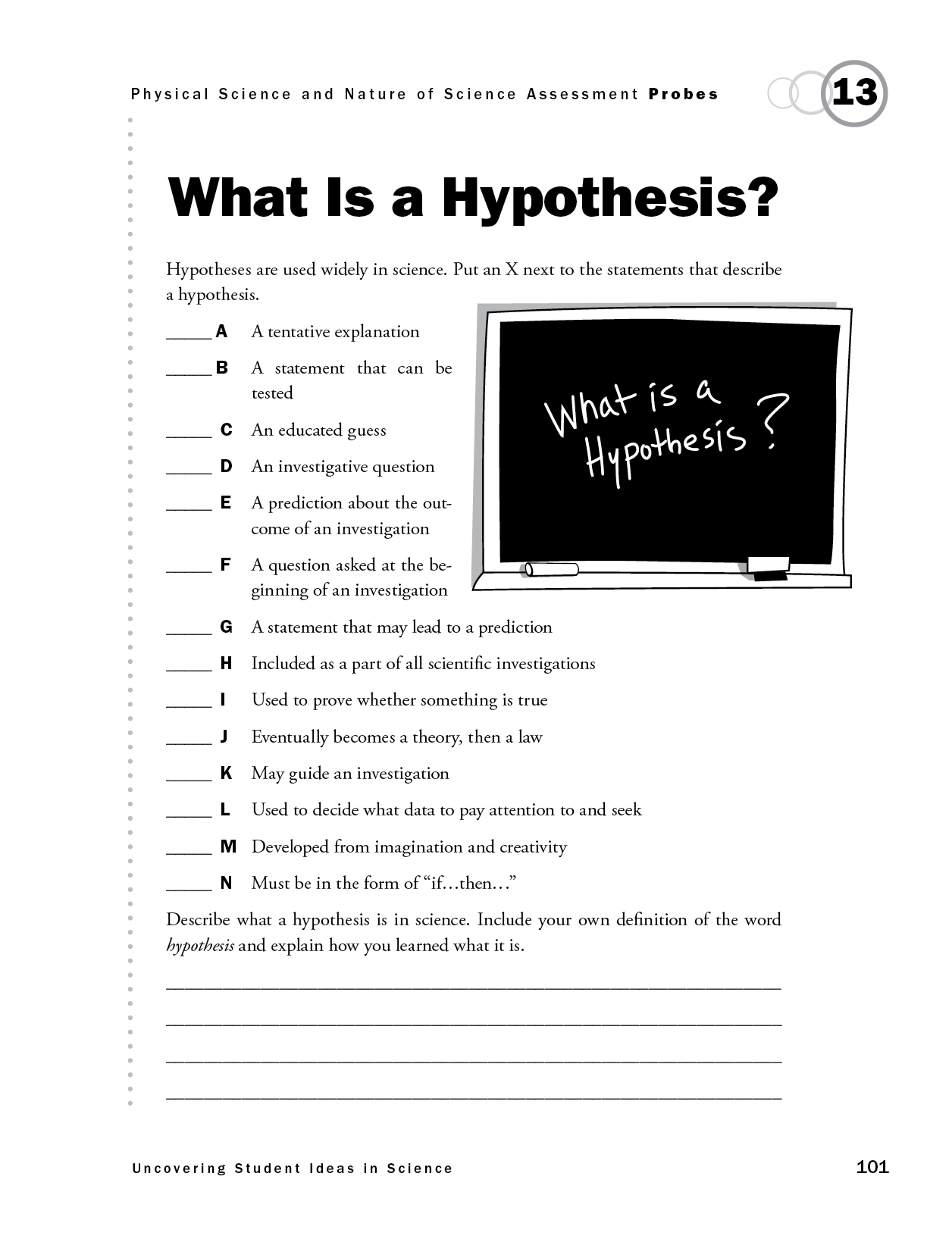

hypothesis explanation observation

What is a scientific hypothesis.

It's the initial building block in the scientific method.

Hypothesis basics

What makes a hypothesis testable.

- Types of hypotheses

- Hypothesis versus theory

Additional resources

Bibliography.

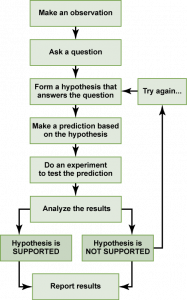

A scientific hypothesis is a tentative, testable explanation for a phenomenon in the natural world. It's the initial building block in the scientific method . Many describe it as an "educated guess" based on prior knowledge and observation. While this is true, a hypothesis is more informed than a guess. While an "educated guess" suggests a random prediction based on a person's expertise, developing a hypothesis requires active observation and background research.

The basic idea of a hypothesis is that there is no predetermined outcome. For a solution to be termed a scientific hypothesis, it has to be an idea that can be supported or refuted through carefully crafted experimentation or observation. This concept, called falsifiability and testability, was advanced in the mid-20th century by Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper in his famous book "The Logic of Scientific Discovery" (Routledge, 1959).

A key function of a hypothesis is to derive predictions about the results of future experiments and then perform those experiments to see whether they support the predictions.

A hypothesis is usually written in the form of an if-then statement, which gives a possibility (if) and explains what may happen because of the possibility (then). The statement could also include "may," according to California State University, Bakersfield .

Here are some examples of hypothesis statements:

- If garlic repels fleas, then a dog that is given garlic every day will not get fleas.

- If sugar causes cavities, then people who eat a lot of candy may be more prone to cavities.

- If ultraviolet light can damage the eyes, then maybe this light can cause blindness.

A useful hypothesis should be testable and falsifiable. That means that it should be possible to prove it wrong. A theory that can't be proved wrong is nonscientific, according to Karl Popper's 1963 book " Conjectures and Refutations ."

An example of an untestable statement is, "Dogs are better than cats." That's because the definition of "better" is vague and subjective. However, an untestable statement can be reworded to make it testable. For example, the previous statement could be changed to this: "Owning a dog is associated with higher levels of physical fitness than owning a cat." With this statement, the researcher can take measures of physical fitness from dog and cat owners and compare the two.

Types of scientific hypotheses

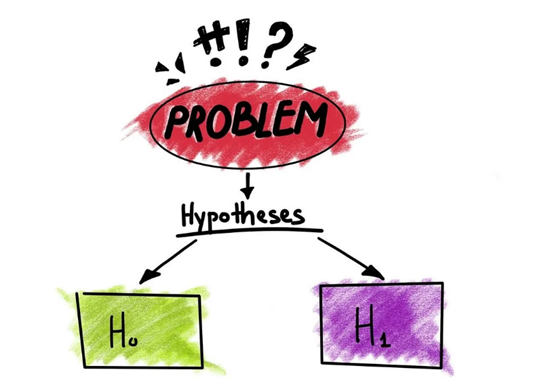

In an experiment, researchers generally state their hypotheses in two ways. The null hypothesis predicts that there will be no relationship between the variables tested, or no difference between the experimental groups. The alternative hypothesis predicts the opposite: that there will be a difference between the experimental groups. This is usually the hypothesis scientists are most interested in, according to the University of Miami .

For example, a null hypothesis might state, "There will be no difference in the rate of muscle growth between people who take a protein supplement and people who don't." The alternative hypothesis would state, "There will be a difference in the rate of muscle growth between people who take a protein supplement and people who don't."

If the results of the experiment show a relationship between the variables, then the null hypothesis has been rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis, according to the book " Research Methods in Psychology " (BCcampus, 2015).

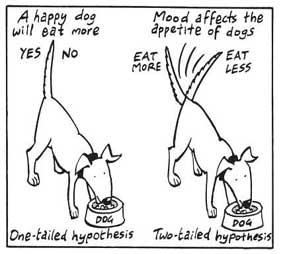

There are other ways to describe an alternative hypothesis. The alternative hypothesis above does not specify a direction of the effect, only that there will be a difference between the two groups. That type of prediction is called a two-tailed hypothesis. If a hypothesis specifies a certain direction — for example, that people who take a protein supplement will gain more muscle than people who don't — it is called a one-tailed hypothesis, according to William M. K. Trochim , a professor of Policy Analysis and Management at Cornell University.

Sometimes, errors take place during an experiment. These errors can happen in one of two ways. A type I error is when the null hypothesis is rejected when it is true. This is also known as a false positive. A type II error occurs when the null hypothesis is not rejected when it is false. This is also known as a false negative, according to the University of California, Berkeley .

A hypothesis can be rejected or modified, but it can never be proved correct 100% of the time. For example, a scientist can form a hypothesis stating that if a certain type of tomato has a gene for red pigment, that type of tomato will be red. During research, the scientist then finds that each tomato of this type is red. Though the findings confirm the hypothesis, there may be a tomato of that type somewhere in the world that isn't red. Thus, the hypothesis is true, but it may not be true 100% of the time.

Scientific theory vs. scientific hypothesis

The best hypotheses are simple. They deal with a relatively narrow set of phenomena. But theories are broader; they generally combine multiple hypotheses into a general explanation for a wide range of phenomena, according to the University of California, Berkeley . For example, a hypothesis might state, "If animals adapt to suit their environments, then birds that live on islands with lots of seeds to eat will have differently shaped beaks than birds that live on islands with lots of insects to eat." After testing many hypotheses like these, Charles Darwin formulated an overarching theory: the theory of evolution by natural selection.

"Theories are the ways that we make sense of what we observe in the natural world," Tanner said. "Theories are structures of ideas that explain and interpret facts."

- Read more about writing a hypothesis, from the American Medical Writers Association.

- Find out why a hypothesis isn't always necessary in science, from The American Biology Teacher.

- Learn about null and alternative hypotheses, from Prof. Essa on YouTube .

Encyclopedia Britannica. Scientific Hypothesis. Jan. 13, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/science/scientific-hypothesis

Karl Popper, "The Logic of Scientific Discovery," Routledge, 1959.

California State University, Bakersfield, "Formatting a testable hypothesis." https://www.csub.edu/~ddodenhoff/Bio100/Bio100sp04/formattingahypothesis.htm

Karl Popper, "Conjectures and Refutations," Routledge, 1963.

Price, P., Jhangiani, R., & Chiang, I., "Research Methods of Psychology — 2nd Canadian Edition," BCcampus, 2015.

University of Miami, "The Scientific Method" http://www.bio.miami.edu/dana/161/evolution/161app1_scimethod.pdf

William M.K. Trochim, "Research Methods Knowledge Base," https://conjointly.com/kb/hypotheses-explained/

University of California, Berkeley, "Multiple Hypothesis Testing and False Discovery Rate" https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~hhuang/STAT141/Lecture-FDR.pdf

University of California, Berkeley, "Science at multiple levels" https://undsci.berkeley.edu/article/0_0_0/howscienceworks_19

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Bizarre evolutionary roots of Africa's iconic upside-down baobab trees revealed

Snake Island: The isle writhing with vipers where only Brazilian military and scientists are allowed

Newfound autoimmune syndrome tied to COVID-19 can trigger deadly lung scarring

Most Popular

- 2 'It was not a peaceful crossing': Hannibal's troops linked to devastating fire 2,200 years ago in Spain

- 3 Snake Island: The isle writhing with vipers where only Brazilian military and scientists are allowed

- 4 Newfound 'glitch' in Einstein's relativity could rewrite the rules of the universe, study suggests

- 5 Scientists prove 'quantum theory' that could lead to ultrafast magnetic computing

- 5 Alien 'Dyson sphere' megastructures could surround at least 7 stars in our galaxy, new studies suggest

- Privacy Policy

Home » What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

- Table of Contents

Definition:

Hypothesis is an educated guess or proposed explanation for a phenomenon, based on some initial observations or data. It is a tentative statement that can be tested and potentially proven or disproven through further investigation and experimentation.

Hypothesis is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments and the collection and analysis of data. It is an essential element of the scientific method, as it allows researchers to make predictions about the outcome of their experiments and to test those predictions to determine their accuracy.

Types of Hypothesis

Types of Hypothesis are as follows:

Research Hypothesis

A research hypothesis is a statement that predicts a relationship between variables. It is usually formulated as a specific statement that can be tested through research, and it is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is no significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as a starting point for testing the research hypothesis, and if the results of the study reject the null hypothesis, it suggests that there is a significant difference or relationship between variables.

Alternative Hypothesis

An alternative hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is a significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as an alternative to the null hypothesis and is tested against the null hypothesis to determine which statement is more accurate.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the direction of the relationship between variables. For example, a researcher might predict that increasing the amount of exercise will result in a decrease in body weight.

Non-directional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the relationship between variables but does not specify the direction. For example, a researcher might predict that there is a relationship between the amount of exercise and body weight, but they do not specify whether increasing or decreasing exercise will affect body weight.

Statistical Hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is a statement that assumes a particular statistical model or distribution for the data. It is often used in statistical analysis to test the significance of a particular result.

Composite Hypothesis

A composite hypothesis is a statement that assumes more than one condition or outcome. It can be divided into several sub-hypotheses, each of which represents a different possible outcome.

Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is a statement that is based on observed phenomena or data. It is often used in scientific research to develop theories or models that explain the observed phenomena.

Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement that assumes only one outcome or condition. It is often used in scientific research to test a single variable or factor.

Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is a statement that assumes multiple outcomes or conditions. It is often used in scientific research to test the effects of multiple variables or factors on a particular outcome.

Applications of Hypothesis

Hypotheses are used in various fields to guide research and make predictions about the outcomes of experiments or observations. Here are some examples of how hypotheses are applied in different fields:

- Science : In scientific research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain natural phenomena. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular variable on a natural system, such as the effects of climate change on an ecosystem.

- Medicine : In medical research, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of treatments and therapies for specific conditions. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new drug on a particular disease.

- Psychology : In psychology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of human behavior and cognition. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular stimulus on the brain or behavior.

- Sociology : In sociology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of social phenomena, such as the effects of social structures or institutions on human behavior. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of income inequality on crime rates.

- Business : In business research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain business phenomena, such as consumer behavior or market trends. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new marketing campaign on consumer buying behavior.

- Engineering : In engineering, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of new technologies or designs. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the efficiency of a new solar panel design.

How to write a Hypothesis

Here are the steps to follow when writing a hypothesis:

Identify the Research Question

The first step is to identify the research question that you want to answer through your study. This question should be clear, specific, and focused. It should be something that can be investigated empirically and that has some relevance or significance in the field.

Conduct a Literature Review

Before writing your hypothesis, it’s essential to conduct a thorough literature review to understand what is already known about the topic. This will help you to identify the research gap and formulate a hypothesis that builds on existing knowledge.

Determine the Variables

The next step is to identify the variables involved in the research question. A variable is any characteristic or factor that can vary or change. There are two types of variables: independent and dependent. The independent variable is the one that is manipulated or changed by the researcher, while the dependent variable is the one that is measured or observed as a result of the independent variable.

Formulate the Hypothesis

Based on the research question and the variables involved, you can now formulate your hypothesis. A hypothesis should be a clear and concise statement that predicts the relationship between the variables. It should be testable through empirical research and based on existing theory or evidence.

Write the Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is the opposite of the alternative hypothesis, which is the hypothesis that you are testing. The null hypothesis states that there is no significant difference or relationship between the variables. It is important to write the null hypothesis because it allows you to compare your results with what would be expected by chance.

Refine the Hypothesis

After formulating the hypothesis, it’s important to refine it and make it more precise. This may involve clarifying the variables, specifying the direction of the relationship, or making the hypothesis more testable.

Examples of Hypothesis

Here are a few examples of hypotheses in different fields:

- Psychology : “Increased exposure to violent video games leads to increased aggressive behavior in adolescents.”

- Biology : “Higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere will lead to increased plant growth.”

- Sociology : “Individuals who grow up in households with higher socioeconomic status will have higher levels of education and income as adults.”

- Education : “Implementing a new teaching method will result in higher student achievement scores.”

- Marketing : “Customers who receive a personalized email will be more likely to make a purchase than those who receive a generic email.”

- Physics : “An increase in temperature will cause an increase in the volume of a gas, assuming all other variables remain constant.”

- Medicine : “Consuming a diet high in saturated fats will increase the risk of developing heart disease.”

Purpose of Hypothesis

The purpose of a hypothesis is to provide a testable explanation for an observed phenomenon or a prediction of a future outcome based on existing knowledge or theories. A hypothesis is an essential part of the scientific method and helps to guide the research process by providing a clear focus for investigation. It enables scientists to design experiments or studies to gather evidence and data that can support or refute the proposed explanation or prediction.

The formulation of a hypothesis is based on existing knowledge, observations, and theories, and it should be specific, testable, and falsifiable. A specific hypothesis helps to define the research question, which is important in the research process as it guides the selection of an appropriate research design and methodology. Testability of the hypothesis means that it can be proven or disproven through empirical data collection and analysis. Falsifiability means that the hypothesis should be formulated in such a way that it can be proven wrong if it is incorrect.

In addition to guiding the research process, the testing of hypotheses can lead to new discoveries and advancements in scientific knowledge. When a hypothesis is supported by the data, it can be used to develop new theories or models to explain the observed phenomenon. When a hypothesis is not supported by the data, it can help to refine existing theories or prompt the development of new hypotheses to explain the phenomenon.

When to use Hypothesis

Here are some common situations in which hypotheses are used:

- In scientific research , hypotheses are used to guide the design of experiments and to help researchers make predictions about the outcomes of those experiments.

- In social science research , hypotheses are used to test theories about human behavior, social relationships, and other phenomena.

- I n business , hypotheses can be used to guide decisions about marketing, product development, and other areas. For example, a hypothesis might be that a new product will sell well in a particular market, and this hypothesis can be tested through market research.

Characteristics of Hypothesis

Here are some common characteristics of a hypothesis:

- Testable : A hypothesis must be able to be tested through observation or experimentation. This means that it must be possible to collect data that will either support or refute the hypothesis.

- Falsifiable : A hypothesis must be able to be proven false if it is not supported by the data. If a hypothesis cannot be falsified, then it is not a scientific hypothesis.

- Clear and concise : A hypothesis should be stated in a clear and concise manner so that it can be easily understood and tested.

- Based on existing knowledge : A hypothesis should be based on existing knowledge and research in the field. It should not be based on personal beliefs or opinions.

- Specific : A hypothesis should be specific in terms of the variables being tested and the predicted outcome. This will help to ensure that the research is focused and well-designed.

- Tentative: A hypothesis is a tentative statement or assumption that requires further testing and evidence to be confirmed or refuted. It is not a final conclusion or assertion.

- Relevant : A hypothesis should be relevant to the research question or problem being studied. It should address a gap in knowledge or provide a new perspective on the issue.

Advantages of Hypothesis

Hypotheses have several advantages in scientific research and experimentation:

- Guides research: A hypothesis provides a clear and specific direction for research. It helps to focus the research question, select appropriate methods and variables, and interpret the results.

- Predictive powe r: A hypothesis makes predictions about the outcome of research, which can be tested through experimentation. This allows researchers to evaluate the validity of the hypothesis and make new discoveries.

- Facilitates communication: A hypothesis provides a common language and framework for scientists to communicate with one another about their research. This helps to facilitate the exchange of ideas and promotes collaboration.

- Efficient use of resources: A hypothesis helps researchers to use their time, resources, and funding efficiently by directing them towards specific research questions and methods that are most likely to yield results.

- Provides a basis for further research: A hypothesis that is supported by data provides a basis for further research and exploration. It can lead to new hypotheses, theories, and discoveries.

- Increases objectivity: A hypothesis can help to increase objectivity in research by providing a clear and specific framework for testing and interpreting results. This can reduce bias and increase the reliability of research findings.

Limitations of Hypothesis

Some Limitations of the Hypothesis are as follows:

- Limited to observable phenomena: Hypotheses are limited to observable phenomena and cannot account for unobservable or intangible factors. This means that some research questions may not be amenable to hypothesis testing.

- May be inaccurate or incomplete: Hypotheses are based on existing knowledge and research, which may be incomplete or inaccurate. This can lead to flawed hypotheses and erroneous conclusions.

- May be biased: Hypotheses may be biased by the researcher’s own beliefs, values, or assumptions. This can lead to selective interpretation of data and a lack of objectivity in research.

- Cannot prove causation: A hypothesis can only show a correlation between variables, but it cannot prove causation. This requires further experimentation and analysis.

- Limited to specific contexts: Hypotheses are limited to specific contexts and may not be generalizable to other situations or populations. This means that results may not be applicable in other contexts or may require further testing.

- May be affected by chance : Hypotheses may be affected by chance or random variation, which can obscure or distort the true relationship between variables.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.34(45); 2019 Nov 25

Scientific Hypotheses: Writing, Promoting, and Predicting Implications

Armen yuri gasparyan.

1 Departments of Rheumatology and Research and Development, Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust (Teaching Trust of the University of Birmingham, UK), Russells Hall Hospital, Dudley, West Midlands, UK.

Lilit Ayvazyan

2 Department of Medical Chemistry, Yerevan State Medical University, Yerevan, Armenia.

Ulzhan Mukanova

3 Department of Surgical Disciplines, South Kazakhstan Medical Academy, Shymkent, Kazakhstan.

Marlen Yessirkepov

4 Department of Biology and Biochemistry, South Kazakhstan Medical Academy, Shymkent, Kazakhstan.

George D. Kitas

5 Arthritis Research UK Epidemiology Unit, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK.

Scientific hypotheses are essential for progress in rapidly developing academic disciplines. Proposing new ideas and hypotheses require thorough analyses of evidence-based data and predictions of the implications. One of the main concerns relates to the ethical implications of the generated hypotheses. The authors may need to outline potential benefits and limitations of their suggestions and target widely visible publication outlets to ignite discussion by experts and start testing the hypotheses. Not many publication outlets are currently welcoming hypotheses and unconventional ideas that may open gates to criticism and conservative remarks. A few scholarly journals guide the authors on how to structure hypotheses. Reflecting on general and specific issues around the subject matter is often recommended for drafting a well-structured hypothesis article. An analysis of influential hypotheses, presented in this article, particularly Strachan's hygiene hypothesis with global implications in the field of immunology and allergy, points to the need for properly interpreting and testing new suggestions. Envisaging the ethical implications of the hypotheses should be considered both by authors and journal editors during the writing and publishing process.

INTRODUCTION

We live in times of digitization that radically changes scientific research, reporting, and publishing strategies. Researchers all over the world are overwhelmed with processing large volumes of information and searching through numerous online platforms, all of which make the whole process of scholarly analysis and synthesis complex and sophisticated.

Current research activities are diversifying to combine scientific observations with analysis of facts recorded by scholars from various professional backgrounds. 1 Citation analyses and networking on social media are also becoming essential for shaping research and publishing strategies globally. 2 Learning specifics of increasingly interdisciplinary research studies and acquiring information facilitation skills aid researchers in formulating innovative ideas and predicting developments in interrelated scientific fields.

Arguably, researchers are currently offered more opportunities than in the past for generating new ideas by performing their routine laboratory activities, observing individual cases and unusual developments, and critically analyzing published scientific facts. What they need at the start of their research is to formulate a scientific hypothesis that revisits conventional theories, real-world processes, and related evidence to propose new studies and test ideas in an ethical way. 3 Such a hypothesis can be of most benefit if published in an ethical journal with wide visibility and exposure to relevant online databases and promotion platforms.

Although hypotheses are crucially important for the scientific progress, only few highly skilled researchers formulate and eventually publish their innovative ideas per se . Understandably, in an increasingly competitive research environment, most authors would prefer to prioritize their ideas by discussing and conducting tests in their own laboratories or clinical departments, and publishing research reports afterwards. However, there are instances when simple observations and research studies in a single center are not capable of explaining and testing new groundbreaking ideas. Formulating hypothesis articles first and calling for multicenter and interdisciplinary research can be a solution in such instances, potentially launching influential scientific directions, if not academic disciplines.

The aim of this article is to overview the importance and implications of infrequently published scientific hypotheses that may open new avenues of thinking and research.

Despite the seemingly established views on innovative ideas and hypotheses as essential research tools, no structured definition exists to tag the term and systematically track related articles. In 1973, the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) of the U.S. National Library of Medicine introduced “Research Design” as a structured keyword that referred to the importance of collecting data and properly testing hypotheses, and indirectly linked the term to ethics, methods and standards, among many other subheadings.

One of the experts in the field defines “hypothesis” as a well-argued analysis of available evidence to provide a realistic (scientific) explanation of existing facts, fill gaps in public understanding of sophisticated processes, and propose a new theory or a test. 4 A hypothesis can be proven wrong partially or entirely. However, even such an erroneous hypothesis may influence progress in science by initiating professional debates that help generate more realistic ideas. The main ethical requirement for hypothesis authors is to be honest about the limitations of their suggestions. 5

EXAMPLES OF INFLUENTIAL SCIENTIFIC HYPOTHESES

Daily routine in a research laboratory may lead to groundbreaking discoveries provided the daily accounts are comprehensively analyzed and reproduced by peers. The discovery of penicillin by Sir Alexander Fleming (1928) can be viewed as a prime example of such discoveries that introduced therapies to treat staphylococcal and streptococcal infections and modulate blood coagulation. 6 , 7 Penicillin got worldwide recognition due to the inventor's seminal works published by highly prestigious and widely visible British journals, effective ‘real-world’ antibiotic therapy of pneumonia and wounds during World War II, and euphoric media coverage. 8 In 1945, Fleming, Florey and Chain got a much deserved Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery that led to the mass production of the wonder drug in the U.S. and ‘real-world practice’ that tested the use of penicillin. What remained globally unnoticed is that Zinaida Yermolyeva, the outstanding Soviet microbiologist, created the Soviet penicillin, which turned out to be more effective than the Anglo-American penicillin and entered mass production in 1943; that year marked the turning of the tide of the Great Patriotic War. 9 One of the reasons of the widely unnoticed discovery of Zinaida Yermolyeva is that her works were published exclusively by local Russian (Soviet) journals.

The past decades have been marked by an unprecedented growth of multicenter and global research studies involving hundreds and thousands of human subjects. This trend is shaped by an increasing number of reports on clinical trials and large cohort studies that create a strong evidence base for practice recommendations. Mega-studies may help generate and test large-scale hypotheses aiming to solve health issues globally. Properly designed epidemiological studies, for example, may introduce clarity to the hygiene hypothesis that was originally proposed by David Strachan in 1989. 10 David Strachan studied the epidemiology of hay fever in a cohort of 17,414 British children and concluded that declining family size and improved personal hygiene had reduced the chances of cross infections in families, resulting in epidemics of atopic disease in post-industrial Britain. Over the past four decades, several related hypotheses have been proposed to expand the potential role of symbiotic microorganisms and parasites in the development of human physiological immune responses early in life and protection from allergic and autoimmune diseases later on. 11 , 12 Given the popularity and the scientific importance of the hygiene hypothesis, it was introduced as a MeSH term in 2012. 13

Hypotheses can be proposed based on an analysis of recorded historic events that resulted in mass migrations and spreading of certain genetic diseases. As a prime example, familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), the prototype periodic fever syndrome, is believed to spread from Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean region and all over Europe due to migrations and religious prosecutions millennia ago. 14 Genetic mutations spearing mild clinical forms of FMF are hypothesized to emerge and persist in the Mediterranean region as protective factors against more serious infectious diseases, particularly tuberculosis, historically common in that part of the world. 15 The speculations over the advantages of carrying the MEditerranean FeVer (MEFV) gene are further strengthened by recorded low mortality rates from tuberculosis among FMF patients of different nationalities living in Tunisia in the first half of the 20th century. 16

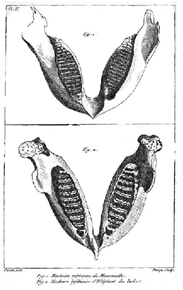

Diagnostic hypotheses shedding light on peculiarities of diseases throughout the history of mankind can be formulated using artefacts, particularly historic paintings. 17 Such paintings may reveal joint deformities and disfigurements due to rheumatic diseases in individual subjects. A series of paintings with similar signs of pathological conditions interpreted in a historic context may uncover mysteries of epidemics of certain diseases, which is the case with Ruben's paintings depicting signs of rheumatic hands and making some doctors to believe that rheumatoid arthritis was common in Europe in the 16th and 17th century. 18

WRITING SCIENTIFIC HYPOTHESES

There are author instructions of a few journals that specifically guide how to structure, format, and make submissions categorized as hypotheses attractive. One of the examples is presented by Med Hypotheses , the flagship journal in its field with more than four decades of publishing and influencing hypothesis authors globally. However, such guidance is not based on widely discussed, implemented, and approved reporting standards, which are becoming mandatory for all scholarly journals.

Generating new ideas and scientific hypotheses is a sophisticated task since not all researchers and authors are skilled to plan, conduct, and interpret various research studies. Some experience with formulating focused research questions and strong working hypotheses of original research studies is definitely helpful for advancing critical appraisal skills. However, aspiring authors of scientific hypotheses may need something different, which is more related to discerning scientific facts, pooling homogenous data from primary research works, and synthesizing new information in a systematic way by analyzing similar sets of articles. To some extent, this activity is reminiscent of writing narrative and systematic reviews. As in the case of reviews, scientific hypotheses need to be formulated on the basis of comprehensive search strategies to retrieve all available studies on the topics of interest and then synthesize new information selectively referring to the most relevant items. One of the main differences between scientific hypothesis and review articles relates to the volume of supportive literature sources ( Table 1 ). In fact, hypothesis is usually formulated by referring to a few scientific facts or compelling evidence derived from a handful of literature sources. 19 By contrast, reviews require analyses of a large number of published documents retrieved from several well-organized and evidence-based databases in accordance with predefined search strategies. 20 , 21 , 22

The format of hypotheses, especially the implications part, may vary widely across disciplines. Clinicians may limit their suggestions to the clinical manifestations of diseases, outcomes, and management strategies. Basic and laboratory scientists analysing genetic, molecular, and biochemical mechanisms may need to view beyond the frames of their narrow fields and predict social and population-based implications of the proposed ideas. 23

Advanced writing skills are essential for presenting an interesting theoretical article which appeals to the global readership. Merely listing opposing facts and ideas, without proper interpretation and analysis, may distract the experienced readers. The essence of a great hypothesis is a story behind the scientific facts and evidence-based data.

ETHICAL IMPLICATIONS

The authors of hypotheses substantiate their arguments by referring to and discerning rational points from published articles that might be overlooked by others. Their arguments may contradict the established theories and practices, and pose global ethical issues, particularly when more or less efficient medical technologies and public health interventions are devalued. The ethical issues may arise primarily because of the careless references to articles with low priorities, inadequate and apparently unethical methodologies, and concealed reporting of negative results. 24 , 25

Misinterpretation and misunderstanding of the published ideas and scientific hypotheses may complicate the issue further. For example, Alexander Fleming, whose innovative ideas of penicillin use to kill susceptible bacteria saved millions of lives, warned of the consequences of uncontrolled prescription of the drug. The issue of antibiotic resistance had emerged within the first ten years of penicillin use on a global scale due to the overprescription that affected the efficacy of antibiotic therapies, with undesirable consequences for millions. 26

The misunderstanding of the hygiene hypothesis that primarily aimed to shed light on the role of the microbiome in allergic and autoimmune diseases resulted in decline of public confidence in hygiene with dire societal implications, forcing some experts to abandon the original idea. 27 , 28 Although that hypothesis is unrelated to the issue of vaccinations, the public misunderstanding has resulted in decline of vaccinations at a time of upsurge of old and new infections.

A number of ethical issues are posed by the denial of the viral (human immunodeficiency viruses; HIV) hypothesis of acquired Immune deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) by Peter Duesberg, who overviewed the links between illicit recreational drugs and antiretroviral therapies with AIDS and refuted the etiological role of HIV. 29 That controversial hypothesis was rejected by several journals, but was eventually published without external peer review at Med Hypotheses in 2010. The publication itself raised concerns of the unconventional editorial policy of the journal, causing major perturbations and more scrutinized publishing policies by journals processing hypotheses.

WHERE TO PUBLISH HYPOTHESES

Although scientific authors are currently well informed and equipped with search tools to draft evidence-based hypotheses, there are still limited quality publication outlets calling for related articles. The journal editors may be hesitant to publish articles that do not adhere to any research reporting guidelines and open gates for harsh criticism of unconventional and untested ideas. Occasionally, the editors opting for open-access publishing and upgrading their ethics regulations launch a section to selectively publish scientific hypotheses attractive to the experienced readers. 30 However, the absence of approved standards for this article type, particularly no mandate for outlining potential ethical implications, may lead to publication of potentially harmful ideas in an attractive format.

A suggestion of simultaneously publishing multiple or alternative hypotheses to balance the reader views and feedback is a potential solution for the mainstream scholarly journals. 31 However, that option alone is hardly applicable to emerging journals with unconventional quality checks and peer review, accumulating papers with multiple rejections by established journals.

A large group of experts view hypotheses with improbable and controversial ideas publishable after formal editorial (in-house) checks to preserve the authors' genuine ideas and avoid conservative amendments imposed by external peer reviewers. 32 That approach may be acceptable for established publishers with large teams of experienced editors. However, the same approach can lead to dire consequences if employed by nonselective start-up, open-access journals processing all types of articles and primarily accepting those with charged publication fees. 33 In fact, pseudoscientific ideas arguing Newton's and Einstein's seminal works or those denying climate change that are hardly testable have already found their niche in substandard electronic journals with soft or nonexistent peer review. 34

CITATIONS AND SOCIAL MEDIA ATTENTION

The available preliminary evidence points to the attractiveness of hypothesis articles for readers, particularly those from research-intensive countries who actively download related documents. 35 However, citations of such articles are disproportionately low. Only a small proportion of top-downloaded hypotheses (13%) in the highly prestigious Med Hypotheses receive on average 5 citations per article within a two-year window. 36

With the exception of a few historic papers, the vast majority of hypotheses attract relatively small number of citations in a long term. 36 Plausible explanations are that these articles often contain a single or only a few citable points and that suggested research studies to test hypotheses are rarely conducted and reported, limiting chances of citing and crediting authors of genuine research ideas.

A snapshot analysis of citation activity of hypothesis articles may reveal interest of the global scientific community towards their implications across various disciplines and countries. As a prime example, Strachan's hygiene hypothesis, published in 1989, 10 is still attracting numerous citations on Scopus, the largest bibliographic database. As of August 28, 2019, the number of the linked citations in the database is 3,201. Of the citing articles, 160 are cited at least 160 times ( h -index of this research topic = 160). The first three citations are recorded in 1992 and followed by a rapid annual increase in citation activity and a peak of 212 in 2015 ( Fig. 1 ). The top 5 sources of the citations are Clin Exp Allergy (n = 136), J Allergy Clin Immunol (n = 119), Allergy (n = 81), Pediatr Allergy Immunol (n = 69), and PLOS One (n = 44). The top 5 citing authors are leading experts in pediatrics and allergology Erika von Mutius (Munich, Germany, number of publications with the index citation = 30), Erika Isolauri (Turku, Finland, n = 27), Patrick G Holt (Subiaco, Australia, n = 25), David P. Strachan (London, UK, n = 23), and Bengt Björksten (Stockholm, Sweden, n = 22). The U.S. is the leading country in terms of citation activity with 809 related documents, followed by the UK (n = 494), Germany (n = 314), Australia (n = 211), and the Netherlands (n = 177). The largest proportion of citing documents are articles (n = 1,726, 54%), followed by reviews (n = 950, 29.7%), and book chapters (n = 213, 6.7%). The main subject areas of the citing items are medicine (n = 2,581, 51.7%), immunology and microbiology (n = 1,179, 23.6%), and biochemistry, genetics and molecular biology (n = 415, 8.3%).

Interestingly, a recent analysis of 111 publications related to Strachan's hygiene hypothesis, stating that the lack of exposure to infections in early life increases the risk of rhinitis, revealed a selection bias of 5,551 citations on Web of Science. 37 The articles supportive of the hypothesis were cited more than nonsupportive ones (odds ratio adjusted for study design, 2.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.6–3.1). A similar conclusion pointing to a citation bias distorting bibliometrics of hypotheses was reached by an earlier analysis of a citation network linked to the idea that β-amyloid, which is involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease, is produced by skeletal muscle of patients with inclusion body myositis. 38 The results of both studies are in line with the notion that ‘positive’ citations are more frequent in the field of biomedicine than ‘negative’ ones, and that citations to articles with proven hypotheses are too common. 39

Social media channels are playing an increasingly active role in the generation and evaluation of scientific hypotheses. In fact, publicly discussing research questions on platforms of news outlets, such as Reddit, may shape hypotheses on health-related issues of global importance, such as obesity. 40 Analyzing Twitter comments, researchers may reveal both potentially valuable ideas and unfounded claims that surround groundbreaking research ideas. 41 Social media activities, however, are unevenly distributed across different research topics, journals and countries, and these are not always objective professional reflections of the breakthroughs in science. 2 , 42

Scientific hypotheses are essential for progress in science and advances in healthcare. Innovative ideas should be based on a critical overview of related scientific facts and evidence-based data, often overlooked by others. To generate realistic hypothetical theories, the authors should comprehensively analyze the literature and suggest relevant and ethically sound design for future studies. They should also consider their hypotheses in the context of research and publication ethics norms acceptable for their target journals. The journal editors aiming to diversify their portfolio by maintaining and introducing hypotheses section are in a position to upgrade guidelines for related articles by pointing to general and specific analyses of the subject, preferred study designs to test hypotheses, and ethical implications. The latter is closely related to specifics of hypotheses. For example, editorial recommendations to outline benefits and risks of a new laboratory test or therapy may result in a more balanced article and minimize associated risks afterwards.

Not all scientific hypotheses have immediate positive effects. Some, if not most, are never tested in properly designed research studies and never cited in credible and indexed publication outlets. Hypotheses in specialized scientific fields, particularly those hardly understandable for nonexperts, lose their attractiveness for increasingly interdisciplinary audience. The authors' honest analysis of the benefits and limitations of their hypotheses and concerted efforts of all stakeholders in science communication to initiate public discussion on widely visible platforms and social media may reveal rational points and caveats of the new ideas.

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions:

- Conceptualization: Gasparyan AY, Yessirkepov M, Kitas GD.

- Methodology: Gasparyan AY, Mukanova U, Ayvazyan L.

- Writing - original draft: Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Yessirkepov M.

- Writing - review & editing: Gasparyan AY, Yessirkepov M, Mukanova U, Kitas GD.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

High school biology

Course: high school biology > unit 1.

- Biology overview

- Preparing to study biology

- What is life?

- The scientific method

- Data to justify experimental claims examples

- Scientific method and data analysis

- Introduction to experimental design

- Controlled experiments

Biology and the scientific method review

- Experimental design and bias

The nature of biology

Properties of life.

- Organization: Living things are highly organized (meaning they contain specialized, coordinated parts) and are made up of one or more cells .

- Metabolism: Living things must use energy and consume nutrients to carry out the chemical reactions that sustain life. The sum total of the biochemical reactions occurring in an organism is called its metabolism .

- Homeostasis : Living organisms regulate their internal environment to maintain the relatively narrow range of conditions needed for cell function.

- Growth : Living organisms undergo regulated growth. Individual cells become larger in size, and multicellular organisms accumulate many cells through cell division.

- Reproduction : Living organisms can reproduce themselves to create new organisms.

- Response : Living organisms respond to stimuli or changes in their environment.

- Evolution : Populations of living organisms can undergo evolution , meaning that the genetic makeup of a population may change over time.

Scientific methodology

Scientific method example: failure to toast.

- Observation: the toaster won't toast.

- Question: Why won't my toaster toast?

- Hypothesis: Maybe the outlet is broken.

- Prediction: If I plug the toaster into a different outlet, then it will toast the bread.

- Test of prediction: Plug the toaster into a different outlet and try again.

- Iteration time!

Experimental design

Reducing errors and bias.

- Having a large sample size in the experiment: This helps to account for any small differences among the test subjects that may provide unexpected results.

- Repeating experimental trials multiple times: Errors may result from slight differences in test subjects, or mistakes in methodology or data collection. Repeating trials helps reduce those effects.

- Including all data points: Sometimes it is tempting to throw away data points that are inconsistent with the proposed hypothesis. However, this makes for an inaccurate study! All data points need to be included, whether they support the hypothesis or not.

- Using placebos , when appropriate: Placebos prevent the test subjects from knowing whether they received a real therapeutic substance. This helps researchers determine whether a substance has a true effect.

- Implementing double-blind studies , when appropriate: Double-blind studies prevent researchers from knowing the status of a particular participant. This helps eliminate observer bias.

Communicating findings

Things to remember.

- A hypothesis is not necessarily the right explanation. Instead, it is a possible explanation that can be tested to see if it is likely correct, or if a new hypothesis needs to be made.

- Not all explanations can be considered a hypothesis. A hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable in order to be valid. For example, “The universe is beautiful" is not a good hypothesis, because there is no experiment that could test this statement and show it to be false.

- In most cases, the scientific method is an iterative process. In other words, it's a cycle rather than a straight line. The result of one experiment often becomes feedback that raises questions for more experimentation.

- Scientists use the word "theory" in a very different way than non-scientists. When many people say "I have a theory," they really mean "I have a guess." Scientific theories, on the other hand, are well-tested and highly reliable scientific explanations of natural phenomena. They unify many repeated observations and data collected from lots of experiments.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Hypothesis n., plural: hypotheses [/haɪˈpɑːθəsɪs/] Definition: Testable scientific prediction

What Is Hypothesis?

A scientific hypothesis is a foundational element of the scientific method . It’s a testable statement proposing a potential explanation for natural phenomena. The term hypothesis means “little theory” . A hypothesis is a short statement that can be tested and gives a possible reason for a phenomenon or a possible link between two variables . In the setting of scientific research, a hypothesis is a tentative explanation or statement that can be proven wrong and is used to guide experiments and empirical research.

It is an important part of the scientific method because it gives a basis for planning tests, gathering data, and judging evidence to see if it is true and could help us understand how natural things work. Several hypotheses can be tested in the real world, and the results of careful and systematic observation and analysis can be used to support, reject, or improve them.

Researchers and scientists often use the word hypothesis to refer to this educated guess . These hypotheses are firmly established based on scientific principles and the rigorous testing of new technology and experiments .

For example, in astrophysics, the Big Bang Theory is a working hypothesis that explains the origins of the universe and considers it as a natural phenomenon. It is among the most prominent scientific hypotheses in the field.

“The scientific method: steps, terms, and examples” by Scishow:

Biology definition: A hypothesis is a supposition or tentative explanation for (a group of) phenomena, (a set of) facts, or a scientific inquiry that may be tested, verified or answered by further investigation or methodological experiment. It is like a scientific guess . It’s an idea or prediction that scientists make before they do experiments. They use it to guess what might happen and then test it to see if they were right. It’s like a smart guess that helps them learn new things. A scientific hypothesis that has been verified through scientific experiment and research may well be considered a scientific theory .

Etymology: The word “hypothesis” comes from the Greek word “hupothesis,” which means “a basis” or “a supposition.” It combines “hupo” (under) and “thesis” (placing). Synonym: proposition; assumption; conjecture; postulate Compare: theory See also: null hypothesis

Characteristics Of Hypothesis

A useful hypothesis must have the following qualities:

- It should never be written as a question.

- You should be able to test it in the real world to see if it’s right or wrong.

- It needs to be clear and exact.

- It should list the factors that will be used to figure out the relationship.

- It should only talk about one thing. You can make a theory in either a descriptive or form of relationship.

- It shouldn’t go against any natural rule that everyone knows is true. Verification will be done well with the tools and methods that are available.

- It should be written in as simple a way as possible so that everyone can understand it.

- It must explain what happened to make an answer necessary.

- It should be testable in a fair amount of time.

- It shouldn’t say different things.

Sources Of Hypothesis

Sources of hypothesis are:

- Patterns of similarity between the phenomenon under investigation and existing hypotheses.

- Insights derived from prior research, concurrent observations, and insights from opposing perspectives.

- The formulations are derived from accepted scientific theories and proposed by researchers.

- In research, it’s essential to consider hypothesis as different subject areas may require various hypotheses (plural form of hypothesis). Researchers also establish a significance level to determine the strength of evidence supporting a hypothesis.

- Individual cognitive processes also contribute to the formation of hypotheses.

One hypothesis is a tentative explanation for an observation or phenomenon. It is based on prior knowledge and understanding of the world, and it can be tested by gathering and analyzing data. Observed facts are the data that are collected to test a hypothesis. They can support or refute the hypothesis.

For example, the hypothesis that “eating more fruits and vegetables will improve your health” can be tested by gathering data on the health of people who eat different amounts of fruits and vegetables. If the people who eat more fruits and vegetables are healthier than those who eat less fruits and vegetables, then the hypothesis is supported.

Hypotheses are essential for scientific inquiry. They help scientists to focus their research, to design experiments, and to interpret their results. They are also essential for the development of scientific theories.

Types Of Hypothesis

In research, you typically encounter two types of hypothesis: the alternative hypothesis (which proposes a relationship between variables) and the null hypothesis (which suggests no relationship).

It illustrates the association between one dependent variable and one independent variable. For instance, if you consume more vegetables, you will lose weight more quickly. Here, increasing vegetable consumption is the independent variable, while weight loss is the dependent variable.

It exhibits the relationship between at least two dependent variables and at least two independent variables. Eating more vegetables and fruits results in weight loss, radiant skin, and a decreased risk of numerous diseases, including heart disease.

It shows that a researcher wants to reach a certain goal. The way the factors are related can also tell us about their nature. For example, four-year-old children who eat well over a time of five years have a higher IQ than children who don’t eat well. This shows what happened and how it happened.

When there is no theory involved, it is used. It is a statement that there is a connection between two variables, but it doesn’t say what that relationship is or which way it goes.

It says something that goes against the theory. It’s a statement that says something is not true, and there is no link between the independent and dependent factors. “H 0 ” represents the null hypothesis.

Associative and Causal Hypothesis

When a change in one variable causes a change in the other variable, this is called the associative hypothesis . The causal hypothesis, on the other hand, says that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between two or more factors.

Examples Of Hypothesis

Examples of simple hypotheses:

- Students who consume breakfast before taking a math test will have a better overall performance than students who do not consume breakfast.

- Students who experience test anxiety before an English examination will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety.

- Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone, is a statement that suggests that drivers who talk on the phone while driving are more likely to make mistakes.

Examples of a complex hypothesis:

- Individuals who consume a lot of sugar and don’t get much exercise are at an increased risk of developing depression.

- Younger people who are routinely exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces, according to a new study.

- Increased levels of air pollution led to higher rates of respiratory illnesses, which in turn resulted in increased costs for healthcare for the affected communities.

Examples of Directional Hypothesis:

- The crop yield will go up a lot if the amount of fertilizer is increased.

- Patients who have surgery and are exposed to more stress will need more time to get better.

- Increasing the frequency of brand advertising on social media will lead to a significant increase in brand awareness among the target audience.

Examples of Non-Directional Hypothesis (or Two-Tailed Hypothesis):

- The test scores of two groups of students are very different from each other.

- There is a link between gender and being happy at work.

- There is a correlation between the amount of caffeine an individual consumes and the speed with which they react.

Examples of a null hypothesis:

- Children who receive a new reading intervention will have scores that are different than students who do not receive the intervention.

- The results of a memory recall test will not reveal any significant gap in performance between children and adults.

- There is not a significant relationship between the number of hours spent playing video games and academic performance.

Examples of Associative Hypothesis:

- There is a link between how many hours you spend studying and how well you do in school.

- Drinking sugary drinks is bad for your health as a whole.

- There is an association between socioeconomic status and access to quality healthcare services in urban neighborhoods.

Functions Of Hypothesis

The research issue can be understood better with the help of a hypothesis, which is why developing one is crucial. The following are some of the specific roles that a hypothesis plays: (Rashid, Apr 20, 2022)

- A hypothesis gives a study a point of concentration. It enlightens us as to the specific characteristics of a study subject we need to look into.

- It instructs us on what data to acquire as well as what data we should not collect, giving the study a focal point .

- The development of a hypothesis improves objectivity since it enables the establishment of a focal point.

- A hypothesis makes it possible for us to contribute to the development of the theory. Because of this, we are in a position to definitively determine what is true and what is untrue .

How will Hypothesis help in the Scientific Method?

- The scientific method begins with observation and inquiry about the natural world when formulating research questions. Researchers can refine their observations and queries into specific, testable research questions with the aid of hypothesis. They provide an investigation with a focused starting point.

- Hypothesis generate specific predictions regarding the expected outcomes of experiments or observations. These forecasts are founded on the researcher’s current knowledge of the subject. They elucidate what researchers anticipate observing if the hypothesis is true.

- Hypothesis direct the design of experiments and data collection techniques. Researchers can use them to determine which variables to measure or manipulate, which data to obtain, and how to conduct systematic and controlled research.

- Following the formulation of a hypothesis and the design of an experiment, researchers collect data through observation, measurement, or experimentation. The collected data is used to verify the hypothesis’s predictions.

- Hypothesis establish the criteria for evaluating experiment results. The observed data are compared to the predictions generated by the hypothesis. This analysis helps determine whether empirical evidence supports or refutes the hypothesis.

- The results of experiments or observations are used to derive conclusions regarding the hypothesis. If the data support the predictions, then the hypothesis is supported. If this is not the case, the hypothesis may be revised or rejected, leading to the formulation of new queries and hypothesis.

- The scientific approach is iterative, resulting in new hypothesis and research issues from previous trials. This cycle of hypothesis generation, testing, and refining drives scientific progress.

Importance Of Hypothesis

- Hypothesis are testable statements that enable scientists to determine if their predictions are accurate. This assessment is essential to the scientific method, which is based on empirical evidence.

- Hypothesis serve as the foundation for designing experiments or data collection techniques. They can be used by researchers to develop protocols and procedures that will produce meaningful results.

- Hypothesis hold scientists accountable for their assertions. They establish expectations for what the research should reveal and enable others to assess the validity of the findings.

- Hypothesis aid in identifying the most important variables of a study. The variables can then be measured, manipulated, or analyzed to determine their relationships.

- Hypothesis assist researchers in allocating their resources efficiently. They ensure that time, money, and effort are spent investigating specific concerns, as opposed to exploring random concepts.

- Testing hypothesis contribute to the scientific body of knowledge. Whether or not a hypothesis is supported, the results contribute to our understanding of a phenomenon.

- Hypothesis can result in the creation of theories. When supported by substantive evidence, hypothesis can serve as the foundation for larger theoretical frameworks that explain complex phenomena.

- Beyond scientific research, hypothesis play a role in the solution of problems in a variety of domains. They enable professionals to make educated assumptions about the causes of problems and to devise solutions.

Research Hypotheses: Did you know that a hypothesis refers to an educated guess or prediction about the outcome of a research study?

It’s like a roadmap guiding researchers towards their destination of knowledge. Just like a compass points north, a well-crafted hypothesis points the way to valuable discoveries in the world of science and inquiry.

Choose the best answer.

Send Your Results (Optional)

Further Reading

- RNA-DNA World Hypothesis

- BYJU’S. (2023). Hypothesis. Retrieved 01 Septermber 2023, from https://byjus.com/physics/hypothesis/#sources-of-hypothesis

- Collegedunia. (2023). Hypothesis. Retrieved 1 September 2023, from https://collegedunia.com/exams/hypothesis-science-articleid-7026#d

- Hussain, D. J. (2022). Hypothesis. Retrieved 01 September 2023, from https://mmhapu.ac.in/doc/eContent/Management/JamesHusain/Research%20Hypothesis%20-Meaning,%20Nature%20&%20Importance-Characteristics%20of%20Good%20%20Hypothesis%20Sem2.pdf

- Media, D. (2023). Hypothesis in the Scientific Method. Retrieved 01 September 2023, from https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-hypothesis-2795239#toc-hypotheses-examples

- Rashid, M. H. A. (Apr 20, 2022). Research Methodology. Retrieved 01 September 2023, from https://limbd.org/hypothesis-definitions-functions-characteristics-types-errors-the-process-of-testing-a-hypothesis-hypotheses-in-qualitative-research/#:~:text=Functions%20of%20a%20Hypothesis%3A&text=Specifically%2C%20a%20hypothesis%20serves%20the,providing%20focus%20to%20the%20study.

©BiologyOnline.com. Content provided and moderated by Biology Online Editors.

Last updated on September 8th, 2023

You will also like...

Gene Action – Operon Hypothesis

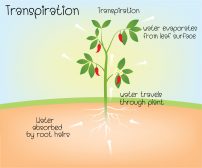

Water in Plants

Growth and Plant Hormones

Sigmund Freud and Carl Gustav Jung

Population Growth and Survivorship

Related articles....

RNA-DNA World Hypothesis?

On Mate Selection Evolution: Are intelligent males more attractive?

Actions of Caffeine in the Brain with Special Reference to Factors That Contribute to Its Widespread Use

Dead Man Walking

1.3: The Scientific Method

Chapter 1: scientific inquiry, chapter 2: chemistry of life, chapter 3: macromolecules, chapter 4: cell structure and function, chapter 5: membranes and cellular transport, chapter 6: cell signaling, chapter 7: metabolism, chapter 8: cellular respiration, chapter 9: photosynthesis, chapter 10: cell cycle and division, chapter 11: meiosis, chapter 12: classical and modern genetics, chapter 13: dna structure and function, chapter 14: gene expression, chapter 15: biotechnology, chapter 16: viruses, chapter 17: nutrition and digestion, chapter 18: nervous system, chapter 19: sensory systems, chapter 20: musculoskeletal system, chapter 21: endocrine system, chapter 22: circulatory and pulmonary systems, chapter 23: osmoregulation and excretion, chapter 24: immune system, chapter 25: reproduction and development, chapter 26: behavior, chapter 27: ecosystems, chapter 28: population and community ecology, chapter 29: biodiversity and conservation, chapter 30: speciation and diversity, chapter 31: natural selection, chapter 32: population genetics, chapter 33: evolutionary history, chapter 34: plant structure, growth, and nutrition, chapter 35: plant reproduction, chapter 36: plant responses to the environment.

The JoVE video player is compatible with HTML5 and Adobe Flash. Older browsers that do not support HTML5 and the H.264 video codec will still use a Flash-based video player. We recommend downloading the newest version of Flash here, but we support all versions 10 and above.

The scientific method is a detailed, stepwise process for answering questions. For example, a scientist makes an observation that the slugs destroy some cabbages but not those near garlic.

Such observations lead to asking questions, "Could garlic be used to deter slugs from ruining a cabbage patch?" After formulating questions, the scientist can then develop hypotheses —potential explanations for the observations that lead to specific, testable predictions.

In this case, a hypothesis could be that garlic repels slugs, which predicts that cabbages surrounded by garlic powder will suffer less damage than the ones without it.

The hypothesis is then tested through a series of experiments designed to eliminate hypotheses.

The experimental setup involves defining variables. An independent variable is an item that is being tested, in this case, garlic addition. The dependent variable describes the measurement used to determine the outcome, such as the number of slugs on the cabbages.

In addition, the slugs must be divided into groups, experimental and control. These groups are identical, except that the experimental group is exposed to garlic powder.

After data are collected and analyzed, conclusions are made, and results are communicated to other scientists.

The scientific method is a detailed, empirical problem-solving process used by biologists and other scientists. This iterative approach involves formulating a question based on observation, developing a testable potential explanation for the observation (called a hypothesis), making and testing predictions based on the hypothesis, and using the findings to create new hypotheses and predictions.

Generally, predictions are tested using carefully-designed experiments. Based on the outcome of these experiments, the original hypothesis may need to be refined, and new hypotheses and questions can be generated. Importantly, this illustrates that the scientific method is not a stepwise recipe. Instead, it is a continuous refinement and testing of ideas based on new observations, which is the crux of scientific inquiry.

Science is mutable and continuously changes as scientists learn more about the world, physical phenomena and how organisms interact with their environment. For this reason, scientists avoid claiming to ‘prove' a specific idea. Instead, they gather evidence that either supports or refutes a given hypothesis.

Making Observations and Formulating Hypotheses

A hypothesis is preceded by an initial observation, during which information is gathered by the senses (e.g., vision, hearing) or using scientific tools and instruments. This observation leads to a question that prompts the formation of an initial hypothesis, a (testable) possible answer to the question. For example, the observation that slugs eat some cabbage plants but not cabbage plants located near garlic may prompt the question: why do slugs selectively not eat cabbage plants near garlic? One possible hypothesis, or answer to this question, is that slugs have an aversion to garlic. Based on this hypothesis, one might predict that slugs will not eat cabbage plants surrounded by a ring of garlic powder.

A hypothesis should be falsifiable, meaning that there are ways to disprove it if it is untrue. In other words, a hypothesis should be testable. Scientists often articulate and explicitly test for the opposite of the hypothesis, which is called the null hypothesis. In this case, the null hypothesis is that slugs do not have an aversion to garlic. The null hypothesis would be supported if, contrary to the prediction, slugs eat cabbage plants that are surrounded by garlic powder.

Testing a Hypothesis

When possible, scientists test hypotheses using controlled experiments that include independent and dependent variables, as well as control and experimental groups.

An independent variable is an item expected to have an effect (e.g., the garlic powder used in the slug and cabbage experiment or treatment given in a clinical trial). Dependent variables are the measurements used to determine the outcome of an experiment. In the experiment with slugs, cabbages, and garlic, the number of slugs eating cabbages is the dependent variable. This number is expected to depend on the presence or absence of garlic powder rings around the cabbage plants.

Experiments require experimental and control groups. An experimental group is treated with or exposed to the independent variable (i.e., the manipulation or treatment). For example, in the garlic aversion experiment with slugs, the experimental group is a group of cabbage plants surrounded by a garlic powder ring. A control group is subject to the same conditions as the experimental group, with the exception of the independent variable. Control groups in this experiment might include a group of cabbage plants in the same area that is surrounded by a non-garlic powder ring (to control for powder aversion) and a group that is not surrounded by any particular substance (to control for cabbage aversion). It is essential to include a control group because, without one, it is unclear whether the outcome is the result of the treatment or manipulation.

Refining a Hypothesis

If the results of an experiment support the hypothesis, further experiments may be designed and carried out to provide support for the hypothesis. The hypothesis may also be refined and made more specific. For example, additional experiments could determine whether slugs also have an aversion to other plants of the Allium genus, like onions.

If the results do not support the hypothesis, then the original hypothesis may be modified based on the new observations. It is important to rule out potential problems with the experimental design before modifying the hypothesis. For example, if slugs demonstrate an aversion to both garlic and non-garlic powder, the experiment can be carried out again using fresh garlic instead of powdered garlic. If the slugs still exhibit no aversion to garlic, then the original hypothesis can be modified.

Communication

The results of the experiments should be communicated to other scientists and the public, regardless of whether the data support the original hypothesis. This information can guide the development of new hypotheses and experimental questions.

Get cutting-edge science videos from J o VE sent straight to your inbox every month.

mktb-description

We use cookies to enhance your experience on our website.

By continuing to use our website or clicking “Continue”, you are agreeing to accept our cookies.

Research Hypothesis In Psychology: Types, & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A research hypothesis, in its plural form “hypotheses,” is a specific, testable prediction about the anticipated results of a study, established at its outset. It is a key component of the scientific method .

Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding

Some key points about hypotheses:

- A hypothesis expresses an expected pattern or relationship. It connects the variables under investigation.

- It is stated in clear, precise terms before any data collection or analysis occurs. This makes the hypothesis testable.

- A hypothesis must be falsifiable. It should be possible, even if unlikely in practice, to collect data that disconfirms rather than supports the hypothesis.

- Hypotheses guide research. Scientists design studies to explicitly evaluate hypotheses about how nature works.

- For a hypothesis to be valid, it must be testable against empirical evidence. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

- Hypotheses are informed by background knowledge and observation, but go beyond what is already known to propose an explanation of how or why something occurs.

Predictions typically arise from a thorough knowledge of the research literature, curiosity about real-world problems or implications, and integrating this to advance theory. They build on existing literature while providing new insight.

Types of Research Hypotheses

Alternative hypothesis.

The research hypothesis is often called the alternative or experimental hypothesis in experimental research.

It typically suggests a potential relationship between two key variables: the independent variable, which the researcher manipulates, and the dependent variable, which is measured based on those changes.

The alternative hypothesis states a relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable affects the other).

A hypothesis is a testable statement or prediction about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a key component of the scientific method. Some key points about hypotheses:

- Important hypotheses lead to predictions that can be tested empirically. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

In summary, a hypothesis is a precise, testable statement of what researchers expect to happen in a study and why. Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding.