Top of page

Lesson Plan Exploring Community Through Local History: Oral Stories, Landmarks and Traditions

Students explore the local history of the community in which they live through written and spoken stories; through landmarks such as buildings, parks, restaurants, or businesses; and through traditions such as food, festivals and other events of the community or of individual families. Students learn the value of local culture and traditions as primary sources. They relate stories, landmarks and traditions of their community to history, place and environment.

Students will be able to:

- demonstrate knowledge of local history;

- develop interview skills;

- demonstrate knowledge of library research skills;

- analyze, interpret, and conduct research with primary sources.

Time Required

Lesson preparation.

- American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936-1940

- Explore Your Community : A Community Heritage Poster for the Classroom

- Learning About Immigration Through Oral History

- Local Legacies

- Oral History and Social History

Lesson Procedure

Possible teaching options are noted with individual activities.

- Introduce students to the American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936-1940 collection. Students read the Special Presentation of the collection. For additional resources for teaching from the American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936-1940 , see the lesson Using Oral History .

- Discuss how to structure an interview for the best results. Note that open-ended rather than yes/no questions get more detailed responses. For additional resources about types of interview questions, see the lesson Immigration and Oral History .

- Discuss the types of local landmarks, traditions and customs that could be project subjects, such as a plaque commemorating WW II veterans or a mural showing a state or local event. Decide in advance whether students will work alone, with a partner or with a small group; and whether to limit the number of projects on a particular landmark or tradition. Allow students to self-select a subject. For additional ideas on how to generate project ideas, see Explore Your Community: A Community Heritage Poster for the Classroom

- Assign students to take pictures of traditional customs, activities or landmarks for their project as homework.

- Provide access to books, materials, pictures, and artifacts from the school library to gain insight into the community's past.

- Have students visit the local public library and work with primary documents from the local history collection.

- Ask students to submit a plan for their interviews, including specific questions and possible candidates for the interview, for peer or teacher review before conducting their interviews. Students might benefit from a reminder to form open-ended questions and a review of interview etiquette. Possible interview candidates for a landmark might include people who work, visit, shop, or eat at the site, or other passersby. Students conduct interviews, taking notes. Students write a report of the interview, which should be evaluated based on the number and variety of people interviewed, the types of questions developed, and the types of responses elicited.

- Teach students how to combine their pictures and text in a multimedia presentation.

- Students share their presentations with the class. Presentations should include an explanation of how interviews were conducted, and what the student learned about the community. Class members write a summary and a critique of each presentation. (Teacher option: provide guidelines for the critiques, or generate them with the class before beginning the presentations. Students may evaluate all presentations, or be assigned particular presentations.)

The high school library will store the students’ work to be used as a resource by future students. Web projects may be shared on the school Web site.

Lesson Evaluation

Develop a rubric on your own or with the students.

- Students demonstrate understanding of interviewing techniques and oral traditions through a written essay about their interview and through their multimedia project.

- Students successfully prepare a multimedia presentation.

- Students present their local history project to the class in a clear and informative manner in order that other students in the class can write a summary and a critique of their presentation.

- Students submit a self-evaluation clarifying what they learned and what materials and experiences were valuable in learning about local history.

Marilyn Frenz and Mel Sanchez

The Importance of Teaching Local History in Primary School

Written by Dan

Last updated December 14, 2023

As a teacher, you know that one of the most important things you can do is teach your students about their local history. After all, it is the history that they will be living in!

Teaching local history helps students understand their community and its place worldwide. It also gives them a sense of pride in their hometown and its heritage.

So why is history so important to teach? Here are some tips on incorporating local history into your primary school curriculum.

Related : For more, check out our article on what needs to be taught in the history National Curriculum here.

Table of Contents

Why Local History?

Local history is an essential part of primary school education. It is not just the names and dates that children need to know, but also understanding their local heritage and connecting it to everyday life.

Students learn about local history and gain a sense of community and identity.

They can learn about their region’s customs, characters and significant moments, many of which have shaped our nation.

Building knowledge on particular areas can help enrich topics such as World War II by giving a personalised view.

The importance of teaching primary school learners about local history is thus evident; it allows them to confidently become active citizens who contribute to their communities with a better awareness of sociocultural differences and nuances.

Identity and Belonging

Studying local history is a unique and powerful way for children to understand their place within their community.

Through exploring influential people, key events, and shared experiences in local history, children can learn how these aspects have shaped their lives, creating a strong sense of identity and belonging.

By piecing together the stories of their ancestors, families, friends and neighbours, kids can form deeper connections with their environment and its people.

This provides a greater sense of self and a better appreciation of the present and future.

Learning local history can be both educational and inspirational to children, making them more receptive to diversity while helping them foster new relationships with others in the community.

Critical Thinking and Historical Research Skills

Teaching local history is integral to learning about the wider world and deepening our understanding of history.

Through studying local occurrences, greater awareness can be gained of how these events have affected, and continue to act, the more significant social and cultural consequences.

By engaging in critical thinking exercises and historical research about topics related to their immediate community, students can better understand the complexities of time, place and change within history.

Furthermore, local history allows teachers to utilise interesting primary sources readily accessible within the country or region that may not be considered when teaching more available content at a higher level.

Around The Curriculum

Local history is a fascinating way to engage students in the learning process and bring to life the subject matter of other areas, such as geography, science, and art.

By exploring the events and resources found in their backyard or nearby places, students can actively learn about the cultural and civil developments that have made these locations what they are today.

Using local sources such as museums, historical societies, interviews with elder community members, and archives of documents can provide students with valuable insights into different subject areas like rising sea levels in geography, the effects of climate change on science, and famous art pieces from a region’s culture.

By connecting lessons on various subjects with local background information, teachers can create dynamic experiences that leave an impact far beyond reading textbooks or taking notes.

How To Incorporate Local History Into The Curriculum

Incorporating local history into the classroom curriculum can be a great way to make learning fun and engaging.

Getting students involved in exploring the unique stories tied to their local region can elicit curiosity, creativity, and personal connections to the material.

There are plenty of ways for teachers to go about this, too- from hosting field trips to local landmarks, inviting guest speakers with interesting stories to share, organising research projects centred around elements of local history, or even simply sharing stories with vivid descriptions during class sessions.

Whatever methods are used, by engaging with local history, students have an opportunity to learn about their heritage and feel a part of something more significant in the process.

Exploring Online Resources for Teaching Local History

When teaching local history in the classroom, isn’t it exciting to think about the vast array of online resources at your disposal?

With the rise of digital technology, how we can engage students in learning has expanded exponentially. Let’s delve into some of these resources, shall we?

1. Digital Archives and Libraries

Can you imagine accessing centuries-old documents with a few clicks? Digital archives and libraries, such as the Library of Congress or your local historical society’s online database, offer a treasure trove of primary sources.

These can include letters, photographs, maps, and newspapers that shed light on your area’s history. Isn’t it fascinating how these archives can transport us back in time?

2. Virtual Tours and Webcams

Have you ever wished to take your students on a field trip without leaving the classroom? With virtual tours and webcams, you can do just that. Many local museums, historical sites, and landmarks now offer virtual experiences, providing a dynamic way to explore local history.

Can you visualize the excitement on your students’ faces as they virtually traverse these historical sites?

3. Online Documentaries and Videos

Isn’t it amazing how a well-crafted documentary can bring history to life? Platforms like YouTube or Vimeo host many short films, documentaries, and educational videos on various historical topics.

These visual resources can make local history more tangible and engaging for students. Can you feel the potential impact of these immersive visual narratives?

4. Interactive Maps

How about making geography lessons more interactive? Tools like Google Earth or Historical Map Chart allow you to create custom maps, highlighting significant locations and events in local history.

Can’t you see how this could enhance spatial understanding of historical events?

5. Educational Websites and Apps

Have you considered the potential of educational websites and apps? Sites like Khan Academy, TedEd, or apps like HistoryPin offer lessons and resources specifically designed for classroom use.

These platforms can provide a fresh, interactive approach to teaching local history. Can you envisage how this could transform your history lessons?

What Do You Think?

Teaching local history provides an invaluable learning opportunity for young learners, as it permits them to engage with the region they are in and learn more about their heritage.

By teaching local history in primary schools, children can develop an understanding of their community and the diverse range of cultures found within it.

Furthermore, this education encourages students to become active community and institution citizens.

With this in mind, we at The Teaching Couple invite our readers to reflect on the significance of educating our children about their local history and how this links with broader society.

Teaching local history in primary schools is essential for many reasons. It can help children develop a sense of identity and belonging, promote critical thinking and historical research skills, and be used to teach other subject areas such as geography, science, and art.

There are many ways to incorporate local history into the classroom curriculum. I invite readers to share their thoughts on teaching local history in primary schools.

Why is history important to teach in primary school?

History is essential to teach in primary school because it helps children develop a sense of identity, promotes critical thinking and historical research skills, and can be used to teach other subject areas such as geography, science, and art.

By engaging with local history, students can learn about their heritage and feel a part of something more significant while sparking curiosity and creativity.

How can local history be incorporated into geography lessons?

Local history can be incorporated into geography lessons by having students explore the unique stories tied to their local region.

This could involve taking field trips to local landmarks, inviting guest speakers with interesting stories to share, organising research projects around elements of local history, or even simply sharing stories with vivid descriptions during class sessions.

What elements of local history should be taught in primary school?

When teaching local history in primary school, focusing on elements relevant to the student’s lives and having a broader connection to society is essential. This could include exploring the region’s social and cultural diversity, significant events or figures from history, environmental aspects of the area, traditional customs or practices, and more.

By providing students with opportunities to learn about their community, teachers can promote a sense of belonging and empower students to be active citizens in the world around them.

What are some creative ways to teach local history?

There are many creative ways to teach local history, depending on the specific focus of the lesson. Some ideas include having students work on multimedia projects such as podcasts or videos, utilising interactive mapping exercises to trace the history of a region, hosting virtual field trips using online resources and images, having students write original works based on local stories, and so much more. Creativity and imagination go a long way when teaching local history in primary school.

Related Posts

About The Author

I'm Dan Higgins, one of the faces behind The Teaching Couple. With 15 years in the education sector and a decade as a teacher, I've witnessed the highs and lows of school life. Over the years, my passion for supporting fellow teachers and making school more bearable has grown. The Teaching Couple is my platform to share strategies, tips, and insights from my journey. Together, we can shape a better school experience for all.

1 thought on “The Importance of Teaching Local History in Primary School”

- Pingback: How To Incorporate Local History In Geography Lessons - The Teaching Couple

Comments are closed.

Join our email list to receive the latest updates.

Add your form here

- Our Mission

Developing a Local History Elective

Here’s how to find the resources to put together a course to teach middle and high school students about the history of where they live.

Schools aim to produce historically literate students with a keen awareness of the events that have impacted today’s world, including on a local level. Given our time constraints, however, teachers often must focus more on the big topics—wars, conflicts, economic developments, and the leaders who shaped the course of nations.

Local history frequently gets shortchanged.

With this in mind, we must ask ourselves: Are we falling short in educating our students about the history and culture of their own neighborhoods and communities?

In an attempt to diversify our electives, my administration asked the social studies department, of which I’m part, to create a new course. We settled on one that focuses on local history, and three of the five of us in the social studies department will be teaching it in the spring.

Here are the steps we’re taking to design our new local history elective, which we recommend for other educators.

Justifying the course

Before creating the course, ask yourself, “Why is this material important?”

The members of my department agreed that when students learn about the history of their own city, they have the knowledge of the people and events that influence their lives on a daily basis.

Local history also can help students appreciate their communities in new and dynamic ways. Young people are more likely to care about and give back to their hometown if they know something about it. On a lighter note, it’s fun to learn more about the names of people after whom buildings, streets, and parks are named.

The benefits of teaching local history are manifold, and devoting an entire course to such a curriculum allows teachers to explore the subject matter with rigor and depth.

Drawing on your and colleagues’ knowledge

Turn to your colleagues first. Think about what you and your department members already know. Work smarter, not harder, by harnessing everyone’s different capabilities. Our social studies teachers sat together one day and considered our different strengths and weaknesses in regard to content knowledge.

We identified one another’s own expertise (e.g., “I know a lot about the French and Indian War in our area”). Each member also shared where they felt weakest or most unprepared. Equipped with this information, we divided the work of curriculum building accordingly. Each of us agreed to work on topics about which we felt the most comfortable.

Reaching out to other schools

The idea behind the course, which we call Erie Experience, actually emerged from a class offered at a nearby school, which happens to be my alma mater. We borrowed the name and ideas from this class taught by my former teacher.

My department members and I knew that teachers at this school had a lot of information we could use, so a team member and I spoke with my former teacher, who provided us with support and information.

History centers and museums

We contacted our city’s history center; scheduled a time to meet with a volunteer, Mr. Jeff Sherry; and spent two professional days working with him. Mr. Sherry, who happened to be a former history teacher himself, provided us with many helpful resources, including relevant material and artifacts he was willing to share with our students.

Mr. Sherry offered to come to our class dressed in the clothing he wears during reenactments of different time periods. He also gave us contact information for experts in the area and other local research facilities that would be of help. We’ve since contacted these other specialists, including a group that runs a local history museum specializing in the French and Indian War and two documentarians at our PBS affiliate. We explored the history center’s collection and created a scavenger hunt that would get our kids moving and engaging with the center’s exhibits and artifacts. Perhaps most beneficially, the history center’s staff supplied us with a short book by a local historian, which will serve as our textbook.

Your community is probably filled with local historians who can be of tremendous help in planning this type of course.

The library

The public library is a magnificent resource too. In the two afternoons allotted to us for curriculum development, our department went to our public library, where the librarians graciously reserved a space for us to work with the digital collections librarian, who explained resources that are digitized and accessible online. These included maps, legal documents, and old photographs, all of which would be illuminating primary sources for our students.

Another librarian gave us a tour of the heritage room that had antiquarian books and maps, as well as modern scholarship. Much of it will be beneficial to us.

Building the curriculum

Once you’ve taken the above steps, create a rough schedule and divide the task of curriculum building among yourselves. We settled upon eight units that covered topics such as geography, First Peoples, the Colonial period, the Great Depression, and the present.

Our department members decided what field trips would be the most worthwhile, since obviously we can’t spend every day out of the building. We also chose what experts and specialists we’d like to invite to the classroom to supplement certain lessons.

Local history is your history

Local history is important. It connects our students to their community’s past, and it helps them understand why their cities and neighborhoods look, feel, and behave the way they do.

More important, knowing about their hometown is a key step toward young people caring about hometown issues and trying to improve the places in which they live. Local-history education plants the seeds of community engagement.

Even if you can’t develop an entire course devoted to the subject, consider reaching out to people and places like those above to add local flair to your social studies class.

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

Investigating Local History

Vintage Saint Paul Minnesota Postcard, The High Bridge And Harriet Island, Printed In USA, circa 1910s.

Public Domain Images

Our Teacher's Guide provides compelling questions, links to humanities organizations and local projects, and research activity ideas for integrating local history into humanities courses using a collection of NEH and State Council funded digital encyclopedias about the history, politics, geography, and culture of many U.S. states and territories. Note: Not every state and territory has produced an encyclopedia. Resources for historical , humanities , and arts councils are available for all states and territories.

Guiding Questions

Who lives in your state or territory?

How has the function and structure of your state or territorial government changed over time?

What artistic and cultural contributions have individuals and groups made to your state or territory and the United States?

What technological innovations have been created in your state or territory and how have they affected the people, environment, and culture?

How are local history and culture related to what you are studying?

"It is important for all of us to appreciate where we come from and how that history has really shaped us in ways that we might not understand." — Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court

Since April 2001 , the National Endowment for the Humanities has made grant funds available for all 50 states, all five U.S. territories, and the District of Columbia to create comprehensive online encyclopedias. Included below with the state encyclopedias that have been created to date are links to state humanities councils, arts councils, and historical society websites in the interest of telling as full a story as possible about history and the humanities across the United States.

- Alabama Encyclopedia

- Alabama Humanities Council

- Alabama Historical Marker Program

- Alabama Historical Commission

- Alabama State Council on the Arts

- Alaska Encyclopedia

- Alaska Humanities Forum

- Alaska Historical Society

- Alaska State Council on the Arts

American Samoa

- Amerika Samoa Humanities Council

- American Samoa Historic Preservation Office

- American Samoa Arts Council

- Arizona Humanities Council

- Arizona Historical Society

- Arizona Commission on the Arts

- Arkansas Encyclopedia

- Arkansas Humanities Council

- Arkansas Historical Marker Program

- Arkansas Historical Society

- Arkansas Arts Council

- California Humanities Council

- California Historical Resources

- California Historical Society

- California Arts Council

- Colorado Encyclopedia

- Colorado Humanities Council

- Colorado Historical Society

- Colorado Creative Industries

Connecticut

- Connecticut Encyclopedia

- Connecticut Humanities Council

- Connecticut Historical Society

- Connecticut Arts Alliance

- Delaware Humanities Council

- Delaware Historical Markers Program

- Delaware Historical Society

- Delaware Division of the Arts

District of Columbia

- Washington, D.C. Humanities Council

- Historical Society of Washington, D.C.

- D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities

- Florida Encyclopedia

- Florida Humanities Council

- Florida Historical Markers Program

- Florida Historical Society

- Florida Council on Arts and Culture

- Georgia Encyclopedia

- Georgia Humanities Council

- Georgia Historical Markers Program

- Georgia Historical Society

- Georgia Arts Council

- Guam Encyclopedia

- Guam Humanities Council

- Guam History

- Guam Council on the Arts

- Hawai'i Humanities Council

- Hawai'i Historical Society

- Hawai'i State Foundation on Culture and the Arts

- Idaho Humanities Council

- Idaho Historical Markers Program

- Idaho State Historical Society

- Idaho Commission on the Arts

- Illinois Humanities Council

- Illinois Historical Markers Program

- Illinois State Historical Society

- Illinois Arts Council Agency

- Indiana Humanities Council

- Indiana Historical Markers Program

- Indiana Historical Society

- Indiana Arts Commission

- Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs

- Iowa Humanities Council

- State Historical Society of Iowa

- Iowa Arts Council

- Kansas Encyclopedia

- Kansas Humanities Council

- Kansas Historical Markers Program

- Kansas Historical Society

- Kentucky Humanities Council

- Kentucky Historical Marker Program

- Kentucky Historical Society

- Kentucky Arts Council

- Louisiana Encyclopedia

- Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities

- Louisiana Historical Markers

- Louisiana Historical Society

- Louisiana Arts Council

- Maine Humanities Council

- Maine Historical Society

- Maine Arts Commission

Maryland Humanities Council

Maryland Historical Marker Program

Maryland Historical Society

Maryland State Arts Council

Massachusetts

- Massachusetts Encyclopedia

- Massachusetts Humanities Council

- Massachusetts Historical Society

- Massachusetts Cultural Council

- Michigan Humanities Council

- Michigan Historical Marker Program

- Historical Society of Michigan

- Michigan Council for Arts and Cultural Affairs

- Minnesota Encyclopedia

- Minnesota Humanities Center

- Minnesota Historical Society

- Minnesota Arts Board

Mississippi

- Mississippi Encyclopedia

- Mississippi Humanities Council

- Mississippi Historical Marker Program

- Mississippi Historical Society

- Mississippi Arts Commission

- Missouri Encyclopedia (beta)

- Missouri Humanities Council

- Missouri Historical Society

- Missouri Arts Council

- Montana Humanities Council

- Montana Historical Society

- Montana Arts Council

- Nebraska Encyclopedia

- Nebraska Humanities Council

- Nebraska Historical Marker Program

- Nebraska Historical Society

- Nebraska Arts Council

- Nevada Encyclopedia

- Nevada Humanities Council

- Nevada Historical Marker Program

- Nevada Historical Society

- Nevada Arts Council

New Hampshire

- New Hampshire Humanities Council

- New Hampshire Historical Highway Markers Program

- New Hampshire Historical Society

- New Hampshire State Council on the Arts

- New Jersey Humanities Council

- New Jersey Historical Society

- New Jersey State Council on the Arts

- New Mexico Humanities Council

- New Mexico Scenic Historic Markers Program

- New Mexico Office of the State Historian

- New Mexico Arts Council

- New York Humanities Council

- New York Historical Markers

- New-York Historical Society

- New York State Council on the Arts

North Carolina

- North Carolina Encyclopedia

- North Carolina Humanities Council

- North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program

- North Carolina Historical Society

- North Carolina Arts Council

North Dakota

North Dakota Humanities Council

North Dakota Historic Markers Program

State Historical Society of North Dakota

North Dakota Council on the Arts

Northern Mariana Islands

- Northern Marianas Humanities Council

- Northern Mariana Islands Museum of History and Culture

- Northern Mariana Islands Arts Council

- Ohio Encyclopedia

- Ohio Humanities Council

- Ohio Historical Marker Program

- Ohio Historical Society

- Ohio Arts Council

- Oklahoma Encyclopedia

- Oklahoma Humanities Council

- Oklahoma Historical Marker Program

- Oklahoma Historical Society

- Oklahoma Arts Council

- Oregon Encyclopedia

- Oregon Humanities Council

- Oregon Historical Marker Program

- Oregon Historical Society

- Oregon Arts Commission

Pennsylvania

- Pennsylvania Encyclopedia

- Pennsylvania Humanities Council

- Pennsylvania Historical Marker Program

- Pennsylvania Historical Society

- Pennsylvania Council on the Arts

Puerto Rico

- Puerto Rico Encyclopedia

- Puerto Rico Humanities Council

- National Museum of Arts and Culture

Rhode Island

- Rhode Island Humanities Council

- Rhode Island Historical Society

- Rhode Island State Council on the Arts

South Carolina

South Carolina Encyclopedia

- South Carolina Humanities Council

- South Carolina Historical Markers Program

- South Carolina Historical Society

- South Carolina Arts Commission

South Dakota

- South Dakota Humanities Council

- South Dakota Historical Marker Program

- South Dakota State Historical Society

- South Dakota Arts Council

- Tennessee Encyclopedia

- Tennessee Humanities Council

- Tennessee Historical Society

- Tennessee Arts Commission

- Texas Encyclopedia

- Texas Humanities Council

- Texas Historical Marker Program

- Texas Historical Association

- Texas Commission on the Arts

Utah Encyclopedia

- Utah Humanities Council

- Utah Historical Marker Program

- Utah Historical Society

- Utah Arts Council

- Vermont Humanities Council

- Vermont Roadside Historic Marker Program

- Vermont Historical Society

- Vermont Arts Council

Virgin Islands

- Virgin Islands Council on the Arts

- Virginia Encyclopedia

- Virginia Humanities Council

- Virginia Historical Highway Marker Program

- Virginia Historical Society

- Virginia Commission for the Arts

- Washington Encyclopedia

- Washington Humanities Council

- Washington Historical Highway Markers Program

- Washington Historical Society

- Washington Arts Commission

West Virginia

- West Virginia Encyclopedia

- West Virginia Humanities Council

- West Virginia Highway Historical Marker Program

- West Virginia Historical Society

- West Virginia Arts Council

- Wisconsin Humanities Council

- Wisconsin Historical Markers Program

- Wisconsin Historical Society

- Wisconsin Arts Board

- Wyoming Encyclopedia

- Wyoming Humanities Council

- Wyoming Historical Marker Program

- Wyoming Historical Society

- Wyoming Arts Council

A place-responsive approach to teaching U.S. history and culture can bring lessons alive for students and help close gaps that emerge when looking to answer the question of relevancy and application in students's lives. The lesson ideas below blend concepts, content, and skill building for investigating change over time when studying time and place.

Designing Compelling Questions

Inquiry into the local begins with a question. Students can design their own question based on a topic or event of interest or being studied, or they can work with the following: How have events and individuals shaped the history and culture of this place?

Questions for teachers and students to consider when planning:

- What was the last topic studied that included connections to the local?

- What individuals, organizations, and other local resources can be included in this investigation?

- Does this project warrant an oral history component?

- Whose perspectives will be included when examining local history and culture?

- What monuments, markers, and other relevant identifiers of local history already exist?

- What is considered common knowledge and what has been mythologized within local history?

- Who can be part of an audience for students to present their work to during this project?

- How has the local changed over time due to innovation, economics, and movement of people?

- How did the states get their shapes? The above video offers a preview of the the series produced by the History Channel that explored the often quirky reasons for why state borders formed the outlines we know today.

Researching with Local Newspapers

Chronicling America provides access to local and national newspapers dating back to the 17th century. Use the "search by state" feature to find local newspapers that can be used to teach primary source research skills such as gathering and evaluating information, comparative analysis, critical thinking, and the use of archival technology. You will also find collections of newspaper articles related to significant events, people, and eras in U.S. history and can search for newspapers published for and by multiple ethnic groups in the United States.

Sample questions to investigate when using Chronicling America to teach local history:

- How did the local press report on the happenings of the civil war?

- How did the press in your state or territory respond to the outbreak of WWI?

- What did the editorials in your state or territory newspapers have to say about a landmark Supreme Court ruling?

- What does an analysis of advertisements included in newspapers tell you about culture and consumerism?

- How have changes in journalism and media affected how news is reported?

Suggestions for incorporating Chronicling America into your research and more activity ideas are available at our Chronicling America Teacher's Guide .

Researching with Digital Maps

Living New Deal is a crowdsourcing project launched by the University of California, Berkeley in 2007 to identify, map, and analyze the national effects of President Roosevelt’s New Deal. Since its inception, the project has digitally documented over 16,000 New Deal public works and art sites across the U.S. The national map contains plot-points that provide information and photographs about each site, making it possible for students to investigate how New Deal projects transformed their local and state communities. The project also includes maps and guides for prominent New Deal buildings and murals in Washington, D.C., New York City, and San Francisco. The crowdsourcing aspect of the project provides students the ability to learn how to research and document historic and cultural sites and their guide for New Deal sleuths explains how the public can contribute to the project. This interactive, crowdsourcing project pairs well with EDSITEment’s Landmarks of American History and Culture Teacher’s Guide for research projects on local and state history and culture.

Digitally Documenting Local History

This NEH-funded educational website and mobile application guides the public to thousands of historical and cultural sites throughout the United States. Users can contribute to a growing database of projects designed to tell the history of places using photographs, mobile technology, and research on historical sites and events.

Activity ideas for using CLIO

Students tend to observe a lot as they move between school and home, thus making the spaces between those locations educative. Place-based learning can help bridge past and present while also asking students to reflect on their experiences and the relevance of the local to their lives. By using CLIO , students have an opportunity to document the past, analyze change over time, and evaluate the processes and forces at work in relation to place-making and history.

Starting the Inquiry

The following questions are designed to catalyze student research projects on local history and draw upon personal experiences and observations in the places where they live, play, work, and go to school. Students are encouraged to design their own questions as they select topics, eras, events, and places to investigate.

- What events of significance occurred 10, 100, or even 250 years ago in your area?

- How has the local environment (natural and physical) changed over time?

- To what extent are the local developments and events you have highlighted tied to national events?

- Who are the schools in your area named after and why?

- Why were monuments or other historical markers erected in your area?

- What local traditions and events are still practiced by members of the community?

Researching Place and Time

After students have selected a topic (which might be a local place), they will need to conduct research to learn more before the final stage that includes capturing photos and digitally organizing their CLIO project. The following list offers sources of information and methods for collecting information.

Historical Societies and Libraries —State, county, and local historical societies, along with public and university libraries provide free access to historical archives. Working with archivists and librarians, students can ask questions of experts and search through primary sources that tell the story of the topics and places they are researching. If your state or territory is not listed above, you can access a complete list of State Historical and Preservation Organizations to learn more about what is offered in your area.

Oral History —Interviewing people who own or have owned long running businesses, served in public office, run an organization, or lived in your area for a long time is one approach to learning how places have changed over time. Contacting someone to speak with about the topic, drafting questions related to the topic and project, conducting the interview, and transcribing that interview in order to use excerpts in the final product takes students through the inquiry process. Our Oral History Toolkit provides tips, resources, and other information pertinent to conducting oral history projects.

Historical Newspapers —The Chronicling America database provides access to millions of pages from digitized newspaper dating back to the 17th century. You can search by state and newspaper name to learn if and how what you are researching was covered by the press.

Mapping Place and Time

Using the information collected during the research process, students create a digital map or a hand drawn map of the area they are focusing on. Creating multiple maps, depending on the topic, to illustrate change over time will assist with organizing information and telling the story of the place and events they have chosen to focus on. Students should create a map that can then serve as a guide for the places they will need to go to capture photographs and plot out for the CLIO project they create.

Creating a Digital CLIO

Students may upload photographs taken during their research along with those they capture after they have completed their map(s) in the previous stage of the activity. Using the models provided at the CLIO website, students will upload their photos, curate the collection with information gathered from multiple sources during their research, and provide their own evaluation of why and how the places they live in and interact with have changed over time. Have they uncovered an event, learned about a heretofore forgotten person, or discovered some other information that may warrant public attention?

Digital Mapping

The emergence of digital mapping as an educational tool offers students an engaging, creative, and accessible way to learn about history at a local, state, or national level. Integrating these visual histories provides students with a historical and geographic context for narratives, events, and trends that are being discussed in class. Through Exploring Local History with Clio , students can learn how to investigate the history of their local community and contribute to the growing database of resources.

Below is a collection of NEH funded digital maps that can be used in the classroom:

Baltimore Traces

Baltimore Traces is an interdisciplinary project that uses media to explore the stories of Baltimore residents and neighborhoods. The project’s digital map features a collection of sites, events, and work being conducted by students at the University of Maryland Baltimore County.

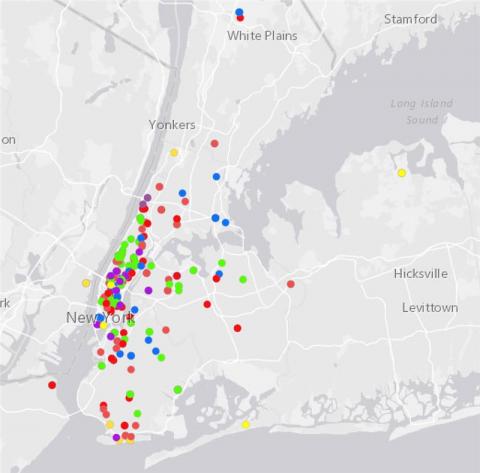

Deaf New York City Spaces

The Deaf New York City Spaces StoryMap created by students of Gallaudet University identifies historic and contemporary Deaf spaces in New York City. Integrated within the StoryMap are maps that categorize the sites by clubs, schools, places of worship, social spaces, and service facilities.

The Ethnic Layers of Detroit

The Ethnic Layers of Detroit digital humanities project created by Wayne State University uses technology and archival resources to teach students about the cultural, linguistic, and historical background of sites across Detroit. The places included in the digital map elucidate the untold history of the mid-west city.

Mapping the Gay Guides

The Mapping The Gay Guides project, led by students at California State University Fullerton, digitized the findings of Bob Damron, a gay man who documented places across the country that served as sites of refuge for other gay men during the 1950s and 60s. He later transformed his lists into a gay travel guide that doubled as survival guides to help gay and queer travelers locate safe places to sleep, eat, and socialize. The digital map allows users to choose a state and examine what sites operated in that area.

The Long Road to Freedom: Biddy Mason's Remarkable Journey

The Long Road to Freedom: Biddy Mason’s Remarkable Journey project documents the journey of Biddy Mason from enslavement in Georgia to becoming a landowner and community organizer in Los Angeles. Students can use the interactive map to learn about the “Second Middle Passage.” The project also includes a Google map that highlights significant historic and cultural sites associated with Los Angeles’s early African American history.

Below are some questions to encourage students to engage with the maps:

- How can digital maps be used to learn about historical events and trends?

- What does the map show you?

- How does this map build upon what you are studying in class?

- What does the map show you that other secondary sources cannot?

- What topics, events, issues, or themes relevant to your local community could you map?

One of the maps featured in the Deaf New York City Spaces project.

Mental Mapping

Mental mapping is another effective visual learning tool to help students examine their perceptions of their community. This activity entails asking students to create a mental image of their local community and translating those images into a drawing. Encourage them to think as broadly and creatively as possible. Through this process, students will recognize the differences between their objective knowledge and their subjective opinions about their local community.

Once students are finished, have them compare their drawings and discuss what the differences inform us about our perceptions of place. The Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation conducted a mental mapping project titled “Where We Are From” that can serve as a form of inspiration.

Below are questions for students to discuss after creating their mental maps:

- How did your mental map compare with other students?

- What memories did you use to help you create your map?

- Did mental mapping change how you see your community?

In this video , Erin Aoyama and Allison Mitchell discuss strategies for connecting the local past to the present and demonstrate the value of using place-based approaches to interpret history. They offer recommendations on locating and engaging primary sources and activities to support place-based learning. Both historians draw upon their own research to illustrate how studying local history can support students in making sense of their communities and contemporary challenges.

Historians Aoyama and Mitchell draw upon their research to offer perspectives on studying local history. Both Aoyama and Mitchell engage place-based approaches in their work. Erin Aoyama’s research examines Japanese incarceration camps in the South during World War II. She considers how Japanese American incarceration, particularly at the Rohwer and Jerome camps established by the federal government in Arkansas, fit into a larger story of the Jim Crow racial order. Allison Mitchell’s research considers the role of Black placemaking in the struggle for voting rights in the South. She looks at the independent Black town of Eatonville, Florida as a key site for understanding the connection between political and community autonomy for Black Southerners. You can learn more about Erin Aoyama’s research on the Rohwer and Jerome camps through our Heart Mountain Why Here? series. You can learn more about Allison’s work and Eatonville through our Zora Neale Hurston and Eatonville Why Here? series.

Questions for teachers to consider when teaching place and memory

- How can you explore the connection between history and space in your local community?

- What kind of primary sources can we use to support inquiry in local history? How might using poetry, music, and other art as primary sources enrich place-based learning?

- Are there people or organizations locally who could offer oral histories or other perspectives on this history?

- How might this local history shift how students interpret or respond to contemporary conditions or issues in the community?

- What skills can this historical investigation offer students for navigating their present local community?

- How might studying local case studies shift students’ perspectives on topics or themes in national American history?

- What kind of technical tools and skills can students use or develop to investigate community histories?

The National Endowment for the Humanities continues to support high-quality projects and programs in the humanities and makes the humanities available to all Americans. So whether you are traveling for work or pleasure, visiting an area museum, or spending time with friends and family at home, you will find that the NEH is just around the corner (or already in your hands). NEH funded affiliates and collaborators on state and local history and culture projects, and how they connect to the national story of the United States, can be found through the resources below:

NEH Federal/State Partnership Office —The Office of Federal/State Partnership is the liaison between the National Endowment for the Humanities and the nonprofit network of 55 state and jurisdictional humanities councils.

NEH Division of Education Programs Grant for Landmarks of American Culture and History —This program supports a series of one-week workshops for K-12 educators across the nation that enhance and strengthen humanities teaching at the K-12 level.

NEH Division of Public Programs —The Division of Public Programs supports a wide range of public humanities programming that reaches large and diverse public audiences and make use of a variety of formats—interpretation at historic sites, television and radio productions, museum exhibitions, podcasts, short videos, digital games, websites, mobile apps, and other digital media.

NEH Division of Preservation and Access —A substantial portion of the nation’s cultural heritage and intellectual legacy is held in libraries, archives, and museums. All of the Division of Preservation and Access’s programs focus on ensuring the long-term and wide availability of primary resources in the humanities.

State Humanities Councils —The State Humanities Councils are funded in part by the federal government through NEH's Federal/State Partnership Office . They also receive funding from private donations, foundations, corporations, and, in some cases, state government.

National Humanities Alliance —The National Humanities Alliance is on top of all NEH related events, exhibits, and projects taking place around the country.

NEH on the Road —Is there a NEH sponsored exhibit near you? Would you like there to be? NEH on the Road provides ready-to-go exhibits for organizations and classrooms. Learn if one is currently available near you and how to set one up on your own.

Related on EDSITEment

Landmarks of american history and culture, exploring local history with clio, doing oral history with vietnam war veterans, chronicling america: history's first draft, american utopia: the architecture and history of the suburb, mapping the past, backstory: saving american history, a landmark lesson: the united states capitol building.

Exploring Local History with children – A homework guide for children studying local history

- 14th December 2018

| Over the years wehave been asked, by parents, about what we hold that can be of assistance to children conducting local history research as part of a school project. This resource is created in response to these enquiries and is adapted from one of our publications, created for teachers, to help children answer the question ‘What was it like to live here in the past?’ The aim of this this resource is not only to give the children an understanding of their local area and appreciation of its history and diversity, but also to develop the children’s research skills.

There are a number of published histories of the County but for many places the story of its past is yet to be written. Where no written history exists the children will find themselves constructing a picture of the past by using an assortment of primary sources.

This leaflet suggests resources to be used and provides a series of structured questions that can help the children fully explore the available evidence.

It is available to download for free from our website The photograph shows the members of a Worcester family whose interest in the history of their area was sparked by some objects that they unearthed in their garden. They came into The Hive to look at maps, planning applications and censuses to construct a picture of what the area developed and who lived in their home in the past.

This is an account that the children wrote of their visit to The Hive. |

Share this Post

Post a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Our accreditations

Related news

- 26th May 2024

Redditch New Town Archives: Heritage and the ‘Old Town’

This is the fourth and final blog of this Redditch New Town series. In this blog we explore the work the Corporation did to spread the word of the town’s history and the work of one special charity that raised money to enhance and preserve historical sites and recreational areas for all to enjoy. Redditch...

- 22nd May 2024

The New Burdens project

Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service (WAAS) is embarking on an exciting 2 year project to catalogue a range of public records as a result of New Burdens funding. The funding made available from central government compensates local authorities for increased activities that places of deposit such as WAAS may experience due to changes in legislation with the Public Records Act.

- 18th May 2024

Body on the Bromyard Line 5 – Can you help?

This is the fifth and last in a series of five posts exploring the story behind the human skeleton found buried within an embankment of the Worcester, Bromyard and Leominster railway line in 2021, close to Riverlands Farm in Leigh, to the west of Worcester. Over this mini-series we explore the discovery, and what we...

History Resource Cupboard – lessons and resources for schools

Teaching Issues

Teaching local history.

I know we would all love to teach local history. After all, there are fewer ways to make history resonate with your classes than teaching them about the interesting things that happened literally under their feet.

Kids who have looked at some really good local history about their own city, town or village will forever view that particular spot you focused on in a completely different light – a historical one.

But one of the major barriers to stopping us teach local history is access to what cab drivers have: the knowledge (local of course). Even if we have this, the other big sticking point is getting hold of decent resources quickly and easily. Who really has time to go to the local library or records office and spend hours searching, in hope that we find a gem? Never me, that is for sure.

You think it impossible, yet there are small teams of experts out there just willing you to ask them for help. It is quite incredible. Don’t believe me? Well I know because through a chance phone call I have a whole digital archive at my fingertips. And, I’ll bet, if you ask the right questions, you too could find the same thing. In fact carrying on reading and I will show you how to access fab local resources.

The rest of this content is for members only. Please Register or login.

You are here: home » teaching issues » wider teaching issues » teaching local history, more articles.

Two different approaches to collaborative planning in history

February 5, 2019

Teaching Historical Interpretations

September 22, 2015

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Receive details of our latest courses, new lesson downloads, exclusive discounts and the latest articles with ideas to help you enliven your classroom teaching.

THANK YOU - YOU HAVE SUCCESSFULLY SUBSCRIBED

Recommend this post.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

In Your Neighborhood

Tools for bringing local history online.

By Carrie Smith | November 1, 2021

Want to preserve, share, and contextualize local history in your community? If so, technology can help move these activities beyond the special collections section. Online platforms created specifically for local history are allowing libraries to share information in more interactive ways, in turn reaching new audiences, educating patrons, and adding to the historical record. Here we talk with three library workers who are creating walking tours, collecting and archiving oral histories, and connecting with their communities.

User: Jennifer Sanders-Tutt, local history librarian at St. Joseph (Mo.) Public Library

What is Clio? Clio is a local history platform made by historians that allows you to create entries for points of interest and link them together into tours. It’s web- and app-based, and anyone can open a free account.

How do you use it? We do a Local History Week every year, and I wanted a passive program that people could do outside if they wanted, so we devised a couple of different tours. You can create either an individual entry or a walking tour; the platform has guides on what to include. You can also add your own images, and we included some historic images from our downtown library’s collection.

What are the main benefits? Clio allows us to get local history out there in another medium. The app will bring up any tours around you (if you allow it to use your location), so users can just jump in. The tours are immersive—you’re looking at things that maybe you walked by a hundred times, but now you’re seeing them in a different light. Plus, one of my favorite aspects of Clio is that you can upload and link your sources. As a researcher and historian, I want to make sure people know they are getting accurate information.

What would you like to see improved or changed? There are sometimes issues with Google Maps integration, and it’ll pop you in and out of Google Maps and the Clio app. Overall, though, it’s a fantastic platform.

User: Troy Reeves, head of the oral history program at University of Wisconsin–Madison

What is TheirStory? It’s a remote interviewing platform, like Zoom for oral historians. It allows for face-to-face interaction, which is nice when you’re doing oral histories.

How do you use it? We use TheirStory for interviews done by our student historian in residence and for our Women Inspire and COVID- 19 oral history projects. We’re primarily an audio archive, and it allows us to download interview audio as a WAV file, as opposed to other platforms where you’re downloading audio as an MP3 or other type of compressed audio file. It also allows us to export transcripts as Word documents that sync up with the tool that we use to put interviews online, the Oral History Metadata Synchronizer.

What are the main benefits? Not only can you do oral history interviews remotely and export high-quality audio, but you also have a transcription tool that gives a quality first draft. The interface is easy, too: You push a button to start a session and it gives you a URL that you can share. There’s also a calling feature, so interviewees can call in, and you can host multiple people.

What would you like to see improved or changed? TheirStory’s team has been great to work with. They’ve been quick to figure out any sort of transcript glitch, and they’ve been very receptive to what few other issues we’ve had. They recently added an indexing tool, a feature we had wanted, and my students say it works well.

User: Kari Karp, teen services librarian at West Hartford (Conn.) Public Library

What is Historypin? Historypin is a free website and mapping tool that allows individuals and organizations to archive historical photographs, videos, and audio recordings. Users can create collections reflecting different themes. Some of our library’s most popular collections center on neighborhoods, local legends and heroes, and natural disasters like blizzards and floods.

How do you use Historypin in your library? Our local-history department started a “Places and Faces” collection nine years ago, and so far there are more than 500 pins. We invite residents to bring us their old photos, 35mm slides, and negatives so that we can scan and add them to our Historypin channel. From 2014 to 2017, we also used Historypin as part of an Institute of Museum and Library Services grant called Memories of Migration. For that project, I helped train high school students on how to conduct oral histories, and we put photographs and links to the interviews on our channel.

What are the main benefits? Historypin is a user-friendly tool that makes history more accessible. Many people have photos in boxes and albums at home that would be of local interest. It also fosters patron engagement and community connections by letting patrons share personal memories with neighbors.

What would you like to see improved or changed? Historypin is very visual, with maps and large images that take up most of the screen. This is ideal for browsing the site, but I would like to see more organization, like collections and subcollections, and maybe a list of tags to make it clearer which types of photographs are available in a channel.

CARRIE SMITH is editorial and advertising associate for American Libraries.

Tagged Under

- digital collections

RELATED ARTICLES:

Bookend: History Rolls On

What To Collect?

Building a local history reference collection at your library.

Get the Reddit app

History assignment ideas.

I’m a first year world history teacher and I was hoping I could get some ideas for homework assignments for my freshmen and sophomores. Any ideas are welcome!

- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

Grade 4 - Term 1: Local History

People learn and are influenced by the places and the people around them. In a country like South Africa, which has a rich diverse heritage, many people have learned from stories told to them by their proud elders and community members. These stories carry information and ideas about life and living as well as shared customs, traditions and memories passed from parents to children. In this lesson we will explore historical places and the natural environment that is part of our country’s heritage. This will assist learners to find out about the past and how to apply this knowledge to their local history. The lesson ends with a case study of Pretoria and includes information about how to create a museum display. Members of our communities can be asked about the past and we will learn about their stories by asking them questions.

Learners will collect information about their local areas by collecting information from various sources, namely through the use of pictures, research and writings, stories, interviews and objects. The local area examined as part of this section of the curriculum will differ from area to area and even from school to school.

Of importance is that learners will cultivate the skill of finding information using various sources. SAHO has used Pretoria as an example of a local history project, it being the capital of South Africa. The aim of this section is to show learners how to access various resources that give information about the past and present.

Further reading - Oral history as a methodology presentation by Mrs FL Mrwebi at the finals of the Nkosi Albert Luthuli Oral History Competition - Oral history project presented by Ingred Persad at the finals of the Nkosi Albert Luthuli Oral History Competition

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

Resources you can trust

20 teaching ideas for history homework

A collection of tried and tested strategies to build interest and variety into history homework activities. Ideas include menus, electronic essays and writing wikis.

All reviews

Have you used this resource?

Lesley Hall

Resources you might like

- International

- Education Jobs

- Schools directory

- Resources Education Jobs Schools directory News Search

History homework projects - Years 7 to 9

Subject: History

Age range: 11-14

Resource type: Other

Last updated

22 February 2018

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

Creative Commons "Sharealike"

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

TES Resource Team

We are pleased to let you know that your resource History homework projects - Years 7 to 9, has been hand-picked by the Tes resources content team to be featured in https://www.tes.com/teaching-resources/blog/thought-provoking-historical-projects in June 2024 on https://www.tes.com/teaching-resources/blog. Congratulations on your resource being chosen and thank you for your ongoing contributions to the Tes Resources marketplace.

Empty reply does not make any sense for the end user

Thanks for sharing

Denise12_34

Really great help :D

Very good resource

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

- Subscribe to our E-Newsletter

- Society Directory

- Member Sign in

- Individual Membership

- Society Membership

- Renew Your Membership

- The Local Historian

- Local History News

- Online Reviews

- BALH E-Newsletters

- 200 Magazine

- Teacher Fellowship in Local History

- Education Partner: Pharos Tutors

- The British Coronation Project 2023

- Educational Resources

- Classroom Exercises

- Educational Organisations

- Local History and the First World War

- Local Society Insurance

- Local History Societies

- BALH Annual Awards

- Local History Photographer of the Year

- BALH Presentation Material

- Other Presentation Material

- Ten-Minute Talks

- Retention schedule for BALH archives

- AGM Recordings

- National Organisations

- Useful Links

- BALH Structure

- BALH Trustees

- BALH Officers and Teams

- Constitution

- Code of Conduct

- Policies and Guidance

Starting a Local History Group

- Crowdsourcing as a method of fundraising

- Delivering A Programme of Speakers

Resources Local History Societies Starting a Local History Group

A: Objective

Why do you want a local history group?

There are lots of possible answers, most of which are valid. However it is a good idea to have an answer to this question, even if with time it changes.

You may want to study the whole history of your community.

For example You live in a village or a part of a town and you want to know what happened there in the past. You may belong to a minority group and want to know how your particular ancestors came to the area where you now live.

You may want to examine one particular aspect or time period relating to your community.

For example You might belong to a church or club and want to know about its past. Perhaps there was once an important factory in the area, now gone, but you want to know more about it and the people who worked there. There may be some very interesting buildings in your area and you want to know who built them and why.

Or You may have come across an interesting set of documents and want to study them.

These are just a few examples of what leads you to want a local history society. If you know roughly what you want to do, it will help you find others who are similarly interested.

By the way, have you checked that no other society is covering the ground that you are interested in?

B: Establishing and maintaining the society

1. Committee

To be effective, you need others to join with you to help run the society. If you can get even two or three others at the start, it will mean that the load is shared and will make the new Society feel like a club that others can join. Subsequently, you may get more who will join the committee and you may lose some of your first helpers.

You will need people, who may or may not have formal titles, to chair meetings, arrange publicity, look after funds, book halls for meetings, keep membership or contact records and do anything else the Society wants done.

The Committee should meet from time to time to run the Society, but meetings can be as formal or informal as suits the members. It is sensible to keep records of what is decided and who is going to do what. If you have a very small group, you may not have a separate committee, but the jobs still need doing and you don’t want to take up all your meetings with business, no matter how informal.

2. First meeting

You want to draw in other people so you will need to hold a meeting. You will need to advertise it and invite people along. (See below for suggestions). Again the purpose of your society will influence whether you put out public notices widely, or whether you target only those who you know are likely to be interested in your objectives.

Either way, you will need to tell people about the plans for the new Society. To encourage them, have a speaker (which can be yourself) who can tell them something about the subjects you are going to study and perhaps give some idea of where your researches will take you next.

You will need to decide whether to hire a room somewhere or meet in a private house. A private house is the cheaper option, but may deter the mildly curious. If you hire a hall, it will have to be paid for, unless you have influence with its owners. Decide also whether you will serve tea, coffee, biscuits or whatever and organise someone to do it. People will pay a small amount for refreshments which covers their costs.

At your first meeting, you may want to put on a small exhibition of pictures relating to your theme. Pictures are best. If you use text, don’t have too much and use a large font that is easy to read. Remember that most local historians are 50+ and some have poor eyesight.

Although you may get one or two members who will join in active research, welcome the rest. Their subscriptions will keep the Society going and they will make up the numbers at public meetings. Above all, never complain to those who have turned up that they are too few, too indolent or not young enough, however much you may feel it. You want to show enthusiasm and be pleased that you are achieving more than was happening before you made your efforts.

At the end of the meeting, you may have one or two more people who will join the committee so be prepared to arrange a date and place. There is also a case for fixing a date and subject for your second public meeting so that you establish a momentum.

3. Publicity

To get an audience, you need to tell people about your events.

To advertise a meeting make sure you include where, when – date and time, title, name of speaker if there is one, any cost to the audience, refreshments if they will be served, and who to contact for further information.

You have to think about publicity for the first meeting and continuing publicity. This is where balancing cost against coverage is difficult. The methods you need to consider are word of mouth, local paper, local radio, leaflets and posters. Later you will need to contact your members regularly to keep them up to date.

You may find that you have someone who will look after the publicity – writing news items and designing leaflets or posters, or you may end up sharing the work.

Personal contact

If you have an enthusiastic membership, they will bring friends along and this is always a good way to recruit new members. Make sure they are welcomed and not made to feel that they are on the edge of a clique.

If you can write stories about the history you are doing, local papers will often print them. They will often allow you to slip in a mention of when your next meeting will be. Write up something you know about the history your group is studying. You may find that the professional journalists will re-write it: if they do see how their style differs from yours and adapt accordingly. The formation of your group is a news story in its own right, so make sure that you get that to the editor. You might want to invite people to the first meeting by means of a Letter to the Editor. If you can add a relevant photo that adds to your publicity – but don’t use one in copyright. Also find out what format the paper wants. They can usually handle jpg or tif format, but it might be courteous to check, and it gives you an excuse to tell reporter or editor what you are doing. Incidentally think of both local papers that people buy and the free ones that come through your door.

You can place advertisements in local papers, but this can be expensive.

Radio or Television

It is usually harder to get publicity on local radio, although your station may have a diary feature in which they will give details of forthcoming events. You need to find out how much notice they need and make sure you include all the necessary details.

Even local TV will only be interested when you have a very special story, and not always then.

If your proposed society covers a smallish potential number of people, it might be worth preparing a leaflet and giving it out, for example to a church congregation or through letter boxes of a small community. Make sure it includes all the essential information listed above. You will want it to look attractive, but don’t get carried away by making it too busy. People want to see messages quickly and clearly.

Although it is tempting to have big posters, they are almost impossible to get displayed without considerable cost. The idea of hanging a banner across the High Street is tempting but rarely justified for a local history society. Most shops or other places with notice boards will take A4 size, but few will take bigger ones, so don’t waste your money. Again design it the best you can, but don’t worry if it does not look professional. Just make sure the essential information can be read easily.

4. Membership

You will need to decide whether you will have a membership. Most societies have members but some simply call meetings and get in touch through local parish newsletters. The latter works better in the country but mostly the arrangement tends to collapse after a while.

If you have members, you have a group who are likely to attend your events, some of whom will help run the events, and all will pay subscriptions. You will need to keep a list of the members with their addresses. Many societies contact their members by email primarily, but don’t overlook those who do not use email. You will need one of your committee to take on the job of membership records.

5. Keeping in touch – newsletter, calendar card, website, posters etc.

You will want to keep in touch with your members. This may consist of emails, but as you get to know more about your subject, you may want to produce a newsletter so that you can share information. Different societies adopt different strategies, but what you will want to tell your members includes details of forthcoming events, chatty short items of interest, and longer articles.

Some societies produce a newsletter that incorporates all three into one publication. Others produce a separate programme card and then publish articles separately. You may even decide to publish short and long articles separately.

However this is something that you can allow to evolve, but almost from the start you will want to give members details of forthcoming events, and snippets of interest will encourage them to read on. Some people like to encourage everyone to receive newsletters by email. This is much cheaper, but many newsletters received in this format are not read very conscientiously and some organisations wrap them up in such a way that they are difficult for the non-computer literate to open and read, so be careful. If you print your communications, make sure that copies go to the local paper, the local library, the British Association for Local History and possibly the County Record Office.

6. Naming your society

Your new society will need a name. Have some ideas available for the inaugural meeting, but don’t spend too much time on the task. It is probably better to have an informative name, such as X Local History Society although it can be tempting to adopt a more obscure name. Eventually the community will get used to an obscure name, but it can act as a barrier to membership because people don’t know what you are about.

7. Constitution

Be realistic about your constitution. You need a set of rules about how you want to run your society. You don’t need an elaborate set of rules that will tie you in knots at every turn. Think out how you want your society to work and write a set of guidance notes to that end.

For example you may have someone wanting to put in clauses about the length of time officers can hold office, or xxx stating that there must be a minimum number of people present at meetings. If you can achieve these objectives, all well and good, but if you don’t you will be in trouble. Either it will be necessary to ignore your constitution as you will not be able to set it aside because the minimum number of people needed to make changes are not present, or you will not be able to hold meetings. Similarly if you have a good treasurer you don’t want to set him or her aside because three years have passed.

8. Join BALH for help, insurance and ideas

Most local history societies are independent bodies. They may talk to neighbouring societies, but they are autonomous. That does not mean that you cannot get ideas from other people.

If you join the British Association for Local History, you can take advantage of their insurance arrangements. You will also get copies of The Local Historian , Local History News and the E-newsletter which are full of news and ideas of relevance for anyone trying to run a local history society.