- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Contentious Politics and Political Violence

- Governance/Political Change

- Groups and Identities

- History and Politics

- International Political Economy

- Policy, Administration, and Bureaucracy

- Political Anthropology

- Political Behavior

- Political Communication

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Philosophy

- Political Psychology

- Political Sociology

- Political Values, Beliefs, and Ideologies

- Politics, Law, Judiciary

- Post Modern/Critical Politics

- Public Opinion

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- World Politics

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

The balance of power in world politics.

- Randall L. Schweller Randall L. Schweller Department of Political Science, Ohio State University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.119

- Published online: 09 May 2016

The balance of power—a notoriously slippery, murky, and protean term, endlessly debated and variously defined—is the core theory of international politics within the realist perspective. A “balance of power” system is one in which the power held and exercised by states within the system is checked and balanced by the power of others. Thus, as a nation’s power grows to the point that it menaces other powerful states, a counter-balancing coalition emerges to restrain the rising power, such that any bid for world hegemony will be self-defeating. The minimum requirements for a balance of power system include the existence of at least two or more actors of roughly equal strength, states seeking to survive and preserve their autonomy, alliance flexibility, and the ability to resort to war if need be.

At its essence, balance of power is a type of international order. Theorists disagree, however, about the normal operation of the balance of power. Structural realists describe an “automatic version” of the theory, whereby system balance is a spontaneously generated, self-regulating, and entirely unintended outcome of states pursuing their narrow self-interests. Earlier versions of balance of power were more consistent with a “semi-automatic” version of the theory, which requires a “balancer” state throwing its weight on one side of the scale or the other, depending on which is lighter, to regulate the system. The British School’s discussion of balance of power depicts a “manually operated” system, wherein the process of equilibrium is a function of human contrivance, with emphasis on the skill of diplomats and statesmen, a sense of community of nations, of shared responsibility, and a desire and need to preserve the balance of power system.

As one would expect of a theory that made its appearance in the mid-16th century, balance of power is not without its critics. Liberals claim that globalization, democratic peace, and international institutions have fundamentally transformed international relations, moving it out of the realm of power politics. Constructivists claim that balance of power theory’s focus on material forces misses the central role played by ideational factors such as norms and identities in the construction of threats and alliances. Realists, themselves, wonder why no global balance of power has materialized since the end of the Cold War.

- empirical international relations theory

Introduction

The idea of balance of power in international politics arose during the Renaissance age as a metaphorical concept borrowed from other fields (ethics, the arts, philosophy, law, medicine, economics, and the sciences), where balancing and its relation to equipoise and counterweight had already gained broad acceptance. Wherever it was applied, the “balance” metaphor was conceived as a law of nature underlying most things we find appealing, whether order, peace, justice, fairness, moderation, symmetry, harmony, or beauty. 1 In the words of Jean-Jacques Rousseau: “The balance existing between the power of these diverse members of the European society is more the work of nature than of art. It maintains itself without effort, in such a manner that if it sinks on one side, it reestablishes itself very soon on the other.” 2

Centuries later, this Renaissance image of balance as an automatic response driven by a law of nature still suffuses analysis of how the theory operates within the sphere of international relations. Thus, Hans Morgenthau explained, “The aspiration for power on the part of several nations, each trying either to maintain or overthrow the status quo, leads of necessity, to a configuration that is called the balance of power and to policies that aim at preserving it.” 3 Similarly, Kenneth Waltz declared, “As nature abhors a vacuum, so international politics abhors unbalanced power.” 4 Christopher Layne likewise avers, “Great powers balance against each other because structural constraints impel them to do so.” 5 Realists, such as Arnold Wolfers, invoke the same “law of nature” metaphor to explain opportunistic expansion: “Since nations, like nature, are said to abhor a vacuum, one could predict that the powerful nation would feel compelled to fill the vacuum with its own power.” 6 Using similar structural-incentives-for-gains logic, John Mearsheimer claims that “status quo powers are rarely found in world politics, because the international system creates powerful incentives for states to look for opportunities to gain power at the expense of rivals, and to take advantage of those situations when the benefits outweigh the costs.” 7

From the policymaker’s perspective, however, balancing superior power and filling power vacuums hardly appear as laws of nature. Instead, these behaviors, which carry considerable political costs and uncertain policy risks, emerge through the medium of the political process; as such, they are the product of competition and consensus-building among elites with differing ideas about the political-military world and divergent views on the nation’s goals and challenges and the means that will best serve those purposes. 8 As Nicholas Spykman observed many years ago, “political equilibrium is neither a gift of the gods nor an inherently stable condition. It results from the active intervention of man, from the operation of political forces. States cannot afford to wait passively for the happy time when a miraculously achieved balance of power will bring peace and security. If they wish to survive, they must be willing to go to war to preserve a balance against the growing hegemonic power of the period.” 9

In an era of mass politics, the decision to check unbalanced power by means of arms and allies—and to go to war if these deterrent measures fail—is very much a political act made by political actors. War mobilization and fighting are distinctly collective undertakings. As such, political elites must weigh the likely domestic costs of balancing behavior against the alternative means available to them and the expected benefits of a restored balance of power. Leaders are rarely, if ever, compelled by structural imperatives to adopt certain policies rather than others; they are not sleepwalkers buffeted about by inexorable forces beyond their control. This is not to suggest that they are oblivious to the constraints imposed by international structure. Rather, systemic pressures are filtered through intervening variables at the domestic level to produce foreign policy behaviors. Thus, states respond (or not) to power shifts—and the threats and opportunities they present—in various ways that are determined by both internal and external considerations of policy elites, who must reach consensus within an often decentralized and competitive political process. 10

Meanings of Balance of Power and Balancing Behavior

While the balance of power is arguably the oldest and most familiar theory of international politics, it remains fraught with conceptual ambiguities and competing theoretical and empirical claims. 11 Among its various meanings are (a) an even distribution of power; (b) the principle that power ought to be evenly distributed; (c) the existing distribution of power as a synonym for the prevailing political situation; that is, any possible distribution of power that exists at a particular time; (d) the principle of equal aggrandizement of the great powers at the expense of the weak; (e) the principle that our side ought to have a preponderance of power to prevent the danger of power becoming evenly distributed; in this view, a power “balance” is likened to a bank balance, that is, a surplus rather than equality; (f) a situation that exists when one state possesses the special role of holding the balance (called the balancer) and thereby maintains an even distribution of power between two rival sides; and (g) an inherent tendency of international politics to produce an even distribution of power.

The conceptual murkiness surrounding the theory extends to its core concept, balancing behavior. What precisely does the term “balancing” mean? Some scholars talk about soft balancing, 12 others have added psycho-cultural balancing, political-diplomatic balancing, and strategic balancing, 13 while still others talk about economic and ideological balancing. 14 Because balance of power is a theory about international security and preparations for possible war, I offer the following definition of balancing centered on military capabilities: “Balancing means the creation or aggregation of military power through either internal mobilization or the forging of alliances to prevent or deter the occupation and domination of the state by a foreign power or coalition. The state balances to prevent the loss of territory , either one’s homeland or vital interests abroad (e.g., sea lanes, colonies, or other territory considered of vital strategic interest). Balancing only exists when states target their military hardware at each other in preparation for a possible war. If two states are merely building arms for the purpose of independent action against third parties, we cannot say that they are engaged in balancing behavior. State A may be building up its military power and even targeting another state B and still not be balancing against B, that is, trying to match B’s overall capabilities with the aim of possible territorial conquest or preventing such conquest by B. Instead, the purpose may be coercive diplomacy: to gain bargaining leverage with state B.” 15

The Goals, Means, and Dynamics of Balance of Power

International relations theorists have exhibited remarkable ambiguity about not only the meaning of balance of power but the results to be expected from a successfully operating balance of power system. 16 What is the ultimate promise of balance of power theory? The purpose or goal of balance of power—if such a thing can be attributed to an unintended spontaneously generated order—is not the maintenance of international peace and stability, as many of the theory’s detractors have wrongly asserted. Rather it is to preserve the integrity of the multistate system by preventing any ambitious state from swallowing up its neighbors. The basic intuition behind the theory is that states are not to be trusted with inordinate power, which threatens all members of the international system. The danger is that a predatory great power might gain more than half of the total resources of the system and thereby be in position to subjugate all the rest.

It is further assumed that the only truly effective and reliable antidote to power is power. Increases in power (especially a rival’s growing strength), therefore, must be checked by countervailing power. The means of accomplishing this aim are arms and allies: states counterbalance threatening accumulations of power by building arms (internal balancing) and forming alliances (external balancing) that serve to aggregate each other’s military power. Because the “balance of power” primarily refers to the relative power capabilities of great power rivals and opponents (it is, after all, a theory about great powers, the primary actors in international politics) in the event of war between them, fighting power is the power to be gauged. In determining what capabilities to measure, context is crucial: “To test a theory in various historical and temporal contexts requires equivalent, not identical, measures.” 17 An accurate assessment of the balance of power must include (a) the military capabilities (the means of destruction) each holds and can draw upon; (b) the political capacity to extract and apply those capabilities; (c) the capabilities and reliability of commitments of allies and possible allies; and (d) the basic features of the political geography (viz., the military and political consequences of the relationships between physical geography, state territories, and state power) of the conflict. 18 While the exact components of any particular power capability index will vary, they typically include combinations of the following measures: land area (territorial size), total population, size of armed forces, defense expenditures, overall and per capita size of the economy (e.g., gross national product), technological development (which includes measures such as steel production and fossil fuel consumption), per capita value of international trade, government revenue, and less easily measured capabilities such as political will and competence, combat efficiency, and the like.

In summary, balance of power’s general principle of action may be put as follows: when any state or coalition becomes or threatens to become inordinately powerful, other states should recognize this as a threat to their security (sometimes to their very survival) and respond by taking measures—individually or jointly or both—to enhance their military power. This process of equilibration is thought to be the central operational rule of the system. There is disagreement, however, over how the process, in practice, actually works; that is, over the degree of conscious motivation required for the production of equilibrium. Along these lines, Claude provides three types of balance of power systems: the automatic version , which is self-regulating and spontaneously generated; the semi-automatic version , whereby equilibrium requires a “balancer”—throwing its weight on one side of the scale or the other, depending on which is lighter—to regulate the system; and the manually operated version , wherein the process of equilibrium is a function of human contrivance, with emphasis on the skill of diplomats and statesmen who carefully manage the affairs of the units (states and other non-state territories) constituting the system.

The manually operated balance of power system is consistent with the English School’s notion that states consider balance as something of a collective good. The role of great power comes with the responsibility to maintain the balance of power. It is “a conception of the balance of power as a state of affairs brought about not merely by conscious policies of particular states that oppose preponderance throughout all the reaches of the system, but as a conscious goal of the system as a whole.” 19

Nine Conditions that Promote the Smooth Operation of the Balance of Power

Recognizing the confusion and flexibility attending the term “balance of power,” any attempt to construct a list of conditions that make a balance of power system most likely to emerge, endure, and function properly should be seen as a worthy, if not foolhardy, exercise. In that spirit, I offer the following nine conditions, which are jointly sufficient to bring about an effectively performing balance-of-power system.

At Least Two Egoistic Actors under Anarchy that Seek to Survive. Within an anarchic realm, which lacks a sovereign arbiter to make and enforce agreements among states, there must be at least two states that seek self-preservation, above all, for a balance of power to exist. Further, states must be more self-interested than group-interested. Each desires, if possible, greater power than its neighbors. If states act to promote the long-run community interest over their short-run national interest (narrowly defined), or if they equate the two sets of interests, then they exist within either a Concert system or a Collective Security system. Simply put, states in a balance-of-power system are not altruistic or other-regarding; they act, instead, in ways that maximize their relative gains and avoid or minimize their relative losses. 20

Vigilance . States must be watchful and sensitive to changes in the distribution of capabilities. Vigilance about changes in the balance of power is not only salient with respect to actual or potential rivals. It is also necessary with regard to one’s allies because (a) when its allies are growing weaker, the state must be aware of the deteriorating situation in order to take appropriate measures to remedy the danger; conversely, (b) when its allies are growing rapidly and dramatically stronger, the state should be alarmed because today’s friend may be tomorrow’s enemy.

Mobility of Action . States must not only be aware of changes in the balance of power, they must be able to respond quickly and decisively to them. As Gulick points out: “Policy must be continually readjusted to meet changing circumstances if an equilibrium is to be preserved. A state which, by virtue of its institutional make-up, is unable to readjust quickly to altered conditions will find itself at a distinct disadvantage in following a balance-of-power policy, especially when other states do not labor under the same difficulties.” 21 Here, Gulick echoes a concern at the time (during the early ColdWar period) that democracies are too slow-moving and deliberate to balance effectively, putting them “at a distinct disadvantage” in a contest with an authoritarian regime.

States Must Join the Weaker (or Less Threatening) Side in a Conflict : As Kenneth Waltz puts it, “States, if they are free to choose, flock to the weaker side; for it is the stronger side that threatens them.” 22 According to structural realists, the most powerful state will always appear threatening because weaker states can never be certain that it will not use its power to violate their sovereignty or threaten their survival. Stephen Walt’s balance of threat theory amends this proposition to say: States, if they are free to choose and have credible allies, flock to what they perceive as the less threatening side, whether it is the stronger or weaker of two sides. For Walt, threat is a combination of (a) aggregate power; (b) proximity; (c) offensive capability; and (d) offensive intentions. 23 This last dimension, offensive intentions, is a nonstructural, ideational variable, which some critics of realism see as an ad hoc emendation—one that is only loosely connected, if at all, to neorealism’s core propositions. More on this in the conclusion of the article.

Obviously, balance of power predicts best when states balance against, rather than bandwagon with, threatening accumulations of power. But it is not necessary that every state or even a majority of states balance against the stronger or more threatening side. Instead, balancing behavior will work to maintain equilibrium or to restore a disrupted balance as long as the would-be hegemon is prevented from gaining preponderance by the combined strength of countervailing forces arrayed against it. The exact ratio of states that balance versus those that do not balance is immaterial to the outcome. What matters is that enough power is aggregated to check preponderance. 24

States Must Be Able to Project Power . Mobility of policy also means mobility on the ground. If all states adopt strictly defensive military postures and doctrines, none will be attractive allies. In such a world, external balancing would, for all intents and purposes, disappear, leaving balance-of-power dynamics severely limited. This condition is a very small hurdle for the theory to clear, however, since “great powers inherently possess some offensive military capability,” as John Mearsheimer has forcefully argued. 25

War Must Be a Legitimate Tool of Statecraft . Balancing behaviors are preparations for war, not peace. If major-power war eventually breaks out, as it did in 1914 and 1939 , there is no reason to conclude that the balance of power failed to operate properly. Quite the opposite: balance of power requires that “war must be a legitimate tool of statecraft.” 26 The outbreak of war, therefore, does not disconfirm but, in most cases, supports the theory. As Harold Lasswell observed in 1935 , the balancing of power rests on the expectation that states will settle their differences by fighting. 27 This expectation of violence exercises a profound influence on the types of behaviors exhibited by states and the system as a whole. It was not just the prospect of war that triggered the basic dynamics of past multipolar and bipolar systems. It was the anticipation that powerful states sought to and would, if given the right odds, carry out territorial conquests at each other’s expense that shaped and shoved actors in ways consistent with the predictions of realism’s keystone theory.

No Alliance Handicaps . For a balance-of-power system to operate effectively, alliance formation must be fluid and continuous. States must be able to align and realign with other states solely on the basis of power considerations. In practice, however, various factors diminish the attractiveness of certain alliances that would otherwise be made in response to changes in the balance of power that threaten the state’s security. These constraints—rooted in ideologies, personal rivalries, national hatreds, ongoing territorial disputes and the like—that impede alignments made for purely strategic reasons are called “alliance handicaps.” 28 In effect, they narrow the competitive alternatives available to states searching for allies.

Parenthetically, alliance handicaps explain why the alliance flexibility that seemingly derives from the wealth of physical alternatives theoretically available under a multipolar structure should not be confused with the actual alternatives that are politically available to states within the system given their particular interests and affinities. 29 Indeed, the greater flexibility of alliances and fluidity of their patterns under multipolarity, as opposed to bipolarity, is more apparent than real. Seen from a purely structural perspective, a multipolar system appears as an oligopoly, with a few sellers (or buyers) collaborating to set the price. Behaviorally, however, multipolarity tends toward duopoly: the few are often only two. This scarcity of alternatives due to the presence of alliance handicaps contradicts the conventional wisdom of the flexibility of alliances in a multipolar system.

Pursue Moderate War Aims . Because today’s friend may be tomorrow’s enemy, states should pursue moderate war aims and avoid eliminating essential actors. In Gulick’s words, “An equilibrium cannot perpetuate itself unless the major components of that equilibrium are preserved. Destroy important makeweights and you destroy the balance; or in the words of Fénelon to the grandson of Louis XIV early in the 18th century: ‘never … destroy a power under pretext of restraining it.’” 30 This lesson is easily grasped when one considers the composition of alignments before and after major-power wars. During the Second World War, for instance, the United States was allied with China and the Soviet Union against Italy, Germany, and Japan. After the war, the United States, victorious but wisely having chosen not to eliminate its vanquished enemies, allied with Japan, Italy, and West Germany against its erstwhile allies, the Soviet Union and Communist China.

For structural realists, moderate outcomes result because of, not in spite of, the greed and fear of states—to behave too forcefully, too recklessly expansionist, will lead others to mobilize against you. This is a very different understanding of moderation than the one that Edward Gulick and members of the English School have in mind when they speak of moderation within a balance of power: “restraint, abnegation, and the denial of immediate self-interest.” What is required is “the subordination of state interest to balance of power.” 31 For most realists, these notions better describe a Concert system than one rooted in balance-of-power politics, where states simply follow their narrow, short-run self-interests.

Proportional Aggrandizement (or Reciprocal Compensations ). Sometimes moderation toward the defeated power is unachievable. Under such circumstances, “if the cake cannot be saved, it must be fairly divided.” What is fair? Gulick suggests that “equal compensation” is fair. The concept of reciprocal compensation or proportional aggrandizement, he claims, “stated that aggrandizement by one power entitled other powers to an equal compensation or, negatively, that the relinquishing of a claim by one power must be followed by a comparable abandonment of a claim by another.” 32 Such an “equality” rule, however, would disrupt an existing balance. If, for instance, one state is twice as powerful as another, and together they are dividing up a third state, a division down the middle, giving them each half, will advantage the weaker power relative to its stronger partner. Instead, “proportional” compensation is not only fair but will maintain an existing equilibrium among the great powers. Simply put, the rule governing partitions must be that “the biggest dog gets the meatiest bone, and so on.” Returning to our example, a balance will be maintained if the defeated state is partitioned such that two thirds of it goes to the state that is twice as strong as its weaker associate, which receives the remaining third. Such proportional aggrandizement prevents any great power from making unfair relative gains at the expense of the others.

The Balance of Power as an International Order

At its essence, balance of power is a type of international order. What do we mean by an international order? A system exhibits “order” when the set of discrete objects that comprise the system are related to one another according to some pattern; that is, their relationship is not miscellaneous or haphazard but accords with some discernible principle. Order prevails when things display a high degree of predictability, when there are regularities, when there are patterns that follow some understandable and consistent logic. Disorder is a condition of randomness—of unpredictable developments lacking regularities and following no known principle or logic. The degree of order exhibited by social and political systems is partly a function of stability. Stability is the property of a system that causes it to return to its original condition after it has been disturbed from a state of equilibrium. Systems are said to be unstable when slight disturbances produce large disruptions that not only prevent the original condition from being restored but also amplify the effect of the perturbation. This process is called “positive feedback,” because it pushes the system increasingly farther away from its initial steady state. The classic example of positive feedback is a bank run caused by self-fulfilling prophesies: people believe something is true (there will be a run on the bank), so their behavior makes it true (they all withdraw their money from the bank); and others’ observations of this behavior increases the belief that it is true, so they behave accordingly (they, too, withdraw their money from the bank), which makes the prophesy even more true, and so on. 33

Some systems are characterized by robust and durable orders. Others are extremely unstable, such that their orders can quickly and without warning collapse into chaos. Like an avalanche, or peaks of sand in an hourglass that suddenly collapse and cascade, or a spider web that takes on an entirely new pattern when a single strand is cut, complex and delicately balanced systems are unpredictable: they may appear calm and orderly at one moment only to become wildly turbulent and disorderly the next. This inherent instability of complex, tightly coupled systems is captured by the popular catch phrase, “the butterfly effect,” coined by the MIT meteorologist, Edward Lorenz, to explain how a massive storm can be caused (or prevented) by the faraway flapping of a tiny butterfly’s wings. The principal lesson of the butterfly effect is that, when incalculably small differences in the initial conditions of a system matter greatly, the world becomes radically unpredictable. 34 Indeed, we can seldom predict what will happen when a new element is added to a system composed of many parts connected in complex ways. Such systems undergo frequent discontinuous changes from shocking impacts that create radical departures from the past.

International orders vary according to (a) the amount of order displayed; (b) whether the order is purposive or unintended; and (c) the type of mechanisms that provide order. On one end of the spectrum, there is rule-governed, purposive order, which is explicitly designed and highly institutionalized to fulfill universally accepted social ends and values. 35 At the other extreme, international order is an entirely unintended and un-institutionalized recurrent pattern (e.g., a balance of power) to which the actors and the system itself exhibit conformity but which serves none of the actors’ goals or which, at least, was not deliberately designed to do so. Here, international order is spontaneously generated and self-regulating. The classic example of this spontaneously generated order is the balance of power, which arises though none of the states may seek equality of power; to the contrary, all actors may seek greater power than everyone else, but the concussion of their actions (which aim to maximize their power) produces the unintended consequence of a balance of power. 36 In other words, the actors are constrained by a system that is the unintended product of their coactions (akin to the invisible hand of the market, which is a spontaneously generated order/system).

There are essentially three types of international orders:

A negotiated order. A rule-based order that is the result of a grand bargain voluntarily struck among the major actors who, therefore, view the order as legitimate and beneficial. It is a highly institutionalized order, ensuring that the hegemon will remain engaged in managing the order but will not exercise its power capriciously. In this way, a negotiated rule-based order places limits on the returns to power, especially with respect to the hegemon. Pax Americana ( 1945 –present) and, to a lesser extent, Pax Britannica (19th century) are exemplars of this type of “liberal constitutional” order. 37

An imposed order. A non-voluntary order among unequal actors purposefully designed and ruled by a malign (despotic) hegemon, whose power is unchecked. The Soviet satellite system is an exemplar of this type of order.

A spontaneously generated order. Order is an unintended consequence of actors seeking only to maximize their interests and power. It is an automatic or self-regulating system. Power is checked by countervailing power, thereby placing limits on the returns to power. The classic 18th century European balance of power is an exemplar of this type of order.

The predictability of a social system depends, among other things, on its degree of complexity, whether its essential mechanisms are automatic or volitional, and whether the system requires key members to act against their short-run interests in order to work properly. Negotiated (sometimes referred to as “constitutional”) orders are complex systems that rely on ad hoc human choices and require actors to choose voluntarily to subordinate their immediate interests to communal or remote ones (e.g., in collective security systems). As such, how they actually perform when confronted with a disturbance that trips the alarm, so to speak, will be highly unpredictable. In contrast, the operation of a balance-of-power system is fairly automatic and therefore highly predictable. It simply requires that states, seeking to survive and thrive in a competitive, self-help realm, pursue their short-run interests; that is, states seek power and security, as they must in an anarchic order. 38

Here, I do not mean to suggest that balance-of-power systems always function properly and predictably. Balancing can be late, uncertain, or nonexistent. These types of balancing maladies, however, typically occur when states consciously seek to opt out of a balance-of-power system, as happened in the interwar period, but then fail to replace it with a functioning alternative security system. The result is that a balance-of-power order, which may be viewed as a default system that arises spontaneously, in the absence or failure of concerted arrangements among all the units of the system to provide for their collective security, eventually emerges but is not accomplished as efficiently as it otherwise would have been.

Does Balancing Behavior Prevail Over Other State Responses to Growing Power?

There have been several recent challenges to the conventional realist wisdom that balancing is more prevalent than bandwagoning behavior, that is, when states join the stronger or more threatening side. 39 Paul Schroeder’s broad historical survey of international politics shows that states have bandwagoned with or hid from threats far more often than they have balanced against them. Similarly, I have claimed that bandwagoning behavior is more prevalent than contemporary realists have led us to believe because alliances among revisionist states, whose behavior has been ignored by modern realists, are driven by the search for profit, not security. 40 Most recently, Robert Powell treats states as rational unitary actors within a simple strategic setting composed of commitment issues, informational problems, and the technology of coercion and finds that “balancing is relatively rare in the model. Balances of power sometimes form, but there is no general tendency toward this outcome. Nor do states generally balance against threats. States frequently wait, bandwagon, or, much less often, balance.” 41 Powell freely admits, however, that a rational-unitary-actor assumption “does not mean that domestic politics is unimportant.” 42 None of these studies, however, has offered a domestic-politics explanation for bandwagoning or a theory of the broader phenomenon of underbalancing behavior, which includes buck-passing, distancing, hiding, waiting, appeasement, bandwagoning, incoherent half-measures, and, in extreme cases, civil war, revolution, and state disintegration.

In addition to studies of bandwagoning, there has been some work on what is called “buck-passing” behavior, a form of under-reaction to threats by which states attempt to ride free on the balancing efforts of others. Two popular explanations for buck-passing behavior are structural-systemic ones. Thomas Christensen and Jack Snyder claim that great powers under multipolarity will buck-pass when they perceive defensive advantage; while John Mearsheimer argues that buck-passing occurs primarily in balanced multipolar systems, especially among great powers that are geographically insulated from the aggressor. 43 Others argue that whether or not states balance against threats is not primarily determined by systemic factors but rather by domestic political processes. 44

Along these lines, it is important to point out that, when we speak of balancing and other competing responses to growing power, we are actually referring to four distinct categories of behavior. First, there is appropriate balancing , which occurs when the target is a truly dangerous aggressor that cannot or should not be appeased. Second, there is inappropriate balancing , which unnecessarily triggers a costly and dangerous arms spiral because the target is misperceived as an aggressor but is, in fact, a defensively minded state seeking only to enhance its security. 45 Third, there is nonbalancing , which may take the form of buck-passing, bandwagoning, appeasement, engagement, distancing, or hiding. These policies may be quite prudent and rational when the state is thereby able to avoid the costs of war either by satisfying the legitimate grievances of the revisionist state or allowing others to satisfy them, or by letting others defeat the aggressor while safely remaining on the sidelines. Moreover, if the state also seeks revision, then it may wisely choose to bandwagon with the potential aggressor in the hope of profiting from its success in overturning the established order. Finally, there is an unusual state of affairs, such as those we live under today, in which one state is so overwhelmingly powerful that there can be said to exist an actual harmony of interests between the hegemon (or unipole) and the rest of the great powers—those that could either one day become peer competitors or join together to balance against the predominant power. The other states do not balance against the hegemon because they are too weak (individually and collectively) and, more important, because they perceive their well being as inextricably tied up with the well-being of the hegemon. Here, potential “balancers” bandwagon with the hegemon not because they seek to overthrow the established order (the motive for revisionist bandwagoning), but because they perceive themselves to be benefiting from the status-quo order and, therefore, seek to preserve it. 46

Finally, there is underbalancing , which occurs when the state does not balance or does so inefficiently in response to a dangerous and unappeasable aggressor, and the state’s efforts are absolutely essential to deter or defeat it. In these cases, the underbalancing state not only does not avoid the costs of war but also brings about a war that could have been avoided or makes the war more costly than it otherwise would have been or both. 47

Criticisms of Balance-of-Power Theory

Since the end of the Cold War, many scholars of international politics have come to believe that realism and the balance of power are now obsolete. Liberal critics charge that, while power balancing may have been appropriate to a bygone era, international politics has been transformed as democracy extends its sway, as interdependence tightens its grip, and as institutions smooth the way to peace. If other states do arise over the coming decades to become peer competitors of the United States, the world will not return to a multipolar balance of power system but rather will enter a new multipartner phase. In the words of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, “It does not make sense to adapt a 19th-century concert of powers or a 20th-century balance-of-power strategy. We cannot go back to Cold War containment or to unilateralism,” she said in a speech at the Council on Foreign Relations in July 2009 . “We will lead by inducing greater cooperation among a greater number of actors and reducing competition, tilting the balance away from a multipolar world and toward a multipartner world.” 48

It is a view based on the assumption that history moves forward in a progressive direction—one consistent with the metaphor of time’s arrow. 49 Of course, realists have heard all this before. Consider Woodrow Wilson’s description of pre-World War I Europe: “The day we left behind us was a day of alliances. It was a day of balances of power. It was a day of ‘every nation take care of itself or make a partnership with some other nation or group of nations to hold the peace of the world steady or to dominate the weaker portions of the world’.” 50

While I suspect that social constructivists would agree with most (if not all) of the arguments posed by the liberal challenge to realism, the thrust of their attack is more conceptual and theoretically oriented. As mentioned, Stephen Walt’s “balance of threat” theory, by including “aggressive intentions” as a dimension of threat, widens the stimuli to which states perceive dangers to include more than just material power. Social constructivists, like Michael Barnett, charge that Walt, having shattered neorealist theory, does not go far enough in defining the ideational elements that determine threats and alliances. Ideology and ideas about identity and norms are, according to social constructivists, often the most important sources of threat perception, as well as the primary basis for alliance formation itself. 51

Finally, even self-described realists wonder if balance of power still operates in the contemporary world, at least at the global level. For various “sound realist” reasons, Stephen Brooks and William Wohlforth see a world out of balance—one in which the United States maintains its unchallenged global primacy for another 20 years or more. 52 Edward Rhodes goes farther, urging the field to abandon, rather than hopelessly attempting to rehabilitate, the “balancing” metaphor and the logic that flows from it. Balancing behavior, he claims, makes no sense in a world devoid of “trinitarian wars” and the belief that any state, if too powerful and unchecked by other states, threatens the sovereignty of all other states. Today, nuclear arsenals assure great powers of the ultimate invulnerability of their sovereignty. 53 Moreover, war among the great powers in the present age is, if not downright ludicrous and unthinkable, far from an expected and sensible means to resolve their disputes. Balance of power is a theory deeply rooted in a territorial view of wealth and security—a world that no longer exists. 54

- Barnett, M. N. Identity and alliances in the Middle East. (1996). In P. J. Katzenstein (Eds.), The culture of national security: Norms and identity in world politics (pp. 400–447). New York: Columbia University Press.

- Betts, R. K. (1992). Systems for peace or causes of war? Collective security, arms control, and the new Europe. International Security , 17 (1), 5–43.

- Brooks, S. G. , & Wohlforth, W. C. (2005). Hard times for soft balancing. International Security , 30 (1), 72–108.

- Brooks, S. G. , & W. C. Wohlforth . (2008). World out of balance: International relations and the challenge of American primacy . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Bull, H. (1977). The anarchical society: A study of order in world politics . New York: Columbia University Press.

- Carr, E. H. (1964). The twenty years’ crisis, 1919–1939: An introduction to the study of international relations . New York: Harper and Row.

- Christensen, T. J. , & Snyder, J. (1990). Chain gangs and passed bucks: Predicting alliance patterns in multipolarity. International Organization , 44 (2), 137–168.

- Claude, I. L., Jr. (1962). Power and international relations . New York: Random House.

- Claude, I. L., Jr. (1989). The balance of power revisited. Review of International Studies , 15 (2), 77–85.

- Clinton, H. R. (2009). Foreign policy address at the council on foreign relations , U.S. Secretary of State, speaking to the Council on Foreign Relations, Washington, DC, July 15, 2009.

- Dehio, L. (1962). The precarious balance: Four centuries of the European power struggle . ( C. Fullman , Trans.), New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Gould, S. J. (1987). Time’s arrow, time’s cycle: Myth and metaphor in the discovery of geological time . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Grieco, Joseph M. (1990). Cooperation among nations: Europe, America, and non-tariff barriers to trade . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Gulick, E.V. (1950). Europe’s classical balance of power . New York: Norton.

- Haas, E. B. (1953). The balance of power: Prescription, concept, or propaganda? World Politics , 5 (4), 442–447.

- Haas, M. L. (2005). The ideological origins of great power politics, 1789–1989 . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press,

- Haas, M. L. (2012). The clash of ideologies: Middle Eastern politics and American security . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hardin, G. (1963). The cybernetics of competition: A biologist’s view of society. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine , 7 (3), 58–84.

- Heginbotham, E. , & Samuels, R. J. (1998). Mercantile realism and Japanese foreign policy. International Security , 22 (4), 171–203.

- Hilsman, R. (1971). The politics of policy making in defense and foreign affairs . New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Hinsely, F. H. (1963). Power and the pursuit of peace: Theory and practice in the history of relations between states . Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Ikenberry, G. J. (2001). After victory: Institutions, strategic restraint, and the rebuilding of order after major wars . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Jervis, R. (1976). Perception and misperception in international politics . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Jervis, R. (1986). From balance to concert: A study of international security cooperation. In K. A. Oye (Ed.), Cooperation under anarchy (pp. 58–79). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Jervis, R. , & Snyder, J. , eds. (1991). Dominoes and bandwagons: Strategic beliefs and great power competition in the Eurasian rimland . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Joffe, J. (2002). Defying history and theory: The United States as the “last remaining superpower.” In G. J. Ikenberry (Ed.), America unrivaled: The future of the balance of power (pp. 155–180). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Lasswell, H. D. (1965). World politics and personal insecurity . New York: Free Press.

- Layne, C. (1997). From preponderance to offshore balancing: America’s future grand strategy” International Security , 22 (1), 86–124.

- Levy, J. S. (2003). Balances and balancing: Concepts, propositions, and research design.” In J. A. Vasquez & C. Elman , (Eds.), Realism and the balancing of power: A new debate (pp. 128–153). Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Levy, J. S. , & Barnett, M. N. (1991). Domestic sources of alliances and alignments: The case of Egypt, 1962–1973. International Organization , 45 (3), 369–395.

- Levy, J. S. , & Barnett, M. N. . (1992). Alliance formation, Domestic political economy, and third world security. The Jerusalem Journal of International Relations , 14 (4), 19–40.

- Lieber, K. A. , & Alexander, G. (2005). Waiting for balancing: Why the world is not pushing back. International Security , 30 (1) 109–139.

- Lobell, S. , Taliaferro, J. , & Ripsman, N. , eds. (2009). Neoclassical realism, the state, and foreign policy . New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Lorenz, E. (December 29, 1972). Predictability: Does the flap of a butterfly's wings in brazil set off a tornado in Texas? Paper presented at the 139th meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, DC.

- Luard, E. (1992). The balance of power: The system of international relations, 1648–1815 . London: Macmillan.

- Mearsheimer, J. J. (2001). The tragedy of great power politics . New York: Norton.

- Moran, T. H. (1993). An economics agenda for neorealists” International Security , 18 (2), 211–215.

- Morgenthau, H. J. (1966). Politics among nations: The struggle for power and peac e (4th ed.). New York: Alfred Knopf,

- Moul, W. B. (1989): Measuring the “balances of power”: A look at some numbers. Review of International Studies , 15 (2), 101–121.

- Pape, R.A. (2005). Soft balancing against the United States, International Security , 3 0(1), 7–45.

- Paul, T. V. (2004). The enduring axioms of balance of power theory. In T. V. Paul , J. J. Wirtz , & M. Fortmann (Eds.), Balance of power: Theory and practice in the twenty-first century (pp. 1–25). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Paul, T. V. (2005), Soft balancing in the age of U.S. primacy. International Security , 30 (1), 46–71.

- Powell, R. (1999). In the shadow of power: States and strategies in international politics . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Rhodes, E. (2004). A world not in the balance: War, politics, and weapons of mass destruction. In T. V. Paul , J. J. Wirtz , & M. Fortmann (Eds.), Balance of power: Theory and practice in the 21st century (pp. 150–176). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Rose, G. (1998). Neoclassical realism and theories of foreign policy. World Politics , 51 (1), 144–172.

- Schilling, W. R. (1962). The politics of national defense: Fiscal 1950. In W. R. Schilling , P. Y. Hammond , & G. H. Snyder (Eds.), Strategy, politics, and defense budget s (pp. 5–27). New York: Columbia University Press.

- Schroeder, P. (1994). Historical reality vs. neo-realist theory. International Security 19 (1), 108–148.

- Schweller, R. L. (1994). Bandwagoning for profit: Bringing the revisionist state back in. International Security , 19 (1), 72–107.

- Schweller, R. L. (December 1997). New realist research on alliances: Refining, not refuting, Waltz's balancing proposition. American Political Science Review , 91 (4), 927–930.

- Schweller, R. L. (2003). The progressiveness of neoclassical realism. In C. Elman & M. F. Elman (Eds.), Progress in international relations theory: Appraising the field (pp. 311–347). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Schweller, R. L. (2006). Unanswered threats: Political constraints on the balance of power . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Schweller, R.L. (2014). Maxwell’s demon and the golden apple: Global discord in the new millennium . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Seabury, P. , ed. (1965). Balance of power . San Francisco: Chandler.

- Sheehan, M. 1996. Balance of power: History and theory . New York: Routledge.

- Snyder, G. H. (1997). Alliance politics . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Spykman, N. J. (1942). A merica’s strategy in world politics: The United States and the balance of power . New York: Harcourt, Brace.

- Sweeney, K. , & Fritz, P. (2004). Jumping on the bandwagon: An interest-based explanation for great power alliances. Journal of Politics , 66 (2), 428–449.

- Vagts, A. (1948). The balance of power: Growth of an idea. World Politics , 1 (1), 82–101.

- Vincent, R. J. , & Wright, M. , eds. (1989). The balance of power [Special issue]. Review of International Studies , 15 (2).

- Walt, S. M. (1987). The origins of alliances . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Waltz, K. N. (1979). Theory of international politics . Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Waltz, K. N. (2000). Structural realism after the Cold War. International Securi ty, 25 (1), 5–41.

- Wohlforth, W. C. (1999). The stability of a unipolar world. International Security , 24 (1) 5–41.

- Wolfers, A. (1962). Discord and collaboration: Essays on international politics . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

1. See Vagts ( 1948 ), 82–101. For classic analyses on the balance of power, see Wolfers ( 1962 ), 122–124; Hinsely (1963 ); Dehio ( 1962 ); Sheehan ( 1996 ); Luard ( 1992 ); Claude ( 1962 ); and Seabury ( 1965 ). For impressive recent analyses, see Levy ( 2003 ), 128–153; and Paul ( 2004 ). See also Vincent & Wright ( 1989 ).

2. Quoted in Haas ( 1953 ), 453.

3. Morgenthau ( 1966 ), 163.

4. Waltz ( 2000 ), 28.

5. Christopher Layne ( 1997 ), 117.

6. Wolfers ( 1962 ), 15.

7. Mearsheimer ( 2001 ), 21.

8. See, for example, the description of the policy-making process in Schilling ( 1962 ), 5–27; and Hilsman ( 1971 ).

9. Spykman ( 1942 ), 25.

10. This theme fits squarely within the new wave of neoclassical realist research. Neoclassical realists argue that states assess and adapt to changes in their external environment partly as a result of their peculiar domestic structures and political situations. Because complex domestic political processes act as transmission belts between external factors (primarily, changes in relative power) and policy outputs, states often react differently to similar systemic pressures and opportunities, and their responses may be less motivated by systemic-level factors than domestic ones. See Rose ( 1998 ), 144–172; Schweller ( 2003 ), 311–348; and Lobell, Taliaferro, & Ripsman ( 2009 ).

11. For a sampling of this discussion, see J. A. Vasquez & C. Elman(Eds.), Realism and the balancing of power: A new debate . Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

12. T. V. Paul offers the following definition: “Soft balancing involves tacit balancing short of formal alliances. It occurs when states generally develop ententes or limited security understandings with one another to balance a potentially threatening state or a rising power. Soft balancing is often based on a limited arms buildup, ad hoc cooperative exercises, or collaboration in regional or international institutions; these policies may be converted to open, hard-balancing strategies if and when security competition becomes intense and the powerful state becomes threatening.” (Paul, 2004 , p. 3). See also Pape ( 2005 ), 7–45; Paul ( 2005 ), 46–71; Brooks & Wohlforth ( 2005 ), 72–108; and Lieber & Alexander ( 2005 ), 109–139.

13. Joffe ( 2002 ), 155–180.

14. For economic balancing, see Heginbotham & Samuels ( 1998 ), 171–203, esp. pp. 192–193; and Moran ( 1993 ), 211–215. For ideological balancing rooted in ideological polarity and distance, see Haas ( 2005 ); and Haas ( 2012 ).

15. Schweller (2006 ), 9. Some would now refer to this definition as “hard” balancing as opposed to “soft” balancing.

16. Claude, Jr. ( 1989 ), 78.

17. Moul, ( 1989 ), 103.

18. Moul, ( 1989 ).

19. See Bull ( 1977 ), 106.

20. Realists call this “defensive positionality.” See Grieco ( 1990 ).

21. Gulick ( 1950 ), 68.

22. Waltz ( 1979 ), 127.

23. The original statement of balance of threat theory is K. N. Walt (1985), Alliance formation and the balance of world power, International Security , 9 (4), 3–43.

24. For this argument, see Schweller, ( 1997 ), 927–930 and at 929.

25. Mearsheimer ( 2001 ), 30.

26. Jervis ( 1986 ), 60.

27. Lasswell ( 1965 ), chap. 3. This was originally published in 1935.

28. Jervis ( 1986 ), 60.

29. See Snyder ( 1997 ), 148–149.

30. Gulick ( 1950 ), 72–73.

31. Ibid ., 33, 304.

32. Ibid ., 70–71.

33. See Hardin ( 1963 ), 63–64, 73.

34. The term “butterfly effect” grew out of Lorenz ( 1972 ), an unpublished academic paper.

35. This is Hedley Bull’s definition of social order in Bull ( 1977 ), 3–22.

36. The source of stability in a balance-of-power system (equilibrium) may arise as an unintended consequence, either of actors seeking to maximize their power or of the imperative for actors wishing to survive in a competitive self-help system to balance against threatening accumulations of power. See Waltz ( 1979 ), 88–93 and chap. 6.

37. For constitutional order, see Ikenberry ( 2001 ).

38. For this logic, see Betts ( 1992 ), 5–43.

39. For the dominant view that balancing prevails over bandwagoning and other responses to rising threats, see Walt ( 1987 ).

40. Schroeder ( 1994 ), 108–148; and Schweller ( 1994 ), 72–148. Also see Jervis & Snyder ( 1991 ); and Sweeney & Fritz ( 2004 ), 428–449.

41. Powell ( 1999 ), 196.

42. Powell ( 1999 ), 26.

43. Christensen & Snyder ( 1990 ), 137–168; and Mearsheimer ( 2001 ), 271–273.

44. See, for example, Schweller ( 2006 ); Levy & Barnett ( 1991 ), 369–395; and Levy & Barnett ( 1992 ), 19–40.

45. This view of appropriate and inappropriate balancing follows Jervis’s spiral and deterrence models. See Jervis ( 1976 ), 58–114.

46. See Carr ( 1964 ), 80–82. Also see Wohlforth ( 1999 ), 5–41.

47. For underbalancing behavior, see Schweller ( 2006 ).

48. Clinton ( 2009 ).

49. See Gould ( 1987 ).

50. Quoted in Claude Jr. ( 1962 ), 81.

51. See Barnett ( 1996 ), 400–447.

52. Brooks & Wohlforth ( 2008 ).

53. Rhodes ( 2004 ), 150–176.

54. Rhodes ( 2004 ), 150–176; and Schweller ( 2014 ).

Related Articles

- War Termination

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Politics. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 24 June 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [109.248.223.228]

- 109.248.223.228

Character limit 500 /500

Balance of Power Concept in International Relations Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Iraq invasion.

“To some, power balancing is the inevitable and conflict-ridden by-product of anarchy and insecurity; to others, it is the unifying principle of a stable and cooperative international society” (Ikenberry 2008, p. 1). Ikenberry’s definition of power balance in international relations shows that, the concept is understood in different ways.

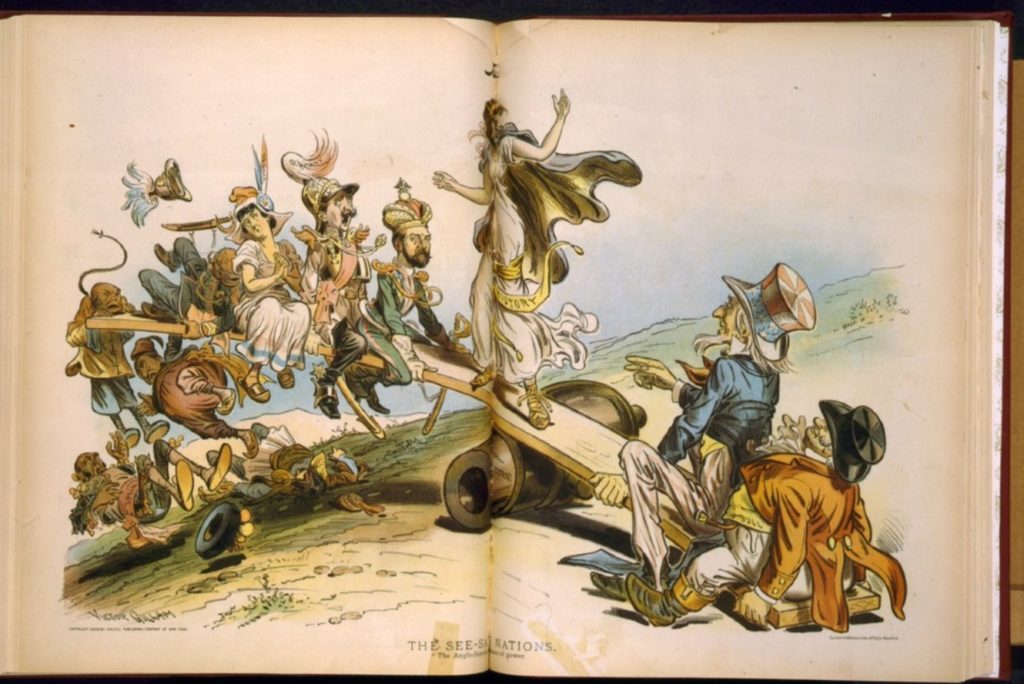

However, power balance (in international relations) is an ancient ideology which defines how states, cities and regions relate. In fact, the rivalry of most world powers is best understood through the lens of “power balance” (Little 2007, p. 1).

In modern international relations, a balance of power can only be achieved if states attain a level of stability among themselves. This level of stability is attained in the absence of competition. Realistically, many states have failed to achieve this equilibrium.

The concept of power balance is enshrined in a political system that defines the behavior of states in the system (Ikenberry 2008, p. 1). A balance of power is often desirable because; in its presence, the likelihood that one state takes advantage of another is low (or non-existent).

When a group of states (or one state) increases its power, other states are likely to retaliate by increasing their powers too (Ikenberry 2008, p. 1). It is an endless cycle of power struggle which is defined by the doctrines of equality (Sheehan 1996). Naturally, the doctrine of equality is cemented in the fact that, states would want to ensure they are secure (first) before tackling any other nationalistic agendas.

Since the 17 th century, there have been many examples of power balance tussles (Ikenberry 2008, p. 1). However, this paper focuses on the Russia–America cold war and the US-led invasion of Iraq (in 2003) as the main examples of power balance conflicts in present times. These two cases will be used as examples to understand the concept of balance of power.

The US and Russia were embroiled in a complicated balance of power tussle which was fueled by ideological, economic, and political differences (Ross 1993, p. 138). Many observers say that, the biggest difference between the two states was the difference in political systems (Ross 1993, p. 138).

Russia was a communist state and the US was a capitalist state. This difference often saw the two countries disagree on many issues, including the Cuban missile crisis that almost sent the two countries to war. The US and Russia could barely agree on any policy issue.

The conflict between the US and Russia started when the US was displeased by Russia’s resolve to withdraw from World War I (Mayall 1980, p. 161). Moreover, the US did not condone Russia’s political, social and economic systems, which were based on communism.

The US saw the communist system as a threat to its national security. For instance, the US worried about Russia’s growing influence in Europe (after the defeat of the Nazi Germany) because it already had a strong political and economic dominance in the region.

This worry was especially strong because the US knew that its political and economic ideologies were very different from Russia, and with Russia’s growing influence in Europe, its influence in Europe would be undermined (Ross 1993, p. 138).

These fears were rife when Russia and the US competed for international influence. US’s fear in this balance of power tussle is highlighted in earlier sections of this study, where it is noted that, in a balance of power tussle, states often strive to ensure they are secure, above all nationalistic issues.

The tense relations between Russia and America sparked the cold war, which was waged through military dominance. This balance of power tussle saw Russia detonate its first atomic weapon. This event marked the end of US’s autonomy of possessing nuclear weapons (Pandey 2009, p. 5).

The post-Nazi period marked the start of the cold war, where the US and Russia embarked on developing military armory (notably nuclear weapons). This military supremacy battle went on until the fall of the communism regime in 1991. The fall of communism marked the end of the cold war (Pandey 2009, p. 5).

From the above analysis, we see that, the US and Russia were engaged in a balance of power tussle that saw the two states striving to command a strong international influence over the other. Notably, this international influence was exercised in Europe, where the US and Russia strived to maintain a strong international influence.

Both states felt threatened by one other because they had opposing ideologies regarding most political and economic issues. However, with the fall of communism and USSR, the US warmed up to Russia, and the cold war ended.

This period marked the equilibrium of power between the two nations. This equilibrium is often marked with a feeling of security and an absence of military threats (Brown 2001, p. 106).

The US-led war on Iraq is a historic war of the 21 st century because it exhibits the concept of the balance of power in international relations. Though the war was won by ousting the long-serving Iraqi ruler, Saddam Hussein; the main objective of the mission (which was to eliminate weapons of mass destruction) was not achieved.

The US believed that, Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction, but it failed to validate these accusations after attacking Iraq (Pandey 2009, p. 5). This justification for war is part of a wider understanding of balance of power in international relations because, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the US became increasingly dominant in international politics.

Its military strength became virtually unrivaled and therefore, it wielded immense political and economic influence over other nations (Pandey 2009, p. 5). More so, this power was vested in the formation of NATO which acts as a military powerhouse for member states.

However, when analyzing the concept of balance of power (in the context of the Iraq war), we should perceive the US-led invasion on Iraq as an extreme consequence of power imbalance. This analogy is true because the US decided to invade Iraq despite UN’s disapproval of the invasion.

Records show that, most of the major world powers, such as, France, Germany, China and Russia opposed the invasion but the US went ahead to invade Iraq, anyway (Pandey 2009, p. 5). This domination is explained as, a consequence of power imbalance because the US wields a lot of power over other states in the world.

From this understanding, the US is able to impose its will over other nations. In relation to this analogy, Pandey (2009) explains that, “In International Relations, an equilibrium of power is sufficient to discourage or prevent one nation from imposing its will on or interfering with the interests of another” (p. 5).

Due to the imbalance of power between the US and other states, the US was able to impose its will over other states by invading Iraq.

The Iraq war is just an example of the gap in military power that exists between the US and major world powers (which even small states can do nothing to counterbalance). The US-led invasion in Iraq therefore reiterates the importance of striving for a balance of power among states because, if this equilibrium is not achieved, a sense of dominance will be witnessed.

The concept of power balance in international relations has never been more important than when trying to understanding how different states relate. This paper gives an example of the hostile relations that existed between the US and Russia, and the US-led invasion in Iraq as modern-day examples of the understanding of balance of power in international relations.

Considering the events that preceded the collapse of the USSR and the end of the cold war, we see that, there was an imbalance of power between the US and Russia before the collapse of the USSR. After the collapse of the USSR, there was a balance of power that improved diplomatic relations between the US and Russia.

On the flip side, we have witnessed the extremes of power imbalance between the US and other world nations, which saw the US, influence the decision to invade Iraq. From these examples, this paper highlights the importance of attaining a balance of power among world nations. If such an equilibrium is not achieved, powerful states will always impose their will over other states.

Brown, C. (2001) Understanding International Relations . London, Palgrave Macmillan.

Ikenberry, J. (2008) The Balance of Power in International Relations: Metaphors, Myths, and Models . Web.

Little, R. (2007) The Balance Of Power In International Relations: Metaphors, Myths And Models . Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Mayall, J. (1980) The End Of The Post-War Era: Documents On Great-Power Relations, 1968-1975 . Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Pandey, S. (2009) Concept of Balance of Power in International Relations . Web.

Ross, R. (1993) China, the United States, and the Soviet Union: Tripolarity and Policy Making In the Cold War . New York, M.E. Sharpe.

Sheehan, M. (1996) The Balance Of Power: History And Theory . London, Routledge.

- Communism Collapse in the USSR

- How the Soviet Union Caused War Using Communism

- Communism in the Soviet Union

- The Feeling of Rationality: The Meaning of Neuroscientific Advances for Political Science

- MDG Poverty Goals May Be Achieved, but Child Mortality Is Not Improving

- Chinese Presence in Africa

- Australian Open Policy Towards North Korea

- United States Foreign Policy and Greece

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, March 27). Balance of Power Concept in International Relations. https://ivypanda.com/essays/balance-of-power/

"Balance of Power Concept in International Relations." IvyPanda , 27 Mar. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/balance-of-power/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Balance of Power Concept in International Relations'. 27 March.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Balance of Power Concept in International Relations." March 27, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/balance-of-power/.

1. IvyPanda . "Balance of Power Concept in International Relations." March 27, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/balance-of-power/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Balance of Power Concept in International Relations." March 27, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/balance-of-power/.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

balance of power

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Academia - The Balance of Power in World Politics The Balance of Power in World Politics Summary and Keywords The Balance of Power in World Politics

- EHNE Digital Encyclopedia - European Balance of Power

- Walden University - What Is the Balance of Power and How Is It Maintained?

balance of power , in international relations , the posture and policy of a nation or group of nations protecting itself against another nation or group of nations by matching its power against the power of the other side. States can pursue a policy of balance of power in two ways: by increasing their own power, as when engaging in an armaments race or in the competitive acquisition of territory; or by adding to their own power that of other states, as when embarking upon a policy of alliances.

The term balance of power came into use to denote the power relationships in the European state system from the end of the Napoleonic Wars to World War I . Within the European balance of power, Great Britain played the role of the “balancer,” or “holder of the balance.” It was not permanently identified with the policies of any European nation, and it would throw its weight at one time on one side, at another time on another side, guided largely by one consideration—the maintenance of the balance itself. Naval supremacy and its virtual immunity from foreign invasion enabled Great Britain to perform this function, which made the European balance of power both flexible and stable.

The balance of power from the early 20th century onward underwent drastic changes that for all practical purposes destroyed the European power structure as it had existed since the end of the Middle Ages . Prior to the 20th century, the political world was composed of a number of separate and independent balance-of-power systems, such as the European, the American, the Chinese, and the Indian. But World War I and its attendant political alignments triggered a process that eventually culminated in the integration of most of the world’s nations into a single balance-of-power system. This integration began with the World War I alliance of Britain, France , Russia, and the United States against Germany and Austria-Hungary . The integration continued in World War II , during which the fascist nations of Germany, Japan, and Italy were opposed by a global alliance of the Soviet Union, the United States, Britain, and China. World War II ended with the major weights in the balance of power having shifted from the traditional players in western and central Europe to just two non-European ones: the United States and the Soviet Union . The result was a bipolar balance of power across the northern half of the globe that pitted the free-market democracies of the West against the communist one-party states of eastern Europe. More specifically, the nations of western Europe sided with the United States in the NATO military alliance, while the Soviet Union’s satellite-allies in central and eastern Europe became unified under Soviet leadership in the Warsaw Pact .

Because the balance of power was now bipolar and because of the great disparity of power between the two superpowers and all other nations, the European countries lost that freedom of movement that previously had made for a flexible system. Instead of a series of shifting and basically unpredictable alliances with and against each other, the nations of Europe now clustered around the two superpowers and tended to transform themselves into two stable blocs.

There were other decisive differences between the postwar balance of power and its predecessor. The fear of mutual destruction in a global nuclear holocaust injected into the foreign policies of the United States and the Soviet Union a marked element of restraint. A direct military confrontation between the two superpowers and their allies on European soil was an almost-certain gateway to nuclear war and was therefore to be avoided at almost any cost. So instead, direct confrontation was largely replaced by (1) a massive arms race whose lethal products were never used and (2) political meddling or limited military interventions by the superpowers in various Third World nations.

In the late 20th century, some Third World nations resisted the advances of the superpowers and maintained a nonaligned stance in international politics. The breakaway of China from Soviet influence and its cultivation of a nonaligned but covertly anti-Soviet stance lent a further complexity to the bipolar balance of power. The most important shift in the balance of power began in 1989–90, however, when the Soviet Union lost control over its eastern European satellites and allowed noncommunist governments to come to power in those countries. The breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 made the concept of a European balance of power temporarily irrelevant, since the government of newly sovereign Russia initially embraced the political and economic forms favoured by the United States and western Europe. Both Russia and the United States retained their nuclear arsenals, however, so the balance of nuclear threat between them remained potentially in force.

Hume Texts Online

Of the balance of power ..

I T is a question whether the idea of the balance of power be owing entirely to modern policy, or whether the phrase only has been invented in these later ages? It is certain, that Xenophon [1] , in his Institution of Cyrus , represents the combination of the Asiatic powers to have arisen from a jealousy of the encreasing force of the Medes and Persians ; and though that elegant composition should be supposed altogether a romance, this sentiment, ascribed by the author to the eastern princes, is at least a proof of the prevailing notion of ancient times.

In all the politics of Greece , the anxiety, with regard to | the balance of power, is apparent, and is expressly pointed out to us, even by the ancient historians. Thucydides [2] represents the league, which was formed against Athens , and which produced the Peloponnesian war, as entirely owing to this principle. And after the decline of Athens , when the Thebans and Lacedemonians disputed for sovereignty, we find, that the Athenians (as well as many other republics) always threw themselves into the lighter scale, and endeavoured to preserve the balance. They supported Thebes against Sparta , till the great victory gained by Epaminondas at Leuctra ; after which they immediately went over to the conquered, from generosity, as they pretended, but in reality from their jealousy of the conquerors [3] .

Whoever will read Demosthenes 's oration for the Megalopolitans , may see the utmost refinements on this principle, that ever entered into the head of a Venetian or English speculatist. And upon the first rise of the Macedonian power, this orator immediately discovered the danger, sounded the alarm throughout all Greece , and at last assembled that confederacy under the banners of Athens , which fought the great and decisive battle of Chaeronea .

It is true, the Grecian wars are regarded by historians as wars of emulation rather than of politics; and each state seems to have had more in view the honour of leading the rest, than any well-grounded hopes of authority and dominion. If we consider, indeed, the small number of inhabitants in any one republic, compared to the whole, the great difficulty of forming sieges in those times, and the extraordinary bravery and discipline of every freeman among that noble people; we shall conclude, that the balance of power was, of itself, sufficiently secured in Greece , and needed not to have been guarded with that caution which may be requisite in other ages. But whether we ascribe the shifting of sides in all the Grecian republics to jealous emulation or cautious politics , the effects were alike, and every prevailing power was sure to meet with a confederacy against it, and that often composed of its former friends and allies.

The same principle, call it envy or prudence, which produced the Ostracism of Athens , and Petalism of Syracuse , and expelled every citizen whose fame or power overtopped the rest; the same principle, I say, naturally discovered itself in foreign politics, and soon raised enemies to the leading state, however moderate in the exercise of its authority.

The Persian monarch was really, in his force, a petty prince, compared to the Grecian republics; and therefore it behoved him, from views of safety more than from emulation, to interest himself in their quarrels, and to support the weaker side in every contest. This was the advice given by Alcibiades to Tissaphernes [4] , and it prolonged near a century | the date of the Persian empire; till the neglect of it for a moment, after the first appearance of the aspiring genius of Philip , brought that lofty and frail edifice to the ground, with a rapidity of which there are few instances in the history of mankind.

The successors of Alexander showed great jealousy of the balance of power; a jealousy founded on true politics and prudence, and which preserved distinct for several ages the partition made after the death of that famous conqueror. The fortune and ambition of Antigonus [5] threatened them anew with a universal monarchy; but their combination, and their victory at Ipsus saved them. And in subsequent times, we find, that, as the Eastern princes considered the Greeks and Macedonians as the only real military force, with whom they had any intercourse, they kept always a watchful eye over that part of the world. The Ptolemies , in particular, supported first Aratus and the Achaeans , and then Cleomenes king of Sparta , from no other view than as a counterbalance to the Macedonian monarchs. For this is the account which Polybius gives of the Egyptian politics [6] .