- One email, all the Golden State news

- Get the news that matters to all Californians. Start every week informed.

- Newsletters

Environment

- 2024 Voter Guide

- Digital Democracy

- Daily Newsletter

- Data & Trackers

- California Divide

- CalMatters for Learning

- College Journalism Network

- What’s Working

- Youth Journalism

- Manage donation

- News and Awards

- Sponsorship

- Inside the Newsroom

- CalMatters en Español

California’s wildfire smoke and climate change: 4 things to know

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

California wildfires every year emit as much carbon as almost 2 million cars, posing a threat to efforts to battle climate change.

Wildfires and climate change are locked in a vicious circle: Fires worsen climate change, and climate change worsens fires.

Scientists, including those at the World Resources Institute , have been increasingly sounding the alarm about this feedback loop, warning that fires don’t burn in isolation — they produce greenhouse gases that, in turn, create warmer and drier conditions that ignite more frequent and intense fires.

Last week, wildfire smoke prompted another round of unhealthy air quality in California. Fires in Oregon and Northern California sent smoke into Sacramento and the San Francisco Bay Area. And it’s a global nightmare: This summer, world temperatures hit an all-time high , the worst U.S. wildfire in more than a century devastated Maui, a deadly fire in Greece was declared Europe’s largest ever, and swaths of the Midwest and Northeast have been blanketed by smoke from Canada’s forest fires.

As California’s most intense wildfire months approach, the volume of greenhouse gases they emit is expected to grow.

A bill by Assemblymember Bill Essayli , a Republican from Riverside, introduced this year would have required the state to count wildfire emissions in its efforts to reduce statewide greenhouse gases. But the bill didn’t get far: It was defeated in committee.

Here are answers to some of the key questions raised by the symbiotic relationship between wildfires and climate change:

What’s happening to carbon emissions as wildfires worsen?

Scientists around the world are trying to quantify just how much wildfires contribute to climate change.

Last year, California wildfires sent an estimated 9 million metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, according to California Air Resources Board estimates . That’s equivalent to the emissions of about 1.9 million cars in a year.

In 2020, California’s wildfires were its second-largest source of greenhouse gases, after transportation, according to a study published last year . The researchers from UCLA and the University of Chicago concluded that the 2020 wildfires increased overall emissions by about 30%.

When forests burn, carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases are released into the air. It’s considered part of a natural cycle, with plants absorbing and then releasing the chemicals into the air over time. But experts say the increasing frequency of fires might be throwing this cycle out of balance .

Emissions this year from Canada’s forests have shattered records, according to the European Union’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service. Last year, carbon dioxide from boreal forests — the world’s northernmost forests, which span vast swaths of Canada and Alaska — hit a record high, UC Irvine researchers reported in the journal Science .

“Where does that carbon go? It goes up into the atmosphere, it circles all around the globe, it’s affecting all of us.” Char Miller, Pomona College

Fires in these northern latitudes are of deep concern to researchers, as those forests historically were too cold to experience significant burns. They are incredibly dense, and emit methane from the permafrost that lies beneath them.

“These are forests that haven’t burned, not just in decades but probably centuries,” said Char Miller, an environmental professor at Pomona College in Claremont. “Where does that carbon go? It goes up into the atmosphere, it circles all around the globe, it’s affecting all of us. It’s both symbolic and I think really significant. The coldest part of the planet is also exploding in fire.”

In addition, wildfires emit methane, which is a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, according to a study published earlier this summer .

Will wildfire smoke derail the state’s climate goals?

Researchers are increasingly calling attention to how forest fires might be eroding the state’s climate goals , with UCLA scientists describing the state’s efforts as “up in smoke.”

Michael Jerrett, a professor at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, said nearly two decades worth of emission reductions from power plants were threatened by the 2020 fires, which included some of California’s largest and most destructive fires .

“Essentially, the positive impact of all that hard work over almost two decades is at risk of being swept aside by the smoke produced in a single year of record-breaking wildfires,” Jerrett said in a statement.

Some experts say carbon emissions from wildfires are not much of a concern — that the carbon captured by trees, brush and grasses already existed in the atmosphere so its release during fires is part of a natural cycle. As a result, they say, those emissions shouldn’t be considered net contributors to climate change.

“These are distractions from the real issue which is that we need to generate a lot more renewable energy to displace our use of fossil fuels,” Anthony Wexler, director of the Air Quality Research Center at UC Davis, wrote to CalMatters in an email.

On the other hand, some experts say carbon is carbon — and that it all contributes to climate change. Jerrett and the other authors of the UCLA report said wildfire emissions should be a bigger part of California’s climate policy.

For its part, the California Air Resources Board estimates emissions from wildfires, but it doesn’t count them against greenhouse gas targets for 2030. The targets are based only on gases produced by industries, energy, transportation and other human sources .

Last year, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed into law a requirement that the state achieve net-zero emissions as quickly as possible, no later than 2045. That mandate means the state will have to ultimately consider the roles of natural and working lands, said David Clegern, an air board spokesman. However, some wildfires are “part of the natural cycle and should not count against targets,” Clegern wrote in an email.

Clegern said “it’s difficult to know” how much carbon from wildfires “might reduce the effectiveness of the state’s climate programs.”

“That’s because to a certain extent wildfire smoke is part of a natural carbon cycle…We cannot yet draw a bright line to accurately measure that impact,” he said.

Instead, he said scaling back fossil fuels has to be California’s priority.

“California is working on reducing wildfire in an all-hands-on-deck manner, but we won’t really fix the problem until we quit pumping more fossil fuel emissions into the atmosphere,” Clegern said.

How does the state plan to deal with carbon from fires?

State officials say restoring the health of forests and taking steps to make sure they are more resilient to fires will result in fewer wildfires and fewer climate-changing emissions.

Air board models project that natural and working lands — forests, rangelands, urban green spaces, wetlands and farms — will be a net source of emissions through 2045, while at the same time these lands will experience a decrease in the trees, shrubbery, soil and other natural features that naturally sequester carbon.

That’s why the proper management of these undeveloped lands will be important in the coming two decades. More than half of California’s forestland is managed by the federal government, and the Newsom administration announced in 2021 that it was working with the Biden administration to better manage forests and build fire resilience.

“These lands can be part of the climate solution, but we need to increase our efforts to reduce their emissions and improve their ability to store carbon into the future,” Clegern said.

Burning forests might be complicating the state’s climate goals in other ways, too. California’s carbon offset market has been threatened by out-of-state wildfires, the online publication Grist reported, because the state awards credits to companies that maintain forests elsewhere to store carbon.

What about the impact on smog and soot?

Wildfire smoke is toxic, containing substances such as carbon monoxide and benzene, a carcinogen. Smoke’s tiny particles of soot are considered its most hazardous ingredient, since they can enter airways, lodge in lungs and trigger asthma or heart attacks. Local air quality districts regularly send out warnings in California when wildfires spread smoke, sometimes hundreds of miles from the fires.

Smoke may be negating some of California’s hard-fought clean-air gains . A report last year by the Energy Policy Institute of Chicago found that some California counties were more polluted than they were in 1970. In 2020, more than half of California counties experienced their worst air pollution since 1998, according to the report.

California’s air quality agencies do not have to consider wildfire smoke when they outline plans to attain health standards for air pollutants, such as fine particles and ozone. That’s because fires are considered “exceptional events” under the federal Clean Air Act.

“Even though the frequency of wildfires is increasing, we have no reason to believe that (U.S.) EPA will change how wildfire emissions are treated under the exceptional events process,” Clegern said.

Meanwhile, concern about the impact of smoke on communities is growing. Nitrogen oxides, which form smog, appear to be increasing in rural areas — largely due to wildfires, according to a recent UC Davis study .

“If you go to these remote forests — which are predominantly in the north and the Sierras in the south — what you find is that there’s this large increase,” said study co-author Ian Faloona , a UC Davis bio-micro-meteorologist.

more on air pollution

Track California Fires 2024

Explore this map of active wildfires across California — also featuring a history of state wildfires and their toll in acreage, property and lives.

Welcome to the Age of Fire: California wildfires explained

In California, wildfire season is nearly year-round. CALmatters explores why, and what could help fireproof the state.

We want to hear from you

Want to submit a guest commentary or reaction to an article we wrote? You can find our submission guidelines here . Please contact CalMatters with any commentary questions: [email protected]

Alejandro Lazo Climate Reporter

Alejandro Lazo writes about the impacts of climate change and air pollution and California’s policies to tackle them. He’s written about the state's groundbreaking electric vehicle mandate, the oil... More by Alejandro Lazo

Implications of the California Wildfires for Health, Communities, and Preparedness: Proceedings of a Workshop (2020)

Chapter: 1 introduction and overview, 1 introduction and overview.

California and other wildfire-prone western states have experienced a substantial increase in the number and intensity of wildfires in recent years. Eight of the 10 largest wildfires in California have occurred since 2000. In November 2018 the Camp Fire in northern California killed at least 85 people and destroyed more than 18,000 structures, becoming California’s deadliest and most destructive wildfire on record (see Figure 1-1 ). Wildlands and climate experts expect these trends to continue and quite likely to worsen in coming years.

Wildfires and other disasters can be particularly devastating for vulnerable communities ( Fothergill et al., 1999 ). Members of these communities tend to experience worse health outcomes from disasters, have fewer resources for responding and rebuilding, and receive less assistance from state, local, and federal agencies. Because burning wood releases particulate matter and other toxicants, the health effects of wildfires extend well beyond burns. In addition, deposition of toxicants in soil and water can result in chronic as well as acute exposures. Vulnerable communities tend to have fewer resources with which to prepare for and respond to environmental disasters such as a wildfire. Even relatively small expenses, such as tree trimming, brush removal, or other fire prevention services, may be beyond the financial means of community members.

On June 4–5, 2019, four different entities within the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine—the Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Disasters and Emergencies; the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement; the Roundtable on the Promotion of Health Equity; and the Roundtable on Environmental Health

Services, Research, and Medicine—held a workshop titled Implications of the California Wildfires for Health, Communities, and Preparedness at the Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing at the University of California (UC), Davis. The Statement of Task can be found in Appendix A . For reference, see Figure 1-2 for a map of California counties and major cities. As Kenneth Kizer, distinguished professor in the UC Davis School of Medicine and the Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing and chair of the planning committee for the workshop, said in his welcoming remarks, a major challenge facing the planning committee was the amount of material that could be presented at the workshop. 1 “One of the underlying premises of this workshop is that the nature of the wildfires that we have seen in the last few years is the ‘new normal,’ both in the frequency and number

___________________

1 The planning committee for the workshop was Kenneth Kizer ( Chair ), Julie Baldwin, Michelle Bell, Wayne Cascio, David Eisenman, Richard Jackson, Wayne Jonas, Suzet McKinney, and Winston Wong. Support for the workshop came from The California Endowment, the California Wellness Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the sponsors of the National Academies’ roundtables and forums.

of different locations and in the intensity of fires, and that what we have seen is going to be repeated in the future,” said Kizer, who worked as a firefighter during college. Many communities and populations are at risk and want to know what they can do to prevent and prepare for wildfires, “because what we have seen in the past few years is going to be what we see going forward.”

Wildfires are creating a new model of a public health crisis, added David Lubarsky, vice chancellor of human health sciences at UC Davis and chief executive officer of UC Davis Health. Wildfires are intensive and unplanned long-term events that pose complex and wide-ranging problems. Population growth, climate change, weather extremes, intermittent droughts, record rains, and other factors are interacting in ways that are difficult to dissect, understand, and ameliorate. Earthquakes, mudslides, urban unrest, and other issues are usually here and then gone, said Lubarsky. In contrast, large wildfires can go on for long periods of time and have wide-ranging and long-lasting impacts across large areas.

The issues posed by wildfires have caught the attention of academic health systems around the nation, Lubarsky noted. For example, he had recently written an editorial about air quality in Sacramento following the Camp Fire, which for 5 days was the worst in the world. “I was shocked, because I have been to Shanghai and Beijing on bad days,” he said. “This beat all of them.”

Figuring out how to help people in an acute time frame and then helping to deal with the social devastation, health care interruptions, and health care impacts over the long term are both challenges, Lubarsky said. For example, UC Davis had recently partnered with a hospital in Chico to open a chemotherapy infusion center to give people easier access to chemotherapy following the damage done by the Camp Fire to the Adventist Feather River Hospital in Paradise. “That is one of those things you do not think about. What do you do with people who have chronic illnesses who are dependent on the services that were previously provided in a scarred area?”

Both Lubarsky and Deborah Ward, Dignity Health Dean’s Chair for Nursing Leadership and clinical professor at the Betty Irene Moore School of Medicine, who also spoke during the opening session, observed that UC Davis was a leader in the response to the Camp Fire. Students at the School of Nursing and elsewhere immediately stepped up to respond to the unfolding disaster occurring in and around Paradise, Ward said. They collected and delivered goods and supplies and worked at shelter clinics, in part to care for frail, elderly evacuees. They spent countless hours providing urgently needed care to victims of the fire. They encountered amazing and disturbing episodes, according to Ward. “One of our nursing students, Brandon, suddenly found himself caring for people whose feet were burned as they had raced from their homes trying to escape the fire.” As one nursing student observed to Ward, “This is a good reminder of why we want to be health care providers. This is about serving our community and meeting its needs.”

Lubarsky pointed out that UC Davis researchers have been investigating the impact of environmental toxins on populations, including the effects of wildfire smoke. “Figuring out how we are going to actually make a dif-

ference in the trajectory of the people and our environment that has been impacted by the fires is incredibly important for northern California,” he said.

A highlight of the workshop was the public debut of a documentary titled Waking Up to Wildfires produced by the UC Davis Environmental Health Sciences Center and funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. 2

ORGANIZATION OF THE WORKSHOP

This summary of the workshop largely parallels the workshop agenda (see Appendix B ). Chapter 2 provides an overview of wildfires in California and also looks at a particular wildfire in southwestern Colorado. Climate change is contributing to an intensification of wildfires in the western United States, these speakers said, which is requiring a greater breadth and depth of potential responses. Considerations of health equity are a critical aspect of these responses and can help all communities and populations become more resilient to future wildfires.

Chapter 3 discusses the populations impacted by wildfires, especially the vulnerable populations and communities that experience disproportionate impacts from natural disasters. As speakers in this panel pointed out, these communities also have experiences and traditional knowledge that can reduce not only their own vulnerability but that of other groups.

Chapter 4 examines the wide-ranging health effects of wildfires, including effects on the respiratory system, cardiovascular system, and immune system. Some of these effects are acute and others chronic, pointing to the need to begin research quickly after a wildfire event. Doing such research requires good measures of both exposures and health effects, and each measure has its own challenges. New technologies could help in both areas.

Chapter 5 looks at the recovery process, reversing the usual order of discussing preparedness first, response second, and recovery third. Coordination at all levels of government and among sectors is a theme of long-term recovery processes, given that much of the burden for recovery typically falls on states and local communities. In addition, communities have distinct resources, such as nearby academic institutions, that can help them recover from wildfires in ways that are particularly suited to local situations.

Chapter 6 considers how to enhance operational response to wildfires. The responses to wildfires can be wide ranging and involve a variety of public- and private-sector institutions. Leveraging the expertise of these

2 The trailer for the film, which features several people who spoke at the workshop, is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v24296K-qVE (accessed November 25, 2019).

organizations and coordinating activities can increase the effectiveness of responses and reduce both the physical and the mental health effects of wildfires.

Chapter 7 turns to the potential for mitigation and preparedness. These activities are also wide ranging and have long time frames and extensive planning requirements. Yet, they shape the response and recovery actions that take place on short- and medium-term time frames. The zoning, design, construction, and maintenance of structures, for instance, can have a critical influence on what happens during and after a wildfire.

Chapter 8 , the final chapter, closes the proceedings with the reflections of panel moderators and members of the roundtables and forum that organized the workshop on the themes that emerged and their implications for the future.

California and other wildfire-prone western states have experienced a substantial increase in the number and intensity of wildfires in recent years. Wildlands and climate experts expect these trends to continue and quite likely to worsen in coming years. Wildfires and other disasters can be particularly devastating for vulnerable communities. Members of these communities tend to experience worse health outcomes from disasters, have fewer resources for responding and rebuilding, and receive less assistance from state, local, and federal agencies. Because burning wood releases particulate matter and other toxicants, the health effects of wildfires extend well beyond burns. In addition, deposition of toxicants in soil and water can result in chronic as well as acute exposures.

On June 4-5, 2019, four different entities within the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine held a workshop titled Implications of the California Wildfires for Health, Communities, and Preparedness at the Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing at the University of California, Davis. The workshop explored the population health, environmental health, emergency preparedness, and health equity consequences of increasingly strong and numerous wildfires, particularly in California. This publication is a summary of the presentations and discussion of the workshop.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

- Original research

- Open access

- Published: 25 August 2021

Large California wildfires: 2020 fires in historical context

- Jon E. Keeley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4564-6521 1 , 2 &

- Alexandra D. Syphard 3

Fire Ecology volume 17 , Article number: 22 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

28k Accesses

77 Citations

33 Altmetric

Metrics details

California in the year 2020 experienced a record breaking number of large fires. Here, we place this and other recent years in a historical context by examining records of large fire events in the state back to 1860. Since drought is commonly associated with large fire events, we investigated the relationship of large fire events to droughts over this 160 years period.

This study shows that extreme fire events such as seen in 2020 are not unknown historically, and what stands out as distinctly new is the increased number of large fires (defined here as > 10,000 ha) in the last couple years, most prominently in 2020. Nevertheless, there have been other periods with even greater numbers of large fires, e.g., 1929 had the second greatest number of large fires. In fact, the 1920’s decade stands out as one with many large fires.

Conclusions

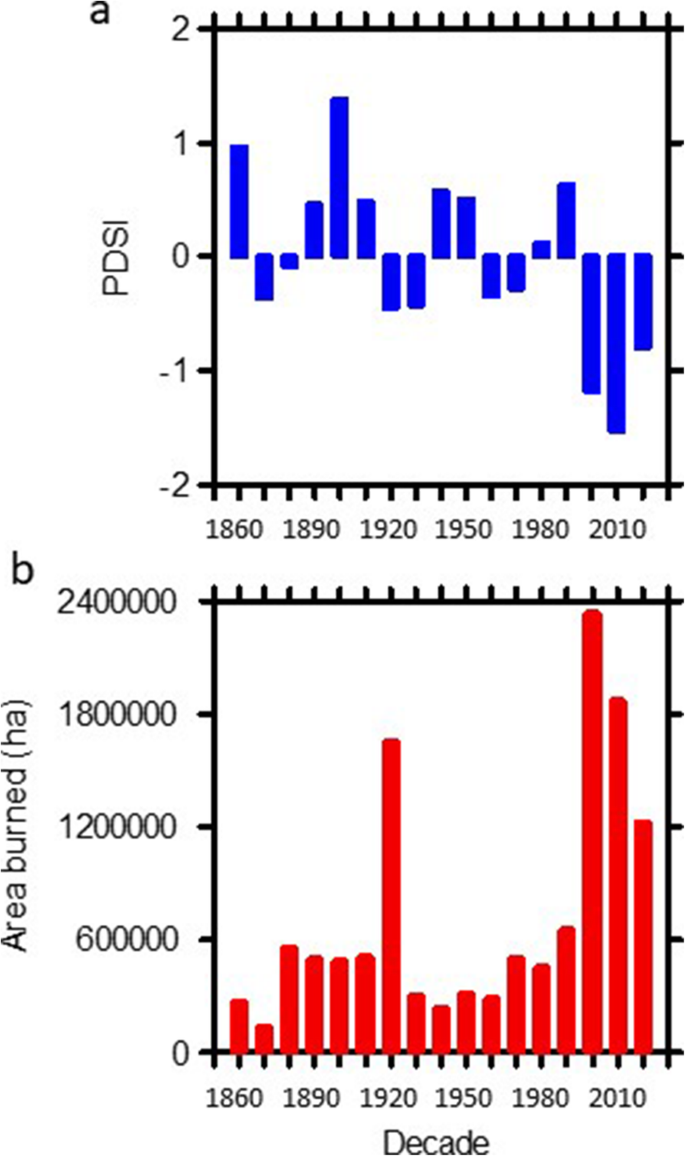

In the last decade, there have been several years with exceptionally large fires. Earlier records show fires of similar size in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Lengthy droughts, as measured by the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI), were associated with the peaks in large fires in both the 1920s and the early twenty-first century.

Antecedentes

En el año 2020, California experimentó un récord al quebrar el número de grandes incendios. Aquí situamos a éste y otros años en un contexto histórico mediante el examen de registros de incendios en el estado desde 1860. Dado que la sequía es frecuentemente asociada a grandes eventos de incendios, investigamos la relación entre grandes incendios y sequías en este período de 160 años.

Este estudio mostró que eventos extremos como el visto en 2020 no son históricamente desconocidos, y lo que se muestra como distintivamente nuevo es el incremento en el número de grandes incendios (definidos aquí como > 10.000 ha) en el último par de años, y más prominentemente en 2020. Sin embargo, ha habido otros períodos con aún mayores números de incendios (i.e. en 1929 hubo mayor número de incendios que en cualquier otro año del registro). De hecho, la década de 1920, fue una de las que presentó mayor número de grandes incendios.

Conclusiones

En la última década ha habido muchos años con incendios excepcionalmente grandes. Antiguos registros muestran incendios de tamaño similar tanto en el siglo 19 como en el siglo 20. Sequías prolongadas, medidas mediante el Índice de Sequías Severas de Palmer (PDSI), fueron asociadas con los picos de grandes incendios tanto en el siglo 20 como en el 21.

Introduction

The western US has a long history of large wildfires, and there is evidence that these were not uncommon on pre-EuroAmerican landscapes (Keane et al. 2008 ; Baker 2014 ; Lombardo et al. 2009 ). One of the biggest historical events was the 1910 “Big Blowup,” which reached epic proportions and was an important impetus for fire suppression policy (Diaz and Swetnam 2013 ). California in particular has had a history of massive wildfires such as the 100,000 ha 1889 Santiago Canyon Fire in Orange County or the similarly large 1932 Matilija Fire or 1970 Laguna Fire (Keeley and Zedler 2009 ).

While large fires are known in the historical record, in the first few decades of the twenty-first century, the pace of these events has greatly accelerated (Keeley and Syphard 2019 ). In the last decade, the state has experienced a substantial number of fires ranging from 10,000 ha to more than 100,000 ha, and these have caused massive losses of lives and property. The largest fires on record were recorded in 2018 and then were replaced with even larger fires in 2020, although some of these were the result of multiple fires that coalesced into fire complexes of massive size.

Causes for these fires are multiple, but climate change has been implicated as a critical factor (Williams et al. 2019 ; Abatzoglou et al. 2019 ). Historically, drought has often been invoked as a driver of large fires (Keeley and Zedler 2009 ; Diaz and Swetnam 2013 ), and California has experienced an unprecedented drought in the last decade (Robeson 2015 ). However, factors such as management impacts on forest structure and fuel accumulation, made worse by the recent drought, are critically important in some ecosystems (Stephens et al. 2018 ).

To put these recent fires in a historical context, we have investigated the history of large wildfires in California. “Large” fires is an arbitrary designation, e.g., Nagy et al. ( 2018 ) considered it to be 1000 ha or more. Our focus, however, is on those fires that made 2020 particularly noteworthy; so we define large fires as those in the top 1–2% of all fires, which is approximated by fires > 10,000 ha. In addition, we have examined the relationship of large fires to drought.

The database of fires > 10,000 ha was assembled from diverse sources. From 1950 to the present, the State of California Fire and Resource Assessment Program (FRAP) fire history database was relatively complete, but less so prior to 1950 (Syphard and Keeley 2016 ; Miller et al. 2021 ). In California, US Forest Service (USFS) annual reports provide statistics on fires by ignition source and area burned back to 1910 and Cal Fire back to 1919 (Keeley and Syphard 2017 ), and although these reports focused on annual summaries, they often provided descriptions of very large fires. A rich but under-utilized historical record for early years was the exhaustive compilation of fires in a diversity of documents from 1848 to 1937, assembled by a USFS project and brought to our attention by Cermak’s ( 2005 ) USFS report on Region 5 fire history. This source presents all documents (including agency reports and newspaper reports on fire, vegetation, timber harvesting and Native Americans) for all counties in the state and comprises 69 bound volumes (USDA Forest Service 1939-1941 ). We utilized these documents where they presented data on fire size, either an estimate of acres burned or dimensions of the burned area. We did not include fire reports that lacked a clear indication of area burned; e.g., the 1848 fire described in the region of Eldorado County referred to an immense plain on fire and all the hills blackened for an extensive distance (USDA Forest Service 1939-1941 ), but lacked more precise measures.

Other sources included the following: Barrett ( 1935 ), based on USFS records and personal experiences as well as “early-day diaries, historical works, magazines and newspapers.” Greenlee and Moldenke ( 1982 ) included fire records from state and federal agencies as well as library and museum archives. Morford ( 1984 ) was based on unpublished USFS records accumulated during the author’s 41 years in that agency. Keeley and Zedler ( 2009 ) was based on records retrieved from the California State Archives and State Library. Cal Fire ( 2020 ) data, not part of the FRAP database, included agency records of individual fire reports (not available to the public but searchable by the State Fire Marshall Kate Dobrinsky). In a few cases, the same fire was reported by more than one source, sometimes with different sizes; when this occurred after 1950, we used the FRAP data and before that either Cermak ( 2005 ) or Barrett ( 1935 ) over other sources.

Reliability of these data sources is an important question to address. Stephens ( 2005 ) contended that USFS data before 1940 were unreliable, an assertion based on Mitchell ( 1947 ); but Mitchell ( 1947 ) provided no evidence that early data were inaccurate, only that many states lacked early records. Mitchell ( 1947 ) was considering availability of state and federal data for the entire USA; however, California has far better historical records at both the state and federal archives than much of the USA (Keeley and Syphard 2017 ). USFS records for California were reported annually for all forests beginning in 1910 and for state protected lands by Cal Fire back to 1919. The latter agency had by 1920 several hundred fire wardens strategically placed throughout the state and each warden was held to a strict standard of reporting all fires in their jurisdiction.

Before 1910, data on fires was dependent on unpublished reports available in state and federal archives, observations published in books, data given in newspaper accounts of fire events, and estimates from fire-scar chronology studies. It was suggested by Goforth and Minnich ( 2007 ) that early newspaper reports were exaggerations and represented “yellow journalism,” a pejorative term that connoted unethical journalism. This was based on what they considered sensational headlines, but comparison of nineteenth century with more recent newspaper headlines provides no basis for this conclusion (Keeley and Zedler 2009 ). As a journalist colleague suggested, “a century-old newspaper story is not a precise source …[but] is the first draft of history and a valuable source of first person account from long past events.” Such information qualifies as scientific evidence, which is defined as evidence that serves to either support or counter a scientific theory or hypothesis, is empirical, and interpretable in accordance with scientific method. The data we present falls within these bounds and that includes newspaper reports as we used data on fire size in terms of acres or dimensions of burned landscape reported. Recently Howard et al. ( 2021 ) demonstrated that fire-scar records match newspaper accounts in the eastern US. To address the issue of how close newspaper accounts used in this study come to accurately depicting fire size, we have compared fires reported in published sources with newspapers where available. We of course appreciate that early accounts lacked the precise technology available today for outlining fire perimeters; however, this lack of precision does not necessarily translate into less accurate accounts and applies to both newspapers as well as state and federal agencies.

Data were presented for the state and by NOAA divisions North Coast (1), North Interior (2), Central Coast (4), Sierra Nevada (5), and South Coast (6). These are the five most fire-prone divisions of NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center categories, defined as climatically homogenous areas (Guttman and Quayle 1996 ). There of course are other systems that may be useful for comparisons, dependent on the need. For example, the Bailey Ecoregions (Bailey 1980 ), which separates regions by vegetation type, might be thought preferable, but, for our purposes, there is no necessary advantage as large fires usually burn across a mosaic of different vegetation types. A system that might provide a better presentation would be the recently described Fire Regime Ecoregions (Syphard and Keeley 2020 ). However, despite limitations to the NOAA divisions (e.g., Vose et al. 2014 ), it is preferable due to the availability of historical annual data on the Palmer Drought Severity index calculated by NOAA divisions.

Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) was recorded for each year from two sources. From 1895 to 2020, PDSI was the annual mean from NOAA ( 2020a ), and for years prior to 1895, summer PDSI was reconstructed from tree-ring studies (Cook et al. 1999 ). Statistical analysis and graphical presentation were conducted with Systat software (ver. 13.0, Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, http://www.systat.com/ ).

Since some of the fires came from data reported in newspapers, not a typical scientific data base, we did an initial investigation comparing FRAP reported fire size with size reported in newspaper reports. This was not an exhaustive study since FRAP data before 1950 presents relatively few fires by date or fire name making it difficult to match up fires with newspaper reports; however, we found half a dozen potential comparisons (Table 1 ). As to be expected these different reports are not identical in fire size, however, they were quite similar; sometimes, newspapers over reported area burn but other times under reported, although most importantly, they were of similar magnitude as those in the FRAP database. Data sources varied over time (Table 2 ); from 1950 to the present, large fires were all recorded in the FRAP database. Prior to that year, sources were mostly from USFS ( 1939-1941 ).

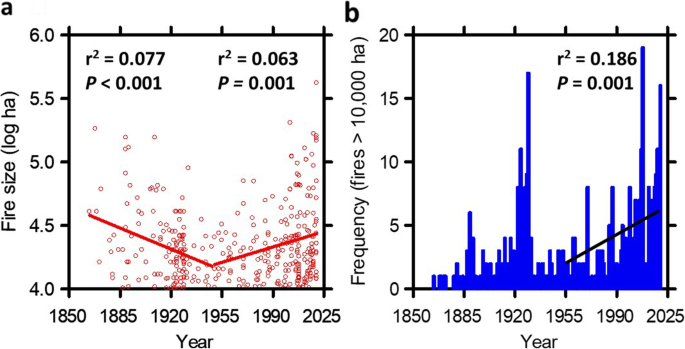

Fire size of all fires over 10,000 ha during the last 160 years are shown in Fig. 1 a. Exceptionally large fires followed a bimodal pattern with peaks in the nineteenth century and again in the twenty-first century, separated by a low point in the 1950s. From 1860 to 1950, there was a significant decrease in large fire size followed by a significant increase in the second half of the record. Although the trends were highly significant, the great year to year variation in size of large fires, gave low r 2 values, indicating limited ability to predict fire size for any given year.

a Fire size for large fires from 1860 to 2020. b Frequency of large fires over this same time period

To illustrate the temporal distribution of record-breaking fires, we picked the top 3% ( n = 12) of all fires based on size, and these are shown in (Table 3 ). Not surprisingly, 5 occurred in the year 2020; however, four occurred in the nineteenth century.

The data presented in this paper greatly expands our understanding of the history of large fires in California. To date, our dependence has been on the FRAP database and they clearly acknowledge their records are for fires from 1950 to the present, and this is borne out by our analysis (Table 2 ), but the records presented here extend the fire history back nearly a century. Over the period from 1860 to the present, yearly frequency of fires over 10,000 ha exhibited several prominent peaks (Fig. 1 b). A few peak years occurred in the 1920s, with one of the highest frequencies recorded throughout the entire 160 year record in 1929. There were also peaks in 2007 and 2008 and again in 2018 and 2020.

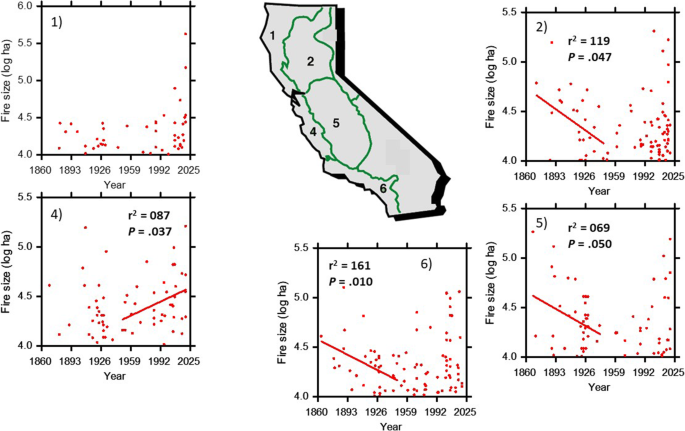

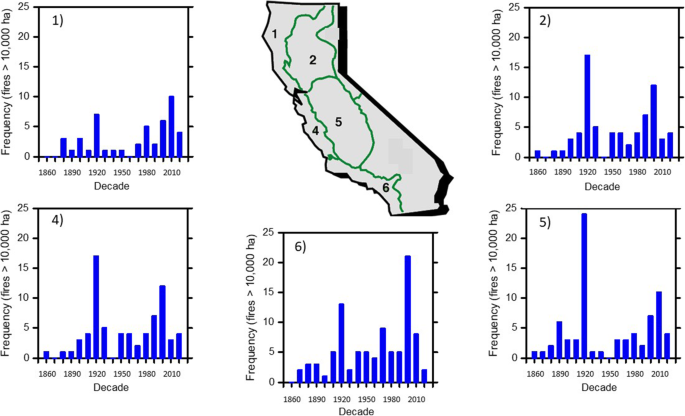

Through time, the distribution of fire size varied between NOAA divisions (Fig. 2 ). The North Interior (2), Sierra Nevada (5), and South Coast (6) divisions all exhibited a significant decline in fire size from the nineteenth century till 1950. Although all the regions exhibited the largest fires in the last decade, only in the Central Coast (4) was this significant for the years 1950–2020.

Large fires within NOAA Divisions. Statistics are presented for significant trends

Frequency of fires over 10,000 ha are presented by decade for each of the five divisions (Fig. 3 ). Consistent with the statewide pattern (Fig. 1 b), all showed a spike in number of large fires in the 1920s and again after 2000. The 1920s peak was particularly prominent in the Sierra Nevada (5) and South Coast. Also, for the Central Coast and Central Sierra Nevada regions, the number of fires in the 1920s was higher than that for recent years. For the years 1860 to 1949 and for the years 1950 to 2020 separately, there was no significant change in frequency over time.

Decadal frequency of large fires within NOAA Divisions. Note the decade 2020 is represented by a single year.

One aspect of climate over the entire period is captured by the PDSI, a drought index that includes patterns of both precipitation and temperature. There have been several periods of drought over the past 160 years, the most severe being in the decades 1920-1930 and 1990-2020 (Fig. 4 a). These periods also correlate with periods of large amounts of area burned by large fires (Fig. 4 b). Bivariate regression analysis showed that over the period from 1860 to 2020, there was a significant relationship between PDSI and area burned (adj r 2 = 0.429, P = 0.003).

a PDSI for the decades from 1860 to 2020. b Area burned by fires > 10,000 ha for the decades from 1860 to 2020. Note the decade 2020 is represented by a single year

Clearly, 2020 was a phenomenal fire year in California for record breaking large fires. However, this study shows that such extreme fire events are not unknown historically, and what stands out as distinctly new is the increased number of large fires (defined here as > 10,000 ha) in the last couple of years, most prominently in 2020. Given that historically we have seen years with even greater number of large fire events, e.g., 1929, a comprehensive evaluation of the factors leading up to large fire event years is clearly needed.

The largest fire in recorded history for the state is the 2020 August Complex Fire, which comprised 38 separate fires that were considered a single a massive 418,000 ha fire (Cal Fire 2020 ). Thus, the merging of these multiple fires into a larger event is certainly a factor affecting “fire” size. Indeed, some 2020 fire complexes included multiple fires that never actually merged; for example, the LNU Complex Fire, which ranked within the top 12 fires (Table 3 ), actually comprised several distinctly separate fires that apparently did not merge (San Francisco Chronicle 2020 ).

It has been contended that large fires in the past were often very different in nature from contemporary large fires. For example, many southwestern US mixed conifer forest large fire events in the nineteenth century were low-intensity surface fires, unlike contemporary large fires that are dominated by high-intensity crown fire (Keane et al. 2008 ). This contention, however, varies from descriptions of the top 12 fires recorded here (Table 3 ). For example, when describing the 1889 Plumas fire, newspaper reports state “A large amount of timber and fire wood [were] destroyed.” One report describes the 1891 Eldorado fire as “the most terrible forest fire ever experienced in California…fanned by a strong north wind has swept over almost the entire stretch of country between Georgetown and Salmon Falls…Magnificent forests of a few days ago have been burned over and blackened and lofty pines seared and killed. The scene at night baffles all powers of description, there being a moving mass of fire as far as the eye can reach.” The 1909 Santa Cruz fire was described as “this large conflagration spread… [and] the country is entirely burned over; the entire growth on Loma Prieta Peak and its sides down to Los Gatos Creek is a charred area.”

In general, very few of the large fires reported in (USDA Forest Service 1939-1941 ) were described as low-intensity surface fires. This source described forest fires up and down the state as high intensity conflagrations. For instance, in San Diego County, the 19,000 ha fire of 1870 was described as “the fires which have been raging in the mountains …are wholly unprecedented in extent and …destruction of timber”; in the San Luis Obispo 1869 40,000 ha fire “a great deal of timber and grass has been destroyed”; in Calavaras County in 1889, an 81,000 ha fire was described “A large forest fire has been raging…a large scope of timber country has been laid in waste”; a description of the Tehama 1889 30,000 ha fire was “The forest fire that has raged...was very destructive”, etc. In short, there is little in these records to suggest that nineteenth century large fires were normally less destructive of natural resources than twenty-first century fires. This of course is not meant to negate the commonly accepted paradigm that California forests in the past frequently burned with low-intensity surface fires (Skinner and Chang 1996 ), but that once fires reached epic proportions, and consequently burned through a mosaic of vegetation types, fire behavior appears to have been quite different.

However, one thing that is different between historical large fires and recent ones is that contemporary large fire events are often much more destructive in terms of loss of lives and property. For example, the 2018 Butte County Camp Fire driven by extreme foehn winds killed 85 people and destroyed over 18,000 buildings, however, a similar foehn wind driven fire occurred in Eldorado County in 1891 (Table 3 ), and there were no reports of fatalities and relatively few structures were lost (USFS 1939-1941 ). The difference is due to changes in human demography, e.g., California population throughout the nineteenth century was fewer than 2 million people in contrast to 2020 with a population approaching 40 million. Pressure to find affordable housing has resulted in urban sprawl into watersheds of dangerous fuels (Syphard et al. 2007 , 2019 ). In addition, population growth has played a role in increasing ignitions as most fires that result in human losses are of human origin (Keeley and Syphard 2018 ).

Another factor that is very different in recent decades, when compared to the middle of the century, is the frequency of large fires, with 2007, 2008, 2017, 2018, and 2020 all being peak years for number of large fire events. However, the 1920s were comparable to these recent decades, and in fact, 1929 was a peak year for frequency of large fire events (Fig. 1 b). The1920s decade was also a peak in most regions (Fig. 3 ). Although there was less structure loss in the 1920s, demographic changes could have been involved in terms of frequency of large fires, as the 1920s saw a major influx of people. In this decade, there were increased anthropogenic ignitions driven by greater access to wildlands due to rapid road construction and an order of magnitude increase in car licenses (Keeley and Fotheringham 2001 ).

Climate is widely viewed as a determining factor in fire size, and in particular, drought has been a major driver historically (Little et al. 2016 ; Madadgar et al. 2020 ; Huang et al. 2020 ). One of the important factors behind the 2020 fire events was the anomalously long and intense drought the region experienced beginning in 2012. This drought was experienced across the southern US (Rippey 2015 ) and lasted 3–5 years in California; it was considered to be one of the most severe droughts in California history (Robeson 2015 ; Jacobsen and Pratt 2018 ). The greatest number of recent large fires and size of these fires have been concentrated in the years since this drought (Fig. 4 ). Drought has also been implicated as a factor in other large California fires during the first decade of the twenty-first century (Keeley and Zedler 2009 ) as well as with large fire events in the 1920s, as shown in this study.

While a clear climate signal in terms of drought is a likely driver of big fire events in the state, an emerging issue is the role of anthropogenic climate change (Williams et al. 2019 ). While droughts have historically been a natural occurrence in California’s Mediterranean climate ecosystems, it has been postulated that global warming has made these droughts more severe. Estimates are that the 2012–2014 drought in the Sierra Nevada was perhaps 10–15% more severe due to global warming (Williams et al. 2015 ). This has important implications for the impact of drought on tree and shrub dieback that increases hazardous fuels and contributes to increased fire risk (Stephens et al. 2018 ). However, the relationship between drought and tree dieback in the state is complicated and impacted by competition and other factors (Das et al. 2011 ; Young et al. 2017 ).

The severity of the 2020 fire season in California is not the result of any one factor such as climate change but the result of the “perfect storm” of events. Winter and spring precipitation in the northern part of the state was only about 50% of average, August had a stream of dry lightning storms in northern California that ignited over 5000 fires (Cal Fire 2020 ), there was an intense heat wave in early September that elevated temperatures to record breaking levels (NOAA 2020b ), and forests in the northern half of the state had anomalous fuel loads due to a century of fire suppression and greatly exacerbated by the intense drought of 2012–2015 (Stephens et al. 2018 ).

It is a major challenge to parse out the role of anthropogenic climate change in driving 2020 fires. Certainly, the below normal rainfall year in the north fell within the natural range of variation. The extraordinary lighting storm was perhaps more severe than what is seen in most years, but was not at all unprecedented; e.g., in 2008 northern California experienced a similar event with over 6000 lightning strikes and burning over 400,000 ha from these fires alone, and this is a common phenomenon at a decadal scale, e.g., 1999, 1987, 1977, 1955 (Cal Fire 2008 ). Further contributing to the 2020 fires was the intense heat wave that may be linked to climate change (Gershunov and Guirguis 2012 ; Hully et al. 2020 ). The role of anomalous fuel accumulation due to more than a century of fire suppression and made much worse by 2012–2016 drought was also a major contributor to the size of these fires.

Historically, California fires as big as some of the largest fires in 2020 year have occurred as evident from records beginning in 1860. However, without question, 2020 was an extraordinary year for fires in California. This was driven by a multitude of factors but prominently is the extraordinary droughts the state has experienced in the last couple decades. Peaks in the number of large fires have occurred in the 1920s as well as in the twenty-first century and both occurred in decades with extended droughts.

Availability of data and materials

Data from published sources listed in the “Methods” section.

Abbreviations

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection

Cal Fire’s Fire and Resource Assessment Program

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Palmer Drought Severity Index

Abatzoglou, J.T., A.P. Williams, and R. Barbero. 2019. Global emergence of anthropogenic climate change in fire weather indices. Geophysical Research Letters 46 (1): 326–336. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL080959 .

Article Google Scholar

Bailey, R.G. 1980. Description of the ecoregions of the United States. Misc. Publication 1931 . Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Google Scholar

Baker, W.L. 2014. Historical forest structure and fire in Sierran mixed-conifer forests reconstructed from General Land Office survey data. Ecosphere 5 (7): 79.

Barrett, L.A. 1935. A record of forest and field fires in California from the days of the early explorers to the creation of the forest reserves . San Francisco: USDA Forest Service.

Cal Fire. 2008. June 2008 California Fire Siege Summary Report . Sacramento: Cal Fire.

Cal Fire. 2020. Fire incidents. https://www.fire.ca.gov/incidents/

Cermak, R.W. 2005. Fire in the forest: a history of forest fire control on the national forests in California, 1898-1956 . Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office.

Cook, E.R., D.M. Meko, D.W. Stahle, and M.K. Cleaveland. 1999. Drought reconstructions for the continental United States. Journal of Climate 12: 1145–1162 ftp://ftp.ncdc.noaa.gov/pub/data/paleo/drought/NAmericanDroughtAtlas.v2/ .

Das, A.J., J. Battles, N.L. Stephenson, and P.J. van Mantgem. 2011. The contribution of competition to tree mortality in old-growth coniferous forests. Forest Ecology and Management 261 (7): 1203–1213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2010.12.035 .

Diaz, H.F., and T.W. Swetnam. 2013. The wildfires of 1910. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 94 (9): 1361–1370. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00150.1 .

Gershunov, A., and K. Guirguis. 2012. California heat waves in the present and future. Geophysical Research Letters 39: L18710.

Goforth, B.S., and R.A. Minnich. 2007. Evidence, exaggeration, and error in historical accounts of chaparral wildfires in California. Ecological Applications 17 (3): 779–790. https://doi.org/10.1890/06-0831 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Greenlee, J. M. and A. Moldenke. 1982. History of wildland fires in the Gabilan Mountains region of central coastal California. Unpublished report under contract with the National Park Service.

Guttman, N.B., and R.G. Quayle. 1996. A historical perspective of U.S. climate divisions. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 77 (2): 293–303. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477/WF13115 .

Howard, L.F., G.D. Cahalan, K. Ehleben, B.A. Muhammad El, H. Halza, and S. DeLeon. 2021. Fire history and dendroecology of Catoctin Mountain, Maryland, USA, with newspaper corroboration. Fire Ecology 17 (1): 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-021-00096-2 .

Huang, Y., Y. Jin, M.W. Schwartz, and J.H. Thorne. 2020. Intensified burn severity in California’s northern coastal mountains by drier climatic condition. Environmental Research Letters 15 (10): 104033. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aba6af .

Hully, G.C., B. Dousset, and B.H. Karn. 2020. Rising trends in heatwave metrics across southern California. Earth’s Future 8: e2020EF001480.

Jacobsen, A.L., and R.B. Pratt. 2018. Extensive drought-associated plant mortality as an agent of type-conversion in chaparral shrublands. New Phytologist 219 (2): 498–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15186 .

Keane, R.E., J.K. Agee, P. Fule, J.E. Keeley, C. Key, S.G. Kitchen, R. Miller, and L.A. Schulte. 2008. Ecological effects of large fires on US landscapes: benefit or catastrophe? International Journal of Wildland Fire 17 (6): 696–712. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF07148 .

Keeley, J.E., and C.J. Fotheringham. 2001. Historic fire regime in Southern California shrublands. Conservation Biology 15 (6): 1536–1548. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2001.00097.x .

Keeley, J.E., and A.D. Syphard. 2017. Different historical fire-climate relationships in California. International Journal of Wildland Fire 26 (4): 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF16102 .

Keeley, J.E., and A.D. Syphard. 2018. Historical patterns of wildfire ignition sources in California ecosystems. International Journal of Wildland Fire 27 (12): 781–799. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF18026 .

Keeley, J.E., and S.D. Syphard. 2019. Twenty-first century California, USA, wildfires: fuel-dominated vs. wind-dominated fires. Fire Ecology 15: 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-019-00410 .

Keeley, J.E., and P.H. Zedler. 2009. Large, high intensity fire events in southern California shrublands: debunking the fine-grained age-patch model. Ecological Applications 19 (1): 69–94. https://doi.org/10.1890/08-0281.1 .

Little, J.S., D.L. Peterson, K.L. Rilery, Y. Liu, and C.H. Luce. 2016. A review of the relationship between drought and forest fire in the United States. Global Change Biology 22 (7): 2353–2369. https://doi.org/10.1111/GCB.13275 .

Lombardo, K.J., T.W. Swetnam, C.H. Baisan, and M.I. Borchert. 2009. Using bigcone douglas-fir fire scars and tree rings to reconstruct interior chaparral fire history. Fire Ecology 5 (3): 35–56. https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.0503035 .

Madadgar, S., M. Sadegh, F. Chiang, E. Ragno, and A. Agha Kouchak. 2020. Quantifying increased fire risk in California in response to different levels of warming and drying. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment 34 (12): 2023–2031. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-020-01885-y .

Miller, J.D., E.E. Knapp, and C.S. Abbott. 2021. California National Forests fire records 1911- 1924 . Fort Collins: Forest Service Research Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.2737/RDS-2021-0029 .

Book Google Scholar

Mitchell, J.S. 1947. Forest fire statistics: their purpose and use. Fire Control Notes 8 (4): 14–17.

Morford, L. 1984. Wildland Fires: History of Forest Fires in Siskiyou County . Published by the author.

Nagy, R.C., E. Fusco, B. Bradley, J.T. Abatzoglou, and J. Balch. 2018. Human-related ignitions increase the number of large wildfires across U.S. ecoregions. Fire 1 (4). https://doi.org/10.3390/fire1010004 .

NOAA. 2020a. Historical Palmer Drought Indices. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/temp-and-precip/drought/historical-palmers/

NOAA. 2020b. Summer 2020 ranked as one of the hottest on record for U.S. August was remarkably hot and destructive. https://www.noaa.gov/news/summer-2020-ranked-as-one-of-hottest-on-record-for-us

Rippey, B.R. 2015. The U.S. drought of 2012. Weather and Climate Extremes 10: 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2015.10.004 .

Robeson, S.M. 2015. Revisiting the recent California drought as an extreme value. Geophysical Research Letters 42 (16): 6771–6779. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL064593 .

San Francisco Chronicle. 2020. https://www.sfchronicle.com/projects/california-fire-map/2020- 425 lnu-lightning-complex

Skinner, C.N., and C.-R. Chang. 1996. Fire regimes, past and present. Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project.: Final report to Congress, vol. II. Assessments and scientific basis for management options , 1041–1069. Davis: University of California Centers for Water and Wildland Resources.

Stephens, S.L. 2005. Forest fire causes and extent on United States Forest Service lands. International Journal of Wildland Fire 14 (3): 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF04006 .

Stephens, S.L., B.M. Collins, C.J. Fettig, M.A. Finney, C.M. Hoffman, E.E. Knapp, M.P. North, H. Safford, and R.B. Wayman. 2018. Drought, tree mortality, and wildfire in forests adapted to frequent fire. BioScience 68 (2): 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix146 .

Syphard, A.D., and J.E. Keeley. 2016. Historical reconstructions of California wildfires vary by data source. International Journal of Wildland Fire 25 (12): 1221–1227. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF16050 .

Syphard, A.D., and J.E. Keeley. 2020. Mapping fire regime ecoregions in California. International Journal of Wildland Fire 29 (7): 595–601. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF19136 .

Syphard, A.D., V.C. Radeloff, J.E. Keeley, T.J. Hawbaker, M.K. Clayton, S.I. Stewart, and R.B. Hammer. 2007. Human influence on California fire regimes. Ecological Applications 17 (5): 1388–1402. https://doi.org/10.1890/06-1128.1 .

Syphard, A.D., H. Rustigian-Romsos, M. Mann, E. Conlisk, M.A. Moritz, and D. Ackerly. 2019. The relative influence of climate and housing development on current and projected future fire patterns and structure loss across three California landscapes. Global Environmental Change 56: 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.03.007 .

USDA Forest Service. 1939-1941. Bibliography of Early California Forestry. (69 volumes, WPA Projects 70-10896 and 70-12132, ) housed in the reference department of the University of California . Berkeley: BioScience Library.

Vose, R.S., S. Applequist, M. Squires, I. Durre, M.J. Menne, C.N. Williams Jr., C. Frnimore, K. Gleason, and D. Arndt. 2014. Improved historical temperature and precipitation time series for U.S. climate divisions. Journal of Applied Meteroology and Climatology 53 (5): 1232–1251. https://doi.org/10.1175/JAMC-D-13-0248.1 .

Williams, A.P., J.T. Abatzoglou, A. Gershunov, J. Guzman-Morales, D.A. Bishop, J.D. Balch, and D.P. Lettenmaier. 2019. Observed impacts of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire in California. Earth’s Future 7 (8): 892–910. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EF001210 .

Williams, A.P., R. Seager, J.T. Abatzoglou, B.I. Cook, J.E. Smardon, and E.R. Cook. 2015. Contribution of anthropogenic warming to California drought during 2012-2014. Geophysical Research Letters 42 (16): 6819–6828. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL064924 .

Young, D.J.N., J.T. Stevens, J.M. Earles, J. Moore, A. Ellis, A.L. Jirka, and A.M. Latimer. 2017. Long-term climate and competition explain forest mortality patterns under drought. Ecology Letters 20 (1): 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12711 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the US government. We appreciate the comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript by Keith Lombardo.

Support from institutional funds.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, Sequoia-Kings Canyon Field Station, 47050 General’s Highway, Three Rivers, CA, 93271, USA

Jon E. Keeley

Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, 612 Charles E. Young Drive, South Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, 90095-7246, USA

Vertus Wildfire Insurance Services LLC, 600 California St, San Francisco, CA, 94108, USA

Alexandra D. Syphard

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Data collection and presentation was by the first author: both authors contributed to ideas and writing. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jon E. Keeley .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Keeley, J.E., Syphard, A.D. Large California wildfires: 2020 fires in historical context. fire ecol 17 , 22 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-021-00110-7

Download citation

Received : 24 April 2021

Accepted : 12 July 2021

Published : 25 August 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-021-00110-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- fire severity

- historical fires

- Biodiversity

- Cities & society

- Land & water

- All research news

- All research topics

- Learning experiences

- Programs & partnerships

- All school news

- All school news topics

- In the media

- For journalists

California Burning: Fire, Drought and Climate Change

Stanford Law School’s Professor Buzz Thompson, one of the country’s leading water law experts, discusses California’s wildfires, drought, water, and climate change with Stanford Legal on SiriusXM co-hosts Professors Joseph Bankman and Richard Thompson Ford.

California’s wildfire season started early again this year and its destruction already for the record books with the Dixie fire currently the second largest in the state’s history and growing while the Caldor fire has caused the evacuation of residents from the iconic South Lake Tahoe communities. Here, Stanford Law School’s Professor Buzz Thompson, one of the country’s leading water law experts, discusses California’s wildfires, drought, water, and climate change with Stanford Legal on SiriusXM co-hosts Professors Joseph Bankman and Richard Thompson Ford.

Bankman : Every year, those of us in the West are seeing smoke in our air from wildfires. And I think that’s true from the Pacific Ocean to east of the Rockies right now, isn’t it?

Thompson : Joe you’re absolutely right. We have in the western United States gone from the situation where droughts occurred once every 10 or 20 years, to a situation where we never seem to leave a drought for very long before we enter into it again. We used to talk about fire seasons, nowadays we talk about fire years because they last all year long.

Ford : And right now, the Dixie fire has burned more than 750,000 acres [as of August 29], taking hundreds of homes and businesses with it, and it’s only 35 percent contained. But the fires are connected to a larger phenomenon aren’t they? I mean, we’ve also had record high temperatures in places like Portland and Seattle, where no one owns an air conditioner. Are these things linked in some way?

Thompson : They’re definitely linked. The first thing I want to emphasize is that the Dixie fire is actually the second largest fire in the history of the state of California. The only fire that was bigger than that was the August Complex fire last year, which was over a million acres burned. And actually, last year in 2020, of the 10 largest wildfires in the history of the state of California, half of them—five—occurred in 2020 alone. And now you’re seeing with the Dixie fire that again it is the second largest fire. It’s, as you point out, already over 750,000 acres burned. It’s 35 percent contained at this point, which means it could easily take over the top spot from last year’s August Complex fire.

So, the first thing to recognize is that not only are things bad right now, but they are just far worse than what we have seen before. Second point is that the wildfires are part of just a much larger problem. And I would say that larger problem—you know, really, the ultimate problem— is climate change. And one of the things that we expect from climate change is that disastrous events—droughts, fires and the like—that may have occurred in the past, will occur more frequently in the future, and they will be even worse than they were. And that’s what we’re seeing with wild fires.

But climate change is also leading to another big problem, which is drought and lack of water. And that lack of water can also impact wildfires. In fact, it is a major cause of our wind fires.

Bankman : And Buzz, when we talk about drought, I mean, most of us think about how much rainfall we’ve had. And the last year we had, I think, only about half of what we usually get, if I’m right, depending on the location. The previous year was very light. We have had a cycle of light year, after light year, after light year, light rainfall that is. Is that climate change-related? How do we understand the cycles?

Thompson : Excellent question Joe. And let me first correct you. That last year was a dry year, so we’re in our second dry year. But if you actually go back to 2019, that was the wettest year in the state of California history. And if we had had an interview like this in 2019 I would have said that California is not in a state of drought, it’s a state of whiplash. And it really is. It’s a state where we can be in drought and then suddenly end up with floods, and then go back to droughts.

In the mid-19th century, there was a period of time when it rained in California and Oregon for about 45 days. And it rained so much that it flooded California. It created a lake in the middle of the central valley of California that was about 200 miles long and about 20 miles wide. It flooded the city of Sacramento. By that summer we were at the very beginning of what was known as the great civil war drought of 1862, which impacted the entire nation and was probably one of the worst droughts ever. So, it’s not just droughts we have, but it’s droughts with floods the following year. But this is absolutely what you would expect in the face of climate change. You’re expecting extremes, more extremes, and then more extreme extremes. The drought situation that we have right now, however, is one that we will continue to face, again broken up occasionally by floods. And those droughts are a major cause of, again, the wildfires that we’re seeing right now, as well as a large number of other problems.

Ford : So, not only has California historically been subject to lots of droughts and lots of flooding, but it’s getting worse because of climate change. In this very dramatic way, I’m wondering Buzz, what’s the relationship between all the fires that we’re seeing and new settlements in parts of the state where people didn’t used to live? Is that one of the factors as well contributing to the fires, or is it mainly climate change?

Thompson : I would separate the fire problem, Rich, into two parts. The first is that we are seeing larger fires today and longer wildfire seasons than we had in the past. That’s the result of probably two or three things. The first is that we have historically been suppressing our fires. The answer to fires in the 20th century, and you know this from the old Smokey the Bear advertisements that you used to see on TV or in comic books, was to suppress the fires and try to prevent the fires. But that led to a huge buildup in the fuels. You know, the old dead trees. Very thick forest areas. So that’s contributed to the fires being worse. In addition to that, we have climate change over the last several decades, and that climate change has also led to higher temperatures, more frequent and extreme droughts, and that’s led to tree die-off. So that also increases the fuels that can readily catch fire and spread the fire once that fire begins. So those are two major causes of larger fires, and then longer wildfire seasons.

In addition to that though, the wildfires that we have tend to be more destructive of human settlements, right? So, a fire by itself obviously can be problematic, but our real concern today is entire towns that burn up and displacing people, and all of the smoke that we have to breathe on a regular basis these days. And a lot of that comes from the fact that we haven’t really been doing our land use planning appropriate for the area that we live in. So, we tend to build our towns right in the forest. People love forests. I think it’s great to spend my vacations in forested areas. But a lot of people want to live in and actually build their houses there. Those houses, by the way, are also fuel. But, more importantly, it leads to those people who get displaced. And because, again, we love to live in the west, where we have grand vistas, that means that, unfortunately, we can end up having to breathe the air when these wildfires begin.

Ford : There just are so many causes it’s a little dispiriting.

Thompson : Well another way of looking at that is that we actually have a variety of ways of trying to deal with the problem. The one thing that’s hard to deal with immediately is the climate change. As the recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change noted, climate change is baked into our future, no matter what we do right now in terms of reducing carbon. And we should reduce carbon. It’s baked into our future. We’re going to have it, so we can’t do anything about that.

But we can eliminate a lot of that fuel that has built up by planning smaller prescribed burns in our forests. That’s what our Indigenous population did before we came along and started suppressing the fires. We can also engage in better land use. We can create the defensible spaces within our forest communities. We can have people move when their homes burn down rather than just building exactly where the first are going to occur again.

Bankman : When people live in these areas, they’ve got to bring electricity in. And it seems like a lot of these fires start because there’s a power line outage and we’ve got tens of thousands of miles of, I take it, exposed power lines around.

Thompson : Above ground energy infrastructure is a cause of a variety of fires. The fires are going to be worse than they otherwise would have been, but they are frequently created by those sparks or shortages that occur on the surface. And, in fact, the fire that we started out the show talking about—the Dixie fire—there’s some evidence that that might have been created by a circuit outage on July 13, which led to a blown fuse, and then a tree toppling, and then things catching fire. And one of the things that PG&E is working on—in fact, all of our major electricity utilities in the state of California are working on—is trying to move more and more things underground, and trying to improve the things that are above ground. We absolutely have to do that, but I also just want to emphasize, that costs money. And one of the reasons we frequently didn’t do it in the past was that groups like PG&E were afraid that if they ask for the money necessary to do all of that on a quick basis, they would have had a consumer revolt on their hands. So, we absolutely have to do that, but people have to be willing to spend the money in order to get that done.

Bankman : You know one thing that occurs to me, as you say this Buzz, is that it’s easy to beat up on a utility like PG&E, but ultimately it’s a question of money. And who’s going to pay for it? One interesting issue it raises is what do we do about someone who lives in a fire zone—the cost of making that electricity safe might be really huge. And do we make that person pay for it?

Thompson : I’m not going to make myself popular with communities in our forested foothills and mountains of California, but Joe, you’re absolutely right. It is ultimately a matter of economics and you need to send people the right signals. You should send them a signal at the very outset though, because that’s the easiest time to send people economic signal. To say ‘If you want to build out here, in the middle of nowhere, where, number one, you’re at greater risk. And second of all you’re going to be demanding electricity, and probably the cheapest easiest way to be building will be an above-ground power line. Okay, you can move out here, but here’s the cost you’re going to be imposing, and you should be paying for.’

The next question becomes, what if they’re out there already? Then what type of economic signals might you be able to send them that would be valuable? The Nature Conservancy has been working on ways of building fire breaks around some of these communities in California. And those fire breaks might also serve as parks that people can go to. What if we have a system where people get a discount on their fire insurance if the town invests in the big fire break recreational areas? That’s an example of an economic signal that maybe people won’t be as upset about, because it would actually be a way of lowering their fire insurance costs.

Ford : Buzz, can you talk about a hot drought and how it may be different than the kind of droughts I remember as a kid living in the Central Valley, where occasionally we did have droughts and the farmers were upset about it. So, what’s a hot drought? And why is it more problematic for us in California?

Thompson : That’s a really good question, Rich. We’ve had droughts for centuries in the state of California, and if nothing had changed, we would have continued with that particular pattern. But what we are encountering more and more today is what’s known as a hot drought. In the past, droughts were not connected to a particularly warm year. You could have a drought and it could be a cold year. In the future, all of our droughts are going to be in years that are warmer than they’ve historically been. And that poses a wide variety of problems. In particular, it means that even if we have the same level of precipitation as we had before, less of that actually gets to a river or stream.

The first problem in the western United States that we have with a hot droughts, is that we depend upon our snowpack. All the snow, for example, up on the Sierra mountains, is a natural reservoir for us. We need water in summer and the fall when it’s not going to rain. In the past, that snowpack would melt over time, we could capture it, and we could use it during the time when there wasn’t precipitation. Again, that snowpack is a natural reservoir. Now, that snowpack is disappearing. In drought years now, there is virtually no snow up there, so we’ve effectively eliminated that natural reservoir.

Equally importantly, you have drier soil, so that, when it does rain, what little rain you get during a drought gets absorbed by the soil. Because it’s hotter, you also have higher evaporation. So, in a surface reservoir, more of that actually evaporates.

There is a situation that we are now seeing where snow sublimates, a term which, at best five years ago, I had never heard of. With sublimation, snow goes from the solid state to the gaseous state without ever melting. So, we lose water that way. And then, finally, the plants have higher transpiration rates. That means that we also get those plants absorbing more water and now in the central Valley, where we have all the farmers who are trying to grow crops, they need more water than they needed before. So, all of that means that, no matter what level of precipitation we have, we’re in just much worse shape than we were before.

Bankman : Wow. This is all so sobering. And we talked about wildfires as the problem that we tie to drought. But actually Buzz, there are lots of problems that are tied to drought aren’t there?

Thompson : Absolutely true—there are multiple problems. So, first thing is in a drought, none of us are able to get the water that we normally use. Right now, for example, in California, Governor Newsom has asked all of us to voluntarily cut back on water use by 15 percent. We can do that. It’s an inconvenience, but we can do that. In much worse shape are the farms, because it’s very difficult for the farmers to cut back and then continue to grow the crops that we need. And yet the farmers in the central valley right now are getting virtually none of the surface water that they would historically receive.