Research Philosophy & Paradigms

Positivism, Interpretivism & Pragmatism, Explained Simply

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | June 2023

Research philosophy is one of those things that students tend to either gloss over or become utterly confused by when undertaking formal academic research for the first time. And understandably so – it’s all rather fluffy and conceptual. However, understanding the philosophical underpinnings of your research is genuinely important as it directly impacts how you develop your research methodology.

In this post, we’ll explain what research philosophy is , what the main research paradigms are and how these play out in the real world, using loads of practical examples . To keep this all as digestible as possible, we are admittedly going to simplify things somewhat and we’re not going to dive into the finer details such as ontology, epistemology and axiology (we’ll save those brain benders for another post!). Nevertheless, this post should set you up with a solid foundational understanding of what research philosophy and research paradigms are, and what they mean for your project.

Overview: Research Philosophy

- What is a research philosophy or paradigm ?

- Positivism 101

- Interpretivism 101

- Pragmatism 101

- Choosing your research philosophy

What is a research philosophy or paradigm?

Research philosophy and research paradigm are terms that tend to be used pretty loosely, even interchangeably. Broadly speaking, they both refer to the set of beliefs, assumptions, and principles that underlie the way you approach your study (whether that’s a dissertation, thesis or any other sort of academic research project).

For example, one philosophical assumption could be that there is an external reality that exists independent of our perceptions (i.e., an objective reality), whereas an alternative assumption could be that reality is constructed by the observer (i.e., a subjective reality). Naturally, these assumptions have quite an impact on how you approach your study (more on this later…).

The research philosophy and research paradigm also encapsulate the nature of the knowledge that you seek to obtain by undertaking your study. In other words, your philosophy reflects what sort of knowledge and insight you believe you can realistically gain by undertaking your research project. For example, you might expect to find a concrete, absolute type of answer to your research question , or you might anticipate that things will turn out to be more nuanced and less directly calculable and measurable . Put another way, it’s about whether you expect “hard”, clean answers or softer, more opaque ones.

So, what’s the difference between research philosophy and paradigm?

Well, it depends on who you ask. Different textbooks will present slightly different definitions, with some saying that philosophy is about the researcher themselves while the paradigm is about the approach to the study . Others will use the two terms interchangeably. And others will say that the research philosophy is the top-level category and paradigms are the pre-packaged combinations of philosophical assumptions and expectations.

To keep things simple in this video, we’ll avoid getting tangled up in the terminology and rather focus on the shared focus of both these terms – that is that they both describe (or at least involve) the set of beliefs, assumptions, and principles that underlie the way you approach your study .

Importantly, your research philosophy and/or paradigm form the foundation of your study . More specifically, they will have a direct influence on your research methodology , including your research design , the data collection and analysis techniques you adopt, and of course, how you interpret your results. So, it’s important to understand the philosophy that underlies your research to ensure that the rest of your methodological decisions are well-aligned .

So, what are the options?

We’ll be straight with you – research philosophy is a rabbit hole (as with anything philosophy-related) and, as a result, there are many different approaches (or paradigms) you can take, each with its own perspective on the nature of reality and knowledge . To keep things simple though, we’ll focus on the “big three”, namely positivism , interpretivism and pragmatism . Understanding these three is a solid starting point and, in many cases, will be all you need.

Paradigm 1: Positivism

When you think positivism, think hard sciences – physics, biology, astronomy, etc. Simply put, positivism is rooted in the belief that knowledge can be obtained through objective observations and measurements . In other words, the positivist philosophy assumes that answers can be found by carefully measuring and analysing data, particularly numerical data .

As a research paradigm, positivism typically manifests in methodologies that make use of quantitative data , and oftentimes (but not always) adopt experimental or quasi-experimental research designs. Quite often, the focus is on causal relationships – in other words, understanding which variables affect other variables, in what way and to what extent. As a result, studies with a positivist research philosophy typically aim for objectivity, generalisability and replicability of findings.

Let’s look at an example of positivism to make things a little more tangible.

Assume you wanted to investigate the relationship between a particular dietary supplement and weight loss. In this case, you could design a randomised controlled trial (RCT) where you assign participants to either a control group (who do not receive the supplement) or an intervention group (who do receive the supplement). With this design in place, you could measure each participant’s weight before and after the study and then use various quantitative analysis methods to assess whether there’s a statistically significant difference in weight loss between the two groups. By doing so, you could infer a causal relationship between the dietary supplement and weight loss, based on objective measurements and rigorous experimental design.

As you can see in this example, the underlying assumptions and beliefs revolve around the viewpoint that knowledge and insight can be obtained through carefully controlling the environment, manipulating variables and analysing the resulting numerical data . Therefore, this sort of study would adopt a positivistic research philosophy. This is quite common for studies within the hard sciences – so much so that research philosophy is often just assumed to be positivistic and there’s no discussion of it within the methodology section of a dissertation or thesis.

Paradigm 2: Interpretivism

If you can imagine a spectrum of research paradigms, interpretivism would sit more or less on the opposite side of the spectrum from positivism. Essentially, interpretivism takes the position that reality is socially constructed . In other words, that reality is subjective , and is constructed by the observer through their experience of it , rather than being independent of the observer (which, if you recall, is what positivism assumes).

The interpretivist paradigm typically underlies studies where the research aims involve attempting to understand the meanings and interpretations that people assign to their experiences. An interpretivistic philosophy also typically manifests in the adoption of a qualitative methodology , relying on data collection methods such as interviews , observations , and textual analysis . These types of studies commonly explore complex social phenomena and individual perspectives, which are naturally more subjective and nuanced.

Let’s look at an example of the interpretivist approach in action:

Assume that you’re interested in understanding the experiences of individuals suffering from chronic pain. In this case, you might conduct in-depth interviews with a group of participants and ask open-ended questions about their pain, its impact on their lives, coping strategies, and their overall experience and perceptions of living with pain. You would then transcribe those interviews and analyse the transcripts, using thematic analysis to identify recurring themes and patterns. Based on that analysis, you’d be able to better understand the experiences of these individuals, thereby satisfying your original research aim.

As you can see in this example, the underlying assumptions and beliefs revolve around the viewpoint that insight can be obtained through engaging in conversation with and exploring the subjective experiences of people (as opposed to collecting numerical data and trying to measure and calculate it). Therefore, this sort of study would adopt an interpretivistic research philosophy. Ultimately, if you’re looking to understand people’s lived experiences , you have to operate on the assumption that knowledge can be generated by exploring people’s viewpoints, as subjective as they may be.

Paradigm 3: Pragmatism

Now that we’ve looked at the two opposing ends of the research philosophy spectrum – positivism and interpretivism, you can probably see that both of the positions have their merits , and that they both function as tools for different jobs . More specifically, they lend themselves to different types of research aims, objectives and research questions . But what happens when your study doesn’t fall into a clear-cut category and involves exploring both “hard” and “soft” phenomena? Enter pragmatism…

As the name suggests, pragmatism takes a more practical and flexible approach, focusing on the usefulness and applicability of research findings , rather than an all-or-nothing, mutually exclusive philosophical position. This allows you, as the researcher, to explore research aims that cross philosophical boundaries, using different perspectives for different aspects of the study .

With a pragmatic research paradigm, both quantitative and qualitative methods can play a part, depending on the research questions and the context of the study. This often manifests in studies that adopt a mixed-method approach , utilising a combination of different data types and analysis methods. Ultimately, the pragmatist adopts a problem-solving mindset , seeking practical ways to achieve diverse research aims.

Let’s look at an example of pragmatism in action:

Imagine that you want to investigate the effectiveness of a new teaching method in improving student learning outcomes. In this case, you might adopt a mixed-methods approach, which makes use of both quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis techniques. One part of your project could involve comparing standardised test results from an intervention group (students that received the new teaching method) and a control group (students that received the traditional teaching method). Additionally, you might conduct in-person interviews with a smaller group of students from both groups, to gather qualitative data on their perceptions and preferences regarding the respective teaching methods.

As you can see in this example, the pragmatist’s approach can incorporate both quantitative and qualitative data . This allows the researcher to develop a more holistic, comprehensive understanding of the teaching method’s efficacy and practical implications , with a synthesis of both types of data . Naturally, this type of insight is incredibly valuable in this case, as it’s essential to understand not just the impact of the teaching method on test results, but also on the students themselves!

Wrapping Up: Philosophies & Paradigms

Now that we’ve unpacked the “big three” research philosophies or paradigms – positivism, interpretivism and pragmatism, hopefully, you can see that research philosophy underlies all of the methodological decisions you’ll make in your study. In many ways, it’s less a case of you choosing your research philosophy and more a case of it choosing you (or at least, being revealed to you), based on the nature of your research aims and research questions .

- Research philosophies and paradigms encapsulate the set of beliefs, assumptions, and principles that guide the way you, as the researcher, approach your study and develop your methodology.

- Positivism is rooted in the belief that reality is independent of the observer, and consequently, that knowledge can be obtained through objective observations and measurements.

- Interpretivism takes the (opposing) position that reality is subjectively constructed by the observer through their experience of it, rather than being an independent thing.

- Pragmatism attempts to find a middle ground, focusing on the usefulness and applicability of research findings, rather than an all-or-nothing, mutually exclusive philosophical position.

If you’d like to learn more about research philosophy, research paradigms and research methodology more generally, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach blog . Alternatively, if you’d like hands-on help with your research, consider our private coaching service , where we guide you through each stage of the research journey, step by step.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

15 Comments

was very useful for me, I had no idea what a philosophy is, and what type of philosophy of my study. thank you

Thanks for this explanation, is so good for me

You contributed much to my master thesis development and I wish to have again your support for PhD program through research.

the way of you explanation very good keep it up/continuous just like this

Very precise stuff. It has been of great use to me. It has greatly helped me to sharpen my PhD research project!

Very clear and very helpful explanation above. I have clearly understand the explanation.

Very clear and useful. Thanks

Thanks so much for your insightful explanations of the research philosophies that confuse me

I would like to thank Grad Coach TV or Youtube organizers and presenters. Since then, I have been able to learn a lot by finding very informative posts from them.

thank you so much for this valuable and explicit explanation,cheers

Hey, at last i have gained insight on which philosophy to use as i had little understanding on their applicability to my current research. Thanks

Tremendously useful

thank you and God bless you. This was very helpful, I had no understanding before this.

USEFULL IN DEED!

Explanations to the research paradigm has been easy to follow. Well understood and made my life easy.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Research Philosophy

Research philosophy is a vast topic and here we will not be discussing this topic in great details. Research philosophy is associated with assumption, knowledge and nature of the study. It deals with the specific way of developing knowledge. This matter needs to be addressed because researchers may have different assumptions about the nature of truth and knowledge and philosophy helps us to understand their assumptions.

In business and economics dissertations at Bachelor’s level, you are not expected to discuss research philosophy in a great level of depth, and about one page in methodology chapter devoted to research philosophy usually suffices. For a business dissertation at Master’s level, on the other hand, you may need to provide more discussion of the philosophy of your study. But even there, about two pages of discussions are usually accepted as sufficient by supervisors.

Discussion of research philosophy in your dissertation should include the following:

- You need to specify the research philosophy of your study. Your research philosophy can be pragmatism , positivism , realism or interpretivism as discussed below in more details.

- The reasons behind philosophical classifications of the study need to be provided.

- You need to discuss the implications of your research philosophy on the research strategy in general and the choice of primary data collection methods in particular.

The Essence of Research Philosophy

Research philosophy deals with the source, nature and development of knowledge [1] . In simple terms, research philosophy is belief about the ways in which data about a phenomenon should be collected, analysed and used.

Although the idea of knowledge creation may appear to be profound, you are engaged in knowledge creation as part of completing your dissertation. You will collect secondary and primary data and engage in data analysis to answer the research question and this answer marks the creation of new knowledge.

In respect to business and economics philosophy has the following important three functions [2] :

- Demystifying : Exposing, criticising and explaining the unsustainable assumptions, inconsistencies and confusions these may contain.

- Informing : Helping researchers to understand where they stand in the wider field of knowledge-producing activities, and helping to make them aware of potentialities they might explore.

- Method-facilitating : Dissecting and better understanding the methods which economists or, more generally, scientists do, or could, use, and thereby to refine the methods on offer and/or to clarify their conditions of usage.

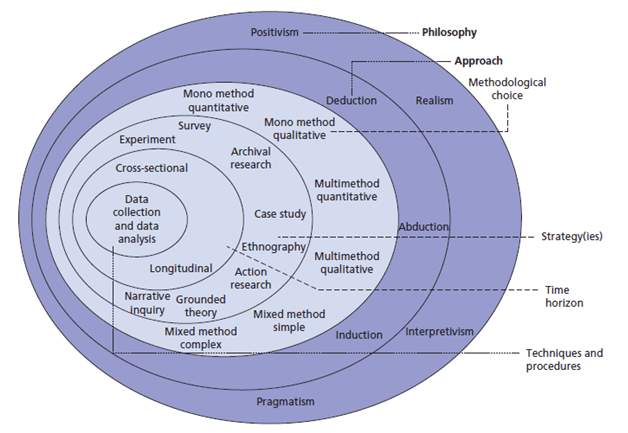

In essence, addressing research philosophy in your dissertation involves being aware and formulating your beliefs and assumptions. As illustrated in figure below, the identification of research philosophy is positioned at the outer layer of the ‘research onion’. Accordingly it is the first topic to be clarified in research methodology chapter of your dissertation.

Research philosophy in the ‘research onion’ [2]

Each stage of the research process is based on assumptions about the sources and the nature of knowledge. Research philosophy will reflect the author’s important assumptions and these assumptions serve as base for the research strategy. Generally, research philosophy has many branches related to a wide range of disciplines. Within the scope of business studies in particular there are four main research philosophies:

- Interpretivism (Interpretivist)

The Choice of Research Philosophy

The choice of a specific research philosophy is impacted by practical implications. There are important philosophical differences between studies that focus on facts and numbers such as an analysis of the impact of foreign direct investment on the level of GDP growth and qualitative studies such as an analysis of leadership style on employee motivation in organizations.

The choice between positivist and interpretivist research philosophies or between quantitative and qualitative research methods has traditionally represented a major point of debate. However, the latest developments in the practice of conducting studies have increased the popularity of pragmatism and realism philosophies as well.

Moreover, as it is illustrated in table below, there are popular data collection methods associated with each research philosophy.

Research philosophies and data collection methods [3]

My e-book, The Ultimate Guide to Writing a Dissertation in Business Studies: a step by step assistance contains discussions of theory and application of research philosophy. The e-book also explains all stages of the research process starting from the selection of the research area to writing personal reflection. Important elements of dissertations such as research philosophy , research approach , research design , methods of data collection and data analysis are explained in this e-book in simple words.

John Dudovskiy

[1] Bajpai, N. (2011) “Business Research Methods” Pearson Education India

[2] Tsung, E.W.K. (2016) “The Philosophy of Management Research” Routledge

[3] Table adapted from Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2012) “Research Methods for Business Students” 6 th edition, Pearson Education Limited

Integration and Implementation Insights

A community blog and repository of resources for improving research impact on complex real-world problems

A guide to ontology, epistemology, and philosophical perspectives for interdisciplinary researchers

By Katie Moon and Deborah Blackman

How can understanding philosophy improve our research? How can an understanding of what frames our research influence our choices? Do researchers’ personal thoughts and beliefs shape research design, outcomes and interpretation?

These questions are all important for social science research. Here we present a philosophical guide for scientists to assist in the production of effective social science (adapted from Moon and Blackman, 2014).

Understanding philosophy is important because social science research can only be meaningfully interpreted when there is clarity about the decisions that were taken that affect the research outcomes. Some of these decisions are based, not always knowingly, on some key philosophical principles, as outlined in the figure below.

Philosophy provides the general principles of theoretical thinking, a method of cognition, perspective and self-awareness, all of which are used to obtain knowledge of reality and to design, conduct, analyse and interpret research and its outcomes. The figure below shows three main branches of philosophy that are important in the sciences and serves to illustrate the differences between them.

(Source: Moon and Blackman 2014)

The first branch is ontology, or the ‘study of being’, which is concerned with what actually exists in the world about which humans can acquire knowledge. Ontology helps researchers recognize how certain they can be about the nature and existence of objects they are researching. For instance, what ‘truth claims’ can a researcher make about reality? Who decides the legitimacy of what is ‘real’? How do researchers deal with different and conflicting ideas of reality?

To illustrate, realist ontology relates to the existence of one single reality which can be studied, understood and experienced as a ‘truth’; a real world exists independent of human experience. Meanwhile, relativist ontology is based on the philosophy that reality is constructed within the human mind, such that no one ‘true’ reality exists. Instead, reality is ‘relative’ according to how individuals experience it at any given time and place.

Epistemology

The second branch is epistemology, the ‘study of knowledge’. Epistemology is concerned with all aspects of the validity, scope and methods of acquiring knowledge, such as a) what constitutes a knowledge claim; b) how can knowledge be acquired or produced; and c) how the extent of its transferability can be assessed. Epistemology is important because it influences how researchers frame their research in their attempts to discover knowledge.

By looking at the relationship between a subject and an object we can explore the idea of epistemology and how it influences research design. Objectivist epistemology assumes that reality exists outside, or independently, of the individual mind. Objectivist research is useful in providing reliability (consistency of results obtained) and external validity (applicability of the results to other contexts).

Constructionist epistemology rejects the idea that objective ‘truth’ exists and is waiting to be discovered. Instead, ‘truth’, or meaning, arises in and out of our engagement with the realities in our world. That is, a ‘real world’ does not preexist independently of human activity or symbolic language. The value of constructionist research is in generating contextual understandings of a defined topic or problem.

Subjectivist epistemology relates to the idea that reality can be expressed in a range of symbol and language systems, and is stretched and shaped to fit the purposes of individuals such that people impose meaning on the world and interpret it in a way that makes sense to them. For example, a scuba diver might interpret a shadow in the water according to whether they were alerted to a shark in the area (the shark), waiting for a boat (the boat), or expecting a change in the weather (clouds). The value of subjectivist research is in revealing how an individual’s experience shapes their perception of the world.

Philosophical perspectives

Stemming from ontology (what exists for people to know about) and epistemology (how knowledge is created and what is possible to know) are philosophical perspectives, a system of generalized views of the world, which form beliefs that guide action.

Philosophical perspectives are important because, when made explicit, they reveal the assumptions that researchers are making about their research, leading to choices that are applied to the purpose, design, methodology and methods of the research, as well as to data analysis and interpretation. At the most basic level, the mere choice of what to study in the sciences imposes values on one’s subject.

Understanding the philosophical basis of science is critical in ensuring that research outcomes are appropriately and meaningfully interpreted. With an increase in interdisciplinary research, an examination of the points of difference and intersection between the philosophical approaches can generate critical reflection and debate about what we can know, what we can learn and how this knowledge can affect the conduct of science and the consequent decisions and actions.

How does your philosophical standpoint affect your research? What are your experiences of clashing philosophical perspectives in interdisciplinary research? How did you become aware of them and resolve them? Do you think that researchers need to recognize different philosophies in interdisciplinary research teams?

To find out more : Moon, K., and Blackman, D. (2014). A Guide to Understanding Social Science Research for Natural Scientists. Conservation Biology , 28 : 1167-1177. Online: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cobi.12326/full

Biography: Katie Moon is a Post Doctoral Research Fellow at the University of New South Wales, Canberra. She is also an adjunct at the Institute for Applied Ecology at the University of Canberra. She has worked in the environmental policy arena for 17 years within Australia and Europe, in government, the private sector and academia. Her research focuses on how the right policy instruments can be paired to the right people; the role of evidence in policy development and implementation; and how to increase policy implementation success .

Biography: Deborah Blackman is a Professor in Public Sector Management Strategy and Deputy Director of the Public Service Research Group at the University of New South Wales, Canberra. She researches knowledge transfer in a range of applied, real world contexts. The common theme of her work is creating new organisational conversations in order to improve organisational effectiveness. This has included strengthening the performance management framework in the Australian Public Service; the role of social capital in long-term disaster recovery; and developing a new diagnostic model to support effective joined-up working in whole of government initiatives .

Related posts:

A guide for interdisciplinary researchers: Adding axiology alongside ontology and epistemology by Peter Deane https://i2insights.org/2018/05/22/axiology-and-interdisciplinarity/

Epistemological obstacles to interdisciplinary research by Evelyn Brister https://i2insights.org/2017/10/31/epistemology-and-interdisciplinarity/

Transforming transdisciplinarity: Interweaving the philosophical with the pragmatic to move beyond either/or thinking by Katie Ross and Cynthia Mitchell https://i2insights.org/2018/11/13/transdisciplinarity-and-either-or-thinking/

What is the role of theory in transdisciplinary research? by Workshop Group on Theory at 2015 Basel International Transdisciplinary Conference http://i2insights.org/2016/02/17/role-of-theory-in-transdisciplinary-research/

Share this:

13 thoughts on “a guide to ontology, epistemology, and philosophical perspectives for interdisciplinary researchers”.

Hi Katie and Deborah, First of all want to thank you for such incredible synthesis! Then I want to ask you, how can we situate a paradigm or an school or though in this map? For example, where do you think we can situate the complex paradigm of Edgar Morin? in between the relativistic ontology? or critical theory? thanks in advance.

- Pingback: creative drift: on being natural - bob's thoughts, images, feelings

The table summary is admirable. All your write is very nice

- Pingback: A guide to ontology, epistemology, and philosophical perspectives for interdisciplinary researchers | Learning Research Methods

- Pingback: Week 2 – Ontology and Epistemology – Research Methods

Great post! I really like the table and find it a very helpful illustration!

Hi Kate, thank you very much for helping out. I understand the subject matter more now than before Olushola

- Pingback: RES 701, Week 2, Ontology & Epistemology – RES701 Research Methods

Thanks so much for the debate and discussion around the blog post. Machiel is right in pointing out that the blog post (and the article it is based on) was intended as a conversation piece, and we’re pleased that a useful conversation is taking place. The resources and links are very helpful, philosophy is a fascinating discipline and the opportunity to learn and expand our thinking is endless.

We tried to make it clear in the article the blog post is based on that we wanted to bring attention to philosophy; it was obviously impossible to do the discipline of philosophy any real justice within 6,000 words. We wanted to start a conversation: “The purpose of the guide is to open the door to social science research and thus demonstrate that scientists can bring different and legitimate principles, assumptions, and interpretations to their research.”

As Jessica and Melissa point out, it can be challenging to offer social research to a natural science community that typically adopts a narrow philosophical position (e.g. objectivist). The paper was intended to encourage natural scientists to consider alternative ways of generating knowledge, particularly about the human, as opposed to natural, world.

We accept unequivocally that the framework does not get close to accommodating the depth and diversity of philosophy. Adam, we agree that the approach we have taken may not resonate with some philosophers, but we wanted to communicate with a particular audience (conservation scientists) and so we defined ontologies and epistemologies (and posited them relative to one another) that are most commonly observed within this discipline and that might be best understood by the audience. We tried to identify points of difference between ontologies, epistemologies and philosophical perspectives in an attempt to explain how they can influence research design. In the article, we use a case of deforestation in rainforests to demonstrate how different positions can influence the nature of the research questions and outcomes, including the assumptions that will be made.

We did explain in the introduction to our paper the limitations of our approach: “The multifaceted nature and interpretation of each of the concepts we present in our guide means they can be combined in a diversity of ways (see also Lincoln & Guba 2000; Schwandt 2000; Evely et al. 2008; H¨oijer 2008; Cunliffe 2011; Tang 2011). Therefore, our guide represents just one example of how the elements (i.e., different positions within the main branches of philosophy) of social research can apply specifically to conservation science. We recognize that by distilling and defining the elements in a simplified way we have necessarily constrained argument and debate surrounding each element. Furthermore, the guide had to have some structure. In forming this structure, we do not suggest that researchers must consider first their ontological and then their epistemological position and so on; they may well begin by exploring their philosophical perspective.”

This point comes back to Bruce’s comment, about pragmatic approaches to research. Often researchers pick and choose between a range of options that will allow them to define and answer their research questions in a way that makes most sense to them. We make this point in the paper: “Each perspective is characterized by an often wide ranging pluralism, which reflects the complex evolution of philosophy and the varied contributions of philosophers through time (Crotty 1998). All ontologies, epistemologies, and philosophical perspectives are characterized by this pluralism, including the prevailing (post) positivist approach of the natural sciences. It is common for more than one philosophical perspective to resonate with researchers and for researchers to change their perspective (and thus epistemological and ontological positions) toward their research over time (Moses & Knutsen 2012). Thus, scientists do not necessarily commit to one philosophical perspective and all associated characteristics (Bietsa 2010).”

We tried to anticipate concerns that scholars of philosophy might have with our rather reductionist approach, but felt that the more important contribution to make was to bring attention to alternative worldviews, and highlight the importance of philosophy in generating any type of knowledge.

With respect to the characterization of epistemologies, we adopted a continuum provided by Crotty (1998) that focuses on the relationship between the subject and the object. Again, this choice was made on the basis of our audience, to demonstrate that different types of relationship can exist between subject and object

This blog post has generated an interesting discussion on the Association for Interdisciplinary Studies listserv ([email protected]). Selected excerpts below.

Adam Potthast: I hate to make one of my first posts to this list critical without the time to correct some of the errors, but I don’t think you’d see many philosophers agreeing with the characterizations of philosophical views in this post. The infographic strongly mischaracterizes a lot of these positions, and the section on epistemology doesn’t map on to any of the standard understandings of epistemology in the discipline of philosophy. I’d caution against thinking of it as a reliable source to the philosophy behind science.

Gabriele Bammer: Thanks Adam for raising the alarm. It would be great if you and/or others who have problems with this post would spell out your criticisms – not only via this listserv, but (more importantly from my perspective) in a comment on the blog itself. Non-philosophers are hungry for a version of epistemology, ontology etc that they can understand and use and this blog post (and the paper it is based on) address this need. If it is seriously misleading though, that’s obviously a problem. It’s important that this is pointed out and that better alternatives are offered. I appreciate that time is an issue for everyone – anything you can do will be appreciated.

Stuart Henry: Well a good start, so we don’t reinvent the wheel again is James Welch’s article: https://oakland.edu/Assets/upload/docs/AIS/Issues-in-Interdisciplinary-Studies/2009-Volume-27/05_Vol_27_pp_35_69_Interdisciplinarity_and_the_History_of_Western_Epistemology_(James_Welch_IV) .pdf

Gabriele Bammer: Thanks Stuart, I may be missing something, but it seems to me that Welch’s article covers different terrain, being more about the philosophy underpinning interdisciplinarity. What Moon and Blackman provide is a quick guide to understanding people’s different philosophical positions, so that if you are working in a team, for example, you can better understand why someone sees the world differently. The Toolbox developed by Eigenbrode, O’Rourke and others provides a practical way of uncovering these differences.

Julie Thompson Klein: Good point Gabriele about the value of the Toolbox, though people still need the kind of background you’re aiming to provide.

Machiel Keestra: Although I agree that the blog post should perhaps not so much be taken to offer a current representation of the main positions in philosophy of science or about the interconnections between epistemological and ontological positions, I think it does a nice job in offering a conversation piece: what are relevant positions and options that people might -implicitly– take and how are they different from other positions. Given the modest ambitions of the authors, I think that is a fair result.

In addition to the interesting approach offered by the Toolbox Project, an alternative is presented in Jan Schmidt’s Towards a philosophy of interdisciplinarity: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10202-007-0037-8 In our Introduction to interdisciplinary research, I’ve inserted an all-too brief philosophy of science which should help to raise some understanding of this difficult issue as well: https://www.academia.edu/22420234/An_Introduction_to_Interdisciplinary_Research._Theory_and_Practice

Lovely work! Thank you. I am also initially trained as a natural scientist, and now consider myself a ‘social-ecological researcher’ and have had to do a lot of learning about ontologies, epistemologies etc. I think I might use this paper as a discussion paper in our department as I think it is crucial for interdisciplinarians to understand these issues.

Kia ora Katie and Debbie, great post! I am a biophysical scientist who has come to social science and one of the struggles is being able to place the new and relevant concepts about questions that we don’t necessarily ask as biophysical scientists. Your table is a really useful aid to this – I immediately sent it to all my colleagues! It also makes it clearer to me how I can use the concept of triangulation that Bruce alluded to in his reply. So thank you for explaining so concisely. Thanks, Melissa

Hi Katie and Deborah,

Thank you for that discussion. I think that you have created a really useful table showing the philosophical continuums/polarities, how the various ontological and epistemological positions relate to each other, and the importance for researchers to be aware of them. In my own research practice, I am not committed to any one particular philosophical theory or perspective. They all appear to be true to some degree, that is, in some conceivable context – even though some of the concepts and philosophical positions appear, in the extreme form of their statement, to be contradictory, that is, if one end of a continuum/polarity is true then by implication it seems the other must be false – thus creating a quandary of research perspective. Hence the attraction, for me, of the application of a multiplicity of methods, approaches and philosophical perspectives – as and when they seem able to give ontological or epistemological insight – with triangulation between the results of the disparate approaches as the temporary arbiter of an evolving meaning and truth. This might be considered a pragmatic, perhaps even an opportunistic, approach to conducting science. However, as the old adage goes “the proof is in the pudding” – how useful is the knowledge obtained?

cheers Bruce

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from Integration and Implementation Insights

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Management Culture and Corporate Social Responsibility

Philosophy and Paradigm of Scientific Research

Submitted: 17 August 2017 Reviewed: 21 August 2017 Published: 18 April 2018

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.70628

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Monograph

Management Culture and Corporate Social Responsibility

Authored by Pranas ?ukauskas, Jolita Vveinhardt and Regina Andriukaitien?

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

18,821 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

Overall attention for this chapters

Before carrying out the empirical analysis of the role of management culture in corporate social responsibility, identification of the philosophical approach and the paradigm on which the research carried out is based is necessary. Therefore, this chapter deals with the philosophical systems and paradigms of scientific research, the epistemology, evaluating understanding and application of various theories and practices used in the scientific research. The key components of the scientific research paradigm are highlighted. Theories on the basis of which this research was focused on identification of the level of development of the management culture in order to implement corporate social responsibility are identified, and the stages of its implementation are described.

- philosophy of scientific research

- epistemology

- values and beliefs

- basic beliefs

- formal and informal factors

Author Information

Pranas žukauskas.

- Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania

Jolita Vveinhardt *

Regina andriukaitienė.

- Marijampolė College, Lithuania

- Lithuanian Sports University, Lithuania

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction

1.1. relevance of the research.

Scientific research philosophy is a system of the researcher’s thought, following which new, reliable knowledge about the research object is obtained. In other words, it is the basis of the research, which involves the choice of research strategy, formulation of the problem, data collection, processing, and analysis. The paradigm of scientific research, in turn, consists of ontology, epistemology methodology, and methods. Methodological choice, according to Holden and Lynch [ 1 ], should be related to the philosophical position of the researcher and the analyzed social science phenomenon. In the field of research, several philosophical approaches are possible; however, according to the authors, more extreme approaches can be delimiting. Only intermediary philosophical approach allows the researcher to reconcile philosophy, methodology, and the problem of research. However, Crossan [ 2 ] drew attention to the fact that sometimes there is a big difference between quantitative and qualitative research philosophies and methods, and triangulation of modern research methods is common. It is therefore very important to understand the strengths and weaknesses of each approach. This allows preparing for the research and understanding the analyzed problem better. The theories of research philosophy and paradigms, on the basis of which the research in the monograph focuses on identifying the level of development of the management culture in order to implement corporate social responsibility, are presented in figures that distinguish the levels of organizational culture and their interaction, that is, corporate social responsibility stages, which reflect the philosophy and paradigm of this research.

The problem of the research is raised by the following questions: what are the essential principles of research philosophy and paradigm? and how to apply them to form the research position?

The level of problem exploration. The chapter presents the thoughts of the authors who analyze research philosophy [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ] and paradigm [ 3 , 9 , 10 , 11 ], relating them to the key researches of this monograph.

The object of this study is to understand essential principles of research philosophy and paradigm.

The purpose of the research is to analyze the essential principles of research philosophy and paradigm, substantiating the position of the key researches of this monograph.

The objectives of this research are (1) to discuss the fundamental aspects of research philosophy and paradigm; and (2) to substantiate the position of culture management and corporate social responsibility research.

Methods of the research. The descriptive method, analysis of academic sources, generalization, and systematization were used as the methods in this study. Graphical representation and modeling methods were used to convey the position of the research.

2. Philosophy and paradigm of scientific research

2.1. scientific research philosophy.

Each researcher is guided by their own approach to the research itself. It is said that Mill [ 12 ] was the first who called representatives of social sciences to compete with ancient sciences, promising that if his advice was followed, the sudden maturity in these sciences would appear. In the same way as their education appeared from philosophical and theological frames that limited them. Social sciences accepted this advice (probably to a level that would have surprised Mill himself if he were alive) for other reasons as well [ 3 , 13 ]. Research philosophy can be defined as the development of research assumption, its knowledge, and nature [ 7 ]. The assumption is perceived as a preliminary statement of reasoning, but it is based on the philosophizing person’s knowledge and insights that are born as a product of intellectual activity. Hitchcock and Hughes [ 4 ] also claim that research stems from assumptions. This means that different researchers may have different assumptions about the nature of truth and knowledge and its acquisition [ 6 ]. Scientific research philosophy is a method which, when applied, allows the scientists to generate ideas into knowledge in the context of research. There are four main trends of research philosophy that are distinguished and discussed in the works by many authors: the positivist research philosophy, interpretivist research philosophy, pragmatist research philosophy, and realistic research philosophy.

Positivist research philosophy . It claims that the social world can be understood in an objective way. In this research philosophy, the scientist is an objective analyst and, on the basis of it, dissociates himself from personal values and works independently.

The opposite to the above-mentioned research philosophy is the interpretivist research philosophy, when a researcher states that on the basis of the principles it is not easy to understand the social world. Interpretivist research philosophy says that the social world can be interpreted in a subjective manner. The greatest attention here is given to understanding of the ways through which people experience the social world. Interpretivist research philosophy is based on the principle which states that the researcher performs a specific role in observing the social world. According to this research philosophy, the research is based and depends on what the researcher’s interests are.

Pragmatist research philosophy deals with the facts. It claims that the choice of research philosophy is mostly determined by the research problem. In this research philosophy, the practical results are considered important [ 5 ]. In addition, according to Alghamdi and Li [ 14 ], pragmatism does not belong to any philosophical system and reality. Researchers have freedom of choice. They are “free” to choose the methods, techniques, and procedures that best meet their needs and scientific research aims. Pragmatists do not see the world as absolute unity. The truth is what is currently in action; it does not depend on the mind that is not subject to reality and the mind dualism.

Realistic research philosophy [ 5 ] is based on the principles of positivist and interpretivist research philosophies. Realistic research philosophy is based on assumptions that are necessary for the perception of subjective nature of the human.

2.1.1. Scientific research paradigm

The scientific research paradigm helps to define scientific research philosophy. Literature on scientific research claims that the researcher must have a clear vision of paradigms or worldview which provides the researcher with philosophical, theoretical, instrumental, and methodological foundations. Research of paradigms depends on these foundations [ 14 ]. According to Cohen et al. [ 6 ], the scientific research paradigm can be defined as a wide structure encompassing perception, beliefs, and awareness of different theories and practices used to carry out scientific research. The scientific research paradigm is also characterized by a precise procedure consisting of several stages. The researcher, getting over the mentioned stages, creates a relationship between research aims and questions. The term of paradigm is closely related to the “normal science” concept. Scientists who work within the same paradigm frame are guided by the same rules and standards of scientific practice. “That is how the scientific community supports itself,” claims Ružas [ 15 ] citing the French post-positivist Kuhn [ 16 ].

The scientific research paradigm and philosophy depend on various factors, such as the individual's mental model, his worldview, different perception, many beliefs, and attitudes related to the perception of reality, etc. Researchers' beliefs and values are important in this concept in order to provide good arguments and terminology for obtaining reliable results. The researcher’s position in certain cases can have a significant impact on the outcome of the research [ 11 ]. Norkus [ 17 ] draws attention to the fact that the specialists of some subjects of natural science are able by using free discussion to come to general conclusions the innovations of which are really “discoveries,” some of them are significant and some are not. Such consensus is difficult to achieve in social sciences. Academic philosophers claim this fact by the statement that “multi-paradigmatism” is characteristic to the humanities and social sciences, i.e., the permanent coexistence and competition of many different theoretical paradigms.

Gliner and Morgan [ 9 ] describe the scientific research paradigm as the approach or thinking about the research, the accomplishing process, and the method of implementation. It is not a methodology, but rather a philosophy which provides the process of carrying out research, i.e., directs the process of carrying out research in a particular direction. Ontology, epistemology, methodology, and methods describe all research paradigms [ 3 , 10 , 14 ]. Easterby-Smith et al. [ 18 ] discuss three main components of the scientific research paradigm, or three ways in order to understand the philosophy of research ( Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Three components of scientific research paradigm.

Source: Easterby-Smith et al. [ 18 ].

The three paradigms (positivist, constructivist, and critical) which are different by ontological, epistemological, and methodological aspects are also often included in the classification of scholarly paradigms [ 19 ]. In addition, Mackenzie and Knipe [ 20 ] present unique analysis of research paradigms with the most common terms associated with them. According to Mackenzie and Knipe [ 20 ], the description of the terminology is consistent with the descriptions by Leedy and Ormrod [ 21 ] and Schram [ 22 ] appearing in literature most often, despite the fact that it is general rather than specific to disciplines or research. Somekh and Lewin [ 23 ] describe methodology as a set of methods and rules, on the basis of which the research is carried out, and as “the principles, theories and values underlying certain approach to research.” In Walter’s [ 24 ] opinion, methodology is the support research structure, which is influenced by the paradigm in which our theoretical perspective “lives” or develops. Mackenzie and Knipe [ 20 ] state that in most common definitions, it is claimed that methodology is a general approach to research related to the paradigm or theoretical foundation, and the method includes the systematic ways, procedures, or tools used for data collection and analysis ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Paradigms: terminology, methods, and means of data collection. Source: Adapted by the authors: Mackenzie and Knipe [ 20 ], Mertens [ 25 ], Creswell [ 10 ].

Mackenzie and Knipe [ 20 ] state that it is the paradigm and the research question that should determine which data collection and analysis methods (qualitative/quantitative or mixed) would be the most appropriate for research. In this way, the researchers do not become “the researchers of quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods,” but they adapt the data collection and analysis method that is most suitable for a specific research. According to the authors, the use of several methods may be possible to adapt to any and all paradigms instead of having one single method that could potentially dilute and unnecessarily limit the depth and richness of the research project.

The scientific paradigm refers to a range of problems, by presenting ways of their solutions. The methods are detailed and compared in Table 2 with regard to the basic paradigms.

Table 2.

Comparison of the main paradigms with regard to ontology, epistemology, and research methods.

Source: Adapted by the authors according to Hitchcock and Hughes [ 4 ], Kuhn [ 16 ], Mackenzie and Knipe [ 20 ], Walker and Evers [ 26 ], Brewerton and Millward [ 27 ], Delanty and Strydom [ 28 ], Bagdonas [ 29 ], Phiri [ 30 ], etc.

Although the paradigm has already been mentioned, but for the researcher, in order to understand different combinations of research methods, it is necessary to analyze the basic concepts and to perceive the philosophical position of research problems.

Kuhn [ 16 ] introduced the concept of paradigm (gr. paradeigma—example model) in the science philosophy. Kuhn calls a paradigm a generally accepted scientific knowledge achievement which provides the scientists with problem raising and solving methods for a period of time. According to the author, when some old ideas are being replaced by the new ones, i.e., better, more advanced, etc., then the progress in science is stated. In natural sciences, this is going on confirming the hypothesis by logical arguments and empirical research. When the scientific community reaches a consensus, there appears accepted theory on its basis [ 16 ]. Bagdonas [ 29 ] describes a paradigm as the whole of theoretical and methodological regulations, that is, regulations adopted by the scientific community at a certain stage of development of science and applied as an example, the model, the standard for scientific research, interpretations, evaluation, and hypotheses to understand and solve objectives arising in the process of scientific knowledge. The transition from one competing paradigm to another is the transition from one non-commensurable thing to the other, and it cannot go step by step, promoted by logical and neutral experience [ 31 ].

A more detailed discussion of ontology requires the emphasis of the insights of various scientists. Hitchcock and Hughes [ 4 ] state that ontology is the theory of existence, interested in what exists, and is based on assertions of a particular paradigm about reality and truth. Other authors [ 28 ] simply identify it as a theory about the nature of reality. Hatch [ 32 ] notes that ontology is related to our assumptions about reality, i.e., whether reality is objective or subjective (existing in our minds). The most important questions that differentiated the research by far are threefold and depend on whether differences among assumptions are associated with different reality construction techniques (ontology) where, according to Denzin and Lincoln [ 33 ], the majority of questions asked are “what are the things in reality?” and “how do they really happen?”. Ontological questions are usually associated with real existence and operation matters [ 33 ], varying forms of knowledge about reality (epistemology), since epistemological questions help to ascertain the nature of relationship between the researcher and the respondent, and it is postulated that in order to make an assumption about the true reality, the researcher must follow the “objectivity and value distancing position” to find out what things are in reality, how they occur [ 33 ], and certain reality cognition techniques (methodology). With the help of methodological questions, the researcher mostly tries to figure out ways by which he can get to know his concerns [ 33 ].

Further analysis of the epistemology terminology presents different interpretations by various authors. For example, according to Brewerton and Millward [ 27 ], epistemology refers to the examination of what separates reasonable assurance from the opinion. According to Walker and Evers [ 26 ], generally speaking, epistemology is interested in how the researcher can receive knowledge about the phenomena of interest to him. Wiersma and Jurs [ 11 ] describe epistemology as a research which attempts to clarify the possibilities of knowledge, the boundaries, the origin, the structure, methods and justice, and the ways in which this knowledge can be obtained, confirmed, and adjusted. Hitchcock and Hughes [ 4 ], talking about the impact on epistemology, emphasize that it is very big for both data collection methods and research methodology. Hatch [ 32 ] highlights the idea that epistemology is concerned with knowledge—specific questions presented by the epistemology researchers are how people create knowledge, what the criteria enabling the distinction of good and bad knowledge are, and how should reality be represented or described? Epistemology is closely related to ontology, because the answers to these questions depend on the ontological assumptions about the nature of reality and, in turn, help to create them. Sale et al. [ 34 ], Cohen et al. [ 6 ], and Denzin and Lincoln [ 33 ] note that epistemological assumptions often arise from ontological assumptions. The former encourage a tendency to focus on methods and procedures in the course of research. Šaulauskas [ 35 ] points out that, in general, modern Western philosophy is a “pure” epistemology establishment, and its systemic dissemination vector is basically the reduction of the whole theoretical vision of gender in epistemological discussion.

It is said that in order to understand the reality there are three main types of paradigms to be employed, namely positivism, interpretivism, and realism. The conception of positivism is directly related to the idea of objectivism. Using this philosophical approach, the researchers express their views in order to assess the social world, and instead of subjectivity, they refer to objectivity [ 36 ]. Under this paradigm, researchers are interested in general information and large-scale social data collection rather than focusing on details of the research. In line with this position, the researchers' own personal attitudes are not relevant and do not affect the scientific research. Positivist philosophical approach is most closely associated with the observations and experiments, used for collection of numerical data [ 18 ]. In the sphere of management research, interpretivism can still be called social constructionism. With this philosophical point of view, the researchers take into account their views and values so that they could justify the problem posed in the research [ 18 ]. Kirtiklis [ 37 ] notes that while positivistic philosophy critical trend encourages strict separation of scientific problems solved by research from “speculative” philosophical problems and thus rejects the philosophy, the other trend, called interpretivism, on the contrary, states that philosophy cannot be strictly separated from social sciences, but it must be incorporated or blended into them. With the help of this philosophy, the scientists focus on the facts and figures corresponding to the research problem. This type of philosophical approach makes it possible to understand specific business situations. Using it, the researchers use small data samples and assess them very carefully in order to grasp the attitudes of larger population segments [ 38 ]. Realism, as a research philosophy, focuses on reality and beliefs existing in a certain environment. Two main branches of this philosophical approach are direct and critical realism [ 39 ]. Direct realism is what an individual feels, sees, hears, etc. On the other hand, in critical realism, the individuals discuss their experience in specific situations [ 40 ]. It is a matter of social constructivism, as individuals try to justify their own values and beliefs.

Analyzing other types of paradigms, in a sense, not qualified as the main, constructivism, symbolic interpretivism, pragmatism should be mentioned. The constructivism paradigm in some classifications of paradigms is called the “interpretative paradigm” [ 19 ]. There is no other definition in ontology, epistemology, and methodology; both approaches [ 41 ] have a common understanding of the complex world experience from the perspective of the individuals having this experience. The constructivists point out that various interpretations are possible because we have multiple realities. According to Onwuegbuzie [ 42 ], the reality for constructivists is a product of the human mind, which develops socially, and this changes the reality. The author states that there is dependence between what is known and who knows. So, for this reason, the researcher must become more familiar with what is being researched. Analyzing symbolic interpretivism through the prism of ontology, it can be said that it is the belief that we cannot know the external or objective existence apart from our subjective understanding of it; that, what exists, is what we agree on that it exists (emotion and intuition: experience forms behind the limits of the five senses). Analyzing symbolic interpretivism through epistemological aspect, all knowledge is related to the one who knows and can be understood only in terms of directly related individuals; the truth is socially created through multiple interpretations of knowledge objects created in this way, and therefore they change over time [ 32 ]. Pikturnaitė and Paužuolienė [ 43 ] note that scientists in most cases when analyzing organizational culture communication and dissemination examine the behavior, language, and other informal aspects that need to be observed, understood, and interpreted. Pragmatism, as a philosophy trend, considers practical thinking and action ways as the main, and the criterion of truth is considered for its practical application. However, as noted by Ružas [ 15 ] who analyzed Kuhn’s approach [ 16 ], since there are many ways of the world outlook and it is impossible to prove that one of them is more correct than the other, it should be stated only that in the science development process, they change each other.

The theories, according to which this research concentrates on the management culture development-level setting for the implementation of corporate social responsibility, are presented in Figure 2 , which distinguishes organizational culture levels and their interaction. Figure 3 defines corporate social responsibility stages that reflect the scientific research philosophy and the paradigm of this survey.

Figure 2.

Management culture in the context of organizational culture. Source: Adapted by the authors according to French and Bel [ 44 ], Schein [ 45 , 46 ], Ott [ 47 ], Bounds et al. [ 48 ], Krüger [ 49 ], Franklin and Pagan [ 50 ], etc.

Figure 3.

Corporate social responsibility stages. Source: Adapted by the authors according to Ruževičius [ 52 ].

In order to relatively “separate” management culture from organizational culture, one must look into their component elements of culture. For this reason, below organizational culture levels and components forming them are discussed in detail.

According to Schein [ 45 , 46 ], artifacts are described as the “easiest” observed level, that is, what we see, hear, and feel. The author presents a model that if you happen to go to organizations, you can immediately feel their uniqueness in the way “they perform the work,” that is, open-space office against closed-door offices; employees freely communicating with each other against the muted environment; and formal clothing against informal clothing. However, according to the author, “you should be careful by appealing to these attributes when deciding whether we like or do not like the organization, whether it is operating successfully or unsuccessfully, as at this observation stage it is not clear why organizations present themselves and interact with one another in such a particular way.” Schein [ 45 , 46 ] elaborates the supported values by considerations that “in order to better understand and decipher why the observed matters happen on the first level, people within the organization should be asked to explain that. For example, what happens when it is established that two similar organizations have very similar company values recorded in documents and published, principles, ethics and visions in which their employees believe and adhere to – i.e., described as their culture and reflecting their core values – for all that, the natural formation and working styles of the two organizations are very different, even if they have similar supported values?” According to the author, in order to see these “imbalances,” you need to realize that “unhindered behavior leads to a deeper level of thought and perception.” In shared mental models, for understanding this “deeper” level of culture, one should study the history of the organization, that is, what were the original values, beliefs, and assumptions of its founders and key leaders, which led to the success of the organization? Over time they have become common and are accepted as self-evident as soon as new members of the organization realized that the original values, beliefs, and assumptions of its founders led to organizational success, that is, through common cognition/assimilation of “correct” values, beliefs, and assumptions. Cultural levels distinguished by Schein [ 45 , 46 ] can be “transferred” to the organizational culture iceberg levels formed by French and Bel [ 44 ]. According to the authors [ 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 51 ], visible organizational structures consist of ceremonies, communication, heroes, habits, management methods, and so on. French and Bel [ 44 ] distinguish between these formal and informal elements of organizational culture: formal—aims, technology, structure, skills and abilities, financial resources; informal—approaches, values; feelings—anger, fear, frustration, etc.; and interaction group rates. Franklin and Pagan [ 50 ] detail the formal and informal structure of organizational culture factors, allocating them into tangible and intangible factors. Tangible factors (formal or officially authorized) are socialization and/or acculturation experience (if the organization takes care of timely and detailed orientation, it is more likely that the manager will use the process of formal discipline); written documents (if the manager is presented with the relevant policy and relevant procedures, it is more likely that the manager will use the formal discipline process); training (if the organization organizes training on discipline issues, it is more likely that the manager will use the formal discipline process); and structure of the organization (if the organization provides the power to the manager and if the manager has more control, it is more likely that the manager will use the formal discipline process). Intangible factors (informal or informally developed) [ 50 ] include problematic employees (if the employee does not have good professional skills or high position, it is more likely that the manager will use the formal discipline process); socialization/acculturation which manifests itself in the human resource management subdivision activities (if the manager’s solutions are supported and not devalued by organizational management, it is more likely that the manager will use the formal discipline process); the same social status people (if other managers focus on formal discipline process, it is more likely that the manager will use the formal discipline process); groups outside work (if systems of values, partly overlapping, cherished by groups outside, strengthen the organizational culture-supported expectations, it is more likely that the manager will use the formal discipline process). Krüger [ 49 ] formed the change management iceberg which deals with both visible and invisible barriers in the organization. With the help of this iceberg, there is an attempt to force the management to look into the hidden challenges that need to be overcome in order to implement changes in the organization. Iceberg model is relevant to the submitted research presented in this book in the way that implementation of corporate social responsibility is considered as a strong change in the activities of the organization. As stated by Krüger [ 49 ], the change management iceberg is best perceived by managers who understand that the most obvious change obstacles that need to be overcome, such as cost, quality, and time, are only the top of the iceberg, and more complicated obstacles, which have more influence, lie below. The foundation of change management theory is based on the fact that many managers tend to focus only on the obvious obstacles, instead of paying more attention to more complex issues, such as perceptions, beliefs, power, and politics. The theory also distinguishes implementation types (based on what change must take place) and the strategy that should be used. Another aspect of this theory is the people involved in the changes and to what extent they can promote changes or contradict them. So, Krüger [ 49 ] argues that the basis for change is directly related to the management of perceptions, beliefs, power, and politics. If managers understand how this is related to the creation of obstacles, according to the author, they will be able to better implement the changes that they want to perform in their organizations.

It is not enough to analyze only a single component of management culture without evaluation of the entirety. Management culture analysis and changes require a systematic approach, on the basis of which management culture system is presented in the research and its diagnostics is carried out. Having discussed the management culture through formal and informal organizational culture elements, it is appropriate to introduce imputed corporate social responsibility development stages. Figure 4 presents the corporate social responsibility implementation guidelines and corporate social responsibility application plan [ 52 ], together with the supplements of the authors of the book that extend implementation guidelines identified in the plan for the preparation aiming for corporate social responsibility establishment and management system evaluation, which are significant in further process of corporate social responsibility implementation.

Figure 4.

Research philosophy: the main aspects of the research. Source: Adapted by the authors according to Flowers [ 53 ].

Although the plan recommended by Ruževičius [ 52 ] is meant for the companies managed by the public sector, it is estimated that it was prepared in accordance with standards applied in companies operating in the free market, regardless of the origin of the capital. Control system evaluation, which is associated with the previously discussed management culture, is an important process chain because the volume of resource use, cost amounts, and timing as well as ultimate effect depend on its functionality. In addition, it is proposed to assess the possibility of the organization's retreat from corporate social responsibility (shareholders’ change, company restructuring, economic conditions and other relevant circumstances, changes influencing decisions), but it could be part of separate research that this study does not develop.

The research position . Guba and Lincoln [ 3 ] pointed out that the fragmentation of paradigm differences can occur only when there is a new paradigm which is more sophisticated than the existing ones. It is most likely, according to the authors, “if and when the proponents of different approaches meet to discuss the differences rather than argue about their opinion holiness.” All supporters’ dialogue with each other will provide an opportunity to move toward congenial (like-minded) relations. In this research, considering its versatility, one strictly defined position is not complied with. There is compliance with the principle of positivism when a scientist is an objective analyst, isolates himself from personal values, and works independently; in addition, thought and access freedom provided by pragmatism philosophical system is evaluated. Figure 4 summarizes the main elements of the study. The main aim of the research presented in this book is to define the management culture development level which creates an opportunity for organizations to pursue the implementation of corporate social responsibility. The analysis has shown that there is a lack of theoretical insights and empirical research, systematically linking management culture and corporate social responsibility aspects; still this work is not intended to cast a new challenge to already existing theories, but they are connected.

When preparing the research, it was based on academic literature and the insights of experts by using the original questionnaires made by the authors. The employees of two groups of companies, having different socio-demographic characteristics, occupying different positions in organizations are interviewed, and the data obtained are analyzed statistically and interpreted. In this study, the reliability of a specially developed research instrument is argued, and the main focus is on the factors of management culture that influences the implementation of corporate social responsibility at organizational level, as well as evaluating the corporate staff reactions and participation in processes. During the interviews with managers, the management culture as a formal expression of the organizational culture aiming at implementation of corporate social responsibility is revealed.

In this book, great attention is paid to statistical verification of instruments and model in order to be able to make recommendations to the organization management practitioners.

Philosophy of expert evaluation is based on the increasing demand of the versatility of the compiled instrument, and its content suitability for distinguished scales and subscales. The target of this research is to determine the surplus statements, not giving enough necessary information, as well as setting the statements where the content information not only verifies the honesty of the respondent, but also obviously reiterates. Philosophy of expert assessment is based on the research instrument content quality assurance, so that it would consist of statements, revealing in detail the research phenomena and enabling the achievement of the set goal of the research.

The philosophy of expert evaluation is based on the need to increase the versatility of the compiled instrument and its content suitability for derived scales and subscales. This research aims to determine the methodological and psychometric characteristics of the questionnaire with respect to a relatively small sample size, representing the situation of one organization. After eliminating the documented shortcomings during the exploratory research, the aim is to prepare an instrument featuring high methodological and psychometric characteristics, suitable for further research analyzing the cases of different sample sizes and different organizations.

The basic (quantitative and qualitative) research philosophy is based on perception of research data significance, importance for the public, and the principle of objectivity. In order to minimize subjectivity and guarantee reliability and the possibility of further discussions, quantitative research findings are based on conclusion (statistical generalization) and qualitative contextual understanding (analytic generalization). Both research results are presented in detail, openly showing the research organization and implementation process.

- 1. Holden MT, Lynch P. Choosing the appropriate methodology: Understanding research philosophy. The Marketing Review. 2004; 4 (4):397-409. DOI: 10.1362/1469347042772428

- 2. Crossan F. Research philosophy: Towards an understanding. Nurse Researcher. 2003; 11 (1):46-55. DOI: 10.7748/nr2003.10.11.1.46.c5914

- 3. Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. p. 105-117

- 4. Hitchcock G, Hughes D. Research and the Teacher. London: Routledge; 1989