Stress in College Students: What to Know

Strong social connections and positive habits can help ease high levels of stress among college-age adults.

Getty Images

From socializing to working out, here's how college students can better manage stress.

From paying for school and taking exams to filling out internship applications, college students can face overwhelming pressure and demands. Some stress can be healthy and even motivating under the proper circumstances, but often stress is overwhelming and can lead to other issues.

"Stress is there for a reason. It's there to help mobilize you to meet the demands of your day, but you're also supposed to have times where you do shut down and relax and repair and restore," says Emma K. Adam, professor of human development and social policy at Northwestern University in Illinois.

Chronic and unhealthy levels of stress is at its worst among college-age students and young adults, some research shows. According to the American Psychological Association's 2022 "Stress in America" report , 46% of adults ages 18 to 35 reported that "most days they are so stressed they can't function."

In a Gallup poll that surveyed more than 2,400 college students in March 2023, 66% of reported experiencing stress and 51% reported feelings of worry "during a lot of the day." And emotional stress was among the top reasons students considered dropping out of college in the fall 2022 semester, according to findings in the State of Higher Education 2023 report, based on a study conducted in 2022 by Gallup and the Lumina Foundation.

As students are navigating a new environment and often living independently for the first time, they encounter numerous opportunities, responsibilities and life changes on top of academic responsibilities. It can be sensory overload for some, experts say.

“Going to college has always been a significant time of transition developmentally with adulthood, but you add to it everything that comes along with that transition and then you put onto it a youth mental health crisis, it’s just compounded in a very different way," says Jessica Gomez, a clinical psychologist and executive director of Momentous Institute, a researched-based organization that provides mental health services and educational programming to children and families.

Experts say college students have experienced heightened stress since the COVID-19 pandemic, a trend likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

“What some of our research at Gallup has shown is that we had a rising tide of negative emotions, not just in the U.S. but globally, in the eight to 10 years leading up to the pandemic, and of course it got worse during the pandemic," says Stephanie Marken, senior partner of the education research division at Gallup who conducted the 2023 study. “For currently enrolled college students, there’s so many contributing factors.”

Adam notes that multiple factors combine to contribute to heightened stress among younger adults, including the nation’s racial and political controversies, as well as anxiety regarding their futures fueled by climate change, global unrest and economic uncertainty. Female students reported higher levels of stress than males in the Gallup poll, which Marken says could be attributed to several factors like increased internal academic pressure, caregiving responsibilities and the recent uncertainty regarding abortion rights following the reversal of Roe v. Wade.

All of this, plus the residual effects of pandemic learning, has contributed to rising stress for college students, Marken says.

"We need to give them a lot of credit," she says. "They had the most challenge in remote learning of all the learners that have come before them. Many of them had to graduate high school and study remotely, or were a first-year college student during the pandemic, and that was incredibly difficult."

The challenges that came with that learning environment will likely affect students throughout college, she says, as well as typical stressors like discrimination, harassment and academic challenges.

"Those will always be present on college campuses," she says. "The question is, how do we create a student who overcomes those challenges effectively?"

Experts suggest a range of specific actions and positive shifts that can help ease stress in college students:

- Notice the symptoms of heightened stress.

- Build and maintain social connections.

- Sleep, eat well and exercise.

Notice the Symptoms of Heightened Stress

College students can start by learning to identify when normal stress increases to become unhealthy. Stress will appear differently in each student, says Lindsey Giller, a clinical psychologist with the Child Mind Institute, a nonprofit focused on helping children and young adults with mental health and learning disorders.

"Students prone to anxiety may avoid assignments as well as skip classes due to experiencing shame for being behind or missing things," she says. "For some, they may also start sleeping in more, eating at more random times, foregoing self-care, or look to distraction or escape mechanisms, like substances, to fill time and further avoid the reality of workload assignments."

Changes in diet and sleeping are also telling, as well as increased social isolation and pulling away from activities that once brought you pleasure is also a red flag, Gomez says.

She warns students to watch for signs of irritability, a classic indicator of increased stress that can often compound issues, especially within interpersonal relationships.

"Your body speaks to you, so be in tune with your body," she says.

Build and Maintain Social Connections

Socializing can help humans release stress. Experts say having fun and finding joy in life keep stress levels manageable, and socializing is particularly important developmentally for young adults. In the 2023 Gallup poll, 76% of students reported feeling enjoyment the previous day, which Marken says was an encouraging sign.

But 39% reported experiencing feelings of loneliness and 36% reported feeling sad. “We are in the midst of an epidemic of loneliness in our country, where we are noticing people don’t have the skills to build friendships,” Gomez says.

Discover six

Talking about feelings of stress can help college students cope, which is why the amount of students feeling lonely is concerning, Marken says. If students don't feel like they belong or have a social network to call on when feeling stressed, negative emotions are compounded.

“I think we’re more connected, and yet we’re more isolated than ever," she says. "It feels counterintuitive. How can you be more connected to your network and campus than ever, yet feel this lonely? Just because they have a device to connect with each other in a transactional way doesn’t mean it’s a meaningful relationship. I think that’s what we’re missing on a lot of college campuses is students creating meaningful connections about a shared experience."

Setting boundaries on social media use is crucial, Gomez says, as is getting plugged in with people and organizations that will be enriching. For example, Gomez says she joined a Latina sorority to be in community with others who shared some of her life experiences and interests.

Sleep, Eat Well and Exercise

Maintaining healthy habits can help college students better manage stressors that arise.

"Prioritizing sleep, moving your body, getting organized, and leaning on your support network all help college students prevent or manage stress," John MacPhee, CEO of The Jed Foundation, a nonprofit that aims to protect emotional health and prevent suicide among teens and young adults, wrote in an email. "In the inevitable moments of high stress, mindful breathing, short brain breaks, and relaxation techniques can really help."

Experts suggest creating a routine and sticking to it. That includes getting between eight and 10 hours of sleep each night and avoiding staying up late, Gomez says. A nutrient-rich diet can also go a long way in maintaining good physical and mental health, she says.

Getting outdoors and being active can also help students limit their screen time and use of social media.

“Walking to campus, maybe taking that longer walk, because your body needs that to heal," Gomez says. "It’s going to help buffer you. So if that’s the only thing you do, try to do that."

Colleges typically offer mental health resources such as counseling and support groups for struggling students.

Students dealing with chronic and unhealthy stress should contact their college and reach out to friends and family for support. Reaching out to parents, friends or mentors can be beneficial for students when feelings of stress come up, especially in heightened states around midterm and final exams .

Accessing student supports and counseling early can prevent a cascading effect that results in serious mental health challenges or unhealthy coping mechanisms like problem drinking and drug abuse , experts say.

"Know there are lots of resources on campus from academic services to counseling centers to get structured, professional support to lower your workload, improve coping skills, and have a safe space to process anxiety, worry, and stress," MacPhee says.

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Unexpected College Costs

Tags: mental health , colleges , stress , education , students , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

Mental health on college campuses.

Sarah Wood June 6, 2024

Advice From Famous Commencement Speakers

Sarah Wood June 4, 2024

The Degree for Investment Bankers

Andrew Bauld May 31, 2024

States' Responses to FAFSA Delays

Sarah Wood May 30, 2024

Nonacademic Factors in College Searches

Sarah Wood May 28, 2024

Takeaways From the NCAA’s Settlement

Laura Mannweiler May 24, 2024

New Best Engineering Rankings June 18

Robert Morse and Eric Brooks May 24, 2024

Premedical Programs: What to Know

Sarah Wood May 21, 2024

How Geography Affects College Admissions

Cole Claybourn May 21, 2024

Q&A: College Alumni Engagement

LaMont Jones, Jr. May 20, 2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- AIMS Public Health

- v.8(1); 2021

Risk factors associated with stress, anxiety, and depression among university undergraduate students

Mohammad mofatteh.

1 Lincoln College, University of Oxford, Turl Street, Oxford OX1 3DR, United Kingdom

2 Merton College, University of Oxford, Merton Street, Oxford OX1 4DJ, United Kingdom

3 Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3RE, United Kingdom

It is well-known that prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression is high among university undergraduate students in developed and developing countries. Students entering university are from different socioeconomic background, which can bring a variety of mental health risk factors. The aim of this review was to investigate present literatures to identify risk factors associated with stress, anxiety, and depression among university undergraduate students in developed and developing countries. I identified and critically evaluated forty-one articles about risk factors associated with mental health of undergraduate university students in developed and developing countries from 2000 to 2020 according to the inclusion criteria. Selected papers were analyzed for risk factor themes. Six different themes of risk factors were identified: psychological, academic, biological, lifestyle, social and financial. Different risk factor groups can have different degree of impact on students' stress, anxiety, and depression. Each theme of risk factor was further divided into multiple subthemes. Risk factors associated with stress, depression and anxiety among university students should be identified early in university to provide them with additional mental health support and prevent exacerbation of risk factors.

1. Introduction

Mental health is one of the most significant determinants of life quality and satisfaction. Poor mental health is a complex and common psychological problem among university undergraduate students in developed and developing countries [1] . Different psychological and psychiatric studies conducted in multiple developed and developing countries across the past decades have shown that prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression (SAD) is higher among university students compared with the general population [2] – [4] . It is well established that as a multi-factorial problem, SAD cause personal, health, societal, and occupational issues [5] which can directly influence and be influenced by the quality of life. The level of stress cited in self-reported examinations and surveys is inversely correlated with life quality and well-being [6] .

Untreated poor mental health can cause distress among students and, hence, negatively influence their quality of lives and academic performance, including, but not limited to, lower academic integrity, alcohol and substance abuse as well as a reduced empathetic behaviour, relationship instability, lack of self-confidence, and suicidal thoughts [7] – [9] .

A 21-item self-evaluating questionnaire, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), is the most common tool used for diagnoses of depression [10] . A BDI-based survey in five developed countries in Europe (European Outcome of Depression International Network-ODIN in the United Kingdom, Netherlands, Greece, Norway, and Spain) concluded that overall 8.6% (95% CI, 7.95–10.37) of the resident population are dealing with depression [11] . Similar studies confirmed that about 8% of the population in developed and developing countries suffer from depression [12] . Data from systematic review studies revealed that this depression rate is much higher among university students and around one third of all students in the majority of the developed countries have some degree of SAD disorders; and depression prevalence has been increasing in academic environments over the past few decades [3] .

Despite all the efforts to increase awareness and tackle mental health problems among university students, there is still an increasing number of depression and suicide among students [13] , indicating a lack of effectiveness of the measures adopted. In addition to an increase in the prevalence of mental health issues, comparing students and non-college-attending peers demonstrated that the severity of psychological disorders that students receive treatment for has also increased [14] . For example, the rate of suicide among adolescents has increased significantly over the past few decades [15] . In fact, suicide as a result of untreated mental health is the second cause of death among American college students [16] , emphasizing the importance of identifying and treating risk factors associated with SAD.

SAD can be manifested in different forms; however, some common overt symptoms include loss of appetite, sleep disturbance, lack of concentration, apathy (lack of enthusiasm and concern), and poor hygiene. Studying SAD is particularly important among university students who are future representatives and leaders of a country. Furthermore, most undergraduate students enter university at an early age; and dealing with SAD early in life can have long-term negative consequences on the mental and social life of students [3] . For example, a longitudinal study in New Zealand over 25 years demonstrated that depression among people aged 16–21 could increase their unemployment and welfare-dependence in long-term [17] .

A better understanding of SAD among students in developed and developing countries not only helps governments, universities, families, and healthcare agencies to identify risk factors associated with mental health problems in order to minimise such risk factors, but also provides them with an opportunity to study how these factors have been changing in the academia.

This review aims to provide an updated understanding of risk factors associated with SAD among post-secondary undergraduate and college students in developed and developing countries by using existing literature resources available to answer the following question:

“Aetiology of depression and anxiety: What are risk factors associated with stress, anxiety and depression among university and college undergraduate students studying in developed and developing countries?”

It is worth mentioning that this review focuses on SAD risk factors of university students in developed and developed countries, and does not cover underdeveloped countries which can have their own niche problems (such as poverty). However, this review takes into account international students who migrate from underdeveloped countries to developed and developing countries to pursue their education.

2.1. Aims and objectives

The aims of this review were to identifying principal themes associated with depression and anxiety risk factors among university undergraduate students. The objectives of this review are to design a rigorous searching methodology approach by using appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria, to conduct literature searches of publicly available databases using the designed methodology approach, to investigated collected literature resources to identify risk factors associated with the depression and anxiety which have not changed, and to identify principal themes associated with SAD risk factors among university undergraduate students.

2.2. Designed approach for literature review

A narrative review based on a comprehensive and replicable search strategy is used in this review. This approach is justified and preferred, over other approaches such as primary data gathering, because of the timescale of the research (2000 to 2020-temporal reasons), and extent of the research (developed and developing countries-spatial reasons).

2.3. Criteria for inclusion and exclusion of articles

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for articles and academic writings used in this review are as follows:

2.3.1. Date

2000 to 2020 are included Academic writings which are published between in this review. Initially, during a pilot search, search strategies covered 1990 to 2020. However, the majority of the search results (more than 80% of the search results and more than 88% of applicable search results) were from 2000 to 2020, which indicates the importance of mental health issue and increased awareness over the past two decades. Therefore, for the final search, papers from 2000 to 2020 were included.

2.3.2. Study design

Literatures included in this narrative review were primary research articles, review articles, systematic reviews, mini-reviews, opinion pieces, correspondence, clinical trials, and cases reports published in peer reviewed journals.

2.3.3. Country

The narrative review was limited to developed and developing countries definition by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs [18] . Abstract and method sections of search results were screened to check the country of research.

2.3.4. Language

Peer-reviewed articles published in English were only included in this narrative review.

2.3.5. The explanation for papers exclusion

The main reason for papers excluded from consideration after search results was that they focused on intervention and therapies associated with SAD. Other reasons for exclusion was that studies were conducted on a mixture of undergraduate and graduate students or focused solely only graduate students. Studies which focused on other types of mental disorders such as eating disorders but did not focus on SAD were excluded too. The conducted search did not exclude any gender or specific age category.

2.4. Strategies used for search and limitations

In this review, a robust and replicable search strategy was designed to identify appropriate articles by searching PubMed, MEDLINE via Ovid, and JSTOR electronic databases. These databases were selected because they encompass biopsychosocial papers published on SAD. The date chosen for this search was for articles published between 2000 to 2020 which covers the past two decades. Once key articles were identified, a search for citation of those papers was conducted, and the bibliography of those papers were further screened to identify potential articles which can be relevant.

2.5. Search terminologies used

To conduct searches in databases mentioned above, the following search terms were used: students stress, anxiety, depression risk factors, university stress, anxiety, depression risk factors, student mental health developed and developing countries, students stress, anxiety and depression developed and developing countries. The operation AND was used to connect stress, anxiety, depression, mental health, developed, developing, countries, students. The search for each term was conducted in all fields (title, abstract, full text, etc.).

2.6. Screening, selecting search results, and data extraction

The search results were exported into separate Excel and EndNote X8 files. Titles and abstracts from all articles were screened to determine their relevance to the topic of this review. Potentially relevant articles were fully read to establish their relevance. Each paper which was included according to the inclusion criteria described above was read fully. A word file was created to identify themes associated with SAD risk factors which is included in the Results. An initial search resulted in 1305 articles. The title and abstract of individual papers were read for relevance, resulting in 60 papers which were relevant for the research question asked in this review. All 60 papers were read completely, and from those, 19 were excluded based on the criteria mentioned before. Therefore, the total number of papers for consideration was 41. A flowchart explaining the procedure for identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of papers is shown in Figure 1 .

Figure 2 provides a quantitative summary of the papers included in this narrative review. In terms of the distribution of the countries where the research was conducted, included papers were mainly articles which carried out studies in the USA (n = 17), followed by China and Canada (each n = 5), UK (n = 4), Japan (n = 3), Germany and Australia (each n = 2), South Korea, Hungary, Switzerland (each n =1) ( Figure 2A ). As for article types included in this review, original research articles, including quantitative and qualitative studies, which relied on obtaining data including cross-sectional studies, interviews, case-control studies, surveys, and questionnaire, were the highest (n = 37) followed by meta-analysis, literature and systematic reviews ( Figure 2B ). Another interesting observation was that although the search was carried out from 2000–2020, most papers were concentrated in the period from 2016 to 2020 ( Figure 2C ). This can be due to the reason that mental health is becoming more important over the past few years. Alternatively, a higher number of papers included from 2016 onward can be due to unintended selection bias. The smallest study covered in this narrative review was conducted on 19 students and the largest one on 153,635 students, adding up to 236,104 students, who were included in articles covered in this narrative review in total. Most studies on mental health, anxiety, and depression use standardised approaches such as patient-filled general health questionnaires, Pearling coping questionnaire, internally regulated surveys, BDI, DSM-IV symptomology, and general anxiety and burnout scales such as Maslach Burnout Inventory.

3.1. Literature search results

Following the search protocol shown in Figure 3 , a list of included papers identified which can be found in the Table 1 .

3.2. Prevalence of mental health disorders in students

Literature showed that mental health problems are common phenomenon among students with a higher prevalence compared to the general public. For example, surveying more than 2800 students in five American large public universities demonstrated that more than half of them experienced anxiety and depression in their last year of studies [19] . Similarly, a survey of Coventry University undergraduate students in the UK showed that more than one-third of them had experienced mental health issues such as anxiety and depression over the past one year since they were surveyed [20] . In agreements with these results, Maser et al. [21] found that prevalence of mental health disorders including anxiety and depression was higher among medical students compared to the general non-student population of the same age. These studies demonstrated that the prevalence of SAD among students has remained higher than the average population over the past two decades.

SAD are not only prevalent among students, but also persistent. By conducting a follow-up survey study of students over two years, Zivin et al. [19] demonstrated that more than half of students retain their higher levels of anxiety and depression over time. This can be due to a lack of SAD treatment or persistence of existing risk factors over time.

3.3. Risk factors associated with stress, anxiety, and depression

SAD are multifactorial, complex psychological issues which can have underlying biopsychosocial reasons. Multiple risk factors which affect the formation of SAD among undergraduate university students in developed and developing countries were identified in this review. These factors can be categorized into multiple themes including psychological, academic, biological, lifestyle, social and financial. A summary of risk factors and their associated publications are shown in Table 2 .

3.3.1. Psychological factors

Self-esteem, self-confidence, personality types, and loneliness can be associated with SAD among university students. Students who have a lower level of self-esteem are more susceptible to develop anxiety and depression [22] . Also, students with high neuroticism and low extraversion in five-factor personality inventory [23] are more likely to develop SAD during university years [24] . Other psychological factors such as feeling of loneliness plays important roles in increasing SAD risk factors [24] . Moving away from family and beginning an independent life can pose challenges for fresher students such as loneliness until they adjust to university life and expand their social network. Indeed, Kawase et al. [24] showed that students who live in other cities than their hometown for studying purposes are more likely to develop anxiety and depression.

Some students enter the university with underlying mental conditions, which can become exacerbated as they transition into the independent life at university. While depression is higher among university and college students compared to the general public, students with a history of mental health problems, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), are more prone to development of anxiety and depression during their university lives compared to students who did not have such experience before starting their degrees [25] . Furthermore, exposure to violence in childhood either at the household or the community correlates with SAD formation later in life and at University [26] . Therefore, low self-esteem and self-confidence, having an underlying mental health condition before beginning the university, personality type (high neuroticism and low extravasation), and loneliness can increase the probability of SAD formation in students.

3.3.2. Academic factors

Multiple university-related academic stressors can lead to SAD among students. One of these factors which was strongly present in many studies evaluated in this review was the subject of the degree. Medical, nursing, and health-related students have a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety compared to their non-medical peers [24] , [27] – [28] . Medical and nursing students who have both theoretical duties and patient-related work usually have the highest level of workload among university students, consequently deal more with anxiety and depression [27] , [29] . In addition, students who major in psychology and philosophy, similar to nursing and medical students, are more likely to develop depression during their studies compared to others [24] . These studies did not identify whether students who have underlying mental health conditions are more likely to choose certain subjects such as philosophy, psychology, or subjects which lead to caring roles such as nursing and medicine. Because of the nature of their work, medical and nursing students who deal with people's health can experience depression and anxiety as a result of fears of making mistakes which can result in harming patients [27] . Students with practical components in their degree are required to travel to unfamiliar places for fieldwork and work experience which can add to their stress and anxiety [27] .

Also, some prospective students, especially those who study nursing and medicine, usually do not have a clear understanding of the curriculum and workload associated with the subject before entering the university, therefore, they can face a state of disillusionment once they begin their studies at university [27] – [29] . It is worth mentioning that not all studies found a significant correlation between the subject of study and SAD development [30] . This can be explained by differences in sample type and size which results in variations existing in the amount of workload and curriculum in similar subjects taught in various universities in different countries.

Studying a higher degree can be a challenging task which requires mental effort. Mastery of the subject can negatively correlate with self-esteem, anxiety, and depression among university students with students who have a mastery of subject demonstrating a lower level of stress and anxiety [31] . Also, students who study in a non-native language report the highest level of anxiety and depression during their freshman years, and their stress levels decrease during the subsequent study years [32] . This can be explained by the fact that students who are studying in a foreign language usually are those who have migrated abroad, therefore, require some time to adjust to their new lives. Different studies showed that the level of anxiety and depression among both international and home students could correlate with the year of study with fresher students who enter the university and students at the final year of their studies experience the greatest amount of anxiety and depression with different risk factors [22] , [32] . While fresher students experience SAD because of challenges in adjustments to university life, past negative family experience, social isolation and not having many friends, final year students report uncertainty about their future, prospective employment, university debt repayment and adjusting to the life after university as major risk factors for their SAD [22] , [32] . Therefore, a shift in SAD risk factors themes are observed as students make a progress in their degrees.

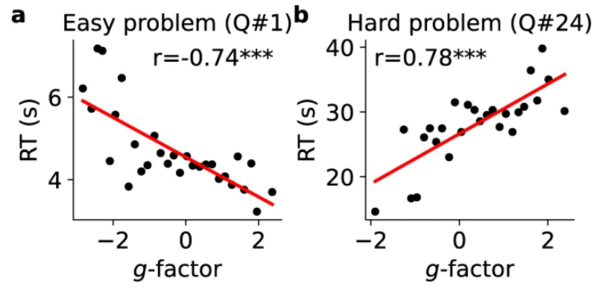

Students spend a significant portion of their time at university being engaged with their academic activities, and unpleasant academic outcomes can influence their mental health. Receiving lower grades during the time of studies can negatively influence students' mental health, causing them to develop SAD [33] , [34] . Academic performance during undergraduate studies can determine the degree classification, which can, subsequently, influence students' opportunities such as employment success rate or access to postgraduate courses [27] . Conversely, both the number of students with mental health problem symptoms and the severity of students' SAD increase during exam time [35] , reflecting a direct relationship between academic pressure and students' mental health states. However, the causal relationship is not well-established; it is possible that depression and associated problems such as temporary memory loss and lack of concentration [36] are reasons for poor academic grades or inversely, students feel stressed leading to depression because of their poor performance in their exams. A mutual relationship can exist between grades and mental health, as having a poor mental health can reciprocally cause students to get lower grades [34] , leading to a vicious cycle of mental health and academic performance. Interestingly, students' sense of social belonging and coherence to the university community was reduced during exam periods [35] . This can be explained by the reduced participation rate of students in university social activities and clubs as well as an increased sense of competition with their peers. Furthermore, students interact directly and indirectly with teachers, lecturers, tutors, and other staff; therefore, the relationship between students and academic staff can influence students' mental health. A negative and abusive relationship with teachers and mentors can be another factor causing SAD among undergraduate students [27] .

On the other hand, being a part-time student is a protective factor for anxiety and depression, and part-time students have better mental health compared to students with full-time status [34] . This can be explained by financial securities which have a source of income can bring or because part-time students are usually older than full-time students [34] , and therefore, more emotionally stable. In conclusion, risk factors increasing SAD among university students include high workload pressure, fear of poor performance in exams and assessments, wrong expectations from the course and university, insufficient mastery in the subject, year of study, and a negative relationship with academic staff.

3.3.3. Biological factors

Mental health can be influenced by ones' physical health. Presence of an underlying health condition or a chronic disease before entering the university can be a predictor of having SAD during university years [31] , [33] . Students with physical and mental disabilities can be in a more disadvantaged position and do not fully participate in university life leading to SAD formation [33] .

An association between gender and depressive disorders have been observed in several studies [21] , [27] , [34] , [37] . Female students had a higher prevalence of SAD compared to male students. Interestingly, while female students demonstrated a higher level of SAD, the dropout rate of female students with a mental health problem from university was lower compared to their male counterparts [33] . On the other hand, while females are at a higher risk of developing depressive disorders, males with depressive disorders are less willing to seek professional help and ask for support due to the stigma attached to mental health [38] , causing exacerbation of their problem over time [20] .

Age can be another factor related to SAD. Younger students report a higher level of SAD compared to older students [34] , [37] . However, other meta-analysis studies did not find a significant correlation between students' age and their mental health which can be due to sampling differences [39] . Some studies showed that while older undergraduate students have a higher determination to do well in the university [40] , those who have family commitments are more prone to develop SAD during their degrees [27] . These discrepancies in findings can be explained by different sample sizes and types of studies which can be influenced by various confounding factors such as nationality, country of study, degree of studies, gender, and socioeconomic status. Similarly, a lack of correlation between depression prevalence and year of study is observed as some studies have reported a higher prevalence among earlier years of studies, while others have shown a higher prevalence among students as they move closer to the end of their studies [41] . These differences can be explained by different causes of depression in a different age; for example, while depression in younger adults can be due to changes in their environment and difficulties in adapting to a new life, older adults can have depression symptoms because of a lack of certainty for their future and employment. Nevertheless, differences exist between SAD risk factors associated with young and older students. Overall, biological risk factors affecting SAD include age of students, gender, and underlying physical conditions before entering the university.

3.3.4. Lifestyle factors

Moving away from families and beginning a new life requires flexibility and adaptation to adjust to a new lifestyle. As most undergraduate students leave their family environment and enter a new life with their peers, friends, and classmates, their behaviour and lifestyle change too. Multiple lifestyle factors such as alcohol consumption, tobacco smoking, dietary habits, exercise, and drug abuse can affect SAD. Alcohol consumption is high among students with SAD [28] ; a causal relationship was not been established in this study though.

Tobacco smoking is another risk factor associated with SAD which is common among students, especially students who study in Eastern developed and developing countries such as China, Japan and South Korea [24] , [42] . Most students, especially male students, smoke because of social bonding and the rate of social smoking is directly correlated with SAD [24] , [42] . Social smokers are less willing to quit smoking, and more likely to persist in their habit, resulting in long term negative physical and psychological health consequences [42] . Illegal substance abuse can be another factor important in SAD among young people [43] . Academic-related stress and social environment in university dormitories and student accommodations can encourage students to use illegal drugs, smoke tobacco and consume alcohol excessively as a coping mechanism, resulting in SAD [44] . Interestingly, students who perceived they had support from the university were feeling less stressed and were less at the risk of substance abuse [45] , indicating the important role of social support in preventing and alleviating depression symptoms. This is of particular importance as a new social habit and behaviour adapted early during life can last for a long time. Furthermore, students who do not have a healthy lifestyle can feel guilt, which can worsen their SAD condition [46] . Interestingly, Rosenthal et al. [47] showed that negative behaviours resulting from alcohol consumption such as missing the next day class, careless behaviour and self-harm, verbal argument or physical fight, being involved in unwanted sexual behaviour, and personal regret and shame could be the main reasons for depression associated with drinking alcohol, rather than the amount of alcohol consumed.

In contrast, a moderate to vigorous level of physical activity can be a protective factor against developing SAD during university life [37] , [48] . Students who have a perception of having inadequate time during their studies do not spend enough time for exercise and can develop SAD symptoms [27] .

Another lifestyle-related risk fact associated with SAD is sleep. Many young people do not receive sufficient sleep, and sleep deprivation is a serious risk factor for low mood and depression [28] , [47] . Self-reported high level of stress and sleep deprivation is common among American students [31] , [49] . Insufficient sleep can act as a vicious cycle- academic stress can cause sleep deprivation, and insufficient sleep can cause stress due to poor academic performance since both sleep quality and quantity is associated with academic performance [28] . Overall, poor sleeping habit is associated with a decreased learning ability, increase in anxiety and stress, leading to depression.

Different negative lifestyle behaviours such as tobacco smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, unhealthy diet, lack of adequate physical activity, and insufficient sleep can increase the risk of SAD formation among university students.

3.3.5. Social factors

Having a supportive social network can influence students' social and emotional wellbeing, and subsequently lower their probability of having anxiety and depression in university [27] , [37] , [50] . The quality of relationship with family and friends is important in developing SAD. Having a well-established and supportive relationship with family members can be a protective factor against SAD development, which, in turn, can affect the sense of students' fulfilment from their university life [27] . The frequency of family visits during university years negatively correlates with SAD development [33] . Family visits can be more challenging for international students who live far away from their families, therefore adding to existing problems of international students who live and study abroad.

In contrast, having a negative relationship with family members, especially parents, can cause SAD formation among students in university [51] . Similarly, having a strict family who posed restrictions on behaviours and activities during childhood can be a predictor of developing SAD during university years [51] .

Also, it is shown that being in a committed relationship has a beneficial protective factor against developing depressive symptoms in female, but not male, students [52] . Interestingly, both male and female students who were in committed relationships reported a lower alcohol consumption compared to their peers who were not in committed relationships [52] .

Involvement in social events such as participating in sporting events and engaging in club activities can be a protective factor for mental health [32] , [37] . Assessing preclinical medical students' social, mental, and psychological wellbeing showed that while first year students demonstrate a decrease in their mental wellbeing during the academic year, they have an increase in their social wellbeing and social integration [53] . This can be explained by the time period required for fresher students who enter the university to adjust to the social environment, make new friends, and integrate into the social life of the university.

Access to social support from university is another factor which is negatively correlated with developing anxiety and depression [31] . It is worth mentioning that different universities provide different degrees of social support for students which can reflect on different anxiety and depression observed among students of different universities.

Importantly, sexual victimization during university life can be a predictor of depression. By surveying female Canadian undergraduate students, McDougall et al. [54] found that students who were sexually victimized and had non-consensual sex were at a higher chance of developing depression following their experience, emphasizing the importance of safeguarding mechanism for students at university campuses.

While the internet and social media can be great tools for maintaining a social relationship with classmates, pre-university friends and family members, it can have negative mental health effects. Excessive usage of social media and the internet during freshman year can be a predictor of developing SAD during the following years [55] . Students who have a higher dependence on the social media report a higher feeling of loneliness, which can result in SAD [56] . Students with internet addiction and excessive usage of social media are usually in first year of their degrees [55] , [56] which can reflect a lack of adjustment to university life and forming a social network. Also, students who use social media more often have a lower level of self-esteem and prefer to recreate their sense of self [56] , indicating an intertwined relationship between biopsychosocial factors in developing SAD among students.

Demographic status, ethnic and sexual minority groups including international Asian students, black and bisexual students were at an elevated risk of depression and suicidal behaviour [16] , [50] . The frequency of mental health is usually more common among ethnic minorities. For example, Turner et al. [20] showed that ethnic minority students report a higher level of anxiety and depression compared to their white peers; however, they do not ask for help as much. Other studies supported these findings by showing that students from ethnic and religious minorities, regardless of their country of origin and country in which they study, have a higher prevalence of anxiety and depression compared to their peers [50] . Also, students' expectations from university can be different among ethnic minorities students, and most of them do not have a sufficient understanding of the services that university can provide for them [40] .

Therefore, lack of support from family and university, adverse relationships with family, lack of engagement in social activities, sexual victimization, excessive social media usage, belonging to ethnic and religious minority groups, and stigma associated with the mental health are among risk factors for SAD in university students.

3.3.6. Economic factors

Students' family economic status can influence their mental health. A low family income and experiencing poverty can be predictors of SAD development during university years [22] , [50] , [57] , [58] . A higher family income can even ameliorate negative psychological experiences during childhood, which can have long-term negative consequences on the mental health of students once they enter university [57] . Also, experiencing poverty during childhood can have negative long-term consequences on adults, leading to SAD development during university life [58] .

Some students take up part-time job to partially fund their studies. Vaughn et al. [59] showed that relationship of employed students with their colleagues in the workplace could affect students' mental health; and those students who had a poor relationship with their colleagues had worse mental health. However, it is worth mentioning that a causal relationship was not established. It can be possible that students who have poor mental health cannot get along with their co-workers, resulting in an adverse working relationship.

Because of paying higher tuition fees and less access to scholarships and bursaries available, international students can have more financial problems, causing a higher degree of anxiety and depression compared to home students [60] .

Lack of adequate financial support, low family income and poverty during childhood are risk factors of SAD in students of undergraduate courses in developed and developing countries.

3.4. Stigma associated with mental health

While efforts have been put to reduce the stigma associated with receiving help for mental health problems, this still remains a challenge. For example, more than half of students who had SAD did not receive any help or treatment for their condition because of the stigma associated with mental health [19] , [61] . This is not related to the awareness of the availability of mental health resources which was ruled out by authors, as most of the students who did not receive any help for their mental health problem were aware of available help and support to them [19] .

Furthermore, the social stigma associated with receiving help for mental health problems was significantly associated with suicidal behaviour, acting as a preventive barrier to seek help (planning and attempt) [16] . Among students, those with a history of mental health problem such as veterans with PTSD are less likely to seek for help compared to non-veteran students [25] , making them more susceptible to struggling with untreated mental health.

4. Discussion

This review tried to identify and summarise risk factors associated with SAD in undergraduate students studying in developed and developing countries. The prevalence of SAD is high among undergraduate university students who study in developed and developing countries. Untreated SAD can lead to eating disorders, self-harm, suicide, social problems [28] . Similar to a complex society, differences exist among students leading to complicated risk factors causing SAD. Because different themes influencing SAD has been investigated as a distinct body of research by different literature, a concept map is created to demonstrate the relationship between various risk factors contributing to the development of SAD in undergraduate students in developed and developing countries. Figure 3 bridges risk factors concepts between different literature. For most students, entering university is a new step in their lives which is associated with certain challenges such as moving into independent accommodation, social identity, financial management, making decisions, and forming a social network. Different students have different needs depending on the stage of their degree, which needs to be fulfilled. For example, coping with a new university life style can be a challenging task for students who enter the university. This becomes more significant for students moving abroad for their studying who need to adapt to a new lifestyle, speak in a different language, and live away from their families. In agreement with this, different levels of anxiety and depression with different risk factors are observed among students as they progress in their degrees. On the other hand, students who are finishing their degrees can have SAD because of uncertainties about their future.

Students learn different modules in different degrees and have different abilities. Mastery of the subject can be a factor affecting students' sense of self-esteem, influencing their anxiety level and developing depressive symptoms. This partially can explain changes in risk factors observed as students' progress in their degrees. Final year students who adjust to the university environment and develop mastery in their subject can deal with academic pressure better compared to freshers who transform from secondary school life to university lifestyle.

Students can come with a varied and challenging background such as those who experienced household and domestic violence, sexual abuse, and child poverty which can make them susceptible to developing anxiety and depression once academic pressure is mounted. As universities are diverse environment which enrol students from different socioeconomic background and different cultures, universities need to identify risk factors for different students and have robust plans to tackle them to provide a fostering environment for future leaders of the society. Therefore, early mental health screening can help to identify those students who are at risk to provide them with special and additional mental health support. Students not only should be screened for their mental health state as they enter university, but also regular follow up check-ups should be conducted to monitor their conditions as they progress in their degrees to detect early signs of SAD.

University and academic staff can play a significant role in either exaggerating or ameliorating risk factors associated with anxiety and depression. While teachers and mentors can support students to cope with SAD, they can be a source of problem too by discriminating, bullying, and hampering students' progress.

Managing finance and expenses can be a challenging task for students who are stepping into an independent lifestyle and need to pay for their tuitions in addition to their maintenance fees. While some students have access to private funding, bursaries, and scholarships, other students receive loans which they need to pay back or have part-time jobs to meet their expenses. Students who work need to have a work-life balance and the time spent in their jobs can affect the quality of their education.

Fresher students try to establish their social network and might feel isolated, which can push them to excessive usage of social media to fill their social gap. While internet addiction and excessive usage of social media can have a negative impact on students' mental health, technology, such as mobile phone applications can be used in universities campuses to promote a healthier lifestyle and reducing risk factors among students. For example, many students refuse to receive face-to-face mental health counselling support during their anxiety and depression due to stigma associated with disclosure of mental health issues. Providing students with anonymized counselling services through mobile phone applications can be one way of delivering help to students at universities.

With the advent of social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, etc., more and more students rely on such networks for socialisation. While the internet and online platforms can have beneficial consequences for students, such as rapid access to a variety of online learning resources and keeping in contact with friends and families, excessive usage of social media and internet can have negative consequences on students' academic performance. A poor mental health state at the beginning of university life is a predictor of internet addiction later during the degree. Heavy reliance on the internet can be a coping mechanism for students with anxiety and depression to overcome their mental health problems.

As governments and educational bodies in developed and developing countries are emphasising recruitment of ethnic minority students to university to increase the range of equality and diversity among students, it is important to consider the mental health of those students in the university as well. Students in minority groups such as black, international Chinese and bisexual student report a higher level of anxiety and depression compared to other non-minority group students. This can be due to either pre-existing conditions which student experience before entering the university, and can be exacerbated during the university, or can be because of problems which can develop during university life.

Also, more mental health support is available in universities as the number of university students is increasing, and there is a better understanding of the importance of mental health in academia; however, the stigma associated with mental health has not changed proportionately.

While research and understanding of mental health have changed significantly over the past two decades and many more articles are present, risk factors associated with SAD remain unchanged.

One caveat with studies of mental health among student is that most studies have been conducted among medical and nursing students and neglected non-medical students. One potential explanation for the tendency to conduct depression surveys among medical students is the higher response rate as medical students are more willing to fill out the questionnaires and surveys. It is understandable that students studying medical subjects, who directly interact with the public and treating them once they enter the healthcare profession should have a reasonably sound mental health to be able to conduct their duties, but it does not justify neglecting the mental health of other students. Therefore, more research on mental health and risk factors associated with SAD of non-medical students is required in the future.

Another caveat with most mental health studies is that they are based on self-reports and surveys. Different people can have different perception and understanding of mental health and anxiety, and many confounding factors can influence the response of participants in the time of participation. Furthermore, students with severe mental health conditions are less likely to participate in any activity including surveys and questionnaires, leading to a non-response bias.

Another area which requires improvement in future studies of mental health is the categorisation of different types of depression and their severity. Depression and anxiety are a spectrum which can comprise of minor and major symptoms; however, most studies did not specify the scale of depression in their findings. Furthermore, while various risk factors were identified, a causal relationship between mental health and behaviours were not established.

While counselling services provided by universities in Western countries such as the UK and USA have increased over the past few years [62] , it is still not clear how effective such services are; therefore, more research is required to assess the effectiveness of counselling services at universities.

Therefore, a better understanding of the aetiology, associated factors is required for an effective intervention to reduce the disease incidence and prevalence among students in the population and providing them with a fostering environment to achieve their potential.

University undergraduate students are at a higher risk of developing SAD in developed and developing countries. Promoting the mental health of students is an important issue which should be addressed in the education and healthcare systems of developed and developing countries. Since students entering university are from different socioeconomic background, screening should be carried out early as students.

A personalized approach is required to assess mental health of different students. In addition, a majority of mental health risk factors can be related to the academic environment. A personalised, student-centred approach to include needs and requirements of different students from different background can help students to foster their talent to reach their full potential. Furthermore, more training should be provided for teaching and university staff to help students identify risk factors, and provide appropriate treatment.

5. Conclusion

Despite all the efforts over the past two decades to destigmatise mental health, the stigma associated with mental health is still a significant barrier for students, especially male students and students from ethnic and religious minorities to seek help for SAD treatment. Universities need to continue to destigmatise mental health in university campuses to enable students to receive more in campus support by providing designated time for positive metal health activities such as group exercise, physical activities, and counselling services. There is no shortage of athletic and group activities in form of clubs and social classes in most universities in developed and developing countries; however, more incentives such as athletic bursaries and prizes should be provided to students to encourage their participation in such activities which can act as protective factors against SAD development. Therefore, universities need to allocate more resources for sporting and social activities which can impact the mental health of students. Furthermore, an increase in mental health problems in universities has created a huge burden on university counselling services to meet the demands of students. More novel approaches, such as online counselling services can help universities to meet those increased demands.

Students in different years of studies deal with different risk factors from the time that they enter the university until they graduate, therefore, different coping strategies are required for students at different levels. Universities should be aware of these risk factors and implement measures to minimise those factors while providing mental health treatments to students.

Future studies are required to investigate long-term effects of experiencing SAD on students. A longitudinal study with a large randomly recruited sample size (different age, sex, degree of study, – socioeconomic status, etc.) is required to address how students' mental health change from entering the university until they graduate. Also, more extended follow up studies can be included to address the effect of depression and poor mental health on people's lives after they graduate from the university.

Abbreviations

Conflict of interest: All authors declare no conflicts of interest in this paper.

Popular Searches

- Back to school

- Why do I feel weird

- School programs

- Managing stress

- When you’re worried about a friend who doesn’t want help

Understanding Academic Stress in College

How can you tell if your college stress is unhealthy, signs you may need professional support, get more academic stress tips.

Share this resource

If you’re like most college students, you experience school-related stress. Stress isn’t always a bad thing. At manageable levels, it’s necessary and healthy because it keeps you motivated and pushes you to stay on track with studying and classwork.

But when stress, worry, and anxiety start to overwhelm you, it makes it harder to focus and get things done. National studies of college students have repeatedly found that the biggest stumbling blocks to academic success are emotional health challenges including:

- Not getting enough sleep

- Depression

Many things can create stress in college. Maybe you’re on a scholarship and you need to maintain certain grades to stay eligible. Maybe you’re worried about the financial burden of college on your family. You may even be the first person in your family to attend college, and it can be a lot of pressure to carry the weight of those expectations.

Stress seems like it should be typical, so it’s easy to dismiss it. You may even get down on yourself because you feel like you should handle it better. But research shows that feeling overwhelming school-related stress actually reduces your motivation to do the work, impacts your overall academic achievement, and increases your odds of dropping out.

Stress can also cause health problems such as depression, poor sleep, substance abuse, and anxiety.

For all those reasons—and just because you deserve as much balance in your life as possible—it’s important to figure out if your stress is making things harder than they need to be, affecting your health, or getting in the way of your life.

Then you can get help and learn ways to reduce the impact of stress on your life.

First identify what’s causing your stress.

- Is it a particular class or type of work?

- Is it an issue of time management and prioritization?

- Do you have too much on your plate?

- Is it due to family expectations or financial obligations?

Next think about how college stress affects you overall.

- Does it prevent you from sleeping?

- Does it make it take longer to do your work or paralyze you from even starting?

- Does it cause you to feel anxious, unwell, or depressed?

If any of that feels familiar, it’s time to find support to ease your stress and help you feel better. Check out these tips to figure out the best support and approach for you.

It’s important to be able to recognize when stress starts to become all-encompassing, affecting your overall mental health and well-being. Here are some signs you might need to get help:

- Insomnia or chronic trouble sleeping

- Inability to motivate

- Anxiety that results in physical symptoms such as hair loss, nail biting, or losing weight

- Depression, which may manifest as not wanting to spend time with friends, making excuses, or sleeping excessively

- Mood swings, such as bursting into tears or bouts of anger

Learn how to find professional mental health support at your school or elsewhere.

If you need help right now, text HOME to 741-741 for a free, confidential conversation with a trained counselor any time of day, or text or call 988 or use the chat function at 988lifeline.org .

If this is a medical emergency or there is immediate danger of harm, call 911 and explain that you need support for a mental health crisis.

Tips for Managing Academic Stress in College

How to Reduce Stress by Prioritizing and Getting Organized

5 Ways to Stay Calm When You’re Stressed About School

6 Ways to Take Care of Yourself During Exam Time

Related resources

3 steps to make it easier to ask for mental health support, how to identify and talk about your feelings, election stress: tips to manage anxious feelings about politics, search resource center.

If you or someone you know needs to talk to someone right now, text, call, or chat 988 for a free confidential conversation with a trained counselor 24/7.

You can also contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741-741.

If this is a medical emergency or if there is immediate danger of harm, call 911 and explain that you need support for a mental health crisis.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Health & Nursing

Courses and certificates.

- Bachelor's Degrees

- View all Business Bachelor's Degrees

- Business Management – B.S. Business Administration

- Healthcare Administration – B.S.

- Human Resource Management – B.S. Business Administration

- Information Technology Management – B.S. Business Administration

- Marketing – B.S. Business Administration

- Accounting – B.S. Business Administration

- Finance – B.S.

- Supply Chain and Operations Management – B.S.

- Accelerated Information Technology Bachelor's and Master's Degree (from the School of Technology)

- Health Information Management – B.S. (from the Leavitt School of Health)

Master's Degrees

- View all Business Master's Degrees

- Master of Business Administration (MBA)

- MBA Information Technology Management

- MBA Healthcare Management

- Management and Leadership – M.S.

- Accounting – M.S.

- Marketing – M.S.

- Human Resource Management – M.S.

- Master of Healthcare Administration (from the Leavitt School of Health)

- Data Analytics – M.S. (from the School of Technology)

- Information Technology Management – M.S. (from the School of Technology)

- Education Technology and Instructional Design – M.Ed. (from the School of Education)

Certificates

- Supply Chain

- Accounting Fundamentals

- View all Business Degrees

Bachelor's Preparing For Licensure

- View all Education Bachelor's Degrees

- Elementary Education – B.A.

- Special Education and Elementary Education (Dual Licensure) – B.A.

- Special Education (Mild-to-Moderate) – B.A.

- Mathematics Education (Middle Grades) – B.S.

- Mathematics Education (Secondary)– B.S.

- Science Education (Middle Grades) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Chemistry) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Physics) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Biological Sciences) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Earth Science)– B.S.

- View all Education Degrees

Bachelor of Arts in Education Degrees

- Educational Studies – B.A.

Master of Science in Education Degrees

- View all Education Master's Degrees

- Curriculum and Instruction – M.S.

- Educational Leadership – M.S.

- Education Technology and Instructional Design – M.Ed.

Master's Preparing for Licensure

- Teaching, Elementary Education – M.A.

- Teaching, English Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- Teaching, Mathematics Education (Middle Grades) – M.A.

- Teaching, Mathematics Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- Teaching, Science Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- Teaching, Special Education (K-12) – M.A.

Licensure Information

- State Teaching Licensure Information

Master's Degrees for Teachers

- Mathematics Education (K-6) – M.A.

- Mathematics Education (Middle Grade) – M.A.

- Mathematics Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- English Language Learning (PreK-12) – M.A.

- Endorsement Preparation Program, English Language Learning (PreK-12)

- Science Education (Middle Grades) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Chemistry) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Physics) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Biological Sciences) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Earth Science)– M.A.

- View all Technology Bachelor's Degrees

- Cloud Computing – B.S.

- Computer Science – B.S.

- Cybersecurity and Information Assurance – B.S.

- Data Analytics – B.S.

- Information Technology – B.S.

- Network Engineering and Security – B.S.

- Software Engineering – B.S.

- Accelerated Information Technology Bachelor's and Master's Degree

- Information Technology Management – B.S. Business Administration (from the School of Business)

- View all Technology Master's Degrees

- Cybersecurity and Information Assurance – M.S.

- Data Analytics – M.S.

- Information Technology Management – M.S.

- MBA Information Technology Management (from the School of Business)

- Full Stack Engineering

- Web Application Deployment and Support

- Front End Web Development

- Back End Web Development

3rd Party Certifications

- IT Certifications Included in WGU Degrees

- View all Technology Degrees

- View all Health & Nursing Bachelor's Degrees

- Nursing (RN-to-BSN online) – B.S.

- Nursing (Prelicensure) – B.S. (Available in select states)

- Health Information Management – B.S.

- Health and Human Services – B.S.

- Psychology – B.S.

- Health Science – B.S.

- Healthcare Administration – B.S. (from the School of Business)

- View all Nursing Post-Master's Certificates

- Nursing Education—Post-Master's Certificate

- Nursing Leadership and Management—Post-Master's Certificate

- Family Nurse Practitioner—Post-Master's Certificate

- Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner —Post-Master's Certificate

- View all Health & Nursing Degrees

- View all Nursing & Health Master's Degrees

- Nursing – Education (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Leadership and Management (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Nursing Informatics (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Family Nurse Practitioner (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S. (Available in select states)

- Nursing – Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S. (Available in select states)

- Nursing – Education (RN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Leadership and Management (RN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Nursing Informatics (RN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Master of Healthcare Administration

- Master of Public Health

- MBA Healthcare Management (from the School of Business)

- Business Leadership (with the School of Business)

- Supply Chain (with the School of Business)

- Accounting Fundamentals (with the School of Business)

- Back End Web Development (with the School of Technology)

- Front End Web Development (with the School of Technology)

- Web Application Deployment and Support (with the School of Technology)

- Full Stack Engineering (with the School of Technology)

- Single Courses

- Course Bundles

Apply for Admission

Admission requirements.

- New Students

- WGU Returning Graduates

- WGU Readmission

- Enrollment Checklist

- Accessibility

- Accommodation Request

- School of Education Admission Requirements

- School of Business Admission Requirements

- School of Technology Admission Requirements

- Leavitt School of Health Admission Requirements

Additional Requirements

- Computer Requirements

- No Standardized Testing

- Clinical and Student Teaching Information

Transferring

- FAQs about Transferring

- Transfer to WGU

- Transferrable Certifications

- Request WGU Transcripts

- International Transfer Credit

- Tuition and Fees

- Financial Aid

- Scholarships

Other Ways to Pay for School

- Tuition—School of Business

- Tuition—School of Education

- Tuition—School of Technology

- Tuition—Leavitt School of Health

- Your Financial Obligations

- Tuition Comparison

- Applying for Financial Aid

- State Grants

- Consumer Information Guide

- Responsible Borrowing Initiative

- Higher Education Relief Fund

FAFSA Support

- Net Price Calculator

- FAFSA Simplification

- See All Scholarships

- Military Scholarships

- State Scholarships

- Scholarship FAQs

Payment Options

- Payment Plans

- Corporate Reimbursement

- Current Student Hardship Assistance

- Military Tuition Assistance

WGU Experience

- How You'll Learn

- Scheduling/Assessments

- Accreditation

- Student Support/Faculty

- Military Students

- Part-Time Options

- Virtual Military Education Resource Center

- Student Outcomes

- Return on Investment

- Students and Gradutes

- Career Growth

- Student Resources

- Communities

- Testimonials

- Career Guides

- Skills Guides

- Online Degrees

- All Degrees

- Explore Your Options

Admissions & Transfers

- Admissions Overview

Tuition & Financial Aid

- Student Success

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Military and Veterans

- Commencement

- Careers at WGU

- Advancement & Giving

- Partnering with WGU

Stress in College Students: How To Cope

- See More Tags

A college student's guide to stress.

College is an exciting time, full of new challenges that continually drive you to expand your horizons. While some of these experiences can be thrilling, others may simply leave you feeling stressed. In fact, many college students feel stress while going to school. Only 1.6 percent of undergraduates reported that they felt no stress in the last 12 months, according to the National College Health Assessment (NCHA).

Being able to manage stress is crucial for your academic success and personal well-being in college. Luckily, this guide from Western Governors University will provide you with information about how to recognize different kinds of stress, various sources of stress for college students, as well as tips for coping in a healthy way. If you are able to identify and understand stress, you will be able to ensure your time as a student is rewarding and enjoyable.

What is stress?

Stress is a normal and necessary part of life. It is your fight-or-flight response to challenges you see in the world. This natural reaction has certain physical effects on the body to allow you to better handle these challenges, such as increased heart rate and blood circulation. While it can manifest differently for each individual, the National Institute of Mental Health notes that everyone feels stress at some point in their lives, regardless of age, gender, or circumstance.

Though it is a universal human experience, the American Institute of Stress (AIS) notes that defining and measuring stress is difficult because “there has been no definition of stress that everyone accepts” and “people have very different ideas with respect to their definition of stress.” They also state that a definition of stress is incomplete without mention of good stress (called eustress), its physical effects, or the body’s instinctive fight-or-flight response.

Researcher Andrew Baum , however, created a succinct, unique definition. He determines that stress is any “emotional experience accompanied by predictable biochemical, physiological and behavioral changes.” For the purposes of this guide, we will use Baum’s definition of stress.

Acute stress.

According to the American Psychological Association (APA), acute stress is the most common type of stress that every person will experience during the course of their life. It arises quickly in response to unexpected or alarming events to help you better handle the situation at hand. Typically, it fades quickly, either on its own or once the stressful event is over.

Acute stress doesn’t often lead to serious health problems. In certain situations, it can actually be a positive experience; for example, riding a roller coaster can cause acute stress, but in a thrilling way.

This type of stress occurs frequently and is easy to identify. Some signs of acute stress include:

Stomach pain, such as heartburn, diarrhea, or acid stomach.

Heightened blood pressure and heartbeat.

Shortness of breath or chest pain.

Headaches, back pain, jaw pain.

Because it is so common and lasts for a short amount of time, acute stress is usually simple to manage and treat.

Episodic stress.

When acute stress occurs frequently, it is classified as episodic or episodic acute stress. People who suffer from episodic stress are almost always in “crisis mode,” are often irritable and anxious, and may be prone to constant worrying. Essentially, people with episodic stress are often overwhelmed by it and have difficulty managing it.

Symptoms of episodic stress are the same as acute stress, but they can be more extreme or occur constantly. Some signs of long-term episodic stress according to the APA are:

Constant headaches or migraines.

Hypertension.

Heart disease.