How do you build self-esteem? Some actions that you can take to help improve your self-esteem include:

- Become more aware of negative thoughts . Learn to identify the distorted thoughts that are impacting your self-worth.

- Challenge negative thinking patterns . When you find yourself engaging in negative thinking, try countering those thoughts with more realistic and/or positive ones.

- Use positive self-talk . Practice reciting positive affirmations to yourself.

- Practice self-compassion . Practice forgiving yourself for past mistakes and move forward by accepting all parts of yourself.

Low self-esteem can contribute to or be a symptom of mental health disorders, including anxiety and depression . Consider speaking with a doctor or therapist about available treatment options, which may include psychotherapy (in-person or online), medications, or a combination of both.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, Betterhelp, and Regain. Find out which option is the best for you.

Though some of the causes of low self-esteem can’t be changed, such as genetic factors, early childhood experiences, and personality traits, there are steps you can take to feel more secure and valued. Remember that no one person is less worthy than the next. Keeping this in mind may help you maintain a healthy sense of self-esteem.

Get Advice From The Verywell Mind Podcast

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares strategies that can help you learn to truly believe in yourself, featuring IT Cosmetics founder Jamie Kern Lima.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

Trzesniewski KH, Donnellan MB, Robins RW. Stability of self-esteem across the life span . J Pers Soc Psychol . 2003;84(1):205-220.

von Soest T, Wagner J, Hansen T, Gerstorf D. Self-esteem across the second half of life: The role of socioeconomic status, physical health, social relationships, and personality factors . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology . 2018;114(6):945-958. doi:10.1037/pspp0000123

Johnson AJ. Examining associations between racism, internalized shame, and self-esteem among African Americans . Cogent Psychology . 2020;7(1):1757857. doi:10.1080/23311908.2020.1757857

Gabriel AS, Erickson RJ, Diefendorff JM, Krantz D. When does feeling in control benefit well-being? The boundary conditions of identity commitment and self-esteem. Journal of Vocational Behavior . 2020;119:103415. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103415

Nguyen DT, Wright EP, Dedding C, Pham TT, Bunders J. Low self-esteem and its association with anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation in Vietnamese secondary school students: A cross-sectional study . Front Psychiatry . 2019;10:698. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00698

Brummelman E, Thomaes S, Sedikides C. Separating narcissism from self-esteem. Curr Dir Psychol Sci . 2016;25(1):8-13. doi:10.1177/0963721415619737

Cascio CN, O’Donnell MB, Tinney FJ, Lieberman MD, Taylor SE, Stretcher VJ, et. al. Self-affirmation activates brain systems associated with self-related processing and reward and is reinforced by future orientation . Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience . 2016;11(4):621-629. doi:10.1093/scan/nsv136

Maslow AH. Motivation and Personality . 3rd ed. New York: Harper & Row; 1987.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

What is Self-Esteem? A Psychologist Explains

“Believe in yourself.”

That is the message that we encounter constantly, in books, television shows, superhero comics, and common myths and legends.

We are told that we can accomplish anything if we believe in ourselves.

Of course, we know that to be untrue; we cannot accomplish anything in the world simply through belief—if that were true, a lot more children would be soaring in the skies above their garage roof instead of lugging around a cast for a few weeks!

However, we know that believing in yourself and accepting yourself for who you are is an important factor in success, relationships, and happiness and that self-esteem plays an important role in living a flourishing life . It provides us with belief in our abilities and the motivation to carry them out, ultimately reaching fulfillment as we navigate life with a positive outlook.

Various studies have confirmed that self-esteem has a direct relationship with our overall wellbeing, and we would do well to keep this fact in mind—both for ourselves and for those around us, particularly the developing children we interact with.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Self-Compassion Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will not only help you show more compassion to yourself but will also give you the tools to enhance the self-compassion of your clients, students or employees and lead them to a healthy sense of self-esteem.

This Article Contains:

- What is the Meaning of Self-esteem? A Definition

Self-Esteem and Psychology

Incorporating self-esteem in positive psychology, 22 examples of high self-esteem, 18 surprising statistics and facts about self-esteem, relevant research, can we help boost self-esteem issues with therapy and counseling, the benefits of developing self-esteem with meditation, can you test self-esteem, and what are the problems with assessment, 17 factors that influence self-esteem, the effects of social media, 30 tips & affirmations for enhancing self-esteem, popular books on self-esteem (pdf), ted talks and videos on self-esteem, 15 quotes on self-esteem, a take-home message, what is the meaning of self-esteem.

You probably already have a good idea, but let’s start from the beginning anyway: what is self-esteem?

Self-esteem refers to a person’s overall sense of his or her value or worth. It can be considered a sort of measure of how much a person “values, approves of, appreciates, prizes, or likes him or herself” (Adler & Stewart, 2004).

According to self-esteem expert Morris Rosenberg, self-esteem is quite simply one’s attitude toward oneself (1965). He described it as a “favourable or unfavourable attitude toward the self”.

Various factors believed to influence our self-esteem include:

- Personality

- Life experiences

- Social circumstances

- The reactions of others

- Comparing the self to others

An important note is that self-esteem is not fixed. It is malleable and measurable, meaning we can test for and improve upon it.

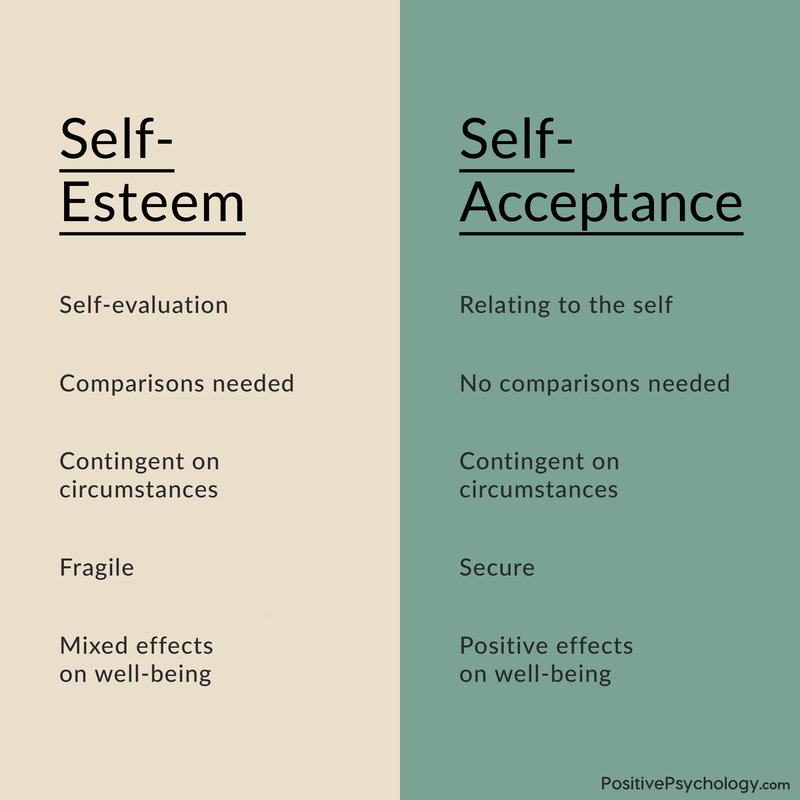

Self-esteem and self-acceptance are often confused or even considered identical by most people. Let’s address this misconception by considering some fundamental differences in the nature and consequences of self-esteem and unconditional self-acceptance.

- Self-esteem is based on evaluating the self, and rating one’s behaviors and qualities as positive or negative, which results in defining the self as worthy or non-worthy (Ellis, 1994).

- Self-acceptance, however, is how the individual relates to the self in a way that allows the self to be as it is. Acceptance is neither positive nor negative; it embraces all aspects and experiences of the self (Ellis, 1976).

- Self-esteem relies on comparisons to evaluate the self and ‘decide’ its worth.

- Self-acceptance, stems from the realization that there is no objective basis for determining the value of a human being. So with self-acceptance, the individual affirms who they are without any need for comparisons.

- Self-esteem is contingent on external factors, such as performance, appearance, or social approval, that form the basis on which the self is evaluated.

- With self-acceptance, a person feels satisfied with themselves despite external factors, as this sense of worthiness is not derived from meeting specific standards.

- Self-esteem is fragile (Kernis & Lakey, 2010).

- Self-acceptance provides a secure and enduring positive relationship with the self (Kernis & Lakey, 2010).

- When it comes to the consequences on wellbeing, while self-esteem appears to be associated with some markers of wellbeing, such as high life satisfaction (Myers & Diener, 1995) and less anxiety (Brockner, 1984), there is also a “dark side” of self-esteem, characterized by egotism and narcissism (Crocker & Park, 2003).

- Self-acceptance is strongly associated with numerous positive markers of general psychological wellbeing (MacInnes, 2006).

Self-esteem has been a hot topic in psychology for decades, going about as far back as psychology itself. Even Freud , who many consider the founding father of psychology (although he’s a bit of an estranged father at this point), had theories about self-esteem at the heart of his work.

What self-esteem is, how it develops (or fails to develop) and what influences it has kept psychologists busy for a long time, and there’s no sign that we’ll have it all figured out anytime soon!

While there is much we still have to learn about self-esteem, we have at least been able to narrow down what self-esteem is and how it differs from other, similar constructs. Read on to learn what sets self-esteem apart from other self-directed traits and states.

Self-Esteem vs. Self-Concept

Self-esteem is not self-concept, although self-esteem may be a part of self-concept. Self-concept is the perception that we have of ourselves, our answer when we ask ourselves the question “Who am I?” It is knowing about one’s own tendencies, thoughts, preferences and habits, hobbies, skills, and areas of weakness.

Put simply, the awareness of who we are is our concept of our self .

Purkey (1988) describes self-concept as:

“the totality of a complex, organized, and dynamic system of learned beliefs, attitudes and opinions that each person holds to be true about his or her personal existence”.

According to Carl Rogers, founder of client-centered therapy , self-concept is an overarching construct that self-esteem is one of the components of it (McLeod, 2008).

Self-Esteem vs. Self-Image

Another similar term with a different meaning is self-image; self-image is similar to self-concept in that it is all about how you see yourself (McLeod, 2008). Instead of being based on reality, however, it can be based on false and inaccurate thoughts about ourselves. Our self-image may be close to reality or far from it, but it is generally not completely in line with objective reality or with the way others perceive us.

Self-Esteem vs. Self-Worth

Self-esteem is a similar concept to self-worth but with a small (although important) difference: self-esteem is what we think, feel, and believe about ourselves, while self-worth is the more global recognition that we are valuable human beings worthy of love (Hibbert, 2013).

Self-Esteem vs. Self-Confidence

Self-esteem is not self-confidence ; self-confidence is about your trust in yourself and your ability to deal with challenges, solve problems, and engage successfully with the world (Burton, 2015). As you probably noted from this description, self-confidence is based more on external measures of success and value than the internal measures that contribute to self-esteem.

One can have high self-confidence, particularly in a certain area or field, but still lack a healthy sense of overall value or self-esteem.

Self-Esteem vs. Self-Efficacy

Similar to self-confidence, self-efficacy is also related to self-esteem but not a proxy for it. Self-efficacy refers to the belief in one’s ability to succeed at certain tasks (Neil, 2005). You could have high self-efficacy when it comes to playing basketball, but low self-efficacy when it comes to succeeding in math class.

Unlike self-esteem, self-efficacy is more specific rather than global, and it is based on external success rather than internal worth.

Self-Esteem vs. Self-Compassion

Finally, self-esteem is also not self-compassion. Self-compassion centers on how we relate to ourselves rather than how we judge or perceive ourselves (Neff, n.d.). Being self-compassionate means we are kind and forgiving to ourselves, and that we avoid being harsh or overly critical of ourselves. Self-compassion can lead us to a healthy sense of self-esteem, but it is not in and of itself self-esteem.

We explore this further in The Science of Self-Acceptance Masterclass© .

Esteem in Maslow’s Theory – The Hierarchy of Needs

The mention of esteem may bring to mind the fourth level of Maslow’s pyramid : esteem needs.

While these needs and the concept of self-esteem are certainly related, Maslow’s esteem needs are more focused on external measures of esteem, such as respect, status, recognition, accomplishment, and prestige (McLeod, 2017).

There is a component of self-esteem within this level of the hierarchy, but Maslow felt that the esteem of others was more important for development and need fulfillment than self-esteem.

Download 3 Free Self-Compassion Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you to help others create a kinder and more nurturing relationship with themselves.

Download 3 Free Self-Compassion Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Dr. Martin Seligman has some concerns about openly accepting self-esteem as part of positive psychology . He worries that people live in the world where self-esteem is injected into a person’s identity, not caring in how it is done, as long as the image of “confidence” is obtained. He expressed the following in 2006:

I am not against self-esteem, but I believe that self-esteem is just a meter that reads out the state of the system. It is not an end in itself. When you are doing well in school or work, when you are doing well with the people you love, when you are doing well in play, the meter will register high. When you are doing badly, it will register low. (p. v)

Seligman makes a great point, as it is important to take his words into consideration when looking at self-esteem. Self-esteem and positive psychology may not marry quite yet, so it is important to look at what research tells us about self-esteem before we construct a rationale for it as positive psychology researcher, coach, or practitioner.

Examples of these characteristics are being open to criticism, acknowledging mistakes, being comfortable with giving and receiving compliments, and displaying a harmony between what one says, does, looks, sounds, and moves.

People with high self-esteem are unafraid to show their curiosity, discuss their experiences, ideas, and opportunities. They can also enjoy the humorous aspects of their lives and are comfortable with social or personal assertiveness (Branden, 1992).

Although low self-esteem has received more attention than high self-esteem, the positive psychology movement has brought high self-esteem into the spotlight. We now know more about what high self-esteem looks like and how it can be cultivated.

We know that people with high self-esteem:

- Appreciate themselves and other people.

- Enjoy growing as a person and finding fulfillment and meaning in their lives.

- Are able to dig deep within themselves and be creative.

- Make their own decisions and conform to what others tell them to be and do only when they agree.

- See the word in realistic terms, accepting other people the way they are while pushing them toward greater confidence and a more positive direction.

- Can easily concentrate on solving problems in their lives.

- Have loving and respectful relationships.

- Know what their values are and live their lives accordingly.

- Speak up and tell others their opinions, calmly and kindly, and share their wants and needs with others.

- Endeavor to make a constructive difference in other people’s lives (Smith & Harte, n.d.).

We also know that there are some simple ways to tell if you have high self-esteem. For example, you likely have high self-esteem if you:

- Act assertively without experiencing any guilt, and feel at ease communicating with others.

- Avoid dwelling on the past and focus on the present moment.

- Believe you are equal to everyone else, no better and no worse.

- Reject the attempts of others to manipulate you.

- Recognize and accept a wide range of feelings, both positive and negative, and share them within your healthy relationships.

- Enjoy a healthy balance of work, play, and relaxation .

- Accept challenges and take risks in order to grow, and learn from your mistakes when you fail.

- Handle criticism without taking it personally, with the knowledge that you are learning and growing and that your worth is not dependent on the opinions of others.

- Value yourself and communicate well with others, without fear of expressing your likes, dislikes, and feelings.

- Value others and accept them as they are without trying to change them (Self Esteem Awareness, n.d.).

Based on these characteristics, we can come up with some good examples of what high self-esteem looks like.

Imagine a high-achieving student who takes a difficult exam and earns a failing grade. If she has high self-esteem, she will likely chalk up her failure to factors like not studying hard enough, a particularly difficult set of questions, or simply having an “off” day. What she doesn’t do is conclude that she must be stupid and that she will probably fail all future tests too.

Having a healthy sense of self-esteem guides her toward accepting reality, thinking critically about why she failed, and problem-solving instead of wallowing in self-pity or giving up.

For a second example, think about a young man out on a first date. He really likes the young woman he is going out with, so he is eager to make a good impression and connect with her. Over the course of their discussion on the date, he learns that she is motivated and driven by completely different values and has very different taste in almost everything.

Instead of going along with her expressed opinions on things, he offers up his own views and isn’t afraid to disagree with her. His high self-esteem makes him stay true to his values and allows him to easily communicate with others, even when they don’t agree. To him, it is more important to behave authentically than to focus on getting his date to like him.

23 Examples of Self-Esteem Issues

Here are 23 examples of issues that can manifest from low self-esteem:

- You people please

- You’re easily angered or irritated

- You feel your opinion isn’t important

- You hate you

- What you do is never good enough

- You’re highly sensitive to others opinions

- The world doesn’t feel safe

- You doubt every decision

- You regularly experience the emotions of sadness and worthlessness

- You find it hard keeping relationships

- You avoid taking risks or trying new things

- You engage in addictive avoidance behaviors

- You struggle with confidence

- You find it difficult creating boundaries

- You give more attention to your weaknesses

- You are often unsure of who you are

- You feel negative experiences are all consuming

- You struggle to say no

- You find it difficult asking for your needs to be met

- You hold a pessimistic or negative outlook on life

- You doubt your abilities or chances of success

- You frequently experience negative emotions, such as fear, anxiety or depression

- You compare yourself with others and often you come in second best

It can be hard to really wrap your mind around self-esteem and why it is so important. To help you out, we’ve gathered a list of some of the most significant and relevant findings about self-esteem and low self-esteem in particular.

Although some of these facts may make sense to you, you will likely find that at least one or two surprise you—specifically those pertaining to the depth and breadth of low self-esteem in people (and particularly young people and girls).

- Adolescent boys with high self-esteem are almost two and a half times more likely to initiate sex than boys with low self-esteem, while girls with high self-esteem are three times more likely to delay sex than girls with low self-esteem (Spencer, Zimet, Aalsma, & Orr, 2002).

- Low self-esteem is linked to violence, school dropout rates, teenage pregnancy, suicide, and low academic achievement (Misetich & Delis-Abrams, 2003).

- About 44% of girls and 15% of boys in high school are attempting to lose weight (Council on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse, n.d.).

- Seven in 10 girls believe that they are not good enough or don’t measure up in some way (Dove Self-Esteem Fund, 2008).

- A girl’s self-esteem is more strongly related to how she views her own body shape and body weight than how much she actually weighs (Dove Self-Esteem Fund, 2008).

- Nearly all women (90%) want to change at least one aspect of their physical appearance (Confidence Coalition, n.d.).

- The vast majority (81%) of 10-year old girls are afraid of being fat (Confidence Coalition, n.d.).

- About one in four college-age women have an eating disorder (Confidence Coalition, n.d.).

- Only 2% of women think they are beautiful (Confidence Coalition, n.d.).

- Absent fathers, poverty, and a low-quality home environment have a negative impact on self-esteem (Orth, 2018).

These facts on low self-esteem are alarming and disheartening, but thankfully they don’t represent the whole story. The whole story shows that there are many people with a healthy sense of self-esteem, and they enjoy some great benefits and advantages. For instance, people with healthy self-esteem:

- Are less critical of themselves and others.

- Are better able to handle stress and avoid the unhealthy side effects of stress.

- Are less likely to develop an eating disorder.

- Are less likely to feel worthless, guilty, and ashamed .

- Are more likely to be assertive about expressing and getting what they want.

- Are able to build strong, honest relationships and are more likely to leave unhealthy ones.

- Are more confident in their ability to make good decisions.

- Are more resilient and able to bounce back when faced with disappointment, failure, and obstacles (Allegiance Health, 2015).

Given the facts on the sad state of self-esteem in society and the positive outcomes associated with high self-esteem, it seems clear that looking into how self-esteem can be built is a worthwhile endeavor.

Luckily, there are many researchers who have tackled this topic. Numerous studies have shown us that it is possible to build self-esteem, especially in children and young people.

How? There are many ways!

Recent research found a correlation between self-esteem and optimism with university students from Brazil (Bastianello, Pacico & Hutz & 2014). One of the most interesting results came from a cross-cultural research on life satisfaction and self-esteem, which was conducted in 31 countries.

They found differences in self-esteem between collective and individualistic cultures with self-esteem being lower in collectivist cultures. Expressing personal emotions, attitudes, and cognitive thoughts are highly associated with self-esteem, collectivist cultures seem to have a drop in self-esteem because of a lack of those characteristics (Diener & Diener 1995).

China, a collectivist culture, found that self-esteem was a significant predictor of life satisfaction (Chen, Cheung, Bond & Leung, 2006). They found that similar to other collectivist cultures, self-esteem also had an effect on resilience with teenagers. Teenagers with low self-esteem had a higher sense of hopelessness and had low resilience (Karatas, 2011).

In more individualistic cultures, teenagers who were taught to depend on their beliefs, behaviors, and felt open to expressing their opinion had more resilience and higher self-esteem (Dumont & Provost, 1999).

School-based programs that pair students with mentors and focus on relationships, building, self-esteem enhancements, goal setting , and academic assistance have been proven to enhance students’ self-esteem, improve relationships with others, reduce depression and bullying behaviors (King, Vidourek, Davis, & McClellan, 2009).

Similarly, elementary school programs that focus on improving self-esteem through short, classroom-based sessions also have a positive impact on students’ self-esteem, as well as reducing problem behaviors and strengthening connections between peers (Park & Park, 2014).

However, the potential to boost your self-esteem and reap the benefits is not limited to students! Adults can get in on this endeavour as well, although the onus will be on them to make the changes necessary.

Self-esteem researcher and expert Dr. John M. Grohol outlined six practical tips on how to increase your sense of self-esteem, which include:

6 Practical Tips on How to Increase Self-Esteem

1. take a self-esteem inventory to give yourself a baseline..

It can be as simple as writing down 10 of your strengths and 10 of your weaknesses. This will help you to begin developing an honest and realistic conception of yourself.

2. Set realistic expectations.

It’s important to set small, reachable goals that are within your power. For example, setting an extremely high expectation or an expectation that someone else will change their behavior is virtually guaranteed to make you feel like a failure, through no fault of your own.

3. Stop being a perfectionist.

Acknowledge both your accomplishments and mistakes. Nobody is perfect, and trying to be will only lead to disappointment. Acknowledging your accomplishments and recognizing your mistakes is the way to keep a positive outlook while learning and growing from your mistakes.

4. Explore yourself.

The importance of knowing yourself and being at peace with who you are cannot be overstated. This can take some trial and error, and you will constantly learn new things about yourself, but it is a journey that should be undertaken with purpose and zeal.

5. Be willing to adjust your self-image.

We all change as we age and grow, and we must keep up with our ever-changing selves if we want to set and achieve meaningful goals.

6. Stop comparing yourself to others.

Comparing ourselves to others is a trap that is extremely easy to fall into, especially today with social media and the ability to project a polished, perfected appearance. The only person you should compare yourself to is you (Grohol, 2011).

The Positivity Blog also offers some helpful tips on enhancing your self-esteem, including:

- Say “stop” to your inner critic.

- Use healthier motivation habits.

- Take a 2-minute self-appreciation break.

- Write down 3 things in the evening that you can appreciate about yourself.

- Do the right thing.

- Replace the perfectionism.

- Handle mistakes and failures in a more positive way.

- Be kinder towards other people .

- Try something new.

- Stop falling into the comparison trap.

- Spend more time with supportive people (and less time with destructive people).

- Remember the “whys” of high self-esteem (Edberg, 2017).

Another list of specific, practical things you can do to develop and maintain a good sense of self-esteem comes from the Entrepreneur website:

- Use distancing pronouns. When you are experiencing stress or negative self-talk, try putting it in more distant terms (e.g., instead of saying “I am feeling ashamed,” try saying “Courtney is feeling ashamed.”). This can help you to see the situation as a challenge rather than a threat.

- Remind yourself of your achievements. The best way to overcome imposter syndrome—the belief that, despite all of your accomplishments, you are a failure and a fraud—is to list all of your personal successes. You might be able to explain a couple of them away as a chance, but they can’t all be due to luck!

- Move more! This can be as simple as a short walk or as intense as a several-mile run, as quick as striking a “power pose” or as long as a two-hour yoga session; it doesn’t matter exactly what you do, just that you get more in touch with your body and improve both your health and your confidence.

- Use the “five-second” rule. No, not the one about food that is dropped on the ground! This five-second rule is about following up good thoughts and inspiring ideas with action. Do something to make that great idea happen within five seconds.

- Practice visualizing your success. Close your eyes and take a few minutes to imagine the scenario in which you have reached your goals, using all five senses and paying attention to the details.

- Be prepared—for whatever situation you are about to encounter. If you are going into a job interview, make sure you have practiced, know about the company, and have some good questions ready to ask. If you are going on a date, take some time to boost your confidence, dress well, and have a plan A and a plan B (and maybe even a plan C!) to make sure it goes well.

- Limit your usage of social media. Spend less time looking at a screen and more time experiencing the world around you.

- Meditate. Establish a regular meditation practice to inspect your thoughts, observe them, and separate yourself from them. Cultivating a sense of inner peace will go a long way towards developing healthy self-esteem.

- Keep your goals a secret. You don’t need to keep all of your hopes and dreams to yourself, but make sure you save some of your goal striving and success for just you—it can make you more likely to meet them and also more satisfied when you do.

- Practice affirmations (like the ones listed later in this piece). Make time to regularly say positive things about yourself and situations in which you often feel uncertain.

- Build your confidence through failure. Use failure as an opportunity to learn and grow, and seek out failure by trying new things and taking calculated risks (Laurinavicius, 2017).

Now that we have a good idea of how to improve self-esteem , there is an important caveat to the topic: many of the characteristics and factors that we believe result from self-esteem may also influence one’s sense of self-esteem, and vice versa.

For example, although we recommend improving self-esteem to positively impact grades or work performance, success in these areas is at least somewhat dependent on self-esteem as well.

Similarly, those who have a healthy level of self-esteem are more likely to have positive relationships, but those with positive relationships are also more likely to have healthy self-esteem, likely because the relationship works in both directions.

While there is nothing wrong with boosting your self-esteem, keep in mind that in some cases you may be putting the cart before the horse, and commit to developing yourself in several areas rather than just working on enhancing your self-esteem.

Based on research like that described above, we have learned that there are many ways therapy and counseling can help clients to improve their self-esteem.

If done correctly, therapy can be an excellent method of enhancing self-esteem, especially if it’s low to begin with.

Here are some of the ways therapy and counseling can a client’s boost self-esteem:

- When a client shares their inner thoughts and feelings with the therapist, and the therapist responds with acceptance and compassion rather than judgment or correction, this can build the foundations of healthy self-esteem for the client.

- This continued acceptance and unconditional positive regard encourage the client to re-think some of their assumptions, and come to the conclusion that “Maybe there’s nothing wrong with me after all!”

- The therapist can explain that self-esteem is a belief rather than a fact and that beliefs are based on our experiences; this can help the client understand that he could be exactly the same person as he is right now and have high self-esteem instead of low, if he had different experiences that cultivated a sense of high self-esteem instead of low self-esteem.

- The therapist can offer the client new experiences upon which to base this new belief about herself, experiences in which the client is “basically acceptable” instead of “basically wrong.” The therapist’s acceptance of the client can act as a model for the client of how she can accept herself.

- Most importantly, the therapist can accept the client for who he is and affirm his thoughts and feelings as acceptable rather than criticizing him for them. The therapist does not need to approve of each and every action taken by the client, but showing acceptance and approval of who he is at the deepest level will have an extremely positive impact on his own belief in his worth and value as a person (Gilbertson, 2016).

Following these guidelines will encourage your client to develop a better sense of self-love , self-worth, self-acceptance , and self-esteem, as well as discouraging “needless shame” and learning how to separate herself from her behavior (Gilbertson, 2016).

One of these methods is meditation—yes, you can add yet another benefit of meditation to the list! However, not only can we develop self-esteem through meditation , we also gain some other important benefits.

When we meditate, we cultivate our ability to let go and to keep our thoughts and feelings in perspective. We learn to simply observe instead of actively participate in every little experience that pops into our head. In other words, we are “loosening the grip we have on our sense of self” (Puddicombe, 2015).

While this may sound counterintuitive to developing and maintaining a positive sense of self, it is actually a great way to approach it. Through meditation, we gain the ability to become aware of our inner experiences without over-identifying with them, letting our thoughts pass by without judgment or a strong emotional response.

As meditation expert Andy Puddicombe notes, low self-esteem can be understood as the result of over-identification with the self. When we get overly wrapped up in our sense of self, whether that occurs with a focus on the positive (I’m the BEST) or the negative (I’m the WORST), we place too much importance on it. We may even get obsessive about the self, going over every little word, thought, or feeling that enters our mind.

A regular meditation practice can boost your self-esteem by helping you to let go of your preoccupation with your self, freeing you from being controlled by the thoughts and feelings your self-experiences.

When you have the ability to step back and observe a disturbing or self-deprecating thought, it suddenly doesn’t have as much power over you as it used to; this deidentification with the negative thoughts you have about yourself results in less negative talk over time and freedom from your overly critical inner voice (Puddicombe, 2015).

Self-esteem is the topic of many a psychological scale and assessment, and many of them are valid, reliable, and very popular among researchers; however, these assessments are not perfect. There are a few problems and considerations you should take into account if you want to measure self-esteem, including:

- Lack of consensus on the definition (Demo, 1985).

- Overall gender differences in self-esteem (Bingham, 1983).

- Too many instruments for assessing self-esteem, and low correlations between them (Demo, 1985).

- The unexplained variance between self-reports and inferred measures such as ratings by others (Demo, 1985).

Although these issues are certainly not unique to the measurement of self-esteem, one should approach the assessment of self-esteem with multiple measurement methods in hand, with the appropriate level of caution, or both.

Still, even though there are various issues with the measurement of self-esteem, avoiding the measurement is not an option! If you are looking to measure self-esteem and worried about finding a validated scale, look no further than one of the foundations of self-esteem research: Rosenberg’s scale.

Measuring Self-Esteem with the Rosenberg Scale

The most common scale of self-esteem is Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (also called the RSE and sometimes the SES). This scale was developed by Rosenberg and presented in his 1965 book Society and the Adolescent Self-Image.

It contains 10 items rated on a scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). Some of the items are reverse-scored, and the total score can be calculated by summing up the total points for an overall measure of self-esteem (although it can also be scored in a different, more complex manner—see page 61 of this PDF for instructions).

The 10 items are:

1. On the whole, I am satisfied with myself. 2. At times I think I am no good at all. 3. I feel that I have a number of good qualities. 4. I am able to do things as well as most other people. 5. I feel I do not have much to be proud of. 6. I certainly feel useless at times. 7. I feel that I’m a person of worth. 8. I wish I could have more respect for myself. 9. All in all, I am inclined to think that I am a failure. 10. I take a positive attitude toward myself.

As you likely figured out already, items 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9 are reverse-scored, while the other items are scored normally. This creates a single score of between 10 and 40 points, with lower scores indicating higher self-esteem. Put another way, higher scores indicate a strong sense of low self-esteem.

The scale is considered highly consistent and reliable, and scores correlate highly with other measures of self-esteem and negatively with measures of depression and anxiety. It has been used by thousands of researchers throughout the years and is still in use today, making it one of the most-cited scales ever developed.

The Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory (1967/1981)

The second most commonly used reliable and valid measure for self-esteem is The Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory. Within this test, 50 items are included to measure the test-takes attitudes towards themselves, by responding to statements with the selection of “like me” or “not like me” (Robinson, Shaver & Wrightsman, 2010).

Initially created to test the self-esteem of children, it was later altered by Ryden (1978) and now two separate versions exist; one for children and one for adults.

Find out more about taking this test here .

It might be quicker to list what factors don’t influence self-esteem than to identify which factors do influence it! As you might expect, self-esteem is a complex construct and there are many factors that contribute to it, whether positively or negatively.

For a quick sample of some of the many factors that are known to influence self-esteem, check out this list:

- Commitment to the worker, spouse, and parental role are positively linked to self-esteem (Reitzes & Mutran, 1994).

- Worker identity meaning is positively related to self-esteem (Reitzes & Mutran, 2006).

- Being married and older is linked to lower self-esteem (Reitzes & Mutran, 2006).

- Higher education and higher income are related to higher self-esteem (Reitzes & Mutran, 2006).

- Low socioeconomic status and low self-esteem are related (von Soest, Wagner, Hansen, & Gerstorf, 2018).

- Living alone (without a significant other) is linked to low self-esteem (van Soest et al., 2018).

- Unemployment and disability contribute to lower self-esteem (van Soest et al., 2018).

- A more mature personality and emotional stability are linked to higher self-esteem (van Soest et al., 2018).

- Social norms (the importance of friends’ and family members’ opinions) about one’s body and exercise habits are negatively linked to self-esteem, while exercise self-efficacy and self-fulfillment are positively linked to self-esteem (Chang & Suttikun, 2017).

If you’re thinking that an important technological factor is missing, go on to the next section and see if you’re right!

Although you may have found some of the findings on self-esteem covered earlier surprising, you will most likely expect this one: studies suggest that social media usage negatively impacts self-esteem (Friedlander, 2016).

This effect is easy to understand. Humans are social creatures and need interaction with others to stay healthy and happy; however, we also use those around us as comparisons to measure and track our own progress in work, relationships, and life in general. Social media makes these comparisons easier than ever, but they give this tendency to compare a dark twist.

What we see on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter is not representative of real life. It is often carefully curated and painstakingly presented to give the best possible impression.

We rarely see the sadness, the failure, and the disappointment that accompanies everyday human life; instead, we see a perfect picture, a timeline full of only good news, and short blurbs about achievements, accomplishments, and happiness .

Although this social comparison with unattainable standards is clearly a bad habit to get into, social media is not necessarily a death knell for your self-esteem. Moderate social media usage complemented by frequent self-reminders that we are often only seeing the very best in others can allow us to use social media posts as inspiration and motivation rather than unhealthy comparison.

You don’t need to give up social media for good in order to maintain a healthy sense of self-esteem—just use it mindfully and keep it in the right perspective!

By viewing self-esteem as a muscle to grow we establish a world of new opportunities. No longer do we have to view ourselves in the same light.

Use these 10 tips to strengthen the attitudes towards yourself:

1. Spend time with people who lift you up 2. Giveback by helping others 3. Celebrate your achievements, no matter the size 4. Do what makes you happy 5. Change what you can – and let go of what you can’t 6. Let go of perfectionism ideals 7. Speak to yourself like a friend 8. Get involved in extra-curricula’s 9. Own your uniqueness 10. Create a positive self-dialogue.

Influential American author, Jack Canfield explains “Daily affirmations are to the mind what exercise is to the body.” (watch this YouTube clip).

Affirmations are a great way to boost your self-esteem and, in turn, your overall wellbeing. There are tons of examples of affirmations you can use for this purpose, including these 17 from Develop Good Habits :

- Mistakes are a stepping stone to success. They are the path I must tread to achieve my dreams.

- I will continue to learn and grow.

- Mistakes are just an apprenticeship to achievement.

- I deserve to be happy and successful.

- I deserve a good life. I deny any need for suffering and misery.

- I am competent, smart, and able.

- I am growing and changing for the better.

- I love the person I am becoming.

- I believe in my skills and abilities.

- I have great ideas. I make useful contributions.

- I acknowledge my own self-worth; my self-confidence is rising.

- I am worthy of all the good things that happen in my life.

- I am confident with my life plan and the way things are going.

- I deserve the love I am given.

- I let go of the negative feelings about myself and accept all that is good.

- I will stand by my decisions. They are sound and reasoned.

- I have, or can quickly get, all the knowledge I need to succeed.

If none of these leap out and inspire you, you can always create your own! Just keep in mind these three simple rules for creating effective affirmations:

- The affirmations should be in the present tense. They must affirm your value and worth right here, right now (e.g., not “I will do better tomorrow” but “I am doing great today.”).

- The affirmations should be positively worded. They should not deny or reject anything (i.e., “I am not a loser.”), but make a firm statement (e.g., “I am a worthy person.”).

- The affirmations should make you feel good and put you in a positive light. They should not be empty words and they should be relevant to your life (e.g., “I am a world-class skier” is relevant if you ski, but is not a good affirmation if you don’t ski.).

Use these three rules to put together some positive, uplifting, and encouraging affirmations that you can repeat as often as needed—but aim for at least once a day.

There are many, many books available on self-esteem: what it is, what influences it, how it can be developed, and how it can be encouraged in others (particularly children). Here is just a sample of some of the most popular and well-received books on self-esteem :

- Self-Esteem: A Proven Program of Cognitive Techniques for Assessing, Improving, and Maintaining Your Self-Esteem by Matthew McKay, PhD ( Amazon )

- The Self-Esteem Guided Journal by Matthew McKay & C. Sutker ( Amazon )

- Ten Days to Self-Esteem by David D. Burns, MD ( Amazon )

- The Six Pillars of Self-Esteem: The Definitive Work on Self-Esteem by the Leading Pioneer in the Field by Nathanial Branden (if you’re not a big reader, check out the animated book review video below) ( Amazon )

- The Self-Esteem Workbook by Glenn R. Schiraldi, PhD ( Amazon )

- The Self-Esteem Workbook for Teens: Activities to Help You Build Confidence and Achieve Your Goals by Lisa M. Schab, LCSW ( Amazon )

- Believing in Myself by E Larsen & C Hegarty. ( Amazon )

- Being Me: A Kid’s Guide to Boosting Confidence and Self-Esteem by Wendy L. Moss, PhD ( Amazon )

- Healing Your Emotional Self: A Powerful Program to Help You Raise Your Self-Esteem, Quiet Your Inner Critic, and Overcome Your Shame by Beverly Engel ( Amazon )

Plus, here’s a bonus—a free PDF version of Nathaniel Branden’s The Psychology of Self-Esteem: A Revolutionary Approach to Self-Understanding That Launched a New Era in Modern Psychology .

If reading is not a preferred method of learning more, fear not! There are some great YouTube videos and TED Talks on self-esteem. A few of the most popular and most impactful are included here.

Why Thinking You’re Ugly is Bad for You by Meaghan Ramsey

This TED talk is all about the importance of self-esteem and the impact of negative self-esteem, especially on young people and girls. Ramsey notes that low self-esteem impacts physical as well as mental health, the work we do, and our overall finances as we chase the perfect body, the perfect face, or the perfect hair. She ends by outlining the six areas addressed by effective self-esteem programs:

- The influence of family, friends, and relationships

- The media and celebrity culture

- How to handle teasing and bullying

- The way we compete and compare ourselves with others

- The way we talk about appearance

- The foundations of respecting and caring for yourself

Meet Yourself: A User’s Guide to Building Self-Esteem by Niko Everett

Another great TEDx Talk comes from the founder of the Girls for Change organization, Niko Everett. In this talk, she goes over the power of self-knowledge, self-acceptance, and self-love. She highlights the importance of the thoughts we have about ourselves and the impact they have on our self-esteem and shares some techniques to help both children and adults enhance their self-esteem.

Self-Esteem – Understanding & Fixing Low Self-Esteem by Actualized.org

This video from Leo Gura at Actualized.org defines self-esteem, describes the elements of self-esteem, and the factors that influence self-esteem. He shares why self-esteem is important and how it can be developed and enhanced.

How to Build Self Esteem – The Six Pillars of Self-Esteem by Nathaniel Branden Animated Book Review by FightMediocrity

This quick, 6-minute video on self-esteem outlines what author Nathaniel Branden sees as the “Six Pillars” of self-esteem:

- The practice of living consciously Be aware of your daily activities and relationship with others, insecure reflections, and also personal priorities.

- The practice of self-acceptance This includes becoming aware and accepting the best and the worst parts of you and also the disowned parts of ourselves.

- The practice of self-responsibility This implies realizing that you are responsible for your choices and actions.

- The practice of self-assertiveness Act through your real convictions and feelings as much as possible.

- The practice of living purposefully Achieve personal goals that energize your existence.

- The practice of personal integrity Don’t compensate your ideals, beliefs, and behaviors for a result that leads to incongruence. When your behaviors are congruent with your ideals, integrity will appear.

The speaker provides a definition and example of each of the six pillars and finishes the video by emphasizing the first two words of each pillar: “The Practice.” These words highlight that the effort applied to building self-esteem is, in fact, the most important factor in developing self-esteem.

Sometimes all you need to get to work on bettering yourself is an inspirational quote. The value of quotes is subjective, so these may not all resonate with you, but hopefully, you will find that at least one or two lights that spark within you!

“You yourself, as much as anybody in the entire universe, deserve your love and affection.”

Sharon Salzberg

“The greatest thing in the world is to know how to belong to oneself.”

Michel de Montaigne

“The man who does not value himself, cannot value anything or anyone.”

“Dare to love yourself as if you were a rainbow with gold at both ends.”

“As long as you look for someone else to validate who you are by seeking their approval, you are setting yourself up for disaster. You have to be whole and complete in yourself. No one can give you that. You have to know who you are—what others say is irrelevant.”

“I don’t want everyone to like me; I should think less of myself if some people did.”

Henry James

“Remember, you have been criticizing yourself for years and it hasn’t worked. Try approving of yourself and see what happens.”

Louise L. Hay

“Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness that most frightens us. We ask ourselves, Who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous, talented, fabulous? Actually, who are you not to be?”

Marianne Williamson

“I don’t entirely approve of some of the things I have done, or am, or have been. But I’m me. God knows, I’m me.”

“To me, self-esteem is not self-love. It is self-acknowledgement, as in recognizing and accepting who you are.”

Amity Gaige

“Self-esteem is as important to our well-being as legs are to a table. It is essential for physical and mental health and for happiness.”

Louise Hart

“Self-esteem is made up primarily of two things: feeling lovable and feeling capable. Lovable means I feel people want to be with me. They invite me to parties; they affirm I have the qualities necessary to be included. Feeling capable is knowing that I can produce a result. It’s knowing I can handle anything that life hands me.”

Jack Canfield

“You can’t let someone else lower your self-esteem, because that’s what it is—self-esteem. You need to first love yourself before you have anybody else love you.”

Winnie Harlow

“A man cannot be comfortable without his own approval.”

“Our self-respect tracks our choices. Every time we act in harmony with our authentic self and our heart, we earn our respect. It is that simple. Every choice matters.” Dan Coppersmith

17 Exercises To Foster Self-Acceptance and Compassion

Help your clients develop a kinder, more accepting relationship with themselves using these 17 Self-Compassion Exercises [PDF] that promote self-care and self-compassion.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

We hope you enjoyed this opportunity to learn about self-esteem! If you take only one important lesson away from this piece, make sure it’s this one: you absolutely can build your own self-esteem, and you can have a big impact on the self-esteem of those you love.

Self-esteem is not a panacea—it will not fix all of your problems or help you sail smoothly through a life free of struggle and suffering—but it will help you find the courage to try new things, build the resilience to bounce back from failure, and make you more susceptible to success.

It is something we have to continually work towards, but it’s absolutely achievable.

Stay committed.

Keep aware of your internal thoughts and external surroundings. Keep focused on your personal goals and all that is possible when self-doubt isn’t holding you back.

What are your thoughts on self-esteem in psychology? Should we be encouraging it more? Less? Is there an “ideal amount” of self-esteem? We’d love to hear from you! Leave your thoughts in the comments below.

You can read more about self-esteem worksheets and exercises for adults and teens here .

Thanks for reading!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Self Compassion Exercises for free .

- Adler, N., & Stewart, J. (2004). Self-esteem. Psychosocial Working Group. Retrieved from http://www.macses.ucsf.edu/research/psychosocial/selfesteem.php

- Allegiance Health. (2015). 8 Health benefits of a healthy self-esteem. Health & Wellness Blog. Retrieved from https://www.allegiancehealth.org/blog/women/8-health-benefits-healthy-self-esteem

- Bastianello, M., Pacico, J., & Hutz, C. (2014). Optimism, self-esteem and personality: Adaptation and validation of the Brazilian Version Of The Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R). Psico-USF, Bragança Paulista . Retrieved from http://www.scielo.br/pdf/pusf/v19n3/15.pdf

- Branden, N. (1992). The power of self-esteem. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications.

- Branden, N. (2013). What self-esteem is and is not. Retrieved from http://www.nathanielbranden.com/what-self-esteem-is-and-is-not.

- Bingham, W. C. (1983). Problems in the assessment of self-esteem. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 6, 17-22.

- Brockner, J. 1984. Low self-esteem and behavioral plasticity: Some implications for personality and social psychology. In L. Wheeler (Ed.), Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 37 : 1732–1741.

- Burton, N. (2015). Self-confidence versus self-esteem. Psychology Today . Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/hide-and-seek/201510/self-confidence-versus-self-esteem

- Chang, H. J., & Suttikun, C. (2017). The examination of psychological factors and social norms affecting body satisfaction and self-esteem for college students. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 45 (4) , 422-437 .

- Chen, S. X., Cheung, F. M., Bond, M. H., & Leung, J. (2006). Going beyond self-esteem to predict life satisfaction: The Chinese case. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 9, 24-35.

- Confidence Coalition. (n.d.). Join KD in the movement to build confidence in girls and women. Kappa Delta Sorority. Retrieved from https://kappadelta.org/initiatives/confidence-coalition/

- Council on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse. (n.d.). Image and self-esteem. Mentor Resource Center. Retrieved from http://mentor-center.org/image-and-self-esteem/.

- Crocker, J., & Park, L. E. (2003). Seeking self-esteem: Construction, maintenance, and protection of self-worth .

- Davis, W., Gfeller, K., & Thaut, M. (2008). An introduction to music therapy. Silver Spring, MD: American Music Therapy Association.

- Demo, D. H. (1985). The measurement of self-esteem: Refining our methods. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 1490-1502.

- Diener, E. & Diener, M. (1995). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68 , 653–663.

- Dumont, M. & Provost, M. A,. (1999). Resilience in adolescents: Protective role of social support, coping strategies, self-esteem, and social activities on experience of stress and depression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28, 343-363.

- Dove Self-Esteem Fund. (2008). Real girls, real pressure: A national report on the state of self-esteem. Dove. Retrieved from http://www.isacs.org/misc_files/SelfEsteem_Report%20-%20Dove%20Campaign%20for%20Real%20Beauty.pdf

- Edberg, H. (2013). How to improve your self-esteem: 12 Powerful tips. The Positivity Blog. Retrieved from https://www.positivityblog.com/improve-self-esteem/

- Ellis, A. (1994). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy . Birch Lane Press.

- Ellis, A. (1976). RET abolishes most of the human ego. Psychotherapy: Theory, research & practice, 13(4) , 343.

- Friedlander, J. (2016). Why social media is ruining your self-esteem—and how to stop it. Success. Retrieved from https://www.success.com/article/why-social-media-is-ruining-your-self-esteem-and-how-to-stop-it

- Gilbertson, T. (2016). Does therapy for low self-esteem really work? Good Therapy. Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/does-therapy-for-low-self-esteem-really-work-0520164

- Grogan, S. (1999). Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children . London, UK: Routledge.

- Grohol, J. M. (2011). 6 Tips to improve your self-esteem. Psych Central. Retrieved from https://psychcentral.com/blog/6-tips-to-improve-your-self-esteem/

- Hibbert, C. (2013). Self-esteem vs. self-worth: Q & A with Dr. Christina Hibbert. Retrieved from http://www.drchristinahibbert.com/self-esteem-vs-self-worth/

- Karatas, Z., & Cakar, F. S. (2011). Self-esteem and hopelessness, and resiliency: An exploratory study of adolescents in Turkey. International Education Studies , 4 (4), 84-91.

- Kernis, M. H., & Lakey, C. E. (2010). Fragile versus secure high self-esteem: Implications for defensiveness and insecurity . Psychology Press.

- King, K. A., Vidourek, R. A., Davis, B., & McClellan, W. (2009). Increasing self-esteem and school connectedness through a multidimensional mentoring program. Journal of School Health, 72 , 294-299.

- Laurinavicius, T. (2017). 11 Research-backed hacks to improve self-confidence. Entrepreneur. Retrieved from https://www.entrepreneur.com/slideshow/302265.

- MacInnes, D. L. (2006). Self‐esteem and self‐acceptance: an examination into their relationship and their effect on psychological health. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 13(5) , 483-489.

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4) , 370-396.

- McLeod, S. (2008). Self concept. Simply Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/self-concept.html.

- McLeod, S. (2017). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Simply Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html.

- Myers, D. G., & Diener, E. (1995). Who is happy?. Psychological science, 6(1) , 10-19.

- Misetich, M., & Delis-Abrams, A. (2003). Your self esteem is up to YOU. Self-Growth. Retrieved from http://www.selfgrowth.com/articles/Abrams1.html.

- Neff, K. (n.d.). Why self-compassion is healthier than self-esteem. Self-Compassion.org. Retrieved from http://self-compassion.org/why-self-compassion-is-healthier-than-self-esteem/

- Neill, J. (2005). Definitions of various self constructs. Wilderdom. Retrieved from http://www.wilderdom.com/self/.

- Orth, U. (2018). The family environment in early childhood has a long-term effect on self-esteem: A longitudinal study from birth to age 27 years. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114, 637-655.

- Park, K. M., & Park, H. (2014). Effects of self-esteem improvement program on self-esteem and peer attachment in elementary school children with observed problematic behaviors. Asian Nursing Research, 9, 53-59.

- Purkey, W. (1988). An overview of self-concept theory for counselors. ERIC Clearinghouse on Counseling and Personnel Services. Ann Arbor: MI (An ERIC/CAPS Digest: ED304630).

- Reitzes, D. C., & Mutran, E. J. (1994). Multiple roles and identities: Factors influencing self-esteem among middle-aged working men and women. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57, 313-325.

- Reitzes, D. C., & Mutran, E. J. (2006). Self and health: Factors that encourage self-esteem and functional health. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 61 (1), S44-S51.

- Robinson, J., Shaver, P., & Wrightsman, L. (2010). Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Self Esteem Awareness. (n.d.). 1 0 Positive self esteem examples. Retrieved from https://www.selfesteemawareness.com/10-positive-self-esteem-examples/

- Seligman, M. (2006). Learned optimism: How to change your mind and your life. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Smith, S. R., & Harte, V. (n.d.). 10 Characteristics of people with high self-esteem. Dummies. Retrieved from http://www.dummies.com/health/mental-health/self-esteem/10-characteristics-of-people-with-high-self-esteem/

- Spencer, J., Zimet, G., Aalsma, M., & Orr, D. (2002). Self-esteem as a predictor of initiation of coitus in early adolescents. Pediatrics, 109, 581-584.

- Von Soest, T., Wagner, J., Hansen, T., & Gerstorf, D. (2018). Self-esteem across the second half of life: The role of socioeconomic status, physical health, social relationships, and personality factors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114, 945-958.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Interesting, and clear and quite precise in this definitions…..definitions are the most important.

Extremely good article addressing the prevalence of low self-esteem in Western society and how to overcome it. But did it consider the possibility self-esteem could ever be too high? I am still influenced by my old-school upbringing, where being labeled as “conceited” was a a thing. I was told that’s only an attempt to compensate for low self esteem, along with “egomania” and other disorders, but perhaps related to the driven personalities that have influenced much of history.

Excellent, Elaborative, Enduring and Eloquent ESSAY 🙂 Loved this article, very clear, very informative, very useful and practically implementable if determined to improve the quality of one’s life. THANK YOU is a small word for the author of this article.

thak you for this good article

Very helpful. Thank you very much

Thanks for sharing it. I’m happy after reading it , please keep continue to enlighten people

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Social Identity Theory: I, You, Us & We. Why Groups Matter

As humans, we spend most of our life working to understand our personal identities. The question of “who am I?” is an age-old philosophical thought [...]

Discovering Self-Empowerment: 13 Methods to Foster It

In a world where external circumstances often dictate our sense of control and agency, the concept of self-empowerment emerges as a beacon of hope and [...]

How to Improve Your Client’s Self-Esteem in Therapy: 7 Tips

When children first master the expectations set by their parents, the experience provides them with a source of pride and self-esteem. As children get older, [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Self-Compassion Tools (PDF)

- Introduction To Self-Esteem

Introduction to Self-Esteem

Ad Disclosure: Some of our MentalHelp.net recommendations, including BetterHelp, are also affiliates, and as such we may receive compensation from them if you choose to purchase products or services through the links provided

Self-esteem refers to the overall sense of self-worth or personal value we attribute to ourselves. It's an internal assessment of how much we value and appreciate ourselves, regardless of external circumstances or others' opinions. Self-esteem encompasses beliefs about yourself (for example, "I am competent," "I am worthy") as well as emotional states such as triumph, despair, pride, and shame. A healthy level of self-esteem is crucial for overall well-being, influencing decision-making processes, relationships, and the ability to face life's challenges. It forms the foundation of mental and emotional health, enabling us to navigate life with confidence and resilience. Understanding and nurturing our self-esteem can lead to a more fulfilling and balanced life.

The Relationship Between Self-Esteem and Well-being

Self-esteem plays a pivotal role in our overall well-being and mental health, acting as both a protective factor against life's stressors and a facilitator of psychological resilience. Healthy self-esteem contributes to a robust mental state, empowering individuals to approach life with optimism and courage. It is intricately linked to how we manage stress, how we relate to others, and our capacity for happiness and contentment.

Here are some ways self-esteem affects different aspects of life:

- Mental Health : A healthy level of self-esteem is associated with lower rates of mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and stress. When we value ourselves and have confidence in our abilities, we are less likely to succumb to the cognitive distortions that fuel these conditions. Conversely, low self-esteem can be both a cause and a consequence of mental health challenges. However, professional intervention can assist in addressing these.

- Resilience to Stress : Individuals with high self-esteem often exhibit greater resilience in the face of adversity. Individuals with healthy self-esteem possess a sturdy foundation of self-worth. This resilience enables them to recover more quickly from setbacks and maintain a positive outlook on life.

- Relationships : Self-esteem affects the quality of our relationships. When we feel good about ourselves, we are more likely to engage in positive interactions and establish healthy boundaries. High self-esteem allows us to feel secure in our relationships, reducing the likelihood of developing dependency or tolerating mistreatment.

- Decision-Making and Achievement : Self-belief is crucial for setting and achieving goals. High self-esteem fosters a mindset of growth and possibility, encouraging individuals to pursue ambitions with determination. It enhances our ability to make decisions, face challenges head-on, and seize opportunities for personal and professional growth.

- Happiness and Contentment : At its core, self-esteem influences our capacity for happiness. A positive self-image enhances life satisfaction and joy. People with high self-esteem are more likely to engage in activities that bring them happiness and to forge meaningful connections with others.

Therapists are Standing By to Treat Your Depression, Anxiety or Other Mental Health Needs

Explore Your Options Today

In summary, self-esteem is not just about feeling good about yourself; it's a fundamental aspect of mental and emotional health that influences your interaction with the world. Nurturing self-esteem is essential for a balanced, happy life and forms the basis for strong mental health and enduring well-being.

Negative Self-Concept

Conversely, a negative self-concept is deeply ingrained in the way individuals perceive themselves, marked by a persistent feeling of inadequacy and a lack of self-worth. This perception is more than just occasional self-doubt; it is an enduring view of oneself as unworthy, incompetent, and undeserving. Such a self-concept shapes every aspect of life, from how individuals interact with others to how they face challenges and perceive their place in the world.

Characterized by self-criticism and a focus on perceived faults, a negative self-concept influences emotions, behaviors, and decision-making processes. Individuals may find themselves trapped in a cycle of self-sabotage, avoiding opportunities for fear of failure or withdrawing from social situations due to a fear of judgment or rejection. This constant self-scrutiny not only diminishes a person's capacity to enjoy life but also erects barriers to personal growth and fulfillment.

The ripple effects of a negative self-concept extend into mental health, contributing to conditions such as depression and anxiety. The relentless inner critic amplifies feelings of isolation and despair, making it challenging to seek help or engage in positive self-reflection. What's more, this skewed self-perception can strain relationships, as insecurities may manifest in defensive or withdrawn behaviors, further isolating the individual.

Overcoming a negative self-concept requires a conscious effort to acknowledge and challenge these harmful thought patterns. It involves cultivating self-compassion, seeking supportive relationships, and engaging in activities that reinforce a sense of competence and achievement. Transforming self-esteem is a gradual process, but with patience and persistence, it is possible to develop a healthier, more positive self-concept that enhances well-being and fosters a fulfilling life.