Getting started with qualitative research: developing a research proposal

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Community Nursing and Maternal & Child Health Care, School of Nursing, University of Navarra, Spain.

- PMID: 17494469

- DOI: 10.7748/nr2007.04.14.3.60.c6033

The aim of this article is to illustrate in detail important issues that research beginners may have to deal with during the design of a qualitative research proposal in nursing and health care. Cristina Vivar has developed a 17-step process to describe the development of a qualitative research project. This process can serve as an easy way to start research and to ensure a comprehensive and thorough proposal.

Publication types

- Data Collection / methods

- Data Interpretation, Statistical

- Decision Making

- Focus Groups

- Guidelines as Topic

- Information Dissemination

- Interviews as Topic

- Nursing Methodology Research / ethics

- Nursing Methodology Research / organization & administration*

- Nursing Theory

- Observation

- Pilot Projects

- Planning Techniques

- Qualitative Research*

- Research Design*

- Research Support as Topic / organization & administration

- Time Management

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

7 Writing a proposal

- Published: May 2018

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

When researchers plan to undertake qualitative research with a pilot or full RCT they write a proposal to apply for funding, seek ethical approval, or as part of their PhD studies. These proposals can be published in journals. Guidance for writing a proposal for the qualitative research undertaken with RCTs has been published, and there is existing guidance for writing proposals in related areas such as mixed methods research. In this chapter, existing guidance is introduced and built upon to offer comprehensive and detailed guidance for writing a proposal for the qualitative research undertaken with an RCT. There are challenges to writing these proposals and these are discussed and potential solutions proposed.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Privacy Policy

Home » How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

Table of Contents

How To Write a Research Proposal

Writing a Research proposal involves several steps to ensure a well-structured and comprehensive document. Here is an explanation of each step:

1. Title and Abstract

- Choose a concise and descriptive title that reflects the essence of your research.

- Write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes. It should provide a brief overview of your proposal.

2. Introduction:

- Provide an introduction to your research topic, highlighting its significance and relevance.

- Clearly state the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Discuss the background and context of the study, including previous research in the field.

3. Research Objectives

- Outline the specific objectives or aims of your research. These objectives should be clear, achievable, and aligned with the research problem.

4. Literature Review:

- Conduct a comprehensive review of relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings, identify gaps, and highlight how your research will contribute to the existing knowledge.

5. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to employ to address your research objectives.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques you will use.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate and suitable for your research.

6. Timeline:

- Create a timeline or schedule that outlines the major milestones and activities of your research project.

- Break down the research process into smaller tasks and estimate the time required for each task.

7. Resources:

- Identify the resources needed for your research, such as access to specific databases, equipment, or funding.

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources to carry out your research effectively.

8. Ethical Considerations:

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise during your research and explain how you plan to address them.

- If your research involves human subjects, explain how you will ensure their informed consent and privacy.

9. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

- Clearly state the expected outcomes or results of your research.

- Highlight the potential impact and significance of your research in advancing knowledge or addressing practical issues.

10. References:

- Provide a list of all the references cited in your proposal, following a consistent citation style (e.g., APA, MLA).

11. Appendices:

- Include any additional supporting materials, such as survey questionnaires, interview guides, or data analysis plans.

Research Proposal Format

The format of a research proposal may vary depending on the specific requirements of the institution or funding agency. However, the following is a commonly used format for a research proposal:

1. Title Page:

- Include the title of your research proposal, your name, your affiliation or institution, and the date.

2. Abstract:

- Provide a brief summary of your research proposal, highlighting the research problem, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes.

3. Introduction:

- Introduce the research topic and provide background information.

- State the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Explain the significance and relevance of the research.

- Review relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings and identify gaps in the existing knowledge.

- Explain how your research will contribute to filling those gaps.

5. Research Objectives:

- Clearly state the specific objectives or aims of your research.

- Ensure that the objectives are clear, focused, and aligned with the research problem.

6. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to use.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate for your research.

7. Timeline:

8. Resources:

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources effectively.

9. Ethical Considerations:

- If applicable, explain how you will ensure informed consent and protect the privacy of research participants.

10. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

11. References:

12. Appendices:

Research Proposal Template

Here’s a template for a research proposal:

1. Introduction:

2. Literature Review:

3. Research Objectives:

4. Methodology:

5. Timeline:

6. Resources:

7. Ethical Considerations:

8. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

9. References:

10. Appendices:

Research Proposal Sample

Title: The Impact of Online Education on Student Learning Outcomes: A Comparative Study

1. Introduction

Online education has gained significant prominence in recent years, especially due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes by comparing them with traditional face-to-face instruction. The study will explore various aspects of online education, such as instructional methods, student engagement, and academic performance, to provide insights into the effectiveness of online learning.

2. Objectives

The main objectives of this research are as follows:

- To compare student learning outcomes between online and traditional face-to-face education.

- To examine the factors influencing student engagement in online learning environments.

- To assess the effectiveness of different instructional methods employed in online education.

- To identify challenges and opportunities associated with online education and suggest recommendations for improvement.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study Design

This research will utilize a mixed-methods approach to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. The study will include the following components:

3.2 Participants

The research will involve undergraduate students from two universities, one offering online education and the other providing face-to-face instruction. A total of 500 students (250 from each university) will be selected randomly to participate in the study.

3.3 Data Collection

The research will employ the following data collection methods:

- Quantitative: Pre- and post-assessments will be conducted to measure students’ learning outcomes. Data on student demographics and academic performance will also be collected from university records.

- Qualitative: Focus group discussions and individual interviews will be conducted with students to gather their perceptions and experiences regarding online education.

3.4 Data Analysis

Quantitative data will be analyzed using statistical software, employing descriptive statistics, t-tests, and regression analysis. Qualitative data will be transcribed, coded, and analyzed thematically to identify recurring patterns and themes.

4. Ethical Considerations

The study will adhere to ethical guidelines, ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of participants. Informed consent will be obtained, and participants will have the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

5. Significance and Expected Outcomes

This research will contribute to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence on the impact of online education on student learning outcomes. The findings will help educational institutions and policymakers make informed decisions about incorporating online learning methods and improving the quality of online education. Moreover, the study will identify potential challenges and opportunities related to online education and offer recommendations for enhancing student engagement and overall learning outcomes.

6. Timeline

The proposed research will be conducted over a period of 12 months, including data collection, analysis, and report writing.

The estimated budget for this research includes expenses related to data collection, software licenses, participant compensation, and research assistance. A detailed budget breakdown will be provided in the final research plan.

8. Conclusion

This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes through a comparative study with traditional face-to-face instruction. By exploring various dimensions of online education, this research will provide valuable insights into the effectiveness and challenges associated with online learning. The findings will contribute to the ongoing discourse on educational practices and help shape future strategies for maximizing student learning outcomes in online education settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How To Write A Proposal – Step By Step Guide...

Grant Proposal – Example, Template and Guide

How To Write A Business Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Business Proposal – Templates, Examples and Guide

Proposal – Types, Examples, and Writing Guide

How to choose an Appropriate Method for Research?

Dissertations and research projects

- Book a session

- Planning your research

Developing a theoretical framework

Reflecting on your position, extended literature reviews, presenting qualitative data.

- Quantitative research

- Writing up your research project

- e-learning and books

- SkillsCheck This link opens in a new window

- ⬅ Back to Skills Centre This link opens in a new window

- Review this resource

What is a theoretical framework?

Developing a theoretical framework for your dissertation is one of the key elements of a qualitative research project. Through writing your literature review, you are likely to have identified either a problem that need ‘fixing’ or a gap that your research may begin to fill.

The theoretical framework is your toolbox . In the toolbox are your handy tools: a set of theories, concepts, ideas and hypotheses that you will use to build a solution to the research problem or gap you have identified.

The methodology is the instruction manual: the procedure and steps you have taken, using your chosen tools, to tackle the research problem.

Why do I need a theoretical framework?

Developing a theoretical framework shows that you have thought critically about the different ways to approach your topic, and that you have made a well-reasoned and evidenced decision about which approach will work best. theoretical frameworks are also necessary for solving complex problems or issues from the literature, showing that you have the skills to think creatively and improvise to answer your research questions. they also allow researchers to establish new theories and approaches, that future research may go on to develop., how do i create a theoretical framework for my dissertation.

First, select your tools. You are likely to need a variety of tools in qualitative research – different theories, models or concepts – to help you tackle different parts of your research question.

When deciding what tools would be best for the job of answering your research questions or problem, explore what existing research in your area has used. You may find that there is a ‘standard toolbox’ for qualitative research in your field that you can borrow from or apply to your own research.

You will need to justify why your chosen tools are best for the job of answering your research questions, at what stage they are most relevant, and how they relate to each other. Some theories or models will neatly fit together and appear in the toolboxes of other researchers. However, you may wish to incorporate a model or idea that is not typical for your research area – the ‘odd one out’ in your toolbox. If this is the case, make sure you justify and account for why it is useful to you, and look for ways that it can be used in partnership with the other tools you are using.

You should also be honest about limitations, or where you need to improvise (for example, if the ‘right’ tool or approach doesn’t exist in your area).

This video from the Skills Centre includes an overview and example of how you might create a theoretical framework for your dissertation:

How do I choose the 'right' approach?

When designing your framework and choosing what to include, it can often be difficult to know if you’ve chosen the ‘right’ approach for your research questions. One way to check this is to look for consistency between your objectives, the literature in your framework, and your overall ethos for the research. This means ensuring that the literature you have used not only contributes to answering your research objectives, but that you also use theories and models that are true to your beliefs as a researcher.

Reflecting on your values and your overall ambition for the project can be a helpful step in making these decisions, as it can help you to fully connect your methodology and methods to your research aims.

Should I reflect on my position as a researcher?

If you feel your position as a researcher has influenced your choice of methods or procedure in any way, the methodology is a good place to reflect on this. Positionality acknowledges that no researcher is entirely objective: we are all, to some extent, influenced by prior learning, experiences, knowledge, and personal biases. This is particularly true in qualitative research or practice-based research, where the student is acting as a researcher in their own workplace, where they are otherwise considered a practitioner/professional. It's also important to reflect on your positionality if you belong to the same community as your participants where this is the grounds for their involvement in the research (ie. you are a mature student interviewing other mature learners about their experences in higher education).

The following questions can help you to reflect on your positionality and gauge whether this is an important section to include in your dissertation (for some people, this section isn’t necessary or relevant):

- How might my personal history influence how I approach the topic?

- How am I positioned in relation to this knowledge? Am I being influenced by prior learning or knowledge from outside of this course?

- How does my gender/social class/ ethnicity/ culture influence my positioning in relation to this topic?

- Do I share any attributes with my participants? Are we part of a s hared community? How might this have influenced our relationship and my role in interviews/observations?

- Am I invested in the outcomes on a personal level? Who is this research for and who will feel the benefits?

One option for qualitative projects is to write an extended literature review. This type of project does not require you to collect any new data. Instead, you should focus on synthesising a broad range of literature to offer a new perspective on a research problem or question.

The main difference between an extended literature review and a dissertation where primary data is collected, is in the presentation of the methodology, results and discussion sections. This is because extended literature reviews do not actively involve participants or primary data collection, so there is no need to outline a procedure for data collection (the methodology) or to present and interpret ‘data’ (in the form of interview transcripts, numerical data, observations etc.) You will have much more freedom to decide which sections of the dissertation should be combined, and whether new chapters or sections should be added.

Here is an overview of a common structure for an extended literature review:

Introduction

- Provide background information and context to set the ‘backdrop’ for your project.

- Explain the value and relevance of your research in this context. Outline what do you hope to contribute with your dissertation.

- Clarify a specific area of focus.

- Introduce your research aims (or problem) and objectives.

Literature review

You will need to write a short, overview literature review to introduce the main theories, concepts and key research areas that you will explore in your dissertation. This set of texts – which may be theoretical, research-based, practice-based or policies – form your theoretical framework. In other words, by bringing these texts together in the literature review, you are creating a lens that you can then apply to more focused examples or scenarios in your discussion chapters.

Methodology

As you will not be collecting primary data, your methodology will be quite different from a typical dissertation. You will need to set out the process and procedure you used to find and narrow down your literature. This is also known as a search strategy.

Including your search strategy

A search strategy explains how you have narrowed down your literature to identify key studies and areas of focus. This often takes the form of a search strategy table, included as an appendix at the end of the dissertation. If included, this section takes the place of the traditional 'methodology' section.

If you choose to include a search strategy table, you should also give an overview of your reading process in the main body of the dissertation. Think of this as a chronology of the practical steps you took and your justification for doing so at each stage, such as:

- Your key terms, alternatives and synonyms, and any terms that you chose to exclude.

- Your choice and combination of databases;

- Your inclusion/exclusion criteria, when they were applied and why. This includes filters such as language of publication, date, and country of origin;

- You should also explain which terms you combined to form search phrases and your use of Boolean searching (AND, OR, NOT);

- Your use of citation searching (selecting articles from the bibliography of a chosen journal article to further your search).

- Your use of any search models, such as PICO and SPIDER to help shape your approach.

- Search strategy template A simple template for recording your literature searching. This can be included as an appendix to show your search strategy.

The discussion section of an extended literature review is the most flexible in terms of structure. Think of this section as a series of short case studies or ‘windows’ on your research. In this section you will apply the theoretical framework you formed in the literature review – a combination of theories, models and ideas that explain your approach to the topic – to a series of different examples and scenarios. These are usually presented as separate discussion ‘chapters’ in the dissertation, in an order that you feel best fits your argument.

Think about an order for these discussion sections or chapters that helps to tell the story of your research. One common approach is to structure these sections by common themes or concepts that help to draw your sources together. You might also opt for a chronological structure if your dissertation aims to show change or development over time. Another option is to deliberately show where there is a lack of chronology or narrative across your case studies, by ordering them in a fragmentary order! You will be able to reflect upon the structure of these chapters elsewhere in the dissertation, explaining and defending your decision in the methodology and conclusion.

A summary of your key findings – what you have concluded from your research, and how far you have been able to successfully answer your research questions.

- Recommendations – for improvements to your own study, for future research in the area, and for your field more widely.

- Emphasise your contributions to knowledge and what you have achieved.

Alternative structure

Depending on your research aims, and whether you are working with a case-study type approach (where each section of the dissertation considers a different example or concept through the lens established in your literature review), you might opt for one of the following structures:

Splitting the literature review across different chapters:

This structure allows you to pull apart the traditional literature review, introducing it little by little with each of your themed chapters. This approach works well for dissertations that attempt to show change or difference over time, as the relevant literature for that section or period can be introduced gradually to the reader.

Whichever structure you opt for, remember to explain and justify your approach. A marker will be interested in why you decided on your chosen structure, what it allows you to achieve/brings to the project and what alternatives you considered and rejected in the planning process. Here are some example sentence starters:

In qualitative studies, your results are often presented alongside the discussion, as it is difficult to include this data in a meaningful way without explanation and interpretation. In the dsicussion section, aim to structure your work thematically, moving through the key concepts or ideas that have emerged from your qualitative data. Use extracts from your data collection - interviews, focus groups, observations - to illustrate where these themes are most prominent, and refer back to the sources from your literature review to help draw conclusions.

Here's an example of how your data could be presented in paragraph format in this section:

Example from 'Reporting and discussing your findings ', Monash University .

- << Previous: Planning your research

- Next: Quantitative research >>

- Last Updated: May 29, 2024 10:57 AM

- URL: https://libguides.shu.ac.uk/researchprojects

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Anaesth

- v.60(9); 2016 Sep

How to write a research proposal?

Department of Anaesthesiology, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Devika Rani Duggappa

Writing the proposal of a research work in the present era is a challenging task due to the constantly evolving trends in the qualitative research design and the need to incorporate medical advances into the methodology. The proposal is a detailed plan or ‘blueprint’ for the intended study, and once it is completed, the research project should flow smoothly. Even today, many of the proposals at post-graduate evaluation committees and application proposals for funding are substandard. A search was conducted with keywords such as research proposal, writing proposal and qualitative using search engines, namely, PubMed and Google Scholar, and an attempt has been made to provide broad guidelines for writing a scientifically appropriate research proposal.

INTRODUCTION

A clean, well-thought-out proposal forms the backbone for the research itself and hence becomes the most important step in the process of conduct of research.[ 1 ] The objective of preparing a research proposal would be to obtain approvals from various committees including ethics committee [details under ‘Research methodology II’ section [ Table 1 ] in this issue of IJA) and to request for grants. However, there are very few universally accepted guidelines for preparation of a good quality research proposal. A search was performed with keywords such as research proposal, funding, qualitative and writing proposals using search engines, namely, PubMed, Google Scholar and Scopus.

Five ‘C’s while writing a literature review

BASIC REQUIREMENTS OF A RESEARCH PROPOSAL

A proposal needs to show how your work fits into what is already known about the topic and what new paradigm will it add to the literature, while specifying the question that the research will answer, establishing its significance, and the implications of the answer.[ 2 ] The proposal must be capable of convincing the evaluation committee about the credibility, achievability, practicality and reproducibility (repeatability) of the research design.[ 3 ] Four categories of audience with different expectations may be present in the evaluation committees, namely academic colleagues, policy-makers, practitioners and lay audiences who evaluate the research proposal. Tips for preparation of a good research proposal include; ‘be practical, be persuasive, make broader links, aim for crystal clarity and plan before you write’. A researcher must be balanced, with a realistic understanding of what can be achieved. Being persuasive implies that researcher must be able to convince other researchers, research funding agencies, educational institutions and supervisors that the research is worth getting approval. The aim of the researcher should be clearly stated in simple language that describes the research in a way that non-specialists can comprehend, without use of jargons. The proposal must not only demonstrate that it is based on an intelligent understanding of the existing literature but also show that the writer has thought about the time needed to conduct each stage of the research.[ 4 , 5 ]

CONTENTS OF A RESEARCH PROPOSAL

The contents or formats of a research proposal vary depending on the requirements of evaluation committee and are generally provided by the evaluation committee or the institution.

In general, a cover page should contain the (i) title of the proposal, (ii) name and affiliation of the researcher (principal investigator) and co-investigators, (iii) institutional affiliation (degree of the investigator and the name of institution where the study will be performed), details of contact such as phone numbers, E-mail id's and lines for signatures of investigators.

The main contents of the proposal may be presented under the following headings: (i) introduction, (ii) review of literature, (iii) aims and objectives, (iv) research design and methods, (v) ethical considerations, (vi) budget, (vii) appendices and (viii) citations.[ 4 ]

Introduction

It is also sometimes termed as ‘need for study’ or ‘abstract’. Introduction is an initial pitch of an idea; it sets the scene and puts the research in context.[ 6 ] The introduction should be designed to create interest in the reader about the topic and proposal. It should convey to the reader, what you want to do, what necessitates the study and your passion for the topic.[ 7 ] Some questions that can be used to assess the significance of the study are: (i) Who has an interest in the domain of inquiry? (ii) What do we already know about the topic? (iii) What has not been answered adequately in previous research and practice? (iv) How will this research add to knowledge, practice and policy in this area? Some of the evaluation committees, expect the last two questions, elaborated under a separate heading of ‘background and significance’.[ 8 ] Introduction should also contain the hypothesis behind the research design. If hypothesis cannot be constructed, the line of inquiry to be used in the research must be indicated.

Review of literature

It refers to all sources of scientific evidence pertaining to the topic in interest. In the present era of digitalisation and easy accessibility, there is an enormous amount of relevant data available, making it a challenge for the researcher to include all of it in his/her review.[ 9 ] It is crucial to structure this section intelligently so that the reader can grasp the argument related to your study in relation to that of other researchers, while still demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. It is preferable to summarise each article in a paragraph, highlighting the details pertinent to the topic of interest. The progression of review can move from the more general to the more focused studies, or a historical progression can be used to develop the story, without making it exhaustive.[ 1 ] Literature should include supporting data, disagreements and controversies. Five ‘C's may be kept in mind while writing a literature review[ 10 ] [ Table 1 ].

Aims and objectives

The research purpose (or goal or aim) gives a broad indication of what the researcher wishes to achieve in the research. The hypothesis to be tested can be the aim of the study. The objectives related to parameters or tools used to achieve the aim are generally categorised as primary and secondary objectives.

Research design and method

The objective here is to convince the reader that the overall research design and methods of analysis will correctly address the research problem and to impress upon the reader that the methodology/sources chosen are appropriate for the specific topic. It should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

In this section, the methods and sources used to conduct the research must be discussed, including specific references to sites, databases, key texts or authors that will be indispensable to the project. There should be specific mention about the methodological approaches to be undertaken to gather information, about the techniques to be used to analyse it and about the tests of external validity to which researcher is committed.[ 10 , 11 ]

The components of this section include the following:[ 4 ]

Population and sample

Population refers to all the elements (individuals, objects or substances) that meet certain criteria for inclusion in a given universe,[ 12 ] and sample refers to subset of population which meets the inclusion criteria for enrolment into the study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria should be clearly defined. The details pertaining to sample size are discussed in the article “Sample size calculation: Basic priniciples” published in this issue of IJA.

Data collection

The researcher is expected to give a detailed account of the methodology adopted for collection of data, which include the time frame required for the research. The methodology should be tested for its validity and ensure that, in pursuit of achieving the results, the participant's life is not jeopardised. The author should anticipate and acknowledge any potential barrier and pitfall in carrying out the research design and explain plans to address them, thereby avoiding lacunae due to incomplete data collection. If the researcher is planning to acquire data through interviews or questionnaires, copy of the questions used for the same should be attached as an annexure with the proposal.

Rigor (soundness of the research)

This addresses the strength of the research with respect to its neutrality, consistency and applicability. Rigor must be reflected throughout the proposal.

It refers to the robustness of a research method against bias. The author should convey the measures taken to avoid bias, viz. blinding and randomisation, in an elaborate way, thus ensuring that the result obtained from the adopted method is purely as chance and not influenced by other confounding variables.

Consistency

Consistency considers whether the findings will be consistent if the inquiry was replicated with the same participants and in a similar context. This can be achieved by adopting standard and universally accepted methods and scales.

Applicability

Applicability refers to the degree to which the findings can be applied to different contexts and groups.[ 13 ]

Data analysis

This section deals with the reduction and reconstruction of data and its analysis including sample size calculation. The researcher is expected to explain the steps adopted for coding and sorting the data obtained. Various tests to be used to analyse the data for its robustness, significance should be clearly stated. Author should also mention the names of statistician and suitable software which will be used in due course of data analysis and their contribution to data analysis and sample calculation.[ 9 ]

Ethical considerations

Medical research introduces special moral and ethical problems that are not usually encountered by other researchers during data collection, and hence, the researcher should take special care in ensuring that ethical standards are met. Ethical considerations refer to the protection of the participants' rights (right to self-determination, right to privacy, right to autonomy and confidentiality, right to fair treatment and right to protection from discomfort and harm), obtaining informed consent and the institutional review process (ethical approval). The researcher needs to provide adequate information on each of these aspects.

Informed consent needs to be obtained from the participants (details discussed in further chapters), as well as the research site and the relevant authorities.

When the researcher prepares a research budget, he/she should predict and cost all aspects of the research and then add an additional allowance for unpredictable disasters, delays and rising costs. All items in the budget should be justified.

Appendices are documents that support the proposal and application. The appendices will be specific for each proposal but documents that are usually required include informed consent form, supporting documents, questionnaires, measurement tools and patient information of the study in layman's language.

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used in composing your proposal. Although the words ‘references and bibliography’ are different, they are used interchangeably. It refers to all references cited in the research proposal.

Successful, qualitative research proposals should communicate the researcher's knowledge of the field and method and convey the emergent nature of the qualitative design. The proposal should follow a discernible logic from the introduction to presentation of the appendices.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

How To Write A Research Proposal

Link Copied

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on LinkedIn

Imagine this: you're sitting in your cluttered dorm room, surrounded by piles of books and stacks of notes. It's the middle of the night, and you're desperately trying to piece together your thoughts for that looming research proposal deadline. The pressure is on – you know this research proposal could be the ticket to kickstarting your academic career or securing that much-needed funding for your groundbreaking research idea. But how to write a research proposal? Don't worry, you're not alone. Making a research proposal can seem daunting, but fear not – with the right approach, it's entirely achievable. In this blog, we'll take you through each step of writing a research proposal, from understanding the basics to putting together a winning research proposal that grabs attention and gets results.

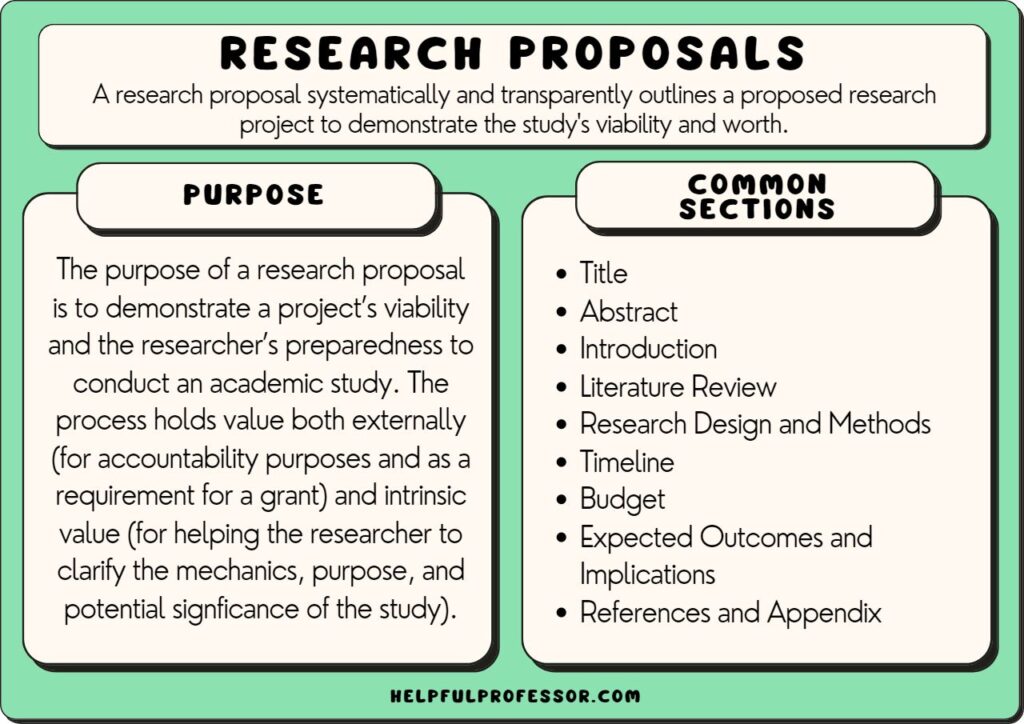

What is a research proposal used for, and why is it important?

A research proposal is important because it helps determine if there is enough expertise to support your research area. It is a key part of evaluating your application, showing that your project is feasible and fits within the institution's strengths. However, the proposal is just the beginning. Your ideas will likely change as you delve deeper into your research, but it provides a clear starting point. This initial plan helps both you and the institution understand the potential direction and significance of your research, laying solid foundations for your future.

What Things to keep in mind while writing a research proposal?

Academics often need to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might need to write one when applying to grad school or before starting your thesis or dissertation. A proposal helps you shape your research plans and shows why your project is valuable to funders, educational institutions, or supervisors.

- Relevance: Show your reader why your project is interesting, unique, and important.

- Context: Show that you are comfortable and knowledgeable in your field. Make it clear that you understand the current research on your topic.

- Approach: Explain why you chose your methodology. Show that you've thought carefully about the data, tools, and steps needed to do your research.

- Achievability: Make sure your project can be done within the time frame of your program or funding deadline.

- Tone: When you write research proposals or any academic work, keep it formal and objective. Remember, being clear and to the point is important. Keep your writing concise; being formal doesn't mean using fancy language.

How long should my research proposal be?

Usually, research proposals for bachelor’s and master’s theses are just a few pages. But for bigger projects like Ph.D. dissertations or asking for funding, they can be longer and more detailed. The main aim of a research proposal is to explain what your research will do clearly. So, while the length of the proposal matters less, what’s really important is that you cover all the necessary information in it.

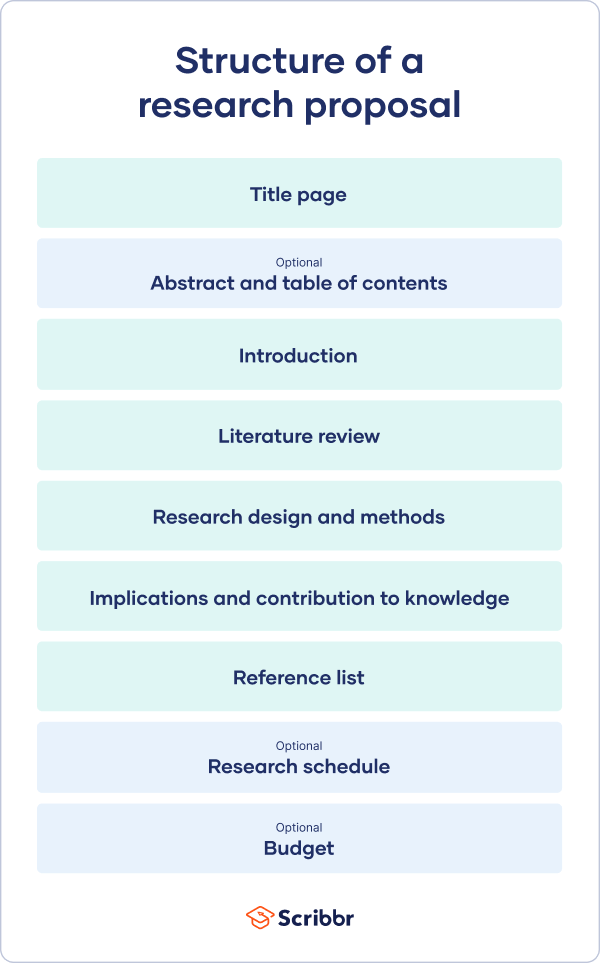

Sections of a research proposal

Research proposals usually have a simple layout. To meet the goals we talked about earlier, here’s how to write a research proposal:

If your proposal is really long, you might want to add a summary and a list of what's inside to help your reader find their way around. Just like your dissertation or thesis, your proposal should have a title page with the following

- The title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your school and department

Introduction section of research proposal

The beginning of your proposal is like the first pitch for your project. Make it clear and brief, explaining what you want to do and why.

In your introduction:

- Introduce your topic

- Provide background and context

- Explain the problem you're addressing and your research questions

To help you with your introduction, include:

- Who might care about your topic (like scientists or policymakers)

- What's already known about it

- What's still unknown

- How your research will add new information

- Why do you think this research matters

Literature review

As you begin, it's important to show that you know about the key research on your topic. A good literature review tells your reader that your project is based on solid existing knowledge. It also shows that you're not just repeating what others have said but adding something new.

In this part, explain how your project fits into the ongoing discussion in the field by:

- Comparing different theories, methods, and debates

- Looking at the strengths and weaknesses of different ideas

- Saying how you'll use past research in your own work - whether you'll build on it, challenge it, or bring it together with new ideas

If you're not sure where to start, check out our guide on writing a literature review.

Background significance

Your background section sets the stage for your research. Here, you explain why your topic matters and what questions you're trying to answer. It's like showing the backstory of your project, giving readers a clear picture of why it's worth their attention. In your research proposal, it's crucial to cover:

- Background and why your research is important

- Your field of study

- A brief look at existing research

- The main arguments and changes happening in your area

Research design, methods, and schedule

After looking at existing research, it's time to talk about your plans in this methodology section of a research proposal. One key thing to remember when learning how to write a research proposal is to include details about your research methods, like how you'll collect data and analyse it. Here's what your materials and methods in research proposal should cover:

- What kind of research you'll be doing - qualitative or quantitative, and whether you're gathering new data or using existing data.

- Whether your research is experimental, looking at connections, or describing things.

- Details about your data - if you're in social sciences, who you're studying and how you'll pick them.

- The tools you'll use to gather data - like experiments, surveys, or observations, and why they're right for your research.

When figuring out how to write a research proposal, start by clearly stating your research question and explaining why it's important and don't forget to include:

- Your timeline for the research.

- How much money do you need?

- Any problems you might face and how you'll deal with them.

Suppositions and Implications

Even though you won't know your research results until you do the work, you should have a clear idea of how your project will help and contribute to your field. Knowing how to write a research proposal also involves explaining the potential impact of your study. This part of your research proposal is extremely crucial because it explains why your research is necessary.

In this section on how to write a research proposal, make sure you cover the following:

- How your work might challenge current ideas, theories and assumptions in your field.

- Why your research is a good starting point for future studies.

- How your findings could be useful for professionals, teachers, and other researchers.

- The problems your research could potentially help solve.

- Any rules or guidelines that could change because of what you find.

- How your research could be used in schools or other places, and how that'll make things better.

Basically, in this section of a research proposal, you're not saying exactly what you'll find. Instead, you're explaining why whatever you discover will be important.

When applying for research funding, it's likely you'll need to provide a thorough budget. This demonstrates your projected costs for different aspects of your project. Be sure to review the funding body's guidelines to see what expenses they're willing to fund. For each item in your budget, include:

- Cost : How much money do you need?

- Why : Why do you need this money for your research?

- Source : How did you figure out this amount?

When you're making your budget, think about:

- Travel : Do you need to go somewhere to get your data? How will you get there, and how long will it take? What will you do there?

- Materials : Do you need any special tools or tech?

- Help : Do you need to hire someone to help with your research? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

In this section of a research proposal, you tie everything together. Your conclusion section, much like the conclusion paragraph of an essay, gives a quick rundown of your research proposal and strengthens the purpose you've laid out. It reminds the reader of the main points and emphasises why your research matters. It's your final chance to leave a lasting impression and make a case for the importance of your work.

Bibliography

Writing a bibliography is essential alongside your literature review. In this part of your research proposal structure, unlike the review, where you explain why you chose your sources and sometimes even question them. The bibliography just lists your sources and who wrote them.

Citing depends on the style guide, like MLA , APA , or Chicago . Each has its own rules, even for unusual sources like websites or speeches. If you don't need a full bibliography, a references list with just the sources you cited is enough. If unsure, ask your supervisor. Be sure to include:

- A list of references to important articles and texts you talked about in your research proposal.

- Choose sources that fit well with your proposed research.

Editing and proofreading a research proposal

When writing a research proposal, use the same six-step process you apply to all your writing tasks. Once you've drafted it, give it some time to cool off before proofreading. This helps you spot errors and gaps more effectively, ensuring a polished final version. Taking breaks between writing and revising enhances the quality of your work.

Common mistakes to avoid when writing a research proposal

When you’re writing a research proposal, avoid these common pitfalls:

Being too wordy

Remember, being formal doesn't mean using fancy words. In fact, it's best to keep your writing short and direct. The clearer and more concise you are about your purpose and goals, the stronger your proposal will be.

Failing to cite relevant sources

When you do research, you contribute to what we already know about your topic. Your proposal should mention important past research in your field and explain how your work relates to it. This shows not just why your work matters but also that you know your stuff. Referencing landmark studies gives your proposal credibility and strengthens your argument.

Focusing too much on minor issues

Your research likely has many important reasons behind it, but you don't need to list them all in your proposal. Including too many details can distract from your main goal, making your proposal weaker. Focus on the big, key issues you'll address. Save the smaller details for your actual research paper. Keeping your proposal focused strengthens your argument and makes it more effective.

Failing to make a strong argument for your research

Overloading your proposal with too many minor issues can weaken it significantly, as this approach is more subjective than others. Essentially, a research proposal is a form of persuasive writing. While it's presented objectively, the aim is to convince the reader to support your work. This applies universally whether your audience is your supervisor, department head, admissions board, funding provider, or journal editor. Keeping your proposal focused enhances its persuasiveness.

Polish your writing into a stellar proposal

When you're seeking approval for research, especially when funding is involved, your proposal needs to be perfect. Spelling mistakes, grammar errors, or awkward wording can hurt your credibility. Even if you've edited carefully, it's essential to double-check. Your research deserves the strongest proposal possible to make the best impression and secure the support it needs.

If you're unsure how to write a research proposal, don't worry! There are plenty of resources and examples available to guide you through the process. We hope this blog helped you answer your question of “how to write a research proposal”. Practice is key when learning how to write a research proposal, so don't be afraid to ask for feedback and revise your proposal until it's clear and compelling.

Frequently Asked Questions

How to write an abstract for a research proposal, what is the research proposal format , how to write a proposal for a research paper, how to write a dissertation proposal, how to write a phd proposal.

Your ideal student home & a flight ticket awaits

Follow us on :

Related Posts

16 Best Study Planning Apps For Students In 2024

.jpg)

15 Oldest Colleges In The US & Everything About Them!

Explore 10 Best Short Certificate Programs That Pay Well in 2024

Planning to Study Abroad ?

Your ideal student accommodation is a few steps away! Please fill in your details below so we can find you a new home!

We have got your response

amber © 2024. All rights reserved.

4.8/5 on Trustpilot