You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Suggested Results

Antes de cambiar....

Esta página no está disponible en español

¿Le gustaría continuar en la página de inicio de Brennan Center en español?

al Brennan Center en inglés

al Brennan Center en español

Informed citizens are our democracy’s best defense.

We respect your privacy .

- Research & Reports

Roe v. Wade and Supreme Court Abortion Cases

Reproductive rights in the United States, explained.

Is abortion a constitutional right?

Roe v. wade, what was the impact of the roe v. wade decision.

- The law after Roe v. Wade

Supreme Court justices’ abortion views

Not under the U.S. Constitution, according to the current Supreme Court. In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022), the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade (1973), which guaranteed a constitutional right to abortion. Some state constitutions, however, independently protect abortion rights.

In Roe v. Wade , the Supreme Court decided that the right to privacy implied in the 14th Amendment protected abortion as a fundamental right. However, the government retained the power to regulate or restrict abortion access depending on the stage of pregnancy. And after fetal viability, outright bans on abortion were permitted if they contained exceptions to preserve life and health.

For the following 49 years, states, health care providers, and citizens fought over what limits the government could place on abortion access, particularly during the second and third trimesters. But abortion was fundamentally legal in all 50 states during that period.

Writing for the majority in Dobbs , Justice Samuel Alito said that the only legitimate unenumerated rights — that is, rights not explicitly stated in the Constitution — are those “deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and tradition” and “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.” Abortion, the majority held, is not such a right.

Following Dobbs , reproductive rights are being decided state by state. Constitutions in 10 states — Alaska, Arizona, California, Florida, Kansas, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, New Jersey, and New Mexico — have been interpreted by state high courts to guarantee the right to abortion or protect access more strongly than the federal constitution. Other state legislatures have passed laws protecting abortion rights. Many states, however, have made abortion illegal .

The road to Roe

Abortion was illegal in most states in the 1960s, often with no exceptions for cases of rape or threat to life. A pair of high-profile crises, however, shined a spotlight on the impact of these restrictions.

Beginning in the late 1950s, thousands of babies were born with severe birth defects after their mothers took the morning sickness drug thalidomide while pregnant. The most well-known case was that of Sherri Finkbine, a host of the children’s television program Romper Room , who was forced to travel to Sweden to obtain an abortion. A Gallup poll showed, perhaps surprisingly given the legal backdrop, that a majority of Americans supported Finkbine’s decision.

Shortly after the thalidomide scandal, an epidemic of rubella, or German measles, swept across the country. Babies that survived rubella in utero were often born with a wide range of disabilities such as deafness, heart defects, and liver damage. (A rubella vaccine didn’t become available until 1971.)

It was in this environment of maternal risk that high-profile doctors like Alan Guttmacher began to argue publicly that abortion should be treated like other medical procedures — as a decision to be made between physician and patient.

Griswold v. Connecticut (1965)

While thalidomide and rubella impacted public perspectives on abortion, a series of cases built the foundation for the coming revolution in abortion law. The first involved the right to contraception, and the story begins in the 19th century.

In 1879, Connecticut senator P.T. Barnum (yes, that P.T. Barnum) introduced a bill barring not only contraceptives but also the distribution of information relating to them. The Barnum Act was still on the books in Connecticut in 1960, when the Food and Drug Administration approved the first oral contraceptive. Estelle Griswold, executive director of the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut, was fined $100 for violating the law. Her appeal went all the way to the Supreme Court.

In Griswold v. Connecticut , a seven-justice majority struck down the Barnum Act. Justice William O. Douglas explained that the Bill of Rights implies a right to privacy because when viewed as a coherent whole, it focuses on limiting government intrusions. The Griswold majority held that the government cannot prevent married couples from accessing contraception. (At the time, the justices did not extend the right to unmarried people.) Griswold ’s contention that the Constitution creates a zone of privacy into which the government cannot enter paved the way for Roe , among other landmark decisions.

Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972)

The road from Griswold to Roe was not perfectly straight. Two years after Griswold , reproductive rights activist William Baird offered contraceptives to an unmarried woman after a lecture on contraception to students at Boston University. He was sentenced to three months in prison.

Like Estelle Griswold, Baird appealed his conviction to the Supreme Court. In Eisenstadt v. Baird , the Justices extended Griswold . Justice William Brennan, writing for the six-justice majority, explained that the 14th Amendment guarantees equal protection under the law. There was no reason to treat married and unmarried people differently with regard to contraception.

United States v. Vuitch (1971)

Over the course of nine years, Washington, DC,–based physician Milan Vuitch was arrested 16 times for performing abortions, which had been illegal in the district since 1901 except “as necessary for the preservation of the mother’s life or health.”

Vuitch appealed his eventual conviction, arguing in part that the exception for “health” was unconstitutionally vague. The Supreme Court disagreed in United States v. Vuitch . Taking a broad view of the word “health,” the justices ruled that abortion was legal in the district whenever necessary to protect mental or physical health.

The significance of Vuitch , however, was to be short-lived. Roe v. Wade was already wending its way through the courts by the time of the decision. The day after they decided Vuitch , the justices voted to hear Roe .

The parties to Roe

Texan Norma McCorvey became pregnant for the third time in 1969. Struggling with drug and alcohol use, she previously relinquished responsibility for her first two children. She decided that she did not want to continue the pregnancy.

Texas law, however, allowed abortion only to save the patient’s life. With McCorvey six months pregnant, Texas lawyers Linda Coffee and Sarah Weddington filed a suit on her behalf in federal court under the pseudonym Jane Roe.

Henry Wade was a legendary and controversial district attorney with an impressive conviction rate, most famous for prosecuting Jack Ruby , who killed JFK’s assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald. Wade was, however, an odd foil for pro-choice activists. He did not aggressively prosecute illegal abortions and said little about them.

The lower court

A three-judge panel of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas struck down Texas’s abortion ban, finding it overbroad and locating the right to reproductive choice in the 9th and 14th Amendments. Citing Griswold , the court noted that the Constitution guarantees “the right of choice over events which, by their character and consequences, bear in a fundamental manner on the privacy of individuals.” While the federal court declared the Texas law unconstitutional, it declined to immediately block its enforcement, putting Roe v. Wade on a fast track to the Supreme Court.

Norma McCorvey gave birth to a girl, Shelley Lynn, on June 2, 1970, fifteen days before the federal district court issued its ruling. The baby was adopted when she was three days old. Her identity was not known to the public until 2021.

The Roe v. Wade oral argument

Sarah Weddington, who was just 26 years old when she stood before the justices of the Supreme Court on December 13, 1971, built her case for the constitutional right to abortion around the 9th and 14th Amendments, arguing that “meaningful” liberty must include the right to terminate an unwanted pregnancy.

Although the justices were largely receptive to Weddington’s points, Justice Byron White demanded to know whether the right to abortion extended right up to the moment of birth. After some hesitation, Weddington answered yes. Legal personhood began at birth, Weddington claimed. Until that moment, there should be an unfettered constitutional right to abortion.

After Weddington sat down, Texas Assistant Attorney General Jay Floyd stood to defend the state law. He began, inexplicably, with a sexist joke: “It’s an old joke, but when a man argues against two beautiful ladies like this, they are going to have the last word.” The bafflingly inappropriate comment was followed by three seconds of dead silence.

There was, however, one moment of wit in the argument. When Floyd argued that a woman who becomes pregnant has already made her choice, Justice Potter Stewart shot back, “Maybe she makes a choice when she decides to live in Texas!” The retort brought roars of laughter from the gallery.

Of particular note is how little the oral argument focused on the history of abortion laws during the founding or the post–Civil War era when the 14th Amendment was ratified. The justices focused instead on the biological realities of abortion and the text of the Constitution itself.

Also interesting: Justice Harry Blackmun, who would write the majority opinion in Roe v. Wade , spoke only twice during the oral argument. By contrast, Justice Thurgood Marshall spoke more than 10 times, Justices White and William Brennan more than 20 times, and Justice Stewart more than 30. (Perhaps this was because Blackmun was initially inclined to write a much more restrained opinion than he ultimately did.)

The Roe v. Wade opinion

The Supreme Court handed down its decision on January 22, 1973. Seven of the nine justices agreed that the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment — which says that no state shall “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” — implies a right to privacy. The majority seized upon Weddington’s definition of liberty, citing a series of prior cases indicating that the term “liberty” must be interpreted broadly in a free society.

The justices did, however, recognize that the state could place some limits on abortion if necessary to further a compelling state interest. The state’s ability to regulate increased as a pregnancy progressed. And after a fetus reached viability, the state could prohibit abortion, except when necessary to protect health or life.

Justices William Rehnquist and White dissented. Rehnquist argued that privacy, in the constitutional sense of illegal search and seizure, has nothing to do with abortion. In his view, since abortion bans implicate no fundamental rights, they must only have some rational basis, such as protecting a fetus. Foreshadowing the Dobbs decision in 2022, Rehnquist also declared that the only recognizable rights not explicitly listed in the Constitution are those with deep roots in the American legal tradition.

Doe v. Bolton (1973)

On the same day the Supreme Court decided Roe , it decided Doe v. Bolton , which challenged Georgia’s abortion ban. The Georgia law limited abortion to cases of documented rape, a severely disabled fetus, or a threat to life. Before the procedure, it was necessary to obtain the approval of a doctor, two additional consulting physicians, and a hospital committee. The law also permitted relatives to challenge the abortion decision. It was, in short, a burdensome process.

In another 7–2 vote, with Blackmun again writing for the majority, the Court ruled that although the rights identified in Roe are not absolute, Georgia’s restrictions violated the constitutional right to abortion. He noted that the law established hurdles that were far higher than those that had to be overcome for other surgical procedures.

White and Rehnquist again dissented.

Roe significantly reduced maternal mortality. A total of 39 women are known to have died from unsafe abortions in 1972, and this was almost certainly a drastic undercount. In 1975, there were only three such deaths. In 1965, eight years before Roe was decided, illegal abortion caused 17 percent of pregnancy-related deaths . In modern times, just 0.2 percent of people who undergo abortions even require hospitalization for complications.

It’s not entirely clear what effect Roe had on public attitudes toward abortion because public opinion was already in flux before the case was decided. In 1965, just 5 percent of Americans thought abortion should be legal for married people who simply didn’t want any more children. That number had risen to 36 percent by 1972, the year before Roe was decided. After Roe came down, pollsters began asking about abortion “for any reason,” and the polls show relative stability in the responses to that question since the mid-1970s.

The law after Roe v. Wade

Lingering resistance to abortion, particularly strong in certain parts of the country, led legislatures to test the decision’s boundaries. The Supreme Court issued many major abortion rulings up to the overturning of Roe v. Wade in the 2022 case Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization .

- In Planned Parenthood v. Danforth (1976), the justices blocked a law requiring spousal consent for abortion.

- Maher v. Roe (1979) permitted states to exclude abortion services from Medicaid coverage.

- Colautti v. Franklin (1979) struck down an unconstitutionally vague Pennsylvania law that required physicians to try to save the life of a fetus that might have been viable.

- In Harris v. McRae (1980), the Court upheld the Hyde Amendment , a federal law that proscribed federal funding for abortions except when necessary to preserve life or as a result of rape or incest.

- In L. v. Matheson (1981), the Court upheld a law requiring parental notification when the patient is a minor living with parents.

- In City of Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health (1983), the justices invalidated a wide range of limitations on abortion, such as a waiting period, parental consent without judicial bypass, and a ban on abortions outside of hospitals after the first trimester.

- Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (1986) struck down a law that required informed consent to include information about fetal development and alternatives to abortion.

- In Webster v. Reproductive Health Services (1989), Justice Rehnquist upheld rules requiring doctors to test for viability after 20 weeks and blocking state funding and state employee participation in abortion services.

- Rust v. Sullivan (1991) upheld a ban on certain federal funds being used for abortion referrals or counseling.

- Hill v. Colorado (2000) upheld a law limiting protest and leafletting close to an abortion clinic.

- Stenberg v. Carhart (2000) struck down Nebraska’s ban on the dilation and extraction abortion procedure.

- In Gonzales v. Carhart (2007), a slightly changed Court upheld a federal ban on the dilation and extraction procedure.

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey (1992)

One case in the period between Roe and Dobbs deserves special attention. Through the 1980s, abortion opponents demanded the appointment of Supreme Court justices who would overturn Roe . With the confirmation of Justices Anthony Kennedy, Sandra Day O’Connor, and David Souter, anti-abortion activists were confident they had the votes.

In 1988 and 1989, the Pennsylvania legislature adopted new abortion restrictions, including parental consent requirements, spousal notification, a waiting period, and an expanded informed consent process. Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania challenged the law, and many viewed the case as Roe ’s last stand — an opportunity for the Court to do away with the constitutional right to abortion.

In Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey , however, the new members of the Court disappointed anti-abortion advocates. While the Court replaced Roe ’s trimester-by-trimester doctrine with a weaker level of protection and upheld elements of the Pennsylvania law that did not unduly burden the right to abortion, the justices declined to overrule Roe . A plurality opinion authored by O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter explained that, while Supreme Court precedents are not eternal, there must be a compelling reason to abandon stare decisis — the notion that precedents should be upheld. The Court decided there was no adequate justification for overturning Roe , especially since Americans had arranged their lives around an expectation of control over their reproductive health, including having access to abortion. Casey also acknowledged the strong equality concerns that justify abortion rights, arguing that women cannot participate fully in the social and economic life of the nation if they are forced to continue unwanted pregnancies.

Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022)

In 2018, the Mississippi legislature banned abortions after 15 weeks of gestation, except in cases of narrowly defined medical emergency or severe fetal abnormality. The law was a challenge to both Roe and Casey . Jackson Woman’s Health Organization, the sole abortion provider in the state, contested the ban.

Long before Dobbs was decided, signs pointed to the Supreme Court’s intention to rescind the constitutional right to abortion. First, in a separate case that first appeared on the Court’s shadow docket , the justices allowed a Texas abortion ban that contravened Roe and Casey to remain in force. Then, in the weeks before Dobbs came down, a draft decision overturning Roe and Casey leaked out of the Court in an unprecedented breach of Court protocol.

The final decision was little changed from the leaked draft. Writing for the five-justice majority (with Chief Justice Roberts concurring only in the judgment), Justice Samuel Alito argued that the right to privacy is not specifically guaranteed anywhere in the Constitution. When unenumerated liberty rights exist — the right to raise your child as you see fit, for example — those rights must be “deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and tradition.” Reviewing the history of abortion restrictions in the early United States, Alito concluded that the right to abortion is not.

The opinion ignited a firestorm of controversy. Predictably so: Dobbs is arguably the first case to formally rescind a fundamental constitutional right. The opinion also failed to explain how its logic would not also result in the overturning of Griswold ’s right to contraception or a series of other cases that rely on the same logic as Roe . These include Lawrence v. Texas (2003), which invalidated laws criminalizing same-sex intimate sexual conduct, and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), which recognized the right to marriage for same-sex couples.

Also, for many Americans, Alito’s insistence that rights be “deeply rooted” in U.S. history revealed a broad discounting of historically marginalized communities, including women, people of color, and gay Americans. The only rights “deeply rooted” in our history are the ones that served the white, heterosexual men who dominated government at the time of the founding. While Casey had begun to address the equality dimensions of abortion rights, Dobbs moved in precisely the opposite direction, suggesting that non-majority groups must overcome special hurdles to have their rights recognized.

Abortion rights will now be defined on a state-by-state basis. Several state courts have ruled that their constitutions guarantee the right to abortion , whether because of explicit references to “privacy” or by relying on language that broadly protects personal autonomy. The Kansas Supreme Court , for example, has ruled that the constitution’s guarantee of “equal and inalienable natural rights” protects personal decision-making, self-determination, and bodily integrity. Other states have adopted an approach consistent with Roe , in which the right to privacy, including reproductive freedom, has been recognized as implied in the state constitution.

Following the Dobbs case, anti-abortion activists have proposed state constitutional amendments stating that nothing in the constitution protects abortion rights. In some cases, these measures seek to overrule their state courts’ interpretations of the constitution. In others, there has been no court decision regarding the constitutional right to abortion. Other states have, in contrast, moved to expand or cement abortion rights, including through constitutional amendments.

Dobbs also leaves a long list of unanswered practical questions. Can states ban women from traveling to obtain an abortion? How will they police the importation and use of abortion drugs? How will state courts handle the slew of “trigger laws” — state anti-abortion statutes designed to come into effect upon the overturning of Roe ? Just as Roe set off years of legal uncertainty over the precise boundaries of abortion rights, Dobbs has launched a long period of uncertainty over states’ power to restrict abortion in the absence of those rights.

The current Court

- Chief Justice John Roberts , during his time as a lawyer for the George W. Bush administration, wrote that Roe has “ no support in the text, structure, or history of the Constitution.” In his Dobbs concurrence, however, Roberts favored preserving a more limited constitutional right to abortion, without specifying how far it would extend. “Surely we should adhere closely to principles of judicial restraint here, where the broader path the Court chooses entails repudiating a constitutional right we have not only previously recognized, but also expressly reaffirmed applying the doctrine of stare decisis .”

- Justice Clarence Thomas , who was in the Dobbs majority, has written that Roe was “grievously wrong for many reasons, but the most fundamental is that its core holding — that the Constitution protects a woman’s right to abort her unborn child — finds no support in the text of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

- Justice Samuel Alito complained as a young lawyer in the Reagan administration about “the courts’ refusal to allow breathing room for reasonable state regulation” of abortion. In a job application, he wrote, “I personally believe very strongly that the Constitution does not protect a right to an abortion.” As the authority of the majority opinion in Dobbs , he wrote that “ Roe was . . . egregiously wrong and on a collision course with the Constitution from the day it was decided.”

- Justice Neil Gorsuch , who was in the Dobbs majority, has said and written less on abortion than many other justices, but during his confirmation hearing, he noted that Roe was “a precedent of the U.S. Supreme Court” and added, “once a case is settled, that adds to the determinacy of the law.”

- Justice Amy Coney Barrett added her name to a 2006 ad calling for Roe to be overturned and suggested that the possibility of adoption might obviate the need for abortion rights .

- Justice Brett Kavanaugh , in 2017, proclaimed his admiration of former justice Rehnquist’s Roe dissent, noting that his views about unenumerated rights were “successful in stemming the general tide of freewheeling judicial creation of unenumerated rights that were not rooted in the nation’s history and tradition.”

- Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson repeatedly described Roe as “settled law” in her confirmation hearings. In the same hearings, when asked when human life begins, she replied simply, “ I don’t know .”

- Justice Sonia Sotomayor has focused much of her writing about abortion on the cost that bans impose on those who are economically disadvantaged. Objecting to the Court’s decision to allow a Texas abortion ban to stand, Sotomayor wrote, “Those without the ability to make this journey [to a state allowing abortion], whether due to lack of money or childcare or employment flexibility or the myriad other constraints that shape people’s day-to-day lives, may be forced to carry to term against their wishes or resort to dangerous methods of self-help .” The Dobbs dissent, authored by Justice Breyer and joined by Justices Sotomayor and Kagan, continued that theme of disempowerment, lamenting the end of an era in which “respecting a woman as an autonomous being, and granting her full equality, meant giving her substantial choice over this most personal and most consequential of all life decisions.”

- Justice Elena Kagan has a significant and slightly complicated record on abortion. As a lawyer in the Clinton administration, she wrote a memo recommending that the president sign a ban on “partial birth abortion” if it contained an exception in cases of serious risk to health. As a justice, however, Kagan has voted consistently against restrictions on abortion. She called a recent Texas abortion ban “patently unconstitutional” and dissented forcefully in Dobbs .

Notable past justices

- Justice Stephen Breyer : “Millions of Americans believe that life begins at conception and consequently that an abortion is akin to causing the death of an innocent child . . . Other millions fear that a law that forbids abortion would condemn many American women to lives that lack dignity, depriving them of equal liberty and leading those with least resources to undergo illegal abortions with the attendant risks of death and suffering.”

- Chief Justice Warren Burger : “The Constitution does not compel a state to fine-tune its statutes so as to encourage or facilitate abortions. To the contrary, state action ‘encouraging childbirth except in the most urgent circumstances’ is ‘rationally related to the legitimate governmental objective of protecting potential life.’”

- Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg : “ Roe v. Wade sparked public opposition and academic criticism, in part, I believe, because the Court ventured too far in the change it ordered and presented an incomplete justification for its action.”

- Justice Sandra Day O’Connor : “The Roe framework . . . is clearly on a collision course with itself.”

- Chief Justice William Rehnquist : “We do not see why the state’s interest in protecting human life should come into existence only at the point of viability .”

- Justice Antonin Scalia : “We should get out of this area [abortion law], where we have no right to be, and where we do neither ourselves nor the country any good by remaining.”

- Justice Byron White : “The Court apparently values the convenience of the pregnant mother more than the continued existence of the life or potential life that she carries.”

- Justice William J. Brennan Jr. : “If the right to privacy means anything, it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwanted government intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision to bear or beget a child.”

- Justice Anthony Kennedy : “Where it has a rational basis to act, and it does not impose an undue burden, the State may use its regulatory power to bar certain procedures and substitute others, all in furtherance of its legitimate interests in regulating the medical profession in order to promote respect for life, including life of the unborn.”

- Justice David Souter : “I have not got any agenda on what should be done with Roe v. Wade , if that case is brought before me.”

Government Classification and the Mar-a-Lago Documents

Understanding how the classification system works is critical to understanding Trump’s culpability — legal and otherwise.

What Gifts Must Supreme Court Justices Disclose?

There are significant loopholes in the rules that apply to the high court.

Myths and Realities: Understanding Recent Trends in Violent Crime

The recent rise in crime is extraordinarily complex. Policymakers and the public should not jump to conclusions or expect easy answers.

Informed citizens are democracy’s best defense

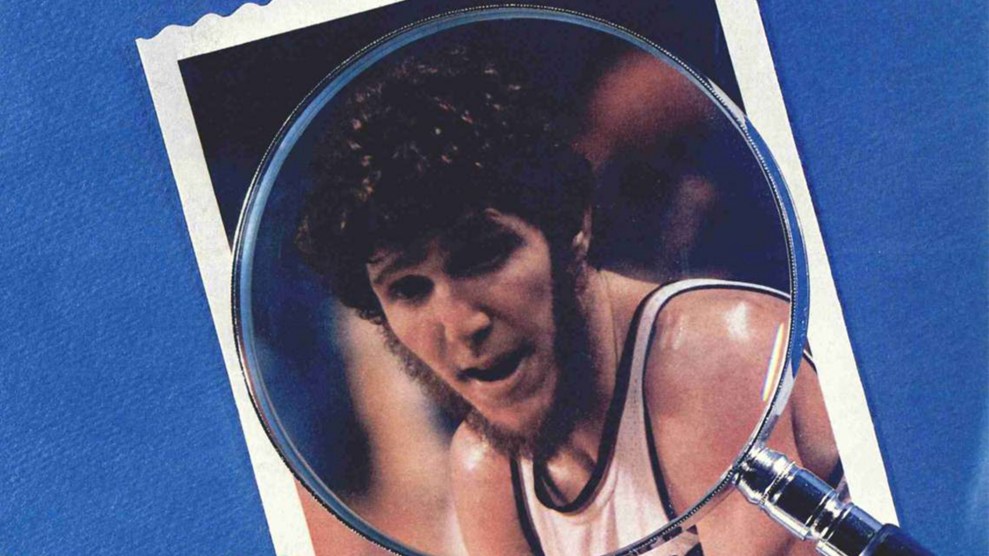

The Most Important Study in the Abortion Debate

Researchers rigorously tested the persistent notion that abortion wounds the women who seek it.

The demographer Diana Greene Foster was in Orlando last month, preparing for the end of Roe v. Wade , when Politico published a leaked draft of a majority Supreme Court opinion striking down the landmark ruling. The opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, would revoke the constitutional right to abortion and thus give states the ability to ban the medical procedure.

Foster, the director of the Bixby Population Sciences Research Unit at UC San Francisco, was at a meeting of abortion providers, seeking their help recruiting people for a new study . And she was racing against time. She wanted to look, she told me, “at the last person served in, say, Nebraska, compared to the first person turned away in Nebraska.” Nearly two dozen red and purple states are expected to enact stringent limits or even bans on abortion as soon as the Supreme Court strikes down Roe v. Wade , as it is poised to do. Foster intends to study women with unwanted pregnancies just before and just after the right to an abortion vanishes.

Read: When a right becomes a privilege

When Alito’s draft surfaced, Foster told me, “I was struck by how little it considered the people who would be affected. The experience of someone who’s pregnant when they do not want to be and what happens to their life is absolutely not considered in that document.” Foster’s earlier work provides detailed insight into what does happen. The landmark Turnaway Study , which she led, is a crystal ball into our post- Roe future and, I would argue, the single most important piece of academic research in American life at this moment.

The legal and political debate about abortion in recent decades has tended to focus more on the rights and experience of embryos and fetuses than the people who gestate them. And some commentators—including ones seated on the Supreme Court—have speculated that termination is not just a cruel convenience, but one that harms women too . Foster and her colleagues rigorously tested that notion. Their research demonstrates that, in general, abortion does not wound women physically, psychologically, or financially. Carrying an unwanted pregnancy to term does.

In a 2007 decision , Gonzales v. Carhart , the Supreme Court upheld a ban on one specific, uncommon abortion procedure. In his majority opinion , Justice Anthony Kennedy ventured a guess about abortion’s effect on women’s lives: “While we find no reliable data to measure the phenomenon, it seems unexceptionable to conclude some women come to regret their choice to abort the infant life they once created and sustained,” he wrote. “Severe depression and loss of esteem can follow.”

Was that really true? Activists insisted so, but social scientists were not sure . Indeed, they were not sure about a lot of things when it came to the effect of the termination of a pregnancy on a person’s life. Many papers compared individuals who had an abortion with people who carried a pregnancy to term. The problem is that those are two different groups of people; to state the obvious, most people seeking an abortion are experiencing an unplanned pregnancy, while a majority of people carrying to term intended to get pregnant.

Foster and her co-authors figured out a way to isolate the impact of abortion itself. Nearly all states bar the procedure after a certain gestational age or after the point that a fetus is considered viable outside the womb . The researchers could compare people who were “turned away” by a provider because they were too far along with people who had an abortion at the same clinics. (They did not include people who ended a pregnancy for medical reasons.) The women who got an abortion would be similar, in terms of demographics and socioeconomics, to those who were turned away; what would separate the two groups was only that some women got to the clinic on time, and some didn’t.

In time, 30 abortion providers—ones that had the latest gestational limit of any clinic within 150 miles, meaning that a person could not easily access an abortion if they were turned away—agreed to work with the researchers. They recruited nearly 1,000 women to be interviewed every six months for five years. The findings were voluminous, resulting in 50 publications and counting. They were also clear. Kennedy’s speculation was wrong: Women, as a general point, do not regret having an abortion at all.

Researchers found, among other things, that women who were denied abortions were more likely to end up living in poverty. They had worse credit scores and, even years later, were more likely to not have enough money for the basics, such as food and gas. They were more likely to be unemployed. They were more likely to go through bankruptcy or eviction. “The two groups were economically the same when they sought an abortion,” Foster told me. “One became poorer.”

Read: The calamity of unwanted motherhood

In addition, those denied a termination were more likely to be with a partner who abused them. They were more likely to end up as a single parent. They had more trouble bonding with their infants, were less likely to agree with the statement “I feel happy when my child laughs or smiles,” and were more likely to say they “feel trapped as a mother.” They experienced more anxiety and had lower self-esteem, though those effects faded in time. They were half as likely to be in a “very good” romantic relationship at two years. They were less likely to have “aspirational” life plans.

Their bodies were different too. The ones denied an abortion were in worse health, experiencing more hypertension and chronic pain. None of the women who had an abortion died from it. This is unsurprising; other research shows that the procedure has extremely low complication rates , as well as no known negative health or fertility effects . Yet in the Turnaway sample, pregnancy ended up killing two of the women who wanted a termination and did not get one.

The Turnaway Study also showed that abortion is a choice that women often make in order to take care of their family. Most of the women seeking an abortion were already mothers. In the years after they terminated a pregnancy, their kids were better off; they were more likely to hit their developmental milestones and less likely to live in poverty. Moreover, many women who had an abortion went on to have more children. Those pregnancies were much more likely to be planned, and those kids had better outcomes too.

The interviews made clear that women, far from taking a casual view of abortion, took the decision seriously. Most reported using contraception when they got pregnant, and most of the people who sought an abortion after their state’s limit simply did not realize they were pregnant until it was too late. (Many women have irregular periods, do not experience morning sickness, and do not feel fetal movement until late in the second trimester.) The women gave nuanced, compelling reasons for wanting to end their pregnancies.

Afterward, nearly all said that termination had been the right decision. At five years, only 14 percent felt any sadness about having an abortion; two in three ended up having no or very few emotions about it at all. “Relief” was the most common feeling, and an abiding one.

From the May 2022 issue: The future of abortion in a post- Roe America

The policy impact of the Turnaway research has been significant, even though it was published during a period when states have been restricting abortion access. In 2018, the Iowa Supreme Court struck down a law requiring a 72-hour waiting period between when a person seeks and has an abortion, noting that “the vast majority of abortion patients do not regret the procedure, even years later, and instead feel relief and acceptance”—a Turnaway finding. That same finding was cited by members of Chile’s constitutional court as they allowed for the decriminalization of abortion in certain circumstances.

Yet the research has not swayed many people who advocate for abortion bans, believing that life begins at conception and that the law must prioritize the needs of the fetus. Other activists have argued that Turnaway is methodologically flawed; some women approached in the clinic waiting room declined to participate, and not all participating women completed all interviews . “The women who anticipate and experience the most negative reactions to abortion are the least likely to want to participate in interviews,” the activist David Reardon argued in a 2018 article in a Catholic Medical Association journal.

Still, four dozen papers analyzing the Turnaway Study’s findings have been published in peer-reviewed journals; the research is “the gold standard,” Emily M. Johnston, an Urban Institute health-policy expert who wasn’t involved with the project, told me. In the trajectories of women who received an abortion and those who were denied one, “we can understand the impact of abortion on women’s lives,” Foster told me. “They don’t have to represent all women seeking abortion for the findings to be valid.” And her work has been buttressed by other surveys, showing that women fear the repercussions of unplanned pregnancies for good reason and do not tend to regret having a termination. “Among the women we spoke with, they did not regret either choice,” whether that was having an abortion or carrying to term, Johnston told me. “These women were thinking about their desires for themselves, but also were thinking very thoughtfully about what kind of life they could provide for a child.”

The Turnaway study , for Foster, underscored that nobody needs the government to decide whether they need an abortion. If and when America’s highest court overturns Roe , though, an estimated 34 million women of reproductive age will lose some or all access to the procedure in the state where they live. Some people will travel to an out-of-state clinic to terminate a pregnancy; some will get pills by mail to manage their abortions at home; some will “try and do things that are less safe,” as Foster put it. Many will carry to term: The Guttmacher Institute has estimated that there will be roughly 100,000 fewer legal abortions per year post- Roe . “The question now is who is able to circumvent the law, what that costs, and who suffers from these bans,” Foster told me. “The burden of this will be disproportionately put on people who are least able to support a pregnancy and to support a child.”

Ellen Gruber Garvey: I helped women get abortions in pre- Roe America

Foster said that there is a lot we still do not know about how the end of Roe might alter the course of people’s lives—the topic of her new research. “In the Turnaway Study, people were too late to get an abortion, but they didn’t have to feel like the police were going to knock on their door,” she told me. “Now, if you’re able to find an abortion somewhere and you have a complication, do you get health care? Do you seek health care out if you’re having a miscarriage, or are you too scared? If you’re going to travel across state lines, can you tell your mother or your boss what you’re doing?”

In addition, she said that she was uncertain about the role that abortion funds —local, on-the-ground organizations that help people find, travel to, and pay for terminations—might play. “We really don’t know who is calling these hotlines,” she said. “When people call, what support do they need? What is enough, and who falls through the cracks?” She added that many people are unaware that such services exist, and might have trouble accessing them.

People are resourceful when seeking a termination and resilient when denied an abortion, Foster told me. But looking into the post- Roe future, she predicted, “There’s going to be some widespread and scary consequences just from the fact that we’ve made this common health-care practice against the law.” Foster, to her dismay, is about to have a lot more research to do.

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 14 June 2019

“Regardless, you are not the first woman”: an illustrative case study of contextual risk factors impacting sexual and reproductive health and rights in Nicaragua

- Samantha M. Luffy 1 ,

- Dabney P. Evans ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2201-5655 1 &

- Roger W. Rochat 1

BMC Women's Health volume 19 , Article number: 76 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

4 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Rape, unintended pregnancy, and abortion are among the most controversial and stigmatized topics facing sexual and reproductive health researchers, advocates, and the public today. Over the past three decades, public health practicioners and human rights advocates have made great strides to advance our understanding of sexual and reproductive rights and how they should be protected. The overall aim of the study was to understand young women’s personal experiences of unintended pregnancy in the context of Nicaragua’s repressive legal and sociocultural landscape. Ten in-depth interviews (IDIs) were conducted with women ages 16–23 in a city in North Central Nicaragua, from June to July 2014.

Case presentation

This case study focuses on the story of a 19-year-old Nicaraguan woman who was raped, became pregnant, and almost died from complications resulting from an unsafe abortion. Her case, detailed under the pseudonym Ana Maria, presents unique challenges related to the fulfillment of sexual and reproductive rights due to the restrictive social norms related to sexual health, ubiquitous violence against women (VAW) and the total ban on abortion in Nicaragua. The case also provides a useful lens through which to examine individual sexual and reproductive health (SRH) experiences, particularly those of rape, unintended pregnancy, and unsafe abortion; this in-depth analysis identifies the contextual risk factors that contributed to Ana Maria’s experience.

Conclusions

Far too many women experience their sexuality in the context of individual and structural violence. Ana Maria’s case provides several important lessons for the realization of sexual and reproductive health and rights in countries with restrictive legal policies and conservative cultural norms around sexuality. Ana Maria’s experience demonstrates that an individual’s health decisions are not made in isolation, free from the influence of social norms and national laws. We present an overview of the key risk and contextual factors that contributed to Ana Maria’s experience of violence, unintended pregnancy, and unsafe abortion.

Peer Review reports

Rape, unintended pregnancy, and abortion are among the most controversial and stigmatized topics facing sexual and reproductive health researchers, advocates, and the public today. Over the past three decades, however, the international community, States, and advocates have made great strides to advance our understanding of sexual and reproductive rights and how they can be protected at the national and international levels. The 1994 Cairo Declaration began this process by including sexual health under the umbrella of reproductive health and recognized the impact of violence on an individual’s sexual and reproductive health (SRH) decision-making. [ 1 ] One year later, the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action specifically addressed the issues of unintended pregnancy and abortion by emphasizing that improved family planning services should be the main method by which unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions are prevented. [ 2 ]

A recent World Health Organization (WHO) report on the relationships between sexual health, human rights, and State’s laws sets the foundation for our contemporary understanding of these issues. The 2015 report describes sexual health as, “a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality.” [ 3 ] That state includes control over one’s fertility via access to health services such as abortion; it also includes the right to enjoy sexual experiences free from coercion, discrimination, and violence. [ 3 ] Whether experienced alone or in combination, rape, unintended pregnancy, and abortion are important SRH issues on which public health can and should intervene.

In the public health field, case studies provide a useful lens through which to examine individual women’s sexual and reproductive health experiences, particularly those of rape, unintended pregnancy, and unsafe abortion; an in-depth analysis of these personal experiences can identify contextual risk factors and missed opportunities for public health rights-based intervention. This type of analysis is especially cogent when legal policies and social factors, such as gender inequality, may influence one’s SRH decision-making process. On an individual level, bearing witness to women’s stories through in-depth interviews helps document their lived experience; surveying these experiences within the context of laws related to SRH provides important evidence for the impact of such policies on women’s well-being.

We present the case of a 19-year-old Nicaraguan woman who was raped, became pregnant, and almost died from complications resulting from an unsafe abortion. Her complex experience of violence, unintended pregnancy, and unsafe abortion represent a series of contextual factors and missed opportunities for public health and human rights intervention. Ana Maria’s story, told through the use of a pseudonym, takes place in a city located in North Central Nicaragua – a country that presents unique challenges related to its citizens’ fulfillment of their sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Violence against women in Nicaragua

Along with 189 States, Nicaragua is a party to the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, which includes State obligations to protect and promote the health and well-being of Nicaraguan women. [ 4 ] As defined by human rights documents, the right to health includes access to health care services, as well as provisions for the underlying social determinants of health, such as personal experiences of structural violence. [ 5 ]

In the Nicaraguan context, political and sociocultural institutions support unequal power relations between genders. [ 6 ] Machismo is one such form of structural violence that perpetuates gender inequality and has been identified as a barrier to SRH promotion in Nicaragua. [ 7 , 8 ] The term ‘ machismo ’ is most commonly used to describe male behaviors that are sexist, hyper masculine, chauvinistic, or violent towards women. [ 9 ] These behaviors often legitimize the patriarchy, reinforce traditional gender roles, and are used to limit or control the actions of women, who are often perceived as inferior. [ 10 ]

The vast majority (89.7%) of Nicaraguan women have experienced some form of gender-based violence during their lifetime, which poses a serious public health problem. The latest population-based Demographic and Health Survey showed that at least 50% of Nicaraguan women surveyed had experienced either verbal/psychological, physical, or sexual violenceduring their lifetime. An additional 29.3% of women reported having experienced both physical and sexual violence at least once, while another 10.4% reported having experienced all three types of violence. [ 11 ]

In 2012, Nicaragua joined a host of other Central and South American countries that have implemented laws to eliminate all forms of violence against women VAW, including rape and femicide. [ 12 ] Nicaragua’s federal law against VAW, Law 779, intends to eradicate such violence in both public and private spheres. [ 13 ] On paper, Law 779 guarantees women freedom from violence and discrimination, but it is unclear if the law is being adequately enforced; it has been reported that some women believe VAW has increased since the law’s implementation. [ 14 ]

Before Law 779, violent acts like rape, particularly of young women ages 15–24, were endemic in Nicaragua. Approximately two-thirds of rapes reported in Nicaragua between 1998 and 2008 were committed against girls under 17 years of age; most of these acts were committed by a known acquaintance. [ 15 ] Due to a lack of reporting and to culturally propagated stigma regarding rape, no reliable data suggest that Law 779 has been effective in reducing the incidence of rape in Nicaragua. For women who wish to terminate a pregnancy that resulted from rape, access to abortion services is vital, yet completely illegal. [ 16 ] In contrast, technical guidance from the WHO recommends that health systems include access to safe abortion services for women who experience unintended pregnancy or become pregnant as a result of rape. [ 17 ]

Family planning and unintended pregnancy in Nicaragua

Like violence, unintended pregnancies -- not only those that result from rape -- pose a widespread public health problem in Nicaragua. National data suggest that 65% of pregnancies among women ages 15–29 were unintended. [ 11 ] Oftentimes, unintended pregnancy results from a complex combination of social determinants of health including: low socioeconomic status (SES), low education level, lack of access to adequate reproductive health care, and restrictive reproductive rights laws. [ 18 , 19 , 20 ] Nicaraguan women of low SES with limited access to family planning services are at an increased risk of depression, violence, and unemployment due to an unintended pregnancy. [ 19 , 20 ]

The UN Committee on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) has expressed concern regarding the lack of comprehensive sexual education programs, as well as inadequate family planning services, and high rates of unintended pregnancy throughout Nicaragua. [ 21 ] Due to a lack of sexual education, Nicaraguan adolescents, if they use contraceptives like male condoms or oral contraceptive pills, often do so inconsistently or incorrectly. [ 22 ]

Deeply rooted cultural stigma surrounding unmarried women’s sexual behavior contributes to the harsh criticism of young women in Nicaragua that use a method of family planning or engage in sexual relationships outside of a committed union. [ 18 , 22 ] Also, young women who are not in a formal union may experience unplanned sex (consensual or nonconsensual) and are unlikely to be using contraception, which further increases the risk of unintended pregnancy. [ 22 ] These social and cultural factors, in conjunction with restrictive reproductive rights laws, may contribute to a high incidence of unintended pregnancy among young Nicaraguan women.

The total ban on abortion in Nicaragua

Compounding the economic, social, and emotional burden of unintended pregnancy on women’s lives is the current prohibition of abortion in Nicaragua. In 2006, the National Assembly unanimously passed a law to criminalize abortion, which had been legal in Nicaragua since the late 1800s. [ 20 ] Researchers often refer to this law as the “total ban” on abortion. [ 20 , 23 ] The total ban prohibits the termination of a pregnancy in all cases, including incest, rape, fetal anomaly, and danger to the life of the woman. Laws that prohibit medical procedures are, by definition, barriers to access; equitable access to safe medical services is a critical element of the right to health. [ 3 , 5 ] The UN Committee on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR) has also recognized the discriminatory and harmful nature of criminalizing medical procedures that only women undergo. [ 24 ]

Nicaragua is one of the few countries in the world to completely ban abortion in all circumstances. In States where illegal, abortion does not stop. Instead, women are forced to obtain abortions from unskilled providers in conditions that are often unsafe and unhygienic. [ 25 ] Unsafe abortions are among the main preventable causes of maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide and can be avoided through decriminalization of such services. [ 26 ]

The Nicaraguan ban includes serious legal penalties for women who obtain illegal abortions, as well as for the medical professionals who perform them, which can have profound negative effects on women’s health. [ 20 , 23 ] Women who need or want an abortion face not only the health risks that accompany an unsafe procedure, but additional criminal penalties. The total ban on abortion violates the human rights of both health care providers and women nationwide, as well as the confidentiality inherent in the patient-provider relationship. [ 20 ] It also results in a ‘chilling effect’ where health care providers are unwilling to provide both abortion and postabortion care (PAC) services for fear of prosecution. [ 20 ]

In response to the negative impacts of the total ban on maternal morbidity and mortality in Nicaragua, as well as detrimental effects on women’s physical, mental, and emotional health, CEDAW has recommended that the Nicaraguan government review the total ban and remove the punitive measures imposed on women who have abortions. [ 21 ] While the Nicaraguan government may not view abortion as a human right per se, women should not face morbidity or mortality as a result of illegal or unsafe abortion. [ 27 ]

Criminalizing abortion also increases stigma around this issue and significantly reduces people’s willingness to speak openly about abortion and related SRH services. Qualitative research conducted in Nicaragua suggests that women who have had unsafe abortions rarely discuss their experiences openly due to the illegal and highly stigmatized nature of such procedures. [ 18 ] Therefore, the overall aim of the study was to better understand young women’s personal experiences of unintended pregnancy in the context of Nicaragua’s repressive legal and sociocultural landscape. Ten in-depth interviews (IDIs) were conducted with women ages 16–23 in a city in North Central Nicaragua from June to July 2014. This private method of data collection allowed for the detailed exploration of each young woman’s personal experience with an unintended pregnancy, including the decision-making process she went through regarding how to respond to the pregnancy. Given the personal nature of this experience – including the criminalization and stigmatization of women who obtain abortions – IDIs allowed the participants to share intimate details and information that would be inappropriate or dangerous to share in a group setting. One case, presented here, emerged as salient for understanding the intersections of violence, unintended pregnancy, and abortion – and the missed opportunities for rights-based public health intervention.

Emory University’s Institutional Review Board ruled the study exempt from review because it did not meet the definition of “research” with human subjects as set forth in Emory policies and procedures and federal rules. Nevertheless, procedural steps were taken to protect the rights of participants and ensure confidentiality throughout data collection, management, and analysis. The first author reviewed the informed consent form in Spanish with each participant and then acquired each participant’s signature and verbal informed consent before the IDIs were conducted. The investigators developed a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions and piloted the guide twice to improve the cultural appropriateness of the script (Additional file 1 ). The investigators also collaborated with local partners to design and implement the research according to local cultural and social norms. Due to the contentious topics discussed in this study, these collaborators prefer to not be mentioned by name. Interviews were conducted in Spanish in a private location and audio taped to protect the participants’ privacy. Recordings were transcribed verbatim and transcripts were coded and analyzed using MAXQDA11 software (VERBI GmbH, Berlin, Germany).

Initially, participants were recruited for interviews through purposive sampling of individuals who had disclosed a personal experience with unintended pregnancy during focus group discussions (FGDs) conducted in a larger parent study. At the end of each interview, participants were asked to refer other young women they knew who may have experienced an unintended pregnancy to participate in an interview. This form of respondent-driven sampling created a network of participants with a wide variety of experiences with unintended pregnancy. Of the ten interviewees, two had experienced unintended pregnancy as a result of rape, though both used the phrase “ sexo no consensual ” or “nonconsensual sex” in lieu of “ violación, ” the Spanish word for rape. One of these women shared her personal experience receiving an unsafe abortion to terminate an unintended pregnancy that had resulted from rape. Her story, shared under the use of the pseudonym Ana Maria, is presented here in order to:

Illustrate the harmful impact of restrictive abortion laws on the health and well-being of women – especially those who do not have access to abortion in the case of rape; and

Exemplify the nexus of contextual risk factors that impact women’s SRH decision-making, such as conservative social norms and restrictive legal policies.

Through thorough analysis, we examine the impact of these contextual factors that impacted Ana Maria’s experience.

When she was 19, Ana Maria was raped by her godfather, a close friend of her family.

In an in-depth interview, Ana Maria described enduring incessant verbal harassment from her godfather – her elder brother’s best friend – in the months before the assault. He constantly called and texted her cell phone in order to interrogate her about platonic relationships with other men in town and to convince her to spend time alone with him. Even though he was married with children and she repeatedly dismissed his advances, he continued to engage in this form of psychological violence with his goddaughter. Ana Maria described eventually “giving in” and meeting him – not knowing that this encounter would result in her forcible rape.

The disclosure of Ana Maria’s rape during her interview was spontaneous and unexpected. Ana Maria was unwilling to disclose explicit details of the sexual assault. Instead, she stated multiple times that the sexual contact was nonconsensual and she did not want to have sex with him. When asked if she told anyone about this experience, she said no because she did not want others to judge her for what had happened.

Approximately a month of scared silence after she was raped, Ana Maria noticed that her period had not come. Nervous, she bought a pregnancy test from a local pharmacy. To her dismay, the test was positive. In order to confirm the pregnancy, she traveled alone to the nearby health center in her town to obtain a blood test. Again, the test was positive. She had never been pregnant before and she was terrified. In the midst of her fear, she shared the results with her rapist, her godfather.

His response: get an abortion. He did not want to lose his wife and children if they found out about the pregnancy.

Other than their illegal nature, Ana Maria knew nothing about abortions – where to get one, how it was done, what it felt like. She asked her neighbors to explain it to her. They said “it was worse than having a baby and [experiencing] childbirth.”

Though Ana Maria did not want to get the abortion, her godfather continued to pressure her to get the procedure saying, “Regardless, you must get the abortion… you are not the first woman to have ever had one.” Similar to the emotional violence before he raped her, he called and texted Ana Maria every day telling her to, “do it as fast as you can.” He forbade her from telling anyone about the pregnancy and Ana Maria didn’t feel like she had anyone to confide in about the situation. She worried about people judging her for getting pregnant outside of a committed relationship – even though she was raped. Ana Maria described this difficult time:

“When he started to pressure me [to get the abortion], I felt alone. I did not have enough trust in anyone to tell them [what had happened] because… if I had had enough trust in someone, I know that they would not have let me do it. If I had been given advice, they would have said, ‘No, do not do it,’ but I did not have anyone and I felt so depressed. What made it worse, I couldn’t sleep; I could not sleep [because I was] thinking of everything he had told me. At night, I would remember how it all started and I do not know what he did to find that money, but he gave me the money to get the abortion.”

Her godfather gave her 3000 Córdobas (approximately USD112 at the time) and put her on a public bus, alone. He had arranged for her to receive the abortion from an older woman that practiced “natural medicine” in a nearby city. When Ana Maria arrived at the woman’s home, she was instructed to remove her pants and underwear and lie on a bed. Ana Maria did not receive any medication before the woman inserted a “device like the one used for a Papanicolau… and then another device like an iron rod” into her vagina.

After describing these devices, Ana Maria made a jerking motion back and forth with her arm to imitate the movement the woman used to perform the abortion.

Once it was over, the woman gave Ana Maria an injection of an unknown substance and told her that she would pass a few blood clots over the next few days. That night, however, Ana Maria’s condition worsened; she became feverish, felt disoriented, and began to pass dark, fetid clots of blood. She described the pain she experienced throughout the ordeal:

“I felt so much pain when they took her out of me. I felt pain when the blood was leaving my body and when I had the fever. I felt a terrible pain that only I suffered. I am [a] different [person] now because of those pains.”

Ana Maria was too afraid to tell her family about the assault or the abortion because she was uncertain how they would react. She was even more terrified of the potential legal repercussions that she could face for violating the total ban on abortion. Within a few days of the abortion, though, Ana Maria’s brother heard rumors of his sister’s situation from neighbors “in the street” and confronted her about what had happened. At first, Ana Maria denied that she had had an abortion, but her brother continued to ask for the truth. Though she was nervous, Ana Maria eventually told her brother everything that had happened – from her godfather’s incessant verbal harassment, to the rape, to the unsafe abortion she was forced to get.

Afraid for his sister’s life, Ana Maria’s brother contacted a local nurse who discreetly provides postabortion care (PAC) to women experiencing complications from unsafe abortion and other obstetric emergencies. This nurse is locally known to be one of the few health care providers who provide PAC despite many other providers’ fear of prosecution under the total ban. The nurse recommended that Ana Maria come to the hospital immediately.

Ana Maria spent almost two weeks as an inpatient at the only hospital in the region. She had become septic as a result of what she described as a “perforated uterus,” a common complication from unsafe abortion. [ 28 ] Upon her initial examination, the nurse was afraid that her uterus could not be repaired because the infection was so severe. Fortunately, the medical team administered an ultrasound, removed infected blood clots, and completed uterine surgery to repair the damage from the unsafe abortion. At the request of the gynecologist taking care of her, Ana Maria received the one-month contraceptive hormonal injection before being discharged. At the time of the interview, Ana Maria had not received the next month’s injection because she “didn’t have any use for a man.”

As a result of this experience, Ana Maria reported feelings of depression, isolation, and recurring dreams about a little girl, which she described in this way:

“After I was discharged, I always dreamt of a little girl and that she was mine, standing in my doorway and when I awoke, I couldn’t find her. I looked for her in my bed but she wasn’t there. And this has tormented me because, it’s true: I am the girl that committed this error, but the little girl was not at fault. He pressured me so strongly to get the abortion, so I did.”

Ana Maria had the same recurring dream every night for more than two weeks and she continued to feel depressed weeks after leaving the hospital. One of the sources of her depression was the isolation she felt because there was no one with whom she could share this experience.

According to Ana Maria, she longs to have other people to talk to about her experience – particularly those who may have had similar experiences. She also expressed a desire to pursue a law degree so that she can have a career in local government.

Discussion and conclusions

Ana Maria’s case provides insight into the contextual factors effecting her ability to realize her sexual and reproductive health and rights in Nicaragua where restrictive legal policies and conservative cultural norms around sexuality abound. These contextual risk factors include social norms related to sexual health, laws targeting VAW, and the criminalization of abortion.

Social norms related to sexual health

The fundamental relationship between structural inequality and sexual and reproductive rights has been duly noted; gender inequality, in particular, must be addressed in order to fulfill sexual rights for women. [ 29 ] As in many cases in Nicaragua, the fact that Ana Maria’s first sexual experience was nonconsensual and was initiated by an older male and trusted family friend highlights the uneven power relations between men and women in Nicaraguan culture, which propagate high instances of VAW and sexual assault. In a patriarchal society where machismo and gender inequality run rampant, women’s sexuality is further constrained by the stigmatization of sexual health and a culture of violence that limits women’s autonomy. The compound stigma surrounding sexual health in general, and rape in particular, negatively impacted Ana Maria’s knowledge and ability to access mental health and SRH services, including emergency contraception and post-rape care, which may have assisted her immediately following her assault. Before her brother intervened, Ana Maria’s fear of judgment and legal repercussions also prevented her from seeking PAC, which was necessary to save her life.

Comprehensive sexual education is a primary way to challenge these social norms and widespread stigma surrounding sexuality and SRH services, such as contraception and PAC, at the population level. Such education might have mitigated Ana Maria’s experience of unintended pregnancy through the provision of advance knowledge of emergency contraception and medical options in the event of pregnancy. CEDAW has recognized this missed opportunity for public health intervention in Nicaragua, and recommends sexual education as a means of addressing stigma related to sexuality, decreasing unintended pregnancy, and increasing the acceptability and use of family planning services throughout the country. [ 21 ] Furthermore, the lack of adolescent-friendly sexual education and SRH services symbolizes a social reluctance to acknowledge the reality that young people have sex. [ 30 ] Such ignorance results in a lack of information on healthy relationships and human reproduction, as well as experiences of unintended pregnancy, early motherhood, and unsafe abortion. Exposure to this type of information may have improved Ana Maria’s ability to protect herself, mitigated the impact of Nicaragua’s pervasive misogyny on her decision making, and lessened the influence of her godfather’s coercion before her experiences of rape and unsafe abortion.

Individual and structural violence against women

Though we do not know explicit details of Ana Maria’s rape, the act of rape is inherently violent. The assault violated her right to enjoy sexual experiences free from coercion and violence. [ 3 ] To further constrain her sexual and reproductive rights, Ana Maria’s experience of rape resulted in an unintended pregnancy and an unsafe abortion that she was pressured into undergoing. Along with physical sequelae as a result of the procedure, she also expressed feelings of depression and isolation, which are common symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). [ 31 ] These mental health consequences are forms of emotional violence that Ana Maria continued to experience long after the initial insult of physical violence. We can’t distinguish whether her mental health symptoms were a pre-existing condition or a result of the traumatic experience presented here. It is likely, however, that all parts of this experience impacted her mental and physical health. As reported elsewhere, perceived social criticism and a lack of social support are barriers to the fulfillment of sexual and reproductive health among young Nicaraguan women. [ 18 ] These contextual risk factors undoubtedly played a role in Ana Maria’s ability to navigate the circumstances surrounding her assault and its aftermath.

What legal recourse was feasibly available to Ana Maria for the crime of her sexual assault? To our knowledge, Ana Maria did not report the rape to authorities nor did her godfather ever face criminal charges for his actions. Yet Ana Maria’s own fear of prosecution for undergoing the unsafe abortion, as well as shame and fear of being stigmatized by others in her community, strongly influenced her decision not to report the rape -- even though Law 779 contains sanctions specific to those who commit rape.

In the event she had reported the crime, however, it is unclear if Law 779 would have provided justice. There are no data to suggest that Law 779 has led to an increase in the reporting or prosecution of rape at the national level. To the contrary, qualitative work in Nicaragua found a perceived increase in VAW following the passage of the law. [ 14 ] In Nicaragua, the inconsistent or ineffective enforcement of Law 779 is another factor worthy of consideration in cases like Ana Maria’s where individuals do not report such crimes. Documents like the UN Women Model Protocol have recently been released to improve the enforcement of laws like Law 779 in Latin American countries, presenting an opportunity for the effective operationalization of the law in Nicaragua. [ 32 ] If Law 779 is not adequately enforced, women like Ana Maria face the potential for re-victimization through the structural violence of impuity and continued exposure to VAW. To our knowledge, Ana Maria’s perpetrator faced no consequences for his perpetration of harassment, coercion and rape of Ana Maria. Moreover, in countries where abortion is criminalized, such as El Salvador, it is most often women who face criminal sanctions. [ 33 ] Indeed, it was Ana Maria herself who bore the physical and mental burden that resulted from her assault, unintended pregnancy, and unsafe abortion.

The criminalization of abortion

The criminalization of health services is a strategy that governments use to regulate people’s sexuality and sexual activity. [ 34 ] The criminalization of services such as abortion limits women’s ability to make autonomous decisions about their SRH. By definition, laws that restrict access to health services exclude people from receiving the information and services necessary to realize the highest level of SRH possible. [ 5 ] The criminalization of abortion puts the health and well-being of individuals and communities at risk. Beyond the individual level, complications from unsafe abortion often put unnecessary and immeasurable financial burdens on health systems that are already stretched [ 28 ].

Ana Maria did not have a choice when it came to her abortion; the man who raped her coerced her to undergo an unsafe and illegal procedure. The criminalization of abortion in Nicaragua put Ana Maria’s health at risk in two ways: first, it prevented her from obtaining a safe abortion and second, it limited her access to comprehensive sexual health information that could have helped her address her unintended pregnancy, through emergency contraception. After the unsafe abortion procedure, her access to PAC was likely constrained by her own fear of the possible legal repercussions of undergoing an abortion, and was compounded by her inability to trust that a health care provider would maintain patient confidentiality and provide adequate PAC.

In Nicaragua, the total ban on abortion directly contradicts strategic objectives outlined in the Beijing Declaration, which guarantees women’s rights to comprehensive SRH care, including family planning and PAC services. Though providing PAC is not considered illegal under the total ban, many Nicaraguan health care providers refuse to treat women who have had unsafe abortions, which results in a ‘chilling effect’; providers do not want to be accused of being complicit in providing abortions so they refuse to provide PAC services. The ‘chilling effect’ put Ana Maria at risk of morbidity or mortality as a result of the complications that resulted from her unsafe abortion.

Equally troubling is the use of criminal law against individuals like Ana Maria as well as health care professionals that provide PAC. By requiring health care providers to report to the police women who have had abortions, the total ban violates the privacy inherent in the patient-provider relationship. Health care providers are faced with a dual loyalty to both the State’s laws and the confidentiality of their patients, which makes it difficult for providers to fulfill their professional obligations. It also makes health care professionals complicit in a discriminatory practice, one where women face legal sanctions in ways that men do not. The criminalization of abortion in Nicaragua therefore resulted in the fear, stigma, discrimination, and negative health outcomes observed in Ana Maria’s case.

The contextual risk factors that contributed to Ana Maria’s experience of rape, unintended pregnancy, and unsafe abortion are as follows: sexual assault, impunity for violence, gender inequality, restrictive social norms around SRH, stigma resulting from unintended pregnancy and abortion, harmful health impacts from an unsafe abortion, and fear of prosecution due to the total ban. Her first sexual experience was forced and nonconsensual and preceded by months of harassment. Social norms made taboo any discussion of the harassment and sexual violence she experienced at the hands of her godfather; without social support, she was coerced into undergoing an unsafe abortion that resulted in serious mental and physical health sequelae. The illegal nature of abortion in Nicaragua placed Ana Maria at risk for social stigma as well as criminal prosecution. Her subsequent underutilization of family planning services at the time of the interview also placed Ana Maria at risk for an unintended pregnancy in the future; other long-term physical and mental health effects of her experience remain unknown.

The realization of one’s sexual and reproductive rights guarantees autonomous decision-making over one’s fertility and sexual experiences. However, Ana Maria’s story demonstrates that an individual’s SRH decisions are not made in isolation, free from the influence of social norms and national laws. Far too many women experience their sexuality in the context of individual and structural violence, such as VAW and gender inequality. This case highlights the contextual risk factors that contributed to Ana Maria’s experience of violence, unintended pregnancy, and unsafe abortion; we must continue to critically investigate these factors to ensure that experiences like Ana Maria’s do not become further normalized in Nicaragua. Due to restrictive social norms around SRH, Ana Maria grew up experiencing stigma and taboo associated with sex, sexuality, contraceptive use and abortion. She also lacked access to information regarding SRH, healthy relationships, and how to respond to VAW before she was assaulted. After her assault, she did not have access to post-rape care, emergency contraception, safe abortion services, or mental health services to help her process this trauma. Shame and fear of stigma also prevented Ana Maria from reaching out for social support from family, friends, or the health or legal system. From the legal perspective, inadequate enforcement of VAW laws and the criminalization of abortion further exacerbated the trauma Ana Maria experienced.

It would require active engagement from the Nicaraguan government to address the contextual risk factors identified herein to protect their citizens’ right to health and prevent future experiences like Ana Maria’s. These efforts are particularly relevant given recent political unrest throughout Nicaragua including anti-government protests demanding the president’s resignation. [ 35 ] Nicaraguans’ right to health is at risk not only due to the widespread violence, but also because health care workers are being dismissed and persecuted nationwide. [ 36 ] Sexual and reproductive health researchers, advocates, and the public will continue to monitor Nicaragua’s response to the immediate demands and needs of its citizens -- including the demand that Nicaraguan women like Ana Maria are able to fully exercise their sexual and reproductive rights in times of both conflict and peace.

Availability of data and materials

Deidentified data are available upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Committee on Civil and Political Rights

Committee on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women

In-Depth Interviews

Postabortion Care

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Socioeconomic Status

Sexual and Reproductive Health

United Nations

Violence Against Women

World Health Organization

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Report of the international conference on population and development. Cairo; 1994. Available from: http://www.un.org/popin/icpd/conference/offeng/poa.html .