Intellectual Property Law Research Paper Topics

Welcome to the realm of intellectual property law research paper topics , where we aim to guide law students on their academic journey by providing a comprehensive list of 10 captivating and relevant topics in each of the 10 categories. In this section, we will explore the dynamic field of intellectual property law, encompassing copyrights, trademarks, patents, and more, and shed light on its significance, complexities, and the diverse array of research paper topics it offers. With expert tips on topic selection, guidance on crafting an impactful research paper, and access to iResearchNet’s custom writing services, students can empower their pursuit of excellence in the domain of intellectual property law.

100 Intellectual Property Law Research Paper Topics

Intellectual property law is a dynamic and multifaceted field that intersects with various sectors, including technology, arts, business, and innovation. Research papers in this domain allow students to explore the intricate legal framework that governs the creation, protection, and enforcement of intellectual property rights. To aid aspiring legal scholars in their academic pursuits, this section presents a comprehensive list of intellectual property law research paper topics, categorized to encompass a wide range of subjects.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

- Fair Use Doctrine: Balancing Creativity and Access to Knowledge

- Copyright Infringement in the Digital Age: Challenges and Solutions

- The Role of Copyright Law in Protecting Creative Works of Art

- The Intersection of Copyright and AI: Legal Implications and Challenges

- Copyright and Digital Education: Analyzing the Impact of Distance Learning

- Copyright and Social Media: Addressing Infringement and User Rights

- Copyright Exceptions for Libraries and Educational Institutions

- Copyright Law and Virtual Reality: Emerging Legal Issues

- Copyright and Artificial Intelligence in Music Creation

- Copyright Termination Rights and Authors’ Works Reversion

- Patentable Subject Matter: Examining the Boundaries of Patent Protection

- Patent Trolls and Innovation: Evaluating the Impact on Technological Advancement

- Biotechnology Patents: Ethical Considerations and Policy Implications

- Patent Wars in the Pharmaceutical Industry: Balancing Access to Medicine and Innovation

- Standard Essential Patents: Analyzing the Role in Technology Development and Market Competition

- Patent Thickets and the Challenges for Startups and Small Businesses

- Patent Pooling and Collaborative Innovation: Advantages and Legal Considerations

- Patent Litigation and Forum Shopping: Analysis of Jurisdictional Issues

- Patent Law and Artificial Intelligence: Implications for Inventorship and Ownership

- Patent Exhaustion and International Trade: Legal Complexities in Global Markets

- Trademark Dilution: Protecting the Distinctiveness of Brands in a Global Market

- Trademark Infringement and the Online Environment: Challenges and Legal Remedies

- The Intersection of Trademark Law and Freedom of Speech: Striking a Balance

- Non-Traditional Trademarks: Legal Issues Surrounding Sound, Color, and Shape Marks

- Trademark Licensing: Key Considerations for Brand Owners and Licensees

- Trademark Protection for Geographical Indications: Preserving Cultural Heritage

- Trademark Opposition and Cancellation Proceedings: Strategies and Legal Considerations

- Trademark Law and Counterfeiting: Global Enforcement Challenges

- Trademark and Domain Name Disputes: UDRP and Legal Strategies

- Trademark Law and Social Media Influencers: Disclosure and Endorsement Guidelines

- Trade Secrets vs. Patents: Choosing the Right Intellectual Property Protection

- Trade Secret Misappropriation: Legal Protections and Remedies for Businesses

- Protecting Trade Secrets in the Digital Age: Cybersecurity Challenges and Best Practices

- International Trade Secret Protection: Harmonization and Enforcement Challenges

- Whistleblowing and Trade Secrets: Balancing Public Interest and Corporate Secrets

- Trade Secret Licensing and Technology Transfer: Legal and Business Considerations

- Trade Secret Protection in Employment Contracts: Non-Compete and Non-Disclosure Agreements

- Trade Secret Misappropriation in Supply Chains: Legal Implications and Risk Mitigation

- Trade Secret Law and Artificial Intelligence: Ownership and Trade Secret Protection

- Trade Secret Protection in the Era of Open Innovation and Collaborative Research

- Artificial Intelligence and Intellectual Property: Ownership and Liability Issues

- 3D Printing and Intellectual Property: Navigating the Intersection of Innovation and Copyright

- Blockchain Technology and Intellectual Property: Challenges and Opportunities

- Digital Rights Management: Addressing Copyright Protection in the Digital Era

- Open Source Software Licensing: Legal Implications and Considerations

- Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality: Legal Issues in Content Creation and Distribution

- Internet of Things (IoT) and Intellectual Property: Legal Challenges and Policy Considerations

- Big Data and Intellectual Property: Privacy and Data Protection Concerns

- Artificial Intelligence and Patent Offices: Automation and Efficiency Implications

- Intellectual Property Implications of 5G Technology: Connectivity and Innovation Challenges

- Music Copyright and Streaming Services: Analyzing Legal Challenges and Solutions

- Fair Use in Documentary Films: Balancing Copyright Protection and Freedom of Expression

- Intellectual Property in Video Games: Legal Issues in the Gaming Industry

- Digital Piracy and Copyright Enforcement: Approaches to Tackling Online Infringement

- Personality Rights in Media: Balancing Privacy and Freedom of the Press

- Streaming Services and Copyright Licensing: Legal Challenges and Royalty Distribution

- Fair Use in Parody and Satire: Analyzing the Boundaries of Creative Expression

- Copyright Protection for User-Generated Content: Balancing Authorship and Ownership

- Media Censorship and Intellectual Property: Implications for Freedom of Information

- Virtual Influencers and Copyright: Legal Challenges in the Age of AI-Generated Content

- Intellectual Property Protection in Developing Countries: Promoting Innovation and Access to Knowledge

- Cross-Border Intellectual Property Litigation: Jurisdictional Challenges and Solutions

- Trade Agreements and Intellectual Property: Impact on Global Innovation and Access to Medicines

- Harmonization of Intellectual Property Laws: Prospects and Challenges for International Cooperation

- Indigenous Knowledge and Intellectual Property: Addressing Cultural Appropriation and Protection

- Intellectual Property and Global Public Health: Balancing Innovation and Access to Medicines

- Geographical Indications in International Trade: Legal Framework and Market Exclusivity

- International Licensing and Technology Transfer: Legal Considerations for Multinational Corporations

- Intellectual Property Enforcement in the Digital Marketplace: Comparative Analysis of International Laws

- Digital Copyright and Cross-Border E-Commerce: Legal Implications for Online Businesses

- Intellectual Property Strategy for Startups: Maximizing Value and Mitigating Risk

- Licensing and Franchising: Legal Considerations for Expanding Intellectual Property Rights

- Intellectual Property Due Diligence in Mergers and Acquisitions: Key Legal Considerations

- Non-Disclosure Agreements: Safeguarding Trade Secrets and Confidential Information

- Intellectual Property Dispute Resolution: Arbitration and Mediation as Alternative Methods

- Intellectual Property Valuation: Methods and Challenges for Business and Investment Decisions

- Technology Licensing and Transfer Pricing: Tax Implications for Multinational Corporations

- Intellectual Property Audits: Evaluating and Managing IP Assets for Businesses

- Trade Secret Protection and Non-Compete Clauses: Balancing Employer and Employee Interests

- Intellectual Property and Startups: Strategies for Funding and Investor Relations

- Intellectual Property and Access to Medicines: Ethical Dilemmas in Global Health

- Gene Patenting and Human Dignity: Analyzing the Moral and Legal Implications

- Intellectual Property and Indigenous Peoples: Recognizing Traditional Knowledge and Culture

- Bioethics and Biotechnology Patents: Navigating the Intersection of Science and Ethics

- Copyright, Creativity, and Freedom of Expression: Ethical Considerations in the Digital Age

- Intellectual Property and Artificial Intelligence: Ethical Implications for AI Development and Use

- Genetic Engineering and Intellectual Property: Legal and Ethical Implications

- Intellectual Property and Environmental Sustainability: Legal and Ethical Perspectives

- Cultural Heritage and Intellectual Property Rights: Preservation and Repatriation Efforts

- Intellectual Property and Social Justice: Access and Equality in the Innovation Ecosystem

- Innovation Incentives and Intellectual Property: Examining the Relationship

- Intellectual Property and Technology Transfer: Promoting Innovation and Knowledge Transfer

- Intellectual Property Rights in Research Collaborations: Balancing Interests and Collaborative Innovation

- Innovation Policy and Patent Law: Impact on Technology and Economic Growth

- Intellectual Property and Open Innovation: Collaborative Models and Legal Implications

- Intellectual Property and Startups: Fostering Innovation and Entrepreneurship

- Intellectual Property and University Technology Transfer: Challenges and Opportunities

- Open Access and Intellectual Property: Balancing Public Goods and Commercial Interests

- Intellectual Property and Creative Industries: Promoting Cultural and Economic Development

- Intellectual Property and Sustainable Development Goals: Aligning Innovation with Global Priorities

The intellectual property law research paper topics presented here are intended to inspire students and researchers to delve into the complexities of intellectual property law and explore emerging issues in this ever-evolving field. Each topic offers a unique opportunity to engage with legal principles, societal implications, and practical challenges. As the landscape of intellectual property law continues to evolve, there remains an exciting realm of uncharted research areas, waiting to be explored. Through in-depth research and critical analysis, students can contribute to the advancement of intellectual property law and its impact on innovation, creativity, and society at large.

Exploring the Range of Topics in Human Rights Law

Human rights law is a vital field of study that delves into the protection and promotion of fundamental rights and freedoms for all individuals. As a cornerstone of international law, human rights law addresses various issues, ranging from civil and political rights to economic, social, and cultural rights. It aims to safeguard the inherent dignity and worth of every human being, regardless of their race, religion, gender, nationality, or other characteristics. In this section, we will explore the diverse and expansive landscape of intellectual property law research paper topics, shedding light on its significance and the vast array of areas where students can conduct meaningful research.

- Historical Perspectives on Human Rights : Understanding the historical evolution of human rights is essential to comprehend the principles and norms that underpin modern international human rights law. Research papers in this category may explore the origins of human rights, the impact of significant historical events on the development of human rights norms, and the role of key figures and organizations in shaping the human rights framework.

- Human Rights and Social Justice : This category delves into the intersection of human rights law and social justice. Intellectual property law research paper topics may encompass the role of human rights in addressing issues of poverty, inequality, discrimination, and marginalization. Researchers can analyze how human rights mechanisms and legal instruments contribute to advancing social justice and promoting inclusivity within societies.

- Gender Equality and Women’s Rights : Gender equality and women’s rights remain crucial subjects in human rights law. Research papers in this area may explore the legal protections for women’s rights, the challenges in achieving gender equality, and the impact of cultural and societal norms on women’s human rights. Intellectual property law research paper topics may also address specific issues such as violence against women, gender-based discrimination, and the role of women in peacebuilding and conflict resolution.

- Freedom of Expression and Media Rights : The right to freedom of expression is a fundamental human right that forms the basis of democratic societies. In this category, researchers can examine the legal dimensions of freedom of expression, including its limitations, the role of media in promoting human rights, and the challenges in balancing freedom of expression with other rights and interests.

- Human Rights in Armed Conflicts and Peacebuilding : Armed conflicts have severe implications for human rights, necessitating robust legal frameworks for protection. Topics in this category may focus on humanitarian law, the rights of civilians during armed conflicts, and the role of international organizations in peacebuilding and post-conflict reconstruction.

- Refugee and Migration Rights : With the global refugee crisis and migration challenges, this category addresses the legal protections and challenges faced by refugees and migrants. Research papers may delve into the rights of asylum seekers, the principle of non-refoulement, and the legal obligations of states in providing humanitarian assistance and protection to displaced populations.

- Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights : Economic, social, and cultural rights are integral to human rights law, ensuring the well-being and dignity of individuals. Topics may explore the right to education, health, housing, and adequate standards of living. Researchers may also examine the justiciability and enforcement of these rights at national and international levels.

- Human Rights and Technology : The digital age presents new challenges and opportunities for human rights. Research in this category can explore the impact of technology on privacy rights, freedom of expression, and the right to access information. Intellectual property law research paper topics may also cover the use of artificial intelligence and algorithms in decision-making processes and their potential implications for human rights.

- Environmental Justice and Human Rights : Environmental degradation has significant human rights implications. Researchers can investigate the intersection of environmental protection and human rights, examining the right to a healthy environment, the rights of indigenous communities, and the role of human rights law in addressing climate change.

- Business and Human Rights : The responsibilities of corporations in upholding human rights have gained increasing attention. This category focuses on corporate social responsibility, human rights due diligence, and legal mechanisms to hold businesses accountable for human rights violations.

The realm of human rights law offers an expansive and dynamic platform for research and exploration. As the international community continues to grapple with pressing human rights issues, students have a unique opportunity to contribute to the discourse and advance human rights protections worldwide. Whether examining historical perspectives, social justice, gender equality, freedom of expression, or other critical areas, research in human rights law is a compelling endeavor that can make a positive impact on the lives of people globally.

How to Choose an Intellectual Property Law Topic

Choosing the right intellectual property law research paper topic is a crucial step in the academic journey of law students. Intellectual property law is a multifaceted and rapidly evolving field that covers a wide range of subjects, including patents, copyrights, trademarks, trade secrets, and more. With such diversity, selecting a compelling and relevant research topic can be both challenging and exciting. In this section, we will explore ten practical tips to help students navigate the process of choosing an engaging and impactful intellectual property law research paper topic.

- Identify Your Interests and Passion : The first step in selecting a research paper topic in intellectual property law is to identify your personal interests and passion within the field. Consider what aspects of intellectual property law resonate with you the most. Are you fascinated by the intricacies of patent law and its role in promoting innovation? Or perhaps you have a keen interest in copyright law and its influence on creative expression? By choosing a topic that aligns with your passions, you are more likely to stay motivated and engaged throughout the research process.

- Stay Updated on Current Developments : Intellectual property law is a dynamic area with continuous developments and emerging trends. To choose a relevant and timely research topic, it is essential to stay updated on recent court decisions, legislative changes, and emerging issues in the field. Follow reputable legal news sources, academic journals, and intellectual property law blogs to remain informed about the latest developments.

- Narrow Down the Scope : Given the vastness of intellectual property law, it is essential to narrow down the scope of your research paper topic. Focus on a specific subfield or issue within intellectual property law that interests you the most. For example, you may choose to explore the legal challenges of protecting digital copyrights in the music industry or the ethical implications of gene patenting in biotechnology.

- Conduct Preliminary Research : Before finalizing your research paper topic, conduct preliminary research to gain a better understanding of the existing literature and debates surrounding the chosen subject. This will help you assess the availability of research material and identify any gaps or areas for further exploration.

- Review Case Law and Legal Precedents : In intellectual property law, case law plays a crucial role in shaping legal principles and interpretations. Analyzing landmark court decisions and legal precedents in your chosen area can provide valuable insights and serve as a foundation for your research paper.

- Consult with Professors and Experts : Seek guidance from your professors or intellectual property law experts regarding potential intellectual property law research paper topics. They can offer valuable insights, suggest relevant readings, and provide feedback on the feasibility and relevance of your chosen topic.

- Consider Practical Applications : Intellectual property law has real-world implications and applications. Consider choosing a research topic that has practical significance and addresses real challenges faced by individuals, businesses, or society at large. For example, you might explore the role of intellectual property in facilitating technology transfer in developing countries or the impact of intellectual property rights on access to medicines.

- Analyze International Perspectives : Intellectual property law is not confined to national boundaries; it has significant international dimensions. Analyzing the differences and similarities in intellectual property regimes across different countries can offer a comparative perspective and enrich your research paper.

- Propose Solutions to Existing Problems : A compelling research paper in intellectual property law can propose innovative solutions to existing problems or challenges in the field. Consider focusing on an area where there are unresolved debates or conflicting interests and offer well-reasoned solutions based on legal analysis and policy considerations.

- Seek Feedback and Refine Your Topic : Once you have narrowed down your research paper topic, seek feedback from peers, professors, or mentors. Be open to refining your topic based on constructive criticism and suggestions. A well-defined and thoughtfully chosen research topic will set the stage for a successful and impactful research paper.

Choosing the right intellectual property law research paper topic requires careful consideration, passion, and a keen awareness of current developments in the field. By identifying your interests, staying updated on legal developments, narrowing down the scope, conducting preliminary research, and seeking guidance from experts, you can select a compelling and relevant topic that contributes to the academic discourse in intellectual property law. A well-chosen research topic will not only showcase your expertise and analytical skills but also provide valuable insights into the complexities and challenges of intellectual property law in the modern world.

How to Write an Intellectual Property Law Research Paper

Writing an intellectual property law research paper can be an intellectually stimulating and rewarding experience. However, it can also be a daunting task, especially for students who are new to the intricacies of legal research and academic writing. In this section, we will provide a comprehensive guide on how to write an effective and impactful intellectual property law research paper. From understanding the structure and components of the paper to conducting thorough research and crafting compelling arguments, these ten tips will help you navigate the writing process with confidence and proficiency.

- Understand the Paper Requirements : Before diving into the writing process, carefully review the requirements and guidelines provided by your professor or institution. Pay attention to the paper’s length, formatting style (APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, Harvard, etc.), citation guidelines, and any specific instructions regarding the research paper topic or research methods.

- Conduct In-Depth Research : A strong intellectual property law research paper is built on a foundation of comprehensive and credible research. Utilize academic databases, legal journals, books, and reputable online sources to gather relevant literature and legal precedents related to your chosen topic. Ensure that your research covers a wide range of perspectives and presents a well-rounded analysis of the subject matter.

- Develop a Clear Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the central argument of your research paper. It should be concise, specific, and clearly convey the main point you will be arguing throughout the paper. Your thesis statement should reflect the significance of your research topic and its contribution to the field of intellectual property law.

- Create an Outline : An outline is a roadmap for your research paper, helping you organize your thoughts and ideas in a logical and coherent manner. Divide your paper into sections, each representing a key aspect of your argument. Within each section, outline the main points you will address and the evidence or analysis that supports your claims.

- Introduction : Engage and Provide Context: The introduction of your research paper should captivate the reader’s attention and provide essential context for your study. Start with a compelling opening sentence or anecdote that highlights the importance of the topic. Clearly state your thesis statement and provide an overview of the main points you will explore in the paper.

- Literature Review : In the early sections of your research paper, include a literature review that summarizes the existing research and scholarship on your topic. Analyze the key theories, legal doctrines, and debates surrounding the subject matter. Use this section to demonstrate your understanding of the existing literature and to identify gaps or areas where your research will contribute.

- Legal Analysis and Argumentation : The heart of your intellectual property law research paper lies in your legal analysis and argumentation. Each section of the paper should present a well-structured and coherent argument supported by legal reasoning, case law, and relevant statutes. Clearly explain the legal principles and doctrines you are applying and provide evidence to support your conclusions.

- Consider Policy Implications : Intellectual property law often involves complex policy considerations. As you present your legal arguments, consider the broader policy implications of your research findings. Discuss how your proposed solutions or interpretations align with societal interests and contribute to the advancement of intellectual property law.

- Anticipate Counterarguments : To strengthen your research paper, anticipate potential counterarguments to your thesis and address them thoughtfully. Acknowledging and refuting counterarguments demonstrate the depth of your analysis and the validity of your position.

- Conclusion : Recapitulate and Reflect: In the conclusion of your research paper, recapitulate your main arguments and restate your thesis statement. Reflect on the insights gained from your research and highlight the significance of your findings. Avoid introducing new information in the conclusion and instead, offer recommendations for further research or policy implications.

Writing an intellectual property law research paper requires meticulous research, careful analysis, and persuasive argumentation. By following the tips provided in this section, you can confidently navigate the writing process and create an impactful research paper that contributes to the field of intellectual property law. Remember to adhere to academic integrity and proper citation practices throughout your research, and seek feedback from peers or professors to enhance the quality and rigor of your work. A well-crafted research paper will not only demonstrate your expertise in the field but also provide valuable insights into the complexities and nuances of intellectual property law.

iResearchNet’s Research Paper Writing Services

At iResearchNet, we understand the challenges that students face when tasked with writing complex and comprehensive research papers on intellectual property law topics. We recognize the importance of producing high-quality academic work that meets the rigorous standards of legal research and analysis. To support students in their academic endeavors, we offer custom intellectual property law research paper writing services tailored to meet individual needs and requirements. Our team of expert writers, well-versed in the intricacies of intellectual property law, is committed to delivering top-notch, original, and meticulously researched papers that can elevate your academic performance.

- Expert Degree-Holding Writers : Our team consists of experienced writers with advanced degrees in law and expertise in intellectual property law. They possess the necessary knowledge and research skills to create well-crafted research papers that showcase a profound understanding of the subject matter.

- Custom Written Works : We take pride in producing custom-written research papers that are unique to each client. When you place an order with iResearchNet, you can be assured that your paper will be tailored to your specific instructions and requirements.

- In-Depth Research : Our writers conduct thorough and comprehensive research to ensure that your intellectual property law research paper is well-supported by relevant legal sources and up-to-date literature.

- Custom Formatting : Our writers are well-versed in various citation styles, including APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, and Harvard. We will format your research paper according to your specified citation style, ensuring accuracy and consistency throughout the paper.

- Top Quality : We are committed to delivering research papers of the highest quality. Our team of editors reviews each paper to ensure that it meets the required academic standards and adheres to your instructions.

- Customized Solutions : At iResearchNet, we recognize that each research paper is unique and requires a tailored approach. Our writers take the time to understand your specific research objectives and create a paper that aligns with your academic goals.

- Flexible Pricing : We offer competitive and flexible pricing options to accommodate students with varying budget constraints. Our pricing is transparent, and there are no hidden fees or additional charges.

- Short Deadlines : We understand that students may face tight deadlines. Our writers are skilled in working efficiently without compromising the quality of the research paper. We offer short turnaround times, including deadlines as tight as 3 hours.

- Timely Delivery : Punctuality is a priority at iResearchNet. We ensure that your completed research paper is delivered to you on time, allowing you ample time for review and any necessary revisions.

- 24/7 Support : Our customer support team is available 24/7 to assist you with any queries or concerns you may have. Feel free to contact us at any time, and we will promptly address your needs.

- Absolute Privacy : We value your privacy and confidentiality. Your personal information and order details are treated with the utmost confidentiality, and we never share your data with third parties.

- Easy Order Tracking : Our user-friendly platform allows you to easily track the progress of your research paper. You can communicate directly with your assigned writer and stay updated on the status of your order.

- Money-Back Guarantee : We are committed to customer satisfaction. If, for any reason, you are not satisfied with the quality of the research paper, we offer a money-back guarantee.

When it comes to writing an exceptional intellectual property law research paper, iResearchNet is your reliable partner. With our team of expert writers, commitment to quality, and customer-centric approach, we are dedicated to helping you succeed in your academic pursuits. Whether you need assistance with choosing a research paper topic, conducting in-depth research, or crafting a compelling argument, our custom writing services are designed to provide you with the support and expertise you need. Place your order with iResearchNet today and unlock the full potential of your intellectual property law research.

Unlock Your Full Potential with iResearchNet

Are you ready to take your intellectual property law research to new heights? Look no further than iResearchNet for comprehensive and professional support in crafting your research papers. Our custom writing services are tailored to cater to your unique academic needs, ensuring that you achieve academic excellence and stand out in your studies. Let us be your trusted partner in the journey of intellectual exploration and legal research.

Take the first step toward unleashing the full potential of your intellectual property law research. Place your order with iResearchNet and experience the difference of working with a professional and reliable custom writing service. Our team of dedicated writers and exceptional customer support are here to support you every step of the way. Don’t let the challenges of intellectual property law research hold you back; empower yourself with the assistance of iResearchNet and set yourself up for academic success.

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

Intellectual Property Rights: What Researchers Need to Know

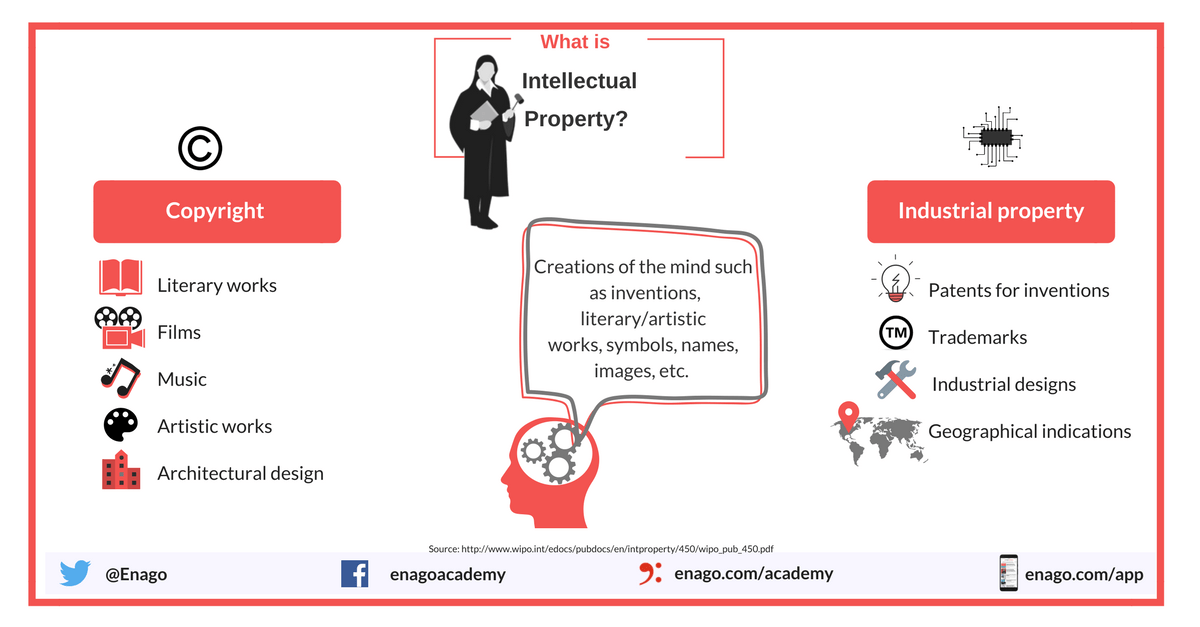

Intellectual property rights help protect creations of the mind that include inventions, literary or artistic work, images, symbols, etc. If you create a product, publish a book, or find a new drug, intellectual property rights ensure that you benefit from your work. These rights protect your creation or work from unfair use by others. In this article, we will discuss different types of intellectual property rights and learn how they can help researchers.

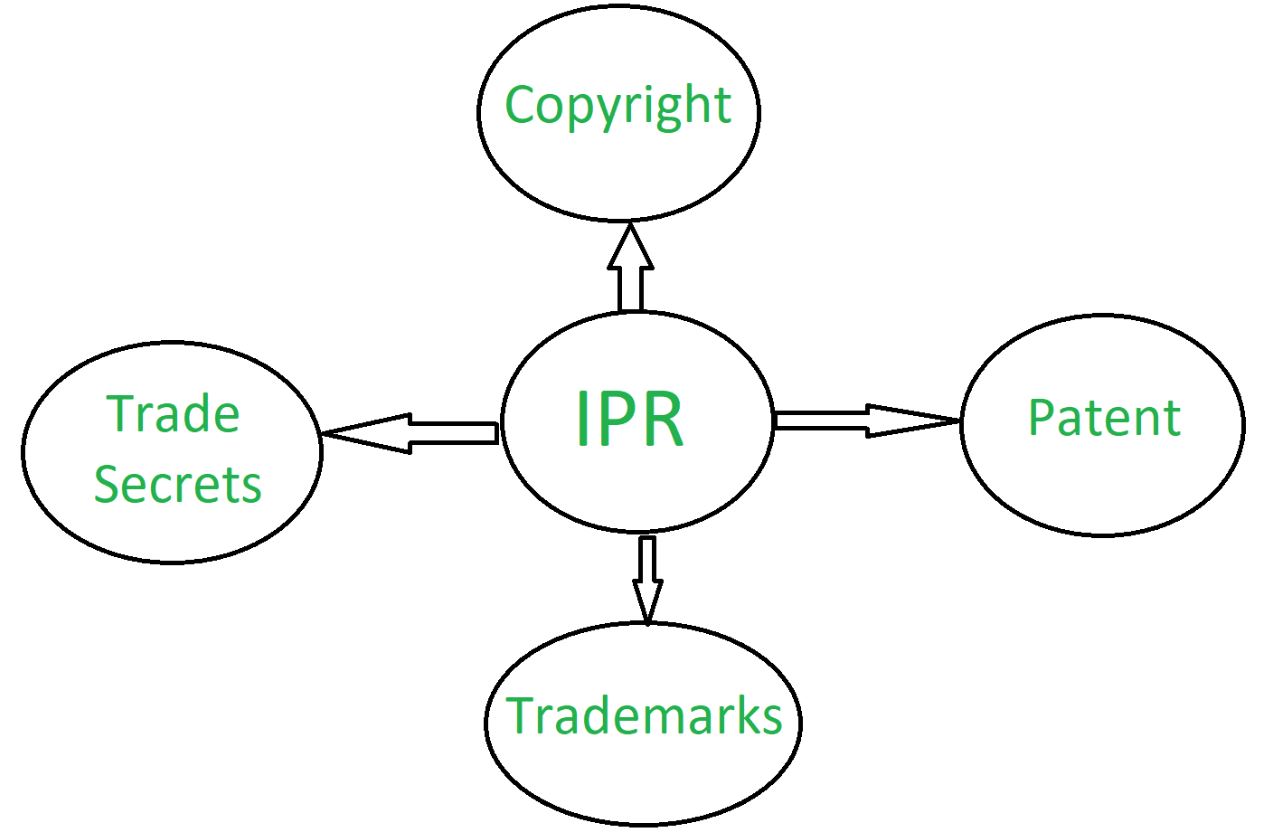

Types of Intellectual Property Rights

There are two main types of intellectual property rights (IPR).

- Copyrights and related rights

- Industrial property

Copyrights give authors the right to protect their work.

It covers databases, reference works, computer programs, architecture, books, technical drawings, and others.

By copyrighting your work, you ensure that others cannot use it without your permission.

Industrial property rights include trademarks, patents, geographical indications, and industrial designs.

- A trademark is a unique sign used to identify a product or a service. It can be a single word or a combination of words and numbers. Drawings, 3-D signs, or even symbols can constitute a trademark. For instance, Google is a famous trademark. The trademark application can be filed at national or regional levels depending on the extent of protection required.

- A patent is an exclusive right to an invention that introduces a new solution or a technique. If you own a patent, you are the only person who can manufacture, distribute, sell, or commercially use that product. Patents are usually granted for a period of 20 years. The technology that powers self-driving cars is an example of a patented invention.

- A geographical indication states that a product belongs to a specific region and has quality or reputation owing to that region. Olive oil from Tuscany is a product protected by geographical indication.

- An industrial design is what makes a product unique and attractive. These may include 3-D (shape or surface of an object) or 2-D (lines or patterns) features. The shape of a glass Coca-Cola bottle is an example of the industrial design.

What Do I Need to Know About IPR?

Intellectual property rights are governed by WIPO , the World Intellectual Property Organization. WIPO harmonizes global policy and protects IPR across borders. As a researcher, you rely on the published work to create a new hypothesis or to support your findings. You should, therefore, ensure that you do not infringe the copyright of the owner or author of the published work (images, extracts, figures, data, etc.)

When you refer to a book chapter or a research paper , make sure to provide appropriate credit and avoid plagiarism by using effective paraphrasing , summarizing, or quoting the required content. Remember plagiarism is a serious misconduct! It is important to cite the original work in your manuscript. Copyright also covers images, figures, data, etc. Authors must get appropriate written permission to use copyrighted images before using them in the manuscripts or thesis.

How do you decide whether to publish or patent? Check your local IPR laws. IPR laws vary between countries and regions. In the US, a patent will not be granted for an idea that has already been published. Researchers, therefore, are advised to file a patent application before publishing a paper on their invention. Discussing an invention in public is what is known as public disclosure . In the US, for instance, a researcher has one year from the time of public disclosure to file a patent. However, in Europe, a researcher who has already disclosed his or her invention publicly loses the right to file a patent immediately.

IPR and Collaborative Research

IPR laws can impact international research collaboration. Researchers should take national differences into account when planning global collaboration. For example, researchers in the US or Japan collaborating with researchers in the EU must agree to restrict public disclosure or publication before filing a patent. In the US, it is common for publicly funded universities to retain patent ownership. However, in Europe , there are different options . An ideal collaboration provides everyone involved with the maximum ownership of patent rights. Several entities specialize in organizing international research collaborations. Researchers can also consider engaging with such a company to manage IPR.

What questions do you have about IPR? Have you faced any situation where you need to consider IPR issues when conducting or publishing your research ? Please let us know your thoughts in the comments below.

Wow, I never knew that geographical indication can have a connection to intellectual property if it has distinctions that can be attributed to where it came from. After finishing my master’s degree, I think I’m going to be staying in the academe as a researcher so it’s quite helpful to know more about how the intricacies of IP can affect research. I hope I can one day attend a conference about IP to learn more about its modern day advancements.

I have invented – conceived – a training system. What do I have to do to achieve and retain ownership if I enroll in a university higher degree by research program to develop this idea?

Thank you for sharing your query on our website. Regarding your query, most universities recognize as a general principle that students who are not employees of the university own the IP rights in the works they produce purely based on knowledge received from lectures and teaching. However, there may be some circumstances where ownership has to be shared or assigned to the university or a third party. These include cases when the student is being sponsored by the university, or the project is a sponsored research project or involves the academic staff of the university or university resources. If the training system conceived by you does not involve any of the above mentioned scenarios, ideally you should be able to retain its ownership. For more clarity you can check through the IP rules section of the concerned university.

Please let us know in case of any queries.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Publishing Research

- Understanding Ethics

Simple Step-by-Step Guide on How to Get Copyright Permission

It is a well-known fact that when authors submit their work to a journal, the…

- Infographic

All You Need to Know About Creative Commons Licenses

The development of technology has led to the widespread sharing of ideas including intellectual and…

Get Your Research Patented Now!

A patent is a form of intellectual property, which gives its owner the right to prevent other researchers…

How to Effectively Search and Read Patents – Tips to Researchers

Patents have two purposes: awarding rights to the inventor and preventing others from claiming ownership.…

- Industry News

- Publishing News

Does Copyright Transfer Hinder Scientific Progress?

The worlds of science and scientific publishing are deeply entwined. For many years, the best…

How Patent Searching Helps in Innovative Research

Is Pirate Black Open Access Disrupting Green & Gold Open Access?

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

Loading metrics

Open Access

Perspective

The Perspective section provides experts with a forum to comment on topical or controversial issues of broad interest.

See all article types »

Sharing Research Data and Intellectual Property Law: A Primer

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Program on Information Justice and Intellectual Property, American University, Washington College of Law, Washington, D.C., United States of America

- Michael W. Carroll

Published: August 27, 2015

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002235

- Reader Comments

Sharing research data by depositing it in connection with a published article or otherwise making data publicly available sometimes raises intellectual property questions in the minds of depositing researchers, their employers, their funders, and other researchers who seek to reuse research data. In this context or in the drafting of data management plans, common questions are (1) what are the legal rights in data; (2) who has these rights; and (3) how does one with these rights use them to share data in a way that permits or encourages productive downstream uses? Leaving to the side privacy and national security laws that regulate sharing certain types of data, this Perspective explains how to work through the general intellectual property and contractual issues for all research data.

Citation: Carroll MW (2015) Sharing Research Data and Intellectual Property Law: A Primer. PLoS Biol 13(8): e1002235. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002235

Copyright: © 2015 Michael W. Carroll. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: I have read the journal's policy and have the following conflicts: I am on the Board of Directors of Creative Commons, I am the Public Lead of Creative Commons USA, and I am on the Board of Directors of the Public Library of Science.

Abbreviations: CC, Creative Commons; CC0, Creative Commons Zero; CC BY, Creative Commons Attribution; CC BY-SA, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike; CC BY-NC, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial; CC BY-ND, Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs; CRISPR/Cas9, Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/CRISPR associated protein 9; EMBL-EBI, The European Molecular Biology Laboratory-The European Bioinformatics Institute; GNU, GNU’s Not Unix!

For the researcher seeking to use another’s data, this Perspective offers some good news and some not as good news. The good news is that if a source of data—the researcher or repository—gives permission to reuse the data and one’s intended use fits within the scope of the permission, one need not be overly concerned with the details of the discussion that follows because the permission provides the legal basis for data reuse. For example, if one seeks data from the European Bioinformatics Institute, one will find that the terms of use state that “[t]he public databases of EMBL-EBI [The European Molecular Biology Laboratory-The European Bioinformatics Institute] are freely available by any individual and for any purpose” [ 1 ]. This would appear to give any individual academic researcher permission to copy and reuse the data at will. It leaves open a question about whether an employee acting on behalf of his or her employer (is s/he acting as “an individual”?) is equally granted this permission.

There is, however, a catch. The EBI’s terms also warn the user that some third parties may claim intellectual property or other legal rights on the original data, and it is up to the researcher not to infringe these rights. This kind of legal uncertainty interferes with the productive reuse of research data. It can be avoided if the repository requires depositors to grant permission to downstream users or to give up any intellectual property rights they may have in the data. Alternatively, the final section of this Perspective describes means by which repositories can make it easy for depositors to signal the scope of the permission they grant to downstream users.

In the absence of clear permission, mapping how intellectual property law does—and does not—apply to research data may be of use. In my view, the law makes all of this far more complicated than it need be. For those seeking to pick and choose which reuses of another’s data may be permitted by law, regrettably, the answers to the above questions are more context dependent than many would like.

This is so for two reasons. First, the source of all intellectual property rights is national law. Certain international treaties harmonize intellectual property owners’ rights but leave the users’ rights to vary by country. Second, certain countries have added protection beyond what the treaties require. Specifically, the members of the European Union, candidate countries in Eastern Europe, Mexico [ 2 ], and South Korea have created a specialized database right that applies to certain databases created or maintained within their borders. These laws regulate uses of these databases only within their borders.

What Are the Legal Rights in Data?

The rights that may apply to research data are trade secrets (confidential information), copyrights, and special database rights in the EU and South Korea. Patents may apply to some forms of data, but the more common issue is that data sharing may have implications for the acquisition of patent protection in inventions that arise from research. Finally, the ability to use contracts overlays all of these rights and can be used to provide permission for reuse through licensing of underlying rights (but also to restrict reuse merely as a term and condition of granting access to data). Focusing on the case of a researcher depositing data in compliance with a journal’s publication policies, the following discusses the relevant rights and their application.

Trade Secret (Also Known As Proprietary or Confidential Information)

Most scientific researchers own trade secrets in their research data for some period of time, even if they are unaware of this fact. This is because, according to international standards, national laws treat information as a trade secret if it derives economic value from not being generally known or readily ascertainable, so long as the information has been subject to reasonable measures to keep it secret. Most research data meets this definition, at least in the early stages of collection or generation.

The ease with which trade secret protection is acquired is mirrored by the ease with which it is lost. Public disclosure of the information removes any associated trade secret protection because the information has become generally known or readily ascertainable. In commercial practice, trade secrets are routinely created and destroyed as companies develop new products and services in confidence that they then publicly disclose when they go to market. Analogously, trade secrets in research data are routinely removed through data sharing practices, including depositing in a publicly accessible repository.

In traditional academic research, trade secrecy is unlikely to be invoked unless a member of a research team decamps to another team with confidential data. The issue becomes more salient in the context of industrial research or commercially sponsored academic research. Most commercial sponsors provide for the management of trade secrets in the terms of their sponsorship agreements [ 3 ]. For example, if a researcher collaborates with a pharmaceutical company, the researcher may be contractually bound to suppress the release of research data until the sponsor has developed a patentable product. Academic researchers and their offices of sponsored projects should carefully review drafts of sponsored research agreements and clinical trial agreements to ensure they do not inappropriately restrict a researcher’s right to disseminate the results of the scientific research they have conducted. A researcher should ensure that the agreements do not permit commercial sponsors to revise, delete, or suppress information generated by the researcher. The terms and timing of disclosing research results that are trade secrets should be incorporated into the sponsored research agreements, not negotiated at the time of publication [ 3 , 4 ].

Copyright grants the author(s) of an original work the exclusive rights to reproduce the work, to publicly distribute copies, to publicly display, publicly perform, or otherwise communicate the work to the public, and to make adaptations of the work.

Understanding how copyright applies to the sharing of research data is more work than it is worth unless it is likely or plausible that the creator, owner, or repository in which data resides is likely to seek to limit copying, distribution, or other reuses of data. When such rights of control are likely to be asserted or when a third party requires evidence that all permissions for republication or reuse of data have been obtained, copyright law plays a limited but inescapable role in the sharing of research data.

Copyright law is founded on certain science-friendly policies. Copyright imposes no restrictions on the sharing of the basic building blocks of knowledge—facts and ideas—which are part of the public domain. Researchers routinely rely on this freedom to copy in their daily practice [ 5 ]. For example, the freedom to copy ideas has been an important component of the rapid propagation of the CRISPR/Cas9 (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/CRISPR associated protein 9) process for gene editing [ 6 ]. (There is a pending patent dispute about applications of this method [ 7 ], but the underlying idea that one can manipulate bacterial immune response to splice genes is in the public domain.) Similarly, raw observational and experimental data are “facts” for copyright purposes that are free to be shared and reused without copyright restriction [ 5 ].

Copyright applies to original works of authorship. For copyright purposes, an author is one who makes creative or editorial decisions about how ideas and facts are expressed. For example, the only authors of a journal article for copyright purposes are those who wrote the words or created the tables or figures. The amount of creativity or editorial discretion needed to create a work of authorship is quite minimal. As a result, some aspects of a dataset are likely to have a copyright attached to them. Copying the whole dataset will involve copying the copyrighted layer. Additionally, separate copyrights can attach to data items, organizational structures, and metadata ( Box 1 ).

Box 1. Layers of Copyrights in Databases

Copyright at the item level is limited to items that involve expressive choice, such as drawings or photographs. For example, if one treats the images in the Encyclopedia of Life as data items, the very large majority of these have enough creative expression to be copyrightable. However, the copyright is limited to the expression that the author created. One would not be exercising any rights under copyright by creating a drawing of an animal depicted in a photograph. The photographer is not the author of the animal’s characteristics. The author’s copyright is limited to this particular expression through the way the shot is composed, lit, and focused, for example. Otherwise, at the item level, most data expressed as numeric values are likely to be “facts” that are in the public domain. This means that even if there is a copyright at the organizational level, these numeric values can be copied and reused without any copyright restrictions.

At the organization layer, a separate copyright can arise with respect to the manner in which data are selected and arranged. For example, even the organization of an Excel spreadsheet could be copyrightable if a researcher exercised discretion in selecting field names and arranging their order. However, the copyright that would arise would be limited to this layer of the dataset. Another researcher would not be infringing any of the rights associated with this work if s/he were to republish the data in a spreadsheet with renamed and reorganized fields. As the amount of organizational choice increases in, for example, the structure of a relational database, the amount of copyrightable expression increases as well.

Annotations, visualizations, and other forms of metadata can receive separate copyright protection if they are sufficiently original. Creating visualizations, figures, charts, graphs, and other forms of “processing” of research data often involves the kinds of discretionary decisions about expression to which copyright applies, and copyright becomes an issue for a user who seeks to reuse these forms of original expression. Finally, compilations of datasets—used in meta-analysis, for example—might receive a separate copyright if the selection and arrangement of these involve sufficient discretionary choice. Such a copyright would apply only to this selection and arrangement and not to any of the underlying items or organizational features of individual datasets.

In cases in which copyright attaches to some aspect of research data relevant to a potential user, it becomes important to know which copyright(s) regulate(s) a proposed use. These rights in the copyrighted layer of a dataset give the owner a legal hook to seek to control the reproduction or distribution of datasets and visualizations.

When copyright does govern a proposed use of data, the use may be permitted by users’ rights that are expressed as exceptions or limitations to the copyright owner’s rights. These users’ rights vary by country or region ( Box 2 ). For example, countries whose law is based on that of the United Kingdom have a flexible provision called fair dealing that resembles fair use but is somewhat more limited. A fair dealing analysis involves a first step of determining whether the use fits within one of the categorically eligible types of use. Using a copyrighted work for noncommercial research or private study or criticism or review are examples of categorically acceptable uses. Such a use does not infringe copyright if it is “fair dealing,” which is determined by balancing similar considerations about the purpose of the use, the extent of the work used, and the effect of the use on the copyright owner. In the rest of Europe, countries also have the option—but not a requirement—to provide exceptions for these same uses. The picture of users’ rights becomes even more of a patchwork as one extends the lens to the rest of the world.

Countries also provide authors with some level of moral rights in their works of authorship. These rights are personal to the author and cannot be transferred. Authors have the right to be attributed as such. Authors also have the right to not be attributed if they no longer wish to be associated with the work. A strong version of moral rights even gives the author the right to retract a work from publication and to enjoin any further publication or duplication. Other rights include the right of integrity in the work, which limits adaptations to those that do not harm the reputation of the author. Of these, the attribution right is likely the one with the most salience in the context of data reuse.

Box 2. National Variation in Users’ Rights in Copyright Law

The scope of copyright control is limited by statutory limitations and exceptions to the copyright owner’s exclusive rights that permit certain reuses by law. These limitations and exceptions have not been harmonized internationally. As a result, the freedom to use the copyrighted layer of a dataset—by, for example, copying the whole set—without permission depends upon the country in which the copying takes place. This is a prime example of how and where the law is far more complex than necessary to chart the basic rules for when data sharing is permitted by law and when the presence of a copyrighted layer would require the copyright owner’s permission.

All countries have a targeted list of uses that are permitted by law, but these lists vary considerably, and the identified uses can often be defined quite specifically and narrowly. For example, the UK recently amended its copyright law to explicitly permit researchers to content mine the research literature because its Parliament was uncertain whether the existing limitations and exceptions would permit the copying necessary to engage in content mining [ 8 ].

A number of other countries also have a flexible exception that requires a balancing of considerations to determine whether the use is permitted. The most clear-cut example is the fair use doctrine in the United States and Israel. Under this rule, one considers the nature and purpose of the use, how much authorship is in the source work, how much of the author’s expression has been taken in the use, and whether the use has an adverse effect on the copyright owner’s ability to economically exploit the work. Relevant to this discussion, courts have found that copying the copyrighted layer of a work is fair use if the purpose is to extract the public domain information incorporated in the work.

Sui Generis Database Rights—Europe and South Korea

In the EU, certain candidate countries in Eastern Europe, and South Korea, research data may also be subject to a special database right. Mexico also protects databases that do not qualify for copyright protection, but its measures are not discussed here. Keep in mind that what follows applies only to (1) databases that are created or maintained within the borders of EU member states or South Korea and (2) uses of these protected databases that take place within these territories. As frustrating as this may be to a globalized research community, in a narrow class of cases, this right could apply to a download of a substantial amount of data that takes place on a computer connected to the Internet in Europe or South Korea, but not elsewhere.

Under the EU’s Database Directive [ 9 ], these special rights apply to any database that requires a “substantial investment” to assemble or maintain. As interpreted by the Court of Justice of the European Union (“Court of Justice”), this right is limited to those databases that require investments in the obtaining of data, not the creation of the underlying data [ 10 ]. This means that a sole source database, like a sporting events schedule, generally does not enjoy protection, while publishers of directories or lists can maintain protection if they only obtain data from others, not create it themselves. This sui generis right in the nonoriginal (i.e., not subject to copyright) portions of a database lasts for 15 years.

Sui generis database rights protect against the extraction or reutilization of substantial parts of a protected database as well as frequent extraction of insubstantial parts of a protected database. This legal right would be a significant barrier to sharing research data were it not subject to a limitation for noncommercial research. A great deal of research data likely meets the threshold requirement of “substantial investment” of financial resources and labor because of its capacious definition, but a substantial amount of university or nonprofit hospital use of such data likely qualifies for the limitation. A risk remains that increased commercial sponsorship of academic research may test the boundaries of this “noncommercial” exception.

One user-friendly provision of the Database Directive is that it greatly limits the ability of a database owner to use terms of use or other forms of contractual agreement to add use restrictions that exceed those in the Directive—by, for example, prohibiting the occasional extraction or republication of insubstantial amounts of data taken from the database. In a recent odd twist, the Court of Justice has determined that if a database lacks both copyright protection and protection under the Directive, then the owner’s terms of use will be enforceable [ 11 ].

The impact of disclosing or sharing research data on patent rights can be easily overstated by those seeking legal cover to avoid sharing data. However, the issue is not entirely fabricated because there are situations in which data sharing may have an adverse effect on a party seeking patent protection.

Patents are exclusive rights in inventions. An invention is patentable if it is new, useful, and demonstrates an inventive step over what is already known within the relevant field of knowledge. Unlike the rights described above, patents only arise if they are applied for and granted by a public authority. In most countries, the application process requires an examination to determine if the legal requirements for patent protection are met. In a few countries, such as South Africa, one need only register one’s claim to receive a patent. As with other intellectual property rights, a patent applies only to uses that take place at least in part within the borders of the country from which a patent has issued.

The putative risk of data sharing arises because public disclosure of an invention prior to filing a patent application can destroy or impair one’s right to obtain patent protection for the invention [ 3 ]. However, most research data are not eligible to be protected as inventions as such. (Whether research data is capable of being a patentable invention depends upon how elastic one’s definition of “data” is. If genetically modified organisms are “data,” for example, then such data very likely are eligible for patent protection and any intended patent applications should be filed prior to their public disclosure.) Instead, the invention is far more likely to be disclosed through the publication of an associated research article than by the sharing of data.

When a published research article teaches the public everything about inventions arising from research that data deposit does, then the deposition has no more impact on patentability than the decision to publish had. For this reason, the rules that researchers must abide by for disclosing inventions to their university or other employer or funder prior to publishing a research article should be read to include disclosure prior to depositing associated data as well [ 3 , 12 ].

There may be cases in which data deposit has a marginal additional impact on patentability of inventions arising from research reported in an article. One such case would be when the article does not describe the invention but the data do. Another case would be one in which the data disclosure fills a gap in other researchers’ knowledge such that inventions that arise from the research are not described by the data but rendered “obvious” to one skilled in the art by the disclosure. Once an invention becomes obvious, it lacks the required inventive step needed to obtain protection.

A separate patent issue for data sharing arises when a patented process claims the steps involved in data sharing or reuse. A patent grants the owner the rights to exclude others from making, using, selling, offering to sell, or importing the invention. Use of an invention is interpreted quite broadly. A patentable process could claim a series of steps that would be practiced in connection with certain forms of data reuse. This issue is so context dependent that little more than raising it as a consideration can be done here.

Who Holds These Rights?

This question becomes relevant when one wishes to assert intellectual property control or when one must seek permission to make an intended use of another’s research data. Usually the person who creates or generates the intellectual property is the initial owner of these rights. When the creator is an employee, determining who holds the rights becomes more complicated, and national variation reemerges as an issue. Finally, all of these rights are transferable (except moral rights in copyright), so the initial owner may no longer be the rights holder.

Trade Secret

Employers generally own trade secrets that are developed by their employees within the scope of their employment. This rule certainly encompasses the research data generated or collected by an industrial researcher. Whether or how this rule applies in the academic research context is not clear. In the absence of an agreement or policy that applies to trade secrets, student or independent researchers would own any trade secret rights associated with their data. Whether an employee of a university or hospital creates or collects data within the scope of employment is a subject of theoretical interest. In practice, however, the rules of ownership are routinely altered or determined contractually. Sponsored research agreements and university or hospital intellectual property policies generally establish the rules for ownership and disclosure of trade secrets [ 3 , 4 ].

Copyright is owned initially by the author(s) of a copyrighted work. For copyright purposes, the author is the person or persons who make the creative or editorial decisions about how to express the underlying facts and ideas. This is a much more constrained version of authorship than applies in science. This gap between what science and copyright law values is readily seen in how credit is distributed for a scientific publication. Scientists recognize that results emerge from team effort, and scientists have developed conventions about who is listed as an author and in what order to signal this recognition to the broader community. For copyright purposes, however, only those members of the team who expressed themselves by writing the words, drawing the figures, or otherwise creating original expression are authors with rights under copyright.

Thus, if there is a copyright layer to a dataset or database, the owner(s) of the copyright(s) associated with this layer would be the one(s) who chose how to organize, arrange, annotate, or visualize the data rather than the one(s) involved in its generation or collection [ 5 ].

When the copyrighted work is created by an employee within the scope of employment, a national division emerges. In the US, under the work-made-for-hire rule, the employer is treated as the author, and the employee has no rights [ 13 ]. Whether this rule applies to the research and teaching materials created by university employees is the subject of a division of opinion. Some argue the rule does not apply to research outputs either because the particular research from which the data arise may not be considered within the scope of employment or because prior law had recognized a “teacher exception” to the rule that may have been implicitly carried forward into current law. On its face, current law does not state any exceptions to the rule. In the rest of the world, the individual creator(s) start(s) with the rights, but these may automatically be transferred to the employer if the employment agreement provides for this.

The holder of sui generis database rights is the person or entity that makes the substantial investment in collecting data from other sources or maintaining the database. In the research context, these rights usually will belong to data aggregators and repositories rather than individual researchers or research teams.

Patent applications generally must be filed in the name of the inventor(s). The rights in the patent, however, can be assigned to another party. By agreement, employees routinely assign the rights in their inventions to their employer. University and hospital employment agreements and policies often require that researchers assign rights to inventions arising under sponsored research agreements to their employer as well. Academic institutions sometimes hold more patents than both the government and commercial businesses. For example, the University of California and The John Hopkins University were both in the top 15 holders of deoxyribonucleic acid patents in 2004 [ 14 ].

Recommendations for Increasing Data Sharing and Openness

Contracts and licenses.

When one or more intellectual property rights apply to research data, the owner of such rights can grant permission for reuse through a license. In legal terms, a grant of permission is a nonexclusive license. An exclusive license is one in which the rights holder agrees to give up any rights to use the intellectual property, usually in return for some form of compensation.

From a legal perspective, terms of use or other “licenses” fall into one of two groups. In the first group, there is an underlying intellectual property right associated with data that would be violated by the user in the absence of the permission granted by the terms. That is an intellectual property license. Violation of such a license could lead to a court order requiring the user to cease any further use. Damages and attorneys’ fees may also be assessed against the breaching user.

In the second group, there is a collection of data that has no underlying intellectual property right associated with it, such as a large collection of sensor data that is organized in an unoriginal manner—say, chronologically. If one were to download these data from a site with “terms of use” associated, those terms are still enforceable as a contractual agreement, but there would be no intellectual property right to infringe. Enforcing any use restrictions in this second group of agreements is much more difficult because the author of the terms has to prove that the use has caused measureable economic damages.

Although there are policy arguments against enforcing the terms of use in this second group—because they impose use restrictions on data that intellectual property law treats as in the public domain—courts in the US and elsewhere generally have found these terms of use to be enforceable as long as the basic requirements for voluntary agreements have been met. For example, a Maryland district court upheld a terms-of-use agreement even when a third-party user obtained database access merely by clicking a box to accept, but failed to review, the terms of use [ 15 ].

Since the practice is legal and enforceable, it should be a topic for community discussion whether it is ethical or appropriate to condition access to data on agreement to a contract that imposes use restrictions on data that is otherwise free of any intellectual property rights.

Clarifying the Terms of Use

As the discussion above demonstrates, it is not often clear to a potential user of data whether any intellectual property rights are associated with the data and, if there are, who owns these. To promote data reuse, it is incumbent on the owner(s) of these rights to mark the data with the associated permissions. Otherwise, one ends up with the muddy rules set forth by the EBI outlined at the opening of this Perspective.

Removing or Limiting Rights Restrictions

Trade secret..

The easiest way to grant permission to use a trade secret associated with data is to get rid of it by publicly disclosing or depositing the data. Otherwise, some form of confidentiality or nondisclosure agreement would be needed to preserve the trade secret(s) while permitting their reuse by a closed group of other researchers.

As discussed above, public disclosure can also limit or destroy the ability to obtain patent rights in inventions associated with data. When a patent covers the collection, generation, or use of research data, the owner can grant permission to practice the process through a nonexclusive license or through a public statement that the patent will not be asserted against researchers practicing the process in connection with their research.

Copyright and database rights.

These rights are more persistent than trade secrets or patents. However, they also can be permanently removed in most parts of the world if the owner of the rights publicly and unequivocally states his or her intention to permanently relinquish these rights. Creative Commons provides a tool called CC0 (CC Zero) to accomplish this task. In countries that deny owners the right to relinquish these rights (yes, it happens), CC0 functions as a license that imposes no constraints on the user ( Box 3 ).

Box 3. Creative Commons

Creative Commons is a global organization that promotes the sharing and reuse of creative, educational, and scientific works by supplying standardized public licenses that anyone can use to permit reuse of works they created or to which they own the rights. The primary tools are six copyright licenses, a copyright waiver, and a label that indicates that a work is free from copyright and in the public domain. The six licenses and the CC0 waiver are designed to respond to creators who have different appetites for reuse of their works. As is indicated in the body of this Perspective, CC0 is a way to dedicate a work to the public domain by waiving all rights under copyright and any sui generis database rights that may apply. This tool is used by those who create public domain clipart, for example, and in connection with sharing data for which copyright is only an incidental consideration. Unlike CC0, the licenses impose some conditions on reuse.

The licenses

The broadest license is the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which requires only that the user provide attribution as directed by the licensor. This license is used by open access publishers, including PLOS, by creators of open educational resources, such as OpenStax College and Rice Connexions, and by a range of other creators. All of the other licenses keep the attribution requirement and add other conditions. One of these is the “Share Alike” requirement, which provides that anyone who adapts the licensed work must license the adaptation under the same license as the source work. This requirement is a close cousin to certain “copyleft” licenses used for software, such as the GNU General Public License (GNU’s Not Unix!). Wikipedia uses this Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) license, and only materials licensed under CC BY or CC BY-SA can be uploaded to Wikimedia Commons.

The Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial (CC BY-NC) license limits licensed uses to noncommercial uses. Last, one may permit only copy-paste reuse and not license the creation of derivative works by using the Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs license (CC BY-ND). The final two licenses combine the noncommercial condition with either the Share Alike or the No Derivatives condition ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ). This may seem like more complexity than it is worth, and some critics of Creative Commons take this position, but a quick look at the uses of these licenses on Flickr demonstrates that creators appear to want this full choice set to share their works ( https://www.flickr.com/creativecommons/ ).

Alternatively, one can grant the public permission to use copyrights associated with a dataset or database through a license. For example, a researcher may post to the web a complex dataset that has an original database model. Users who copy the dataset merely to extract the uncopyrightable data elements would not need permission to do so in much of the world. However, if one were to republish the full dataset, one would be using the copyright layer in a manner that likely would require a license. The researcher publishing the dataset may simply want to require that any republication be done with proper attribution. The researcher could write a bespoke license to require this or could use a standard copyright license, such as the CC BY license. The organization publishes an FAQ on the relation of its licenses to databases on its website [ 16 ].

- 1. EBI Terms of Use of the EBI Services. EMBL-EBI. 2015. http://www.ebi.ac.uk/about/terms-of-use .

- 2. World Intellectual Property Organization, Summary on Existing Legislation Concerning Intellectual Property in Non-Original Databases. 13 Sep 2002; SCCR/8/3. http://www.wipo.int/meetings/en/doc_details.jsp?doc_id=2296 .

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 4. The University-Industry Demonstration Partnership. Researcher Guidebook: A Guide for Successful Institutional-Industrial Collaborations. Institutional Researcher. 2012; 6:28. https://www.uidp.org/publication/researcher-guidebook-and-quick-guide/

- PubMed/NCBI

- 7. Rood J. Who Owns CRISPR? The Scientist. 3 Apr 2015. http://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/42595/title/Who-Owns-CRISPR-/ . Accessed 3 July 2015.

- 8. The Intellectual Property Office. Exceptions to Copyright: Research. Copyright. 2014; 6:10. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/375954/Research.pdf .

- 10. Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber) of 9 November 2004. The British Horseracing Board Ltd and Others v William Hill Organization Ltd. Case 203/02. Official Journal of the European Union. 1 August 2005. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1435941427227&uri=CELEX:62002CJ0203 .

- 11. Judgment of the Court (Second Chamber) of 15 January 2015. Ryanair Ltd v PR Aviation BV. Case C-30/14. Official Journal of the European Union. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:62014CJ0030&qid=1435940638722 .

- 12. MIT Policies and Procedures. Information Policies: Invention and Proprietary Information Agreements. 13.1.4. http://web.mit.edu/policies/13/13.1.html .

- 13. United States Code, title 17, § 201(b). http://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap2.html

- 15. CoStar Realty Info., Inc. v. Field, 612 F. Supp.2d 660, 669 (D. Md. 2009). http://www.mdd.uscourts.gov/Opinions/Opinions/CoStar-08-663-MTDOpinion.pdf

- 16. Creative Commons: Data, https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/Data .

Ten Common Questions About Intellectual Property and Human Rights

Georgia State University Law Review, Vol. 23, 2007, pp. 709-53

Michigan State University Legal Studies Research Paper No. 04-27

46 Pages Posted: 9 Apr 2007 Last revised: 14 Feb 2014

Peter K. Yu

Texas A&M University School of Law