- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.3: Motivational Factors for Research

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 42878

- Scott T. Paynton & Laura K. Hahn with Humboldt State University Students

- Humboldt State University

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

We think it is important to discuss the fact that human nature influences all research. While some researchers might argue that their research is objective, realistically, no research is totally objective. What does this mean? Researchers have to make choices about what to research, how they will conduct their research, who will pay for their research, and how they will present their research conclusions to others. These choices are influenced by the motives and material resources of researchers. The most obvious case of this in the physical sciences is research sponsored by the tobacco industry that downplays the health hazards associated with smoking (Frisbee & Donley). Intuitively, we know that certain motivations influence this line of research as it is an example of an extreme case of motivational factors influencing research. Realistically though, all researchers are motivated by certain factors that influence their research.

We will highlight three factors that motivate the choices we make when conducting communication research: 1) The intended outcomes, 2) theoretical preferences, and 3) methodological preferences.

Intended Outcomes

One question researchers ask while doing their research project is, “What do I want to accomplish with this research?” Three primary research goals are to increase understanding of a behavior or phenomenon, predict behavior, or create social change.

Case In Point

The evolution of anti-drug commercials.

In 1987 an anti-drug campaign, Your Brain on Drugs began to air on television. Wikipedia writes, “The first PSA, from 1987, showed a man who held up an egg and said, “This is your brain,” before picking up a frying pan and adding, “This is drugs.” He then cracks open the egg, fries the contents, and says, “This is your brain on drugs.” Finally he looks up at the camera and asks, “Any questions?”

After careful examination, researchers quickly discovered that this ad campaign was not effective, as it actually made the frying of an egg appealing, especially to those people who were watching the ad that were hungry! Thus, in 1998, they revised the PSA to make it more dramatic.

Scholars who study health campaigns are interested in finding the most effective ways to help get accurate health information to people so they can act on that information.

Here are some anti-marijuana advertisements the millennial generation may be familiar with:

There is this anti-marijuana commercial that tries to bring about the fears of smoking marijuana. Seth Stevenson states the commercial brings out two fears: “1) the fear that nonsmoker friends, or lovers, might find them tiresome and pathetic, and 2) the fear that they might be growing dependent on the drug.”

The same can be said for this video. In the video a pet dog tells what looks to be its teenage owner to quit smoking weed. This is supposed to evoke guilt upon the owner and carry out to the viewer. Both campaigns “effectively [pick] at both of these insecurities” that anti-drug campaigns attempt to associate with smoking week.

Do you find any of these effective? Why or why not? Think of anti-drug campaigns that would be effective for teens/young adults today.

A great deal of Communication research seeks understanding as the intended outcome of the research. As we gain greater understanding of human communication we are able to develop more sophisticated theories to help us understand how and why people communicate. One example might be research investigates the communication of registered nurses to understand how they use language to define and enact their professional responsibilities. Research has discovered that nurses routinely refer to themselves as “patient advocates” and state that their profession is unique, valuable, and distinct from being an assistant to physicians. Having this understanding can be useful for enacting change by educating physicians and nurses about the impacts of their language choices in health care.

A second intended outcome of Communication research is prediction and control . Ideas of prediction and control are taken from the physical sciences (remember our discussion of Empirical Laws theories in the last chapter?). Many Communication researchers want to use the results of their research to predict and control communication in certain contexts. This type of research can help us make communicative choices from an informed perspective. In fact, when you communicate, you often do so with the intention of prediction and control. Imagine walking on campus and seeing someone you would like to ask out. Because of your past experiences, you predict that if you say certain things to them in a certain way, you might have a greater likelihood that they will respond positively. Your predictions guide your behaviors in order to control the exchange at some level. This same idea motivates many Communication researchers to approach their research with the intention of being able to predict and control communication contexts. For example, in the article The Fear of Public Speaking , Sian Beilock, Ph.D explains prediction and control in action.

A third intended outcome of Communication research is positive critical/cultural change in the world. Scholars often perform research in order to challenge communicative norms and effect cultural and societal change. Research that examines health communication campaigns, for example, seeks to understand how effective campaigns are in changing our health behaviors such as using condoms to prevent sexually transmitted diseases or avoiding high fat foods. When it is determined that health campaigns are ineffective, researchers often suggest changes to health communication campaigns to increase their efficacy in reaching the people who need access to the information (Stephenson & Southwell).

As humans, researchers have particular goals in mind. Having an understanding of what they want to accomplish with their research helps them formulate questions and develop appropriate methodologies for conducting research that will help them achieve their intended outcomes.

Theoretical Preferences

Remember that theoretical paradigms offer different ways to understand communication. While it is possible to examine communication from multiple theoretical perspectives, it has been our experience that our colleagues tend to favor certain theoretical paradigms over others. Put another way, we all understand the world in ways that make sense to us.

Which theoretical paradigm(s) do you most align yourself with? How would this influence what you would want to accomplish if you were researching human communication? What types of communication phenomena grab your attention? Why? These are questions that researchers wrestle with as they put together their research projects.

Methodological Preferences

As you’ve learned, the actual process of doing research is called the methodology . While most researchers have preferences for certain theoretical paradigms, most researchers also have preferred methodologies for conducting research in which they develop increased expertise throughout their careers. As with theories, there are a large number of methodologies available for conducting research. As we did with theories, we believe it is easier for you to understand methodologies by categorizing them into paradigms. Most Communication researchers have a preference for one research paradigm over the others. For our purposes, we have divided methodological paradigms into 1) rhetorical methodologies, 2) quantitative methodologies, and 3) qualitative methodologies.

Contributions and Affiliations

- Survey of Communication Study. Authored by : Scott T Paynton and Linda K Hahn. Provided by : Humboldt State University. Located at : https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Survey_of_Communication_Study/Preface . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Motivation: Introduction to the Theory, Concepts, and Research

- First Online: 03 May 2018

Cite this chapter

- Paulina Arango 4

Part of the book series: Literacy Studies ((LITS,volume 15))

1735 Accesses

2 Citations

Motivation is a psychological construct that refers to the disposition to act and direct behavior according to a goal. Like most of psychological processes, motivation develops throughout the life span and is influenced by both biological and environmental factors. The aim of this chapter is to summarize research on the development of motivation from infancy to adolescence, which can help understand the typical developmental trajectories of this ability and its relation to learning. We will start with a review of some of the most influential theories of motivation and the aspects each of them has emphasized. We will also explore how biology and experience interact in this development, paying special attention to factors such as: school, family, and peers, as well as characteristics of the child including self-esteem, cognitive development, and temperament. Finally, we will discuss the implications of understanding the developmental trajectories and the factors that have an impact on this development, for both teachers and parents.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

This is not intended to be an exhaustive review of motivational theories. For a more detailed review see: (Dörnyei and Ushioda 2013 ; Eccles and Wigfield 2002 ; Wentzel and Miele 2009 ; Wigfield et al. 2007 ).

For more information on the development of motivation in adults you can see: Carstensen 1993 ; Kanfer and Ackerman 2004 ; Wlodkowski 2011 .

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64 (6), 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0043445 .

Article Google Scholar

Atkinson, J. W., & Raynor, J. O. (1978). Personality, motivation, and achievement . Oxford: Hemisphere.

Google Scholar

Aunola, K., Leskinen, E., Onatsu-Arvilommi, T., & Nurmi, J. E. (2002). Three methods for studying developmental change: A case of reading skills and self-concept. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72 (3), 343–364. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709902320634447 .

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory . Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1991). Self-regulation of motivation through anticipatory and self-reactive mechanisms. In R. A. Dienstbier (Ed.), Perspectives on motivation: Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 38, pp. 69–164). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control . New York: Freeman.

Bandura, A. (1999). A social cognitive theory of personality. In L. Pervin & O. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality (2nd ed., pp. 154–196). New York: Guilford.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (2001). Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of children’s aspirations and career trajectories. Child Development, 72 (1), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00273 .

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. R. (2000). Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex, 10 (3), 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/10.3.295 .

Boulton, M. J., Don, J., & Boulton, L. (2011). Predicting children’s liking of school from their peer relationships. Social Psychology of Education, 14 (4), 489–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-011-9156-0 .

Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53 (1), 371–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233 .

Brechwald, W. A., & Prinstein, M. J. (2011). Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21 (1), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x .

Buss, D. M. (2008). Human nature and individual differences. In S. E. Hampson & H. S. Friedman (Eds.), The handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 29–60). New York: The Guilford Press.

Cain, K. M., & Dweck, C. S. (1989). The development of children’s conceptions of Intelligence; A theoretical framework. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Advances in the psychology of human intelligence (Vol. 5, pp. 47–82). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Cain, K., & Dweck, C. S. (1995). The relation between motivational patterns and achievement cognitions through the elementary school years. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 41 (1), 25–52.

Carlson, C. L., Mann, M., & Alexander, D. K. (2000). Effects of reward and response cost on the performance and motivation of children with ADHD. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24 (1), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005455009154 .

Carstensen, L. L. (1993, January). Motivation for social contact across the life span: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. In Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 40, pp. 209–254).

Catalano, R. F., Berglund, M. L., Ryan, J. A., Lonczak, H. S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2004). Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591 (1), 98–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716203260102 .

Coll, C. G., Bearer, E. L., & Lerner, R. M. (2014). Nature and nurture: The complex interplay of genetic and environmental influences on human behavior and development . Mahwah: Psychology Press.

Collins, W. A., Maccoby, E. E., Steinberg, L., Hetherington, E. M., & Bornstein, M. H. (2000). Contemporary research on parenting: The case for nature and nurture. American Psychologist, 55 (2), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003–066X.55.2.218 .

Conger, R. D., Wallace, L. E., Sun, Y., Simons, R. L., McLoyd, V. C., & Brody, G. H. (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38 (2), 179. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012–1649.38.2.179 .

Connell, J. P. (1985). A new multidimensional measure of children’s perception of control. Child Development, 56 (4), 1018–1041. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130113 .

Damasio, A. R., Everitt, B. J., & Bishop, D. (1996). The somatic marker hypothesis and the possible functions of the prefrontal cortex [and discussion]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 351 (1346), 1413–1420. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1996.0125 .

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self–determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11 (4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01 .

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002a). The paradox of achievement: The harder you push, the worse it gets. In J. Aronson (Ed.), Improving academic achievement: Impact of psychological factors on education (pp. 61–87). San Diego: Academic Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002b). Self–determination research: Reflections and future directions. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self–determination theory research (pp. 431–441). Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2013). Teaching and researching: Motivation . London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833750 .

Book Google Scholar

Dweck, C. S. (2002). The development of ability conceptions. In A. Wigfield & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Development of achievement motivation (pp. 57–88). San Diego: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978–012750053–9/50005–X .

Eccles, J. S. (1987). Gender roles and women’s achievement–related decisions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 11 (2), 135–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471–6402.1987.tb00781.x .

Eccles, J. S. (1993). School and family effects on the ontogeny of children’s interests, self–perceptions, and activity choice. In J. Jacobs (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation, 1992: Developmental perspectives on motivation (pp. 145–208). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Eccles, J. S., & Harold, R. D. (1993). Parent–school involvement during the early adolescent years. Teachers’ College Record, 94 , 568–587.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (1995). In the mind of the actor: The structure of adolescents’ achievement task values and expectancy–related beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21 (3), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295213003 .

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53 (1), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153 .

Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., Harold, R., & Blumenfeld, P. B. (1993). Age and gender differences in children’s self– And task perceptions during elementary school. Child Development, 64 (3), 830–847. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467–8624.1993.tb02946.x .

Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., & Schiefele, U. (1998). Motivation to succeed. In W. Damon (Series Ed.) & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of Child Psychology (5th ed. Vol. 3, pp. 1017–1095). New York: Wiley.

Eccles–Parsons, J., Adler, T. F., & Kaczala, C. M. (1982). Socialization of achievement attitudes and beliefs: Parental influences. Child Development, 53 (2), 310–321. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128973 .

Eccles–Parsons, J., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J. L., et al. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motivation (pp. 75–146). San Francisco: Freeman.

Eggen, P. D., & Kauchak, D. P. (2007). Educational psychology: Windows on classrooms . Virginia: Prentice Hall.

Ernst, M. (2014). The triadic model perspective for the study of adolescent motivated behavior. Brain and Cognition, 89 , 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2014.01.006 .

Ernst, M., & Fudge, J. L. (2009). A developmental neurobiological model of motivated behavior: Anatomy, connectivity and ontogeny of the triadic nodes. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 33 (3), 367–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.10.009 .

Ernst, M., & Paulus, M. P. (2005). Neurobiology of decision making: A selective review from a neurocognitive and clinical perspective. Biological Psychiatry, 58 (8), 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.004 .

Ernst, M., Pine, D. S., & Hardin, M. (2006). Triadic model of the neurobiology of motivated behavior in adolescence. Psychological Medicine, 36 (03), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291705005891 .

Ernst, M., Romeo, R. D., & Andersen, S. L. (2009). Neurobiology of the development of motivated behaviors in adolescence: A window into a neural systems model. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 93 (3), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2008.12.013 .

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2002). Children’s competence and value beliefs from childhood through adolescence: Growth trajectories in two male–sex–typed domains. Developmental Psychology, 38 (4), 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012–1649.38.4.519 .

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2004). Parental influences on youth involvement in sports. In M. R. Weiss (Ed.), Developmental sport and exercise psychology: A lifespan perspective (pp. 145–164). Morgantown: Fitness Information Technology.

Freud, S. (1920). Beyond the pleasure principle . London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis.

Friedel, J. M., Cortina, K. S., Turner, J. C., & Midgley, C. (2007). Achievement goals, efficacy beliefs and coping strategies in mathematics: The roles of perceived parent and teacher goal emphases. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 32 (3), 434–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2006.10.009 .

Furrer, C., & Skinner, E. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95 (1), 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022–0663.95.1.148 .

Gallardo, L. O., Barrasa, A., & Guevara–Viejo, F. (2016). Positive peer relationships and academic achievement across early and midadolescence. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 44 (10), 1637–1648. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.10.1637 .

Glenn, S., Dayus, B., Cunningham, C., & Horgan, M. (2001). Mastery motivation in children with down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice, 7 (2), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.3104/reports.114 .

Gniewosz, B., Eccles, J. S., & Noack, P. (2015). Early adolescents’ development of academic self-concept and intrinsic task value: The role of contextual feedback. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 25 (3), 459–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12140 .

Gunderson, E. A., Ramirez, G., Levine, S. C., & Beilock, S. L. (2012). The role of parents and teachers in the development of gender–related math attitudes. Sex Roles, 66 (3–4), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9996-2 .

Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., & Perencevich, K. C. (Eds.). (2004). Motivating reading comprehension: Concept oriented reading instruction . Mahwah: Erlbaum. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410610126 .

Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., & Elliot, A. J. (1998). Rethinking achievement goals: When are they adaptive for college students and why? Educational Psychologist, 33 (1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3301_1 .

Heckhausen, H. (1987). Emotional components of action: Their ontogeny as reflected in achievement behavior. In D. Gîrlitz & J. F. Wohlwill (Eds.), Curiosity, imagination, and play (pp. 326–348). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Heckhausen, J. (2000). Motivational psychology of human development: Developing motivation and motivating development . Amsterdam: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4115(00)80003-5 .

Hokoda, A., & Fincham, F. D. (1995). Origins of children’s helpless and mastery achievement patterns in the family. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87 (3), 375–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.87.3.375 .

Hull, C. L. (1943). Principles of behavior: An introduction to behavior theory . Oxford: Appleton-Century Company, Incorporated.

Jacobs, J. E., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Parents, task values, and real-life achievement-related choices. In C. Sansone & J. M. Harackiewicz (Eds.), Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The search for optimal motivation and performance (pp. 405–439). San Diego: Academic Press.

Jacobs, J. E., Lanza, S., Osgood, D. W., Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Changes in children’s self-competence and values: Gender and domain differences across grades one through twelve. Child Development, 73 (2), 509–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00421 .

Jacobs, J. E., Davis-Kean, P., Bleeker, M., Eccles, J. S., & Malanchuk, O. (2005). I can, but I don’t want to. The impact of parents, interests, and activities on gender differences in math. In A. Gallagher & J. Kaufman (Eds.), Gender differences in mathematics: An integrative psychological approach (pp. 246–263). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

James, W. (1963). Psychology . New York: Fawcett.

Kahne, J., Nagaoka, J., Brown, A., O’Brien, J., Quinn, T., & Thiede, K. (2001). Assessing after-school programs as contexts for youth development. Youth & Society, 32 (4), 421–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X01032004002 .

Kanfer, R., & Ackerman, P. L. (2004). Aging, adult development, and work motivation. Academy of Management Review, 29 (3), 440–458. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2004.13670969 .

Karbach, J., Gottschling, J., Spengler, M., Hegewald, K., & Spinath, F. M. (2013). Parental involvement and general cognitive ability as predictors of domain-specific academic achievement in early adolescence. Learning and Instruction, 23 , 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.09.004 .

King, R. B., & Ganotice, F. A., Jr. (2014). The social underpinnings of motivation and achievement: Investigating the role of parents, teachers, and peers on academic outcomes. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 23 (3), 745–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0148-z .

Kleinginna, P. R., Jr., & Kleinginna, A. M. (1981). A categorized list of motivation definitions, with a suggestion for a consensual definition. Motivation and Emotion, 5 (3), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00993889 .

Lee, J., & Shute, V. J. (2010). Personal and social-contextual factors in K–12 academic performance: An integrative perspective on student learning. Educational Psychologist, 45 (3), 185–202. 1080/00461520.2010.493471 .

Lee, V. E., & Smith, J. (2001). Restructuring high schools for equity and excellence: What works . New York: Teachers College Press.

Linnenbrink, E. A. (2005). The dilemma of performance-approach goals: The use of multiple goal contexts to promote students’ motivation and learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97 (2), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.197 .

Logan, M., & Skamp, K. (2008). Engaging students in science across the primary secondary interface: Listening to the students’ voice. Research in Science Education, 38 (4), 501–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-007-9063-8 .

Mantzicopoulos, P., French, B. F., & Maller, S. J. (2004). Factor structure of the pictorial scale of perceived competence and social acceptance with two pre-elementary samples. Child Development, 75 (4), 1214–1228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00734.x .

Marjoribanks, K. (2002). Family and school capital: Towards a context theory of students’ school outcomes . Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-9980-1 .

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50 (4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346 .

McDougal, W. (1908). An introduction to social psychology . Boston: John W. Luce and Co..

McInerney, D. M. (2008). Personal investment, culture and learning: Insights into school achievement across Anglo, aboriginal, Asian and Lebanese students in Australia. International Journal of Psychology, 43 (5), 870–879. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590701836364 .

Midgley, C. (Ed.). (2014). Goals, goal structures, and patterns of adaptive learning . Abingdon: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410602152 .

Murdock, T. B., Hale, N. M., & Weber, M. J. (2001). Predictors of cheating among early adolescents: Academic and social motivations. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 26 (1), 96–115. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.2000.1046 .

National Research Council. (2004). Engaging schools: Fostering high school students’ motivation to learn . Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.42–1079 .

Nelson, R. M., & DeBacker, T. K. (2008). Achievement motivation in adolescents: The role of peer climate and best friends. The Journal of Experimental Education, 76 (2), 170–189. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.76.2.170-190 .

Niccols, A., Atkinson, L., & Pepler, D. (2003). Mastery motivation in young children with Down’s syndrome: Relations with cognitive and adaptive competence. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47 (2), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00452.x .

Nicholls, J. G. (1979). Development of perception of own attainment and causal attributions for success and failure in reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 71 (1), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.71.1.94 .

Nicholls, J. G., & Miller, A. T. (1984). The differentiation of the concepts of difficulty and ability. Child Development, 54 (4), 951–959. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129899 .

Patrick, H., Anderman, L. H., Ryan, A. M., Edelin, K. C., & Midgley, C. (2001). Teachers’ communication of goal orientations in four fifth-grade classrooms. The Elementary School Journal, 102 (1), 35–58. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1002168 .

Pavlov, I. P. (2003). Conditioned reflexes . Mineola: Courier Corporation.

Pesu, L. A., Aunola, K., Viljaranta, J., & Nurmi, J. E. (2016a). The development of adolescents’ self-concept of ability through grades 7–9 and the role of parental beliefs. Frontline Learning Research, 4 (3), 92–109. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v4i3.249 .

Pesu, L., Viljaranta, J., & Aunola, K. (2016b). The role of parents’ and teachers’ beliefs in children’s self-concept development. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 44 , 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.03.001 .

Petri, H. L., & Govern, J. M. (2012). Motivation: Theory, research, and application . Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing.

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). Multiple goals, multiple pathways: The role of goal orientation in learning and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92 (3), 544–555. 10.I037//0022-O663.92.3.544 .

Pintrich, P. R. (2003). A motivational science perspective on the role of student motivation in learning and teaching contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95 (4), 667. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.4.667 .

Pintrich, P. R., & Maehr, M. L. (2004). Advances in motivation and achievement: Motivating students, improving schools (Vol. 13). Bingley: Emerald Grup Publishing Limited.

Ratelle, C. F., Guay, F., Larose, S., & Senécal, C. (2004). Family correlates of trajectories of academic motivation during a school transition: A semiparametric group-based approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96 (4), 743. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.4.743 .

Roeser, R. W., Eccles, J. S., & Sameroff, A. J. (1998). Academic and emotional functioning in early adolescence: Longitudinal relations, patterns, and prediction by experience in middle school. Development and Psychopathology, 10 (02), 321–352.

Roeser, R. W., Marachi, R., & Gelhbach, H. (2002). A goal theory perspective on teachers’ professional identities and the contexts of teaching. In C. M. Midgley (Ed.), Goals, goal structures, and patterns of adaptive learning (pp. 205–241). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80 (1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976 .

Ryan, A. M. (2001). The peer group as a context for the development of young adolescents’ motivation and achievement. Child Development, 72 (4), 1135–1150. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00338 .

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). An overview of self-determination theory: An organismic-dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination theory research (pp. 3–33). Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Schunk, D. H., & Pajares, F. (2002). The development of academic self-efficacy. In A. Wigfield & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Development of achievement motivation (pp. 15–32). San Diego: Academic Press.

Schunk, D. H., Meece, J. R., & Pintrich, P. R. (2012). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications . Harlow: Pearson Higher Ed.

Shell, D. F., Colvin, C., & Bruning, R. H. (1995). Self-efficacy, attribution, and outcome expectancy mechanisms in reading and writing achievement: Grade-level and achievement-level differences. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87 (3), 386–398. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.87.3.386 .

Shin, H., & Ryan, A. M. (2014). Friendship networks and achievement goals: An examination of selection and influence processes and variations by gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43 (9), 1453–1464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0132-9 .

Simpkins, S. D., Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Charting the Eccles’ expectancy-value model from mothers’ beliefs in childhood to youths’ activities in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 48 (4), 1019–1032. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027468 .

Simpson, R. D., & Oliver, J. (1990). A summary of major influences on attitude toward and achievement in science among adolescent students. Science Education, 74 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.3730740102 .

Sjaastad, J. (2012). Sources of inspiration: The role of significant persons in young people’s choice of science in higher education. International Journal of Science Education, 34 (10), 1615–1636. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2011.590543 .

Skinner, B. F. (1963). Operant behavior. American Psychologist, 18 (8), 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045185 .

Skinner, E. A. (1995). Perceived control, motivation, and coping . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Skinner, E. A., Chapman, M., & Baltes, P. B. (1988). Control, meansends, and agency beliefs: A new conceptualization and its measurement during childhood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54 (1), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.117 .

Skinner, E. A., Gembeck-Zimmer, M. J., & Connell, J. P. (1998). Individual differences and the development of perceived control. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 6 (2/3. Serial No. 254), 1–220.

Stipek, D., Recchia, S., McClintic, S., & Lewis, M. (1992). Self-evaluation in young children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development , 57 (1. Serial No. 226) 1–97.

Swarat, S., Ortony, A., & Revelle, W. (2012). Activity matters: Understanding student interest in school science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 49 (4), 515–537. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21010 .

Tenenbaum, H. R., & Leaper, C. (2003). Parent-child conversations about science: The socialization of gender inequities? Developmental Psychology, 39 (1), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.39.1.34 .

Thorndike, E. L. (1927). The law of effect. The American Journal of Psychology, 39 (1/4), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/141541310.2307/1415413 .

Ushioda, E. (2007). Motivation, autonomy and sociocultural theory. In P. Benson (Ed.), Learner autonomy 8: Teacher and learner perspectives (pp. 5–24). Dublin: Authentik.

Vallerand, R. J. (1997). Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 29 , 271–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60019-2 .

Vedder-Weiss, D., & Fortus, D. (2013). School, teacher, peers, and parents’ goals emphases and adolescents’ motivation to learn science in and out of school. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 50 (8), 952–988. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21103 .

Véronneau, M. H., Vitaro, F., Brendgen, M., Dishion, T. J., & Tremblay, R. E. (2010). Transactional analysis of the reciprocal links between peer experiences and academic achievement from middle childhood to early adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 46 (4), 773. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019816 .

Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Newcorn, J. H., Kollins, S. H., Wigal, T. L., Telang, F., & Wong, C. (2011). Motivation deficit in ADHD is associated with dysfunction of the dopamine reward pathway. Molecular Psychiatry, 16 (11), 1147–1154. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2010.97 .

Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Social support matters: Longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Development, 83 (3), 877–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01745.x .

Wang, M. T., & Sheikh-Khalil, S. (2014). Does parental involvement matter for student achievement and mental health in high school? Child Development, 85 (2), 610–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12153 .

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92 (4), 548–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548 .

Weiner, B., Frieze, I., Kukla, A., Reed, L., Rest, S., & Rosenbaum, R. M. (1987). Perceiving the causes of success and failure. In E. E. Jones, D. E. Kanouse, H. H. Kelley, R. E. Nisbett, S. Valins, & B. Weiner (Eds.), Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior (pp. 95–120). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Weisz, J. P. (1984). Contingency judgments and achievement behavior: Deciding what is controllable and when to try. In J. G. Nicholls (Ed.), The development of achievement motivation (pp. 107–136). Greenwich: JAI Press.

Wentzel, K. R. (1998). Social relationships and motivation in middle school: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90 (2), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.90.2.202 .

Wentzel, K. R. (2000). What is it that I’m trying to achieve? Classroom goals from a content perspective. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25 (1), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1021 .

Wentzel, K. (2002). Are effective teachers like good parents? Teaching styles and student adjustment in early adolescence. Child Development, 73 (1), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00406 .

Wentzel, K. R. (2005). Peer relationships, motivation, and academic performance at school. In C. S. Dweck & A. J. Elliot (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 279–296). New York: Guilford Press.

Wentzel, K. R., & Miele, D. B. (Eds.). (2009). Handbook of motivation at school . New York: Routledge.

Wentzel, K. R., & Muenks, K. (2016). Peer influence on students’ motivation, academic achievement, and social behavior. In K. R. Wentzel & G. B. Ramani (Eds.), Handbook of social influences in school contexts: Social-emotional, motivation, and cognitive outcomes (pp. 13–30). New York: Routledge.

Wentzel, K. R., Battle, A., Russell, S. L., & Looney, L. B. (2010). Social supports from teachers and peers as predictors of academic and social motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 35 (3), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.03.002 .

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. (1992). The development of achievement task values: A theoretical analysis. Developmental Review, 12 (3), 265–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(92)90011-P .

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25 (1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015 .

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2002). The development of competence beliefs and values from childhood through adolescence. In A. Wigfield & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Development of achievement motivation (pp. 92–120). San Diego: Academic Press.

Wigfield, A., & Tonks, S. (2004). The development of motivation for reading and how it is influenced by CORI. In J. T. Guthrie, A. Wigfield, & K. C. Perencevich (Eds.), Motivating reading comprehension: Concept-oriented reading instruction (pp. 249–272). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Wigfield, A., & Wagner, A. L. (2005). Competence, motivation, and identity development during adolescence. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 222–239). New York: Guilford Press.

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Yoon, K. S., Harold, R. D., Arbreton, A. J., Freedman-Doan, C., & Blumenfeld, P. C. (1997). Change in children’s competence beliefs and subjective task values across the elementary school years: A 3-year study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89 (3), 451. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.451 .

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Schiefele, U., Roeser, R. W., & Davis-Kean, P. (2006). Development of achievement motivation . In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon & R.M. Lerner (Vol. 3, pp.933–1002). Hoboken: Wiley. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0315 .

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Schiefele, U., Roeser, R. W., & Davis‐Kean, P. (2007). Development of achievement motivation . Hoboken: Wiley.

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Roeser, R. W., & Schiefele, U. (2008). Development of achievement motivation. In W. Damon, R. M. Lerner, D. Kuhn, R. S. Siegler, & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Child and adolescent development: An advanced course (pp. 406–434). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Wlodkowski, R. J. (2011). Enhancing adult motivation to learn: A comprehensive guide for teaching all adults . San Francisco: Wiley.

Woodworth, R. S. (1918). Dynamic Psychology . New York: Columbia University Press.

Yeung, W. J., Linver, M. R., & Brooks–Gunn, J. (2002). How money matters for young children's development: Parental investment and family processes. Child Development, 73 (6), 1861–1879. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00511 .

Zimmerman, B. J., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1990). Student differences in self-regulated learning: Relating grade, sex, and giftedness to self-efficacy and strategy use. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82 (1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.51 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Escuela de Psicología, Universidad de los Andes, Santiago, Chile

Paulina Arango

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paulina Arango .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Education, Universidad de los Andes, Las Condes, Chile

Pelusa Orellana García

Institute of Literature, Universidad de los Andes, Las Condes, Chile

Paula Baldwin Lind

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Arango, P. (2018). Motivation: Introduction to the Theory, Concepts, and Research. In: Orellana García, P., Baldwin Lind, P. (eds) Reading Achievement and Motivation in Boys and Girls. Literacy Studies, vol 15. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75948-7_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75948-7_1

Published : 03 May 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-75947-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-75948-7

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Global Cognition

7 ways to improve your motivation to study (backed by science).

by Winston Sieck updated September 18, 2021

Just about everyone who has ever been in school knows what it feels like to sit in front of the computer, staring at a blank screen. Hoping their term paper would write itself.

Or tried reading a textbook only to find that they have read the same paragraph ten times and still don’t know what they read.

Or decided they would rather clean the clutter out from under their bed than study in the first place.

Bottom line, studying can be kind of a drag. When you have a hundred other things you would rather do and an overwhelming amount of work to do, it is hard to get started and even harder to finish.

Fortunately, there are some simple, scientifically proven ways you can find your motivation and keep it.

What is Motivation to Study?

Motivation comes from a Latin word that literally means “to move.” But what causes someone to be motivated to study has been a hot topic in the world of science.

Researchers believe that your motivation to study can either come from inside you or outside of you. You can be motivated by an internal drive to learn as much possible. Or, you might be motivated to study by an external reward like a good grade, or a great job, or someone promising you a car.

Recently, researchers have discovered that your motivation to study is rooted in lots of factors, many of which we have control over. Rory Lazowski of James Madison University and Chris Hulleman of the University of Virginia analyzed more than 70 studies into what motivates students in schools. They published their paper , “Motivation Interventions in Education: A Meta-Analytic Review, in the journal Review of Educational Research .

Lazowski and Hulleman found that a number of ways to improve motivation consistently yield positive results. Here, I describe seven of the techniques that you can most readily use on your own to power through your own study barriers, and move your learning forward.

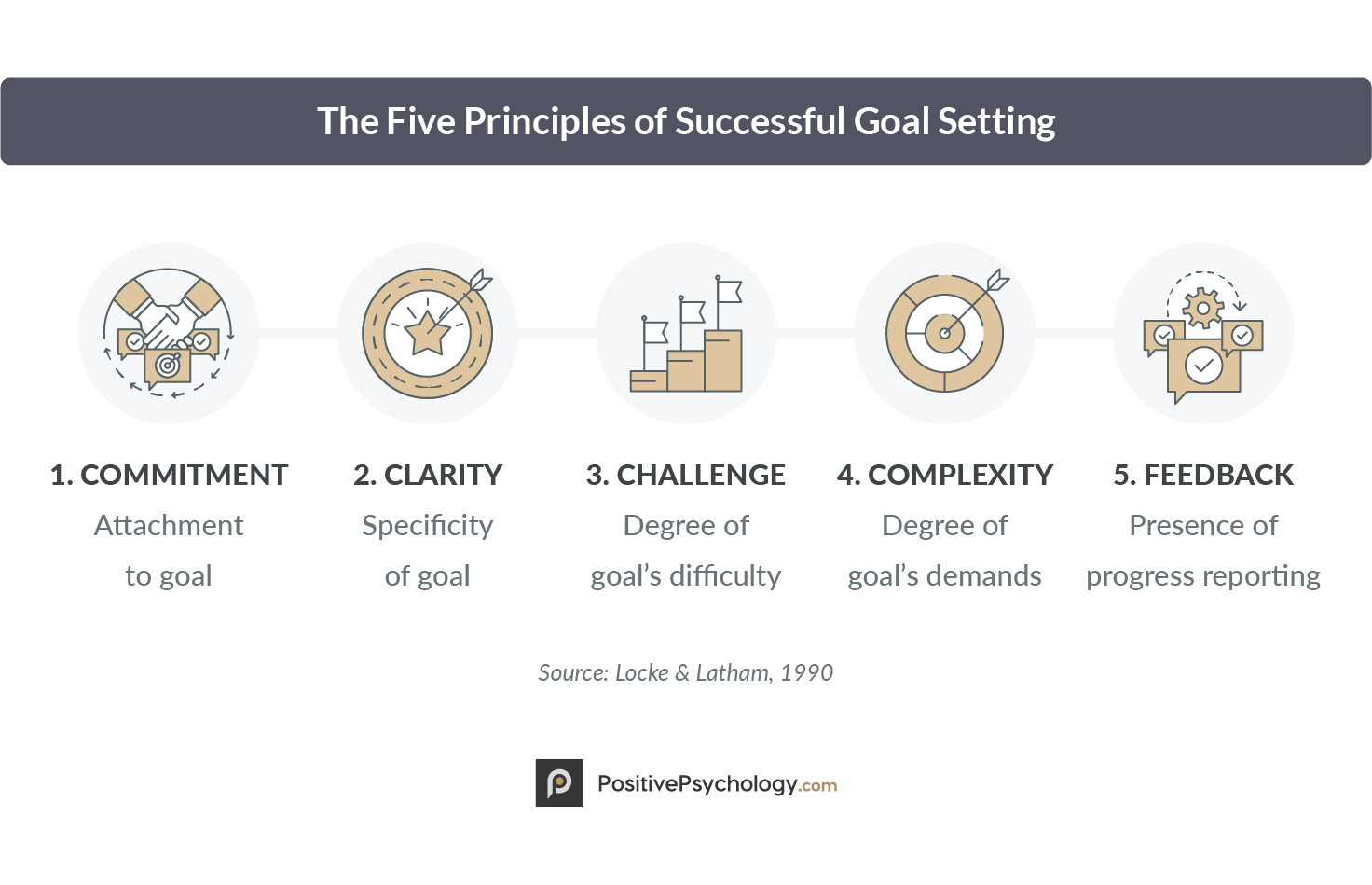

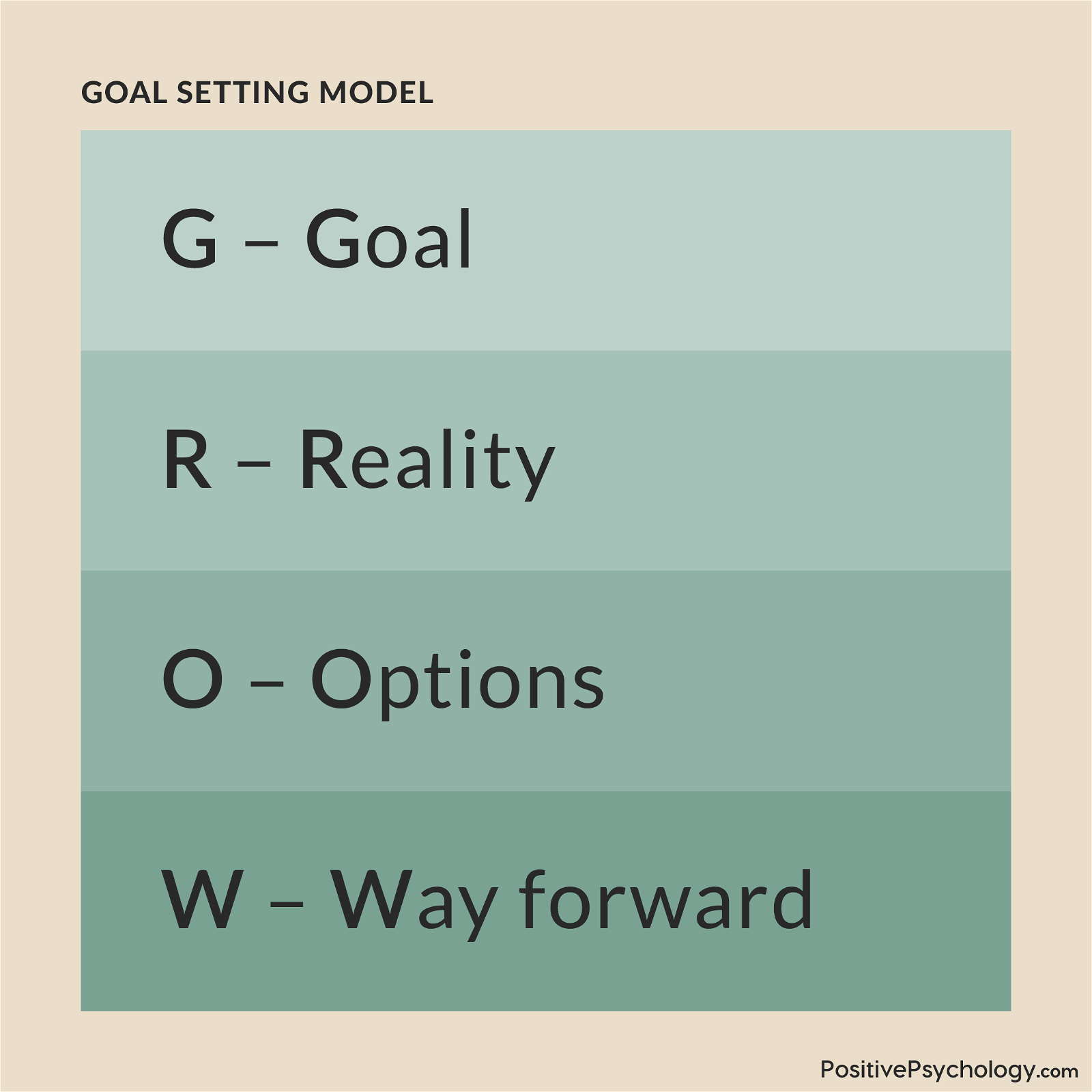

1. Set Clear Goals

You may think to yourself, “My goal is to graduate and get a good job and be rich.” While that’s a fine ambition, by itself it probably won’t help you in school day-to-day.

In order to improve your motivation to study, your goals have to be a little closer to home. In fact, setting clear academic goals has been scientifically linked to higher grade point averages than students who set vague goals, like, “I’ll just do the best I can.”

Set a goal to earn an “A” on a particular test in a particular subject. Or, decide to learn everything you can about a concept because it will help you in the real world. Set a deadline for homework that will force you to finish a task before it is due so you can review it before handing it in. Whatever the goal is, be sure it is specific, relevant, and timely.

2. Don’t Just Shoot For Performance, Go For Mastery

There is nothing more frustrating than studying hard for a test only to get a grade that is less than what you were expecting. At that point, lots of students throw their hands in the air and say, “If this is what happens when I study, why study?”

Resist that urge.

The grades you receive on a test are examples of performance goals. If you set a goal to get an “A”, and stop there, you may only study the things that you think will be on the test, but not necessarily the things that will give you mastery of the concept.

Students who consistently strive for mastery , really learning what they are studying, almost always see their grades improve as a result.

Mastery goals also help with your motivation to study. If you want to learn everything there is to know, you are less likely to put off starting that process.

3. Take Responsibility for Your Learning

It’s tempting to blame your grades on other people. The teacher doesn’t like you. They never taught what you were tested on. Your homework assignment doesn’t apply. When you blame others for your performance, you are more likely to do poorly on tests, assignments and projects.

Taking responsibility for your own learning can make a world of difference when it comes to getting yourself motivated to study. Recognizing that you are in charge of what you learn can help you start studying, but it can also keep you going when other distractions threaten to take your attention away.

Next time you are tempted to stop in the middle of an assignment and do something else, pause. Take a breath. Then, say out loud, “No one is going to learn this for me.” You might be surprised at how hearing those words affect your focus.

4. Adopt a Growth Mindset

Some people still believe that you’re either born smart (or not). And there’s not much you can do about it. However, research has shown that successful people tend to believe that intelligence is something you build up over your life. These folks have a growth mindset.

When your intelligence is challenged by hard assignments or difficult concepts, people with a growth mindset tend to think, “I don’t know this yet, but if I work hard, I will learn it.”

Researchers found that believing your brain can get stronger when you tackle hard things not only improves your mastery of what you are learning, it also improves your grades and increases your motivation to study.

The next time you are faced by a blank screen or hard textbook chapter remember, “I don’t know this yet, but if I work hard, I will learn it.”

5. Find the Relevance

If you ever want to annoy your math teacher, tell them algebra has no relevance in the real world. Alternatively, try to figure out how what you are studying relates to your life. Studies have shown that high school students who were asked to write down how their subject matter related to their everyday life saw a significant jump in their GPA.

Before you start studying, try jotting down a few ways this information will come in handy in the future. Making this connection will help you see value in what you are doing and get you started on an assignment or topic.

Sometimes, the connection between what you are learning and how it applies to your life is not easy to see. Try searching the web for applications of your topic to help you see the real-life relevance of what you are learning.

6. Imagine Your Future Self

Imagine what your life will be like in 10 years. Are you successful? Do you have a great career that you love? Are you living in the best city in the world?

Now, imagine how you are going to get there.

Some people automatically connect the school work they are doing now with getting into a good college or training program that will lead to their desired future. Other students have difficulty making that connection.

Having the ability to imagine your future self is a skill that has been shown to improve motivation to study. It has also been linked to higher grades, lower cases of truancy and fewer discipline problems in school.

Next time you are faced with a particularly daunting assignment, close your eyes and picture what you want your life to be like. Then, recognize that in order to have the life you want, you have to do the assignment in front of you.

7. Reaffirm Your Personal Values

What do you value most? What are the two or three most important qualities you can possibly develop? Do you strive to be honest in everything you do? Do you value kindness? Is success the most important value in your life?

Taking a few minutes now and again to reaffirm your values by writing in a journal or meditating about them can help you focus your efforts in other areas of your life.

If you value family over everything, your ability to take care of your family will motivate you to study and do well in school. If you value honesty, you will never feel inclined to cheat on a test, but will work hard to study.

Ultimately, finding the motivation to study is less about going on a treasure hunt and more about changing the way you think about learning. Even implementing a few of these seven tips can help you stay focused and keep going.

Image Credit: PublicDomainPictures

Lazowski, R. A., & Hulleman, C. S. (2016). Motivation interventions in education: A meta-analytic review. Review of Educational research , 86(2), 602-640. DOI: 10.3102/0034654315617832

Study Smarter

Build your study skills with thinker academy.

About Winston Sieck

Dr. Winston Sieck is a cognitive psychologist working to advance the development of thinking skills. He is founder and president of Global Cognition, and director of Thinker Academy .

Reader Interactions

October 2, 2018 at 4:59 pm

Thanks for sharing this post. I plan to share it with my students this week. We’re implementing some growth mindset and mindfulness practices this year. This will be a good reinforcement of some of those ideas and will provide some new insight as well. I think it will be well-received. I’ve been pleasantly surprised at how open they’ve been to these ideas so far. Thanks again.

October 2, 2018 at 5:24 pm

That’s great, Tony. Excellent to hear the success you’re having with these ideas in your class. Thanks for stopping by..

October 25, 2021 at 12:51 pm

Thanks for posting this . I felt it after reading it and I think that if I prepare it today tomarow will be good . From this I’ll stay motivated .

October 2, 2018 at 6:54 pm

Thank greatly for this post. I’m studying at college at 45yrs ,sometimes want to give up studying but you came along with this great post. Great assurance and encouragement for young and old students alike.

Will have to share with my students as well,

kind regards,

clotilda Claudia Harry Solomon islands.

October 2, 2018 at 7:14 pm

Yep, we all need a little motivation boost at any age. Way to keep learning, Clotilda.

November 16, 2018 at 12:08 am

Thanks for providing a resource for our children to grow in knowledge. Seems that no matter what the age, we all struggle with these issues.

November 17, 2018 at 4:39 pm

No doubt, Michael! Managing motivation is a life-long skill we can teach our kids. Good to see you here – thanks for stopping by..

October 6, 2020 at 4:23 am

Thank you so much for motivating, the point you are mentioned such as set goal and go for mastery, be responsibility for learning, etc. all these points are really very helpful and they are very useful for study thank you so much for sharing

February 3, 2021 at 5:18 am

Thank you! Without following all of these steps, it’s hard to have any significant academic success, I think. It helps me not to lose motivation with step-by-step planning: I divide the global goal into several small short-term goals and achieving even minimal results makes me happy and motivates me to try harder. Of course, there are also bad periods, when I feel exhausted and overwhelmed. But a little rest allows me to get back on track.

- Save Your Ammo

- Publications

GC Blog Topics

- Culture & Communication

- Thinking & Deciding

- Learning Skills

- Learning Science

Online Courses

- Thinker Academy

- Study Skills Course

- For Parents

- For Teachers

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing