- Key Differences

Know the Differences & Comparisons

Difference Between Oral Communication and Written Communication

Written Communication , on the other hand, is a formal means of communication, wherein message is carefully drafted and formulated in written form. It is kept as a source of reference or legal record. In this article, we’ve presented all the important differences between oral and written communication in tabular form.

Content: Oral Communication Vs Written Communication

Comparison chart.

| Basis for Communication | Oral Communication | Written Communication |

|---|---|---|

| Meaning | Exchange of ideas, information and message through spoken words is Oral Communication. | Interchange of message, opinions and information in written or printed form is Written Communication. |

| What is it? | Communication with the help of words of mouth. | Communication with the help of text. |

| Literacy | Not required at all. | Necessary for communication. |

| Transmission of message | Speedy | Slow |

| Proof | No record of communication is there. | Proper records of communication are present. |

| Feedback | Immediate feedback can be given | Feedback takes time. |

| Revision before delivering the message? | Not possible | Possible |

| Receipt of nonverbal cues | Yes | No |

| Probability of misunderstanding | Very high | Quite less |

Definition of Oral Communication

Oral Communication is the process of conveying or receiving messages with the use of spoken words. This mode of communication is highly used across the world because of rapid transmission of information and prompt reply.

Oral communication can either be in the form of direct conversation between two or more persons like face to face communication, lectures, meetings, seminars, group discussion, conferences, etc. or indirect conversation, i.e. the form of communication in which a medium is used for interchange of information like telephonic conversation, video call, voice call, etc.

The best thing about this mode of communication is that the parties to communication, i.e. sender or receiver, can notice nonverbal cues like the body language, facial expression, tone of voice and pitch, etc. This makes the communication between the parties more effective. However, this mode is backed with some limitation like the words once spoken can never be taken back.

Video: Oral Communication

Definition of Written Communication

The communication in which the message is transmitted in written or printed form is known as Written Communication. It is the most reliable mode of communication, and it is highly preferred in the business world because of its formal and sophisticated nature. The various channels of written communication are letters, e-mails, journals, magazines, newspapers, text messages, reports, etc. There are a number of advantages of written communication which are as under:

- Referring the message in the future will be easy.

- Before transmitting the message, one can revise or rewrite it in an organised way.

- The chances of misinterpretation of message are very less because the words are carefully chosen.

- The communication is planned.

- Legal evidence is available due to the safekeeping of records.

But as we all know that everything has two aspects, same is the case with written communication as the communication is a time consuming one. Moreover, the sender will never know that the receiver has read the message or not. The sender has to wait for the responses of the receiver. A lot of paperwork is there, in this mode of communication.

Video: Written Communication

Key Differences Between Oral Communication and Written Communication

The following are the major differences between oral communication and written communication:

- The type of communication in which the sender transmits information to the receiver through verbally speaking the message. The communication mode, which uses written or printed text for exchanging the information is known as Written Communication.

- The pre-condition in written communication is that the participants must be literate whereas there is no such condition in case of oral communication.

- Proper records are there in Written Communication, which is just opposite in the case of Oral Communication.

- Oral Communication is faster than Written Communication.

- The words once uttered cannot be reversed in the case of Oral Communication. On the other hand, editing of the original message is possible in Written Communication.

- Misinterpretation of the message is possible in Oral Communication but not in Written Communication.

- In oral communication, instant feedback is received from the recipient which is not possible in Written Communication.

Video: Oral Vs Written Communication

Oral Communication is an informal one which is normally used in personal conversations, group talks, etc. Written Communication is formal communication, which is used in schools, colleges, business world, etc. Choosing between the two communication mode is a tough task because both are good at their places. People normally use the oral mode of communication because it is convenient and less time-consuming. However, people normally believe in the written text more than what they hear that is why written communication is considered as the reliable method of communication.

You Might Also Like:

michael nabutia says

October 12, 2016 at 11:18 am

I am blessed with your rich resource of information

January 7, 2017 at 10:40 am

Thank you so much for such a important article … You present this so simply and it’s helpful

Qods Qodsi says

January 22, 2019 at 1:25 pm

In the name of Allah After hours of searching and getting totally confused!,

Thank you so much for such a important article … You present this so simply and it’s helpful

I Appreciate it a lot

Wilson says

November 19, 2019 at 8:21 am

Nice I get all the points of difference…thankss Google

November 11, 2020 at 8:24 pm

It’s awesome❤

Austin says

November 18, 2020 at 11:25 am

thanks alot the platform is so amazing

Thobiad says

December 28, 2020 at 11:12 pm

so good,, thanks for it

Lam koak Reath jok says

January 26, 2021 at 6:45 pm

I’m very convenient with the message of differences between the two types of communication ie oral and written communication thank Alot for the lifts

M talha says

March 19, 2021 at 9:07 pm

Little bit satisfied …but ..it is really help full

TEUIA KOROTABU says

March 30, 2021 at 8:50 pm

This is very informative thanks for sharing

September 13, 2021 at 6:54 pm

Thank you soon much for your quality resources .

Jayaraman says

July 26, 2022 at 1:05 pm

I would say that great effort by the author.

Ozah Gregory says

November 11, 2022 at 10:06 pm

Thanks for doing justice to this topic

Stephen Mwale says

May 12, 2023 at 1:36 pm

Thank you very much i really appreciate a lot 👏👏👏🙏🙏

Julie L Humphreys says

October 1, 2023 at 2:03 pm

thank You This was helpful to us both

Esther says

January 10, 2024 at 4:58 am

Thank you .Very helpful and easily understood!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Module 7: Refining your Speech

Oral versus written style, learning objectives.

Explain the difference between oral and written style.

In a public speaking class, you will likely be asked to turn in an outline rather than a manuscript because speeches should not be considered oral presentations of a written text.

It takes a lot of practice to make reading from a teleprompter (or a manuscript) sound natural. It takes even more practice to write in a style that sounds like speech.

Although we’ve seen many speeches delivered from a teleprompter, it is important to remember that those speeches are usually written by professional speechwriters, who are familiar with the differences between written and spoken communication. For newer speakers who are writing their own speeches, identifying the differences between oral and written style is an important key to a successful speech.

Oral communication is characterized by a higher level of immediacy and a lower level of retention than written communication; therefore, it’s important to consider the following adaptations between oral and written style.

Personal Pronouns

- Example: In her acceptance speech for the 2015 Goldman Environmental Prize, activist Berta Cáceres says “¡Despertemos¡ ¡Despertemos Humanidad¡ Ya no hay tiempo. . . . El Río Gualcarque nos ha llamado, así como los demás que están seriamente amenazados. Debemos acudir.” (Let us wake up! Let us wake up, humanity! There is no time. . . . The Gualcarque River has called upon us, as have other gravely threatened rivers. We must answer their call.)

- Written Style: Infrequent use of personal pronouns, most commonly uses third person such as one , they , and he/she/they .

Grammar and Sentence Structure

- Example: Ashton Applewhite begins her TED talk “Let’s End Ageism” with a series of questions and short sentences, many starting with and : “What’s one thing that every person in this room is going to become? Older. And most of us are scared stiff at the prospect. How does that word make you feel? I used to feel the same way. What was I most worried about? Ending up drooling in some grim institutional hallway. And then I learned that only four percent of older Americans are living in nursing homes, and the percentage is dropping. What else was I worried about? Dementia. Turns out that most of us can think just fine to the end. Dementia rates are dropping, too. The real epidemic is anxiety over memory loss.” [1]

- Example: “In many modern nations, however, industrialization contributed to the diminished social standing of the elderly. Today wealth, power, and prestige are also held by those in younger age brackets. The average age of corporate executives was fifty-nine years old in 1980. In 2008, the average age had lowered to fifty-four years old (Stuart 2008). Some older members of the workforce felt threatened by this trend and grew concerned that younger employees in higher level positions would push them out of the job market. Rapid advancements in technology and media have required new skill sets that older members of the workforce are less likely to have.” [2]

Repetition is a great strategy in speaking . . .

- Example: Winston Churchill, speech to the House of Commons, June 4, 1940: “We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.” [3]

. . . but boring in writing.

- Where Churchill’s speech uses the verb fight seven times, this excerpt about the Battle of Britain from a biography of Churchill uses a variety of words and formulations to describing the fighting. “The Luftwaffe’s [German Air Force’s] first object was to destroy the RAF’s [the British Royal Air Force’s] southern airfields. Had this been accomplished there is no doubt that a seaborne invasion would have been launched with a good prospect of establishing a bridgehead in Kent or Sussex. After that the outlook for Britain’s survival would have been bleak. But the RAF successfully defended its airfields and inflicted very heavy casualties on the German formations, in a ratio of three to one. Moreover, the German aircrews were mostly killed or captured whereas British crews parachuted to safety. Throughout July and August the advantage moved steadily to Britain, and more aircraft and crews were added each week to lengthen the odds against Germany. By mid-September, the Battle of Britain was won.” [4]

Colloquialisms and Tone

- Example: Simon Sinek, “How Great Leaders Inspire Action,” said, “As we said before, the recipe for success is money and the right people and the right market conditions. You should have success then. Look at TiVo. From the time TiVo came out about eight or nine years ago to this current day, they are the single highest-quality product on the market, hands down, there is no dispute. They were extremely well-funded. Market conditions were fantastic. I mean, we use TiVo as verb. I TiVo stuff on my piece-of-junk Time Warner DVR all the time.” [5]

- From an academic article about TiVo: “Our analysis of the longitudinal data on TiVo and the TV industry ecosystem generated three themes that we develop in this paper. First, a disruptor confronts three coopetitive tensions—intertemporal, dyadic, and multilateral. Second, the disruptor continually adjusts its strategy to address these coopetitive tensions as they arise. Third, as the disruptor’s innovation and relational positioning within the changing ecosystem coevolve, the disruptor has greater latitude to frame its innovation as sustaining the operations of ecosystem members. Overall, these themes contribute to an understanding of strategy as process.” [6]

- Note how Sinek, in the example above, uses everyday words in simple sentences. The thesis of his speech is stated equally simply: “People don’t buy what you do; they buy why you do it.”

- The academic article cited above uses a number of words most non-expert readers would have to look up to understand. Coopetitive is a made-up word combining cooperative and competition. Intertemporal describes a relationship between past, present, and future events. Dyadic describes the interaction between two things. And multilateral means three or more parties are involved. In a speech—unless it’s a speech to experts—a sentence containing all four of these words will cruise over the heads of most audience members.

- https://www.ted.com/talks/ashton_applewhite_let_s_end_ageism ↵

- https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-introductiontosociology/chapter/ageism-and-abuse/ ↵

- https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/speeches/1940-the-finest-hour/we-shall-fight-on-the-beaches/ ↵

- Johnson, Paul. Churchill . United Kingdom, Penguin, 2010, 118. ↵

- https://www.ted.com/talks/simon_sinek_how_great_leaders_inspire_action ↵

- Ansari, Shahzad, Raghu Garud, and Arun Kumaraswamy. "The disruptor's dilemma: TiVo and the US television ecosystem." Strategic Management Journal 37.9 (2016): 1829–53, 1830. ↵

- Teleprompter. Authored by : Paolo Margari. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Teleprompter_in_use.jpg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Pillars. Authored by : StockSnap. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/pillars-shadows-architecture-924982/ . License : Other . License Terms : Pixabay License

- Oral vs. Written Style. Authored by : Anne Fleischer with Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

Oral vs Written Communication Skills | Importance & Examples

Kristen earned a Bachelor of Arts in Communication (cum laude) and certification in SEO and digital advertising. She has several years of academic writing with industry experience as a tutor, business writer, manager at a Fortune 100 company, and news producer. She's taught English, business, education, and art.

Kat has a Master of Science in Organizational Leadership and Management and teaches Business courses.

Why are oral and written communication skills important?

Both oral communication and written communication skills are important to ensure the quality of the information. Both should be accurate and efficiently conveyed, as well as ensuring clarity of the content.

What are some examples of oral and written communication?

Some examples of oral communication include activities that require communication to be vocal, such as persuading people in speeches and sharing ideas on the radio. Written communication includes forms of communication that must be written, such as an email or a handwritten letter.

Table of Contents

What are oral and written communication skills, what is the difference between oral communication and written communication, importance of verbal and written communication, lesson summary.

Communication is a broad field that covers many different means of spreading and transferring messages. There are many forms of communication that focus on a specific means or aspect of communication. Two common forms that are often compared are oral communication and written communication.

Oral communication refers to the communication that takes place by speaking. This includes basic conversations, as well as speeches and meetings. Written communication refers to the type of communication that uses the written word. This can be typed on an electronic device, such as an email on a computer, or handwritten, such as a note or a letter. Both oral communication and written communication are used on a daily basis. While both may convey the same messages, they may be used for different purposes.

Written Communication Skills Examples

There are many forms of written communication. Some of the most common forms include:

- Text messages

- Cards and letters

Written communication skills involve being able to read and write, as well as edit information for clarity. It is also important for the writer to understand how to use proper grammar and punctuation for credibility. Written communication may also make use of specific styles, such as Associated Press, or AP style, which is commonly used in newspapers and magazines.

Oral Communication Skills Examples

Oral communication skills can also be used for many different purposes. Some common examples of oral communication include:

- Sharing ideas

- Communicating thoughts

- Exchanging information

- Giving orders

- Persuading people

Oral communication skills rely on the ability to articulate works in an effective manner. Taking time to practice and receive feedback on general communication skills can help to improve oral communication skills. Things such as presentations and engaging in meetings or class discussions can also help to improve these skills.

Oral communication skills are common in the media where communication is typically distributed vocally. Radio, for example, relies heavily on the use of oral communication since speaking is the means of broadcasting via radio. Nonverbal skills may also come into play with oral communication where the speaker can be seen, such as in speeches or interviews. Nonverbal skills include tone, body language, and visual cues. These skills can be helpful in generating interest in the topic that is covered in a speech, as compared to simply reading transcripts of the speech.

To unlock this lesson you must be a Study.com Member. Create your account

An error occurred trying to load this video.

Try refreshing the page, or contact customer support.

You must c C reate an account to continue watching

Register to view this lesson.

As a member, you'll also get unlimited access to over 88,000 lessons in math, English, science, history, and more. Plus, get practice tests, quizzes, and personalized coaching to help you succeed.

Get unlimited access to over 88,000 lessons.

Already registered? Log in here for access

Resources created by teachers for teachers.

I would definitely recommend Study.com to my colleagues. It’s like a teacher waved a magic wand and did the work for me. I feel like it’s a lifeline.

You're on a roll. Keep up the good work!

Just checking in. are you still watching.

- 0:02 What Exactly Is Oral…

- 0:29 Written Communication

- 0:55 Differences: Oral and…

- 2:20 Lesson Summary

The main difference between oral communication and written communication is the way in which the message is distributed. Written communication is also generally more formal than oral communication. Still, there are other factors that differentiate the two types of communication . These include the preciseness of the message, audience engagement, and retention of the information.

The preciseness of the message differs in both written and oral communication. Communication that is written out and sent typically cannot be edited but speaking to an audience provides flexibility. Oral communication allows the speaker to make changes and go back to the main points if they don't respond as the speaker expected. The speaker can determine how the audience is reacting to the message being conveyed and make changes as they go along. On the other hand, written communication also allows the writer to make edits before sending out their message. While using oral communication occurs on the spot and cannot be edited, written communication allows the writer to first draft their idea and have an editor look over it before it is presented to the public.

Audience engagement is another factor that differs between the two. Typically, an audience is more engaged if someone is speaking as this makes use of nonverbal factors, like gestures. Speaking may also provide an opportunity for those in the audience to make suggestions or comments. Written communication doesn't allow for as much engagement. Though some means of written communication, such as blogs or emails, may provide a way for users to engage.

Retention of information is an important factor to consider since it varies between both oral and written communication. Generally, people remember more of what they hear than what they read. Those who read information only retain 10% of the content, while those who hear the information retain 20%. This means oral communication is overall more effective when the purpose is to inform.

Both written communication and oral communication are important and should aim to be accurate. They should be efficient and include good record-keeping if necessary. When it comes to branding, both oral and written communication are important as they can impact whether the audience is interested and whether a company grows.

Written communication is important to provide instructions or important details, such as in product marketing. Oral communication is important for providing clear expression, as well as succinct conversation when necessary. For example, a job description should be written clearly, however, as the job is offered to a candidate, oral communication is important to help clarify the role and responsibilities, as well as to answer any other questions the job candidate might have.

Communication comes in many forms. Oral communication and written communication are two forms that are often compared. Oral communication is the type of communication that takes place through speaking, such as conversations, speeches, and meetings. Written communication is the type of communication that uses the written word., such as emails and letters. Oral communication skills are common in the media, especially radio as it relies heavily on oral communication.

The main difference between oral communication and written communication is the way in which the message is distributed. Other factors that differentiate these types of communication include the preciseness of the message, audience engagement, and retention of the information. Oral communication skills are generally more helpful to generate interest from the audience since it involves nonverbal gestures, as compared to simply reading a transcript of the speech. Speaking to an audience also allows the speaker to make changes and go back to the main points if they don't respond as the speaker expected. In general, people typically remember more of what they hear than what they read, retaining 10% of information that is read and 20% of information that is heard.

Video Transcript

What exactly is oral communication.

There are so many ways we engage in oral communication. In fact, by you watching this video, I am communicating orally with you.

Oral communication is really just talking to others. Through oral communication, you can:

- Share ideas

- Communicate thoughts

- Exchange information

- Give orders

- Persuade people

So, there are many things we can accomplish through oral communication. The same applies to written communication. It's pretty effective as well but in a different way.

So, What Is Written Communication, Then?

Obviously, from its name, written communication means communicating to others through the written word.

This can be done in many ways:

- Text messaging

And the list goes on and on. Now, you'd think that the major differences between oral and written communication would be as obvious, but there are several dissimilarities we will learn next.

Differences: Oral and Written Communication

Suffice it to say, in business, college and everyday life, we need to have both oral and written communication to get what we need to get done, well, done! So, to know which works best for different situations, let's figure out the major differences:

- Preciseness of the message

- Audience engagement

- Retention of the information

Written communication is precise because words are chosen by the writer with great care. Oral communication can be more effective because it involves carefully chosen words along with non-verbal gestures, movements, tone changes and visual cues that keep the audience captivated.

The written word is more organized, more detailed and is presented in a logical order. Speaking before an audience allows one to use less formal language, retract statements and re-generate interest if the audience loses attentiveness.

Writers have less control over the audience or reader's attention because he cannot go back and stress a point that the reader may have missed. Once stated, a speaker can go back to important points if he feels the audience did not respond as expected.

A book writer knows that people remember only about 10% of what they read. A speaker is confident that people remember 20% of what they hear. So, we can safely say that there are major differences between oral and written communication.

To sum it up, oral communication is really just talking to others. Conversely, written communication means communicating to others through the written word.

There are a few major differences between the two forms of communication. Preciseness of the message is stronger in the written word.

In contrast, audience engagement is much easier to direct and re-direct in oral communication. Speakers can use body language and tone to get the audience's attention. And people remember more of what they hear. This does not mean one is better than the other; it really depends on the message and the purpose.

Learning Outcomes

When you're through watching the video, you should have the knowledge to:

- Explain what oral communication is

- Describe written communication

- Differentiate between oral and written communication

Unlock Your Education

See for yourself why 30 million people use study.com, become a study.com member and start learning now..

Already a member? Log In

Recommended Lessons and Courses for You

Related lessons, related courses, recommended lessons for you.

Oral vs Written Communication Skills | Importance & Examples Related Study Materials

- Related Topics

Browse by Courses

- Praxis Family and Consumer Sciences (5122) Prep

- Information Systems: Help and Review

- Introduction to Organizational Behavior: Certificate Program

- UExcel Organizational Behavior: Study Guide & Test Prep

- Introduction to Business: Certificate Program

- UExcel Business Law: Study Guide & Test Prep

- CLEP Introductory Business Law Prep

- Introduction to Business Law: Certificate Program

- College Macroeconomics: Homework Help Resource

- Introduction to Macroeconomics: Help and Review

- DSST Computing and Information Technology Prep

- Business 104: Information Systems and Computer Applications

- Business 102: Principles of Marketing

- Economics 102: Macroeconomics

- GED Social Studies: Civics & Government, US History, Economics, Geography & World

Browse by Lessons

- Global Market Entry, M&A & Exit Strategies

- Entering an International Market | Strategies & Considerations

- Pros & Cons of Outsourcing Global Market Research

- Full Service | Meaning & Examples

- Advertainment History, Types & Examples

- Franchisee in Marketing: Definition & Explanation

- Influencer Marketing | Definition, Role & Importance

- Intangibility in Marketing: Definition & Overview

- Learned Behavior in Marketing: Definition, Types & Examples

- Marketing Orientation: Definition & Examples

- Schedule Variance Formula & Calculation

- Product Placement | Definition, History & Examples

- Stealth Marketing | Definition, Types & Examples

- Strategies for Effective Consumer Relations

- Cross-Selling in Retail: Techniques & Examples

Create an account to start this course today Used by over 30 million students worldwide Create an account

Explore our library of over 88,000 lessons

- Foreign Language

- Social Science

- See All College Courses

- Common Core

- High School

- See All High School Courses

- College & Career Guidance Courses

- College Placement Exams

- Entrance Exams

- General Test Prep

- K-8 Courses

- Skills Courses

- Teacher Certification Exams

- See All Other Courses

- Create a Goal

- Create custom courses

- Get your questions answered

Oral Language and Written Language Are Not the Same Things: Why the Distinction Really Matters When Teaching Literacy to English Learners

Among the most wondrous things about being human is our ability to use language. We’re not the only beings that communicate, of course, but Homo sapiens use human language, which as the evolutionary biologist Mark Pagel has written,

“…is distinct from all other known animal forms of communication in being compositional . Human language allows speakers to express thoughts in sentences comprising subjects, verbs and objects… Human language is also referential , meaning speakers use it to exchange specific information with each other about people or objects and their locations or actions.” (Pagel, 2017, p. 1; emphases in original)

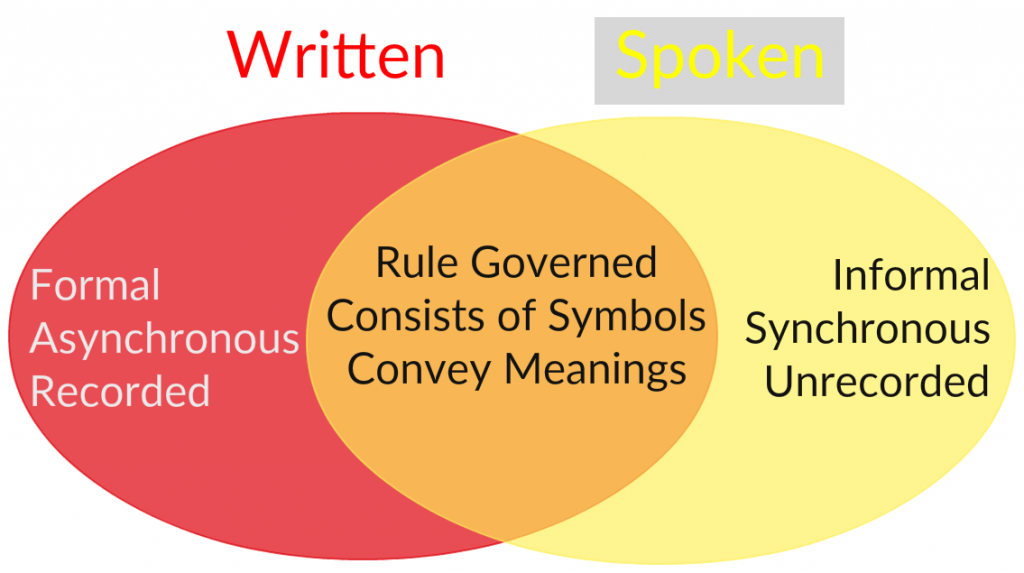

This is true about human language whether it’s oral or written. But there are key differences between oral and written language that have important implications for teaching students to read and write.

These differences are important for all students; they are particularly important for English learners , students who are learning to read and write in English as they simultaneously learn to speak and understand it.

(To be clear, I am referring to English learners in English medium instruction, which is the type of program in which the large majority of English learners are educated in the US. Bilingual education is preferable for many reasons, but most English learners do not have the benefit of a bilingual program. There should be no inference taken that I favor English immersion instruction for these students.)

Language through Speech or Print

Let’s begin with oral language, or more precisely, human speech. Speech is not language itself but how language is conveyed orally. It’s the spoken expression of language.

As humans, we don’t spend any time worrying about the distinction between speech and oral language. When someone is speaking in a language we understand, we focus on what they are trying to communicate.

Young children communicating

Young children know intuitively that speech communicates meaning, and they seek to understand that meaning. Not so with print.

The History of Human Speech & Language

Aspects of human speech and language have been around for far longer than writing, perhaps as much as half a million years or more longer (Evans, 2015; King, 2013). Humans are wired to learn to speak and to understand spoken speech, just as birds are wired to fly, fish to swim, and so forth.

Given an environment where people are talking, and assuming no brain injury or congenital disability, human babies will learn to speak as they enter toddlerhood. Even before, they will use gestures and signals to communicate, along with verbalizations. There is a communicative imperative with which each of us is born, injuries or disabilities aside.

Famed developmental psychologist T.G.R. Bower observed that it’s obvious we “have some biological predispositions toward speech, … even at birth. Neonates are more attentive to speech than to any other stimulus” (p. 228).

The Emergence of the Written Language

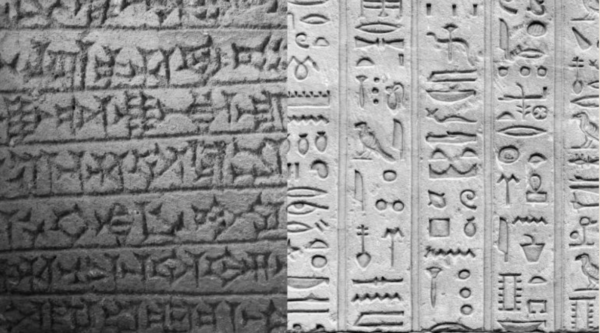

Written language is different. Rather than dating back to the time of the appearance of modern humans around 300,000 years ago, written language first appeared in Sumeria a short 5,000 years ago. The written language was cuneiform, sometimes known as hieroglyphics, which is what the Egyptians used. Cuneiform, or hieroglyphics, represented concepts (picture below).

Cuneiform (left) and hieroglyphics represented concepts

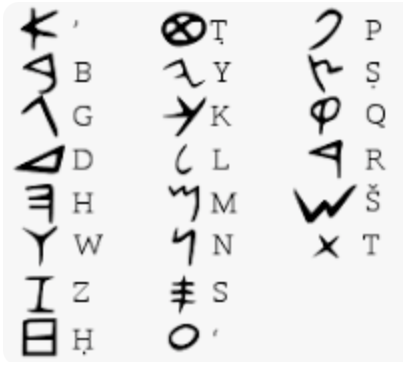

A different type of written language emerged somewhat later, one in which speech sounds were represented by letters. This phonetic writing system—”phoenetic” from the Greek phonein —”to speak clearly”—was courtesy of the Phoenicians (Mark, 2011) (see pictures below).

Examples above of phonetic writing

Writing systems—“the physical manifestation of a spoken language” (Mark, 2011)—are a relatively recent arrival in human history. They are cultural inventions rather than part of human evolution. We don’t intuitively understand that print represents sounds that then carry meaning. We are certainly not born with a literacy imperative.

There are societies without written language and situations with nonliterate environments where there are nonliterate children and adults. In contrast, human speech and oral language is universal; there are no known alingual societies (Bright, 2022).

We take written language for granted because it is so ubiquitous in our world, but we should not underestimate the challenge of helping all individuals acquire literacy. We can’t assume that literacy will somehow happen by itself, even if we were to flood every last home, school, and community with mountains of books.

Book flooding would be a welcome development. But alone it would not accomplish universal literacy.

Literacy—the ability to read the printed text and produce written language—needs to be taught.

Literacy is not acquired “naturally” as is oral language, although there are certainly instances of children who appear to learn to read naturally, by themselves, with virtually no human interaction. These are the exceptions; different studies provide estimates ranging from one to seven percent of children. But even here some amount of instruction or help, often at the instigation of the child, is probably necessary for so-called “precocious” or “early” readers to understand comprehensively how speech sounds are represented in print (Olson, Evans, & Keckler, 2006).

The “Speech to Print” Connection: How to Teach All Children to be Literate

To become literate, all students need to learn how speech sounds are represented in print. There is simply no getting around this. The “speech to print” connection (Moats, 2020) it the gateway to literacy.

Children vary enormously in how much help or instruction they need. Some need very little; others need a great deal; the majority are somewhere in between. This range of difficulties students experience in learning to read is common across all languages (Fletcher et al., 2019). Moreover, full literacy requires the ability to process print—written language—very quickly, efficiently, and automatically, what the neuroscientist Mark Seidenberg calls “language at the speed of sight” (Seidenberg, 2017).

Regardless of the range of difficulties students encounter, students who are proficient in the language they are learning to read enjoy advantages: The sounds of the language are familiar and the words are already meaningful, though as noted, it’s more straightforward for some than for others.

In general, students who know the oral language learn letters, corresponding sounds, and how to use phonics and decoding skills to read words. They can typically then use their knowledge of the words they are learning to read (e.g., see, run, I, can) to help them recognize words, confirm their accuracy (“does that word make sense there?”), and gain useful practice in connecting speech to print with a steadily increasing repertoire of words and text.

Language Development for English Learners

English learners need to learn exactly the same thing as English speakers in order to learn to read in English— how the speech sounds of English are represented in print .

But the task for English learners is more challenging, and they need an additional and critical area of support: English language development that teaches them unfamiliar sounds of English and the meanings of words and text they are learning to read (Goldenberg, 2020).

Without this support, at best they can learn to read by rote. But even this is more challenging, since understanding the words you are reading makes it easier to read and recognize them. As students go up the grades, not understanding words they are reading becomes an ever-increasing barrier to literacy development and to academic and language development generally.

Beyond beginning and early literacy, English learners will need continued support in additional aspects of English language and literacy development, e.g., advanced word recognition skills, morphology, syntax, discourse and pragmatic skills and understandings, and increasing fluency in using these all to navigate written language successfully. Background knowledge also becomes increasingly important for both oral and written language competence as students progress through school.

There are other differences between oral and written language, of course, differences in style, construction, and register, among others. But from the standpoint of learning to become literate, the most fundamental difference has to do with how spoken language and written language are acquired.

Particularly in the case of a first language, acquisition is generally natural and effortless. Learning written language, particularly one you are simultaneously learning to speak and understand, is not natural and rarely effortless. For both English speakers and English learners, the foundational skills that connect speech to print (i.e., phonological awareness, letters and sounds, phonics, decoding, basic spelling patterns, and fluency with all) are essential—necessary but not sufficient. A great deal more is needed for full literacy, but being without solid foundational skills is like living in a building without a solid foundation—possible but risky.

Special thanks to David Burns for his helpful feedback on a previous version.

Bower, T.G.R. (1979). Human development. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman.

Bright, W. (2022). What’s the difference between speech and writing? Linguistic Society of America . https://www.linguisticsociety.org/resource/whats-difference-between-speech-and-writing

Evans, V. (2015, Feb. 19) How Old Is Language? Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/language-in-the-mind/201502/how-old-is-language

Fletcher, J., Lyon, G., Fuchs, L., & Barnes, M.. (2019). Learning disabilities: From identification to intervention (2 nd ed.) New York: Guilford.

Goldenberg, C. (2020). Reading wars, reading science, and English Learners. Reading Research Quarterly, 55 (S1), S131–S144. https://ila.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/rrq.340

King, B. (2013, Sept. 5) When Did Human Speech Evolve? National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/sections/13.7/2013/09/05/219236801/when-did-human-speech-evolve

Mark, J. (2011). Writing. World History Encyclopedia. http://www.ancient.eu/writing/

Moats, L. (2020). Speech to print: Language essentials for teachers (3 rd ed). Baltimore, Md.: Paul H. Brookes.

Olson, L., Evans, J., & Keckler, W. (2006). Precocious readers: Past, present, and future. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 30(2), 205–235.

Pagel, M. (2017). Q&A: What is human language, when did it evolve and why should we care?. BMC Biol 15 , 64 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-017-0405-3 .

Seidenberg, M. (2017). Language at the speed of sight. New York: Basic Books.

Illuminate Education equips educators to take a data-driven approach to serving the whole child. By combining comprehensive assessment and MTSS management and collaboration tools, the Illuminate Solution enables educators to accurately assess learning, identify needs, align whole child supports, drive system-level improvements, and equitably accelerate growth for every learner.

Ready to discover your one-stop shop for your district’s educational needs? Let’s talk .

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Spoken vs. Written Language

Spoken vs. written language (pdf).

Office / Department Name

Oral Communication Center

Contact Name

Amy Gaffney

Oral Communication Center Director

Help us provide an accessible education, offer innovative resources and programs, and foster intellectual exploration.

Site Search

Differences Between Oral and Written Language

You may have noticed that words and sentences that are spoken aloud can come across quite differently from words that you read to yourself. In a public speaking context, the difference between spoken and written language can be even more pronounced. To help you craft better language for your speeches, consider these three key differences between oral and written language:

Oral language is more adaptive . Writers seldom know exactly who will read their words or in what context. The best they can do is to take educated guesses and make language choices accordingly. When you speak before a live audience, however, you can get immediate feedback, which is virtually impossible for a writer. Thus, you can observe your audience members during your presentation, interact with them, and respond to the way they are receiving your message. Because a speech is a live, physical interaction that generates instantaneous audience feedback, you can adapt to the situation, such as by extending or simplifying an explanation if listeners seem confused or by choosing clearer or simpler language.

Oral language tends to be less formal . Because writers have the luxury of getting their words down on paper (or on screen) and then going back to make changes, they typically use precise word choice and follow the formal rules of syntax and grammar. This careful use of language aligns well with most readers’ expectations. In most speech situations, however, language choice tends toward a somewhat less formal style. Because listeners lack the chance to go back and reread your words, you will want to use shorter and less complicated sentences. (Of course, certain speech situation s— such as political setting s— require elevated sentence structure and word choice.) In addition, effective oral language is often simpler and less technically precise than written language is. Thus, consider incorporating appropriate colloquialisms, a conversational tone, and even sentence fragments into your speeches.

Oral language incorporates repetition . Most writing teachers and coaches advise their students to avoid repeating themselves or being redundant by covering the same ground more than once. But in speaking situations, repetition can be an especially effective tool because your listeners can’t go back and revisit your points: your words are there and then suddenly are gone. Because most audience members don’t take notes (especially outside a classroom setting), there is nothing for listeners to rely on except their own memory of your words. You can help your listeners remember your message by intentionally repeating key words and phrases throughout your presentation. If they hear certain words often enough, they will remember them.

Difference Between | Descriptive Analysis and Comparisons

Search form, difference between oral communication and written communication.

Key Difference: Oral and written communications are both major forms of communication. Communicating by word of mouth is termed as oral communication. Written communication involves writing/drawing symbols in order to communicate.

One can understand oral communication simply as a verbally spoken conversation. It is the routine words and sentences that we use in conveying our feelings, desires, emotions, etc. to the people around us. Oral communication as a term may refer to two individuals participating in a conversation, such as a face-to-face chat, discussion, etc. Or, it could mean a group of people talking amongst themselves, like a meeting, a convention, etc. Oral communication may also mean an individual communicating to a large audience, as it happens in a speech, or a public presentation. Apart from voicing out one’s feelings and emotions, oral communication is also largely influenced by body language. Appearing trivial in nature, things such as body gait, posture, eye contact, etc. can influence an oral conversation as much as speaking the right words in the right manner does.

Written communication is considered as the preferred form of communication, when it comes to government undertakings, official work, formal agreements, etc. This is because written communication is more suitable to be effectively implemented in such scenarios, than oral communication. For instance, written communication provides the facility of recording any piece of communication, as it is always in written form, while oral communication cannot. In this day and age, oral communication can also be recorded using the various means of technology, but oral communication is not always recorded. Whereas, written communication is always in a recorded form. This is the reason why written communication holds an edge over oral communication in legal and formal circumstances. Written communication not only enables a person to relive and remember a conversation exactly, but also to present it as evidence, in case he/she is in a spot of bother.

However, the fact which remains is that both oral and written forms of communication are indispensable to the human society in its day to day life.

Comparison between Oral and Written Communication:

|

|

|

|

| Meaning | Communicating by word of mouth is termed as oral communication. | Written communication involves writing/drawing symbols in order to communicate. |

| Permanency | Oral communication can be altered or corrected after saying. | Once written, it is recorded. So the communication either has to be erased or written anew. |

| Applicability | Oral communication is mostly used for immediate confrontations. | Written communication is usually not preferred for face to face communications. |

| Longevity | Oral communications tend to be forgotten quite easily and quickly. | Written communications are always recorded, so they stand the test of time. |

| Feedback | Oral communication attracts instant feedback from the listeners. | Written communication doesn’t normally receive immediate feedback, unless it’s on the internet or electronic. |

| Expression | Speakers use their baritone, sound pitch, volume alteration to convey certain expressions to the listeners. | Writers use specific words, punctuation marks, etc. to easily put an expression across in the text. |

| Grammar | Normally, grammar is not paid much attention to in oral communication. | Being grammatically correct is one of the requisites for effective written communication. |

Image Courtesy: eportfolio.lagcc.cuny.edu, synout.co.za

Add new comment

Copyright © 2024, Difference Between | Descriptive Analysis and Comparisons

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter Twelve – Language Use

Oral versus written language.

Clemsonunivlibrary – group meeting – CC BY-NC 2.0.

When we use the word “language,” we are referring to the words you choose to use in your speech—so by definition, our focus is on spoken language. Spoken language has always existed prior to written language. Wrench, McCroskey, and Richmond suggested that if you think about the human history of language as a twelve-inch ruler, written language or recorded language has only existed for the “last quarter of an inch” [1] . Furthermore, of the more than six thousand languages that are spoken around the world today, only a minority of them actually use a written alphabet [2] . To help us understand the importance of language, we will first look at the basic functions of language and then delve into the differences between oral and written language.

Basic Functions of Language

Language is any formal system of gestures, signs, sounds, and symbols used or conceived as a means of communicating thought. As mentioned above, there are over six thousand language schemes currently in use around the world. The language spoken by the greatest number of people on the planet is Mandarin; other widely spoken languages are English, Spanish, and Arabic [3] . Language is ultimately important because it is the primary means through which humans have the ability to communicate and interact with one another. Some linguists go so far as to suggest that the acquisition of language skills is the primary advancement that enabled our prehistoric ancestors to flourish and succeed over other hominid species [4] .

In today’s world, effective use of language helps us in our interpersonal relationships at home and at work. Using language effectively also will improve your ability to be an effective public speaker. Because language is an important aspect of public speaking that many students don’t spend enough time developing, we encourage you to take advantage of this chapter.

One of the first components necessary for understanding language is to understand how we assign meaning to words. Words consist of sounds (oral) and shapes (written) that have agreed-upon meanings based in concepts, ideas, and memories. When we write the word “blue,” we may be referring to a portion of the visual spectrum dominated by energy with a wavelength of roughly 440–490 nanometers. You could also say that the color in question is an equal mixture of both red and green light. While both of these are technically correct ways to interpret the word “blue,” we’re pretty sure that neither of these definitions is how you thought about the word. When hearing the word “blue,” you may have thought of your favorite color, the color of the sky on a spring day, or the color of a really ugly car you saw in the parking lot. When people think about language, there are two different types of meanings that people must be aware of: denotative and connotative.

Denotative Meaning

The denotative meaning is the specific meaning associated with a word. We sometimes refer to denotative meanings as dictionary definitions. The definitions provided above for the word “blue” are examples of definitions that might be found in a dictionary. The first dictionary was written by Robert Cawdry in 1604 and was called Table Alphabeticall . This dictionary of the English language consisted of three thousand commonly spoken English words. Today, the Oxford English Dictionary contains more than 200,000 words [6] .

Connotative Meaning

The connotative meaning is the idea suggested by or associated with a word. In addition to the examples above, the word “blue” can evoke many other ideas:

- State of depression (feeling blue)

- Indication of winning (a blue ribbon)

- Side during the Civil War (blues vs. grays)

- Sudden event (out of the blue)

We also associate the color blue with the sky and the ocean. Maybe your school’s colors or those of your archrival include blue. There are also various forms of blue: aquamarine, baby blue, navy blue, royal blue, and so on.

Some miscommunication can occur over denotative meanings of words. For example, a flyer for a tennis center open house expressed the goal of introducing children to the game of tennis. At the bottom of the flyer, people were encouraged to bring their own racquets if they had them but that “a limited number of racquets will be available.” It turned out that the denotative meaning of the final phrase was interpreted in multiple ways: some parents attending the event perceived it to mean that loaner racquets would be available for use during the open house event, but the people running the open house intended it to mean that parents could purchase racquets onsite. The confusion over denotative meaning probably hurt the tennis center, as some parents left the event feeling they had been misled by the flyer.

Although denotatively based misunderstanding such as this one do happen, the majority of communication problems involving language occur because of differing connotative meanings. You may be trying to persuade your audience to support public funding for a new professional football stadium in your city, but if mentioning the team’s or owner’s name creates negative connotations in the minds of audience members, you will not be very persuasive. The potential for misunderstanding based in connotative meaning is an additional reason why audience analysis, discussed earlier in this book, is critically important. By conducting effective audience analysis, you can know in advance how your audience might respond to the connotations of the words and ideas you present. Connotative meanings can not only differ between individuals interacting at the same time but also differ greatly across time periods and cultures. Ultimately, speakers should attempt to have a working knowledge of how their audiences could potentially interpret words and ideas to minimize the chance of miscommunication.

Twelve Ways Oral and Written Language Differ

A second important aspect to understand about language is that oral language (used in public speaking) and written language (used for texts) does not function the same way. Try a brief experiment. Take a textbook, maybe even this one, and read it out loud. When the text is read aloud, does it sound conversational? Probably not. Public speaking, on the other hand, should sound like a conversation. McCroskey, Wrench, and Richmond highlighted the following twelve differences that exist between oral and written language:

- Oral language has a smaller variety of words.

- Oral language has words with fewer syllables.

- Oral language has shorter sentences.

- Oral language has more self-reference words ( I , me , mine ).

- Oral language has fewer quantifying terms or precise numerical words.

- Oral language has more pseudo-quantifying terms ( many , few , some ).

- Oral language has more extreme and superlative words ( none , all , every , always , never ).

- Oral language has more qualifying statements (clauses beginning with unless and except ).

- Oral language has more repetition of words and syllables.

- Oral language uses more contractions.

- Oral language has more interjections (“Wow!,” “Really?,” “No!,” “You’re kidding!”).

- Oral language has more colloquial and nonstandard words (McCroskey, et al., 2003).

These differences exist primarily because people listen to and read information differently. First, when you read information, if you don’t grasp content the first time, you have the ability to reread a section. When we are listening to information, we do not have the ability to “rewind” life and relisten to the information. Second, when you read information, if you do not understand a concept, you can look up the concept in a dictionary or online and gain the knowledge easily. However, we do not always have the ability to walk around with the Internet and look up concepts we don’t understand. Therefore, oral communication should be simple enough to be easily understood in the moment by a specific audience, without additional study or information.

Using Language Effectively

Kimba Howard – megaphone – CC BY 2.0.

When considering how to use language effectively in your speech, consider the degree to which the language is appropriate, vivid, inclusive, and familiar. The next sections define each of these aspects of language and discuss why each is important in public speaking.

Use Appropriate Language

As with anything in life, there are positive and negative ways of using language. One of the first concepts a speaker needs to think about when looking at language use is appropriateness. By appropriate, we mean whether the language is suitable or fitting for ourselves, as the speaker; our audience; the speaking context; and the speech itself.

Appropriate for the Speaker

One of the first questions to ask yourself is whether the language you plan on using in a speech fits with your own speaking pattern. Not all language choices are appropriate for all speakers. The language you select should be suitable for you, not someone else. If you’re a first-year college student, there’s no need to force yourself to sound like an astrophysicist even if you are giving a speech on new planets. One of the biggest mistakes novice speakers make is thinking that they have to use million-dollar words because it makes them sound smarter. Actually, million-dollar words don’t tend to function well in oral communication to begin with, so using them will probably make you uncomfortable as a speaker. Also, it may be difficult for you or the audience to understand the nuances of meaning when you use such words, so using them can increase the risk of denotative or connotative misunderstandings.

Appropriate for the Audience

The second aspect of appropriateness asks whether the language you are choosing is appropriate for your specific audience. Let’s say that you’re an engineering student. If you’re giving a presentation in an engineering class, you can use language that other engineering students will know. On the other hand, if you use that engineering vocabulary in a public speaking class, many audience members will not understand you. As another example, if you are speaking about the Great Depression to an audience of young adults, you can’t assume they will know the meaning of terms like “New Deal” and “WPA,” which would be familiar to an audience of senior citizens. In other chapters of this book, we have explained the importance of audience analysis; once again, audience analysis is a key factor in choosing the language to use in a speech.

Appropriate for the Context

The next question about appropriateness is whether the language you will use is suitable or fitting for the context itself. The language you may employ if you’re addressing a student assembly in a high school auditorium will differ from the language you would use at a business meeting in a hotel ballroom. If you’re giving a speech at an outdoor rally, you cannot use the same language you would use in a classroom. Recall that the speaking context includes the occasion, the time of day, the mood of the audience, and other factors in addition to the physical location. Take the entire speaking context into consideration when you make the language choices for your speech.

Appropriate for the Topic

The fourth and final question about the appropriateness of language involves whether the language is appropriate for your specific topic. If you are speaking about the early years of The Walt Disney Company, would you want to refer to Walt Disney as a “thaumaturgic” individual (i.e., one who works wonders or miracles)? While the word “thaumaturgic” may be accurate, is it the most appropriate for the topic at hand? As another example, if your speech topic is the dual residence model of string theory, it makes sense to expect that you will use more sophisticated language than if your topic was a basic introduction to the physics of, say, sound or light waves.

Use Vivid Language

After appropriateness, the second main guideline for using language is to use vivid language . Vivid language helps your listeners create strong, distinct, clear, and memorable mental images. Good vivid language usage helps an audience member truly understand and imagine what a speaker is saying. Two common ways to make your speaking more vivid are through the use of imagery and rhythm.

Imagery is the use of language to represent objects, actions, or ideas. The goal of imagery is to help an audience member create a mental picture of what a speaker is saying. A speaker who uses imagery successfully will tap into one or more of the audience’s five basic senses (hearing, taste, touch, smell, and sight). Three common tools of imagery are concreteness, simile, and metaphor.

Concreteness

We have previously discussed the importance of concrete language. When we use language that is concrete, we attempt to help our audiences see specific realities or actual instances instead of abstract theories and ideas. The goal of concreteness is to help you, as a speaker, show your audience something instead of just telling them. Imagine you’ve decided to give a speech on the importance of freedom. You could easily stand up and talk about the philosophical work of Rudolf Steiner, who divided the ideas of freedom into freedom of thought and freedom of action. If you’re like us, even reading that sentence can make you want to go to sleep. Instead of defining what those terms mean and discussing the philosophical merits of Steiner, you could use real examples where people’s freedom to think or freedom to behave has been stifled. For example, you could talk about how Afghani women under Taliban rule have been denied access to education, and how those seeking education have risked public flogging and even execution [7] . You could further illustrate how Afghani women under the Taliban are forced to adhere to rigid interpretations of Islamic law that functionally limit their behavior. As illustrations of the two freedoms discussed by Steiner, these examples make things more concrete for audience members and thus easier to remember. Ultimately, the goal of concreteness is to show an audience something instead of talking about it abstractly.

Another form of imagery is simile . As you likely learned in English courses, a simile is a figure of speech in which two unlike things are explicitly compared. Both aspects being compared within a simile are able to remain separate within the comparison. The following are some examples:

- The thunderous applause was like a party among the gods.

- After the revelation, she was as angry as a raccoon caught in a cage.

- Love is like a battlefield.

When we look at these two examples, you’ll see that two words have been italicized: “like” and “as.” All similes contain either “like” or “as” within the comparison. Speakers use similes to help an audience understand a specific characteristic being described within the speech. In the first example, we are connecting the type of applause being heard to something supernatural, so we can imagine that the applause was huge and enormous. Now think how you would envision the event if the simile likened the applause to a mime convention—your mental picture changes dramatically, doesn’t it?

To effectively use similes within your speech, first look for instances where you may already be finding yourself using the words “like” or “as”—for example, “his breath smelled like a fishing boat on a hot summer day.” Second, when you find situations where you are comparing two things using “like” or “as,” examine what it is that you are actually comparing. For example, maybe you’re comparing someone’s breath to the odor of a fishing vessel. Lastly, once you see what two ideas you are comparing, check the mental picture for yourself. Are you getting the kind of mental image you desire? Is the image too strong? Is the image too weak? You can always alter the image to make it stronger or weaker depending on what your aim is.

The other commonly used form of imagery is the metaphor, or a figure of speech where a term or phrase is applied to something in a nonliteral way to suggest a resemblance. In the case of a metaphor, one of the comparison items is said to be the other (even though this is realistically not possible).

Metaphors are comparisons made by speaking of one thing in terms of another. Similes are similar to metaphors in how they function; however, similes make comparisons by using the word “like” or “as,” whereas metaphors do not. Let’s look at a few examples:

- Love is a battlefield .

- Upon hearing the charges, the accused clammed up and refused to speak without a lawyer.

- Every year a new crop of activists are born .

In these examples, the comparison word has been italicized. Let’s think through each of these examples. In the first one, the comparison is the same as one of our simile examples except that the word “like” is omitted—instead of being like a battlefield, the metaphor states that love is a battlefield, and it is understood that the speaker does not mean the comparison literally. In the second example, the accused “clams up,” which means that the accused refused to talk in the same way a clam’s shell is closed. In the third example, we refer to activists as “crops” that arise anew with each growing season, and we use “born” figuratively to indicate that they come into being—even though it is understood that they are not newborn infants at the time when they become activists.

To use a metaphor effectively, first determine what you are trying to describe. For example, maybe you are talking about a college catalog that offers a wide variety of courses. Second, identify what it is that you want to say about the object you are trying to describe. Depending on whether you want your audience to think of the catalog as good or bad, you’ll use different words to describe it. Lastly, identify the other object you want to compare the first one to, which should mirror the intentions in the second step. Let’s look at two possible metaphors:

- Students groped their way through the maze of courses in the catalog.

- Students feasted on the abundance of courses in the catalog.

While both of these examples evoke comparisons with the course catalog, the first example is clearly more negative and the second is more positive.

One mistake people often make in using metaphors is to make two incompatible comparisons in the same sentence or line of thought. Here is an example:

- “That’s awfully thin gruel for the right wing to hang their hats on.” [9]

This is known as a mixed metaphor, and it often has an incongruous or even hilarious effect. Unless you are aiming to entertain your audience with fractured use of language, be careful to avoid mixed metaphors.

The power of a metaphor is in its ability to create an image that is linked to emotion in the mind of the audience.

For example, it is one thing to talk about racial injustice, it is quite another for the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to note that people have been “…battered by storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality.” Throughout his “ I Have a Dream ” speech, the Reverend Dr. King uses the metaphor of the checking account to make his point.

He notes that the crowd has come to the March on Washington to “cash a check” and claims that America has “defaulted on this promissory note” by giving “the Negro people a bad check, a check that has come back “insufficient funds.” By using checking and bank account terms that most people are familiar with, the Reverend Dr. King is able to more clearly communicate what he believes has occurred. In addition, the use of this metaphor acts as a sort of “shortcut.” He gets his point across very quickly by comparing the problems of civil rights to the problems of a checking account.

In the same speech the Reverend Dr. King also makes use of similes, which also compare two things but do so using “like” or “as.” In discussing his goals for the Civil Rights movement in his “I Have a Dream” speech, the Reverend Dr. exclaims: “No, no we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.” Similes also help make your message clearer by using ideas that are more concrete for your audience. For example, to give the audience an idea of what a winter day looked like you could note that the “snow looked as solid as pearls.” To communicate sweltering heat, you could say that “the tar on the road looked like satin.” A simile most of us are familiar with is the notion of the United States being “like a melting pot” with regard to its diversity. We also often note that a friend or colleague that stays out of conflicts between friends is “like Switzerland.” In each of these instances, similes have been used to more clearly and vividly communicate a message.

Our second guideline for effective language in a speech is to use rhythm. When most people think of rhythm, they immediately think about music. What they may not realize is that language is inherently musical; at least it can be. Rhythm refers to the patterned, recurring variance of elements of sound or speech. Whether someone is striking a drum with a stick or standing in front of a group speaking, rhythm is an important aspect of human communication. Think about your favorite public speaker. If you analyze their speaking pattern, you’ll notice that there is a certain cadence to the speech. While much of this cadence is a result of the nonverbal components of speaking, some of the cadence comes from the language that is chosen as well. Let’s examine types of rhythmic language: parallelism, antithesis, repetition, alliteration, and assonance.

Parallelism

When listing items in a sequence, audiences will respond more strongly when those ideas are presented in a grammatically parallel fashion, which is referred to as parallelism. For example, look at the following two examples and determine which one sounds better to you:

- “Give me liberty or I’d rather die.”

- “Give me liberty or give me death.”

Technically, you’re saying the same thing in both, but the second one has better rhythm, and this rhythm comes from the parallel construction of “give me.” The lack of parallelism in the first example makes the sentence sound disjointed and ineffective.

Antithesis allows you to use contrasting statements in order to make a rhetorical point. Perhaps the most famous example of antithesis comes from the Inaugural Address of President John F. Kennedy when he stated, “And so, my fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” In Reverend Jackson’s “ Rainbow Coalition ” speech he notes, “I challenge them to put hope in their brains and not dope in their veins.” In each of these cases, the speakers have juxtaposed two competing ideas in one statement to make an argument in order to draw the listener’s attention.

You’re easy on the eyes — hard on the heart. – Terri Clark

Parallel Structure and Language

Antithesis is often worded using parallel structure or language. Parallel structure is the balance of two or more similar phrases or clauses, and parallel wording is the balance of two or more similar words. The Reverend Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech exemplifies both strategies in action. Indeed, the section where he repeats “I Have a Dream” over and over again is an example of the use of both parallel structure and language. The use of parallel structure and language helps your audience remember without beating them over the head with repetition. If worded and delivered carefully, you can communicate a main point over and over again, as did the Reverend Dr. King, and it doesn’t seem as though you are simply repeating the same phrase over and over. You are often doing just that, of course, but because you are careful with your wording (it should be powerful and creative, not pedantic) and your delivery (the correct use of pause, volumes, and other elements of delivery), the audience often perceives the repetition as dramatic and memorable. The use of parallel language and structure can also help you when you are speaking persuasively. Through the use of these strategies, you can create a speech that takes your audience through a series of ideas or arguments that seem to “naturally” build to your conclusion.

As we mentioned earlier in this chapter, one of the major differences between oral and written language is the use of repetition. Because speeches are communicated orally, audience members need to hear the core of the message repeated consistently. Repetition as a linguistic device is designed to help audiences become familiar with a short piece of the speech as they hear it over and over again. By repeating a phrase during a speech, you create a specific rhythm. Probably the most famous and memorable use of repetition within a speech is Martin Luther King Jr.’s use of “I have a dream” in his speech at the Lincoln Memorial on August 1963 during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. In that speech, Martin Luther King Jr. repeated the phrase “I have a dream” eight times to great effect. If worded and delivered carefully, you can communicate a main point over and over again, as did the Reverend Dr. King, and it doesn’t seem as though you are simply repeating the same phrase over and over. Because you are careful with your wording (it should be powerful and creative, not pedantic) and your delivery (the correct use of pause, volumes, and other elements of delivery), the audience often perceives the repetition as dramatic and memorable.

Alliteration

Another type of rhythmic language is alliteration or repeating two or more words in a series that begin with the same consonant. In the Harry Potter novel series, the author uses alliteration to name the four wizards who founded Hogwarts School for Witchcraft and Wizardry: Godric Gryffindor, Helga Hufflepuff, Rowena Ravenclaw, and Salazar Slytherin. There are two basic types of alliteration: immediate juxtaposition and nonimmediate juxtaposition. Immediate juxtaposition occurs when the consonants clearly follow one after the other—as we see in the Harry Potter example. Nonimmediate juxtaposition occurs when the consonants are repeated in nonadjacent words (e.g., “It is the p oison that we must p urge from our p olitics, the wall that we must tear down before the hour grows too late”) [11] . Sometimes you can actually use examples of both immediate and nonimmediate juxtaposition within a single speech. The following example is from Bill Clinton’s acceptance speech at the 1992 Democratic National Convention: “Somewhere at this very moment, a child is b eing b orn in America. Let it be our cause to give that child a h appy h ome, a h ealthy family, and a h opeful future” [7] .

Assonance is similar to alliteration, but instead of relying on consonants, assonance gets its rhythm from repeating the same vowel sounds with different consonants in the stressed syllables. The phrase “how now brown cow,” which elocution students traditionally used to learn to pronounce rounded vowel sounds, is an example of assonance. While rhymes like “free as a breeze,” “mad as a hatter,” and “no pain, no gain” are examples of assonance, speakers should be wary of relying on assonance because when it is overused it can quickly turn into bad poetry.

Personalized Language

We’re all very busy people. Perhaps you’ve got work, studying, classes, a job, and extracurricular activities to juggle. Because we are all so busy, one problem that speakers often face is trying to get their audience interested in their topic or motivated to care about their argument. A way to help solve this problem is through the use of language that personalizes your topic. Rather than saying, “One might argue” say “You might argue.” Rather than saying “This could impact the country in ways we have not yet imagined,” say “This could impact your life in ways that you have not imagined.” By using language that directly connects your topic or argument to the audience you better your chances of getting your audience to listen and to be persuaded that your subject matter is serious and important to them. Using words like “us,” “you,” and “we” can be a subtle means of getting your audience to pay attention to your speech. Most people are most interested in things that they believe impact their lives directly—make those connections clear for your audience by using personal language.

Use Inclusive Language

Language can either inspire your listeners or turn them off very quickly. One of the fastest ways to alienate an audience is through the use of non-inclusive language. Inclusive language that avoids placing any one group of people above or below other groups while speaking. Let’s look at some common problem areas related to language about gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and disabilities.

Gender-Specific Language

The first common form of non-inclusive language is language that privileges one of the sexes over the other. There are three common problem areas that speakers run into while speaking: using “he” as generic, using “man” to mean all humans, and gender typing jobs.

Generic “He”