Victory for Children’s Rights: Ending Child Marriage in the Philippines

Law supported by the center provides social protection measures to prevent and combat the harmful practice..

In a victory for the health, safety and human rights of children, the Philippines has enacted a new law that seeks to prevent and end child marriage. While President Rodrigo Duterte signed the law on December 10, 2021, it was only publicly released by Malacañang on January 6, 2022.

Although the country’s previous law recognized the legal age of marriage as 18, child marriage has been commonly practiced in certain religions and cultures in the Philippines. The Center for Reproductive Rights supported the development of the new law, which makes child marriage a public offense and adds a series of penalties for violating the law ranging from fines to up to 12 years of imprisonment.

The consequences of child marriage on girls and boys are numerous and far-reaching, directly causing grave harms, including the denial of education, perpetuation of poverty, and increased likelihood and risks of early pregnancy, childbirth, maternal mortality, and sexual violence.

“We’re pleased that the government has finally recognized that child marriage is a fundamental human rights violation harming the health and safety of girls and boys,” said Jihan Jacob, Senior Legal Adviser for Asia at the Center for Reproductive Rights. “This new law represents a significant first step in safeguarding the rights of children in the Philippines.”

The Center’s Asia team has been advocating for stronger laws to strengthen protection and respect the reproductive autonomy for the rights of children, including adolescents, in the Philippines. The team’s advocacy included: submitting reports on the status of adolescents’ reproductive rights to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child ( March 2020 , October 2020 ) ; participating in several consultations on the then-pending bill organized by local organizations and legislators; and sharing comparative research on child marriage including from India , Nepal , and South Asia with policymakers and NGOs to help inform the legislation and the impact on sexual and reproductive health and rights of children.

New Law Adds Strong Penalties for Offenders

The Center’s Submissions to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (Philippines)

June 2020 submission.

The new law, Republic Act No. 11596, or An Act Prohibiting the Practice of Child Marriage and Imposing Penalties for Violations Thereof, contains strong penalties for those who arrange or facilitate, participate, and/or officiate the marriage of a person under 18. Considered a public offense, child marriages will also be considered “void ab initio,” meaning they would not be legal. The law allows for a one-year transitory period during which the penal provisions will be suspended specifically for Muslims and Indigenous peoples.

Penalties include:

- A person who causes, fixes, facilitates, or arranges a child marriage will be subject to fines and/or prison time, with a penalty of up to 12 years in prison if the perpetrator is a parent, step-parent, or guardian of the minor.

- Those who violate the law by performing or officiating the formal rites of a child marriage will also receive fines and/or prison time, and those in positions of public office will be disqualified from office.

October 2020 Submission (Supplementary Report)

Girls Are Especially Harmed by Consequences of Child Marriage

In the Philippines, one in six girls are married before turning 18. Child marriage has a range of negative impacts on the health and lives of young people, especially young girls, and triggers a continuum of human rights violations that continue throughout a person’s life.

For girls in particular:

- Child marriage is often accompanied by early and frequent pregnancy and childbirth, which also results in increased maternal mortality rates.

- For girls, child marriage perpetuates the cycle of engendered poverty, preventing many of them from continuing their education and reducing their employability.

- Girls who marry before the age of 18 are more at risk of being subject to physical, sexual and emotional violence.

New Law Based on a Foundation of Human Rights

“Child, early, and forced marriages limit opportunities across the board, including those around sexual and reproductive decision-making,” added Jacob. “That’s why it’s so essential to have proper, human-rights-based legal frameworks to prevent child marriage and ensure accountability. By enacting this new law, the Filipino government is signaling a legal shift that formally recognizes the rights, dignity, and well-being of minors.”

Under the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, governments must take steps to address and provide redress to rights violations, and the decision in the Philippines is an important move towards ensuring prevention and accountability. It is critical for nations and governments around the world, especially where child marriage is common practice, to acknowledge their obligations under international human rights law to act against child marriage and its resulting human rights violations.

The Center’s Work in the Philippines

More Reform Needed to Effectively End Child Marriage in the Philippines

“Criminalization is just the first step, and we’re hopeful this law will bring about a host of other actions to combat the entrenched cultural biases and harmful stereotypes that have allowed child marriage to occur for so long,” said Jacob.

Government’s efforts to prohibit child marriage must include measures to challenge entrenched social norms and discriminatory gender stereotypes that underlie the practice of child marriage in the country. According to the UN Human Rights Council, “The criminalization of child, early and forced marriage alone is insufficient when introduced without complementary measures and support programmes.”

Under the new law, the Department of Education will develop a sexual education curriculum that will include culturally sensitive modules and discussions around the impacts of child marriage in order to shift social norms and attitudes. In addition, the law directs other government agencies to develop programs and campaigns aimed at raising awareness about the effects of child marriage and protecting victims.

To end child marriage, ongoing programs and investment to support victims and develop a foundation of human rights in the Philippines will be essential to ensuring women and girls can thrive.

In developing the implementing rules and regulations of this law, the Center calls on the government to continue its efforts to respect, protect, and fulfill the rights of children and adolescents in the Philippines by enabling them to make informed and autonomous decisions about their sexuality and reproduction and ensuring access to sexual and reproductive health information and services. The Center also calls on the government to ensure that mechanisms are in place to guarantee implementation of the provisions related to support, property relations, and custody.

Child Marriage in the Philippines

- One out of six (16.5%) Filipina girls are married before they are 18 years old, according to the 2017 Philippine National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS).

- The Philippines ranks tenth in the world for the number of girls who are married or in a union before the age of 18: 808,000, according to the organization Girls Not Brides.

- Girls who marry before the age of 18 are more at risk of being subject to domestic violence. According to the 2017 NDHS, 26.4% of married women aged 15-19 years old reported experiencing physical, sexual or emotional violence.

Tags: Philippines , Child marriage , Adolescent rights

Sign up for email updates.

The most up-to-date news on reproductive rights, delivered straight to you.

Privacy Overview

People want an end to child marriage, but can a law change culture?

- The United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) noted a decline in its prevalence worldwide — from one in four girls from 10 years ago to about one in five today.

- With the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic impacts, the UNICEF fears that 10 million more girls worldwide will end up becoming child brides.

- A separate analysis by Save the Children projected that 2.5 million girls will be at risk of marriage by 2025, which would be the greatest surge in child marriages rate in 25 years.

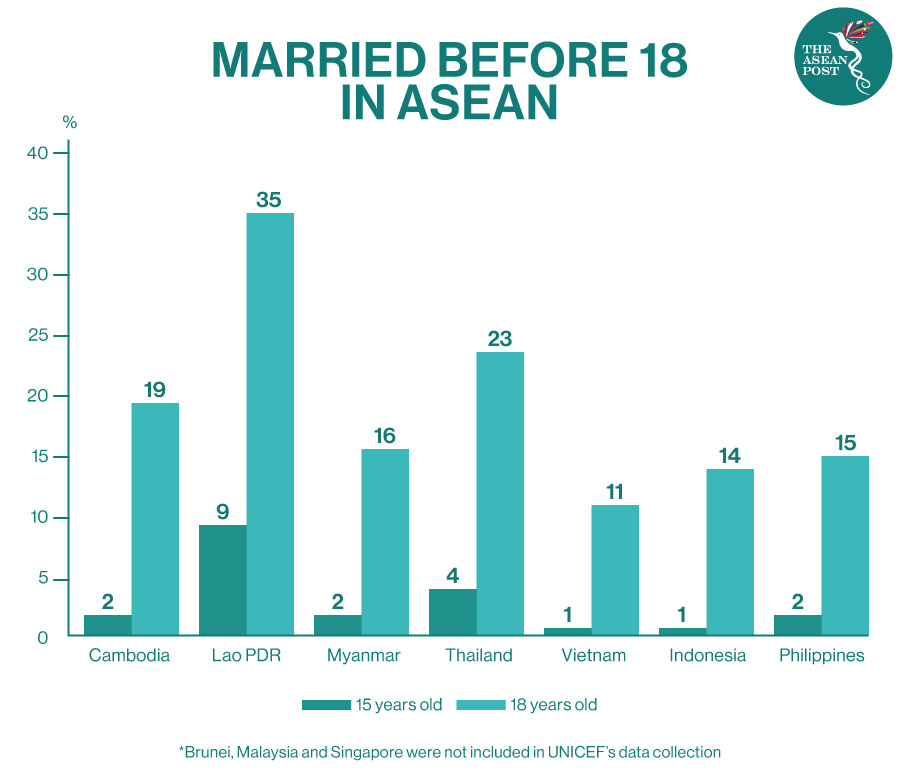

The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) in 2017 noted that 15 percent of women reported getting married by age 18, while two percent said they were married by age 15.

- In November 2020, the Senate unanimously approved on final reading Senate Bill No. 1373, which seeks to outlaw marriages between minors, or between a minor and an adult.

- A counterpart bill was passed by the House of Representatives on third and final reading on Sept. 6. Like the Senate bill, House Bill No. 9943 bans and declares child marriages “void from the start.”

Much has been said about child marriage, and several organizations, both local and international, agree: It is a form of child abuse, an exploitation, a human rights violation that deprives children of several opportunities.

While the United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) noted a decline in its prevalence worldwide — from one in four girls from 10 years ago to about one in five today — the practice of child marriage remains.

In the Philippines, about 808,000 women got married before they turned 18 years old, according to the latest figures of the Girls Not Brides organization, which put the country at the 10th spot in terms of the highest absolute number of women who got married before reaching the age of 18.

In its 2019 Marriage Statistics, the PSA recorded 45 girls and boys under 15 years old who got married during the year.

With the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic impacts, the UNICEF fears that 10 million more girls worldwide will end up becoming child brides. A separate analysis by Save the Children projected that 2.5 million girls will be at risk of marriage by 2025, which would be the biggest surge in the rate of child marriages in 25 years.

Child marriage is driven not only by poverty, trafficking or lack of education, but also by cultural practices passed down through generations.

While the legal age of marriage in the Philippines is 18, existing laws permit marriage before this age among Muslims and indigenous peoples.

Of the Filipino girls and boys who registered their marriage in local civil registry in 2019, 24 were married in Muslim tradition while 20 were married in tribal ceremonies.

The country's Code of Muslim Personal Laws (Presidential Decree No. 1083) allows marriage at the age of 15 for boys, and at the onset of puberty for girls.

While consent is mandatory before the marriage, some children were raised thinking that their elders would decide for them.

Other Muslim families, however, have become more liberal, with members no longer being subjected to early and arranged marriages.

The Bangsamoro Women Commission (BWC), an agency in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), has been vocal against child marriage, especially in pointing out its adverse effects to young girls.

“Child brides have limited opportunities for education and employment, are at an increased risk of domestic violence and other assaults to their physical and mental health, and have little decision-making power within the household, especially when married to older men,” the BWC said in a position paper submitted to the Senate.

The BWC called for the amendment of the PD No. 1083.

In November, 2020, the Senate unanimously approved on final reading Senate Bill No. 1373, which seeks to outlaw marriages between minors, or between a minor and an adult.

Senate Bill No. 1373, which explicitly defines child marriage as “child abuse,” would penalize those who facilitate and arrange such marriage with imprisonment of up to 12 years and a fine of up to P50,000. Parents and guardians will also be stripped of their parental authority over the child.

Those who officiate a child marriage, meanwhile, would be slapped with a jail term and fine of at least P40,000, as well as perpetual disqualification from office.

A counterpart bill was passed by the House of Representatives on third and final reading on Monday, Sept. 6.

Like the Senate bill, House Bill No. 9943 bans and declares child marriages “void from the start.” It proposes to punish persons who facilitate a child marriage with a penalty of prison mayor in its medium period, or a fine of at least P40,000.

If the parent or guardian of the child arranges the marriage, the penalty will likewise be imprisonment or a fine of at least P50,000 and the loss of parental authority.

Individuals who officiate the child marriage will also be slapped with a penalty of prison mayor in its maximum period or a fine of at least P50,000, while public officials will also face perpetual disqualification from office.

‘Historic step’

“This is a historic step toward the criminalization of child marriage, which has trapped several Filipino girls into unwanted and early child-bearing responsibilities,” Gabriela Women's Party Representative Arlene Brosas said.

“Clearly, the fight versus early and forced child marriage is not a fight against a long-time practice, tradition or custom. It is an urgent and necessary fight to end abuse and violence against women and children,” Kabataan Party List Rep. Sarah Elago said. “It's time to challenge and end it.”

Senator Risa Hontiveros, sponsor of the bill in the Senate, expressed her optimism that the bill, if signed into law, will end the practice of child marriage despite it being embedded in cultural practices.

“Just like any other law that involves challenging deep-seated values and cultural practices, implementing this on the ground will involve the cooperation of national government agencies, civil society organizations, and other advocates, and stakeholders. In the bill, they are called duty-bearers,” Hontiveros told the Manila Bulletin.

The chairperson of the Senate Committee on Women, Children, Family Relations and Gender Equality referred to the bill's provisions tasking concerned government agencies to undertake and monitor program against child marriage.

“As always, constant education – learning and unlearning – will be key to transforming these cultural beliefs and practices. We recognize that it may be a difficult process, but nothing worthwhile ever comes easy," Hontiveros said.

Content Search

Philippines

PHILIPPINES: Early marriage puts girls at risk

MANILA, 26 January 2010 (IRIN) - Nurina was 14 when she married Sid, who was 23. "We were close friends. He treated me like a younger sister," Nurina said. "People started to gossip and my family insisted that we be married to avoid tarnishing my reputation."

Seven years later, Nurina is a third-year high-school student and a mother of three.

Early and arranged marriages are common practice in Muslim culture in the Philippines where about 5 percent of the country's 97 million inhabitants are Muslim.

It is estimated that 80 percent of Filipino Muslims live on the southern island of Mindanao. Muslims have a different set of rules governing marriage, divorce, custody of children, among others [ http://www.muslimmindanao.ph/shari%27a/pesonal_laws.pdf ].

"Under Article 16 of the Muslim Code, the minimum marrying age is 15 for both males and females. However, upon petition of a male guardian, the Shari'a District Court may order the solemnization of the marriage of a female who has attained puberty though she is younger than 15, but not below 12," Claire Padilla, executive director of EnGendeRights, a legal NGO working for the repeal of this provision, which it considers discriminatory, told IRIN.

No accurate information

There is no accurate data of how many Muslim girls in Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) marry before the age of 18.

Yasmin Bursan-Lao, founder and executive director of Nisa Ul-Haqq Fi Bangsamoro (Women for Justice in the Bangsamoro), an NGO advocating for women's rights in the context of Islamic culture, attributes this to several factors.

"Marriage registration is not a common practice, especially in far-flung areas. Many do not find the registration of marriages, births and deaths relevant unless they seek employment. The process and costs entailed further discourage registration," says Bursan-Lao, quoting findings in a research paper, Determinants and Impact of Early Marriage on Moro Women, by Nisa in March 2009.

A total of 593 respondents from five provinces in ARMM, who were younger than 18 at marriage, were surveyed. The study shows that 83 percent were 15-17, while 17 percent were between nine and 14 years old. The ages of the respondents' husbands ranged from 11-59 years, with 57 percent between 17 and 21 at the time of marriage.

"Early marriage is not just a result of cultural practices. The Muslim Code allows it. Challenging the practice of early and arranged marriage needs evidence-based argumentation which we hope this research will address," Bursan-Lao concluded.

Reasons for getting married

Religious beliefs ranked highest, with women saying early marriage was in accordance with their religion. This was followed by cultural reasons such as keeping family honour, and economic factors.

A small proportion said they married for political reasons like settling or preventing family disputes, or forging political alliances, while others still report being "forced" into the arranged marriage by their parents.

Maternal mortality risks

According to the 2008 National Health and Demographic Survey, [see: http://www.un.org.ph/response/clusters/nutrition/keyDocs/2008%20National%20Demographic%20and%20Health%20Survey.pdf ], the maternal mortality rate in ARMM is twice as high as the national average of 162 per 100,000 live births.

ARMM has a high unmet need for family planning, with the lowest contraceptive prevalence rate for modern methods at 9.9 percent and traditional methods at 5.2 percent.

On average, six out of 10 births take place at home under the supervision of a traditional birth attendant, but in ARMM, that figure is nine out of 10 births, the survey states.

Elizabeth Samama, a provincial health officer in ARMM, said having children at a young age poses serious health risks. "The body of an adolescent girl is not fully developed. Her uterus and other reproductive organs are not mature or properly equipped to support the development of another human life. The ideal age for conceiving is between the age of 20 and 35," she said.

Armed conflict

The Department of Social Welfare and Development estimates that 126,225 individuals are still living in evacuation centres since the outbreak of renewed fighting between the government and the Muslim separatist group, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, in August 2008.

"The combination of so much idle time in a close space like an evacuation centre makes the youth vulnerable to exploring relationships," says Laisa Alamia, a programme manager for Nisa Ul-Haqq Fi. Pre-marital relations are forbidden in Muslim culture and to protect the girl's chastity, she is forced into marriage.

But Alamia also noted another factor. "In the evacuation centre, each family is entitled only to one food coupon for basic relief goods. Girls and boys are married off by their parents to create new families and qualify for more food coupons," she said.

Related Content

Dswd dromic terminal report on the tornado incident in brgy. bawang, san remigio, antique, 01 june 2024, 6pm, dswd, dole team up to mitigate impacts of climate change, dswd dromic report #89 on the effects of el niño as of 01 june 2024, 6am, dswd dromic terminal report on the armed conflict in lanao del norte, 01 june 2024, 6am.

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

Perspectives and realities of child marriage

While many support the passage of the anti-child marriage law or Republic Act No. 11596 that protects children, others push for an exemption, citing inconsistencies with the Muslim code of personal laws and cultural norms, customs, and traditions.

In the Islamic perspective, the age of discernment is the onset of puberty. It can be as early as nine years old for girls and around 15 or 16 for boys. They can get married by these ages to prevent zina or illicit sexual relations. However, we cannot be blind to other societal illnesses, like pedophilia and gender-based violence. Surely, the protection of the vulnerable is weightier than the few who wish to marry early and are psychologically, physically, and financially capable?

To those seeking reconsideration of this law, try to imagine your nine-year-old daughter telling you she is in love with a boy in school and wants to get married. Try to imagine that a man five times her age who is eligible under our personal laws and customs wants to marry her. Try to imagine her with a child of her own. If you had a choice, would you consent to marry off your daughter, who is still in elementary? Is marriage at this point the best protection for her, more than education, parental guidance, or spiritual maturity?

I am a young woman who got married at 26 years old. Others consider this the right age, but I still had to forego career and education opportunities even with my privileged position. Caring for the family became my priority. I am thankful for empowering experiences in my youth: I finished graduate school, did well in my professional career, and had the opportunity to travel the world. I am secure knowing I have skills and capacities in case of abandonment, divorce, or getting widowed. I wish the same for my daughter. To make the most of her potential before marriage when life becomes different.

I am still learning my rights as a wife within the rules of Islam. I cannot help then but think of women and children who are unaware of theirs, especially girls most vulnerable to gender-based violence in early marriages.

Meanwhile, I am a young male teacher, and I have seen firsthand how early marriages affect girls more than boys. I have 11- to 14-year-old students who are already married. The females had to stop school to care for their children while married young boys could continue and enjoy the support of their families. Unfortunately, too, we hear many stories of forced child marriages that consider girls as properties without agency.

Islam emphasizes the protection of women—it is imposed on men to lower their gaze when women are around, education is obligatory for both sexes, and women have the right to keep their inheritance and assets even after marriage. However, I recognize that women’s lived realities are starkly different from the ideal.

RA 11596 seeks to protect children who cannot speak for themselves. While there is wisdom in allowing marriages to curb premarital sex, child marriage is not an isolated case that exempts specific cultures and identities because it affects education, health, poverty, and vulnerability to violence.

In a 2013 young adult fertility survey, 60 percent said early marriage or early pregnancy affected their ability to finish school, which has inter-generational effects. A person who graduated high school has four times more capability to increase their income than those who finish only elementary. Likewise, the capability to earn more increases sixfold for those who finish college than those who do not.

Both of us are not Islamic scholars, but we know enough to say that not all Shariah laws are immutable. While our faith, values, and objectives as Muslims are universal and transcend time, laws allow flexibility to adapt to current contexts and necessities. Jurists can amend laws to ensure the welfare of our women. In Saudi Arabia, marriages below the age of 18 are already prohibited. If our collective goal as Muslims is to protect women and children, is it not time to consider the anti-child marriage law?

We reflected on this matter as both a woman and a man, bringing our perspectives as wife, mother, daughter, and brother and son. The debate will certainly continue, as it should. What is crucial now is that legislators and implementers protect spaces for dialogue that allow those directly affected to participate, raise issues, present solutions, and work with others to implement measures responsive to their everyday realities, especially for young women and girls.

Allahu’alam. Allah knows best.

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Nina Bahjin-Imlan is a wife, mother, and advocate for peace and women’s empowerment. Rod Matucan is a community youth leader and teacher in the Bangsamoro.

Fearless views on the news

Disclaimer: Comments do not represent the views of INQUIRER.net. We reserve the right to exclude comments which are inconsistent with our editorial standards. FULL DISCLAIMER

© copyright 1997-2024 inquirer.net | all rights reserved.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. By continuing, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. To find out more, please click this link.

Crisis upon crisis: teen pregnancies, child marriages amid the pandemic

Teen pregnancies and child marriages have been pressing concerns in the Philippines but the pandemic and the lockdown intended to curb it aggravated the problems, officials and rights advocates say.

“Even before COVID-19, from Cagayan Valley to Lanao del Sur, we saw how child marriage increases in areas where there is deep poverty, plenty of disasters and other forms of crisis,” said Lot Felizco, country director of development and humanitarian organization Oxfam Philippines.

The pandemic is “the reason for the increase of gender-based violence, especially in evacuation camps and temporary shelters,” she said in at the #GirlDefenders Speak Out to End Child Marriage Zoomlidarity Rally on March 5.

She did not elaborate but recurring natural calamities and armed conflicts in the country have forced families to evacuate from their communities, with women and girls bearing the brunt of these difficult conditions.

Felizco added that “social and gender norms fuel the practice of child marriage.”

The Philippines is the 12th country worldwide to have the most number of child marriages with around 726,000, as listed by the UNFPA in their 2020 policy brief. It also claimed that one out of six teenage girls are already married in the country.

In another forum a week earlier, Commission on Population and Development (PopCom) Executive Director Jose Perez III said that the problem of teenage pregnancy is “likely to continue and even exceed the current record” because of the absence of health and family planning services while under quarantine.

“Unintended pregnancies are of great concern since these are associated with a range of adverse consequences not only for the mother but for her child as well, especially when the mother is still a child herself,” he said during a webinar on Feb. 26 called “Amplified: Young Voices for Adolescent Health.”

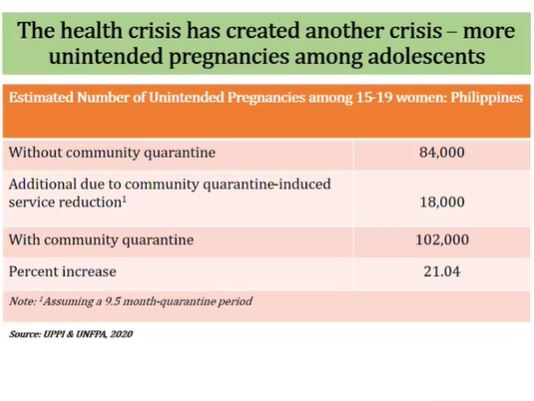

In 2020 alone, more than 102,000 teens aged 15 and above gave birth, including an additional 18,000 due to almost 10 months of community quarantine amid the pandemic. This compares to the estimate without community quarantine of 84,000, according to a study by the University of the Philippines Population Institute and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

Rom Dongeto, director of the Philippine Legislators’ Committee on Population and Development (PLCPD) said in last month’s webinar that the cases of unintended pregnancies can be “attributed to early sexual initiation and unprotected sex yet many are definitely victims of statutory rape and child sexual abuse.”

Worsening over time

The issue of teen pregnancies has been a pressing problem for years, prompting the National Economic Development Authority (NEDA) to declare it as a national social emergency in 2019.

PopCom’s Perez said that in 2002, most of those who engaged in premarital sex were males aged 15 to 19. “However, in 2013, we saw the number of women rise with the number of men engaging in premarital sex before 18.”

But 2019 showed a drastic change in terms of teenage pregnancies. Births among 10-14 year-old mothers increased to seven births a day in 2019, compared to three births/day in 2011, said Perez, citing numbers from the Philippines Statistics Authority (PSA).

The Social Weather Stations (SWS) reported that 59% or almost 6 out of 10 Filipinos, polled in November 2020, believe that teenage pregnancy is the most important problem of women today.

Apart from teen mothers, fathers aged below 20 have also steadily increased since 2010.

Mai Quiray of PopCom said one of their programs on teen pregnancy also focuses on communicating with teen fathers about their responsibility and their adolescent reproductive and sexual health. Especially with the rise of these cases, they should not be left out.

Women usually take one year to get pregnant and give birth, but men can impregnate more in a year, she said.

“It is important for teen fathers to also get this message because their roles grow bigger in terms of youth pregnancies,” said Perez.

Better communication between teenagers and parents may decrease the likelihood of risky sexual activity, according to Perez, but PopCom data shows only 10% of Filipino parents discuss sexuality with their adolescent children.

Adolescent mothers

The Popcom director said early marriage compromises a minor’s opportunities.” More and more minors who have given birth had repeat pregnancies,” he said. “And based on my observation, if you have given birth to your second child as a minor, most likely, you will not be able to finish your studies and return to school.

Apart from halting education, teen mothers face more risks.

Mothers aged 10 to 19 face higher risks of diseases such as eclampsia, puerperal endometritis and systemic infections than women aged 20 to 24 years, according to the World Health Organization, while babies of adolescent mothers also face higher risks of low birth weight, preterm delivery and severe neonatal conditions.

Adolescent and young adult women also experience physical, sexual or emotional violence from their husbands or partners during pregnancy.

Policies to prevent rise of adolescent pregnancy, child marriages

Bills have been filed in both Houses in Congress to address the rise in adolescent pregnancies.

Sen. Risa Hontiveros, who chairs the Committee on Women, filed Senate Bill (SB) 1334 or the Prevention of Adolescent Pregnancy Act of 2020.

The bill, which has been pending on 2nd reading since Feb. 12, 2020, aims to create a national program specifically on the prevention of adolescent pregnancy, and proposes comprehensive sexual education to be integrated in all school levels.

For the House of Representatives, Malou Acosta-Alba who sits as the Chair on Committee on Women and Gender Equality, was among the filed House Bill (HB) 6528 or the Prevention of Adolescent Pregnancy Act of 2020.

Mariquit Melgar, a staff member of Acosta-Alba, said “While we have several laws on reproductive health and healthcare, such as the Universal healthcare Act, there is no law that specifically addresses problems surrounding adolescent pregnancy,” highlighting the bill’s importance.

In crafting the bills concerning teen pregnancy, Rena Dona of the UNFPA said at least 1200 members of the youth were surveyed to see their top concerns in relation to adolescent pregnancies to “ensure young people’s concerns are addressed.”

The top concern was the lack of correct information regarding sexual and reproductive health, which 82% of the respondents listed as the first priority, followed by the lack of guidance from parents and guardians which accounted for 75 percent and lastly, the lack of access to adolescent sexual and reproductive health services, such as contraceptive commodities, which amount to 65 percent.

“To address these concerns, young people expressed that the government needs to mobilize an intensive and targeted age-appropriate gender-responsive culturally appropriate advocacy campaign and awareness raising, for both online and offline platforms,” said Dona.

In an effort to ban child marriages, Dep. speaker Bernadette Herrera-Dy, also the first legislator who sought to ban child marriages in the 17th congress, filed 1486 or An Act Protecting Children by Prohibiting and Declaring Child Marriage as Illegal.

The bill aims to authorize the DSWD to formulate a comprehensive program and services to ensure support of child marriage prohibition. It was recently submitted on March 2, 2021, to the Committee on Justice since it was filed on July 4, 2019.

In the Senate, Hontiveros filed on Feb. 26, 2020, a similar bill with SB No. 1373 which proibits and declares child marriage as illegal.

PopCom has also said that the fate of thousands of these adolescent girls hangs in the balance with the stalling of the bills.

Teen pregnancies are a problem to all, “especially the Filipino youth,” said PLCPD’s Dongeto.

These bills should be enacted into law “because child marriages continue….They are not isolated cases,” he said.

Read other interesting stories:

Click thumbnails to read related articles.

Bontoc woman is a human rights icon

VERA FILES FACT CHECK: Video claiming WHO ‘reversed’ its advice on lockdowns FALSE

VERA FILES FACT CHECK: FAKE infog claims NCR, 4 provinces under GCQ with heightened restrictions

What The F?! Podcast Special: ‘You’re not alone’ – Stories of women journalists in Asia (PART 2)

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Reddit

- Save to your Google bookmark

- Save to Pocket

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Impact of Early Marriage Practices: A Study of Two Indigenous Communities in South-Central Mindanao (Tboli and Blaan) From a Human and Child Rights Perspective

Related Papers

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science

Noemi Cabaddu

Chona Sarmiento

The study used a combination of the Rapid Field Appraisal Approach and a cross sectional survey applying the snow ball sampling to identify case respondents. The scenarios of the children/youth involvement in smoking, drugs and alcohol explored very sensitive areas which were difficult to capture in the actual documentation. The forms of child abuse identified and the research locations were carefully chosen by the researchers from the prevalent high health risk areas as reported by the City Health Office, Region 9. The investigations focused on situations of the children and youth respondents from ages ten to nineteen years old to contribute a deeper understanding of the situation on the challenges on how “to save these children and youth”. More importantly, it is hope that studies like this will guide policy makers in the region, community leaders and practitioners to tackle the necessary interventions from the problems studied. The central subject of the study was to investigate the high health risk faced by children and youth hooked to smoking, substance abuse, alcohol, STD and teen age pregnancy in two impoverished rural and urban barangays in Zamboanga City. This study seeks to generate information relevant to the children and youth in high health risk and to establish the factors that best explain why and how children enter and take part in this line of activity. Keywords: RFA, health risk, smoking and substance abuse

Ed Quitoriano

Ritma Fitri

Child marriage rates in Indonesia continue to increase and cause for concern. Data from UNICEF, the World Children's Country, child marriage in Indonesia is ranked 7th in the world and the second highest of all member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Besides affecting the human development index (HDI), child marriage also affects the poverty depth index which can threaten the failure of sustainable development goals (SDGs). Child marriages have an impact on low levels of education because children leave school, have limited access to economic opportunities, are vulnerable to violence, mental health and an increased risk of maternal and infant mortality. Several studies conducted by social science experts at several universities in Indonesia state that the factors that cause an increase in child marriage in Indonesia are mainly caused by economic factors and the stereotype that marrying children at a young age can help ease the burden on parents. A...

Family Process

Judy Hutchings

Psychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary Journal

Psychology and Education , Jhohnniel P. Celeste

The study aims to assess the strategies the selected internal and external stakeholders employed to address the emerging cases of teenage pregnancy in the Alabat Island Division of Quezon. Utilizing a mixed-method research design, findings indicated that comprehensive sex education and other strategies were widely regarded as an ineffective intervention for addressing teenage pregnancies with always one-on-one face-to-face sessions with teenagers. Additionally, the study reveals active engagement of stakeholders in Alabat, Quezon, with follow-ups and visits to encourage teenage pregnancy awareness. The research findings show a concerning increase in adolescent pregnancies in Alabat, Quezon. This indicates that the lack of parental guidance and support is a significant problem in implementing strategies as solutions; they do home visitations and follow-ups. Furthermore, the study has shown promising results of comprehensive counseling and other strategies in lowering the rates of teenage pregnancies, as internal and external stakeholders perceived. Moreover, the study suggests that the stakeholders must prioritize comprehensive sex education, foster a supportive school culture, engage parents, establish support systems, collaborate with stakeholders, and monitor program effectiveness. These actions will create a safe and inclusive environment that promotes responsible decision-making and empowers students to make informed choices regarding their reproductive health. Implications of the study were discussed.

Getrude Vongai Chiparange

Harafik Harafik

Indonesia is the second highest of early marriage incidence for girls in Southeast Asia, right behind Cambodia and is ranked 37 in the world (UNDESA, 2011). The early marriage especially for girls has multiple drivers and are inseparable one from another. Poverty has been claimed to be a main trigger for parents to marry their daughters at early age as marrying their daughters will likely to relief family economic burden. Likewise, a growing of literature on child marriage has suggested that it tends to perpetuate poverty in broader understanding as in many cases girls who marry at early age very often than not have to leave schools which lead to lose opportunity to gain skills and knowledge which is essential endowment for escaping poverty. Tradition, and religious norms and gender inequality also play critical part in causing early marriage among girls and this tradition mostly persist in rural areas in which rate of poverty is still prevalent and unavailability of basic infrastructure.

Clarence Faye D E L E M O S Bobis

Parentification or adolescents' adoption of adult family roles by providing instrumental or emotional support for their family can have a huge impact to an adolescent in terms of his/her social/emotional adjustment and perception of marriage. Many studies have discussed about parentification and the adolescents’ social-emotional adjustment, but few studies were about parentification and perception of marriage. This study aimed to know if there is a significant difference between perception of marriage and the different types of social/emotional adjustment among female adolescents in the concept of the Filipino family whose score ranged from average to high on the Parentification Questionnaire. The researchers utilized a quantitative research design and purposive sampling to gather data. Researchers used Weinberger Adjustment Inventory Scale to measure the parentified adolescents’ type of social-emotional adjustment; Marital Attitude Scale which has 3 separate scales (IMS, GAMS and AMS) to measure the parentified adolescents’ perception of marriage. The data gathered are statistically analyzed using One-Way ANOVA and Tukey Test. The results have shown significant difference between the social/emotional adjustment of the parentified female adolescents’ and their perception of marriage in regards with their negative attitudes towards marriage and in one aspect of marriage which is the trust.

RELATED PAPERS

International Journal of Computational Intelligence Systems

ho pham huy anh

Advances in Business Strategy and Competitive Advantage

Ilene Wasserman

UDIK BUDI WIBOWO

Revista Científica General José María Córdova

David Barrero-Barrero

Journal of Food Science

Patricia Díaz-Caneja

Ultrasonics

Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

LUIS GONZALO MARTINEZ PEÑA

BMC Health Services Research

space&FORM

Journal of Marriage and Family

Katrina McDonald , Elizabeth Armstrong

Research Assistant

Agha H Amin

Fertility and Sterility

Abdulrahim Rouzi

Physical Review Letters

Prince Eric Perez

Arab World English Journal

Sucharat Rimkeeratikul

Al-Hikmah: Jurnal Agama dan Ilmu Pengetahuan

Mira Syafitri

Fabio Scarano

Abdalsattar K A R E E M Hashim

Filip Van Hauwermeiren

US Memorial Day 2024 Letter to President Vladimir Putin

Tim Nicholson

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- High contrast

- OUR REPRESENTATIVE

- WORK FOR UNICEF

- NATIONAL AMBASSADORS

- PRESS CENTRE

Search UNICEF

Passage of “prohibition of child marriage law” is a major milestone for child rights, statement attributable to ms. oyunsaikhan dendevnorov, unicef philippines representative.

7 January 2022 - Amid the exacerbation of child rights issues due to the COVID-19 pandemic, compounded by the onslaught caused by Typhoon Odette (Rai), UNICEF Philippines celebrates a major milestone in child rights – the passage of Republic Act No. 11596 or the “Prohibition of Child Marriage Law.”

According to the 2017 Philippine National Demographic and Health Survey, 1 in 6 Filipino girls are married before they are 18 years old or the legal age of majority. The phenomenon of child marriage has been seen to have been practiced in indigenous and Muslim communities in the country. Globally, the Philippines ranks 12 th in the absolute number of child marriages. While these communities have been trying to address this issue through community-based programmes, passing a legislation strengthens the legal framework and protection for our young children and underscores the commitment of the Government as a State Party to fully implement the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The profound effects of the pandemic, including school closures, economic shocks, and interruption of vital health services, have had direct impacts on teenage pregnancy and subsequently, child marriage. With the passing and enactment of this new law, another layer of protection, which will also yield lasting benefits for children, especially girls, is secured.

Child marriage is a human rights violation that can result in a lifetime of suffering not just for young girls but for their children as well. Girls who marry before turning 18 are less likely to remain in school and more likely to experience domestic violence and abuse. Compared to women in their 20s, they are also more likely to die due to complications in pregnancy and childbirth. If they survive pregnancy and childbirth, the likelihood of their infants to be stillborn or die in the first month of life is quite high.

We laud the Philippine Government for passing this very important law. Together with the Child Rights Network and all other child rights organizations and advocates in the country, we at UNICEF will remain committed in ensuring the stringent enactment of this new law and supporting the Philippine Government, especially the key actors in the implementation of this Act, as we continue our work towards the complete eradication of child marriage and all forms of violence against children in the Philippines.

UNICEF will be steadfast in safeguarding other actions including social protection measures, equitable access to education, uninterrupted health services, and empowerment of children and young people.

Media contacts

About unicef.

UNICEF promotes the rights and wellbeing of every child, in everything we do. Together with our partners, we work in 190 countries and territories to translate that commitment into practical action, focusing special effort on reaching the most vulnerable and excluded children, to the benefit of all children, everywhere.

For more information about UNICEF and its work for children in the Philippines, visit www.unicef.ph .

Follow UNICEF Philippines on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram .

Related topics

More to explore.

- Geopolitics

- Environment

Ending Child Marriage In The Philippines

This file photo shows teenage girls huddling as they look at an improvised lantern in Legazpi City, Albay province, southeast of Manila. (AFP Photo)

Every year, 12 million girls are married before the age of 18. That is 23 girls every minute.

In some Southeast Asia countries, child marriages and teenage pregnancies continue to rise. ASEAN member states Indonesia , Lao PDR and Vietnam, among others have long practiced early unions. Girls Not Brides, an international organisation on a mission to end child marriage worldwide, states that 14 percent of girls are married before 18 in Indonesia, and one percent are married before their 15th birthday. Whereas in Lao and Vietnam, 35 percent and 11 percent of girls are married before they turn 18, respectively.

Some of the main reasons that fuel and sustain the practice of child marriage include poverty, lack of education, cultural practices and security.

When a girl is forced to marry as a child, she faces immediate and lifelong consequences. Her odds of finishing school decrease while her odds of experiencing domestic violence rise, notes the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). There is also a higher risk of perpetuating intergenerational cycles of poverty.

Back in March 2019, ASEAN together with UNICEF, United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA) and humanitarian organisation Plan International, organised a regional forum to raise awareness on child, early and forced marriage (CEFM) in the region. The forum served as the beginning of an action-oriented dialogue among multiple stakeholders, aimed at accelerating efforts to eliminate child marriage and to make Southeast Asia a CEFM-free region.

A few months following the forum, Indonesia announced that it had revised its marriage law to lift the minimum age at which women can marry by three years to 19. It was a move welcomed by campaigners as a step towards curbing child marriage in the archipelago.

Recently, the Philippines’ Senate passed on third and final reading a bill that criminalises child marriage in the country. According to local media, in a unanimous vote, senators approved Senate Bill No. 1373 or the “Girls not Brides Act” which prohibits marriage between minors (persons below 18 years old) or between a minor and an adult.

In addition, those who cause, fix, arrange or officiate a child marriage shall also receive punishment.

“The issue of child, early and forced marriages is one that is largely invisible to us here in Metro Manila, but it is a tragic reality for scores of young girls who are forced by economic circumstances and cultural expectations to shelve their own dreams, begin families they are not ready for, and raise children even when their own childhoods have not yet ended,” said Senator Risa Hontiveros.

“Today we give our girls a chance to dream, a chance to define their future according to their own terms. We defend their right to declare when they are ready to begin their families. We tell them their health matters to us, their education matters to us. We give them a fighting shot,” she added.

According to UNICEF, the Philippines has the 12th highest absolute number of child brides in the world at 726,000. An estimated 15 percent of Filipino girls are married before they turn 18, while two percent are married before the age of 15.

Even before the recent and much celebrated move by the Philippines, the ASEAN member state had already committed to eliminating CEFM by 2030 in line with target 5.3 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The Philippines ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1990 which sets a minimum age of 18 for marriage. The archipelago has also committed to the ASEAN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women and Violence against Children in 2013, which acknowledges the importance of strengthening the region’s efforts to protect children from all forms of violence, including early marriage. Other than that, they also co-sponsored the 2014 United Nations (UN) General Assembly resolution on CEFM, among other efforts to combat the issue.

An analysis by humanitarian organisation for children, Save the Children, revealed that a further 2.5 million girls are at risk of marriage by 2025 because of the COVID-19 pandemic – the greatest surge in child marriage rates in 25 years.

Save the Children also states that as many as one million more girls are at risk of becoming pregnant this year alone – with childbirth the leading cause of death among 15- to 19-year olds.

"When you have any crisis like a conflict, disaster or pandemic – rates of child marriage go up," said Erica Hall from international children charity, World Vision.

Back in July, Iori Kato, UNFPA’s representative to the Philippines warned that the country may see a spike in child marriage amid the coronavirus crisis.

“In the Philippines, even before the outbreak of COVID-19, one out of six Filipino girls married before 18,” said Kato.

“And because the effects of this pandemic and quarantine measures are disrupting those efforts to end child marriage, we may actually see even a further increase in child marriage,” he added.

Hopefully, with the approval of the proposed Girls Not Brides Act in the Philippines, that would not happen in the country.

Related Articles:

Poverty And Underage Marriage In Indonesia

Pandemic Causing Child Marriage To Spike

Tangshan And Xuzhou: China's Treatment Of Women

Myanmar's suu kyi: prisoner of generals, philippines ends china talks for scs exploration, ukraine war an ‘alarm for humanity’: china’s xi, china to tout its governance model at brics summit, wrist-worn trackers detect covid before symptoms.

Philippines

Prevalence rates, child marriage by 15, child marriage by 18, other key stats.

16.5% of girls in Philippines are married before their 18th birthday and 2.2% are married before the age of 15.

2.9% of boys in Philippines are married before the age of 18.

We have 2 members in Philippines

Content featuring philippines, the responsibility to prevent and respond to sexual and gender based violence in disasters and crises.

- 17 July 2018

Looking at sexual and gender-based violence following natural disasters in Asia, this research found child marriage as one of the most prevalent forms of violence.

Child, early and forced marriage legislation in 37 Asia-Pacific countries

- 1 September 2016

This report reviews child marriage laws in 37 countries in the Asia-Pacific region, providing country profiles for each of these countries.

Ending sex discrimination in the law

- 1 January 2015

Looks at sex discriminatory laws around the world, including minimum age of marriage, domestic violence & rape laws, and provides contact information for those who wish to act

Universal Periodic Review: successful examples of child rights advocacy

- 1 January 2014

This toolkit provides valuable insights for child rights advocates wanting to engage in the Universal Periodic Review process and more generally in child rights monitoring and advocacy.

Data sources

We use cookies to give you a better online experience and for marketing purposes.

Read the Girls Not Brides' privacy policy

Allow all cookies Essential cookies only

- Subscribe Now

FAST FACTS: What causes child marriage in BARMM?

Already have Rappler+? Sign in to listen to groundbreaking journalism.

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

CHILD BRIDE. This file photo shows a 14-year-old girl who was forced to marry a man she barely knew.

Bobby Lagsa/Rappler

MANILA, Philippines – In January 2022, the ban on child marriages finally became law in the Philippines, but this does not necessarily mean the practice will be eradicated right away. Cultural and socio-economic conditions prevail that make these possible.

In the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), adolescent girls have had to undergo the now-illegal practice of child marriage because of family, community, and environmental pressures, a new study found.

Plan International, the Women’s Refugee Commission, and Transforming Fragilities said in their study, released Wednesday, March 30, that child marriage in BARMM is rooted in gender and socio-economic equality, limiting young girls’ freedoms to make their own life decisions.

The study found that child marriage comes from a number of cultural factors, such as a prevailing patriarchal system, as well as unaddressed socio-economic problems. These include:

- Conflict or disaster-related displacement

- Limited decision-making power among adolescent girls

- Self-sacrifice and sense of duty

- Controlling adolescent sexuality to protect family honor

- Poverty and lack of access to stable income-generating activities

- Lack of access to quality education

- Differing interpretations of Islamic beliefs around child marriage

- Enabling legal environment

On January 6, President Rodrigo Duterte signed the law declaring a total ban on child marriage in the Philippines . Lawmakers and advocates fought a long battle for the ban to protect Muslim women and girls from the practice.

Under Presidential Decree No. 1083 or the Code of Muslim Personal Laws, Filipino Muslims were allowed to get married as minors, while non-Muslims in the country are permitted by the Family Code to marry only after reaching the age of 18. Section 13 of the new law states that decrees that are inconsistent with it are repealed or modified.

Cultural drivers

According to the study, many adolescent girls were deprived of decision-making powers, including whom to marry. Gender norms perpetuated by parents, and subsequently their husbands, governed girls’ bodies, behavior, sexuality, socio-economic health, and access to resources and opportunities. Some parents arranged marriages without consulting their daughters.

This is done despite Islam’s prohibition of forced marriages. But some young girls do not openly resist their families’ decisions – and silence is read as consent.

Too young to marry

At the same time, girls rationalized the fear or hesitation they had towards marriage because they had a “sense of self-sacrifice and duty” towards their parents and family. Some girls were inclined to the agreement because they believed it would help relieve financial burden on their parents, or “regain family honor.”

Marriages were used to control girls’ sexual behavior, and as a response to teenage dating, pregnancy, elopement, rape, and to save girls’ families from shame. Some girls were married off to dispel rumors about their sexuality – but were later still bullied by their peers.

“For example, girls who are sexual violence survivors were found to be forced to marry their perpetrators. In their stories, many girls expressed discontent regarding their marriages, but ultimately rationalized them as a fair punishment, or as a means to regain family honor,” the study read.

The study found that married and unmarried young women were not familiar with existing national laws or guidelines that discouraged the practice. This led them to believe child marriage was common and acceptable, even if it meant marrying a perpetrator of sexual violence.

Muslim families were also found to be interpreting Islamic beliefs differently when it came to the acceptance of child marriage.

“To note, Islamic law permits marriage by maturity rather than age…. Data showed contradictory community perceptions; among some community members child marriage was desired, while among others it was stigmatized,” the study read.

Socio-economic, political drivers

Data from the study confirmed the intrinsic link between poverty and education that leads to child marriage.

“Poverty alone does not cause child marriage, but rather a lack of resources to fulfill educational needs that is caused by a lack of income-generating options leads to school dropouts, because caregivers cannot afford to pay school fees and/or other educational materials,” the study read.

“Without an education, girls are left with few alternatives, except child marriage for financial security,” it added.

In some areas, child marriage was found to be commodified or done out of convenience amid displacement. In Lanao del Sur, marrying off one’s daughter was used as a form of compensation or appreciation for shelter from host families. Marriages were also done as a way to form a family that would receive its own packages from humanitarian assistance in Lanao del Sur and Maguindanao.

Some provinces in Lanao del Sur also used child marriages as a way to consolidate and expand political and resource power.

The study revealed that child marriages ultimately led to early pregnancies, cycles of poverty, dropouts from school, adverse effects on health and well-being, and stigma and social isolation of married girls.

Eradicating the practice

The child marriage ban was a long-awaited victory for young women and girls forced into the practice. But the law may turn out as ineffective if it is not implemented.

The study recommended an urgent, coordinated, and multi-stakeholder community-led approach to address the drivers of child marriage. Government actors, such as the BARMM’s ministries of education, health, and social services and development, must address gaps in programs and services for married and pregnant adolescent girls.

The new law provides for one of the study’s recommendations, which is to compel these government actors, including youth councils (Sangguniang Kabataan), to ensure and promote greater access to education in areas where child marriage is common.

Parenting interventions would also serve useful in preventing the practice. Curriculum topics could include child protection, positive parents, children’s rights, and parenting in Islamic households. The study also suggested disseminating positive sexual and reproductive health rights messaging and information at home.

Humanitarian and development programs must also be designed in a way that young girls have greater access to safe spaces to learn, interact, and play with their peers. However, there is still limited evidence behind safe spaces leading to the mitigation of gender-based violence.

In areas with threats of conflict and violence, current peace-building programs by government, civil society organizations, and nongovernmental organizations would allow more space for health and social services.

Read Plan International’s full study here . – Rappler.com

Add a comment

Please abide by Rappler's commenting guidelines .

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.

How does this make you feel?

Related Topics

Michelle Abad

Recommended stories, {{ item.sitename }}, {{ item.title }}, barmm officials ask congress to create province for 8 new towns.

Thousands still displaced as Marawi siege reparations fall short

IP groups form political party ahead of BARMM’s first parliamentary elections

Cardinal Quevedo condemns Cotabato chapel grenade attack

2 wounded after thrown grenade explodes in Cotabato City chapel

Children's rights

Gov’t agencies, advocates urge senate to fast-track anti-teen pregnancy bill.

Chess serves as support for Argentina’s vulnerable, detained children

EXPLAINER: What is intersex?

Angeles City files child abuse complaint vs parents of boy mimicking flagellation

[Free to disagree] Patiño and Tabar: Dim, deviant or despicable?

![early marriage in the philippines essay [Free to disagree] Patiño and Tabar: Dim, deviant or despicable?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/TL-dim-deviant-or-despicable-mar-26-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=221px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.60; Jan-Dec 2023

- PMC10123900

Exploring the Consequences of Early Marriage: A Conventional Content Analysis

Javad yoosefi lebni.

1 Health Education and Health Promotion, School of Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Mahnaz Solhi

2 Department of Education and Health Promotion, School of Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Farbod Ebadi Fard Azar

Farideh khalajabadi farahani.

3 Department of Population & Health, National Population Studies & Comprehensive Management Institute, Tehran, Iran

Seyed Fahim Irandoost

4 Department of Community Medicine, School of Medicine,Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran

Associated Data

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-inq-10.1177_00469580231159963 for Exploring the Consequences of Early Marriage: A Conventional Content Analysis by Javad Yoosefi Lebni, Mahnaz Solhi, Farbod Ebadi Fard Azar, Farideh Khalajabadi Farahani and Seyed Fahim Irandoost in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Early marriage is one of the most important social issues for young women and can have many consequences. The present study aimed to explore the consequences of early marriage among Kurdish women in western Iran who were married under the age of 18. This qualitative study was conducted with the approach of conventional content analysis. The data were collected through semi-structured interviews with 30 women selected by purposeful sampling. Data analysis was performed using Graneheim and Lundman’s method. A total of 389 codes, 12 subcategories, 4 sub-categories, and 2 main categories were extracted from the data analysis. Negative consequences of early marriage include: 1—physical and psychological problems (high-risk pregnancy and childbirth, physical illnesses, depression, and emotional distress); 2—family problems (dissatisfaction with married life, experience of having lots of responsibility, lack of independence in family life); 3—social problems (risky social behaviors, lack of access to social and health services, social isolation, lack of access to a job, and educational opportunities); and 4—positive consequences, including receiving intra-family support, improving living conditions, and opportunities for progress and empowerment. It is possible to reduce problems and challenges after early marriage by increasing the awareness and knowledge of young women about contraceptives and providing appropriate social and health facilities, and services during pregnancy. Providing the necessary training and psychological counseling for them and their husbands on how to deal with personal problems and marital life will be effective to a great extent.

- What do we already know about this topic?

- Early marriage is associated with the following: non-use of contraceptives before the first delivery; high fertility (3 or more births); repeated pregnancy in less than three months; unwanted pregnancies; more domestic violence, including various forms of physical, emotional, and sexual violence; depression; the risk of getting sexually transmitted diseases; and preterm birth.

- How does your research contribute to the field?

- Few qualitative studies have been conducted on the consequences of early marriage in Iran and around the world. Therefore, the current research can reveal the hidden layers of this issue, and its results can be provided to site developers and planners to take action to improve the health of children who experience early marriage.

- What are your research’s implications for theory, practice, or policy?

- Early marriage brings many negative consequences for women, such as physical and mental problems and family and social challenges. Of course, in some cases, it can bring positive consequences, such as receiving support within the family, improving living conditions, and the opportunity for advancement and empowerment.

Introduction

In the last 3 decades, many national and international organizations have paid extensive attention to children’s rights. 1 One of the violations of children’s rights is early marriage, 2 which refers to marriage under the age of 18, 3 and it can have devastating consequences for both genders. However, it is regarded as an example of gender discrimination because it is more harmful to girls. 4 It is estimated that almost 5 times as many girls as boys are married under the age of 18, and about 250 million of them marry before the age of 13. 3 The rate of early marriage varies from country to country; Africa and Western Europe have the highest and lowest rates, respectively. 5 In Iran, the minimum legal age for the marriage of girls is 13, but men can marry girls under 13 with a judge’s order. 6 The prevalence of early marriage in rural areas of Iran is reported at 19.6 and in urban areas at 13.7. 7 In the first 9 months of 2016 in Iran, 13 820 cases of marriage under the age of 18 were registered. But the actual figures for early marriage appear to be higher than the official figures because many cases of early marriage occur within families and are not officially registered. 8

Early marriage in other countries occurs for reasons such as cultural beliefs, 9 social norms, 10 poverty, 11 control over girls, 12 and religion. 13 Low literacy and lack of awareness among girls and their parents, lack of decision-making power and authority of girls, gaining social prestige and support, and poverty have been identified as the most important causes of early marriage of girls in Iran. 6 , 14

There are many devastating consequences of early marriage. In a study, early marriage was significantly associated with non-use of contraceptives before the first delivery, high fertility (3 or more births), and repeated pregnancies—women becoming pregnant again within 3 months of giving birth. 15 A study on behavioral control and spousal violence toward women in Pakistan found that women who were married as children experienced more behavioral control than adult women. They also experienced more domestic violence, including various forms of physical and emotional violence. 16 Irani and Roudsari, in 2019, also showed in a review study that early marriage in girls was associated with death during childbirth, physical and sexual violence, depression, the risk of getting sexually transmitted diseases, and preterm birth. 17 A qualitative study conducted by Mardi et al in 2018 in Ardabil, Iran, showed that adolescent girls confronted experiences such as misunderstanding of sexual relations, death of dreams, and decreased independence. Also, the results of their study showed that adolescent girls could not understand life opportunities, and health care providers and policymakers needed to make adolescents aware of the negative consequences of early marriage and prevent them from doing it. 18

In Iran, few qualitative studies have been conducted on the consequences of early marriage, and none of the studies have been conducted in Kurdish regions. Since the study population is different in terms of ethnicity, language, and culture from other parts of Iran, and according to the experiences of the first author of the article, who has been conducting research on women in this area for many years, it seemed that a separate study should qualitatively examine the consequences of early marriage in this region. Therefore, the present study aimed to explore the consequences of early marriage among Kurdish women in western Iran.

Design and Participants

This qualitative study employed the conventional content analysis method. 19 Qualitative content analysis is an appropriate and coherent method for textual data analysis that is used with the aim of a better understanding of the phenomenon. In conventional content analysis, categories and subcategories are obtained directly from interviews or group discussions. 20 - 22

The study population consisted of married women who had married under the age of 18. The following criteria were used to select participants: having been married under the age of 18, being under 25 at the time of the study, residing in one of the 2 Kurdish provinces of Kermanshah or Kurdistan at the time of marriage, and willingness to participate in research.

Kermanshah and Kurdistan provinces are located in the west of Iran. These 2 provinces have many cultural and social commonalities. The people of both provinces are Kurds and speak Kurdish. Also, economically, both provinces are almost on the same level.

The purposeful sampling method was used in this study. The researchers proceeded to the study area after obtaining the ethics approval (IR.IUMS.REC.1397.1225) from the Iran University of Medical Sciences. Study participants were included based on inclusion criteria after collecting addresses from the selected health centers. Before beginning the interview sessions, the researchers explained the goals and objectives to the participants and written consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Collection

The information needed for the study was obtained through semi-structured face-to-face interviews. All interviews were conducted by a woman with a master’s degree in women’s studies who was familiar with qualitative research and semi-structured interviews. No men were present during the interviews so that the participants could quickly share their experiences with the researcher. All the interviews were recorded using a recorder, and note-taking was done during the interviews. The researcher initially chose a quiet place for the interview in coordination with the participant so that the interviews were conducted without the presence of another person, and the researcher tried to elicit the required information from the participants by creating a sincere atmosphere. First, she asked general questions. Then, after creating an empathetic atmosphere, she asked the more sensitive questions. At the beginning of each interview, in addition to stating the goals and necessity of the study, provided a brief description of their scientific resume. Then the interview started with a few questions about demographic characteristics, such as age and education, and continued with the main questions ( Table 1 ). The authors designed the interview questions and sent them to 3 participants as a test to ensure they could achieve the research objectives with the designed questions, which were approved. It then ended with short complementary questions to get the depth and breadth of the answers. The place and time of the interview were determined by the participants, mostly in places such as their homes, libraries, cultural places, parks, and other public places. The duration of the interviews varied for each participant, but the average time was 68 minutes. The interview was conducted in Kurdish and translated into Persian by the article’s first author. After data analysis, an expert translated all parts of the article into English. The first author assisted the translator, who explained any unclear parts to the translator so they could be translated better.

Interview Guide.

The researchers stopped the interviews when saturation occurred, and data saturation occurs when no new data are obtained from the interviews. 23 Conceptual saturation occurred in interview 23 when the codes were repetitive, but the researchers conducted 7 more interviews to gain greater confidence and prevent false saturation, reaching 30 people. Finally, data saturation was achieved after 30 interviews. Data collection and analysis began in July 2019 and ended on April 13, 2020.

Data Analysis

The data analysis process was performed using the 5 steps suggested by Graneheim and Lundman. 19 In the first step, the corresponding author and first author of the article listened to all the interviews that were recorded, once individually and then together. Later, they typed all the interviews in Microsoft Word. In the second step, the texts of the interviews were read several times to gain an understanding of the whole text. In the third step, the texts were read word for word, and thus, the codes were retrieved. The open codes were then categorized under more general headings. In the fourth step, the codes were categorized into categories based on their similarities and differences, and how they were related was determined. In the last step, the data were placed in the main categories, which were more abstract and more conceptual ( Table 2 ). The analysis of the data was done manually, and all the authors of the article monitored the process and expressed their views in separate meetings.

An Example of Data Analysis.

Ethical Considerations

The researchers went to the health centers of the surveyed cities and villages after receiving the ethics approval (IR.IUMS.REC.1397.1225) from the Iran University of Medical Sciences. The health centers were asked to identify women who met the study’s eligibility criteria and collect their contact information. When contacting the women, they were asked to determine the time and place of the interview. Then the researchers visited the people’s homes and invited them to participate by stating the research’s goals and necessity.

Trustworthiness

To confirm the validity and consistency of the study, the researchers used the Lincoln and Guba criteria. 24 To gain credibility in this study, the participants were selected based on who had the most diversity in terms of socioeconomic characteristics. Then the findings were given to 8 participants, and they expressed their views on the matching of the findings to their experiences of early marriage. In addition, because the researchers were natives of the study areas and had experience conducting qualitative research on Kurdish women, they could easily communicate with participants and obtain good information from them. To gain confirmability, the researchers sent the data analysis process to 4 people who were familiar with the principles of qualitative research and had experience conducting research on early marriage, and later, their supplementary feedback was used. To gain dependability, all the authors of the article participated in the process of analysis and coding, and the opinions of all members of the research team were used. Also, in order to obtain transferability, in addition to presenting many direct quotes from the participants, a detailed description of the whole research process was provided to the readers in this article ( Supplemental File 1 ). The results of the study were also given to 4 women who had similar characteristics to the participants in the project but did not participate in the study. They were asked to state whether they agreed with the research outcome and whether they had similar experiences with the participants in this study. Then they accepted the results of the study.

The study ended with the participation of 30 women, whose demographic characteristics are shown in Table 3 . After analyzing the data, 389 open codes, 14 subcategories, 4 categories, and 2 main categories were extracted, which are described below ( Table 4 ).

Demographic Characteristics of Participants.

Main Categories, Categories, Subcategories, and Codes Extracted From the Analysis of Interviews.

Negative Consequences of Early Marriage

Early marriage posed many challenges for women at various individual, family, and social levels, leading most participants to regret the marriage.

1—Physical and psychological problems