An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

A Case Study in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: An Innovative Neurofeedback-Based Approach

Associated data.

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

In research about attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) there is growing interest in evaluating cortical activation and using neurofeedback in interventions. This paper presents a case study using monopolar electroencephalogram recording (brain mapping known as MiniQ) for subsequent use in an intervention with neurofeedback for a 10-year-old girl presenting predominantly inattentive ADHD. A total of 75 training sessions were performed, and brain wave activity was assessed before and after the intervention. The results indicated post-treatment benefits in the beta wave (related to a higher level of concentration) and in the theta/beta ratio, but not in the theta wave (related to higher levels of drowsiness and distraction). These instruments may be beneficial in the evaluation and treatment of ADHD.

1. Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common childhood disorders, affecting between 5.9% and 7.2% of the infant and adolescent population. The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [ 1 ] describes ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by a persistent pattern of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity manifesting in children before the age of 12 years old more frequently and with greater severity than expected in children of equivalent ages. Depending on the predominant symptoms, three types of presentation may be identified: predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, predominantly inattentive, and combined. There are two theories that attempt to explain the neurophysiological nature and characteristics of ADHD. Mirsky posited a deficit in attention as the main focus in ADHD, such that the failure is found in processes of activation [ 2 ]. The other theory was proposed by Barkley, who attributed the problems of ADHD to a deficit in behavioral regulation, where processes associated with the frontal cortex fail [ 3 ].

The determination of ADHD symptoms, along with the underlying neuropsychology, as outlined by the theories above, have led in recent years to the incorporation of evaluation and intervention techniques that do not solely focus on the behavioral aspects of the disorder. More specifically, techniques such as electroencephalography in ADHD evaluation and neurofeedback in interventions may provide greater benefits in detection and treatment.

The present study analyzes a specific case of ADHD with predominantly inattentive presentation, covering monopolar electroencephalogram recording (brain mapping called MiniQ) and intervention via neurofeedback.

The study was approved by the relevant Ethics Committee of the Principality of Asturias (reference: PMP/ICH/135/95; code: TDAH-Oviedo), and all procedures complied with relevant laws and institutional guidelines.

1.1. Evaluation of ADHD

The current diagnostic criteria for ADHD can be found in the DSM-5 [ 1 ] and in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, eleventh revision, from the World Health Organization [ 4 ]. Various evaluation instruments are used to identify ADHD, from general assessments via broad scales such as the Wechsler scale, to more specific tests assessing execution (e.g., test of variables of attention, D2 attention test), symptoms (e.g., Conners scale, EDAH scale), and the evaluation of cortical activity (e.g., using quantitative electroencephalograms, qEEG).

One alternative to qEEG is monopolar EEG recording (fundamentally used in clinical practice), called MiniQ (software Biograph Infinity, ThoughtTech, Montreal, QC, Canada). The MiniQ is an instrument for evaluating brain waves from 12 cortical locations (international 10/20 system) [ 5 ]. This type of evaluation (monopolar EEG, MiniQ) lies somewhere between the traditional baseline (single-channel qEEG) and full brain mapping. The frequency ranges evaluated match the classics [ 6 , 7 ]: delta 1–4 Hz, theta 4–8 Hz, alpha 8–12 Hz, sensorimotor rhythm SMR 12–15 Hz, beta 13–21 Hz, beta3 or high beta 20–32 Hz, and gamma 38–42 Hz. Theta waves have been related to low activation, sleep states, and low levels of awareness, beta and alpha waves have been associated with higher levels of attention and concentration [ 8 ]. In addition, the MiniQ, in line with qEEG, provides the relationships or ratios of theta/alpha, theta/beta, SMR/theta and peak alpha. Previous research has established that the ratio between theta and beta waves is a better indicator of brain activity than each wave taken separately (see Rodríguez et al. [ 9 ]). Monastra et al. attempted to establish what values of the theta/beta ratio would be compatible with those seen in subjects with ADHD [ 7 ]. They indicated critical values (cutoff points) for ADHD in theta/beta absolute power ratio, using 1.5 standard deviations compared to the control groups and based on age, those cutoff points are: 4.36 (6–11 years old), 2.89 (12–15 years old), 2.24 (16–20 years old), and 1.92 (21–30 years old). Higher values than the cutoff points would indicate a profile that is compatible with a subject with ADHD.

The distribution of electrical brain activity must be analyzed considering each site and the expected frequency. A regulated subject is characterized by more rapid activity in the frontal regions (predominantly beta) which decreases toward the posterior (occipital) regions, where slower waves (theta and delta) are expected [ 10 , 11 ]. Slower brainwaves are expected to predominate in the right hemisphere compared to the left, in which faster waves predominate. More specifically, beta waves will predominate in the left hemisphere, alpha waves in the right hemisphere, and there will be similar levels of theta waves in both. In addition, during a task (e.g., reading or arithmetic) rapid (beta) waves are expected to increase.

In contrast, the electrical activity in a subject with predominantly inattentive ADHD is characterized by a predominance of theta waves (compared to beta) in the frontal regions, particularly on the left (F3). During tasks (e.g., reading or arithmetic), a subject with predominantly inattentive ADHD will exhibit increased slower (theta) waves, and there will be a slowdown in the frontal regions that hinders attentional quality, as suggested by researchers such as Clarke et al. [ 10 ] and more recently, Kerson et al. [ 12 ]. Studying the profile of cortical activation allows suitable intervention protocols to be established and tailored to each subject.

1.2. ADHD Intervention

Many studies have examined the efficacy of the various treatments and interventions aimed at improving symptoms associated with ADHD (inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity), such as medication, behavioral treatments, and neurofeedback (see Caye et al. [ 13 ]). Neurofeedback is a type of biofeedback which aims for the subject to be aware of their brain activity and to be able to regulate it via classical conditioning processes [ 14 , 15 ]. In neurofeedback training, a subject’s electrical brain activity is recorded via an electroencephalograph, and the signal is filtered and exported to a computer. Software then transforms and quantifies the brainwaves, presenting them in the form of a game with movement or sounds which give the subject feedback about their brain activity [ 16 ].

The use of neurofeedback in interventions for ADHD began in 1973, although the first study with positive results was published in 1976 [ 17 ]. Since then, various studies have reported benefits from using neurofeedback in infants, with improvements in behavior, attention, and impulsivity control (e.g., [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ]). A meta-analysis by Arns et al. [ 14 ] concluded that treatment of ADHD with neurofeedback could be considered “effective and specific”, with a large effect size for attention deficit and impulsivity and a moderate effect size for hyperactivity. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Van Doren et al. [ 21 ] found that neurofeedback demonstrated moderate benefits for attention and hyperactivity-impulsivity, which were maintained in subsequent follow-ups (between 2 and 12 months after the intervention). However, in a recent meta-analysis aimed at comparing the effects of methylphenidate and neurofeedback on the main symptoms of ADHD, Yan et al. [ 20 ] found methylphenidate to be better than neurofeedback, although the authors highlighted that the results were inconsistent between evaluators.

Neurofeedback training is normally done two or three times a week, and around 40 sessions are needed to see changes in symptomatology [ 13 ]. Although it is an expensive treatment that needs consistency and continuity, in the USA, around 10% of children and adolescents with ADHD have received neurofeedback [ 23 ]. The benefits of neurofeedback training may depend on the type of protocol used. The three most-commonly used protocols in subjects with ADHD are [ 14 ]: (1) theta/beta ratio; (2) sensorimotor rhythm, SMR; and (3) slow cortical potential. The most widely used of these three protocols is the theta/beta ratio, based on inhibition of theta and increasing beta, which usually improves SMR at the same time [ 13 ]. However, it is important to note that there is no recommended standard about the number, time or frequency of sessions, and there is no standard placement of NF screening when this type of protocol is administered [ 24 , 25 ]. In this context, the present study aims to provide a structure in which the neurofeedback intervention is adjusted based on the data provided by the previous assessment in a specific case.

The intervention protocol must be tailored to each individual case based on prior assessment, especially when using results from tests such as the MiniQ. In this context, the objective of the current study is to present the process of analyzing brainwaves in a case with ADHD (predominantly inattentive presentation) via the MiniQ test, the protocol for intervention using neurofeedback, and its efficacy. Although the alteration of brainwaves in specific areas in subjects with ADHD is well documented, and the efficacy of neurofeedback has been observed in various studies, the present study aims to provide a specific procedure for assessment and intervention. Researchers and professionals need specific protocols and procedures that allow them to determine what is effective for each individual case.

2. Methodology

2.1. description of the case.

This was a case study using monopolar electroencephalogram recording (brain mapping known as MiniQ) for subsequent use in an intervention with neurofeedback for a 10-year-old girl presenting predominantly inattentive ADHD.

2.1.1. Patient Identification

The subject was a 10-year-old girl in the fourth year of primary education. Her academic performance was poor, with the worst results in language, social sciences, and science. She found it difficult to go to school and was shy and reserved. She was the younger of two sisters, the older being an outstanding pupil. Her mother characterized her as a quiet girl who needed a lot of time to do any kind of task. In addition, during the study and academic tasks, she would often gaze into space, as if she were in her own world. Both her father and her mother evidenced concern for her school results, but also for her social relationships, as her self-absorption appeared in all contexts, making it hard for her to have conversations, pay attention to others, or follow the rules in games.

2.1.2. Reason for Consultation

The consultation was for poor academic performance, slowness doing tasks, and wandering attention from when she had started school, although that had increased in the previous year. Initially, the subject did not demonstrate any great willingness to attend the consultations, but over time, she demonstrated a participative attitude with good involvement in doing the tasks she was set.

2.1.3. History of the Problem

The subject’s school history was one of failure in the main school subjects. She had not had to repeat a school year, but her form tutors repeatedly raised this possibility with her parents. At the time of the study, there had been no clinical or educational psychology assessments. Previous diagnosis of ADHD was by her neuropediatrician one month before the assessment in the Psychology clinic consultation. From that point, guidelines were given for pharmacological treatment, which had not begun.

2.2. Proposed Evaluation and Intervention

2.2.1. evaluation: brainwave analysis with the miniq instrument.

An assessment was performed using a MiniQ (Monopolar, from Biograph Infinity). Assessment using the MiniQ is a two-step process (evaluation and interpretation) which is simple, relatively fast, and inexpensive.

The first step is to make the recording from the 12 cortical sites, which can be done with eyes closed or open, and either with or without tasks (reading or arithmetic). This gives information about the values of the different brainwaves at each site. To begin, electrodes are placed on the earlobes and two active electrodes in each of the sites indicated by the program. Before beginning the assessment for each site, the impedance level—the quality of the connection—for each of the electrodes must be checked, both on the ears and on the scalp, to avoid artefacts. When the impedance level is below 4, the recording process can begin. The subject is instructed to remain still and to look at the computer screen where there is an image of a landscape. They must keep their eyes open and keep silent. The program guides the application, which is based on the placement of electrodes in groups of two following the sequence: Cz–Fz, Cz–Pz, F3–F4, C3–C4, P3–P4, O1–O2, and T3–T4. For sites F3–F4, subjects are asked to read a story quietly and to do some simple arithmetic (e.g., 2 + 3, +5, +4, −1, +6, −3, etc.). Once recordings have been made at all of the sites, the program filters the data to remove artefacts. Finally, the recorded data is interpreted, and the values are analyzed, allowing the state of the subjects’ brainwaves to be determined. Applying the test takes approximately 60 min.

The second step is to analyze the collected data considering the site and the frequency ranges at each. The sites are labelled based on the four quadrants of the cortex: anterior, posterior, left hemisphere (odd numbers), and right hemisphere (even numbers). The instrument gives the results in two formats, an Excel spreadsheet and a PowerPoint. In addition to the measurements or wave values (delta, theta, alpha, sensorimotor rhythm SMR, beta, beta3, and gamma) at the sites noted above, the spreadsheet also includes the values for the ratios of theta/alpha, theta/beta, SMR/theta, and peak alpha. The PowerPoint presentation gives the same information, although over a background image of a brain, which allows scores to be seen at the relevant site (see Figure 1 ). With that information, it is possible to assess cerebral asymmetry, both anterior-posterior and right-left, according to each location.

Pre-treatment results from the MiniQ instrument. Note . T = theta; B = beta; T/B = theta/beta ratio. In subjects aged between 7 and 11 years old, values over 2.8 for the theta/beta ratio are compatible with a profile of ADHD.

The values of the theta/beta ratios are interpreted based on Monastra et al. (1999) [ 7 ], bearing in mind that in this case, the scores were relative power not absolute. Scores are indicative of ADHD when the values are over 2.5 for those up to 7 years old, over 2.8 for 7- to 11-year-olds, over 2.4 in adolescents, and over 1.8 in adults. Traditional ratios for ADHD indicators use absolute power values measured in peak volts (microvolts squared divided by the hertz value). Biograph for theta/beta ratio calculation uses relative power values (microvolts divided by the hertz value).

2.2.2. Intervention: Neurofeedback Protocols

The intervention was carried out using the Biograph Infiniti biofeedback software (Procomp2 from Thought Technology, Montreal, QC, Canada; https://thoughttechnology.com/ , accessed on 23 December 2021). Two protocols were used in the intervention process, an SMR protocol and a theta/beta protocol. The protocol and specific sites selected were based on the prior evaluation.

The SMR protocol used site Cz and was designed to work on three frequencies, theta, SMR, and beta3 [ 26 ]. The objective of this kind of protocol is to perform SMR (12–15 Hz) training to increase the production of this wave and inhibit the production of theta (4–7 Hz) and beta3 (20–32 Hz) activity. During the training sessions, the subject watches a videogame or a film on the screen. Following the neurofeedback dynamic, the game or the film progresses positively if the level of electrical activity increases and stops when the level of electrical activity falls. Reinforcement occurs when the value of theta and beta3 are below the set value and SMR is above a pre-determined threshold. The reinforcement consists of a sound and points awarded to the subject. The working thresholds are provided by the program automatically, although they can be modified manually by the therapist. The level of reinforcement is set by the therapist. Initially, it is set at 80%, and depending on how the subject masters the task, the reinforcement is reduced. The subject is not given explicit instructions about what they have to do; they are told “try to keep the animation on the screen moving”.

The theta/beta protocol works at site Fz. The aim of this protocol is to reduce the amplitude of theta waves and increase beta to work on concentration. The subject has to do tasks which consist of concentrating on a game that appears on the computer screen. The game presents a pink square (which represents the value of theta) and a blue square (representing the value of beta). The subject is told that the game involves trying to make the pink square as small as possible and the blue square as large as possible. The computer automatically generates the ranges over which the waves are worked, although they can be changed manually by the therapist. The desired working theta/beta ratio can also be set manually. The protocol begins with high ratios, close to three, such that the task is simple and the subject achieves reinforcement on many occasions. The ratio is progressively reduced according to the subject’s progress.

The intervention lasted for a year and consisted of 75 neurofeedback sessions. There were two phases to the training. The first phase, “the regulation phase”, covered the first 15 sessions, during which the SMR protocol was followed at Cz. The aim of this first phase was to strengthen SMR and inhibit theta and beta3 in the central region. These sessions were around 45 min each. To avoid tiredness, different presentations of neurofeedback were used (videogame or film) during the sessions, with five-minute breaks between each presentation.

The second phase ran from session 16 to session 75. In these sessions, the SMR protocol at Cz was applied for 20 min, followed by a five-minute break before the theta/beta protocol at Fz was applied for another 20 min. For the first six months of the intervention, sessions were 45 min, twice weekly. During the remaining six months, the sessions were weekly and remained 45 min long.

3.1. Brainwave Evaluation

Based on the information obtained over the evaluation of the case, and considering the prior diagnosis from her pediatric neurologist, the subject presented ADHD with predominantly inattentive presentation. As Figure 1 shows, her brainwave profile indicated scores for the theta/beta ratio of close to 2.8 in the central (Cz) and frontal regions (Fz). Considering the scores in Cz and Fz, the neurofeedback needed to include these sites. Furthermore, neurofeedback on frontal-midline theta (Fz) has been shown to be frequently more effective than neurofeedback protocols that do not include Fz [ 22 ].

Given the brainwave profile, the aim of the intervention was to reduce theta and increase beta in the frontal zones. That indicated using the SMR and theta/beta protocols [ 15 ].

3.2. Progression following Neurofeedback Intervention

Once the neurofeedback intervention was completed, brainwave activity was assessed again using the MiniQ. Figure 2 illustrates the change in theta, beta, and SMR, along with the theta/beta ratio at sites Cz and Fz. The results show a positive progression following the neurofeedback training.

Pre- and post-treatment activity in sites Cz and Fz.

Theta activity fell following the intervention, both at Fz (by 0.77) and at Cz (by 1.56). To put it another way, there was a reduction in the slow wave at both sites (mainly in the central region compared to the frontal region). This is in line with expected values of theta at the cortical level, as they should be higher in posterior areas and lower in frontal areas.

There was also an increase in beta at the two sites, with a 3.60-point increase at Fz and a 4.2-point increase at Cz. In this case, the intervention produced considerable increases in the rapid wave values at both sites, although the value was slightly higher in the central area than in the frontal. Values for beta waves are expected to be higher in frontal areas than central areas, and although that was not the case here, the values were very close. The SMR wave also increased notably, by 2.57 points at Fz and 2.89 points at Cz. In short, the intervention led to a slight reduction in the slow wave, with lower values at post-treatment (less distraction), and increases in fast waves, beta, and SMR, with higher values after the intervention (better ability to concentrate). The theta/beta ratio also decreased at post-treatment (basically due to the increase in beta), both at Fz (by 0.69) and Cz (by 0.96), from values close to those for ADHD to scores more indicative of a subject without ADHD.

In addition, as initially proposed, the assessment with the MiniQ also considered the subject’s activation levels during reading and arithmetic tasks. Measurement of these values was at sites F3 and F4. The subject did three types of task for two minutes each: Paying attention to the screen on which a landscape appeared, reading a story, and doing simple arithmetic (addition and subtraction). As Figure 3 shows, post-treatment scores were different than pre-treatment scores.

Pre- and post-treatment evolution in F3 and F4 areas with and without tasks.

In the first task (pay attention to the screen), the values for theta, beta, and beta3 at F3 and F4 all rose. In the second and third tasks (reading and arithmetic), there were variations in all of the waves, both slow and fast. These results indicate that there was no improvement during tasks following the intervention, because although the fast waves (beta and beta3) increased, the slow wave (theta) did not diminish. Following the intervention, the expectation was to have increased levels of beta and beta3 (especially at F3), while reducing levels of theta. However, as Figure 3 shows, the theta/beta ratio fell, with lower values post-treatment.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to present the process for detecting a case of ADHD (predominantly inattentive presentation) using the MiniQ test, along with the neurofeedback intervention protocol and its efficacy. In terms of detection, the MiniQ showed the subjects’ brain activity, which together with behavioral symptoms, provided details of their characteristic profile and allowed tailored treatment. Various studies in the literature have concluded that children with ADHD exhibit higher levels of theta waves and lower levels of beta waves, particularly in frontal areas [ 10 , 11 ]. In addition, the relationship between the theta and beta waves (the theta/beta ratio) had already been associated with ADHD symptomatology through the research by Monastra et al. [ 7 ] and Jarrett et al. [ 27 ].

In the current case study, the MiniQ was relatively simple to apply, and it provided large amounts of information related to brainwave values at the 12 different sites. More specifically, the EEG record of the 10-year-old subject showed lower levels of beta activity in the frontal regions and a higher level of theta activity in the frontal and central regions. However, the slow wave (theta) should be higher in posterior regions and fall in the central area, whereas the fast waves (beta and beta3) should be higher in the anterior regions and lower in the posterior. The subject’s theta/beta ratio was high (Cz: 2.05) and close to values seen in subjects with ADHD according to Monastra et al. [ 7 ]. and Jarrett et al. [ 27 ]. Although the theta/beta ratio was not high enough to clearly or exactly indicate the presence of ADHD with predominantly inattentive presentation, it is important to consider the full set of data provided by the MiniQ. It is also important to note that the diagnosis of ADHD was reported by the neuropediatrician, who usually uses behavioral criteria. At the same time, we cannot ignore the fact that the use of the theta/beta ratio has also been questioned by other works (e.g., [ 28 ]). In any case, the importance of the brainwave analysis lay in helping decide which intervention protocols to follow, along with the frequencies and the sites to use. The chosen neurofeedback protocols were the SMR protocol and the theta/beta protocol. There were 75 intervention sessions, 45 SMR at Cz and 30 theta/beta at Fz. Once the intervention was complete, the changes in theta, beta, beta3 and SMR waves were assessed using the MiniQ.

The intervention produced a variety of results. Firstly, there was a small reduction in theta activity and an increase in SMR, which would indicate better levels of attention. In addition, the theta/beta ratio fell to levels which were closer to those in subjects without ADHD. However, this improvement in the theta/beta ratio was due to increased beta rather than by the reduction of theta. Janssen et al. found similar results in 38 children with ADHD by analyzing the learning curve during 29 neurofeedback training sessions [ 29 ]. Their results indicated that while theta activity did not change over the course of the sessions, beta activity showed a linear increase during the study. In our study, the subject was able to significantly improve the levels of beta, but was hardly able to reduce theta activity, which is what would allow even greater improvements in attentional ability. Given this progress, the use of a protocol for inhibition of theta waves at Fz may be effective in strengthening the development of attention levels. Although there were no notable changes at other sites, such as F3 and F4, it is important to note that the intervention was carried out only at Cz and Fz.

On similar lines, during tasks after the intervention (reading and arithmetic), there was no reduction in theta but there was an increase in beta and beta3, again in line with the results from Janssen et al. [ 29 ]. For reading and arithmetic, one would expect, at least in subjects without ADHD, that in the frontal regions, values of slow waves would fall and fast waves would rise. However, in this study, there was no increase in beta waves in frontal regions during the tasks. This may indicate that although the neurofeedback intervention protocols in subjects with ADHD produce improvements in baseline activation (increased beta), the same does not happen with activation during the execution of tasks such as reading and arithmetic. In addition, Monastra et al. [ 7 ] showed that the activation profile of subjects with ADHD was similar with no task and during a reading task (unlike the control subjects, in whom activation increased during the reading task). Although this fact may be related to the ADHD profile, in our case study, with 75 neurofeedback sessions, we found no differences in the activation of frontal areas during a specific task, such as reading or mathematics.

As Enriquez-Geppert et al. [ 24 ] and Duric et al. [ 25 ] state, it is still necessary to develop specific procedures (which consider electrode placement and the specific theta/beta, SMR or slow cortical potential protocol) for intervention tailored to the different cases that professionals may find in clinical practice, in order to achieve better results. In this regard, it would be interesting to study theta/beta-ratio learning curves during intervention with neurofeedback, with the aim of achieving better results and making this tool as adaptive as possible in the future.

5. Conclusions

These results point toward the hypothesis that the low baseline cortical activation seen in subjects with ADHD would be found to be the basis of the disorder. While neurofeedback training may produce a positive progression, difficulties would persist, particularly during specific tasks in which subjects with ADHD are unable to achieve an ideal profile of brainwave activity for optimum performance. This is a reflection of the fact that the disorder persists throughout life, and hence, despite improvements in the cortical activation profile and the subject learning to strengthen their beta wave activity to concentrate, there will continue to be high levels of theta.

In this context, various studies such as Doppelmayr and Weber [ 30 ] and Vernon et al. [ 31 ] have reported the benefits of the SMR protocol and others, such as Arns et al. [ 13 ], Gevensleben et al. [ 32 ] and Leins et al. [ 33 ], have done the same with regard to the theta/beta protocol. However, other studies, such as Cortese et al. [ 34 ] and Logemann et al. [ 35 ], have not found improvements following neurofeedback intervention in children with ADHD. Considering these differences between previous studies, it would be interesting to establish the benefits of one or other of the protocols in interventions in children with ADHD. For example, in adults without ADHD symptoms, Doppelmayr and Weber [ 30 ] examined the efficacy of the theta/beta and SMR protocols. They found that the subjects who followed the SMR protocol were able to modulate their brain activity, whereas the theta/beta protocol did not provide benefits in regulation of brain activity.

It is also worth noting that, while previous studies employed similar protocols (SMR, theta/beta), the numbers of sessions and the session durations varied between studies. These variations may be related to the differences in the results and indicate the need to establish intervention protocols not only about what to work with (brain waves) but also how to do it (e.g., number of sessions, session duration, break schedules, etc.). At the same time, the present study underscores the need to tailor protocols to subjects’ profiles, along the same lines as previous studies, for instance Cueli et al. [ 16 ], who noted differences in the benefits of interventions based on the type of ADHD presentation. As authors such as Leins et al. [ 33 ] have indicated, most neurofeedback intervention programs combine two protocols, and it would be interesting to determine whether the combination is more effective than applying a single protocol.

In the future, it would be advisable to assess subjects’ levels of activation every 10 to 15 sessions of neurofeedback training in order to tailor the protocols to their progress and to study the theta/beta ratio learning curve as mentioned above. One limitation it is important to note is that multidomain assessments before, during, and after treatment (and adequate follow-up) should include blinding and sham inertness Another limitation of the present study is the lack of a behavioral assessment that would allow for an in-depth analysis of the subject’s progress in line with the protocol from Holtmann et al. [ 36 ]. At the same time, in spite of the limitations associated with case studies, such as not being able to produce generalizable results, the present work aims to be of some use to clinical and educational professionals so that they may consider intervention protocols for cases similar to the one described here.

Finally, despite the limitations described above, it would also be useful to consider the possibility of incorporating this type of training in more cases of subjects with ADHD, because neurofeedback intervention may offer long-term benefits in terms of improving the attentional abilities of subjects with ADHD, especially if one considers that approximately a third of ADHD patients do not respond to, or sufficiently tolerate, pharmacological treatment [ 37 ]. In this regard, it would be interesting to analyze the efficacy of new potential tools that combine neurofeedback and virtual reality and incorporate them into clinical practice [ 38 ].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C. and M.C.; methodology, all authors; formal analysis, M.C. and P.G.-C.; data curation, L.M.C. and P.G.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C., M.C., and L.M.C.; writing—review and editing, P.G.-C.; visualization, P.C.; supervision M.C. and P.G.-C.; project administration, P.C. and P.G.-C.; funding acquisition, P.G.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This study was made possible thanks to financing from the Ministry of Sciences and Innovation I + D + i project with reference PGC2018-097739-B-I00; and a pre-doctoral grant from the Severo Ochoa Program with reference BP19-022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, because the study did not involve biological human experiment and patient data. The study was approved by the relevant Ethics Committee of the Principality of Asturias (reference: PMP/ICH/135/95; code: TDAH-Oviedo), and all procedures complied with relevant laws and institutional guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the family involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Presidential Message

- Nominations/Elections

- Past Presidents

- Member Spotlight

- Fellow List

- Fellowship Nominations

- Current Awardees

- Award Nominations

- SCP Mentoring Program

- SCP Book Club

- Pub Fee & Certificate Purchases

- LEAD Program

- Introduction

- Find a Treatment

- Submit Proposal

- Dissemination and Implementation

- Diversity Resources

- Graduate School Applicants

- Student Resources

- Early Career Resources

- Principles for Training in Evidence-Based Psychology

- Advances in Psychotherapy

- Announcements

- Submit Blog

- Student Blog

- The Clinical Psychologist

- CP:SP Journal

- APA Convention

- SCP Conference

CASE STUDY Jen (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder)

Case study details.

Jen is a 29 year-old woman who presents to your clinic in distress. In the interview she fidgets and has a hard time sitting still. She opens up by telling you she is about to be fired from her job. In addition, she tearfully tells you that she is in a major fight with her husband of 1 year because he is ready to have children but she fears that she is “too disorganized to be a good mother.” As you break down some of the processes that have led to her current crises, you learn that she has a hard time with time management and tends to be disorganized. She chronically misplaces everyday objects like her keys and runs late to appointments. Although she wants her work to be perfect, she is prone to making careless mistakes. The struggle for perfection makes starting a new task feel very stressful, leading her to procrastinate starting in the first place. As a consequence, she has recently received a number of warnings from her boss related to missing deadlines for assignments and errors in her work, which has led to her acute fear of being fired. As her performance at work has plummeted and she has grown increasingly anxious and doubting of herself, she has grown more pessimistic about starting a family. You learn that she received extra time for test taking in school as a child but never had any formal neuropsychological testing. With Jen’s permission, you conduct additional structured assessments, including collecting collateral information from her fiancé, and conclude that she has adult ADHD.

- Concentration Difficulties

- Impulsivity

Diagnoses and Related Treatments

1. attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (adults).

Thank you for supporting the Society of Clinical Psychology. To enhance our membership benefits, we are requesting that members fill out their profile in full. This will help the Division to gather appropriate data to provide you with the best benefits. You will be able to access all other areas of the website, once your profile is submitted. Thank you and please feel free to email the Central Office at [email protected] if you have any questions

Copyright © 2024 OccupationalTherapy.com - All Rights Reserved

Pediatric Case Study: Child with ADHD

Nicole quint, dr.ot, otr/l.

- Early Intervention and School-Based

To earn CEUs for this article, become a member.

unlimit ed ceu access | $129/year

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (adhd).

Hello everyone. Today, we are going to be talking about attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. I consider this to be under the umbrella of "invisible diagnoses." This population has a special place in my heart because it is very easy to misconstrue some of the challenges that they have as intentional and behavior-based, and therefore, sometimes they get a bad rap. Thus, I am always happy to help kids with ADHD.

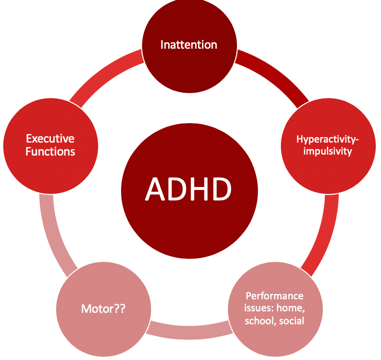

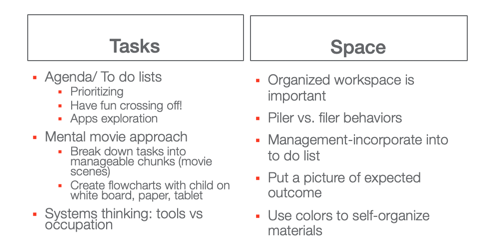

Figure 1. Overview of ADHD.

Individuals with ADHD have a lot of challenges that affect their occupational participation and performance. I think most of us are very comfortable with the idea that inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity are the hallmarks, but what sometimes can get lost is the idea that executive functions are very much affected by impulsivity. Motor issues are also often involved with kids with ADHD and are not always considered. In fact, there is a lot of evidence to support that the motor needs of these kids often go unaddressed. Typically, these kids come to us when parents or schools have major concerns about their behavior. Therefore, this tends to be where everyone focuses their attention. Oftentimes, the motor issues then fly under the radar and do not get addressed. The cool thing is that motor interventions can be the means to make some really significant changes for these kids, particularly in the area of executive function. There is a win-win situation when we address the motor issues. Lastly, they tend to also have performance issues not only in their home environment but also in their school and social environments as well.

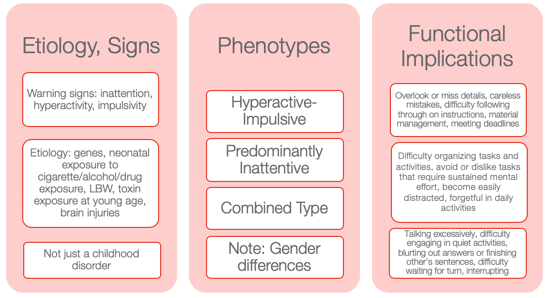

Figure 2. Other information from the NIMH Information Resource Center (2020).

I wanted to provide some information to help you to appreciate how diverse ADHD is. Many might still use ADD when we are talking about the children who have an inattentive type as it seems to make more sense. However, that is not how it is defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5).

Etiology and Signs

The etiology and the signs are inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. We also know there is a genetic predisposition to this. Neonatal exposure to cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs can also lead to ADHD. Low birth weight and toxin exposure are some of the environmental elements. ADHD can also be the result of a brain injury. This is not just a childhood disorder, and people do not grow out of it. In fact, the symptoms can actually get worse as life gets harder as one gets older. Adults who have ADHD can have some significant struggles, particularly if they do not know that they have ADHD or if it was never addressed.

There are three phenotypes: hyperactive-impulsive type, predominantly inattentive type, and a combination type. I think the hyperactive-impulsive type is the picture most people have when they think of ADHD. Then, we have the predominantly inattentive type. These are the daydreamers or the individuals that jump from one thought to the next. They have a really hard time staying focused for long. Lastly, there is the combined type. This is where we see both elements of inattention and hyperactivity and/or impulsivity. I think it is really important to also appreciate gender differences. You can see very different types of ADHD in girls versus boys. Boys obviously tend to be of the hyperactive-impulsive type, but even the inattentive type can be a little different. Girls, who have ADHD, tend to be talkative and a little more anxious. They definitely have a different predisposition as opposed to the boys. Thus, it might be the same diagnosis but look very different between the genders.

Functional Implications

Functional implications become extremely important. These are individuals who tend to overlook or miss details. They might make careless mistakes. They have difficulty following through with directions at school. Material management can become very challenging especially dealing with paperwork. They can miss deadlines and have a hard time keeping track of and prioritizing tasks. These are some of the higher-level executive functions. You might also see an avoidance or an expressed dislike of tasks that require a significant amount of sustained mental effort. They might tell you it is too hard, and they might feel very overwhelmed. They become very easily distracted by anything. The use of electronics adds to the issue. They can be forgetful in daily activities, talk excessively, have difficulty engaging in quiet activities, and tend to blurt out answers or finish others' sentences. Often, the perception is they are interrupting and being rude. They may have difficulty waiting for their turn or interrupt during someone else's turn. These are examples of impulsive behaviors. We will talk more about this when we get to executive functions.

Differential Diagnosis Between ADHD and SPD

- A high rate of comorbidity between SMD and ADHD

- ADHD and SMD

- Both at risk for limited participation in many aspects of daily life

- ADHD slightly worse attention scores than SMD

- Tactile, taste/smell, and movement sensitivity, visual-auditory sensitivity; behavioral manifestations of sensory systems

- Exaggerated electrodermal responses to sensory stimulation, thus increased risk of sympathetic “fight or flight” reactions

(Miller et al., 2012; Yochman et al., 2013)

Sometimes, kids who have ADHD also have some sensory issues. You may wonder, "Do they have just ADHD by itself?" This is probably one of the most common questions I get when working with kids with ADHD whether it is from teachers, other therapists, or from parents. Next, we are going to be talking about a child who has straight ADHD. However, for a few minutes, I want to talk about the whole idea of differential diagnosis between ADHD and SPD and how this all fits together. There is a very high comorbidity between sensory modulation disorder and ADHD. When I am referring to sensory modulation disorder, I am using the Lucy Jane Miller nosology. Sensory modulation disorder refers to the over-responsive, under-responsive, and/or craving of sensory input. For both ADHD and sensory modulation disorder, you will see that these diagnoses are both at risk for limited participation. These are kids who will not participate in certain activities because the sensory input is too much or overwhelming for them. ADHD will have slightly worse attention scores than SMD when you complete a formal attention test like the Test of Everyday Attention. However, you will see the same kind of impulsive behaviors.

Those with sensory modulation disorders tend to have difficulty with tactile, taste, smell, and movement sensitivities. You might also see some visual-auditory sensitivity so there are some behavioral manifestations that come of that. They might become stressed related to fears of vestibular or other movement input. They might also dislike certain noises or touch.

They found in the research that sensory modulation dysfunction, not ADHD , will have an exaggerated electrodermal response to sensory stimulation. This means that they have an increased risk of sympathetic activation which is the fight-or-flight, freeze/faint reactions, and meltdowns. When you have a child with meltdowns, you want to investigate if they have sensory modulation dysfunction right away. And, if you have a child with ADHD who does not have a history of meltdowns, that is a really good sign of your initial hypothesis. While this alone does not mean that they do not a sensory modulation dysfunction, chances are that they do not. Additionally, they might have dyspraxia or a discrimination disorder.

This is just a brief summary of how this all comes to play with an ADHD diagnosis and possible comorbidities.

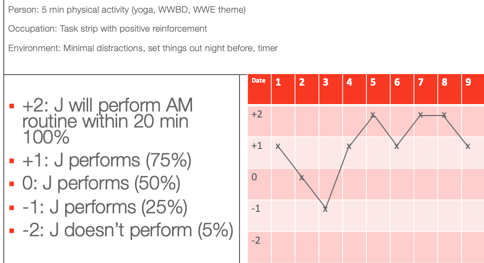

Case Introduction: Jeremy (Age 9, ADHD, Combined Type)

- He lives with his mother and older sister in SFH and goes to his father’s house on the weekend (divorced)

- He is in the 4th grade and has an IEP for OHI

- Strengths: funny, good at math, helps the family to take care of pets, watches WWE with father, loves dogs, likes to play board games (Monopoly, Sorry)

- School concerns: material management, organization, completing tasks or losing work , impulsive, social difficulties (short-lived relationships, fights), “lacks self-control” and “messy”, underperforming and sometimes seems “lost”

- Family concerns: Fights with a sibling, sleep difficulties, messy room, messy notebooks, and backpack, loses things, avoids homework, resists bedtime, difficult to wake in the morning and slow with routine , poor hygiene

- Jeremy’s goal: make friends, be able to find his schoolwork, have good friends, be better at kickball and wrestling

Jeremy is nine, and his diagnosis is ADHD, combined type. I have a feeling Jeremy is probably similar to a lot of the kids you see. I know I have seen a lot of these types of kids. He lives with his mother and older sister in a single-family home and goes to his father's house on the weekend because of a divorce. He is in the fourth grade, is eligible for an IEP because of an OHI (other health impairment), and is eligible for special education services because of his diagnosis of ADHD.

I always like to start with strengths with all kids, especially ADHD because these kids can have a really hard time with confidence and self-esteem. They also get blamed for their behaviors. For his strengths, he is funny, good at math, and he likes to help take care of his pets at home. He likes to watch wrestling, World Wrestling Federation (WWF) with his father, loves dogs, and loves to play board games. He is really good at Monopoly and Sorry.

At school, he had challenges with material management, organization, completing tasks, and not losing work. These last two are highlighted as we are going to focus on that. He is impulsive, and he has social difficulties. His teacher described his relationships as short-lived. He would have a friend, and then all of a sudden, they were not friends anymore. She also reported that he lacked self-control, was messy, and thought he underperformed. And, she felt like he always seemed lost. When they were going through the instructions or going through something, he was always looking at his peer's work or looking confused while he was trying to figure out what was going on.

The family had some concerns about his fighting with a sibling, significant sleep difficulties, a messy room, messy notebooks and backpack, and that he would often lose things. He also avoided his homework and resisted bedtime. As a result, it was very difficult to wake him up in the morning, and he was slow with his AM routine. His mom said that he also had an impulsive way of performing hygiene tasks. For example, he would brush his teeth in two seconds and say he was done. Everything was quick and impulsive. This is very typical for boys with this type of ADHD.

His goals were to make friends and find his school work. He said it was very stressful to always feel like he was losing his school work. He was motivated to do well in school. He did not just want to make friends, but he wanted to have good friends. He also wanted to be better at kickball because that is what the kids played at recess and in PE. He also wanted to be better at wrestling as not only did he like to watch with his dad, but he also liked to wrestle with him.

I want to go back to the highlighted areas in my list: completing tasks, losing work, and difficulty waking in the morning. These are the areas we are going to focus on.

Assessments

Assessments are one of the most challenging things for people because they are often under a time crunch, and the reports are difficult to write up and are time-consuming. However, it is really important with these kids as it gives us a full perspective on where they are having challenges. Knowing that he has "ADHD combined type" does not really tell us about his occupational performance and participation. We want to really get all that information. I like to be pretty thorough, and I will scatter assessments throughout my time with them to try to get a good idea. Again, I really like to check out their motor skills. I have kids that are superstars in sports, but I will still find out that there are some motor problems.

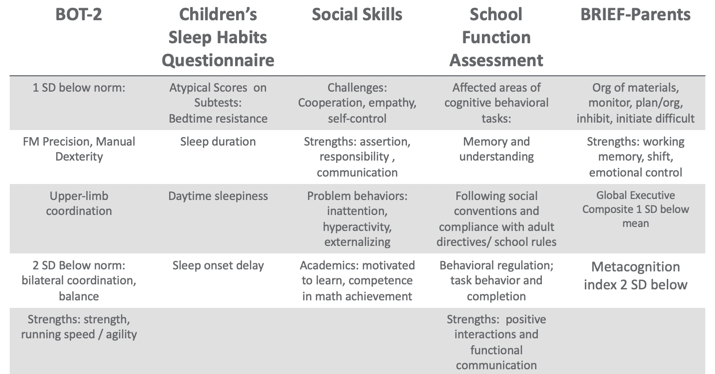

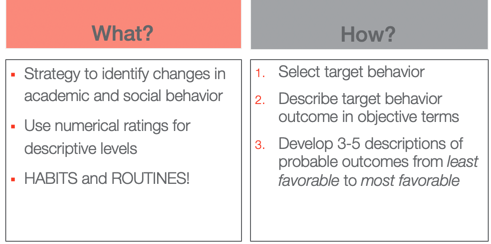

Typically, the motor challenges with ADHD have to do with bilateral coordination, dexterity, and those kinds of things. They might be good at some things, like basketball or baseball, but this does not mean that they are good at fine manipulation. Thus, it is really important to find out where they are. Figure 3 shows a summary of the assessments I did with Jeremy.

Figure 3. Assessment results.

Using the BOT, I found that Jeremy was one standard deviation below the norm in fine motor, precision, and manual dexterity, which was not surprising. He was two standard deviations below the norm in bilateral coordination and balance. However, his overall strength, running speed, and agility were fine.

There are many great tools out there for sleep including free ones. One of my favorites is the Sleep Habits Questionnaire. It is free online. It is great because it uncovers behaviors regarding going to bed, sleep duration, daytime sleepiness, and sleep onset delay. Many kids with ADHD have an overactive thinking process which then causes a sleep latency problem. It is hard for them to settle their brain and get to sleep. They also might have difficulty with sleep duration and not get enough sleep or good quality of sleep. If their arousal level is still high at night, it' is hard to get them to calm down and want to go to bed, especially if they are very disorganized in their thinking. This questionnaire gives you good information. Our results with Jeremy found that had bedtime resistance, sleep duration, daytime sleepiness, and sleep onset delays that were all atypical scores.

I also did a social skills assessment with him because his goal was to make friends, and school indicated that he had a hard time with solid friendships. I like to have a social-emotional learning perspective, and the more I know about a child's emotional intelligence, the better. We want these kids to be successful in their social interactions because that affects their whole life. With the Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS) Rating Scales, I found challenges with cooperation, empathy, and self-control. His strengths included assertion, responsibility, and communication. Under "problem behaviors", I found inattention, hyperactivity, and some externalizing behaviors. With his diagnosis, this all seems to fit. For academics, he was motivated to learn and had competence in math achievement. We already knew he had strengths in math.

I also did the School Function Assessment. I love this tool. There is one section that is a little dated as it talks about a floppy disk or something, but the other information on there is fantastic. This is especially true if you have kids who have a hard time following rules, social conventions, and material management. You can give it to the teacher, and they can score that. I found that Jeremy had some affected areas with memory and understanding, following social conventions, and compliance with adult directives and school rules. Additionally, he had some behavioral regulation issues, and task behavior and completion were difficult for him. His strengths included positive interactions and functional communication. Communication is strong for him,= which is a good thing.

The BRIEF (Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function) is an executive function tool that I did that with his parents. What we found was that the organization of materials, monitoring, planning and organization, inhibition, and initiation were difficult for him. His strengths were his working memory. Additionally, cognitive shifting and emotional control were also strong. However, his global executive composite was one standard deviation below the mean which means that he was low in everything. While it was not devastatingly low, he was below the average in everything. He struggled the most in metacognition, and that was two standard deviations below the norm. Thinking about his own thinking was a struggle for him.

From an observation standpoint, I also got a video from him mom of his AM routine so I could see what that looked like. He was in slow motion, very tired, not wanting to do the routine, and his performance was of low quality, I would put it, writing examples from school, because sometimes you'll see that the handwriting is indicative kind of the brain and the body not matching up, the brain going a little faster than the body. And so I also had a homework video watching him kind of resist homework. And then I did ocular motor testing, checked his tracking, convergence, divergence, and saccades and those kinds of things. Because there is a correlation between having some difficulties with that sometimes. But he actually was fine, and that wasn't a complaint from parents. So I just wanted to make sure it wasn't an issue that we were missing. So that gave me a lot of information.

Research Implications: Assessment

This is information about some of the research implications regarding the assessment process and kind of why I chose the tools that I chose and why I recommend a comprehensive one.

- Motor: Children with parent-reported motor issues received more PT than those with teacher-reported motor issues (risk)/undertreated motor problems in children with ADHD (due to behavioral factors in referral); HW difficulties; higher ADHD and lower motor proficiency scores reported more sleep problems (Papadopoulos et al., 2018)

- Sleep: Sleep deficits negatively affect inhibitory control (Cremone-Caira et al., 2019); Difficulties initiating and maintaining sleep 25-50% in ADHD (Corkum et al., 1998); Prevalence of sleep disorders 84.8 % affecting QoL (Yurumez & Gunay Kilic, 2013)

- EF: Motor skills and EF related (Pan et al., 2015); boys with ADHD have lower EF abilities than typical peers on both performance-based and parent report tools, thus combo is recommended (Sgunibu et al., 2012)

- Social: Children with ADHD 50% lower odds of sports participation than children with asthma with higher incidences of screen time (Tanden et al., 2019); childhood ADHD associated with obesity (Kim et al., 2011); underlying lack of interpersonal empathy (Cordier et al., 2010); Playfulness indicators: ADHD group “typical” with some difficult items but difficulty with basic skills (sharking) (Wilkes-Gillan et al., 2014); seek green outdoor settings at a higher rate (Taylor & Kuo, 2011)

For motor, Papadopoulos and his group (2018) found that there is some difficulty with handwriting. They also reported the higher ADHD and lower motor proficiency scores, the more sleep problems. The fact that Jeremy had sleep problems made me want to look at his motor skills for this reason. This is another interesting one. Children with parent-reported motor issues received more PT than those with teacher-reported motor issues. The fact that we listen to the parents more than the teachers about motor issues is important to consider. Under-treated motor problems in children with ADHD are really due to a behavioral focus so that is why it tends to get missed.

Sleep deficits negatively affect inhibitory control (Cremone-Caira et al., 2019). If we know that these kids have inhibition issues, we need to help them get some sleep. Poor sleep is only reinforcing their challenges and making it worse. They found that there were difficulties initiating and maintaining sleep at a rate of 20 to 50% of kids with ADHD (Corkum et al., 1998). Now, granted, that was 20 years ago, but they have replicated that since. And, if you have a sleep disorder, there is an 84.8% chance that it is negatively affecting your quality of life (Yurumez & Gunay Kilic, 2013).

Motor skills and executive functions are related. If you have some motor difficulties, it is going to influence your executive function ability (Pan et al., 2015). Boys with ADHD have lower executive function ability than typical peers on both performance-based and parent report tools, thus, it is really important that you use a combination of both performance and parent report tools (Sgunibu et al., 2012).

Children with ADHD are 50% less likely to participate in sports than children with asthma (Tanden et al., 2019). I find that amazing. Kids with ADHD also have a higher incidence of screen time usage, and we know that that is always a challenge (Tanden et al., 2019). Childhood ADHD is also associated with obesity. Hence, if you are not doing anything physical and you are sitting there watching your computer or playing video games, and you are impulsive, you are more likely to be obese (Kim et al., 2011). An underlying lack of interpersonal empathy can be something that you often see in ADHD. This affects social abilities and participation and success (Cordier et al., 2010). There are also playfulness indicators. An ADHD group might score as "typical" with some difficult play criteria, but then have more difficulty with basic items (Wilkes-Gillan et al., 2014). Their play may be developmentally out of whack. Again, they might be okay with some high-level types of behaviors, but then when it comes to something simple like taking turns or sharing, they cannot do it. Sometimes we have to go back and practice these rudimentary skills. This might be why they are struggling socially because they are having problems with age-inappropriate items. Lastly, these kids with ADHD really seek green outdoor settings at a higher rate (Taylor & Kuo, 2011). It would be interesting to monitor how outside time might influence their performance on assessments.

EF and Self-Regulation Connection

- Inhibitory control

- Cognitive/mental flexibility

- Working memory

Can these kids self-regulate? When they cannot, it does not work out well for them in school or at home, and it does not work out well in terms of social abilities. When they become adults, they have trouble keeping and maintaining a job. This is the definition of EF.

Some of you might be very familiar with this definition, but it is also quite complicated. This is how we remember information, filter distractions, resist impulses, and sustain attention during an activity that is also goal-directed. While we also adjust our plan as needed to avoid frustration in the process. That is a lot of working parts. Many times, you see people refer to executive functions like an air traffic controller of information and materials. These are the "big 3."

This is how we remember information, filter distractions, resist impulses, and sustain attention during an activity that is goal-directed while adjusting our plan as necessary and avoiding frustration!

Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex "frontal lobe" tasks: A latent variable analysis, Cognitive Psychology, 41 , 49-100.

- Impulse Control

- socially acceptable (Olson, 2010)

- Ability to store, update and manipulate /process information over short periods of time (Best & Miller, 2010)

- “Limited-capacity information-processing system” (Roman et al., 2015)

- Verbal, visuospatial, and coordinating central executive

- Ability to think flexibly and shift perspective and approaches easily, critical to learning new ideas (different perspectives)

- Switching between two or more mental sets with each set containing several tasks rules

- Feedback related (unlike inhibition) (Best & Miller, 2010)

All these things are important, but the three basic dimensions are inhibitory control, which develops first around four years of age, cognitive and mental flexibility, and working memory. Mental flexibility is the result of inhibitory control and working memory working together. If you have a problem with inhibition or working memory, or both, you are going to have problems with cognitive flexibility. The flip side of that would be rigidity. It is also being able to shift your thinking in the moment back and forth. The flip side of that would be to be stuck. Working memory is the ability to use your memory functionally. It is very important to know that we only have a very limited amount of memory capacity, and it is all we have. I like to call my working memory my suitcase. You have to make sure you pack the right things in there for the trip that you are going on. If you pack your suitcase for Fiji and you are going to Alaska, you are going to be on the beach with boots and a parka and be miserable. It is really important that we pull in the information that we need. This takes sustained attention. If you cannot sustain your attention, you are not going to capture the right memories. And again, if there are problems with inhibitory control or impulse control, this is going to be challenging. Impulse control is controlling yourself in the moment. If I can string those together, now I have more self-regulation ability. Again, these are the big three: inhibition, working memory, and cognitive flexibility and shifting.

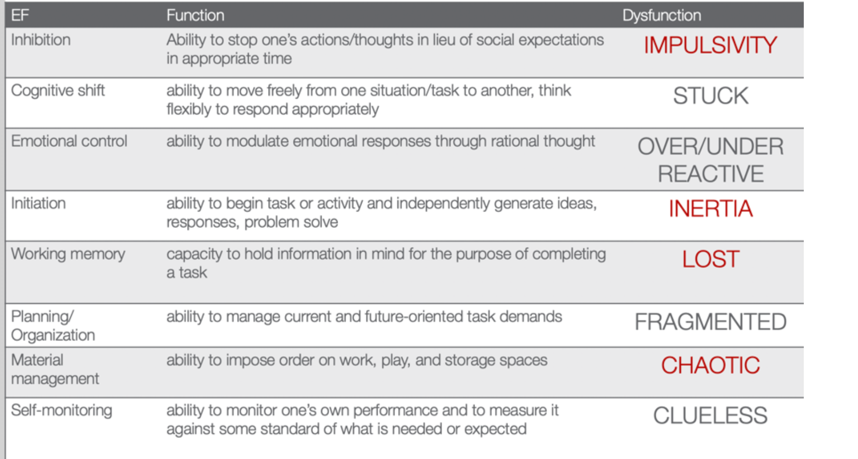

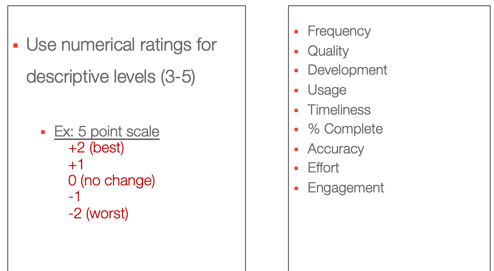

I already explained these, but I want you to appreciate what the research says. Inhibition requires an arbitrary rule to be held in your mind while you are inhibiting one response to produce an alternative response, which is typically the one that is more socially acceptable. Working memory is storing, updating, and manipulating information over short periods of time. It has a limited capacity, and it is verbal and visuospatial. Then, for cognitive shifting and flexibility, there are two pieces to it. It is being open and being able to shift. Here is what is interesting. Cognitive flexibility and shifting respond really well to internal feedback. You can actually start to observe things and gain some insight and make changes. Why that is important is because inhibition does not get better from internal feedback. It only gets better from external feedback. Think about someone you know who interrupts a lot because they are impulsive. They see that they do it and do not change because no one has said anything to them. It requires external feedback for them to say, "Oh, I'm doing it wrong." We do not have this internal mechanism to change our impulsivity. We cannot assume these kids will figure it out and fix it, because they will not. We have to be very stern and to the point and say, "You're doing it wrong. This is why it's wrong and here's what you need to do instead." This is the key. Figure 4 is an executive function cheat sheet.

(Cooper-Kahn & Dietzel, 2008)

Figure 4. EF cheat sheet.

This is from Cooper-Kahn and Dietzel (2008). They tell you the executive function, what the function is, and then the end dysfunction. For inhibition, the dysfunction is impulsive. If you cannot cognitively shift, you can get stuck. If you do not have emotional control, you are going to be over or under-reactive. If you cannot initiate a task, you are stuck in inertia. If you do not have a good working memory, you are lost. If you cannot plan and organize, you are fragmented. If you cannot manage your materials, you are chaotic. And then, if you cannot self-monitor, you are clueless. The red ones are those that Jeremy struggled with. He was impulsive, had inertia, was lost, and chaotic. He was also a little fragmented and had a difficult time with organization. However, these four things were his biggest challenges.

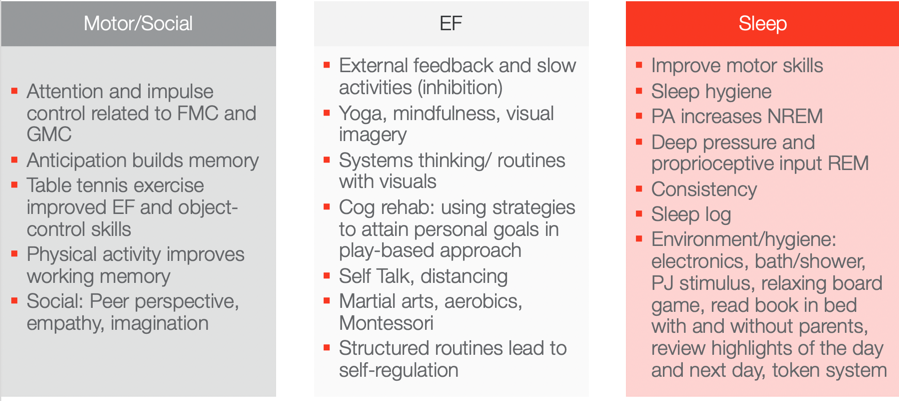

Review of Evidence-based Interventions for Case

One of the objectives is to talk about evidence and how we are going to use the evidence to support our intervention. I focused on motor, social, executive functions, and sleep. These are the things that were assessed that also had evidence for different intervention strategies (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Evidence-based interventions ((Hui Tseng, et al., 2004; Hahn-Markowitz et al., 2016; Washington University, n.d.; Diamond & Lee, 2011; White & Carlson, 2016; Winsler et al., 2009; Marjorek et al., 2004; Kuhn & Floress, 2008; Frike et al, 2006; Keshavarzi et al., 2014).

Motor/Social Categories

Let's look at the motor and social categories. What is really interesting is that attention and impulse control are related to fine motor and gross motor coordination. If we can work on coordination, we can also increase attention and impulse control. This is killing two birds with one stone in Jeremy's case. I do not know who is familiar with Hebbian's law, but it says is that the (brain) cells that fire together wire together. One of the ways to do that is through the concept of anticipation. Anticipation builds memory capacity and will improve working memory. Anticipation is a context, and you can basically put anticipation in anything. With turn-taking, there is anticipation. If there is a competition, there is anticipation among the competitors. If you know you are going to be called on, there is anticipation. If you are playing a game where something might jump out, there is anticipation. These are just a few examples of where you can build in anticipation. If you can add that into your activities, you can build memory capacity. Another study looked at how table tennis exercises improved executive function and object control skills. Table tennis does not require a lot of heavy-duty cardio and it is not a tiring exercise, but it requires a lot of hand-eye coordination and sustained attention. I think this is a really good occupation-based strategy to improve executive function and object control. Physical activity also improves working memory. I have had tons of success with kids doing physical activity both in therapy and at home to improve their working memory. Some of the social strategies that work really for kids, and we will talk about a few in a little bit, is taking a peer's perspective and working on empathy and imagination. These things were really shown to be effective ways to change someone's social success.

Executive Function

For executive function, you have to give them external feedback. You have to tell them when they are being impulsive, and then you have to tell them how to fix it. These are kids who are on a very fast, impulsive temporal context. I talk to them about the hare versus the turtle. I tell them to be more like the turtle. Yoga, mindfulness, and visual imagery are other strategies. Yoga and mindfulness are occupations, and you can incorporate visual imagery into any occupation. They are so effective especially living in a very stressful, fast-paced society. There is self-distancing involved which we know also helps with the social skills for these kids. Systems thinking and routines with visuals are other options. The more visuals we use, the better for these kids. If we can give them visual imagery, it helps. Here is an example of systems thinking. You have family coming over for Thanksgiving dinner. There are 17 people coming and three courses. Each dish takes this long and I need these ingredients for each. Additionally, these dishes all cook at different times so they come out at the right time. This is systems thinking. As a strategy, I gather my recipes and my materials and then put them in order for which ones I have to cook first and for how long. I form a little assembly line of what I am going to do. We can use this type of strategy for kids who struggle with material management and organization. It can be a game-changer. Other ideas include self-talk, martial arts, aerobics, and Montessori. I do not know if anyone has any experience with a Montessori approach. One of the reasons why it is effective is because Montessori uses self-distancing activities. Telling the kids what you want them to do instead of what you do not want them to do really works. It also includes structured routines that lead to self-regulation.

The last section shows that motor skills, as well as sleep hygiene, can improve sleep. Physical activity actually increases non-REM sleep. Deep pressure and proprioceptive can increase REM sleep. A sleep log is actually evidence-based as well. Shortly, I am going to describe a routine that works with kids that is evidence-based. All of these things here you can use as your evidence-based toolkit to work with kids with ADHD.

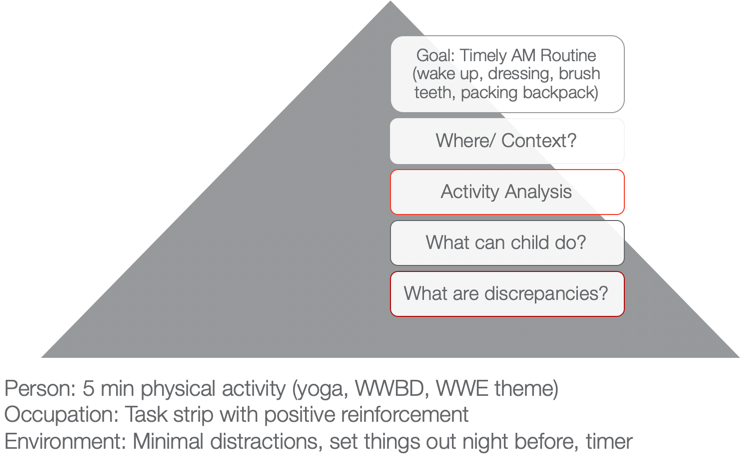

Case Study Application- Improve ADLs

Top-down analysis.

Jeremy's goal is to have a timely morning routine which involves waking up, dressing, brushing teeth, and packing a backpack. This is a top-down analysis in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Example of a top-down analysis for ADL routine.

When we use a top-down approach, we are starting with the actual occupation and the goal is to look at where this happens and in what context. I want you to think about where that would happen. In Jeremy's case, it is his bedroom and bathroom. Activity analysis is the bread and butter of OTs. His routine consists of waking up, dressing, brushing his teeth, and packing a backpack. During this analysis, we want to see what he can do and what he cannot do. What are some of your thoughts? Here are some answers from our audience:

- Being aware of time during all tasks/Using a timer. You are seeing a discrepancy between time awareness, time estimation, time monitoring, and time management. I would agree with you that he probably has a hard time all of those.

- Packing the backpack. We know that he is sleepy in the morning and he has a difficult time staying organized. This is especially true if he is half asleep or stressed in the morning.

- Finding his folders. Folders can be elusive sometimes to these kids, so that is a great point. Folders can be found in very strange places.

- Hygiene/organization. Even in hygiene, it is important to make sure that they are organized.

I used a PEO or person-occupation-environment perspective here. We started with some physical activity in the morning to help him to wake up. We did yoga. I asked, "What would Batman do?" He was a big Batman guy. We did some self-distancing by him coming up with strategies for Batman. Or, we used a wresting theme. These activities helped him to be more alert and be able to increase his attention.

We also used a task strip with positive reinforcement to help him see what he needed to do. Visuals can be very helpful for these kids.

Then, we used minimal distractions. We set things out the night before and used that visual so he could match things. We also devised a place where his folders could go. This all might seem trivial, but it really matters for this type of kid. The timer helps as well. You can make it a game.

Activities to Improve ADLs

- Focus on physical activity, motor skills with automaticity and incorporate aspects of yoga to increase sustained attention and memory

- Visual supports and routine with structure

- Self-talk and self-distancing strategies

- Positively reward

To improve ADLs, the key is to focus on physical activity and motor skills with the goal of automaticity. For example, we can incorporate yoga to increase sustained attention and memory. As we talked about earlier, visual supports and structured routines are other great ideas. I cannot emphasize enough the idea of self-talk. This helps with self-regulation and impulsivity on a lower level. The ability to "self-talk" should be pretty solid for kids around the age of seven, but the kids that we are talking about lack this skill. Self-distancing, or having them give strategies to someone other than themselves, is also great. Let them problem-solve and talk it through for someone else, like Batman or John Cena. This way they do not feel like they are picking on themselves or feeling pressured to figure it out for themselves. They are figuring out for someone else, and this strategy is evidence-based. We often forget to positively reward these kids. I like to do something like time with mom and dad, I develop short-term and long-term rewards with mom and dad. For example, Jeremy wanted a wrestling figure for his long term reward. But on a daily basis, he got wrestling bucks and that bought time to wrestle with dad on the weekends.

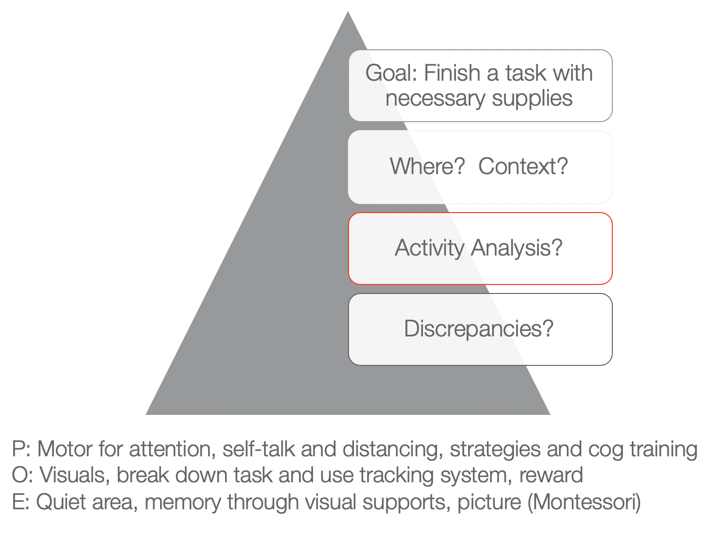

Case Study Application- Finish a Task with Necessary Supplies

Figure 7. Example of a top-down analysis for finishing a task with necessary supplies.

The next goal is to finish a task with the necessary supplies. You can fill in whatever task that he needed to do like homework, hygiene, or whatever it was with the necessary supplies. Typically, he would start something and then not have all the supplies he needed. He would then run to go get something and then lose track of what he was doing. Activities would not get done and then there would be a mess. We want to know when this would happen and the context. What is required of that activity, and then what can he do versus what he cannot do? Those are the discrepancies.

As I stated a few moments ago, he tends to not have the needed materials. That is the first issue right out of the gate. And because he is impulsive, he starts doing something else. Eventually, he does not finish anything due to a lack of persistence and distractibility. From a personal standpoint, we could work on using motor tasks for increased attention. We know that fine motor and gross motor tasks are going to help. We could also look at using coordination tasks, self-talk, and distancing. Cognitive training is also evidence-based. Can they start to use a checklist or something to create a better strategy?

Then, from an occupation standpoint, again we can use visuals and break down the task. We can also use a tracking system that we are going to go over in just a second.

From an environmental aspect, we can encourage the use of quiet areas to help with sustained attention and better memory. Here we can also use some visual supports or a Montessori approach. "This is what the task is supposed to look like when I am finished." If we have a task, what does the end result look like so that the person knows? And even better, what are the supplies pictured so I know what I have to get first, and then I know what the end result should look like. That is super helpful for someone who is so disorganized when putting materials together.

Activities for Completing Tasks

- Inhibition: Self-talk, slowing down, self-distancing, external feedback

- WM: physical activity

- Attention: physical activity

- Using environmental strategies and visuals to support

- Behavioral: task breakdown, positive reinforcers

- Occupation-based is imperative!

We want to use occupation-based tasks, but we want them to be fun and let the child make a choice. When things are getting easier, we can then move toward less preferred tasks. For example, we do not want to start with homework.

Case Study Application: Social

- Involve a peer or sibling

- Play-based model:

- Capture intrinsic motivations (WWE)

- Empathy focus

- Arrange the environment to foster mutually enjoyable social interaction and imagination

- Teaching social play language and reading expressive body language (can use dogs and their behavior)

- Incorporate parents and coach them so they can coach outside of therapy

(Cordier et al., 2009; Wilkes-Gillan et al., 2016)

There is a play-based model that is evidence-based. They recommend involving a peer or sibling. This play-based model focuses on intrinsic motivation. With Jeremy, we could do wrestling. We could focus on empathy. It is important to arrange the environment so that it is mutually enjoyable. We need to teach social play language and reading expressive body language. The evidence was interesting as it said to use dogs because it could help the child start to read behaviors. Dogs are a little bit easier than people. Jeremy loves dogs so that would work. You could then incorporate parents in order to coach him outside of therapy. They found that to be very successful.

Case Study Application: Sleep

- Turn off electronics 2 hours prior

- Hot bath or shower

- PJs prepped

- Boardgame in room

- Read in bed (parents, then alone

- Highlights with organizer, feelings

- Token reward system

- Flexibility on weekends

- Sleep logs are evidence-based

- Physical activity during day imperative

(Kuhn & Floress, 2008; Fricke et al., 2006)