National Museum of the American Latino

Latino history and culture.

Learn more about Latino History and Culture

As part of the largest ethnic group in the United States, Latinas and Latinos have significantly contributed to the nation’s identity and have played a vital role in shaping American culture. The Latino population in the United States has grown to over 60 million today, leaving a big impact on its democracy, economy, and culture.

The Latino culture is extremely diverse, and there is no singular Latino experience. Explore Latino foodways, art, and music, and learn about the rich history of Latinos, from pre columbian times to today.

Hispanic Heritage Month is a month-long celebration of Hispanic and Latino history and culture from September 15 to October 15. During this month we give extra recognition to the many contributions made to the history and culture of the United States, including important advocacy work, vibrant art, popular and traditional foods, and much more.

Learn more about Hispanic Heritage Month (external link opens in a new tab)

For US Latinos, Identity Is Complex and Varied

- Opportunities

There is no single, all-encompassing term that fully captures what it means to be Latino in the United States

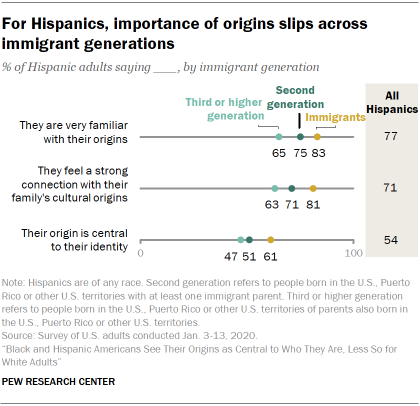

T he ways in which the nation’s sixty million Latinos (or Hispanics or Latinx) describe their identity varies widely across individuals, geographies, immigrant generations, ancestry, and much more. Yet the population is often referred to by a single, pan-ethnic term that implies it is a monolithic group. That masks much of the diversity that characterizes US Latinos.

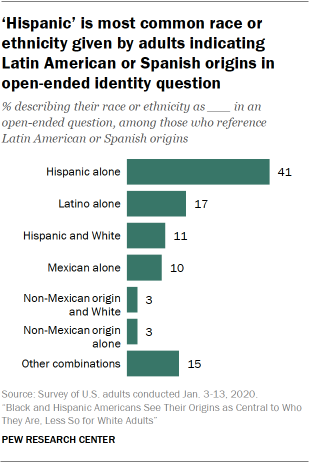

What is a pan-ethnic term? Hispanic , Latino , and Latinx are currently the ones more commonly used by people living in the US who self-identify as part of this group. Each is intended to capture, under one umbrella, a diverse population. And each emerged at different times and with different purposes, reflecting then popular views of identity to describe Americans who trace their roots to Latin America or Spain. For example, Hispanic emerged as the most used term in the 1970s as civil rights leaders and government officials sought to count the population. Latino/Latina/Latina/o/Latin@ emerged in the 1990s as an alternative to Hispanic, notably as a term that did not come from the US government (even if Latino became an officially recognized term in the late 1990s). Both terms remain in wide use by researchers, journalists, government officials, and the public itself. More recently, a new pan-ethnic term has emerged: Latinx. It is a gender-neutral term and reflects the broader movement of inclusivity that has emerged in recent years in the US.

Despite ongoing debates about which term is better or even the right one to use, more than fifteen years of Pew Research Center Latino surveys show somewhat mixed preferences among the public when it comes to using or not using these pan-ethnic terms. For example, while most have used Hispanic or Latino at one point or another to describe themselves, half in 2018 told us they have no preference for either term. If one is preferred, it is Hispanic over Latino by a two-to-one margin, a pattern that has persisted for more than fifteen years of surveys of the US Hispanic adult population.

Instead, it is family country of origin that matters more than pan-ethnic terms. In 2015, we found that more than half said they most often described themselves by terms like Mexican or Cubana or Puerto Rican or Salvadoreño —i.e., the countries where their ancestors are from. This is more likely to be true among immigrant Hispanics (which makes sense given that is where they are from), but also is true among many US-born Hispanics. Even so, later US-born generations of Hispanics are more likely than immigrant Hispanics to say they most often call themselves American, highlighting changes underway within the Hispanic population as the US born drive the group’s population growth and make up a growing share of all Hispanics (just one-third are immigrants today).

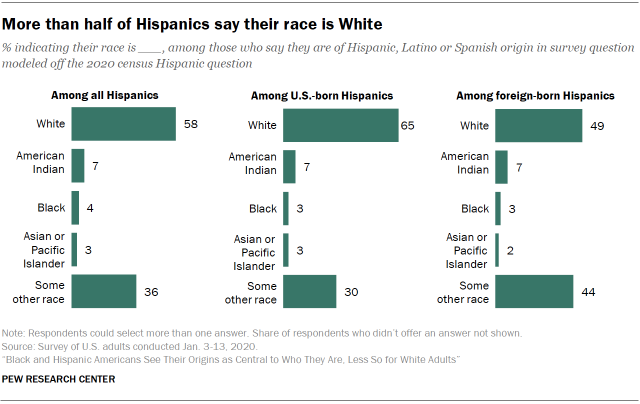

There are many other dimensions to Latino identity. For example, in 2014, one-quarter of Latino adults told us they are Afro-Latino, with those of Dominican and Puerto Rican background making up a large part of the group. And one-quarter of Latino adults are of indigenous roots such as Native American, Mayan, Aymara, Quechua, or Taino. And at least 28 percent say they are mestizo, mestiza, mulatto, or mulatta.

Latinos look at their identity in other ways too. For example, what does it take to be considered Latino by others? In 2015, we asked whether one needs to speak Spanish to be considered Latino—three-quarters say no. What about having a Spanish surname? Eight-in-ten say no. Even among immigrants, majorities agree that one doesn’t need to speak Spanish or have a Spanish surname to be considered Latino in the US.

Looked at another way, do US Latinos see a common culture among themselves or a diverse one? In 2011, 70 percent said US Latinos have many different cultures while just a quarter said they share a common culture.

For some, identity is much more than just about their Hispanic background and that’s important to remember. Some may see themselves as Californians first or as part of Gen Z or as a Catholic first and foremost.

Looking ahead, big demographic trends are reshaping the nation’s Hispanic population. Immigration from Latin America, while up recently, is significantly below highs seen in the late 1990s and early 2000s. As a result, the foreign-born share among Hispanics is falling. At the same time, the group’s population growth rate is slowing as fertility rates fall. And finally, intermarriage rates remain higher for Hispanics than either whites or blacks (Asians intermarry at a higher rate, though)—since at least 1980, one-quarter of Hispanic newlyweds marry a non-Hispanic. In the US today, the single most common intermarried couples are ones where a Hispanic spouse is married to a white spouse accounting for 43 percent of the total.

All these changes may have implications for how the group sees its identity in the future, or if they even identify as Latino. And just as terms have evolved over the decades, it remains to be seen what terms future Latinos will use to describe themselves and their identity.

Mark Hugo Lopez is the director of global migration and demography research at the Pew Research Center.

Connect with him on LinkedIn.

Dr. G. Cristina Mora Keeps the ‘Identity’ Conversation Flowing

To Adriel Lares, Every Day Is an Opportunity to Serve

11 latina influencers to follow.

Meet the Trailblazer Disrupting Silicon Valley’s Status Quo: Rocío Van Nierop

Embracing Global Talent: 10 Tips for Supporting International Employees

Ann Anaya Continues to Advocate for a Fair and Just Outcome

Armando Javier Martinez Benitez Bridges Gaps at TelevisaUnivision

Juan Suarez Elevates DEI at Southwest Airlines

- AI Standards

© 2021 Guerrero LLC. All rights reserved. Hispanic Executive is a registered trademark of Guerrero LLC.

1500 W Carroll Suite 200 Chicago, IL 60607

- TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Being Latina and the struggle of the dualities of two worlds

Reflections on why our identities can help create a better world for all of us.

A few days ago, I attended a Zoom presentation organized by ASUN entitled “What does it mean to be Latinx?” Every time I witness the complexity of identities in the Latinx community in the United States, I am amazed. Amazed that we are always perceived as a homogenous group, when in reality, we couldn’t come from more different backgrounds, and we couldn’t have more different and complex identities. Also, the challenges we face are as different as each of our stories. So, in the spirit of Hispanic Heritage Month, please indulge me in letting me tell you my story.

There is a well-known character in Mexican history that invokes both love and condemnation from most Mexicans. Her name was Malintzin but history knows her as La Malinche . Her story is similar to that of U.S.A.’s Pocahontas ; the beautiful indigenous woman who abandons her tribe to help the white man. (The legends omit how she became the property of such White men, but that’s another story).

La Malinche was a Nahúatl woman who was given to Hernán Cortés as a slave. Due to her upperclass education, she spoke two languages, an ability that made her very useful to Hernán Cortés in communicating with the indigenous people as he went about conquering Mexico. On one hand, she was intelligent and, clearly, resilient. But on the other hand, she helped Cortés begin the Spanish colonization of the Nuevo Mundo. This duality is what gives her such a complex identity. And this duality is one that follows me.

When I was in high school, several of my classmates would sometimes call me Malinchista . As you can imagine, that was NOT a compliment. By definition, a Malinchista is “a person who denies her own cultural heritage by preferring foreign cultural expressions” (I’m not making it up; look it up).

In my early teens, I discovered American football. While switching channels on the television, I stumbled across a game being played in several feet of snow. I had never seen this! The game was being played in Minnesota. That year, the Dallas Cowboys won the Super Bowl, and I became a die-hard fan of Roger Staubach and “America’s Team.” This marked the initiation of my love for all things American. I learned about Formula 1, Sports Illustrated and Tiger Beat. Yes, Tiger Beat introduced me to the American darlings of my generation. My bedroom walls were covered with pictures of American teen idols I had never seen before in my life (in the 1970s, Mexican TV programming didn’t broadcast many American TV shows; I only remember Dallas and The Partridge Family , which of course, I loved).

I also loved English-language songs. I used to spend my money buying cancioneros , books similar in format and quality to comic books, for people who were learning to play the guitar. The cancioneros had the lyrics of the songs along with the music notes. I literally used these cancioneros to practice my English. I would translate each word of the songs, and then I would play the records over and over until I memorized the lyrics and could actually follow the singer pronouncing the words. Do you know how hard it is to sing at full speed: “Now they know how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall?”

By the time I was in college, I had already spent time in the city of Dallas (and yes, I made the pilgrimage to Irving, Texas and the Cowboys’ stadium) – and perfected my English. I started studying English when I entered first grade. By middle school, my parents were paying a private tutor. In Mexico, English was accepted as the lingua franca needed to succeed in the world, and my parents were going to make sure I learned it. (My dad had taught himself English, and he shared my enthusiasm for English language magazines, although not for the Dallas Cowboys.) Learning a second language allowed me to learn about, navigate and integrate into a different culture. And, unlike La Malinche , I did this of my own volition.

When I made the decision to come to the United States to study, my father told me, “If you ever decide this is not for you or things don’t work out, come back home.” But I was not turning back. In my mind, America was the best place in the whole world (my small world, at least). I had spent a semester in an exchange program at the University of Oklahoma, and I knew back then I belonged in the United States. One of the things that caught my attention early on was the fact that people could wear their pajamas to class (I know you’ve seen it), and nobody blinked an eye. One could wear her hair in blue spikes or wear slippers to the grocery store, and no one would say a thing. To me, that was amazing! People didn’t bother you, judge you or care what you wore. I felt America was the place where not only public services worked, but where you could be yourself and you could be free to be whomever you wanted to be. There was a sense of freedom that was refreshing.

However, for a long time I felt like I didn’t belong here, and I didn’t belong in Mexico, either. Navigating two worlds was not precisely difficult but sometimes unsettling . You spend your time “live switching” from English to Spanish to Spanglish and back again. You mix Cholula with Five Guys hamburgers. You watch American soccer but listen to the Mexican commentators (otherwise it’s like listening to golf announcers). And you truly think Mexican soccer fans are like the old Oakland Raiders fans, only worse. Women in Mexico are as rabid fans as many men, but, at least back in my day (I feel ancient now), you didn’t see many women go to the stadiums. As a woman, I never felt safe. I only went to a match if my male friends went with me. This is one of the most striking differences between the U.S. and Mexico: American soccer fans are so mild-mannered in comparison!

Another striking difference I noticed when I first came to the U.S. was that I was not getting cat calls out when I was out walking in the streets. In Mexico, everywhere I went (since I was a preteen, for goodness’ sake), I would be subjected to cat calls and whistles – and the harassment only got worse the older I got. My experience as a woman was of always being on high alert. But when I came to the U.S., I felt respected. I could exist without being harassed continually. Women here seemed to have a voice and the same opportunities as men to grow and pursue their dreams. I felt free to pursue a career and to not be expected to only dream of marrying and having children. Although, over the years, I’ve come to realize there still is much room for improvement.

Back in the 1500s La Malinche did what she could to survive (did I say historians think she died before she was 30?). History asked her to do a task she didn’t want, and she did her best. I am sure she considered her options and bought time, respect and the right to live in the best way she could. She used her skills to earn a place in history, and although her role continues to be debated, I cannot blame her. Did I turn my back on my country? Or did I look for a better life? My circle of Latina friends in the U.S. is full of intelligent, professional women who left their countries and built a better life – a different life – here in the United States. They all miss their families, and they all support their biological families in many ways. What they can do from here, however, is more than they could have done had they stayed in their countries of origin.

Being Latina in America is both an honor and a challenge. We struggle with the dualities of our worlds. We struggle with the adjectives that define us. We are a complex mix of races, traditions and experiences. We care for our people, and we work tirelessly to do what must be done to help each other. The complexity of our identities can help us create a better world for all of us, a world where our differences are not viewed as a threat but as an asset. A world where we all thrive. ¡Sí, se puede!

By: Claudia Ortega-Lukas Graphic Designer & Communications Professional

Optimism Series Domestic Mining Green Opportunities

Nevada Gold Mines Professor Pengbo Chu in the Department of Mining and Metallurgical Engineering sees domestic mining as a way to change the mining industry into a green industry

Art 100 student stickers

The artwork is displayed throughout campus and was created using equipment from the DeLaMare Science and Engineering Library (DLM) Makerspace and Art Department’s Fablab

Optimism Series curb the effects of climate change

Associate Professor Julie Loisel in the Department of Geography outlines some of the solutions we can implement to aid in the global fight against climate change

Investing in women's health

Global researcher and advocate for the improvement of child and maternal nutrition, Angeline Jeyakumar, discusses iron deficiency, a common issue in women's health, for National Women's Health Month

Editor's Picks

AsPIre working group provides community, networking for Asian, Pacific Islander faculty and staff

University confers more than 3,000 degrees during spring commencement ceremonies

Father and son set to receive doctoral degrees May 17

Strong advisory board supports new Supply Chain and Transportation Management program in College of Business

Nevada Today

Mackay School celebrates another year of excellence

The annual John W. Mackay Banquet took place on April 26

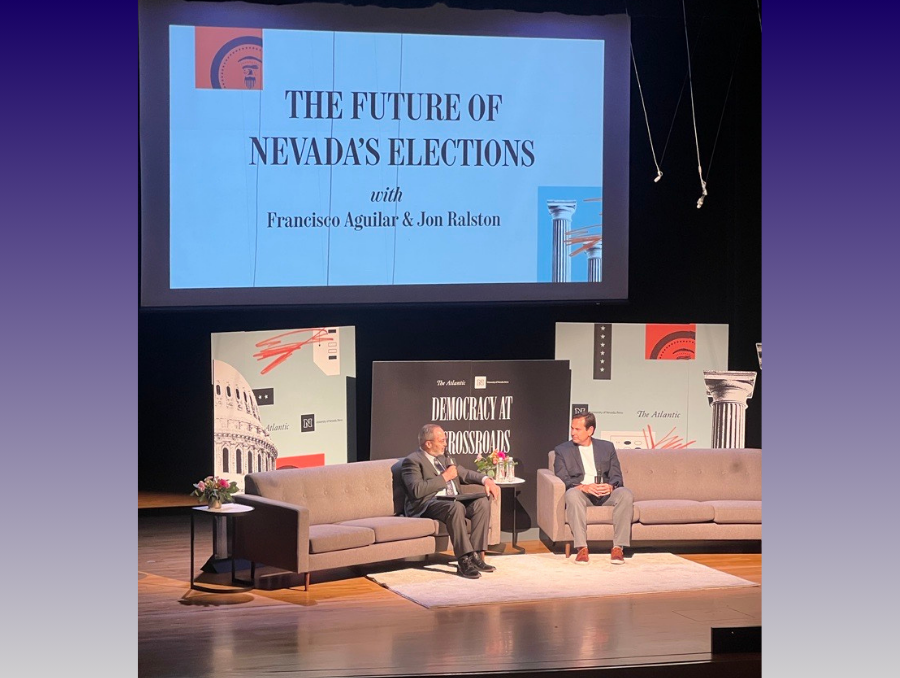

Publication 'The Atlantic' gifts complimentary access to University community

Following the ‘Democracy at a Crossroads’ event, students, faculty and staff can access the publication through the University Libraries

Visit Lake Tahoe on May 30 to learn about “The Promise of Chemical Ecology”

Neurodegenerative disease prevention, “blue zones” and environmental conservation to be discussed at the Hitchcock Center for Chemical Ecology keynote presentation

Reynolds School of Journalism looks back at the spring 2024 semester

Dean Yun recaps the highlights of the semester in the semester in review video

Co-chair of AsPIre Cydney Giroux discusses the group, why she finds it important and plans for the future

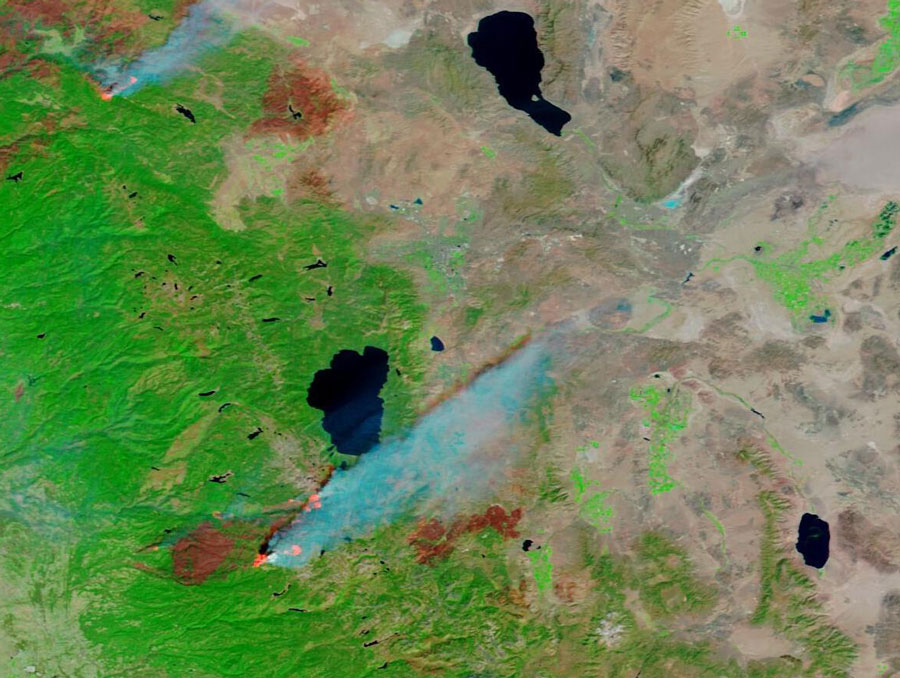

Lake Tahoe Wildfire Summit explores interdisciplinary solutions

University of Nevada, Reno researchers and scholars share their expertise and collaborate on potential wildfire management solutions

Grads Of The Pack: Emily Thao-Singh

Thao-Singh graduated from the School of Public Health and gave a speech at the Asian Pacific Islander Affinity Graduation Ceremony

Medical School class of 2024 commencement celebrates overcoming COVID-19 challenges

The University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine graduated 69 new doctors

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Personal and Cultural Identity Development in Recently Immigrated Hispanic Adolescents: Links with Psychosocial Functioning

1 University of Miami

Raha F. Sabet

Colleen m. farrelly, cynthia g. benitez.

2 Florida International University

Seth J. Schwartz

Melinda gonzales-backen.

3 Florida State University

Elma I. Lorenzo-Blanco

4 University of South Carolina

Jennifer B. Unger

5 University of Southern California

Byron L. Zamboanga

6 Smith College

Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati

Simona picariello.

7 University of Napole

Sabrina E. Des Rosiers

Daniel w. soto, monica pattarroyo, juan a. villamar.

9 Northwestern University

Karina M. Lizzi

10 University of Michigan

This study examined directionality between personal (i.e., coherence and confusion) and cultural identity (i.e., ethnic and US) as well as their additive effects on psychosocial functioning in a sample of recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents.

The sample consisted of 302 recent (<5 years) immigrant Hispanic adolescents (53% boys; M age = 14.51 years at baseline; SD = .88 years) from Miami and Los Angeles who participated in a longitudinal study.

Results indicated a bidirectional relationship between personal identity coherence and both ethnic and US identity. Ethnic and US Affirmation/Commitment (A/C) positively and indirectly predicted optimism and negatively predicted rule breaking and aggression through coherence. However, confusion predicted lower self-esteem and optimism and higher depressive symptoms, rule breaking, unprotected sex, and cigarette use. Results further indicated significant site differences. In Los Angeles (but not Miami), ethnic A/C also negatively predicted confusion.

Given the direct effects of coherence and confusion on nearly every outcome, it may be beneficial for interventions to target personal identity. However, in contexts such as Los Angeles, which has at least some ambivalence towards recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents, it may be more beneficial for interventions to also target cultural identity to reduce confusion and thus promote positive development.

Identity development is a key developmental task of adolescence and emerging adulthood ( Kroger, 2007 ). Developing a coherent sense of self helps to support a consistent set of choices in career aspirations ( Côté, 2002 ) and romantic relationships ( Beyers & Seiffge-Krenke, 2010 ). Moreover, individuals with an internally consistent sense of identity report higher self-esteem, lower internalizing symptoms, and are less likely to engage in risk-taking behaviors compared to individuals with less coherent identities ( Crocetti et al., 2014 ). For adolescents from immigrant and ethnic/racial minority backgrounds, identity development can be more complex compared to United States (US) born, ethnic majority youth ( Azmitia, Syed, & Radmacher, 2008 ; Syed & Mitchell, 2013 ). In addition to developing a general sense of personal identity, which is a normative developmental task for all adolescents, immigrant and ethnic/racial minority adolescents are also tasked with navigating multiple cultural reference points. As a result, these adolescents are confronted with the task of developing a cultural identity – an understanding of what their ethnic/racial group and membership in the larger nation mean to them.

Although personal and cultural identity are among the most commonly studied identity components, the interplay and directionality between personal and cultural identity remains understudied ( Schwartz et al., 2013 ; Syed & Juang, 2014 ). To address this gap in the literature, in the current study we sought to examine directionality between personal and cultural identity, as well as their effects on psychosocial functioning. Additionally, we examined whether these processes differ across two contexts of receptions (Miami and Los Angeles) in a sample of recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents. We focus on Hispanic immigrant adolescents for four reasons. First, Hispanics are among the largest and fastest growing minority groups in the US ( Ennis, Ríos-Vargas, & Albert, 2011 ). Second, as immigrants and ethnic minorities, recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents face the additional task of developing a cultural identity, on top of the normative task of developing a personal identity ( Schwartz, Montgomery, & Briones, 2006 ). Third, recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents are likely to experience cultural stressors which may complicate cultural identity development ( Rumbaut, 2008 ) and the development of a coherent personal identity. Finally, our focus on Hispanic adolescents is driven by a growing body of research indicating significant health disparities. Indeed, research indicates that Hispanic adolescents are more likely than other ethnic groups to use drugs and alcohol ( Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2014 ), smoke cigarettes ( Kann et al., 2014 ), and report depressive symptoms ( McLaughlin, Hilt, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2007 ). As a result, more developmentally informed prevention research is needed that focuses on identifying mechanisms underlying Hispanic adolescents’ psychosocial functioning ( Umaña-Taylor, 2011 ).

Personal and cultural identity have inspired separate literatures ( Syed & Juang, 2014 ). Personal identity focuses on the set of goals, values, and beliefs that an individual has developed and/or internalized ( Waterman, 1999 ). Personal identity therefore represents the answer to the question “Who am I?” Cultural identity, on the other hand, refers to how individuals define themselves in relation to the cultural groups to which they belong ( Schwartz et al., 2006 ), and therefore more closely represents the answer to the question “who am I as a member of my group?” ( Schwartz, Zamboanga, & Weisskirch, 2008 ). Although personal identity is salient for most young people, who must decide who they want to be and what to do with their lives ( Côté & Levine, 2002 ), cultural identity is most salient for immigrants and ethnic minorities youth ( Phinney & Ong, 2007 ). To provide a more complete conceptualization of personal and cultural identity, we provide a brief review of both these identity domains and the underlying theoretical perspectives.

Personal identity

Much of the literature on personal identity traces its roots to Erikson’s (1950) model of psychosocial development. According to Erikson (1950) , identity develops in a dynamic manner involving coherence and confusion. Coherence refers to a sense of who one is and where one is going in life, whereas confusion signifies an inability to enact and maintain lasting commitments and a lack of a clear sense of purpose and direction. Although these two dimensions are negatively related, they are not complete opposites. People can show coherence in some domains and confusion in others ( Schwartz, Zamboanga, Wang, & Olthuis, 2009b ). We focus on coherence and confusion for two primary reasons. First, coherence and confusion refer to the overall sense of where a person is with respect to her/his personal identity development ( Schwartz, Luyckx, & Crocetti, 2014b ). Second, coherence and confusion uniquely and significantly predict positive and negative psychosocial functioning (e.g., Syed et al., 2013 ). Therefore, we rely on personal identity coherence and confusion (hereby referred to as coherence and confusion) as indices of personal identity in the present study.

Cultural identity

Although the operationalization of cultural identity has varied in the literature, the current study focused on e thnic and US identity , two components particularly salient for recent immigrants in the US ( Phinney & Ong, 2007 ). Broadly, ethnic and US identity can each be represented as multidimensional psychological constructs that reflect individuals’ beliefs and attitudes about their ethnic and national group membership as well as the process by which these beliefs and attitudes develop over time ( Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014 ). In this study, we focus on the process by which individuals consider the subjective meaning of their ethnic group or membership in the larger US society, and develop emotional attachments to both of these cultural groups ( Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014 ). Process models ( Phinney, 1990 ; Schwartz et al., 2012 ) have drawn largely on Erikson’s (1950) work and on social identity theory ( Tajfel & Turner, 1986 ), positing exploration (i.e., considering what it means to belong to a particular cultural group), commitment (i.e., making a decision regarding the subjective meaning of one’s cultural group membership), and affirmation (i.e., positive/negative feelings about one’s cultural group membership) as underlying processes.

Most cultural identity research has focused on ethnic identity. Among Hispanics, studies have generally found ethnic identity affirmation and commitment to be positively and negatively associated, respectively, with adaptive and maladaptive psychosocial functioning. However, as reviewed by Rivas-Drake et al. (2014) and Umaña-Taylor (2011) , these relationships have not emerged consistently across studies. One potential explanation for this inconsistency is the reliance on ethnic identity as the sole indicator of cultural identity. Because the development of an integrated sense of self and identity incorporates elements from one’s ethnic group and the US ( Berry, 1997 ), it is essential for researchers to evaluate the joint effects of ethnic and US identifications on psychosocial functioning—particularly among recently immigrated adolescents.

In this study, to facilitate appropriate comparisons between personal and cultural identity, drawing on social identity theory ( Tajfel & Turner, 1986 ), we focused on the ethnic and US affirmation and commitment. Specifically, whereas coherence is strongly related to self-concept clarity ( Schwartz et al., 2011 ), commitment and affirmation are conceptually similar to “cultural identity clarity,” or a sense of belonging (commitment) and solidarity (affirmation) with one’s cultural group(s) ( Usborne & Taylor, 2010 ). Thus, cultural commitment and affirmation represent key components of a consolidated sense of ethnic and US identity ( Schwartz et al., 2013 ). Although commitment and affirmation represent distinct yet related cultural identity processes (Umana-Taylor, Yazedjian, & Bamaca-Gomez, 2004), within the current sample, these subscales were highly correlated ( r > .90). As a result, in the current study, we employed ethnic affirmation/commitment (A/C) and US A/C as indicators of a consolidated sense of ethnic and US identity, respectively.

The Interplay between Personal and Cultural Identity

Although empirical evidence suggests that personal and cultural identity are positively associated with well-being and inversely associated with internalizing and externalizing symptoms ( Crocetti et al., 2014 ; Rivas-Drake et al., 2014 ), the ways in which these variables work together are not well understood ( Schwartz et al., 2013 ). It is possible that the additional task of developing a cultural identity might make the development of a personal identity more difficult. However, given the theoretical links between personal and social identity, it is likely that personal and cultural identity (where cultural identity may be considered as a dimension of social identity) may be reciprocally connected ( Schwartz et al., 2008 ). Indeed, some aspects of personal identity are assigned, informed, constrained, or internalized based on group memberships ( Bosma & Kunnen, 2001 ; Hitlin, 2003 ). Moreover, personal goals, values, and beliefs can be influenced by cultural orientation ( Triandis, 1995 ). For example, highly collectivistic values may lead to internalization of goals from close social networks (e.g., family, close friends, etc.), whereas individualistic values may lead to independent establishment of personal goals. In the other direction, a coherent personal identity provides individuals with a sense of structure within which to understand self-relevant information ( Adams & Marshall, 1996 ) and thus shapes how individuals negotiate with the social environment and the opportunities they choose to pursue ( Côté, 2002 ).

Although several studies have found significant and positive associations between ethnic and personal identity among adolescents (e.g., Branch, Tayal, & Triplett, 2000 ; Miville, Darlington, Whitlock, & Mulligan, 2005 ), most have been cross-sectional. Moreover, only a handful of these studies have examined the relationship of personal and cultural identity with psychosocial functioning (e.g., Schwartz, Zamboanga, Weisskirch, & Wang, 2010 ; Usborne & Taylor, 2010 ). Both Schwartz et al. (2010) and Usborne and Taylor (2010) found support for the idea that that cultural identity is indirectly associated with psychosocial functioning through personal identity. However, the cross-sectional nature of these and earlier studies has made it difficult to establish directionality ( Maxwell & Cole, 2007 ), which is critical for determining strategic points of intervention. For example, if personal identity predicts psychosocial functioning by bolstering cultural identity, then interventions might focus on promoting cultural identity to prevent negative outcomes. On the other hand, if cultural identity predicts psychosocial functioning by bolstering personal identity, then interventions might focus on promoting personal identity instead. However, if the relationship between personal and cultural identity is bidirectional, then interventions should focus on both personal and cultural identity as a means to prevent negative outcomes.

Because identity emerges within the opportunities and constraints provided by sociocultural factors ( Côté & Levine, 2002 ; Umana-Taylor et al., 2014), it is important to determine whether identity processes work similarly across cultural contexts. In the current study, we explored the directional relationship between personal and cultural identity across two sites: Miami and Los Angeles. Miami is a thriving metropolis as a result of the influx of Cuban migration ( Portes & Stepick, 1994 ), aided by a law that allows them to become legal US residents immediately upon arrival ( Stepick & Stepick, 2002 ). Miami is also a highly bicultural city where Hispanics are the majority of the population (65%; US Census Bureau, 2011 ) and hold many positions of political and economic power ( Stepick, Grenier, Castro, & Dunn, 2003 ). In contrast, although Los Angeles has been home to a large Mexican population for several decades, the majority of city officials and leaders have been White ( Hayes-Bautista, 2004 ; Light, 2006 ). Indeed, studies using the current dataset indicate that recently immigrated Hispanics in Los Angeles encounter higher perceived discrimination and negative context of reception than their Miami counterparts ( Schwartz et al., 2015 ).

In the present study, we used data from a longitudinal study of acculturation among recently arrived Hispanic immigrant families from Miami and Los Angeles, to achieve three primary aims: (1) examine the directionality between personal (coherence and confusion) and cultural (ethnic and US) identity, (2) evaluate the effects of personal and cultural identity on psychosocial functioning and health outcomes, and (3) examine the moderating role of site. For the first aim, we anticipated a bidirectional relationship between personal and cultural identity. For the second aim, although these processes may operate on psychosocial functioning in complex ways, prior cross-sectional research has suggested that personal identity predicts psychosocial functioning more strongly than cultural identity does and may even mediate the relationship between cultural identity and psychosocial functioning ( Schwartz et al., 2010 ; Usborne & Taylor, 2010 ). As a result, we hypothesized that: (2a) coherence and confusion would positively predict positive psychosocial functioning and negatively predict negative psychosocial functioning and health risk behaviors more strongly than ethnic and US identity would; and (2b) cultural identity would predict outcomes indirectly through personal identity. Finally, with regard to Aim 3, given the fact that discriminatory events can activate cultural identities and render them more salient ( Rumbaut, 2008 ) and the protective role of ethnic identity vis-à-vis the negative experiences associated with discrimination ( Umaña-Taylor, 2011 ), we hypothesized that cultural identity would predict psychosocial functioning and health risk behaviors more strongly for adolescents in Los Angeles versus Miami.

Data came from a six-wave longitudinal study on acculturation, identity, family functioning, and health among recent Hispanic immigrant families ( Schwartz et al., 2014c ). The sample included 302 recent-immigrant Hispanic adolescents (53% boys; M age =14.51 years at baseline; SD =.88 years, range 14–17 years). Eighty-five percent of the sample was retained across the four waves. The Miami sample ( n =152) was primarily from Cuba (61%), the Dominican Republic (8%), Nicaragua (7%), Honduras (6%), Colombia (6%), and other Hispanic countries (12%); and the Los Angeles sample ( n =150) was primarily from Mexico (70%), El Salvador (9%), Guatemala (6%), and other Hispanic countries (15%).

Baseline data were gathered during the summer and fall of 2010, and subsequent time points occurred every six months thereafter. Participants were recruited from randomly selected public high schools whose student bodies were at least 75% Hispanic. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both participating universities and by the Research Review Committees for the participating school districts. Each participant completed the assessment in English or Spanish, depending on her/his preference. Although 84% of adolescents completed their baseline assessments in Spanish, this percentage decreased to 66% by Time 4.

Unless otherwise specified, 5-point Likert scales were used for all study measures, with response options ranging from 1 ( Strongly Disagree ) to 5 ( Strongly Agree ). Alpha coefficients presented are from the current sample across relevant time points and for both English and Spanish versions. All measures were administered at each time pointed and developed using a two-step translation process ( Sireci, Wang, Harter, & Ehrlich, 2006 ) whereby measures are translated by one translator from English to Spanish, back-translated by a second translator (Spanish to English), and then evaluated by both translators to resolve discrepancies.

Coherence and confusion

The 12-item identity subscale from the Erikson Psychosocial Stage Inventory (EPSI; Rosenthal, Gurney, & Moore, 1981 ) was used to assess coherence and confusion. Six items are worded in a “positive” direction towards coherence (α=.69–.87; Sample item: “I know what kind of person I am”), and 6 items are worded in a “negative” direction towards confusion (α=.62–.77; Sample item: “I don’t really know who I am”). Prior analyses have not only established the validity of the measure in Spanish ( Schwartz et al., 2014a ) but also supported the two-factor structure, even after controlling for potential methodological effects of item wording ( Schwartz et al., 2009b ).

Ethnic and US identity A/C

Ethnic A/C was assessed by combining the 4-item commitment and 3-item affirmation subscales from the Multi-Group Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Roberts et al., 1999 ; α=.84–.93; Sample item: “I feel good about my cultural or ethnic background’). US A/C was assessed using matching items from the American Identity Measure (AIM; Schwartz et al., 2012 ; α= 87–.90; Sample item: “I am happy that I am an American”), again combining the commitment and affirmation subscales. The AIM was adapted from the MEIM, with “the United States” inserted in place of “my ethnic group.” Prior findings have established the validity of both the AIM and MEIM in Spanish ( Schwartz et al., 2014a ).

Positive psychosocial functioning

We assessed this construct in terms of self-esteem and optimism. The 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Coopersmith, 1981 ) was used to measure self-esteem (α=.72–.84; Sample item: “On the whole, I am happy with myself”). This measure has been used widely with Spanish-speaking samples ( Schmitt & Allik, 2005 ). The 6-item Children’s Hope Scale (CHS; Edwards, Ong, & Lopez, 2007 ) was used to measure optimism (α=.87–.95; Sample item: “I think I am doing pretty well”). This measure was designed specifically for use with Hispanics.

Negative psychosocial functioning

We assessed this construct in terms of depressive symptoms, rule breaking, and physical aggression. The 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977 ) assessed adolescents’ depressive symptoms (α=.81–.89, sample item: “I felt sad this week”). Items are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 ( Seldom ) to 4 ( Most of the Time ) and ask participants how often they experienced various depressive symptoms during the week prior to assessment. The CES-D has been translated into Spanish and used frequently with Hispanic individuals (e.g., Todorova, Falcón, Lincoln, & Price, 2010 ). The Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach, Newhouse, & Rescorla, 2004 ) was used to assess adolescents’ aggressive (17 items, α=.87–.93, sample item: “I physically attack people”) and rule breaking (15 items, α=.87–.92, sample item: “I lie or cheat”) behaviors. Response choices ranged from 0 ( Not true ) to 2 ( often or very true ). The YSR has been validated with Spanish-speaking adolescents ( Lopez et al., 2008 ).

Health risk behaviors

Cigarette and alcohol use were assessed using a modified version of the Monitoring the Future survey ( Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2014 ). Adolescents were asked about frequency of cigarette and alcohol use 90 days prior to each assessment point. Following Jemmott, Jemmott, and Fong (1998) , we asked adolescents how often they have had vaginal or anal sex without using a condom during the past 90 days. The scale ranged from 0 ( Never ) to 4 ( Always ). Because of low base rates, we dichotomized the responses to create binary variables for alcohol use (use vs. nonuse), cigarette use (use vs. nonuse), and unprotected sex (abstinence/condom vs. sex without a condom) at Time 4.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted in Mplus v7.2 ( Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012 ) using a sandwich covariance estimator ( Kauermann & Carroll, 2001 ) to adjust the standard errors and account for nesting of participants within schools. Missing data were handled using full-information maximum likelihood estimation. Model fit was evaluated using the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). According to values suggested by Little (2013) , good fit is represented as CFI≥.95, RMSEA≤.06, and SRMR≤.06 1 . The analytic process proceeded in five steps. Across all steps, we controlled for age, gender, and years in the US. First, we calculated descriptive statistics and a correlation matrix for all study variables.

Second, to establish directionality of effects, we fit a model to the first three waves of data, such that cross-lagged paths from Times 1 to 2 and Times 2 to 3 were included between personal and cultural identity indicators (see Figure 1a ). Directional paths between personal and cultural identity were estimated from Times 1 to 2 (paths A1 and B1) and Times 2 to 3 (paths A2 and B2) as a way to examine replicability of the findings. Additionally, we allowed directional paths between indicators within each domain (e.g., coherence → confusion, US A/C → ethnic A/C). Moreover, to statistically ensure that any directional effects could be replicated, we explored stationarity, or non-varying cross-lagged paths across time ( Allison, 1990 ). This was done by imposing equality constraints on corresponding cross-lagged relationships from Times 1–2 and Times 2–3, such that path A1 was constrained to be equal to A2, and B1 constrained to be equal to B2 (see Figure 1b ). For example, the path estimate between coherence at Time 1 ( t ) and ethnic A/C at Time 2 ( t +1) was constrained to be equal to the path estimate between coherence at Time 2 ( t ) and ethnic A/C at Time 3 ( t +1), producing one set of lagged path estimates corresponding to Time t and Time t +1 (paths A and B). To evaluate the tenability of these stationarity constraints, we compared the fit of models with and without these constraints using the ΔCFI (>.010) and ΔRMSEA (>.010) criteria to determine whether the stationarity assumption should be statistically rejected ( Little, 2013 ) 2 .

Overview of Stationarity Constraints

To examine how these relationships may influence later positive development and risk behaviors, as part of Step 3, Time 4 outcome variables were added to the stationarity model, predicted by Time 3 personal and cultural identity processes (i.e., Personal/Cultural Identity Time 1–(paths A/B)→ Personal/Cultural Identity Time 2 –(paths A/B)→ Personal/Cultural Identity Time 3 –(path C)→ Outcomes Time 4). For each Time 4 outcome variable, Time 1 levels of that variable were controlled. In Step 4, we examined whether Time 3 cultural identity mediated the effect of invariant Time 1 and 2 personal identity on Time 4 outcome variables, and/or whether Time 3 personal identity mediated the effect of invariant Time 1 and 2 cultural identity on Time 4 outcome variables. Finally, in Step 5, we tested for significant site differences.

Step 1: Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 provides means and standard deviations or frequencies for categorical outcomes and a zero-order correlation matrix for identity processes at T3 and outcomes at T4.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations between Time 3 Identity Processes and Time 4 Outcomes

Notes. Bivariate correlations for the Miami site are presented above the diagonal while the bivariate correlations for Los Angeles are provided below the diagonal.

Step 2: The Interplay between Personal and Cultural Identity

The cross-lagged model provided a poor fit to the data: χ 2 (25)=101.075, p <.001; CFI=.890; RMSEA=.100; SRMR=.046. Modification indices indicated that we should allow coherence and ethnic A/C to covary at Times 1, 2, and 3. Upon adding these covariances, the model provided good fit: χ 2 (24)=4.146, p <.001; CFI=.968; RMSEA=.065 SRMR=.032. Building on this model, we imposed stationarity constraints on the cross-lagged relationships between personal and cultural identity indices. Invariance tests suggested that the stationary assumption could be retained, Δχ 2 (16)=25.565, p =.060; ΔCFI=.010; ΔRMSEA=.007. Given these stationarity constraints, the findings can be simplified to comparing the cross-lagged path coefficients between Times t and t +1. As shown in Table 2 , coherence at Time t significantly predicted both ethnic and US A/C at Time t +1. Additionally, both ethnic and US A/C at Time t predicted coherence at Time t +1. However, confusion did not predict, and was not predicted by, any of the other identity variables. There were no significant predictive relationships between ethnic and US A/C.

Cross-Lagged Paths for Constrained Directionality Model

Notes . All estimates are standardized regression coefficients.

To compare these path coefficients formally, we conducted four sets of invariance tests (e.g., coherence = ethnic A/C, confusion = US A/C). We compared the stationarity model to a model where the path coefficient for identity process A at Time t predicting identity process B at Time t +1 was constrained equal to the path coefficient for identity process B at Time t predicting identity process A at Time t +1. The results indicated a significant decline in model fit for ethnic A/C and coherence [Δχ 2 (1)=19.99, p <.001; ΔCFI=.030; ΔRMSEA=.015] and U.S. identity A/C and coherence [Δχ 2 (1)=7.61, p =.005; ΔCFI=.013; ΔRMSEA=.007] suggesting that the predictive effects of coherence on ethnic and US A/C were significantly stronger than vice versa.

Step 3: Effects of Personal and Cultural Identity on Psychosocial Functioning

Addressing the second hypothesis, and building on the cross-lagged model, we then included Time 4 outcomes, with controls for Time 1, in the model to evaluate the effects of Time 3 personal and cultural identity variables on psychosocial functioning. Because modeling categorical outcomes in MLR does not produce fit indices ( Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012 ), we first estimated the model without the dichotomous health risk outcomes to ascertain model fit. This model provided acceptable to good fit: χ 2 (140)=232.831, p <.001; CFI=.935; RMSEA=.048; SRMR=.055. We then added the categorical outcomes. Standardized path estimates for continuous variables, and odds ratios for categorical outcome variables, are displayed in Table 3 . Additionally, Figure 2 presents significant directional paths within the model. Results indicated that coherence positively predicted optimism and negatively predicted rule breaking and aggression. On the other hand, confusion positively predicted depressive symptoms, rule breaking, unprotected sex, and alcohol use and negatively predicted self-esteem and optimism. With regard to cultural identity, US A/C negatively predicted depressive symptoms; however, ethnic A/C did not significantly predict any outcomes.

Note . With the exception of categorical outcomes (i.e., cigarette use, alcohol use, and unprotected sex), which are Odds Ratio, all estimates are standardized regression coefficients. Parameter values from Time 1 to Time 2 and Time 2 to Time 3 are identical as a result of the stationarity constraints imposed in Step 1. For simplicity we have excluded 1) the autoregressive paths and 2) Time 1 controls.

Effects of Personal and Cultural Identity on Psychosocial Functioning

Notes. Autoregressive paths not displayed. All estimates are standardized regression coefficients.

Step 4: Mediated effects of personal and cultural identity on psychosocial functioning

On the fourth step, we examined two sets of mediated pathways: (1) invariant Time 1 and 2 Personal Identity → Time 3 Cultural Identity → Time 4 psychosocial functioning, and (2) invariant Time 1 and 2 Cultural Identity → Time 3 Personal Identity → Time 4 psychosocial functioning. Using the RMediation package ( Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011 ), we evaluated indirect effects of personal and cultural identity on outcome variables. All indirect effects were included in a single model to avoid Type I error inflation. Doing so provides more statistical power, and greater rigor, compared to the original Baron and Kenny (1986) approach to testing mediation ( Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007 ). The RMediation package uses the asymmetric distribution of products test, which computes a 95% confidence interval around the product of the two path coefficients that comprise each potential mediating pathway. If this confidence interval does not include zero, then mediation is assumed at p <.05 ( Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011 ).

As displayed in Table 4 , seven indirect effects were found to be significantly different from zero. Specifically, invariant Time 1 and 2 ethnic A/C positively predicted Time 4 optimism, and negatively predicted Time 4 rule breaking and aggression, through Time 3 coherence. Similarly, invariant Time 1 and 2 US A/C positively predicted Time 4 optimism, and negatively predicted Time 4 rule breaking and aggression, through Time 3 coherence. Lastly, invariant Time 1 and 2 coherence negatively predicted Time 4 depressive symptoms through Time 3 US A/C.

Indirect Effects of Personal and Cultural Identity on Psychosocial Functioning

Notes. All estimates reported are standardized regression coefficients and all indirect paths are significant at p <.050.

Step 5: Invariance across Site

Finally, we sought to ascertain whether any of the effects differed across sites. To do this, we compared an unconstrained model (with all paths free to vary across site) to a constrained model (with each path constrained to be equal across site) using the likelihood ratio test to evaluate the null hypothesis of equivalent findings across sites. This test provides only a chi-square difference and does not provide any other SEM fit indices. We found a significant difference in fit between these two models, Δχ 2 (51)=115.01, p <.001. As a result, we proceeded to examine each path for consistency across site by constraining one path at a time and examining the change in the log likelihood value. These follow-up analyses indicated several significant differences (see Table 5 , Figure 3 , and Figure 4 ).

Note . With the exception of categorical outcomes (i.e., cigarette use, alcohol use, and unprotected sex), which are Odds Ratio, all estimates are standardized regression coefficients. Parameter values from Time 1 to Time 2 and Time 2 to Time 3 are identical as a result of the stationarity constraints imposed in Step 1. For simplicity we have excluded 1) the autoregressive paths and 2) Time 1 controls. Paths in bold represent paths unique to this particular context while dashed paths are consistent across both sites.

Significant Site Differences

Notes. All estimates are standardized regression coefficients.

With regard to the cross-lagged relationships between personal and cultural identity, while maintaining the stationarity constraints, ethnic A/C at Time t negatively predicted confusion at Time t +1 only for participants in Los Angeles. Additionally, coherence more strongly predicted US A/C in Miami than in Los Angeles. For participants in Miami, ethnic A/C at Time 3 predicted optimism at Time 4. For participants in Los Angeles, coherence positively predicted self-esteem and negatively predicted cigarette use, confusion positively predicted unprotected sex and alcohol use, ethnic A/C negatively predicted unprotected sex, and US identity positively predicted Time 4 self-esteem.

Site-specific mediation

Because of these site differences, we repeated the tests of mediation separately for the Miami and Los Angeles sub-samples. Significant indirect effects ( p <.05) are displayed in Table 6 . Three sets of mediated effects emerged for adolescents in Miami: (1) invariant Time 1 and 2 ethnic A/C promoted Time 4 optimism, and was protective against aggression, through Time 3 coherence; (2) US A/C promoted optimism, and was protective against rule breaking and aggression, through coherence; and (3) coherence promoted optimism, and was protective against depressive symptoms, through US A/C. For the Los Angeles sample, four sets of mediated effects emerged: (1) ethnic A/C was protective against depressive symptoms, unprotected sex, and alcohol use, and promoted optimism and self-esteem, through confusion; (2) ethnic A/C promoted optimism, and was protective against aggression and cigarette use, through coherence; (3) US A/C promoted optimism and self-esteem, and was protective against aggression and cigarette use, through coherence; and (4) coherence was protective against unprotected sex through ethnic A/C.

Significant Site Differences in Indirect Effects on Psychosocial Functioning

Note: All estimates reported are standardized regression coefficients and all indirect paths are significant at p <.050.

This study examined the directionality between personal and cultural identity among recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents. We extend previous cross-sectional studies by evaluating the direct and indirect effects of personal and cultural identity on psychosocial functioning, and we evaluated site differences in these relationships.

Interplay Between Personal and Cultural Identity

Although cross-sectional studies have documented associations between cultural and personal identity, our findings clarify the direction of these effects. More specifically, not only did coherence predict greater ethnic and US A/C longitudinally, but ethnic and US A/C also predicted coherence. Our findings are consistent with arguments for bidirectional links between personal and cultural identity (e.g., Hitlin, 2003 ; Schwartz et al., 2008 ). However, the predictive effects of coherence on ethnic and US A/C were greater than the predictive effects of ethnic and US A/C on coherence. Thus, to some degree, understanding who one is and where one is going in life may serve to better orient youth towards understanding where they fit in relation to the cultural groups to which they belong. These findings support Schwartz, Montgomery, and Briones (2006) , who argued that a coherent sense of personal identity would anchor the person during the post-immigration cultural identity transition. Indeed, without the development of a coherent personal identity providing a sense of direction and stability, adolescents are likely to experience a sense of aimlessness, anomie, and distress ( Côté & Levine, 2002 ).

Additionally, three other important findings emerged from the cross-lagged analysis. First, results indicated non-significant longitudinal paths between coherence and confusion and between ethnic and US A/C. This lack of within-domain associations suggests that, although coherence and confusion, and US and ethnic A/C, may be conceptualized under personal and cultural identity respectively ( Schwartz et al., 2013 ), the processes within each identity domain appear to overlap considerably less than would be expected. That being said, results indicated significant concurrent correlations between coherence and confusion and ethnic and US A/C. Thus, the processes with each identity domain appear to be interrelated within time but do not predict one another across time. Second, confusion seemed to operate largely independent of the other three identity processes. Confusion appears to represent a maladaptive sense of disorganization that is not necessarily the opposite of coherence but that predicts negative psychosocial and health outcomes. Indeed, there is evidence that a fragmented and confused sense of identity portends low self-esteem, internalizing symptoms, externalizing problems, and health risk behaviors among members of various ethnic groups ( Oshri et al., 2014 ). Finally, while future studies are necessary to explore the directionality between personal and cultural identity across different development periods, as indicated by the stationarity results, these findings held across the first three waves of data, providing evidence for the generalizability of these findings over time.

Identity and Psychosocial Functioning

As part of our second aim, we evaluated the direct effects of personal and cultural identity on psychosocial functioning. Consistent with other empirical studies (e.g., Syed et al., 2013 ), confusion emerged as a negative predictor of self-esteem and optimism, and as a positive predictor of depressive symptoms, rule breaking, unprotected sex, and cigarette use. Coherence, on the other hand, positively predicted optimism and negatively predicted rule breaking and aggression. Regarding components of cultural identity, after controlling for personal identity, US A/C was associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms, whereas ethnic A/C did not significantly predict any indicators of psychosocial functioning. As a whole, the scarcity of direct effects of cultural identity is consistent with cross-sectional studies where personal identity relates to well-being and internalizing symptoms more strongly than cultural identity does ( Schwartz et al., 2009c ; Usborne & Taylor, 2010 ). Nonetheless, our longitudinal findings provide important theoretical and practical insights. Specifically, the small number of direct effects of cultural identity on outcomes, after controlling for personal identity, may indicate that an understanding of who one is and where one is going is more critical than understanding where one fits within one’s ethnic group and the context where one resides.

In addition to examining these direct effects, we evaluated the indirect effects of personal and cultural identity on psychosocial functioning. Both ethnic and US A/C positively indirectly predicted optimism and negatively predicted rule breaking and aggression through coherence. Thus, the effects of cultural identity on psychosocial functioning, which have been documented in numerous studies (for reviews, see Rivas-Drake et al., 2014 ; Umaña-Taylor, 2011 ), may operate indirectly via coherence. Although interventions may be wise to target both personal and cultural identity, it is worth noting that coherence predicted cultural identity more strongly than vice versa. Given the direct effects of coherence and confusion on nearly every outcome and the directional effects between coherence and cultural identity, despite the fact that cultural identity was a significant mediator, targeting personal identity directly may serve as the most optimal mechanism for promoting both cultural identity and positive psychosocial functioning. With that said, it is important to note that identity development is likely a complex process. Although the current findings point to the importance of personal identity over cultural identity, it is possible that cultural identity influences personal identity in implicit or indirect ways.

Exploring the Moderating Role of Site

Our results also indicated significant differences across sites. As a whole, cultural identity seemed to have played a larger role in Los Angeles than in Miami. Specifically, ethnic A/C, through confusion, predicted positive and negative psychosocial functioning and engagement in health risk behaviors. Through coherence, both ethnic and US A/C negatively predicted aggression and cigarette use. This finding highlights the role of cultural identity as a resource for personal identity development and points to key differences across contexts of reception. Given the protective role of ethnic A/C ( Umaña-Taylor, 2011 ), adolescents in Los Angeles, where Hispanics may be received more ambivalently ( Hayes-Bautista, 2004 ), might have less of an understanding of where they fit within their ethnic group and thus may experience a sense of confusion that inhibits personal identity development.

In Miami, results did not differ greatly from the findings from the sample as a whole. As such, although ethnic identity may inform adolescents’ sense of self and direction in life, in highly multicultural contexts it may not necessarily provide adolescents with the same amount of purpose and direction that it might in less welcoming contexts of reception. Given that research has indicated that the ethnic density of a community can impact awareness of one’s ethnicity ( Feinauer & Whiting, 2012 ), in the highly bicultural and welcoming context of Miami ( Stepick et al., 2003 ), where the majority of residents are first- or second-generation Hispanic immigrants ( US Census Bureau, 2011 ), Hispanic adolescents may be less likely to encounter discrimination and social exclusion. As a result, ethnic A/C may function more independently and may even be somewhat optional. It should be noted however, that for adolescents in Miami, ethnic A/C was found to negatively predict optimism, despite the non-significant yet positive bivariate correlation. Given that Hispanics represent the majority of Miami residents, one potential explanation for this counter-intuitive finding may be that more highly identified individuals are more likely to attribute negative social experiences to discrimination ( Hall & Carter, 2006 ; Sellers & Shelton, 2003 ).

In sum, given that ethnic and US identity predicted both coherence, and ethnic identity predicted confusion, which in turn predicted nearly every outcome, identity-based interventions might benefit by targeting both personal and cultural identity in contexts marked by ambivalence towards Hispanic adolescents. On the other hand, in ethnically dense, highly bicultural, and welcoming contexts, interventions might be better served by targeting personal identity directly. That being said, it is important to note that the interplay of identity processes may differ across country of origin or receiving community (which were confounded in our sample). Indeed, within the current sample, adolescents in Miami were largely of Cuban descent whereas those in Los Angeles were primarily of Mexican descent. Future studies should further explore the interplay of identity processes across context of reception and nativity.

Limitations and Future Directions

The present results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. All of our participants were recent immigrants residing in major metropolitan areas. It is possible that adolescents had already begun developing their personal identity in their country of origin, where cultural identity may have been less salient. While the results from the stationarity results provide evidence for the tenability of these findings over time, cultural identity may have only become salient following immigration. Thus, whether these findings can be generalized to immigrants who migrated before or after adolescence remains an empirical question. Given that some of the adolescents we sampled may still be in the process of exploring what it means to have both US and ethnic identities, future studies should also explore the interplay between personal and cultural identity domains. In addition, results may have been different in other cities or in “new receiving communities” where many Hispanic immigrants are settling (e.g., Kiang, Perreira, & Fuligni, 2011 ). Given that some of our findings differed between sites, and all of our participants were recruited from heavily Hispanic areas; future studies should examine the interplay between identity processes in less dense Hispanic communities. The current sample was also limited to individuals who could be reached and were not planning to move. Thus, findings may not generalize to adolescents whose families are more transient, such as seasonal workers. Finally, the high correlations between the affirmation and commitment subscales of the MEIM and AIM made it impossible to differentiate these two subscales, which represent two theoretically distinct processes ( Umaña-Taylor, Yazedjian, & Bámaca-Gómez, 2004 ). The lack of differentiation between affirmation and commitment may be due to recency of immigration, the developmental period under study, or problems with the measures. For recent immigrants and/or early adolescents, the process of understanding what ones’ ethnic and US membership means to them may be inextricably tied to their positive regard towards their cultural group membership. As such, it is necessary for future studies to uncouple these potential effects by using different instruments and by studying longer-term or older adolescents.

Our results suggest that personal and cultural identity influence one another in complex ways, and that at least some of this interplay differs according to the social context in which it is occurring. The ways in which personal and cultural identity impact psychosocial and risk-taking outcomes also appear to differ by context. Because we studied only two sites, we do not know which is the “rule” and which is the “exception.” It is therefore essential to conduct more work on personal identity, cultural identity, and their links with psychosocial and health outcomes across multiple contexts. Nonetheless, our findings hold important implications for the development and delivery of identity-focused interventions among recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents. By helping adolescents establish a coherent self-view and reconcile contradictory self-beliefs (cf. Harter, 2012 ), we may be able to improve their psychosocial functioning. We hope that this study will inspire more work in this direction.

1 Although we report the χ 2 value, we did not use it to gauge model fit because it tests a null hypothesis of perfect fit, which is rarely plausible with large samples or complex models ( Davey & Savla, 2010 ).

2 Although we report the Δχ 2 difference test, because it tests the null hypothesis that two paths or models are exactly equivalent ( Meade, Johnson, & Braddy, 2008 ), we did not rely on the Δχ 2 difference test in our interpretations.

- Achenbach TM, Newhouse PA, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Older Adult Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Adams GR, Marshall SK. A developmental social psychology of identity: Understanding the person-in-context. Journal of Adolescence. 1996; 19 :429–42. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Allison PD. Change scores as dependent variables in regression analysis. In: Clogg C, editor. Sociological Methodology. Oxford: Basil Blackwell; 1990. pp. 93–114. [ Google Scholar ]

- Azmitia M, Syed M, Radmacher K. Introduction and evidence from a longitudinal study of emerging adults. In: Azmitia M, Syed M, Radmacher K, editors. The intersections of personal and social identities: New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. Vol. 120. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2008. pp. 1–16. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychology research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986; 51 :1173–1182. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 1997; 46 :5–34. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beyers W, Seiffge-Krenke I. Does identity precede intimacy? Testing Erikson’s theory on romantic development in emerging adults of the 21st century. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2010; 25 :387–415. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bosma HA, Kunnen ES. Determinants and mechanisms in ego identity development: A review and synthesis. Developmental Review. 2001; 21 :39–66. [ Google Scholar ]

- Branch CW, Tayal P, Triplett C. The relationship of ethnic identity and ego identity status among adolescents and young adults. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2000; 24 :777–790. [ Google Scholar ]

- Coopersmith S. The self-esteem inventories. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1981. [ Google Scholar ]

- Côté JE. The role of identity capital in the transition to adulthood: The individualization thesis examined. Journal of Youth Studies. 2002; 5 (2):117–134. [ Google Scholar ]

- Côté JE, Levine CG. Identity formation, agency, and culture. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Crocetti E, Meeus W, Ritchie RA, Meca A, Schwartz SJ. Adolescent identity: The key to unraveling associations between family relationships and problem behaviors? In: Scheier LM, Hansen WB, editors. Parenting and Teen Drug Use. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. pp. 92–109. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davey A, Savla J. Statistical power analysis with missing data: A structural equation modeling approach. New York, NY: Routledge; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Edwards LM, Ong AD, Lopez SJ. Hope measurement in Mexican American youth. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2007; 29 :225–241. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ennis SR, Ríos-Vargas M, Albert NG. The Hispanic population: 2010. 2010 Census Briefs. Washington, DC: U. S. Census Bureau; 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Erikson EH. Childhood and society. New York: Norton; 1950. [ Google Scholar ]

- Feinauer E, Whiting EF. Examining the sociolinguistic context in schools and neighborhoods of pre-adolescent Latino students: Implications for ethnic identity. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education. 2012; 11 :52–74. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007; 18 :223–239. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hall SP, Carter RT. The relationship between racial identity, ethnic identity, and perceptions of racial discrimination in an Afro-Caribbean descent sample. Journal of Black Psychology. 2006; 32 :155–175. [ Google Scholar ]

- Harter S. The construction of the self: Developmental and sociocultural foundations. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hayes-Bautista D. La Nueva California: Latinos in the Golden State. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hitlin S. Values as the core of personal identity: Drawing links between two theories of self. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2003; 66 :118–137. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African American adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998; 279 :1529–1536. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2013: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research; 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Harris WA, Lowry R … Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014; 63 :1, e168. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kauermann G, Carroll RJ. A note on the efficiency of sandwich covariance matrix estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001; 96 :1387–1396. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiang L, Perreira KM, Fuligni AJ. Ethnic label use in adolescents from traditional and non-traditional immigrant communities. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011; 40 :719–729. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kroger J. Identity development: Adolescence through adulthood. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Light I. Deflecting immigration: Networks, markets, and regulation in Los Angeles. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Little TD. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lopez B, Schwartz SJ, Prado G, Huang S, Rothe EM, Wang W, Pantin H. Correlates of early alcohol and drug use in Hispanic adolescents: Examining the role of ADHD with comorbid conduct disorder, family, school, and peers. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008; 37 :820–832. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods. 2007; 12 (1):23–44. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McLaughlin KA, Hilt LM, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Racial/ethnic differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007; 35 :801–816. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meade AW, Johnson EC, Braddy PW. Power and sensitivity of alternative fit indices in tests of measurement invariance. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2008; 93 :568–592. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miville ML, Darlington P, Whitlock D, Mulligan T. Integrating identities: The relationships of racial, gender, and ego identities among white college students. Journal of College Student Development. 2005; 46 :157–175. [ Google Scholar ]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 5. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- Oshri A, Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Kwon JA, Des Rosiers SE, Baezconde-Garbanati L, … Szapocznik J. Bicultural stress, identity formation, and alcohol expectancies and misuse in Hispanic adolescents: A developmental approach. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014; 43 :2054–2068. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990; 108 :499–514. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Phinney JS, Ong AD. Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007; 54 :271–281. [ Google Scholar ]

- Portes A, Stepick A. City on the edge: The transformation of Miami. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977; 1 :385–401. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rivas-Drake D, Seaton EK, Markstrom CA, Quintana SM, Syed M, Lee RM … Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. Ethnic and racial identity in childhood and adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development. 2014; 85 :40–57. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, Romero A. The structure of ethnic identity in young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999; 19 :301–322. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rosenthal DA, Gurney RM, Moore SM. From trust to intimacy: A new inventory for examining Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1981; 10 :525–537. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rumbaut RG. Reaping what you sew: Immigration, youth, and reactive ethnicity. Applied Developmental Science. 2008; 22 :108–111. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schmitt DP, Allik J. Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in 53 nations: Exploring the universal and culture-specific features of global self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005; 89 :623–642. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwartz SJ, Benet-Martínez V, Knight GP, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Des Rosiers SE, … Szapocznik J. Effects of language of assessment on the measurement of acculturation: Measurement equivalence and cultural frame switching. Psychological Assessment. 2014a; 26 :100–114. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwartz SJ, Donnellan MB, Ravert RD, Luyckx K, Zamboanga BL. Identity development, personality, and well-being in adolescence and emerging adulthood: Theory, research, and recent advances. In: Weiner IB, Lerner RM, Easterbrooks A, Mistry J, editors. Handbook of psychology, vol. 6: Developmental psychology. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2013. pp. 339–364. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwartz SJ, Klimstra TA, Luyckx K, Hale WW, III, Frijns T, Oosterwegel A, … Meeus WHJ. Daily dynamics of personal identity and self-concept clarity. European Journal of Personality. 2011; 25 :373–385. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, Crocetti E. What have we learned since Schwartz (2001)? A reappraisal of the field. In: McLean K, Syed M, editors. Oxford handbook of identity development. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2014b. pp. 539–561. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwartz SJ, Montgomery MJ, Briones E. The role of identity in acculturation among immigrant people: Theoretical propositions, empirical questions, and applied recommendations. Human Development. 2006; 49 (1):1–30. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwartz SJ, Park IJK, Huynh Q, Zamboanga BL, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Lee RM, … Agocha VB. The American Identity Measure: Development and validation across ethnic group and immigrant generation. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2012; 12 :93–128. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Des Rosiers SE, Lorenzo-Blanco E, Zamboanga BL, Huang S, … Szapocznik J. Domains of acculturation and their effects on substance use and sexual behavior in recent Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Prevention Science. 2014c; 15 :385–396. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Lorenzo-Blanco E, Des Rosiers SE, Villamar JA, Soto DW, … Szapocznik J. Perceived context of reception among recent Hispanic immigrants: Conceptualization, instrument development, and preliminary validation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2015; 20 :1–14. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Wang W, Olthuis JV. Measuring identity from an Eriksonian perspective: Two sides of the same coin? Journal of Personality Assessment. 2009b; 91 :143–154. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]