Baylor Graduate Writing Center

Helping Grad Students Become Better Writers

Writing Genres: The Dissertation

By Jonathan Kanary, GWC Consultant

When I started working on my dissertation, I thought I knew how to write. After all, I had successfully completed seminar papers. I had prepared and delivered talks for conferences. I had even placed a couple of scholarly articles. Surely I had the hang of this academic writing thing by now, right?

Then I got my director’s feedback on a draft chapter. He was gracious, and he liked a lot of what I was doing. But he also made it clear that my work needed a lot of revision. I started to think, “maybe I don’t know what I’m doing after all.”

The Problem

Almost no one who begins writing a dissertation has ever written a dissertation before. You might have written a master’s thesis, and that helps. But you’re also new to this.

The good news is that if you’ve gotten this far, you’ve done a lot of writing. You have most of the skills you need to complete the task.

The challenge is that it isn’t exactly the same task. If you want to master the dissertation, you have to understand what kind of thing it is: its genre .

In this post, I want to break the dissertation’s genre into three parts: the purpose, the audience, and the format.

The Purpose

What is a dissertation for ? This might seem like an obvious question: you’re making a scholarly argument. If you’re in STEM or the Social Sciences, the basis for your argument is probably a study, or a series of studies. If you’re in the Humanities, the material for your argument will likely include evidence you have gathered from books and articles. Your task is to make this argument and make it well.

True—but incomplete. Your dissertation has a second major purpose: showing that you’ve done your work. In today’s world, a graduate degree is a kind of credential. It’s a stamp of approval that you have the competencies those letters after your name represent. Your dissertation tells your committee that they don’t have to feel bad about giving you that stamp of approval. They can release you into the world with a reasonable hope that you know how to do the sorts of things that people with advanced degrees in your field do. This means that you need to demonstrate the thoroughness of your research. And you have to explain—maybe more fully than you would in other kinds of academic writing—exactly how your argument relates to other scholars’ work.

The Audience

Who is the dissertation for? Again, this initially seems obvious: you write for your committee. But have you thought about what that means? Your director may or may not have a high degree of expertise in the specific area of your project. Other members of your committee have relevant expertise; but they almost certainly don’t all work in your exact area. If you have an “outside reader” from another department, or someone from your own department who does a very different kind of research, they may not know all the technical terminology you’re using. They may lack historical context. When you reference a scholarly work that has defined your area, they may not know why it’s such a big deal.

Ask yourself, “What might someone on my committee need to know for this argument to make sense?” And then figure out how to include that information.

Although the primary audience for a dissertation is your committee, you could end up having a secondary audience: other scholars working in your area. I am citing several dissertations as I write my own. However, if you do a good job providing background for everyone on your committee, it will likely be enough for secondary readers as well.

So how the heck do I put together this dissertation?

Here, I have good news: the Graduate School has lots of resources to help you format your dissertation properly. (Hint: If you go ahead and put your draft into this format to begin with, it will save you a lot of time later.)

But you might also want to ask your director if he or she can point you to an earlier dissertation that proved successful. Sometimes seeing what an acceptable entry in the genre looks like can help you imagine your own.

Getting Done

Notice, I said an “acceptable” entry, not a “brilliant” or “ground-breaking” one. More than one faculty member has told me, “A good dissertation is a done dissertation.” It doesn’t have to be a masterpiece. This isn’t the last thing you get to write. You will have plenty of time to revise before it becomes a book or a series of articles. Just keep your purpose in mind, pursue it in a way that will make sense to your audience, and follow the basic format.

You can do this.

Jonathan Kanary is a PhD candidate in English at Baylor, where he serves as a consultant for the Graduate Writing Center and teaches for the Great Texts department. His research focuses on the intersection of literature and spirituality, with a particular interest in the Middle Ages and 19th-20th century British literatures.

One thought on “ Writing Genres: The Dissertation ”

Best of luck for the scientists for making this living planet environmentally friendly.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.3: Literary Thesis Statements

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 101132

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The Literary Thesis Statement

Literary essays are argumentative or persuasive essays. Their purpose is primarily analysis, but analysis for the purposes of showing readers your interpretation of a literary text. So the thesis statement is a one to two sentence summary of your essay's main argument, or interpretation.

Just like in other argumentative essays, the thesis statement should be a kind of opinion based on observable fact about the literary work.

Thesis Statements Should Be

- This thesis takes a position. There are clearly those who could argue against this idea.

- Look at the text in bold. See the strong emphasis on how form (literary devices like symbolism and character) acts as a foundation for the interpretation (perceived danger of female sexuality).

- Through this specific yet concise sentence, readers can anticipate the text to be examined ( Huckleberry Finn) , the author (Mark Twain), the literary device that will be focused upon (river and shore scenes) and what these scenes will show (true expression of American ideals can be found in nature).

Thesis Statements Should NOT Be

- While we know what text and author will be the focus of the essay, we know nothing about what aspect of the essay the author will be focusing upon, nor is there an argument here.

- This may be well and true, but this thesis does not appear to be about a work of literature. This could be turned into a thesis statement if the writer is able to show how this is the theme of a literary work (like "Girl" by Jamaica Kincaid) and root that interpretation in observable data from the story in the form of literary devices.

- Yes, this is true. But it is not debatable. You would be hard-pressed to find someone who could argue with this statement. Yawn, boring.

- This may very well be true. But the purpose of a literary critic is not to judge the quality of a literary work, but to make analyses and interpretations of the work based on observable structural aspects of that work.

- Again, this might be true, and might make an interesting essay topic, but unless it is rooted in textual analysis, it is not within the scope of a literary analysis essay. Be careful not to conflate author and speaker! Author, speaker, and narrator are all different entities! See: intentional fallacy.

Thesis Statement Formula

One way I find helpful to explain literary thesis statements is through a "formula":

Thesis statement = Observation + Analysis + Significance

- Observation: usually regarding the form or structure of the literature. This can be a pattern, like recurring literary devices. For example, "I noticed the poems of Rumi, Hafiz, and Kabir all use symbols such as the lover's longing and Tavern of Ruin "

- Analysis: You could also call this an opinion. This explains what you think your observations show or mean. "I think these recurring symbols all represent the human soul's desire." This is where your debatable argument appears.

- Significance: this explains what the significance or relevance of the interpretation might be. Human soul's desire to do what? Why should readers care that they represent the human soul's desire? "I think these recurring symbols all show the human soul's desire to connect with God. " This is where your argument gets more specific.

Thesis statement: The works of ecstatic love poets Rumi, Hafiz, and Kabir use symbols such as a lover’s longing and the Tavern of Ruin to illustrate the human soul’s desire to connect with God .

Thesis Examples

SAMPLE THESIS STATEMENTS

These sample thesis statements are provided as guides, not as required forms or prescriptions.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Literary Device Thesis Statement

The thesis may focus on an analysis of one of the elements of fiction, drama, poetry or nonfiction as expressed in the work: character, plot, structure, idea, theme, symbol, style, imagery, tone, etc.

In “A Worn Path,” Eudora Welty creates a fictional character in Phoenix Jackson whose determination, faith, and cunning illustrate the indomitable human spirit.

Note that the work, author, and character to be analyzed are identified in this thesis statement. The thesis relies on a strong verb (creates). It also identifies the element of fiction that the writer will explore (character) and the characteristics the writer will analyze and discuss (determination, faith, cunning).

The character of the Nurse in Romeo and Juliet serves as a foil to young Juliet, delights us with her warmth and earthy wit, and helps realize the tragic catastrophe.

The Genre / Theory Thesis Statement

The thesis may focus on illustrating how a work reflects the particular genre’s forms, the characteristics of a philosophy of literature, or the ideas of a particular school of thought.

“The Third and Final Continent” exhibits characteristics recurrent in writings by immigrants: tradition, adaptation, and identity.

Note how the thesis statement classifies the form of the work (writings by immigrants) and identifies the characteristics of that form of writing (tradition, adaptation, and identity) that the essay will discuss.

Samuel Beckett’s Endgame reflects characteristics of Theatre of the Absurd in its minimalist stage setting, its seemingly meaningless dialogue, and its apocalyptic or nihilist vision.

A close look at many details in “The Story of an Hour” reveals how language, institutions, and expected demeanor suppress the natural desires and aspirations of women.

Generative Questions

One way to come up with a riveting thesis statement is to start with a generative question. The question should be open-ended and, hopefully, prompt some kind of debate.

- What is the effect of [choose a literary device that features prominently in the chosen text] in this work of literature?

- How does this work of literature conform or resist its genre, and to what effect?

- How does this work of literature portray the environment, and to what effect?

- How does this work of literature portray race, and to what effect?

- How does this work of literature portray gender, and to what effect?

- What historical context is this work of literature engaging with, and how might it function as a commentary on this context?

These are just a few common of the common kinds of questions literary scholars engage with. As you write, you will want to refine your question to be even more specific. Eventually, you can turn your generative question into a statement. This then becomes your thesis statement. For example,

- How do environment and race intersect in the character of Frankenstein's monster, and what can we deduce from this intersection?

Expert Examples

While nobody expects you to write professional-quality thesis statements in an undergraduate literature class, it can be helpful to examine some examples. As you view these examples, consider the structure of the thesis statement. You might also think about what questions the scholar wondered that led to this statement!

- "Heart of Darkness projects the image of Africa as 'the other world,' the antithesis of Europe and therefore civilization, a place where man's vaunted intelligence and refinement are finally mocked by triumphant bestiality" (Achebe 3).

- "...I argue that the approach to time and causality in Boethius' sixth-century Consolation of Philosophy can support abolitionist objectives to dismantle modern American policing and carceral systems" (Chaganti 144).

- "I seek to expand our sense of the musico-poetic compositional practices available to Shakespeare and his contemporaries, focusing on the metapoetric dimensions of Much Ado About Nothing. In so doing, I work against the tendency to isolate writing as an independent or autonomous feature the work of early modern poets and dramatists who integrated bibliographic texts with other, complementary media" (Trudell 371).

Works Cited

Achebe, Chinua. "An Image of Africa" Research in African Literatures 9.1 , Indiana UP, 1978. 1-15.

Chaganti, Seeta. "Boethian Abolition" PMLA 137.1 Modern Language Association, January 2022. 144-154.

"Thesis Statements in Literary Analysis Papers" Author unknown. https://resources.finalsite.net/imag...handout__1.pdf

Trudell, Scott A. "Shakespeare's Notation: Writing Sound in Much Ado about Nothing " PMLA 135.2, Modern Language Association, March 2020. 370-377.

Contributors and Attributions

Thesis Examples. Authored by: University of Arlington Texas. License: CC BY-NC

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Chapter 3: The Writing Process, Composing, and Revising

3.4 Creating the Thesis

Yvonne Bruce and Emilie Zickel

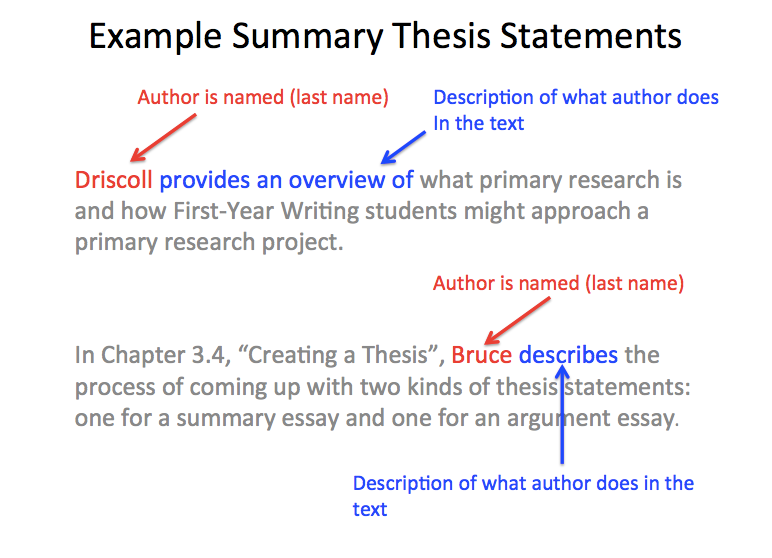

Now that you have begun or are well into the process of reading and drafting, you will have to create a thesis for any paper you are assigned. A thesis is simply an expression of the main idea of what you are writing about.

The thesis will be determined by the kind or genre of paper you are asked to write, but even a summary assignment—a paper in which you summarize the ideas of another writer without adding your own thoughts—must have a thesis. A thesis for a summary would be your expression of the main idea of the work you are summarizing. The presence of a thesis, and paragraphs to support that thesis, is what distinguishes a summary from a list.

Imagine, for example, that you are summarizing last night’s football game to a friend. You would not summarize it this way, unless you wanted to put your friend to sleep: “First the Falcons came out on the field, and then the Steelers came out on the field, and then there was a coin toss, and then the Falcons kicked off, and then the Steelers returned the ball for thirty yards, and then . . .”

What you would do instead is organize your summary around what you thought was the most important element of that game: “Last night’s game was all defense! The Steelers returned the ball for thirty yards on the first play, but after that, they hardly even got any first downs. The Falcons blocked them on almost every play, and they managed to win the game even though they only scored one touchdown themselves.”

For most papers, however, you will take a more active role in the content of the composition, creating a thesis that expresses your main idea about a topic, often in response to what others think about that topic.

In some cases you will be allowed to create a thesis about a topic of your choice; in most cases, you will required to create a thesis about a topic related to the subject or theme of the class.

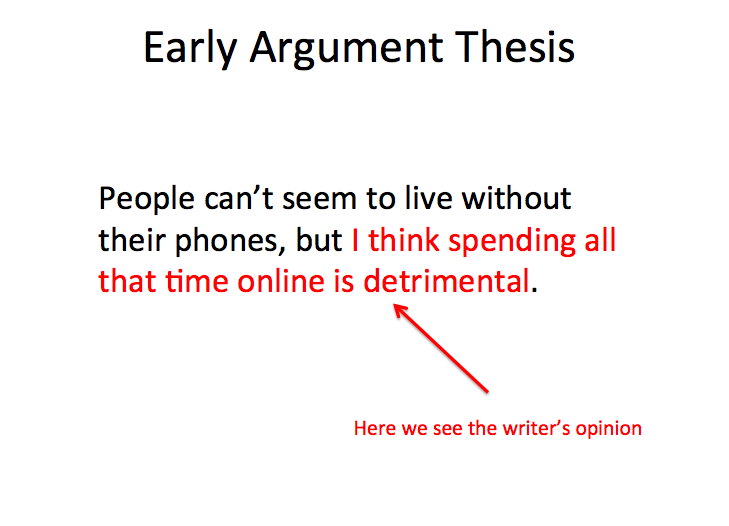

Let’s say you have to create a thesis on a topic like The American Dream or Technology and Society or The Rhetoric of Climate Change. Maybe you’ve already read some essays or material on these subjects, and maybe you haven’t, but you want to start drafting your thesis with a claim about your subject. Bring to your claim what you know and what you think about it:

You’re already off to a good start: this thesis makes a claim, it demonstrates some knowledge or authority, and it includes two sides to the issue. How can you make it better? Remember, you have to be able to write a paper in support of your thesis, so the more detailed, concrete, and developed your thesis is, the better. Here are a couple suggestions for improving any thesis:

- Define your terms

- Develop the parts of your thesis so it answers as many who, what, when, where, how, and why questions as possible

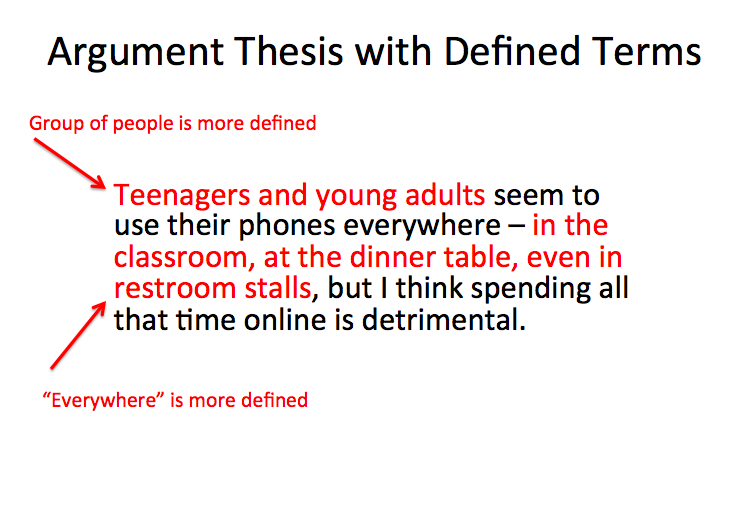

Defining your terms

In your draft or working thesis above, are there any terms that would benefit from more definition? What do you mean by people , for example? Can that word be replaced with young people , or teenagers and young adults ? If you replaced people with these more specific terms, couldn’t you also then write your paper with more authority, as you are one of the people you’re writing about?

You might also define “can’t seem to live without,” which sounds good initially but is too general without explanation, with something more exact that appeals to your reader and can be supported with evidence or explained at greater length in your paragraphs: people “use their phones in the classrooms, at the dinner table, and even in restroom stalls.”

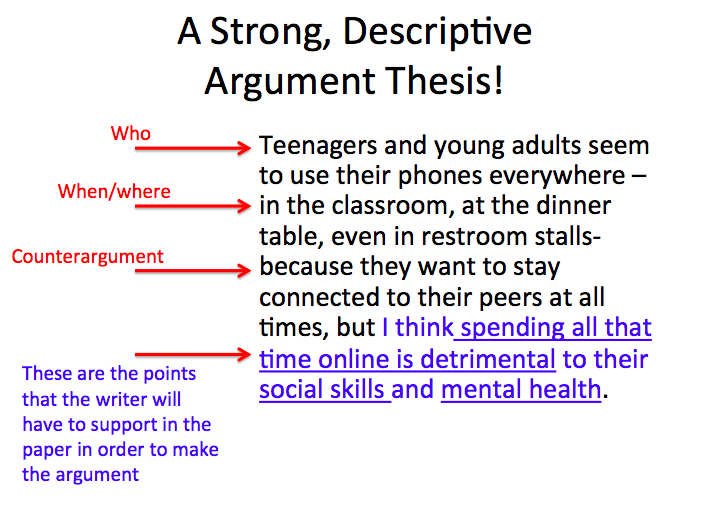

Making sure your thesis answers questions

Your thesis is a snapshot or summary of your paper as a whole. Thus, you want your thesis to be something you can unfold or unpack or develop into a much longer work. And if your thesis makes a claim, that means it also answers a question. Thus, you want your thesis to answer or discuss the question as deeply and fully as possible. You can do this grammatically by adding prepositional phrases and “because” clauses that bring out the specifics of your thinking and tell your reader who, what, when, where, how, and/or why:

“Teenagers and young adults seem to use their phones everywhere—in the classroom, at the dinner table, even in restroom stalls— because they want to stay connected to their friends and peers at all times , but I think spending that much time online is detrimental to their social skills and mental health .”

Notice that this thesis, while not substantially different from the draft or working thesis you began with, has been substantially revised to be more specific, supported, and authoritative. It lays out an organized argument for a convincing paper. Because it is so complete and specific, in fact, it can be easily changed if you find research that contradicts your claim or if you change your mind about the topic as you write and reflect:

“Teenagers and young adults seem to use their phones everywhere—in the classroom, at the dinner table, even in restroom stalls—because they want to stay connected to their friends and peers at all times, and research suggests that this connection has primarily positive psychological and emotional benefits .”

3.4 Creating the Thesis by Yvonne Bruce and Emilie Zickel is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Feedback/Errata

Comments are closed.

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write a Thesis

I. What is a Thesis?

The thesis (pronounced thee -seez), also known as a thesis statement, is the sentence that introduces the main argument or point of view of a composition (formal essay, nonfiction piece, or narrative). It is the main claim that the author is making about that topic and serves to summarize and introduce that writing that will be discussed throughout the entire piece. For this reason, the thesis is typically found within the first introduction paragraph.

II. Examples of Theses

Here are a few examples of theses which may be found in the introductions of a variety of essays :

In “The Mending Wall,” Robert Frost uses imagery, metaphor, and dialogue to argue against the use of fences between neighbors.

In this example, the thesis introduces the main subject (Frost’s poem “The Mending Wall”), aspects of the subject which will be examined (imagery, metaphor, and dialogue) and the writer’s argument (fences should not be used).

While Facebook connects some, overall, the social networking site is negative in that it isolates users, causes jealousy, and becomes an addiction.

This thesis introduces an argumentative essay which argues against the use of Facebook due to three of its negative effects.

During the college application process, I discovered my willingness to work hard to achieve my dreams and just what those dreams were.

In this more personal example, the thesis statement introduces a narrative essay which will focus on personal development in realizing one’s goals and how to achieve them.

III. The Importance of Using a Thesis

Theses are absolutely necessary components in essays because they introduce what an essay will be about. Without a thesis, the essay lacks clear organization and direction. Theses allow writers to organize their ideas by clearly stating them, and they allow readers to be aware from the beginning of a composition’s subject, argument, and course. Thesis statements must precisely express an argument within the introductory paragraph of the piece in order to guide the reader from the very beginning.

IV. Examples of Theses in Literature

For examples of theses in literature, consider these thesis statements from essays about topics in literature:

In William Shakespeare’s “ Sonnet 46,” both physicality and emotion together form powerful romantic love.

This thesis statement clearly states the work and its author as well as the main argument: physicality and emotion create romantic love.

In The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne symbolically shows Hester Prynne’s developing identity through the use of the letter A: she moves from adulteress to able community member to angel.

In this example, the work and author are introduced as well as the main argument and supporting points: Prynne’s identity is shown through the letter A in three ways: adulteress, able community member, and angel.

John Keats’ poem “To Autumn” utilizes rhythm, rhyme, and imagery to examine autumn’s simultaneous birth and decay.

This thesis statement introduces the poem and its author along with an argument about the nature of autumn. This argument will be supported by an examination of rhythm, rhyme, and imagery.

V. Examples of Theses in Pop Culture

Sometimes, pop culture attempts to make arguments similar to those of research papers and essays. Here are a few examples of theses in pop culture:

America’s food industry is making a killing and it’s making us sick, but you have the power to turn the tables.

The documentary Food Inc. examines this thesis with evidence throughout the film including video evidence, interviews with experts, and scientific research.

Orca whales should not be kept in captivity, as it is psychologically traumatizing and has caused them to kill their own trainers.

Blackfish uses footage, interviews, and history to argue for the thesis that orca whales should not be held in captivity.

VI. Related Terms

Just as a thesis is introduced in the beginning of a composition, the hypothesis is considered a starting point as well. Whereas a thesis introduces the main point of an essay, the hypothesis introduces a proposed explanation which is being investigated through scientific or mathematical research. Thesis statements present arguments based on evidence which is presented throughout the paper, whereas hypotheses are being tested by scientists and mathematicians who may disprove or prove them through experimentation. Here is an example of a hypothesis versus a thesis:

Hypothesis:

Students skip school more often as summer vacation approaches.

This hypothesis could be tested by examining attendance records and interviewing students. It may or may not be true.

Students skip school due to sickness, boredom with classes, and the urge to rebel.

This thesis presents an argument which will be examined and supported in the paper with detailed evidence and research.

Introduction

A paper’s introduction is its first paragraph which is used to introduce the paper’s main aim and points used to support that aim throughout the paper. The thesis statement is the most important part of the introduction which states all of this information in one concise statement. Typically, introduction paragraphs require a thesis statement which ties together the entire introduction and introduces the rest of the paper.

VII. Conclusion

Theses are necessary components of well-organized and convincing essays, nonfiction pieces, narratives , and documentaries. They allow writers to organize and support arguments to be developed throughout a composition, and they allow readers to understand from the beginning what the aim of the composition is.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Graduate School-Specific Genres

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource provides on overview of several genres that are common in graduate school settings along with guiding questions and suggestions for writing them.

Literature Reviews

The literature review, whether embedded in an introduction or standing as an independent section, is often one of the most difficult sections to compose in academic writing. A literature review requires the writer to perform extensive research on published work in one’s field in order to explain how one’s own work fits into the larger conversation regarding a particular topic. This task requires the writer to spend time reading, managing, and conveying information; the complexity of literature reviews can make this section one of the most challenging parts of writing about one’s research. This handout will provide some strategies for revising literature reviews.

Organizing Literature Reviews

Because literature reviews convey so much information in a condensed space, it is crucial to organize your review in a way that helps readers make sense of the studies you are reporting on. Two common approaches to literature reviews are chronological —ordering studies from oldest to most recent—and topical —grouping studies by subject or theme. Along with deliberately choosing an overarching structure that fits the writer’s topic, the writer should assist readers by using headings, incorporating brief summaries throughout the review, and using language that explicitly names the scope of particular studies within the field of inquiry, the studies under review, and the domain of the writer’s own research. When revising your own literature review, or a peer’s, it may be helpful to ask yourself some of the following questions:

Questions for Revision

- Is the literature review organized chronologically or by topic? Is the writer clear about which approach is being used in the review?

- Does the writer use headings or paragraph breaks to show distinctions in the groups of studies under consideration?

- Does the writer explain why certain groups of studies (or individual studies) are being reviewed by drawing a clear connection to his or her topic?

- Does the writer make clear which of the studies described are most important?

- Does the writer cover all important areas of research related to his or her topic?

- Does the writer use transitions and summaries to move from one study or set of studies to the next?

- By the end of the literature review, is it clear why the current research is necessary?

Showing the gaps

The primary purpose of the literature review is to demonstrate why the author’s study is necessary. Depending on the writer’s field, it may or may not be clear that research on a particular topic is necessary for advancing knowledge. As the writer composes the literature review, he or she must construct an argument of sorts to establish the necessity of his or her research. Therefore, one of the key tasks for writers is to establish where gaps in current research lie. The writer must show what has been overlooked, understudied, or misjudged by previous studies in order to create space for the new research within an area of academic or scientific inquiry.

- Does the review mention flaws, gaps, or shortcomings of specific studies or groups of studies?

- Does the author point out areas that have not yet been researched or have not yet been researched sufficiently?

- Does the review demonstrate a change over time or recent developments that make the author’s research relevant now?

- Does the author discuss research methods used to study this topic and/or related topics?

- Does the author clearly state why his or her research is necessary?

WORKS CONSULTED

Galvan, Jose L. Writing Literature Reviews: A Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Los Angeles: Pyrczak Publishing, 1999. Print.

Seminar Papers

Common in the humanities and social sciences, graduate students are often asked to write seminar papers at the end of the semester as a final project for their courses. They often strike a balance between displaying mastery of the course material and exploring some topic within the scope of the course in more depth. Some professors will provide specific requirements about length, topics, components, audience, and purpose; others may give students almost total freedom. As with any other assignment, check with your professor to make sure you understand their expectations.

If you have some freedom to determine for yourself what your seminar paper will be, you may want to consider ways to use the paper as an opportunity for developing your own work. Here are some questions to help you think through your seminar paper; which ones work for you may vary depending on your professor's expectations.

- Seminar papers are often an appropriate length for conference presentations. Are there conferences coming up that you could apply to with a topic you could cover in this seminar paper, so that you could get feedback on a draft of your conference presentation from your professor? Have you already been accepted to a conference with a proposal that falls into the scope of this course?

- You might be thinking about publications, depending on where you are in your grad school career. Seminar papers can often serve as useful seeds for publications; would your professor be amenable to working with you over a longer term to help expand your seminar paper into an eventual publication?

- If you are working toward a thesis or dissertation whose topic you already know or have an idea of, a seminar paper could be an opportunity to explore that topic further or begin working on the larger research project. Would your professor be open to offering you feedback with that in mind?

- Would your professor be willing to bend the requirements of the assignment slightly to help you make the paper useful to you in one of the above ways? For instance, you might ask your professor if you could write to a different audience (like conference attendees for a specific organization).

Prospectus (Dissertation Proposal)

Some graduate students will need to write and defend a proposal for their dissertation topic before they pursue the full project. This proposal is sometimes (but not always) called a prospectus. In some fields or at some universities, it is this dissertation proposal defense that marks the graduate student's transition from doctoral student to doctoral candidate.

Alternatively, some fields and universities use the comprehensive exams (also called comps, quals or qualifying exams, general exams or generals, prelims or preliminary exams) as the transition from student to candidate. Often in these cases the dissertation committee will be the same as or similar to the examination committee.

Expectations for proposing a dissertation topic and getting that proposal approved by your committee will vary across fields and even across particular universities; individual dissertation chairs may, too, have their own particular expectations. As with any major writing task, you should discuss these expectations with your advisor before you start and as you write.

Most dissertation proposals will need to answer similar questions, however, so there are some commonalities among prospectuses that might be helpful to you as you write.

- Introduction. Your committee will need some context and background for the topic you are working on, particularly if you are dealing with a particular case, example, or topic that is not your committee members' main research area. This section should also summarize your project, its relevance, and its anticipated contributions in a paragraph or two.

- Literature Review. Your committee will not need a literature review of the size and depth you would include in your dissertation, but you should situate your project among the key scholars you base your work on, and you should demonstrate that you have read enough to understand the existing conversations on your topic. One of the main goals of a dissertation proposal is often to show that your topic has not yet been adequately studied, and your lit review may be one place where you show that.

- Proposed Methodology. Your committee will want to know how you propose to study your topic, and what those specific methods will help you learn that others won't (i.e., is your methodology appropriate for the questions you are asking). In some fields this may be more contested than others, where standard methods are more established or concrete.

- Anticipated Contributions. Given that a prospectus is a proposal, rather than a conclusion, most prospectuses end with anticipated contributions. This section often echoes the argument for relevance and value from the introduction, and goes into more detail about why the project is worth pursuing.

- Anticipated Constraints. You may need to include a section describing potential obstacles or constraints for your research. All research has constraints, and this section is usually more about giving your committee a way to help you address potential problems and set you up for success than it is about discouraging you from pursuing a particular topic or method.

14.3 Methods for Studying Genres

The previous section outlined some key terms and definitions for the study of writing. This section builds on that by providing an overview of research tools that can be used to better understand writing-in-context. Some of these tools–like an interview–may seem more familiar to you than others (such as genre analysis). At the same time, an activity you probably engage in every day–observation–achieves importance when done in the context of research and analysis.

There is no one right way to “do” writing research. Choosing the right tools depends on what it is you hope to learn. As you study a genre, whether it is a resume, a report, a procedural, or a complaint letter, think creatively about which of the following methods might help you learn more about it.

Genre/Textual Analysis

If genres are the key object of study for writing researchers, then genre analysis is the key tool for studying those objects–for unlocking their meaning. While it is true that we can learn a great deal about genres by observing people using them and even asking their users about them (which I detail in the next section), there is often important meaning that goes unnoticed by the producers and users of a genre. This meaning is what writing researchers try to access by studying the genres themselves. To put it another way, genres often have embedded in them a kind of code or shorthand that can reveal important information about the context in which they are used. As someone learning to write in that context, such information can help you to advance in your writing skills more quickly.

So how do writing researchers do this analysis? In short, genre analysis involves picking apart and noting the various features of a particular text in order to figure out what they mean (i.e., why they are significant) for the people who use that genre. In that sense, writing researchers act as detectives, revealing clues in order to then piece them all together and generate a cohesive story about what those clues mean.

It probably will not surprise you to know that, once again, curiosity plays an important role in conducting genre analysis. While it can be tempting when looking at a text to think there is not much to say about it (this is especially true when you take something as everyday as your grocery list or the menu at a coffee shop), when we begin to ask questions, the complexity of a text (and the genre it represents) is pretty quickly revealed.

A precursor to genre analysis is what researchers call “document collection.” While it is true that the more samples of a genre you find the more reliable and extensive your analysis can and will be, analyzing even one text can reveal a great deal. So, if genre analysis sounds kind of overwhelming or challenging, start by looking at a single sample text rather than many.

The following questions can get you thinking about (and taking notes on) how you would describe a sample text, by focusing on its content , its form , and its presentation :

- Who and what is referenced in the document?

- What information is included in the document? How much?

- What is the rhetorical purpose of the document?

- How is information organized, from beginning to end? In other words, what appears where?

- What kinds of sentences are used (questions, statements, commands, etc.)?

- What do you notice about the kind of language that is used?

- How would you describe the tone of the writing?

- How does the text use rhetorical appeals (ethos, pathos, logos)?

- Are section headings used in the document?

- Does the document include text only, or text and images? What is the layout like?

- What font size and style is used?

- How would you describe the “look” of the document?

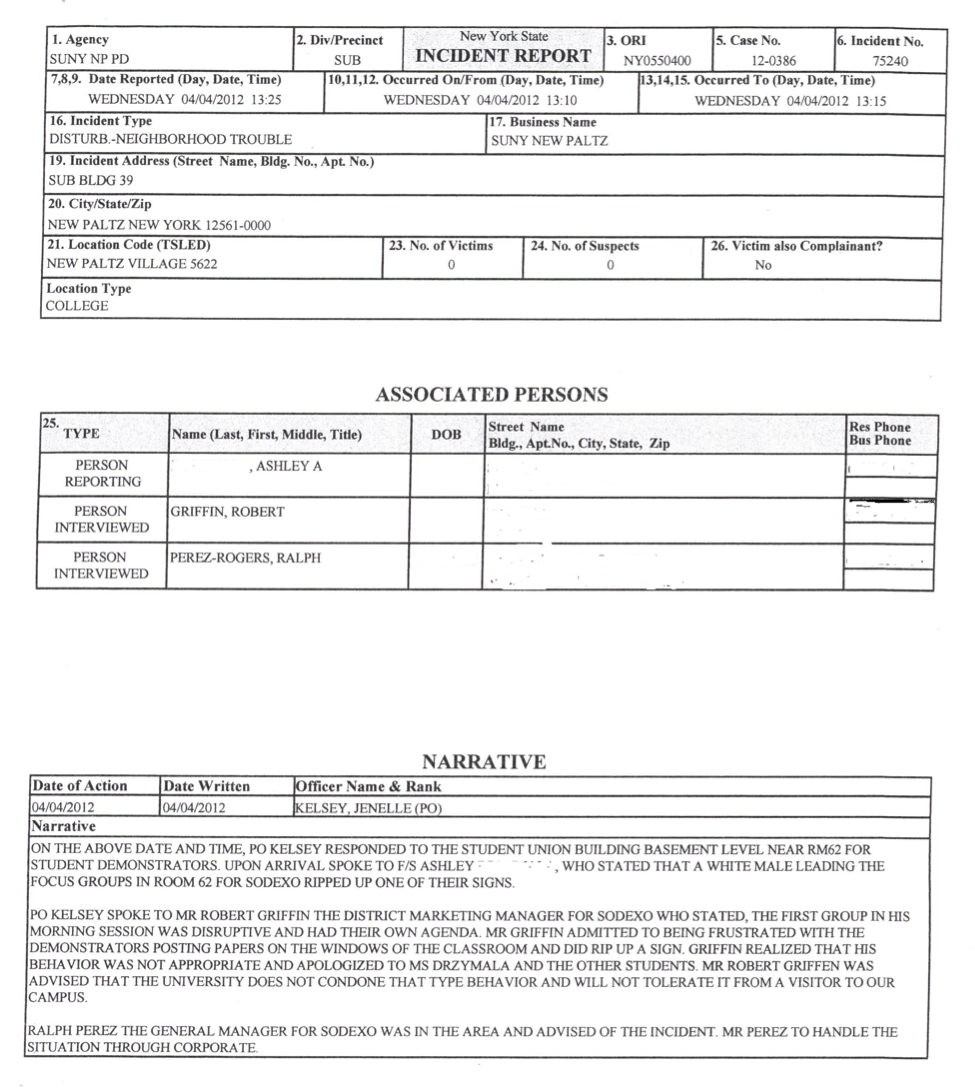

Figure 1 provides a sample police incident report and is followed by some notes you would be likely to make based on the suggested questions above. Alternate formats: Word version of incident report ; PDF version of incident report .

Case Study, Part One: Notes on the Incident Report

- When the incident occurred

- Where the incident occurred

- Who was involved

- How many were involved

- Who was interviewed

- What happened (narrative)

- Which precinct is responsible for investigating

- Type of incident, people involved (victims/suspects), and location

- Filing information (case and incident numbers)

- Three distinct sections

- Logistical info appears first, “associated persons” appears second, narrative of the event appears third

- Narrative uses simple declarative statements, typically with people occupying the place of subject

- Use of verbs is active but primarily neutral, with a focus on communication that transpired (“responded,” “spoke,” “admitted,” “realized,” “advised”), with two instances of the use of passive voice (“was advised”)

- Narrative is described with a neutral tone and feels formal

- Focus of narrative is on actions taken that

- Narrative is described in chronological order, beginning with officer responding to incident, moving through the incident, and providing information on follow-up

- Items used for referential or filing reasons are numbered

- Information is organized into boxes and tables

- Each section is clearly labeled

- Abbreviations are used throughout

- Report is typed

After you have answered these questions, it is time to start looking for patterns and connections that will help you draw conclusions about what these features mean. Doing so involves a kind of creative thinking that is best done by someone who has been involved in studying or practicing the profession under investigation. Generally speaking, it is best to give some consideration to how the features of a particular genre might be connected to goals, objectives, and values of a particular position, organization, and/or context, since it is that context that produced the need for that genre in the first place.

Case Study, Part Two: Analysis of the Incident Report

The content, form, and presentation of the police incident report form work together to present a verifiable , objective account. Used internally, the design of the form helps to create uniformity by directing the officer to include the information that is likely to prove most salient for police purposes and for easy retrieval should future incidents occur. This streamlined approach to documentation keeps the focus on material and factual evidence, which clearly relates to the fact that this is a document that may be used in a legal context.

Generally speaking, a document that pays little attention to design, but has a great deal of detailed content, might derive from a situation where people place heavy emphasis on the development of ideas but don’t necessarily need to act on those ideas; on the other hand, if a document makes heavy use of section headings in order to direct the reader more carefully, it might suggest a need for greater efficiency of time and/or a number of readers with different background knowledge. Of course, there are genres that will do both: include a great number of complex ideas, neatly organized into easily accessible sections. No matter what you find, there is an interpretation to be discovered and explained with evidence from the text itself. The connecting of evidence to interpretation/conclusion is genre analysis.

[ Genre Analysis Essay video without captions ; Genre Analysis Essay video with captions ]

Interviewing is something that happens informally all the time when we query colleagues or supervisors about how to write in a new genre. But a formal interview is a particular kind of research method that takes a bit of practice and can be quite difficult if you have never done it before. With a question we ask of a colleague, we usually have something very specific we want to know, but as a research method, interviews are usually used in order to answer a research question –and it is that distinction that you need to keep in mind.

A good research question, as you may have already learned in other college-level classes, does not have an easy answer. In fact, it usually does not have a single answer either; instead, it is a question that requires interpretation and that might be answered differently depending on who you ask. That said, it is answerable, meaning that given the right collection of evidence, you would be able to craft a response of some kind. In writing research, the interview is one way to collect just such evidence, since talking to someone about how, when, and why they use writing in their profession can provide all kinds of insight that you might miss if you were to analyze a text all by itself. Typically, these kinds of questions (of the “how,” “when,” and “why” variety) help writing researchers to understand the particular importance of writing to a specific profession, industry, organization, or even economy.

It is not uncommon for people in workplace settings not to realize just how much writing is a part of their everyday work practices. In the course of being asked questions, though, they often reveal the way that writing helps them accomplish their jobs successfully and make sure the company or organization runs effectively and achieves its goals. This is true whether you are interviewing a doctor, a firefighter, a restaurant manager, an electrician, a politician, a general contractor, or a computer specialist.

Here are some general advice and reminders for getting organized to conduct an interview:

- Practice good manners when scheduling the interview. This is an opportunity to practice being professional in your communication: everything you know about audience analysis should come into play as you request someone’s time and input.

- Be sure to practice your interview questions ahead of time. Questions that seem straightforward to you might not be clear to someone else; alternatively, they might clearly call for a different kind of answer than what you anticipated. The best way to know is to practice them on someone who is not your intended interviewee. Then, revise accordingly.

- Request permission to record the interview. You will be glad to have a record to return to if your interviewee says yes. Whether or not you record the interview, though, be sure to take notes in the interview (this is something you can and should practice in your practice interview as well). Recording devices can fail; writing during the interview can also help you to focus on what your interviewee is saying and to think of new, sometimes clarifying questions, as the interview proceeds.

Observation

Another powerful research tool is simply observing where the writing of a particular profession takes place. The values of a company or organization, the expectations they hold for their employees and various working conditions are often on display if you only look for them. For example:

- Is the workplace open to the public, or does it require secure entry?

- Do people work in offices or cubicles? Or maybe there is no individual work space at all?

- How many meeting rooms are there? How big are they?

- Are people milling around, or are they mostly on computers?

- How is the workplace decorated?

- What is the dress code?

The answers to these questions can lead to new insight regarding how genres are used and produced and help develop new questions for you to consider. Furthermore, observation also helps with imagining texts in use, which is so crucial to an effective analysis of your audience.

Genre Ecology Maps

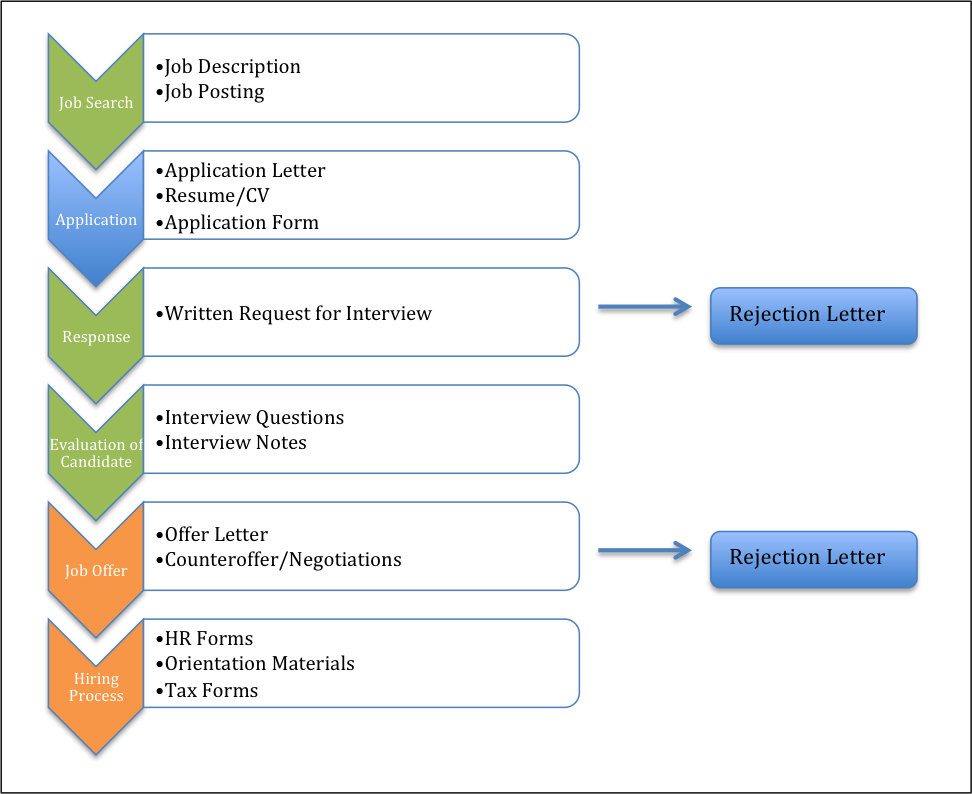

A Genre Ecology Map, or GEM, is a visual representation of genres in action, interacting with one another. Let’s consider an earlier example: the job description. We could explain, using words, that the job description leads to job applications, which (often) lead to interviews and background checks, the hiring of an individual and all the associated paperwork, as well as training materials. But if we wanted to represent that visually, it would look something like Figure 2. Alternate formats: Word version of Job Application GEM ; PDF version of Job Application GEM .

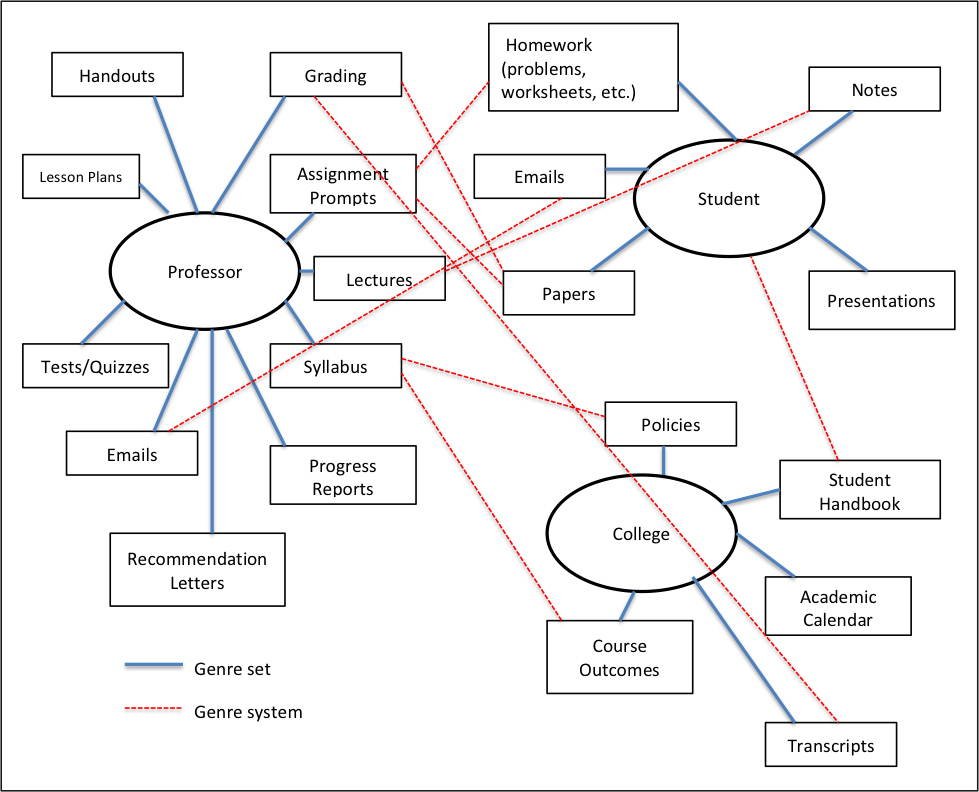

All of a sudden, with a visual illustration, we have a slightly different understanding of the complexity involved in the production and circulation of different kinds of writing. Figure 3 provides another example, one that captures the intersection of different writers, positions, and stakeholders (put another way: the intersection of different genre sets in the college classroom). Alternate formats: Word version of Classroom GEM ; PDF version of Classroom GEM .

Particularly if you are a visual learner, maps like those above can help you to “see” genres in a way you might not otherwise and to reinforce what I have noted in sections above about how writing is not static but actually performs “actions” in various workplace settings.

CHAPTER ATTRIBUTION INFORMATION

This chapter was written by Allison Gross, Portland Community College, and is licensed CC-BY 4.0 .

Technical Writing Copyright © 2017 by Allison Gross, Annemarie Hamlin, Billy Merck, Chris Rubio, Jodi Naas, Megan Savage, and Michele DeSilva is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Definition of Genre

Genre originates from the French word meaning kind or type. As a literary device, genre refers to a form, class, or type of literary work. The primary genres in literature are poetry, drama / play , essay , short story , and novel . The term genre is used quite often to denote literary sub-classifications or specific types of literature such as comedy , tragedy , epic poetry, thriller , science fiction , romance , etc.

It’s important to note that, as a literary device, the genre is closely tied to the expectations of readers. This is especially true for literary sub-classifications. For example, Jane Austen ’s work is classified by most as part of the romance fiction genre, as demonstrated by this quote from her novel Sense and Sensibility :

When I fall in love, it will be forever.

Though Austen’s work is more complex than most formulaic romance novels, readers of Austen’s work have a set of expectations that it will feature a love story of some kind. If a reader found space aliens or graphic violence in a Jane Austen novel, this would undoubtedly violate their expectations of the romantic fiction genre.

Difference Between Style and Genre

Although both seem similar, the style is different from the genre. In simple terms, style means the characters or features of the work of a single person or individual. However, the genre is the classification of those words into broader categories such as modernist, postmodernist or short fiction and novels, and so on. Genres also have sub-genre, but the style does not have sub-styles. Style usually have further features and characteristics.

Common Examples of Genre

Genres could be divided into four major categories which also have further sub-categories. The four major categories are given below.

- Poetry: It could be categorized into further sub-categories such as epic, lyrical poetry, odes , sonnets , quatrains , free verse poems, etc.

- Fiction : It could be categorized into further sub-categories such as short stories, novels, skits, postmodern fiction, modern fiction, formal fiction, and so on.

- Prose : It could be further categorized into sub-genres or sub-categories such as essays, narrative essays, descriptive essays, autobiography , biographical writings, and so on.

- Drama: It could be categorized into tragedy, comedy, romantic comedy, absurd theatre, modern play, and so on.

Common Examples of Fiction Genre

In terms of literature, fiction refers to the prose of short stories, novellas , and novels in which the story originates from the writer’s imagination. These fictional literary forms are often categorized by genre, each of which features a particular style, tone , and storytelling devices and elements.

Here are some common examples of genre fiction and their characteristics:

- Literary Fiction : a work with artistic value and literary merit.

- Thriller : features dark, mysterious, and suspenseful plots.

- Horror : intended to scare and shock the reader while eliciting a sense of terror or dread; may feature scary entities such as ghosts, zombies, evil spirits, etc.

- Mystery : generally features a detective solving a case with a suspenseful plot and slowly revealing information for the reader to piece together.

- Romance : features a love story or romantic relationship; generally lighthearted, optimistic, and emotionally satisfying.

- Historical : plot takes place in the past with balanced realism and creativity; can feature actual historical figures, events, and settings.

- Western : generally features cowboys, settlers, or outlaws of the American Old West with themes of the frontier.

- Bildungsroman : story of a character passing from youth to adulthood with psychological and/or moral growth; the character becomes “educated” through loss, a journey, conflict , and maturation.

- Science Fiction : speculative stories derived and/or inspired by natural and social sciences; generally features futuristic civilizations, time travel, or space exploration.

- Dystopian : sub-genre of science fiction in which the story portrays a setting that may appear utopian but has a darker, underlying presence that is problematic.

- Fantasy : speculative stories with imaginary characters in imaginary settings; can be inspired by mythology or folklore and generally include magical elements.

- Magical Realism : realistic depiction of a story with magical elements that are accepted as “normal” in the universe of the story.

- Realism : depiction of real settings, people, and plots as a means of approaching the truth of everyday life and laws of nature.

Examples of Writers Associated with Specific Genre Fiction

Writers are often associated with a specific genre of fictional literature when they achieve critical acclaim, public notoriety, and/or commercial success with readers for a particular work or series of works. Of course, this association doesn’t limit the writer to that particular genre of fiction. However, being paired with a certain type of literature can last for an author’s entire career and beyond.

Here are some examples of writers that have become associated with specific fiction genre:

- Stephen King: horror

- Ray Bradbury : science fiction

- Jackie Collins: romance

- Toni Morrison: black feminism

- John le Carré: espionage

- Philippa Gregory: historical fiction

- Jacqueline Woodson: racial identity fiction

- Philip Pullman: fantasy

- Flannery O’Connor: Southern Gothic

- Shel Silverstein: children’s poetry

- Jonathan Swift : satire

- Larry McMurtry: western

- Virginia Woolf: feminism

- Raymond Chandler: detective fiction

- Colson Whitehead: Afrofuturism

- Gabriel García Márquez : magical realism

- Madeleine L’Engle: children’s fantasy fiction

- Agatha Christie : mystery

- John Green : young adult fiction

- Margaret Atwood: dystopian

Famous Examples of Genre in Other Art Forms

Most art forms feature genre as a means of identifying, differentiating, and categorizing the many forms and styles within a particular type of art. Though there are many crossovers when it comes to genre and no finite boundaries, most artistic works within a particular genre feature shared patterns , characteristics, and conventions.

Here are some famous examples of genres in other art forms:

- Music : rock, country, hip hop, folk, classical, heavy metal, jazz, blues

- Visual Art : portrait, landscape, still life, classical, modern, impressionism, expressionism

- Drama : comedy, tragedy, tragicomedy , melodrama , performance, musical theater, illusion

- Cinema : action, horror, drama, romantic comedy, western, adventure , musical, documentary, short, biopic, fantasy, superhero, sports

Examples of Genre in Literature

As a literary device, the genre is like an implied social contract between writers and their readers. This does not mean that writers must abide by all conventions associated with a specific genre. However, there are organizational patterns within a genre that readers tend to expect. Genre expectations allow readers to feel familiar with the literary work and help them to organize the information presented by the writer. In addition, keeping with genre conventions can establish a writer’s relationship with their readers and a framework for their literature.

Here are some examples of genres in literature and the conventions they represent:

Example 1: Macbeth by William Shakespeare

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow , Creeps in this petty pace from day to day To the last syllable of recorded time, And all our yesterdays have lighted fools The way to dusty death. Out, out , brief candle! Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player That struts and frets his hour upon the stage And then is heard no more: it is a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing.

The formal genre of this well-known literary work is Shakespearean drama or play. Macbeth can be sub-categorized as a literary tragedy in that the play features the elements of a classical tragic work. For example, Macbeth’s character aligns with the traits and path of a tragic hero –a protagonist whose tragic flaw brings about his downfall from power to ruin. This tragic arc of the protagonist often results in catharsis (emotional release) and potential empathy among readers and members of the audience .

In addition to featuring classical characteristics and conventions of the tragic genre, Shakespeare’s play also resonates with modern readers and audiences as a tragedy. In this passage, one of Macbeth’s soliloquies , his disillusionment, and suffering is made clear in that, for all his attempts and reprehensible actions at gaining power, his life has come to nothing. Macbeth realizes that death is inevitable, and no amount of power can change that truth. As Macbeth’s character confronts his mortality and the virtual meaninglessness of his life, readers and audiences are called to do the same. Without affirmation or positive resolution , Macbeth’s words are as tragic for readers and audiences as they are for his own character.

Like M a cbeth , Shakespeare’s tragedies are as currently relevant as they were when they were written. The themes of power, ambition, death, love, and fate incorporated in his tragic literary works are universal and timeless. This allows tragedy as a genre to remain relatable to modern and future readers and audiences.

Example 2: The Color Purple by Alice Walker

All my life I had to fight. I had to fight my daddy . I had to fight my brothers. I had to fight my cousins and my uncles. A girl child ain’t safe in a family of men. But I never thought I’d have to fight in my own house. She let out her breath. I loves Harpo, she say. God knows I do. But I’ll kill him dead before I let him beat me.

The formal genre of this literary work is novel. Walker’s novel can be sub-categorized within many fictional genres. This passage represents and validates its sub-classification within the genre of feminist fiction. Sofia’s character, at the outset, is assertive as a black woman who has been systematically marginalized in her community and family, and she expresses her independence from the dominance and control of men. Sofia is a foil character for Celie, the protagonist, who often submits to the power, control, and brutality of her husband. The juxtaposition of these characters indicates the limited options and harsh consequences faced by women with feminist ideals in the novel.

Unfortunately, Sofia’s determination to fight for herself leads her to be beaten close to death and sent to prison when she asserts herself in front of the white mayor’s wife. However, Sofia’s strong feminist traits have a significant impact on the other characters in the novel, and though she is not able to alter the systemic racism and subjugation she faces as a black woman, she does maintain her dignity as a feminist character in the novel.

Example 3: A Word to Husbands by Ogden Nash

To keep your marriage brimming With love in the loving cup, Whenever you’re wrong, admit it; Whenever you’re right, shut up.

The formal genre of this literary work is poetry. Nash’s poem would be sub-categorized within the genre of humor . The poet’s message to what is presumably his fellow husbands is witty, clear, and direct–through the wording and message of the last poetic line may be unexpected for many readers. In addition, the structure of the poem sets up the “punchline” at the end. The piece begins with poetic wording that appears to romanticize love and marriage, which makes the contrasting “base” language of the final line a satisfying surprise and ironic twist for the reader. The poet’s tone is humorous and light-hearted which also appeals to the characteristics and conventions of this genre.

Synonyms of Genre

Genre doesn’t have direct synonyms . A few close meanings are category, class, group, classification, grouping, head, heading, list, set, listing, and categorization. Some other words such as species, variety, family, school, and division also fall in the category of its synonyms.

Post navigation

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Challenges of Writing Theses and Dissertations in an EFL Context: Genre and Move Analysis of Abstracts Written by Turkish M.A. and Ph.D. Students

Serdar sükan.

1 Department of Modern Languages, Cyprus International University, Nicosia, Turkey

Behbood Mohammadzadeh

2 ELT Department, Faculty of Education, Cyprus International University, Nicosia, Turkey

Associated Data

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Writing a thesis or dissertation is a challenging procedure as it is one of the requirements of getting a graduate and postgraduate diploma. Writing an abstract like other parts of a thesis or dissertation has its criterion. For this reason, due to globalism, those abstracts written by non-native English speakers may lack some of the features of the abstract genre and move that must be included. This study examines the moves of M.A. and Ph.D. abstracts written by Turkish students between the 2009 and 2019 academic years on foreign language education at Cyprus International University. The data consisted of 50 abstracts chosen randomly from the ELT department. For the analysis, Hyland’s five-move model has been used. The study results reveal that 40 abstracts did not follow the five moves that Hyland has put forward. Moreover, it can be stated that the absence of some moves in the abstracts may cause restraint for readers to comprehend these studies in terms of communicative purposes.

Introduction

In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of students willing to get a diploma in their postgraduate fields. Thus, it became necessary to conduct research on the written abstracts as they are considered the essential section of the written theses that will give the reader an idea of the value of the whole dissertation. Hence, to draw attention to its importance and highlight the features that must be included in them, abstract analysis becomes more significant at this point. Especially for those writing their M.A. or Ph.D. abstracts, to guide them on what is needed. Any abstract that is going to be written needs systematic and organized work. The absence of these may lead to comprehension problems and may cause less attention. Poorly written abstracts can have unwanted results and may not receive enough credit or be read. To avoid this, what is expected is that a writer should have all the necessary skills to write good abstracts, which should be seen or understood from the moment one looks at the study. Genres and moves should be included and defined so that every reader understands each step clearly without reading the whole research. Genre is a literary term, and genre analysis is a sort of discourse done to check the reliability of communicative purposes. So, it includes an analysis of the style and text. Abstracts as genres have become a key tool for investigators because they offer them a chance to choose the appropriate study for their investigation ( Chen and Su, 2011 ; Yelland, 2011 ; Piqué-Noguera, 2012 ; Paré, 2017 ; Abdollahpour and Gholami, 2019 ; Anderson et al., 2021 ; Yu, 2021 ).