Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Academic writing

- How to write a lab report

How To Write A Lab Report | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on May 20, 2021 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A lab report conveys the aim, methods, results, and conclusions of a scientific experiment. The main purpose of a lab report is to demonstrate your understanding of the scientific method by performing and evaluating a hands-on lab experiment. This type of assignment is usually shorter than a research paper .

Lab reports are commonly used in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. This article focuses on how to structure and write a lab report.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Structuring a lab report, introduction, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about lab reports.

The sections of a lab report can vary between scientific fields and course requirements, but they usually contain the purpose, methods, and findings of a lab experiment .

Each section of a lab report has its own purpose.

- Title: expresses the topic of your study

- Abstract : summarizes your research aims, methods, results, and conclusions

- Introduction: establishes the context needed to understand the topic

- Method: describes the materials and procedures used in the experiment

- Results: reports all descriptive and inferential statistical analyses

- Discussion: interprets and evaluates results and identifies limitations

- Conclusion: sums up the main findings of your experiment

- References: list of all sources cited using a specific style (e.g. APA )

- Appendices : contains lengthy materials, procedures, tables or figures

Although most lab reports contain these sections, some sections can be omitted or combined with others. For example, some lab reports contain a brief section on research aims instead of an introduction, and a separate conclusion is not always required.

If you’re not sure, it’s best to check your lab report requirements with your instructor.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Your title provides the first impression of your lab report – effective titles communicate the topic and/or the findings of your study in specific terms.

Create a title that directly conveys the main focus or purpose of your study. It doesn’t need to be creative or thought-provoking, but it should be informative.

- The effects of varying nitrogen levels on tomato plant height.

- Testing the universality of the McGurk effect.

- Comparing the viscosity of common liquids found in kitchens.

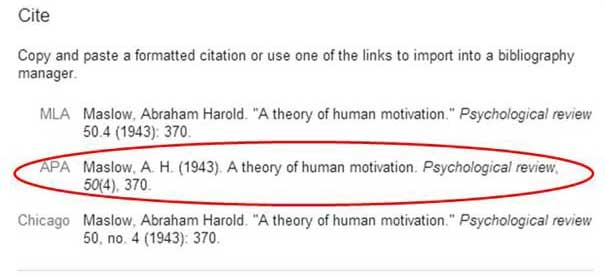

An abstract condenses a lab report into a brief overview of about 150–300 words. It should provide readers with a compact version of the research aims, the methods and materials used, the main results, and the final conclusion.

Think of it as a way of giving readers a preview of your full lab report. Write the abstract last, in the past tense, after you’ve drafted all the other sections of your report, so you’ll be able to succinctly summarize each section.

To write a lab report abstract, use these guiding questions:

- What is the wider context of your study?

- What research question were you trying to answer?

- How did you perform the experiment?

- What did your results show?

- How did you interpret your results?

- What is the importance of your findings?

Nitrogen is a necessary nutrient for high quality plants. Tomatoes, one of the most consumed fruits worldwide, rely on nitrogen for healthy leaves and stems to grow fruit. This experiment tested whether nitrogen levels affected tomato plant height in a controlled setting. It was expected that higher levels of nitrogen fertilizer would yield taller tomato plants.

Levels of nitrogen fertilizer were varied between three groups of tomato plants. The control group did not receive any nitrogen fertilizer, while one experimental group received low levels of nitrogen fertilizer, and a second experimental group received high levels of nitrogen fertilizer. All plants were grown from seeds, and heights were measured 50 days into the experiment.

The effects of nitrogen levels on plant height were tested between groups using an ANOVA. The plants with the highest level of nitrogen fertilizer were the tallest, while the plants with low levels of nitrogen exceeded the control group plants in height. In line with expectations and previous findings, the effects of nitrogen levels on plant height were statistically significant. This study strengthens the importance of nitrogen for tomato plants.

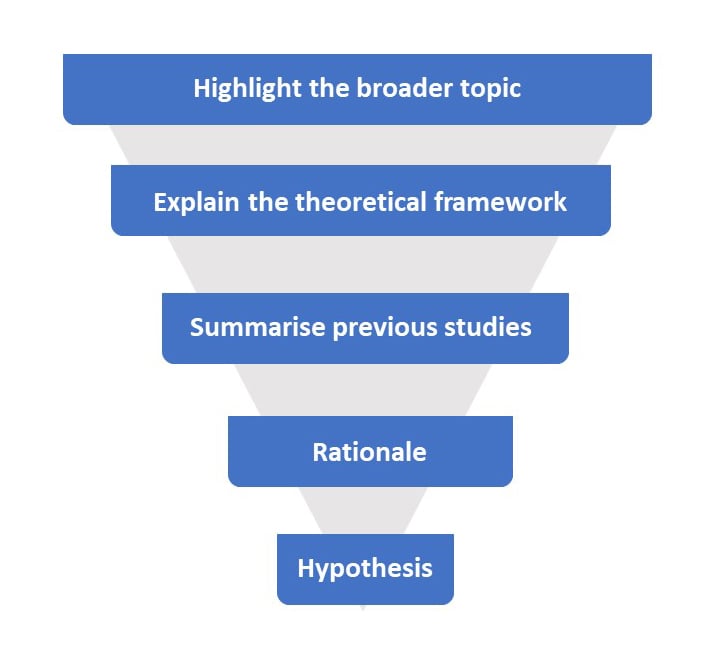

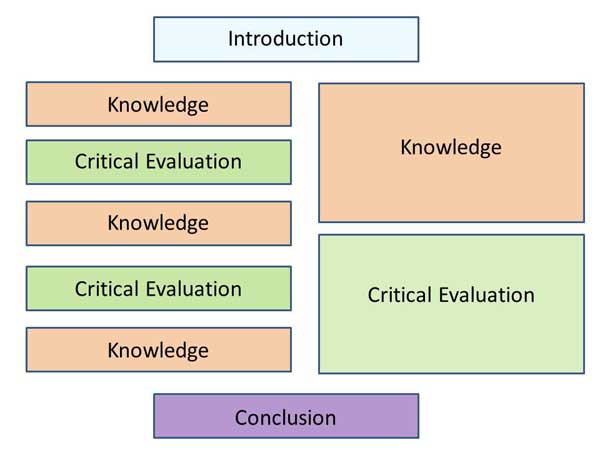

Your lab report introduction should set the scene for your experiment. One way to write your introduction is with a funnel (an inverted triangle) structure:

- Start with the broad, general research topic

- Narrow your topic down your specific study focus

- End with a clear research question

Begin by providing background information on your research topic and explaining why it’s important in a broad real-world or theoretical context. Describe relevant previous research on your topic and note how your study may confirm it or expand it, or fill a gap in the research field.

This lab experiment builds on previous research from Haque, Paul, and Sarker (2011), who demonstrated that tomato plant yield increased at higher levels of nitrogen. However, the present research focuses on plant height as a growth indicator and uses a lab-controlled setting instead.

Next, go into detail on the theoretical basis for your study and describe any directly relevant laws or equations that you’ll be using. State your main research aims and expectations by outlining your hypotheses .

Based on the importance of nitrogen for tomato plants, the primary hypothesis was that the plants with the high levels of nitrogen would grow the tallest. The secondary hypothesis was that plants with low levels of nitrogen would grow taller than plants with no nitrogen.

Your introduction doesn’t need to be long, but you may need to organize it into a few paragraphs or with subheadings such as “Research Context” or “Research Aims.”

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

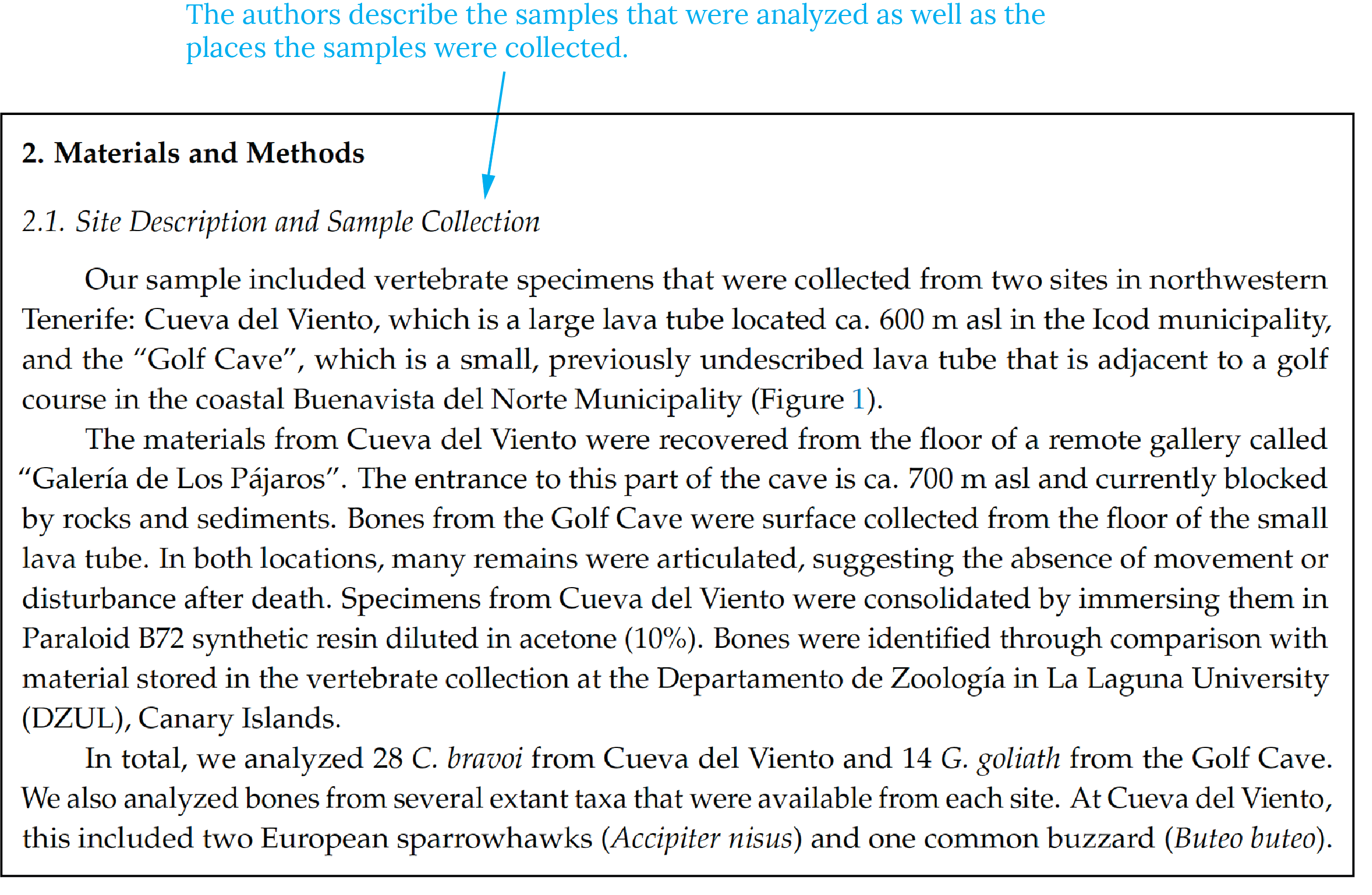

A lab report Method section details the steps you took to gather and analyze data. Give enough detail so that others can follow or evaluate your procedures. Write this section in the past tense. If you need to include any long lists of procedural steps or materials, place them in the Appendices section but refer to them in the text here.

You should describe your experimental design, your subjects, materials, and specific procedures used for data collection and analysis.

Experimental design

Briefly note whether your experiment is a within-subjects or between-subjects design, and describe how your sample units were assigned to conditions if relevant.

A between-subjects design with three groups of tomato plants was used. The control group did not receive any nitrogen fertilizer. The first experimental group received a low level of nitrogen fertilizer, while the second experimental group received a high level of nitrogen fertilizer.

Describe human subjects in terms of demographic characteristics, and animal or plant subjects in terms of genetic background. Note the total number of subjects as well as the number of subjects per condition or per group. You should also state how you recruited subjects for your study.

List the equipment or materials you used to gather data and state the model names for any specialized equipment.

List of materials

35 Tomato seeds

15 plant pots (15 cm tall)

Light lamps (50,000 lux)

Nitrogen fertilizer

Measuring tape

Describe your experimental settings and conditions in detail. You can provide labelled diagrams or images of the exact set-up necessary for experimental equipment. State how extraneous variables were controlled through restriction or by fixing them at a certain level (e.g., keeping the lab at room temperature).

Light levels were fixed throughout the experiment, and the plants were exposed to 12 hours of light a day. Temperature was restricted to between 23 and 25℃. The pH and carbon levels of the soil were also held constant throughout the experiment as these variables could influence plant height. The plants were grown in rooms free of insects or other pests, and they were spaced out adequately.

Your experimental procedure should describe the exact steps you took to gather data in chronological order. You’ll need to provide enough information so that someone else can replicate your procedure, but you should also be concise. Place detailed information in the appendices where appropriate.

In a lab experiment, you’ll often closely follow a lab manual to gather data. Some instructors will allow you to simply reference the manual and state whether you changed any steps based on practical considerations. Other instructors may want you to rewrite the lab manual procedures as complete sentences in coherent paragraphs, while noting any changes to the steps that you applied in practice.

If you’re performing extensive data analysis, be sure to state your planned analysis methods as well. This includes the types of tests you’ll perform and any programs or software you’ll use for calculations (if relevant).

First, tomato seeds were sown in wooden flats containing soil about 2 cm below the surface. Each seed was kept 3-5 cm apart. The flats were covered to keep the soil moist until germination. The seedlings were removed and transplanted to pots 8 days later, with a maximum of 2 plants to a pot. Each pot was watered once a day to keep the soil moist.

The nitrogen fertilizer treatment was applied to the plant pots 12 days after transplantation. The control group received no treatment, while the first experimental group received a low concentration, and the second experimental group received a high concentration. There were 5 pots in each group, and each plant pot was labelled to indicate the group the plants belonged to.

50 days after the start of the experiment, plant height was measured for all plants. A measuring tape was used to record the length of the plant from ground level to the top of the tallest leaf.

In your results section, you should report the results of any statistical analysis procedures that you undertook. You should clearly state how the results of statistical tests support or refute your initial hypotheses.

The main results to report include:

- any descriptive statistics

- statistical test results

- the significance of the test results

- estimates of standard error or confidence intervals

The mean heights of the plants in the control group, low nitrogen group, and high nitrogen groups were 20.3, 25.1, and 29.6 cm respectively. A one-way ANOVA was applied to calculate the effect of nitrogen fertilizer level on plant height. The results demonstrated statistically significant ( p = .03) height differences between groups.

Next, post-hoc tests were performed to assess the primary and secondary hypotheses. In support of the primary hypothesis, the high nitrogen group plants were significantly taller than the low nitrogen group and the control group plants. Similarly, the results supported the secondary hypothesis: the low nitrogen plants were taller than the control group plants.

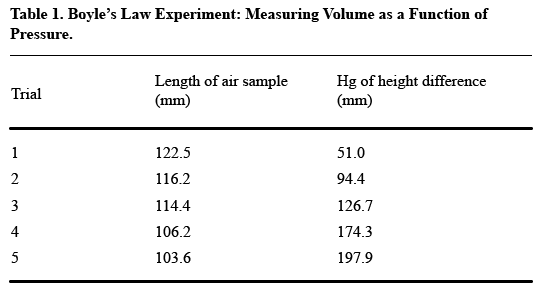

These results can be reported in the text or in tables and figures. Use text for highlighting a few key results, but present large sets of numbers in tables, or show relationships between variables with graphs.

You should also include sample calculations in the Results section for complex experiments. For each sample calculation, provide a brief description of what it does and use clear symbols. Present your raw data in the Appendices section and refer to it to highlight any outliers or trends.

The Discussion section will help demonstrate your understanding of the experimental process and your critical thinking skills.

In this section, you can:

- Interpret your results

- Compare your findings with your expectations

- Identify any sources of experimental error

- Explain any unexpected results

- Suggest possible improvements for further studies

Interpreting your results involves clarifying how your results help you answer your main research question. Report whether your results support your hypotheses.

- Did you measure what you sought out to measure?

- Were your analysis procedures appropriate for this type of data?

Compare your findings with other research and explain any key differences in findings.

- Are your results in line with those from previous studies or your classmates’ results? Why or why not?

An effective Discussion section will also highlight the strengths and limitations of a study.

- Did you have high internal validity or reliability?

- How did you establish these aspects of your study?

When describing limitations, use specific examples. For example, if random error contributed substantially to the measurements in your study, state the particular sources of error (e.g., imprecise apparatus) and explain ways to improve them.

The results support the hypothesis that nitrogen levels affect plant height, with increasing levels producing taller plants. These statistically significant results are taken together with previous research to support the importance of nitrogen as a nutrient for tomato plant growth.

However, unlike previous studies, this study focused on plant height as an indicator of plant growth in the present experiment. Importantly, plant height may not always reflect plant health or fruit yield, so measuring other indicators would have strengthened the study findings.

Another limitation of the study is the plant height measurement technique, as the measuring tape was not suitable for plants with extreme curvature. Future studies may focus on measuring plant height in different ways.

The main strengths of this study were the controls for extraneous variables, such as pH and carbon levels of the soil. All other factors that could affect plant height were tightly controlled to isolate the effects of nitrogen levels, resulting in high internal validity for this study.

Your conclusion should be the final section of your lab report. Here, you’ll summarize the findings of your experiment, with a brief overview of the strengths and limitations, and implications of your study for further research.

Some lab reports may omit a Conclusion section because it overlaps with the Discussion section, but you should check with your instructor before doing so.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

A lab report conveys the aim, methods, results, and conclusions of a scientific experiment . Lab reports are commonly assigned in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields.

The purpose of a lab report is to demonstrate your understanding of the scientific method with a hands-on lab experiment. Course instructors will often provide you with an experimental design and procedure. Your task is to write up how you actually performed the experiment and evaluate the outcome.

In contrast, a research paper requires you to independently develop an original argument. It involves more in-depth research and interpretation of sources and data.

A lab report is usually shorter than a research paper.

The sections of a lab report can vary between scientific fields and course requirements, but it usually contains the following:

- Abstract: summarizes your research aims, methods, results, and conclusions

- References: list of all sources cited using a specific style (e.g. APA)

- Appendices: contains lengthy materials, procedures, tables or figures

The results chapter or section simply and objectively reports what you found, without speculating on why you found these results. The discussion interprets the meaning of the results, puts them in context, and explains why they matter.

In qualitative research , results and discussion are sometimes combined. But in quantitative research , it’s considered important to separate the objective results from your interpretation of them.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, July 23). How To Write A Lab Report | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-writing/lab-report/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, how to write an apa methods section, how to write an apa results section, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Peterborough

Writing Lab Reports: Methods

Keys to the methods section.

Purpose : How did you conduct this study? Relative size : 10-15% of total Scope : Narrow: the middle of the hourglass Verb Tense : Always use the past tense when summarizing the methods of the experiment.

The methods section sets out important details.

The purpose of this section is to provide sufficient detail of your methodology so that a reader could repeat your study and reproduce your results. Though the methods section is the most straightforward part of the lab report, you may find it difficult to balance enough information with too much extraneous detail. To test yourself, ask, “Would someone need to know this detail to reproduce this study?”

Avoid writing your methods as a step-by-step procedure; rather, present a concise summary of what you did. Consider the following examples:

Example 1: “First, each group chose a turtle. A member of each group then measured the carapace length, while another recorded the measurement in the lab book. A different group member then recorded the turtle’s weight.”

Example 2: “Students determined carapace length (cm) and weight (g) for all individuals.”

The first example provides unnecessary information (the reader need not know that each turtle was measured by a different group, nor which group member took the measurements) and is tedious to read. The second is clear and concise, and it also provides the units of measurements. Note that it is not necessary to mention that data were recorded – we assume that if you took the trouble to take a measurement, you also wrote it down.

The methods section should contain information specific to your study only. This means that you generally should not refer to other research and, therefore, should not include citations. Exceptions arise when using another author’s method, such as when following the procedure from your lab manual, or when using maps or diagrams from other sources.

Methods Section Details

Study area : Describe your study area. Geographic location, size, boundaries, topography, and habitat type (forest or meadow composition, type of water bodies, for example) may be relevant.

Organism : If studying a particular organism, provide details of gender, age, and other relevant information to your study.

Materials : Within the prose of your procedure text, integrate materials that you used. Include model numbers of specialized lab equipment, concentrations of chemical solutions, and other such details.

Procedure : What you did – write in paragraph format (no point form or numbered steps). Include an explanation of your experimental design, sample size, replicates, measurement techniques, etc.

Data Analysis : What statistical tests you used (including tests of normality), significance level set (α=?), and any data manipulation required. Include specific calculations, if appropriate.

Figures : Include diagrams of study area, equipment, or procedures, where appropriate. Number and title appropriately and refer to the figure within the text.

A good methods section should...

- Provide enough detail to allow an accurate reproduction of the study

- Be written in a logically flowing paragraph format

- Provide details on the study site, organism, materials, procedure, and statistical analysis

- Should reference the lab manual, if appropriate

A good methods section should NOT...

- Be a recipe-book-style instruction guide

- Provide a list of materials

- Use bullet points

- Cite other studies for comparison

Back to Writing Lab Reports

Next to Writing Results

Complete Guide to Writing a Lab Report (With Example)

Students tend to approach writing lab reports with confusion and dread. Whether in high school science classes or undergraduate laboratories, experiments are always fun and games until the times comes to submit a lab report. What if we didn’t need to spend hours agonizing over this piece of scientific writing? Our lives would be so much easier if we were told what information to include, what to do with all their data and how to use references. Well, here’s a guide to all the core components in a well-written lab report, complete with an example.

Things to Include in a Laboratory Report

The laboratory report is simply a way to show that you understand the link between theory and practice while communicating through clear and concise writing. As with all forms of writing, it’s not the report’s length that matters, but the quality of the information conveyed within. This article outlines the important bits that go into writing a lab report (title, abstract, introduction, method, results, discussion, conclusion, reference). At the end is an example report of reducing sugar analysis with Benedict’s reagent.

The report’s title should be short but descriptive, indicating the qualitative or quantitative nature of the practical along with the primary goal or area of focus.

Following this should be the abstract, 2-3 sentences summarizing the practical. The abstract shows the reader the main results of the practical and helps them decide quickly whether the rest of the report is relevant to their use. Remember that the whole report should be written in a passive voice .

Introduction

The introduction provides context to the experiment in a couple of paragraphs and relevant diagrams. While a short preamble outlining the history of the techniques or materials used in the practical is appropriate, the bulk of the introduction should outline the experiment’s goals, creating a logical flow to the next section.

Some reports require you to write down the materials used, which can be combined with this section. The example below does not include a list of materials used. If unclear, it is best to check with your teacher or demonstrator before writing your lab report from scratch.

Step-by-step methods are usually provided in high school and undergraduate laboratory practicals, so it’s just a matter of paraphrasing them. This is usually the section that teachers and demonstrators care the least about. Any unexpected changes to the experimental setup or techniques can also be documented here.

The results section should include the raw data that has been collected in the experiment as well as calculations that are performed. It is usually appropriate to include diagrams; depending on the experiment, these can range from scatter plots to chromatograms.

The discussion is the most critical part of the lab report as it is a chance for you to show that you have a deep understanding of the practical and the theory behind it. Teachers and lecturers tend to give this section the most weightage when marking the report. It would help if you used the discussion section to address several points:

- Explain the results gathered. Is there a particular trend? Do the results support the theory behind the experiment?

- Highlight any unexpected results or outlying data points. What are possible sources of error?

- Address the weaknesses of the experiment. Refer to the materials and methods used to identify improvements that would yield better results (more accurate equipment, better experimental technique, etc.)

Finally, a short paragraph to conclude the laboratory report. It should summarize the findings and provide an objective review of the experiment.

If any external sources were used in writing the lab report, they should go here. Referencing is critical in scientific writing; it’s like giving a shout out (known as a citation) to the original provider of the information. It is good practice to have at least one source referenced, either from researching the context behind the experiment, best practices for the method used or similar industry standards.

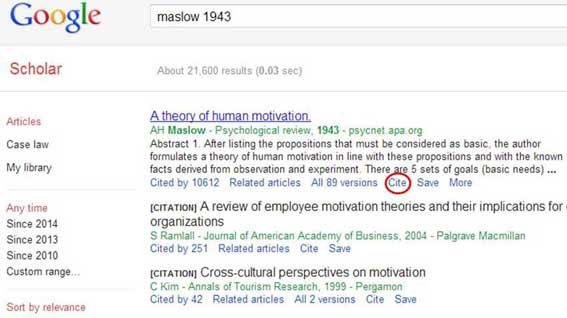

Google Scholar is a good resource for quickly gathering references of a specific style . Searching for the article in the search bar and clicking on the ‘cite’ button opens a pop-up that allows you to copy and paste from several common referencing styles.

Example: Writing a Lab Report

Title : Semi-Quantitative Analysis of Food Products using Benedict’s Reagent

Abstract : Food products (milk, chicken, bread, orange juice) were solubilized and tested for reducing sugars using Benedict’s reagent. Milk contained the highest level of reducing sugars at ~2%, while chicken contained almost no reducing sugars.

Introduction : Sugar detection has been of interest for over 100 years, with the first test for glucose using copper sulfate developed by German chemist Karl Trommer in 1841. It was used to test the urine of diabetics, where sugar was present in high amounts. However, it wasn’t until 1907 when the method was perfected by Stanley Benedict, using sodium citrate and sodium carbonate to stabilize the copper sulfate in solution. Benedict’s reagent is a bright blue because of the copper sulfate, turning green and then red as the concentration of reducing sugars increases.

Benedict’s reagent was used in this experiment to compare the amount of reducing sugars between four food items: milk, chicken solution, bread and orange juice. Following this, standardized glucose solutions (0.0%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%) were tested with Benedict’s reagent to determine the color produced at those sugar levels, allowing us to perform a semi-quantitative analysis of the food items.

Method : Benedict’s reagent was prepared by mixing 1.73 g of copper (II) sulfate pentahydrate, 17.30 g of sodium citrate pentahydrate and 10.00 g of sodium carbonate anhydrous. The mixture was dissolved with stirring and made up to 100 ml using distilled water before filtration using filter paper and a funnel to remove any impurities.

4 ml of milk, chicken solution and orange juice (commercially available) were measured in test tubes, along with 4 ml of bread solution. The bread solution was prepared using 4 g of dried bread ground with mortar and pestle before diluting with distilled water up to 4 ml. Then, 4 ml of Benedict’s reagent was added to each test tube and placed in a boiling water bath for 5 minutes, then each test tube was observed.

Next, glucose solutions were prepared by dissolving 0.5 g, 1.0 g, 1.5 g and 2.0 g of glucose in 100 ml of distilled water to produce 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5% and 2.0% solutions, respectively. 4 ml of each solution was added to 4 ml of Benedict’s reagent in a test tube and placed in a boiling water bath for 5 minutes, then each test tube was observed.

Results : Food Solutions (4 ml) with Benedict’s Reagent (4 ml)

| Food Solutions | Color Observed |

|---|---|

| Milk | Red |

| Chicken Solution | Blue |

| Bread | Green |

| Orange Juice | Orange |

Glucose Solutions (4 ml) with Benedict’s Reagent (4 ml)

| Glucose Solutions | Color Observed |

|---|---|

| 0.0% (Control) | Blue |

| 0.5% | Green |

| 1.0% | Dark Green |

| 1.5% | Orange |

| 2.0% | Red |

Semi-Quantitative Analysis from Data

| Food Solutions | Sugar Levels |

|---|---|

| Milk | 2.0% |

| Chicken Solution | 0.0% |

| Bread | 0.5% |

| Orange Juice | 1.5% |

Discussion : From the analysis of food solutions along with the glucose solutions of known concentrations, the semi-quantitative analysis of sugar levels in different food products was performed. Milk had the highest sugar content of 2%, with orange juice at 1.5%, bread at 0.5% and chicken with 0% sugar. These values were approximated; the standard solutions were not the exact color of the food solutions, but the closest color match was chosen.

One point of contention was using the orange juice solution, which conferred color to the starting solution, rendering it green before the reaction started. This could have led to the final color (and hence, sugar quantity) being inaccurate. Also, since comparing colors using eyesight alone is inaccurate, the experiment could be improved with a colorimeter that can accurately determine the exact wavelength of light absorbed by the solution.

Another downside of Benedict’s reagent is its inability to react with non-reducing sugars. Reducing sugars encompass all sugar types that can be oxidized from aldehydes or ketones into carboxylic acids. This means that all monosaccharides (glucose, fructose, etc.) are reducing sugars, while only select polysaccharides are. Disaccharides like sucrose and trehalose cannot be oxidized, hence are non-reducing and will not react with Benedict’s reagent. Furthermore, Benedict’s reagent cannot distinguish between different types of reducing sugars.

Conclusion : Using Benedict’s reagent, different food products were analyzed semi-quantitatively for their levels of reducing sugars. Milk contained around 2% sugar, while the chicken solution had no sugar. Overall, the experiment was a success, although the accuracy of the results could have been improved with the use of quantitative equipment and methods.

Reference :

- Raza, S. I., Raza, S. A., Kazmi, M., Khan, S., & Hussain, I. (2021). 100 Years of Glucose Monitoring in Diabetes Management. Journal of Diabetes Mellitus , 11 (5), 221-233.

- Benedict, Stanley R (1909). A Reagent for the Detection of Reducing Sugars. Journal of Biological Chemistry , 5 , 485-487.

Using this guide and example, writing a lab report should be a hassle-free, perhaps even enjoyable process!

About the Author

Sean is a consultant for clients in the pharmaceutical industry and is an associate lecturer at La Trobe University, where unfortunate undergrads are subject to his ramblings on chemistry and pharmacology.

You Might Also Like…

The stress response: friend or foe, climate change: one planet, one chance.

If our content has been helpful to you, please consider supporting our independent science publishing efforts: for just $1 a month.

© 2023 FTLOScience • All Rights Reserved

Lab Report Format: Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

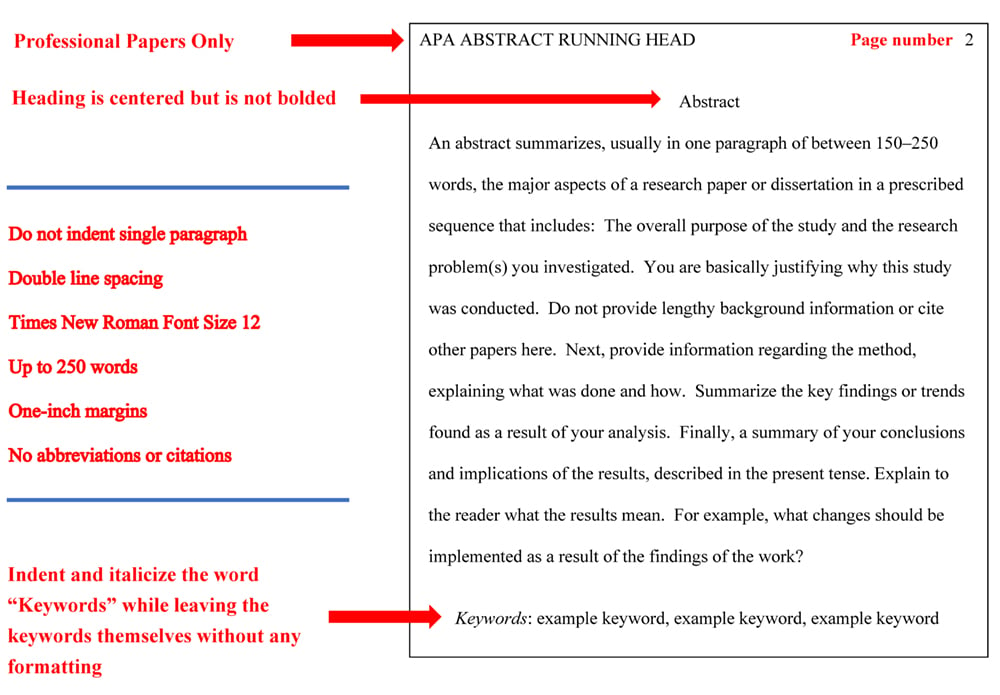

In psychology, a lab report outlines a study’s objectives, methods, results, discussion, and conclusions, ensuring clarity and adherence to APA (or relevant) formatting guidelines.

A typical lab report would include the following sections: title, abstract, introduction, method, results, and discussion.

The title page, abstract, references, and appendices are started on separate pages (subsections from the main body of the report are not). Use double-line spacing of text, font size 12, and include page numbers.

The report should have a thread of arguments linking the prediction in the introduction to the content of the discussion.

This must indicate what the study is about. It must include the variables under investigation. It should not be written as a question.

Title pages should be formatted in APA style .

The abstract provides a concise and comprehensive summary of a research report. Your style should be brief but not use note form. Look at examples in journal articles . It should aim to explain very briefly (about 150 words) the following:

- Start with a one/two sentence summary, providing the aim and rationale for the study.

- Describe participants and setting: who, when, where, how many, and what groups?

- Describe the method: what design, what experimental treatment, what questionnaires, surveys, or tests were used.

- Describe the major findings, including a mention of the statistics used and the significance levels, or simply one sentence summing up the outcome.

- The final sentence(s) outline the study’s “contribution to knowledge” within the literature. What does it all mean? Mention the implications of your findings if appropriate.

The abstract comes at the beginning of your report but is written at the end (as it summarises information from all the other sections of the report).

Introduction

The purpose of the introduction is to explain where your hypothesis comes from (i.e., it should provide a rationale for your research study).

Ideally, the introduction should have a funnel structure: Start broad and then become more specific. The aims should not appear out of thin air; the preceding review of psychological literature should lead logically into the aims and hypotheses.

- Start with general theory, briefly introducing the topic. Define the important key terms.

- Explain the theoretical framework.

- Summarise and synthesize previous studies – What was the purpose? Who were the participants? What did they do? What did they find? What do these results mean? How do the results relate to the theoretical framework?

- Rationale: How does the current study address a gap in the literature? Perhaps it overcomes a limitation of previous research.

- Aims and hypothesis. Write a paragraph explaining what you plan to investigate and make a clear and concise prediction regarding the results you expect to find.

There should be a logical progression of ideas that aids the flow of the report. This means the studies outlined should lead logically to your aims and hypotheses.

Do be concise and selective, and avoid the temptation to include anything in case it is relevant (i.e., don’t write a shopping list of studies).

USE THE FOLLOWING SUBHEADINGS:

Participants

- How many participants were recruited?

- Say how you obtained your sample (e.g., opportunity sample).

- Give relevant demographic details (e.g., gender, ethnicity, age range, mean age, and standard deviation).

- State the experimental design .

- What were the independent and dependent variables ? Make sure the independent variable is labeled and name the different conditions/levels.

- For example, if gender is the independent variable label, then male and female are the levels/conditions/groups.

- How were the IV and DV operationalized?

- Identify any controls used, e.g., counterbalancing and control of extraneous variables.

- List all the materials and measures (e.g., what was the title of the questionnaire? Was it adapted from a study?).

- You do not need to include wholesale replication of materials – instead, include a ‘sensible’ (illustrate) level of detail. For example, give examples of questionnaire items.

- Include the reliability (e.g., alpha values) for the measure(s).

- Describe the precise procedure you followed when conducting your research, i.e., exactly what you did.

- Describe in sufficient detail to allow for replication of findings.

- Be concise in your description and omit extraneous/trivial details, e.g., you don’t need to include details regarding instructions, debrief, record sheets, etc.

- Assume the reader has no knowledge of what you did and ensure that he/she can replicate (i.e., copy) your study exactly by what you write in this section.

- Write in the past tense.

- Don’t justify or explain in the Method (e.g., why you chose a particular sampling method); just report what you did.

- Only give enough detail for someone to replicate the experiment – be concise in your writing.

- The results section of a paper usually presents descriptive statistics followed by inferential statistics.

- Report the means, standard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each IV level. If you have four to 20 numbers to present, a well-presented table is best, APA style.

- Name the statistical test being used.

- Report appropriate statistics (e.g., t-scores, p values ).

- Report the magnitude (e.g., are the results significant or not?) as well as the direction of the results (e.g., which group performed better?).

- It is optional to report the effect size (this does not appear on the SPSS output).

- Avoid interpreting the results (save this for the discussion).

- Make sure the results are presented clearly and concisely. A table can be used to display descriptive statistics if this makes the data easier to understand.

- DO NOT include any raw data.

- Follow APA style.

Use APA Style

- Numbers reported to 2 d.p. (incl. 0 before the decimal if 1.00, e.g., “0.51”). The exceptions to this rule: Numbers which can never exceed 1.0 (e.g., p -values, r-values): report to 3 d.p. and do not include 0 before the decimal place, e.g., “.001”.

- Percentages and degrees of freedom: report as whole numbers.

- Statistical symbols that are not Greek letters should be italicized (e.g., M , SD , t , X 2 , F , p , d ).

- Include spaces on either side of the equals sign.

- When reporting 95%, CIs (confidence intervals), upper and lower limits are given inside square brackets, e.g., “95% CI [73.37, 102.23]”

- Outline your findings in plain English (avoid statistical jargon) and relate your results to your hypothesis, e.g., is it supported or rejected?

- Compare your results to background materials from the introduction section. Are your results similar or different? Discuss why/why not.

- How confident can we be in the results? Acknowledge limitations, but only if they can explain the result obtained. If the study has found a reliable effect, be very careful suggesting limitations as you are doubting your results. Unless you can think of any c onfounding variable that can explain the results instead of the IV, it would be advisable to leave the section out.

- Suggest constructive ways to improve your study if appropriate.

- What are the implications of your findings? Say what your findings mean for how people behave in the real world.

- Suggest an idea for further research triggered by your study, something in the same area but not simply an improved version of yours. Perhaps you could base this on a limitation of your study.

- Concluding paragraph – Finish with a statement of your findings and the key points of the discussion (e.g., interpretation and implications) in no more than 3 or 4 sentences.

Reference Page

The reference section lists all the sources cited in the essay (alphabetically). It is not a bibliography (a list of the books you used).

In simple terms, every time you refer to a psychologist’s name (and date), you need to reference the original source of information.

If you have been using textbooks this is easy as the references are usually at the back of the book and you can just copy them down. If you have been using websites then you may have a problem as they might not provide a reference section for you to copy.

References need to be set out APA style :

Author, A. A. (year). Title of work . Location: Publisher.

Journal Articles

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (year). Article title. Journal Title, volume number (issue number), page numbers

A simple way to write your reference section is to use Google scholar . Just type the name and date of the psychologist in the search box and click on the “cite” link.

Next, copy and paste the APA reference into the reference section of your essay.

Once again, remember that references need to be in alphabetical order according to surname.

Psychology Lab Report Example

Quantitative paper template.

Quantitative professional paper template: Adapted from “Fake News, Fast and Slow: Deliberation Reduces Belief in False (but Not True) News Headlines,” by B. Bago, D. G. Rand, and G. Pennycook, 2020, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General , 149 (8), pp. 1608–1613 ( https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000729 ). Copyright 2020 by the American Psychological Association.

Qualitative paper template

Qualitative professional paper template: Adapted from “‘My Smartphone Is an Extension of Myself’: A Holistic Qualitative Exploration of the Impact of Using a Smartphone,” by L. J. Harkin and D. Kuss, 2020, Psychology of Popular Media , 10 (1), pp. 28–38 ( https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000278 ). Copyright 2020 by the American Psychological Association.

Related Articles

Student Resources

How To Cite A YouTube Video In APA Style – With Examples

How to Write an Abstract APA Format

APA References Page Formatting and Example

APA Title Page (Cover Page) Format, Example, & Templates

How do I Cite a Source with Multiple Authors in APA Style?

How to Write a Psychology Essay

Are you seeking one-on-one college counseling and/or essay support? Limited spots are now available. Click here to learn more.

How to Write a Lab Report – with Example/Template

April 11, 2024

Perhaps you’re in the midst of your challenging AP chemistry class in high school, or perhaps college you’re enrolled in biology , chemistry , or physics at university. At some point, you will likely be asked to write a lab report. Sometimes, your teacher or professor will give you specific instructions for how to format and write your lab report, and if so, use that. In case you’re left to your own devices, here are some guidelines you might find useful. Continue reading for the main elements of a lab report, followed by a detailed description of the more writing-heavy parts (with a lab report example/lab report template). Lastly, we’ve included an outline that can help get you started.

What is a lab report?

A lab report is an overview of your experiment. Essentially, it explains what you did in the experiment and how it went. Most lab reports end up being 5-10 pages long (graphs or other images included), though the length depends on the experiment. Here are some brief explanations of the essential parts of a lab report:

Title : The title says, in the most straightforward way possible, what you did in the experiment. Often, the title looks something like, “Effects of ____ on _____.” Sometimes, a lab report also requires a title page, which includes your name (and the names of any lab partners), your instructor’s name, and the date of the experiment.

Abstract : This is a short description of key findings of the experiment so that a potential reader could get an idea of the experiment before even beginning.

Introduction : This is comprised of one or several paragraphs summarizing the purpose of the lab. The introduction usually includes the hypothesis, as well as some background information.

Lab Report Example (Continued)

Materials : Perhaps the simplest part of your lab report, this is where you list everything needed for the completion of your experiment.

Methods : This is where you describe your experimental procedure. The section provides necessary information for someone who would want to replicate your study. In paragraph form, write out your methods in chronological order, though avoid excessive detail.

Data : Here, you should document what happened in the experiment, step-by-step. This section often includes graphs and tables with data, as well as descriptions of patterns and trends. You do not need to interpret all of the data in this section, but you can describe trends or patterns, and state which findings are interesting and/or significant.

Discussion of results : This is the overview of your findings from the experiment, with an explanation of how they pertain to your hypothesis, as well as any anomalies or errors.

Conclusion : Your conclusion will sum up the results of your experiment, as well as their significance. Sometimes, conclusions also suggest future studies.

Sources : Often in APA style , you should list all texts that helped you with your experiment. Make sure to include course readings, outside sources, and other experiments that you may have used to design your own.

How to write the abstract

The abstract is the experiment stated “in a nutshell”: the procedure, results, and a few key words. The purpose of the academic abstract is to help a potential reader get an idea of the experiment so they can decide whether to read the full paper. So, make sure your abstract is as clear and direct as possible, and under 200 words (though word count varies).

When writing an abstract for a scientific lab report, we recommend covering the following points:

- Background : Why was this experiment conducted?

- Objectives : What problem is being addressed by this experiment?

- Methods : How was the study designed and conducted?

- Results : What results were found and what do they mean?

- Conclusion : Were the results expected? Is this problem better understood now than before? If so, how?

How to write the introduction

The introduction is another summary, of sorts, so it could be easy to confuse the introduction with the abstract. While the abstract tends to be around 200 words summarizing the entire study, the introduction can be longer if necessary, covering background information on the study, what you aim to accomplish, and your hypothesis. Unlike the abstract (or the conclusion), the introduction does not need to state the results of the experiment.

Here is a possible order with which you can organize your lab report introduction:

- Intro of the intro : Plainly state what your study is doing.

- Background : Provide a brief overview of the topic being studied. This could include key terms and definitions. This should not be an extensive literature review, but rather, a window into the most relevant topics a reader would need to understand in order to understand your research.

- Importance : Now, what are the gaps in existing research? Given the background you just provided, what questions do you still have that led you to conduct this experiment? Are you clarifying conflicting results? Are you undertaking a new area of research altogether?

- Prediction: The plants placed by the window will grow faster than plants placed in the dark corner.

- Hypothesis: Basil plants placed in direct sunlight for 2 hours per day grow at a higher rate than basil plants placed in direct sunlight for 30 minutes per day.

- How you test your hypothesis : This is an opportunity to briefly state how you go about your experiment, but this is not the time to get into specific details about your methods (save this for your results section). Keep this part down to one sentence, and voila! You have your introduction.

How to write a discussion section

Here, we’re skipping ahead to the next writing-heavy section, which will directly follow the numeric data of your experiment. The discussion includes any calculations and interpretations based on this data. In other words, it says, “Now that we have the data, why should we care?” This section asks, how does this data sit in relation to the hypothesis? Does it prove your hypothesis or disprove it? The discussion is also a good place to mention any mistakes that were made during the experiment, and ways you would improve the experiment if you were to repeat it. Like the other written sections, it should be as concise as possible.

Here is a list of points to cover in your lab report discussion:

- Weaker statement: These findings prove that basil plants grow more quickly in the sunlight.

- Stronger statement: These findings support the hypothesis that basil plants placed in direct sunlight grow at a higher rate than basil plants given less direct sunlight.

- Factors influencing results : This is also an opportunity to mention any anomalies, errors, or inconsistencies in your data. Perhaps when you tested the first round of basil plants, the days were sunnier than the others. Perhaps one of the basil pots broke mid-experiment so it needed to be replanted, which affected your results. If you were to repeat the study, how would you change it so that the results were more consistent?

- Implications : How do your results contribute to existing research? Here, refer back to the gaps in research that you mentioned in your introduction. Do these results fill these gaps as you hoped?

- Questions for future research : Based on this, how might your results contribute to future research? What are the next steps, or the next experiments on this topic? Make sure this does not become too broad—keep it to the scope of this project.

How to write a lab report conclusion

This is your opportunity to briefly remind the reader of your findings and finish strong. Your conclusion should be especially concise (avoid going into detail on findings or introducing new information).

Here are elements to include as you write your conclusion, in about 1-2 sentences each:

- Restate your goals : What was the main question of your experiment? Refer back to your introduction—similar language is okay.

- Restate your methods : In a sentence or so, how did you go about your experiment?

- Key findings : Briefly summarize your main results, but avoid going into detail.

- Limitations : What about your experiment was less-than-ideal, and how could you improve upon the experiment in future studies?

- Significance and future research : Why is your research important? What are the logical next-steps for studying this topic?

Template for beginning your lab report

Here is a compiled outline from the bullet points in these sections above, with some examples based on the (overly-simplistic) basil growth experiment. Hopefully this will be useful as you begin your lab report.

1) Title (ex: Effects of Sunlight on Basil Plant Growth )

2) Abstract (approx. 200 words)

- Background ( This experiment looks at… )

- Objectives ( It aims to contribute to research on…)

- Methods ( It does so through a process of…. )

- Results (Findings supported the hypothesis that… )

- Conclusion (These results contribute to a wider understanding about…)

3) Introduction (approx. 1-2 paragraphs)

- Intro ( This experiment looks at… )

- Background ( Past studies on basil plant growth and sunlight have found…)

- Importance ( This experiment will contribute to these past studies by…)

- Hypothesis ( Basil plants placed in direct sunlight for 2 hours per day grow at a higher rate than basil plants placed in direct sunlight for 30 minutes per day.)

- How you will test your hypothesis ( This hypothesis will be tested by a process of…)

4) Materials (list form) (ex: pots, soil, seeds, tables/stands, water, light source )

5) Methods (approx. 1-2 paragraphs) (ex: 10 basil plants were measured throughout a span of…)

6) Data (brief description and figures) (ex: These charts demonstrate a pattern that the basil plants placed in direct sunlight…)

7) Discussion (approx. 2-3 paragraphs)

- Support or reject hypothesis ( These findings support the hypothesis that basil plants placed in direct sunlight grow at a higher rate than basil plants given less direct sunlight.)

- Factors that influenced your results ( Outside factors that could have altered the results include…)

- Implications ( These results contribute to current research on basil plant growth and sunlight because…)

- Questions for further research ( Next steps for this research could include…)

- Restate your goals ( In summary, the goal of this experiment was to measure…)

- Restate your methods ( This hypothesis was tested by…)

- Key findings ( The findings supported the hypothesis because…)

- Limitations ( Although, certain elements were overlooked, including…)

- Significance and future research ( This experiment presents possibilities of future research contributions, such as…)

- Sources (approx. 1 page, usually in APA style)

Final thoughts – Lab Report Example

Hopefully, these descriptions have helped as you write your next lab report. Remember that different instructors may have different preferences for structure and format, so make sure to double-check when you receive your assignment. All in all, make sure to keep your scientific lab report concise, focused, honest, and organized. Good luck!

For more reading on coursework success, check out the following articles:

- How to Write the AP Lang Argument Essay (With Example)

- How to Write the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay (With Example)

- 49 Most Interesting Biology Research Topics

- 50 Best Environmental Science Research Topics

- High School Success

Sarah Mininsohn

With a BA from Wesleyan University and an MFA from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Sarah is a writer, educator, and artist. She served as a graduate instructor at the University of Illinois, a tutor at St Peter’s School in Philadelphia, and an academic writing tutor and thesis mentor at Wesleyan’s Writing Workshop.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Essay

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Data Visualizations

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High Schools

- Homeschool Resources

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Outdoor Adventure

- Private High School Spotlight

- Research Programs

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Teacher Tools

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 Writing the Materials and Methods (Methodology) Section

The Materials and Methods section briefly describes how you did your research. In other words, what did you do to answer your research question? If there were materials used for the research or materials experimented on you list them in this section. You also describe how you did the research or experiment. The key to a methodology is that another person must be able to replicate your research—follow the steps you take. For example if you used the internet to do a search it is not enough to say you “searched the internet.” A reader would need to know which search engine and what key words you used.

Open this section by describing the overall approach you took or the materials used. Then describe to the readers step-by-step the methods you used including any data analysis performed. See Fig. 2.5 below for an example of materials and methods section.

Writing tips:

- Explain procedures, materials, and equipment used

- Example: “We used an x-ray fluorescence spectrometer to analyze major and trace elements in the mystery mineral samples.”

- Order events chronologically, perhaps with subheadings (Field work, Lab Analysis, Statistical Models)

- Use past tense (you did X, Y, Z)

- Quantify measurements

- Include results in the methods! It’s easy to make this mistake!

- Example: “W e turned on the machine and loaded in our samples, then calibrated the instrument and pushed the start button and waited one hour. . . .”

Technical Writing @ SLCC Copyright © 2020 by Department of English, Linguistics, and Writing Studies at SLCC is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How to Write a Lab Report

Lab Reports Describe Your Experiment

- Chemical Laws

- Periodic Table

- Projects & Experiments

- Scientific Method

- Biochemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Medical Chemistry

- Chemistry In Everyday Life

- Famous Chemists

- Activities for Kids

- Abbreviations & Acronyms

- Weather & Climate

- Ph.D., Biomedical Sciences, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

- B.A., Physics and Mathematics, Hastings College

Lab reports are an essential part of all laboratory courses and usually a significant part of your grade. If your instructor gives you an outline for how to write a lab report, use that. Some instructors require a lab report to be included in a lab notebook , while others will request a separate report. Here's a format for a lab report you can use if you aren't sure what to write or need an explanation of what to include in the different parts of the report.

A lab report is how you explain what you did in your experiment, what you learned, and what the results meant.

Lab Report Essentials

Not all lab reports have title pages, but if your instructor wants one, it would be a single page that states:

- The title of the experiment.

- Your name and the names of any lab partners.

- Your instructor's name.

- The date the lab was performed or the date the report was submitted.

The title says what you did. It should be brief (aim for ten words or less) and describe the main point of the experiment or investigation. An example of a title would be: "Effects of Ultraviolet Light on Borax Crystal Growth Rate". If you can, begin your title using a keyword rather than an article like "The" or "A".

Introduction or Purpose

Usually, the introduction is one paragraph that explains the objectives or purpose of the lab. In one sentence, state the hypothesis. Sometimes an introduction may contain background information, briefly summarize how the experiment was performed, state the findings of the experiment, and list the conclusions of the investigation. Even if you don't write a whole introduction, you need to state the purpose of the experiment, or why you did it. This would be where you state your hypothesis .

List everything needed to complete your experiment.

Describe the steps you completed during your investigation. This is your procedure. Be sufficiently detailed that anyone could read this section and duplicate your experiment. Write it as if you were giving direction for someone else to do the lab. It may be helpful to provide a figure to diagram your experimental setup.

Numerical data obtained from your procedure usually presented as a table. Data encompasses what you recorded when you conducted the experiment. It's just the facts, not any interpretation of what they mean.

Describe in words what the data means. Sometimes the Results section is combined with the Discussion.

Discussion or Analysis

The Data section contains numbers; the Analysis section contains any calculations you made based on those numbers. This is where you interpret the data and determine whether or not a hypothesis was accepted. This is also where you would discuss any mistakes you might have made while conducting the investigation. You may wish to describe ways the study might have been improved.

Conclusions

Most of the time the conclusion is a single paragraph that sums up what happened in the experiment, whether your hypothesis was accepted or rejected, and what this means.

Figures and Graphs

Graphs and figures must both be labeled with a descriptive title. Label the axes on a graph, being sure to include units of measurement. The independent variable is on the X-axis, the dependent variable (the one you are measuring) is on the Y-axis. Be sure to refer to figures and graphs in the text of your report: the first figure is Figure 1, the second figure is Figure 2, etc.

If your research was based on someone else's work or if you cited facts that require documentation, then you should list these references.

- The 10 Most Important Lab Safety Rules

- Null Hypothesis Examples

- Examples of Independent and Dependent Variables

- How to Format a Biology Lab Report

- Science Lab Report Template - Fill in the Blanks

- How to Write a Science Fair Project Report

- How to Write an Abstract for a Scientific Paper

- Six Steps of the Scientific Method

- How To Design a Science Fair Experiment

- Make a Science Fair Poster or Display

- Understanding Simple vs Controlled Experiments

- How to Organize Your Science Fair Poster

- Scientific Method Lesson Plan

- What Is an Experiment? Definition and Design

- What Are the Elements of a Good Hypothesis?

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Your Methods

Ensure understanding, reproducibility and replicability

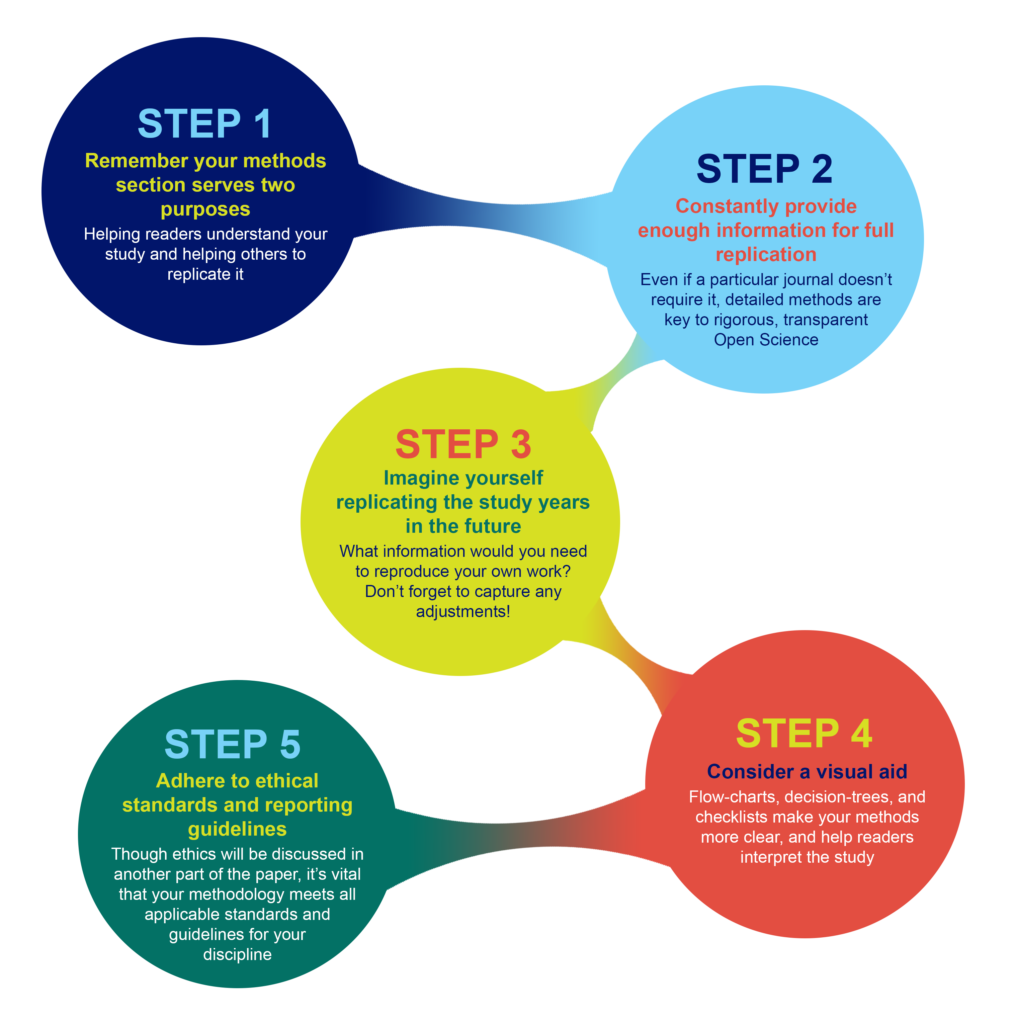

What should you include in your methods section, and how much detail is appropriate?

Why Methods Matter

The methods section was once the most likely part of a paper to be unfairly abbreviated, overly summarized, or even relegated to hard-to-find sections of a publisher’s website. While some journals may responsibly include more detailed elements of methods in supplementary sections, the movement for increased reproducibility and rigor in science has reinstated the importance of the methods section. Methods are now viewed as a key element in establishing the credibility of the research being reported, alongside the open availability of data and results.

A clear methods section impacts editorial evaluation and readers’ understanding, and is also the backbone of transparency and replicability.

For example, the Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology project set out in 2013 to replicate experiments from 50 high profile cancer papers, but revised their target to 18 papers once they understood how much methodological detail was not contained in the original papers.

What to include in your methods section

What you include in your methods sections depends on what field you are in and what experiments you are performing. However, the general principle in place at the majority of journals is summarized well by the guidelines at PLOS ONE : “The Materials and Methods section should provide enough detail to allow suitably skilled investigators to fully replicate your study. ” The emphases here are deliberate: the methods should enable readers to understand your paper, and replicate your study. However, there is no need to go into the level of detail that a lay-person would require—the focus is on the reader who is also trained in your field, with the suitable skills and knowledge to attempt a replication.

A constant principle of rigorous science

A methods section that enables other researchers to understand and replicate your results is a constant principle of rigorous, transparent, and Open Science. Aim to be thorough, even if a particular journal doesn’t require the same level of detail . Reproducibility is all of our responsibility. You cannot create any problems by exceeding a minimum standard of information. If a journal still has word-limits—either for the overall article or specific sections—and requires some methodological details to be in a supplemental section, that is OK as long as the extra details are searchable and findable .

Imagine replicating your own work, years in the future

As part of PLOS’ presentation on Reproducibility and Open Publishing (part of UCSF’s Reproducibility Series ) we recommend planning the level of detail in your methods section by imagining you are writing for your future self, replicating your own work. When you consider that you might be at a different institution, with different account logins, applications, resources, and access levels—you can help yourself imagine the level of specificity that you yourself would require to redo the exact experiment. Consider:

- Which details would you need to be reminded of?

- Which cell line, or antibody, or software, or reagent did you use, and does it have a Research Resource ID (RRID) that you can cite?

- Which version of a questionnaire did you use in your survey?

- Exactly which visual stimulus did you show participants, and is it publicly available?

- What participants did you decide to exclude?

- What process did you adjust, during your work?

Tip: Be sure to capture any changes to your protocols

You yourself would want to know about any adjustments, if you ever replicate the work, so you can surmise that anyone else would want to as well. Even if a necessary adjustment you made was not ideal, transparency is the key to ensuring this is not regarded as an issue in the future. It is far better to transparently convey any non-optimal methods, or methodological constraints, than to conceal them, which could result in reproducibility or ethical issues downstream.

Visual aids for methods help when reading the whole paper

Consider whether a visual representation of your methods could be appropriate or aid understanding your process. A visual reference readers can easily return to, like a flow-diagram, decision-tree, or checklist, can help readers to better understand the complete article, not just the methods section.

Ethical Considerations

In addition to describing what you did, it is just as important to assure readers that you also followed all relevant ethical guidelines when conducting your research. While ethical standards and reporting guidelines are often presented in a separate section of a paper, ensure that your methods and protocols actually follow these guidelines. Read more about ethics .

Existing standards, checklists, guidelines, partners

While the level of detail contained in a methods section should be guided by the universal principles of rigorous science outlined above, various disciplines, fields, and projects have worked hard to design and develop consistent standards, guidelines, and tools to help with reporting all types of experiment. Below, you’ll find some of the key initiatives. Ensure you read the submission guidelines for the specific journal you are submitting to, in order to discover any further journal- or field-specific policies to follow, or initiatives/tools to utilize.

Tip: Keep your paper moving forward by providing the proper paperwork up front

Be sure to check the journal guidelines and provide the necessary documents with your manuscript submission. Collecting the necessary documentation can greatly slow the first round of peer review, or cause delays when you submit your revision.

Randomized Controlled Trials – CONSORT The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) project covers various initiatives intended to prevent the problems of inadequate reporting of randomized controlled trials. The primary initiative is an evidence-based minimum set of recommendations for reporting randomized trials known as the CONSORT Statement .

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses – PRISMA The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses ( PRISMA ) is an evidence-based minimum set of items focusing on the reporting of reviews evaluating randomized trials and other types of research.

Research using Animals – ARRIVE The Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments ( ARRIVE ) guidelines encourage maximizing the information reported in research using animals thereby minimizing unnecessary studies. (Original study and proposal , and updated guidelines , in PLOS Biology .)

Laboratory Protocols Protocols.io has developed a platform specifically for the sharing and updating of laboratory protocols , which are assigned their own DOI and can be linked from methods sections of papers to enhance reproducibility. Contextualize your protocol and improve discovery with an accompanying Lab Protocol article in PLOS ONE .

Consistent reporting of Materials, Design, and Analysis – the MDAR checklist A cross-publisher group of editors and experts have developed, tested, and rolled out a checklist to help establish and harmonize reporting standards in the Life Sciences . The checklist , which is available for use by authors to compile their methods, and editors/reviewers to check methods, establishes a minimum set of requirements in transparent reporting and is adaptable to any discipline within the Life Sciences, by covering a breadth of potentially relevant methodological items and considerations. If you are in the Life Sciences and writing up your methods section, try working through the MDAR checklist and see whether it helps you include all relevant details into your methods, and whether it reminded you of anything you might have missed otherwise.

Summary Writing tips

The main challenge you may find when writing your methods is keeping it readable AND covering all the details needed for reproducibility and replicability. While this is difficult, do not compromise on rigorous standards for credibility!

- Keep in mind future replicability, alongside understanding and readability.

- Follow checklists, and field- and journal-specific guidelines.

- Consider a commitment to rigorous and transparent science a personal responsibility, and not just adhering to journal guidelines.

- Establish whether there are persistent identifiers for any research resources you use that can be specifically cited in your methods section.

- Deposit your laboratory protocols in Protocols.io, establishing a permanent link to them. You can update your protocols later if you improve on them, as can future scientists who follow your protocols.

- Consider visual aids like flow-diagrams, lists, to help with reading other sections of the paper.

- Be specific about all decisions made during the experiments that someone reproducing your work would need to know.

Don’t

- Summarize or abbreviate methods without giving full details in a discoverable supplemental section.

- Presume you will always be able to remember how you performed the experiments, or have access to private or institutional notebooks and resources.

- Attempt to hide constraints or non-optimal decisions you had to make–transparency is the key to ensuring the credibility of your research.

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Write An Effective Lab Report

Whether you are in lab for general chemistry, independent work, or senior thesis, almost all lab experiments will be followed up with a lab report or paper. Although it should be relatively easy to write about an experiment you completed, this is often the most difficult part of lab work, especially when the results are unexpected. In this post, I will outline the components of a lab report while offering tips on how to write one.

Understand Your Experiments Thoroughly

Before you begin writing your draft, it is important that you understand your experiment, as this will help you decide what to include in your paper. When I wrote my first organic chemistry lab report, I rushed to begin answering the discussion questions only to realize halfway through that I had a major conceptual error. Because of this, I had to revise most of what I had written so far, which cost me a lot of time. Know what the purpose of the lab is, formulate the hypothesis, and begin to think about the results you are expecting. At this point, it is helpful to check in with your Lab TA, mentor, or principal investigator (PI) to ensure that you thoroughly understand your project.

The abstract of your lab report will generally consist of a short summary of your entire report, typically in the same order as your report. Although this is the first section of your lab report, this should be the last section you write. Rather than trying to follow your entire report based on your abstract, it is easier if you write your report first before trying to summarize it.

Introduction and Background

The introduction and background of your report should establish the purpose of your experiment (what principles you are examining), your hypothesis (what you expect to see and why), and relevant findings from others in the field. You have likely done extensive reading about the project from textbooks, lecture notes, or scholarly articles. But as you write, only include background information that is relevant to your specific experiments. For instance, over the summer when I was still learning about metabolic engineering and its role in yeast cells, I read several articles detailing this process. However, a lot of this information was a very broad introduction to the field and not directly related to my project, so I decided not to include most of it.

This section of the lab report should not contain a step-by-step procedure of your experiments, but rather enough details should be included so that someone else can understand and replicate what you did. From this section, the reader should understand how you tested your hypothesis and why you chose that method. Explain the different parts of your project, the variables being tested, and controls in your experiments. This section will validate the data presented by confirming that variables are being tested in a proper way.

You cannot change the data you collect from your experiments; thus the results section will be written for you. Your job is to present these results in appropriate tables and charts. Depending on the length of your project, you may have months of data from experiments or just a three-hour lab period worth of results. For example, for in-class lab reports, there is usually only one major experiment, so I include most of the data I collect in my lab report. But for longer projects such as summer internships, there are various preliminary experiments throughout, so I select the data to include. Although you cannot change the data, you must choose what is relevant to include in your report. Determine what is included in your report based on the goals and purpose of your project.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this section, you should analyze your results and relate your data back to your hypothesis. You should mention whether the results you obtained matched what was expected and the conclusions that can be drawn from this. For this section, you should talk about your data and conclusions with your lab mentors or TAs before you begin writing. As I mentioned above, by consulting with your mentors, you will avoid making large conceptual error that may take a long time to address.