revision (composition)

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In composition , revision is the process of rereading a text and making changes (in content, organization , sentence structures , and word choice ) to improve it.

During the revision stage of the writing process , writers may add, remove, move and substitute text (the ARMS treatment). "[T]hey have opportunities to think about whether their text communicates effectively to an audience , to improve the quality of their prose , and even to reconsider their content and perspective and potentially transform their own understanding" (Charles MacArthur in Best Practices in Writing Instruction , 2013).

"Leon approved of revision," says Lee Child in his novel Persuader (2003). "He approved of it big time. Mainly because revision was about thinking, and he figured thinking never hurt anybody." See the Observations and Recommendations below. Also see:

- Revision Checklist

- Writers on Rewriting

- Audience Analysis Checklist

- The Best Time to Stop Rewriting: Russell Baker on the Perils of Obsessive Revision

- Campaign to Cut the Clutter: Zinsser's Brackets

- Collaborative Writing and Peer Response

- Common Revision Symbols and Abbreviations

- The Invisible Mark of Punctuation: The Paragraph Break

- Revising an Argument Essay

- Revising a Place Description

- Revision and Editing Checklist for a Critical Essay

- Two Versions of "Kidnapped by Movies," by Susan Sontag

- Writers on Writing: Ten Tips for Finding the Right Words

- Writing Portfolio

- The Writing Process

Etymology From the Latin, "to visit again, to look at again"

Observations and Recommendations

- "Rewriting is the essence of writing well: it's where the game is won or lost." (William Zinsser, On Writing Well . 2006)

- " [R]evision begins with the large view and proceeds from the outside in, from overall structure to paragraphs and finally sentences and words, toward ever more intricate levels of detail. In other words, there's no sense in revising a sentence to a hard shining beauty if the passage including that sentence will have to be cut." (Philip Gerard, Creative Nonfiction: Researching and Crafting Stories of Real Life . Story Press, 1996)

- "Writing is revising , and the writer's craft is largely a matter of knowing how to discover what you have to say, develop, and clarify it, each requiring the craft of revision ." (Donald M. Murray, The Craft of Revision , 5th ed. Wadsworth, 2003)

- Fixing the Mess " Revision is a grand term for the frantic process of fixing the mess. . . . I just keep reading the story, first on the tube, then in paper form, usually standing up at a file cabinet far from my desk, tinkering and tinkering, shifting paragraphs around, throwing out words, shortening sentences, worrying and fretting, checking spelling and job titles and numbers." (David Mehegan, quoted by Donald M. Murray in Writing to Deadline . Heinemann, 2000)

- Two Kinds of Rewriting "[T]here are at least two kinds of rewriting. The first is trying to fix what you've already written, but doing this can keep you from facing up to the second kind, from figuring out the essential thing you're trying to do and looking for better ways to tell your story. If [F. Scott] Fitzgerald had been advising a young writer and not himself he might have said, 'Rewrite from principle,' or 'Don't just push the same old stuff around. Throw it away and start over.'" (Tracy Kidder and Richard Todd, Good Prose: The Art of Nonfiction . Random House, 2013)

- A Form of Self-Forgiveness "I like to think of revision as a form of self-forgiveness: you can allow yourself mistakes and shortcomings in your writing because you know you're coming back later to improve it. Revision is the way you cope with bad luck that made your writing less than excellent this morning. Revision is the hope you hold out for yourself to make something beautiful tomorrow though you didn't quite manage it today. Revision is democracy's literary method, the tool that allows an ordinary person to aspire to extraordinary achievement." (David Huddle, The Writing Habit . Peregrine Smith, 1991)

- Peer Revising "Peer revising is a common feature of writing-process classrooms, and it is often recommended as a way of providing student writers with an audience of readers who can respond to their writing, identify strengths and and problems, and recommend improvements. Students may learn from serving in roles of both author and editor . The critical reading required as an editor can contribute to learning how to evaluate writing. Peer revising is most effective when it is combined with instruction based on evaluation criteria or revising strategies." (Charles A. MacArthur, "Best Practices in Teaching Evaluation and Revision." Best Practices in Writing Instruction , ed. by Steve Graham, Charles A. MacArthur, and Jill Fitzgerald. Guilford Press, 2007)

- Revising Out Loud "You will find, to your delight, that reading your own work aloud, even silently, is the most astonishingly easy and reliable method that there is for achieving economy in prose, efficiency of description, and narrative effect as well." (George V. Higgins, On Writing . Henry Holt, 1990)

- Writers on Revising - "We have discovered that writing allows even a stupid person to seem halfway intelligent, if only that person will write the same thought over and over again, improving it just a little bit each time. It is a lot like inflating a blimp with a bicycle pump. Anybody can do it. All it takes is time." (Kurt Vonnegut, Palm Sunday: An Autobiographical Collage . Random House, 1981) - "Beginning writers everywhere might take a lesson from [Lafcadio] Hearn's working method: when he thought he was finished with a piece, he put it in his desk drawer for a time, then took it out to revise it, then returned it to the drawer, a process that continued until he had exactly what he wanted." (Francine Prose, "Serene Japan." Smithsonian , September 2009) - "An excellent rule for writers is this: Condense your article to the last possible point consistent with clearness. Then cut off its head and tail, and serve up the remains with the sauce of good humor." (C.A.S. Dwight, "The Religious Press." The Editor , 1897) - " Revision is one of the exquisite pleasures of writing.” (Bernard Malamud, Talking Horse: Bernard Malamud on Life and Work , ed. by Alan Cheuse and Nichola Delbanco. Columbia University Press, 1996) - "I rewrite a great deal. I'm always fiddling, always changing something. I'll write a few words--then I'll change them. I add. I subtract. I work and fiddle and keep working and fiddling, and I only stop at the deadline." (Ellen Goodman) - "I'm not a very good writer, but I'm an excellent rewriter." (James Michener) - "Writing is like everything else: the more you do it the better you get. Don't try to perfect as you go along, just get to the end of the damn thing. Accept imperfections. Get it finished and then you can go back. If you try to polish every sentence there's a chance you'll never get past the first chapter." (Iain Banks) - " Revision is very important to me. I just can't abide some things that I write. I look at them the next day and they're terrible. They don't make sense, or they're awkward, or they're not to the point--so I have to revise, cut, shape. Sometimes I throw the whole thing away and start from scratch." (William Kennedy) - "Successful writing takes great exertion, and multiple revisions , refinement, retooling--until it looks as if it didn't take any effort at all." (Dinty W. Moore, The Mindful Writer . Wisdom Publications, 2012)

- Jacques Barzun on the Pleasures of Revision "Rewriting is called revision in the literary and publishing trade because it springs from re-viewing , that is to say, looking at your copy again--and again and again. When you have learned to look at your own words with critical detachment, you will find that rereading a piece five or six times in a row will each time bring to light fresh spots of trouble. The trouble is sometimes elementary: you wonder how you can have written it as a pronoun referring to a plural subject. The slip is easily corrected. At other times you have written yourself into a corner, the exit from which is not at once apparent. Your words down there seem to preclude the necessary repairs up here--because of repetition, syntax, logic, or some other obstacle. Nothing comes to mind as reconciling sense with sound and with clarity in both places. In such a fix you may have to start farther back and pursue a different line altogether. The sharper your judgment, the more trouble you will find. That is why exacting writers are known to have rewritten a famous paragraph or chapter six or seven times. It then looked right to them, because every demand of their art had been met, every flaw removed, down to the slightest. "You and I are far from that stage of mastery, but we are none the less obliged to do some rewriting beyond the intensive correction of bad spots. For in the act of revising on the small scale one comes upon gaps in thought and--what is as bad--real or apparent repetitions or intrusions, sometimes called backstitching . Both are occasions for surgery. In the first case you must write a new fragment and insert it so that its beginning and end fit what precedes and follows. In the second case you must lift the intruding passage and transfer or eliminate it. Simple arithmetic shows you that there are then three and not two sutures to be made before the page shows a smooth surface. If you have never performed this sort of work in writing, you must take it from me that it affords pleasure and satisfaction, both. (Jacques Barzun, Simple and Direct: A Rhetoric for Writers , 4th ed. Harper Perennial, 2001)

- John McPhee on the End of Revision "People often ask how I know when I'm done--not just when I've come to the end, but in all the drafts and revisions and substitutions of one word for another how do I know there is no more to do? When am I done? I just know. I'm lucky that way. What I know is that I can't do any better; someone else might do better, but that's all I can do; so I call it done." (John McPhee, "Structure." The New Yorker , January 14, 2013)

Pronunciation: re-VIZH-en

- Examples of Great Introductory Paragraphs

- How Do You Edit an Essay?

- Explore and Evaluate Your Writing Process

- An Essay Revision Checklist

- 10 Tips for Finding the Right Words

- The Difference Between Revising and Editing

- Self-Evaluation of Essays

- The Drafting Stage of the Writing Process

- Imitation in Rhetoric and Composition

- A Writing Portfolio Can Help You Perfect Your Writing Skills

- Focusing in Composition

- John McPhee: His Life and Work

- Revision and Editing Checklist for a Narrative Essay

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- How to Write a Letter of Complaint

- Cohesion Exercise: Building and Connecting Sentences

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.4 Revising and Editing

Learning objectives.

- Identify major areas of concern in the draft essay during revising and editing.

- Use peer reviews and editing checklists to assist revising and editing.

- Revise and edit the first draft of your essay and produce a final draft.

Revising and editing are the two tasks you undertake to significantly improve your essay. Both are very important elements of the writing process. You may think that a completed first draft means little improvement is needed. However, even experienced writers need to improve their drafts and rely on peers during revising and editing. You may know that athletes miss catches, fumble balls, or overshoot goals. Dancers forget steps, turn too slowly, or miss beats. For both athletes and dancers, the more they practice, the stronger their performance will become. Web designers seek better images, a more clever design, or a more appealing background for their web pages. Writing has the same capacity to profit from improvement and revision.

Understanding the Purpose of Revising and Editing

Revising and editing allow you to examine two important aspects of your writing separately, so that you can give each task your undivided attention.

- When you revise , you take a second look at your ideas. You might add, cut, move, or change information in order to make your ideas clearer, more accurate, more interesting, or more convincing.

- When you edit , you take a second look at how you expressed your ideas. You add or change words. You fix any problems in grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure. You improve your writing style. You make your essay into a polished, mature piece of writing, the end product of your best efforts.

How do you get the best out of your revisions and editing? Here are some strategies that writers have developed to look at their first drafts from a fresh perspective. Try them over the course of this semester; then keep using the ones that bring results.

- Take a break. You are proud of what you wrote, but you might be too close to it to make changes. Set aside your writing for a few hours or even a day until you can look at it objectively.

- Ask someone you trust for feedback and constructive criticism.

- Pretend you are one of your readers. Are you satisfied or dissatisfied? Why?

- Use the resources that your college provides. Find out where your school’s writing lab is located and ask about the assistance they provide online and in person.

Many people hear the words critic , critical , and criticism and pick up only negative vibes that provoke feelings that make them blush, grumble, or shout. However, as a writer and a thinker, you need to learn to be critical of yourself in a positive way and have high expectations for your work. You also need to train your eye and trust your ability to fix what needs fixing. For this, you need to teach yourself where to look.

Creating Unity and Coherence

Following your outline closely offers you a reasonable guarantee that your writing will stay on purpose and not drift away from the controlling idea. However, when writers are rushed, are tired, or cannot find the right words, their writing may become less than they want it to be. Their writing may no longer be clear and concise, and they may be adding information that is not needed to develop the main idea.

When a piece of writing has unity , all the ideas in each paragraph and in the entire essay clearly belong and are arranged in an order that makes logical sense. When the writing has coherence , the ideas flow smoothly. The wording clearly indicates how one idea leads to another within a paragraph and from paragraph to paragraph.

Reading your writing aloud will often help you find problems with unity and coherence. Listen for the clarity and flow of your ideas. Identify places where you find yourself confused, and write a note to yourself about possible fixes.

Creating Unity

Sometimes writers get caught up in the moment and cannot resist a good digression. Even though you might enjoy such detours when you chat with friends, unplanned digressions usually harm a piece of writing.

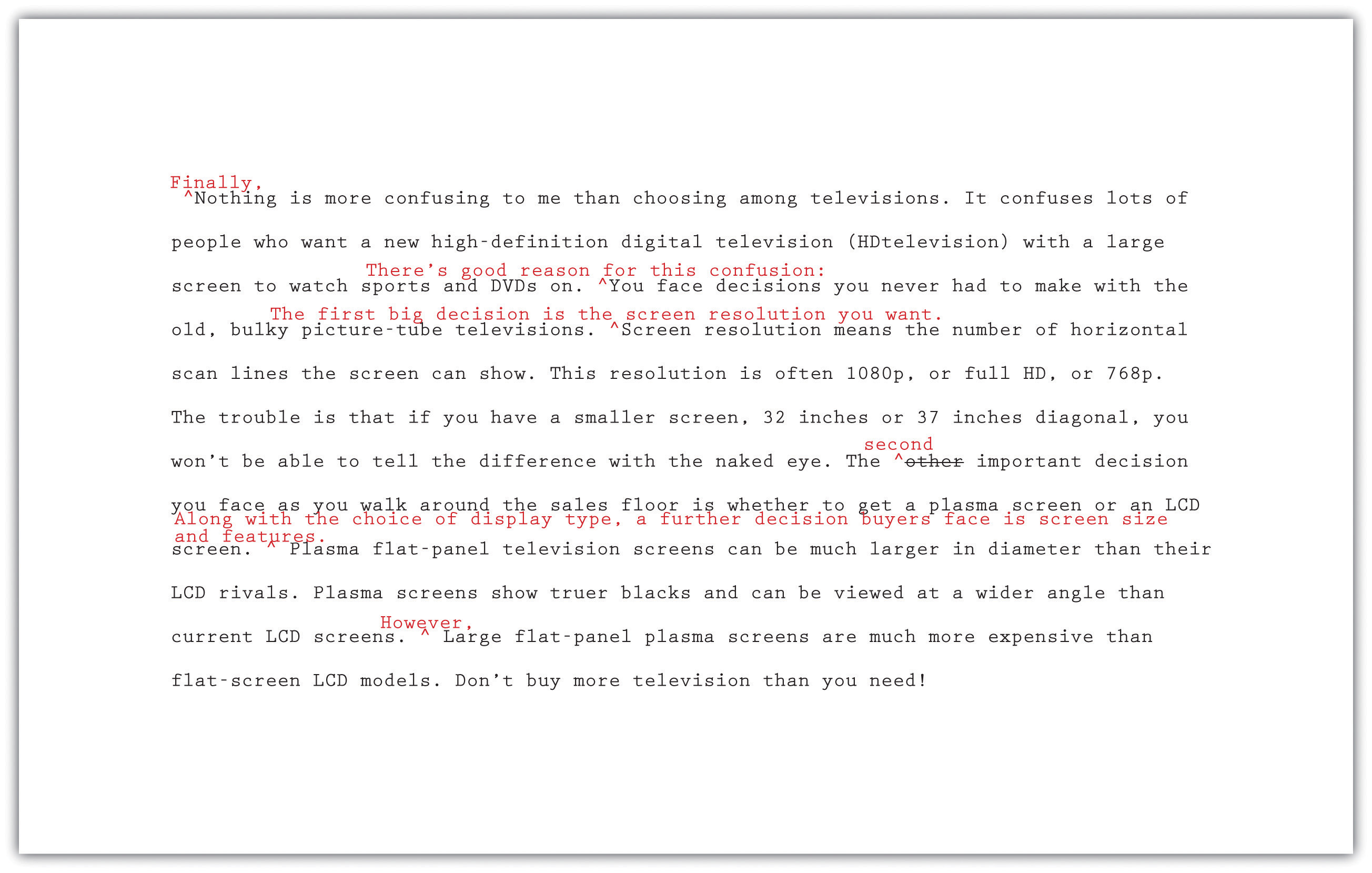

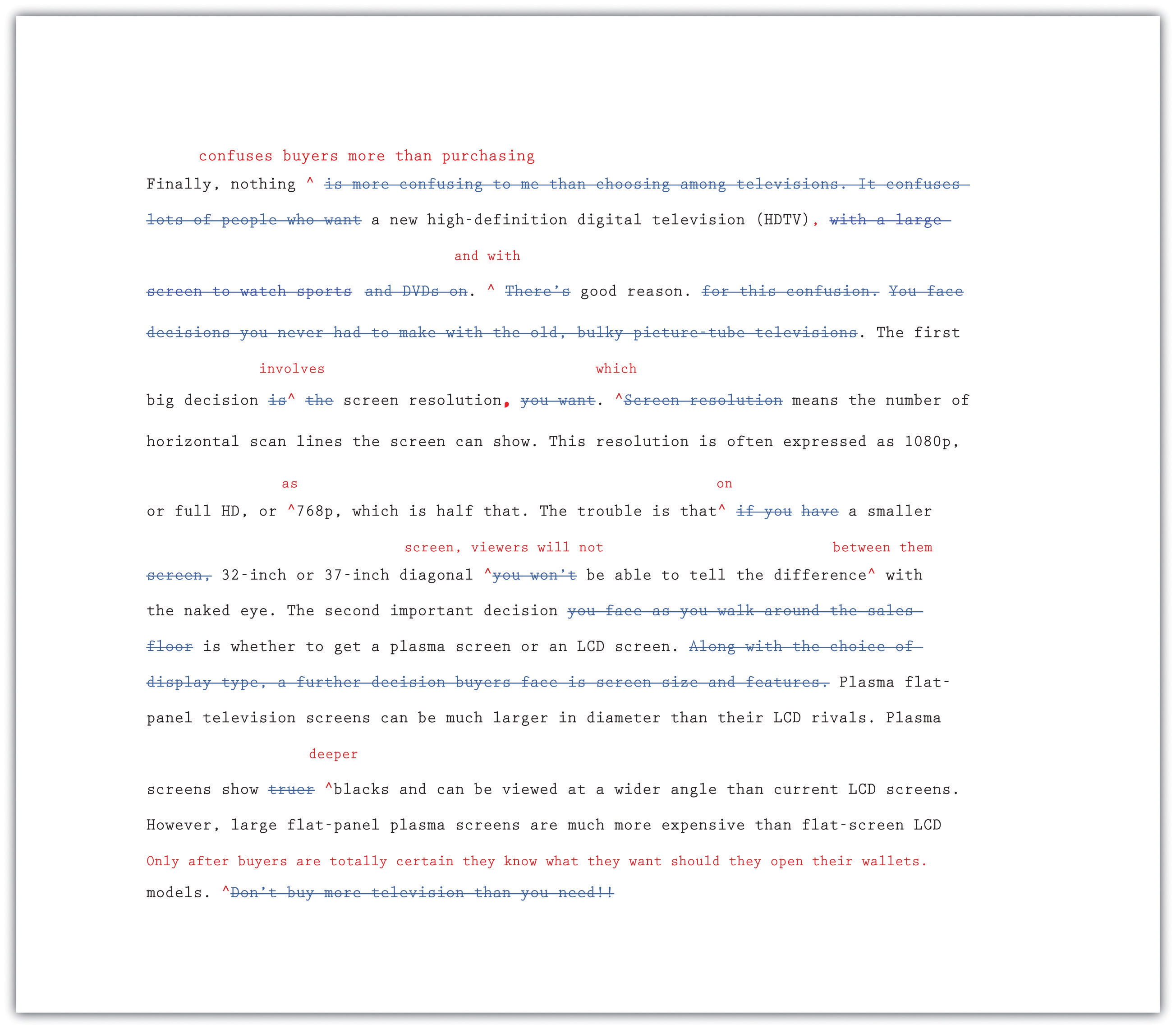

Mariah stayed close to her outline when she drafted the three body paragraphs of her essay she tentatively titled “Digital Technology: The Newest and the Best at What Price?” But a recent shopping trip for an HDTV upset her enough that she digressed from the main topic of her third paragraph and included comments about the sales staff at the electronics store she visited. When she revised her essay, she deleted the off-topic sentences that affected the unity of the paragraph.

Read the following paragraph twice, the first time without Mariah’s changes, and the second time with them.

Nothing is more confusing to me than choosing among televisions. It confuses lots of people who want a new high-definition digital television (HDTV) with a large screen to watch sports and DVDs on. You could listen to the guys in the electronics store, but word has it they know little more than you do. They want to sell what they have in stock, not what best fits your needs. You face decisions you never had to make with the old, bulky picture-tube televisions. Screen resolution means the number of horizontal scan lines the screen can show. This resolution is often 1080p, or full HD, or 768p. The trouble is that if you have a smaller screen, 32 inches or 37 inches diagonal, you won’t be able to tell the difference with the naked eye. The 1080p televisions cost more, though, so those are what the salespeople want you to buy. They get bigger commissions. The other important decision you face as you walk around the sales floor is whether to get a plasma screen or an LCD screen. Now here the salespeople may finally give you decent info. Plasma flat-panel television screens can be much larger in diameter than their LCD rivals. Plasma screens show truer blacks and can be viewed at a wider angle than current LCD screens. But be careful and tell the salesperson you have budget constraints. Large flat-panel plasma screens are much more expensive than flat-screen LCD models. Don’t let someone make you by more television than you need!

Answer the following two questions about Mariah’s paragraph:

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

- Now start to revise the first draft of the essay you wrote in Section 8 “Writing Your Own First Draft” . Reread it to find any statements that affect the unity of your writing. Decide how best to revise.

When you reread your writing to find revisions to make, look for each type of problem in a separate sweep. Read it straight through once to locate any problems with unity. Read it straight through a second time to find problems with coherence. You may follow this same practice during many stages of the writing process.

Writing at Work

Many companies hire copyeditors and proofreaders to help them produce the cleanest possible final drafts of large writing projects. Copyeditors are responsible for suggesting revisions and style changes; proofreaders check documents for any errors in capitalization, spelling, and punctuation that have crept in. Many times, these tasks are done on a freelance basis, with one freelancer working for a variety of clients.

Creating Coherence

Careful writers use transitions to clarify how the ideas in their sentences and paragraphs are related. These words and phrases help the writing flow smoothly. Adding transitions is not the only way to improve coherence, but they are often useful and give a mature feel to your essays. Table 8.3 “Common Transitional Words and Phrases” groups many common transitions according to their purpose.

Table 8.3 Common Transitional Words and Phrases

After Maria revised for unity, she next examined her paragraph about televisions to check for coherence. She looked for places where she needed to add a transition or perhaps reword the text to make the flow of ideas clear. In the version that follows, she has already deleted the sentences that were off topic.

Many writers make their revisions on a printed copy and then transfer them to the version on-screen. They conventionally use a small arrow called a caret (^) to show where to insert an addition or correction.

1. Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph.

2. Now return to the first draft of the essay you wrote in Section 8 “Writing Your Own First Draft” and revise it for coherence. Add transition words and phrases where they are needed, and make any other changes that are needed to improve the flow and connection between ideas.

Being Clear and Concise

Some writers are very methodical and painstaking when they write a first draft. Other writers unleash a lot of words in order to get out all that they feel they need to say. Do either of these composing styles match your style? Or is your composing style somewhere in between? No matter which description best fits you, the first draft of almost every piece of writing, no matter its author, can be made clearer and more concise.

If you have a tendency to write too much, you will need to look for unnecessary words. If you have a tendency to be vague or imprecise in your wording, you will need to find specific words to replace any overly general language.

Identifying Wordiness

Sometimes writers use too many words when fewer words will appeal more to their audience and better fit their purpose. Here are some common examples of wordiness to look for in your draft. Eliminating wordiness helps all readers, because it makes your ideas clear, direct, and straightforward.

Sentences that begin with There is or There are .

Wordy: There are two major experiments that the Biology Department sponsors.

Revised: The Biology Department sponsors two major experiments.

Sentences with unnecessary modifiers.

Wordy: Two extremely famous and well-known consumer advocates spoke eloquently in favor of the proposed important legislation.

Revised: Two well-known consumer advocates spoke in favor of the proposed legislation.

Sentences with deadwood phrases that add little to the meaning. Be judicious when you use phrases such as in terms of , with a mind to , on the subject of , as to whether or not , more or less , as far as…is concerned , and similar expressions. You can usually find a more straightforward way to state your point.

Wordy: As a world leader in the field of green technology, the company plans to focus its efforts in the area of geothermal energy.

A report as to whether or not to use geysers as an energy source is in the process of preparation.

Revised: As a world leader in green technology, the company plans to focus on geothermal energy.

A report about using geysers as an energy source is in preparation.

Sentences in the passive voice or with forms of the verb to be . Sentences with passive-voice verbs often create confusion, because the subject of the sentence does not perform an action. Sentences are clearer when the subject of the sentence performs the action and is followed by a strong verb. Use strong active-voice verbs in place of forms of to be , which can lead to wordiness. Avoid passive voice when you can.

Wordy: It might perhaps be said that using a GPS device is something that is a benefit to drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

Revised: Using a GPS device benefits drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

Sentences with constructions that can be shortened.

Wordy: The e-book reader, which is a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone.

My over-sixty uncle bought an e-book reader, and his wife bought an e-book reader, too.

Revised: The e-book reader, a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone.

My over-sixty uncle and his wife both bought e-book readers.

Now return once more to the first draft of the essay you have been revising. Check it for unnecessary words. Try making your sentences as concise as they can be.

Choosing Specific, Appropriate Words

Most college essays should be written in formal English suitable for an academic situation. Follow these principles to be sure that your word choice is appropriate. For more information about word choice, see Chapter 4 “Working with Words: Which Word Is Right?” .

- Avoid slang. Find alternatives to bummer , kewl , and rad .

- Avoid language that is overly casual. Write about “men and women” rather than “girls and guys” unless you are trying to create a specific effect. A formal tone calls for formal language.

- Avoid contractions. Use do not in place of don’t , I am in place of I’m , have not in place of haven’t , and so on. Contractions are considered casual speech.

- Avoid clichés. Overused expressions such as green with envy , face the music , better late than never , and similar expressions are empty of meaning and may not appeal to your audience.

- Be careful when you use words that sound alike but have different meanings. Some examples are allusion/illusion , complement/compliment , council/counsel , concurrent/consecutive , founder/flounder , and historic/historical . When in doubt, check a dictionary.

- Choose words with the connotations you want. Choosing a word for its connotations is as important in formal essay writing as it is in all kinds of writing. Compare the positive connotations of the word proud and the negative connotations of arrogant and conceited .

- Use specific words rather than overly general words. Find synonyms for thing , people , nice , good , bad , interesting , and other vague words. Or use specific details to make your exact meaning clear.

Now read the revisions Mariah made to make her third paragraph clearer and more concise. She has already incorporated the changes she made to improve unity and coherence.

1. Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph:

2. Now return once more to your essay in progress. Read carefully for problems with word choice. Be sure that your draft is written in formal language and that your word choice is specific and appropriate.

Completing a Peer Review

After working so closely with a piece of writing, writers often need to step back and ask for a more objective reader. What writers most need is feedback from readers who can respond only to the words on the page. When they are ready, writers show their drafts to someone they respect and who can give an honest response about its strengths and weaknesses.

You, too, can ask a peer to read your draft when it is ready. After evaluating the feedback and assessing what is most helpful, the reader’s feedback will help you when you revise your draft. This process is called peer review .

You can work with a partner in your class and identify specific ways to strengthen each other’s essays. Although you may be uncomfortable sharing your writing at first, remember that each writer is working toward the same goal: a final draft that fits the audience and the purpose. Maintaining a positive attitude when providing feedback will put you and your partner at ease. The box that follows provides a useful framework for the peer review session.

Questions for Peer Review

Title of essay: ____________________________________________

Date: ____________________________________________

Writer’s name: ____________________________________________

Peer reviewer’s name: _________________________________________

- This essay is about____________________________________________.

- Your main points in this essay are____________________________________________.

- What I most liked about this essay is____________________________________________.

These three points struck me as your strongest:

These places in your essay are not clear to me:

a. Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because__________________________________________

b. Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because ____________________________________________

c. Where: ____________________________________________

The one additional change you could make that would improve this essay significantly is ____________________________________________.

One of the reasons why word-processing programs build in a reviewing feature is that workgroups have become a common feature in many businesses. Writing is often collaborative, and the members of a workgroup and their supervisors often critique group members’ work and offer feedback that will lead to a better final product.

Exchange essays with a classmate and complete a peer review of each other’s draft in progress. Remember to give positive feedback and to be courteous and polite in your responses. Focus on providing one positive comment and one question for more information to the author.

Using Feedback Objectively

The purpose of peer feedback is to receive constructive criticism of your essay. Your peer reviewer is your first real audience, and you have the opportunity to learn what confuses and delights a reader so that you can improve your work before sharing the final draft with a wider audience (or your intended audience).

It may not be necessary to incorporate every recommendation your peer reviewer makes. However, if you start to observe a pattern in the responses you receive from peer reviewers, you might want to take that feedback into consideration in future assignments. For example, if you read consistent comments about a need for more research, then you may want to consider including more research in future assignments.

Using Feedback from Multiple Sources

You might get feedback from more than one reader as you share different stages of your revised draft. In this situation, you may receive feedback from readers who do not understand the assignment or who lack your involvement with and enthusiasm for it.

You need to evaluate the responses you receive according to two important criteria:

- Determine if the feedback supports the purpose of the assignment.

- Determine if the suggested revisions are appropriate to the audience.

Then, using these standards, accept or reject revision feedback.

Work with two partners. Go back to Note 8.81 “Exercise 4” in this lesson and compare your responses to Activity A, about Mariah’s paragraph, with your partners’. Recall Mariah’s purpose for writing and her audience. Then, working individually, list where you agree and where you disagree about revision needs.

Editing Your Draft

If you have been incorporating each set of revisions as Mariah has, you have produced multiple drafts of your writing. So far, all your changes have been content changes. Perhaps with the help of peer feedback, you have made sure that you sufficiently supported your ideas. You have checked for problems with unity and coherence. You have examined your essay for word choice, revising to cut unnecessary words and to replace weak wording with specific and appropriate wording.

The next step after revising the content is editing. When you edit, you examine the surface features of your text. You examine your spelling, grammar, usage, and punctuation. You also make sure you use the proper format when creating your finished assignment.

Editing often takes time. Budgeting time into the writing process allows you to complete additional edits after revising. Editing and proofreading your writing helps you create a finished work that represents your best efforts. Here are a few more tips to remember about your readers:

- Readers do not notice correct spelling, but they do notice misspellings.

- Readers look past your sentences to get to your ideas—unless the sentences are awkward, poorly constructed, and frustrating to read.

- Readers notice when every sentence has the same rhythm as every other sentence, with no variety.

- Readers do not cheer when you use there , their , and they’re correctly, but they notice when you do not.

- Readers will notice the care with which you handled your assignment and your attention to detail in the delivery of an error-free document..

The first section of this book offers a useful review of grammar, mechanics, and usage. Use it to help you eliminate major errors in your writing and refine your understanding of the conventions of language. Do not hesitate to ask for help, too, from peer tutors in your academic department or in the college’s writing lab. In the meantime, use the checklist to help you edit your writing.

Editing Your Writing

- Are some sentences actually sentence fragments?

- Are some sentences run-on sentences? How can I correct them?

- Do some sentences need conjunctions between independent clauses?

- Does every verb agree with its subject?

- Is every verb in the correct tense?

- Are tense forms, especially for irregular verbs, written correctly?

- Have I used subject, object, and possessive personal pronouns correctly?

- Have I used who and whom correctly?

- Is the antecedent of every pronoun clear?

- Do all personal pronouns agree with their antecedents?

- Have I used the correct comparative and superlative forms of adjectives and adverbs?

- Is it clear which word a participial phrase modifies, or is it a dangling modifier?

Sentence Structure

- Are all my sentences simple sentences, or do I vary my sentence structure?

- Have I chosen the best coordinating or subordinating conjunctions to join clauses?

- Have I created long, overpacked sentences that should be shortened for clarity?

- Do I see any mistakes in parallel structure?

Punctuation

- Does every sentence end with the correct end punctuation?

- Can I justify the use of every exclamation point?

- Have I used apostrophes correctly to write all singular and plural possessive forms?

- Have I used quotation marks correctly?

Mechanics and Usage

- Can I find any spelling errors? How can I correct them?

- Have I used capital letters where they are needed?

- Have I written abbreviations, where allowed, correctly?

- Can I find any errors in the use of commonly confused words, such as to / too / two ?

Be careful about relying too much on spelling checkers and grammar checkers. A spelling checker cannot recognize that you meant to write principle but wrote principal instead. A grammar checker often queries constructions that are perfectly correct. The program does not understand your meaning; it makes its check against a general set of formulas that might not apply in each instance. If you use a grammar checker, accept the suggestions that make sense, but consider why the suggestions came up.

Proofreading requires patience; it is very easy to read past a mistake. Set your paper aside for at least a few hours, if not a day or more, so your mind will rest. Some professional proofreaders read a text backward so they can concentrate on spelling and punctuation. Another helpful technique is to slowly read a paper aloud, paying attention to every word, letter, and punctuation mark.

If you need additional proofreading help, ask a reliable friend, a classmate, or a peer tutor to make a final pass on your paper to look for anything you missed.

Remember to use proper format when creating your finished assignment. Sometimes an instructor, a department, or a college will require students to follow specific instructions on titles, margins, page numbers, or the location of the writer’s name. These requirements may be more detailed and rigid for research projects and term papers, which often observe the American Psychological Association (APA) or Modern Language Association (MLA) style guides, especially when citations of sources are included.

To ensure the format is correct and follows any specific instructions, make a final check before you submit an assignment.

With the help of the checklist, edit and proofread your essay.

Key Takeaways

- Revising and editing are the stages of the writing process in which you improve your work before producing a final draft.

- During revising, you add, cut, move, or change information in order to improve content.

- During editing, you take a second look at the words and sentences you used to express your ideas and fix any problems in grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure.

- Unity in writing means that all the ideas in each paragraph and in the entire essay clearly belong together and are arranged in an order that makes logical sense.

- Coherence in writing means that the writer’s wording clearly indicates how one idea leads to another within a paragraph and between paragraphs.

- Transitional words and phrases effectively make writing more coherent.

- Writing should be clear and concise, with no unnecessary words.

- Effective formal writing uses specific, appropriate words and avoids slang, contractions, clichés, and overly general words.

- Peer reviews, done properly, can give writers objective feedback about their writing. It is the writer’s responsibility to evaluate the results of peer reviews and incorporate only useful feedback.

- Remember to budget time for careful editing and proofreading. Use all available resources, including editing checklists, peer editing, and your institution’s writing lab, to improve your editing skills.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Revising Drafts

Rewriting is the essence of writing well—where the game is won or lost. —William Zinsser

What this handout is about

This handout will motivate you to revise your drafts and give you strategies to revise effectively.

What does it mean to revise?

Revision literally means to “see again,” to look at something from a fresh, critical perspective. It is an ongoing process of rethinking the paper: reconsidering your arguments, reviewing your evidence, refining your purpose, reorganizing your presentation, reviving stale prose.

But I thought revision was just fixing the commas and spelling

Nope. That’s called proofreading. It’s an important step before turning your paper in, but if your ideas are predictable, your thesis is weak, and your organization is a mess, then proofreading will just be putting a band-aid on a bullet wound. When you finish revising, that’s the time to proofread. For more information on the subject, see our handout on proofreading .

How about if I just reword things: look for better words, avoid repetition, etc.? Is that revision?

Well, that’s a part of revision called editing. It’s another important final step in polishing your work. But if you haven’t thought through your ideas, then rephrasing them won’t make any difference.

Why is revision important?

Writing is a process of discovery, and you don’t always produce your best stuff when you first get started. So revision is a chance for you to look critically at what you have written to see:

- if it’s really worth saying,

- if it says what you wanted to say, and

- if a reader will understand what you’re saying.

The process

What steps should i use when i begin to revise.

Here are several things to do. But don’t try them all at one time. Instead, focus on two or three main areas during each revision session:

- Wait awhile after you’ve finished a draft before looking at it again. The Roman poet Horace thought one should wait nine years, but that’s a bit much. A day—a few hours even—will work. When you do return to the draft, be honest with yourself, and don’t be lazy. Ask yourself what you really think about the paper.

- As The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers puts it, “THINK BIG, don’t tinker” (61). At this stage, you should be concerned with the large issues in the paper, not the commas.

- Check the focus of the paper: Is it appropriate to the assignment? Is the topic too big or too narrow? Do you stay on track through the entire paper?

- Think honestly about your thesis: Do you still agree with it? Should it be modified in light of something you discovered as you wrote the paper? Does it make a sophisticated, provocative point, or does it just say what anyone could say if given the same topic? Does your thesis generalize instead of taking a specific position? Should it be changed altogether? For more information visit our handout on thesis statements .

- Think about your purpose in writing: Does your introduction state clearly what you intend to do? Will your aims be clear to your readers?

What are some other steps I should consider in later stages of the revision process?

- Examine the balance within your paper: Are some parts out of proportion with others? Do you spend too much time on one trivial point and neglect a more important point? Do you give lots of detail early on and then let your points get thinner by the end?

- Check that you have kept your promises to your readers: Does your paper follow through on what the thesis promises? Do you support all the claims in your thesis? Are the tone and formality of the language appropriate for your audience?

- Check the organization: Does your paper follow a pattern that makes sense? Do the transitions move your readers smoothly from one point to the next? Do the topic sentences of each paragraph appropriately introduce what that paragraph is about? Would your paper work better if you moved some things around? For more information visit our handout on reorganizing drafts.

- Check your information: Are all your facts accurate? Are any of your statements misleading? Have you provided enough detail to satisfy readers’ curiosity? Have you cited all your information appropriately?

- Check your conclusion: Does the last paragraph tie the paper together smoothly and end on a stimulating note, or does the paper just die a slow, redundant, lame, or abrupt death?

Whoa! I thought I could just revise in a few minutes

Sorry. You may want to start working on your next paper early so that you have plenty of time for revising. That way you can give yourself some time to come back to look at what you’ve written with a fresh pair of eyes. It’s amazing how something that sounded brilliant the moment you wrote it can prove to be less-than-brilliant when you give it a chance to incubate.

But I don’t want to rewrite my whole paper!

Revision doesn’t necessarily mean rewriting the whole paper. Sometimes it means revising the thesis to match what you’ve discovered while writing. Sometimes it means coming up with stronger arguments to defend your position, or coming up with more vivid examples to illustrate your points. Sometimes it means shifting the order of your paper to help the reader follow your argument, or to change the emphasis of your points. Sometimes it means adding or deleting material for balance or emphasis. And then, sadly, sometimes revision does mean trashing your first draft and starting from scratch. Better that than having the teacher trash your final paper.

But I work so hard on what I write that I can’t afford to throw any of it away

If you want to be a polished writer, then you will eventually find out that you can’t afford NOT to throw stuff away. As writers, we often produce lots of material that needs to be tossed. The idea or metaphor or paragraph that I think is most wonderful and brilliant is often the very thing that confuses my reader or ruins the tone of my piece or interrupts the flow of my argument.Writers must be willing to sacrifice their favorite bits of writing for the good of the piece as a whole. In order to trim things down, though, you first have to have plenty of material on the page. One trick is not to hinder yourself while you are composing the first draft because the more you produce, the more you will have to work with when cutting time comes.

But sometimes I revise as I go

That’s OK. Since writing is a circular process, you don’t do everything in some specific order. Sometimes you write something and then tinker with it before moving on. But be warned: there are two potential problems with revising as you go. One is that if you revise only as you go along, you never get to think of the big picture. The key is still to give yourself enough time to look at the essay as a whole once you’ve finished. Another danger to revising as you go is that you may short-circuit your creativity. If you spend too much time tinkering with what is on the page, you may lose some of what hasn’t yet made it to the page. Here’s a tip: Don’t proofread as you go. You may waste time correcting the commas in a sentence that may end up being cut anyway.

How do I go about the process of revising? Any tips?

- Work from a printed copy; it’s easier on the eyes. Also, problems that seem invisible on the screen somehow tend to show up better on paper.

- Another tip is to read the paper out loud. That’s one way to see how well things flow.

- Remember all those questions listed above? Don’t try to tackle all of them in one draft. Pick a few “agendas” for each draft so that you won’t go mad trying to see, all at once, if you’ve done everything.

- Ask lots of questions and don’t flinch from answering them truthfully. For example, ask if there are opposing viewpoints that you haven’t considered yet.

Whenever I revise, I just make things worse. I do my best work without revising

That’s a common misconception that sometimes arises from fear, sometimes from laziness. The truth is, though, that except for those rare moments of inspiration or genius when the perfect ideas expressed in the perfect words in the perfect order flow gracefully and effortlessly from the mind, all experienced writers revise their work. I wrote six drafts of this handout. Hemingway rewrote the last page of A Farewell to Arms thirty-nine times. If you’re still not convinced, re-read some of your old papers. How do they sound now? What would you revise if you had a chance?

What can get in the way of good revision strategies?

Don’t fall in love with what you have written. If you do, you will be hesitant to change it even if you know it’s not great. Start out with a working thesis, and don’t act like you’re married to it. Instead, act like you’re dating it, seeing if you’re compatible, finding out what it’s like from day to day. If a better thesis comes along, let go of the old one. Also, don’t think of revision as just rewording. It is a chance to look at the entire paper, not just isolated words and sentences.

What happens if I find that I no longer agree with my own point?

If you take revision seriously, sometimes the process will lead you to questions you cannot answer, objections or exceptions to your thesis, cases that don’t fit, loose ends or contradictions that just won’t go away. If this happens (and it will if you think long enough), then you have several choices. You could choose to ignore the loose ends and hope your reader doesn’t notice them, but that’s risky. You could change your thesis completely to fit your new understanding of the issue, or you could adjust your thesis slightly to accommodate the new ideas. Or you could simply acknowledge the contradictions and show why your main point still holds up in spite of them. Most readers know there are no easy answers, so they may be annoyed if you give them a thesis and try to claim that it is always true with no exceptions no matter what.

How do I get really good at revising?

The same way you get really good at golf, piano, or a video game—do it often. Take revision seriously, be disciplined, and set high standards for yourself. Here are three more tips:

- The more you produce, the more you can cut.

- The more you can imagine yourself as a reader looking at this for the first time, the easier it will be to spot potential problems.

- The more you demand of yourself in terms of clarity and elegance, the more clear and elegant your writing will be.

How do I revise at the sentence level?

Read your paper out loud, sentence by sentence, and follow Peter Elbow’s advice: “Look for places where you stumble or get lost in the middle of a sentence. These are obvious awkwardness’s that need fixing. Look for places where you get distracted or even bored—where you cannot concentrate. These are places where you probably lost focus or concentration in your writing. Cut through the extra words or vagueness or digression; get back to the energy. Listen even for the tiniest jerk or stumble in your reading, the tiniest lessening of your energy or focus or concentration as you say the words . . . A sentence should be alive” (Writing with Power 135).

Practical advice for ensuring that your sentences are alive:

- Use forceful verbs—replace long verb phrases with a more specific verb. For example, replace “She argues for the importance of the idea” with “She defends the idea.”

- Look for places where you’ve used the same word or phrase twice or more in consecutive sentences and look for alternative ways to say the same thing OR for ways to combine the two sentences.

- Cut as many prepositional phrases as you can without losing your meaning. For instance, the following sentence, “There are several examples of the issue of integrity in Huck Finn,” would be much better this way, “Huck Finn repeatedly addresses the issue of integrity.”

- Check your sentence variety. If more than two sentences in a row start the same way (with a subject followed by a verb, for example), then try using a different sentence pattern.

- Aim for precision in word choice. Don’t settle for the best word you can think of at the moment—use a thesaurus (along with a dictionary) to search for the word that says exactly what you want to say.

- Look for sentences that start with “It is” or “There are” and see if you can revise them to be more active and engaging.

- For more information, please visit our handouts on word choice and style .

How can technology help?

Need some help revising? Take advantage of the revision and versioning features available in modern word processors.

Track your changes. Most word processors and writing tools include a feature that allows you to keep your changes visible until you’re ready to accept them. Using “Track Changes” mode in Word or “Suggesting” mode in Google Docs, for example, allows you to make changes without committing to them.

Compare drafts. Tools that allow you to compare multiple drafts give you the chance to visually track changes over time. Try “File History” or “Compare Documents” modes in Google Doc, Word, and Scrivener to retrieve old drafts, identify changes you’ve made over time, or help you keep a bigger picture in mind as you revise.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Elbow, Peter. 1998. Writing With Power: Techniques for Mastering the Writing Process . New York: Oxford University Press.

Lanham, Richard A. 2006. Revising Prose , 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

Zinsser, William. 2001. On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction , 6th ed. New York: Quill.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Revision -- the process of revisiting, rethinking, and refining written work to improve its content , clarity and overall effectiveness -- is such an important part of the writing process that experienced writers often say "writing is revision." This article reviews research and theory on what revision is and why it's so important to writers. Case studies , writing protocols, and interviews of writers at work have found that revision is guided by inchoate, preverbal feelings and intuition--what Sondra Perl calls " felt sense "; by reasoning and openness to strategic searching , counterarguments , audience awareness , and critique ; and by knowledge of discourse conventions , such as mastery of standard written English , genre , citation , and the stylistic expectations of academic writing or professional writing . Understanding revision processes can help you become a more skilled and confident writer--and thinker.

Synonyms – Related Terms

In workplace and school settings , people use a variety of terms to describe revision or the act of revising , including

- a high-level review

- a global review

- a substantive rewrite

- a major rewrite

- Slashing and Throwing Out

On occasion, students or inexperienced writers may conflate revision with editing and proofreading . However, subject matter experts in writing studies do not use these terms interchangeably. Rather, they distinguish these intellectual strategies by noting their different foci:

a focus on the global perspective :

- audience awareness

- purpose & organization (e.g., What’s my thesis ?)

- invention , especially content development

- Content Development

- Organization

- Rhetorical Stance

a focus on the local perspective

- Inclusivity

Proofreading

a focus on a last chance to catch any errors , such as

- Modification

- Comma Splice

- Run-on Sentences

- Sentence Fragment

- Subject-Verb Agreement

Related Concepts: Academic Writing Prose Style ; Authority (in Speech and Writing) ; Critical Literacy ; Interpretation, Interpretative Frameworks ; Professional Writing Prose Style ; Rhetorical Analysis

The only kind of writing is rewriting Earnest Hemingway

What is Revision?

1. revision refers to a critical step in the writing process.

Typically, the act of writing – the act of composing – isn’t a process of translating what’s already perfectly formed in one’s mind. Instead, most people need to engage in revision to determine what they need to say and how they need to say it. In other words, unlike editing, which is focused on conforming to standard written English and other discourse conventions, revision is an act of invention and critical reasoning.

In writing studies , revision refers to one of the four most important steps in the writing process . While there are many models of composing, the writing process is often described as having four steps:

- writing, which is also known as drafting or composing

Case studies and interviews of writers @ work offer overwhelming evidence that revision is a major preoccupation of writers during composing . When revising , writers pause to reread what they’ve written and they engage in critique of their own work. Meaning finds form in language when writers engage in critical dialogue with their texts .

Research has found that experienced writers tend to revise their work more frequently and extensively than inexperienced student writers (Beason, 1993; Graham & Perin, 2007; Hayes et al., 1987; Patchan et al., 2011; Strobl, 2019). For example, James Hall, an experienced poet, reported revising his poems over two hundred times, whereas James Michener, an accomplished novelist, rewrote his work six or seven times (Beason, 1993).

2. Revision refers to an act of metamorphosis

Just as a caterpillar undergoes metamorphosis to become a butterfly, revision allows a written work to evolve and reach its full potential. For writers , revision is an act of discovery. It’s a recursive process that empowers writers to discover what they want to say:

- “Writing and rewriting are a constant search for what one is saying.” — John Updike

- “How do I know what I think until I see what I say.” — E.M. Forster

From an empirical perspective, this idea that revision is a metamorphic process can be traced back to Nancy Sommers’ (1980) research on the revision strategies of twenty student writers enrolled at Boston University or the University of Oklahoma and twenty professional writers. Using case study and textual research methods , Sommers found that students tended to view revision to be an act of rewording for brevity as opposed to making semantic changes:

“The aim of revision according to the students’ own description is therefore to clean up speech; the redundancy of speech is unnecessary in writing, their logic suggests, because writing, unlike speech, can be reread. Thus one student said, “Redoing means cleaning up the paper and crossing out…When revising, they primarily ask themselves: can I find a better word or phrase? A more impressive, not so cliched, or less hum-drum word? Am I repeating the same word or phrase too often? They approach the revision process with what could be labeled as a “thesaurus philosophy of writing” (p. 382)

In contrast, Sommers found that experienced writers perceive the revision process to be an act of discovery, “…a repeated process of beginning over again, starting out new-that the students failed to have” (p. 387). Rather than being focused on diction or word-level errors, they question the unity and rhetoricity (particular audience awareness) of their texts.

By comparing the writing processes of students and experienced writers, Sommers change the conversation in writing studies regarding what revision is and how it should be taught. Since then, numerous other studies have supported her contention that that revision should be viewed as a recursive and evolving process rather than a linear sequence of corrections. For example, more recently, Smith and Brown (2020) conducted a study on the metamorphic nature of revision by examining its transformative effects on the quality of written work. They posited that viewing revision as an act of metamorphosis allows writers to experience a sense of renewal, thus leading to improved writing. Their findings revealed that participants who embraced the metamorphic perspective produced texts with greater clarity , coherence, unity , and depth compared to those who approached revision as mere editing .

In a related study, Johnson et al. (2021) explored the psychological aspects of viewing revision as metamorphosis. They observed that participants who considered revision as a process of transformation exhibited enhanced motivation, creativity, and willingness to experiment with new ideas. This research underscores the importance of mindset in shaping the revision process and suggests that embracing a metamorphic perspective may foster positive attitudes toward revision.

To become a butterfly, a caterpillar has to pupa has to melt its body to soup, becoming something entirely different. Similarly, revision is much more than editing a text so that it meets the conventions of standard written English . Instead, revision is a metamorphosis –it’s a transformative process.

- Similar to how a caterpillar molts and grows, writers must be willing to let go of prior drafts and beliefs. They need to adopt a growth mindset and be open to strategic searching , counterarguments , and critique .

- The metamorphosis of a butterfly is not an instantaneous event, nor is the process of revision. As Hayes and Flower (1986) argue, the act of revision requires time to reflect, analyze, and implement changes. Writers who embrace this temporal dimension are better equipped to guide their work through its transformative journey.

- During metamorphosis, a caterpillar undergoes significant physiological changes. In a similar vein, revision can catalyze psychological shifts in a writer’s mindset (Rogers, 2019). By embracing vulnerability and recognizing the value of constructive criticism, writers can develop a more resilient and growth-oriented mindset.

3. Revision refers to an intuitive, creative, and nonlinguistic practices

Traditionally, revision has been viewed as a primarily linguistic endeavor, focused on the correction of grammar , syntax , and style . However, recent scholarship has shed light on the importance of considering revision as an intuitive, creative, and nonlinguistic practice.

Interviews and case studies of writers @ work repeatedly illustrate that writers perceive revision to be an artistic, creative process that is deeply shaped by inchoate, preverbal feelings and intuition. In “Understanding Composing,” Sondra Sondra Perl , a professor of English and subject matter expert in Writing Studies , theorizes that writers, speakers, and knowledge workers begin writing only after they have a felt sense of what they want to say:

“When writers are given a topic , the topic itself evokes a felt sense in them. This topic calls forth images, words, ideas, and vague fuzzy feelings that are anchored in the writer’s body. What is elicited, then, is not solely the product of a mind but of a mind alive in a living, sensing body” (p. 365).

Felt sense refers to a preverbal, holistic understanding of a subject or issue that emerges from an individual’s bodily sensations and experiences. Perl argues that tapping into this felt sense can guide writers through the revision process, leading to deeper insights and more authentic expression. By attending to their felt sense , writers can access a rich source of information that might otherwise remain unexplored, resulting in more engaging and meaningful writing.

More specifically, Perl observed that when writers reread little bits of discourse they often return to “some key word or item called up by the topic” (365) and that they return “to feelings or nonverbalized perceptions that surround the words, or to what the words already present evoke in the writer” (365). While comparing this activity, which she labels “felt sense” to Vygotsky’s conception of “inner speech” or the feeling of “inspiration.” Perl suggests that writers listen “to one’s inner reflections . . . and bodily sensations . . . . There is less a ‘figuring out’ an answer and more ‘waiting’ to see what forms . . . Once a felt sense forms, we match words to it” (366-67)

Strategies for Incorporating Intuitive, Creative, Nonlinguistic Practices in Revision

- Practice engaging with your felt sense by paying attention to your bodily sensations and intuition during the writing process. This can help you access your inner wisdom and creativity, resulting in more authentic and meaningful writing.

- Use visual language — diagrams, sketches, data visualizations — to visually represent the structure and organization of your written work. This can help you identify potential areas for improvement and enhance the coherence of your text.

- Employ metaphors to facilitate creative problem-solving and deepen your understanding of complex concepts. This can enrich your writing and promote the development of original ideas.

- Engage in brainstorming sessions to generate new ideas and perspectives on your topic. This can lead to the discovery of innovative solutions and foster greater creativity in your writing.

- Practice reflective writing to develop a deeper understanding of your thought processes, feelings, and motivations. This can help you identify areas for growth and improvement in your writing.

4. Revision refers to the process of engaging in critical thinking and reasoning to review, rethink and revise a written work.

When engaging in the process of revision , writers employ critical thinking and reasoning skills to analyze their work and to make necessary changes to improve its clarity and overall quality. Writers engage in rhetorical reasoning , which involves analyzing their work from an audience perspective . This process enables them to evaluate the appropriateness of their tone , voice and persona . They also engage in rhetorical reasoning to assess whether they have accounted for their audience’s expectations regarding the preferred writing style:

- Academic Writing Prose Style

- Professional Writing – Professional Writing Prose Style

Writers also use logic to evaluate the coherence and flow of their arguments , ensuring that their ideas are well developed and presented in a clear and organized manner .

Why Does Revision Matter?

Rewriting is the essence of writing well: it’s where the game is won or lost William Zinsser (2006)

1. Revision is an extremely important part of the writing process

Revision is an essential step in the writing process . Revision is so important to achieving brevity , clarity , flow , inclusivity , simplicity , and unity that writers often spend a huge amount of time revising. This is why Donald Murray once quipped that “writing is revising”:

“Writing is revising, and the writer’s craft is largely a matter of knowing how to discover what you have to say, develop, and clarify it, each requiring the craft of revision” (Murray 2003, p. 24).

Writers in both workplace and school contexts may revise a document twenty, thirty, even fifty times before submitting it for publication.

- “ To rewrite ten times is not unusual. Oh, bother the mess, mark them as much as you like; what else are they for? Mark everything that strikes you. I may consider a thing forty-nine times; but if you consider it, it will be considered 50 times, and a line 50 times considered is 2 percent better than a line 49 times considered. And it is the final 2 percent that makes the difference between excellence and mediocrity. ” — George Bernard Shaw

- “lt’s always taken me a long time to finish poems. When I was in my twenties I found poems taking six months to a year, maybe fifty drafts or so. Now I am going over two hundred drafts regularly, working on things four or five years and longer; too long! I wish I did not take so long.” — James Hall

- “ Getting words on paper is difficult. Nothing I write is good enough in the first draft, not even personal letters. Important work must be written over and over—up to six or seven times.” — James Michener

2. Revision improves the quality of writing

Revision empowers writers to improve the clarity of their communications . Research by Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981), Sommers (1980) and Faigley and Witte (1981) highlights how revision allows writers to rethink and refine their style , leading to clearer , more concise , engaging writing.

3. Revision encourages critical thinking

Revising a piece of writing requires the writer to evaluate their own work and make decisions about its rhetoricity (especially audience awareness ), content , and style . Revision involves engaging in critical analysis — what experts in writing studies call rhetorical analysis — This process encourages critical thinking, as it pushes writers to assess the effectiveness of their arguments, consider counterarguments , and adapt their work to better meet the needs of their audience. Engaging in this level of critical analysis will help you become a more thoughtful and persuasive writer.

4. Revision helps writers establish a consistent and appropriate voice, tone, persona, and style

Writers engage in revision to establish a consistent and appropriate voice , tone , and persona . Through multiple revisions, writers can experiment with different personas , voices and tones to create a more engaging and coherent piece (Elbow, 1999). More recently, Fitzgerald and Ianetta (2016) explored the connection between revision and the development of an authentic writer’s persona. Their research suggested that engaging in revision encourages writers to reflect on their own voice and perspective , leading to the creation of a more genuine and relatable persona . This process helps writers maintain a consistent tone and style throughout their work, ultimately improving the overall quality of their text .

Review of Helpful Guides to Revision @ Writing Commons

As discussed above, revision is an act of both reasoning and intuition. Thus, there’s no single recipe for engaging in revision processes. Different rhetorical situations will call for different composing strategies. Even so, there are consistent, major intellectual processes that professional writers use to bring their rough drafts to fruition.

Revision Strategies – How to Revise

Written by Joseph M. Moxley , this guide to revision is based on research and scholarship in writing studies , especially qualitative interviews and case studies of writers @ work .This essay outlines a five-step approach to revising a document:

- Engage in rhetorical reasoning regarding the communication situation

- Inspect the Document @ the Global Level

- Inspect the Document @ the Section Level

- Inspect the Document at the Paragraph Level

- Inspect the Document at the Sentence Level

Working Through Revision: Rethink, Revise, Reflect

Written by Megan McIntyre , the Director of Rhetoric at the University of Arkansas, this articple provides a 5-step approach to developing a revision plan and working with a teacher to improve a draft:

- Ask for Feedback

- Interpret Feedback

- Translate Feedback into a Concrete Revision Plan

- Make Changes

- Reflect on the Change You’ve Made

FAQs on Revision

Revision refers to the process of critically evaluating and refining a written text by making changes to its content , organization , style , and clarity to improve its overall quality and effectiveness. A step in the writing process , revision refers to writers’ use of creative, intuitive processes and critical, cognitive processes to refine their understanding of what they want to say and how they want to say it .

Why is Revision Important?

Revision is important because it allows writers to enhance the clarity and coherence of their work, refine their ideas, and improve overall text quality, leading to more effective communication and better reader engagement (Hayes & Flower, 1980; Sommers, 1980).

When Do Writers Revise?

When facing an exigency, a call to write , most people need to revise a message multiple times before it says what they want it to say and says it in a way that they feel is most appropriate given the rhetorical situation , especially the target audience .

What determines how many times a writer needs to revise a text?

There are many factors that effect how many revisions you may need to give to a document, such as

- the importance and/or the complexity of the topic

- the amount of time you have to complete the text

- your interest in the topic

Should R evision, Editing, and Proofreading be Separate Processes that Are Completed Sequentially?

Writers may engage in revising , editing , and proofreading processes all at the same time, especially when under deadline. However, in general practice writers first revise, then edit , and finally proofread . The problem with mixing editing or proofreading into revision processes is that you may end up editing a paragraph for brevity , simplicity , clarity , and unity and then later decide the whole thing needs to be scratched because the audience already knows about that information .

What Does a Teacher Mean by Revision?

When teachers ask you to revise a text, that means they want a major revision. They want you to do much more than change a few words around or fix the edits they’ve marked. A major revision goes beyond editing : When writers are engaged in a substantive revision, that means everything is possible–even the idea of trashing the entire document and starting all over again.

Berthoff, A. E. (1981). The making of meaning: Metaphors, models, and maxims for writing teachers. Boynton/Cook Publishers.

Elbow, P. (1999). Everyone Can Write: Essays Toward a Hopeful Theory of Writing and Teaching Writing. Oxford University Press.

Faigley, L., & Witte, S. (1981). Analyzing Revision. College Composition and Communication, 32(4), 400-414.

Fitzgerald, J., & Ianetta, M. (2016). The Oxford guide for writing tutors: Practice and research. Oxford University Press.

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981). A Cognitive Process Theory of Writing. College Composition and Communication, 32(4), 365-387.

Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools. Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Johnson, T., Parker, S., & Yang, X. (2021). The psychological impact of viewing revision as metamorphosis: A study on motivation and creativity in writing. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(4), 875-894.

Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. S. (1980). Identifying the organization of writing processes. In L. W. Gregg & E. R. Steinberg (Eds.), Cognitive processes in writing (pp. 3-30). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hemingway, E. (2000). A moveable feast. Vintage Classics.

Murray, D. (2003). The craft of revision (5th ed.). Wadsworth.

Patchan, M. M., Schunn, C. D., & Clark, R. J. (2011). Writing in natural sciences: Understanding the effects of different types of reviewers on the writing quality of preservice teachers. Journal of Writing Research, 3(2), 141-166.

Smith, J., & Brown, L. (2020). Revision as metamorphosis: A new perspective on the transformative potential of re-examining written work. Composition Studies, 48(2), 45-62.

Sommers, N. (1980). Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers. College Composition and Communication, 31(4), 378-388.

Strobl, C. (2019). Effects of process-oriented writing instruction on the quality of EFL learners’ argumentative essays. Journal of Second Language Writing, 44, 1-1

Zinsser, W. (2006). On writing well (30th ed.). HarperCollins.

Related Articles:

Revise for a more effective point of view, revise for substantive prose, revise for thesis or research question.

Structured Revision - How to Revise Your Work

Suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Jenifer Paquette , Joseph M. Moxley

- Joseph M. Moxley , Julie Staggers

Learn how to revise your writing in a strategic, professional manner Use structured revision practices to revise your work in a strategic, professional manner. Learn about why structured revision is...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

Writing Studio

What is revision.

In an effort to make our handouts more accessible, we have begun converting our PDF handouts to web pages. Download this page as a PDF: Revision handout PDF Return to Writing Studio Handouts

Revision is not merely proofreading or editing an essay. Proofreading involves making minor changes, such as putting a comma here, changing a word there, deleting part of a sentence, and so on. Revision, on the other hand, involves making more substantial changes.

Literally, it means re-seeing what you have written in order to re-examine (and possibly change and develop) what you have said or how you have said it. One might revise the argument, organization, style, or tone of one’s paper.

Below you’ll find some helpful activities to help you begin to think through and plan out revisions.

Revision Strategies

Memory draft.

Set aside what you’ve written and rewrite your essay from memory. Compare the draft of your paper to your memory draft. Does your original draft clearly reflect what you want to argue? Do you need to modify the thesis? Should you reorganize parts of your paper?

This technique helps point out what you think you are doing in comparison to what you are actually doing in a piece of writing.

Reverse Outline

Some writers find it helpful to make an outline before writing. A reverse outline, which one makes after writing a draft, can help you determine whether your paper should be reorganized. To make a reverse outline and use it to revise your paper: Read through your paper, making notes in the margins about the main point of each paragraph.

Create your reverse outline by writing those notes down on a separate piece of paper. Use your outline to do three things:

- See whether each paragraph plays a role in supporting your thesis.

- Look for unnecessary repetition of ideas.

- Compare your reverse outline with your draft to see whether the sentences in each paragraph are related to the main point of that paragraph, per the reverse outline. This technique is helpful in reconsidering the organization and coherence of an essay. By figuring out what each paragraph contributes to your paper, you will be able to see where each fits best within it.

Anatomy of a Paragraph

Select different colored highlighters to represent the different elements that should be found in an argumentative essay. Make a key somewhere on the first page, noting what each color represents. You might consider attributing a color to thesis, argumentative topic sentence, evidence, analysis, and fluffy flimflam. Now, color code your essay. When you’re finished, diagnose what you see, paying attention to where you’ve placed your topic sentences, whether you’re using enough evidence, and whether you could expand or streamline your analysis.

This strategy is helpful for visual learners and authors who feel overwhelmed by the length of their draft or scope of their revision project. It also helps to illustrate the organization and development of an argument.

Unpacking an Idea

Select a certain paragraph in your essay and try to explain in more detail how the concepts or ideas fit together. Unpack the evidence for your claims by showing how it supports your topic sentence, main idea, or thesis.

This technique will help you more deliberately explain the steps in your reasoning and point out where any gaps may have occurred within it. It will help you establish how these reasons, in turn, lead to your conclusions.