How to Stop Corruption Essay: Guide & Topics [+4 Samples]

Corruption is an abuse of power that was entrusted to a person or group of people for personal gain. It can appear in various settings and affect different social classes, leading to unemployment and other economic issues. This is why writing an essay on corruption can become a challenge.

One “how to stop corruption” essay will require plenty of time and effort, as the topic is too broad. That’s why our experts have prepared this guide. It can help you with research and make the overall writing process easier. Besides, you will find free essays on corruption with outlines.

- ✍️ How to Write an Essay

- 💰 Essay Examples

- 🤑 How to Stop Corruption Essay

- 💲 Topics for Essay

✍️ How to Write an Essay on Corruption

Before writing on the issue, you have to understand a few things. First , corruption can take different forms, such as:

- Bribery – receiving money or other valuable items in exchange for using power or influence in an illegal way.

- Graft – using power or authority for personal goals.

- Extortion – threats or violence for the person’s advantage.

- Kickback – paying commission to a bribe-taker for some service.

- Cronyism – assigning unqualified friends or relatives to job positions.

- Embezzlement – stealing the government’s money.

Second , you should carefully think about the effects of corruption on the country. It seriously undermines democracy and the good name of political institutions. Its economic, political, and social impact is hard to estimate.

Let’s focus on writing about corruption. What are the features of your future paper? What elements should you include in your writing?

Below, we will show you the general essay on corruption sample and explain each part’s importance:

You already chose the paper topic. What’s next? Create an outline for your future writing. You’re better to compose a plan for your paper so that it won’t suffer from logic errors and discrepancies. Besides, you may be required to add your outline to your paper and compose a corruption essay with headings.

At this step, you sketch out the skeleton:

- what to write in the introduction;

- what points to discuss in the body section;

- what to put into the conclusion.

Take the notes during your research to use them later. They will help you to put your arguments in a logical order and show what points you can use in the essay.

For a long-form essay, we suggest you divide it into parts. Title each one and use headings to facilitate the reading process.

🔴 Introduction

The next step is to develop a corruption essay’s introduction. Here, you should give your readers a preview of what’s coming and state your position.

- Start with a catchy hook.

- Give a brief description of the problem context.

- Provide a thesis statement.

You can always update and change it when finishing the paper.

🔴 Body Paragraphs

In the body section, you will provide the central points and supporting evidence. When discussing the effects of this problem in your corruption essay, do not forget to include statistics and other significant data.

Every paragraph should include a topic sentence, explanation, and supporting evidence. To make them fit together, use analysis and critical thinking.

Use interesting facts and compelling arguments to earn your audience’s attention. It may drift while reading an essay about corruption, so don’t let it happen.

🔴 Quotations

Quotes are the essential elements of any paper. They support your claims and add credibility to your writing. Such items are exceptionally crucial for an essay on corruption as the issue can be controversial, so you may want to back up your arguments.

- You may incorporate direct quotes in your text. In this case, remember to use quotation marks and mark the page number for yourself. Don’t exceed the 30 words limit. Add the information about the source in the reference list.

- You may decide to use a whole paragraph from your source as supporting evidence. Then, quote indirectly—paraphrase, summarize, or synthesize the argument of interest. You still have to add relevant information to your reference list, though.

Check your professor’s guidelines regarding the preferred citation style.

🔴 Conclusion

In your corruption essay conclusion, you should restate the thesis and summarize your findings. You can also provide recommendations for future research on the topic. Keep it clear and short—it can be one paragraph long.

Don’t forget your references!

Include a list of all sources you used to write this paper. Read the citation guideline of your institution to do it correctly. By the way, some citation tools allow creating a reference list in pdf or Word formats.

💰 Corruption Essay Examples

If you strive to write a good how to stop a corruption essay, you should check a few relevant examples. They will show you the power of a proper outline and headings. Besides, you’ll see how to formulate your arguments and cite sources.

✔️ Essay on Corruption: 250 Words

If you were assigned a short paper of 250 words and have no idea where to start, you can check the example written by our academic experts. As you can see below, it is written in easy words. You can use simple English to explain to your readers the “black money” phenomenon.

Another point you should keep in mind when checking our short essay on corruption is that the structure remains the same. Despite the low word count, it has an introductory paragraph with a thesis statement, body section, and a conclusion.

Now, take a look at our corruption essay sample and inspire!

✔️ Essay on Corruption: 500 Words

Cause and effect essay is among the most common paper types for students. In case you’re composing this kind of paper, you should research the reasons for corruption. You can investigate factors that led to this phenomenon in a particular country.

Use the data from the official sources, for example, Transparency International . There is plenty of evidence for your thesis statement on corruption and points you will include in the body section. Also, you can use headlines to separate one cause from another. Doing so will help your readers to browse through the text easily.

Check our essay on corruption below to see how our experts utilize headlines.

🤑 How to Stop Corruption: Essay Prompts

Corruption is a complex issue that undermines the foundations of justice, fairness, and equality. If you want to address this problem, you can write a “How to Stop Corruption” essay using any of the following topic ideas.

The writing prompts below will provide valuable insights into this destructive phenomenon. Use them to analyze the root causes critically and propose effective solutions.

How to Prevent Corruption Essay Prompt

In this essay, you can discuss various strategies and measures to tackle corruption in society. Explore the impact of corruption on social, political, and economic systems and review possible solutions. Your paper can also highlight the importance of ethical leadership and transparent governance in curbing corruption.

Here are some more ideas to include:

- The role of education and public awareness in preventing corruption. In this essay, you can explain the importance of teaching ethical values and raising awareness about the adverse effects of corruption. It would be great to illustrate your essay with examples of successful anti-corruption campaigns and programs.

- How to implement strong anti-corruption laws and regulations. Your essay could discuss the steps governments should take in this regard, such as creating comprehensive legislation and independent anti-corruption agencies. Also, clarify how international cooperation can help combat corruption.

- Ways of promoting transparency in government and business operations. Do you agree that open data policies, whistleblower protection laws, independent oversight agencies, and transparent financial reporting are effective methods of ensuring transparency? What other strategies can you propose? Answer the questions in your essay.

How to Stop Corruption as a Student Essay Prompt

An essay on how to stop corruption as a student can focus on the role of young people in preventing corruption in their communities and society at large. Describe what students can do to raise awareness, promote ethical behavior, and advocate for transparency and accountability. The essay can also explore how instilling values of integrity and honesty among young people can help combat corruption.

Here’s what else you can talk about:

- How to encourage ethical behavior and integrity among students. Explain why it’s essential for teachers to be models of ethical behavior and create a culture of honesty and accountability in schools. Besides, discuss the role of parents and community members in reinforcing students’ moral values.

- Importance of participating in anti-corruption initiatives and campaigns from a young age. Your paper could study how participation in anti-corruption initiatives fosters young people’s sense of civic responsibility. Can youth engagement promote transparency and accountability?

- Ways of promoting accountability within educational institutions. What methods of fostering accountability are the most effective? Your essay might evaluate the efficacy of promoting direct communication, establishing a clear code of conduct, creating effective oversight mechanisms, holding all members of the educational process responsible for their actions, and other methods.

How to Stop Corruption in India Essay Prompt

In this essay, you can discuss the pervasive nature of corruption in various sectors of Indian society and its detrimental effects on the country’s development. Explore strategies and measures that can be implemented to address and prevent corruption, as well as the role of government, civil society, and citizens in combating this issue.

Your essay may also include the following:

- Analysis of the causes and consequences of corruption in India. You may discuss the bureaucratic red tape, weak enforcement mechanisms, and other causes. How do they affect the country’s development?

- Examination of the effectiveness of existing anti-corruption laws and measures. What are the existing anti-corruption laws and measures in India? Are they effective? What are their strengths and weaknesses?

- Discussion of potential solutions and reforms to curb corruption. Propose practical solutions and reforms that can potentially stop corruption. Also, explain the importance of political will and international cooperation to implement reforms effectively.

Government Corruption Essay Prompt

A government corruption essay can discuss the prevalence of corruption within government institutions and its impact on the state’s functioning. You can explore various forms of corruption, such as bribery, embezzlement, and nepotism. Additionally, discuss their effects on public services, economic development, and social justice.

Here are some more ideas you can cover in your essay:

- The causes and manifestations of government corruption. Analyze political patronage, weak accountability systems, and other factors that stimulate corruption. Additionally, include real-life examples that showcase the manifestations of government corruption in your essay.

- The impact of corruption on public trust and governance. Corruption undermines people’s trust and increases social inequalities. In your paper, we suggest evaluating its long-term impact on countries’ development and social cohesion.

- Strategies and reforms to combat government corruption. Here, you can present and examine the best strategies and reforms to fight corruption in government. Also, consider the role of international organizations and media in advocating for anti-corruption initiatives.

How to Stop Police Corruption Essay Prompt

In this essay, you can explore strategies and reforms to address corruption within law enforcement agencies. Start by investigating the root causes of police corruption and its impact on public safety and trust. Then, propose effective measures to combat it.

Here’s what else you can discuss in your essay:

- The factors contributing to police corruption, such as lack of accountability and oversight. Your paper could research various factors that cause police corruption. Is it possible to mitigate their effect?

- The consequences of police corruption for community relations and public safety. Police corruption has a disastrous effect on public safety and community trust. Your essay can use real-life examples to show how corruption practices in law enforcement undermine their legitimacy and fuel social unrest.

- Potential solutions, such as improved training, transparency, and accountability measures. Can these measures solve the police corruption issue? What other strategies can be implemented to combat the problem? Consider these questions in your essay.

💲 40 Best Topics for Corruption Essay

Another key to a successful essay on corruption is choosing an intriguing topic. There are plenty of ideas to use in your paper. And here are some topic suggestions for your writing:

- What is corruption? An essay should tell the readers about the essentials of this phenomenon. Elaborate on the factors that impact its growth or reduce.

- How to fight corruption ? Your essay can provide ideas on how to reduce the effects of this problem. If you write an argumentative paper, state your arguments, and give supporting evidence. For example, you can research the countries with the lowest corruption index and how they fight with it.

- I say “no” to corruption . This can be an excellent topic for your narrative essay. Describe a situation from your life when you’re faced with this type of wrongdoing.

- Corruption in our country. An essay can be dedicated, for example, to corruption in India or Pakistan. Learn more about its causes and how different countries fight with it.

- Graft and corruption. We already mentioned the definition of graft. Explore various examples of grafts, e.g., using the personal influence of politicians to pressure public service journalists . Provide your vision of the causes of corruption. The essay should include strong evidence.

- Corruption in society. Investigate how the tolerance to “black money” crimes impact economics in developing countries .

- How can we stop corruption ? In your essay, provide suggestions on how society can prevent this problem. What efficient ways can you propose?

- The reasons that lead to the corruption of the police . Assess how bribery impacts the crime rate. You can use a case of Al Capone as supporting evidence.

- Literature and corruption. Choose a literary masterpiece and analyze how the author addresses the theme of crime. You can check a sample paper on Pushkin’s “ The Queen of Spades ”

- How does power affect politicians ? In your essay on corruption and its causes, provide your observations on ideas about why people who hold power allow the grafts.

- Systemic corruption in China . China has one of the strictest laws on this issue. However, crime still exists. Research this topic and provide your observations on the reasons.

- The success of Asian Tigers . Explore how the four countries reduced corruption crime rates. What is the secret of their success? What can we learn from them?

- Lee Kuan Yew and his fight against corruption. Research how Singapore’s legislation influenced the elimination of this crime.

- Corruption in education. Examine the types in higher education institutions. Why does corruption occur?

- Gifts and bribes . You may choose to analyze the ethical side of gifts in business. Can it be a bribe? In what cases?

- Cronyism and nepotism in business. Examine these forms of corruption as a part of Chinese culture.

- Kickbacks and bribery. How do these two terms are related, and what are the ways to prevent them?

- Corporate fraud. Examine the bribery, payoffs, and kickbacks as a phenomenon in the business world. Point out the similarities and differences.

- Anti-bribery compliance in corporations. Explore how transnational companies fight with the misuse of funds by contractors from developing countries.

- The ethical side of payoffs. How can payoffs harm someone’s reputation? Provide your point of view of why this type of corporate fraud is unethical.

- The reasons for corruption of public officials.

- Role of auditors in the fight against fraud and corruption.

- The outcomes of corruption in public administration .

- How to eliminate corruption in the field of criminal justice .

- Is there a connection between corruption and drug abuse ?

- The harm corruption does to the economic development of countries .

- The role of anti-bribery laws in fighting financial crimes.

- Populist party brawl against corruption and graft.

- An example of incorrigible corruption in business: Enron scandal .

- The effective ways to prevent corruption .

- The catastrophic consequences of corruption in healthcare.

- How regular auditing can prevent embezzlement and financial manipulation.

- Correlation between poverty and corruption .

- Unethical behavior and corruption in football business.

- Corruption in oil business: British Petroleum case.

- Are corruption and bribery socially acceptable in Central Asian states?

- What measures should a company take to prevent bribery among its employees?

- Ways to eliminate and prevent cases of police corruption .

- Gift-giving traditions and corruption in the world’s culture.

- Breaking business obligations: embezzlement and fraud.

These invaluable tips will help you to get through any kind of essay. You are welcome to use these ideas and writing tips whenever you need to write this type of academic paper. Share the guide with those who may need it for their essay on corruption.

This might be interesting for you:

- Canadian Identity Essay: Essay Topics and Writing Guide

- Nationalism Essay: An Ultimate Guide and Topics

- Human Trafficking Essay for College: Topics and Examples

- Murder Essay: Top 3 Killing Ideas to Complete your Essay

🔗 References

- Public Corruption: FBI, U.S. Department of Justice

- Anti-Corruption and Transparency: Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

- United Nations Convention against Corruption: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

- Corruption Essay: Cram

- How to Construct an Essay: Josh May

- Essay Writing: University College Birmingham

- Structuring the Essay: Research & Learning Online

- Insights from U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre: Medium

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

Do you have to write an essay for the first time? Or maybe you’ve only written essays with less than 1000 words? Someone might think that writing a 1000-word essay is a rather complicated and time-consuming assignment. Others have no idea how difficult thousand-word essays can be. Well, we have...

To write an engaging “If I Could Change the World” essay, you have to get a few crucial elements: Let us help you a bit and give recommendations for “If I Could Change the World” essays with examples. And bookmark our writing company website for excellent academic assistance and study...

![how to reduce corruption essay Why I Want to be a Pharmacist Essay: How to Write [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/cut-out-medicament-drug-doctor-medical-1-284x153.jpg)

Why do you want to be a pharmacist? An essay on this topic can be challenging, even when you know the answer. The most popular reasons to pursue this profession are the following:

How to write a film critique essay? To answer this question, you should clearly understand what a movie critique is. It can be easily confused with a movie review. Both paper types can become your school or college assignments. However, they are different. A movie review reveals a personal impression...

Are you getting ready to write your Language Proficiency Index Exam essay? Well, your mission is rather difficult, and you will have to work hard. One of the main secrets of successful LPI essays is perfect writing skills. So, if you practice writing, you have a chance to get the...

![how to reduce corruption essay Dengue Fever Essay: How to Write It Guide [2024 Update]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/scientist-hand-is-holding-test-plate-284x153.jpg)

Dengue fever is a quite dangerous febrile disease that can even cause death. Nowadays, this disease can be found in the tropics and Africa. Brazil, Singapore, Taiwan, Indonesia, and India are also vulnerable to this disease.

For high school or college students, essays are unavoidable – worst of all, the essay types and essay writing topics assigned change throughout your academic career. As soon as you’ve mastered one of the many types of academic papers, you’re on to the next one. This article by Custom Writing...

Even though a personal essay seems like something you might need to write only for your college application, people who graduated a while ago are asked to write it. Therefore, if you are a student, you might even want to save this article for later!

If you wish a skill that would be helpful not just for middle school or high school, but also for college and university, it would be the skill of a five-paragraph essay. Despite its simple format, many students struggle with such assignments.

Reading books is pleasurable and entertaining; writing about those books isn’t. Reading books is pleasurable, easy, and entertaining; writing about those books isn’t. However, learning how to write a book report is something that is commonly required in university. Fortunately, it isn’t as difficult as you might think. You’ll only...

![how to reduce corruption essay Best Descriptive Essays: Examples & How-to Guide [+ Tips]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/pencil-notebook-white-background-284x153.jpg)

A descriptive essay is an academic paper that challenges a school or college student to describe something. It can be a person, a place, an object, a situation—anything an individual can depict in writing. The task is to show your abilities to communicate an experience in an essay format using...

An analysis / analytical essay is a standard assignment in college or university. You might be asked to conduct an in-depth analysis of a research paper, a report, a movie, a company, a book, or an event. In this article, you’ll find out how to write an analysis paper introduction,...

Thank you for these great tips now i can work with ease cause one does not always know what the marker will look out fr. So this is ever so helpfull keep up the great work

This article was indeed helpful a whole lot. Thanks very much I got all I needed and more.

I can’t thank this website enough. I got all and more that I needed. It was really helpful…. thanks

Really, it’s helpful.. Thanks

Really, it was so helpful, & good work 😍😍

Thanks and this was awesome

I love this thanks it is really helpful

Strategies for winning the fight against corruption

Subscribe to africa in focus, ngozi okonjo-iweala ngozi okonjo-iweala nonresident distinguished fellow - global economy and development , africa growth initiative @noiweala.

January 15, 2019

Below is a viewpoint from Chapter 1 of the Foresight Africa 2019 report, which explores six overarching themes on the triumphs of the past years as well as strategies to tackle the remaining obstacles for Africa. Read the full chapter on bolstering good governance .

That corruption and poor governance are key factors holding back Africa’s development are notions deeply embedded in the literature and thought on Africa’s socioeconomic development. What is not so common is discourse and success stories about how to systematically fight this corruption. Though this may sound discouraging, I can tell you, from my experience, that it is indeed possible to fight corruption successfully with the right knowledge, patience, and commitment to transparency.

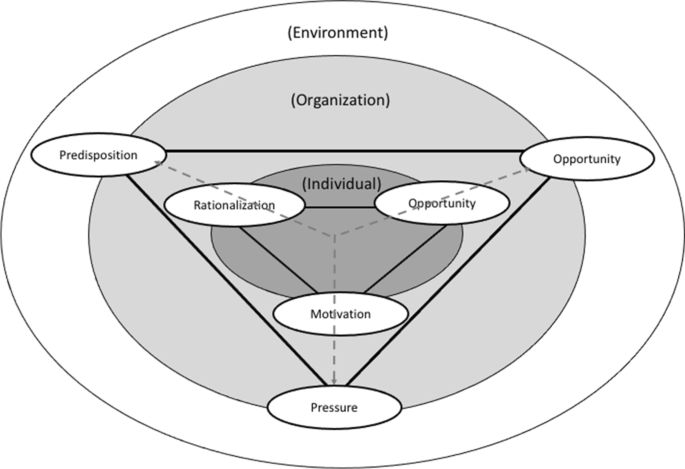

To fight corruption, we must first understand it. Underlying the various forms of corruption—grand, political, and administrative, which include public resource transfers to private entities, allocation of public resources to political allies, and misuse of public funds—are three important factors. The first is a lack of transparency of critical financial and other information central to economic development, in particular revenues and budgets. Second is the weakness or total absence of institutions, systems, and processes that block leakages. Third is the pervasiveness of impunity—limited political will to hold accountable and punish those found guilty of such corruption.

Between the three, the tougher problem is how to build strong and enduring institutions. Building institutions takes time and does not deliver the quick results that typically attract politicians or donors. But it is essential if Africa is to fight corruption systematically and ensure long-term stability. We are fortunate to now have technology that enables us to build electronic platforms to manage government finances, biometric systems to bring integrity to our personnel and government payment systems, and web-based platforms to provide transparency of government finances. We need to go even further to see how we can deploy blockchain and other emerging technologies to underpin our contract negotiations and procurement systems, a huge source of corruption and leakage in many countries.

Africa needs to focus its anti-corruption fight on long-term, high-return institution building activities, coupled with the justice infrastructure and political will to hold those who transgress accountable.

We should combine these efforts with building strong and independent audit and justice systems, including a well-resourced judiciary and an oversight office to field complaints. We also need to create an environment that enables strong and accountable civil society organizations that provide oversight of government. Such strong and independent institutions have a salutary effect on political will as they exert the necessary pressure on politicians, even at the highest levels, to act. Such initiatives take patience and determination though, since building these institutions, systems, and processes may take a decade or more.

My experience in Nigeria showed that a decade spanning three administrations was necessary to build well-functioning technology platforms for managing the country’s finances. The savings in terms of blocked leakages, amounting to over a billion dollars, made it worthwhile.

We found that supporting institution building with openness and transparency of revenue and budgetary data provides a win that can be implemented quickly. The increasing accessibility of the inter net via mobile phones and various analytic apps makes it easier now more than ever to share with citizens information on revenues and expenditures. Publishing monthly data in national newspapers on local, state, and federal government revenues was unprecedented in Nigeria when we started in 2004, but it helped us gain public support for our initiatives going forward. It laid the basis for much more sophisticated analytics on the budget shared widely via the internet today.

Africa needs to focus its anti-corruption fight on long-term, high-return institution building activities, coupled with the justice infrastructure and political will to hold those who transgress accountable. This process should start by making key government statistics open and transparent, enabling citizens to keep on top of important information and build trust in their governments. Only with these pragmatic approaches can the continent record wins against corruption.

Related Content

January 11, 2019

Brookings Institution, Washington DC

10:00 am - 11:30 am EST

Global Economy and Development

Sub-Saharan Africa

Africa Growth Initiative

Amit Jain, Landry Signé

May 29, 2024

Louis Kasekende

May 21, 2024

Mark Schoeman

May 16, 2024

Essay on Corruption for Students and Children

500+ words essay on corruption.

Essay on Corruption – Corruption refers to a form of criminal activity or dishonesty. It refers to an evil act by an individual or a group. Most noteworthy, this act compromises the rights and privileges of others. Furthermore, Corruption primarily includes activities like bribery or embezzlement. However, Corruption can take place in many ways. Most probably, people in positions of authority are susceptible to Corruption. Corruption certainly reflects greedy and selfish behavior.

Methods of Corruption

First of all, Bribery is the most common method of Corruption. Bribery involves the improper use of favours and gifts in exchange for personal gain. Furthermore, the types of favours are diverse. Above all, the favours include money, gifts, company shares, sexual favours, employment , entertainment, and political benefits. Also, personal gain can be – giving preferential treatment and overlooking crime.

Embezzlement refers to the act of withholding assets for the purpose of theft. Furthermore, it takes place by one or more individuals who were entrusted with these assets. Above all, embezzlement is a type of financial fraud.

The graft is a global form of Corruption. Most noteworthy, it refers to the illegal use of a politician’s authority for personal gain. Furthermore, a popular way for the graft is misdirecting public funds for the benefit of politicians .

Extortion is another major method of Corruption. It means to obtain property, money or services illegally. Above all, this obtainment takes place by coercing individuals or organizations. Hence, Extortion is quite similar to blackmail.

Favouritism and nepotism is quite an old form of Corruption still in usage. This refers to a person favouring one’s own relatives and friends to jobs. This is certainly a very unfair practice. This is because many deserving candidates fail to get jobs.

Abuse of discretion is another method of Corruption. Here, a person misuses one’s power and authority. An example can be a judge unjustly dismissing a criminal’s case.

Finally, influence peddling is the last method here. This refers to illegally using one’s influence with the government or other authorized individuals. Furthermore, it takes place in order to obtain preferential treatment or favour.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Ways of Stopping Corruption

One important way of preventing Corruption is to give a better salary in a government job. Many government employees receive pretty low salaries. Therefore, they resort to bribery to meet their expenses. So, government employees should receive higher salaries. Consequently, high salaries would reduce their motivation and resolve to engage in bribery.

Tough laws are very important for stopping Corruption. Above all, strict punishments need to be meted out to guilty individuals. Furthermore, there should be an efficient and quick implementation of strict laws.

Applying cameras in workplaces is an excellent way to prevent corruption. Above all, many individuals would refrain from indulging in Corruption due to fear of being caught. Furthermore, these individuals would have otherwise engaged in Corruption.

The government must make sure to keep inflation low. Due to the rise in prices, many people feel their incomes to be too low. Consequently, this increases Corruption among the masses. Businessmen raise prices to sell their stock of goods at higher prices. Furthermore, the politician supports them due to the benefits they receive.

To sum it up, Corruption is a great evil of society. This evil should be quickly eliminated from society. Corruption is the poison that has penetrated the minds of many individuals these days. Hopefully, with consistent political and social efforts, we can get rid of Corruption.

{ “@context”: “https://schema.org”, “@type”: “FAQPage”, “mainEntity”: [{ “@type”: “Question”, “name”: “What is Bribery?”, “acceptedAnswer”: { “@type”: “Answer”, “text”: “Bribery refers to improper use of favours and gifts in exchange for personal gain.”} }, { “@type”: “Question”, “name”: ” How high salaries help in stopping Corruption?”, “acceptedAnswer”: { “@type”: “Answer”, “text”:”High salaries help in meeting the expenses of individuals. Furthermore, high salaries reduce the motivation and resolve to engage in bribery.”} }] }

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Oxford University Press's Academic Insights for the Thinking World

How education could reduce corruption

Transnational Crime and the 21st Century: Criminal Enterprise, Corruption, and Opportunity

- By Jay Albanese

- July 9 th 2020

We live in an era of widely publicized bad behavior. It’s not clear if there’s more unethical behavior occurring now than in the past, but communications technology allows every corrupt example to be broadcast globally. Why are we not making better progress against unethical conduct and corruption in general?

Morals are the principles of good conduct, widely accepted by all. The study of morality is ethics, and unethical conduct, which underlies all corruption. Corruption undermines the rule of law, creates economic harm, violates human rights, and illicitly protects facilitators and accomplices. Both unethical and corrupt conduct are selfish or self-seeking behavior without regard for the valid claims or human rights of others.

Where do ethics come from? We learn them in the same way we learn all skills, including foreign languages, mechanics, or research methods. People often overestimate the ethicality of their own behavior , failing to recognize underlying, self-serving biases that promote misconduct. We see ourselves as rational, ethical, competent and objective, but lack the ability to see our ethical blind spots that conceal conflicts of interest and unconscious biases in decision-making. Ethical training, education, and reinforcement results in better conduct.

But learning and application of principles in practice is an incremental process, moving from smaller acts to more consistent courses of conduct. Ethics might be the most important skill of all, because it provides the path to appreciate that there is a greater purpose in life than self-interest. People are moral agents, have moral responsibilities, but many have never learned the principles for ethical decision-making.

Global interest in ethical conduct has grown dramatically during the last generation. During the 1990s, the World Bank changed course to address the “cancer of corruption.” This launched the World Bank into a new era in which addressing corruption to ensure funds were not misspent became as important as the development work itself.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development is an intergovernmental organization founded in 1948, which now has 36 member countries, representing nearly two-thirds of gross domestic product globally. Concerned about the tax deductibility of bribes in many countries, the organization developed a convention to criminalize foreign bribery entirely, which entered into force in 1999. The organization is the first binding international convention criminalizing foreign bribery across many nations.

The United Nations Convention against Corruption entered into force in 2005, specifying multiple forms of corruption beyond just bribery, and providing a legal framework for criminalizing and countering it. The UN Convention against Corruption is the only legally binding universal anti-corruption instrument. There are now 187 state parties to the Convention, representing 97% of the UN membership.

Each of these initiatives is significant, and they require participants to enact laws and regulations, engage in enforcement actions, and obtain anti-corruption training. Unfortunately, these initiatives focus on structural reforms: laws, policies, procedures, and technical assistance, to reduce the opportunities for corrupt conduct and enforce anti-corruption provisions. Structural reforms have limitations, however. They reduce opportunities for misconduct, but do not preclude motivated actors from seeking unethical advantage. The result is better institutions, but individual decision-making remains the same.

There are signs of global movement to improve individual ethical decisions, however. The Education for Justice Initiative was developed from the 13th United Nations Congress on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice in 2015. The initiative highlights the importance of education in preventing crime and corruption, and promoting a culture that supports the rule of law.

One of the courses in the Education for Justice Initiative is integrity and ethics. Another is corruption. This effort builds on research documenting the effectiveness of creating principled, ethical decision makers from a young age. The courses, available open access globally , equip participants at different education levels with skills to apply and incorporate these principles in their life and professional decision-making.

People need to be accountable even without a camera looking over their shoulder or constant police surveillance. People must be motivated to act ethically , and establish a moral identity, that supports conduct in the interest of others, rather than selfish or self-seeking behavior.

People need to have better moral integrity is we want to promote ethical conduct. People are under continuous pressure on many fronts: business concerns, government operations, medical access, education, among others. Ethical conduct, resistant to corrupt influences, can be found in unlikely places, but it must begin with greater individual accountability that occurs with higher ethical standards developed through teaching, training, and practice.

Personal and social happiness come from actions that benefit others, rather than exploit or ignore them. People respect other people with high moral standards. There is freedom found in not yielding to our basest desires, and in living openly and cooperatively with others rather than secretively and fraudulently.

It is time to look beyond structural and institutional reforms to reduce opportunities for corrupt conduct, and enforce anti-corruption provisions. It is time to also focus on individual moral education and training to reduce the number of motivated actors seeking unethical advantage.

Jay Albanese is a professor at Virginia Commonwealth University’s Wilder School of Government & Public Affairs. He has also written multiple books on crime, justice, and ethics.

Our Privacy Policy sets out how Oxford University Press handles your personal information, and your rights to object to your personal information being used for marketing to you or being processed as part of our business activities.

We will only use your personal information to register you for OUPblog articles.

Or subscribe to articles in the subject area by email or RSS

Related posts:

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.

Home — Essay Samples — Government & Politics — Corruption — Corruption: Causes, Effects, And Ways To Prevent

Corruption: Causes, Effects, and Ways to Prevent

- Categories: Corruption

About this sample

Words: 1931 |

10 min read

Published: Dec 3, 2020

Words: 1931 | Pages: 4 | 10 min read

Works Cited

- Altbach, P. G., Reisberg, L., & Rumbley, L. E. (2019). Trends in global higher education: Tracking an academic revolution. UNESCO Publishing.

- Gupta, K., & Batra, A. (2015). Corruption and economic growth: A global perspective. International Journal of Development Research, 5(5), 4363-4367.

- Jain, A. K. (2001). Corruption: A review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 15(1), 71-121.

- Klitgaard, R. (1988). Controlling corruption. University of California Press.

- Kwantes, C. T., Boglarsky, C. A., & Pancer, S. M. (2006). The effect of culture on unethical conduct. Social Science Journal, 43(2), 295-300.

- Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission. (2016). Rasuah: Apa itu Rasuah? [Corruption: What is Corruption?]. https://www.sprm.gov.my/ms/pengetahuan-am/rasuah

- Mungiu-Pippidi, A. (2015). The quest for good governance: How societies develop control of corruption. Cambridge University Press.

- 15 effects of corruption. (2019). University of Kent. https://www.kent.ac.uk/integrityoffice/policies-and-procedures/bribery-and-corruption/preventing-corruption/15-effects-of-corruption

- 5 ways to reduce corruption and places where it exists. (2016). The Star Online. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2016/09/12/five-ways-to-reduce-corruption-and-places-where-it-exists/

- Transparency International. (n.d.). Corruption perceptions index.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Government & Politics

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1675 words

5 pages / 2353 words

2.5 pages / 1213 words

1 pages / 430 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Corruption

Stalking is a pervasive and dangerous form of interpersonal violence that can have devastating effects on victims. According to the National Institute of Justice, stalking is defined as a pattern of repeated and unwanted [...]

Corruption in Kenya is a deeply entrenched and complex issue that has long plagued the nation's development and progress. This essay delves into the intricate layers of corruption, its causes, manifestations, and the efforts [...]

Crime fiction has a profound influence on public perceptions of law enforcement, serving as a medium through which readers engage with the intricacies of the criminal justice system. By portraying characters and institutions in [...]

Throughout the play Hamlet, Shakespeare presents a world fraught with moral decay and political manipulation, where characters are consumed by their own desires and ambitions. Corruption, both moral and political, is a pervasive [...]

It is a necessary ethnical appropriate and a primary leader concerning human then financial improvement on someone u . s . . it no longer only strengthens personal honor but additionally shapes the society between who we live. [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

GLOBAL AFFAIRS

M. Seth (*), what are the most effective tools to fight corruption?

On the largest level, there is the creation of effective institutions, such as independent and specialized anti-corruption agencies and audit institutions on the national and international scales; secondly: the strengthening of judicial institutions, and finally: multilateral efforts such as the UN Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC).

These tools can only be effective if accompanied by attitudinal and behavioral shifts. These shifts can be brought through awareness campaigns. International Anti-Corruption Day (9 December), for example, is a great opportunity to make people aware of the scourge of corruption, how deep-rooted it is, and how it upends the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

When we were creating the SDGs, many countries opposed mentioning corruption on the grounds that it would marginalize developing states. But corruption is something present in countries rich and poor. We polled almost 10 million people worldwide on their priorities, and corruption ranked the highest in these peoples’ minds, despite their government representatives’ resistance in the halls of the UNGA.

Attitudinal-behavioral shifts depend largely on education and training. Only through this can we shape competent specialists in the field while fostering the concepts of integrity and personal values to oppose corruption in all forms. In fact, education and training directly fights the scourge in peoples’ minds by changing the general attitude that corruption is too big and deep-rooted to fight.

The most effective training and education programs focus on providing a strong balance between academic and theoretical knowledge on topical issues, and core competencies in areas such as leadership and negotiation skills. To ensure the effectiveness of existing anti-corruption mechanisms through education and training, UNITAR’s Executive Diploma and a master’s program on Anti-Corruption and Diplomacy, jointly implemented with the International Anti-Corruption Academy (IACA), provide this balance.

Dr. Stelzer (**), what are the landmark events in the history of international anti-corruption efforts?

There is a clear division between the period before and after UNCAC. UN anti-corruption action goes back to 1975, when the UNGA adopted the first resolution against corruption, targeting transnational corporations and their intermediaries. The next large steps were all regional: the Inter-American Convention against Corruption in 1996; the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention in 1997; and the EU’s Criminal Law Convention on Corruption in 1999. These all led to the negotiation and adoption of UNTOC (UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime) in 2000.

When I was appointed Permanent Representative of Austria in 2001, the first session of the Crime Commission (Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice) that I chaired, adopted a resolution describing corruption as a structural impediment to sustainable development. This very same Crime Commission helped prepare for the negotiations of what later became the main instrument in the fight against corruption: UNCAC. With 187 parties, UNCAC allowed us to address corruption on the basis of the rule of law, changing the idea that it is too big to fight.

By 2006, the UNCAC implementation progress was still slow. I could not see this initiative, which I had negotiated and signed, wither away. To speed up the process, the head of the Anti-Corruption branch at UNODC and I decided to start training civil servants from developing nations in anti-corruption, then we turned this project into a program, and the program into an institution. Four years later, IACA was formed. IACA’s main achievement is its highly successful academic program, with over 3000 master’s alumni. Our experience has shown that the implementation of UNCAC depends on the strengthening of anti-corruption systems’ resilience by actors, who to a large degree, benefited from our academic programs.

* M. Nikhil Seth is the current Executive Director of UNITAR. ** Dr. Thomas Stelzer is Dean of the International Anti-corruption Academy.

How to make progress in the fight against corruption

Rajni bajpai, bernard myers.

People have been either fighting corruption or have been victims of it for decades. So, should we accept it as a feature of life and carry on or try to fight it where we can? While developing our global report , which was released last week, we tried to delve deeper into how countries are making progress in addressing corruption. The case studies identified show how reform-minded governments and civil society organizations have contributed to reducing corruption in their specific contexts or laid important foundations that can be built on by others.

Virtually every continent, from Asia to Africa, Europe and the Americas, faces perpetrators who bypass or exploit weaknesses in existing laws and regulations to execute schemes, which have been increasing in scale and sophistication. Corruption undermines the credibility of the public sector, erodes trust in governments and their ability to steer a country to achieve high economic growth and shared prosperity. It often weakens the impact of public service delivery, adversely affecting all citizens especially the poor.

The report comes at a time when the world has changed dramatically due to COVID-19. The spotlight is once again on the capacity and integrity of the public sector -- not just in managing the health crisis but also in dealing with the economic and social impacts of the pandemic.

Emergency responses to the COVID-19 pandemic have resulted in huge expenditures by governments, circumventing the standard operating procedures and approval processes. This may create new vulnerabilities and leakages that may only come to light after the initial containment phase has passed. It is at this juncture that the World Bank has undertaken a fresh assessment of the challenges and opportunities faced by governments in tackling corruption in key functions and sectors . We examine the lessons learned from applying selected policy instruments that were designed to mitigate corruption risks, as well as the role and challenges faced by institutions that are intended to promote integrity and accountability.

Drawing lessons from a compendium of case studies from around the world, the report demonstrates that all is not lost and that it is possible to reduce corruption risks even in the most challenging environments. The complex nature of corruption means that technical solutions and added compliance measures will usually be insufficient. A good understanding of the historical origins, social norms, and political culture is often critical to design impactful policies and institutional structures that can support their implementation.

At the same time, one must acknowledge the potential challenges from the forces that benefit from the status quo. There will be resistance owing to the strong inter-play between power, politics, and money. The scope for reformers to make changes will therefore be constrained by the limits of their political influence. It could be a long and frustrating journey with two steps forward and one step backward.

The report presents approaches and policy responses in various country contexts. It reinforces that there is no single formula or magic bullet to address corruption. For example, open government reforms can be effective in promoting an ethos of transparency, inclusiveness, and collaboration and in shifting norms over time by making conditions less conducive to corrupt activity. However, their impact depends on the existence of other enabling factors, such as political will, a free and independent media, a robust civil society, and effective accountability and sanctioning mechanisms.

Case studies featured in the report highlight that multiple factors contribute to the impact of anti-corruption efforts, including political leadership, institutional capacity, incentives, technology, transparency and collaboration. Enhanced collaboration with stakeholders within and outside of government is a critical success factor in overall government effectiveness. Such collaboration involves both the public and private sector, civil society, media, research organizations, think-tanks and citizens. Strengthening the fight against corruption is a collective responsibility!

Editor’s Note: This blog is part of a series that helps unpack our new global report, Enhancing Government Effectiveness and Transparency: The Fight Against Corruption .

- Agriculture and Food

- Competitiveness

- Digital Development

- Disaster Risk Management

- Environment

- Extractive Industries

- Financial Inclusion

- Financial Sector

- Fragility Conflict and Violence

- Inequality and Shared Prosperity

- Infrastructure & Public-Private Partnerships

- Jobs & Development

- Macroeconomics and Fiscal Management

- Regional Integration

- Social Protection

- Social Sustainability and Inclusion

- Urban Development

- Afghanistan

- The World Region

- COVID-19 (coronavirus)

- Disruptive Technologies

- Open Government

Lead Public Sector Specialist

Senior Public Sector Management Specialist

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Get New Issue Alerts

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences

Seven Steps to Control of Corruption: The Road Map

After a comprehensive test of today’s anticorruption toolkit, it seems that the few tools that do work are effective only in contexts where domestic agency exists. Therefore, the time has come to draft a comprehensive road map to inform evidence-based anticorruption efforts. This essay recommends that international donors join domestic civil societies in pursuing a common long-term strategy and action plan to build national public integrity and ethical universalism. In other words, this essay proposes that coordination among donors should be added as a specific precondition for improving governance in the WHO’s Millennium Development Goals. This essay offers a basic tool for diagnosing the rule governing allocation of public resources in a given country, recommends some fact-based change indicators to follow, and outlines a plan to identify the human agency with a vested interest in changing the status quo. In the end, the essay argues that anticorruption interventions must be designed to empower such agency on the basis of a joint strategy to reduce opportunities for and increase constraints on corruption, and recommends that experts exclude entirely the tools that do not work in a given national context.

ALINA MUNGIU-PIPPIDI is Professor of Democracy Studies at the Hertie School of Governance in Berlin. She chairs the European Research Centre for Anti-Corruption and State-Building (ERCAS), where she managed the FP7 research project ANTICORRP. She is the author of The Quest for Good Governance: How Societies Develop Control of Corruption (2015) and A Tale of Two Villages: Coerced Modernization in the East European Countryside (2010).

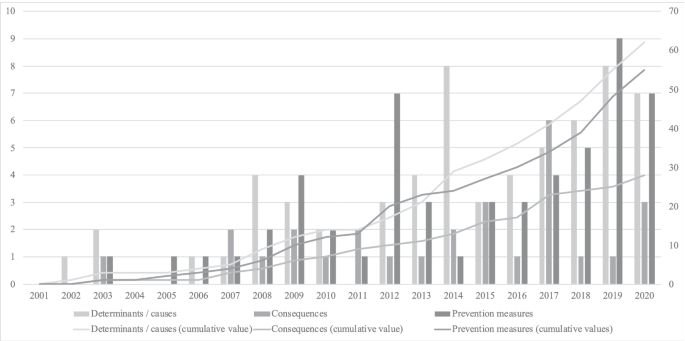

T he last two decades of unprecedented anticorruption activity – including the adoption of an international legal framework, the emergence of an anticorruption civil society, the introduction of governance-related aid conditionality, and the rise of a veritable anticorruption industry – have been marred by stagnation in the evolution of good governance, ratings of which have remained flat for most of the countries in the world.

The World Bank’s 2017 Control of Corruption aggregate rating showed that twenty-two countries progressed significantly in the past twenty years and twenty-five regressed. Of the countries showing progress on corruption, nineteen were rated as either “free” or “partly free” by Freedom House (a democracy watchdog that measures governance via political rights and civil liberties); only seven were judged “not free.” 1 Our governance measures are too new to allow us to look further into the past; still, it seems that governance change has much in common with climate change: it occurs only slowly, and the role that humans play involuntarily seems always to matter more than what they do with intent.

External aid and its attached conditionality are considered an essential component of efforts to enable developing countries to deliver decent public services on the principle of ethical universalism (in which everyone is treated equally and fairly). However, a panel data set (collected from 110 developing countries that received aid from the European Union and its member states between 2002 and 2014) shows little evolution of fair service delivery in countries receiving conditional aid. Bilateral aid from the largest European donors does not have significant impact on governance in recipient countries, while multilateral financial assistance from EU institutions such as the Office of Development Assistance (which provides aid conditional on good governance) produces only a small improvement in the governance indicators of the net recipients. Dedicated aid to good-governance and corruption initiatives within multilateral aid packages has no sizable effect, whether on public-sector functionality or anticorruption. 2 Countries like Georgia, Vanuatu, Rwanda, Macedonia, Bhutan, and Uruguay, which have managed to evolve more than one point on a one-to-ten scale from 2002 to 2014, are outliers. In other words, they evolved disproportionately given the EU aid per capita that they received, while countries that received the most aid (such as Turkey, Egypt, and Ukraine) had rather disappointing results.

So how, if at all, can an external actor such as a donor agency influence the transition of a society from corruption as a governance norm , wherein public resource distribution is systematically biased in favor of authority holders and those connected with them, to corruption as an exception , a state that is largely independent from private interest and that allocates public resources based on ethical universalism? Can such a process be engineered? How do the current anticorruption tools promoted by the international community perform in delivering this result?

Looking at the governance progress indicators outlined above, one might wonder whether efforts to change the quality of government in other countries are doomed from the outset. The incapacity of international donors to help push any country above the threshold of good governance during the past twenty years of the global crusade against corruption seems over- rather than under-explained. For one, corrupt countries are generally run by corrupt people with little interest in killing their own rents, although they may find it convenient to adopt international treaties or domestic legislation that are nominally dedicated to anticorruption efforts. Furthermore, countries in which informal institutions have long been substituted for formal ones have a tradition of surviving untouched by formal legal changes that may be forced upon them. One popular saying from the post-Soviet world expresses the view that “the inadequacy of the laws is corrected by their non-observance.” 3

Explicit attempts of donor countries and international organizations to change governance across borders might appear a novel phenomenon, but are they actually so very different from older endeavors to “modernize” and “civilize” poorer countries and change their domestic institutions to replicate allegedly superior, “universal” ones? Describing similar attempts by the ancient Greeks – and also their rather poor impact – historian Arnaldo Momigliano writes: “The Greeks were seldom in a position to check what natives told them: they did not know the languages. The natives, on the other hand, being bilingual, had a shrewd idea of what the Greeks wanted to hear and spoke accordingly. This reciprocal position did not make for sincerity and real understanding.” 4

Many factors speak against the odds of success of international donors’ efforts to change governance practices, especially government-funded ones. One such factor is the incentives facing donor countries themselves: they want first and foremost to care for national companies investing abroad and their business opportunities; reduce immigration from poor countries; and generate jobs for their development industry. Even if donor countries would prefer that poor countries govern better, reduce corruption, and adopt Western values, they also have to play their cards realistically. Thus, donor countries often end up avoiding the root of the problem: when the choice is between their own economic interests and more idealistic commitments to better governance, the former usually wins out.

T he first question a policy analyst should ask, therefore, is not how to go about altering governance in developing countries, but whether the promotion of good governance and anticorruption is worth doing at all, self-serving reasons aside. I have addressed these questions in greater detail elsewhere; this essay assumes a donor has already made the decision to intervene. 5 The evidence on the basis of which such decisions are made is often poor, but realistically, due to the other policy objectives mentioned above (such as the exigencies of participation in the global economy), international donors will continue to give aid systematically to corrupt countries. As long as one thinks a country is worth granting assistance to, preventing aid money from feeding corruption in the recipient country becomes an obligation to one’s own taxpayers. For the sake of the recipient country, too, ensuring that such money is used to do good, rather than actually to funnel more resources into local informal institutions and predatory elites, seems more of an obligation than a choice.

While our knowledge of how to establish a norm of ethical universalism is still far from sufficient, I will outline a road map toward making corruption the exception rather than the rule in recipient countries. To do so, I draw on one of the largest social-science research projects undertaken by the European Union, ANTICORRP, which was conducted between 2013 and 2017 and was dedicated to systematically assessing the impact of public anticorruption tools and the contexts that enable them. I follow the consequences of the evidence to suggest a methodology for the design of an anticorruption strategy for external donors and their counterparts in domestic civil societies. 6

Many anticorruption policies and programs have been declared successful, but no country has yet achieved control of corruption through the prescriptions attached to international assistance. 7 To proceed, we must also clarify what constitutes “success” in anticorruption reforms. Success can only mean a consolidated dominant norm of ethical universalism and public integrity. Exceptions, in the form of corrupt acts, will always remain, but if they are numerous enough to be the rule, a country cannot be called an achiever. A successful transformation requires both a dominant norm of public integrity (wherein the majority of acts and public officials are noncorrupt) and the sustainability of that norm across at least two or three electoral cycles.

Q uite a few developing countries presently seem to be struggling in a borderline area in which old and new norms confront one another. This is why popular demand for leadership integrity has been loudly proclaimed in headlines from countries such as South Korea, India, Brazil, Bulgaria, and Romania, but substantially better quality of governance has yet to be achieved there. While the solutions for each and every country will ultimately come from the country itself – and not from some universal toolkit – recent research can contribute to a road map for more evidence-based corruption control.

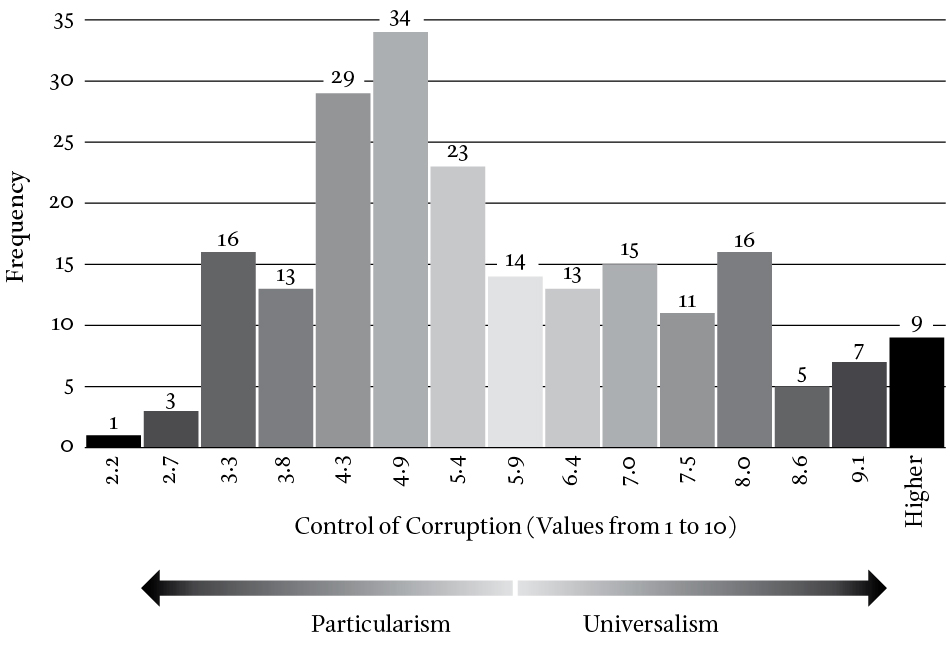

The first step is to understand that with the exception of the developed world, control of corruption has to be built from the ground up, not “restored.” Most anticorruption approaches are built on the concept that public integrity and ethical universalism are already global norms of governance. This is wrong on two counts, and leads to policy failure. First, at the present moment, most countries are more corrupt than noncorrupt. A histogram of corruption control shows that developing countries range between two and six on a one-to-ten scale, with some borderline cases in between (see Figure 1). Countries scoring in the upper third are a minority, so a development agency is more likely than not to be dealing with a situation in which corruption is not only a norm but an institutionalized practice. Development agencies need to understand corruption as a social practice or institution, not just as a sum of individual corrupt acts. Further, presuming that ethical universalism is the default is wrong from a developmental perspective, since even countries in which ethical universalism is the governance norm were not always this way: from sales of offices to class privileges and electoral corruption, the histories of even the cleanest countries show that good governance is the product of evolution, and modernity a long and frequently incomplete endeavor to develop state autonomy in the face of private group interests.

Figure 1 Particularism versus Ethical Universalism: Distribution of Countries on the Control of Corruption Continuum

Source: The World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators, Control of Corruption, http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/#home distribution . Distribution recoded 1–10 (with Denmark 10). The number of countries for each score is noted on each column.

Institutionalized corruption is based on the informal institution of particularism (treating individuals differently according to their status), which is prevalent in collectivistic and status-based societies. Particularism frequently results in patrimonialism (the use of public office for private profit), turning public office into a perpetual source of spoils. 8 Public corruption thrives on power inequality and the incapacity of the weak to prevent the strong from appropriating the state and spoiling public resources. Particularism encompasses a variety of interpersonal and personal-state transaction types, such as clientelism, bribery, patronage, nepotism, and other favoritisms, all of which imply some degree of patrimonialism when an authority-holder is concerned. Particularism not only defines the relations between a government and its subjects, but also between individuals in a society; it explains why advancement in a given society might be based on status or connections with influential people rather than on merit.

The outcome associated with the prevalence of particularism – a regular pattern of preferential distribution of public goods toward those who hold more power – has been termed “limited-access order” by economists Douglass North, John Wallis, and Barry Weingast; “extractive institutions” by economist Daron Acemoglu and political scientist James Robinson; and “patrimonialism” by political scientist Francis Fukuyama. 9 Essentially, though, all these categories overlap and all the authors acknowledge that particularism rather than ethical universalism is closer to the state of nature (or the default social organization), and that its opposite, a norm of open and equal access or public integrity, is by no means guaranteed by political evolution and indeed has only ever been achieved in a few cases thus far. The first countries to achieve good control of corruption – among them Britain, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Prussia – were also the first to modernize and, in Max Weber’s term, to “rationalize.” This implies an evolution from brutal material interests (espoused, for instance, by Spanish conquistadors who appropriated the gold and silver of the New World) to a more rationalistic and capitalistic channeling of economic surplus, underpinned by an ideology of personal austerity and achievement. The market and capitalism, despite their obvious limitations, gradually emerged in these cases as the main ways of allocating resources, replacing the previous system of discretionary allocation by means of more or less organized violence. The past century and a half has seen a multitude of attempts around the world to replicate these few advanced cases of Western modernization. However, a reduction in the arbitrariness and power discretion of rulers, as occurred in the West and some Western Anglo-Saxon colonies, has not taken place in many other countries, regardless of whether said rulers were monopolists or won power through contested elections. Despite adopting most of the formal institutions associated with Western modernity – such as constitutions, political parties, elections, bureaucracies, free markets, and courts – many countries never managed to achieve a similar rationalization of both the state and the broader society. 10 Many modern institutions exist only in form, substituted by informal institutions that are anything but modern. That is why treating corruption as deviation is problematic in developing countries: it leads to investing in norm-enforcing instruments, when the norm-building instruments that are in fact needed are quite different. Strangely enough, developed countries display extraordinary resistance to addressing corruption as a development-related rather than moral problem. This is why our Western anticorruption techniques look much like an invasion of the temperance league in a pub on Friday night: a lot of noise with no consequence. Scholars contribute to the inefficacy of interventions by perpetuating theoretical distinctions that are of poor relevance even in the developed world (such as “bureaucratic versus political” or “grand versus petty” corruption), which inform us only of the opportunities that somebody has to be corrupt. As those opportunities simply vary according to one’s station in life (a minister exhorting an energy company for a contract is simply using his grand station in a perfectly similar way to a petty doctor who required a gift to operate or a policeman requiring a bribe not to give a fine), such distinctions are not helpful or conceptually meaningful. In countries where the practice of particularism is dominant, disentangling political from bureaucratic corruption also does not work, since rulers appoint “bureaucrats” on the basis of personal or party allegiance and the two collude in extracting resources. Even distinguishing victims from perpetrators is not easy in a context of institutionalized corruption. In a developing country, an electricity distribution company, for instance, might be heavily indebted to the state but still provide rents (such as well-paid jobs) to people in government and their cronies and eventually contribute funds to their electoral campaigns. For their part, consumers defend themselves by not paying bills and actually stealing massively from the grid, and controllers take moderate bribes to leave the situation as it is. The result is constant electricity shortages and a situation to which everybody (or nearly everybody) contributes, and which has to be understood and addressed holistically and not artificially separated into types of corruption.

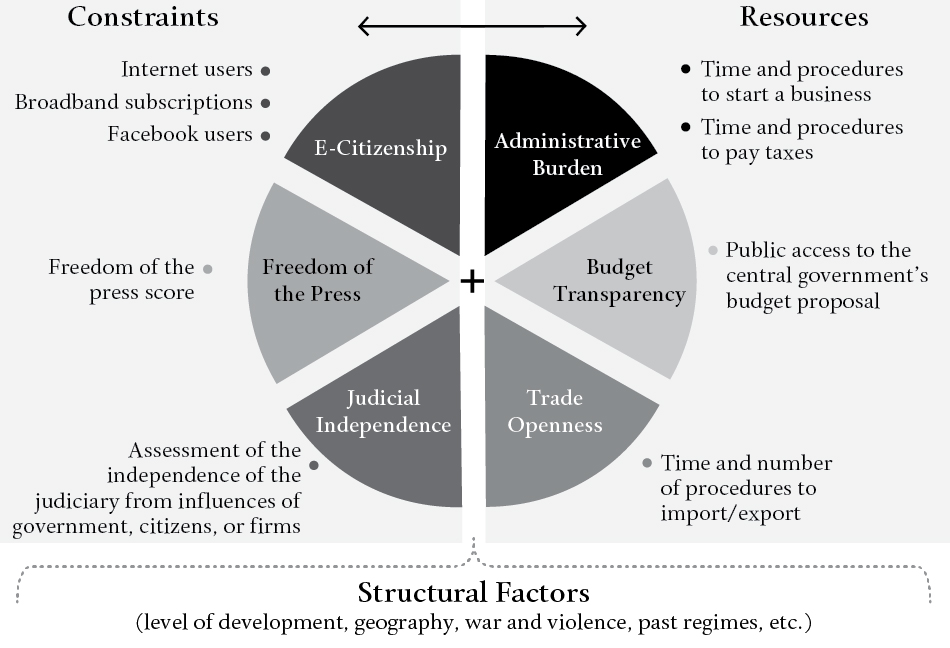

The second step is diagnosing the norm. If we conceive governance as a set of formal rules and informal practices determining who gets which public resources, we can then place any country on a continuum with full particularism at one end and full ethical universalism at the other. There are two main questions that we have to answer. What is the dominant norm (and practice) for social allocation: merit and work, or status and connections to authority? And how does this compare to the formal norm – such as the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), or the country’s own regulation – and to the general degree of modernity in the society? For instance, merit-based advancement in civil service may not work as the default norm, but it may in the broader society, for instance in universities and private businesses. The tools to begin this assessment are the Worldwide Governance Indicator Control of Corruption, an aggregate of all perception scores (Figure 1); and the composite, mostly fact-based Index for Public Integrity that I developed with my team (which is highly correlated with perception indicators). Any available public-opinion poll on governance can complete the picture (one standard measure is the Global Corruption Barometer, which is organized by Transparency International). Simply put, the majority of respondents in countries in the upper tercile of the Control of Corruption indicators feel that no personal ties are needed to access a public service, while those in the lower two-thirds will in all likelihood indicate that personal connections or material inducement are necessary (albeit in different proportions). Within the developed European Union, only in Northern Europe does a majority of citizens believe that the state and markets work impartially. The United States, developed Commonwealth countries, and Japan round out the top tercile. The next set of countries, around six and seven on the scale, already exhibit far more divided public opinion, showing that the two norms coexist and possibly compete. 11 In countries where the norm of particularism is dominant and access is limited, surveys show majorities opining that government only works in the favor of the few; that people are not equal in the eyes of the law; and that connections, not merit, drive success in both the public and private sectors. Bribery often emerges as a substitute for or a complement to a privileged connection; when administration discretion is high, favoritism is the rule of the game, so bribes may be needed to gain access, even for those with some preexisting privilege. A thorough analysis needs to determine whether favoritism is dominant and how material and status-based favoritism relate to one another in order to weigh useful policy answers. Are they complementary, compensatory, or competitive? When the dominant norm is particularistic, collusive practices are widespread, including not only a fusion of interests between appointed and elected office holders and civil servants more generally, but also the capture of law enforcement agencies.

The second step, diagnosis, needs to be completed by fact-based indicators that allow us to trace prevalence and change. Fortunately for the analyst (but unfortunately for everyone else), since corrupt societies are, in Max Weber’s words, status societies , where wealth is only a vehicle to obtain greater status, we do not need Panama-Papers revelations to see corruption. Systematic corrupt practices are noticeable both directly and through their outcomes: lavish houses of poorly paid officials, great fortunes made of public contracts, and the poor quality of public works. Particularism results in privilege to some (favoritism) and discrimination to others, outcomes that can both be measured. 12

Table 1 illustrates how these two contexts – corruption as norm and corruption as exception – differ essentially, and shows that different measures must be taken to define, assess, and respond to corruption in either case. An individual is corrupt when engaging in a corrupt act, regardless of whether he or she is a public or private actor. The dominant analytic framework of the literature on corruption is the principal-agent paradigm, wherein agents (for example government officials) are individuals authorized to act on behalf of a principal (for example a government). To diagnose an organization or a country as “corrupt,” we have to establish that corruption is the norm: in other words, that corrupt transactions are prevalent. When such practices are the exception, the corrupt agent is simply a deviant and can be sanctioned by the principal if identified. When such practices are the norm, corruption occurs on an organized scale, extracting resources disproportionately in favor of the most powerful group. Telling the principal from the agent can be quite impossible in these cases due to generalized collusion (the organization is by privileged status groups, patron-client pyramids, or networks of extortion) and fighting corruption means solving social dilemmas and issues around discretionary use of power. Most people operate by conformity, and conformity always works in favor of the status quo: if ethical universalism is already the norm in a society, conformity helps to enforce public integrity; if favoritism and clientelism are the norm, few people will dissent. The difference between corruption as a rule and corruption as a norm shows in observable, measurable phenomena. In contexts with clearer public-private separation, it is more difficult to discover corrupt acts, requiring whistleblowers or some time for a conflict of interest to unfold (as with revolving doors, through which the official collects benefits from his favor by getting a cushy job later with a private company). In contexts where patrimonialism is widespread, there is no need for whistleblowers: officials grant state contracts to themselves or their families, use their public car and driver to take their mother-in-law shopping, and so forth – all in publicly observable displays (see Table 1).

Table 1 Corruption as Governance Context