- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Health Education Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction.

- < Previous

Young people and healthy eating: a systematic review of research on barriers and facilitators

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

J Shepherd, A Harden, R Rees, G Brunton, J Garcia, S Oliver, A Oakley, Young people and healthy eating: a systematic review of research on barriers and facilitators, Health Education Research , Volume 21, Issue 2, 2006, Pages 239–257, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyh060

- Permissions Icon Permissions

A systematic review was conducted to examine the barriers to, and facilitators of, healthy eating among young people (11–16 years). The review focused on the wider determinants of health, examining community- and society-level interventions. Seven outcome evaluations and eight studies of young people's views were included. The effectiveness of the interventions was mixed, with improvements in knowledge and increases in healthy eating but differences according to gender. Barriers to healthy eating included poor school meal provision and ease of access to, relative cheapness of and personal taste preferences for fast food. Facilitators included support from family, wider availability of healthy foods, desire to look after one's appearance and will-power. Friends and teachers were generally not a common source of information. Some of the barriers and facilitators identified by young people had been addressed by soundly evaluated effective interventions, but significant gaps were identified where no evaluated interventions appear to have been published (e.g. better labelling of food products), or where there were no methodologically sound evaluations. Rigorous evaluation is required particularly to assess the effectiveness of increasing the availability of affordable healthy food in the public and private spaces occupied by young people.

Healthy eating contributes to an overall sense of well-being, and is a cornerstone in the prevention of a number of conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, stroke, cancer, dental caries and asthma. For children and young people, healthy eating is particularly important for healthy growth and cognitive development. Eating behaviours adopted during this period are likely to be maintained into adulthood, underscoring the importance of encouraging healthy eating as early as possible [ 1 ]. Guidelines recommend consumption of at least five portions of fruit and vegetables a day, reduced intakes of saturated fat and salt and increased consumption of complex carbohydrates [ 2, 3 ]. Yet average consumption of fruit and vegetables in the UK is only about three portions a day [ 4 ]. A survey of young people aged 11–16 years found that nearly one in five did not eat breakfast before going to school [ 5 ]. Recent figures also show alarming numbers of obese and overweight children and young people [ 6 ]. Discussion about how to tackle the ‘epidemic’ of obesity is currently high on the health policy agenda [ 7 ], and effective health promotion remains a key strategy [ 8–10 ].

Evidence for the effectiveness of interventions is therefore needed to support policy and practice. The aim of this paper is to report a systematic review of the literature on young people and healthy eating. The objectives were

(i) to undertake a ‘systematic mapping’ of research on the barriers to, and facilitators of, healthy eating among young people, especially those from socially excluded groups (e.g. low-income, ethnic minority—in accordance with government health policy);

(ii) to prioritize a subset of studies to systematically review ‘in-depth’;

(iii) to ‘synthesize’ what is known from these studies about the barriers to, and facilitators of, healthy eating with young people, and how these can be addressed and

(iv) to identify gaps in existing research evidence.

General approach

This study followed standard procedures for a systematic review [ 11, 12 ]. It also sought to develop a novel approach in three key areas.

First, it adopted a conceptual framework of ‘barriers’ to and ‘facilitators’ of health. Research findings about the barriers to, and facilitators of, healthy eating among young people can help in the development of potentially effective intervention strategies. Interventions can aim to modify or remove barriers and use or build upon existing facilitators. This framework has been successfully applied in other related systematic reviews in the area of healthy eating in children [ 13 ], physical activity with children [ 14 ] and young people [ 15 ] and mental health with young people [16; S. Oliver, A. Harden, R. Rees, J. Shepherd, G. Brunton and A. Oakley, manuscript in preparation].

Second, the review was carried out in two stages: a systematic search for, and mapping of, literature on healthy eating with young people, followed by an in-depth systematic review of the quality and findings of a subset of these studies. The rationale for a two-stage review to ensure the review was as relevant as possible to users. By mapping a broad area of evidence, the key characteristics of the extant literature can be identified and discussed with review users, with the aim of prioritizing the most relevant research areas for systematic in-depth analysis [ 17, 18 ].

Third, the review utilized a ‘mixed methods’ triangulatory approach. Data from effectiveness studies (‘outcome evaluations’, primarily quantitative data) were combined with data from studies which described young people's views of factors influencing their healthy eating in negative or positive ways (‘views’ studies, primarily qualitative). We also sought data on young people's perceptions of interventions when these had been collected alongside outcomes data in outcome evaluations. However, the main source of young people's views was surveys or interview-based studies that were conducted independently of intervention evaluation (‘non-intervention’ research). The purpose was to enable us to ascertain not just whether interventions are effective, but whether they address issues important to young people, using their views as a marker of appropriateness. Few systematic reviews have attempted to synthesize evidence from both intervention and non-intervention research: most have been restricted to outcome evaluations. This study therefore represents one of the few attempts that have been made to date to integrate different study designs into systematic reviews of effectiveness [ 19–22 ].

Literature searching

A highly sensitive search strategy was developed to locate potentially relevant studies. A wide range of terms for healthy eating (e.g. nutrition, food preferences, feeding behaviour, diets and health food) were combined with health promotion terms or general or specific terms for determinants of health or ill-health (e.g. health promotion, behaviour modification, at-risk-populations, sociocultural factors and poverty) and with terms for young people (e.g. adolescent, teenager, young adult and youth). A number of electronic bibliographic databases were searched, including Medline, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, ERIC, Social Science Citation Index, CINAHL, BiblioMap and HealthPromis. The searches covered the full range of publication years available in each database up to 2001 (when the review was completed).

Full reports of potentially relevant studies identified from the literature search were obtained and classified (e.g. in terms of specific topic area, context, characteristics of young people, research design and methodological attributes).

Inclusion screening

Inclusion criteria were developed and applied to each study. The first round of screening was to identify studies to populate the map. To be included, a study had to (i) focus on healthy eating; (ii) include young people aged 11–16 years; (iii) be about the promotion of healthy eating, and/or the barriers to, or facilitators of, healthy eating; (iv) be a relevant study type: (a) an outcome evaluation or (b) a non-intervention study (e.g. cohort or case control studies, or interview studies) conducted in the UK only (to maximize relevance to UK policy and practice) and (v) be published in the English language.

The results of the map, which are reported in greater detail elsewhere [ 23 ], were used to prioritize a subset of policy relevant studies for the in-depth systematic review.

A second round of inclusion screening was performed. As before, all studies had to have healthy eating as their main focus and include young people aged 11–16 years. In addition, outcome evaluations had toFor a non-intervention study to be included it had to

(i) use a comparison or control group; report pre- and post-intervention data and, if a non-randomized trial, equivalent on sociodemographic characteristics and pre-intervention outcome variables (demonstrating their ‘potential soundness’ in advance of further quality assessment);

(ii) report an intervention that aims to make a change at the community or society level and

(iii) measure behavioural and/or physical health status outcomes.

(i) examine young people's attitudes, opinions, beliefs, feelings, understanding or experiences about healthy eating (rather than solely examine health status, behaviour or factual knowledge);

(ii) access views about one or more of the following: young people's definitions of and/or ideas about healthy eating, factors influencing their own or other young people's healthy eating and whether and how young people think healthy eating can be promoted and

(iii) privilege young people's views—presenting views directly as data that are valuable and interesting in themselves, rather than only as a route to generating variables to be tested in a predictive or causal model.

Non-intervention studies published before 1990 were excluded in order to maximize the relevance of the review findings to current policy issues.

Data extraction and quality assessment

All studies meeting inclusion criteria underwent data extraction and quality assessment, using a standardized framework [ 24 ]. Data for each study were entered independently by two researchers into a specialized computer database [ 25 ] (the full and final data extraction and quality assessment judgement for each study in the in-depth systematic review can be viewed on the Internet by visiting http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk ).

Outcome evaluations were considered methodologically ‘sound’ if they reported:Only studies meeting these criteria were used to draw conclusions about effectiveness. The results of the studies which did not meet these quality criteria were judged unclear.

(i) a control or comparison group equivalent to the intervention group on sociodemographic characteristics and pre-intervention outcome variables.

(ii) pre-intervention data for all individuals or groups recruited into the evaluation;

(iii) post-intervention data for all individuals or groups recruited into the evaluation and

(iv) on all outcomes, as described in the aims of the intervention.

Non-intervention studies were assessed according to a total of seven criteria (common to sets of criteria proposed by four research groups for qualitative research [ 26–29 ]):

(i) an explicit account of theoretical framework and/or the inclusion of a literature review which outlined a rationale for the intervention;

(ii) clearly stated aims and objectives;

(iii) a clear description of context which includes detail on factors important for interpreting the results;

(iv) a clear description of the sample;

(v) a clear description of methodology, including systematic data collection methods;

(vi) analysis of the data by more than one researcher and

(vii) the inclusion of sufficient original data to mediate between data and interpretation.

Data synthesis

Three types of analyses were performed: (i) narrative synthesis of outcome evaluations, (ii) narrative synthesis of non-intervention studies and (iii) synthesis of intervention and non-intervention studies together.

For the last of these a matrix was constructed which laid out the barriers and facilitators identified by young people alongside descriptions of the interventions included in the in-depth systematic review of outcome evaluations. The matrix was stratified by four analytical themes to characterize the levels at which the barriers and facilitators appeared to be operating: the school, family and friends, the self and practical and material resources. This methodology is described further elsewhere [ 20, 22, 30 ].

From the matrix it is possible to see:

(i) where barriers have been modified and/or facilitators built upon by soundly evaluated interventions, and ‘promising’ interventions which need further, more rigorous, evaluation (matches) and

(ii) where barriers have not been modified and facilitators not built upon by any evaluated intervention, necessitating the development and rigorous evaluation of new interventions (gaps).

Figure 1 outlines the number of studies included at various stages of the review. Of the total of 7048 reports identified, 135 reports (describing 116 studies) met the first round of screening and were included in the descriptive map. The results of the map are reported in detail in a separate publication—see Shepherd et al. [ 23 ] (the report can be downloaded free of charge via http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk ). A subset of 22 outcome evaluations and 8 studies of young people's views met the criteria for the in-depth systematic review.

The review process.

Outcome evaluations

Of the 22 outcome evaluations, most were conducted in the United States ( n = 16) [ 31–45 ], two in Finland [ 46, 47 ], and one each in the UK [ 48 ], Norway [ 49 ], Denmark [ 50 ] and Australia [ 51 ]. In addition to the main focus on promoting healthy eating, they also addressed other related issues including cardiovascular disease in general, tobacco use, accidents, obesity, alcohol and illicit drug use. Most were based in primary or secondary school settings and were delivered by teachers. Interventions varied considerably in content. While many involved some form of information provision, over half ( n = 13) involved attempts to make structural changes to young people's physical environments; half ( n = 11) trained parents in or about nutrition, seven developed health-screening resources, five provided feedback to young people on biological measures and their behavioural risk status and three aimed to provide social support systems for young people or others in the community. Social learning theory was the most common theoretical framework used to develop these interventions. Only a minority of studies included young people who could be considered socially excluded ( n = 6), primarily young people from ethnic minorities (e.g. African Americans and Hispanics).

Following detailed data extraction and critical appraisal, only seven of the 22 outcome evaluations were judged to be methodologically sound. For the remainder of this section we only report the results of these seven. Four of the seven were from the United States, with one each from the UK, Norway and Finland. The studies varied in the comprehensiveness of their reporting of the characteristics of the young people (e.g. sociodemographic/economic status). Most were White, living in middle class urban areas. All attended secondary schools. Table I details the interventions in these sound studies. Generally, they were multicomponent interventions in which classroom activities were complemented with school-wide initiatives and activities in the home. All but one of the seven sound evaluations included and an integral evaluation of the intervention processes. Some studies report results according to demographic characteristics such as age and gender.

Soundly evaluated outcome evaluations: study characteristics (n = 7)

| Author/Country/Design | Population | Setting | Objectives | Providers | Programme content |

| Klepp and Wilhelmsen [ ], Norway, CT (+PE) | Seventh grade (13 years old) students | Secondary schools | Teachers and peer educators | ||

| Moon [ ], UK, CT (+PE) | Year 8 and Year 11 pupils (aged 11–16 years) | Secondary schools | |||

| Nicklas [ ], USA, RCT (+PE) | Ninth grade (age range 14–15 years) at start; 3-year longitudinal cohort intervention | High schools | Objective of the ‘Gimme 5’ programme Objective of the parent programme ‘5 a Day For Better Health’: | Teachers, health educators and school catering personnel | |

| Perry [ ], USA, RCT (+PE) | Ninth grade (14- to 15-year-old pupils) | Suburban high school | Teachers administered the programme in general, with 30 class-elected peer leaders leading the class-based sessions | ||

| Vartiainen [ ], Finland, RCT (+PE) | 12- to 16-year-old students | Secondary schools in the Karelia and Kuopio regions of Finland | Health educators, school nurses, peer educators, school teachers | ||

| Walter I and II [ ], USA, RCT (+PE) | Fourth grade (mean age 9 years at start); 5-year longitudinal cohort intervention | Elementary and junior high schools | Teachers delivered the classroom component. Health and education professionals conducted risk factor examination screening |

| Author/Country/Design | Population | Setting | Objectives | Providers | Programme content |

| Klepp and Wilhelmsen [ ], Norway, CT (+PE) | Seventh grade (13 years old) students | Secondary schools | Teachers and peer educators | ||

| Moon [ ], UK, CT (+PE) | Year 8 and Year 11 pupils (aged 11–16 years) | Secondary schools | |||

| Nicklas [ ], USA, RCT (+PE) | Ninth grade (age range 14–15 years) at start; 3-year longitudinal cohort intervention | High schools | Objective of the ‘Gimme 5’ programme Objective of the parent programme ‘5 a Day For Better Health’: | Teachers, health educators and school catering personnel | |

| Perry [ ], USA, RCT (+PE) | Ninth grade (14- to 15-year-old pupils) | Suburban high school | Teachers administered the programme in general, with 30 class-elected peer leaders leading the class-based sessions | ||

| Vartiainen [ ], Finland, RCT (+PE) | 12- to 16-year-old students | Secondary schools in the Karelia and Kuopio regions of Finland | Health educators, school nurses, peer educators, school teachers | ||

| Walter I and II [ ], USA, RCT (+PE) | Fourth grade (mean age 9 years at start); 5-year longitudinal cohort intervention | Elementary and junior high schools | Teachers delivered the classroom component. Health and education professionals conducted risk factor examination screening |

RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial; CT = controlled trial (no randomization); PE = process evaluation.

Separate evaluations of the same intervention in two populations in New York (the Bronx and Westchester County).

The UK-based intervention was an award scheme (the ‘Wessex Healthy Schools Award’) that sought to make health-promoting changes in school ethos, organizational functioning and curriculum [ 48 ]. Changes made in schools included the introduction of health education curricula, as well as the setting of targets in key health promotion areas (including healthy eating). Knowledge levels, which were high at baseline, changed little over the course of the intervention. Intervention schools performed better in terms of healthy food choices (on audit scores). The impact on measures of healthy eating such as choosing healthy snacks varied according to age and sex. The intervention only appeared possibly to be effective for young women in Year 11 (aged 15–16 years) on these measures (statistical significance not reported).

The ‘Know Your Body’ intervention, a cardiovascular risk reduction programme, was evaluated in two separate studies in two demographically different areas of New York (the Bronx and Westchester County) [ 45 ]. Lasting for 5 years it comprised teacher-led classroom education, parental involvement activities and risk factor examination in elementary and junior high schools. In the Bronx evaluation, statistically significant increases in knowledge were reported, but favourable changes in cholesterol levels and dietary fat were not significant. In the Westchester County evaluation, we judged the effects to be unclear due to shortcomings in methods reported.

A second US-based study, the 3-year ‘Gimme 5’ programme [ 40 ], focused on increasing consumption of fruits and vegetables through a school-wide media campaign, complemented by classroom activities, parental involvement and changes to nutritional content of school meals. The intervention was effective at increasing knowledge (particularly among young women). Effects were measured in terms of changes in knowledge scores between baseline and two follow-up periods. Differences between the intervention and comparison group were significant at both follow-ups. There was a significant increase in consumption of fruit and vegetables in the intervention group, although this was not sustained.

In the third US study, the ‘Slice of Life’ intervention, peer leaders taught 10 sessions covering the benefits of fitness, healthy diets and issues concerning weight control [ 41 ]. School functioning was also addressed by student recommendations to school administrators. For young women, there were statistically significant differences between intervention and comparison groups on healthy eating scores, salt consumption scores, making healthy food choices, knowledge of healthy food, reading food labels for salt and fat content and awareness of healthy eating. However, among young men differences were only significant for salt and knowledge scores. The process evaluation suggested that having peers deliver training was acceptable to students and the peer-trainers themselves.

A Norwegian study evaluated a similar intervention to the ‘Slice of Life’ programme, employing peer educators to lead classroom activities and small group discussions on nutrition [ 49 ]. Students also analysed the availability of healthy food in their social and home environment and used a computer program to analyse the nutritional status of foods. There were significant intervention effects for reported healthy eating behaviour (but not maintained by young men) and for knowledge (not young women).

The second ‘North Karelia Youth Study’ in Finland featured classroom educational activities, a community media campaign, health-screening activities, changes to school meals and a health education initiative in the parents' workplace [ 47 ]. It was judged to be effective for healthy eating behaviour, reducing systolic blood pressure and modifying fat content of school meals, but less so for reducing cholesterol levels and diastolic blood pressure.

The evidence from the well-designed evaluations of the effectiveness of healthy eating initiatives is therefore mixed. Interventions tend to be more effective among young women than young men.

Young people's views

Table II describes the key characteristics of the eight studies of young people's views. The most consistently reported characteristics of the young people were age, gender and social class. Socioeconomic status was mixed, and in the two studies reporting ethnicity, the young people participating were predominantly White. Most studies collected data in mainstream schools and may therefore not be applicable to young people who infrequently or never attend school.

Characteristics of young people's views studies (n = 8)

| Study | Aims and objectives | Sample characteristics |

| Dennison and Shepherd [ ] | ||

| Harris [ ] | ||

| McDougall [ ] | ||

| Miles and Eid [ ] | ||

| Roberts [ ] | ||

| Ross [ ] | ||

| Watt and Sheiham [ ] | ||

| Watt and Sheiham [ ] |

| Study | Aims and objectives | Sample characteristics |

| Dennison and Shepherd [ ] | ||

| Harris [ ] | ||

| McDougall [ ] | ||

| Miles and Eid [ ] | ||

| Roberts [ ] | ||

| Ross [ ] | ||

| Watt and Sheiham [ ] | ||

| Watt and Sheiham [ ] |

All eight studies asked young people about their perceptions of, or attitudes towards, healthy eating, while none explicitly asked them what prevents them from eating healthily. Only two studies asked them what they think helps them to eat healthy foods, and only one asked for their ideas about what could or should be done to promote nutrition.

Young people tended to talk about food in terms of what they liked and disliked, rather than what was healthy/unhealthy. Healthy foods were predominantly associated with parents/adults and the home, while ‘fast food’ was associated with pleasure, friendship and social environments. Links were also made between food and appearance, with fast food perceived as having negative consequences on weight and facial appearance (and therefore a rationale for eating healthier foods). Attitudes towards healthy eating were generally positive, and the importance of a healthy diet was acknowledged. However, personal preferences for fast foods on grounds of taste tended to dominate food choice. Young people particularly valued the ability to choose what they eat.

Despite not being explicitly asked about barriers, young people discussed factors inhibiting their ability to eat healthily. These included poor availability of healthy meals at school, healthy foods sometimes being expensive and wide availability of, and personal preferences for, fast foods. Things that young people thought should be done to facilitate healthy eating included reducing the price of healthy snacks and better availability of healthy foods at school, at take-aways and in vending machines. Will-power and encouragement from the family were commonly mentioned support mechanisms for healthy eating, while teachers and peers were the least commonly cited sources of information on nutrition. Ideas for promoting healthy eating included the provision of information on nutritional content of school meals (mentioned by young women particularly) and better food labelling in general.

Table III shows the synthesis matrix which juxtaposes barriers and facilitators alongside results of outcome evaluations. There were some matches but also significant gaps between, on the one hand, what young people say are barriers to healthy eating, what helps them and what could or should be done and, on the other, soundly evaluated interventions that address these issues.

Synthesis matrix

| Young people's views on barriers and facilitators | Interventions which address barriers or build on facilitators identified by young people | ||

| Barriers | Facilitators | Soundly evaluated interventions ( = 7) | Other evaluated interventions ( = 15) |

| ) | ) | ) ) ) ) | ) ) |

| ) | |||

| ) | ) | ||

| ) | ) as well as with adulthood ( ) ) | ) ). | ) ) |

| ) | ) ) | ) (see also ) ) ) ) | |

| ) ) | ) | ) ) ) as above | ) as above |

| ) | ) | ) | |

| ) | ) | ) ) | ) ) |

| ) ) | ) as above None identified—research gap | ||

| ) ) | ) ) | ) ) ) | ) ) |

| ) | |||

| ) | ) | ||

| ) | |||

| Young people's views on barriers and facilitators | Interventions which address barriers or build on facilitators identified by young people | ||

| Barriers | Facilitators | Soundly evaluated interventions ( = 7) | Other evaluated interventions ( = 15) |

| ) | ) | ) ) ) ) | ) ) |

| ) | |||

| ) | ) | ||

| ) | ) as well as with adulthood ( ) ) | ) ). | ) ) |

| ) | ) ) | ) (see also ) ) ) ) | |

| ) ) | ) | ) ) ) as above | ) as above |

| ) | ) | ) | |

| ) | ) | ) ) | ) ) |

| ) ) | ) as above None identified—research gap | ||

| ) ) | ) ) | ) ) ) | ) ) |

| ) | |||

| ) | ) | ||

| ) | |||

Key to young people's views studies: Y1 , Dennison and Shepherd [ 56 ]; Y2 , Harris [ 57 ]; Y3 , McDougall [ 58 ]; Y4 , Miles and Eid [ 59 ]; Y5 , Roberts et al. [ 60 ]; Y6 , Ross [ 61 ]; Y7 , Watt and Sheiham [ 62 ]; Y8 , Watt and Sheiham [ 63 ]. Key to intervention studies: OE1 , Baranowski et al. [ 31 ]; OE2 , Bush et al. [ 32 ]; OE3 , Coates et al. [ 33 ]; OE4 , Ellison et al. [ 34 ]; OE5 , Flores [ 36 ]; OE6 , Fitzgibbon et al. [ 35 ]; OE7 , Hopper et al. [ 64 ]; OE8 , Holund [ 50 ]; OE9 , Kelder et al. [ 38 ]; OE10 , Klepp and Wilhelmsen [ 49 ]; OE11 , Moon et al. [ 48 ]; OE12 , Nader et al. [ 39 ]; OE13 , Nicklas et al. [ 40 ]; OE14 , Perry et al. [ 41 ]; OE15 , Petchers et al. [ 42 ]; OE16 , Schinke et al. [ 43 ]; OE17 , Wagner et al. [ 44 ]; OE18 , Vandongen et al. [ 51 ]; OE19 , Vartiainen et al. [ 46 ]; OE20 , Vartiainen et al. [ 47 ]; OE21 , Walter I [ 45 ]; OE22 , Walter II [ 45 ]. OE10, OE11, OE13, OE14, OE20, OE21 and OE22 denote a sound outcome evaluation. OE21 and OE22 are separate evaluations of the same intervention. Due to methodological limitations, we have judged the effects of OE22 to be unclear. Y1 and Y2 do not appear in the synthesis matrix as they did not explicitly report barriers or facilitators, and it was not possible for us to infer potential barriers or facilitators. However, these two studies did report what young people understood by healthy eating, their perceptions, and their views and opinions on the importance of eating a healthy diet. OE2, OE12, OE16 and OE17 do not appear in the synthesis matrix as they did not address any of the barriers or facilitators.

In terms of the school environment, most of the barriers identified by young people appear to have been addressed. At least two sound outcome evaluations demonstrated the effectiveness of increasing the availability of healthy foods in the school canteen [ 40, 47 ]. Furthermore, despite the low status of teachers and peers as sources of nutritional information, several soundly evaluated studies showed that they can be employed effectively to deliver nutrition interventions.

Young people associated parents and the home environment with healthy eating, and half of the sound outcome evaluations involved parents in the education of young people about nutrition. However, problems were sometimes experienced in securing parental attendance at intervention activities (e.g. seminar evenings). Why friends were not a common source of information about good nutrition is not clear. However, if peer pressure to eat unhealthy foods is a likely explanation, then it has been addressed by the peer-led interventions in three sound outcome evaluations (generally effectively) [ 41, 47, 49 ] and two outcome evaluations which did not meet the quality criteria (effectiveness unclear) [ 33, 50 ].

The fact that young people choose fast foods on grounds of taste has generally not been addressed by interventions, apart from one soundly evaluated effective intervention which included taste testings of fruit and vegetables [ 40 ]. Young people's concern over their appearance (which could be interpreted as both a barrier and a facilitator) has only been addressed in one of the sound outcome evaluations (which revealed an effective intervention) [ 41 ]. Will-power to eat healthy foods has only been examined in one outcome evaluation in the in-depth systematic review (judged to be sound and effective) (Walter I—Bronx evaluation) [ 45 ]. The need for information on nutrition was addressed by the majority of interventions in the in-depth systematic review. However, no studies were found which evaluated attempts to increase the nutritional content of school meals.

Barriers and facilitators relating to young people's practical and material resources were generally not addressed by interventions, soundly evaluated or otherwise. No studies were found which examined the effectiveness of interventions to lower the price of healthy foods. However, one soundly evaluated intervention was partially effective in increasing the availability of healthy snacks in community youth groups (Walter I—Bronx evaluation) [ 45 ]. At best, interventions have attempted to raise young people's awareness of environmental constraints on eating healthily, or encouraged them to lobby for increased availability of nutritious foods (in the case of the latter without reporting whether any changes have been effected as a result).

This review has systematically identified some of the barriers to, and facilitators of, healthy eating with young people, and illustrated to what extent they have been addressed by soundly evaluated effective interventions.

The evidence for effectiveness is mixed. Increases in knowledge of nutrition (measured in all but one study) were not consistent across studies, and changes in clinical risk factors (measured in two studies) varied, with one study detecting reductions in cholesterol and another detecting no change. Increases in reported healthy eating behaviour were observed, but mostly among young women revealing a distinct gender pattern in the findings. This was the case in four of the seven outcome evaluations (in which analysis was stratified by gender). The authors of one of the studies suggest that emphasis of the intervention on healthy weight management was more likely to appeal to young women. It was proposed that interventions directed at young men should stress the benefits of nutrition on strength, physical endurance and physical activity, particularly to appeal to those who exercise and play sports. Furthermore, age was a significant factor in determining effectiveness in one study [ 48 ]. Impact was greatest on young people in the 15- to 16-year age range (particularly for young women) in comparison with those aged 12–13 years, suggesting that dietary influences may vary with age. Tailoring the intervention to take account of age and gender is therefore crucial to ensure that interventions are as relevant and meaningful as possible.

Other systematic reviews of interventions to promote healthy eating (which included some of the studies with young people fitting the age range of this review) also show mixed results [ 52–55 ]. The findings of these reviews, while not being directly comparable in terms of conceptual framework, methods and age group, seem to offer some support for the findings of this review. The main message is that while there is some evidence to suggest effectiveness, the evidence base is limited. We have identified no comparable systematic reviews in this area.

Unlike other reviews, however, this study adopted a wider perspective through inclusion of studies of young people's views as well as effectiveness studies. A number of barriers to healthy eating were identified, including poor availability of healthy foods at school and in young people's social spaces, teachers and friends not always being a source of information/support for healthy eating, personal preferences for fast foods and healthy foods generally being expensive. Facilitating factors included information about nutritional content of foods/better labelling, parents and family members being supportive; healthy eating to improve or maintain one's personal appearance, will-power and better availability/lower pricing of healthy snacks.

Juxtaposing barriers and facilitators alongside effectiveness studies allowed us to examine the extent to which the needs of young people had been adequately addressed by evaluated interventions. To some extent they had. Most of the barriers and facilitators that related to the school and relationships with family and friends appear to have been taken into account by soundly evaluated interventions, although, as mentioned, their effectiveness varied. Many of the gaps tended to be in relation to young people as individuals (although our prioritization of interventions at the level of the community and society may have resulted in the exclusion of some of these interventions) and the wider determinants of health (‘practical and material resources’). Despite a wide search, we found few evaluations of strategies to improve nutritional labelling on foods particularly in schools or to increase the availability of affordable healthy foods particularly in settings where young people socialize. A number of initiatives are currently in place which may fill these gaps, but their effectiveness does not appear to have been reported yet. It is therefore crucial for any such schemes to be thoroughly evaluated and disseminated, at which point an updated systematic review would be timely.

This review is also constrained by the fact that its conclusions can only be supported by a relatively small proportion of the extant literature. Only seven of the 22 outcome evaluations identified were considered to be methodologically sound. As illustrated in Table III , a number of the remaining 15 interventions appear to modify barriers/build on facilitators but their results can only be judged unclear until more rigorous evaluation of these ‘promising’ interventions has been reported.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that the majority of the outcome evaluations were conducted in the United States, and by virtue of the inclusion criteria, all the young people's views studies were UK based. The literature therefore might not be generalizable to other countries, where sociocultural values and socioeconomic circumstances may be quite different. Further evidence synthesis is needed on barriers to, and facilitators of, healthy eating and nutrition worldwide, particularly in developing countries.

The aim of this study was to survey what is known about the barriers to, and facilitators of, healthy eating among young people with a view to drawing out the implications for policy and practice. The review has mapped and quality screened the extant research in this area, and brought together the findings from evaluations of interventions aiming to promote healthy eating and studies which have elicited young people's views.

There has been much research activity in this area, yet it is disappointing that so few evaluation studies were methodologically strong enough to enable us to draw conclusions about effectiveness. There is some evidence to suggest that multicomponent school-based interventions can be effective, although effects tended to vary according to age and gender. Tailoring intervention messages accordingly is a promising approach which should therefore be evaluated. A key theme was the value young people place on choice and autonomy in relation to food. Increasing the provision and range of healthy, affordable snacks and meals in schools and social spaces will enable them to exercise their choice of healthier, tasty options.

We have identified that several barriers to, and facilitators of, healthy eating in young people have received little attention in evaluation research. Further work is needed to develop and evaluate interventions which modify or remove these barriers, and build on these facilitators. Further qualitative studies are also needed so that we can continue to listen to the views of young people. This is crucial if we are to develop and test meaningful, appropriate and effective health promotion strategies.

We would like to thank Chris Bonell and Dina Kiwan for undertaking data extraction. We would also like to acknowledge the invaluable help of Amanda Nicholas, James Thomas, Elaine Hogan, Sue Bowdler and Salma Master for support and helpful advice. The Department of Health, England, funds a specific programme of health promotion work at the EPPI-Centre. The views expressed in the report are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

- healthy diet

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| November 2016 | 97 |

| December 2016 | 30 |

| January 2017 | 142 |

| February 2017 | 474 |

| March 2017 | 551 |

| April 2017 | 531 |

| May 2017 | 288 |

| June 2017 | 223 |

| July 2017 | 194 |

| August 2017 | 160 |

| September 2017 | 274 |

| October 2017 | 457 |

| November 2017 | 534 |

| December 2017 | 1,913 |

| January 2018 | 2,369 |

| February 2018 | 2,421 |

| March 2018 | 3,801 |

| April 2018 | 3,998 |

| May 2018 | 2,929 |

| June 2018 | 2,177 |

| July 2018 | 2,422 |

| August 2018 | 2,469 |

| September 2018 | 2,635 |

| October 2018 | 3,102 |

| November 2018 | 4,124 |

| December 2018 | 2,786 |

| January 2019 | 2,687 |

| February 2019 | 3,644 |

| March 2019 | 4,985 |

| April 2019 | 4,055 |

| May 2019 | 3,480 |

| June 2019 | 2,876 |

| July 2019 | 3,013 |

| August 2019 | 2,524 |

| September 2019 | 2,360 |

| October 2019 | 2,100 |

| November 2019 | 2,117 |

| December 2019 | 1,595 |

| January 2020 | 1,884 |

| February 2020 | 2,068 |

| March 2020 | 1,833 |

| April 2020 | 1,953 |

| May 2020 | 970 |

| June 2020 | 1,058 |

| July 2020 | 1,152 |

| August 2020 | 931 |

| September 2020 | 1,518 |

| October 2020 | 1,548 |

| November 2020 | 1,761 |

| December 2020 | 1,207 |

| January 2021 | 1,211 |

| February 2021 | 1,440 |

| March 2021 | 1,910 |

| April 2021 | 1,531 |

| May 2021 | 1,253 |

| June 2021 | 670 |

| July 2021 | 580 |

| August 2021 | 548 |

| September 2021 | 763 |

| October 2021 | 1,058 |

| November 2021 | 1,009 |

| December 2021 | 816 |

| January 2022 | 697 |

| February 2022 | 824 |

| March 2022 | 1,047 |

| April 2022 | 1,053 |

| May 2022 | 935 |

| June 2022 | 504 |

| July 2022 | 391 |

| August 2022 | 436 |

| September 2022 | 694 |

| October 2022 | 909 |

| November 2022 | 790 |

| December 2022 | 489 |

| January 2023 | 764 |

| February 2023 | 601 |

| March 2023 | 938 |

| April 2023 | 755 |

| May 2023 | 686 |

| June 2023 | 594 |

| July 2023 | 452 |

| August 2023 | 419 |

| September 2023 | 582 |

| October 2023 | 840 |

| November 2023 | 593 |

| December 2023 | 522 |

| January 2024 | 811 |

| February 2024 | 717 |

| March 2024 | 866 |

| April 2024 | 1,003 |

| May 2024 | 1,080 |

| June 2024 | 333 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-3648

- Print ISSN 0268-1153

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 06 December 2017

Food for thought: how nutrition impacts cognition and emotion

- Sarah J. Spencer 1 ,

- Aniko Korosi 2 ,

- Sophie Layé 3 ,

- Barbara Shukitt-Hale 4 &

- Ruth M. Barrientos 5

npj Science of Food volume 1 , Article number: 7 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

153k Accesses

148 Citations

192 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neuroendocrine diseases

More than one-third of American adults are obese and statistics are similar worldwide. Caloric intake and diet composition have large and lasting effects on cognition and emotion, especially during critical periods in development, but the neural mechanisms for these effects are not well understood. A clear understanding of the cognitive–emotional processes underpinning desires to over-consume foods can assist more effective prevention and treatments of obesity. This review addresses recent work linking dietary fat intake and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid dietary imbalance with inflammation in developing, adult, and aged brains. Thus, early-life diet and exposure to stress can lead to cognitive dysfunction throughout life and there is potential for early nutritional interventions (e.g., with essential micronutrients) for preventing these deficits. Likewise, acute consumption of a high-fat diet primes the hippocampus to produce a potentiated neuroinflammatory response to a mild immune challenge, causing memory deficits. Low dietary intake of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids can also contribute to depression through its effects on endocannabinoid and inflammatory pathways in specific brain regions leading to synaptic phagocytosis by microglia in the hippocampus, contributing to memory loss. However, encouragingly, consumption of fruits and vegetables high in polyphenolics can prevent and even reverse age-related cognitive deficits by lowering oxidative stress and inflammation. Understanding relationships between diet, cognition, and emotion is necessary to uncover mechanisms involved in and strategies to prevent or attenuate comorbid neurological conditions in obese individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Investigating nutrient biomarkers of healthy brain aging: a multimodal brain imaging study

Neural correlates of obesity across the lifespan

Insights into the role of diet and dietary flavanols in cognitive aging: results of a randomized controlled trial

Introduction.

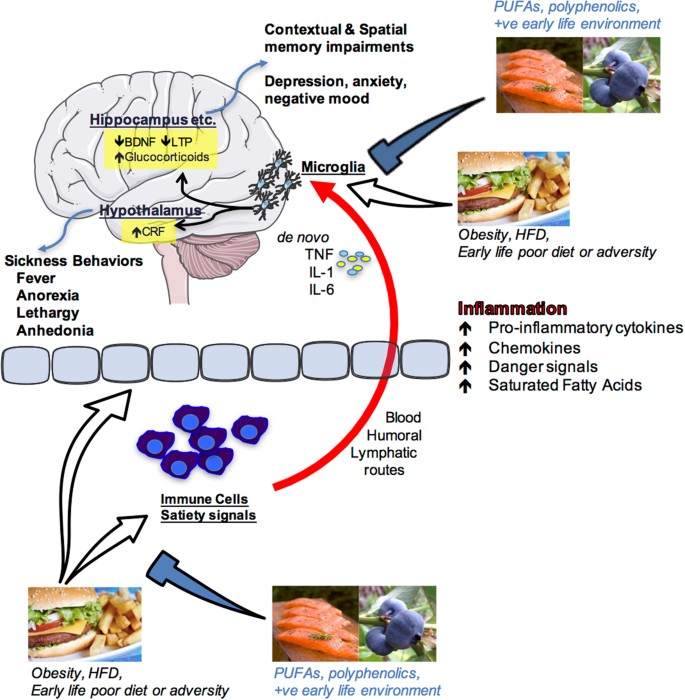

Cognitive and emotional dysfunctions are an increasing burden in our society. The exact factors and underlying mechanisms precipitating these disorders have not yet been elucidated. Next to our genetic makeup, the interplay between specific environmental challenges occurring during well-defined developmental periods seems to play an important role. Interestingly, such brain dysfunction most often co-occurs with metabolic disorders (e.g., obesity) and/or poor dietary habits; obesity and poor diet can lead to negative health implications including cognitive and mood dysfunctions, suggesting a strong interaction between these elements (Fig. 1 ). Obesity is a global phenomenon, with around 38% of adults and 18% of children and adolescents worldwide classified as either overweight or obese. 1 Even in the absence of obesity, poor diet is commonplace, 2 with, for instance, many eating foods that are highly processed and lacking in important polyphenols and anti-oxidants or that contain well-below the recommended levels of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). In this review, we will discuss the extent of, and mechanisms for, diet’s influence on mood and cognition during different stages of life, with a focus on microglial activation, glucocorticoids and endocannabinoids (eCBs).

Schematic depiction of how nutrition influences cognition and emotion. Overeating, obesity, acute high-fat diet consumption, poor early-life diet or early life adversity can produce an inflammatory response in peripheral immune cells and centrally as well as having impact upon the blood–brain interface and circulating factors that regulate satiety. Peripheral pro-inflammatory molecules (cytokines, chemokines, danger signals, fatty acids) can signal the immune cells of the brain (most likely microglia) via blood-borne, humoral, and/or lymphatic routes. These signals can either sensitize or activate microglia leading to de novo production of pro-inflammatory molecules such as interleukin-1beta (IL1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) within brain structures that are known to mediate cognition (hippocampus) and emotion (hypothalamus, amygdala, prefrontal cortex and others). Amplified inflammation in these regions impairs proper functioning leading to memory impairments and/or depressive-like behaviors. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), polyphenolics, and a positive (+ve) early life environment (appropriate nutrition and absence of significant stress or adversity) can prevent these negative outcomes by regulating peripheral and central immune cell activity. Images are adapted from Servier Medical Art, which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ . Salmon and hamburger images were downloaded from Bing.com with the License filter set to “free to share, and use commercially”. The blueberry image is courtesy of author Assistant Prof. Ruth Barrientos

Perinatal diet disrupts cognitive function long-term, a role for microglia

Poor diet in utero and during early postnatal life can cause lasting changes in many aspects of metabolic and central functions, including impairments in cognition and accelerated brain aging, 3 but see. 4 Maternal gestational diabetes and even a junk food diet in the non-diabetic can lead to metabolic complications, including diabetes and obesity in the offspring. 5 , 6 It can also cause changes in reward processing in the offspring brain such that they grow to prefer foods high in fat and sucrose. 7 , 8 Similarly, early introduction of solid food in children and high childhood consumption of fatty foods and sweetened drinks can accelerate weight gain and lead to metabolic complications long-term that may be associated with poorer executive function. 9 On the other hand, some dietary supplements can positively influence cognition, as is seen with supplementation of baby formula with long chain omega-3 PUFA improving cognition in babies. 10 In these randomized control trials (RCTs), an omega-3 PUFA-enriched formula beginning shortly after birth, or 6 weeks’ breast feeding, significantly improved performance of 9-month old babies on a problem solving task (a two-step task to retrieve a rattle, known to correlate with performance on IQ tasks).

From animal models, it is clear that the effects of diet in early life are far-reaching. Even obesity in rat sires (that play no part in rearing the offspring) leads to pancreatic beta cell dysfunction in female offspring, which can be passed on to the next generation. 11 Obesity and high-fat diet feeding in rat and mouse dams during pregnancy and lactation leads to impairments in several tests of mood, including those modeling depressive and anxious behaviors, as well as negatively impacting cognition. 12 Diet in the post-partum to weaning period can impact similar behaviors. 13

Additional to the impact of a prenatal diet, over-consumption of the mother’s milk during the first 3 weeks of a rat’s life leads to lasting obesity in males and females. 14 This neonatal overfeeding also disrupts cognitive function. For example, neonatally overfed rats perform poorly in the novel object recognition test and in the delayed spatial win-shift radial arm maze, as adults, compared with control rats. 15 These findings are interesting to compare with the effects of poor diet in adults where a longer-term high-fat diet (around 20 weeks in the rat) 16 , 17 , 18 and / or high-fat diet in conjunction with a pre-diabetic phenotype 19 is necessary to induce cognitive dysfunction. While there are no differences in post-learning synaptogenesis (synaptophysin) or apoptosis (caspase-3) to explain the effects seen in the neonatally overfed, these rats do have an impaired microglial response to the learning task. 15

Microglia are one of the major immune cell populations in the brain. In development, they are essential for synaptic pruning, while in a mature animal their major role is in mounting a pro-inflammatory immune response and phagocytosing pathogens and injured brain cells. 20 Hyper-activated microglia can lead to cognitive dysfunction through excess pro-inflammatory cytokine production causing impaired long-term potentiation-induction, reduced production of plasticity-related molecules including brain-derived neurotrophic factor and insulin-like growth factor-1, and reduced synaptic plasticity 20 However, an appropriate microglial response may also be essential for effective learning.

Neonatally overfed rats have more microglia in the CA1 region of the hippocampus at postnatal day 14, i.e., while they still have access to excess maternal milk and are undergoing accelerated weight gain. These microglia also have larger soma and retracted processes, indicative of a more activated phenotype. By the time these rats reach adulthood, there persists an increase in the area immunolabelled with microglial marker Iba1 in the dentate gyrus. In the neonatally overfed, the microglial response to a learning task is less robust than in controls. This effect is associated with a suppression of cell proliferation in control animals relative to the neonatally overfed, potentially to preserve existing neuronal networks and minimize novel inputs while learning takes place. 21 Interestingly, global inducible microglial and monocyte depletion can lead to improved performance in the Barnes maze, 22 suggesting withdrawal of microglial activity at specific learning phases is important for learning. These findings implicate microglia in the long-term effects of early life overfeeding on cognition suggesting normal microglia must be able to robustly respond to learning tasks and neonatal overfeeding impairs their ability to do so.

Neuroinflammatory processes, including the role of microglia, can clearly be impacted by neonatal diet and represent at least one contributing mechanism for how cognitive function is affected. Neuroinflammation and microglia can also be impacted by other early life events and play a significant role in how stress during development alters long-term physiology.

Early-life stress (ES) programs vulnerability to cognitive disorders

ES alters brain structure and function life-long, leading to increased vulnerability to develop emotional and cognitive disorders as is evident from several preclinical and clinical studies. 23 , 24 , 25 The exact underlying mechanisms for such programming remain elusive. There is extensive seminal work indicating a key role for sensory stimuli from the mother and neuroendocrine factors (e.g., stress hormones) in this programming, 26 , 27 however it has been recently suggested that these factors might act synergistically with metabolic and nutritional elements. 28 In fact, ES is associated with increased vulnerability to develop metabolic disorders such as obesity, which mostly co-occur with cognitive deficits, 29 , 30 and both ES and an adverse early nutritional environment lead to strikingly similar cognitive impairments later in life, 28 , 31 suggesting that metabolic factors and nutritional elements might mediate some of the ES effects on brain structure and function.

The brain has a very high demand for nutrients in this early period and nutritional imbalances affect normal neurodevelopment resulting in lasting cognitive deficits. 32 Understanding the role of metabolic factors and specific nutrients in this context is key to develop effective peripheral (e.g., nutritional) intervention strategies. A mouse model of the chronic ES of limited nesting and bedding material during the first postnatal week has been shown to lead to aberrant maternal care, which leads to cognitive decline in the ES offspring. 24 , 33 , 34

The hippocampus, a brain region key for cognitive functions, is permanently altered in its structure and function in these ES-exposed offspring. The hippocampus is in fact particularly sensitive to the early-life environment as it continues its development into the postnatal period. 35 Adult neurogenesis (AN) is a unique form of plasticity, which takes place in the hippocampus, consisting of the proliferation of neuronal progenitor cells that differentiate and mature into fully functional neurons that subsequently integrate into the existing hippocampal circuitry. These newly formed neurons are involved in various aspects of hippocampus-dependent learning and memory. 36 AN is affected persistently by ES 24 , 37 and, more precisely, while ES exposure initially increases neurogenesis (i.e., proliferation and differentiation of newborn cells) at postnatal day 9, at later time points (postnatal day 150), the survival of the newly born cells is reduced. 24 In addition, ES affects the neuroinflammatory profile in a lasting manner, with, for example, increased CD68 (phagocytic microglia expression) in adulthood. 38

Importantly, ES persistently affects peripheral adipose tissue metabolism as well. White adipose mass (WAT), plasma leptin (the adipokine released from the WAT) and leptin mRNA expression in WAT are persistently reduced in ES-exposed offspring. 39 In addition, exposure of ES mice to an unhealthy western style diet, leads to a higher increase in adiposity in these mice when compared to controls. These findings suggest that ES exposure leads to metabolic dysregulation and a greater vulnerability to develop obesity in a moderately obesogenic environment. Whether these metabolic alterations contribute to the ES-induced cognitive deficits warrants further investigation. 39

In addition to peripheral metabolism, ES-induced alterations in the nutritional composition of the dam’s milk, and/or nutrient intake/absorption by the pup 25 , 28 , 40 could have lasting consequences for brain structure and function. Indeed, the essential micronutrient, methionine, a critical component of the one-carbon (1-C) metabolism that is required for methylation, and for synthesis of proteins, phospholipids and neurotransmitters, is reduced after ES exposure in plasma and hippocampus of postnatal day 9 offspring. Importantly, a short supplementation of the maternal diet only during ES exposure with essential 1-C metabolism-associated micronutrients not only restores methionine levels peripherally as well as centrally, but rescues (some of) the effects of ES on hippocampal cognitive measures in adulthood and prevents the ES-induced hypothalamic-pituitary–adrenal axis hyperactivity at postnatal day 9. 25

These studies highlight the importance of studying metabolic factors and nutrients in the ES-induced effects on the brain. In the near future, it will be key to further understand the exact mechanisms mediating the effects of nutrients and metabolic factors and the windows of opportunity for interventions on brain function, as this will open entirely new avenues for targeted nutrition for vulnerable populations. However, while the early life period is a window of particular vulnerability to the programming effects of diet and other environmental influences, diet at other phases of life is also important in dictating mood and cognition.

Adult consumption of a high-fat diet: a vulnerability factor for hippocampal-dependent memory

Adults in developed countries are consuming diets higher in saturated fats and/or refined sugars than ever before. Indeed, recent reports show that approximately 12% of American adults’ daily energy intake comes from saturated fats and 13% from added sugars, 41 significantly more than what is recommended (5–10%) by the US Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services. Not surprisingly, these dietary habits have contributed to the increasing prevalence of obesity among adults, which is currently approximately 37% in the US, a sharp rise from the 13% prevalence rate of 1960. 42

These statistics are alarming because aside from its well-known provocation of cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes, obesity has now also been associated with mild cognitive impairments and dementia. There is growing evidence that neuroinflammation may underlie obesity-induced cognitive deficits. 9 Recently, studies have demonstrated that short-term consumption (1–7 days) of an unhealthy diet (e.g., high saturated fat and/or high sugar) triggers neuroinflammatory processes, suggesting that obesity per se may not be necessary to cause cognitive disruptions. 43 , 44 For the last 10–15 years, the hypothalamus has received the vast majority of the attention with regard to obesity-induced neuroinflammatory responses and functional declines, 45 perhaps due to its close proximity to the third ventricle, circumventricular organs, and mediobasal eminence, where inflammatory signals from the periphery have easier entry into the brain. Indeed, long chain saturated fatty acids have been shown to directly pass into the hypothalamus producing an inflammatory response there through activation of toll-like receptor 4 signaling. 46 , 47 This active passage of saturated fatty acids, however, has not been observed in the hippocampus, a key brain region that mediates learning and memory. 46 Nonetheless, high-fat diet consumption has been demonstrated to impair hippocampus-dependent memory function in humans and rodents. For example, compared to rodents that consumed a control diet, those that consumed a high-fat and/or high-sugar diet exhibited robust impairments in various types of memory (e.g., spatial, contextual), as indicated by weaker performances in the Y-maze, 48 radial arm maze, 15 novel object recognition task, 15 novel place recognition task, 44 , 49 Morris water maze, 50 and contextual fear conditioning. 18 , 51 Also, adult humans who consumed a high-fat diet for 5 days exhibited significantly reduced focused attention and reduced retrieval speed of information from working and episodic memory, compared with those who consumed a standard diet. 52

Many of these studies, and others, have shown that high-fat diet-induced cognitive deteriorations are accompanied by elevated neuroinflammatory markers or responses in the hippocampus. 15 , 18 , 44 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 53 However, the mechanisms by which these neuroinflammatory processes signal and/or affect the hippocampus are not entirely clear. There is growing evidence that high-fat diets may compromise the hippocampus by sensitizing the immune cells (most likely microglia) of this brain structure, thus priming the inflammatory response to subsequent challenging stimuli. 18 , 50 , 51 For example, one study demonstrated that adult rats that had eaten a high-fat diet for 5 months exhibited a sensitized hippocampus such that when they received a relatively mild stressor (a single, 2 s, 1.5 mA footshock) following a learning session the neuroinflammatory response in the hippocampus was potentiated compared to the response of rats that had eaten the regular chow, and this response led to deficits in long-term contextual memory. 18 Another study showed that just 3 days of consuming a high-fat diet was sufficient to sensitize the hippocampus of adult rats. Here, a low-dose peripheral immune challenge (with lipopolysaccharide; LPS) produced an exaggerated neuroinflammatory response in the hippocampus of these rats compared to those that consumed the regular chow, and also led to contextual memory deficits. 51

Significantly elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines in the hippocampus have been shown to deteriorate various mechanisms that enable synaptic plasticity (such as long-term potentiation), and thus long-term memory. 54 Sobesky et al. 51 demonstrated that high-fat diet consumption primes the cells of the hippocampus by elevating the glucocorticoid steroid hormone corticosterone in this region. Despite its classic role as an immunosuppressant, there is increasing evidence demonstrating that corticosterone can prime hippocampal microglia and potentiate the inflammatory response to a subsequent challenge. 55 , 56 , 57 For example, Frank et al. 55 elegantly showed that when corticosterone was elevated prior to a peripheral immune challenge (LPS), the resulting inflammatory response in the hippocampus was potentiated. In contrast, when corticosterone was elevated after the immune challenge, the neuroinflammatory response was suppressed. These findings suggest that the temporal relationship between the corticosterone increase and the immune challenge dictates whether a pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory response will result. 55 Sobesky et al. 51 found that rats that consumed the high-fat diet for 3 days exhibited significantly increased levels of corticosterone in their hippocampus compared to rats that consumed the regular chow or a novel macronutrient-matched control diet. This high-fat diet-induced corticosterone rise was accompanied by increases in the endogenous danger-associated molecular pattern high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), the interleukin (IL)-1 inflammasome-associated protein NLRP3, and the microglial activation marker cd11b. high-fat diet alone did not, however, elevate the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β unless rats were subsequently challenged with a low-dose of LPS. Thus, LPS challenge potentiated the pro-inflammatory response in the hippocampus of high-fat diet-fed rats compared to the response to LPS in chow-fed rats. To evaluate the role of corticosterone signaling in neuroinflammatory priming caused by consumption of high-fat diet, Sobesky et al. 51 administered the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, mifepristone, prior to high-fat diet consumption. This resulted in a normalized hippocampal IL-1β response to low-dose LPS. Furthermore, mifepristone significantly reduced the high-fat diet + LPS-induced expression of HMGB1, IκBα, and NLRP3. Moreover, mifepristone treatment effectively prevented contextual memory deficits caused by high-fat diet consumption combined with LPS challenge. These data provide strong evidence for the idea that (a) high-fat diet consumption increases corticosterone within the hippocampus, and (b) this corticosterone is a key mediator in sensitizing microglia or other immune cells of the hippocampus; (c) sensitized microglia produce a potentiated neuroinflammatory response to subsequent immune or stressful challenges, thus producing cognitive deficits. Notably, though, while high-fat diet per se can have significant detrimental impact on cognitive processes, specific dietary components may be able to reverse these effects, omega-3 PUFA are one such potentially beneficial component.

Dietary omega-3 PUFA regulate neuroinflammation and eCBs: role in mood and cognitive disorders

Since their discovery in the early 20th century, considerable attention has been paid to the roles of PUFA in brain functions. Omega-3 and omega-6 PUFA are essential fatty acids, meaning that they have to be provided by the diet. Western diet contains excessive amounts of omega-6 PUFA as compared to omega-3 leading to an unbalanced ratio between these two fatty acids with cardiovascular and brain health consequences. Essential omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids are found in green vegetables, seeds and nuts although coming from different sources with linolenic acid (LA, 18:2 omega-6) found in most plants, coconut and palm and α-linolenic acid (ALA, 18:3 omega-3) in green leafy vegetables, flax and walnuts. Once consumed, LA and ALA are metabolized into arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4 omega-6) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6 omega-3), respectively.

AA and DHA are the main omega-6 and omega-3 long chain PUFA found in the brain. Both long chain PUFA have pivotal roles in brain physiology as they regulate fundamental neurobiological processes, in particular the ones involved in cognition and mood. 58 , 59 AA and DHA are esterified to the phospholipid of neuronal and glial cell membranes with a total brain phospholipid proportion of around 10% for AA and 20% for DHA. Due to the limited capacity of the brain to synthesize long chain PUFA, preformed DHA can be provided by dietary supply of oily fishes. Hence, increased consumption of DHA-rich products results in a partial replacement of AA by DHA in brain cell membranes. 60 Conversely, a lower omega-3 PUFA intake leads to lower brain levels of DHA with increased AA levels. Higher AA and DHA are reported in women as compared to men, suggesting a gender difference in PUFA levels. 61 These differences could be linked to sex hormones as they differentially influence PUFA metabolism with estrogen stimulating, and testosterone inhibiting, the conversion of both omega-3 and omega-6 precursors into their respective long chain metabolites. However, whether these differences in PUFA have a role in specific brain diseases with a gender component has been poorly questioned and requires further investigation.

After its direct consumption and/or metabolization in the liver, DHA is increased in the blood and is likely to freely enter into the brain as non-esterified fatty acid. 58 More recently, Mfsd2a (major facilitator superfamily domain-containing protein 2a), which is expressed by brain endothelial cells and adiponectin receptor 1 in the retina, has been revealed to be important to DHA uptake and retention. 62

Abnormal omega-3 PUFA levels have been extensively described in both the peripheral tissues and in the brain of patients with mood disorders or cognitive decline, leading to a large number of RCTs aiming at evaluating the effectiveness of long chain omega-3 PUFA dietary supplementation on mood and cognitive disorders. 58 , 63 Overall, the results are discordant, due to the heterogeneity of methods used to evaluate the depressive and/or cognitive symptoms, the form, dose and duration of the omega-3 PUFA supplementation, the lack of evaluation of nutritional intake and metabolism of PUFA prior to starting the supplementation, or the lack of evaluation of genotype-associated risk factors. 64 However, despite the discrepancies in the results, it is important to note that several RCTs performed in patients with depressive disorders revealed an additional effect of long chain omega-3 PUFA supplementation to antidepressant treatments. 65 Of note, a recent study identifies that depressive patients presenting a high level of inflammatory markers are more responsive to long chain omega-3 PUFA supplementation. 66 This observation is highly relevant as these PUFA are potent regulators of inflammation 58 and inflammation is a crucial component of mood disorders. Concerning cognitive decline, despite poor positive results of PUFA dietary supplementation in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients, RCTs using DHA supplementation in subjects carrying the apolipoprotein E ε4 (APOE4) allele, a risk factor for AD, reveal an improvement of pre-dementia. 64 Overall, discrepancies in clinical studies strongly support the need for preclinical studies aimed at depicting the mechanisms of omega-3 PUFA on brain dysfunctions, which should help to better target populations at risk of cognitive and mood disorders. In addition, the consideration of omega-3 PUFA levels in food to cover the physiological requirement of these PUFA for an optimal brain function is a challenge for the food industry.

Through direct or indirect effects, DHA and AA modulate neurotransmission and neuroinflammation, which are key processes in cognition and mood. 58 , 59 Unesterified long chain PUFA are released from cell membranes upon the activation of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) to exert their effects. 67 Once released, AA and DHA are metabolized into bioactive mediators through cyclooxygenase (COX), lipoxygenases (LOX) and cytochrome P450. 68 The conversion of AA into several prostanoids, including prostaglandins (PG), leukotrienes (LT), thromboxanes (TX) and lipoxins (LX), is crucial in the progression of inflammation, including in the brain. 58 DHA is also metabolized through the COX/LOX pathways to generate metabolites with anti-inflammatory and pro-resolutive properties. 68 In the brain, LOX-derived specialized proresolving mediators (SPMs), neuroprotectin D1 (NPD1), resolvin D5 (RvD5), and maresin 1 (MaR1) are detected. 68 , 69 Some of these SPMs potently modulate neuroinflammation in vivo and in vitro, through their direct effect on microglia. 70 , 71 DHA and SPMs are impaired at the periphery and in the brains of AD patients. 72 , 73 Interestingly, decreased DHA distribution in AD patient brains correlates with synaptic loss rather than amyloid beta (Aβ) deposition. 74 In addition, DHA or SPMs promote phagocytosis of Aβ42 by microglia 75 and modulate microglia number and activation in vivo. 76 Whether SPMs play a role in the protective activity of long chain omega-3 PUFA in mood and cognitive disorders associated to neuroinflammation remains to be established.

eCBs are other key PUFA-derived lipid mediators in the brain. The main brain AA-derived eCBs are the fatty acid ethanolamides anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), while docosahexaenoylethanolamide (DHEA or synaptamide) is an eCB-like derived from DHA. 77 ECBs half-life in the brain is regulated by specific catabolizing enzymes fatty acid amide hydrolase for AEA and DHEA and monoacylglycerol lipase for 2-AG. Regarding neuroinflammatory processes, AA-derived eCBs are oxidized into bioactive PG by COX and LOX, which promote inflammation. 78 AEA and 2-AG bind to at least two cannabinoid receptors, type 1 (CB1) and type 2 (CB2), which are Gi/o protein-coupled with numerous signaling pathways in the brain. 79 , 80 DHEA has a lower binding affinity for CB1 and CB2 receptors as compared to AEA and 2-AG and rather bind GPR receptors, in particular GPR110 in the brain. The dietary omega-3/omega-6 PUFA ratio directly influences the proportion of ethanolamides derived from AA and DHA. 81 The modulation of eCB is accompanied by the impairment of neuronal CB1R activity and synaptic activity in several brain structures. 82 , 83 2-AG and AEA regulate synaptic function by suppressing excitatory and inhibitory synapse neurotransmitter release by acting as retrograde messengers at presynaptic CB1. 84 The importance of brain eCB signaling in the understanding of how altered dietary intake of PUFA correlates with a range of neurological disorders is of high interest. 81 However, other dietary factors may also contribute to improved cognition and prevention of cognitive disorders. Polyphenolic-rich foods are a further example that have been shown to have benefit, particularly in the context of aging.

Dietary interventions with polyphenolic-rich foods can improve neuronal and behavior deficits associated with aging

It is estimated that approximately 20% of the US total population will be older than 65 by the year 2050, which is almost double what it is today. 85 Additionally, the US is faced with an increasingly overweight/obese population that is at heightened risk for metabolic disorders, resulting in diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and concomitant behavioral impairment. Aging and metabolic dysregulation are both associated with numerous cognitive and motor deficits on tasks that require fine motor control, balance, short-term and long-term memory, or executive function. Studies in both humans and animal models have demonstrated that oxidative stress and inflammation, as well as impaired insulin resistance, are common features in cardio-metabolic and vascular disease, obesity, and age-related declines in cognitive and motor function. 86 Neuroinflammation occurs locally in the brain; however, peripheral inflammatory cells and circulating inflammatory mediators (e.g., cytokines) can also infiltrate the brain, and this occurs more readily as we age. 87 Therefore, strategies must be found to reduce oxidative and inflammatory vulnerability to age-related changes and reverse deficits in motor and cognitive function.

Targeting peripheral inflammation and insulin signaling could reduce insulin resistance and infiltration of inflammatory mediators into the brain and, as a result, reduce the incidence of a variety of age-related deficits. Studies have shown that plants, particularly colorful fruit or vegetable-bearing plants, contain polyphenolic compounds that have potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, 88 and increased fruit and vegetable intake has been associated with reduced fasting insulin levels. 89 Evidence is accumulating that consumption of these polyphenol-rich foods, particularly berry fruit, may be a strategy to forestall or even reverse age-related neuronal deficits resulting from neuroinflammation. 90 Recently this evidence has been extended to double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized human intervention studies that have demonstrated that the consumption of flavonoid/polyphenols is associated with benefits to cognitive function. 91

Preclinical studies have led to the hypothesis that the key to reducing the incidence of age-related deficits in behavior is to alter the neuronal environment with polyphenolic-rich foods like berry fruit, such that neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, and the vulnerability to them, would be reduced. In early studies with animal models, crude blueberry (BB) or strawberry extracts significantly attenuated 92 and reversed 93 age-related motor and cognitive deficits in senescent rodents. BB supplementation also protected 9 month old C57Bl/6 mice against the damaging effects of consuming a high-fat diet. 94 Novel object recognition memory was impaired by the high-fat diet, but blueberry supplementation prevented recognition memory deficits in a time-dependent manner. Spatial memory, as measured by the Morris water maze, was also improved after 5 months on the diets. 94 Subsequent research suggested that berry fruit polyphenols may possess a multiplicity of actions in addition to their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities. 90 Additionally, the anthocyanins contained in blueberries have been shown to enter the brain, and their concentrations were correlated with cognitive performance. 95