The Art of Questioning: Techniques to Promote Critical Thinking and Inquiry

We can all agree that critical thinking is an essential skill for students to develop.

This article will provide educators with a comprehensive guide on the art of questioning - powerful techniques to promote critical thinking, inquiry, and deep learning in the classroom.

You'll discover the core principles of effective questioning, actionable strategies to engage different types of learners, as well as sample activities and assessments to put these methods into practice. Equipped with these practical tools, you can transform class discussions that foster students' natural curiosity and grow their capacity for critical thought.

Embracing the Importance of Art of Questioning

The art of questioning is a critical skill for educators to develop. Questioning techniques that promote critical thinking and inquiry-based learning lead to increased student engagement and deeper understanding. By mastering various strategic questioning approaches, teachers can stimulate complex thinking in their students.

Defining the Art of Questioning

The art of questioning refers to the teacher's ability to craft and ask meaningful questions that push students to think more critically. It goes beyond surface-level, fact-based questioning and instead focuses on stimulating analysis, evaluation, creation, connection-making, and reflection. Well-designed questions require students to tap into higher-order cognitive skills and prior knowledge to construct responses. This process mirrors real-world critical thinking and problem-solving.

Benefits of Mastering Questioning Techniques

Teachers skilled in questioning techniques reap many rewards, including:

- Increased student participation and engagement during lessons

- Development of students' critical thinking capacities

- Ability to check students' understanding and identify knowledge gaps

- Scaffolding learning to meet students at their zone of proximal development

- Encouragement of inquiry, sparking student curiosity and motivation to learn

By honing their questioning approach, teachers gain an invaluable tool for promoting deep learning.

The Role of Questioning in Early Childhood Education

Questioning plays a pivotal role in early childhood education by fostering mental activity and communities of practice. Crafting developmentally-appropriate questions allows teachers to gauge children's baseline understanding and then scaffold new concepts. This questioning facilitates theory of mind growth, as children learn to articulate their thought processes. An inquiry-based classroom also encourages participation, inclusive learning, and problem-solving. Ultimately, strategic questioning lays the foundation for critical thinking that will benefit students throughout their education.

What is the art of questioning critical thinking?

The art of questioning refers to the skill of asking thoughtful, open-ended questions that promote critical thinking , inquiry, and deeper learning. As an educator, mastering this art is key to creating an engaging classroom environment where students actively participate.

Here are some best practices around the art of questioning:

Use Open-Ended Questions

Open-ended questions allow students to explain their thought process and help teachers identify gaps in understanding. For example, asking "Why do you think the character made that decision?" lets students share their unique perspectives. Closed-ended questions that just require yes/no answers should be used sparingly.

Ask Follow-Up Questions

Asking follow-up questions based on students' responses shows you are listening and encourages them to expand upon their ideas. Phrases like "Tell me more about..." or "What makes you think that?" stimulate further discussion.

Pause After Posing Questions

Providing wait time of 3-5 seconds after asking a question gives students time to reflect and articulate a thoughtful response, rather than feeling put on the spot.

Scaffold Complex Questions

Break down multi-layered questions into smaller parts to make them more manageable. You can also give students a framework to help organize their thoughts before answering.

Encourage Multiple Perspectives

Prompt students to consider other vantage points by asking, "How might this look from X's perspective?" This builds empathy, critical analysis skills, and more inclusive thinking.

Mastering the art questioning leads to richer class discussions and unlocks students' intellectual curiosity. With practice, you'll be able to stimulate vibrant student-centered dialogue.

What questioning techniques promote critical thinking?

Asking effective questions is a skill that takes practice to develop. Here are some techniques to promote critical thinking through questioning:

Ask questions that require more than a one-word response. This encourages students to explain their reasoning and make connections. For example:

- Why do you think that?

- What evidence supports your conclusion?

- How does this relate to what we learned before?

Dig deeper into student responses by asking them to expand upon their ideas. This helps clarify understanding and uncover misconceptions. Some follow up questions include:

- Can you explain what you mean by that?

- What makes you think that?

- How does that apply to this situation?

Pause After Questions

Provide wait time of 3-5 seconds after posing a question. This gives students time to think and construct an answer, promoting deeper reflection. Resist the urge to rephrase the question or provide the answer yourself.

Scaffold Questions

Break down complex questions into smaller parts to guide student thinking while still encouraging them to do the intellectual work.

Asking thoughtful, open-ended questions takes practice but is essential for developing critical thinking skills . Start by planning 2-3 higher-order questions for each lesson and focus on truly listening to student responses. Over time, a questioning approach focused on explanation, evidence, and exploration will become second nature.

What is the art of questioning method?

The art of questioning is a teaching technique that focuses on asking strategic questions to promote critical thinking, inquiry, and meaningful learning experiences for students. It is an essential skill for educators to master in order to elicit student understanding and uncover gaps in knowledge.

Some key things to know about the art of questioning:

It checks for understanding and gets insight into students' thought processes. By asking probing questions, teachers can determine if students have truly grasped key concepts.

It activates higher-order thinking skills. Well-designed questions require students to analyze, evaluate, and create, moving beyond basic recall.

It sparks student curiosity and engagement. Thought-provoking questions pique interest in lesson topics.

It facilitates rich class discussions. Using quality questioning techniques lays the foundation for impactful dialogue.

It informs teaching strategies and adaptations. Based on student responses, teachers can clarify misconceptions or adjust the pace/complexity of lessons.

Mastering the art of questioning takes practice but is worth the effort. It transforms passive learning into an active, student-centered experience that sticks. Equipped with this vital skill, teachers can maximize critical thinking and inquiry-based learning in their classrooms.

What are the 4 main questioning techniques?

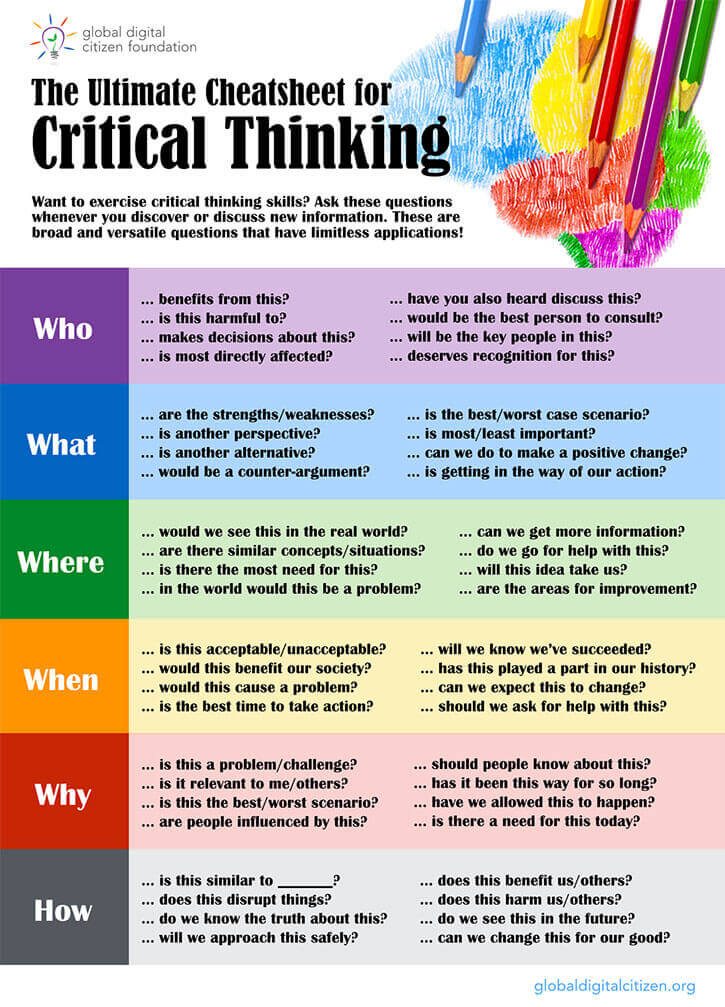

Teachers can utilize four key questioning techniques to promote critical thinking and inquiry in the classroom:

Closed Questions

Closed questions typically require short or one-word answers. They are useful for:

- Checking for understanding

- Getting students to state facts

- Reviewing material

For example, "What year did World War 2 begin?"

Open Questions

Open questions require more elaborate responses. They are effective for:

- Encouraging discussion

- Extracting deeper thinking

- Allowing students to explain concepts

For instance, "How did the Great Depression impact American society?"

Funnel Questions

Funnel questions start broad and become increasingly specific. This technique:

- Prompts recall of contextual details

- Guides students step-by-step

- Focuses thinking

An example is, "What do you know about World War 2? What were the key events leading up to it? What specific decisions by world leaders contributed to its outbreak?"

Probing Questions

Probing questions request clarification or more information. They help to:

- Draw out additional details

- Test the strength of an argument

- Determine accuracy and depth of understanding

For example, "You mentioned the Great Depression caused widespread poverty. Can you expand on the ways it impacted day-to-day life?"

Using a mix of these four questioning techniques can elicit thoughtful participation and allow teachers to effectively gauge comprehension.

sbb-itb-bb2be89

Exploring types of art of questioning.

Art of questioning refers to the teacher's ability to ask thoughtful, open-ended questions that promote critical thinking, inquiry, and engagement among students. Here we explore some key categories of questions that go beyond basic fact recall to stimulate deeper learning.

Open-Ended Questions to Foster Inquiry

Open-ended questions have no single right answer, allowing students to respond creatively within their current knowledge and experiences. Some examples:

- What do you think would happen if...?

- How might we go about solving this problem?

- What are some possible explanations for...?

Guidelines for open-ended questions:

- Ask about hypothetical situations or predictions

- Inquire about students' thought processes or reasoning

- Seek multiple diverse responses to broad issues

Probing Questions to Assess Prior Knowledge

Probing questions aim to uncover and expand upon students' existing knowledge. For instance:

- What do you already know about this topic?

- Can you explain your solution further?

Tips for probing questions:

- Ask students to elaborate or clarify their responses

- Dig deeper into the reasons behind their ideas

- Gauge their current level of understanding on a topic

Hypothetical & Speculative Questions for Mental Activity

Hypothetical and speculative questions require students to mentally engage with imaginative or puzzling scenarios. Examples:

- What do you imagine this character is thinking/feeling?

- If you could travel anywhere, where would you go?

- What might the world look like 100 years from now?

Strategies using speculative questions:

- Present imaginary situations

- Ask about unlikely or fantastical events

- Inquire about hopes, wonders, or puzzles

Synthesis & Evaluation Questions to Enhance Critical Thinking

Higher-order questions push students to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information. For example:

- How would you compare and contrast these two stories?

- What evidence supports or contradicts this conclusion?

- What changes would you suggest to improve this process?

Techniques for using synthesis questions:

- Ask students to make connections between ideas

- Require them to assess credibility and logical consistency

- Prompt them to create novel solutions based on analysis

Thoughtful questioning is invaluable for engaging students, inspiring deeper thinking, assessing understanding, and taking learning to the next level. Match question types to desired educational outcomes.

Effective Timing and Application of Questioning Techniques

Utilizing zones of proximal development at the beginning of lesson.

At the start of a lesson, it's important to assess students' prior knowledge and understanding within their zones of proximal development. Open-ended questions that require some thought and analysis work well here, such as "What do you already know about this topic?" or "How might this connect to what we learned previously?". Allowing some think time and using gentle probing follow-ups can uncover gaps and misconceptions to address.

During Instruction: Encouraging Active Participation

While teaching new material, questions should regularly check comprehension and spur examination of ideas. "Why" and "how" questions prompt students to articulate concepts in their own words, while think-pair-share structures promote participation. Allow just enough wait time for students to gather thoughts before cold-calling. Ask students to summarize key points or apply them in novel contexts. Maintain an encouraging tone and affirm effort.

End-of-Lesson Evaluations and Inquiry

Conclude by synthesizing main points and addressing lingering questions. Open-ended questions like "What are you still wondering about?" give quieter students a chance to share. Exit tickets, short reflective writing assignments, also stimulate additional inquiry. Follow-up questions based on student responses facilitate rich discussion. Affirm participation and remind students that lingering questions present opportunities for future investigation.

Art of Questioning Activities and Games

Think-pair-share and other participatory activities.

The think-pair-share approach provides an excellent framework for questioning techniques. Students are first asked to independently think about a question or problem. They then discuss their ideas in pairs, encouraging participation from every student before ideas are shared with the whole class. Variations like think-write-pair-share add a writing component for reflection. These participatory structures promote critical thinking and inquiry through peer discussion.

Question Cycles for Continuous Learning Experience

Using a series of interrelated questions on a topic creates continuity in the learning experience. Starting with simpler questions then building up to more complex, higher-order questions logically develops student understanding. Question cycles enable connecting new information to prior knowledge, unpacking ideas, applying concepts, making evaluations, and synthesizing learning. This technique ensures questioning sequentially builds up rather than occurring in isolation.

Socratic Questioning to Challenge Theory of Mind

The Socratic method uses questioning to draw out ideas and uncover assumptions. Teachers can play "devil's advocate" to challenge students' thought processes. This develops theory of mind as students learn to see other perspectives. Socratic questioning teaches the value of intellectual humility and deep thinking. Example questions include "What do you mean when you say...?", "What evidence supports that?", "How does this tie into our earlier discussion?"

Interactive Questioning Games to Engage Students

Games put questioning techniques into action while engaging students. Examples include Quiz-Quiz-Trade with student-created questions, Question Rally with teams answering on whiteboards, Question Cards with written responses, and Question Dice promoting discussion. These games leverage friendly competition and peer involvement to motivate learning through questioning. The interactive format promotes enjoyment, attention, and participation.

Assessing the Objectives and Impact of Questioning Techniques

Developing questioning rubrics aligned with objectives.

Rubrics can be a useful tool for assessing questioning techniques and alignment with learning objectives. When developing a rubric, key aspects to consider include:

- Types of questions asked - Factual, convergent, divergent, evaluative, etc.

- Cognitive level of questions - Remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, create

- Scaffolding and sequencing of questions

- Linkage to lesson objectives and goals

- Student engagement and participation

The rubric can include rating scales or descriptors across these dimensions to evaluate the art of questioning. Teachers can use the rubric for self-assessment or be observed and evaluated by others.

Gathering Insights Through Student Feedback Surveys

Conducting periodic student surveys can provide valuable perceptions into questioning approaches. Useful survey questions may cover:

- Comfort and willingness to respond to questions

- Perceived relevance of questions to learning goals

- Role of questions in promoting thinking and understanding

- Suggestions for improvement

Analyzing survey results over time can indicate whether shifts in questioning techniques have positively influenced the learning experience.

Measuring Growth in Critical Thinking with Assessments

Assessments focused on critical thinking skills can gauge the impact of improved questioning. These may include:

- Essay prompts and open-ended questions

- Scenarios to analyze that require evaluation, synthesis and creative solutions

- Individual or group projects necessitating inquiry and investigation

- Presentations demonstrating deep understanding

Comparing baseline to post-intervention assessments can quantify if questioning strategies have successfully developed critical thinking capacities.

Participatory Action Research for Professional Development

Teachers can engage in participatory action research by:

- Recording lessons and categorizing types/cognitive levels of questions asked

- Soliciting peer or mentor feedback on questioning approaches

- Setting goals for improvement and tracking progress

- Iteratively refining techniques based on evidence and collaboration

This process facilitates continuous growth and allows networking with a community of practice.

Building a Community of Practice Through Questioning

Fostering collaborative environments where educators can share best practices in questioning techniques is key to building a strong community of practice focused on the art of questioning. By creating opportunities for continuous learning and adaptation, educators can work together to advance their skills.

Fostering Collaborative Environments

- Establish routines for educators to observe each other's classrooms and provide feedback on questioning strategies

- Organize professional learning groups for educators to collaborate on developing effective questions

- Create shared online spaces for educators to exchange ideas on the art of questioning

- Promote a growth mindset culture that values inquiry and critical feedback

Sharing Best Practices in Questioning

- Host workshops for educators to demonstrate questioning techniques and activities

- Publish videos/documents highlighting examples of impactful questioning strategies in action

- Maintain forums for educators to post questions and get input from colleagues

- Enable educators to share lesson plans centered around critical thinking questions

- Encourage educators to exchange ideas on adapting questioning for different subjects

Continuous Learning and Adaptation

- Survey educators regularly on evolving needs related to questioning techniques

- Provide ongoing professional development on emerging best practices in questioning

- Establish mentoring programs for new educators to get support in questioning skills

- Promote reflection techniques for educators to assess their questioning methods

- Foster a culture of critical inquiry where questioning practices continuously improve

By taking a collaborative, growth-focused approach to the art of questioning, educators can work together in communities of practice to advance their skills and create vibrant cultures of learning in their classrooms.

Conclusion: Synthesizing the Art of Questioning for Educational Excellence

The art of questioning is a critical skill that all educators should develop. By mastering various techniques that promote critical thinking and inquiry, teachers can stimulate rich discussion, facilitate deeper learning, and empower students to analyze information.

Here are some key takeaways:

Asking open-ended questions is key to sparking curiosity and prompting students to think more critically. Closed-ended questions that have yes/no answers should be used sparingly.

Mix lower and higher-order questions. Lower-order questions assess basic understanding while higher-order questions require evaluation, synthesis and analysis.

Allow adequate wait time between questions. Give students sufficient time to process the question and develop thoughtful responses.

Scaffold complex questions by building on students' prior knowledge. Connect new ideas to concepts already familiar to them.

Encourage participation from all students with inclusive questioning strategies. Consider think-pair-share methods.

Use prompting and probing techniques to extend dialogue. Ask follow-up questions to clarify, provide evidence or expand on initial responses.

By honing expertise in thoughtful inquiry-based questioning, educators can unlock their students' potential for critical thought while creating engaging, student-centered learning environments. Continual development through communities of practice, action research and other forms of professional development can help perfect this invaluable teaching skill.

Related posts

- The Socratic Method: Engaging Students in Critical Thinking and Dialogue

- Teaching Resources for Teachers: Cultivate Critical Thinking

- Cultivating Creativity: Innovative Approaches to Encouraging Student Imagination

- How to Develop Critical Thinking Skills in Students

Integrating Technology in Learning: Tools and Tips for Modern Educators

How to adress bullying in the classroom

Addressing Bullying: Roles and Responsibilities

Become a buddy..

Join 500+ teachers getting free goodies every week. 📚

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Critical Thinking Is About Asking Better Questions

- John Coleman

Six practices to sharpen your inquiry.

Critical thinking is the ability to analyze and effectively break down an issue in order to make a decision or find a solution. At the heart of critical thinking is the ability to formulate deep, different, and effective questions. For effective questioning, start by holding your hypotheses loosely. Be willing to fundamentally reconsider your initial conclusions — and do so without defensiveness. Second, listen more than you talk through active listening. Third, leave your queries open-ended, and avoid yes-or-no questions. Fourth, consider the counterintuitive to avoid falling into groupthink. Fifth, take the time to stew in a problem, rather than making decisions unnecessarily quickly. Last, ask thoughtful, even difficult, follow-ups.

Are you tackling a new and difficult problem at work? Recently promoted and trying to both understand your new role and bring a fresh perspective? Or are you new to the workforce and seeking ways to meaningfully contribute alongside your more experienced colleagues? If so, critical thinking — the ability to analyze and effectively break down an issue in order to make a decision or find a solution — will be core to your success. And at the heart of critical thinking is the ability to formulate deep, different, and effective questions.

- JC John Coleman is the author of the HBR Guide to Crafting Your Purpose . Subscribe to his free newsletter, On Purpose , follow him on Twitter @johnwcoleman, or contact him at johnwilliamcoleman.com.

Partner Center

- Open access

- Published: 11 September 2019

Inquiry and critical thinking skills for the next generation: from artificial intelligence back to human intelligence

- Jonathan Michael Spector ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6270-3073 1 &

- Shanshan Ma 1

Smart Learning Environments volume 6 , Article number: 8 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

33k Accesses

59 Citations

32 Altmetric

Metrics details

Along with the increasing attention to artificial intelligence (AI), renewed emphasis or reflection on human intelligence (HI) is appearing in many places and at multiple levels. One of the foci is critical thinking. Critical thinking is one of four key 21st century skills – communication, collaboration, critical thinking and creativity. Though most people are aware of the value of critical thinking, it lacks emphasis in curricula. In this paper, we present a comprehensive definition of critical thinking that ranges from observation and inquiry to argumentation and reflection. Given a broad conception of critical thinking, a developmental approach beginning with children is suggested as a way to help develop critical thinking habits of mind. The conclusion of this analysis is that more emphasis should be placed on developing human intelligence, especially in young children and with the support of artificial intelligence. While much funding and support goes to the development of artificial intelligence, this should not happen at the expense of human intelligence. Overall, the purpose of this paper is to argue for more attention to the development of human intelligence with an emphasis on critical thinking.

Introduction

In recent decades, advancements in Artificial Intelligence (AI) have developed at an incredible rate. AI has penetrated into people’s daily life on a variety of levels such as smart homes, personalized healthcare, security systems, self-service stores, and online shopping. One notable AI achievement was when AlphaGo, a computer program, defeated the World Go Champion Mr. Lee Sedol in 2016. In the previous year, AlphaGo won in a competition against a professional Go player (Silver et al. 2016 ). As Go is one of the most challenging games, the wins of AI indicated a breakthrough. Public attention has been further drawn to AI since then, and AlphaGo continues to improve. In 2017, a new version of AlphaGo beat Ke Jie, the current world No.1 ranking Go player. Clearly AI can manage high levels of complexity.

Given many changes and multiple lines of development and implement, it is somewhat difficult to define AI to include all of the changes since the 1980s (Luckin et al. 2016 ). Many definitions incorporate two dimensions as a starting point: (a) human-like thinking, and (b) rational action (Russell and Norvig 2009 ). Basically, AI is a term used to label machines (computers) that imitate human cognitive functions such as learning and problem solving, or that manage to deal with complexity as well as human experts.

AlphaGo’s wins against human players were seen as a comparison between artificial and human intelligence. One concern is that AI has already surpassed HI; other concerns are that AI will replace humans in some settings or that AI will become uncontrollable (Epstein 2016 ; Fang et al. 2018 ). Scholars worry that AI technology in the future might trigger the singularity (Good 1966 ), a hypothesized future that the development of technology becomes uncontrollable and irreversible, resulting in unfathomable changes to human civilization (Vinge 1993 ).

The famous theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking warned that AI might end mankind, yet the technology he used to communicate involved a basic form of AI (Cellan-Jones 2014 ). This example highlights one of the basic dilemmas of AI – namely, what are the overall benefits of AI versus its potential drawbacks, and how to move forward given its rapid development? Obviously, basic or controllable AI technologies are not what people are afraid of. Spector et al. 1993 distinguished strong AI and weak AI. Strong AI involves an application that is intended to replace an activity performed previously by a competent human, while weak AI involves an application that aims to enable a less experienced human to perform at a much higher level. Other researchers categorize AI into three levels: (a) artificial narrow intelligence (Narrow AI), (b) artificial general intelligence (General AI), and (c) artificial super intelligence (Super AI) (Siau and Yang 2017 ; Zhang and Xie 2018 ). Narrow AI, sometimes called weak AI, refers to a computer that focus on a narrow task such as AlphaZero or a self-driving car. General AI, sometimes referred to as strong AI, is the simulation of human-level intelligence, which can perform more cognitive tasks as well as most humans do. Super AI is defined by Bostrom ( 1998 ) as “an intellect that is much smarter than the best human brains in practically every field, including scientific creativity, general wisdom and social skills” (p.1).

Although the consequence of singularity and its potential benefits or harm to the human race have been intensely debated, an undeniable fact is that AI is capable of undertaking recursive self-improvement. With the increasing improvement of this capability, more intelligent generations of AI will appear rapidly. On the other hand, HI has its own limits and its development requires continuous efforts and investment from generation to generation. Education is the main approach humans use to develop and improve HI. Given the extraordinary growth gap between AI and HI, eventually AI can surpass HI. However, that is no reason to neglect the development and improvement of HI. In addition, in contrast to the slow development rate of HI, the growth of funding support to AI has been rapidly increasing according to the following comparison of support for artificial and human intelligence.

The funding support for artificial and human intelligence

There are challenges in comparing artificial and human intelligence by identifying funding for both. Both terms are somewhat vague and can include a variety of aspects. Some analyses will include big data and data analytics within the sphere of artificial intelligence and others will treat them separately. Some will include early childhood developmental research within the sphere of support for HI and others treat them separately. Education is a major way of human beings to develop and improve HI. The investments in education reflect the efforts put on the development of HI, and they pale in comparison with investments in AI.

Sources also vary from governmental funding of research and development to business and industry investments in related research and development. Nonetheless, there are strong indications of increased funding support for AI in North America, Europe and Asia, especially in China. The growth in funding for AI around the world is explosive. According to ZDNet, AI funding more than doubled from 2016 to 2017 and more than tripled from 2016 to 2018. The growth in funding for AI in the last 10 years has been exponential. According to Venture Scanner, there are approximately 2500 companies that have raised $60 billion in funding from 3400 investors in 72 different countries (see https://www.slideshare.net/venturescanner/artificial-intelligence-q1-2019-report-highlights ). Areas included in the Venture Scanner analysis included virtual assistants, recommendation engines, video recognition, context-aware computing, speech recognition, natural language processing, machine learning, and more.

The above data on AI funding focuses primarily on companies making products. There is no direct counterpart in the area of HI where the emphasis is on learning and education. What can be seen, however, are trends within each area. The above data suggest exponential growth in support for AI. In contrast, according to the Urban Institute, per-student funding in the USA has been relatively flat for nearly two decades, with a few states showing modest increases and others showing none (see http://apps.urban.org/features/education-funding-trends/ ). Funding for education is complicated due to the various sources. In the USA, there are local, state and federal sources to consider. While that mixture of funding sources is complex, it is clear that federal and state spending for education in the USA experienced an increase after World War II. However, since the 1980s, federal spending for education has steadily declined, and state spending on education in most states has declined since 2010 according to a government report (see https://www.usgovernmentspending.com/education_spending ). This decline in funding reflects the decreasing emphasis on the development of HI, which is a dangerous signal.

Decreased support for education funding in the USA is not typical of what is happening in other countries, according to The Hechinger Report (see https://hechingerreport.org/rest-world-invests-education-u-s-spends-less/ ). For example, in the period of 2010 to 2014, American spending on elementary and high school education declined 3%, whereas in the same period, education spending in the 35 countries in the OECD rose by 5% with some countries experiencing very significant increases (e.g., 76% in Turkey).

Such data can be questioned in terms of how effectively funds are being spent or how poorly a country was doing prior to experiencing a significant increase. However, given the performance of American students on the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), the relative lack of funding support in the USA is roughly related with the mediocre performance on PISA tests (see https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/pisa/pisa2015/index.asp ). Research by Darling-Hammond ( 2014 ) indicated that in order to improve learning and reduce the achievement gap, systematic government investments in high-need schools would be more effective if the focus was on capacity building, improving the knowledge and skills of educators and the quality of curriculum opportunities.

Though HI could not be simply defined by the performance on PISA test, improving HI requires systematic efforts and funding support in high-need areas as well. So, in the following section, we present a reflection on HI.

Reflection on human intelligence

Though there is a variety of definitions of HI, from the perspective of psychology, according to Sternberg ( 1999 ), intelligence is a form of developing expertise, from a novice or less experienced person to an expert or more experienced person, a student must be through multiple learning (implicit and explicit) and thinking (critical and creative) processes. In this paper, we adopted such a view and reflected on HI in the following section by discussing learning and critical thinking.

What is learning?

We begin with Gagné’s ( 1985 ) definition of learning as characterized by stable and persistent changes in what a person knows or can do. How do humans learn? Do you recall how to prove that the square root of 2 is not a rational number, something you might have learned years ago? The method is intriguing and is called an indirect proof or a reduction to absurdity – assume that the square root of 2 is a rational number and then apply truth preserving rules to arrive at a contradiction to show that the square root of 2 cannot be a rational number. We recommend this as an exercise for those readers who have never encountered that method of learning and proof. (see https://artofproblemsolving.com/wiki/index.php/Proof_by_contradiction ). Yet another interesting method of learning is called the process of elimination, sometimes accredited to Arthur Conan Doyle’s ( 1926 ) in The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier – Sherlock Holmes says to Dr. Watson that the process of elimination “starts upon the supposition that when you have eliminated all which is impossible, that whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth ” (see https://www.dfw-sherlock.org/uploads/3/7/3/8/37380505/1926_november_the_adventure_of_the_blanched_soldier.pdf ).

The reason to mention Sherlock Holmes early in this paper is to emphasize the role that observation plays in learning. The character Sherlock Holmes was famous for his observation skills that led to his so-called method of deductive reasoning (a process of elimination), which is what logicians would classify as inductive reasoning as the conclusions of that reasoning process are primarily probabilistic rather than certain, unlike the proof of the irrationality of the square root of 2 mentioned previously.

In dealing with uncertainty, it seems necessary to make observations and gather evidence that can lead one to a likely conclusion. Is that not what reasonable people and accomplished detectives do? It is certainly what card counters do at gambling houses; they observe high and low value cards that have already been played in order to estimate the likelihood of the next card being a high or low value card. Observation is a critical process in dealing with uncertainty.

Moreover, humans typically encounter many uncertain situations in the course of life. Few people encounter situations which require resolution using a mathematical proof such as the one with which this article began. Jonassen ( 2000 , 2011 ) argued that problem solving is one of the most important and frequent activities in which people engage. Moreover, many of the more challenging problems are ill-structured in the sense that (a) there is incomplete information pertaining to the situation, or (b) the ideal resolution of the problem is unknown, or (c) how to transform a problematic situation into an acceptable situation is unclear. In short, people are confronted with uncertainty nearly every day and in many different ways. The so called key 21st century skills of communication, collaboration, critical thinking and creativity (the 4 Cs; see http://www.battelleforkids.org/networks/p21 ) are important because uncertainty is a natural and inescapable aspect of the human condition. The 4 Cs are interrelated and have been presented by Spector ( 2018 ) as interrelated capabilities involving logic and epistemology in the form of the new 3Rs – namely, re-examining, reasoning, and reflecting. Re-examining is directly linked to observation as a beginning point for inquiry. The method of elimination is one form of reasoning in which a person engages to solve challenging problems. Reflecting on how well one is doing in the life-long enterprise of solving challenging problems is a higher kind of meta-cognitive activity in which accomplished problem-solvers engage (Ericsson et al. 1993 ; Flavell 1979 ).

Based on these initial comments, a comprehensive definition of critical thinking is presented next in the form of a framework.

A framework of critical thinking

Though there is variety of definitions of critical thinking, a concise definition of critical thinking remains elusive. For delivering a direct understanding of critical thinking to readers such as parents and school teachers, in this paper, we present a comprehensive definition of critical thinking through a framework that includes many of the definitions offered by others. Critical thinking, as treated broadly herein, is a multi-dimensioned and multifaceted human capability. Critical thinking has been interpreted from three perspectives: education, psychology, and epistemology, all of which are represented in the framework that follows.

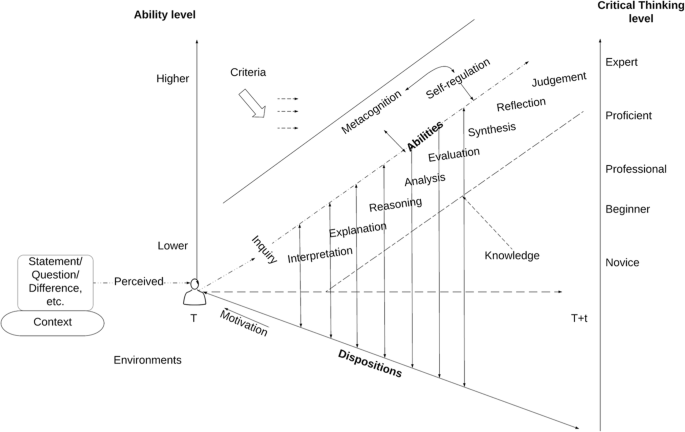

In a developmental approach to critical thinking, Spector ( 2019 ) argues that critical thinking involves a series of cumulative and related abilities, dispositions and other variables (e.g., motivation, criteria, context, knowledge). This approach proceeds from experience (e.g., observing something unusual) and then to various forms of inquiry, investigation, examination of evidence, exploration of alternatives, argumentation, testing conclusions, rethinking assumptions, and reflecting on the entire process.

Experience and engagement are ongoing throughout the process which proceeds from relatively simple experiences (e.g., direct and immediate observation) to more complex interactions (e.g., manipulation of an actual or virtual artifact and observing effects).

The developmental approach involves a variety of mental processes and non-cognitive states, which help a person’s decision making to become purposeful and goal directed. The associated critical thinking skills enable individuals to be likely to achieve a desired outcome in a challenging situation.

In the process of critical thinking, apart from experience, there are two additional cognitive capabilities essential to critical thinking – namely, metacognition and self-regulation . Many researchers (e.g., Schraw et al. 2006 ) believe that metacognition has two components: (a) awareness and understanding of one’s own thoughts, and (b) the ability to regulate one’s own cognitive processes. Some other researchers put more emphasis on the latter component. For example, Davies ( 2015 ) described metacognition as the capacity to monitor the quality of one’s thinking process, and then to make appropriate changes. However, the American Psychology Association (APA) defines metacognition as an awareness and understanding of one’s own thought with the ability to control related cognitive processes (see https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-15725-005 ).

Although the definition and elaboration of these two concepts deserve further exploration, they are often used interchangeably (Hofer and Sinatra 2010 ; Schunk 2008 ). Many psychologists see the two related capabilities of metacognition and self-regulation as being closely related - two sides on one coin, so to speak. Metacognition involves or emphasizes awareness, whereas self-regulation involves and emphasizes appropriate control. These two concepts taken together enable a person to create a self-regulatory mechanism, which monitors and regulates the corresponding skills (e.g., observation, inquiry, interpretation, explanation, reasoning, analysis, evaluation, synthesis, reflection, and judgement).

As to the critical thinking skills, it should be noted that there is much discussion about the generalizability and domain specificity of them, just as there is about problem-solving skills in general (Chi et al. 1982 ; Chiesi et al. 1979 ; Ennis 1989 ; Fischer 1980 ). The research supports the notion that to achieve high levels of expertise and performance, one must develop high levels of domain knowledge. As a consequence, becoming a highly effective critical thinker in a particular domain of inquiry requires significant domain knowledge. One may achieve such levels in a domain in which one has significant domain knowledge and experience but not in a different domain in which one has little domain knowledge and experience. The processes involved in developing high levels of critical thinking are somewhat generic. Therefore, it is possible to develop critical thinking in nearly any domain when the two additional capabilities of metacognition and self-regulation are coupled with motivation and engagement and supportive emotional states (Ericsson et al. 1993 ).

Consequently, the framework presented here (see Fig. 1 ) is built around three main perspectives about critical thinking (i.e., educational, psychological and epistemological) and relevant learning theories. This framework provides a visual presentation of critical thinking with four dimensions: abilities (educational perspective), dispositions (psychological perspective), levels (epistemological perspective) and time. Time is added to emphasize the dynamic nature of critical thinking in terms of a specific context and a developmental approach.

Critical thinking often begins with simple experiences such as observing a difference, encountering a puzzling question or problem, questioning someone’s statement, and then leads, in some instances to an inquiry, and then to more complex experiences such as interactions and application of higher order thinking skills (e.g., logical reasoning, questioning assumptions, considering and evaluating alternative explanations).

If the individual is not interested in what was observed, an inquiry typically does not begin. Inquiry and critical thinking require motivation along with an inquisitive disposition. The process of critical thinking requires the support of corresponding internal indispositions such as open-mindedness and truth-seeking. Consequently, a disposition to initiate an inquiry (e.g., curiosity) along with an internal inquisitive disposition (e.g., that links a mental habit to something motivating to the individual) are both required (Hitchcock 2018 ). Initiating dispositions are those that contribute to the start of inquiry and critical thinking. Internal dispositions are those that initiate and support corresponding critical thinking skills during the process. Therefore, critical thinking dispositions consist of initiating dispositions and internal dispositions. Besides these factors, critical thinking also involves motivation. Motivation and dispositions are not mutually exclusive, for example, curiosity is a disposition and also a motivation.

Critical thinking abilities and dispositions are two main components of critical thinking, which involve such interrelated cognitive constructs as interpretation, explanation, reasoning, evaluation, synthesis, reflection, judgement, metacognition and self-regulation (Dwyer et al. 2014 ; Davies 2015 ; Ennis 2018 ; Facione 1990 ; Hitchcock 2018 ; Paul and Elder 2006 ). There are also some other abilities such as communication, collaboration and creativity, which are now essential in current society (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/21st_century_skills ). Those abilities along with critical thinking are called the 4Cs; they are individually monitored and regulated through metacognitive and self-regulation processes.

The abilities involved in critical thinking are categorized in Bloom’s taxonomy into higher order skills (e.g., analyzing and synthesizing) and lower level skills (e.g., remembering and applying) (Anderson and Krathwohl 2001 ; Bloom et al. 1956 ).

The thinking process can be depicted as a spiral through both lower and higher order thinking skills. It encompasses several reasoning loops. Some of them might be iterative until a desired outcome is achieved. Each loop might be a mix of higher order thinking skills and lower level thinking skills. Each loop is subject to the self-regulatory mechanism of metacognition and self-regulation.

But, due to the complexity of human thinking, a specific spiral with reasoning loops is difficult to represent. Therefore, instead of a visualized spiral with an indefinite number of reasoning loops, the developmental stages of critical thinking are presented in the diagram (Fig. 1 ).

Besides, most of the definitions of critical thinking are based on the imagination about ideal critical thinkers such as the consensus generated from the Delphi report (Facione 1990 ). However, according to Dreyfus and Dreyfus ( 1980 ), in the course of developing an expertise, students would pass through five stages. Those five stages are “absolute beginner”, “advanced beginner”, “competent performer”, “proficient performer,” and “intuitive expert performer”. Dreyfus and Dreyfus ( 1980 ) described the five stages the result of the successive transformations of four mental functions: recollection, recognition, decision making, and awareness.

In the course of developing critical thinking and expertise, individuals will pass through similar stages which are accompanied with the increasing practices and accumulation of experience. Through the intervention and experience of developing critical thinking, as a novice, tasks are decomposed into context-free features which could be recognized by students without the experience of particular situations. For further improving, students need to be able to monitor their awareness, and with a considerable experience. They can note recurrent meaningful component patterns in some contexts. Gradually, increased practices expose students to a variety of whole situations which enable the students to recognize tasks in a more holistic manner as a professional. On the other hand, with the increasing accumulation of experience, individuals are less likely to depend simply on abstract principles. The decision will turn to something intuitive and highly situational as well as analytical. Students might unconsciously apply rules, principles or abilities. A high level of awareness is absorbed. At this stage, critical thinking is turned into habits of mind and in some cases expertise. The description above presents a process of critical thinking development evolving from a novice to an expert, eventually developing critical thinking into habits of mind.

We mention the five-stage model proposed by Dreyfus and Dreyfus ( 1980 ) to categorize levels of critical thinking and emphasize the developmental nature involved in becoming a critical thinker. Correspondingly, critical thinking is categorized into 5 levels: absolute beginner (novice), advanced beginner (beginner), competent performer (competent), proficient performer (proficient), and intuitive expert (expert).

Ability level and critical thinker (critical thinking) level together represent one of the four dimensions represented in Fig. 1 .

In addition, it is noteworthy that the other two elements of critical thinking are the context and knowledge in which the inquiry is based. Contextual and domain knowledge must be taken into account with regard to critical thinking, as previously argued. Besides, as Hitchcock ( 2018 ) argued, effective critical thinking requires knowledge about and experience applying critical thinking concepts and principles as well.

Critical thinking is considered valuable across disciplines. But except few courses such as philosophy, critical thinking is reported lacking in most school education. Most of researchers and educators thus proclaim that integrating critical thinking across the curriculum (Hatcher 2013 ). For example, Ennis ( 2018 ) provided a vision about incorporating critical thinking across the curriculum in higher education. Though people are aware of the value of critical thinking, few of them practice it. Between 2012 and 2015, in Australia, the demand of critical thinking as one of the enterprise skills for early-career job increased 125% (Statista Research Department, 2016). According to a survey across 1000 adults by The Reboot Foundation 2018 , more than 80% of respondents believed that critical thinking skills are lacking in today’s youth. Respondents were deeply concerned that schools do not teach critical thinking. Besides, the investigation also found that respondents were split over when and how to teach critical thinking, clearly.

In the previous analysis of critical thinking, we presented the mechanism of critical thinking instead of a concise definition. This is because, given the various perspectives of interpreting critical thinking, it is not easy to come out with an unitary definition, but it is essential for the public to understand how critical thinking works, the elements it involves and the relationships between them, so they can achieve an explicit understanding.

In the framework, critical thinking starts from simple experience such as observing a difference, then entering the stage of inquiry, inquiry does not necessarily turn the thinking process into critical thinking unless the student enters a higher level of thinking process or reasoning loops such as re-examining, reasoning, reflection (3Rs). Being an ideal critical thinker (or an expert) requires efforts and time.

According to the framework, simple abilities such as observational skills and inquiry are indispensable to lead to critical thinking, which suggests that paying attention to those simple skills at an early stage of children can be an entry point to critical thinking. Considering the child development theory by Piaget ( 1964 ), a developmental approach spanning multiple years can be employed to help children develop critical thinking at each corresponding development stage until critical thinking becomes habits of mind.

Although we emphasized critical thinking in this paper, for the improvement of intelligence, creative thinking and critical thinking are separable, they are both essential abilities that develop expertise, eventually drive the improvement of HI at human race level.

As previously argued, there is a similar pattern among students who think critically in different domains, but students from different domains might perform differently in creativity because of different thinking styles (Haller and Courvoisier 2010 ). Plus, students have different learning styles and preferences. Personalized learning has been the most appropriate approach to address those differences. Though the way of realizing personalized learning varies along with the development of technologies. Generally, personalized learning aims at customizing learning to accommodate diverse students based on their strengths, needs, interests, preferences, and abilities.

Meanwhile, the advancement of technology including AI is revolutionizing education; students’ learning environments are shifting from technology-enhanced learning environments to smart learning environments. Although lots of potentials are unrealized yet (Spector 2016 ), the so-called smart learning environments rely more on the support of AI technology such as neural networks, learning analytics and natural language processing. Personalized learning is better supported and realized in a smart learning environment. In short, in the current era, personalized learning is to use AI to help learners perform at a higher level making adjustments based on differences of learners. This is the notion with which we conclude – the future lies in using AI to improve HI and accommodating individual differences.

The application of AI in education has been a subject for decades. There are efforts heading to such a direction though personalized learning is not technically involved in them. For example, using AI technology to stimulate critical thinking (Zhu 2015 ), applying a virtual environment for building and assessing higher order inquiry skills (Ketelhut et al. 2010 ). Developing computational thinking through robotics (Angeli and Valanides 2019 ) is another such promising application of AI to support the development of HI.

However, almost all of those efforts are limited to laboratory experiments. For accelerating the development rate of HI, we argue that more emphasis should be given to the development of HI at scale with the support of AI, especially in young children focusing on critical and creative thinking.

In this paper, we argue that more emphasis should be given to HI development. Rather than decreasing the funding of AI, the analysis of progress in artificial and human intelligence indicates that it would be reasonable to see increased emphasis placed on using various AI techniques and technologies to improve HI on a large and sustainable scale. Well, most researchers might agree that AI techniques or the situation might be not mature enough to support such a large-scale development. But it would be dangerous if HI development is overlooked. Based on research and theory drawn from psychology as well as from epistemology, the framework is intended to provide a practical guide to the progressive development of inquiry and critical thinking skills in young children as children represent the future of our fragile planet. And we suggested a sustainable development approach for developing inquiry and critical thinking (See, Spector 2019 ). Such an approach could be realized through AI and infused into HI development. Besides, a project is underway in collaboration with NetDragon to develop gamified applications to develop the relevant skills and habits of mind. A game-based assessment methodology is being developed and tested at East China Normal University that is appropriate for middle school children. The intention of the effort is to refocus some of the attention on the development of HI in young children.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Artificial Intelligence

Human Intelligence

L.W. Anderson, D.R. Krathwohl, A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (Allyn & Bacon, Boston, 2001)

Google Scholar

Angeli, C., & Valanides, N. (2019). Developing young children’s computational thinking with educational robotics: An interaction effect between gender and scaffolding strategy. Comput. Hum. Behav. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.018

B.S. Bloom, M.D. Engelhart, E.J. Furst, W.H. Hill, D.R. Krathwohl, Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain (David McKay Company, New York, 1956)

Bostrom, N. (1998). How long before superintelligence? Retrieved from https://nickbostrom.com/superintelligence.html

R. Cellan-Jones, Stephen hawking warns artificial intelligence could end mankind. BBC. News. 2 , 2014 (2014)

M.T.H. Chi, R. Glaser, E. Rees, in Advances in the Psychology of Human Intelligence , ed. by R. S. Sternberg. Expertise in problem solving (Erlbaum, Hillsdale, 1982), pp. 7–77

H.L. Chiesi, G.J. Spliich, J.F. Voss, Acquisition of domain-related information in relation to high and low domain knowledge. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 18 , 257–273 (1979)

Article Google Scholar

L. Darling-Hammond, What can PISA tell US about US education policy? N. Engl. J. Publ. Policy. 26 (1), 4 (2014)

M. Davies, in Higher education: Handbook of theory and research . A Model of Critical Thinking in Higher Education (Springer, Cham, 2015), pp. 41–92

Chapter Google Scholar

A.C. Doyle, in The Strand Magazine . The adventure of the blanched soldier (1926) Retrieved from https://www.dfw-sherlock.org/uploads/3/7/3/8/37380505/1926_november_the_adventure_of_the_blanched_soldier.pdf

S.E. Dreyfus, H.L. Dreyfus, A five-stage model of the mental activities involved in directed skill acquisition (no. ORC-80-2) (University of California-Berkeley Operations Research Center, Berkeley, 1980)

Book Google Scholar

C.P. Dwyer, M.J. Hogan, I. Stewart, An integrated critical thinking framework for the 21st century. Think. Skills Creat. 12 , 43–52 (2014)

R.H. Ennis, Critical thinking and subject specificity: Clarification and needed research. Educ. Res. 18 , 4–10 (1989)

R.H. Ennis, Critical thinking across the curriculum: A vision. Topoi. 37 (1), 165–184 (2018)

Epstein, Z. (2016). Has artificial intelligence already surpassed the human brain? Retrieved from https://bgr.com/2016/03/10/alphago-beats-lee-sedol-again/

K.A. Ericsson, R.T. Krampe, C. Tesch-Römer, The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol. Rev. 100 (3), 363–406 (1993)

Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction [Report for the American Psychology Association]. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED315423.pdf

J. Fang, H. Su, Y. Xiao, Will Artificial Intelligence Surpass Human Intelligence? (2018). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3173876

K.W. Fischer, A theory of cognitive development: The control and construction of hierarchies of skills. Psychol. Rev. 87 , 477–431 (1980)

J.H. Flavell, Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive development inquiry. Am. Psychol. 34 (10), 906–911 (1979)

R.M. Gagné, The conditions of learning and theory of instruction , 4th edn. (Holt, Rinehart, & Winston, New York, 1985)

I.J. Good, Speculations concerning the first ultraintelligent machine. Adv Comput. 6 , 31-88 (1966)

C.S. Haller, D.S. Courvoisier, Personality and thinking style in different creative domains. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts. 4 (3), 149 (2010)

D.L. Hatcher, Is critical thinking across the curriculum a plausible goal? OSSA. 69 (2013) Retrieved from https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA10/papersandcommentaries/69

Hitchcock, D. (2018). Critical thinking. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/critical-thinking/

B.K. Hofer, G.M. Sinatra, Epistemology, metacognition, and self-regulation: Musings on an emerging field. Metacogn. Learn. 5 (1), 113–120 (2010)

D.H. Jonassen, Toward a design theory of problem solving. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 48 (4), 63–85 (2000)

D.H. Jonassen, Learning to Solve Problems: A Handbook for Designing Problem-Solving Learning Environments (Routledge, New York, 2011)

D.J. Ketelhut, B.C. Nelson, J. Clarke, C. Dede, A multi-user virtual environment for building and assessing higher order inquiry skills in science. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 41 (1), 56–68 (2010)

R. Luckin, W. Holmes, M. Griffiths, L.B. Forcier, Intelligence Unleashed: An Argument for AI in Education (Pearson Education, London, 2016) Retrieved from http://oro.open.ac.uk/50104/1/Luckin%20et%20al.%20-%202016%20-%20Intelligence%20Unleashed.%20An%20argument%20for%20AI%20in%20Educ.pdf

R. Paul, L. Elder, The miniature guide to critical thinking: Concepts and tools , 4th edn. (2006) Retrieved from https://www.criticalthinking.org/files/Concepts_Tools.pdf

J. Piaget, Part I: Cognitive development in children: Piaget development and learning. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2 (3), 176–186 (1964)

S.J. Russell, P. Norvig, Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach , 3rd edn. (Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 2009) ISBN 978-0-136042594

G. Schraw, K.J. Crippen, K. Hartley, Promoting self-regulation in science education: Metacognition as part of a broader perspective on learning. Res. Sci. Educ. 36 (1–2), 111–139 (2006)

D.H. Schunk, Metacognition, self-regulation, and self-regulated learning: Research recommendations. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 20 (4), 463–467 (2008)

K. Siau, Y. Yang, in Twelve Annual Midwest Association for Information Systems Conference (MWAIS 2017) . Impact of artificial intelligence, robotics, and machine learning on sales and marketing (2017), pp. 18–19

D. Silver, A. Huang, C.J. Maddison, A. Guez, L. Sifre, G. Van Den Driessche, et al., Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature. 529 (7587), 484 (2016)

J. M. Spector, M. C. Polson, D. J. Muraida (eds.), Automating Instructional Design: Concepts and Issues (Educational Technology Publications, Englewood Cliffs, 1993)

J.M. Spector, Smart Learning Environments: Concepts and Issues . In G. Chamblee & L. Langub (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 2728–2737). (Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE), Savannah, GA, United States, 2016). Retrieved June 4, 2019 from https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/172078/ .

J. M. Spector, Thinking and learning in the anthropocene: The new 3 Rs . Discussion paper presented at the International Big History Association Conference, Philadelphia, PA (2018). Retrieved from http://learndev.org/dl/HLAIBHA2018/Spector%2C%20J.%20M.%20(2018).%20Thinking%20and%20Learning%20in%20the%20Anthropocene.pdf .

J. M. Spector, Complexity, Inquiry Critical Thinking, and Technology: A Holistic and Developmental Approach . In Mind, Brain and Technology (pp. 17–25). (Springer, Cham, 2019).

R.J. Sternberg, Intelligence as developing expertise. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 24 (4), 359–375 (1999)

The Reboot Foundation. (2018). The State of Critical Thinking: A New Look at Reasoning at Home, School, and Work. Retrieved from https://reboot-foundation.org/wp-content/uploads/_docs/REBOOT_FOUNDATION_WHITE_PAPER.pdf

V. Vinge, The Coming Technological Singularity: How to Survive in the Post-Human Era . Resource document. NASA Technical report server. Retrieved from https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19940022856.pdf . Accessed 20 June 2019.

D. Zhang, M. Xie, Artificial Intelligence’s Digestion and Reconstruction for Humanistic Feelings . In 2018 International Seminar on Education Research and Social Science (ISERSS 2018) (Atlantis Press, Paris, 2018)

X. Zhu, in Twenty-Ninth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence . Machine Teaching: An Inverse Problem to Machine Learning and an Approach toward Optimal Education (2015)

Download references

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the generous support of NetDragon and the Digital Research Centre at the University of North Texas.

Initial work is being funded through the NetDragon Digital Research Centre at the University of North Texas with Author as the Principal Investigator.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Learning Technologies, University of North Texas Denton, Texas, TX, 76207, USA

Jonathan Michael Spector & Shanshan Ma

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to the effort. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jonathan Michael Spector .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Spector, J.M., Ma, S. Inquiry and critical thinking skills for the next generation: from artificial intelligence back to human intelligence. Smart Learn. Environ. 6 , 8 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-019-0088-z

Download citation

Received : 06 June 2019

Accepted : 27 August 2019

Published : 11 September 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-019-0088-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Artificial intelligence

- Critical thinking

- Developmental model

- Human intelligence

- Inquiry learning

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

You will be using throughout CRIT 602 to explore the larger context for your field of study and its associated professions will be critical inquiry:

“ Critical inquiry is the process of gathering and evaluating information , ideas, and assumptions from multiple perspectives to produce well-reasoned analysis and understanding , and leading to new ideas, applications and questions ” (“Critical Inquiry,” n.d.).

A high stakes example of critical inquiry is clinical diagnosis and treatment of physical or mental illness, which involves the doctor asking an entire matrix of complex questions at every stage of the process and knowledge of a body of research that is continually changing, as well as the ability to determine how each set of questions intersects with the body of research.

In a work setting, critical inquiry might be used to solve an organizational problem, such as poor morale among support staff. A director must ask: how can we identify the cause of the decline in morale that we’re experiencing now? When did it start? What factors could have led to it? Have there been changes in management? Have there been changes in our business practices? Could any external factors have caused or contributed to the decline in morale among these staff? Are organizations similar to ours experiencing a similar problem locally? Regionally? Nationally? Has research been done that we could use to find solutions to the problem? What’s been written in the professional literature for our industry that might help us solve our morale problem? Should we bring in a consultant?

In daily life, you might use critical inquiry to buy a car. What kind of vehicle will best meet my needs and the needs of my family? Truck, car, SUV? What about reliability history for the make and model I’m considering? What price range can I afford? How can I find out what is a fair price for the make and model I’m considering? Should I go with dealer financing or get the loan directly through my own bank or credit union? Why is this guy trying to sell me an extended warranty when I’ve already been here for three hours, and I want to go home?

The Role of Reflection in Critical Inquiry

Reflective learning is included in one of the three primary skills goals for CRIT 602: Reflect on learning to guide professional practice. The Center for Simplified Strategic Planning (CSSP) identifies reflection as a critical skill for strategic thinkers:

“Critical Skill #6: [Strategic thinkers] are committed lifelong learners and learn from each of their experiences. They use their experiences to enable them to think better on strategic issues” (“Strategic Thinking,” n.d.) .

We learn from experience by reflecting on it: Simply put, reflection is thinking about new experiences, connecting them to prior experiences, and learning something useful for the future.

In “Defining Reflection: Another Look at John Dewey and Reflective Thinking,” Carol R. Rodgers (2002) defines reflection in a way that aligns particularly well with the critical inquiry you will be conducting into the larger context for your field of study and its associated professions:

1. Reflection is a meaning-making process that moves a learner from one experience into the next with deeper understanding of its relationships with and connections to other experiences and ideas. It is the thread that makes continuity of learning possible, and ensures the progress of the individual and, ultimately, society. It is a means to essentially moral ends.

[Analytical Thinking Goal: You break concepts or evidence into parts and explain how the parts are related to each other.]

2. Reflection is a systematic, rigorous, disciplined way of thinking, with its roots in scientific inquiry.

[Analytical Thinking Goal: Your conclusion is logically tied to information. You have identified consequences and implications clearly.]

3. Reflection needs to happen in community, in interaction with others.

[ CCSP “Critical Skill #8: [Strategic thinkers] are committed to and seek advice from others. They may use a coach, a mentor, a peer advisory group or some other group that they can confide in and offer up ideas for feedback.”] (“Strategic Thinking,” n.d.)

4. Reflection requires attitudes that value the personal and intellectual growth of oneself and others.

[Developing a Community of Practice]

Critical Inquiry (AFCI 101). (n.d.). Retrieved September 10, 2022, from University of South Carolina Aiken website: https://www.usca.edu/academic-affairs/general-education/critical-inquiry.dot

Rodgers, C. (2002). Defining Reflection Another Look at John Dewey and Reflective Thinking. Teachers College Record, 104(4), 842-866.(1).pdf

Strategic thinking: 11 critical thinking skills. (n.d.). Retrieved September 10, 2018, from Center for Simplified Strategic Planning website: https://www.cssp.com/CD0808b/ CriticalStrategicThinkingSkills/

Feel free to check out the full article if you’re interested! (John Dewey was a top influencer in the field of public education.)

- Defining Reflection: Ano ther Look at John Dewey and Reflective Thinking

CRIT 602 Readings and Resources Copyright © 2019 by Granite State College (USNH) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- WordPress.org

- Documentation

- Learn WordPress

- Members Newsfeed

The Art of Asking Questions to Facilitate Inquiry Learning

- Uncategorized

Inquiry learning, or inquiry-based learning, is about triggering a student’s curiosity. With this model, classrooms tend to be more student-driven than teacher-focused. With inquiry learning, a student’s own curiosity propels her to investigate a concept and deepen her knowledge with little teacher intervention.

This all sounds well and good, but how do we intrigue our students to such a degree that they are eager to investigate the topic on their own? Well, it all comes down to the types of questions we ask students- and how we ask these questions. Rather than a science, asking great inquiry questions is more of an art form. Here, we will provide some helpful tips for you to facilitate inquiry learning in your classroom by asking great questions and asking them well.

Why go to all this trouble?

A teacher-centered classroom is certainly easier to facilitate than a student-driven, inquiry-based learning classroom. So why go to all this trouble of changing the way we do things?

As it turns out, inquiry learning enhances the learning experience , leading to a greater level of engagement by the students and thus less classroom management problems on a day to day basis.

In addition, inquiry learning allows students to build critical problem-solving skills, fosters a zeal and passion for learning among students that they will carry with them forever, and allows students to take control of their own learning.

So, how can we ask questions that facilitate this type of engaged learning environment?

How to ask questions that facilitate inquiry learning

All effective inquiry-based questioning techniques have five things in common:

- The entire class is included in the questioning.

- Students are given time to think.

- The teacher plans out the questions ahead of time to make sure they encourage critical thinking and reasoning.

- The teacher avoids judging student responses or deliberately correcting them.

- The teacher responds to these student responses in ways that encourage deeper thinking, often by posing additional questions.

For example, if you teach an art class, you can ask students to think of the words that come to mind when they view a particular piece of art. Then, deepen their analysis further by asking why those words came to mind when viewing the art. Ask the students to be specific and provide visual evidence in their answers. Make sure you allow students time to view the art and contemplate it before asking your inquiry questions.

The don’ts of asking inquiry-based questions

When asking inquiry-based questions, you should avoid doing the following things:

- Answering the question yourself

- Simplifying the question after a student doesn’t immediately respond

- Asking trivial or irrelevant questions

- Asking several questions at once

- Asking questions to only the “brightest” students

- Asking closed questions with only one right or wrong answer

- Saying things such as “well done” that encourage students to stop inquiring

- Ignoring incorrect answers

Doing the above things can turn your student-driven lesson into a teacher-centered lecture. It can take time to perfect the art of asking inquiry questions, but practice makes perfect! Use these techniques in your classroom every day to promote the kind of engaged and passionate learning environment you have always envisioned for your students.

Related Articles

Juneteenth is a day that commemorates the end of slavery in America.…

Father’s Day is celebrated to appreciate and honor the affection, love, and…

Mother’s Day and Father’s Day are significant occasions where individuals celebrate their…

Pedagogue is a social media network where educators can learn and grow. It's a safe space where they can share advice, strategies, tools, hacks, resources, etc., and work together to improve their teaching skills and the academic performance of the students in their charge.

If you want to collaborate with educators from around the globe, facilitate remote learning, etc., sign up for a free account today and start making connections.

Pedagogue is Free Now, and Free Forever!

- New? Start Here

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Registration

Don't you have an account? Register Now! it's really simple and you can start enjoying all the benefits!

We just sent you an Email. Please Open it up to activate your account.

I allow this website to collect and store submitted data.

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

Promoting and Assessing Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is a high priority outcome of higher education – critical thinking skills are crucial for independent thinking and problem solving in both our students’ professional and personal lives. But, what does it mean to be a critical thinker and how do we promote and assess it in our students? Critical thinking can be defined as being able to examine an issue by breaking it down, and evaluating it in a conscious manner, while providing arguments/evidence to support the evaluation. Below are some suggestions for promoting and assessing critical thinking in our students.

Thinking through inquiry