Rhetorical Questions in Essays: 5 Things you should Know

Rhetorical questions can be useful in writing. So, why shouldn’t you use rhetorical questions in essays?

In this article, I outline 5 key reasons that explain the problem with rhetorical questions in essays.

Despite the value of rhetorical questions for engaging audiences, they mean trouble in your university papers. Teachers tend to hate them.

There are endless debates among students as to why or why not to use rhetorical questions. But, I’m here to tell you that – despite your (and my) protestations – the jury’s in. Many, many teachers hate rhetorical questions.

You’re therefore not doing yourself any favors in using them in your essays.

Rhetorical Question Examples

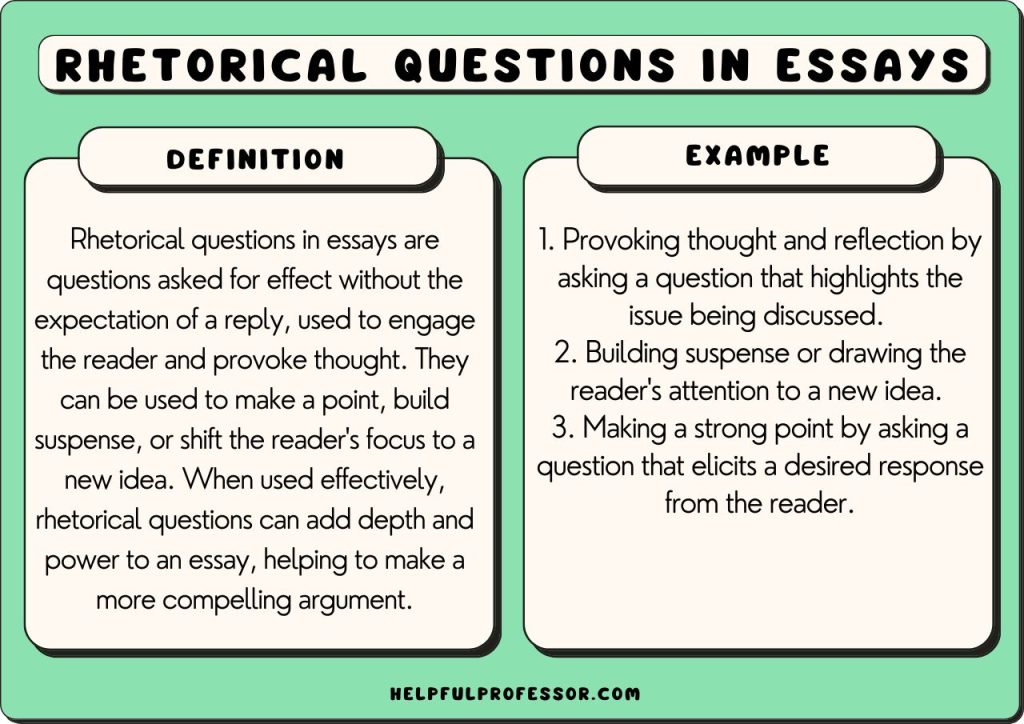

A rhetorical question is a type of metacommentary . It is a question whose purpose is to add creative flair to your writing. It is a way of adding style to your essay.

Rhetorical questions usually either have obvious answers, or no answers, or do not require an answer . Here are some examples:

- Are you seriously wearing that?

- Do you think I’m that gullible?

- What is the meaning of life?

- What would the walls say if they could speak?

I understand why people like to use rhetorical questions in introductions . You probably enjoy writing. You probably find rhetorical questions engaging, and you want to draw your marker in, engage them, and wow them with your knowledge.

1. Rhetorical Questions in Academic Writing: They Don’t belong.

Rhetorical questions are awesome … for blogs, diaries, and creative writing. They engage the audience and ask them to predict answers.

But, sorry, they suck for essays. Academic writing is not supposed to be creative writing .

Here’s the difference between academic writing and creative writing:

- Supposed to be read for enjoyment first and foremost.

- Can be flamboyant, extravagant, and creative.

- Can leave the reader in suspense.

- Can involve twists, turns, and surprises.

- Can be in the third or first person.

- Readers of creative writing read texts from beginning to end – without spoilers.

Rhetorical questions are designed to create a sense of suspense and flair. They, therefore, belong as a rhetorical device within creative writing genres.

Now, let’s look at academic writing:

- Supposed to be read for information and analysis of real-life ideas.

- Focused on fact-based information.

- Clearly structured and orderly.

- Usually written in the third person language only.

- Readers of academic writing scan the texts for answers, not questions.

Academic writing should never, ever leave the reader in suspense. Therefore, rhetorical questions have no place in academic writing.

Academic writing should be in the third person – and rhetorical questions are not quite in the third person. The rhetorical question appears as if you are talking directly to the reader. It is almost like writing in the first person – an obvious fatal error in the academic writing genre.

Your marker will be reading your work looking for answers , not questions. They will be rushed, have many papers to mark, and have a lot of work to do. They don’t want to be entertained. They want answers.

Therefore, academic writing needs to be straight to the point, never leave your reader unsure or uncertain, and always signpost key ideas in advance.

Here’s an analogy:

- When you came onto this post, you probably did not read everything from start to end. You probably read each sub-heading first, then came back to the top and started reading again. You weren’t interested in suspense or style. You wanted to find something out quickly and easily. I’m not saying this article you’re reading is ‘academic writing’ (it isn’t). But, what I am saying is that this text – like your essay – is designed to efficiently provide information first and foremost. I’m not telling you a story. You, like your teacher, are here for answers to a question. You are not here for a suspenseful story. Therefore, rhetorical questions don’t fit here.

I’ll repeat: rhetorical questions just don’t fit within academic writing genres.

2. Rhetorical Questions can come across as Passive

It’s not your place to ask a question. It’s your place to show your command of the content. Rhetorical questions are by definition passive: they ask of your reader to do the thinking, reflecting, and questioning for you.

Questions of any kind tend to give away a sense that you’re not quite sure of yourself. Imagine if the five points for this blog post were:

- Are they unprofessional?

- Are they passive?

- Are they seen as padding?

- Are they cliché?

- Do teachers hate them?

If the sub-headings of this post were in question format, you’d probably – rightly – return straight back to google and look for the next piece of advice on the topic. That’s because questions don’t assist your reader. Instead, they demand something from your reader .

Questions – rhetorical or otherwise – a position you as passive, unsure of yourself, and skirting around the point. So, avoid them.

3. Rhetorical Questions are seen as Padding

When a teacher reads a rhetorical question, they’re likely to think that the sentence was inserted to fill a word count more than anything else.

>>>RELATED ARTICLE: HOW TO MAKE AN ESSAY LONGER >>>RELATED ARTICLE: HOW TO MAKE AN ESSAY SHORTER

Rhetorical questions have a tendency to be written by students who are struggling to come to terms with an essay question. They’re well below word count and need to find an extra 15, 20, or 30 words here and there to hit that much-needed word count.

In order to do this, they fill space with rhetorical questions.

It’s a bit like going into an interview for a job. The interviewer asks you a really tough question and you need a moment to think up an answer. You pause briefly and mull over the question. You say it out loud to yourself again, and again, and again.

You do this for every question you ask. You end up answering every question they ask you with that same question, and then a brief pause.

Sure, you might come up with a good answer to your rhetorical question later on, but in the meantime, you have given the impression that you just don’t quite have command over your topic.

4. Rhetorical Questions are hard to get right

As a literary device, the rhetorical question is pretty difficult to execute well. In other words, only the best can get away with it.

The vast majority of the time, the rhetorical question falls on deaf ears. Teachers scoff, roll their eyes, and sigh just a little every time an essay begins with a rhetorical question.

The rhetorical question feels … a little ‘middle school’ – cliché writing by someone who hasn’t quite got a handle on things.

Let your knowledge of the content win you marks, not your creative flair. If your rhetorical question isn’t as good as you think it is, your marks are going to drop – big time.

5. Teachers Hate Rhetorical Questions in Essays

This one supplants all other reasons.

The fact is that there are enough teachers out there who hate rhetorical questions in essays that using them is a very risky move.

Believe me, I’ve spent enough time in faculty lounges to tell you this with quite some confidence. My opinion here doesn’t matter. The sheer amount of teachers who can’t stand rhetorical questions in essays rule them out entirely.

Whether I (or you) like it or not, rhetorical questions will more than likely lose you marks in your paper.

Don’t shoot the messenger.

Some (possible) Exceptions

Personally, I would say don’t use rhetorical questions in academic writing – ever.

But, I’ll offer a few suggestions of when you might just get away with it if you really want to use a rhetorical question:

- As an essay title. I would suggest that most people who like rhetorical questions embrace them because they are there to ‘draw in the reader’ or get them on your side. I get that. I really do. So, I’d recommend that if you really want to include a rhetorical question to draw in the reader, use it as the essay title. Keep the actual essay itself to the genre style that your marker will expect: straight up the line, professional and informative text.

“97 percent of scientists argue climate change is real. Such compelling weight of scientific consensus places the 3 percent of scientists who dissent outside of the scientific mainstream.”

The takeaway point here is, if I haven’t convinced you not to use rhetorical questions in essays, I’d suggest that you please check with your teacher on their expectations before submission.

Don’t shoot the messenger. Have I said that enough times in this post?

I didn’t set the rules, but I sure as hell know what they are. And one big, shiny rule that is repeated over and again in faculty lounges is this: Don’t Use Rhetorical Questions in Essays . They are risky, appear out of place, and are despised by a good proportion of current university teachers.

To sum up, here are my top 5 reasons why you shouldn’t use rhetorical questions in your essays:

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Social-Emotional Learning (Definition, Examples, Pros & Cons)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ What is Educational Psychology?

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ What is IQ? (Intelligence Quotient)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Best can you ask rhetorical questions in a research paper

Home » Questions » Best can you ask rhetorical questions in a research paper

When it comes to writing a research paper, there are certain rules and guidelines that need to be followed to ensure the paper’s credibility and effectiveness. One common question that often arises is whether or not it is appropriate to ask rhetorical questions in a research paper. Rhetorical questions are those that do not require an answer, but are asked to create a certain effect or provoke thought. In this article, we will explore whether or not rhetorical questions have a place in research papers.

In general, research papers are meant to be objective and informative, providing evidence-based arguments and analysis. Rhetorical questions, on the other hand, are often used in persuasive writing or speeches to engage the audience and make them think about a particular issue. Therefore, using rhetorical questions in a research paper may seem out of place.

However, there are instances where rhetorical questions can be effectively used in a research paper. For example, if you are discussing a controversial topic or presenting a hypothesis, asking a rhetorical question can help to stimulate critical thinking and engage the reader. It can also be used to highlight a key point or draw attention to a specific aspect of your research.

See these Can You Ask Rhetorical Questions in a Research Paper

- Are there any ethical concerns surrounding genetic engineering?

- Can we really trust the data provided by social media platforms?

- Is it possible to achieve world peace?

- Do video games have a negative impact on children’s behavior?

- Should the death penalty be abolished?

- Are humans the main cause of climate change?

- Can technology solve the world’s environmental problems?

- Is it fair to use animals for scientific experiments?

- Do school uniforms promote a sense of unity among students?

- Can art be used as a form of therapy?

- Should the government regulate the use of artificial intelligence?

- Is democracy the best form of government?

- Can social media help to bridge cultural divides?

- Do standardized tests accurately measure a student’s intelligence?

- Should genetically modified organisms be labeled?

- Are alternative energy sources a viable solution to fossil fuel depletion?

- Can meditation improve mental health?

- Is it possible to achieve work-life balance in today’s society?

- Do celebrities have a responsibility to be role models?

- Should the government provide free healthcare for all?

- Are there any long-term effects of childhood vaccination?

- Can music therapy be used to treat depression?

- Is it ethical to use animals for entertainment purposes?

- Do violent video games contribute to real-life aggression?

- Should the legal drinking age be lowered?

- Are there any benefits to genetically modified crops?

- Can social media help to combat social isolation?

- Is it possible to achieve gender equality in the workplace?

- Do reality TV shows accurately depict real life?

While it is important to use rhetorical questions sparingly in a research paper, they can be used effectively to enhance your argument and engage the reader. Just make sure that the rhetorical questions you use are relevant to your topic and add value to your research. Remember to maintain the overall objectivity and credibility of your paper and use rhetorical questions as a tool to support your argument, rather than distract from it.

Related Post:

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Best nickname for coors banquet beer

Best easter poems for youth

Best adventhealth interview questions

Best a man called ove quotes with page numbers

Best false assumption riddles

Best group name for 6 people

© the narratologist 2024

- How It Works

- Prices & Discounts

How to Use Rhetorical Questions in Essay Writing Effectively

Table of contents

If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh?

If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?

These lines are from William Shakespeare’s play, The Merchant of Venice, wherein he uses consecutive rhetorical questions to evoke a sense of human empathy. This literary technique certainly worked here because the speech manages to move us and pushes us to think.

Writers have been incorporating rhetorical questions together for centuries. So, why not take inspiration and include it in your college essays, too?

A rhetorical question is asked more to create an impact or make a statement rather than get an answer. When used effectively, it is a powerful literary device that can add immense value to your writing.

How do you use rhetorical questions in an essay?

Thinking of using rhetorical questions? Start thinking about what you want your reader to take away from it. Craft it as a statement and then convert it into a rhetorical question. Make sure you use rhetorical questions in context to the more significant point you are trying to make.

When Should You Write Rhetorical Questions in Your Essay?

Are you wondering when you can use rhetorical questions? Here are four ways to tactfully use them to elevate your writing and make your essays more thought-provoking.

#1. Hook Readers

We all know how important it is to start your essay with an interesting essay hook that grabs the reader’s attention and keeps them interested. Do you know what would make great essay hooks? Rhetorical questions.

When you begin with a rhetorical question, you make the reader reflect and indicate where you are headed with the essay. Instead of starting your essay with a dull, bland statement, posing a question to make a point is a lot more striking.

How you can use rhetorical questions as essay hooks

Example: What is the world without art?

Starting your essay on art with this question is a clear indication of the angle you are taking. This question does not seek an answer because it aims to make readers feel that the world would be dreary without art.

#2. Evoke Emotions

Your writing is considered genuinely effective when you trigger an emotional response and strike a chord with the reader.

Whether it’s evoking feelings of joy, sadness, rage, hope, or disgust, rhetorical questions can stir the emotional appeal you are going for. They do the work of subtly influencing readers to feel what you are feeling.

So, if you want readers to nod with the agreement, using rhetorical questions to garner that response is a good idea, which is why they are commonly used in persuasive essays.

Example: Doesn’t everyone have the right to be free?

What comes to your mind when you are met with this question? The obvious answer is – yes! This is a fine way to instill compassion and consideration among people.

#3. Emphasize a Point

Making a statement and following it up with a rhetorical question is a smart way to emphasize it and drive the message home. It can be a disturbing statistic, a well-known fact, or even an argument you are presenting, but when you choose to end it with a question, it tends to draw more emphasis and makes the reader sit up and listen.

Sometimes, rather than saying it as a statement, inserting a question leaves a more significant impact.

Example: Between 700 and 800 racehorses are injured and die yearly, with a national average of about two breakdowns for every 1,000 starts. How many will more horses be killed in the name of entertainment?

The question inserted after presenting such a startling statistic is more to express frustration and make the reader realize the gravity of the situation.

#4. Make a Smooth Transition

One of the critical elements while writing an essay is the ability to make smooth transitions from one point or section to another and, of course, use the right transition words in your essay . The essay needs to flow logically while staying within the topic. This is a tricky skill, and few get it right.

Using rhetorical questions is one way to connect paragraphs and maintain cohesiveness in writing. You can pose questions when you want to introduce a new point or conclude a point and emphasize it.

Example: Did you know that Ischaemic heart disease and stroke are the world’s biggest killers? Yes, they accounted for a combined 15.2 million deaths in 2016.

Writing an essay on the leading causes of death? This is an intelligent way to introduce the reason and then go on to explain it.

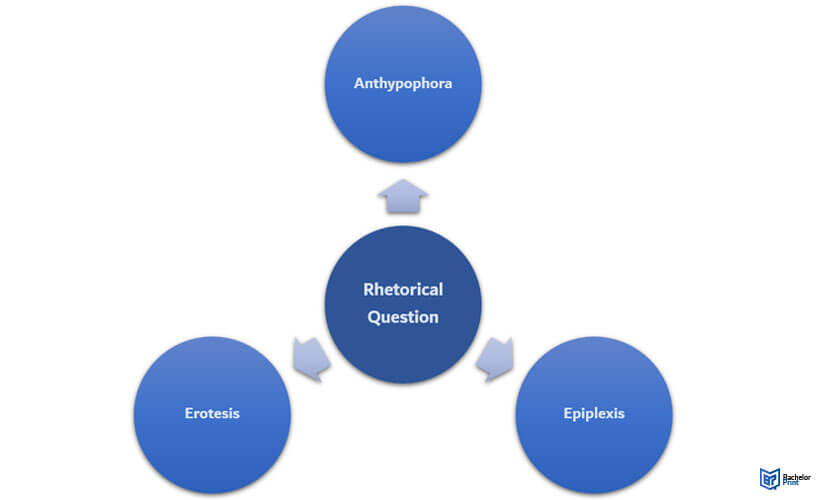

What are the types of rhetorical questions?

There are three different kinds of rhetorical questions you can use in your essays:

Epiplexis : This rhetorical question is meant to express disapproval or shame to the reader. It is not meant to obtain an answer; it is a way to convince the reader by demonstrating frustration or grief.

Erotesis : This is used to express strong affirmation or denial. It usually implies an answer without giving the expectations of getting one. Erotesis or erotica is used to push the reader to ponder and reflect.

Hypophora : When a question is raised and is immediately answered, it is referred to as hypophora. It is used in a conversational style of writing and aids in generating curiosity in the reader. It’s also a way to make smooth transitions in the essay while letting the writer completely control the narrative.

What to AVOID while writing rhetorical questions in your essay?

It is important to use them sparingly and wherever appropriate. Rhetorical questions cannot be used in every piece of writing.

Using rhetorical questions in the thesis statement : Asking a rhetorical question in your thesis statement is an absolute no-no because thesis statements are meant to answer a question, not pose another question.

Overusing rhetorical questions : Sub7jecting the reader to an overdose of rhetorical questions, consequently or not, makes for an annoying reading experience.

Using rhetorical questions in research papers : Research papers require you to research a topic, take a stand and justify your claims. It’s a formal piece of writing that must be based on facts and research.

So, keep this literary device for persuasive or argumentative essays and creative writing pieces instead of using them in research papers.

20 Ideas of Good Rhetorical Questions to Start an Essay

- "What if the world could be free of poverty?"

- "Is it really possible to have peace in a world so full of conflict?"

- "Can we ever truly understand the depths of the universe?"

- "What does it really mean to be happy?"

- "Is technology bringing us closer together, or driving us apart?"

- "How far would you go to stand up for what you believe in?"

- "What if we could turn back time and prevent disasters?"

- "Can a single person really make a difference in the world?"

- "Is absolute freedom a blessing or a curse?"

- "What defines true success in life?"

- "Are we truly the masters of our own destiny?"

- "Is there a limit to human creativity?"

- "How does one moment change the course of history?"

- "What if we could read each other's thoughts?"

- "Can justice always be served in an imperfect world?"

- "Is it possible to live without regret?"

- "How does culture shape our understanding of the world?"

- "Are we responsible for the happiness of others?"

- "What if the cure for cancer is just around the corner?"

- "How does language shape our reality?"

While rhetorical questions are effective literary devices, you should know when using a rhetorical question is worthwhile and if it adds value to the piece of writing.

If you are struggling with rhetorical questions and are wondering how to get them right, don’t worry. Our professional essay writing service can help you write an essay using the correct literary devices, such as rhetorical questions, that will only alleviate your writing.

Share this article

Achieve Academic Success with Expert Assistance!

Crafted from Scratch for You.

Ensuring Your Work’s Originality.

Transform Your Draft into Excellence.

Perfecting Your Paper’s Grammar, Style, and Format (APA, MLA, etc.).

Calculate the cost of your paper

Get ideas for your essay

Should you use Rhetoric Questions in an Essay?

Rhetorical questions are questions asked to make a point or to create a dramatic effect rather than to get an answer.

Many college professors discourage using rhetorical questions in essays, and the majority agree that they can be used only in specific circumstances.

While they are helpful for the person writing an essay, if you want to include them in an essay, ensure that you rephrase them into a sentence, indirect question, or statement.

It is essential to say that there is only minimal space for including rhetorical questions in academic writing.

This post will help you discover why professors discourage using rhetorical questions in essays and when it is okay to use them. Let's dive in!

Why do professors discourage the use of rhetorical questions in academic papers?

We love rhetorical questions for the flair they add to written pieces. They help authors achieve some sense of style when writing essays. However, since they have an obvious answer, no answer, or require no answer, they have no place in academic writing, not even the essay hooks. They are a way to engage the audience by letting them keep thinking of the answer as they read through your text. Avoid using rhetorical essays in academic writing unless you are doing creative writing. There is no room for suspense in academic writing. Let’s find out why professors discourage them so badly in any form of academic writing, not just essay writing alone!

1. Because they don't belong in academic writing

Rhetorical questions are awesome; they can help engage your readers and keep them interested in your writing. However, they are only perfect for creative writing, diaries, and blogs and are not appropriate for academic writing. This is because academic writing is about logic, facts, and arguments, while rhetorical questions are about entertainment. The two are incompatible; the questions do not belong in academic writing.

Rhetorical questions are typically utilized in creative writing to create flair and suspense. However, academic writing does not need flair or suspense. Because most academic writing assignments are based on facts, evidence, arguments, and analysis. Thus, there is no need for the creation of flair or suspense. In other words, there is no space for rhetorical questions in academic writing.

Another thing that shows that rhetorical questions don't belong in academic writing is that they are usually written in the first person. The fact that they are written in the first person means they do not fit in academic writing, where students are usually urged to write in the third person. So while it is okay for rhetorical questions to feature in creative writing where the author addresses the reader, it is not okay for the questions to feature in academic writing where everything should be matter-of-fact.

Lastly, rhetorical questions do not belong in academic writing because readers of academic works do not expect to see them. When you start reading an academic paper, you expect answers, and you don't expect suspense, flair, or entertainment. Therefore, you will most likely be confused and even upset when you see rhetorical questions in an academic paper.

2. Because they come across as passive

When writing an academic paper as a student, you are expected to show your mastery of the content; you are expected to demonstrate your command of the content. What you are not likely to do is to pose rhetorical questions, and this is because the questions are passive and, therefore, unsuitable for academic papers. Specifically, passive voice is unsuitable for academic papers because it is dull and lazy. What is appropriate and recommended for academic papers is active voice, and this is because it is clear and concise.

You now know why you should not use passive rhetorical questions in academic papers. Another reason why you should not use passive rhetorical questions is that they will make you sound as if you are unsure of yourself. If you are sure about the points and arguments you are making in your paper, you will not ask passive rhetorical questions. Instead, you will develop your paper confidently from the introduction to the conclusion.

When you ask your readers passive rhetorical questions, you will make them Google or think about the answer. These are not the things that readers want to be doing when reading academic papers. They want to see well-developed ideas and arguments and be informed, inspired, and educated. Thus, you should spare them the need to do things they do not plan to do by not using rhetorical questions in your academic paper.

3. Because they are seen as padding

When your professor sees a rhetorical question in your essay, they will think you are just trying to fill the minimum word count. In other words, they will think you are trying to cheat the system by filling the word count with an unnecessary sentence. This could lead to you getting penalized, which you do not want for your essay if you are aiming for a top grade.

Why do professors see rhetorical questions as padding? Well, it is because struggling students are the ones who typically use rhetorical questions in their essays. Therefore, when professors see these questions, they assume that the student struggled to meet the word count, so they throw in a few rhetorical questions.

4. Because they are hard to get right

It is not easy to ask rhetorical questions correctly, especially in essays. This is because there are several things to consider when asking them, including the location, the words, the punctuation, and the answer. Most of the time, when students ask rhetorical questions in their papers, professors roll their eyes because most students ask them wrong.

The correct way to ask a rhetorical question is to ask it in the right place, in the right way, and to use the correct punctuation. You will discover how to do these things in the second half of this post. Don't just ask a rhetorical question for the sake of it; ask only when necessary.

5. Because professors hate them

If the other reasons why professors discourage rhetorical questions have not convinced you to give up on using them, this one should. Professors hate rhetorical questions, and they don't like them because they feel the questions don't belong in academic papers. Therefore, when you use them, you risk irking your professor and increasing your likelihood of getting a lower grade. So if you don't want a lower grade, you should give rhetorical questions a wide berth.

Your professor might love rhetorical questions. However, including rhetorical questions in your essay is a risk you do not want to take. Because your hunch about them liking rhetorical questions might be wrong, resulting in a bad grade for you.

When to use rhetorical questions in academic papers

You now know professors do not like seeing rhetorical questions in academic papers. However, this does not mean you cannot use them. There are situations when it is okay to use rhetorical questions in your academic papers. Below you will discover the instances when it is appropriate to use rhetorical questions in your essays.

1. When introducing your essay

When introducing your essay, you must try to grab the reader's attention with your first two or three sentences. The best way to do this is to use a hook statement – an exciting statement that makes the reader want to read the rest of the paper to find out more. And the best way to write a hook statement is as a rhetorical question.

When you write your hook statement as a rhetorical question, you will make your reader think about the question and the topic before they continue to read your introduction . This will most likely pique their interest in the topic and make them want to read the rest of your essay.

Therefore, instead of starting your essay with a dull and ordinary hook statement, you should start it with a powerful rhetorical question. This will undoubtedly hook your reader. Below is a good example of a rhetorical question hook statement:

Where could the world be without the United Nations?

Starting your essay with the question above will definitely hook any reader and give the reader an idea of the angle you want to take in your essay.

2. When you want to evoke emotions

Most academic papers are supposed to be written in the third person and should also be emotionless, well-organized, and to the point. However, there are some that can be written in the first person. Good examples of such essays include personal essays and reflective essays.

When you are writing personal essays, it is okay to express emotions. And one of the best ways to do it is by using rhetorical questions. These questions are perfect for evoking emotions because they make the reader think and reflect. And making your reader think and reflect is an excellent way to make them relate to your story.

The most appropriate way to use rhetorical questions to evoke emotions is to make your questions target specific feelings such as rage, hope, happiness, sadness, and so on. Targeted questions will help your reader think about certain things and feelings, which will undoubtedly influence what they will feel thereafter. Below is an excellent example of a rhetorical question used to evoke emotions:

Doesn't everyone deserve to be free?

This question makes you feel compassion for those who are not free and makes you think about them and the things they are going through.

3. When you want to emphasize something

Using a rhetorical question to emphasize a point is okay, especially in a personal essay. The right way to do this is to make the statement you want to highlight and ask a rhetorical question immediately after. Emphasizing a statement using a rhetorical question will help drive your message home, and it will also help leave an impact on the reader. Below is an excellent example of a rhetorical question used to emphasize the statement before it:

Nearly 1000 racehorses die or get injured every year. Is the killing and maiming of horses justified in this age of cars and underground trains?

The rhetorical question above brings into sharp focus the statement about the number of horses killed yearly and makes the reader think about the number of horses killed or injured annually.

4. When you want to make a smooth transition

One of the best ways to transition from one topic to the next is by using a rhetorical question. It is essential to transition smoothly from one point to the next if you want your essay to have an excellent flow.

A rhetorical question can help you to make a smooth transition from one point to the next by alerting the reader to a new topic. Below is an excellent example of a rhetorical question used to make a smooth transition from one paragraph to the next:

Did you know malaria remains one of Africa's leading causes of infant mortality? The tropical disease accounted for over half a million infant deaths in 2020.

The statement above smartly alerts the reader about a new topic and introduces it in a smooth and calculated manner.

Mistakes to avoid when using rhetorical questions

If you decide to use rhetorical questions in your essays, there are some mistakes you should avoid.

1. Overusing them

Using rhetorical questions in academic papers is okay, but you should never overuse them. The number of rhetorical questions in your essay should never exceed two, and more than two rhetorical questions are just too many for an essay.

2. Using them in research papers

Research papers are the most formal of academic papers. Most professors who give research paper assignments do not fancy seeing rhetorical questions in them. Therefore, you should never use rhetorical questions in research papers.

3. Never use them as your thesis statement

Your thesis statement should be a statement that is logical, concise, and complete. It should never be a question, let alone a rhetorical one.

As you have discovered in this article, rhetorical questions should ideally not be used in essays. This is because they do not belong, professors hate them, and so on. However, as you have also discovered, there are some situations when it is okay to use rhetorical questions. In other words, you can use rhetorical questions in the right circumstances. The fact that you now know these circumstances should enable you to use rhetorical questions in your essays, if necessary, correctly.

You should talk to us if you are too busy to write your essay or edit it to make it professional enough. Our company provides both essay writing and essay editing services at affordable rates. Contact us today for assistance or simply order your essay using our essay order page.

What are rhetorical questions?

Rhetorical questions are questions asked to make a point rather than to get an answer. They are often used in creative writing to create a dramatic effect or a sense of suspense.

When and how to use rhetorical questions in essays

Professors hate rhetorical questions in essays . You should only use them sparingly and when necessary. Otherwise, you should not use them at all.

What mistakes should you avoid when using rhetorical questions in essays?

You should never use a rhetorical question instead of a good thesis statement . You should also never use a rhetorical question in a research paper.

Gradecrest is a professional writing service that provides original model papers. We offer personalized services along with research materials for assistance purposes only. All the materials from our website should be used with proper references. See our Terms of Use Page for proper details.

Chapter 9: The Research Process

9.1 Developing a Research Question

Emilie Zickel

“I write out of ignorance. I write about the things I don’t have any resolutions for, and when I’m finished, I think I know a little bit more about it. I don’t write out of what I know. It’s what I don’t know that stimulates me .” – Toni Morrison , author and Northeast Ohio native

Think of a research paper as an opportunity to deepen (or create!) knowledge about a topic that matters to you. Just as Toni Morrison states that she is stimulated by what she doesn’t yet know, a research paper assignment can be interesting and meaningful if it allows you to explore what you don’t know.

Research, at its best, is an act of knowledge creation, not just an extended book report. This knowledge creation is the essence of any great educational experience. Instead of being lectured at, you get to design the learning project that will ultimately result in you experiencing and then expressing your own intellectual growth. You get to read what you choose, and you get to become an expert on your topic.

That sounds, perhaps, like a lofty goal. But by spending some quality time brainstorming, reading, thinking or otherwise tuning into what matters to you, you can end up with a workable research topic that will lead you on an enjoyable research journey.

The best research topics are meaningful to you

- Choose a topic that you want to understand better.

- Choose a topic that you want to read about and devote time to

- Choose a topic that is perhaps a bit out of your comfort zone

- Choose a topic that allows you to understand others’ opinions and how those opinions are shaped.

- Choose something that is relevant to you, personally or professionally.

- Do not choose a topic because you think it will be “easy” – those can end up being even quite challenging

The video below offers ideas on choosing not only a topic that you are drawn to, but a topic that is realistic and manageable for a college writing class.

“Choosing a Manageable Research Topic” by PfaulLibrary is licensed under CC BY

Brainstorming Ideas for a Research Topic

Which question(s) below interest you? Which question(s) below spark a desire to respond? A good topic is one that moves you to think, to do, to want to know more, to want to say more.

There are many ways to come up with a good topic. The best thing to do is to give yourself time to think about what you really want to commit days and weeks to reading, thinking, researching, more reading, writing, more researching, reading and writing on.

- What news stories do you often see, but want to know more about?

- What (socio-political) argument do you often have with others that you would love to work on strengthening?

- What would you love to become an expert on?

- What are you passionate about?

- What are you scared of?

- What problem in the world needs to be solved?

- What are the key controversies or current debates in the field of work that you want to go into?

- What is a problem that you see at work that needs to be better publicized or understood?

- What is the biggest issue facing [specific group of people: by age, by race, by gender, by ethnicity, by nationality, by geography, by economic standing? choose a group]

- If you could interview anyone in the world, who would it be? Can identifying that person lead you to a research topic that would be meaningful to you?

- What area/landmark/piece of history in your home community are you interested in?

- What in the world makes you angry?

- What global problem do you want to better understand?

- What local problem do you want to better understand?

- Is there some element of the career that you would like to have one day that you want to better understand?

- Consider researching the significance of a song, or an artist, or a musician, or a novel/film/short story/comic, or an art form on some aspect of the broader culture.

- Think about something that has happened to (or is happening to) a friend or family member. Do you want to know more about this?

- Go to a news source ( New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Christian Science Monitor, etc) and skim the titles of news stories. Does any story interest you?

From Topic to Research Question

Once you have decided on a research topic, an area for academic exploration that matters to you, it is time to start thinking about what you want to learn about that topic.

The goal of college-level research assignments is never going to be to simply “go find sources” on your topic. Instead, think of sources as helping you to answer a research question or a series of research questions about your topic. These should not be simple questions with simple answers, but rather complex questions about which there is no easy or obvious answer.

A compelling research question is one that may involve controversy, or may have a variety of answers, or may not have any single, clear answer. All of that is okay and even desirable. If the answer is an easy and obvious one, then there is little need for argument or research.

Make sure that your research question is clear, specific, researchable, and limited (but not too limited). Most of all, make sure that you are curious about your own research question. If it does not matter to you, researching it will feel incredibly boring and tedious.

The video below includes a deeper explanation of what a good research question is as well as examples of strong research questions:

“Creating a Good Research Question” by CII GSU

A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing by Emilie Zickel is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Feedback/Errata

Comments are closed.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Readings about Rhetorical Foundations

20 Rhetorical Foundations For Research

Jennifer Clary-Lemon; Derek Mueller; and Kate L. Pantelides

Excerpt from Try This: Research Methods For Writers

Uncertainty and Curiosity

Research does not start with a thesis statement. It starts with a question. And though research is recursive , which means that you will move back and forth between various stages in your research and writing process, developing an effective question might in itself be the most important part of the research process. Because there’s really no point in doing a research project if you already know the answer. That is boring. But it is how we are often taught to do research: we decide what we’re going to argue, we look for those things that support that argument, and then we write up the thing that we knew from the outset. If that sounds familiar, we suggest that you scrap that plan.

Instead, we suggest approaching research with an orientation of openness, ready and willing to be surprised, to change your mind. Of course, you never approach research in a vacuum. You probably have ideas about whatever it is that you’re working on. You probably have thoughts about what the answers are to your research questions, and that is as it should be, but that statement of belief should not be where you start.

Try This: Consider Everyday Contexts You Have Engaged in Research (15 minutes)

Take a moment to think about the many occasions when you have gathered information to answer a question outside of an academic context (i.e., What is the most effective deodorant? Where is the best place to eat? What is the fastest route home?). Follow the steps listed:

- First, make a list of some of these everyday questions you have identified and the answers you have come up with in your research.

- Select one that is still interesting to you—one that you may have answered but suspect there are more answers to or one that the answer you identified was only partial.

- Note the method or tool you selected to answer the question.

- Make a list of other methods you might employ to answer your original question.

- Reflect on how identifying alternative research methods might lead you to different answers to your original question, then make a new research plan.

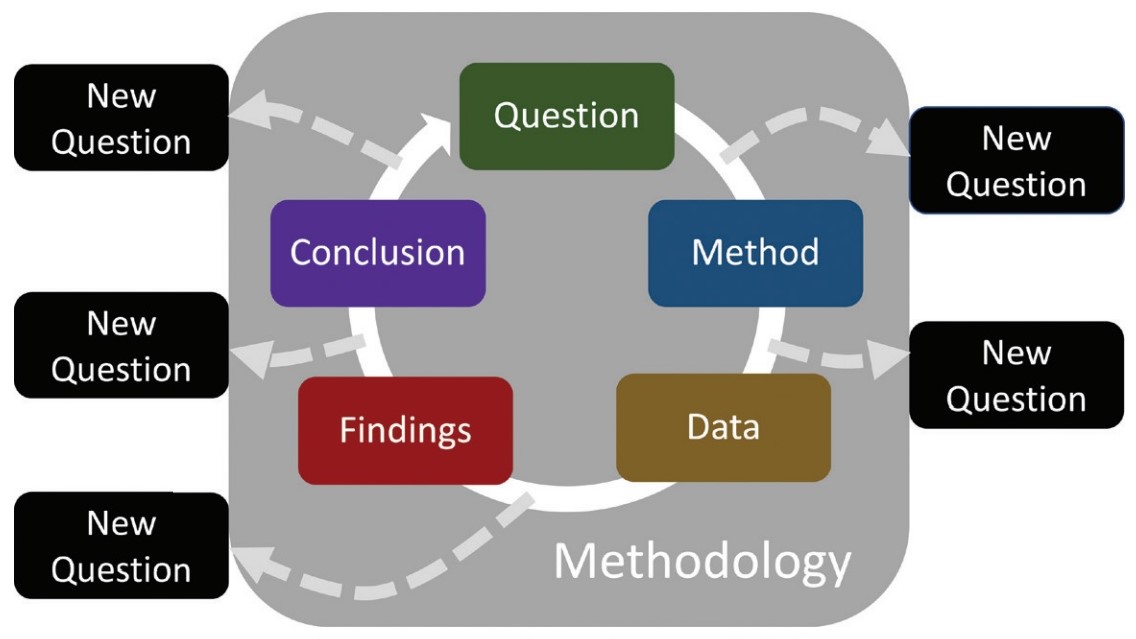

We hope you cultivate an exploratory motive, an orientation of openness, and a willingness to learn. Adopting such a disposition is your work. Get ready to find data that conflicts with what you have come to know about a particular issue. You might even think about your thesis statement as the last thing that you develop in your research project. Let curiosity drive you forward in your work. Research is really only worth engaging in if you learn something from it. We often think about research as knowing, but it’s really about the making of knowledge(s), the movement from not knowing to beginning to know, figuring things out, trying to solve or sort out tricky problems. At the end of an effective research project, we usually have more questions than we started with. Sure, we answer the initial question (if all goes well), but that process of building knowledge usually leads to more questions and helps us recognize what we don’t know. Developing a research orientation includes seeing the world around you as abundant with research opportunities. Harness your curiosity, embrace uncertainty, and begin looking for researchable questions.

Try This: Make a List of Curios (30 minutes)

Reflect on times that you’ve gotten wrapped up in something—when you looked away from the clock and suddenly two hours had passed. What were you doing? Cooking, reading, engaging in a good conversation, playing a game, watching tv, hiking? Identify that experience and consider the following questions:

- What was it that made time fly?

- How might you capture that energy in a research experience?

Now make a curio cabinet of sorts. A curio is a special, mysterious object that inspires curiosity. Cabinets of curiosities were popularized in Europe in the late sixteenth century. They featured items from abroad and unique artifacts from the natural world. Such spaces allowed collectors to assemble and display collections that catalogued their interests and travels and that inspired awe in their reception. Create a curio cabinet for yourself, either by assembling a collection of artifacts that describe your interests, composing an image that represents your curiosities, or developing a textual representation of questions that interest you.

No matter where your research and writing take you—in terms of major, interest, or profession—it’s useful to consistently reflect on what, why, and how you’re conducting research at each step in the process. This attention to thinking about your thinking is called metacognition . This process may sound exhausting, and it can be, especially at first, but being metacognitive about your research will help you transfer your learning into new contexts. Having this orientation toward your research ensures that you have intention in each step you take. The more you practice this approach to research, the easier it gets so that it eventually becomes instinctual.

Rhetorical Foundations of Research

What we have described thus far is a rhetorical approach to the research process. Derived from classical Greek influences, the five ancient canons of rhetoric include invention , arrangement , style , memory , and delivery . In the context of writing and research, these long established, foundational concepts also go by other names, such as pre-writing, organization, mechanics and grammar, process, and circulation of a research product. We want to keep in mind these qualities of effective communication throughout the chapter, but we’ll spend significant time with invention and delivery—canons that we think often get pushed aside or treated as afterthoughts in many approaches to research and research-based writing and that we pay particular attention to in this text.

As you familiarize yourself with an issue and the way scholars have talked about it, take note of the specific ways they talk about the issue and consider why that is. This is how you develop a rhetorical awareness of the ways in which research is constructed. So when you read, read like a researcher: consider both what is said about an issue and how it is said. Identify the rhetorical situation of the piece of writing; this includes the context in which it is written, the audience for whom it is written, and its purpose .

We begin here with a research proposal, but throughout this book we also highlight other research genres that may be more or less familiar to you: literature reviews, coding schemas, annotated maps, research memos, slide decks, and posters. Each time you encounter a new genre, we encourage you to place it in its communicative context: What is the reason to compose this way? What need does it fulfill for its audience? What situation is it most suited to? What communication problem does it solve? We hope that working through research genres in this way will also help you understand your own research process more fully.

Try This: Go on a Scavenger Hunt to Identify Genres in “The Wild” (30 minutes)

With a partner or two, walk around identifying, photographing, documenting, and analyzing genres in your midst. If you’re at a university, you might see posters, signs, and bulletin boards. If you’re at home, you’ll see different genres, and if you’re at a coffee shop, you’ll see yet another set of genres.

Consider this: one genre found in a coffee shop is a menu. It might be on a board, or there may be paper menus that each customer can pick up, but this genre is reliably found in coffee shops throughout the US. Wherever you are, be attentive to the genres that surround you by doing the following:

- Make a list of the genres (the kind of texts) that make up your immediate environment.

- Choose one genre that interests you and consider its rhetorical situation: What is the context in which it is written? Who is its audience? What is the genre’s purpose?

- More broadly, consider the genre’s communicative context: How is this particular example of the genre composed? What communication problem does it solve?

How might such rhetorical knowledge about genre impact your approach to matching research questions to methods and delivery?

Research Example: Student Writing Habits

Let’s use an example to illustrate what happens at the beginning of a research project. Like us, you might be interested in student writing habits. In particular, you might research when (and why) students begin a research project: Do they begin when it is assigned? Two weeks in advance? The night before?

Other researchers have looked at this issue, so you might begin by examining what they have found. These secondary sources , the findings of other thinkers, constitute the critical conversation and might give you ideas for how you might proceed in your own project. Thus, examining this conversation might function as pre-writing , brainstorming , or invention for your research. Rhetorician Kenneth Burke uses the metaphor of a party to describe how critical conversations work: When you arrive at the party, the conversations have been going on for a while, and guests take turns articulating their points of view, sometimes talking over each other, sometimes interrupting, laughing, disagreeing, and agreeing. After listening for a while, you understand the conversation and have something to say, so you chime in, maybe building on what a previous guest has said or contrasting your ideas with a friend’s. Finally, you’re tired and have to head home, but when you do, the sounds of the party are still ringing in your ears, and the conversation will clearly continue.

But if you’re conducting primary research that moves beyond working with sources, the key is to next find out what this particular issue looks like in your local context, or in a specific context in which you’re interested. Most likely, scholars have not examined the issue of when students begin their assignments at your institution, and many factors may impact your context that might make your findings different than what you’ve learned from other scholars. Research methods give researchers recognizable ways to continue the party conversation started by secondary sources.

So the next step is effective research design . You might articulate this plan in a research proposal , further detailed at the end of this chapter. When you are beginning a new research project, the design is expected to be mixed up and messy, because oftentimes you are sorting through many different possibilities. Thus, we encourage you to notice and to write about the messiness of an emerging research design, pausing often to pose the following questions: What are you wondering about now? and, How are these curiosities connecting, drawing your attention to matters you hadn’t considered before? While it’s important to notice these inklings as you go, many effective researchers also write about them as a way to record (to help with memory) and focus. The activity of writing while researching demands patience and persistence, and yet the emerging research design will be magnitudes more refined in later stages as a result.

Design your research project so that your questions, methods, data, findings, and conclusions match up and so that you select or develop primary source data that will be most useful for your particular interest. For instance, if you only have data for about 30 students on campus, you can’t generalize about how all students approach the writing process. If you only know when these students start working on a given writing project, you won’t know why they started at that particular time. This doesn’t mean the information you have isn’t useful; it just means that you need to stay close to your data and only make sense of the information you have. Make note of things you want to know and wish you had more data about so you can develop the project if the opportunity arises.

For this research project on timing in student writing projects, you might develop a survey that asks students when they begin their research project as well as a series of related questions about motivation and timing. If you design a survey that gives students choices to select answers that range from “I begin a project when it is assigned” to “I begin a project the morning that it’s due,” you will develop quantitative data, or representative numbers, that answer your question. If you’re interested in longer, more nuanced answers, you might also provide open-ended questions on your survey, and you’ll develop both quantitative and qualitative data, or non-numeric data not organized according to a specific, numerical pattern.

A survey develops data that might be easily counted and categorized and can be offered to many folks. But you might be interested in more specific, extensive qualitative data than what you can gather through a survey. Your interest might be not just when students start a project, but also why they start at that specific time and if that starting time is a habit or if it depends on what they’re writing about or in which class it is assigned. If these are your interests, it might be more effective to work with people to develop an interview protocol or a case-study approach, methods that would require you to ask fewer people about their study habits but would allow you to develop a deeper understanding of each individual student’s writing habits. One isn’t necessarily better or worse. Like all research methods, each approach provides different data and different opportunities for analysis. It just depends on what you want to know.

Surveys, interviews—these might be methods with which you’re familiar, but there are lots of other useful methods for working with people. You might want to understand student writing processes by looking at all of a particular student’s writing for a given project. Instead of asking the student about her habits and working with reported data, or information that someone has told you, you might use a kind of textual analysis to read all of her notes and drafts for a particular project to better understand not just what she reports about her writing practices but how and what and when she actually writes in the lead up to a due date. Sometimes our perceptions of our actions differ than what we actually do, particularly in regard to writing habits, so collecting data that’s not reported can be helpful. Or you might want to observe that student while she writes to notice how often she takes breaks, if she texts while she writes, or if she listens to music. You might ask her to take pictures of herself or her writing environment at different points during the writing process, and you might develop a comparative visual analysis of the images.

Try This: Plan Your Own Writing Research Project (30 minutes)

What are your research questions about writing? Consider the examples we’ve given and develop your own questions on the topic, then think about possible methods you can use to investigate those questions by doing the following:

- List your interests in and questions about writing and the research process.

- Identify one area of interest on your list and develop it into an effective research question (a question that does not have a yes/no answer, one that requires primary research to answer).

- Consider what methods might be appropriate to help you answer the question you have identified.

Research Example: Access to Clean Water

Here’s an example of how to develop a research plan. Imagine you’re interested in developing a project about water, a topic that has been in the news quite a bit as of late. Depending on your specific interest and the kind of data you are interested in collecting and working with, you can design very different research proposals. The following list will aid you in determining an approach based on where your interest lies:

- If you want to work with sources , maybe you’ll select developing a “worknet” as a research method. Your work with sources would find a focal article to generate a radial diagram as you select and highlight connections. One emerging connection, such as a linkage between long-term health outcomes and access to water filtration systems, can begin to crystalize as a research question that guides you in seeking and finding further sources or in choosing other methods appropriate to pairing with the question.

- If you want to work with words , maybe you’ll select content analysis as a research method to make sense of the discourse you find on your local water treatment plant’s website. You might find that there is specialized or technical language, such as multiple mentions of contamination of which you were not aware, or terms with which you are unfamiliar (e.g., acidity, PPM, or pH). Gathering these terms and beginning to investigate their meanings can serve as the genesis of an emerging research focus.

- If you want to work with people , maybe you’ll select survey as a research method, and you’ll distribute a survey about drinking water to everyone in your classes, perhaps asking questions about their uses of water fountains and bottle refill stations or their knowledge about where their water comes from. You may learn that folks in your community have not had consistent access to potable water.

- If you want to work with places and things , maybe you’ll select site observation as a research method, and you’ll schedule a visit to your local water treatment plant. You may discover upon visiting that the plant is adjacent to a number of factories, or that it is difficult to access, perhaps that there is no one to give you a tour, or that much of the area is off limits. All of these on-site discoveries, carefully chronicled, substantiate distinctive ways of knowing not otherwise available.

- If you want to work with images , maybe you’ll visit a local river, stream, or lake shore and photograph scenes where litter and wildlife are in close proximity, or where signs communicate about expectations for environmental care. A selection of such images may stand as a convincing set of visual evidence and may accompany a simple map identifying locations where you found problems or where additional signage is needed.

The data you work with and the conclusions you can draw are dependent on the research method you select. Each approach provides particular insights into your topic and the world more broadly.

Try This: Brainstorming with Methods (30 minutes)

We’ve illustrated two examples, one focusing on the timing of student writing projects and another focusing on water. Now try this out on your own. Select an interest and work through how each of the methods listed below would generate different data with the potential to draw different kinds of connections.

- Working with sources

- Working with words

- Working with people

- Working with places and things

- Working with images

As you consider an interest in light of each of these research methods, now would also be a good time to revisit the book’s table of contents and then to turn to the chapters themselves to leaf around and begin to see the more specific and nuanced approaches to the methods under each heading.

Research Across the Disciplines

Research conventions , or the expectations about how research is conducted and written about, differ across the disciplines—whether that is theatre, mathematics, criminal justice, anthropology, etc. Some disciplines generally value quantitative data over qualitative data and vice versa. Many disciplines gravitate to certain methods and methodologies and specific patterns of writing up and citing data. Usually these conventions can be rhetorically traced to the values of a particular discipline. For instance, many humanities disciplines (English and World Languages, for instance) favor using MLA style to cite sources, and many social science disciplines (Psychology and Sociology, for instance) generally adhere to APA style. One of the primary differences in these citation styles is that MLA generally privileges author name and page number, which can be traced to the importance of specific wording at the heart of language study. APA privileges author name and year, which can be traced to the ways that social sciences value when something was published.

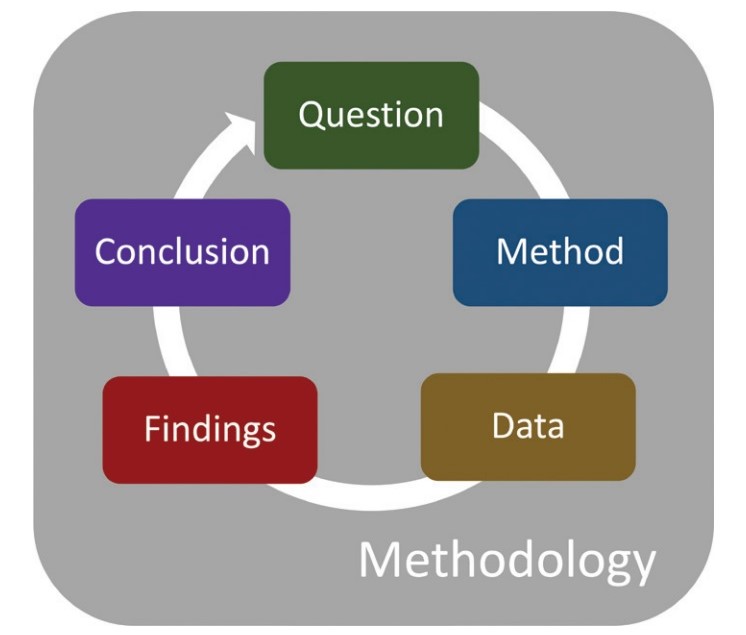

Citation conventions are one of the most concrete, visible differences that distinguish research across disciplines. But the differences are often much deeper and more abstract. How do you decide which method is appropriate for a particular research project? How do you make data meaningful in a particular context? The way you answer these questions constitutes your research methodology , or your thinking about a research project—and methodology, similar to citation style, usually demonstrates disciplinary values. Whether or not you state your methodology, everyone has a way of thinking about the method they choose and how the data they are using matters. Articulating a methodology simply makes that approach transparent to your audience and clear to yourself. Thus, a research methodology is the approach to a method, or the understanding and thinking that organizes a particular method, as we show in Figure 1.1. Returning again to the etymology of “method” noted earlier (meta- and -hodos), consider the new part of the term, -ology. This addition assigns to method its reason for being selected. Accounting explicitly for the rationale, motives, and appropriateness of a research design, a methodology answers to justifications, underlying values, and established traditions for how knowledge is made and what kinds of knowledge matters in a given discipline.

For example, if you survey 100 people at your university about the timing of their writing projects, and you develop quantitative data as a result of your survey, you present that data as meaningful and suggest that such numbers provide a useful window into understanding student writing. However, you might not agree with this approach. You might think that to really understand student writing, you need to talk to students and ask open-ended questions. Or, you might believe that reported data about writing behaviors is not meaningful because we know that what people say they do and what they actually do are often very different things. You may believe that we need mixed methods to most effectively provide a portrait of student writing on campus, so you might design your study such that you incorporate both survey and interview data. Ultimately the kind of data that methodology values is related to disciplinary values, and as you select a research project, a professional focus, and a profession, you will inherit disciplinary values. For example, researchers in the humanities might especially value qualitative data, and researchers in STEM fields might especially value quantitative data. As you become a more ingrained member of a disciplinary community (for instance when the major or job you take starts to feel familiar) we encourage you to keep questioning the methodology and values you inherit.

In Figure 2, we show how developing more questions along the way in all parts of your research design may give way to more complexity in your project.

Critical conversations about research are both normative, in that they usually bring together many scholars’ thinking about a particular issue, and disruptive, in that new findings can up-end a particular conversation. Much of these changes are attributable to developments in methodology, such as updates in how we value a particular method or how we interpret certain findings. Changes to methodologies often cause significant ruptures in research communities. We are familiar with some of these large ruptures: the earth revolves around the sun instead of the reverse, bleeding a patient does not make her healthier, students learn most effectively through practice rather than listening by rote, etc. It is not always easy to come across findings that cause a rupture; however, as you examine the evolution of critical conversations over time, you might notice that they change slowly as new ruptures slowly become accepted in their associated communities.

Using Research Methods Ethically

The decisions you make in developing an effective research question, matching it to an appropriate research method, and then responsibly analyzing the implications of your findings (research design), are especially important because research is subjective . Subjectivity is often seen as negative and is frequently leveled as a reason to mistrust a decision or judgment, as in, “You’re just being subjective.” But: all research is subjective, all research is communication. Of course, not all scholars and fields believe this, but let us try to convince you, because it is important. This belief is central to conducting ethical research.

There is no pure objectivity when it comes to research. Research is conducted by people, all of whom have different ideas about effective research, but researchers abide by a code of ethics that holds them to standards that help them maintain safety and develop meaningful research. Even quantitative research, even computer algorithms that identify trends—all of the methods associated with developing this data are engineered by people and are, thus, subjective. And this is a good thing!

Instead of striving for objective research (an impossibility), we strive for ethical research. Ethical research takes into account the fact that people perform research and that their research designs are impacted by their own subjectivities : the thoughts, beliefs, and values that make us human. As researchers, it is essential to be reflective on our subjectivities, mitigate subjectivities that might make us conduct research unfairly, and adhere to high ethical standards for research.

move back and forth between various stages of a process, as both those engaging in a research process or a writing process do

awareness and understanding of one's own thought processes

the act of bringing knowledge or skills from one context to another; the goal of a first-year writing course is to transfer the writing skills developed in the class to other writing situations

a determination to act in a certain way; the product of attention directed to an object of knowledge

an approach that examines texts primarily as acts of communication or as performances rather than as static objects; the study of both production and reception of discourse

Invention - the finding out or selection of topics to be treated, or arguments to be used; often referred to as the brainstorming or prewriting stage of the writing process, though invention takes place across the writing process

Arrangement - the action of arranging or disposing in order; often referred to as the organization state of the writing process, though arrangement takes place across the writing process and can be both an aesthetic and an argumentative consideration

Style - the associated genre conventions with which an author chooses to compose; these conventions include tone, level of formality, choice of register, punctuation, and grammar and syntactical concerns

Memory - The perpetuated knowledge or recollection (of something); that which is remembered of a person, object, or event; (good or bad) posthumous reputation; the capacity for retaining, perpetuating, or reviving the thought of things past; the faculty by which things are remembered considered as residing in the awareness or consciousness of a particular individual or group

Delivery - how the compositions we develop reach the audience; in classical Greco-Roman rhetorical tradition, it was primarily concerned with speakers who in real-time stood before reasonably attentive audiences to speak persuasively about matters of civic concern; in modern tradition it is associated with genre, medium, circulation, and ecologies

the finding out or selection of topics to be treated, or arguments to be used; often referred to as the brainstorming or prewriting stage of the writing process, though invention takes place across the writing process

the action of arranging or disposing in order; often referred to as the organization state of the writing process, though arrangement takes place across the writing process and can be both an aesthetic and an argumentative consideration

the associated genre conventions with which an author chooses to compose; these conventions include tone, level of formality, choice of register, punctuation, and grammar and syntactical concerns

the perpetuated knowledge or recollection (of something); that which is remembered of a person, object, or event; (good or bad) posthumous reputation; the capacity for retaining, perpetuating, or reviving the thought of things past; the faculty by which things are remembered considered as residing in the awareness or consciousness of a particular individual or group

how the compositions we develop reach the audience; in classical Greco-Roman rhetorical tradition, it was primarily concerned with speakers who in real-time stood before reasonably attentive audiences to speak persuasively about matters of civic concern; in modern tradition it is associated with genre, medium, circulation, and ecologies

(also known as rhetorical situation) the context or set of circumstances out of which a text arises (author/speaker, audience, purpose, setting, text/speech)

a component of the rhetorical situation; any person or group who is the intended recipient of a message conveyed through text, speech, audio; the person/people the author is trying to influence

the author’s motivations for creating the text

sources that summarize, interpret, critique, analyze, or offer commentary on primary sources; in a secondary source, an author’s subject is not necessarily something that he/she/they directly experienced

the first stage of the writing process that include a combination of outlining, diagramming, storyboarding, and clustering; a way to record thoughts about a topic before trying to draft an organized text

the state at which a writer/author engages in generating ideas, exploring those ideas, and developing what will become the topic, thesis, and, ultimately, essay

information that has not yet been critiqued, interpreted or analyzed by a second (or third, etc) party; information gathered through first-hand or personal experience or study

the overall strategy that chosen for the intergradation of different components of a study in a coherent and logical way

a detailed plan or 'blueprint' for the intended study and approach to design

texts that arise directly from a particular event or time period; any content that comes out of direct involvement with an event or a research study

methods that collect and generate numerical or countable data

methods that collect observable or discursive data, which may include opinions or experiences and which generate non-numerical data

an instrument of inquiry—asking questions for specific information related to the aims of a study (Patton, 2015) as well as an instrument for conversation about a particular topic (i.e., someone's life or certain ideas and experiences)

a process or record of research in which detailed consideration is given to the development of a particular person, group, or situation over a period of time; a particular instance of something used or analyzed in order to illustrate a thesis or principle

the careful study of a text/speech where the context, audience, and purpose for discourse are considered; the process that helps demonstrate the significance of a text by carefully considering the rhetorical situation in which it develops and the ways that it supports its purpose

notice or perceive (something) and register it as being significant

a method of understanding that focuses on visual elements, such as color, line, texture, and scale

broadly refers to tools for collecting data; research methods may be qualitative, methods that collect discursive data that cannot be counted; quantitative, methods that collect numeric or countable data; and mixed, methods that draw on both quantitative and qualitative measures

influenced by or based on personal beliefs or feelings, rather than based on facts

impartial, detached approach

considerations of research design that weigh the potential outcome of the findings alongside the process of ascertaining those findings; ethical research includes (1) Respect for Persons (autonomy), which acknowledges the dignity and freedom of every person; (2) Beneficence, which requires that researchers maximize benefits and minimize harms or risks associated with research; and (3) Justice, which requires the equitable selection and recruitment and fair treatment of research subjects

existing in the mind; belonging to the thinking subject rather than to the object of thought

Rhetorical Foundations For Research Copyright © 2021 by Jennifer Clary-Lemon; Derek Mueller; and Kate L. Pantelides is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Chapter Six: Critical / Rhetorical Methods (Part 1)

Researchers use critical/rhetorical methods to ask questions about how a particular symbolic action constructs social reality. The questions posed by rhetorical criticism are as varied as the messages analyzed. Although a research question may not be stated explicitly, the central argument advanced by the research is. Unlike quantitative and qualitative research methods, there are no specific pre-defined step-by-step procedures in critical/rhetorical methods that can be replicated.

Researchers use critical/rhetorical methods when they want to understand and analyze what an act of communication does. Learning methods of rhetorical criticism enables you to critique communicators' use of verbal and nonverbal symbols in a specific context so that you can understand how communication constructs a specific understanding of the world. The more adept you become at analyzing others' messages, the more skilled you become at constructing your own. In the end, the quality of a critical/rhetorical study depends on the quality of the argument the researcher presents.

In Part I of this chapter, we explain of the importance of symbolic action to the critical/rhetorical approach and describe key concepts central to doing critical/rhetorical research. In Part II, we provide specific direction on how to do critical/rhetorical research, charting a path for you regarding how critical/rhetorical work can be accomplished.

- Chapter One: Introduction

- Chapter Two: Understanding the distinctions among research methods

- Chapter Three: Ethical research, writing, and creative work

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 2 - Doing Your Study)

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 3 - Making Sense of Your Study)

- Chapter Five: Qualitative Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Five: Qualitative Data (Part 2)

- Chapter Six: Critical / Rhetorical Methods (Part 2)

- Chapter Seven: Presenting Your Results

Rhetoric is Symbolic Action

Rhetoric is the use of symbolic action by human beings to work together to make decisions about matters of common concern and to construct social reality . For communication studies scholars, rhetoric is the means by which people make meaning of, and affect, the world in which they live. Central to this definition is the concept of symbolic action , which is a little more complex than might first appear. So, we will unpack it, defining symbolic , then defining action , and then providing an few example of symbolic action.