- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 4. The Introduction

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

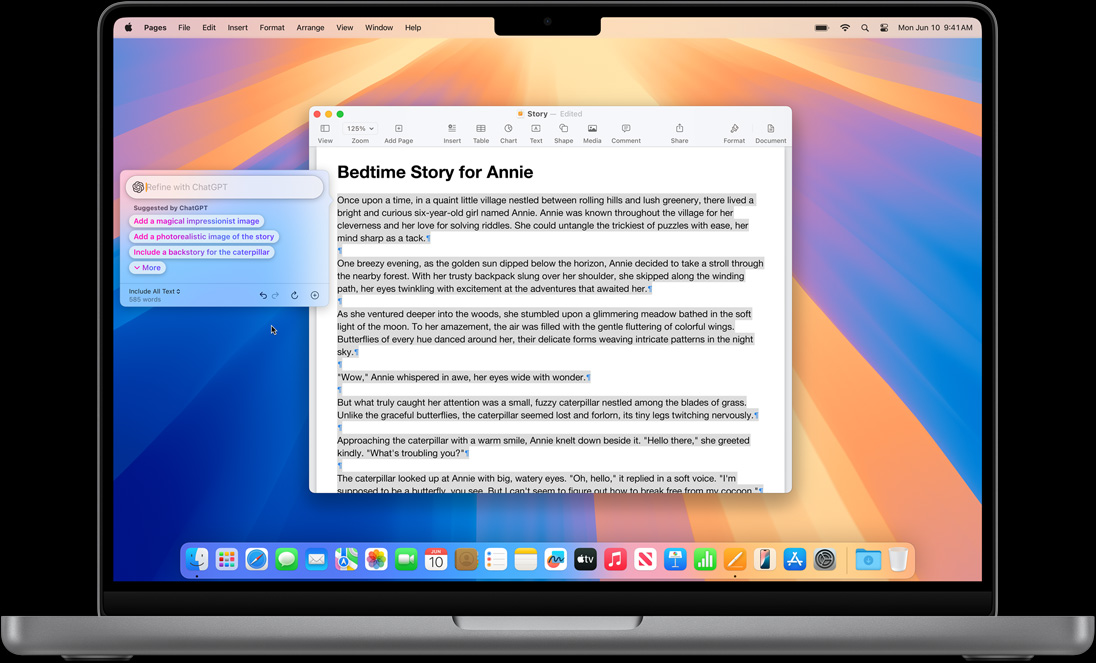

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The introduction leads the reader from a general subject area to a particular topic of inquiry. It establishes the scope, context, and significance of the research being conducted by summarizing current understanding and background information about the topic, stating the purpose of the work in the form of the research problem supported by a hypothesis or a set of questions, explaining briefly the methodological approach used to examine the research problem, highlighting the potential outcomes your study can reveal, and outlining the remaining structure and organization of the paper.

Key Elements of the Research Proposal. Prepared under the direction of the Superintendent and by the 2010 Curriculum Design and Writing Team. Baltimore County Public Schools.

Importance of a Good Introduction

Think of the introduction as a mental road map that must answer for the reader these four questions:

- What was I studying?

- Why was this topic important to investigate?

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study?

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding?

According to Reyes, there are three overarching goals of a good introduction: 1) ensure that you summarize prior studies about the topic in a manner that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem; 2) explain how your study specifically addresses gaps in the literature, insufficient consideration of the topic, or other deficiency in the literature; and, 3) note the broader theoretical, empirical, and/or policy contributions and implications of your research.

A well-written introduction is important because, quite simply, you never get a second chance to make a good first impression. The opening paragraphs of your paper will provide your readers with their initial impressions about the logic of your argument, your writing style, the overall quality of your research, and, ultimately, the validity of your findings and conclusions. A vague, disorganized, or error-filled introduction will create a negative impression, whereas, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will lead your readers to think highly of your analytical skills, your writing style, and your research approach. All introductions should conclude with a brief paragraph that describes the organization of the rest of the paper.

Hirano, Eliana. “Research Article Introductions in English for Specific Purposes: A Comparison between Brazilian, Portuguese, and English.” English for Specific Purposes 28 (October 2009): 240-250; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide. Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Structure and Approach

The introduction is the broad beginning of the paper that answers three important questions for the reader:

- What is this?

- Why should I read it?

- What do you want me to think about / consider doing / react to?

Think of the structure of the introduction as an inverted triangle of information that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem. Organize the information so as to present the more general aspects of the topic early in the introduction, then narrow your analysis to more specific topical information that provides context, finally arriving at your research problem and the rationale for studying it [often written as a series of key questions to be addressed or framed as a hypothesis or set of assumptions to be tested] and, whenever possible, a description of the potential outcomes your study can reveal.

These are general phases associated with writing an introduction: 1. Establish an area to research by:

- Highlighting the importance of the topic, and/or

- Making general statements about the topic, and/or

- Presenting an overview on current research on the subject.

2. Identify a research niche by:

- Opposing an existing assumption, and/or

- Revealing a gap in existing research, and/or

- Formulating a research question or problem, and/or

- Continuing a disciplinary tradition.

3. Place your research within the research niche by:

- Stating the intent of your study,

- Outlining the key characteristics of your study,

- Describing important results, and

- Giving a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

NOTE: It is often useful to review the introduction late in the writing process. This is appropriate because outcomes are unknown until you've completed the study. After you complete writing the body of the paper, go back and review introductory descriptions of the structure of the paper, the method of data gathering, the reporting and analysis of results, and the conclusion. Reviewing and, if necessary, rewriting the introduction ensures that it correctly matches the overall structure of your final paper.

II. Delimitations of the Study

Delimitations refer to those characteristics that limit the scope and define the conceptual boundaries of your research . This is determined by the conscious exclusionary and inclusionary decisions you make about how to investigate the research problem. In other words, not only should you tell the reader what it is you are studying and why, but you must also acknowledge why you rejected alternative approaches that could have been used to examine the topic.

Obviously, the first limiting step was the choice of research problem itself. However, implicit are other, related problems that could have been chosen but were rejected. These should be noted in the conclusion of your introduction. For example, a delimitating statement could read, "Although many factors can be understood to impact the likelihood young people will vote, this study will focus on socioeconomic factors related to the need to work full-time while in school." The point is not to document every possible delimiting factor, but to highlight why previously researched issues related to the topic were not addressed.

Examples of delimitating choices would be:

- The key aims and objectives of your study,

- The research questions that you address,

- The variables of interest [i.e., the various factors and features of the phenomenon being studied],

- The method(s) of investigation,

- The time period your study covers, and

- Any relevant alternative theoretical frameworks that could have been adopted.

Review each of these decisions. Not only do you clearly establish what you intend to accomplish in your research, but you should also include a declaration of what the study does not intend to cover. In the latter case, your exclusionary decisions should be based upon criteria understood as, "not interesting"; "not directly relevant"; “too problematic because..."; "not feasible," and the like. Make this reasoning explicit!

NOTE: Delimitations refer to the initial choices made about the broader, overall design of your study and should not be confused with documenting the limitations of your study discovered after the research has been completed.

ANOTHER NOTE: Do not view delimitating statements as admitting to an inherent failing or shortcoming in your research. They are an accepted element of academic writing intended to keep the reader focused on the research problem by explicitly defining the conceptual boundaries and scope of your study. It addresses any critical questions in the reader's mind of, "Why the hell didn't the author examine this?"

III. The Narrative Flow

Issues to keep in mind that will help the narrative flow in your introduction :

- Your introduction should clearly identify the subject area of interest . A simple strategy to follow is to use key words from your title in the first few sentences of the introduction. This will help focus the introduction on the topic at the appropriate level and ensures that you get to the subject matter quickly without losing focus, or discussing information that is too general.

- Establish context by providing a brief and balanced review of the pertinent published literature that is available on the subject. The key is to summarize for the reader what is known about the specific research problem before you did your analysis. This part of your introduction should not represent a comprehensive literature review--that comes next. It consists of a general review of the important, foundational research literature [with citations] that establishes a foundation for understanding key elements of the research problem. See the drop-down menu under this tab for " Background Information " regarding types of contexts.

- Clearly state the hypothesis that you investigated . When you are first learning to write in this format it is okay, and actually preferable, to use a past statement like, "The purpose of this study was to...." or "We investigated three possible mechanisms to explain the...."

- Why did you choose this kind of research study or design? Provide a clear statement of the rationale for your approach to the problem studied. This will usually follow your statement of purpose in the last paragraph of the introduction.

IV. Engaging the Reader

A research problem in the social sciences can come across as dry and uninteresting to anyone unfamiliar with the topic . Therefore, one of the goals of your introduction is to make readers want to read your paper. Here are several strategies you can use to grab the reader's attention:

- Open with a compelling story . Almost all research problems in the social sciences, no matter how obscure or esoteric , are really about the lives of people. Telling a story that humanizes an issue can help illuminate the significance of the problem and help the reader empathize with those affected by the condition being studied.

- Include a strong quotation or a vivid, perhaps unexpected, anecdote . During your review of the literature, make note of any quotes or anecdotes that grab your attention because they can used in your introduction to highlight the research problem in a captivating way.

- Pose a provocative or thought-provoking question . Your research problem should be framed by a set of questions to be addressed or hypotheses to be tested. However, a provocative question can be presented in the beginning of your introduction that challenges an existing assumption or compels the reader to consider an alternative viewpoint that helps establish the significance of your study.

- Describe a puzzling scenario or incongruity . This involves highlighting an interesting quandary concerning the research problem or describing contradictory findings from prior studies about a topic. Posing what is essentially an unresolved intellectual riddle about the problem can engage the reader's interest in the study.

- Cite a stirring example or case study that illustrates why the research problem is important . Draw upon the findings of others to demonstrate the significance of the problem and to describe how your study builds upon or offers alternatives ways of investigating this prior research.

NOTE: It is important that you choose only one of the suggested strategies for engaging your readers. This avoids giving an impression that your paper is more flash than substance and does not distract from the substance of your study.

Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Introduction. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Introductions. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Introductions, Body Paragraphs, and Conclusions for an Argument Paper. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Resources for Writers: Introduction Strategies. Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Sharpling, Gerald. Writing an Introduction. Centre for Applied Linguistics, University of Warwick; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Swales, John and Christine B. Feak. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Skills and Tasks . 2nd edition. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2004 ; Writing Your Introduction. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University.

Writing Tip

Avoid the "Dictionary" Introduction

Giving the dictionary definition of words related to the research problem may appear appropriate because it is important to define specific terminology that readers may be unfamiliar with. However, anyone can look a word up in the dictionary and a general dictionary is not a particularly authoritative source because it doesn't take into account the context of your topic and doesn't offer particularly detailed information. Also, placed in the context of a particular discipline, a term or concept may have a different meaning than what is found in a general dictionary. If you feel that you must seek out an authoritative definition, use a subject specific dictionary or encyclopedia [e.g., if you are a sociology student, search for dictionaries of sociology]. A good database for obtaining definitive definitions of concepts or terms is Credo Reference .

Saba, Robert. The College Research Paper. Florida International University; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

Another Writing Tip

When Do I Begin?

A common question asked at the start of any paper is, "Where should I begin?" An equally important question to ask yourself is, "When do I begin?" Research problems in the social sciences rarely rest in isolation from history. Therefore, it is important to lay a foundation for understanding the historical context underpinning the research problem. However, this information should be brief and succinct and begin at a point in time that illustrates the study's overall importance. For example, a study that investigates coffee cultivation and export in West Africa as a key stimulus for local economic growth needs to describe the beginning of exporting coffee in the region and establishing why economic growth is important. You do not need to give a long historical explanation about coffee exports in Africa. If a research problem requires a substantial exploration of the historical context, do this in the literature review section. In your introduction, make note of this as part of the "roadmap" [see below] that you use to describe the organization of your paper.

Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Always End with a Roadmap

The final paragraph or sentences of your introduction should forecast your main arguments and conclusions and provide a brief description of the rest of the paper [the "roadmap"] that let's the reader know where you are going and what to expect. A roadmap is important because it helps the reader place the research problem within the context of their own perspectives about the topic. In addition, concluding your introduction with an explicit roadmap tells the reader that you have a clear understanding of the structural purpose of your paper. In this way, the roadmap acts as a type of promise to yourself and to your readers that you will follow a consistent and coherent approach to addressing the topic of inquiry. Refer to it often to help keep your writing focused and organized.

Cassuto, Leonard. “On the Dissertation: How to Write the Introduction.” The Chronicle of Higher Education , May 28, 2018; Radich, Michael. A Student's Guide to Writing in East Asian Studies . (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Writing n. d.), pp. 35-37.

- << Previous: Executive Summary

- Next: The C.A.R.S. Model >>

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 10:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples

How to Write an Essay Introduction | 4 Steps & Examples

Published on February 4, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A good introduction paragraph is an essential part of any academic essay . It sets up your argument and tells the reader what to expect.

The main goals of an introduction are to:

- Catch your reader’s attention.

- Give background on your topic.

- Present your thesis statement —the central point of your essay.

This introduction example is taken from our interactive essay example on the history of Braille.

The invention of Braille was a major turning point in the history of disability. The writing system of raised dots used by visually impaired people was developed by Louis Braille in nineteenth-century France. In a society that did not value disabled people in general, blindness was particularly stigmatized, and lack of access to reading and writing was a significant barrier to social participation. The idea of tactile reading was not entirely new, but existing methods based on sighted systems were difficult to learn and use. As the first writing system designed for blind people’s needs, Braille was a groundbreaking new accessibility tool. It not only provided practical benefits, but also helped change the cultural status of blindness. This essay begins by discussing the situation of blind people in nineteenth-century Europe. It then describes the invention of Braille and the gradual process of its acceptance within blind education. Subsequently, it explores the wide-ranging effects of this invention on blind people’s social and cultural lives.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: hook your reader, step 2: give background information, step 3: present your thesis statement, step 4: map your essay’s structure, step 5: check and revise, more examples of essay introductions, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about the essay introduction.

Your first sentence sets the tone for the whole essay, so spend some time on writing an effective hook.

Avoid long, dense sentences—start with something clear, concise and catchy that will spark your reader’s curiosity.

The hook should lead the reader into your essay, giving a sense of the topic you’re writing about and why it’s interesting. Avoid overly broad claims or plain statements of fact.

Examples: Writing a good hook

Take a look at these examples of weak hooks and learn how to improve them.

- Braille was an extremely important invention.

- The invention of Braille was a major turning point in the history of disability.

The first sentence is a dry fact; the second sentence is more interesting, making a bold claim about exactly why the topic is important.

- The internet is defined as “a global computer network providing a variety of information and communication facilities.”

- The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education.

Avoid using a dictionary definition as your hook, especially if it’s an obvious term that everyone knows. The improved example here is still broad, but it gives us a much clearer sense of what the essay will be about.

- Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a famous book from the nineteenth century.

- Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement.

Instead of just stating a fact that the reader already knows, the improved hook here tells us about the mainstream interpretation of the book, implying that this essay will offer a different interpretation.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Next, give your reader the context they need to understand your topic and argument. Depending on the subject of your essay, this might include:

- Historical, geographical, or social context

- An outline of the debate you’re addressing

- A summary of relevant theories or research about the topic

- Definitions of key terms

The information here should be broad but clearly focused and relevant to your argument. Don’t give too much detail—you can mention points that you will return to later, but save your evidence and interpretation for the main body of the essay.

How much space you need for background depends on your topic and the scope of your essay. In our Braille example, we take a few sentences to introduce the topic and sketch the social context that the essay will address:

Now it’s time to narrow your focus and show exactly what you want to say about the topic. This is your thesis statement —a sentence or two that sums up your overall argument.

This is the most important part of your introduction. A good thesis isn’t just a statement of fact, but a claim that requires evidence and explanation.

The goal is to clearly convey your own position in a debate or your central point about a topic.

Particularly in longer essays, it’s helpful to end the introduction by signposting what will be covered in each part. Keep it concise and give your reader a clear sense of the direction your argument will take.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

As you research and write, your argument might change focus or direction as you learn more.

For this reason, it’s often a good idea to wait until later in the writing process before you write the introduction paragraph—it can even be the very last thing you write.

When you’ve finished writing the essay body and conclusion , you should return to the introduction and check that it matches the content of the essay.

It’s especially important to make sure your thesis statement accurately represents what you do in the essay. If your argument has gone in a different direction than planned, tweak your thesis statement to match what you actually say.

To polish your writing, you can use something like a paraphrasing tool .

You can use the checklist below to make sure your introduction does everything it’s supposed to.

Checklist: Essay introduction

My first sentence is engaging and relevant.

I have introduced the topic with necessary background information.

I have defined any important terms.

My thesis statement clearly presents my main point or argument.

Everything in the introduction is relevant to the main body of the essay.

You have a strong introduction - now make sure the rest of your essay is just as good.

- Argumentative

- Literary analysis

This introduction to an argumentative essay sets up the debate about the internet and education, and then clearly states the position the essay will argue for.

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts is on the rise, and its role in learning is hotly debated. For many teachers who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its critical benefits for students and educators—as a uniquely comprehensive and accessible information source; a means of exposure to and engagement with different perspectives; and a highly flexible learning environment.

This introduction to a short expository essay leads into the topic (the invention of the printing press) and states the main point the essay will explain (the effect of this invention on European society).

In many ways, the invention of the printing press marked the end of the Middle Ages. The medieval period in Europe is often remembered as a time of intellectual and political stagnation. Prior to the Renaissance, the average person had very limited access to books and was unlikely to be literate. The invention of the printing press in the 15th century allowed for much less restricted circulation of information in Europe, paving the way for the Reformation.

This introduction to a literary analysis essay , about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein , starts by describing a simplistic popular view of the story, and then states how the author will give a more complex analysis of the text’s literary devices.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale. Arguably the first science fiction novel, its plot can be read as a warning about the dangers of scientific advancement unrestrained by ethical considerations. In this reading, and in popular culture representations of the character as a “mad scientist”, Victor Frankenstein represents the callous, arrogant ambition of modern science. However, far from providing a stable image of the character, Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to gradually transform our impression of Frankenstein, portraying him in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Your essay introduction should include three main things, in this order:

- An opening hook to catch the reader’s attention.

- Relevant background information that the reader needs to know.

- A thesis statement that presents your main point or argument.

The length of each part depends on the length and complexity of your essay .

The “hook” is the first sentence of your essay introduction . It should lead the reader into your essay, giving a sense of why it’s interesting.

To write a good hook, avoid overly broad statements or long, dense sentences. Try to start with something clear, concise and catchy that will spark your reader’s curiosity.

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

The thesis statement is essential in any academic essay or research paper for two main reasons:

- It gives your writing direction and focus.

- It gives the reader a concise summary of your main point.

Without a clear thesis statement, an essay can end up rambling and unfocused, leaving your reader unsure of exactly what you want to say.

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement , a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 23). How to Write an Essay Introduction | 4 Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 19, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/introduction/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to conclude an essay | interactive example, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction (with Examples)

The research paper introduction section, along with the Title and Abstract, can be considered the face of any research paper. The following article is intended to guide you in organizing and writing the research paper introduction for a quality academic article or dissertation.

The research paper introduction aims to present the topic to the reader. A study will only be accepted for publishing if you can ascertain that the available literature cannot answer your research question. So it is important to ensure that you have read important studies on that particular topic, especially those within the last five to ten years, and that they are properly referenced in this section. 1 What should be included in the research paper introduction is decided by what you want to tell readers about the reason behind the research and how you plan to fill the knowledge gap. The best research paper introduction provides a systemic review of existing work and demonstrates additional work that needs to be done. It needs to be brief, captivating, and well-referenced; a well-drafted research paper introduction will help the researcher win half the battle.

The introduction for a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your research topic

- Capture reader interest

- Summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Define your specific research problem and problem statement

- Highlight the novelty and contributions of the study

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The research paper introduction can vary in size and structure depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or is a review paper. Some research paper introduction examples are only half a page while others are a few pages long. In many cases, the introduction will be shorter than all of the other sections of your paper; its length depends on the size of your paper as a whole.

- Break through writer’s block. Write your research paper introduction with Paperpal Copilot

Table of Contents

What is the introduction for a research paper, why is the introduction important in a research paper, craft a compelling introduction section with paperpal. try now, 1. introduce the research topic:, 2. determine a research niche:, 3. place your research within the research niche:, craft accurate research paper introductions with paperpal. start writing now, frequently asked questions on research paper introduction, key points to remember.

The introduction in a research paper is placed at the beginning to guide the reader from a broad subject area to the specific topic that your research addresses. They present the following information to the reader

- Scope: The topic covered in the research paper

- Context: Background of your topic

- Importance: Why your research matters in that particular area of research and the industry problem that can be targeted

The research paper introduction conveys a lot of information and can be considered an essential roadmap for the rest of your paper. A good introduction for a research paper is important for the following reasons:

- It stimulates your reader’s interest: A good introduction section can make your readers want to read your paper by capturing their interest. It informs the reader what they are going to learn and helps determine if the topic is of interest to them.

- It helps the reader understand the research background: Without a clear introduction, your readers may feel confused and even struggle when reading your paper. A good research paper introduction will prepare them for the in-depth research to come. It provides you the opportunity to engage with the readers and demonstrate your knowledge and authority on the specific topic.

- It explains why your research paper is worth reading: Your introduction can convey a lot of information to your readers. It introduces the topic, why the topic is important, and how you plan to proceed with your research.

- It helps guide the reader through the rest of the paper: The research paper introduction gives the reader a sense of the nature of the information that will support your arguments and the general organization of the paragraphs that will follow. It offers an overview of what to expect when reading the main body of your paper.

What are the parts of introduction in the research?

A good research paper introduction section should comprise three main elements: 2

- What is known: This sets the stage for your research. It informs the readers of what is known on the subject.

- What is lacking: This is aimed at justifying the reason for carrying out your research. This could involve investigating a new concept or method or building upon previous research.

- What you aim to do: This part briefly states the objectives of your research and its major contributions. Your detailed hypothesis will also form a part of this section.

How to write a research paper introduction?

The first step in writing the research paper introduction is to inform the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening statement. The second step involves establishing the kinds of research that have been done and ending with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to address. Finally, the research paper introduction clarifies how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses. If your research involved testing hypotheses, these should be stated along with your research question. The hypothesis should be presented in the past tense since it will have been tested by the time you are writing the research paper introduction.

The following key points, with examples, can guide you when writing the research paper introduction section:

- Highlight the importance of the research field or topic

- Describe the background of the topic

- Present an overview of current research on the topic

Example: The inclusion of experiential and competency-based learning has benefitted electronics engineering education. Industry partnerships provide an excellent alternative for students wanting to engage in solving real-world challenges. Industry-academia participation has grown in recent years due to the need for skilled engineers with practical training and specialized expertise. However, from the educational perspective, many activities are needed to incorporate sustainable development goals into the university curricula and consolidate learning innovation in universities.

- Reveal a gap in existing research or oppose an existing assumption

- Formulate the research question

Example: There have been plausible efforts to integrate educational activities in higher education electronics engineering programs. However, very few studies have considered using educational research methods for performance evaluation of competency-based higher engineering education, with a focus on technical and or transversal skills. To remedy the current need for evaluating competencies in STEM fields and providing sustainable development goals in engineering education, in this study, a comparison was drawn between study groups without and with industry partners.

- State the purpose of your study

- Highlight the key characteristics of your study

- Describe important results

- Highlight the novelty of the study.

- Offer a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

Example: The study evaluates the main competency needed in the applied electronics course, which is a fundamental core subject for many electronics engineering undergraduate programs. We compared two groups, without and with an industrial partner, that offered real-world projects to solve during the semester. This comparison can help determine significant differences in both groups in terms of developing subject competency and achieving sustainable development goals.

Write a Research Paper Introduction in Minutes with Paperpal

Paperpal Copilot is a generative AI-powered academic writing assistant. It’s trained on millions of published scholarly articles and over 20 years of STM experience. Paperpal Copilot helps authors write better and faster with:

- Real-time writing suggestions

- In-depth checks for language and grammar correction

- Paraphrasing to add variety, ensure academic tone, and trim text to meet journal limits

With Paperpal Copilot, create a research paper introduction effortlessly. In this step-by-step guide, we’ll walk you through how Paperpal transforms your initial ideas into a polished and publication-ready introduction.

How to use Paperpal to write the Introduction section

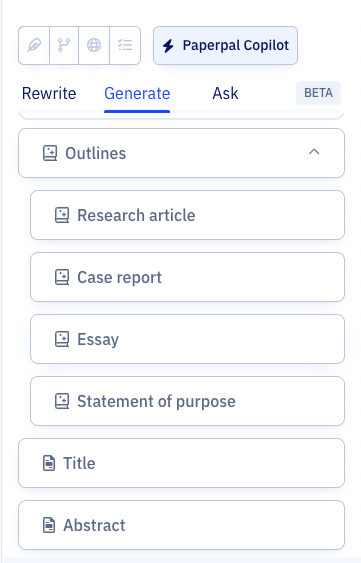

Step 1: Sign up on Paperpal and click on the Copilot feature, under this choose Outlines > Research Article > Introduction

Step 2: Add your unstructured notes or initial draft, whether in English or another language, to Paperpal, which is to be used as the base for your content.

Step 3: Fill in the specifics, such as your field of study, brief description or details you want to include, which will help the AI generate the outline for your Introduction.

Step 4: Use this outline and sentence suggestions to develop your content, adding citations where needed and modifying it to align with your specific research focus.

Step 5: Turn to Paperpal’s granular language checks to refine your content, tailor it to reflect your personal writing style, and ensure it effectively conveys your message.

You can use the same process to develop each section of your article, and finally your research paper in half the time and without any of the stress.

The purpose of the research paper introduction is to introduce the reader to the problem definition, justify the need for the study, and describe the main theme of the study. The aim is to gain the reader’s attention by providing them with necessary background information and establishing the main purpose and direction of the research.

The length of the research paper introduction can vary across journals and disciplines. While there are no strict word limits for writing the research paper introduction, an ideal length would be one page, with a maximum of 400 words over 1-4 paragraphs. Generally, it is one of the shorter sections of the paper as the reader is assumed to have at least a reasonable knowledge about the topic. 2 For example, for a study evaluating the role of building design in ensuring fire safety, there is no need to discuss definitions and nature of fire in the introduction; you could start by commenting upon the existing practices for fire safety and how your study will add to the existing knowledge and practice.

When deciding what to include in the research paper introduction, the rest of the paper should also be considered. The aim is to introduce the reader smoothly to the topic and facilitate an easy read without much dependency on external sources. 3 Below is a list of elements you can include to prepare a research paper introduction outline and follow it when you are writing the research paper introduction. Topic introduction: This can include key definitions and a brief history of the topic. Research context and background: Offer the readers some general information and then narrow it down to specific aspects. Details of the research you conducted: A brief literature review can be included to support your arguments or line of thought. Rationale for the study: This establishes the relevance of your study and establishes its importance. Importance of your research: The main contributions are highlighted to help establish the novelty of your study Research hypothesis: Introduce your research question and propose an expected outcome. Organization of the paper: Include a short paragraph of 3-4 sentences that highlights your plan for the entire paper

Cite only works that are most relevant to your topic; as a general rule, you can include one to three. Note that readers want to see evidence of original thinking. So it is better to avoid using too many references as it does not leave much room for your personal standpoint to shine through. Citations in your research paper introduction support the key points, and the number of citations depend on the subject matter and the point discussed. If the research paper introduction is too long or overflowing with citations, it is better to cite a few review articles rather than the individual articles summarized in the review. A good point to remember when citing research papers in the introduction section is to include at least one-third of the references in the introduction.

The literature review plays a significant role in the research paper introduction section. A good literature review accomplishes the following: Introduces the topic – Establishes the study’s significance – Provides an overview of the relevant literature – Provides context for the study using literature – Identifies knowledge gaps However, remember to avoid making the following mistakes when writing a research paper introduction: Do not use studies from the literature review to aggressively support your research Avoid direct quoting Do not allow literature review to be the focus of this section. Instead, the literature review should only aid in setting a foundation for the manuscript.

Remember the following key points for writing a good research paper introduction: 4

- Avoid stuffing too much general information: Avoid including what an average reader would know and include only that information related to the problem being addressed in the research paper introduction. For example, when describing a comparative study of non-traditional methods for mechanical design optimization, information related to the traditional methods and differences between traditional and non-traditional methods would not be relevant. In this case, the introduction for the research paper should begin with the state-of-the-art non-traditional methods and methods to evaluate the efficiency of newly developed algorithms.

- Avoid packing too many references: Cite only the required works in your research paper introduction. The other works can be included in the discussion section to strengthen your findings.

- Avoid extensive criticism of previous studies: Avoid being overly critical of earlier studies while setting the rationale for your study. A better place for this would be the Discussion section, where you can highlight the advantages of your method.

- Avoid describing conclusions of the study: When writing a research paper introduction remember not to include the findings of your study. The aim is to let the readers know what question is being answered. The actual answer should only be given in the Results and Discussion section.

To summarize, the research paper introduction section should be brief yet informative. It should convince the reader the need to conduct the study and motivate him to read further. If you’re feeling stuck or unsure, choose trusted AI academic writing assistants like Paperpal to effortlessly craft your research paper introduction and other sections of your research article.

1. Jawaid, S. A., & Jawaid, M. (2019). How to write introduction and discussion. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 13(Suppl 1), S18.

2. Dewan, P., & Gupta, P. (2016). Writing the title, abstract and introduction: Looks matter!. Indian pediatrics, 53, 235-241.

3. Cetin, S., & Hackam, D. J. (2005). An approach to the writing of a scientific Manuscript1. Journal of Surgical Research, 128(2), 165-167.

4. Bavdekar, S. B. (2015). Writing introduction: Laying the foundations of a research paper. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 63(7), 44-6.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Scientific Writing Style Guides Explained

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

Practice vs. Practise: Learn the Difference

Academic paraphrasing: why paperpal’s rewrite should be your first choice , you may also like, how to write the first draft of a..., mla works cited page: format, template & examples, how to write a high-quality conference paper, academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, phd qualifying exam: tips for success , ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without..., what are journal guidelines on using generative ai..., quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Writing Your Introduction

Introductions [1].

There is no doubt about it: the introduction is important for any kind of writing. Not only does a good introduction capture your reader’s attention and make him or her want to read on, it’s how you put the topic of your paper into context for the reader.

But just because the introduction comes at the beginning, it doesn’t have to be written first. Many writers compose their introductions last, once they are sure of the main points of their paper and have had time to construct a thought provoking beginning, and a clear, cogent research statement.

Introductions Purpose

The introduction has work to do, besides grabbing the reader’s attention. Below are some things to consider about the purposes or the tasks for your introduction and some examples of how you might approach those tasks.

The introduction needs to alert the reader to what the central issue of the paper is.

The introduction is where you provide any important background information the reader should have before getting to the thesis.

The introduction tells why you have written the paper and what the reader should understand about your topic and your perspective.

The introduction tells the reader what to expect and what to look for in your essay.

The research question or statement (typically at the end of the introduction) should clearly state the claim, question, or point of view the writer is putting forth in the paper.

Introductions Strategies

Although there is no one “right” way to write your introduction, there are some common introductory strategies that work well. The strategies below are ones you should consider, especially when you are feeling stuck and having a hard time getting started.

Consider opening with an anecdote, a pithy quotation, a question, or a startling fact to provoke your reader’s interest. Just make sure that the opening helps put your topic in some useful context for the reader.

Of course, these are just some examples of how you might get your introduction started , but there should be more to your introduction. Once you have your readers’ attention, you want to provide context for your topic and begin to transition to your research question, and don’t forget to include that research question (usually at or near the end of your introduction).

- Adapted from Excelsior Online Writing Lab (OWL). (n.d.). Introductions & conclusions. Retrieved from https://owl.excelsior.edu/writing-process/introductions-and-conclusions/. Licensed under CC-BY-4.0. ↵

PSY-250 Research Paper Guidelines and Resources Copyright © by David Adams. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

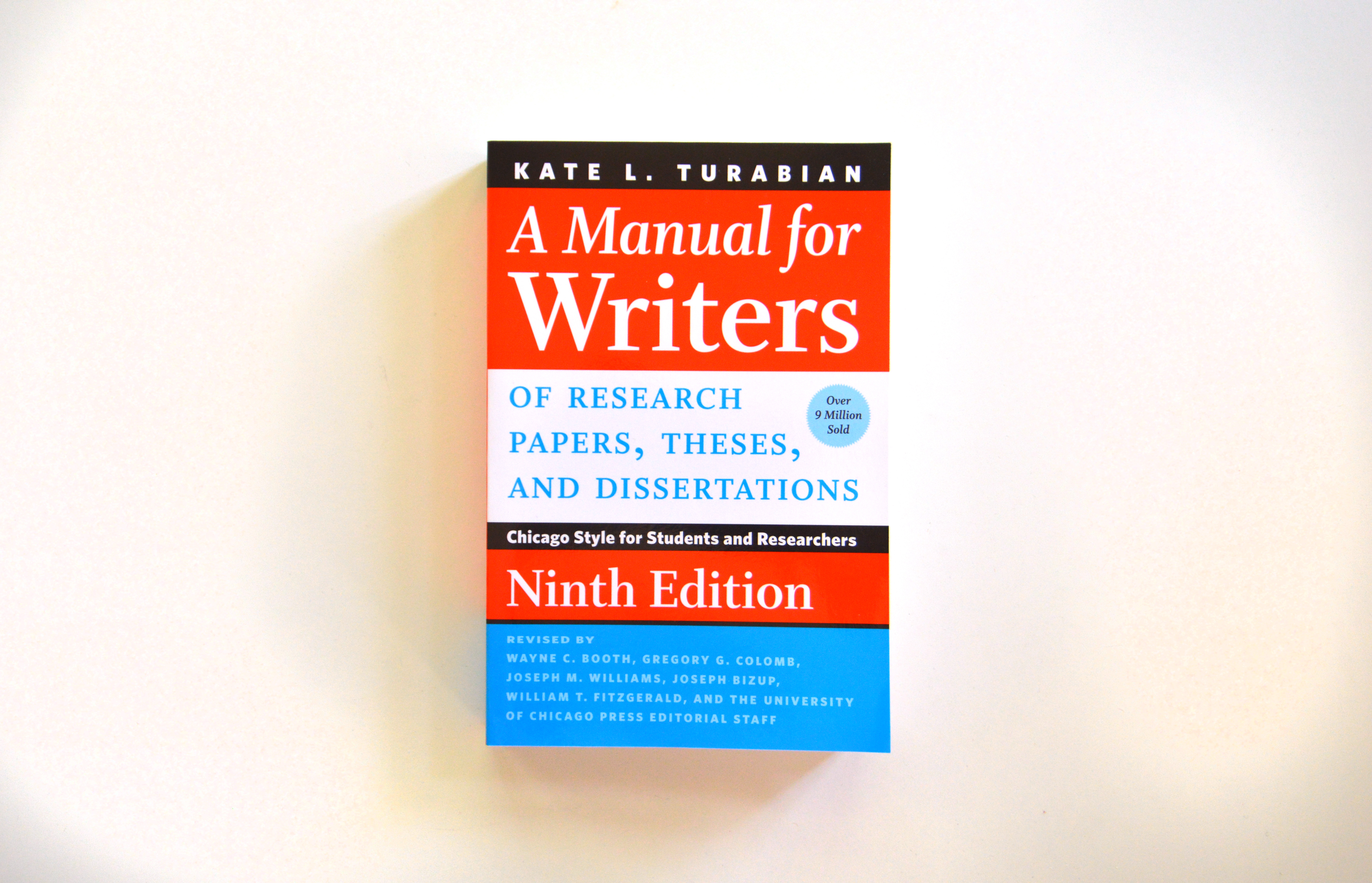

A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations, Ninth Edition

Chicago style for students and researchers.

Ninth Edition

Kate L. Turabian

- Bestselling, trusted, and time-tested advice for writing research papers

- The best interpretation of Chicago style for higher education students and researchers

- Definitive, clear, and easy to read, with plenty of examples

- Shows how to compose a strong research question, construct an evidence-based argument, cite sources, and structure work in a logical way

- Essential for anyone interested in learning about research

- Everything any student or teacher needs to know concerning paper writing

A website for the book, including our Quick Citation Guide.

464 pages | 11 halftones, 22 line drawings, 12 tables | 6 x 9 | © 2018

Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing

Language and Linguistics: Language--Reference

Library Science and Publishing: Publishing

Reference and Bibliography

Rhetoric and Communication

- Table of contents

- Author Events

Related Titles

“Without doubt, for anyone interested in learning about research—what it is, where one goes to pursue it, how to do it, what it entails and means, why it is important (now more so than ever before)— A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations: Chicago Style for Students and Researchers is the place to begin. It will likely show people new to the field a way forward and offer experienced researchers the means to test established modes of operation. This book will not fail you, today or tomorrow, at home or in the library. Look for it at a bookstore near you or online.”

Thomas R. Claire | Publishing Research Quarterly

“Turabian’s A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations continues a tradition of providing one of the best interpretations of The Chicago Manual of Style for higher education students and researchers in this ninth edition. The writing style is clear and easy to read, with examples illustrating proper formatting of items.”

Cynthia Goode | American Reference Books Annual

"A mainstay in high-school and college libraries."

Praise for a previous edition | Booklist

“This definitive handbook supplies information on about everything any student or teacher may desire to know concerning paper writing.”

Praise for a previous edition | Quill and Scroll

“Kate L. Turabian was our trusted guide and mentor, the absolute authority, the one who knew all there was to know about the strange world of proper term papers. . . . To write a term paper without a well-worn copy of Turabian handy was unthinkable. Our writing on term papers might be weak, our research haphazard, our insights sophomoric, but, thanks to Kate L. Turabian, our footnotes could always be absolutely flawless.”

Praise for a previous edition | Seattle Post-Intelligencer

"Indispensable. . . . Turabian is everything a student researcher might need save a grammar guide and training in specific research methods. . . . When you consider the sheer wealth of material contained or cited in Turabian, its US $18.00 paperback and eBook list price is an absolute steal."

Steven E. Gump | Journal of Scholarly Publishing

Write No Matter What

Joli Jensen

How to Write a BA Thesis, Second Edition

Charles Lipson

Student’s Guide to Writing College Papers, Fifth Edition

57 ways to screw up in grad school.

Kevin D. Haggerty

Be the first to know

Get the latest updates on new releases, special offers, and media highlights when you subscribe to our email lists!

Sign up here for updates about the Press

- Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

- Cardio-Oncology

- Research Topics

Case Reports in Cardio-Oncology: 2024

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

This Research Topic is the third volume of 'Case Reports in Cardio-Oncology'. Please see the previous volume here. This Research Topic aims to collect all the Case Reports submitted to the Cardio-Oncology section. If submitted directly to this collection the paper will be personally assessed by a Senior Associate Editor before the beginning of the peer-review process. Please make sure your article adheres to the following guidelines before submitting it. Case Reports highlight unique cases of patients that present with an unexpected diagnosis, treatment outcome, or clinical course: 1) Rare cases with Typical features 2) Frequent cases with Atypical features 3) Cases with a convincing response to new treatments, i.e. single case of off-label use Case Report format: - Maximum word count: 3000 words - Title: Case Report: “area of focus” - Abstract. - Introduction: including what is unique about the case and medical literature references. - Case description: including de-identified patient information, relevant physical examination and other clinical findings, relevant past interventions, and their outcomes. - A figure or table showcasing a timeline with relevant data from the episode of care. - Diagnostic assessment, details on the therapeutic intervention, follow-up, and outcomes, as specified in the CARE guidelines. - Discussion: strengths and limitations of the approach to the case, discussion of the relevant medical literature (similar and contrasting cases), take-away lessons from the case. - Patient perspective. Please, note that authors are required to obtain written informed consent from the patients (or their legal representatives) for the publication. IMPORTANT: Only Case Reports that are original and significantly advance the field will be considered.

Keywords : case reports

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, submission deadlines.

| Manuscript Summary | |

| Manuscript |

Participating Journals

Manuscripts can be submitted to this Research Topic via the following journals:

total views

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

This paper is in the following e-collection/theme issue:

Published on 20.6.2024 in Vol 26 (2024)

Effect of Digital Early Warning Scores on Hospital Vital Sign Observation Protocol Adherence: Stepped-Wedge Evaluation

Authors of this article:

Original Paper

- David Chi-Wai Wong 1 , MEng, DPhil ;

- Timothy Bonnici 2 , BSc, MBBS, PhD ;

- Stephen Gerry 3 , BSc, MSc ;

- Jacqueline Birks 3 , MA, MSc ;

- Peter J Watkinson 4, 5, 6 , MD

1 Leeds Institute of Health Sciences, School of Medicine, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom

2 Critical Care Division, University College Hospital London NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom

3 Centre for Statistics in Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

4 Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust, Oxford, United Kingdom

5 NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, United Kingdom

6 Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Kadoorie Centre for Critical Care Research and Education, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Corresponding Author:

David Chi-Wai Wong, MEng, DPhil

Leeds Institute of Health Sciences

School of Medicine

University of Leeds

Worsley Building

Leeds, LS2 9JT

United Kingdom

Phone: 44 113 343 0806

Email: [email protected]

Background: Early warning scores (EWS) are routinely used in hospitals to assess a patient’s risk of deterioration. EWS are traditionally recorded on paper observation charts but are increasingly recorded digitally. In either case, evidence for the clinical effectiveness of such scores is mixed, and previous studies have not considered whether EWS leads to changes in how deteriorating patients are managed.

Objective: This study aims to examine whether the introduction of a digital EWS system was associated with more frequent observation of patients with abnormal vital signs, a precursor to earlier clinical intervention.

Methods: We conducted a 2-armed stepped-wedge study from February 2015 to December 2016, over 4 hospitals in 1 UK hospital trust. In the control arm, vital signs were recorded using paper observation charts. In the intervention arm, a digital EWS system was used. The primary outcome measure was time to next observation (TTNO), defined as the time between a patient’s first elevated EWS (EWS ≥3) and subsequent observations set. Secondary outcomes were time to death in the hospital, length of stay, and time to unplanned intensive care unit admission. Differences between the 2 arms were analyzed using a mixed-effects Cox model. The usability of the system was assessed using the system usability score survey.

Results: We included 12,802 admissions, 1084 in the paper (control) arm and 11,718 in the digital EWS (intervention) arm. The system usability score was 77.6, indicating good usability. The median TTNO in the control and intervention arms were 128 (IQR 73-218) minutes and 131 (IQR 73-223) minutes, respectively. The corresponding hazard ratio for TTNO was 0.99 (95% CI 0.91-1.07; P =.73).

Conclusions: We demonstrated strong clinical engagement with the system. We found no difference in any of the predefined patient outcomes, suggesting that the introduction of a highly usable electronic system can be achieved without impacting clinical care. Our findings contrast with previous claims that digital EWS systems are associated with improvement in clinical outcomes. Future research should investigate how digital EWS systems can be integrated with new clinical pathways adjusting staff behaviors to improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Avoidable mortality from unrecognized clinical deterioration is an internationally recognized problem [ 1 ]. Such deterioration often corresponds with deviations in patient vital signs early warning score (EWS) algorithms have been introduced to improve the recognition of abnormal vital signs [ 2 ]. They assign a score to each vital sign value according to the degree of abnormality. The total score is a measure of patient risk. Many EWS algorithms have been published and their use is mandated by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence in the United Kingdom [ 3 , 4 ]. Since 2018, 1 standard EWS, the National Early Warning Score 2, has been mandated in acute hospital trusts [ 5 ].

EWS algorithms are accompanied by an escalation protocol, which dictates how frequently the patient should be monitored and what other actions staff should take for each value of the total score. If the EWS score exceeds the “trigger threshold” defined in the escalation protocol, the nursing staff must call a doctor to review the patient.

Despite the widespread adoption of EWS algorithms and associated escalation protocols, patient outcomes have not improved significantly [ 6 , 7 ]. It is possible that errors in the calculation of the EWS are partially to blame. Studies have shown that errors in the calculation of EWS are common and failure to calculate the correct EWS may result in failure to take the correct action [ 8 , 9 ]. Other barriers to escalation include delays in documentation, lack of familiarity with the escalation protocol, failure to follow the protocol, and poor communication [ 10 , 11 ].

Digital EWS systems have been proposed as a solution. These systems automatically calculate the EWS based on data input by staff and display relevant information from the escalation protocol. These data may be displayed to the staff at the bedside, on mobile devices, or at nursing station dashboards, enabling senior clinicians to rapidly survey patient acuity across an area.

At present there is no robust evidence of changes in clinical outcomes to support or refute the case for the introduction of electronic EWS systems. Most recent studies focus on improving the predictive ability of the scoring system itself [ 12 , 13 ], ignoring the complex interaction with health care staff and infrastructure required to affect clinical decision-making. The limited number of studies of digital EWS systems in clinical practice have shown inconsistent results [ 14 - 16 ]. Some have used uncontrolled “before and after” design methodologies, comparing data from periods several years apart, which are limited by their inability to control for temporal confounding such as changes in case mix [ 17 ]. Furthermore, very few existing studies have not provided insight into the mechanisms by which any reported improvements were achieved [ 18 ].

This study aimed to examine whether the introduction of a digital EWS charting system leads to improvements in patient care. Our causal hypothesis is that, compared with paper charting, the use of a digital EWS system leads to better recognition of patient deterioration and closer adherence to the hospital escalation protocol. These behavior changes would lead to the more frequent observation of patients with abnormal vital signs and therefore earlier escalation. Earlier escalation would lead to improvements in both process metrics and patient outcomes.

The staged replacement of paper EWS charting with a digital EWS charting system at the Oxford University Hospitals Foundation NHS Trust (OUHFT) provided us the opportunity to conduct a natural experiment using a nonrandomized stepped wedge trial design.

Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was reviewed by the OUHFT’s Research and Development department, and based upon Health Care Quality Improvement Partnership guidelines and was deemed to be a service evaluation (ID: 3196), not requiring review by the National Research Ethics Service. All methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. As patient data were collected without their consent, permission for informed consent waiver was obtained from the Trust’s Caldicott Guardian and Medical Director in accordance with the Health Research Authority Confidentiality Advisory Group guidelines. All study data were deidentified and patients were not compensated. The full study protocol has previously been published and is summarized below [ 19 ].

Study Setting

The OUHFT is comprised of 4 hospitals: 1 large teaching hospital, a small district general hospital, and 2 specialist hospitals that do not have emergency departments. Two of the hospitals have intensive care units (ICU) that also act as high-dependency units, and 2 have high-dependency units only.

The digital EWS implemented at OUHFT was the system for electronic notification and documentation (SEND) system [ 20 ], a system in which clinical users manually enter vital sign observation data onto a tablet PC. The system then automatically calculates an EWS and displays relevant advice from hospital escalation protocols.

The tablet is physically mounted to a roll-stand with a blood pressure monitor, as shown in Figure 1 . The system displays historical vital sign observations of a patient ( Figure 1 ), and ward-level and hospital-level overviews are available via desktop computers.

The EWS used at OUHFT was the centile early warning score (CEWS) [ 21 ]. CEWS uses 6 vital signs as input parameters, which are each scored from 0 to 3 ( Table 1 ). The trigger threshold is set at 3. For any CEWS greater than or equal to the trigger threshold, the escalation protocol mandates hourly observations and review by a senior doctor. CEWS also allows a nurse to indicate clinical concern. When a nurse is concerned, hourly observations and escalation to a doctor are mandated, irrespective of the CEWS score. A copy of the paper EWS chart and a full description of the escalation protocol are provided in Multimedia Appendix 1 .

| Vital signs | Subscores | ||||||

| 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Temperature (°C) | ≤35.4 | — | 35.5-35.9 | 36.0-37.3 | 37.4-38.3 | — | ≥38.4 |

| Heart rate (/min) | ≤42 | 43-49 | 50-53 | 54-104 | 105-112 | 113-127 | ≥128 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | ≤85 | 86-96 | 97-101 | 102-154 | 155-164 | 165-184 | ≥185 |

| Respiratory rate (/min) | ≤7 | 8-10 | 11-13 | 14-19 | 20-21 | 22-24 | ≥25 |

| SpO (%) | ≤84 | 85-90 | 91-93 | ≥94 | — | — | — |

| Level of consciousness (AVPU or GCS ) | P and U GCS ≤13 | — | V GCS:14 | A GCS: 15 | — | — | — |

a Not available.

b SpO 2 : peripheral arterial oxygen saturation.

c AVPU: Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive.

d GCS: Glasgow coma scale.

Trial Design

The stepped-wedge study comprised 2 arms, a control arm in which vital signs were recorded using paper observation charts and an intervention arm where the digital EWS system, SEND, was used. The EWS and escalation protocol were identical in both arms.

The study consisted of 20 clusters (and 21 steps). We defined a cluster as a group of between 1 and 5 eligible wards that implemented SEND simultaneously. All wards that were due to switch to the SEND system were eligible for inclusion in a cluster; we defined these as “study wards.” Study wards included all adult wards across the Trust, except for the obstetric wards, emergency departments, day units, high dependency units, ICUs, and investigation suites, which were excluded as they did not use standard hospital observation recording and escalation policies. We also excluded the 3 wards where the SEND system was initially developed and piloted, as the control condition, paper charting, was no longer used at the commencement of the study.

Clusters of wards were determined by pragmatic considerations related to the safe conduct of the rollout. For example, each cluster only contained wards from an individual hospital. The sequence of study clusters was predetermined by the system rollout strategy and was therefore not randomized.

The rollout schedule is depicted in Figure 2 . The time period between the start of each step was typically 2 weeks. The period was occasionally lengthened to account for project management issues such as reduced staffing over the Christmas holidays (exact dates are provided in Multimedia Appendix 2 ). The final period, which occurred after SEND was fully deployed to all wards, lasted 3 months. The extended period was designed to capture any delayed effects caused by wards adapting to the new system.

Each study ward admitted multiple patients during each step. Data for this study was obtained at an individual patient level. A patient’s data belonged to only 1 step, that is, each cluster and period contained data pertaining to different people. We included all patient admissions to the study wards during the study period rather than censoring data from repeated admissions. Therefore, some patients could potentially contribute data to multiple steps on different admissions. We treated multiple episodes within the same patient as independent, reasoning that the primary outcome was unlikely to be causally related to patient characteristics. We excluded data from admissions where patients crossed study arms (ie, the ward moved from paper to digital EWS) during their admission.

Data Collection

Data from the control arm were collected by 7 research assistants transcribing data from paper charts located on each study ward into a bespoke electronic form. This was a resource-intensive process, making it unfeasible to collect data from all clusters simultaneously for the duration of the study. Therefore, we commenced data for the control arm at the start of the roll-out to each hospital site and limited it to the site where SEND was actively rolled out (illustrated in Figure 2 ). To make this tractable, we further split the largest hospital (Hospital D), into 2 sites (Main Wing, second Wing). Data from the intervention arm was continued even once the roll-out of the intervention at a given hospital was complete such that patients from the hospital contributed more data to the intervention arm than data in subsequent hospitals. In summary, data collection may be considered as separate stepped wedges associated with each of the 5 sites, with varying lengths of data from after the intervention.

For each patient admission within each study cluster, we collected patient characteristics (age, gender, Charlson score, admission type, and admitting specialty), the date and times of admission to the ward; first observation with CEWS ≥3 and the immediate subsequent observation; hospital discharge; hospital mortality; transfer to ICU; cardiac arrest call; and theatre admission.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the time to next observation (TTNO), defined as the time between a patient’s first triggering observations set (CEWS score ≥3) and the subsequent observations set. To address potential confounding by length of ward stay, analysis of the primary outcome measure was restricted to triggering observation sets that occurred within 48 hours of transfer to the first study ward of an admission.

Secondary outcome measures were time to death in the hospital, time to unplanned ICU admission, time to cardiac arrest call, and hospital length of stay (LOS). In each case, the start time was the time of the initial triggering set of observations.

We reported these outcomes for the subgroup included in the analysis of the primary outcome measure (ie, those patients who had a CEWS score ≥3), in line with our causal hypothesis. We also reported the secondary outcomes for all eligible admissions. In these analyses, we used the time of admission to the study ward as the start time.

Finally, we reported system usability to provide further context. System usability was measured using the system usability scale, a validated 10-item questionnaire that is used to generate a score between 0 and 100 [ 22 ]. We delivered the questionnaire electronically to all users of the digital system. The questionnaire is included in Multimedia Appendix 3 .

Sample Size

The upper bound on the number of patient admissions included in the study was determined by the pragmatic roll-out schedule of the intervention. To determine whether this would be sufficient, we initially undertook a power calculation for steps 1-8, using unpublished pilot data from the Computer Alerting Monitoring System 2 study [ 23 ]. We assumed that the proportion of patients who have a further observation within 3 hours of recording an EWS ≥3 would be 0.5 in the paper arm and 0.6 in the electronic arm, that there would be an average of 11 patients with an initial CEWS ≥3 per cluster, and conservatively that the intracluster correlation will be 0.15. The power was then estimated to be 79.3% for a 5% α level. While the calculation depended on statistics estimated from limited pilot data, it indicated that the inclusion of all steps would be sufficiently powerful to detect a difference of 10% in the primary outcome between groups. Full details of this calculation are provided in Multimedia Appendix 4 .

Statistical Methods

The primary outcome, the difference in TTNO between arms, was analyzed using a mixed-effects Cox model with a random intercept for cluster and a fixed effect for time as described by Hussey and Hughes [ 24 ]. The model included in-hospital death, ICU admission, theatre admission, and cardiac arrest calls as competing events.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis using 5 variants of the basic Hussey and Hughes model, as originally proposed by Hemming et al [ 25 ]. The five variants were: (1) time by strata interaction (fixed effects), (2) time by cluster interaction (random effects), (3) treatment by strata interaction (fixed effects), (4) treatment by cluster interaction (random effects), and (5) treatment by time interaction (fixed effects). Secondary outcomes were analyzed using the same method.

To aid interpretation, we calculated the average TTNO in each arm as the mean of the median (IQR) TTNO within each unit of the stepped wedge cluster.

We reported baseline descriptive statistics on patient characteristics, including age and sex, by study arm. We also reported these data for each time period to help understand whether trends in baseline characteristics differed between the control and intervention arms.

We conducted the study between January 2015 and September 2016, after the conclusion of the rollout of SEND. During this time, there were 90,262 admissions to the study wards. For 2927 (3%) of admissions, vital signs were recorded on both paper and SEND systems and thus excluded. Of the remaining 87,335 admissions, 40,885 (47%) had vital signs recorded exclusively on paper (control arm) and 46,450 (53%) admissions involved patients who had vital signs recorded exclusively using SEND (intervention arm). Of the admissions in the control arm, 11,597 occurred during the implementation period and were available for data capture. In total, 12,802 admissions were entered into the analysis, consisting of 1084 admissions in the control arm and 11,718 admissions in the intervention arm that had a triggering observation within 48 hours of arrival on their first study ward ( Figure 3 ).

Admission characteristics for the control and intervention are presented in Table 2 . Admissions in the intervention arm tended to be slightly older (median age 65 vs 70 years), more likely to be male (49.3% vs 45.6%), and have a higher number of comorbidities (median Charlson score 3 vs 4).

| Characteristics | Control (paper) | Intervention (SEND ) | |||

| Admissions | 1084 | 11,718 | |||

| Patients | 1048 | 10,708 | |||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 65 (49-79) | 70 (54-81) | |||

| Sex (male), n (%) | 494 (45.6) | 5777 (49.3) | |||

| Charlson score, median (IQR) | 3 (0-10) | 4 (0-12) | |||

| Elective | 392 (36.2) | 4281 (36.5) | |||

| Emergency | 692 (63.9) | 7427 (63.4) | |||

| Other | 0 (0) | 10 (0.1) | |||

| Medical | 430 (40) | 5618 (47.9) | |||

| Surgical | 645 (59.5) | 5894 (50.3) | |||

| Other | 9 (0.8) | 206 (1.76) | |||

a SEND: system for electronic notification and documentation.

The proportion of male to female sex in both study arms was similar across all steps apart from cluster 1, in which there were a small number of admissions on paper (n=10). There were no males in cluster 20, a cluster that contained only obstetrics and gynecology wards. Proportions of elective and emergency admissions, and medical and surgical admissions, were similar for each study arm across all clusters.

Primary Outcome

There was no significant difference in the TTNO between the 2 arms after adjustment for competing events ( Table 3 ). The median TTNO in the control arm was 128 (IQR 73-218) minutes. The median TTNO in the observation arm was 131 (IQR 73-223) minutes. The hazard ratio of the TTNO using paper charting and the TTNO using SEND was 0.99 (95% CI 0.91-1.07, P =.73). All model variants in the sensitivity analysis gave results consistent with the Hussey and Hughes model primary analysis. The numbers of each type of competing events in each arm are shown in Table 4 .

| Model | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | value | |

| 0.99 (0.91-1.07) | .73 | ||

| Time by strata interaction (FE ) | Does not fit | — | |

| Time by cluster interaction (RE ) | 0.98 (0.91-1.07) | .72 | |