Importance of Organ Donation Essay (Critical Writing)

Most people see dilemmas when handling matters concerning organ donation and transplantation. In a real sense, this issue can, and still sounds difficult if we don’t try to be realistic. Depending on our different cultural beliefs, many people oppose the idea of organ donation. However, some view organ donation as a heroic decision and socially acceptable activity based on the notion of helping to save a life. Such positive notions and beliefs about organ donation must be advanced to increase the number of those signing up for organ donation programs in Michigan and other states. The government has tried its best to help and boost organ donation through a number of initiatives, and people would be helpful if they considered the importance of organ donation and responded positively. In Michigan, people willing to donate organs can now freely do so by starting to give their names to the Michigan Organ Donor Registry (Department of State, 2008).

Considering the huge number of people in need of different body organs today, and the many that are dying each day due to organ problems, a socially upright member of our society should not consider it a big issue to donate an organ to a recipient who is in danger of dying.I really consider it a life-saving process that everyone should also heed. Data is alarming on the number of organ recipients. According to the UNOS-United Network for Organs Sharing-research, every 16 minutes, a new name is added to the national transplant waiting list. The same source indicated that there were about 53,000 patients waiting for transplantation. That was by 1998. A huge number of Americans totaling 55,000 are awaiting organs recipient. In 1996 almost 1000 people died waiting liver transplantation in America and more than 9,800 are waiting it currently.This means that without having good hearted people willing to donate organs to the needing recipient there is a danger of loosing many people each year as a result of organic problems (Prange, 1998). Currently, Michigan is in dire need of volunteers who wish to save life by rendering their organs for donation.

It’s actually important and very necessary to do anything to make sure that you help to have somebody survive death.According to our different religion backgrounds, we are taught the importance of life and that’s why I consider it important to help those in need of different organ problems, by rendering our parts to help them live. It is time people did away with the negative notions and questions posited against organ donating, and possibly consider it in a different perspective-such as if they were the recipient. When handling such issues like organ donation, many questions may arise in our mind, such as what would happen to our tender bodies after some of our organs are taken out? It’s actually a shock to many, but if we look into our society, many people who have donated organs are there and breathing well. It is amazing that someone may think twice while donating an organ yet the same person would not do so to receive one.

In my opinion, we all should some times be at a position of doing what we would like others to do for our selves. This is an important initiative that would make our society to grow. It’s always good to help those in need than to need help. That does not mean that we should not care while donating our organs. We are still responsible and whole responsible for our lives. After all, no body has an extra organ and therefore the issue must be viewed at the perspective of donor’s sacrifice. Therefore, there are different things that we should consider before donating our organs to recipients. Such include our current health status and the status after donation. By doing so, we are at a better position of examining it, and coming up with a clear decision on whether to give or not. For example, there would be no need for a medically fit person to donate a body organ to save life and after some few days die. Also the state of mind as far as the donation is concerned. Is your mind ready to help by donating? Brain is the controller of every thing in the human body and so it might happen that without the consent of brain, some things as crucial as surgical operations that are a must during transplantation would bring out issues. But what could save a great deal is the changing of our attitudes to accommodate organ donation in our lives.

The final decision to donate an organ may be influenced by a wide range of factors. It is a good idea to consult medical experts before engaging yourself in organ donation for medical advice. Doctors may advise you to go ahead and donate, or drop your idea if at all your body is not at a position of donating. They may also advise on the type of meals that a donor of an organ should feed on to avoid future injuries in the body.

Sharing ideas of your intention to donate with friends and relatives is another important issue. Members of the family willing to donate an organ or at a position to must be spoken to before the donation (Hubpages, 2010), and if a positive word is given, this person may give in. By doing so one is at a position of hearing their views as far as this mater is concerned.

Having known scientific facts that an organ of a person about to die with an early harvesting and proper preservation can be transplanted to a recipient, I find it important to be done, but with the owners consent. Saving a life is good than to loose two. And if one is in any way going to die in few hours, I think it’s necessary to use that chance to ensure that another life is saved. It is a good thing for people to know the importance of organ donation as a way of saving live.

Organ donation is the most tremendous gift one can receive today. Everyone should put this into consideration. It’s a socially upright thing to think of becoming an organ donor, since nobody knows if you may estate from being an organ donor today and tomorrow becomes an organ recipient.

To those that have in one way or the other received or given their body organs, they portray a good heroic example of human acts since, for example, one organ from one person can save up to 50 people (MedlinePlus, 2009). This can lead to saving many lives that would otherwise have been lost. In Michigan, a positive attitude towards organ donation would assist the many people in need, and would be a heroic move.

I want to call upon people to save life today by signing for organ donation. This is not enough. A call to every one to join in donating and campaigning to mobilize the mass on the importance of it, and this is an extended hand. Further more, such disasters can only be eliminated by nothing lesser than rendering our bodies for this cause.

Department of State. (2008). Organ donation. Web.

Hubpages. (2010). The importance of organ donation. Web.

MedlinePlus. (2009). Organ donation. Web.

Prange. M. (1998). The importance of organ donation. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, March 11). Importance of Organ Donation. https://ivypanda.com/essays/importance-of-organ-donation/

"Importance of Organ Donation." IvyPanda , 11 Mar. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/importance-of-organ-donation/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Importance of Organ Donation'. 11 March.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Importance of Organ Donation." March 11, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/importance-of-organ-donation/.

1. IvyPanda . "Importance of Organ Donation." March 11, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/importance-of-organ-donation/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Importance of Organ Donation." March 11, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/importance-of-organ-donation/.

- The Ethics of Organ Donation in Modern World

- Organ Donation: Ethical and Legal Considerations

- Blood Donation and Its Advertisement

- The Healthcare System in Nigeria and the Universal Tri-Level of Care

- Policy Evaluation Reform as Related to EHR in Ontario

- Goals of Healthcare Policy and Prevention of Epidemic

- Effects of HIV and AIDS on Young Children and Women

- HIV Counseling and Testing: Lifetime Treatment Program

Organ Donation - Free Essay Samples And Topic Ideas

Organ Donation is the process of surgically removing an organ or tissue from one person (the organ donor) and placing it into another person (the recipient). Essays could explore the ethical, social, and medical aspects of organ donation, including the processes of organ transplantation, the importance of donor registries, and the debates surrounding consent and allocation policies. A substantial compilation of free essay instances related to Organ Donation you can find in Papersowl database. You can use our samples for inspiration to write your own essay, research paper, or just to explore a new topic for yourself.

Mandatory Organ Donation: Ethical or Unethical

The American Transplant Foundation reports that every 12 minutes, there is an additional member who joins 123,000 national organ transplant donors. Even though many people are aware of the advantages that come with organ donation, they may not comprehend all the benefits that come with organ donation, especially to the donor (Santivasi, Strand, Mueller & Beckman, 2017). The subject of organ donation is important because it improves the quality of life for the recipient of the organ transplant. For instance, […]

Should Organ Donation be Mandatory?

Organ donation is the gift of life. By donating organs you are literally saving thousands of adults and children. The number of patients whose organs are failing on a continuous bases. consequently , the more people who are on the list the less likely they are to get an organ which sadly results in their untimely death. But why would you want to see another human being die? Here in the united states, there is a shortage of organs. According […]

Should Organ Donors be Paid for Donations

There seems to be a great debate in this country about whether or not donors should be paid for organ donations. I honestly did not know that this debate was going on before I started doing research on this subject. It seems crazy to think that the state legislator should get involved in the question whether people should be paid for organ donations. I have read a few articles about"the gift of life" and it all sounds ridiculous to me. […]

We will write an essay sample crafted to your needs.

The Benefit of Organ Donation

If there is one thing that everyone in the world can agree on it is the fact that eventually we are all going to die. Death is going to happen to each and every one of us, and the thought of dying is usually very tragic to most people. It is not knowing what is going to happen that can cause the fear of dying in a person or a family. Diseases and tragic accidents are usually the cause for […]

Understanding of Organ Donation

Do we ever think about those patients who lay on bed 24 hours days a week in search of Organ ? There are many simpler ways in which patients can be cured, but it gets very difficult when only one way left which is by donating organ. In simpler words, Organ Donation is the removal process of Organ or tissue from one person through surgical process to be transplanted to another person for the purpose of replacing an Organ injured […]

3D Printing and Bioprinting Revolutionizing Healthcare

3D bioprinting is one of the most anticipating and promising technological advancements of all time. According to the US National Library of Medicine, 3D bioprinting is "a manufacturing method in which objects are made by fusing or depositing materials? such as plastic, metal, ceramics, powders, liquids, or even living cells? in layers to produce a 3D object" (Ventola, 2014, para 2). Is With the capability of using real cells, 3D bioprinting will make it possible to create living tissue. This […]

Why Organ Donation should be Compulsory?

Imagine this: you are diagnosed with severe heart failure and your only chance of survival is to receive a heart transplant. Although your loved ones would desperately like to help, they are unable to. Unlike a set of lungs or a pair of kidneys, you only have one heart, thus making it impossible to consider the idea of utilizing a living donor. You now are faced with the fact that in order to live, you need to rely on an […]

Definition of Organ Donation

Organ donation is defined as the process of transplanting human organs from one person to another ("Organ donation," 2017). As of November 2018, there are more than 114,600 people on the national waiting list for a donor organ, and a new person is added to the list every 10 minutes ("Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network," n.d.). So far in 2018, over 30,400 transplants have been performed from more than 14,500 donors ("Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network," n.d.). The most commonly […]

Reborn to be Alive : Critical Analysis of an Advertisement

“Becoming a donor is probably your only chance to get inside her.” Reborn to be Alive showcases their slogan proudly across their advertisement as a provocative half-naked woman entices the viewer with her gaze. Being an organ donor means being selfless, having compassion, and altruism; yet being an organ donor isn’t enough sufficiency for a good marketing campaign, thus the sexist direction of their advertisement. Reborn to be Alive meant to capture men’s attention by the use of such sexist […]

Role of the Default Bias in Organ Donation Rates

The first law of motion, also known as the law of inertia by Newton goes like this: A body in motion remains in motion or, if at rest, remains at rest at a constant velocity unless acted on by an external force. If one thought inertia was only confined to the walls of physics, behavioral economics asks them to think again. Here I'd like to introduce the reader to the concept of cognitive bias – an organized and consistent pattern […]

Organ Donation Programmes Across the World

Organ Donation Programmes Across the World China Till 2014, Chinese authorities permitted the harvesting of organs from executed prisoners without prior consent from them or their families. In fact, in December 2005, the country’s deputy health minister estimated that as many as 95 per cent of the organs used in China’s transplants came from such sources. Since then, China has banned the practice and is now trying to galvanize organ donations from regular civilians. Iran Iran is the as it […]

Organ Donation not being Accessible for all

Organ Donation: Not Accessible for All "Don't think of organ donation as giving up part of yourself to keep a total stranger alive. It's really a total stranger giving up almost all of themselves to keep part of you alive" (~Author Unknown). Organ donation is the process of surgically removing an organ or tissue from one person (the organ donor) and placing it into another person (the recipient). This is necessary when the recipient's organ has failed or has been […]

Additional Example Essays

- Poor Nutrition and Its Effects on Learning

- The Mental Health Stigma

- Psychiatric Nurse Practitioner

- Substance Abuse and Mental Illnesses

- The Extraordinary Science of Addictive Junk Food

- PTSD in Veterans

- Drunk Driving

- Arguments For and Against Euthanasia

- Effects of Childhood Trauma on Children Development

- Gender Inequality in the Medical Field

- Leadership in Nursing

- Causes of Teenage Pregnancy

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Organ donation in the US is broken, and we know who is to blame

Researchers can identify the weakest link in transplantation, but organ procurement organizations resist change, hannah seo • january 15, 2020.

25,000 additional U.S. lives could be saved yearly by reducing the number of unused organs, one report suggests. [Credit: Pan American Health Organization , flickr | CC]

A clinic on wheels for the homeless, natalie peretsman • february 16, 2009, fecal transplants: the scoop on therapeutic poop, rachel nuwer • november 15, 2011, more bugs, healthier people, joanna klein • december 1, 2014, healing the unborn, jeanette ferrara • february 22, 2016.

While out for a routine jog, Rick collapsed and was rushed to the hospital. He had an undiagnosed genetic heart disease and needed a transplant as soon as possible. He would not receive one for five, long, suspenseful years.

Rick was fortunate — he survived his time on the waiting list — but so many others do not. The United States is facing an organ shortage. According to U.S. Government Information on Organ Donation and Transplantation , an average of 20 people die each day waiting for a transplant, and yet another person is added to the wait list every 10 minutes.

While no one is denying the multifaceted nature of the issue, researchers and clinicians alike point to one obvious weak link: organ procurement organizations. OPOs are the first agents to act when an organ becomes available. They are responsible for encouraging donation by talking to individuals and the families of the recently deceased, and carrying out the surgical procedures for procurement in all eligible cases.

Today, Rick’s son, Greg Segal , is the founder of a non-profit, ORGANIZE , focused on reforming the organ donation system. He sees OPOs and their underperformance as a bottleneck that limits organ availability. “The solution is holding OPOs accountable,” Segal says. Right now, “there’s no pressure on OPOs to figure out how to improve their performance. OPOs are evaluated entirely on self-interpreted and self-reported data, there’s gross under-performance across the OPO industry and huge variability in performance.”

There are 58 OPOs in the United States, each with their own donor service area. Every organ utilized for transplantation in the United States can be traced back to an OPO, says Segal. Unfortunately, these organizations operate as monopolies in their donor service areas, with very little transparency, he adds.

OPOs are resistant to the levels of scrutiny placed on other parts of the organ donation system, like transplant centers and hospitals, says Brianna Doby , an OPO community consultant for Johns Hopkins University. She believes this opacity undoubtedly hinders improvement and change. “There are so many OPOs who claim that they’re doing perfect work,” Doby says, but when you assess wait lists and death rates, that is clearly not the case.

There is currently huge variability in OPO performance and very few consequences for underperformance. According to a report by the Bridgespan Group, a non-profit consulting organization based in Boston, “there are approximately 28,000 additional available organs each year from deceased donors that are not procured or transplanted due to breakdowns of the current system.” The report says that this could equate to about 25,000 additional lives that could be saved yearly.

“Nobody is currently incentivized to optimize organ donations,” says Dorry Segev , a professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins, in an email. OPOs are evaluated by the United Network of Organ Sharing via two metrics: the number of organs they procure from a donor and organs procured per eligible death. These metrics, Segev writes, encourage subpar performance: “With the current regulatory metrics, OPOs may not be incentivized to recover organs from older, sicker, more complex potential donors.”

Segev suspects that some OPOs are prioritizing their organs-procured-per-donor rate, ignoring potential donors where only one organ can be procured, and preventing the possibility of using that one additional organ to save a life. Segev says such a case shows that reforming the metrics used to measure OPO “success” is key to reforming the organ donation system as a whole. Segev is sure that standardizing accountability across organ procurement organizations and eliminating negligent practices will result in tangible, visible, immediate change.

Raymond Lynch , an assistant professor of surgery at Emory University, calculated how many more donors and organs we could expect if lower performing organizations improved their rates of procurement. He found that if the bottom half of OPOs raised their procurement rates to match the average performers, and the top half of OPOs did not change in performance, we could expect 941 extra donors and 2,719 additional organs annually. This relatively conservative change could lead to so many more lives saved. Unfortunately, says Lynch, exact interventions to bring about this change will be hard to implement without complete transparency from OPOs.

Understanding each OPO’s methods and numbers, and standardizing the industry to transparent and objective measures, is crucial, says Lynch. “We need to understand each of the OPO’s processes, even if it does not paint a flattering picture, because only when we have transparency and understanding can we start to formulate appropriate interventions.” She adds that if OPOs did as good a job of improving their performance as they did defending it, we wouldn’t be in this situation.

The Association of Organ Procurement Organization declined to comment for this article, but their website states that “All OPOs are regulated by multiple government agencies and adhere to the highest medical and ethical standards.”

A researcher who requested their name be omitted from this article begs to differ. They say that “stating OPOs are highly regulated is inherently true and inherently meaningless;” since there is no centralized regulatory body, all current regulations are effectively “toothless.” “We’ve allowed ourselves to be told that organ procurement is so complicated that nobody outside the community could understand, let alone regulate it,” they say, “and this mysticism is somehow allowed to justify rampant deregulation.”

In spite of all this, Doby is optimistic that reformation will come. In July, the current administration released an executive order outlining intentions for increased regulations and transparency in OPOs and transplant centers. Nevertheless, she says, an executive order is just a first step — robust policy that standardizes OPO practice at the legislative level needs to be set in place.

Doby hopes that we reach a place where we can insist upon utilizing every organ for transplantation. Hopefully, we will soon see good, enforceable new regulations cross the finish line, she says, because that is what’s going to help patients the most.

About the Author

Hannah Seo is a science journalist based in New York City and the editor-in-chief of Scienceline. She loves writing about the intersections of science, tech and culture. As an ethnically Korean Canadian raised in Qatar, she also considers herself an international nomad.

I am grateful that Mr. Segal received his heart transplant through the generosity of a donor and the work of those of us in the donation field. That’s the kind of success story organ procurement organizations are working hard every day to help achieve. The article correctly states that there are still far too many people in need of life-saving transplants and that more needs to be done. The OPO where I work readily accepts this challenge, as do colleagues across the nation.

However, the article omitted several crucial facts. These facts do not negate the need to do more – we must, and we will – but they provide a more accurate picture of the current situation: Fact: For the seventh straight year, the United States set a new annual record for the number of lives saved through organ donation and transplantation. Fact: A recent study (“Success of Opt-In Organ Donation Policy in the United States,” JAMA, 2019) showed that the United States has the second best organ donation system in the world, behind only Spain, and that many states exceed Spain’s performance. Fact: The number of people on the organ transplant waiting list – although still too high – has been steadily dropping, due to the generosity of donors and the dedication of OPO staff and transplant hospitals. Fact: The proposed rule for the new government performance metric estimates an additional 5,000 to 6,000 organ transplants a year can be achieved by 2026, a far cry from the notion that there are somehow 28,000 “missing” organs. Fact: Organ procurement organizations have every incentive to save as many lives as possible, despite the couched assertions of critics in this article.

OPOs work hard every single day to save as many lives as possible and to honor the generosity of donors and their families. We welcome transparency, we welcome standardized performance metrics and we welcome innovation that can save and improve even more lives.

Thank you for your excellent article on broken OBOs. I am, like you, a nomad living outside the United States with presently no plans to return. What international organization do you know of that would allow me to register my organs for donation anywhere in the world?

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

The Scienceline Newsletter

Sign up for regular updates.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Intensive Care Soc

- v.20(2); 2019 May

Is presumed consent an ethically acceptable way of obtaining organs for transplant?

The near-universal acceptance of cadaveric organ donation has been based on the provision of explicit consent by the donor while alive, either in the form of a formal opt-in or informal discussion of wishes with next of kin. Despite the success of transplantation programmes based on explicit consent, the ongoing imbalance between demand and supply of organs for transplantation has prompted calls for more widespread introduction of laws validating presumed consent with facility for opt-out as a means of increasing organ availability. The Department of Health (UK) has recently concluded a consultation on the introduction of such a law for England. This article explores the debate on presumed consent from an ethical point of view and summarises the key arguments on both sides of the ethical divide.

Introduction

The first successful human organ transplant operation was performed in 1954 and involved the transplantation of a kidney from an identical twin. 1 There has since been a progressive increase in the number and range of transplantation procedures performed successfully, driven by improvements in surgical technique and intensive care and the emergence of medical technologies to bridge organ function in the face of irreversible organ failure and to combat rejection. In the UK as elsewhere, a large proportion of solid (unpaired) organ transplants that are currently performed utilize organs obtained from dead donors. 2

From the outset, there was widespread support for the concept of allogenic organ transplantation from the dead. Even disregarding extreme utilitarian views such as the macabre ‘survival lottery’ hypothesised by John Harris, 3 there is logic in a utilitarian and communitarian view that the dead cannot be harmed by removal of their organs, while the living (and society in general) stand to benefit from them. From a deontological (duty-based) perspective, it can be argued that the right to be a recipient when in need of a transplant imposes corresponding duties to be a donor. 4 The Catholic Church was early to realise the benefits to humanity from transplantation and supported organ salvage from the dead. The violation of the sanctity of the dead was justified by the concept of the ‘Ultimate Gift of Charity’ that a human being could leave his fellows. Integral to this concept was the need for this ‘Gift’ to be properly endowed or ‘given’ by the donor, and not be ‘taken’. 5 This could only be guaranteed by a process of ‘informed consent’ by the donor allowing for the violation of his mortal remains after his death.

The earlier view (and one that still prevails in many jurisdictions) is to insist on the exclusive validity of ‘explicit’ consent, where the donor needs to have ‘opted-in’ to becoming a donor. This needs to have taken place by an act of (usually) signing into a donor register, ideally having had access to adequate information. In the event of untimely death of a potential donor with no explicit evidence of consent or dissent to organ donation, most opt-in jurisdictions accept ‘consent’ to donation being provided by his closest relatives. While there is a general acceptance that only the donor has the right to decide how his ‘private property’ is disposed of after his death, a common-sense approach is taken that his closest relatives are likely to know what his wishes would have been, and are most likely to act accordingly. 6 Allowing relatives to consent prevents a valuable resource from going waste, and importantly, ensures that the potential donor’s wishes are adhered to as closely as possible. Most jurisdictions have tacitly extended the right of veto to close relatives claiming an individual may have changed his mind after opting in, and in some cases, using organs against strong objections by relatives (while legal) may cause distress to those left behind and may adversely impact the doctor–patient relationship and social solidarity on which transplantation systems thrive. 7

In the UK, an opinion poll conducted by the organ donation task force has revealed that 90% of adults are in favour of becoming organ donors. 8 However, as of the last available activity report from the NHS Blood and Transplantation service, only about 36% of eligible adults have registered onto the organ donor register. 2 In the case of adults who die without being on the donor register, refusal rates for organ retrieval by relatives is high, with the consent rate being only 46.7%. The consent rates are high (91.2%) if the potential donor was already on the register or if their wishes are known by the relatives. 2 The numbers of patients on the transplant waiting list has increased by 7% between 2001 and 2013, and the gap between the waiting list size and organ availability is increasing alarmingly. The latest available statistics indicate that in the UK, there are 6388 patients awaiting a transplant as of the end of March 2017, and 457 patients on the waiting list dying while awaiting a transplant. 2 This is the background to the idea that alternative forms of consent such as presumed consent (opt-out) or mandatory choice should be considered as a means of increasing the supply of organs. 9 Other methods of obtaining organs for donation such as ‘organ conscription’ 10 or ‘routine recovery’ 11 and ‘normative consent’ 12 have been mooted, but are largely considered theoretical challenges to the existing pragmatic ethical positions. The risk of extreme policy positions alienating public opinion and reducing donation rates is accepted as being real, and this has prevented any jurisdiction from seriously considering their implementation.

The concept of presumed consent, deemed consent or ‘opt-out’

The concept of presumed consent for organ donation is not new and dates to an idea first mooted by Dukeminier and Sanders. 13 The issue had bubbled over in the field of bioethics with Cohen making the case for it and Veatch and Pitt against. 14 , 15 However, the concept was brought to the fore when Professor Ian Kennedy and his co-authors wrote in the Lancet arguing the case for presumed consent as a way of increasing the supply of urgently needed organs. 16 The BMA’s Medical Ethics Committee endorsed presumed consent for organ donation in the UK calling for a consolidated approach to organ donation for the 21st century. 7 , 17 This resulted in a report by the Organ Donation Taskforce (2008), which suggested that while presumed consent was ethically acceptable, an improved opt-in system or a system of mandated choice may be a better way of ensuring that the wishes of the donor were honoured. 18 The review of existing studies commissioned by the taskforce concluded that while most jurisdictions did clearly have higher donor numbers per million population (pmp) after introduction of opt-out legislation, this could by no means be conclusively attributed to the opt-out legislation in isolation. 19 Opt-out countries such as Spain, Austria and Belgium have among the highest donation rates, but some such as Bulgaria and Luxemburg have among the lowest. 20 The taskforce suggested that significant improvements in organ donation rates could be achieved by improvements in infrastructure and education, including public awareness campaigns. They indicated that the issue of presumed consent should be revisited in five years if the targets were not achieved. 18

By enacting the Human Transplantation (Wales) Act 2013, the Welsh Assembly chose to introduce deemed consent for organ donation into Law from 1 December 2015. 21 The review on which the Welsh Assembly based its decision came to a similar set of findings, but suggested that on balance opt-out legislation was likely to increase donation rates. 22 The version of deemed consent chosen by the Welsh Assembly is termed ‘soft opt-out’, where intention is that the state will not go against refusal by the next of kin. The rationale for this (as against a hard opt-out) is to avoid giving the impression that the state was acting as though it had a ‘right’ to the organs from the deceased, potentially provoking opt-outs from individuals. While early data suggest an increase in consent rates, more registered donors and more live donations, there has been a decrease in actual donor numbers. Admittedly, the small size of the population makes it difficult to draw inferences this early. 23 – 25 The Department of Health (DoH) recently commenced a public consultation on the introduction of an opt-out system of organ donation for England as a means of improving organ donation rates. 26 , 27 This consultation ended on 6 March 2018 and has attracted over 11,000 responses highlighting the passionate views held by the public on this topic.

Ethical arguments relating to the presumption of consent

The following discussion looks at the ethical arguments against and for an opt-out arrangement. It is not meant to add to the two excellent reviews and a critique that have looked into the issue of whether introduction of presumed consent will increase the supply of organs in England and Wales. 19 , 20 , 22 An attempt will be made to draw some conclusions that bridge the chasm in normative ethics about the use of presumed consent strategies.

The argument against presumption of consent

One of the key arguments made against the presumption of consent is the concern that informed consent would no longer be involved in the process of organ acquisition. This means that the organ is no longer a gift or donation in the true sense of the word. It appears as something that has been ‘taken’ from the dead. In Pope Benedict XVI’s words, “… In these cases, informed consent is a precondition of freedom so that the transplant can be characterised as being a gift and not interpreted as a coercive or abusive act”. 28 On this basis, Austriaco has urged that all catholic individuals and institutions “… must reject presumed consent and not cooperate with an unjust system of organ procurement.” 29 There is evidence that majority of recipients wish to be certain that the organs were only retrieved in accordance with the donor’s wishes. 30 This concern (among other practical considerations) was one of the factors that made the Organ Donation Taskforce argue against the introduction of presumed consent. 18

The problem is that this assumes the opting-in process to entail ‘informed consent’. With behavioural economic theories (nudge theories) being applied extensively in the public policy sphere, the process of opting into a donor register involves nothing more than a tick in a box during an application for a driving licence or renewing a vehicle excise duty. 31 At the time the application is made, the implications of the tick box are likely far from the applicant’s mind. Similar ‘nudge theories’ are thought to lie behind the use of presumed consent in organ donor registration policy. There is clear acceptance in the domain of behavioural economics that when presented with alternatives, people who are unsure tend towards the default (status quo bias or default bias). 32 This is thought to be one of the reasons behind higher donation rates in presumed consent jurisdictions.

The fact remains that most potential donors in the UK are not on the donor register, and current practice in explicit consent jurisdictions entails asking relatives to ‘consent’ on their behalf. This consent has no real validity in terms of ensuring the gifted nature of the donation process. Besides, it puts an additional strain on the relatives in a situation that is already excruciating. The relatives are being asked to rule against the ‘presumption’ that the donor would not have wished to donate (which is the presumption in explicit consent jurisdictions), and consent to what they might consider as the mutilation of the deceased’s mortal remains. It is therefore not surprising that consent rates for organ retrieval are low when the wishes of the potential donor are not known. There is also the argument that of the 90% of individuals who stated in surveys that they would wish to donate, the 54% who did not register presumably failed to do so primarily due to apathy, and not because they would not want to donate. 8 It could also be argued that the claims made when surveyed may reflect their values, but may not reflect their wishes, hence the disparity between survey results and donor registration rates.

The main argument against presumed consent stems from the potential for violation of the donor’s autonomy: his wish about what should happen to his body after death. Farsides states that “acknowledging and where possible acting in accordance with a person’s wishes regarding treatment of their body signals respect for that autonomy”. 33 The moral wrong involved in interfering with a dead person’s body against his (un)stated wish maybe seen as worse than the moral wrong involved in non-interference with the body against his (un)stated wish. Veatch and Pitt argue that the two wrongs are not morally equal, analogous to the commonly accepted view that it is better to let nine guilty individuals be unjustly freed than for one innocent to be punished. 15 They state that unless it is unequivocally clarified that the overwhelming majority of individuals would want to donate their organs upon their deaths, the only morally correct solution would be to adhere to an explicit consent policy. This is because removal of organs without explicit consent constitutes a blatant violation of bodily integrity (and thence autonomy), whereas failure to remove organs when it may have been desired, is ‘merely’ an unfortunate failure to help bring about a desired outcome.

A further point of objection to presumed consent policies raised by Veatch and Pitt is the view that such policies are actually a misnomer, as no one can presume consent when the person who owns the property is unable to provide such consent explicitly. They state that such policies are attempting to give ‘eminent domain’ policies (that basically state that private property is for the state to use to satisfy a public Good) a cloak of respectability to make them acceptable to a society that values the rights of the individual above everything else. 15

Ben Saunders, a prominent supporter of the opt-out policy for organ donation agrees that the presumption of consent is a misnomer, as consent as we know it involves an active process with its three well known components (capacity, adequate information and ability to balance the information to come to a decision). He argues that ‘an opt-out policy without presumptions’ is ethical, as the failure to register an objection (given adequate chances to do so) can be ‘interpreted’ as implied consent. 34 MacKay counters this with the evidence that across Europe, surveys have shown poor understanding of existing donor registration policies. 35 In the backdrop of this, the assumption that silence means tacit consent would not be ethical. 36

One of the fears raised by the Organ Donor Task Force was the risk of increased opt-outs as a push back against what could be considered interference by the state. In fact, the Welsh experience has shown that about 5% of the eligible population did opt out in the three years since the legislation came into force. 37

The argument for presumption of consent

On the other side, Cohen 14 argues that a presumption is made in either case: either a presumption that majority of individuals do not wish to be donors or to the contrary. 14 In each case, a proportion will be wronged by having their autonomous will violated. He argues that violation of the autonomous will of a dead person is equally wrong: whether it involves a mistaken removal or a mistaken non-removal. The interference with the body is not the moral wrong, but the violation of autonomy. He states that “the present system, depending entirely on the expressed consent of the decedent’s family after death, thus errs in its empirical underpinning, and by that error promotes a great moral mistake”. 14 In this sense, even if 51% of individuals are potential donors, fewer mistakes would be committed with a presumed consent policy. This supports the ‘fewer mistakes’ claim in favour of a presumed consent system of organ donation, assuming that the mistakes are morally equal.

A system of explicit consent (opt-in) with a low uptake that relies on consent from the next of kin may leave an objector open to potential violation, as their relatives may not be aware of their objection and may have values different from the donor. In such a situation, proponents of presumed consent with opt-out argue that the provision of opt-out provides objectors with a clear path to maintain their autonomy. 7

There is also the logical assumption that an individual opposed to organ donation is more likely to opt-out under a system of presumed consent, than someone who desires to donate is to opt-in under an explicit consent system. This assumption stems from the fact that “most of those opposed to organ donation have conspicuous religious or moral objections of which they themselves are very aware, and as a result are unlikely to neglect to opt-out of a system of presumed consent”. 38 In stark contrast, those who wish to donate are doing so out of an altruistic motive, which is “relatively unremarkable”, and are less likely to make their preferences clear before the unexpected eventuality of their death occurs. 38 However, in a stinging counter to this, Kluge argues that presumed consent policies with opt-out protection are akin to a person who does not wish to be violated having to inform trespassers of this fact and is a ‘reversal of polarity of the right to inviolability’. 39

Spital and Taylor make a case for “entirely eliminating the consent requirement for the routine recovery of transplantable cadaveric organs”. 11 They equate this to a situation of total war in which most citizens would accept the concept of a draft in the general public interest. They claim additional benefits to routine removal such as equity, avoidance of additional stress on grieving relatives and removal of potential for exploitation as reasons why this process is more ethical than explicit consent. The issue seems to boil down to whether organ retrieval (or routine salvage as Dukeminier & Sanders referred to it) is actually a ‘give’ by the donor or a ‘take’ by the state.

Gill gives this argument a completely novel dimension by defining the two types of autonomy being referred to implicitly in these two widely varying points of view. He argues this difference in the forms of autonomy being referred to as being a crucial aspect in rationalising the two arguments. 38

To understand this better, it would help to use the relatively simple analogy of disposal of one’s assets. When an individual is alive, he has every right to do what he wants with his assets, and any interference with his wishes goes contrary to his autonomous will. If he dies with a will in place, his autonomous will is clearly stated, and his assets are distributed as he would have wished. This is referred to as the ‘non-interference model’ of autonomy. The two proponents do not differ in their approach to this model of autonomy. If an individual is alive and competent, an invasive procedure will only be performed with his explicit consent. Similarly, if his desires regarding organ donation are clear, the same model would apply.

The divergence happens if this individual dies intestate, or without leaving clear instructions as to his wishes regarding organ donation. The non-interference model is no longer applicable, as the state cannot leave his assets be as they are when he died. Nor can the state leave his body as it is when he dies. ‘Interference’ in some shape or form is mandatory, and the state uses a ‘respect for wishes model’ of autonomy to decide how best to interfere in these scenarios. In the case of his assets, the state takes the view (presumes) that most people would want their assets distributed among their closest relatives and acts accordingly. In so doing, it is likely that in a few cases mistakes will be made: for example, if he wanted all his assets left to charity. From a policy perspective, it makes sense to implement one that makes the fewer mistakes. Gill is categorical in his dismissal of Veatch and Pitt, and Kluge’s claim that mistaken removals violate an individual’s right to non-interference with their bodies, as these individuals when brain-dead, are no longer capable of self-determination. 15 , 39

Gill argues that the same should apply to organ donation after death: “The duty to respect persons’ wishes about what should happen to their bodies after death implies that we should follow the policy that can reasonably be expected to lead to the fewest mistakes”. If the available evidence is right, and points to a majority wishing to donate their organs after death, an organ procurement policy that presumes consent will overall make fewer mistakes than one that insists on explicit consent. In fact, he argues that a society which institutes a presumed consent policy is “a society that does its best to construct policy that respects individuals’ own choices” and not one that fails to adhere to the Nuremberg Code. 40 Mackay counters this argument by clarifying the implications of donor registration policies. Their remit is all about registering currently competent people for an intervention that will occur when they are no longer competent. In this context, autonomy will be only respected if they are asked for authorisation while they are competent rather than use a respect for wishes model when incompetent. He says that consent may not be a necessary step in organ retrieval (if society so decides), but to be respectful of autonomy, a donor registration policy should do everything possible to seek consent (opt-in). 36

What is clear from the arguments presented is that an individual society’s chances of making ‘fewer mistakes’ in preserving autonomy of the donor revolves around knowing for certain what the overwhelming majority of its members would want happen to their bodies after death.

Opponents of presumed consent policies argue that only if the desire to donate applies to the “overwhelming majority” could a presumed consent policy be considered morally acceptable. The proponents argue that if a simple majority emphatically desire to be donors, a presumed consent policy will be justified over an explicit consent policy. Neither disagree that from a communitarian perspective, organ donation is a moral good, and should be encouraged. Both accept that information on the process is the key to ensuring the ethical validity of either approach.

It seems incumbent upon society to ensure that this message gets across to everyone by making information on the benefits of organ donation available in a language that is simple and clear. This would eventually overcome the apathy that seemingly prevents the silent majority from signing on to the organ donor register, and thereby render the whole process almost self-fulfilling. Such a paradigm shift will also not ignore the needs of those who, for whatever reason or no reason at all, are opposed to becoming organ donors. They should be able to make their opposition clear without fear of recrimination, and with the utmost certainty that society will uphold their wishes. This seems to have been the approach taken by the organ donation task force in its report titled “The potential impact of an opt out system for organ donation in the UK: An independent report from the Organ Donation Taskforce”. The taskforce concluded that as things stand, “a presumed consent system has the potential to undermine the concept of donation as a gift, to erode trust in health professionals and the Government, and negatively impact organ donation numbers”.

A presumption of consent is also ethically sound and morally justified in organ retrieval for transplantation, provided information on the opt-out process is readily available in easily comprehensible formats, it is ensured that as many people as possible understand the opt-out process and families are given a say in the final decision. However, the concerns that surround the implementation of such a policy are real and mandate that implementation be preceded by a public information campaign highlighting the moral justification for organ donation as a whole, changes in infrastructure that separate the clinicians involved in the clinical care of potential donors from the staff involved in the diagnosis of brain death, consent process, organ retrieval and organ transplantation and clarification of the legal standing of organ donor cards.

Until this happens in practice, policies that presume non-consent and those that presume consent will continue to make mistakes in individual cases. Society will have to decide whether a moral mistake that saves other lives (mistaken removals in presumed consent policy) is in any way preferable to an equivalent moral mistake that in addition costs lives (mistaken non-removals in a policy of explicit consent). It would be hoped that in a future where organ donation is ‘the norm’, history will not harshly judge us as a society that left its sick to suffer through a desire not to harm the potential autonomous will of its dead.

Acknowledgements

This paper is largely drawn from an essay written by the author as part of the requirements for the ‘end of life’ module of a Master’s degree in Bioethics and Medical Law at St Mary’s University, Twickenham. The author gratefully acknowledges the comments from Dr Pia Matthews, the module director, as part of the evaluation of the essay. The author is also grateful for the suggestions and comments from the MA programme Director, Dr Trevor Stammers that have substantially contributed to the final shape of the paper. The paper has undergone substantial modification based on the suggestions of the original reviewers from the JICS editorial board.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

- Open access

- Published: 13 May 2024

Organ donation after extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a nationwide retrospective cohort study

- Tetsuya Yumoto 1 ,

- Kohei Tsukahara 1 ,

- Takafumi Obara 1 ,

- Takashi Hongo 1 ,

- Tsuyoshi Nojima 1 ,

- Hiromichi Naito 1 &

- Atsunori Nakao 1

Critical Care volume 28 , Article number: 160 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

454 Accesses

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Limited data are available on organ donation practices and recipient outcomes, particularly when comparing donors who experienced cardiac arrest and received extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) followed by veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) decannulation, versus those who experienced cardiac arrest without receiving ECPR. This study aims to explore organ donation practices and outcomes post-ECPR to enhance our understanding of the donation potential after cardiac arrest.

We conducted a nationwide retrospective cohort study using data from the Japan Organ Transplant Network database, covering all deceased organ donors between July 17, 2010, and August 31, 2022. We included donors who experienced at least one episode of cardiac arrest. During the study period, patients undergoing ECMO treatment were not eligible for a legal diagnosis of brain death. We compared the timeframes associated with each donor’s management and the long-term graft outcomes of recipients between ECPR and non-ECPR groups.

Among 370 brain death donors with an episode of cardiac arrest, 26 (7.0%) received ECPR and 344 (93.0%) did not; the majority were due to out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. The median duration of veno-arterial ECMO support after ECPR was 3 days. Patients in the ECPR group had significantly longer intervals from admission to organ procurement compared to those not receiving ECPR (13 vs. 9 days, P = 0.005). Lung graft survival rates were significantly lower in the ECPR group (log-rank test P = 0.009), with no significant differences in other organ graft survival rates. Of 160 circulatory death donors with an episode of cardiac arrest, 27 (16.9%) received ECPR and 133 (83.1%) did not. Time intervals from admission to organ procurement following circulatory death and graft survival showed no significant differences between ECPR and non-ECPR groups. The number of organs donated was similar between the ECPR and non-ECPR groups, regardless of brain or circulatory death.

Conclusions

This nationwide study reveals that lung graft survival was lower in recipients from ECPR-treated donors, highlighting the need for targeted research and protocol adjustments in post-ECPR organ donation.

A worldwide crisis in organ shortage is intensifying as the need for transplantations spikes; however, the supply of available organs falls short of meeting this escalating demand, further widening the gap between those in need and the organs available [ 1 ]. In response, the significance of comprehensive screening for brain death in the intensive care unit (ICU), particularly following cardiac arrest, to identify potential organ donors has been increasingly emphasized [ 2 , 3 ].

Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) has been increasingly employed as an emerging rescue treatment strategy [ 4 , 5 ]. However, the implementation of ECPR introduces complex ethical challenges, primarily because it frequently results in patients being placed on mechanical support with minimal prospects of neurological recovery [ 6 ]. Previous research has indicated that patients resuscitated with ECPR exhibit a markedly higher rate of brain death compared to those who undergo conventional CPR [ 2 ]. Indeed, a large retrospective study of ECPR in Japan, a leading country in the field of ECPR, revealed that decisions to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining therapy were most frequently made on the first day, with a median decision time of 2 days following admission to the ICU. Importantly, the perceived unfavorable neurological prognosis was the primary reason for the withhold or withdraw life-sustaining therapy decision [ 7 ]. In Japan, the legal diagnosis of brain death while on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was not allowed until recent guideline amendments [ 8 ]. Further, the actual practice patterns and prevalence of organ donation following ECMO discontinuation have not been thoroughly investigated. A registry study from Europe suggests that organ donation rates are higher in patients undergoing ECPR than those receiving conventional CPR, indicating a potential for increasing organ donations through ECPR [ 9 , 10 ].

This situation highlights the need for a comprehensive investigation into the practices of organ donation following ECPR, encompassing donor characteristics and the impact on recipients. To date, there has been a lack of research focused on the outcomes for recipients of organs from donors who have undergone ECPR, as well as those who have not. This study aims to fill this gap by examining the current practices and outcomes of organ donation post-ECPR, thereby enhancing our understanding of the potential for organ donation following cardiac arrest.

Study design and ethics

This was a nationwide retrospective cohort study in Japan using the Japan Organ Transplant Network database, covering the entire cohort of deceased organ donors of any ages, from July 17, 2010 through August 31, 2022. The Japan Organ Transplant Network prospectively collects data, including basic patient information and the clinical course details. These are recorded in a paper-based format by a transplant coordinator, based upon the patient’s medical records. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Japan Organ Transplant Network (Approved Number: 15) and the Ethics Committee of Okayama University Hospital (Approved Number: K2303-030). Informed consent from the patient's family or legal representative was waived in this study.

Organ donation policy in Japan

The history and details of organ donation policy and the surrounding system are elaborated on elsewhere [ 11 , 12 ]. To summarize, Japan's organ donation policy after brain death underwent significant revision with the implementation of the revised Organ Transplant Law on July 17, 2010. This revision introduced two major changes: firstly, it established a system permitting organ donation with only the family's consent when the preferences of the deceased are unknown; and secondly, it authorized the transplantation of organs from children under 15 years of age. Prior to these changes, organ donation after brain death was permitted only if the patient had formally documented their wish to donate their organs. As a direct consequence of these policy revisions, the number of organ transplants from brain-dead donors saw a substantial increase, from 86 cases recorded between 1997 and 2010 to 413 cases between 2010 and 2017. In Japan, the donor's family has the right to choose which organs can be procured for recipients.

Protocol for organ donation following brain death

The timing of presenting organ donation as a potential end-of-life care option is entirely at the discretion of the attending physician or according to hospital policy. Per the Japan Organ Transplant Network procedures, this option is typically presented after the clinical confirmation of brain death. However, if a patient is considered a potential organ donor due to devastating brain damage, the presentation of this option can proceed before the confirmation of brain death. Upon family consent, the process requires two distinct legal confirmations of brain death, conducted at least 6 h apart (or 24 h for children under 6 years old), through comprehensive neurological tests, an apnea test, and electroencephalography, leading to the eventual retrieval of organs. Previously, during the study period, individuals undergoing ECMO treatment were not eligible for a legal diagnosis of brain death until the guidelines were updated on January 1, 2024. Therefore, during our study, brain death could only be diagnosed post-decannulation of veno-arterial (VA) ECMO, when possible. In Japan, the transfer of potential organ donors between hospitals for the purpose of donation is prohibited.

Protocol for organ donation following circulatory death

In Japan, controlled donation after circulatory death programs, particularly those using VA ECMO perfusion for organ preservation, have not been widely introduced [ 13 ]. Consequently, only kidneys and pancreases are typically donated after circulatory death under the scenario of unexpected circulatory demise. Accordingly, all donors after circulatory death have been categorized as IIb or VI, in accordance with the modified Maastricht classification [ 14 ]. The placement of a catheter for organ perfusion and the administration of heparin are permitted only after a diagnosis of brain death has been confirmed and the donor's family has consented to preoperative procedures. This allows for the placement of a catheter before cardiac arrest and the administration of heparin.

Study population and data extraction

The data source for this study was the Japan Organ Transplant Network database. We included all deceased organ donors from whom at least one organ was recovered and subsequently transplanted. From this cohort, we specifically selected those individuals who had experienced at least one episode of cardiac arrest either before or after hospital arrival were selected. This selection was based on the free text comments that summarized the clinical course from admission to the legal determination of brain death. We received the anonymized data as follows: whether the donation was after brain death or circulatory death, age, sex, primary disease or injury, the modified Maastricht classification for donation after circulatory death (either IIb or VI as mentioned above), time intervals from admission to brain death confirmation, presentation of the option for organ donation, legal determination of brain death, organ procurement, the number of organs donated, and, if applicable, the duration of VA ECMO use in patients who received ECPR. The matched data from donors and recipients, provided by the Japan Organ Transplant Network using identifiable numbers, were used to observe graft survival rates over the longest follow-up period.

The primary outcome was timeframe for the organ donation process, spanning from admission to organ procurement. Secondary outcomes included the number of organs donated and their graft survival rates.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were expressed as medians with interquartile range (IQR), and categorical data as counts and percentages. Patients were stratified based on whether they underwent ECPR and the type of donation (either after brain death or circulatory death) for comparative analyses. Comparisons between the two groups employed the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test for categorical variables. Graft survival curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method and were compared with the log-rank test. Graft survival is defined as the graft still functioning and not having been rejected by the recipient's body at a specified time post-transplantation. This excludes cases where the patient has been relisted for transplantation. Specifically for kidney transplants, graft survival also includes the period until the patient becomes dependent on dialysis again. Donor and recipient characteristics were not matched between groups. In an exploratory analysis, as ECMO technology and management have developed over last years, graft survival rates except for small intestine were compared between the periods from 2010 to 2017 and 2018 to 2022. Missing data were removed during the analysis whenever comparisons were made. All tests were two-tailed, and a P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using Prism 10.0.3 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) and IBM SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL).

During the study period, there were 370 donors after brain death with an episode of cardiac arrest, of which 26 (7.0%) patients received ECPR and 344 (93.0%) did not receive ECPR. Additionally, there were 160 donors after circulatory death, among whom 27 (16.9%) patients received ECPR and 133 (83.1%) did not.

Donation after brain death

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of donors after brain death with an episode of cardiac arrest, revealing similar basic demographics between groups. However, the majority of cases in the ECPR group were of cardiac origin. The median duration of VA ECMO support in the ECPR group was 3 days (IQR, 1 to 4). Compared to those not receiving ECPR, patients in the ECPR group experienced significantly longer intervals from admission to the presentation of the organ donation option to their families (5 vs. 3 days, P = 0.012), to the clinical confirmation of brain death (9 vs. 5 days, P = 0.001), and to organ procurement (13 vs. 9 days, P = 0.005).

Table 2 presents the number and distribution of organs donated, comparing the ECPR and non-ECPR groups. The median number of organs donated was similar between the groups (5 vs. 5, P = 0.294). The proportion of heart donations was significantly lower in the ECPR group compared to the non-ECPR group (50% vs. 80%, P < 0.001). However, the donation rates for other organs were comparable between the two groups.

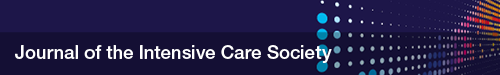

Figure 1 illustrates the graft survival curves for each organ. The lung graft survival rates were significantly lower in the ECPR group compared to the non-ECPR group (log-rank test P = 0.009). Graft survival rates for both unilateral (single) and bilateral (double) lung grafts among recipients from brain-dead organ donors were generally lower in the ECPR group. This reduction was statistically significant for unilateral lung grafts, as detailed in Additional file 1 . No significant differences were observed in the graft survival rates of other organs.

The Kaplan–Meier curve of graft survival for each organ among recipients from brain-dead organ donors, comparing those who had received ECPR with those who had not. The P values obtained from the log-rank test for heart, lung, liver, pancreas, kidney, and small intestine were 0.072, 0.009, 0.950, 0.902, 0.577, and 0.519, respectively. The median observation periods for grafts from donors who experienced cardiac arrest and received ECPR versus those from non-ECPR donors, respectively, were as follows: for heart grafts, 1203 days (IQR: 542 to 2278) and 1690 days (IQR: 908 to 2610); for lung grafts, 777 days (IQR: 573 to 1816) and 1323 days (IQR: 596 to 2211); for liver grafts, 1816 days (IQR: 671 to 2438) and 1551 days (IQR: 738 to 2466); for pancreas grafts, 1083 days (IQR: 442 to 2118) and 1708 days (IQR: 677 to 2673); for kidney grafts from brain-dead donors, 1787 days (IQR: 736 to 2429) and 1690 days (IQR: 987 to 2576); and for small intestine grafts, 2446 days (IQR: 2446 to 2446) and 703 days (IQR: 404 to 1217); ECPR: extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Donation after circulatory death

Table 3 outlines the demographic and clinical characteristics of donors post-circulatory death, highlighting a higher prevalence of male donors in the ECPR group compared to the non-ECPR group. Regarding the primary disease or injury, cardiac diseases were notably more common among ECPR patients, mirroring the trend observed in brain-dead organ donors. The reporting of the duration of VA ECMO support was limited by extensive missing data. Additionally, the intervals from admission to offering the option of organ donation to the family and proceeding to organ procurement showed no significant differences between the two groups.

Table 4 reports the number and distribution of organs donated, comparing the ECPR and non-ECPR groups. The pancreas was not donated in either group. High kidney donation rates were noted in both groups. Left kidney donation was lower in the ECPR group compared to non-ECPR group (85 vs. 96%, P = 0.023).

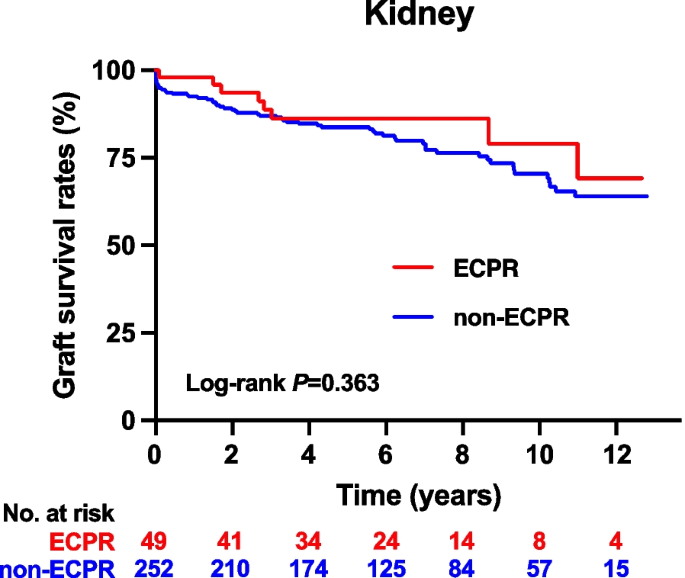

Figure 2 shows the graft survival curve for kidneys, indicating no significant differences between the ECPR and non-ECPR groups.

The Kaplan–Meier curve of graft survival for kidney among recipients from circulatory-dead organ donors, comparing those who had received ECPR with those who had not. The P values obtained from the log-rank test were 0.363. The median observation periods for grafts from donors who experienced cardiac arrest and received ECPR versus those from non-ECPR donors were 2071 days (IQR: 1004 to 3110) and 2160 days (IQR: 1175 to 3535), respectively. ECPR: extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Exploratory analysis

Lung graft survival rates for ECPR patients from the periods 2010–2017 and 2018–2022 showed no significant difference, as indicated in Additional file 2 (log-rank test P = 0.827). Similarly, liver graft survival rates for the same periods did not differ significantly within the ECPR group; however, liver graft survival rates from ECPR patients were significantly lower compared to those from non-ECPR patients in 2018–2022 (log-rank test P = 0.023). Comparable patterns were observed in graft survival for other organs.

In this nationwide cohort study conducted in Japan, we found that time intervals from admission to organ procurement after brain death were significantly longer for ECPR patients compared to non-ECPR patients. However, these intervals were similar following circulatory death. The number of organs donated after either brain death or circulatory death was comparable between the ECPR and non-ECPR groups. Despite similar proportions of lung donations between groups, lung graft survival was significantly lower in recipients from brain-dead organ donors who received ECPR compared to those without ECPR.

Our findings indicate that the time from admission to organ procurement in Japan is longer than that reported in other countries [ 15 , 16 ]. This variation may be attributed to the extensive discussions required around end-of-life care options, including organ donation, which are further complicated by the cultural emphasis on family involvement in medical decision-making processes [ 17 ]. Moreover, we noted that donors who underwent ECPR experienced longer delays to organ procurement compared to those who did not receive ECPR. This delay is likely due to legal constraints preventing the determination of brain death until after the decannulation of VA ECMO, highlighting a unique challenge in the organ donation process in Japan. Notably, guidelines were updated on January 1, 2024, allowing the diagnosis of brain death while on ECMO.

The influence of a donor’s ICU stay duration on recipient outcomes remains underexplored. A study from Germany indicated that the ICU stay duration of donors did not significantly impact the survival rates or outcomes following heart transplantation [ 18 ]. Similarly, another study concluded that the duration of a donor's ICU stay had no significant effect on patient and graft survival rates after pediatric liver transplantation [ 19 ]. These insights suggest that the ICU stay duration may not critically affect transplantation outcomes, consistent with our observations, with the possible exception of lung transplants. Meanwhile, there is limited data on donors who are brain dead with ongoing ECMO support. Among the available studies, the largest, conducted in France, focused predominantly on donors who received VA ECMO. It revealed that kidneys procured and transplanted from these donors did not exhibit differences in survival and functional outcomes compared to those from donors who were brain dead without ECMO support [ 20 ].

ECPR is typically administered to patients with a potential or presumed cardiac origin [ 4 , 5 ]. Consequently, even after the successful decannulation of VA ECMO, we observed a significantly lower rate of heart donations in the ECPR group compared to the non-ECPR group. Meanwhile, despite similar lung donation rates between groups, lung graft survival was significantly lower in ECPR recipients from brain-dead donors than in those without ECPR. This trend was consistent across both time periods, from 2010 to 2017 and from 2018 to 2022. This phenomenon may be attributable to “ECMO lung”, a condition characterized by lung injury induced by VA ECMO, resulting from inflammatory injury or pulmonary congestion [ 21 ]. Meanwhile, we observed that liver graft survival rates from ECPR patients were significantly lower compared to those from non-ECPR patients in 2018–2022. Although we could not fully explain the reasons, this might be partly due to severe cardiovascular condition affecting liver function through mechanisms such as cardiac hepatopathy, which includes impaired arterial perfusion and passive congestion from elevated venous pressure, often exacerbated by the hemodynamic instability and changes in liver perfusion associated with ECMO support [ 22 ].

According to the study using Japanese Diagnosis Procedure Combination Database, the prevalence of ECPR for OHCA from July 2010 to March 2017 was 2.6% (5612/212,295) [ 23 ]. Over the past 12 years, despite the lack of legal permission of brain death diagnosis during ECMO support, our study identified 53 deceased organ donors who had undergone VA ECMO due to at least one episode of cardiac arrest, with the vast majority experiencing OHCA. The exact number of brain death cases among patients who received ECPR for OHCA in the prior study is unknown; however, considering a meta-analysis indicating a 27.9% prevalence of brain death following ECPR [ 6 ], it can be speculated that the majority may have died without the opportunity for organ donation.

This study has several limitations. First, regarding donor characteristics, the study did not capture donors' comorbidities, the detailed processes involved in organ donation, or outcomes focused on the donors' families. Second, the analysis was limited by the absence of specific data, particularly the duration of VA ECMO support. These missing data restricted our ability to analyze and adjust graft survival outcomes in relation to the duration of ECMO support. Third, from the perspective of recipients, essential characteristics, including factors known to influence graft survival such as human leukocyte antigen mismatches and primary or underlying diseases, were unavailable. As a result, these variables were not adjusted for in our analysis [ 24 , 25 , 26 ]. Lastly, detailed recipient data was not available, and the small sample size precluded matching between groups, further constraining our analysis.

Despite these limitations, our research provides crucial insights into the patterns of organ donation and long-term graft survival after ECPR, based on extensive nationwide data. Although diagnosing brain death while on ECMO is now permitted in Japan, scenarios in which brain death is diagnosed after successful decannulation of ECMO are expected to increase as the use of ECPR as a strategy for OHCA expands worldwide. While the primary goal of ECPR should not be organ donation, our findings underline the necessity for additional research to develop thorough guidelines for end-of-life care and the organ donation process in such scenarios. Additionally, our study suggests that lung transplantation from donors who underwent ECPR may result in worse graft survival compared to those who did not receive ECPR. This aspect, as well as the impact on other organs, warrants further investigation in future research.

In this nationwide study from Japan, we discovered that lung graft survival was lower in recipients from ECPR-treated donors. These results emphasize the influence of ECPR on organ donation and underscore the need for further research to refine end-of-life care and organ donation protocols, particularly concerning lung graft survival and its effects on other organs following ECPR.

Availability of data and materials

Data not available due to ethical restrictions.

Abbreviations

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Interquartile range

- Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

Veno-arterial

Lewis A, Koukoura A, Tsianos GI, Gargavanis AA, Nielsen AA, Vassiliadis E. Organ donation in the US and Europe: the supply vs demand imbalance. Transpl Rev. 2021;35(2):100585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trre.2020.100585 .

Article Google Scholar

Sandroni C, D’Arrigo S, Callaway CW, et al. The rate of brain death and organ donation in patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(11):1661–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-016-4549-3 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Morrison LJ, Sandroni C, Grunau B, et al. Organ donation after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a scientific statement from the international liaison committee on resuscitation. Circulation. 2023;148(10):E120–46. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001125 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Inoue A, Hifumi T, Sakamoto T, Kuroda Y. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in adult patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(7):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.015291 .

Inoue A, Hifumi T, Sakamoto T, et al. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adult patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a retrospective large cohort multicenter study in Japan. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-03998-y .

Abrams D, MacLaren G, Lorusso R, et al. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adults: evidence and implications. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-021-06514-y .

Naito H, Sakuraya M, Hongo T, Takada H, Yumoto T, Yorifuji T. Prevalence , reasons , and timing of decisions to withhold / withdraw life-sustaining therapy for out - of - hospital cardiac arrest patients with extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care . 2023:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-023-04534-2

Regarding the partial revision of the guidelines for the Organ Transplantation Law. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/hourei/doc/tsuchi/T231213H0020.pdf . Accessed on 19 Feb 2024.