- How it works

Useful Links

How much will your dissertation cost?

Have an expert academic write your dissertation paper!

Dissertation Services

Get unlimited topic ideas and a dissertation plan for just £45.00

Order topics and plan

Get 1 free topic in your area of study with aim and justification

Yes I want the free topic

Youth Crime Dissertation Topics – A Bunch of Topics Based on Recent Reports

Published by Owen Ingram at December 29th, 2022 , Revised On August 15, 2023

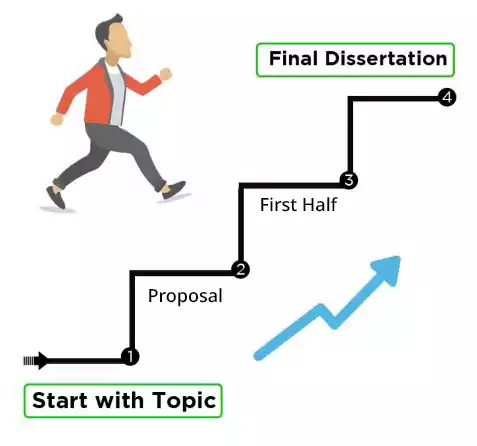

Writing about youth crime can be educational and eye-opening. This area of study will make you consider ideas you hadn’t considered before or perhaps it did, which is why you decided to write a dissertation on a youth crime research topic. So now that you know where you’re going, all you need is a good youth crime thesis or dissertation idea to get started.

Make a decision based on what motivates you. If you are passionate about your topic, you want your audience to be equally interested. Your readers should pick up on your understanding of and enthusiasm for the project. If you want them to read more or investigate this topic independently, you must pique their interest.

Hire an Expert Writer

Orders completed by our expert writers are

- Formally drafted in an academic style

- Free Amendments and 100% Plagiarism Free – or your money back!

- 100% Confidential and Timely Delivery!

- Free anti-plagiarism report

- Appreciated by thousands of clients. Check client reviews

Youth Crime Dissertation Topics

Use Them And Let Them Inspire Your Dissertation

- How do the media affect youth crime? Do specific films, video games, or song lyrics glorify violence?

- Should young offenders face adult courts? Do people become irredeemable if they commit crimes before reaching adulthood?

- Do juvenile correctional facilities help young offenders get better or train them to be more seasoned criminals?

- Is the only way to rehabilitate young criminals by sending them to an institution for corrections or possibly prison, or is there another alternative?

- What impact does the family environment have on young offenders? Does the history of youth misdeeds in the family matter?

- Are foster kids more inclined to misbehave? Do they suffer from a drawback?

- Are offspring of teen moms more or less likely to grow up to commit crimes? Do kids who don’t have father figures have a higher risk of misbehaviour?

- What proportion of young criminals are successfully treated? Do people with criminal records automatically disqualify themselves from specific professions? Does imposing a sentence make a bad situation worse?

- Are kids committing crimes out of obligation or a desire for attention?

- Do people or society develop prejudices against young offenders? What impact does that have on the kids?

- What signs help you spot the beginning of criminal behaviour? How can we stop children from becoming criminals?

- Is there a difference in sentencing between male youth criminals and female youth criminals?

- Do drug usage and underage drinking play a part in why young people commit crimes?

- How can sexual offences against youth crime be reduced?

- Is the primary motivation for significant crimes committed by youth often money?

- Does the use of drugs cause youth to commit crimes because it makes them more aggressive?

- What is the black window killing epidemic among young offenders?

- Do young offenders behave better when they move to a new country?

- How do youth offenders alter as they pass a particular immaturity threshold?

- Should there be substantial control over what young people do when socialising in public spaces?

Writing a youth crime dissertation is not an easy task. You need a stellar topic and impeccable research skills to accomplish a good grade. We have mentioned a plethora of unique and interesting dissertation topics on youth crime. Pick a topic from our list or get inspired by them to make your own topic. Now that you have your topic start your research and ace your dissertation.

Or read about dissertation writing services to see how our experts can help you achieve your desired goals.

Free Dissertation Topic

Phone Number

Academic Level Select Academic Level Undergraduate Graduate PHD

Academic Subject

Area of Research

Frequently Asked Questions

How to find youth crime dissertation topics.

To find youth crime dissertation topics:

- Study crime statistics and trends.

- Research social and economic factors.

- Examine legal and policy issues.

- Analyze prevention programs.

- Explore media’s portrayal.

- Select a focused and relevant angle for in-depth study.

You May Also Like

Family law dissertation topics are included in a section of UK law. This topic is more of a minor category in terms of your broader research. Family law dissertations are challenging.

Need interesting and manageable fashion and culture dissertation topics or thesis? Here are the trending fashion and culture dissertation titles so you can choose the most suitable one.

Need interesting and manageable Marketing dissertation topics or thesis? Here are the trending Operations Marketing dissertation titles so you can choose the most suitable one.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Persuasive Speeches: Youth Crime

- Social Media

- Youth Crime

- Mental Health

- Single Sex Schooling

Young people can experience crime and violence as victims, witnesses or offenders. This can occur in their home or the wider community. For young people, exposure to crime and violence can have potentially damaging impacts that lead to a range of negative health, educational, social, emotional and behavioural, and housing outcomes across their lifespan.

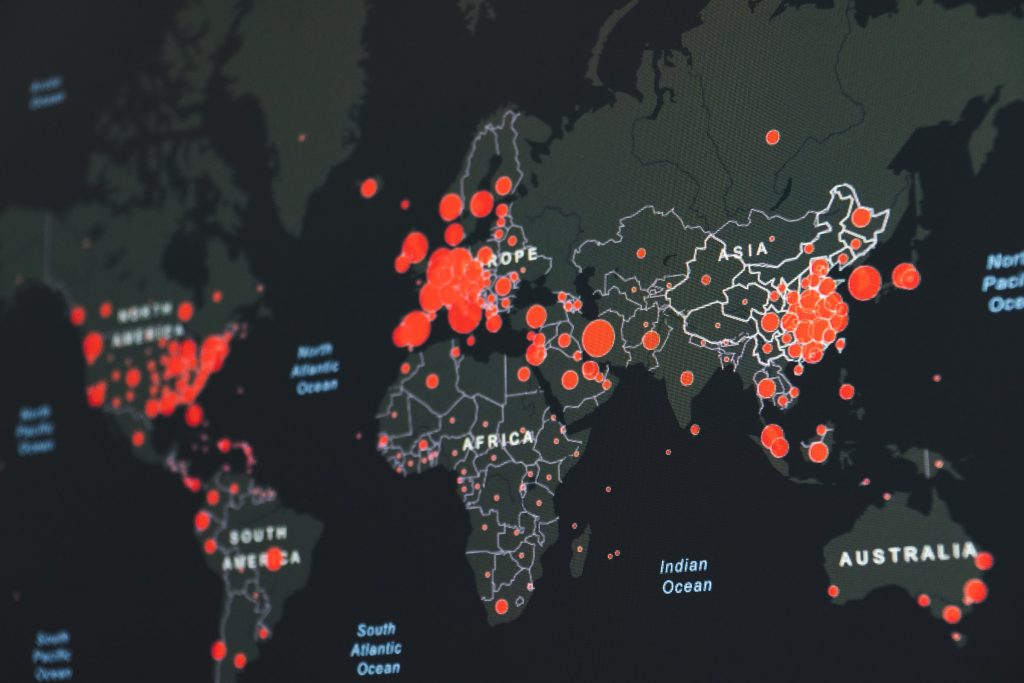

Note: Image of Root causes of Crime, From "The Root Causes of Crime" , by Project Calgary, n.d, (http:www.project.org/d2f_the_root_causes_of_crime)

- << Previous: Bullying

- Next: Mental Health >>

- Last Updated: Mar 27, 2024 9:06 AM

- URL: https://icentre.vnc.qld.edu.au/persuasivespeeches

Criminology, Sociology and Policing at Hull

Student research journal, the impact of covid-19 on youth offending.

When estimating the potential impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on youth offending, it is important to consider traditional theories of crime. This literature review aims to determine which of the secondary impacts of the pandemic have influenced crime during the crisis and can predict changes to crime rates in the future. Existing theories of crime such as ‘anomie’, control theories and the right realist perspective of offending can identify crime predictors and risk factors that may be aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The following review contains secondary research of personal accounts from individuals based on their experiences throughout the pandemic, literature on traditional theories of crime can be compared with the main issues raised by this research. The focus of the review is youth offending in the UK.

Several theories have been used to explain the impacts of COVID-19 on criminal activity, for example, routine activities theory can help to explain reductions in crime following the national lockdown. Routine activities theory may be able to explain rises in crime when government restrictions are lifted, as opportunities for offending are to increase. Theories surrounding social disorganisation can be used to draw links between unemployment and youth crime. Disruptions in the structure of society are expected to increase criminal activity due to an increase in anomic frustration. Control theory can be used to investigate the impacts of COVID-19 on the relationships between individuals, these relationships can be considered in relation to offending to predict future criminality. Traditional theories of crime can help explain changes in crime throughout and following the pandemic.

However, research on the secondary impacts of COVID-19 is limited due to the unprecedented circumstances of the pandemic. There has been limited time to gather data on the outcomes that have followed the outbreak of COVID-19.

Author: Leanne Jade Knowles

BA (Hons) Criminology with Psychology, May 2021

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the youth

3. Social disorganisation and strain theory

4. Control theory

5. Right realism

6. Conclusion

Bibliography

Acknowledgements.

Firstly I would like to express my appreciation to my dissertation supervisor, Dr Margarita Zernova for her support throughout my research process. I would also like to extend my thanks to Mr Edward Knowles for his continuous support and encouragement throughout my past three years of university.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 is a contagious airborne disease that is most commonly contracted through contact with an infected person as it is transmitted through droplets from their mouth or nose (World Health Organisation, 2020). The first recorded case of the virus was contracted in China during December of 2019. By the beginning of 2020, COVID-19 had spread to multiple countries including Hong Kong, the United States of America, France and Australia. In January of 2020 COVID-19 also began to impact the United Kingdom, as at this time the first two cases in the country were recorded. The primary impacts of the pandemic quickly became a concern for the government and the public as for many people contracting the virus was fatal. As cases began to rise in many different countries, deaths due to COVID-19 also began to increase. The severity of the pandemic began to exceed the fatality rate and infection rate of previous outbreaks of other diseases, this prompted the government to put measures in place in order to control the spread of COVID-19 and reduce the transmission rate (Kantis et al, 2021).

In March 2020, the government placed the United Kingdom in a national lockdown, people were urged to stay at home whenever possible. The aim of the initial national lockdown was to reduce unnecessary contact between individuals in order to slow down the spread of the virus. The government enforced strict rules to avoid overwhelming the National Health Service (NHS). If the NHS were to become overwhelmed with the number of patients with COVID-19, there may have been a shortage of treatment facilities available for the vast amounts of individuals suffering from the disease. In order for the NHS to be able to cope with treating and supporting those with the virus, individuals were told to stay in their homes and limit any contact with individuals outside their household (Torjesen, 2020). The lockdown caused drastic changes to the structure of society; educational institutions and businesses were forced to close, social interaction outside of households was limited and large social gatherings were prohibited. The consequences that followed the closures of schools and businesses affected the majority of the population. The economy severely declined as a result of businesses being forced to close, school children were limited to remote learning and the impacts of isolation damaged the mental health of many individuals (Singh & Singh, 2020: 168-172). By the end of July 2020, it had become mandatory to social distance and wear a face-covering in some public spaces throughout the UK, such as public transport and supermarkets. Those who failed to comply with these rules risked receiving a fine of up to £100 (GOV, 2020). The right realist perspective of crime considers the consequences of using fines as a punitive measure, and the impacts of fines on different groups in society (Evans, 2011: 72). However, the government’s initial response, including the national lockdown and social distancing measures, impelled secondary factors which could have long-lasting impacts on society. The COVID-19 pandemic forced individuals to adapt their daily routines and temporarily changed the structure of society. Theories surrounding social disorganisation and crime can explore the potential implications of the changes to society’s structure following the start of the pandemic.

This literature review includes discussion about the many negative secondary impacts of the pandemic and national lockdowns on the young people living in the United Kingdom in relation to existing theories of crime. Traditional theories of crime can be used to understand changes in crime rates during the COVID-19 crisis and what to expect following the pandemic. Predictions about increases and decreases in future crime can help inform proactive measures to reduce crime. I will outline how the younger generation responded to the changing circumstances as the pandemic altered their lives and will later discuss how these circumstances could lead an individual down a criminal path. Crime statistics following March of 2020 show a decline in many types of crime after the introduction of the first national lockdown, fluctuations in crime rates throughout the pandemic may reflect how society responds to crisis (Office for National Statistics, 2020). The secondary impacts revealed new risk factors of crime and worsened existing issues within society, which may affect crime rates moving forward. There were drastic changes to the economy following the closure of many businesses, these changes could create risk factors of crime. The impacts of the national lockdown on relationships between families and peers can be linked to control theories of crime. Secure relationships have been acknowledged as elements of desistance by control theorists. Breakdown of relationships may influence crime rates following the easing of government restrictions (Hirschi, 1969).

The first national lockdown appeared to have affected crime rates, as most types of criminal behaviours were reported significantly less (Abrams, 2021). Traditional theories of crime, such as routine activities theory, may explain why criminal activity would reduce in response to COVID-19 restrictions. Different perspectives on delinquency can help to predict future trends in offending behaviour, based on possible secondary impacts of the pandemic on young people. Government guidance about social distancing and wearing face coverings in public spaces, as well as the national lockdowns completely altered the way in which society functions. The majority of the UK population were forced to adapt their lifestyles in order to adhere to government restrictions and reduce their risk of contracting COVID-19 (Verma & Prakash, 2020: 7357-7358).

2. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the youth

The negative implications of the national lockdowns put in place by the UK government to slow the spread of COVID-19, range from concerns about the mental wellbeing of young people to rising levels of unemployed youth. The COVID-19 pandemic forced most young people to restructure their lives in order to abide by government restrictions. National lockdowns limited social interactions between people and severely damaged the economy. New concerns surrounding school and employment surfaced when young people were encouraged to stay within their households.

Marsh (2021) draws upon the mass unemployment of many young people as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. When many businesses were deemed non-essential and forced to close, many young people, including students were placed in the government’s furlough scheme. This furlough scheme allowed many different individuals to maintain most or some of their income despite being unable to attend their workplace. However, the closure of businesses left many young people uncertain about if their jobs would remain available to them after the lockdowns. Students in pursuit of qualifications for their desired jobs were left uncertain when the competition for even low-paid roles rapidly increased, as many large businesses closed permanently. The levels of unemployment amongst young people reached higher levels than the past few decades, this indicates the severe impact of the pandemic on the economy. Young people will need to continue competing against others for work until the economy begins to recover from the impacts of COVID-19, leaving many financially unstable or unemployed (Marsh, 2021).

Young people spending extended periods of time within their household, with only their close family to interact with are likely to feel bored and isolated. Other young people may be drawn to disobeying government advice about gathering with individuals from other households in order to escape this boredom. There is a possible link between boredom and offending, as offending can provide excitement and gratification (Steinmetz, Schaefer & Green, 2017: 355). Spending time outside the household is more appealing for those families affected by the growing pressures on family relationships due to unemployment or the closure of schools. The closure of schools brings a lack of structure to the lives of many students, their routines are completely adapted to remote learning, which for some may exclude physical exercise and social interactions. In Scotland, it was reported that younger people were more likely to lose their jobs or become part of the furlough scheme than their elders. Poverty in the UK increased as a result of the mass unemployment crisis, with more people struggling to afford housing and food than before the pandemic (Scottish Government, 2020).

Education institutions such as schools and universities were closed during the national lockdowns to protect both children and their families from the virus. The closure of schools limited the interactions between people from different households. However, being forced to study by remote learning from home is expected to harm young people in other ways despite protecting them from the virus. Researchers have already started to investigate the psychological impacts of the closure of schools on children. Stress and depression have been reported as consequences for closing the schools, the stress could be derived from uncertainty surrounding their academic success or concern about the virus itself, it may also stem from feeling isolated and separated from their peers. The extent of the psychological effects on children will unfold as time goes on, providing a better understanding of how COVID-19 has affected young people. As a new reliance on technology for education emerged, the socioeconomic differences between areas and households were highlighted. Internet access and ownership of the technological means to engage with remote learning are not readily available for all students, thus putting many young people at an academic disadvantage. Individuals with less access to online education resources are further excluded from academic success and isolated from communicating with their teachers and peers through technological means (Petretto et al, 2020: 189). Many young people were left uncertain about whether their exams would go ahead or if they would be able to learn as efficiently in their homes as they would at school with their usual circumstances. The social element of school and university can be crucial for the development of young minds, the lack of social interactions with their peers caused by the closure of educational institutions can have a negative impact on mental health. The closure of schools also denies children an opportunity to participate in physical education lessons and sports clubs, affecting both their physical and mental health in some cases. For other young people, the uncertainty about the government’s strategies for coping with the pandemic fuelled fear surrounding the impacts of the virus. Those who believe the government has demonstrated poor leadership skills may lack faith in the government going forward (Hill, 2020).

The closure of schools has inhibited the learning of many young people. Some students have struggled to obtain their academic targets and feel as though they have lacked sufficient education during the national lockdowns. The young people could not have predicted nor prevented the changes to education in 2020 and 2021, and therefore may need additional support following the national lockdowns. The government introduced a national tutoring programme, based on research surrounding the success of small group tutoring. Children from lower-income families were less likely to have access to private tutoring in pre-COVID-19 circumstances. The national tutoring programme is in place to support as many disadvantaged students as possible, including those from lower-income backgrounds. The programme aims to improve the education of the students who were most affected by the pandemic, regardless of their background. The government had promised to spend £350,000,000 on 15,000 tutors with the aim of supporting around 250,000 children. Education plays a significant role in the lives of young people, it helps them develop and socialise while helping them achieve the qualifications they need to succeed in their desired job roles in the future. While the pandemic has affected every child across the country, the programme is for those who are most disadvantaged as a result of COVID-19, their academic performance can reflect the effects it has had on their education (GOV, 2020).

Due to remote learning becoming a prominent method for delivering education during the pandemic, the government has taken measures to support young people with technological struggles throughout the closure of schools. Over 1,300,000 laptops and tablets were allocated to students in need of financial support to help them to adapt to remote learning. Others were at a disadvantage compared with other students because they lacked adequate internet access, this made it difficult to access online lessons and other online resources. The government aimed to collaborate with mobile network providers to ensure students were able to benefit from remote learning despite their limited access to the internet (GOV, 2020). While the central aim of the programmes is to give young people the opportunities and resources to attain similar levels of education as they would in schools, the schemes may indirectly affect the crime rates following the pandemic. Education can be used as a tool to help individuals desist from crime and prepare them for their future employment endeavours.

According to the Office for National Statistics, between April and May of 2020, there was a 32% decrease in total recorded crime. The introduction of government restrictions and lockdown measures in March 2020 likely contributed to this significant reduction in crime. Around 20% of individuals surveyed were witnesses to anti-social behaviour, however, they had noticed a decrease in this offending behaviour following the lockdown rules. Between April and May 2020, there were reductions in reported theft and burglary, this is believed to be due to the lack of opportunities for offenders. Despite significant reductions in many deviant behaviours, drug offences have continued to increase. From May 2019 to May 2020 there was a 44% increase in reported drug offences (Office for National Statistics, 2020). COVID-19 had affected the way in which the criminal justice system was organised, court hearings were limited due to social distancing restrictions. This meant that cases deemed more serious were prioritised, while other cases were reconsidered. For less serious cases, individuals were assessed for risk to the public and cases were either delayed or dropped altogether if the offenders were expected to cause less harm to the public. The implications on the court system may include misrepresentation of criminal conviction statistics, and less serious crimes may appear to have decreased as a result of this (Grierson, 2020).

Crimes such as domestic abuse and child abuse may have risen due to families spending more time at home, many people were unable to attend work or school. The government’s furlough scheme allowed for many businesses to survive prolonged closures and for the majority of the population to stay at home to avoid catching the COVID-19 virus. Staying at home may have protected people from coronavirus but for those affected by domestic abuse are vulnerable to other threats, staying home can leave some individuals in an unsafe environment. By urging the public to stay home for their own safety, the government had to make the assumption that people would be safe in their homes, without recognising how seriously victims of domestic violence would be affected by this. The mental health of many individuals has severely declined which may increase the tension within households further (Bradbury-Jones & Isham, 2020: 2047). It is not only those in abusive relationships who are vulnerable to increased harm in their homes, there has been a rise in calls made to child abuse helplines. As a response to the closure of schools, education was shifted to remote learning, this meant children were expected to spend all of their time at home. Those who were already vulnerable to abuse by their caregiver were exposed to more time with their abusers (Office for national statistics, 2020).

The significant reductions in crime may be a result of scarce opportunities for some types of crime while the government’s restrictions on movement were in place. Most “non-essential” travel was prohibited and people were unable to drink alcohol in public settings such as bars and restaurants. The government urged the majority of the population to remain in their homes as much as possible, this may explain the reduction in different types of crime. A reduction in robbery may be due to a reduction in opportunities for offenders. As more individuals were occupying their houses than before the lockdown, it became more difficult to enter another individual’s property without being detected by the homeowner. As hospitality businesses such as bars, restaurants and hotels were forced to close, people had fewer reasons to leave their houses in the evenings. This collective change in behaviour left fewer opportunities for offenders to commit crimes such as theft or violent crime, explaining a reduction in these areas (Hodgkinson & Andresen, 2020: 6-10). However, when the virus is controlled and restrictions are eased by the government, we can expect changes to the low crime rates. “Non-essential” businesses will be allowed to reopen and “non-essential” travel will become more acceptable again. Re-integrating individuals back into society provides more opportunity for individuals to offend. The effects of the pandemic on mental health and family relationships will not disappear after government restrictions are lifted, and these issues may influence offending behaviour even when people are less restricted (Miller & Blumstein, 2020: 518-522).

The secondary effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth crime will unfold as time goes on. Crime rates were significantly lower during the pandemic than they have been in previous years, so when society reverts back to its normal structure, perhaps crime rates will follow patterns of previous years. When the lockdowns are lifted and the restrictions are eased, recorded crime may reflect criminal activity more accurately. The circumstances could lead to increases in certain crimes due to the long-term impacts on people’s lives.

3. Social disorganisation and strain theory

This chapter will outline the social disorganization and strain theories of crime, these explanations for youth crime may explain a potential rise in crime rates as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the impacts of the national lockdowns on youth crime are still to be determined as time goes on, traditional theories of crime may give a helpful insight into the potential trends that may emerge in the near future. The multiple national lock-downs that have taken place in 2020 have severely affected the economy, including large successful corporations, smaller businesses and individuals trying to earn a living wage. The government provided a generous furlough scheme for those who were unable to work throughout the pandemic, however, the economy has still suffered. The furlough scheme and the economic damage has directly and indirectly affected the lives of young people (Marsh, 2021).

Émile Durkheim (1952: 241-277) developed the theory of ‘anomie’, this theory can help to outline the effect of social order on crime rates. Anomie is a feeling of distress and frustration when an individual is unable to relate to the norms or laws of society. It can also occur when social change takes place, anomie can affect individuals even when the norms of society suit the majority. When employment opportunities are depleted, the effects of anomie may feel amplified for some groups (Buchanan, 2018: 2). Durkheim studied suicide rates in different countries and investigated the correlation between suicide and social order. He theorised that social disorganisation would draw people to suicide because disorganisation in society would create anomic frustration amongst the population. He also stated that anomie can drive individuals to commit violent acts too. According to Durkheim, individuals aim to achieve the life goals prescribed and shared by society. By adhering to social norms, individuals can achieve society’s goals and be integrated comfortably into their community. Failure to achieve the common perception of success held by society increases the anomic feelings an individual has (TenHouten, 2016: 480).

Emile Durkheim (1952) discussed suicide rates in relation to social disorganisation, he noticed trends between crises and changes within society. The COVID-19 pandemic has forced many individuals out of employment and separated many from their social circles. Social distancing is a term introduced to describe when individuals actively avoid close contact with others. People were expected to maintain a distance of at least a metre between individuals when interacting with them or passing them. This practice was a key technique to help reduce an individual’s risk of spreading or contracting the virus from other people. The distance between individuals was to prevent infected water droplets from reaching another person. Social distancing became an expectation or rule in most establishments, which was a great social change for many individuals. Distancing from others in public spaces was not a routine practice before the pandemic and many buildings were not designed with the intention to provide a 1-metre radius around each person (Romania, 2020: 64).

Robert Merton (1938: 676) expanded on Durkheim’s idea of anomie and applied the work to explaining criminal behaviour. Merton maintained the concept of anomic frustration but proposed different responses to this, as not every individual commits suicide after failing to reach the culturally prescribed goals. Merton instead divided people into categories depending on their ability to achieve the goals, in addition to the extent of their means of achieving the goals. Individuals who accept both society’s goals and their personal means of achieving the goals, are categorised as ‘conformists’. The ‘conformist’ category consists of those using legitimate means to work towards their goals, even if those goals are unrealistic. The ‘innovation’ category on the other hand consists of groups that accept the goals prescribed by society but reject their means of achieving them. For instance, a goal may be to achieve financial success, but innovators may find the achievement of this goal unrealistic with the means they have. So these individuals may be drawn to illegitimate means, which may include selling drugs or stealing. According to Merton (1938), ‘retreatism’ is rejecting both the goals of society and their personal means of achieving them, this may lead to escapism methods such as drug use and homelessness. ‘Ritualism’ is rejecting the goals but accepting the means available to them. Finally, ‘rebellion’ is when individuals seek new goals and find new means to achieve these goals. Merton would argue that most of the categories are deviant, conformists are the only group that Merton found acceptable (Merton, 1938: 677-678). Merton’s expansion on the traditional theory of anomie has been criticised, some theorists argue that anomic frustration is an invalid justification for delinquency. Anomie can be used to explain trends in suicide rates but cannot explain all crime rates (Besnard, P, 1988: 94).

In instances of economic crisis, the ‘innovation’ category could expand because more people become dissatisfied with the means available to them. When struggling to find legitimate employment opportunities, individuals may seek alternative ways of earning money, perhaps for survival or for wealth and leisure. The ‘retreatism’ category may also expand as homelessness becomes an epidemic. This may also create a new influx of crime as homeless individuals are forced to compete for resources (Boobis & Albanese, 2020). Large social changes such as the COVID-19 pandemic can weaken an individual’s acceptance of their scarce legitimate means, this can push them into the ‘innovation’ category as their likelihood for success decreases. The options widen when illegitimate means are considered, this way individuals still have a chance for achieving their goals, however, this involves more risks. Baron found that a sample of young homeless men were more driven to commit crime by the lack of legitimate means to achieve their goals than by the pursuit of their financial goals (Baron, 2011).

Jock Young (2007) attempted to apply Merton’s ideas to contemporary society following the industrial revolution. Young researched what impacts de-industrialisation could have on society and began to draw links between these changes to society and delinquency. Young acknowledged the huge reduction of manual jobs that followed the industrial revolution and found high unemployment rates, leaving many working-class individuals economically excluded from society. The lack of jobs and structure within society at that time saw a rise in anomic frustration. Young highlights the significant role that the media played at that time, endorsing and advertising unrealistic goals and lifestyles. The media present a correlation between a wealthy and accomplished lifestyle and consumerism, attracting the population to share goals that they wish to achieve. For many, culturally prescribed goals included high consumption of material goods and relied on having economic success. For many working-class individuals at the time, these goals were attractive yet unachievable. Young argued that when those with fewer means of achieving the culturally prescribed goals realise failure is probable, they are drawn to commit crimes. The causes of crime drawn upon by Young have only been amplified since the theory was established. In terms of media, people have more accessible means to publicise their accomplished lifestyles which can fuel anomic frustration. Young supported Merton’s theory that anomic frustration can lead to crime, he also discussed methods of escapism for those who are unable to commit crimes, binge-drinking or drug use for instance. This perspective can help explain rises in drug use and distribution. Substance use as a form of escapism may also lead to other types of crime that have less of a financial motive (Young, 2007: 45-50).

COVID-19 disrupted the structure of society in many ways, it was no longer acceptable for individuals to carry out their daily routines, many individuals experienced changes to their livelihoods and social lives. The United Kingdom faced social and economic crises as cases of COVID-19 began to rise to uncontrollable levels. Merton recognised the impacts of social and economic crises on crime, individuals cope with alterations to the social structure by acting on their impulses. COVID-19 saw the temporary closure of many businesses in the UK. Throughout the national lockdowns, many hospitality establishments were forced to close in an attempt to reduce the interactions between people. These closures were seen as essential for slowing the rate of transmission of COVID-19. Many businesses had to go into administration as a consequence of these prolonged closures, many individuals were left unemployed and their legitimate means for achieving monetary success became increasingly scarce. While many individuals continue to search and compete for employment, others are left without a stable income, even those still upholding their original financial goals. This is likely to create anomic frustration amongst the population, this frustration may attract some groups to criminal activity (Keogh-Brown et al, 2020).

During the national lockdowns, most businesses were forced to close temporarily, leaving many people out of work. The Government introduced a furlough scheme which provided individuals with a portion of their normal income in the time they were unable to work.

Furlough allowed families to survive despite the closure of businesses, however, few companies received over 80% of their usual income. The scheme was intended to provide financial support but could have effects on changing crime rates. For some, the furlough scheme would have provided enough money to maintain the culturally prescribed goals, this may prevent or reduce anomic frustration amongst individuals. However, government intervention could not prevent the disorganisation that followed the pandemic, people’s lives were affected by many other factors (Szulc & Smith, 2021: 632).

Community crime prevention (Jeffery, 1971) is an approach to deter young individuals from criminality and is focused on those who are expected to commit crimes. This approach involves changing the social environment to remove possible risk factors. Poverty and deprivation have been linked to crime, so supporting those living in impoverished areas may reduce crime. The aim of community crime prevention is to provide young people with fulfilling opportunities, this way they are less likely to offend as they have more aspirations and chance of success (Welsh & Farrington, 2012: 4-10). In response to COVID-19, the government introduced schemes that could have similar effects to community crime prevention. Crime prevention is not the primary goal of the schemes but reintegrating individuals into society and employment may impact crime rates. The government promised an apprenticeship scheme, which involved giving employers “£2,000 for each new apprentice they hire aged under 25” and “£1,500 for each newly recruited apprentice aged 25 and over” (GOV, 2020). The scheme encourages employers to provide jobs for more employees which benefits both their businesses and the economy. The aim of this scheme is to provide a source of income for young people and help to reintegrate them into employment following the national lockdowns. This in turn is expected to have similar effects to community crime prevention, as it provides young people with legitimate means for earning money and can help them develop skills for future employment. Other young people who are seeking employment after education are offered the opportunity to further their studies for another year if they are unable to find a job that suits them (Evans, 2011: 19-20).

While social disorganisation has been linked to increased crime rates throughout previous decades, the extent to which the COVID-19 crisis will increase crime is yet to be discovered. However, previous research related to unemployment, anomie and societal change can be applied to help predict potential changes in youth offending following the pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic has made it difficult for many people to maintain a comfortable income, making their goals further out of reach. Assuming Merton’s ‘anomie’ still applies to contemporary society, we can expect increases in crime amongst young people. Government interventions, such as the furlough scheme, may help to reduce the impacts of the pandemic on crime. However, financial instability is not the only possible contributing factor to crime that has been aggravated by the crisis.

4. Control theory

This chapter investigates how an individual’s bond with society may lead to their offending behaviour, and discusses whether the impacts of COVID-19 have damaged or aggravated the bonds between young people and society. The chapter focuses on desistance and techniques individuals may utilize to justify deviant behaviour. Control theorists aim to make a distinction between individuals who offend over the course of their life and those who do not. Control theorists argue that there must be a reason why certain people do not offend in their lifetime and why some offenders are deterred from crime, the term desistance can help to explain why individuals may abstain from offending. Desistance can depend on several factors, for example; how dedicated an individual is to a routine or responsibility in their life, or how dedicated they are to maintain new relationships (Healy, 2017: 1-3).

Control theorists emphasize the importance of stable employment and willingness to work for desistance to be effective. This idea assumes that individuals without structure and stability in their daily lives are more vulnerable to criminality because their bond to society would be weaker. Strong and stable relationships can be key elements of desistance from crime, relationships can provide support and require emotional investment that can deter an individual from offending (Cid & Martí, 2017: 1436-1437). The age-crime curve (Hirschi & Gottfredson, 1983: 576-578) presents data about the ages of which individuals are most likely to offend throughout their lives and can be used to help predict future offending or desistance from crime. A common pattern emerged when researching offending in relation to the age of the offenders. The age-crime curve shows a gradual increase in offending among individuals from the middle of their teenage years; this increase continues until around early adolescence. Offending amongst individuals older than this age group is considerably lower, shown by an abrupt decrease on the curve. Those who offend earliest in their lifetime and offend most frequently from a young age are expected to continue offending throughout their life or commit more serious offences in their adult years. For others, minor offending during young adolescence is typical behaviour and many individuals will desist from crime as they approach adulthood (DeLisi & Vaughn, 2008: 520).

Sykes and Matza (1957: 667-669) identified techniques of neutralisation, these are believed to be commonly used by offenders to justify their criminal behaviour. These techniques help offenders avoid their feelings of guilt and help them to convince others that their behaviour was acceptable. The first technique of neutralisation is the ‘denial of responsibility’, this technique is used when an offender acknowledges that the behaviour is deviant, but rejects their personal control over their actions. An offender may deny responsibility if their offence was a result of an accident or if they didn’t intend to cause harm. Another technique is ‘denial of injury’, when there is no victim or the victim was not harmed by the offence. For example, an offender may justify stealing another individual’s belongings by relying on the belief that the victim had insurance that would cover their losses. Another technique is ‘blaming the victim’, this way offenders don’t take accountability for their offence by suggesting the victim deserved harm or provoked them in some way. ‘Condemnation of the condemners’ is a technique used to project blame onto others, offenders acknowledge the wrongdoings of others to deflect attention or negative consequences upon someone else. Offenders may also ‘appeal to higher authorities’ to justify their behaviour by claiming to adhere to other loyalties instead of the social norms, which to them are more important (Ugelvik, 2012: 260).

Travis Hirschi’s (1969: 18) theory surrounding social bonds and offending highlights four main elements, Hirschi argued that these elements are important for discouraging young individuals from committing criminal activity. When an individual lacks one or more of the elements, their social bonds are likely to be weaker than others in society. Weak social bonds have been linked with low self-control which is associated with offending (Chriss, 2007: 57-60). The first of the elements is ‘attachment’, it is important for individuals to form healthy relationships throughout their lifetimes. Forming strong emotional connections with others allows individuals to learn the value of being responsive to other people’s feelings and interests. This element begins in childhood, it is deemed important for individuals to form healthy bonds with their parents to establish the thoughtfulness they need to avoid offending. The second element described by Hirschi is ‘commitment’, when individuals engage with standard behaviours which are accepted by society they are less likely to offend. These behaviours may involve investment of time and money which is an incentive to obey the laws of society. When individuals attend school or aim to sustain a job, they are committed to conforming to the norms of their environment. Deviating from social norms or breaking the law could jeopardise any investments they’ve made and weaken their bond with society. Another element that is believed to strengthen an individual’s bond with society is ‘involvement’, this is when individuals take part in ordinary, socially accepted activities which occupy their time. Activities can alleviate boredom and reduce the opportunities for offending that may be presented to an individual. Hirschi assumes that when individuals are occupied by activities, they are too busy to offend. Another element that can predict young offending is ‘belief’, this is described as the extent to which people believe they should conform to social norms and laws. If people feel disconnected from society they are less likely to understand the importance of conforming to the norms (Hirschi, 1969: 18-23).

Control theorists have often related offending with an offender’s relationship with their parental figures, this indicates that criminal tendencies may be established in their childhood. It is argued that absent parents overlook the importance of teaching their children self-control. If self-control is learned from a young age, it can be maintained throughout an individual’s life. Low self-control has been linked with impulsivity in young people and can help to explain problematic behaviour in a learning environment. Low self-control can also impact a young person’s relationships with their peers, they may find making friends to be difficult. Parents can help their children develop self-control by spending quality time engaging in activities with their child, treating them with affection and setting appropriate restrictions within their household (Beaver et al, 2007: 1346-1350). Certain parenting styles demonstrated by parents have been linked with delinquency, this includes methods of discipline and closeness with the child. Parents who opt for strict and harsh parenting strategies risk affecting their child’s behaviour later in life. Harsh parenting may be overbearing for some young individuals, especially when both the child and parents are confined in the home. When parenting is inconsistent, young individuals may become emotionally volatile and lack a personal identity which can be a risk factor of delinquency. Children require attention and affection from their parents for healthy development. Uninvolved parents can make their children feel unwanted which can lead to psychological problems later in life. Children who feel unwanted are likely to misbehave and develop mental health issues and this can be linked to delinquency. During the COVID-19 pandemic, It may have proven difficult for parents to balance their work-life and attending to their child during extended periods of isolation and stress. The effects of conflict within the family home may drive young individuals to offending, “broken families” are likely to be affected more by this phenomenon (Spohn & Kurtz, 2011: 333). Many parents of young children have been expected to home-school their children throughout the periods of school closure. Parents have reported feeling overwhelmed by the amount of work they are having to put into home-schooling and fear the quality of the education they provide for their children is not as good as they would receive at school. Home-schooling may change the dynamic within some households and possibly cause tension between parents and children. Parents were expected to assume the roles of both teacher and parent for their child. Parents need to balance the roles of teacher and parent, young people may find it difficult to differentiate between the two. The changes to education following the COVID-19 outbreak can have negative impacts on the mental health of young people and can affect the relationships between young people and their parents (Ferguson, 2021).

The secondary impacts of COVID-19 can have negative impacts on romantic relationships, young people may be affected by this if their parents are unable to adapt to the pressures of financial insecurity, prolonged confinement or mental health issues. Young people may also be romantically involved with someone, they may experience these effects on their own relationships. Some couples had found that spending too much time with their partner had damaging effects on their relationship. The vulnerability-stress-adaptation model (Karney & Bradbury, 1995) describes how couples are likely to respond to crisis and what impacts their responses can have on their relationships. Additional stress for parents may stem from the closure of schools because they are responsible for their children more often than usual. The model considers the importance of quality time and support within relationships despite the pressures put on the relationship by the crisis (Pietromonaco & Overall, 2020).

An element of desistance includes social bonds with family, peers and romantic partners. Social bonds allow individuals to feel accepted and unified with others and can encourage them to desist from crime. Groups of friends can influence the behaviour and beliefs of one another, which can have positive or negative effects on their behaviour and decisions. When surrounded by deviant friends, individuals may be influenced to mimic their behaviour, which can lead to offending. It is important for individuals to have friends who can provide support and encouragement, this can inspire them to achieve their goals and desist from deviance. Peers can provide individuals with resources and opportunities to succeed. (Weaver & McNeill, 2015: 98-102). As referred to in chapter one, the government restrictions regarding COVID-19 have limited people’s opportunities to interact with their friendship groups in a face-to-face setting. The lack of interaction with peers removes a possible element of desistance from their lives, which could make crime more appealing. Research suggests that education can be an important contributor to desistance from crime. Higher education can provide potential offenders with aspirations for the future and means of achieving their personal goals. Higher education can help young people identify and achieve their desired job roles beyond their education, these jobs can also act as elements of desistance (Hughes, 2021: 4). Many young people were unable to attend their universities or colleges over the course of the year 2020, most teaching was moved online to limit face-to-face interactions. Existing stressors for students surrounding exams and assignments were amplified by limited teaching and isolation. Many university students affected by the pandemic have reported the lack of support and social interaction to have had detrimental effects on their mental health (Blackall & Mistlin).

There are several factors discussed in this chapter that can be expected to weaken an individual’s bond with society. Control theories can help to predict problematic behaviour of an individual based on their surroundings and relationships. Control theorists aim to understand the thought processes of offenders and the explanations that they may use to justify their behaviour. COVID-19 has impacted family relationships, friendships and romantic relationships, and the negative effects on these relationships can be risk factors of offending in the future. Young people may have experienced the breakdown of their relationships for various reasons following the introduction of government restrictions. For many, relationships can help individuals desist from crime, so when individuals lack these social bonds, their likelihood of offending increases.

5. Right realism

The right realism approach for explaining criminality focuses on offenders being solely responsible for the crimes they commit. Theories surrounding this approach are often based on the assumption that criminality is most common amongst lower-class individuals and these individuals are in full control of their actions. Theorists often ignore any social or economic issues faced by the lower-class communities and would argue that their circumstances are not the cause of their criminality. Right realism emphasises the impacts of crime on society and who is affected most by measures put in place to reduce or respond to crime. James Q Wilson and George Kelling (1982) focused their research on the correlation between crime and urban decline and argued that when an area is visibly damaged or run down, criminal activity is likely to increase (Matthews, 1987: 373-374).

Broken windows theory (Kelling & Wilson, 1982: 29-31) explores the idea that when individuals encounter buildings or areas that are broken down, they may be drawn to commit more damage to the property. They may assume that nobody cares enough to repair the damage, and therefore can degrade the property further without facing repercussion. Any further damage to the property will go unnoticed or will not be cared about because the area is already in a broken down state. The example widely used to explain this theory is broken windows, if an individual notices a broken window they may see no harm in continuing the destruction of the window because the window is already broken. In this case, the process of damaging the window has already begun and when there is nobody willing to repair or clear away the damage, an individual may see no harm in damaging the window more. When this theory is applied to crime, it can explain why crime rates are significantly higher in areas with falling standards of appearance. The lack of order and cleanliness in certain areas may suggest that the community does not care about the image, which can promote criminality. The presence of visible criminal activity such as littering, vandalism, drinking alcohol in the streets and prostitution can change people’s perception of crime, individuals may develop more fear of crime when exposed to visible signs of criminal activity. Maintaining the appearance of an area and increasing the community’s shared pride for their neighbourhood are steps to reduce criminality in these areas (Ren et al, 2019).

Routine activities theory (Cohen & Felson, 1979: 589) considers three variables that must be present in order for a crime to occur. The theory assumes that most individuals would offend if all three variables applied to their circumstances. Firstly, an individual must be a motivated offender, they may be motivated by their personal circumstances, for instance, if they have financial concerns. Another variable is a suitable target, the offender must perceive the opportunity for offending to be low-risk. Measures such as security cameras, lighting and police presence can reduce the suitability of a target. A suitable target may be an expensive object made accessible to offenders, a weak victim or a house without security measures in place. Another factor to determine whether offending will occur is whether a capable guardian is present at the scene. The presence of a capable guardian such as a police officer presents more risk to the offender and can deter individuals from offending (Eck, 1995: 784-785).

In the UK, several national lockdowns followed the outbreak of COVID-19 which heavily disrupted the routine activities of most people. Businesses closed so many individuals were unable to work or had to work from home (Hodgkinson & Andresen, 2020: 2). These changes meant individuals spent prolonged amounts of time in their houses and some were advised not to leave their houses at all. Those who contracted symptoms of COVID-19 were obligated to remain in their households for a self-isolation period (Mikolai et al, 2020: 1-2). During the lockdowns, when individuals were advised to remain in their households, there were noticeable reductions in offences such as robbery, shoplifting, theft and battery. Homeowners became guardians of their property as they worked from home, making their houses less suitable targets for offenders. The closure of non-essential shops made shoplifting less frequent, a motivated offender may be willing to steal items from an open shop, but their target hardens when the shop is closed. Stealing from a closed business may require causing damage for example breaking a window. Burglary on the other hand is a more accessible offence when businesses are closed and business owners are encouraged to stay at home. The business owners were unable to act as guardians of their businesses during the national lockdowns, this could have made their business more vulnerable to burglary (Felson et al, 2020: 2).

A theory that demonstrates the right realist perspective of crime is rational choice theory, a theory based on the assumption that offenders are responsible for their actions and make conscious or unconscious decisions to offend. The rational choice explanation of crime assumes that every individual has the capacity to commit crimes but only those who choose to will offend. Individuals are presented with perceived risks and rewards when deciding whether to perform certain behaviours. Rewards can encourage the individual to act a certain way while risks can deter them. For example, when deciding whether to commit crimes or to conform to the law, offenders may be driven by financial gain of the crime or they may be seeking gratification from criminal activity. Risks may include the fear of getting caught and the potential punishments for their offending behaviour or even disapproval from their social group. In order for an individual to offend, they must weigh up the risks and rewards that are significant to them. If they perceive the rewards to benefit them more than the risks would hinder them, the offender is more inclined to commit the offence. In some cases, an individual is deterred from committing an offence because the reward is not worth the risk. If an offender has weighed up the possible positive and negative outcomes of their actions and had control over their behaviour, they should be held accountable for any criminal damage or harm to others (Cornish & Clarke, 2017).

When right realism is the main perspective influencing governmental policies, there is a common theme of being hard on crime. Punitive responses and crime prevention methods often reflect the idea that all offenders decide to commit crimes. Politicians can use the fear of crime held by the public to engage them with arguments surrounding offending. Those who fear crime may support politicians who pledge to remove offenders and make the country safer by trying to reduce crime. Punitive measures implemented in order to be tougher on crime have been criticized for being reactive to crime rather than preventing offending altogether. When seeking appropriate crime prevention measures, a popular approach is to reduce the available opportunities for committing offences, these measures are often centred around routine activities theory (Evans, 2011: 72-80).

Right realism influenced new approaches to crime prevention, such as situational crime prevention. This is a strategy to reduce crime by removing the opportunity for criminal activity and essentially making it more difficult for offenders to commit criminal acts. An example of this is target hardening which includes developing and implementing more advanced security measures to create more risks for the offender to consider. Introducing CCTV cameras around a building or adding window locks can make breaking into the property more difficult for the offender which may deter them. Another approach to situational crime prevention is ‘designing out crime’ which involves altering the physical environment where a certain crime is commonly committed. An example of this is creating concrete spikes under bridges to prevent homeless individuals from sleeping there, this is more an attempt to protect the image of an area. However this approach to crime prevention has been criticised, as rather than preventing crime completely, the opportunities for offending are displaced to other locations. While security cameras can protect certain properties from crime, those without the more advanced security become more vulnerable to victimisation. The approach may not prevent crime altogether, just prevent crime in a certain area (Haywards, 2007).

The government publicly announced guidelines that were introduced to slow down the spread of COVID-19. To prove the importance of the guidance and demonstrate the consequences of breaching the guidelines, the government warned the public that the COVID-19 regulations were being enforced by the police. The police were able to distribute fines to those who chose to break the new rules set by the government. The initial penalty for breaking the government guidelines was a fine between £50 and £100, different groups of people had different reactions to this fine. For some this fine was a small price to pay for the rewards they would receive, the risk is low. For many, the COVID-19 restrictions had heavily impacted their perceived freedoms, some of which people felt entitled to. Others saw the risk as low because the rules were not often enforced by the police so the chances of receiving the fine were low. In August of 2020 greater fines were introduced to be enforced as a consequence of breaching the government’s restrictions. For example fines of £10,000 were given to individuals who held large gatherings of people. These larger fines posed a higher risk than the previous measures to prevent breaking the rules. The changes in penalty for breaching the rules increased the risk significantly, so in comparison, the rewards were less worthwhile (The Week Staff, 2021).

Loïc Wacquant (2009: 1-38) studied the governmental response to crime and the working-class, finding that working-class groups are marginalised and targeted for punishment. Wacquant drew connections between crime rates and job insecurity amongst lower-class groups. The government has often used repressive measures to manage lower-class individuals with unstable employment. The government prioritised the discipline of the working class over supporting their financial and employment needs (Waquant, 2009). The state encourages the enforcement of strict crime control measures which aim to reassure the public concerns about safety. In previous decades, when unemployment was widespread amongst lower-class youths, there were significant increases in crime. Young people committed around 30% of the crimes in 2010, a time when unemployment was high for this group. Around 50% of violent offences were committed by young individuals at that time. The government response further marginalised working-class groups and resulted in a larger portion of young people entering the criminal justice system (Squires & Lea, 2012: 76-77). Wacquant identified zero-tolerance policing as a right realist crime control ideal, it involves punishing an individual for violating a law or rule, regardless of the extent of the breach or the severity of the punishment. Zero-tolerance policing sets an example to the public and demonstrates that even minor breaches of the law will be punished, making it less appealing to offend. This method, however, may not reflect which groups or areas have more criminality, but where repressive measures are most present. There may be more law enforcement officers and crime control measures deployed to lower-class areas, increasing the amount of crime recorded in these areas (Jones & Newburn, 2007: 221-222).

The right realist approach can reflect how the government’s response to COVID-19 has affected different groups throughout society. Lower-class individuals may have to follow the government restrictions more carefully to avoid receiving a fine. The implications of receiving a fine for a lower-class individual can be worse than for those with financial stability, this group is likely to be limited by their financial income. Based on this perspective, an increase in opportunity for crime may predict an increase in offending amongst young people.

6. Conclusion

The existing criminological theories explored in this literature review can be used to predict future patterns of crime that could potentially follow the COVID-19 pandemic. There are many secondary impacts to consider when assessing changes in crime rates after the pandemic, for example, unemployment, mental health issues and the breakdown of relationships. The traditional theories of delinquency can help identify predictors and risk factors of offending amongst young people, these theories can help draw correlations between changes to society and young offending. Future research can then identify which of these risk factors could have been aggravated by the secondary impacts of the pandemic. The immediate impacts of placing the country in a national lockdown were reflected by large reductions in many types of crime. Individuals were separated from one another and restricted from accessing many “non-essential” establishments, this could explain significant decreases in crime. The decreases in crime may signify the limited interactions between households due to social distancing. There are many other factors that may have discouraged young people from offending, such as lack of opportunity. The restrictions on movement made committing crimes in public spaces, such as shoplifting, more difficult. Over the course of the year, risk factors of crime may have been aggravated for some groups, individuals have been isolated in their homes throughout a crisis, which affected many people socially and economically.

Research so far suggests that crime predictors such as unemployment amongst young people have reached high levels following the government instruction to close “non-essential” businesses. The relationship between unemployment due to COVID-19 and youth crime is not yet clear, as unemployment is not the only possible contributing factor towards offending. To better understand the implications of unemployment on young offending, researchers can investigate crime rates of those left unemployed during the pandemic when all government restrictions are lifted. The national lockdown introduced many factors that made measuring the effects of COVID-19 restrictions on youth offending difficult, for example, limited social interaction between individuals. Based on routine activities theory (Cohen & Felson, 1979: 589), as referred to in chapter four, one can assume that when society begins to function as normal, more interactions between individuals can provide more opportunities for individuals to offend. Despite government efforts to eliminate COVID-19 as quickly as possible in order to resume societal norms and routines, many secondary impacts of national lockdowns may have long-term effects. The lasting impacts of the pandemic on young people may later influence changes in offending behaviour. The effects of social disorganisation on society, which were discussed in chapter two, may take time to diminish as there are many aspects of everyday life that were affected by government restrictions. As discussed in chapter one, the government attempted to counteract some of the secondary impacts of the pandemic by introducing an apprenticeship scheme for unemployed young people and the national tutoring programme for disadvantaged school children. While the secondary impacts may be expected to increase certain criminal activity, these government interventions may influence future changes to crime rates in a different way. Increasing employment opportunities and providing better education for young people can help individuals desist from offending, and can provide them with better means of achieving their goals for later in their lives.

Different criminological theories can be used to explore how the secondary impacts of COVID-19 may influence trends of delinquency following the easing of government restrictions. When the virus is under control and society can begin restoring its structure, there will be a clearer idea about the oncoming trends regarding youth offending. Developing predictions of future trends of young offending can help guide the government and law enforcement officials to put in place appropriate crime prevention measures and provide support for young people where necessary. If there is an expectation of increases in certain crimes, more measures can be put in place to reduce the effects of the increases. Further research on the secondary impacts of COVID-19 and youth crime can confirm or challenge the ideas from traditional theories of delinquency and consider whether the theories remain relevant in contemporary society. In the early stages of data collection surrounding the impacts of COVID-19 on young people, personal accounts detailing the experiences of young people can help identify issues that have affected small groups of individuals. These accounts can provide insight into the types of issues that have been aggravated during the epidemic. Any commonalities found in these responses can be investigated further and used as starting points for future projects. The collection of more data may allow researchers to make generalisations about how young people were affected by the pandemic.

Abrams, D.S. (2021) COVID and crime: An early empirical look. Journal of public economics, 194(1), 104344.

Baron, S.W. (2011) Street Youths and the Proximate and Contingent Causes of Instrumental Crime: Untangling Anomie Theory. Justice quarterly , 28(3), 413-436.

Beaver, K.M., Wright, J.P. & Delisi, M. (2007) Self-Control as an Executive Function: Reformulating Gottfredson and Hirschi’s Parental Socialization Thesis. Criminal justice and behavior , 34(10), 1345-1361.

Besnard, P. (1988) The true nature of anomie. Sociological Theory , 6(1), 91-95.

Blackall, M. & Mistlin, A. (2021) ‘Broken and defeated’: UK university students on the impact of Covid rules. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2021/jan/11/broken-and-defeated-uk-university-students-on-the-impact-of-covid-rules [Accessed 22/04/2021].

Boobis, S. & Albanese, F. (2020) The impact of COVID-19 on people facing homelessness and service provision across Great Britain. Available online: https://www.crisis.org.uk/ending-homelessness/homelessness-knowledge-hub/services-and-interventions/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-people-facing-homelessness-and-service-provision-across-great-britain-2020/ [Accessed 22/01/2021].

Bradbury‐Jones, C. & Isham, L. (2020) The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID‐19 on domestic violence. Journal of clinical nursing, 29(13), 2047-2049.

Buchanan, I. (2018) Anomie. In Buchanan, I. (ed) Dictionary of critical theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2.

Chriss, J.J. (2007) The functions of the social bond. The Sociological Quarterly , 48(4), 689-712.

Cid, J. & Martí, J. (2017) Imprisonment, Social Support, and Desistance: A Theoretical Approach to Pathways of Desistance and Persistence for Imprisoned Men. International journal of offender therapy and comparative criminology , 61(13), 1433-1454.

Cohen, L.E. & Felson, M (1979) Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 588-608.

Cornish, D.B. & Clarke, R.V.G. (2017) The reasoning criminal: rational choice perspectives on offending . London: Routledge.

D, Ferguson. (2021) ‘I feel like I’m failing’: Parents’ stress rises over home schooling in Covid lockdown. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/jan/23/i-feel-like-im-failing-parents-stress-rises-over-home-schooling-in-covid-lockdown [Accessed 06/04/2021].

DeLisi, M. & Vaughn, M.G. (2008) The Gottfredson–Hirschi Critiques Revisited: Reconciling Self-Control Theory, Criminal Careers, and Career Criminals. International journal of offender therapy and comparative criminology , 52(5), 520-537.

Durkheim, E. (1952) Suicide, A study in sociology . London: Routledge.

Eck, J.E. (1995) Examining routine activity theory: A review of two books. Justice Quarterly, 12(4), 783-797.

Evans, K. (2011) Crime prevention: a critical introduction . London: SAGE.

Felson, M., Jiang, S. & Xu, Y. (2020) Routine activity effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on burglary in Detroit, March, 2020. Crime science , 9(1), 1-7.

GOV (2020) Employers encouraged to sign up for apprentice cash boost. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/employers-encouraged-to-sign-up-for-apprentice-cash-boost [Accessed 05/04/2021].

GOV (2020) Get help with technology during coronavirus (COVID-19). Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/get-help-with-technology-for-remote-education-during-coronavirus-covid-19 [Accessed 07/04/2021].

GOV (2020) How the National Tutoring Programme can help students. Available online:

https://dfemedia.blog.gov.uk/2020/12/08/how-the-national-tutoring-programme-can-help-students/ [Accessed 07/04/2021].

GOV (2020) Oral statement to Parliament: Face coverings to be mandatory in shops and supermarkets from 24 July. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/face-coverings-to-be-mandatory-in-shops-and-supermarkets-from-24-july#:~:text=Face%20coverings%20to%20be%20mandatory,from%2024%20July%20%2D%20GOV.UK [Accessed 05/01/2021].

Grierson, J. (2020) Suspects to avoid criminal charges in UK during Covid-19 crisis. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/law/2020/apr/14/suspects-to-avoid-criminal-charges-in-uk-during-covid-19-crisis [Accessed 11/01/2021].

Hayward, K. (2007) Situational Crime Prevention and its Discontents: Rational Choice Theory versus the ‘Culture of Now’. Social policy & administration , 41(3), 232-250.

Healy, D. (2017) The dynamics of desistance: Charting pathways through change [eBook]. London: Taylor & Francis.

Hill, A. (2020) Generation Z, and the Covid pandemic: ‘I have pressed pause on my life’. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/oct/20/generation-z-on-covid-i-was-living-in-a-family-but-feeling-really-alone-pandemic [Accessed 01/11/2020]

Hirschi, T. (1969) Causes of Delinquency . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hirschi, T. & Gottfredson, M. R. (1983) Age and the Explanation of Crime. American Journal of Sociology, 89(3), 552–84.

Hodgkinson, T. & Andresen, M.A. (2020) Show me a man or a woman alone and I’ll show you a saint: Changes in the frequency of criminal incidents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of criminal justice , 69(1), 2-13.

Hughes, N. (2021) Higher Education and Desistance From Crime. Irish journal of academic practice , 9(1), 1-29.

Jeffery, C.R. (1971) Crime prevention through environmental design . Beverly Hills: Sage publications.

Jones, T. & Newburn, T. (2007) Symbolizing crime control: Reflections on Zero Tolerance. Theoretical criminology , 11(2), 221-243.

Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin , 118(1), 3-34.

Kelling, G.L. & Wilson, J.Q. (1982) Broken windows. Atlantic monthly , 249(3), 29-38.

Keogh-Brown, M.R., Jensen, H.T., Edmunds, W.J. & Smith, R.D. (2020) The impact of Covid-19, associated behaviours and policies on the UK economy: A computable general equilibrium model. SSM-population health , 12(1), 100651.

Kantis, C., Kiernan, S. & Bardi, J.S. (2021) UPDATED: Timeline of the Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/updated-timeline-coronavirus [Accessed 13/04/2021].

Marsh, S. (2021) Closed doors and lives in limbo: young Britons face Covid jobs crisis. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/feb/04/closed-doors-lives-limbo-young-britons-face-covid-jobs-crisis [Accessed 04/02/2021].

Matthews, R. (1987) Taking realist criminology seriously. Contemporary Crises, 11(4), 371-401.

Merton, R. K. (1938) Social structure and anomie. American sociological review. 3(5), 672-682.

Mikolai, J., Keenan, K. & Kulu, H. (2020) Intersecting household-level health and socio-economic vulnerabilities and the COVID-19 crisis: An analysis from the UK. SSM-population health, 12(1), 100628.

Miller, J.M. & Blumstein, A. (2020) Crime, justice & the COVID-19 pandemic: toward a national research agenda. American journal of criminal justice , 45(4), 515-524.

Office for national statistics (2020) Coronavirus and crime in England and Wales: August 2020. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/coronavirusandcrimeinenglandandwales/august2020 [Accessed 27/01/2021].

Petretto, D.R., Masala, I. & Masala, C. (2020) School Closure and Children in the Outbreak of COVID-19. Clinical practice and epidemiology in mental health , 16(1), 189.

Pietromonaco, P.R. & Overall, N.C. (2020) Applying relationship science to evaluate how the COVID-19 pandemic may impact couples’ relationships. American Psychologist , 75(4).

Ren, L., Zhao, J. & He, N. (2019) Broken Windows Theory and Citizen Engagement in Crime Prevention. Justice quarterly , 36(1), 1-30.

Romania, V. (2020) Interactional anomie? Imaging social distance after COVID-19: a Goffmanian perspective. Sociologica , 14(1), 51-66.

Scottish government (2020) Coronavirus (COVID-19): impact on children, young people and families – evidence summary September 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/report-covid-19-children-young-people-families-september-2020-evidence-summary/ [Accessed 11/01/21].

Singh, J. & Singh, J. (2020) COVID-19 and its impact on society. Electronic Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities , 2(1), 168-172.