Writing Therapy: How to Write and Journal Therapeutically

Of course, the answer to that question will be “yes” for everyone!

We all fall on hard times, and we all struggle to get back to our equilibrium.

For some, getting back to equilibrium can involve seeing a therapist. For others, it could be starting a new job or moving to a new place. For some of the more literary-minded or creative folks, getting better can begin with art.

There are many ways to incorporate art into spiritual healing and emotional growth, including drawing, painting, listening to music, or dancing. These methods can be great for artistic people, but there are also creative and expressive ways to dig yourself out of a rut that don’t require any special artistic talents.

One such method is writing therapy. You don’t need to be a prolific writer, or even a writer at all, to benefit from writing therapy. All you need is a piece of paper, a pen, and the motivation to write.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values and self-compassion and give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students or employees.

This Article Contains:

- What Is Writing Therapy?

Benefits of Writing Therapy

How to: journaling for therapy, writing ideas & journal prompts, exercises and ideas to help you get started, a take-home message, what is writing therapy.

Writing therapy, also known as journal therapy, is exactly what it sounds like: writing (often in a journal) for therapeutic benefits.

Writing therapy is a low-cost, easily accessible, and versatile form of therapy . It can be done individually, with just a person and a pen, or guided by a mental health professional. It can also be practiced in a group, with group discussions focusing on writing. It can even be added as a supplement to another form of therapy.

Whatever the format, writing therapy can help the individual propel their personal growth , practice creative expression, and feel a sense of empowerment and control over their life (Adams, n.d.).

It’s easy to see the potential of therapeutic writing. After all, poets and storytellers throughout the ages have captured and described the cathartic experience of putting pen to paper. Great literature from such poets and storytellers makes it tempting to believe that powerful healing and personal growth are but a few moments of scribbling away.

However, while writing therapy seems as simple as writing in a journal , there’s a little more to it.

Writing therapy differs from simply keeping a journal or diary in three major ways (Farooqui, 2016):

- Writing in a diary or journal is usually free-form, where the writer jots down whatever pops into their head. Therapeutic writing is typically more directed and often based on specific prompts or exercises guided by a professional.

- Writing in a diary or journal may focus on recording events as they occur, while writing therapy is often focused on more meta-analytical processes: thinking about, interacting with, and analyzing the events, thoughts, and feelings that the writer writes down.

- Keeping a diary or journal is an inherently personal and individual experience, while journal therapy is generally led by a licensed mental health professional.

While the process of writing therapy differs from simple journaling in these three main ways, there is also another big difference between the two practices in terms of outcomes.

These are certainly not trivial benefits, but the potential benefits of writing therapy reach further and deeper than simply writing in a diary.

For individuals who have experienced a traumatic or extremely stressful event, expressive writing guided purposefully toward specific topics can have a significant healing effect. In fact, participants in a study who wrote about their most traumatic experiences for 15 minutes, four days in a row, experienced better health outcomes up to four months than those who were instructed to write about neutral topics (Baikie & Wilhelm, 2005).

Another study tested the same writing exercise on over 100 asthma and rheumatoid arthritis patients, with similar results. The participants who wrote about the most stressful event of their lives experienced better health evaluations related to their illness than the control group, who wrote about emotionally neutral topics (Smyth et al., 1999).

Expressive writing may even improve immune system functioning, although the writing practice may need to be sustained for the health benefits to continue (Murray, 2002).

In addition to these more concrete benefits, regular therapeutic writing can help the writer find meaning in their experiences, view things from a new perspective, and see the silver linings in their most stressful or negative experiences (Murray, 2002). It can also lead to important insights about yourself and your environment that may be difficult to determine without focused writing (Tartakovsky, 2015).

Overall, writing therapy has proven effective for different conditions and mental illnesses, including (Farooqui, 2016):

- Post-traumatic stress

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder

- Grief and loss

- Chronic illness issues

- Substance abuse

- Eating disorders

- Interpersonal relationship issues

- Communication skill issues

- Low self-esteem

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

There are many ways to begin writing for therapeutic purposes.

If you are working with a mental health professional, they may provide you with directions to begin journaling for therapy.

While true writing therapy would be conducted with the help of a licensed mental health professional, you may be interested in trying the practice on your own to explore some of the potential benefits to your wellbeing. If so, here there are some good tips to get you started.

First, think about how to set yourself up for success:

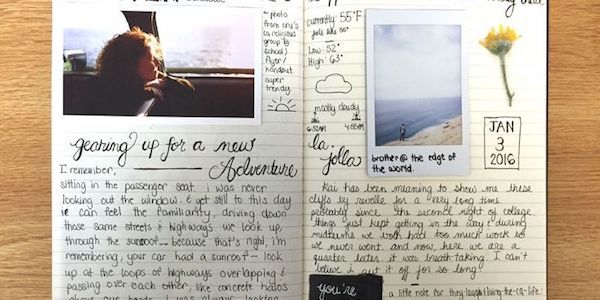

- Use whichever format works best for you, whether it’s a classic journal, a cheap notebook, an online journaling program, or a blog.

- If it makes you more interested in writing, decorate or personalize your journal/notebook/blog.

- Set a goal to write for a certain amount of time each day.

- Decide ahead of time when and/or where you will write each day.

- Consider what makes you want to write in the first place. This could be your first entry in your journal.

Next, follow the five steps to WRITE (Adams, n.d.):

- W – What do you want to write about? Name it.

- R – Review or reflect on your topic. Close your eyes, take deep breaths, and focus.

- I – Investigate your thoughts and feelings. Just start writing and keep writing.

- T – Time yourself. Write for five to 15 minutes straight.

- E – Exit “smart” by re-reading what you’ve written and reflecting on it with one or two sentences

Finally, keep the following in mind while you are journaling (Howes, 2011):

- It’s okay to write only a few words, and it’s okay to write several pages. Write at your own pace.

- Don’t worry about what to write about. Just focus on taking the time to write and giving it your full attention.

- Don’t worry about how well you write. The important thing is to write down what makes sense and comes naturally to you.

- Remember that no-one else needs to read what you’ve written. This will help you write authentically and avoid “putting on a show.”

It might be difficult to get started, but the first step is always the hardest! Once you’ve started journaling, try one of the following ideas or prompts to keep yourself engaged.

Here are five writing exercises designed for dealing with pain (Abundance No Limits, n.d.):

- Write a letter to yourself

- Write letters to others

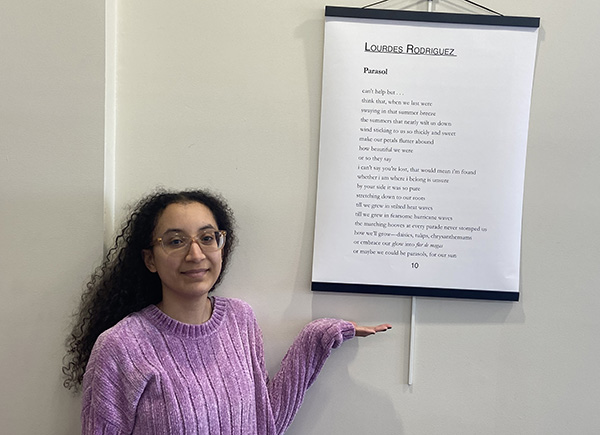

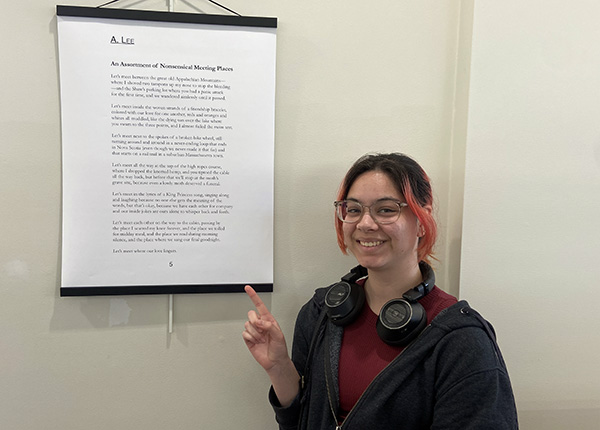

- Write a poem

- Free write (just write everything and anything that comes to mind)

- Mind map (draw mind maps with your main problem in the middle and branches representing different aspects of your problem)

If those ideas don’t get your juices flowing, try these prompts (Farooqui, 2016):

- Journal with photographs – Choose a personal photo and use your journal to answer questions like “What do you feel when you look at these photos?” and “What do you want to say to the people, places, or things in these photos?”

- Timed journal entries – Decide on a topic and set a timer for 10 or 15 minutes to write continuously.

- Sentence stems – These prompts are the beginnings of sentences that encourage meaningful writing, such as “The thing I am most worried about is…” “I have trouble sleeping when…” and “My happiest memory is…”

- List of 100 – These ideas encourage the writer to create lists of 100 based on prompts like “100 things that make me sad” “100 reasons to wake up in the morning,” and “100 things I love.”

Tartakovsky (2014) provides a handy list of 30 prompts, including:

- My favorite way to spend the day is…

- If I could talk to my teenage self, the one thing I would say is…

- Make a list of 30 things that make you smile.

- The words I’d like to live by are…

- I really wish others knew this about me…

- What always brings tears to your eyes?

- Using 10 words, describe yourself.

- Write a list of questions to which you urgently need answers.

If you’re still on the lookout for more prompts, try the lists outlined here .

6 Ways to process your feelings in writing – Therapy in a Nutshell

As great as the benefits of therapeutic journaling sound, it can be difficult to get started. After all, it can be a challenge to start even the most basic of good habits!

If you’re wondering how to begin, read on for some tips and exercises to help you start your regular writing habit (Hills, n.d.).

- Start writing about where you are in your life at this moment.

- For five to 10 minutes just start writing in a “stream of consciousness.”

- Start a dialogue with your inner child by writing in your nondominant hand.

- Cultivate an attitude of gratitude by maintaining a daily list of things you appreciate, including uplifting quotes .

- Start a journal of self-portraits.

- Keep a nature diary to connect with the natural world.

- Maintain a log of successes.

- Keep a log or playlist of your favorite songs.

- If there’s something you are struggling with or an event that’s disturbing you, write about it in the third person.

If you’re still having a tough time getting started, consider trying a “mind dump.” This is a quick exercise that can help you get a jump start on therapeutic writing.

Researcher and writer Gillie Bolton suggests simply writing for six minutes (Pollard, 2002). Don’t pay attention to grammar, spelling, style, syntax, or fixing typos – just write. Once you have “dumped,” you can focus on a theme. The theme should be something concrete, like something from your childhood with personal value.

This exercise can help you ensure that your therapeutic journal entries go deeper than superficial diary or journal entries.

More prompts, exercises, and ideas to help you get started can be found by following this link .

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

In this piece, we went over what writing therapy is, how to do it, and how it can benefit you and/or your clients. I hope you learned something new from this piece, and I hope you will keep writing therapy in mind as a potential exercise.

Have you ever tried writing therapy? Would you try writing therapy? How do you think it would benefit you? Let us know your thoughts in the comments!

Thanks for reading, and happy writing!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- Abundance No limits. (n.d.). 5 Writing therapy exercises that can ease your pain . Author. Retrieved from https://www.abundancenolimits.com/writing-therapy-exercises/.

- Adams, K. (n.d.). It’s easy to W.R.I.T.E . Center for Journal Therapy . Retrieved from https://journaltherapy.com/journal-cafe-3/journal-course/

- Baikie, K. A., & Wilhelm, K. (2005). Emotional and physical health benefits of expressive writing. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 11(5) , 338-346.

- Farooqui, A. Z. (2016). Journal therapy . Good Therapy . Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/learn-about-therapy/types/journal-therapy

- Hills, L. (n.d.). 10 journaling tips to help you heal, grow, and thrive . Tiny Buddha . Retrieved from https://tinybuddha.com/blog/10-journaling-tips-to-help-you-heal-grow-and-thrive/

- Howes, R. (2011, January 26). Journaling in therapy . Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/in-therapy/201101/journaling-in-therapy.

- Murray, B. (2002). Writing to heal. Monitor, 33(6), 54. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/monitor/jun02/writing.aspx

- Pollard, J. (2002). As easy as ABC . The Guardian . Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2002/jul/28/shopping

- Smyth, J. M., Stone, A. A., Hurewitz, A., & Kaell, A. (1999). Effects of writing about stressful experiences on symptom reduction in patients with asthma or rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 281 , 1304-1309.

- Tartakovsky, M. (2014). 30 journaling prompts for self-reflection and self-discovery . Psych Central . Retrieved from https://psychcentral.com/blog/archives/2014/09/27/30-journaling-prompts-for-self-reflection-and-self-discovery/

- Tartakovsky, M. (2015). The power of writing: 3 types of therapeutic writing . Psych Central . Retrieved from https://psychcentral.com/blog/archives/2015/01/19/the-power-of-writing-3-types-of-therapeutic-writing/

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Hello, Such an interesting article, thank you very much. I was wondering if there was a particular strategy in which writing down questions produced answers. I started doing just that: writing down doubts and questions, and I found that answers just came. It was like talking through the issues with someone else. Is there any research on that? Is this a known strategy?

Hi Michael,

That’s amazing that you’re finding answers are ‘arising’ for you in your writing. In meditative and mindfulness practices, this is often referred to as intuition, which points to a form of intelligence that goes beyond rationality and cognition. This is a fairly new area of research, but has been well-recognized by Eastern traditions for centuries. See here for a book chapter review: https://doi.org/10.4337/9780857936370.00029

As you’ve discovered, journaling can be incredibly valuable to put you in touch with this intuitive form of knowing in which solutions just come to you.

This also reminds me of something known as the rubber ducking technique, which programmers use to solve problems and debug code: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubber_duck_debugging

Anyway, hope that offers some food for thought!

– Nicole | Community Manager

I have never tried writing therapy, but I intend to. Its so much better than seeing the psychiatrist for my behavior issues, which nobody has even identified yet.

Hi great article, just wondering when it was originally posted as I wish to cite some of the text in my essay Many thanks

Glad you enjoyed the post. It was published on the 26th of October, 2017 🙂

Hope this helps!

Hi Courtney

I know you posted this blog a while ago but I’ve just found it and loved it. It articulated so clearly the benefits of writing therapy. One question – is there any research on whether it’s better to use pen and paper or Ian using a PC/typing just as good. I can write much faster and more fluently when I use a keyboard but wonder whether there is a benefit from the physical act of writing writing with a pen. Thanks.

Great question. The evidence isn’t entirely clear on this, but there’s a little work suggesting that writing by hand forces the mind to slow down and reflect more deeply on what’s being written (see this article ). Further, the process of writing uses parts of the brain involved in emotion, which may make writing by hand more effective for exploring your emotional experiences.

However, when it comes to writing therapy, the factor of personal preference seems critical! The issue of speed can be frustrating if your thoughts tend to come quickly. If you feel writing by hand introduces more frustration than benefits, that may be a sign to keep a digital journal instead.

Hope that helps!

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Humanistic Therapy: Unlocking Your Clients’ True Potential

Humanism recognizes the need of the individual to achieve meaning, purpose, and actualization in their lives (Rowan, 2016; Block, 2011). Humanistic therapy was born out [...]

Holistic Therapy: Healing Mind, Body, and Spirit

The term “holistic” in health care can be dated back to Hippocrates over 2,500 years ago (Relman, 1979). Hippocrates highlighted the importance of viewing individuals [...]

Trauma-Informed Therapy Explained (& 9 Techniques)

Trauma varies significantly in its effect on individuals. While some people may quickly recover from an adverse event, others might find their coping abilities profoundly [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (19)

- Positive Parenting (15)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (43)

- Resilience & Coping (37)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Tools Pack (PDF)

3 Positive CBT Exercises (PDF)

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Writing Can Help Us Heal from Trauma

- Deborah Siegel-Acevedo

Three prompts to get started.

Why does a writing intervention work? While it may seem counterintuitive that writing about negative experiences has a positive effect, some have posited that narrating the story of a past negative event or an ongoing anxiety “frees up” cognitive resources. Research suggests that trauma damages brain tissue, but that when people translate their emotional experience into words, they may be changing the way it is organized in the brain. This matters, both personally and professionally. In a moment still permeated with epic stress and loss, we need to call in all possible supports. So, what does this look like in practice, and how can you put this powerful tool into effect? The author offers three practices, with prompts, to get you started.

Even as we inoculate our bodies and seemingly move out of the pandemic, psychologically we are still moving through it. We owe it to ourselves — and our coworkers — to make space for processing this individual and collective trauma. A recent op-ed in the New York Times Sunday Review affirms what I, as a writer and professor of writing, have witnessed repeatedly, up close: expressive writing can heal us.

- Deborah Siegel-Acevedo is an author , TEDx speaker, and founder of Bold Voice Collaborative , an organization fostering growth, resilience, and community through storytelling for individuals and organizations. An adjunct faculty member at DePaul University’s College of Communication, her writing has appeared in venues including The Washington Post, The Guardian, and CNN.com.

Partner Center

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Use Writing Therapy to Release Negative Emotions and Trauma

Whether it’s lyrics or journaling—expression through writing can be cathartic

Ayana is the Associate Editor at Verywell Mind, where she aims to publish mental health content that is both engaging and of high quality.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/verywell-Ayana-Underwood1-b3c1567c2c4c4480b6eab25cabb974b1.jpg)

Yolanda Renteria, LPC, is a licensed therapist, somatic practitioner, national certified counselor, adjunct faculty professor, speaker specializing in the treatment of trauma and intergenerational trauma.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/YolandaRenteria_1000x1000_tight_crop-a646e61dbc3846718c632fa4f5f9c7e1.jpg)

Verywell / Julie Bang

- What to Know About Writing Therapy

The Major Benefits of Writing Therapy

- How to Get Started With Expressive Writing

Every Friday on The Verywell Mind Podcast , host Minaa B., a licensed social worker, mental health educator, and author of "Owning Our Struggles," interviews experts, wellness advocates, and individuals with lived experiences about community care and its impact on mental health.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts / Amazon Music

Putting pen to paper feels a bit like an anomaly in a world obsessed with texting, tweeting, and sliding into people’s DMs. But let’s try something different. The next time you’re in your Notes app, give your thumbs a break and grab a pen and piece of paper instead. If you don’t have any paper handy, grab that Starbucks receipt and start writing whatever you were about to type. See how it feels.

It might feel a bit awkward at first, especially if you haven’t had to physically write anything down in a long while. But as you keep writing, you may feel really engaged with the words you’re jotting down. Tapping letters on a screen isn’t the same as drawing out each letter of every word. Writing things down will inherently bond you to the words you write. And because of that, writing becomes quite powerful for the psyche . Aside from being a feel-good activity, writing can also let us process negative emotions and trauma in what turns out to be a pretty soul-cleansing experience.

In fact, singer/songwriter and season three winner of The Voice, Cassadee Pope , seconds this. Pope, who's been in the music industry since she was 11 years old, has been pretty open about her mental health struggles—from bad breakups to the emotional impact of her parent’s divorce. Pope told Minaa B., LMSW , host of The Verywell Mind Podcast, “I needed an outlet with everything that was happening with my family. So that was really what I leaned on most, was songwriting.”

Now, you don’t have to be a gifted songwriter to reap the benefits of writing, but let's talk about why writing can be so good for your mental health.

At a Glance

Writing can be a powerful therapeutic tool. Getting your thoughts down can help you understand them and process them more effectively than keeping them all in your head. People who use writing therapy report better overall mood and fewer depressive symptoms. If you’re struggling with a mental health condition and need to vent your frustrations—consider making a journal your new BFF.

What to Know About Writing Therapy (Write This Down)

Writing therapy (aka emotional disclosure or expressive writing) is pretty much exactly what it sounds like. It involves using writing of any kind, like creative writing, freewriting, and poetry, as a therapeutic tool. Writing therapy can be especially for those who are more withdrawn or have trouble opening up to others.

Writing therapy can be so beneficial to our mental health because it’s basically a form of venting. You know how good it feels to come home after a long day of work and go on and on about how much you dislike that one coworker for a reason you can’t even put your finger on. Or when you spill all of your dating frustrations to your bestie over the phone. It’s a nice release of stress. You can release stress in a similar way when you write, too. Just pretend that piece of paper is your therapist, closest confidante, or even yourself.

No one else has to know whatever you choose to jot down (or rage-write about). Your journal or diary is your personal safe haven, and your innermost thoughts are safe on those pages.

Research shows that writing about painful experiences can even improve your immune system. Getting all of your thoughts out on paper is a big stress reliever. It’s also known that trying to suppress negative emotions can be detrimental to your overall well-being, so verbal release may only help you in the long run. Another advantage of writing therapy is that it gives your emotions and thoughts some structure. For instance, my therapist knows I love writing—especially writing poetry. So, when I was dealing with a particularly traumatic time in my life, she told me that my next few homework assignments would be to write poetry about my feelings. Because poetry is a form of creative writing, I had to really think about the diction and imagery I wanted to convey in the poems.

As a result, I really had to unpack my feelings so that my poem would paint a clear picture of what I was going through. I worked on the poem each night before bed and had it ready for my next weekly session.

The next day, I hopped online to meet with my therapist and tell her I had completed my assignment. In response, she asked me to read it aloud. What?! I quickly grew nervous since I was not expecting that. But, considering she’s never led me astray, I reluctantly recited my poem. It was an emotional experience, and my voice audibly cracked a few times, but it felt really good—euphoric, even. So when Pope says that singing her lyrics is "cathartic," I completely get it. She says her singing can be a bit “disarming” because “ I’m believing every word so intensely, and I feel them so intensely.”

So, not only does writing release some deep-seated feelings, orating them breathes life into them. There’s this particularly beautiful Chinese proverb that says: ‘I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I write and I understand.’ Once our thoughts are written down, we can see them in front of us, through this practice they become real. Then, we can dig in and unpack what it all means to us.

Other Benefits of Writing Therapy

If you’re still not convinced about the power of writing, here are some other amazing benefits of writing to take note of (pun intended):

- Lowered blood pressure

- Reduced anxiety and depression symptoms

- Improved cognition

- Increased antibody production

- Better overall mood

Ready to Get Started With Expressive Writing?—Here’s How

The great thing about writing is that it can be about anything you want. There are zero restrictions on what you can say. If you’ve had an upsetting experience or need to release some frustrations about daily stressors, try writing about it.

Pope talks about how she’s been using songwriting to get more authentic about her life as of late. In fact, she was kind enough to dish on the details about a new song of hers that’s set to release soon titled “Three of Us.” In this track, she details what it’s like being the “third wheel” when you’re in a relationship with someone who’s dealing with a substance use disorder : “It's about me, you, and the drugs.” In describing the lyrics, she says, “It's probably the most revealing song I've ever released.”

Now, if you’ve already got an experience you want to write about, feel free to get started when you’re alone and in a private space. But if you don’t know where to start, here are some prompts to start flexing your writing muscles.

Writing Prompts to Help You Get to Know Yourself Better

When you’re ready, get something to write with and a blank sheet of paper. Here are some prompts you can use to get started:

- What does the perfect day look like for you? Think about the activities you’d engage in and who you would be spending your time with. Try engaging your five senses to dive deep into your imagination.

- Write a story about the last time you were embarrassed. This time, reframe the experience into a positive one where you learn something new about yourself.

- Think about the best piece of advice you've ever received from someone. How has it helped to shape your life?

- Write a song or a poem about what it’s like to eat your favorite dessert. Consider the flavors, textures, and how you feel when you eat this specific treat. Where are you eating it? Did someone special make it for you, or did you make it yourself?

- What does self-love really mean to you? Who taught you what loving yourself looks like? What have you learned to embrace about yourself?

- If you’ve experienced a painful event, free-write about it. Don’t worry about grammar, spelling, or legibility—just write whatever comes to mind. You can even draw if that helps.

These writing prompts should get you more comfortable with expressing your feelings. Once you make sense of your own experiences, you might be ready to share them with friends, significant others, and other people you trust. If you have a therapist or plan to start therapy, you’ll already have some material to share that you can explore in the session.

When you connect through storytelling, you begin to strengthen your support network. Pope shared how much she leaned on her friends after a bad breakup. “ If you have community, lean into it and don't be afraid that someone's gonna judge you if you made a mistake or a bad decision, a poor decision, don't be afraid of that. It's so much more healthy to just let it out,” she says.

Pope also cautions that doing this can also reveal the people who accept you just as you are—flaws included: “ If somebody judges you or tries to make you feel bad about it, then OK, great. That one person is not a safe space for you.”

What This Means For You

If you’re uncomfortable opening up to your friends this way, that’s perfectly fine. Never feel pressured to share some uncomfortable thoughts or experiences. You can keep them to yourself in your journal or reserve them all for your therapist.

Writing is a good place to start when you want to better understand who you are and how your experiences have affected you. If you’re struggling with processing your emotions and feel that you need someone to talk to, consider seeing a mental health professional.

Mugerwa S, Holden JD. Writing therapy: a new tool for general practice? . Br J Gen Pract . 2012;62(605):661-663. doi:10.3399/bjgp12X659457

American Psychological Association. Writing to heal .

Krpan KM, Kross E, Berman MG, Deldin PJ, Askren MK, Jonides J. An everyday activity as a treatment for depression: the benefits of expressive writing for people diagnosed with major depressive disorder . J Affect Disord . 2013;150(3):1148-1151. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.065

By Ayana Underwood Ayana is the Associate Editor at Verywell Mind, where she aims to publish mental health content that is both engaging and of high quality.

join the list

Join 7,000+ ambitious women ready to redefine success and put an end to toxic hustle culture. , get on the list.

Sign up to get productivity, intentional living and self-care tips so you can go from "busy" to "present" and tap into a slower life that prioritizes your energy and peace

Ultimate Guide to Creative Writing Therapy (with Writing Therapy Prompts)

March 22, 2023

I believe that taking care of yourself should always come first. So, my job is to help you create a slow and mindful life that aligns with your values and goals so you can finally go from a state of constantly doing to peacefully being.

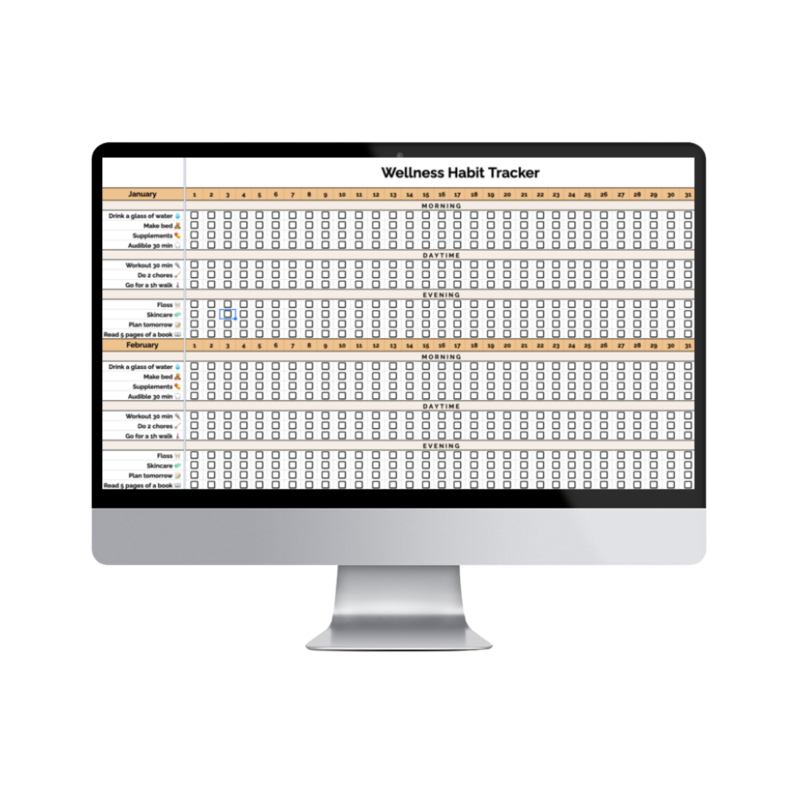

5-Minute Wellness Habit Tracker That *Actually* Works

This super customizable and in-depth wellness habit tracker is specifically designed to help you protect your time, have blissful boundaries, achieve your goals, and be extra productive every day so you can finally go from overwhelmed to organized in just 5 minutes/day.

join the movement

Sign up to get productivity, intentional living and self-care tips so you can tap into a slower life and go from constantly doing to peacefully being.

Creative writing therapy, or therapeutic writing is a form of therapeutic intervention that uses writing as the tool to explore and express your thoughts, feelings and emotions. It’s also known as journal therapy – and it’s essentially the art of writing in a journal to heal yourself.

Writing therapy can be a useful tool for people who struggle with mental health, have experienced trauma or grief, or are simply looking for a creative outlet to process their thoughts and feelings. Today we’re going to explore what creative writing therapy is, how it works, and the potential benefits of writing therapy. We’ll also share writing therapy prompts to help you get started and explore writing therapy today.

Please keep in mind that there is no true substitute for seeing a licensed therapist, and if you feel like you could benefit from talking to someone and getting help with what you’re going through – you’re not alone! There are tons of incredible therapists out there to help you. Here at Made with Lemons we’re big advocates for therapy and if you’d like a more inside scoop to our own journey with therapy, join On Your Terms . It’s a wellness newsletter that shares a more inside look to our own wellness journey as well as tools to help you along yours. Learn more about On Your Terms here.

Get productivity, intentional living and self-care tips so you can go from “busy” to “present” and show up as your best self.

What is Creative Writing Therapy?

Writing therapy, also known as therapeutic writing, is a form of creative and expressive therapy that involves writing about your personal experiences, thoughts and feelings. It can take many forms, including journaling, poetry, creative writing, letter writing, or memoirs. Writing therapy can be done individually or in a group setting. It can also be facilitated by a therapist, counselor or writing coach.

The purpose of creative writing therapy is to help you express and process your emotions in a safe and supportive environment. It’s helpful to be able to write out your thoughts and feelings that might be hard to articulate in other ways.

You might also see therapeutic writing used to help explore issues that are difficult to discuss in traditionally talking therapy sessions. And when your therapist invites you to try writing therapy, it’s also used in conjunction with other forms of therapy, such as trauma-focused therapy, to enhance its effectiveness.

An example of creative writing therapy could be writing a letter to a person who hurt you, and then shredding or burning the letter to release some of the hurt and anger.

How Does Therapeutic Writing Work?

Writing therapy works by allowing individuals to express their thoughts and feelings in a way that is both private and creative. The act of writing can help you organize your thoughts and gain clarity on your emotions. Writing can also be a way to release pent-up emotions and relieve stress.

For example, if you’re feeling stressed after a long day of work, taking a few moments to write down what’s stressing you out and allowing yourself to let it go, can help you have a calm and more relaxing evening.

Writing therapy should be a truly non judgemental space. It’s a time to write without worrying about grammar, punctuation, or spelling. The goal here is to let words flow freely, without judgment or criticism. Creative writing therapy sessions can be structured or unstructured, and sometimes it’s helpful to use prompts or exercises to help you get started. (i.e. what in your life is bringing you the most anxiety, or writing a letter to your friend to express ___________ hurt you when they said that.)

Oftentimes we find it easier to write about our hurt, our pain and the experiences that caused that, as opposed to opening up to talk about those things. In this way, writing can be a way to explore and process complex emotions such as grief or anger in a safe and supportive environment, where no one can get hurt further by what’s being felt and expressed.

Potential Benefits of Writing Therapy

Now let’s talk about some of the benefits of therapeutic writing.

Improved mental health

Writing therapy can be a tool that helps you manage symptoms of depression, anxiety and other mental health conditions. You can use journaling therapy to express and process difficult emotions, which over time can lead to improved mental regulation and a better sense of control over your thoughts and feelings.

Increased self-awareness

Creative writing therapy can help you gain a better insight into your thoughts and behaviors. By reflecting on your experiences through writing, you can start to identify patterns and gain an understanding of yourself.

Stress relief

Therapeutic writing can be a way to relieve stress and reduce anxiety. Writing is often cathartic, allowing you to release pent-up emotions and start to feel relief from things that would otherwise feel overwhelming.

Improved communication skills

Journal therapy can also help you improve your overall communication skills. When you practice expressing yourself through writing, you can develop more confidence to communicate more effectively in both your personal and professional relationships. In essence, writing your feelings can help you communicate them better when needed.

Increased creativity

Lastly, creative writing therapy can also be a way to tap into your creativity and imagination. We talk a lot about your inner child around here, and journal therapy can be another helpful way you can interact with your inner child. Through writing you can explore new ideas and perspectives, leading to your own personal growth.

How to try Creative Writing Therapy Today

Now let’s talk about how you can try therapeutic writing for yourself today. These tips are going to help you get started with writing therapy from home, as a personal activity to help heal yourself.

Set aside dedicated time for writing therapy

Like most self improvement and self care techniques, it helps to set aside a dedicated time to write regularly. We know this can be a challenging task, especially if you’re struggling with mental health issues or challenges in your life. A good place to start is to set aside a few minutes each evening to write and decompress from your day. It can be just 2 minutes before bed. Remember, therapeutic writing is a non judgemental activity, so the amount of time you dedicate isn’t important, it’s just important to show up for yourself.

Find a quiet and comfortable space

Find a place that’s quiet and comfortable, and where you can write without interruptions. Some people find it helpful to create a writing ritual, such as lighting a candle or playing soft music to create a sense of calm and focus. Find what works for you, in a space where you can be alone for a few minutes.

Choose a writing therapy prompt or topic

At the end of this guide we’re going to share writing therapy prompts to help you explore creative writing therapy and give you a starting point. You can also talk to your therapist to get prompts, or find some online. Prompts can be general, such as “write about what makes you grateful or happy”, while others can be more specific, such as “write about a time that you felt overwhelmed.”

Write freely and without judgment

The most important thing about writing therapy is to write freely, without judging yourself. Allow yourself to write without worrying about grammar, punctuation or spelling. Don’t put a time limit on your writing, or feel like you have to write a certain number of words or pages. The goal here is to allow your thoughts and emotions to flow freely without any judgment at all.

Write honestly and openly

Along with being judgment free, it’s also so important that you write honestly and openly. Writing therapy is a space for honesty and openness. This space is created for you to share your thoughts and emotions, even if they're difficult or uncomfortable to confront. Just be open to exploring them, and remember that you don’t have to share this with anyone, so it’s a space where you can be fully honest with yourself.

Reflect on your writing

After writing, you can take a few moments to reflect on what you have written. It might even be helpful to come back to what you have written at another time, when you have a clear head or have left the emotions behind. This can help you consider the emotions and patterns that you have expressed. Doing this reflection can help you gain more insight into your thinking patterns and emotions for future sessions.

Consider sharing your writing with a therapist or counselor

Lastly, consider sharing your writing with a therapist or counselor. They can help you process emotions and gain a deeper understanding of yourself. Sharing your writing can also help you feel less alone in your struggles and provide important validation for your experiences.

20 Writing Therapy Prompts

- When do I feel the most like myself?

- How do I feel at this moment?

- What do I need more of in my life?

- What do I look forward to every day?

- What is a lesson that I had to learn recently?

- Based on my daily routine, where do I see myself in 5 years?

- What don’t I regret?

- What would make me happy right now?

- What has been the hardest thing to forgive myself for?

- What’s bothering me? And why?

- What do I love about myself?

- What are my priorities right now?

- What does my ideal day look like?

- What does my ideal morning look like? Evening?

- Make a list of 30 things that make you smile

- Make a gratitude list

- The words I’d like to live by are…

- I really wish others knew this about me…

- What always brings tears to my eyes?

- What do I need to get off my chest today?

Creative writing therapy can be a powerful tool for exploring and processing thoughts and emotions. When you set aside a dedicated time to write, and create a safe and supportive space for yourself, you can gain insight into your emotions and develop better tools to manage them. With practice and commitment, writing therapy can become a habit for your self care routine.

If you’d like to build the habit of writing therapy in your own life, then we’d like to invite you to download our habit tracker. It’s super easy to use, beautifully designed and completely free. All you need is a google account to access it. Grab a copy of our habit tracker here.

+ show Comments

- Hide Comments

add a comment

How to Create the Perfect Anti “That Girl” Morning Routine in Less Than One Hour »

« Revamp Your Life This Spring: The Ultimate Spring Reset Guide

Previous Post

back to blog home

How To Make Your Self Care Plans Align With Your Business Goals

Summer of Self-Care (60 Solo Date Ideas for Summer 2023)

How to Live a Sober Life (70 Ways to Practice Sober Self-Care)

A Complete Guide to Mushroom Microdosing

Self Love Ideas Based on Your Love Language

Glowy Skincare Routine: How to Get Naturally Glowing Skin From Home

so hot right now

This super customizable and in-depth wellness habit tracker is designed to help you protect your time, achieve your goals, and be more productive every day so you can finally go from overwhelmed to organized in just 5 minutes.

Wellness Habit Tracker

Ready to success and put an end to toxic hustle culture?

Get productivity, intentional living and self-care tips so you can go from "busy" to "present" and show up as your best self in life and business in this weekly newsletter.

Do you sleep 7-8+ hours but feel exhausted? Does resting feel selfish and unproductive? Get your free download to find out about the 7 types of rest and why you'll burnout without it.

7 Types of Rest You Need

FREE DOWNLOAD

3 Steps to Avoid Burnout & Create More Intentionality in Your Life and Business

free class!

Come say hi on the 'gram!

apply for 1:1 coaching

GET my newsletter

© MADE WITH LEMONS 2020- 2024 | Privacy Policy | Terms & CONDITIONS | Design by Tonic

London-based multi-passionate Lifestyle designer for busy female entrepreneurs, lover of Golden Retrievers, skin care obsessed, & proud plant mom.

Learn from me

@onyourtermsco

Your Information is 100% Secure And Will Never Be Shared With Anyone. You can unsubscribe at any time. By submitting this form you confirm you have read our privacy policy and you accept our terms and conditions

Join the anti-hustle movement!

Your Information is 100% Secure And Will Never Be Shared With Anyone. You can unsubscribe at any time.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Writing Technique Across Psychotherapies—From Traditional Expressive Writing to New Positive Psychology Interventions: A Narrative Review

Chiara ruini.

Department of Psychology, University of Bologna, Viale Berti Pichat 5, 40127 Bologna, Italy

Cristina C. Mortara

Writing Therapy (WT) is defined as a process of investigation about personal thoughts and feelings using the act of writing as an instrument, with the aim of promoting self-healing and personal growth. WT has been integrated in specific psychotherapies with the aim of treating specific mental disorders (PTSD, depression, etc.). More recently, WT has been included in several Positive Interventions (PI) as a useful tool to promote psychological well-being. This narrative review was conducted by searching on scientific databases and analyzing essential studies, academic books and journal articles where writing therapy was applied. The aim of this review is to describe and summarize the use of WT across various psychotherapies, from the traditional applications as expressive writing, or guided autobiography, to the phenomenological-existential approach (Logotherapy) and, more recently, to the use of WT within Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Finally, the novel applications of writing techniques from a positive psychology perspective will be analyzed. Accordingly, the applications of WT for promoting forgiveness, gratitude, wisdom and other positive dimensions will be illustrated. The results of this review show that WT yield therapeutic effects on symptoms and distress, but it also promotes psychological well-being. The use of writing can be a standalone treatment or it can be easily integrated as supplement in other therapeutic approaches. This review might help clinician and counsellors to apply the simple instrument of writing to promote insight, healing and well-being in clients, according to their specific clinical needs and therapeutic goals.

Introduction

Writing therapy can be defined as the process in which the client uses writing as a means to express and reflect on oneself, whether self- generated or suggested by a therapist/researcher (Wright & Chung, 2001 ). It is characterized by the use of writing as a tool of healing and personal growth. From the first investigations of James Pennebaker (Pennebaker & Beall, 1986 ), writing therapy has shown therapeutic effects in the elaboration of traumatic events. In recent years, expressive and creative writing was found to have beneficial effects on physical and psychological health (Nicholls, 2009 ).

Currently, clinicians have moved from a distress-oriented approach to an educational approach, where writing is used to build personal identity and meaning through the use of autobiographical writing (Hunt, 2010 ). In this vein, autobiographical writing is becoming a widespread technique, which allows people to recall their life path and to better understand the present situation (McAdams, 2008 ). Moreover, it is observed that individuals often tend to report significant life events (positive or negative) in personal journals (Van Deurzen, 2012 ). Keeping a journal is a way of writing spontaneously: it can be considered a sort of logbook where thoughts, ideas, reflections, self-evaluation and self -assurances are recorded in a private way. Journaling is different from therapeutic writing the writer does not receive specific instructions on the contents and methodologies to be followed when writing, as it happens in therapeutic writing. Nowadays journaling can be done also through online blogs and social network (Facebook). In doing so, a private and spontaneous journal can be shared publically.

Writing techniques are often implemented into talking therapies, since both processes (talking and writing) favor the organization, acceptance and the integration of memories in the process of self-understanding (Lyubomirsky et al., 2006 ). However, expressive writing has been found to be beneficial also as a “stand alone” technique for the treatment of depressive, anxious and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms (Reinhold et al., 2018 ). In a recent study, it was found that enhanced expressive writing (i.e., writing with scheduled contacts with a therapist) was as effective as traditional psychotherapy for the treatment of traumatized patients. Expressive writing without additional talking with a therapist was found to be only slightly inferior. Authors concluded that expressive writing could provide a useful tool to promote mental health with only a minimal contact with therapist (Gerger et al., 2021 ). Another recent investigation (Allen et al., 2020 ) highlighted that the beneficial effect of writing techniques may be moderated by individual differences, such as personality trait and dysfunctional attitude (i.e., high level of trait anxiety, avoidance and social inhibition). In these cases, therapeutic writing may be even more beneficial since it avoids the interactions with the therapist or other clients.

This article aims to illustrate and summarize the main psychotherapeutic interventions where writing therapy plays an important role in the healing process. For instance, a common application is the use of a diary in standard Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for promoting patients’ self observation (Butler et al., 2006 ). Similarly, other traditional psychotherapies use writing in their therapeutic process: from the pivotal application of writing to understand and overcome traumatic experiences, to the phenomenological-existential approach where writing has the function of giving meaning to events and of clarifying life goals (King, 2001 ), to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, where writing facilitates the process of thought-defusion (Hayes, 2004 ). This review will also address the novel applications of writing technique to new a psychotherapeutic context: positive psychotherapy where the tool of writing is employed in many effective techniques (i.e. writing gratitude or forgiveness letters). Smyth ( 1998 ) reviewed 13 case-controlled writing therapy studies that showed the positive influence of writing techniques on psychological well-being. The benefits produced in writing activity (self regulation, clarifying life goals, gaining insight, finding meaning, getting a different point of view) can be described under the rubric of psychological and emotional well-being. In accordance with Fredrickson’s Broaden and Build Theory of Positive Emotions ( 2004 ), writing may foster positive emotions since putting feelings and thoughts into words widens scope of attention, opens up to different points of view and allows the mind to be more flexible (King, 2001 ).

Finally, we will describe and explore new contexts where writing activities currently take place: the web and social networks. We will underline important clinical implications for these new applications of writing activities.

Traditional Applications of Writing Techniques

Clinical applications of writing therapy include the method of expressive writing created by Pennebaker (Pennebaker & Beall, 1986 ); the autobiography; and the use of a diary in traditional Cognitive Behavioral Therapy as described in the following sections.

James Pennebaker: The Paradigm of Expressive Writing

James Pennebaker was the first researcher that studied therapeutic effects of writing. He developed a method called expressive writing, which consists of putting feelings and thoughts into written words in order to cope with traumatic events or situations that yield distress (Pennebaker & Chung, 2007 ). In the first writing project, Pennebaker and Beall ( 1986 ) asked fifty college students to write for fifteen minutes per day for four consecutive days. They were randomly instructed to write about traumatic topics or non-emotional topics. Results showed that writing about traumatic events was associated with fewer visits to the health center and improvements in physical and mental health. The experiment was repeated several times with different samples: with people who suffered from physical illnesses, such as arthritis and asthma, and from mental pathologies such as depression (Gortner et al., 2006 ). Individuals with different educational levels or writing skills were examined, but these variables were not found to be significant. At first, studies investigated only traumatic events, but later research expanded the focus to general emotional events or specific experiences (Pennebaker & Evans, 2014 ).

According to Pennebaker, what makes writing therapeutic is that the writer openly acknowledges and accepts their emotions, they become able to give voice to his/her blocked feelings and to construct a meaningful story.

Other therapeutic ingredients of expressive writing concern (1) the ability to make causal links among life events and (2) the increased introspective capacity. The former may be favored through the use of causality terms such as “because”, “cause”, “effect”; the latter through the use of insight words (“consider”, “know” etc.). These emotional and cognitive processes were analyzed through a computerized program (Pennebaker et al., 2015 ) and outcomes showed that the more patients used causation words, the more benefits they derived from the activity. Similarly, using certain causal terms expresses the level of cognitive elaboration of the event achieved by the patient and may indicate that the emotional experience has been analyzed and integrated (Pennebaker et al., 2003 ). Thus, the benefits of writing stem from the activity of making sense of an emotional event, the acquisition of insight about the event, the organization and integration of the upheaval in one’s life path.

Moreover, expressive writing allows a change in the way patients narrate life events. Many studies have highlighted that writing in first or third person alters the emotional tone of the narration (Seih et al., 2011 ). It is common for people who have experienced a severe traumatic event to initially narrate it in the third person and only later, once the elaboration and integration processes have set into motion, are they able to narrate their experience in the first person. This phenomenon occurs because third person narration allows the writer to feel safer and more detached from the experience, while first person perspective reminds them that they were the protagonist of the trauma. While writing using the third person can be easier in the wake of a traumatic event, writing in first person has been demonstrated to be more effective in the elaboration process (Slatcher & Pennebaker, 2006 ).

Another issue examined by Pennebaker and Evans ( 2014 ) concerns the difference between writing and talking about a trauma. In expressive writing, an important element consists of feeling completely honest and free to write anything, in a safe and private context without necessarily share the content with a listener or the therapist. Conversely, talking about trauma implies the presence of a listener, and the crucial aspect lies in the listener’s capability to comprehend and accept the patient’s narrative. Moreover, the interactions with a therapist could be particularly stressful for individuals with high levels of social inhibitions and trait anxiety (Allen et al., 2020 ).

Writing Techniques for Addressing Trauma

Writing is considered a therapeutic strategy to cope with life adversities thanks to the positive effects of putting feelings and thoughts into words. There are various writing techniques used as therapeutic strategies to cope with a trauma which are described in Table Table1 1 .

Writing approaches in clinical interventions

What the aforementioned writing therapies all have in common is a theoretical underpinning: the act of writing as a means to modify one’s life story and reframe elements which survivors want to change. Creating stories and thinking of ways to alter them may emphasize on one hand the possibility of a real change to occur, and on the other, the active role of the individual in their own life (Sandstrom & Cramer, 2003 ). In this way, writing can be also defined as a process of resilience: putting negative feelings into words can spark the search for solutions, with the consequence of having a positive attitude towards life challenges and promoting personal growth.

Besides the numerous positive effects of writing, there can be situations in which writing does not work, or when it can actually cause negative side effects. An example of said situation is when an individual has to deal with issues that arise intense painful emotions. In this case, writing can cause crying, very low mood, or even a breakdown (Pennebaker & Chung, 2007 ). This may occur because analyzing a traumatic experience may trigger a process of cognitive rumination, which is considered a specific symptom of PTSD (Pennebaker & Evans, 2014 ).

In conclusion, the paradigm of expressive writing is frequently used in patients who have had distressing experiences. Writing about traumatic experiences can help to elaborate negative emotions connected to the upheaval, to construct a narrative of the event, and to give it a meaning. However when client’s levels of distress are very intense and/or they are maintained by cognitive rumination, it is not advisable to undergo a writing exercise.

McAdams: The Use of Autobiography in the Construction of Self-identity

Writing therapy has also been shown to have benefits in constructing self-identity (Cooper, 2014 ). An important pioneer of this method, Dan McAdams, developed a life story model of identity, which postulates that individuals create and tell evolving life narratives as a means to provide their lives with purpose and integrity (McAdams, 2008 ). Identity is an internalized story that is composed by many narrative elements such as setting, plot, character(s) and theme(s). In fact, human lives develop in time and space, they include a protagonist and many other characters, and they are shaped by various themes. Narrative identities allow one to reenact the past, become aware of the present and have a future perspective. Individuals construct stories to make sense of their existence, and these stories function to conciliate who they are, were and might be according to their self-conception and social identity. Biography, for example, is a written history of a person’s life; it deals with the reconstruction of a personal story in which salient events are selected and told. The therapeutic power of biographies entails the act of selection of worthy events that characterize a person’s life (Lichter et al., 1993 ).

In the same way, the autobiography can be an instrument to create a written life story. The first therapeutic effect is the possibility to define a sense of identity through autobiographical narratives by the identification of significant personal changes and by giving meaning to them. According to Bruner ( 2004 ) writing an autobiography allows the clients to recognize themselves as the authors of their experiences (sense of personal agency).

Another therapeutic ingredient of autobiography is the process of conferring stability to autobiographical memories: people often misremember details of events over time or are influenced by distortion mechanisms (McAdams, 2008 ). Autobiography is useful not only to code every event of self-story, but also it is beneficial for integrating different experiences and for analyzing the life trail, highlighting both continuity and changes. McAdams studied the use of autobiography in life changes, by employing a written procedure, the “Guided Autobiography” (McAdams et al., 2006 ). This is a therapeutic technique aimed at investigating the relationship between the continuity of story themes and personality changes. In the span of ten two-hour sessions, which take place once a week, participants are asked to think and describe the most important events of their life, referring to a specific life theme (i.e. family, money, work, health, spirituality, death, aspirations). Reker et al. ( 2014 ) underlined that Guided Autobiography is an effective method to enable participants to understand and appreciate their life stories, which also increases optimism and self-esteem. In conclusion, Mc Adams technique of guided autobiography entails different therapeutic ingredients: it allows to connect life events and personal memories, and to underscore the process of continuity among them. At the same time, significant life changes are emphasized, and the individual can improve the sense of agency in understanding his/her role as a protagonist of his/her life. Thus, guided autobiography could enhance personal well-being and meaning in life.

The Use of the Diary in CBT

Considering that Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) works on thinking patterns, maladaptive thoughts and dysfunctional behaviors (Butler et al., 2006 ), the diary is a very useful instrument of self-observation. It entails a written exercise in which the client is asked to take note of when and where a stressful situation occurs, the automatic thoughts it elicits, the connected emotions and the consequent behavior. This technique was developed by Aaron Beck at the early stages of cognitive therapy for anxiety and depression (Beck, 1979 ). In writing this diary the writers learn to pay attention to their functioning and acquires self-awareness about their problematic issues (King & Boswell, 2019 ). According to traditional CBT method, the therapeutic ingredients of writing the structured diary consist of helping clients to increase their awareness of automatic thoughts and beliefs, which are influencing their emotions and behaviors. The diary then allows the processes of cognitive restructuring, where negative, automatic thoughts are analyzed and modified in order to achieve a more realistic attitude toward life events and problematic situations (Beck, 1979 ). Thus, writing techniques within CBT consist of keeping a structured diary, which is supervised by the therapists along the various phases of the therapeutic process. The diary in CBT is specifically aimed at addressing symptoms and distress, but it can also trigger cognitive changes, maturation and improved self-awareness at the end of the clinical work (Butler et al., 2006 ).

Existential Approaches: The Bridge Between Clinical Psychology and Positive Psychology

Logotherapy.

Logotherapy is a specific strategy within phenomenological-existential therapies. It relies on a therapeutic paradigm created by Viktor Frankl (Frankl, 1969 ) and based on existential issues. Logotherapy is an entirely word-based treatment. Its tenets assume that life always has meaning, even in the most adverse circumstances and that people always strive to find a personal meaning in their existence (assumption of will to meaning). From this perspective, a journal can be considered a place where people find a meaning in life-threatening events and transform implicit and negative experiences into expressive and positive ones. In fact, Logotherapy emphasizes the importance of words in creating a meaning and, in this case, writing techniques are particularly appropriated to this task. The client is asked to narrate adverse life events using words and sentences that help him/her to acquire a sense of meaning and acceptance.

In phenomenological-existentialist psychotherapies, writing assignments are used to increase clients’ awareness of their limitations and to create an opportunity to reflect on both life and death (Yalom, 1980 ). Specifically, in the exercise of Writing your Epitaph, the client is encouraged to think and write what people would say in their memory. This task aims at clarifying personal values and at committing to them. This allows the identification of the direction individuals want to give to theirs life and to verify if they really are acting towards those goals. The main difference between logotherapy and guided autobiography relies on the philosophical framework used in existential approach, which is not present in Mc Adams paradigm. Furthermore, in logotherapy the narrative topic might be narrowed to a specific traumatic event, not necessarily involving all personal biography. The therapeutic ingredients of logotherapy, thus, concern the increase in life meaning and the possibility of reframing and processing existential issues as death, evil and trauma in individual’s life experiences.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) focuses on the acceptance of unchangeable things and on the integration of different interventions (including strategies of mindfulness) with the aim of increasing psychological flexibility and promoting an active attitude towards problematic matters (Hayes, 2004 ). ACT is based on a rigorous cognitive analysis, the Relational Frame Theory (Reese, 2013 ). This theoretical frame posits that language and cognition allow humans to have the ability to learn to relate events under arbitrary contextual control. This framework particularly analyzes paradoxes, metaphors, stories, exercises, behavioral tasks, and experiential processes (Hayes, 2004 ). This approach has studied a particular mechanism called “Thought Defusion” (Hayes, 2004 ) which deals with the ability to distance one’s self from problematic thoughts. Frequently, individuals cannot see problems because they are “fused” with them. The defusion techniques allow the individual to distance themselves from problems and see them from a more detached perspective (i.e., the helicopter perspective exercise). In this way, patients have the possibility to identify a problematic issue, accept it and find a manner to live with it, which can decrease the level of suffering (Hayes, 2004 ). Thus, the act of writing can be considered as a way to keep distance from one’s own thoughts and feelings in order to be able to modify the behaviors and life choices according to one’s values and priorities.

The first part of this article identifies how the traditional use of writing techniques has been analyzed within different forms of psychotherapy. The subsequent part of this review will describe the application of similar writing techniques within the framework of positive psychology. In particular, the use of expressive writing, journaling or other structured writing techniques will be described as ways to promote personal well-being, personal growth, gratitude and positive emotions in general.

Positive Psychotherapy

Unlike the traditional deficit-oriented approach to psychotherapy, Positive Psychotherapy aims at considering with a similar standing, symptoms and strengths (Rashid & Seligman, 2018 ).

Positive Psychotherapy uses writing techniques in various moments of the therapeutic process (see Table 2 ). For instance, at the beginning of the therapy clients are invited to write a personal presentation in positive terms. This exercise is called “ Positive Introduction” (Rashid, 2015 ). The importance of this exercise lies in the fact that while writing a self-presentation clients highlight their positive characteristics and qualities and they may also recall and describe a particular episode when these strengths were manifested. This initial writing assignment, thus, may foster patients’ self-esteem and self-awareness of positive personal characteristics. In the middle phase of the positive psychotherapy, therapists can suggest the “ Positive Appraisal” activity to their clients. This consists of thinking and writing down resentments, bad memories and negative events which have occurred in their past and that still affect their life. Clients are asked to reframe these past negative events and to search for possible positive consequences in terms of meaning or personal development. The final phase of therapy focuses on exploring and training the individual’s strengths. The exercises proposed in this phase include writing assignments such as “ Gift of Time” and “ Positive legacy”, where the therapist asks clients to write how they would be remembered by significant others and future generations. “ Positive Legacy” is focused on the positive connotations of writing and often it is associated with planning a “gift of time activity” that puts these positive characteristics into practice (Rashid, 2015 ). This technique entails similarities with logotherapy and ACT epitaph exercise, but in PPT the client is guided to emphasize positive aspects of their life and personal qualities, and there is no mention to relational frame theory as in ACT.

Writing approaches in positive intervention

Furthermore, Positive Psychotherapy entails also specific writing techniques devoted to the promotion of specific positive emotions, such as gratitude, forgiveness and wisdom, as described below.

Gratitude is a feeling of appreciation for people or events, which is triggered by the perception of having obtained something beneficial from someone or something (it can be also an impersonal source, such as God or Nature) (Rashid & Seligman, 2018 ). Written exercises of gratitude can be divided into Gratitude Letter, Gratitude Journaling and “ Good versus Bad Memories” .

Gratitude Letter consists of writing and delivering a gratitude letter to a person that the client has never sincerely thanked. This intervention aims at strengthening the client’s relationships and enhancing their social well-being (Lambert et al., 2010 ). In Gratitude Journaling, clients are asked to write three good things which have happened to them during the day (Rashid, 2015 ).

Many studies showed that thinking about memories of gratitude in a written form promotes well-being and increases positive mood because writing allows one to give shape to positive experiences (Toepfer et al., 2012 ; Wong et al., 2018 ). In fact, in gratitude writings individuals are more likely to express positive feelings and have high level of insight, making gratitude letters or journaling a powerful tool to produce not only well-being, but also health improvements (Jans-Beken et al., 2020 ).

Difficulties in writing a gratitude letter relate to the interpersonal nature of this task, because being grateful towards someone entails being dependent on that person and, in turn, this can invoke a sense of vulnerability that makes the writer feel not at ease (Kaczmarek et al., 2015 ). In this way, the psychological costs of writing a gratitude letter are greater than expressing it in a private journal. Another important element of difference pertains the delivery of the letter as the gratitude journal has a personal use, while the letter is written to be delivered to someone. The main risk of writing a letter to someone refers to the possibility of not being accepted or feeling judged by the reader. For this reason, recently, positive therapists may ask their clients to write the letter, without necessarily have it delivered to the recipient. Thus, the benefits associated with a gratitude letter exercise are not necessarily connected with the act of delivery, but are placed in the writing itself (Rash et al., 2011 ).

In addition to gratitude letter and journal, Good versus Bad Memories is a writing activity which has the therapeutic effect of helping clients to understand how anger, bitterness and other depressive symptoms may influence clients’ life and how they can stop these processes by focusing on positive memories and experiences (Rashid & Seligman, 2018 ).

These three writing activities on gratitude are useful in order to emphasize good things that usually are taken for granted. Furthermore, they may downregulate the impact of negative emotions or negative experience in life. (Lyubomirsky & Layous, 2013 ).

Forgiveness

Forgiveness implies a situation of offense where a person makes the choice of letting go of anger and of searching for a compassionate attitude towards the transgressor (Thoresen et al., 2008 ).

Evidence shows that writing about an interpersonal conflict can decrease the level of negative effects in relational conflicts (Gordon et al., 2004 ). The act of writing a forgiveness letter includes a cognitive processing that promotes emotional regulation, the expression of affect and gaining insight. Positive Psychotherapy uses forgiveness exercises in order to transform feelings of anger and bitterness into neutral or positive emotions (Rashid, 2015 ). For example, clients are asked to write a letter where they describe an experience of offence with related feelings and then the promise to forgive the guilty person. McCullough et al. ( 2006 ) found that victims of interpersonal transgressions could became more forgiving toward their transgressors when they were asked to write about possible beneficial effect of the transgression, compared with victims who wrote about traumatic or neutral topics. Thus, the positive narrative approach may facilitate forgiveness and help victims to overcome traumatic interpersonal issues.

As for gratitude letters, the delivery of forgiveness letters is a crucial issue, because the act of showing forgiveness can influence the process of forgiveness itself. In some cases, as highlighted in Gordon and collaborators’ study ( 2004 ) about marital conflicts, writing and delivering a letter is helpful to reduce relational tension and the consequent conflicts, but in other situations where forgiveness remains an intra-personal process, sharing it can be more harmful than beneficial. This may occur particularly when the relationship between victims and transgressors is particularly problematic (or even abusive) and reconciliation is not possible, or not recommendable (Gordon et al., 2004 ).

Forgiveness writing is also helpful in the promotion of self-forgiveness. Jacinto and Edwards ( 2011 ) describe a case where the exercise of writing a letter was used in the therapeutic process of self-forgiveness. The act of writing helped the client to trigger self-empathy and consequentially to let go of negative beliefs about herself.

In conclusions, the therapeutic ingredients of these writing assignments (gratitude and forgiveness letters) concern both an intra-personal dimension (the promotion of self-esteem, self-awareness and a sense of meaning in life) and an interpersonal dimension (the promotion of empathy, compassion, and a sense of connectedness with others). They both constitute the pillars of well-being and positive psychological functioning (Lyubomirsky & Layous, 2013 ).

Wisdom is a complex ability composed of cognitive and emotional competences, such as perspective-taking, thinking with a long-term perspective, empathy, perception and acceptance of emotions (Staudinger, 2008 ). Collecting narratives of wisdom may be connected with autobiographical memory (McAdams, 2008 ). Glück and collaborators ( 2005 ) conducted a study where participants had to write a 15 line paragraph describing all the situations where they did, thought or said something wise; then they had to select a situation from them where they had been wise. This writing task was followed by an interview in which the “wise situations” were discussed. Writing about autobiographical memory kindles the development of strengths related to wisdom, such as acceptance and forgiveness of others, taking different perspectives, being honest and responsible and making compromises.