The loneliness of being mixed race in America

“I had to figure out the language to describe myself”: 6 mixed-race people on shifting how they identify.

by Vox First Person

This is part one of Vox First Person’s exploration of multiracial identity in America. Read part two here and part three here .

In 1993, the cover of Time bore a digitally rendered face, a supposed “mix of several races” that created a lightly tinted brown-skinned woman. “The New Face of America,” the headline proclaimed, heralded a future where interracial marriages held the promise of a raceless society of beige-colored people.

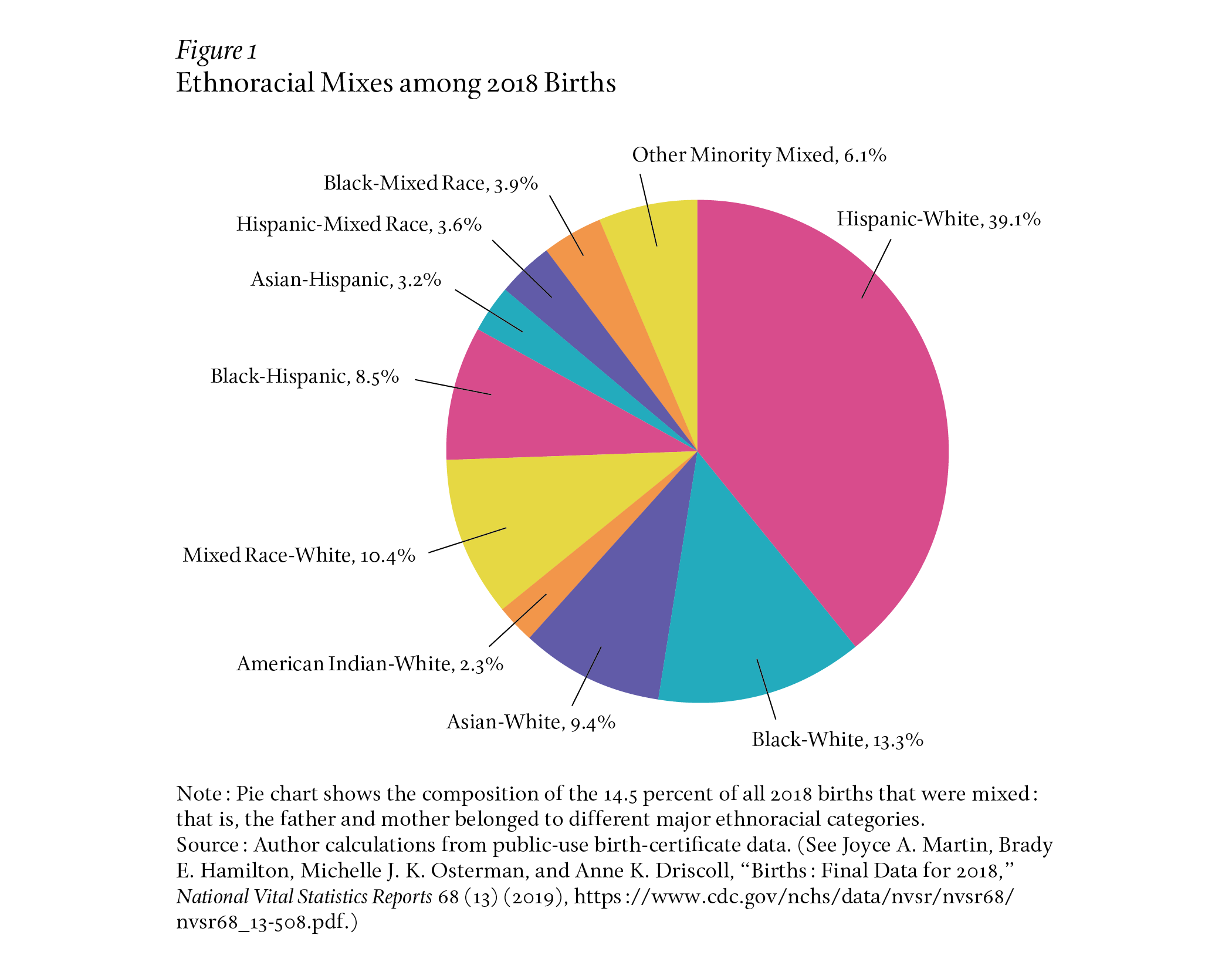

Almost 30 years later, the United States is getting ready to inaugurate its first female vice president, who is of Black and South Asian descent; the nation has already sworn in its first multiracial and Black president, Barack Obama. By 2013, 10 percent of all babies had parents who were different races from each other, and the number is only growing : In a 2015 Pew study, nearly half of all multiracial Americans were under 18 years old.

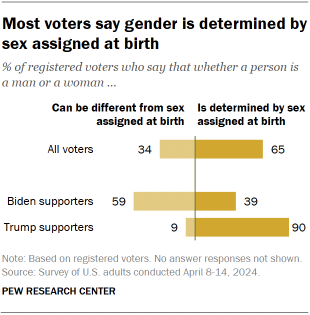

Demographically at least, Time’s cover story seems to have gotten it right. But inherent to their vision was a kind of multiracial utopia free of racial strife. This is a popular modern understanding of mixed-race identity. But multiracial people have long been targets of fear and confusion, from suspicions of mixed people “passing” as white under the Jim Crow system to accusations of not embracing one’s “race” enough — something Kamala Harris experienced on multiple sides this past election. Research has shown that, even today, monoracial people experience mixed people as more “cognitively demanding” than fellow monoracial people.

As the mixed population grows in size, it will likely continue to serve as projections for people to sort through America’s complex race relations. But what about the experiences of those who are actually multiracial? Studies illustrate a group of people who struggle with questions of identity and where to fit in, often feeling external pressures to “choose” a side. There’s evidence that mixed-race people have higher rates of mental health issues and substance abuse , too.

- On being “ethnically ambiguous”

As Black Lives Matter protests swept the country in 2020, the issue of race came to the forefront of the national conversation. Everywhere, Americans engaged in deep discussions around the experience of Black and other non-white people in our country, including how race impacts the daily lives of all Americans in unequal ways.

Last year, Vox asked people of mixed descent to tell us how they felt about race and if the language about their identities had shifted over time. Among the 70 responses submitted, we read stories of people with vastly different experiences depending on their racial makeup, how their parents raised them, where they lived and where they wound up living, and, perhaps most importantly, how they look. But over and over again, we heard from respondents that they frequently felt isolated, confused about their identity, and frustrated when others attempted to dole them out into specific boxes.

Here are six selected stories, edited for concision and length.

Michael Lahanas-Calderón, 24, based in Berkeley, California

I’ve found terms to identify myself that feel somewhat comfortable but also somewhat unsatisfying. I don’t really know how to account for my mother’s background, which at best could be described as mestizo Colombian. Using the term “person of color” to account for it feels strange, just given what I see when I look in the mirror. But I also feel a kind of obligation not to let the complex mix of identities I inherited from my mother disappear into the whiteness inherited from my father. I don’t really know where that leaves me, to be honest, beyond using broader terms like Latino, Colombian-American, white-passing, mixed, or multiracial.

Race didn’t come up a lot when I was growing up in suburban Ohio. Obviously, there was a Latino population there, but it wasn’t really a huge part of my life, beyond my mother in our home. It wasn’t like the way that Miami has the strong Cuban-American community. It was almost more an issue of whiteness and skin color being associated with some of those terms, which sort of changed the dynamic depending on the environment because I’m white-passing even with like a tan.

My mom went to great lengths to make sure that I could succeed in the US. When I was still quite little, my Spanish skills were actually developing at a better pace than my English ones. That is, until someone suggested to her that if my English skills didn’t improve, I would be at risk of falling behind the other kids and need speech therapy. This really spurred her to take serious action. She read countless books to me every night in English until I was a bookworm who sounded as Midwestern as the rest of my neighbors. To this day, out of all the things she remembers about my academic career, my high marks on English tests are some of the ones she’s proudest of. But I would be remiss if I did not mention the efforts of my mother to teach me about her and my identity, homeland, and culture, too. She always taught me to be fiercely proud of my blended heritage, and to never be afraid to share it with others.

At times it was pretty easy how well I had adjusted to suburban Ohio. I didn’t really think about the consequences of it until I was a little bit older, because it just got easier to not show that heritage. The shift away from that started in college, which was a much more progressive environment. I was sort of encouraged to explore that identity. We had a Latinx affinity group on campus and I think at times it was a little bit difficult for me to relate to others in the group. They were always welcoming, and it wasn’t that I didn’t feel included, but I think it was more that their experiences were so different from mine. The experience of being a Salvadoran American who is brown and grew up in, say, San Francisco with a pretty solid Latino community around them felt so wildly different from a white-passing, half-Colombian, half-American person growing up in suburban Ohio. We didn’t really have a lot in common beyond the shared language.

It’s always been important to me to recognize both parts of my heritage. But I suppose the only one that really felt like it needed exploring was my Colombian side, because I was always within the dominant side of mainstream American culture. I think that at times it almost felt easier, like everyone encourages you to kind of fall into that mainstream culture and assimilate. If you don’t have that kind of connection to a first-gen or community of immigrants who are actually actively forming a social group, it’s very easy to let one side of your heritage — the one that’s not the dominant culture — slip away. It’s kind of one of my regrets, to be honest, and I’ve made an effort as I’ve gotten older to embrace that again.

Abbey White, 29, based in Brooklyn, New York

Right now, and this may change, I identify as a mixed-race Black person. But initially, I identified as bi-racial. I felt like growing up in the environment that I was in, in Cleveland, it was very clear to me that I was Black and I was mixed, but when I moved to New York, that dramatically changed. I got a lot of people not really being able to recognize me on sight. I’ve had to deal with an ethnic ambiguity that I never had to deal with before. So I had to figure out the language that I wanted to use to describe myself.

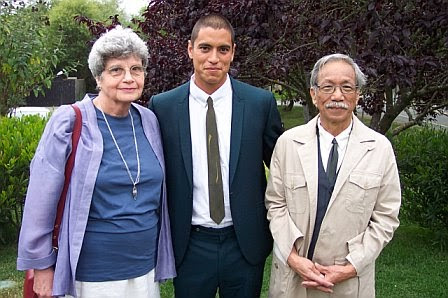

I think part of that stems from the fact that when I grew up, my dad, who is Black, wasn’t really in my life, so a lot of my Black identity came from the Black people that my mother worked with and the neighborhood that I lived in. But also, my family was so white and, frankly, for as much as I love my mother, racist. My grandfather would not be in the same room with her the entire nine months she was pregnant. He couldn’t even hold me for the first couple months of my life.

I sort of remember realizing my race when I was late elementary school age and I had gotten in trouble at my grandmother’s house. And I remember putting, like, baby powder on my skin and like trying to convince myself for whatever reason that I would not be as in trouble if I looked more like my mom.

I also felt this struggle to feel connected with Black people when I was growing up. I felt often like a conditional Black person, and I think there are some mixed-race Black folks that have a lot of anger about that. When I was younger, I did. But I’ve also come to understand that the idea of being “authentically” Black is literally a response to things like the one drop rule and this white supremacist idea of how we define race and mixed race, and Black identity being tied to sexual violence. So this reclamation of what it means to be Black is a byproduct of racism.

There are also privileges I have that other non-mixed Black people don’t. I am lighter-skinned. I might not be white-passing, but I can pass as something else. Because for some people, I’m “racially ambiguous,” what has happened is I have found myself in situations with white people who feel very comfortable saying things that are not okay. It’s this sort of, “you’re not like other girls.” Like my grandfather wouldn’t even be in the same room with my mom, but then once I came into this world and they realized, “oh, she’s a baby and race has nothing to do with this,” it wasn’t, “we see Black people as human beings and we respect them.” It became: “You’re our Black child. And you’re the exception to the rule. ”

It’s weird being in places with people who try to make you the exception to the rule, and it makes me want to double down. Because I’m not an exception. I think that that has really made me embrace this idea of I am Black. I’m mixed, but I’m Black.

Josh S., 24, based in Brooklyn, New York

I identify as multiracial. There hasn’t really been another term that’s resonated with me in the same way. I like breaking it down a little — my family is white, and then on my dad’s side, I have family in Japan. I think the change in identity from when I was younger is that I actually have the language to describe who I am, which I lacked back then. I only knew that I wasn’t wholly white, but that it was thrown into pretty sharp contrast because I grew up in a town that was like 99 percent white.

Being thought of as Asian was definitely foisted onto me. Because I did relatively well in school, there was a lot of like, “Oh, the Asian got a good math score.” There was something that felt off about that. Later I realized that, well, my race has absolutely nothing to do with how I perform in school. They were creating this entire persona and this cruel game out of where my grandmother came from. Toward the end of high school, there was just this resentment of that part of myself. Not necessarily that I wanted to stop being mixed race, but that I just kind of wanted being treated differently to go away.

Going to college in Washington, DC, gave me that opportunity. Hardly anyone could tell that I was like anything but white. And so for a couple of years there, I got to experience the world without micro-aggressions and the casual racism that I had growing up. I was just able to coast by on whiteness, which was, coming from where I was, a bit of a relief. Of course, this was an environment that I didn’t fit into for a number of other reasons, even if I could present and act white. There was a substantial difference from my rural, more middle-class upbringing as opposed to the white wealthy upbringing many of my peers had. Even being white, it was a different kind of white.

- Kamala Harris, multiracial identity, and the fantasy of a post-racial America

I think after a couple of years of wrestling with, “I’m never going to be white enough or rich enough to fit in with this,” brought me back to trying to reflect more on my grandma and her heritage and my father’s experience. My father identifies as a person of color, but his response to it, especially as he had children, was to sort of push it to the side. For all intents and purposes, my brother and I were raised with no connection to being Japanese, and he didn’t really do anything to encourage it. His experience growing up in rural Minnesota being called every racial slur under the sun, I think there’s trauma there. I think my parents operated to try and raise us to have a better and easier life.

How I identify, and being non-binary, it’s something I’m grappling with constantly. This isn’t to say that my experience is harder than other people’s. But there is that constant vigilance to not, you know, slip into comfortable. As a masculine, white-passing person, life would probably go by fine for me. It’s having that self-awareness and continuously working on the awareness to keep pushing against white supremacy and patriarchy wherever it shows up.

Thema Reed, 27, based in Austin, Texas

I consider myself to be Chicana and Black. On my dad’s side, I’m what a lot of New Mexican people would call Hispanic, which is a pretty generic term. And then my mom is a Black woman who was adopted and raised by a white woman when she was 14. She is still really connected to her Black roots, and we have a big Black family that we’re so very connected to. But there’s kind of a few different layers in there.

I’ve always identified as both, but I definitely felt a lot of pressure to identify or present myself in different ways throughout my life. I’ve heard some Black people say, “Well, mixed people aren’t actually Black.” And I think that a lot of that comes from a feeling that mixed people can maybe turn off their Blackness sometimes or that mixed people have features that may give them privileges. I would also hear things like, “Oh, well, it’s a shame that Thema is not more light-skinned.” It’s like, I’m not Black enough, but I’m simultaneously too Black, you know?

At the same time, people who maybe aren’t Black or who aren’t mixed look at me as a Black woman. It is hard for me to get people to understand that just because I don’t look Chicana doesn’t mean that I’m not. In New Mexico, Chicana culture is such a big thing there, I think that most people in New Mexico identify with it to some extent. So I didn’t face as much judgment for not being “Chicana enough” as I did until I moved away.

When I was in college, I went to Howard, and that really changed the way that I was able to identify with the Black part of me. I had never been in a place where there were so many Black people that looked so many different ways. There were so many mixes, and with so many different countries, so many different socioeconomic backgrounds. I really felt really accepted and loved for the first time.

I think I kind of really grew up as a chameleon and I learned how to code switch and communicate with a lot of different people when I was really young. I think that there’s something special about that. But I think it does come with a cost. I really experienced it from both sides — I’ve experienced colorism, I’ve experienced people saying, “Well, you’re not Black and you’re not Mexican enough.” I feel really strongly connected to both, but at the same time, sometimes I feel like I belong to neither.

Jaymes Hanna, 35, based in Washington, DC

I am a mix of Brazilian and Lebanese descent. I think my identity is very much like a Venn diagram, where I keep moving around those various circles and the overlap keeps changing all the time. The one thing I have kept constant is some sense of mixedness. If I have to put myself in a commonly recognized box, it would be Latino.

I grew up in inner-city Philly, in a predominantly Black and Latino neighborhood. I very much connected to those communities and those cultures and tried to do everything to highlight my Latino-ness — from clothes to manner of speech. My father being Lebanese, I think he experienced some prejudices when he moved to the country, given the long history with our region, and was never eager for me to play up that part of my heritage and culture. So growing up in a predominantly Brazilian household, it was just easier to move forward with that, which is another reason why I think I’ve identified as Latino more predominantly.

As I got older and progressed into the engineering world, I sort of shifted. That was probably the first time I was in a very white-dominant setting. I did a lot of stuff to play my Latinoness down until I left for the social impact field where I thought I could sort of reconnect with the Latino pieces of me .

Even now, there’s elements of my identity that don’t get represented so clearly to someone who sees me as an early- to mid-career professional, especially if they’re white. I do get, “Oh, you’re not bad!” especially if I talk about being Latino, growing up in that neighborhood and going to an inner-city public school where I’m treated a certain kind of way by teachers and the powers that be. It’s always frustrating or disappointing because when I hear that, that very much means to me that you don’t see me. Like you want to be comfortable with me in a certain box. You’re not interested in the actual things that have shaped me to be who I am today.

I’ve been called ethnically ambiguous by more than one person. It makes me feel like a blank slate sometimes. But in some ways, it is kind of cool because I feel like if someone’s trying to identify with you or call you one of them, that creates openness to actually connect with people.

Kristina, 43, based in Los Angeles, California

I identify proudly as a multiracial woman and as a woman of color. This is because the world sees me as a woman of color. I’ve never been perceived as a white woman.

I only recently became confident that I could just, in some circumstances, say “I’m Filipino.” I don’t always have to qualify the basis of my identity to everybody. That is very new for me because people always felt the need to say, “You’re only half,” or remind me that I’m also white . But as I’ve gotten older, and just with more recent conversations about race, I’ve come to realize that I don’t care anymore. I am Filipino, I am white. I don’t always have to say all of my mixed percentages to everybody.

When I was younger, I would always qualify everything by saying, “I am half white.” I didn’t want people to think I was trying to co-opt any identities or infringe on anyone’s spaces. In college, friends would take me to Filipino student group meetings, and I just always felt like an imposter, like I didn’t have a right to be there. I don’t know if that’s true or not to this day. I still don’t quite know my place sometimes. I just know I feel at home in the Filipino community with my Filipino family.

At the same time, I didn’t want to feel like that was denying my mom. Even though I don’t identify as a white person, I was raised by a white mom who has a beautiful history and life too. So I don’t like to discount that.

I sort of loathe the inevitable reductive discussions that pop up whenever a multiracial person comes up, whether that’s Kamala Harris or Bruno Mars . I just wish the world knew they don’t get to tell multiracial people how we identify. Each of our own experiences is incredibly unique, depending on who we are raised by, where we were raised, how we look.

I also wish people would stop portraying mixed people as so tragic. I grew up in the ’90s and every discussion about it was about how we were so tortured. It almost seemed like they were putting it out there as a cautionary tale about having multiracial children. But for me, most of the “negative” aspects of being mixed were external, not internal. I absolutely would not change being mixed for the world.

Most Popular

The hottest place on earth is cracking from the stress of extreme heat, india just showed the world how to fight an authoritarian on the rise, take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, cities know how to improve traffic. they keep making the same colossal mistake., the backlash against children’s youtuber ms rachel, explained, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Culture

The messy discussion around Caitlin Clark, Chennedy Carter, and the WNBA, explained

Baby Reindeer’s “Martha” is, inevitably, suing Netflix

Kate Middleton’s cancer diagnosis, explained

Why are we so obsessed with morning routines?

Here are all 50+ sexual misconduct allegations against Kevin Spacey

I know I’m supposed to be investing. How do I start?

The golden age of retail loyalty programs is here

This is your kid on smartphones Audio

World leaders neglected this crisis. Now genocide looms.

Challenges and benefits of growing up mixed-race

“Matthew, why can’t you speak Arabic?”

“Matt, why can’t you ‘talk Tagalog’ like your cousins?”

These are phrases I often heard growing up as a mixed-race child when I traveled abroad to visit my extended family. As a son of immigrants from third world countries, I’ve been removed from the lifestyles and experiences of my cousins, nieces, nephews: catching trains and buses in movement, selling soap to make some pocket cash and performing manual labor (scrubbing tables and working on rural farms). For them, there is little to no opportunity for scholarly activity.

As a first-generation American, I’ve mostly seamlessly adapted to the American way of life: relying on machine household appliances, driving to places in our family’s car and educating myself through technology. My point is that growing up as a mixed-race child in the United States is far more comfortable than growing up mixed race in my father’s and mother’s home countries (Egypt and the Philippines, respectively); I am thankful for this situation. Furthermore, growing up in Hawaii –– a “melting pot” of diverse cultures –– has enhanced my quality of life substantially, especially since I don’t fully experience racism when traveling to other states or abroad.

It would be a lie if I were to say that there aren’t certain benefits that are part of the “package deal” of existing with a mixed-race identity. One such advantage is that many mixed-race individuals, in my experience, are like social chameleons and can blend into cultures fairly easily because of our unique phenotypes. For instance, I face little trouble receiving invitations to various Stanford cultural group events because, I appear ethnically ambiguous –– almost as if I claim a part of every heritage. As a result of this assumption, mixed-race people tend to relate to others fairly easily (hence the “Barack Obama effect”).

But like with every good thing, there is a flip side, a counterargument, another dimension. For instance, when I travel back to my parents’ home countries, I feel cut off from my non-English-speaking family. There exists a cause for limited communication: the language barrier. Additionally, people constantly believe that I am not American and ask me, “What are you?” (what they’re really asking is, “What ethnic box do you fit into?”). This question fails to account for the fact that I am much more than my ethnicity: I am also a friend, a son, a brother, a student. And in the realm of being a student, finding a campus community on Stanford’s campus that I can claim as my own tends to be incredibly difficult. In all honesty, at times I doubt whether or not I belong in PASU (Pilipino-American Student Union) or ASAS (Arab Students Association at Stanford).

Nonetheless, these are simply my experiences growing up and currently living as a mixed-race identifying person. The mixed-race experience deviates widely depending on the age, gender, sexual orientation and socioeconomic status of each person. All in all, however, although growing mixed race is still a double-edged sword, I have learned to accept myself and my identity, as well as their opportunities and their challenges.

Contact Matthew Mettias at mmettias ‘at’ stanford.edu.

Matthew ("Matt") Mettias '23 writes for the Grind. He is from Aiea, Hawaii. His hobbies include taking care of his Chihuahua puppy; playing pickup basketball; and listening to Jawaiian, rap/hip-hop and 1960s music. Contact him at mmettias 'at' stanford.edu.

Login or create an account

The Biracial Advantage

People of mixed race occupy a unique position in the u.s. their experiences of both advantage and challenge may reshape how all americans perceive race..

By Jennifer Latson published May 7, 2019 - last reviewed on December 21, 2020

One of the most vexing parts of the multiracial experience, according to many who identify as such, is being asked, "What are you?" There's never an easy answer. Even when the question is posed out of demographic interest rather than leering curiosity, you're typically forced to pick a single race from a list or to check a box marked "other."

Long before she grew up to be the Duchess of Sussex, Meghan Markle wrestled with the question on a 7th-grade school form. "You had to check one of the boxes to indicate your ethnicity: white, black, Hispanic, or Asian," Markle wrote in a 2015 essay. "There I was (my curly hair, my freckled face, my pale skin, my mixed race) looking down at these boxes, not wanting to mess up but not knowing what to do. You could only choose one, but that would be to choose one parent over the other—and one half of myself over the other. My teacher told me to check the box for Caucasian. 'Because that's how you look, Meghan.' "

The mother of all demographic surveys, the U.S. census, began allowing Americans to report more than one race only in 2000. Since then, however, the number of people ticking multiple boxes has risen dramatically.

Today, mixed-race marriages are at a high, and the number of multiracial Americans is growing three times as fast as the population as a whole, according to the Pew Research Center. Although multiracial people account for only an estimated 7 percent of Americans today, their numbers are expected to soar to 20 percent by 2050.

This population growth corresponds to an uptick in research about multiracials, much of it focused on the benefits of being more than one race. Studies show that multiracial people tend to be perceived as more attractive than their monoracial peers, among other advantages. And even some of the challenges of being multiracial—like having to navigate racial identities situationally—might make multiracial people more adaptable, creative, and open-minded than those who tick a single box, psychologists and sociologists say.

Of course, there are also challenges that don't come with a silver lining. Discrimination , for one, is still pervasive. For another, many mixed-race people describe struggling to develop a clear sense of identity—and some trace it to the trouble other people have in discerning their identity. In a recent Pew survey, one in five multiracial adults reported feeling pressure to claim just a single race, while nearly one in four said other people are sometimes confused about "what they are." By not fitting neatly into one category, however, researchers say the growing number of multiracial Americans may help the rest of the population develop the flexibility to see people as more than just a demographic—and to move away from race as a central marker of identity.

Hidden Figures

In 2005, Heidi Durrow was struggling to find a publisher for her novel about a girl who, like her, had a Danish mom and an African-American dad. At the time, no one seemed to think there was much of an audience for the biracial coming-of-age tale. Three years later, when Barack Obama was campaigning for president and the word biracial seemed to be everywhere, the literary landscape shifted. Durrow's book, The Girl Who Fell From the Sky , came out in 2010 and quickly became a bestseller.

How did an immense multiracial readership manage to fly under the publishing world's radar? The same way it's remained largely invisible since America was founded: Multiracial people simply weren't talking about being multiracial. "There's a long, forgotten history of mixed-race people having achieved great things, but they had to choose one race over the other. They weren't identified as multiracial," Durrow says. "Obama made a difference because he talked about it openly and in the mainstream."

When Durrow's father was growing up in the '40s and '50s, race relations were such that he felt the best bet for an African-American man was to get out of the country altogether. He joined the Air Force and requested a post in Germany. There he met Durrow's mother, a white Dane who was working on the base as a nanny. When they married, in 1965, they did so in Denmark. Interracial marriage was still illegal in much of the U.S.

Durrow grew up with a nebulous understanding of her own identity. During her childhood , her father never told her he was black; she knew his skin was brown and his facial features were different from her mother's, but that didn't carry a specific meaning for her. Neither he nor her mother talked about race. It wasn't until Durrow was 11, and her family moved to the U.S., that the significance of race in America became clear to her. "When people asked 'What are you?' I wanted to say, 'I'm American,' because that's what we said overseas," she recalls. "But what they wanted to know was: 'Are you black or are you white?'"

Unlike at the diverse Air Force base in Europe, race seemed to be the most salient part of identity in the U.S. "In Portland, I suddenly realized that the color of your skin has something to do with who you are," she says. "The color of my eyes and the color of my skin were a bigger deal than the fact that I read a lot of books and I was good at spelling."

And since the rules seemed to dictate that you could be only one race, Durrow chose the one other people were most likely to pick for her: black. "It was unsettling because I felt as if I was erasing a big part of my identity, being Danish, but people thought I should say I was black, so I did. But I was trying to figure out what that meant."

She knew that a few other kids in her class were mixed, and while she felt connected to them, she respected their silence on the subject. There were, she came to realize, compelling reasons to identify as black and only black. The legacy of America's "one-drop rule"—the idea that anyone with any black ancestry was considered black—lingered. So, too, did the trope of the "tragic mulatto," damaged and doomed to fit into neither world.

Being black, however, also meant being surrounded by a strong, supportive community. The discrimination and disenfranchisement that had driven Durrow's father out of the U.S. had brought other African Americans closer together in the struggle for justice and equality. "There's always been solidarity among blacks to advance our rights for ourselves," Durrow says. "You have to think of this in terms of a racial identity that means something to a collective, to a community."

Today, Durrow still considers herself entirely African American. But she also thinks of herself as entirely Danish. Calling herself a 50-50 mix, she says, would imply that her identity is split down the middle. "I'm not interested in mixed-race identity in terms of percentages," she explains. "I don't feel like a lesser Dane or a lesser African American. I don't want to feel like I'm a person made of pieces."

She's always longed for a sense of community with other multiracial people who share her feeling of being multiple wholes. When she sees other mixed-race families in public, she often gives them a knowing nod, but mostly gets blank stares in return. "I definitely feel a kinship with other mixed-race people, but I understand when people don't," she says. "I wonder if that's rooted in the fact that they didn't know they were allowed to be more than one." It's true that the majority of Americans with a mixed racial background—61 percent, according to a 2015 Pew survey—don't identify as multiracial at all. Half of those report identifying as the race they most closely resemble.

It's also true that racial identity can change. The majority of multiracial people polled by Pew said their identity had evolved over the years: About a third had gone from thinking of themselves as multiple races to just one, while a similar number had moved in the opposite direction, from a single race to more than one.

The New Face of Flexibility

Because she craved an opportunity to connect with other multiracial Americans, Durrow created one: the Mixed Remixed Festival. In 2014, the comedians Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele, both of whom have a black father and a white mother, were named the festival's storytellers of the year. Like Durrow's book, their Emmy-winning show, Key & Peele , had found an immense audience. They credit the show's network, Comedy Central, for recognizing them as biracial—not just black—and giving them a platform to tell that story. "The only thing they ever got annoying about was, 'More biracial stuff!' It was never, 'Make it blacker,' " Key said when the pair accepted their award.

"Comedy is something one relates to, and in discussing the mixed experience, we found a comedy that doesn't speak just to mixed people but to everybody," Peele said. "It's about being in an in-between place and being more complex than you are given credit for." As multiracial people become more visible and more vocal in mainstream America, researchers are paying more attention . And they're finding that being mixed-race carries many advantages along with its challenges.

This complexity is itself both an advantage and a disadvantage, says Sarah Gaither, a social psychologist at Duke University. Being a mix of races can lead to discrimination of a different kind than single-race minorities face, since multiracial people often endure stereotyping and rejection from multiple racial groups. "My research, and the work of others, argues that there are benefits and costs at the same time," Gaither says. "Multiracials face the highest rate of exclusion of any group. They're never black enough, white enough, Asian enough, Latino enough."

It's surprising, then, that more people in this group say being multiracial has been an advantage rather than a disadvantage—19 percent vs. 4 percent, according to a Pew survey. And Gaither's research found that those who identify as multiracial, instead of just one race, report higher self-esteem , greater well-being, and increased social engagement.

One advantage of embracing mixedness, she says, is the mental flexibility that multiracial people develop when, from a young age, they learn to switch seamlessly between their racial identities. In a 2015 study, she found that multiracial people demonstrated greater creative problem-solving skills than monoracials—but only after they'd been primed to think about their multiple identities beforehand.

These benefits aren't limited to mixed-race people, though. People of one race also have multiple social identities, and when reminded of this fact in Gaither's study, they, too, performed better on creativity tests. "We said, 'You're a student, an athlete , a friend.' When you remind them that they belong to multiple groups, they do better on these tasks," she says. "It's just that our default approach in society is to think of a person as one single identity." What gives multiracial people a creative edge may simply be that they have more practice navigating between multiple identities.

Being around multiracial people can boost creativity and agile thinking for monoracials, too, according to research by University of Hawaii psychologist Kristin Pauker. Humans are compartmentalizers by nature, and labeling others by social category is part of how we make sense of our interactions, she says.

Race is one such category. Humans have historically relied on it to decide whether to categorize someone as "in-group" or "out-group." Racially ambiguous faces, however, foil this essentialist approach. And that's a good thing, Pauker's research shows.

She found that just being exposed to a more diverse population—as often happens, say, when students move from the continental U.S. to Hawaii for college—leads to a reduction in race essentialism. It also softens the sharp edges of the in-group and out-group divide, leading to more egalitarian attitudes and an openness to people who might otherwise have been considered part of the out-group.

The students whose views evolved the most, however, were those who'd gone beyond just being exposed to diversity and had built diverse acquaintance networks as well. "We're not necessarily talking about their close friends—but people they've started to get to know," she says. What does that show us? "To change racial attitudes, it's not only being in a diverse environment and soaking things up that makes the difference: You have to formulate relationships with out-group members."

The Averageness Advantage

The cognitive benefits of being biracial may stem from navigating multiple identities, but some researchers argue that multiracial people enjoy innate benefits as well—most notably, and perhaps controversially, the tendency to be perceived as better looking on average than their monoracial peers.

In a 2005 study, Japanese and white Australians found the faces of half-Japanese, half-white people the most attractive, compared with those of either their own race or other single races. White college students in the U.K., meanwhile, were shown more than 1,200 Facebook photos of black, white, and mixed-race faces in a 2009 study and rated the mixed-race faces the most attractive. Only 40 percent of the images used in the study were of mixed-race faces, but they represented nearly three-quarters of those that made it into the top 5 percent by attractiveness rating.

More recently, a 2018 study by psychologists Elena Stepanova at the University of Southern Mississippi and Michael Strube at Washington University in St. Louis found that a group of white, black, Asian, and Latino college students rated mixed-race faces the most attractive, followed by single-race black faces.

Stepanova wanted to know which of two prevailing theories could better explain this finding: the "averageness" hypothesis, which holds that humans prefer a composite of all faces to any specific face, or the "hybrid vigor" theory, that parents from different genetic backgrounds produce healthier—and possibly more attractive—children.

In the study, Stepanova adjusted the features and skin tones of computer-generated faces to create a range of blends, and found that the highest attractiveness ratings went to those that were closest to a 50-50 blend of white and black. These faces had "almost perfectly equal Afrocentric and Eurocentric physiognomy," she says, along with a medium skin tone. Both darker- and lighter-than-average complexions were seen as less attractive.

These results seem to support the theory that we prefer average faces because they correspond most closely to the prototype we carry in our minds: the aggregated memory of what a face should look like. That would help explain why we favor a 50-50 mix of features and skin tones—especially since that doesn't always correspond to a 50-50 mix of genes, Stepanova says. "The genes that are actually expressed can vary," she says.

A 2005 study led by psychologist Craig Roberts at Scotland's University of Stirling, however, supports the hybrid vigor hypothesis—that genetic diversity makes people more attractive by virtue of their "apparent healthiness." The study didn't focus on multiracial people per se, but on people who'd inherited a different gene variant from each parent in a section of DNA that plays a key role in regulating the immune system—as opposed to two copies of the same variant. Men who were heterozygous, with two different versions of these genes, proved to be more attractive to women than those who were homozygous. And while being heterozygous doesn't necessarily mean you're multiracial, having parents of different races makes you much more likely to fall into this category, Roberts says.

Whether these good-looking heterozygotes are actually healthier or just appear so is debatable. Studies have shown that heterozygotes are indeed more resistant to infectious diseases, including Hepatitis B and HIV, and have a lower risk of developing the skin disease psoriasis—significant because healthy skin plays a clear role in attractiveness. But other researchers have been unable to find a correlation between attractiveness and actual health, which may be a testament to the power of modern medicine—especially vaccinations and antibiotics—in helping the less heterozygous among us overcome any genetic susceptibility to illness, Roberts says.

Research vs. Real World

Some researchers have extrapolated even further, suggesting that, along with possible good looks and good health, multiracial people might be genetically gifted in other ways.

Cardiff University psychologist Michael B. Lewis, who led the 2009 U.K. study on attractiveness, argues that the genetic diversity that comes with being mixed race may in fact lead to improved performance in a number of areas. As evidence, he points to the seemingly high representation of multiracial people in the top tiers of professions that require skill, such as Tiger Woods in golf, Halle Berry in acting, Lewis Hamilton in Formula 1 racing, and Barack Obama in politics .

Other researchers argue that this conclusion is an overreach. They counter that genetics doesn't make multiracial people better at golf—or even necessarily better looking. Some studies have found no difference in perceived attractiveness between mixed-race and single-race faces; others have confirmed that a preference for mixed-race faces exists, but have concluded it has more to do with prevailing cultural standards than any genetic predisposition to beauty.

A 2012 study by Jennifer Patrice Sims, a sociologist at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, found that in general, mixed-race people were perceived as more attractive than people of one race—but not all racial mixes, as would be the case if the cause was genetic diversity alone. (In her research, mixed black-Native Americans and black-Asians were rated the most attractive of all.) The hybrid vigor theory, Sims argues, is based on the false presumption of biologically distinct races. She points instead to evidence that attractiveness is a social construct, heavily dependent on time and place. In the U.S. right now, she says, the biracial beauty stereotype is a dominant narrative.

"Whereas in the past, particularly for women, the stereotypical northern European phenotype of blonde hair, blue eyes, and pale skin was considered the most attractive (think Marilyn Monroe) contemporary beauty standards now value 'tan' skin and wavy-curly hair also (think Beyonce)," she says.

But saying biracial people are inherently beautiful isn't a harmless compliment—it can contribute to exotification and objectification. For many biracial people, these reports of heightened attractiveness are an unwelcome distraction, obscuring and delegitimizing the true challenges they face. "Even though studies say we're seen as more beautiful, my lived experience negates that," says Ben O'Keefe, a political consultant who has a black father and a white mother. "We're trying to frame it as if we've become a more accepting society, but we haven't. There are still many people who wouldn't be comfortable dating outside their race."

O'Keefe's father wasn't present when he was growing up. Apart from his brother and sister, he was surrounded by white people. His mother raised him to embrace the principle of "color blindness." Since race doesn't matter, she argued, why acknowledge it at all? O'Keefe thought of himself, essentially, as white. When people asked what he was, he said Italian, which is true. He's Italian, Irish, and African American.

But other people's perceptions didn't match his self-image . A store clerk once followed him from aisle to aisle and accused him of shoplifting. While walking one night in his upper-class, predominantly white Florida community, O'Keefe was stopped by police who pulled their guns on him because residents had reported a "suspicious" black teen . When Trayvon Martin was killed nearby under similar circumstances, it triggered an awakening in O'Keefe: "I had always felt more white, but the world didn't see me that way."

The Path Forward

As much as O'Keefe wishes that milestones such as Obama's presidency signaled the dawn of a post-racial America, he encounters daily reminders that racism endures. One boy he dated in high school didn't want to bring O'Keefe home to meet his parents. "Oh, they don't know you're gay?" O'Keefe asked. "No, they do," the boy responded. "They'd just freak out if they knew I was dating a black guy."

O'Keefe has encountered discrimination in the black community as well, where others have told him, "You're not really black."

"They see me with light skin and a white family, and that has given me advantages—I recognize that. Their experience, being seen as nothing but black, influences that perception." While he understands the reasoning, it still hurts. "It's saying, 'You're not black enough to be a real black man, but you're black enough to be held up at gunpoint by police,' " he says.

These days, he doesn't get asked, "What are you?" as much as he once did, which could be a sign of progress—or simply a byproduct of moving in more "woke" circles as an adult, he says. But when he does get asked, he identifies as black. "I'm a black man who is multiracial, but it doesn't diminish my identity as a black man."

His mother, too, has abandoned her color-blind approach after coming to see it as unrealistic—and ultimately unhelpful. "We've had some really hard conversations about race," O'Keefe says. "She's embraced that it matters and we need to talk about it, and we can't fix problems if we pretend they don't exist."

The path toward a more egalitarian America will be paved with hard conversations about race, says Gaither, who is multiracial herself. Her research shows that just being around biracial people makes white people less likely to endorse a color-blind ideology—and that color blindness, although well-intentioned, is ultimately harmful to race relations.

In a series of studies published in 2018, Gaither found that the more contact white people had with biracial people, the less they considered themselves color-blind, and the more comfortable they were discussing issues around race that they would otherwise have avoided. This suggests that a growing multiracial population will help shift racial attitudes. But it doesn't mean the transition will be easy.

"If you're in a primarily white environment and multiracial populations are growing, you may find that threatening and look for ways to reaffirm your place in the hierarchy," says the University of Hawaii's Pauker. "As minority populations grow, that's going to be a hard adjustment on both sides."

While there's no population threshold that, once reached, will signal the end of racism in America, being around more multiracial people can at least nudge monoracials to start thinking and talking more about what race really means.

"We are not the solution to race relations, but we cause people to rethink what race may or may not mean to them, which I hope will lead to more open and honest discussions," says Gaither. "The good news is that our attitudes and identities are malleable. Exposing people to those who are different is the best way to promote inclusion—and the side effect is that we can benefit cognitively as well. If we start acknowledging that we all have multiple identities, we can all be more flexible and creative."

The Multiethnic Elite

People of mixed race are well represented at the top of many fields

Submit your response to this story to [email protected] . If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the the rest of the latest issue.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Skip to Nav

- Skip to Main

- Skip to Footer

Growing Up Mixed and Grappling With the Question 'What Are You?': Listeners Weigh In

Please try again

This post is part of a series of stories on The California Report Magazine about the experience of being mixed race.

This story originally published in November of 2021. The "Mixed!" series will include new interviews through March and April of 2023.

Identity is always complicated, and for multiracial folks who straddle many identities, it can be isolating. It can also be invigorating and rich to belong to multiple communities and celebrate that complexity.

The latest census shows we mixed-race people are a demographic to pay attention to: 2020 data reflects a 276% increase in people who identify as multiracial compared to 2010. Yet mixed-race folks are only beginning to find space for our stories.

This week, The California Report Magazine's host, Sasha Khokha and guest host Marisa Lagos delve into the mixed-race experience, grounded in their own backgrounds. They talk with trailblazing artist Kip Fulbeck, whose photo projects are a platform for mixed-race folks to answer the question "What Are You?" in their own voices. We also listen in on a conversation between two listeners who share a similar background (Black/Filipina), but straddle different generations, which informs how they understand their identities.

To bring you, our audience, into this series, The California Report and KQED has been reaching out to listeners to ask, “What's something only fellow mixed folks understand about growing up mixed?”

Here are some of those responses:

Dianna K. Bautista, Berkeley

I'm Filipino on my mom's side, and my dad is mixed like me. He is Filipino, African American, Native American, French and Spanish. My dad would tell me how it was like for my grandmother as a Black woman of color growing up in Arkansas. We would dive back [into our family history] and see how my Native American ancestors were sold in slavery.

If I just check one box, I feel like it doesn't fully represent who I am. But when I check multiple boxes, I'm always questioning if I have enough of that heritage, enough of that ethnicity to check that box. And you're in the middle of having a mini-identity crisis because you're not sure which box to check.

I was reading about this mixed Iranian journalist who is saying how her mixed experience was like floating. It's kind of cool because, yeah, ambiguous skin means that you’re accepted in different groups and different ethnicities and you get to experience that diversity. But there's also negatives to that because you're ambiguous. People are going to assign stereotypes based on what they think you are and you don't have control over that.

Dylan Morimoto, San Francisco

My father is from Auburn, California, and he's Japanese, and my mom was born in Germany. She's Jewish. My father was incarcerated during World War II. My [dad's whole] family was incarcerated or interned during World War II. And then my mom, you know, left Nazi Germany. You know, I don't look Jewish. I don't really think I look kind of Asian-ish.

Under the Trump administration, [it was] really upsetting, given my family’s history. It’s nice to see, for me personally, I was happy to see Kamala Harris get elected, and seeing her, you know an African American and Asian woman, was really, really cool. And a Jewish husband, and a mixed family. I am in the same situation. I have two stepkids, so it’s nice to see that diversity.

Sharon Ng, San Francisco

Our family is kind of China-Latina mashed up. I am Chinese Malaysian and grew up in Vancouver, Canada. My American husband's family is Argentinian but he grew up in France. We met in New York. When people ask my daughter what her heritage is, she says, "I am half Chinese and half Brooklyn!"

While I am Chinese by blood, culturally I struggled as a child to understand my “Chineseness” because I did not grow up speaking Mandarin at home, nor did I have the benefit of an extended family of aunties and grandparents to provide context about how to be Chinese. With limited Chinese affirmation and sense of place, it was quite confusing because Vancouver was really white in the '70s.

[My husband] Ian's story is similar. He didn't grow up speaking Spanish, because the U.S. was all about assimilation back then. We feel that learning Spanish will help anchor our kids in part of their roots, which we don't feel we really had (we know our parents tried their very best). Together we are creating new traditions of what is beautiful and delicious: turkey stuffed with sticky rice, with empanadas and chimichurri on the side.

That said, we dream that our girls have a sense of belonging and experience affirmation of their multifaceted identities and cultural ways of being a “hyphenated” American. We feel really blessed to live in San Francisco, where we have lots of other friends who are raising mixed-race families. It really normalizes things for them.

Adrien Colón, Oakland

So my mom is white and my dad is Puerto Rican. And I think growing up as a kid, I never really questioned it. And it's not until I got a little older that I heard this story about my dad not being allowed in my great-grandparents’ home. They were very much against my mom marrying my dad and they wouldn't allow him in their home because of the way that he looked, because of the color of his skin, the Afro that he wore.

I continue to piece together my family tree, and seeing these people who come from all of these different places, and knowing that ... if something had happened to any one of them, that I wouldn't be here, which is a wild thought.

Stephen Zendejas, Tracy

My dad is a third-generation Mexican American and my mom is an immigrant from the Philippines who is half Chinese. I would describe growing up as mixed race [as] kind of confusing and complex.

I think the concept of racial identity is sometimes still foreign and confusing to me because it's more social than it is scientific. But it's also not something that we can just completely ignore either.

David Risher, San Francisco

[There are ] so many stories from my childhood in the '70s. I can't count the number of times someone cocked his or her head at me, paused, and asked, "I've got a question for you. What are you?” It was so uncomfortable. My answer at the time: "My mother is white, my father is Black. So I'm both.” Today, I just say I’m biracial.

Here’s a story that sticks with me, from my time attending summer camp as a kid. One day, just before parents’ weekend, I overheard a fellow camper say, "I don't know about you, but I'd be ashamed if I were you about having a Black dad and a white mom.” In fact, I wasn’t the least ashamed. But hearing that made me wonder, “Should I be?"

And [there’s] another story from my undergraduate years at Princeton. One evening, my well-meaning Black dorm-mate brought me into her room and said, "David, at some point you're going to have to choose. If you don't, others will for you, and they’ll make their decision based on who your girlfriend is.” I was shocked, but I got it. People are detectives, looking for clues.

Today, after years working at Microsoft and then as an executive at Amazon, I run a Bay Area nonprofit called Worldreader. We use technology and local books from all around the world to help children discover the joy of reading. We’ve helped 19 million children so far, and we’re just getting started. One thing that sets us apart: No matter where we operate — in Africa, India, South America, or the U.S. — we lead with books from local publishers, full of stories of doctors, astronauts, scientists and writers who look like our readers. I bet you see the connection: If you can’t see it, you can’t be it!

Ruben Villareal Halprin, San Francisco

My mom, a Jewish girl from Boston, met my father, a Black Cuban, while at medical school in Cuba in the late '80s. They got married a couple of years later and I showed up shortly after that. I was the “white boy.” I was “Ruben the Cuban.” I was “blanquito.” It just depends on where I was.

I wonder sometimes if I looked a little more like my mom or a little more like my dad, how different my life would be. Mind you, that's not if my life would be different, but just how different. I love being mixed. I love dancing between the lines of the binaries that this society has built up ... . In a way, I represent the breaking of cultural and institutional barriers that exist or existed. But breaking down barriers may just be a poetic way of saying you're being slammed into a wall. And that's certainly what it sometimes felt like growing up mixed.

To learn more about how we use your information, please read our privacy policy.

- Engaged Couples

- Married Couples

- Free Relationship Advice

Growing Up Biracial: How I Learned To Embrace Diversity

Jennifer Jones - July 16, 2019

Topic: Culture , Family , Parenting , Relationships

I want to begin by pointing out that my experience is just one of many.

Our mother married our father during a time when interracial marriage was unacceptable, in 1969, two years after interracial marriage was legalized, and most of her family disowned her. Growing up, she told us, "You're Black because your father is Black," and I never understood why she didn't urge us to identify as both White and Black, or biracial. I know she did the right thing, and she did what she knew was best, based on her encounters of racial discrimination.

We don't know anyone from her family. Our mother’s family on both sides were from Russia, with her parents being first-generation Americans; she was raised Jewish. My siblings and I desire to find her family one day with the hope that someone in the family line has challenged and changed that part of their story. Our father passed away when I was 9 years old. We only know a handful of people from our father's family, and the extended family resides in Texas. On his side, we are told there is also Cherokee Indian in our bloodline. I think of the pain my mother must have carried raising Black children in this world. I think of what it may have been like for her being raised up in a family plagued with racist beliefs. Yet, she chose love, and encouraged us to embrace our Blackness. People will always see me as a woman of color, and I am proud of that.

My racial identity has developed through a lifetime of relationships with family, friends, teachers and mentors. I attended schools abundantly black and brown. Nevertheless, amongst my childhood peers, I felt a sense of not being enough — not Black enough, and certainly not White. My Whiteness was either disproportionately valued, or frankly rejected. Common statements I heard in my childhood pertained to prettiness, or having “good” hair, or being intelligent, which was attributed to the fact that I am mixed with White. If I was interested in this music as opposed to that music, I was White. At times, Black girls of a deeper skin tone assumed I was arrogant.

"I attended schools abundantly black and brown. Nevertheless, amongst my childhood peers, I felt a sense of not being enough..."

Some Black people have been shocked to find out I comb my daughters' hair well because it is of a different texture than mine. There have been times when I’ve had to correct my mom’s thinking errors around race and identity (i.e. her mentioning “good” hair).

I understand the painful history that created such divisions within Black communities. I think this all speaks to how susceptible we are as humans to learn and then become entrenched in hurtful ideology. It’s difficult to hear my White friends express discomfort discussing issues of race, even to the point of avoidance, but it’s also an opportunity to meet them where they are and pray for time and space to continue the conversation. In a way, my biracial identity allows for a bridging of gaps.

Systematic narratives can only be changed if we each, in our own communities, have the conversations. That starts in our homes. In my home, my children and I are blessed and grateful to have a front row seat witnessing a present Black father every day. My father was present, as well. In our home, there is living proof that dismantles the message that Black fathers are absent. We strive to educate our children on history in an age-appropriate, expand-as-they-grow, honest and inclusive way. We highlight the beauty, richness and strengths of our people. Reading is fundamental to helping children embrace their culture and heritage. A few children’s books we have in our home are: I’m a Pretty Little Black Girl by Betty K. Bynum, I Like Myself by Karen Beaumont, Daddy Calls Me Man by Angela Johnson, and Bright Eyes, Brown Skin by Cheryl Hudson. When we go to children’s birthday parties and books are requested over toys, we aim to purchase culturally uplifting books. We have playdates with other families, attend museums and community events, and family gatherings — food, music and shared stories are powerful agents of cultural connection.

"Systematic narratives can only be changed if we each, in our own communities, have the conversations. That starts in our homes."

Connection through community is critical in raising culturally attuned children. Through relationship, we learn about who we are and gain a sense of belonging. As parents, we cannot control everything our children are exposed to, but as their first and primary teachers, we are actively teaching them about racism. We also learn about differences. Love and hate are learned.

These are some practical action steps for parents of biracial children and parents of White children who want to instill cultural awareness and sensitivity:

1. Examine your own cultural biases. We all have them. Literature, documentaries and films are a good starting point, but in vivo experiences (i.e. community events, museums, small groups at church) have the most impact, and can easily be a family affair. Christian authors John Hambrick and Teesha Hadra wrote a book, Black and White: Disrupting Racism One Friendship at a Time , that may lend additional insight.

2. Talk about differences explicitly and intentionally, being mindful of the language you use. Use language that is color-conscious as opposed to color-blind, or racist. Celebrate your biracial identity. Acknowledge your privilege and use it for good. Ask and don’t assume you know someone else’s experience.

3. Notice who your child’s peers are in school, at church and on social media — and get curious! By asking questions about who their friends are, what makes for a good friend, and how they handle challenges amongst their peers, a dialogue about differences can begin. This can also be an opportunity to help transform the language they use around diversity.

Repeat steps 1, 2 and 3 until this lifelong class is dismissed. We are all made in his image. He died on the cross for all sinners. In Revelation 7:9–10, there’s a vivid picture of what we have to look forward to:

After this I looked, and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb. They were wearing white robes and were holding palm branches in their hands. And they cried out in a loud voice: “Salvation belongs to our God, who sits on the throne, and to the Lamb.”

With that as our glimpse into heaven and eternity, we should be moved to embrace diversity on earth, here and now.

Jennifer Jones

Jennifer Jones is a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist. Born and raised in Southern California, she received her Sociology and Black Studies degrees from the University of California Santa Barbara and her Master’s Degree in Clinical Psychology from Antioch University, Santa Barbara. Jennifer is a busy and blessed wife to Marquel Jones and mother to three young children. Her family attends and serves at Inglewood Southside Christian Church. One of Jennifer’s passions is encouraging people, through her writing, to shush their shame; she is currently developing the God-breathed vision for SHHH: Silent Hearts Heal Here. Jennifer is passionate about mental health. In her day job, she supervises a team serving children and teenagers with high acuity symptoms and behaviors. She has served as a therapist during the Biola CMR Marriage Conference for the past few years, as well.

- Previous Post

More from CMR

The first step for effective communication: reclaiming the power of words, top 3 barriers to effective listening and how to overcome them, causes of conflict pt 3: “can you hear me now”, preparing your marriage for parenthood.

(562) 903-4708

Loading ....

- Social Justice

- Environment

- Health & Happiness

- Get YES! Emails

- Teacher Resources

- Give A Gift Subscription

Opinion Advocates for ideas and draws conclusions based on the author/producer’s interpretation of facts and data.

Shapeshifting: Discovering the “We” in Mixed-Race Experiences

Sometimes you don’t know what you’ve been longing for your whole life until you experience it. As a mixed-race woman, I never knew how much it would mean for me to finally sit in a room full of other multiracial women until, at age 45, I taught a creative writing class called Shapeshifting: Reading and Writing the Mixed-Race Experience . I was nervous because I’d never attended something like this myself. And yet, sometimes when it becomes clear that you need something that doesn’t already exist, you have to create it yourself.

I once considered myself to be a shy person, afraid to speak in public. However, my close friends knew me differently, and at my core I knew myself differently too. While I remained quiet in high school, college, and beyond, in intimate spaces I could be bold and funny. When I was younger, I used to think that my insecurities came from my youth or my gender. But the older I’ve gotten the more I’ve also come to question how much of my conditioning— to feel quiet, silent, and invisible—has come from my mixed-race heritage?

I am an Asian American woman. I am also mixed race—my father is White and my mother is Chinese. And I have many questions.

What does it feel like to grow up and never see reflections of yourself or your family in the shows you watch or the books you read, or to rarely see yourself in positions of power?

For mixed-race people, especially those of us who have one White parent, the answers to questions of identity can be confusing to sort out.

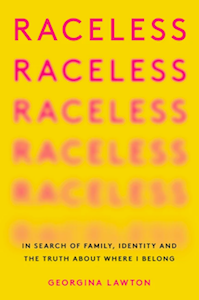

What does it feel like to sense you don’t exist in the outside world, or to never have been given a language—a book of history, a collection of stories, the perspective of an elder—to help name the lineage you are a part of, who you are in relationship to America’s history of racism, or who you are within the rules about who is Black or Asian or Native American or Latinx or White?

How much blood does one need to be able to claim an identity? One half, one quarter, one eighth, one sixteenth, one drop?

Learning more about the history of our nation’s formation has taught me that the answers to questions of identity depends on how much White people have wanted to leverage their control over others’ bodies or lands, and how beneficial it was to claim you as their own. Each racial and ethnic community has a unique relationship to history’s shaping of mixed-race identities, and our absorption into or exclusion from Whiteness depends on the shifting of the White supremacy culture’s needs. Asian Americans, for example, were held up as “model minorities” to prove America’s great myth of meritocracy and used as a wedge against Black people: ‘see, anyone can succeed here if they just try.’ But we have also been expelled from this country, put in concentration camps, perpetually seen as foreign, or dangerous, and most recently, blamed for the spread of a deadly virus.

For mixed-race people, especially those of us who have one White parent, the answers to questions of identity can be confusing to sort out. Many of us who grew up in majority-White communities, have unconsciously been taught to aspire to Whiteness. Conversely, others have been encouraged to deny all ties to Whiteness—or we choose to lean in that direction ourselves once we realize how much we’ve been conditioned to see ourselves as inferior or lacking by the standards of White supremacy culture. But whether we are denying our “color” or denying our “Whiteness,” these false binaries can in turn lead us to internalize the notion that part of us is damaged, inferior, or too shameful to be spoken about. They can make us feel like we have to be shapeshifters to be accepted or belong.

I grew up attending an integrated—yet also highly segregated—high school in Seattle, during the era of Rodney King , and in an environment that taught me to see conversations around race through the binary of Black and White. As a mixed-race Asian girl, I had already learned by then to assimilate and identify with my White peers. It wasn’t until I started college that I realized how much I needed to reclaim my mother tongue of Chinese, a language I grew up speaking with my mother and grandmother as a young child but grew distanced from as an adult. Leaving college, then traveling and living in China for more than three years helped me to reclaim that part of me—as much as it also taught me that the Chinese saw me as a Westerner, as well as how American I truly was.

Most mixed-race people never know what it means to be part of a community where we can feel relaxed or have a sense of belonging when it comes to race.

Back in the U.S., I continued to interrogate my racial identity, but now, once again through an American lens. Here, I am seen by most people as Asian. Here, the terms of how many saw me had changed again—my “otherness” set up against Whiteness, as opposed to against “Chineseness.” Here, it became increasingly crucial for me to drill deeper into my own silence and complicity when it comes to anti-Blackness, implicit bias, and inherited wealth. Attending racial equity trainings, I grew familiar with the practice of dividing the room into two caucusing groups—one for people of color, and one for White people.

By now, I clearly knew I was not White, but I still did not feel comfortable taking up space discussing my identity issues or light-skinned privilege in a group dedicated to people of color. And yet, I also knew that I too had experienced racial pain. I realized that to overcome my own silence around others’ oppression, I needed to give voice to mine too.

Ever since college, I have written privately about my racial in-betweenness, but after returning from China and eventually attending trainings, I developed more of a contextual lens; I learned to see where my struggles aligned with other people of color, and where they diverged. Recently, as a creative writing teacher, I have begun to offer spaces for other mixed-race folks to write about their experiences. I needed to express things privately and I needed share in community, because I realized that shame can only live in silence. Once we voice something in a safe space and we feel witnessed and heard, shame can start to dissipate.

Most mixed-race people never know what it means to be part of a community where we can feel relaxed or have a sense of belonging when it comes to race. Even in our own families, we often look different from our parents or relatives. We perch at the edge of other communities who may tentatively welcome us, but deep down we suspect we don’t fully belong. We have grown up with so many reminders of how our experiences mark us as outsiders, that we have started to distrust ourselves too.

I’m here to tell you, after 25 years of writing and interrogating my own roots and identity, that it doesn’t have to be this way. But where do we begin, especially if we barely know any other mixed-race people?

We can start by reading others’ stories. There aren’t enough of them out there, but that is changing. And we can also begin, at any stage of life, to write our own accounts. In this way, we can begin to name how our experiences are similar to others, for example, how certain traits that we have internalized as our own private maladies may actually stem from larger systemic structures. Furthermore, we can name where our experiences diverge, where our intersectional identities and relative privileges result in our unique stories. We can join affinity groups online, we can find therapists who mirror our origins, we can open up about our deepest vulnerabilities and fears. We can learn to recognize how sometimes shapeshifting harms us, and other times it opens pathways to new conversations. We can begin, one small step at a time, to claim our voice and story as important, and an essential part of contributing to the conversation as we name the dual myth and reality of race.

| is a mixed-race Chinese American writer, editor, and teacher based in Seattle. Her essays have appeared in Longreads, Fourth Genre, Witness, New England Review, Entropy, The Normal School, Literary Mama, and many more. She has received fellowships and support from Seventh Wave, Hedgebrook, Jack Straw Cultural Center, 4Culture, and Hypatia-in-the-Woods. Anne teaches writing workshops at the Hugo House and beyond and loves to support women and BIPOC writers in finding their voice and community. Her memoir, Heart Radical: A Search for Language, Love, and Belonging, is forthcoming in September. She can be reached at www.anneliukellor.com Twitter |

Inspiration in Your Inbox

Sign up to receive email updates from YES!

The Biggest Question After the Mueller Report Is Not Impeachment

Don’t Let Youth Climate Activists Like Me Burn Out

The Fight to Protect Voting Rights Enters the Next Round

Murmurations: A Winter Solstice Spell

Most popular.

The Challenge for Communities to Rise and Take Care of Their Own

Inspiration in your inbox..

Mixed Race Studies

| , and occupied a place of professional and social esteem in their community. They never said a word about their racial background—not even to their children, who absorbed the same toxic prejudices as their white peers. One day, Albert Jr. came home spouting some racial epithet, and his father took him aside to explain that he didn’t know what he was talking about. The revelation shook Albert Jr. A crisis of identity followed, and led, eventually, to his arrival in office. Up until then, the family had maintained their secret. Albert Jr.’s story, if published, would blow their cover. The family agreed to face the consequences, and let the story proceed. The Johnstons would later tell the press that their magnanimous and tolerant neighbors never cared, that the story and its subsequent adaptations had no adverse effect. The fact is, the town did convulse, and whispered slurs behind the family’s back. Albert lost his practice, and eventually moved with to , whose racial complexity made it a more hospitable place. , “ ,” , (February 2016). . |

Growing Up in a Family With Multiple Ethnicities Was Both Lonely and Beautiful

Parents 2022-04-19

Mieko Gavia

I always felt like an outsider, but being mixed is filled with beauty and complexity.

Growing up I always felt like an outsider. My name, my skin, my hair all tells the story of where my parents and my parent’s parents come from. It all marks me as a bit different. I’m mixed Okinawan, Black, and Mexican, and there aren’t a lot of people out there like me. I consider myself lucky to have grown up in a household with mixed parents and siblings because my parents made sure to teach us about our heritage, and about cultures all over the world.

This gave me respect for all sorts of different types of people, and instilled pride in my identity. I am also grateful that they encouraged curiosity about the world, and created an atmosphere where we all “got” each other…

Read the entire article here .

This entry was posted on Thursday, May 5th, 2022 at 15:39Z and is filed under Articles , Asian Diaspora , Autobiography , Family/Parenting , Media Archive . You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. Both comments and pings are currently closed.

- In All Categories Africa South Africa Anthropology Articles Arts Asian Diaspora Audio Autobiography Barack Obama Biography Book/Video Reviews Books Anthologies Chapter Monographs Novels Poetry Campus Life Canada Caribbean/Latin America Brazil Mexico Census/Demographics Communications/Media Studies Course Offerings Definitions Dissertations Economics Europe Excerpts/Quotes Family/Parenting Forthcoming Media Gay & Lesbian Health/Medicine/Genetics History Identity Development/Psychology Interviews Latino Studies Law Letters Literary/Artistic Criticism Live Events Media Archive My Articles/Point of View/Activities Native Americans/First Nation New Media Oceania Papers/Presentations Passing Philosophy Politics/Public Policy Religion Judaism Reports Slavery Social Justice Social Science Social Work Statements Teaching Resources Tri-Racial Isolates United Kingdom United States Louisiana Mississippi Texas Virginia Videos Wanted/Research Requests/Call for Papers Women