Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 27 February 2024

Adolescent mental health and academic performance: determining evidence-based associations and informing approaches to support in educational settings

- Xzania Lee 1 ,

- Anya Griffin 1 , 2 ,

- Maya I. Ragavan 3 &

- Mona Patel 1 , 2

Pediatric Research volume 95 , pages 1395–1397 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1686 Accesses

Metrics details

In 2021, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the Children’s Hospital Association (CHA) declared a “National State of Emergency in Children’s Mental Health.” 1 The statement identified how the pandemic exacerbated the already worsening mental health problem among US youth due to the compounding challenges faced by youth and acknowledged the significant impact of this mental health crisis on youth. This declaration made a call for schools, policymakers, and advocates for children and adolescents to prioritize and focus on pediatric mental health.

Adolescent mental health and academic performance are intricately linked aspects of development, each influencing and being influenced by the other. The recognition of this bidirectional association has sparked considerable interest within the research community, prompting an investigation into the nuanced dynamics between mental health and educational outcomes during the formative adolescent years. Numerous studies have explored the connection and influence between mental health and academic performance, and further acknowledge that the multifaceted interconnectedness of mental health and academic performance require a holistic view. 2 , 3 , 4 Researchers have identified that higher academic aspirations are associated with better mental health outcomes and that socioemotional well-being is needed for academic thriving. 5 , 6 Furthermore, Yu and associates described how interpersonal relationships are positively correlated with academic performance, especially student-peer relationships, which had more influence than the parent-student or teacher-student relationship on academic achievement. 7 , 8 Finally, impacts of social determinants of health have been shown to exert profound influences on both mental health and academic outcomes further emphasizing the need to consider the broader ecological context in which adolescents develop and the importance of considering a socioecological model, suggesting that factors such as family, school, and community environments play pivotal roles in shaping both mental health and academic outcomes. 6 , 9

In this article by Monzonis-Carda and associates, the authors explore the bidirectional longitudinal association between the dual-factor model of mental health and academic performance in adolescents. The dual-factor model of mental health, in contrast to traditional models of mental health which focus on psychopathological symptoms, integrates mental health wellbeing and psychopathology into a mental health continuum. 10 The authors hypothesize that a bidirectional association between academic performance and adolescent mental health would be present in their sample of 266 secondary school students from Spain. They assessed mental health through the Spanish language Behavior Assessment System for Children and Adolescents (BASC-S3) and examined grade point average, and academic performance based on the Test of Educational Abilities. They then employed a cross-lagged modeling approach to analyze the bidirectional association over 2 years. The key findings suggested that higher academic performance at baseline was associated with better mental health over time, but better mental health was not associated with academic performance. Therefore, the association was not bidirectional as expected. Based on these findings, the authors posit academic performance may be a predictor of adolescents’ mental health status; and conversely, mental health may not be a predictor of adolescents’ academic performance. They offered school-based recommendations for the promotion of good mental health practices for students with low academic performance and supported future policy and health and educational professionals to promote adolescent mental health wellbeing. Overall, the article underscores the importance of considering academic performance as a target for interventions to promote adolescents’ mental health. It suggests that focusing on reducing school pressure and establishing personalized academic goals could contribute to better psychological well-being.

While the article provides some important insights into the association between mental health and academic performance in adolescents, some limitations were noted. While there is some limited adjustment for socioeconomic status, the article lacks a comprehensive exploration of social determinants of health and impacts of adverse childhood events (ACES), such as cultural background, and other important social and familial dynamics. These factors play a pivotal role in shaping an adolescent’s mental health and academic performance and may result in an oversimplified understanding of the complex interplay between mental health and academic outcomes. The study further focuses on academic grades and “abilities” as indicators of academic performance. Academic success is multifaceted and includes factors like motivation, engagement, and teacher-student relationships, and a more nuanced exploration of these components could provide a richer understanding of the relationship between mental health and academic outcomes. The study authors reviewed limitations that require further investigation including the use of BASC-S3 as the primary self-reported measure of adolescent mental health. Depending on individual developmental level of insight and situational context, adolescents are often unreliable and inaccurate reporters of their functioning, and adolescents in clinical populations tend to overreport symptoms and provide inaccurate information regarding their functioning on the BASC-S3. 11 , 12 Incorporating objective measures or multi-method assessments and the inclusion of multi-rater methods (i.e., teachers, caregivers, etc.) may provide a more detailed picture of the student’s true socioemotional functioning through the provision of differing perspectives of each student’s functioning. 13 The study’s authors also acknowledge a relatively small sample size, homogeneity of the study population, and short study length to determine longitudinal outcomes may further limit generalizability to other populations. Lack of testing for sex assigned at birth and self-identified gender effects, and not integrating broader social determinant impact upon adolescent mental health may result in misguided or ineffective approaches to promoting mental health in adolescents. Further, previous research and psychological assessment literature have indicated the significant impact of social determinants of health and ACES on youth academic achievement and behavioral health outcomes. Students with elevated social risk, including ACES, are often at increased risk for mental health and academic achievement deterioration. 14 This supports the need for school leaders and policymakers to continue to focus efforts on maximizing the recognition of these factors for youth and promote the implementation of programs to address roots of social risk and integration of socioemotional mental health supports in academic institutions. 15 Due to the interconnectedness of mental wellness and academic success, addressing aspects of mental health functioning within the school setting will equip students with the essential skills to navigate challenges, manage stress, and build resilience. By bolstering emotional, behavioral, and social skills, students are primed to engage in learning, establish positive relationships with peers and teachers, and cope with the pressures of academic stress and daily life hassles. 16 A structured educational tier one (i.e., general education curriculum) mental health intervention will assist students with stress reduction, and behavior management, improve executive functioning skills, and establish a scholastic environment conducive to effective knowledge consumption and academic performance. 17 Incorporating evidence-based practices to support student emotional wellness holistically nurtures the development of students and provides a foundation for lifelong well-being and academic excellence. While this article contributes to the understanding of the association between mental health and academic performance, it also highlights the need for future exploration of factors that influence the causality between adolescent mental health and academic performance and further informs the recommendation to have mental health interventions and social-emotional learning curriculums in educational settings.

The 2021 joint declaration of the “National State of Emergency in Children’s Mental Health” catalyzed federal, state, and local awareness of evolving needs in pediatric mental health in the United States of America. While there has been increasing bipartisan support and focus for mental health funding at all levels of government, appropriate allocation of such funding to support identifying factors that impact pediatric mental health and using a data-driven approach to effective programming is critical. An example of more recent federally supported funding programs for child mental health includes the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) funded Pediatric Mental Health Care Access (PMHCA) program, which has seen increased funding from 2018 through 2022, with an additional 80 million dollars added by the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act. ( https://mchb.hrsa.gov/programs-impact/programs/pediatric-mental-health-care-access ) Currently, under-resourced and under-reimbursed health systems fraught with post-pandemic short staffing and pre-pandemic existing behavioral health access challenges pose continued roadblocks to access. Pediatric policy recommendations to aid with improving meaningful pediatric mental health access include:

Increased funding and support for access to meaningful mental health resources in the community and schools

Integrated behavioral health delivery models within primary care and specialty care will be critical in enhancing access to care.

Increase the behavioral health workforce, training programs for primary care pediatricians and pediatric psychologists are needed, as the number of child psychiatrists and pediatric psychologists is currently not sufficient to meet demand.

Innovative and integrative team-based models including non-traditional licensed and non-licensed behavioral health support teams, including community health work may allow further access and a more impactful peer-to-peer support structure.

Behavioral health reimbursement shifts may ultimately be required to build infrastructure to address the current critical socio-emotional needs of our youth. Ultimately, research informing a more comprehensive perspective, including health-related social needs and ACES will be essential for advancing the field with evidence-based mental health interventions for youth.

American Academy of Pediatrics. AAP-AACAP-CHA declaration of a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health [press release] https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/child-and-adolescent-healthy-mental-development/aap-aacap-cha-declaration-of-a-national-emergency-in-child-and-adolescent-mental-health/ .

Pagerols, M. et al. The impact of psychopathology on academic performance in school-age children and adolescents. Sci. Rep. 12 , 4291 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sörberg Wallin, A. et al. Academic performance, externalizing disorders and depression: 26,000 adolescents followed into adulthood. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 54 , 977–986 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Wang, M. T. & Eccles, J. S. Adolescent behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement trajectories in school and their differential relations to educational success. J. Res. Adolesc. 22 , 31–39 (2012).

Article Google Scholar

Almroth, M. C., László, K. D., Kosidou, K. & Galanti, M. R. Association between adolescents’ academic aspirations and expectations and mental health: a one-year follow-up study. Eur. J. Public Health 28 , 504–509 (2018).

Duncan, M. J., Patte, K. A. & Leatherdale, S. T. Mental health associations with academic performance and education behaviors in Canadian secondary school students. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 36 , 335–357 (2021).

Suldo, S. M., Shaunessy-Dedrick, E., Ferron, J. & Dedrick, R. F. Predictors of success among high school students in advanced placement and international baccalaureate programs. Gifted Child Q. 62 , 350–373 (2018).

Yu, X. et al. Academic achievement is more closely associated with student-peer relationships than with student-parent relationships or student-teacher relationships. Front. Psychol. 14 , 1012701 (2023).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Adler, N. E. & Stewart, J. Health disparities across the lifespan: meaning, methods, and mechanisms. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1186 , 5–23 (2010).

Zhang, Q., Lu, J. & Quan, P. Application of the dual-factor model of mental health among Chinese new generation of migrant workers. BMC Psychol. 9 , 188 (2021).

Sonne, J. L. et al. Interpretation problems with the BASC-3 SRP-A F Index for patients with depressive disorders: An initial analysis and proposal for future research. Psychol. Assess. 32 , 896–901 (2020).

Fan, X. et al. An exploratory study about inaccuracy and invalidity in adolescent self-report surveys. Field Methods 18 , 223–244 (2006).

De Los Reyes, A. et al. The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychol. Bull. 141 , 858–900 (2015).

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available at: www.cdc.gov/yrbs (2021).

Greenberg, M. T., Domitrovich, C. E., Weissberg, R. P. & Durlak, J. A. Social and emotional learning as a public health approach to education. Future Child. 27 , 13–32, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44219019 (2017).

Herrenkohl, T. I., Jones, T. M., Lea, C. H. III & Malorni, A. Leading with data: Using an impact-driven research consortium model for the advancement of social emotional learning in schools. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 90 , 283–287 (2020).

Belfield, C. et al. The economic value of social and emotional learning. J. Benefit-Cost. Anal. 6 , 508–544 (2015).

Download references

Open access funding provided by SCELC, Statewide California Electronic Library Consortium.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Xzania Lee, Anya Griffin & Mona Patel

Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Anya Griffin & Mona Patel

Division of General Academic Pediatrics, University of Pittsburgh and UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Maya I. Ragavan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mona Patel .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lee, X., Griffin, A., Ragavan, M.I. et al. Adolescent mental health and academic performance: determining evidence-based associations and informing approaches to support in educational settings. Pediatr Res 95 , 1395–1397 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-024-03098-3

Download citation

Received : 22 January 2024

Accepted : 28 January 2024

Published : 27 February 2024

Issue Date : May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-024-03098-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Health and Academic Achievement - New Findings

Relation between Student Mental Health and Academic Achievement Revisited: A Meta-Analysis

Submitted: 15 June 2020 Reviewed: 24 December 2020 Published: 20 January 2021

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.95766

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Health and Academic Achievement - New Findings

Edited by Blandina Bernal-Morales

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

2,685 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

Overall attention for this chapters

In the present research, the relationship between mental health and academic achievement in adolescents was investigated. The research adopted meta-analysis model to investigate the relationship between these two phenomena. In the meta-analysis, 13 independent studies were included, and their data were combined to display effect sizes. According to the result of the research, it was indicated that there was a positive relationship between mental health and academic achievement. Also, it was revealed that there was no significant relationship within sub-group variation in the relationship between mental health and academic achievement in terms of year of publication, publication type, community, and sample size, but not the setting.

- mental health

- academic achievement

- mental health in adolescents

- meta-analysis

Author Information

Gokhan bas *.

- Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Faculty of Education, Nigde Omer Halisdemir University, 51100, Merkez, Nigde, Turkey

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction

In recent years, mental health of adolescents has taken considerable attention worldwide, because of a dramatic upward trend in suicide [ 1 ]. More than twenty percent of adolescents in the U.S. have a mental health disorder [ 2 ], and one in five of them are affected by a mental health problem [ 3 ], which is estimated to account for a larger burden of disease than any other class of health conditions [ 4 ].

The mental health field has traditionally focused on psychological ill-health, such as symptoms of anxiety or depression [ 5 ]. The most common mental health disorders among adolescents include obsessive–compulsive disorder, attention deficit hyperactive disorder, bi-polar disorder, impulse disorders, and oppositional defiance disorder [ 6 ]. Often, adolescents experience mental health problems, with fewer than half of them [ 7 ], in other words nearly one third of them need receiving treatment [ 8 ]. The situation is much more severe in adolescents living in racial and ethnic communities, who are more likely to have mental health problems [ 9 ]. Moreover, evidence suggests that adolescents coming from such communities are less likely to use mental health services, compared adolescents living in non-racial and ethnic communities [ 10 ]. Thus, when adolescents struggle with mental health problems, they often have attendance problems, difficulty completing assignments, increased conflicts with adults and peers [ 11 ]. Also, mental health problems adolescents have negatively impact their academic productivity and interpersonal relationships [ 12 ], and as a result of such problems, one million of adolescents – which is deemed to be very high – drop out of school annually in the U.S., for example [ 13 ].

Mental health issues among adolescents not only cause such problems, but they also negatively influence schooling [ 14 ]. Adolescents with mental health problems are at risk for schooling [ 15 ], and they may have increased difficulties primarily with academic achievement in school [ 16 ]. Frequent feelings of mental health problems exhibit school difficulties, including poor academic achievement [ 17 ]. Adolescents displaying strong mental health are likely to have better academic achievement, compared to adolescents displaying weak mental health [ 18 ]. Adolescents showing strong mental health have good social skills with both adults and peers [ 19 ], and their enhanced social and emotional behaviors have a strong impact on academic achievement [ 20 ]. Therefore, mental health problems in adolescents may have an important influence on academic achievement, which in turn have lifelong consequences for employment, income, and other outcomes [ 21 ]. Mental health issues may become problematic for adolescents in that they negatively influence academic achievement [ 22 ], which also might affect their future employment, health, and socioeconomic status [ 23 ].

Mental health problems of adolescents have an important influence on their schooling, particularly their academic achievement, which in turn may create important lifelong consequences. Due to a growing interest in mental health of adolescents in recent years, a meta-analysis seems timely, not only to demonstrate the association between mental health and academic achievement, but also to identify moderators that should be articulated in more depth in future research. Although there is a body of research on the relationship between mental health and academic achievement across the world, the literature is missing a meta-analysis of this relationship. To date, no meta-analytic research has examined the potential relationship between mental health and academic achievement, and the present research aims to fill this gap in the scope. Thus, the present research attempts to synthesize this association between mental health and academic achievement of adolescents. This meta-analysis aimed to answer the following research questions: (a) What is the relationship between mental health and academic achievement? (b) Does this relationship depend on year of publication? (c) Does this relationship depend on setting? (d) Does this relationship depend on community? (e) Does this relationship depend on sample size?

2. Methodology

The present research adopted meta-analysis model [ 24 ] to combine data from independent studies to draw a single conclusion with greater statistical power [ 25 ]. Meta-analysis is a model that reviews the research results and combines the data obtained from independent studies in statistical ways [ 26 ].

2.2 Data sources

Research examining the relationship between mental health and academic achievement was identified through a search of reference databases. To identify relevant empirical research on the relationship between mental health and academic achievement, a systematic literature review was conducted over a two-month time for the period 2000 to 2020, using such databases as Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), PsycINFO, Web of Science, EBSCOhost, Science Direct, Scopus, ProQuest®, and Google Scholar, with the following queries: [(“mental health” OR “mental health disorders”) AND (“mental health and academic achievement” OR “mental health disorders and academic achievement”], [“academic achievement” AND “academic success”], [(“adolescents mental disorders” OR “adolescents mental health”) AND (“adolescents mental health academic achievement” OR “adolescents mental health disorders academic success”)]. As a result of such review, a total of 52 studies including 34 journal articles and 18 postgraduate dissertations were reached. Thus, over 50 potential independent studies were generated for preliminary review as a result of the literature search.

2.3 Inclusion criteria

To be eligible for inclusion in the present meta-analysis, a study had to (a) investigate the relationship between mental health and academic achievement; (b) include studies conducted on adolescents; (c) have taken place from 2000 to the present; (d) be reported to be available in English; and (e) include sample size and correlation coefficients.

The first four criteria were used in an initial screening of the abstracts of the studies. If the study had no abstract available, the full publication was collected and examined thoroughly. For the last criterion, the full publication was examined, and it was checked whether it included sample size as well as correlation coefficients. For the studies with insufficient statistical information, the corresponding author was contacted and the relevant information for the missing data was requested. If the author did not respond or could not provide the missing data, the study was excluded from the meta-analysis. After checking each study in the light of the inclusion criteria, the author agreed that 13 studies met all the five criteria of the research (see Table 1 ).

| Author(s) | Publication type | Setting | Community | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White [ ] | Dissertation | U.S. | Urban | 780 |

| Sathiyaraj and Babu [ ] | Journal article | Non-U.S. (India) | Combination | 750 |

| Chung [ ] | Dissertation | Non-U.S. (Australia) | Urban | 261 |

| Eisenberg et al. [ ] | Journal article | U.S. | Urban | 2.798 |

| Gilavand and Shooriabi [ ] | Journal article | Non-U.S. (Iran) | Combination | 200 |

| Mundia [ ] | Journal article | Non-U.S. (Brunei) | Urban | 6 |

| Geetha [ ] | Dissertation | Non-U.S. (India) | Combination | 1.088 |

| Jenkins [ ] | Dissertation | U.S. | Urban | 331 |

| Singh [ ] | Journal article | Non-U.S. (India) | Urban | 200 |

| Sheykhjan et al. [ ] | Journal article | Non-U.S. (Iran) | Urban | 314 |

| Murphy et al. [ ] | Journal article | Non-U.S. (Chile) | Urban | 37.397 |

| Talawar and Das [ ] | Journal article | Non-U.S. (India) | Combination | 200 |

| Manchri et al. [ ] | Journal article | Non-U.S. (India) | Urban | 270 |

Studies included in the meta-analysis.

In order to investigate possible relationship between mental health and academic achievement, five moderators were extracted from the studies [ 40 ]. The first moderator concerned with the year of publication. The year of the publications were classified as 2009–2014 and 2015–2020, with a range of five years. The second moderator, publication type, referred to whether a study appeared as a journal article or a postgraduate dissertation. The third moderator, setting, referred to the country in which the research was conducted. Because the studies included in the meta-analysis were not from diverse settings – they were mainly coming from the U.S. and some Asian countries including India and Iran – the setting was classified as U.S. and non-U.S. The fourth moderator of the research, community, referred to the society people are living in. Because there was no study only conducted in rural settings, the community included urban and combination (urban, suburban, and rural). The last moderator, sample size, was classified as 1–500 and 501 above.

2.4 Computation of effect sizes

Standard procedures for conducting meta-analyses were followed [ 41 ], and the correlation between mental health and academic achievement were examined though effect sizes of independent studies. The effect size obtained in meta-analysis is a standard measure value used to determine the strength and direction of the relationship in the research [ 42 ]. In meta-analytic research, the variance depends strongly on correlation coefficient [ 43 ]. Pearson’s correlation coefficient ( r ) was calculated as effect size in the present research. For this reason, correlation coefficients were transformed into Fisher’s z coefficient for computing the effect sizes, and analyses were conducted through the transformed coefficients [ 44 ]. In meta-analysis research, when the variable consists of more than one factor and when more than one correlation value is given, there are two different approaches about which one of them can be used [ 45 ]. In this research, if the correlations were independent, all relevant correlations were included in the analysis and accepted as independent studies. When dependent correlations were given, the correlations were averaged.

There are two basic models in meta-analysis research; they are fixed effects and random effects models. When deciding which model to use, it is necessary to look at which model’s prerequisites are met by the features of the studies included in meta-analysis [ 46 ]. The fixed effect model is based on the assumption that when the data obtained are homogeneous, all the collected studies estimate exactly the same effect [ 47 ]. In this model, it is thought that the variance among the study results is caused by the data related to each other [ 48 ]. According to the fixed effect model, there is one effect size shared by the studies showing the same effect size for all studies [ 49 ]. In cases where the studies included in the meta-analysis show heterogeneous characteristics, it is more appropriate to use the random effect model [ 50 ]. This model is used in cases where the data obtained are not homogeneous [ 51 ]. As a result, while deciding which statistical model to use during meta-analysis, it should be tested whether the effect sizes show a homogeneous distribution.

In addition, the coefficient classification is taken into account in the interpretation of the effect sizes obtained as a result of meta-analysis [ 52 ]. In this research, Cohen’s [ 53 ] effect size classification was taken into account in the interpretation of effect sizes. According to this classification, values between .20 and .50 correspond to small effect size; values between .50 and .80 correspond to medium effect size; and values above .80 correspond to large effect size.

2.5 Publication bias

Publication bias refers to the possibility that all studies performed on a particular subject will not be representative of the reported studies [ 54 ]. Since the studies where statistically significant relationships are not determined or studies with low level relationships are not deemed worthy to be published, this affects the total effect size negatively and increases the average effect size bias [ 55 ]. So, effect sizes seem to be higher than what they normally are [ 56 ].

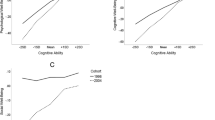

A number of calculations are used to reveal publication bias in meta-analysis research, including methods such as funnel plot, classical fail-safe N , Orwin’s fail-safe N , and Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill. The first method used to determine whether studies have publication bias is funnel plot [ 57 ]. The funnel plot, which displays the possibility of a publication bias in meta-analysis research [ 58 ], created for the relationships between mental health and academic achievement was shown in Figure 1 .

Funnel plot for the effect size of the relationship between mental health and academic achievement.

The funnel plot is expected to be significantly asymmetrical in publication bias. In cases where publication bias is not observed on the funnel plot, the effect sizes are symmetrically scattered around the vertical line. The line in the middle of the funnel plot shows the overall effect, and individual studies are expected to cluster around this line [ 59 ]. Studies which are asymmetrically scattered around the funnel plot refer to a possible publication bias in meta-analysis [ 60 ].

Also, classical fail-safe N was performed to reduce the average effect size to insignificant levels which is needed to increase the p -value for the meta-analysis to above .05 [ 61 ]. Classical fail-safe N showed that a total of 1699 studies with null results would be required to bring the overall effect size to trivial level at .01. Besides, Orwin’s fail-safe N was performed to decide the values of criterion for a trivial log odd’s ratio and mean log odds ratio in missing studies [ 62 ]. As a result of it, the number of missing null studies to bring the existing overall average effect sizes to trivial level at .01 was found to be .243.

Lastly, to assess the possibility of publication bias in the studies the trim and fill method, which is a nonparametric method of data augmentation used to estimate the number of studies absent from a meta-analysis due to the exclusion on one side of the funnel plot of the most extreme findings [ 63 ], was performed. With the help of this statistic, small studies at the far end on the positive side of the funnel plot are removed. The effect size is recalculated until the funnel plot is symmetrical [ 64 ]. When there is publication bias in the studies, the effect sizes are distributed asymmetrical on the funnel plot. In the research, the funnel plot provided evidence that there is no publication bias in the meta-analysis.

3.1 Overall results

A total of 13 studies were included in the meta-analysis with a sample size of 44.595 adolescents. As a result of the comparisons, the Q value indicated that the distribution of effect size of the studies was heterogeneous, Q (12) = 1002.815, p < .001, so that a random effects model was adopted in the meta-analysis (see Table 2 ).

| Model | CI | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Overall | 13 | .334 | .155 | [.187 | .467] | 98.803 | |||

| Year of publication 2009–2014 2015–2020 Publication type Journal article Dissertation | 4 9 9 4 | .256 .267 .256 .430 | .034 .010 .010 .047 | [.227 [.258 [.247 [.397 | .285] .276} .265] .462] | .004 .005 | 1 1 | .949 .942 | .00 .00 |

| Setting U.S. Non-U.S. | 3 10 | .107 .399 | .232 .206 | [−.126 [.212 | .329] .557] | 3.899 | 1 | .048 | .00 |

| Community Urban Combination Sample size 1 ≤ N ≤ 500 501 ≤ N | 9 4 8 5 | .250 .532 .408 .260 | .010 .051 .053 .010 | [.241 [.502 [.369 [.251 | .259] .562] .447] .268] | .990 .796 | 1 1 | .320 .360 | .00 .00 |

Results related to overall effect sizes of the studies.

Due to that they did not report in English, other studies coming from diverse settings across the world were not included.

Because there was no study only conducted in rural settings, the community included urban and combination (urban, suburban and rural).

Table 2 demonstrated the relationship between mental health and academic achievement of adolescents. The effect size of the relationship between mental health and academic achievement computed by random effects model was r = .334 (95% CI = .187–.467). The confidence interval showed that the true effect size was likely to fall in the .187 to .467, which indicated a low to medium effect [ 65 ]. The computed effect size revealed that there is a moderate level of positive correlation between mental health and academic achievement. The forest plot of the relationship between mental health and academic achievement was displayed in Figure 2 .

Forest plot of the relationship between mental health and academic achievement.

Moderator analyses were performed to examine whether the effect sizes were attributable to the basic research sub-groups. Results indicated that this was not the case, as neither sub-group, excluding the setting, moderated the research findings. There was no significant relationship within sub-group variation in the relationship between mental health and academic achievement in terms of year of publication Q b (1) = .004, p = ns , publication type Q b (1) = .005, p = ns , community Q b (1) = .990, p = ns , and sample size Q b (1) = .796, p = ns , but not the setting Q b (1) = 3.899, p = .048. In other words, no significant moderation effect was found, which means that the relationship between mental health and academic achievement does not depend on the basic sub-groups, excluding the setting.

4. Discussion

The present research quantitatively synthesized the results of 13 independent studies, conducted over the past two decades, which examined the relationship between mental health and academic achievement in adolescents. The results of the research confirmed that there is a significant positive relationship between mental health and academic achievement. These results are consistent with the recent research investigating the relationship between mental health and academic achievement [ 27 , 34 ]. Mental health problems may create many obstacles to adolescents, not just in their daily life routines, but also in their schooling academically. Mental health risks have long term and complex interactions with academic outcomes [ 27 ]. Mental health issues among adolescents not only cause pain and distress, but they also influence negatively their potential for success in school [ 14 ]. More and more adolescents – for example in the U.S. – face with mental health problems annually [ 1 ], and their behaviors lead to feelings of anxiety or depression [ 66 ]. The effects of mental health problems negatively influence the academic performance primarily [ 22 ], and as a result of it, more than one million adolescents drop out of school every year in the U. S. [ 23 ]. Mental health problems make adolescents face with a decline in academic achievement [ 67 ], which in turn results in school absence, poor grades, and even repeating a grade in school [ 68 ]. Those adolescents reporting high level of mental health problems are more likely to perceive themselves as less academically competent [ 69 ], and they display low academic achievement in school [ 70 ]. When schools identify problem behaviors with programs of intervention, it is likely to improve academic achievement of adolescents [ 71 ]. Well planned and well-implemented programs to foster mental health [ 72 ] can make adolescents achieve better academically in school [ 20 ]. However, in the U.S. – for example – 70 percent of adolescents who need mental health intervention cannot receive services [ 22 ], and nearly one third of them who need help receive treatment [ 8 ], which in turn negatively influences their academic achievement. Therefore, early detection of mental health problems of adolescents can have access to appropriate services which lead to improvement in both mental disorder symptoms and academic performance [ 73 ].

In addition to these overall findings, this meta-analysis also looked at the influence of some moderators in the association between mental health and academic achievement. It was revealed that no variables moderated the relationship between mental health and academic achievement, but not the setting. There was no significant relationship within sub-group variation in the relationship between mental health and academic achievement in terms of year of publication, publication type, community, and sample size.

First, year of publication did not appear to be a moderator in the association between mental health and academic achievement, indicating that the effect sizes of all studies included in the meta-analysis were similar. Second, the publications included in this meta-analysis were dissertations and journal articles. Although dissertations had a higher effect size compared to journal articles, publication type did not appear to be a moderator in the relationship between mental health and academic achievement. This showed that in spite of the fact that journal articles are selective to display significant results [ 74 ], they produced similar effect sizes as with dissertations which keep relatively minor results unpublished. Third, community did not appear to be a moderator in the association between mental health and academic achievement, which indicated that studies conducted both in urban and combination societies had similar effect sizes. This result revealed that mental health of adolescents living in both urban and combination communities is associated positively with academic achievement. Also, sample size did not appear to be a moderator in the relationship between mental health and academic achievement. Studies including more than 500 adolescents did not contribute significantly to the effect sizes, which indicated that the association between mental health and academic achievement was not affected by sample size.

However, it was indicated that setting appeared to be a significant moderator in the association between mental health and academic achievement. This result showed that studies conducted in the U.S. and countries out of the U.S. impacted differently to overall effect size. According to this result, countries out of the U.S., which are mainly Asian contexts, had a high effect size in the relationship between mental health and academic achievement. It may be due that the U.S. has relatively more racial and ethnic communities, or immigrants, compared to other countries, and such diversity of the U.S. may have an influence on the result obtained in the research. In the U.S. 70 percent of the adolescents need mental health interventions [ 22 ]; however, the situation is much more severe in minority communities [ 9 ]. Adolescents living in racial and ethnic communities in the U.S. are less likely to use mental health services due to poverty in particular [ 10 ]. Poverty has a disproportionate effect on racial and ethnic minorities, and adolescents who live in such condition are more likely to have a mental disorder [ 9 ]. As a result, almost half of the adolescents living in ethnic and racial communities in the U.S. fail to graduate due to the low level of academic achievement in school [ 75 ].

Lastly, although the meta-analysis included the studies which took place from 2000 to the present, no study could be reached in 2020 probably due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Since the outbreak in Wuhan, China, nearly all countries across the world has faced with the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. The pandemic has created severe consequences for millions of people in either losing their lives or their jobs. Many countries, including the U.S., the U.K., France, Germany, China, Italy, and Spain at the top, imposed lockdowns for several months and tried to prevent the fast spread of the virus. The pandemic not only affected general health of individuals and social lives of people, but it also impacted the schooling of many students. Most educational institutions around the world canceled in-person instruction and moved to distant teaching in an attempt to contain the spread of Covid-19 [ 76 ], and they are still pursuing this kind of teaching through digital platforms, such as Zoom, Skype, Google Meet, Microsoft Teams, and so on. Owing to the closure of schools, researchers have faced with considerable difficulty in reaching participants to conduct empirical studies; so this may have influenced the future research on the relationship between mental health and academic achievement in 2020.

On the other hand, the Covid-19 pandemic might have affected the mental health of adolescents worldwide because they were imposed curfew for several months at home. During the lockdown, millions of adolescents had to stay home, and they were in social isolation both from their peers and the society. Many countries implemented isolation policies for adolescents in particular, due to the fact that these individuals have the potential to spread the virus easily to relatively older people which may result in higher fatalities. Affected by the long months in lockdown, many adolescents had to spend their time at home and pursue their education through digital platforms. Many adolescents faced with severe difficulties in pursuing their education at home, as well as they had problems in access to treatment as a result of losing their mental health. Many students confined at home due to Covid-19 may have felt stressed and anxious, and this may negatively have affected their mental health [ 76 ]. Many adolescents, having mental health problems, have faced with severe academic difficulties and dropped out of school [ 77 ]. During the pandemic, the dropout rates in adolescents have substantially increased across the world, and this in turn may have affected their schooling negatively, particularly their academic achievement. However, there is no empirical evidence to support the relationship between mental health and academic achievement during the Covid-19 pandemic; therefore it is timely to conduct research to investigate this potential association to prevent mental health disorders in adolescents and improve their academic achievement. Although the present meta-analysis showed that there is a positive relationship between mental health and academic achievement in adolescents, this cannot be the case during the pandemic. Months of curfew and lockdown may have influenced the mental health and academic achievement of adolescents; so future research is needed to better clarify the relationship between these two phenomena.

5. Conclusion

The present meta-analysis aimed to determine the relationship between mental health and academic achievement in adolescents. This research, as expected, confirmed that there is a positive relationship between mental health and academic achievement. The research also indicated that mental health of adolescents is very important for schooling, in that it has a potential to influence academic achievement positively or negatively. Therefore, it is deemed crucial for adolescents to have a strong mental health to perform better academically in school, which in turn have lifelong consequences for employment, income, and other outcomes [ 21 ].

Results also indicated that there was no significant relationship within sub-group variation in the relationship between mental health and academic achievement in terms of year of publication, publication type, community, and sample size, but not the setting. It was indicated that setting appeared to be a significant moderator in the association between mental health and academic achievement. This result showed that studies conducted in the U.S. and countries out of the U.S. impacted differently to overall effect size. According to this result, countries out of the U.S. had a high effect size in the relationship between mental health and academic achievement. The effect size of the studies conducted in the U.S. was found to be relatively low, which implied that ethnic and racial diversity might have an impact on the result obtained in the research. This underlines the role of the school; thus, if schools identify mental health problems of adolescents with programs of intervention, it is likely to improve academic achievement [ 71 ]. Schools play an important role in determining the mental health of adolescents because they serve more than 95 percent of a country’s young people population [ 78 ].

A relatively small number of studies have been identified in the present meta-analysis, so more studies are needed to better clarify the relationship between mental health and academic achievement in adolescents. This research included only studies reported in English; therefore further meta-analyses might be conducted to include other reports out of English. Also, the role of school-based intervention programs in the relationship between mental health and academic achievement has not been taken into account in the present meta-analysis, so further research might be carried out to clarify the issue. The research has reported that school-based intervention programs may be effective to prevent mental health problems, and thus foster academic achievement [ 14 ]. In particular, adolescents living in ethnic and racial communities suffer from mental health problems, and academic achievement in school is influenced by such background. Because of this, mental health issues of adolescents living in ethnic and racial communities should be taken into consideration seriously.

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

- 1. National Institute of Mental Health 2018. Suicide statistics in the U.S. [Internet]. 2020.Available from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml [Accessed: 2020, 24 November]

- 2. Ball A. School mental health content in state in-service k-12 teaching standards in the United States. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2016; 60 : 312-320

- 3. American Academy of Pediatrics. Promoting children’s mental health. [Internet]. 2018. Available from https://www.aap.org/enus/advocacyandpolicy/federaladvocacy/Pages/mentalhealth.aspx [Accessed: 2019, September 12]

- 4. Michaud CM, McKenna MT, Begg S, Tomijima N, Majmudar M, Bulzacchelli MT, Ebrahim S, Ezzati M, Salomon JA, Kreiser JG, Hogan M, Murray CJL. The burden of disease and injury in the United States 1996. Population health metrics. 2006; 4 (1): 1-49

- 5. O’Connor M, Cloney D, Kvalsvig A, Goldfeld S. Positive mental health and academic achievement in elementary school: New evidence from a matching analysis. Educational Researcher. 2019. 48 (4): 205-216

- 6. Cash RE. Depression in children and adolescents: Information for parents and educators. [Internet]. 2004. Available from http://www.nasponline.org/resources/handouts/revisedPDFs/depression.pdf [Accessed: 2020, 24 November]

- 7. Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustun TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2007; 20 : 359-364

- 8. Schlozman S. The shrink in the classroom: Mental health specialists in schools. Educational Leadership. 2003; 60 (5): 80-83

- 9. Manson SM. Extending the boundaries, bridging the gaps: Crafting mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity, a supplement to the surgeon general’s report on mental health. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 2003; 27 (4): 395-408

- 10. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2001. Mental health: Culture, race and ethnicity-a supplement to mental health: A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: U. S. Department of Health and Human Services

- 11. Skaalski A, Smith M. Responding to the mental health needs of students. Principal Leadership. 2006; 7 (1): 12-15

- 12. Heiligenstein E, Guenther G, Hsu K, Herman K. Depression and academic impairment in college students. Journal of American College Health. 1996; 45 (2): 59-64

- 13. Hinman, C. Assessing the student at risk: A new look at school-based credit recovery. In: Guskey TR, editor. The Principal as Assessment Leader. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree; 2009. p. 225-242

- 14. Wiliams LO. The relationship between academic achievement and schoolbased mental health services for middle school students [dissertation]. Hattiesburg, MS: University of Southern Mississippi; 2012

- 15. Asarnow JR, Jaycox LH, Duan N, LaBorde AP, Rea MM, Tang L, Anderson M, Murray P, Landon C, Tang B, Huizar DP, Wells KB. Depression and role impairment among adolescents in primary care clinics. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005 ; 37 : 477-483

- 16. DeBerard MS, Spielmans GI, Julka DL. Predictors of academic achievement and retention among college freshmen: A longitudinal study. College Student Journal, 2004; 38 (1): 66-81

- 17. Roeser RW, Eccles JS, Strobel KR. Linking the study of schooling and mental health: Selected issues and empirical illustrations at the level of the individual. Educational Psychologist. 1998; 33 : 153-176

- 18. Roeser RW, Eccles JS, Strobel KR. Linking the study of schooling and mental health: Selected issues and empirical illustrations at the level of the individual. Educational Psychologist. 1998; 33 : 153-176

- 19. Malecki CK, Elliott SN. Children’s social behaviors as predictors of academic achievement: A longitudinal analysis. School Psychology Quarterly. 2002 ; 17 : 1-23

- 20. Zins JE, Bloodworth MR, Weissberg RP, Walberg HJ. The scientific base linking social and emotional learning to school success. In: Zins J, Weissberg R, Wang M, Walberg HJ. editors, Building Academic Success on Social and Emotional Learning: What Does the Research Say? New York , NY: Teachers College Press; 2004. p. 3-22

- 21. Eisenberg D., Golberstein E, Hunt J. Mental health and academic success in college. B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy. 2009; 9 (1): 1-35

- 22. Whelley P, Cash RE, Bryson D. Children’s mental health: Information for educators [Internet]. 2003. Available from http://www.nasponline.org/resources/ handouts/abcs_handout.pdf [Accessed: 2020, October 04]

- 23. Hinman C. Assessing the student at risk: A new look at school-based credit recovery. In: Guskey TR, editor. The Principal as Assessment Leader. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree; 2009. p. 225-242

- 24. Lipsey M, Wilson D. Practical Meta-Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001

- 25. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009

- 26. Durlak JA. Basic Principles of Meta-Analysis. In: Roberts MC, Ilardi SS, editors. Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology. Oxford: Blackwell; 2008. p. 196-209

- 27. White G W. Mental health and academic achievement: The effects of self-efficacy. [dissertation]. New Brunswick, NJ: The State University of New Jersey; 2016

- 28. Sathiyaraj M, Babu R. A Study of academic achievement and mental health of the special school students. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 2016; 21 (12): 49-52

- 29. Chung EW-Y. Resilence, complete mental health and academic achievement in traditional and non-traditional first year psychology students. [dissertation]. Adelaide: University of Adeaide; 2016

- 30. Eisenberg D, Golberstein E, Hunt J. Mental health and academic success in college. B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy. 2009; 9 (1): 1-35

- 31. Gilavand A, Shooriabi M. Investigating the Relationship between mental health and academic achievement of dental students of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences. International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences. 2016; 5 (7): 328-333

- 32. Mundia L. Effects of psychological distress on academic achievement in Brunei student teachers: Identification challenges and counseling implications. Higher Education Studies. 2011; 1 (1): 51-63

- 33. Geetha V. Mental health and academic achievement of B.ED. students. [dissertation]. Madurai: Madurai Kamaraj University; 2014

- 34. Jenkins AS. Associations between mental health, academic success, and perceived stress among high school freshman in accelerated coursework. [dissertation]. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida; 2019

- 35. Singh SK. Mental health and academic achievement of college students. The International Journal of Indian Psychology. 2015; 2 (4): 112-119

- 36. Sheykhjan TM., Rajeswari K, Jabari K. Mental health and academic achievement among M.Ed. Students in Kerala. Studies in Eduation. 2017; 2 (1): 115-123

- 37. Murphy JM, Guzmán J, McCarthy A, Squicciarini AM, George M, Canenguez K, Dunn EC, Baer L, Simonsohn A, Smoller JW, Jellinek M. Mental health predicts better academic outcomes: A longitudinal study of elementary school students in Chile. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2015; 46 (2): 245-256

- 38. Talawar MS, Anindita D. A study of relationship between academic achievement and mental health of secondary school tribal students of Assam. Paripex: Indian Journal of Research. 2014; 3 (11): 55-57

- 39. Manchri H, Sanagoo A, Jouybari L, Sabzi Z, Jafari SY. The relationship between mental health status with academic performance and demographic factors among students of university of medical sciences. Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Sciences. 2017; 4 (1): 8-13

- 40. Hall JA, Rosenthal R. Testing for moderator variables in meta-analysis: Issues and methods. Communications Monographs. 1991; 58 (4): 437-448

- 41. Cooper H, Hedges, LV, Valentine JC, editors. Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Russell Sage; 2009

- 42. Rosenthal R. Meta-Analytic Procedures for Social Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991

- 43. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009

- 44. Hedges L, Olkin I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1985

- 45. Kulinskaya E, Morgenthaler S, Staudte RG. Meta Analysis: A Guide to Calibrating and Combining Statistical Evidence. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2008

- 46. Hedges L, Olkin I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1985

- 47. Ellis PD. The Essential Guide to Effect Sizes: Statistical Power, Meta-Analysis, and the Interpretation of Research Results. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010

- 48. Shelby LB, Vaske JJ. Understanding meta-analysis: A review of the methodological literature. Leisure Sciences. 2008; 30 (2): 96-110

- 49. Lipsey M, Wilson D. Practical Meta-Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001

- 50. Hunter JE., Schmidt FL. Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2004

- 51. Card NA. Applied Meta-Analysis for Social Science Research. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012

- 52. Hartung J, Knapp G, Sinha BK. Bayesian Meta-Analysis: Statistical Meta-Analysis with Applications. New York, NY: John Wiles & Sons; 2008

- 53. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1992; 1 (3): 98-101

- 54. Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M, editors. Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments. New York, NY: Wiley; 2005

- 55. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009

- 56. Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M, editors. Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments. New York, NY: Wiley; 2005

- 57. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009

- 58. Sterne JA, Becker BJ, Egger M. The funnel plot. In: Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M, editors. Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments. London: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. p. 75-98

- 59. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009

- 60. Sterne JA, Egger M. Regression methods to detect publication and other bias in meta-analysis. In: Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M, editors. Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments. London: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. p. 99-110

- 61. Rosenthal R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin. 1979 ; 86 (3): 638-641

- 62. Orwin RG. A fail-safe N for effect size in meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Statistics. 1983; 8 (2): 157-159

- 63. Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000; 56 : 455-463

- 64. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009

- 65. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1992; 1 (3): 98-101

- 66. Repie, M. A School mental health issues survey from the perspective of regular and special education teachers, school counselors, and school psychologists. Education and Treatment of Children. 2005; 28 (3): 279-298

- 67. Suldo S, Thalji A, Ferron J. Longitudinal academic outcomes predicted by early adolescents’ subjective well-being, psychopathology, and mental health status yielded from a dual factor model. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2011; 6 (1): 17-30

- 68. Gall G, Pagano ME, Desmond MS, Perrin JM, Murphy JM. Utility of psychosocial screening at a school-based health center. Journal of School Health. 2000; 70 (7): 292-298

- 69. Masi G, Tomaiuolo F, Sbrana B, Poli P, Baracchini G, Pruneti CA, Favilla L, Floriani C, Marcheschi M. Depressive symptoms and academic self-image in adolescence. Psychopathology. 2001; 34 : 57-61

- 70. Fosterling F, Binser MJ. Depression, school performance and the veridicality of perceived grades and causal attributions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002; 28 (10): 1441-1449

- 71. Fleming CB, Haggerty KP, Catalano RF. Do social and behavioral characteristics targeted by preventive interventions predict standardized test scores and grades? Journal of School Health. 2005; 75 (9): 342-349

- 72. Greenberg MT, Weissberg RP, O’Brien MU, Zins JE, Fredericks L, Resnick H, Elias MJ. Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development though coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. American Psychologist. 2003; 58 : 466-474

- 73. Baskin TW, Slaten CD, Sorenson C, Glover-Russell J, Merson DN. Does youth psychotherapy improve academically related outcomes? A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010; 57 (3): 290-296

- 74. Iyenger S, Greenhouse JB. Selection models and the file drawer problem. Statistical Science. 1988; 3 :109-135

- 75. U. S. Department of Education. ESEA Blueprint for Reform. Washington, DC: U. S. Department of Education; 2010

- 76. Di Pietro G, Biagi F, Costa P, Karpiński Z, Mazza J. The likely Impact of COVID-19 on Education: Reflections Based on the Existing Literature and International Datasets. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2020

- 77. United Nations. Policy Brief: Education During COVID-19 and Beyond. New York, NY: United Nations; 2020

- 78. Dunn E, Milliren C, Evans C, Subramanian S, Richmond T. Disentangling the relative influence of schools and neighborhoods on adolescents’ risk for depressive symptoms. American Journal of Public Health. 2015; 105 (4): 732-740

© 2021 The Author(s). Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Continue reading from the same book

Health and academic achievement.

Published: 12 May 2021

By Edith M. Sebatane, Maretšepile Mahamo and Phaello ...

719 downloads

By Herring Shava and Willie Tafadzwa Chinyamurindi

561 downloads

By Christopher Applegate

553 downloads

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Relationship Between Achievement Motivation, Mental Health and Academic Success in University Students

Affiliations.

- 1 Student Research Committee, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran.

- 2 Student Research Committee, Fasa University of Medical Sciences, Fasa, Iran.

- 3 Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran.

- 4 Spiritual Health Research Center, Research Institute for Health Development, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran.

- PMID: 34176355

- DOI: 10.1177/0272684X211025932

Students of medical sciences are under intense mental stress induced by medical training system and are more likely to develop psychological and mental disorders. These psychological disorders may influence their performance in different aspects of life including their study. The aim of the present study is to assess the possible relationships between mental health, achievement motivation, and academic achievement and to study the effect of background factors on mentioned variables. The sample group consists of students of Kurdistan University of medical sciences. 430 students at Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences were selected randomly to participate in the present cross-sectional study in 2016. We used General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) and Achievement motivation test (AMT) as the measures of our study. Our findings indicated that mental health is significantly correlated with achievement motivation ( p < .001), but has no correlation with educational success ( p = .37). Also, a significant relationship was observed between achievement motivation and academic achievement ( p = .025). GHQ was not correlated with demographic factors, while academic achievement and achievement motivation are associated with the field of study and marital status respectively. Conclusively, students who are more motivated to achieve their educational and academic goals, will be more likely to be successful in their education and have stronger academic performance. Also, students with more appropriate mental health status will have higher level of motivation in their education and studies. These findings reflect the importance of maintaining the medical field students' motivation and its role in their academic success.

Keywords: academic success; anxiety; depression; mental health; motivation.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Exploring the effects of health behaviors and mental health on students' academic achievement: a cross-sectional study on lebanese university students. Hammoudi Halat D, Hallit S, Younes S, AlFikany M, Khaled S, Krayem M, El Khatib S, Rahal M. Hammoudi Halat D, et al. BMC Public Health. 2023 Jun 26;23(1):1228. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-16184-8. BMC Public Health. 2023. PMID: 37365573 Free PMC article.

- Anesthesia students' perception of the educational environment and academic achievement at Debre Tabor University and University of Gondar, Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. Negash TT, Eshete MT, Hanago GA. Negash TT, et al. BMC Med Educ. 2022 Jul 15;22(1):552. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03611-4. BMC Med Educ. 2022. PMID: 35840966 Free PMC article.

- Moderating role of academic motivation and entitlement between motives of students and academic achievement among university students. Bano S, Riaz MN. Bano S, et al. J Pak Med Assoc. 2023 Apr;73(4):759-762. doi: 10.47391/JPMA.01016. J Pak Med Assoc. 2023. PMID: 37051978

- The Influence of Teachers' Management Efficiency and Motivation on College Students' Academic Achievement under Sustainable Innovation and the Cognition of Social Responsibility after Employment. Tan C, Yi L, Haider A, Kwen L, Mamnoon R, Li K, Liu M. Tan C, et al. J Environ Public Health. 2022 Aug 25;2022:1663120. doi: 10.1155/2022/1663120. eCollection 2022. J Environ Public Health. 2022. PMID: 36060872 Free PMC article. Retracted. Review.

- Optimizing Students' Mental Health and Academic Performance: AI-Enhanced Life Crafting. Dekker I, De Jong EM, Schippers MC, De Bruijn-Smolders M, Alexiou A, Giesbers B. Dekker I, et al. Front Psychol. 2020 Jun 3;11:1063. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01063. eCollection 2020. Front Psychol. 2020. PMID: 32581935 Free PMC article. Review.

- The mediating role of emotional intelligence in the relationship between learning motivation and academic outcomes: Conditional indirect effect of gender. Sayed SH. Sayed SH. J Educ Health Promot. 2024 Apr 29;13:123. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_965_23. eCollection 2024. J Educ Health Promot. 2024. PMID: 38784288 Free PMC article.

- Achievement Motivation Among Health Sciences and Engineering Students During COVID-19. Suraj S, Kohle S, Prakash A, Tendolkar V, Gawande U. Suraj S, et al. Ann Neurosci. 2024 Jan;31(1):36-43. doi: 10.1177/09727531231169628. Epub 2023 Jun 28. Ann Neurosci. 2024. PMID: 38584986 Free PMC article.

- Relationship between academic success, distance education learning environments, and its related factors among medical sciences students: a cross-sectional study. Ghasempour S, Esmaeeli M, Abbasi A, Hosseinzadeh A, Ebrahimi H. Ghasempour S, et al. BMC Med Educ. 2023 Nov 9;23(1):847. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04856-3. BMC Med Educ. 2023. PMID: 37946138 Free PMC article.

- Identifying academic motivation profiles and their association with mental health in medical school. Oláh B, Münnich Á, Kósa K. Oláh B, et al. Med Educ Online. 2023 Dec;28(1):2242597. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2023.2242597. Med Educ Online. 2023. PMID: 37535843 Free PMC article.

- Predictors of Academic Success in Students of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences: A Cross-Sectional Study. Maghalian M, Ghafari R, Osouli Tabrizi S, Nikkhesal N, Mirghafourvand M. Maghalian M, et al. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2023 Jul;11(3):155-163. doi: 10.30476/JAMP.2022.96841.1725. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2023. PMID: 37469380 Free PMC article.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Research on the Relationship Between Mental Health and Academic Achievement

Related Papers

Allison Dymnicki , H. Resnick

Collaborative For Academic Social and Emotional Learning

Allison Dymnicki

Elise Cappella

Social-emotional learning (SEL) programs have demonstrated positive effects on children’s social-emotional, behavioral, and academic outcomes, as well as classroom climate. Some programs also theorize that program impacts on children’s outcomes will be partially explained by improvements in classroom social processes, namely classroom emotional support and organization. Yet there is little empirical evidence for this hypothesis. Using data from the evaluation of the SEL program INSIGHTS, this article tests whether assignment to INSIGHTS improved low-income kindergarten and first grade students’ math and reading achievement by first enhancing classroom emotional support and organization. Multilevel regression analyses, instrumental variables estimation, and inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) were used to conduct quantitative analyses. Across methods, the impact of INSIGHTS on math and reading achievement in first grade was partially explained by gains in both classroom...

Journal of Intelligence

Maria Adamuti-Trache

A central component of adolescents’ social and emotional learning (SEL) consists of their ability to foster positive relationship skills through connectedness with their school community. This study focuses on the assessment of student’s SEL competencies in relation to their socio-demographic characteristics, formal and informal socialization behaviors, and academic outcomes in both public and private schools. The research is based on the secondary analysis of large-scale nationally representative data from the High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 (HSLS:2009) and focuses on ninth graders experiencing the transition to secondary education. Guided by both SEL and school climate frameworks, we identified survey items that describe students’ feelings of acceptance, pride, and support in their grade nine learning environment as indicators of perceptions of school climate and builders of SEL skills and used multivariate statistical analysis to examine how SEL skills and behavioral socia...

Norris M . Haynes, Ph.D.

Joseph Durlak

Journal of Educational …

Michelle Bloodworth

Handbook of curriculum development

Jeffrey Liew

Journal of School Health

David DuBois

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Meghan P McCormick , Elise Cappella , Sandee McClowry

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Advertisement

The Relationship between Mental Health, Acculturative Stress, and Academic Performance in a Latino Middle School Sample

- Published: 27 February 2014

- Volume 18 , pages 178–186, ( 2014 )

Cite this article

- Loren J. Albeg 1 &

- Sara M. Castro-Olivo 1

1986 Accesses

23 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This study evaluated the relationship between acculturative stress, symptoms of internalizing mental health problems, and academic performance in a sample of 94 Latino middle school students. Students reported on symptoms indicative of depression and anxiety related problems and acculturative stress. Teachers reported on students’ academic behavior and performance. Acculturative stress and symptoms of internalizing mental health problems were found to have a significant inverse association with students’ academic performance. Implications for the development of culturally responsive interventions that address mental health problems and acculturative stress are discussed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Teacher stress and burnout in Australia: examining the role of intrapersonal and environmental factors

School climate: a review of the construct, measurement, and impact on student outcomes.

Relations between students’ well-being and academic achievement: evidence from Swedish compulsory school

Agresti, A., & Finlay, B. (2009). Statistical methods for the social sciences (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Google Scholar

Alfaro, E. C., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Gonzales-Backen, M. A., Bámaca, M. Y., & Zeiders, K. H. (2009). Latino adolescents' academic success: The role of discrimination, academic motivation, and gender. Journal of Adolescence, 32 (4), 941–962. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.08.007 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Alva, S. A., & de los Reyes, R. (1999). Psychosocial stress, internalized symptoms, and the academic achievement of Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 14 (3), 343–358. doi: 10.1177/0743558499143004 .

Article Google Scholar

American Psychological Association. (2002). Guidelines on multicultural education, training, research, practice, and organizational change for psychologists. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pi/multiculturalguidelines/scope.html .

Aud, S., Fox, M., & KewalRamani, A. (2010). Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic groups (NCES 2010–015). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2010015 .

Bernal, G., Bonilla, J., & Bedillo, C. (1995). Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: Issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychological treatments with Hispanics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23 (1), 67–82.