Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

5.1 Social Structure: The Building Blocks of Social Life

Learning objectives.

- Describe the difference between a status and a role.

- Understand the difference between an ascribed status, an achieved status, and a master status.

- List the major social institutions.

Social life is composed of many levels of building blocks, from the very micro to the very macro. These building blocks combine to form the social structure . As Chapter 1 “Sociology and the Sociological Perspective” explained, social structure refers to the social patterns through which a society is organized and can be horizontal or vertical. To recall, horizontal social structure refers to the social relationships and the social and physical characteristics of communities to which individuals belong, while vertical social structure , more commonly called social inequality , refers to ways in which a society or group ranks people in a hierarchy. This chapter’s discussion of social structure focuses primarily on horizontal social structure, while Chapter 8 “Social Stratification” through Chapter 12 “Aging and the Elderly” , as well as much material in other chapters, examine dimensions of social inequality. The (horizontal) social structure comprises several components, to which we now turn, starting with the most micro and ending with the most macro. Our discussion of social interaction in the second half of this chapter incorporates several of these components.

Status has many meanings in the dictionary and also within sociology, but for now we will define it as the position that someone occupies in society. This position is often a job title, but many other types of positions exist: student, parent, sibling, relative, friend, and so forth. It should be clear that status as used in this way conveys nothing about the prestige of the position, to use a common synonym for status. A physician’s job is a status with much prestige, but a shoeshiner’s job is a status with no prestige.

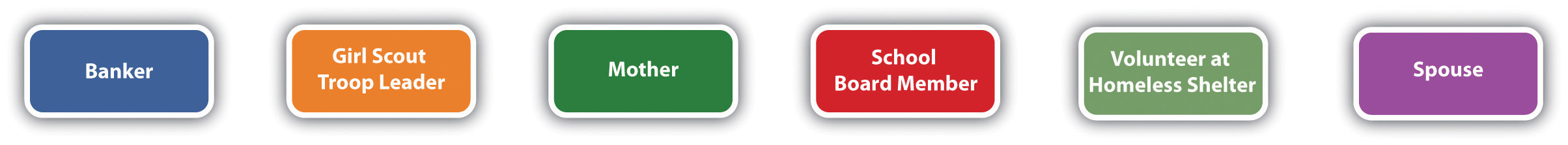

Any one individual often occupies several different statuses at the same time, and someone can simultaneously be a banker, Girl Scout troop leader, mother, school board member, volunteer at a homeless shelter, and spouse. This someone would be very busy! We call all the positions an individual occupies that person’s status set (see Figure 5.1 “Example of a Status Set” ).

Figure 5.1 Example of a Status Set

Sociologists usually speak of three types of statuses. The first type is ascribed status , which is the status that someone is born with and has no control over. There are relatively few ascribed statuses; the most common ones are our biological sex, race, parents’ social class and religious affiliation, and biological relationships (child, grandchild, sibling, and so forth).

Status refers to the position an individual occupies. Used in this way, a person’s status is not related to the prestige of that status. The jobs of physician and shoeshiner are both statuses, even though one of these jobs is much more prestigious than the other job.

Public Domain Images – CC0 public domain.

The second kind of status is called achieved status , which, as the name implies, is a status you achieve, at some point after birth, sometimes through your own efforts and sometimes because good or bad luck befalls you. The status of student is an achieved status, as is the status of restaurant server or romantic partner, to cite just two of the many achieved statuses that exist.

Two things about achieved statuses should be kept in mind. First, our ascribed statuses, and in particular our sex, race and ethnicity, and social class, often affect our ability to acquire and maintain many achieved statuses (such as college graduate). Second, achieved statuses can be viewed positively or negatively. Our society usually views achieved statuses such as physician, professor, or college student positively, but it certainly views achieved statuses such as burglar, prostitute, and pimp negatively.

The third type of status is called a master status . This is a status that is so important that it overrides other statuses you may hold. In terms of people’s reactions, master statuses can be either positive or negative for an individual depending on the particular master status they hold. Barack Obama now holds the positive master status of president of the United States: his status as president overrides all the other statuses he holds (husband, father, and so forth), and millions of Americans respect him, whether or not they voted for him or now favor his policies, because of this status. Many other positive master statuses exist in the political and entertainment worlds and in other spheres of life.

Some master statuses have negative consequences. To recall the medical student and nursing home news story that began this chapter, a physical disability often becomes such a master status. If you are bound to a wheelchair, for example, this fact becomes more important than the other statuses you have and may prompt people to perceive and interact with you negatively. In particular, they perceive you more in terms of your master status (someone bound to a wheelchair) than as the “person beneath” the master status, to cite Matt’s words. For similar reasons, gender, race, and sexual orientation may also be considered master statuses, as these statuses often subject women, people of color, and gays and lesbians, respectively, to discrimination and other problems, no matter what other statuses they may have.

Whatever status we occupy, certain objects signify any particular status. These objects are called status symbols . In popular terms, status symbol usually means something like a Rolls-Royce or BMW that shows off someone’s wealth or success, and many status symbols of this type exist. But sociologists use the term more generally than that. For example, the wheelchair that Matt the medical student rode for 12 days was a status symbol that signified his master status of someone with a (feigned) disability. If someone is pushing a stroller, the stroller is a status symbol that signifies that the person pushing it is a parent or caretaker of a young child.

Whatever its type, every status is accompanied by a role , which is the behavior expected of someone—and in fact everyone —with a certain status. You and most other people reading this book are students. Despite all the other differences among you, you have at least this one status in common. As such, there is a role expected of you as a student (at least by your professors); this role includes coming to class regularly, doing all the reading assigned from this textbook, and studying the best you can for exams. Roles for given statuses existed long before we were born, and they will continue long after we are no longer alive. A major dimension of socialization is learning the roles our society has and then behaving in the way a particular role demands.

Roles help us interact because we are familiar with the behavior associated with roles. Because shoppers and cashiers know what to expect of each other, their social interaction is possible.

David Tan – Cashier – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Because roles are the behavior expected of people in various statuses, they help us interact because we are familiar with the roles in the first place, a point to which the second half of this chapter returns. Suppose you are shopping in a department store. Your status is a shopper, and the role expected of you as a shopper—and of all shoppers—involves looking quietly at various items in the store, taking the ones you want to purchase to a checkout line, and paying for them. The person who takes your money is occupying another status in the store that we often call a cashier. The role expected of that cashier—and of all cashiers not only in that store but in every other store—is to accept your payment in a businesslike way and put your items in a bag. Because shoppers and cashiers all have these mutual expectations, their social interaction is possible.

Social Networks

Modern life seems increasingly characterized by social networks. A social network is the totality of relationships that link us to other people and groups and through them to still other people and groups. As Facebook and other social media show so clearly, social networks can be incredibly extensive. Social networks can be so large, of course, that an individual in a network may know little or nothing of another individual in the network (e.g., a friend of a friend of a friend of a friend). But these “friends of friends” can sometimes be an important source of practical advice and other kinds of help. They can “open doors” in the job market, they can introduce you to a potential romantic partner, they can pass through some tickets to the next big basketball game. As a key building block of social structure, social networks receive a fuller discussion in Chapter 6 “Groups and Organizations” .

Groups and Organizations

Groups and organizations are the next component of social structure. Because Chapter 6 “Groups and Organizations” discusses groups and organizations extensively, here we will simply define them and say one or two things about them.

A social group (hereafter just group ) consists of two or more people who regularly interact on the basis of mutual expectations and who share a common identity. To paraphrase John Donne, the 17th-century English poet, no one is an island; almost all people are members of many groups, including families, groups of friends, and groups of coworkers in a workplace. Sociology is sometimes called the study of group life, and it is difficult to imagine a modern society without many types of groups and a small, traditional society without at least some groups.

In terms of size, emotional bonding, and other characteristics, many types of groups exist, as Chapter 6 “Groups and Organizations” explains. But one of the most important types is the formal organization (also just organization ), which is a large group that follows explicit rules and procedures to achieve specific goals and tasks. For better and for worse, organizations are an essential feature of modern societies. Our banks, our hospitals, our schools, and so many other examples are all organizations, even if they differ from one another in many respects. In terms of their goals and other characteristics, several types of organizations exist, as Chapter 6 “Groups and Organizations” will again discuss.

Social Institutions

Yet another component of social structure is the social institution , or patterns of beliefs and behavior that help a society meet its basic needs. Modern society is filled with many social institutions that all help society meet its needs and achieve other goals and thus have a profound impact not only on the society as a whole but also on virtually every individual in a society. Examples of social institutions include the family, the economy, the polity (government), education, religion, and medicine. Chapter 13 “Work and the Economy” through Chapter 18 “Health and Medicine” examine each of these social institutions separately.

As those chapters will show, these social institutions all help the United States meet its basic needs, but they also have failings that prevent the United States from meeting all its needs. A particular problem is social inequality, to recall the vertical dimension of social structure, as our social institutions often fail many people because of their social class, race, ethnicity, gender, or all four. These chapters will also indicate that American society could better fulfill its needs if it followed certain practices and policies of other democracies that often help their societies “work” better than our own.

The largest component of social structure is, of course, society itself. Chapter 1 “Sociology and the Sociological Perspective” defined society as a group of people who live within a defined territory and who share a culture. Societies certainly differ in many ways; some are larger in population and some are smaller, some are modern and some are less modern. Since the origins of sociology during the 19th century, sociologists have tried to understand how and why modern, industrial society developed. Part of this understanding involves determining the differences between industrial societies and traditional ones.

One of the key differences between traditional and industrial societies is the emphasis placed on the community versus the emphasis placed on the individual. In traditional societies, community feeling and group commitment are usually the cornerstones of social life. In contrast, industrial society is more individualistic and impersonal. Whereas the people in traditional societies have close daily ties, those in industrial societies have many relationships in which one person barely knows the other person. Commitment to the group and community become less important in industrial societies, and individualism becomes more important.

Sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies (1887/1963) long ago characterized these key characteristics of traditional and industrial societies with the German words Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft . Gemeinschaft means human community, and Tönnies said that a sense of community characterizes traditional societies, where family, kin, and community ties are quite strong. As societies grew and industrialized and as people moved to cities, Tönnies said, social ties weakened and became more impersonal. Tönnies called this situation Gesellschaft and found it dismaying. Chapter 5 “Social Structure and Social Interaction” , Section 5.2 “The Development of Modern Society” discusses the development of societies in more detail.

Key Takeaways

- The major components of social structure are statuses, roles, social networks, groups and organizations, social institutions, and society.

- Specific types of statuses include the ascribed status, achieved status, and master status. Depending on the type of master status, an individual may be viewed positively or negatively because of a master status.

For Your Review

- Take a moment and list every status that you now occupy. Next to each status, indicate whether it is an ascribed status, achieved status, or master status.

- Take a moment and list every group to which you belong. Write a brief essay in which you comment on which of the groups are more meaningful to you and which are less meaningful to you.

Tönnies, F. (1963). Community and society . New York, NY: Harper and Row. (Original work published 1887).

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley Open Access Collection

The psychology of social class: How socioeconomic status impacts thought, feelings, and behaviour

Antony s. r. manstead.

1 Cardiff University, UK

Drawing on recent research on the psychology of social class, I argue that the material conditions in which people grow up and live have a lasting impact on their personal and social identities and that this influences both the way they think and feel about their social environment and key aspects of their social behaviour. Relative to middle‐class counterparts, lower/working‐class individuals are less likely to define themselves in terms of their socioeconomic status and are more likely to have interdependent self‐concepts; they are also more inclined to explain social events in situational terms, as a result of having a lower sense of personal control. Working‐class people score higher on measures of empathy and are more likely to help others in distress. The widely held view that working‐class individuals are more prejudiced towards immigrants and ethnic minorities is shown to be a function of economic threat, in that highly educated people also express prejudice towards these groups when the latter are described as highly educated and therefore pose an economic threat. The fact that middle‐class norms of independence prevail in universities and prestigious workplaces makes working‐class people less likely to apply for positions in such institutions, less likely to be selected and less likely to stay if selected. In other words, social class differences in identity, cognition, feelings, and behaviour make it less likely that working‐class individuals can benefit from educational and occupational opportunities to improve their material circumstances. This means that redistributive policies are needed to break the cycle of deprivation that limits opportunities and threatens social cohesion.

We are all middle class now. John Prescott, former Labour Deputy Prime Minister, 1997

Class is a Communist concept. It groups people as bundles and sets them against one another. Margaret Thatcher, former Conservative Prime Minister, 1992

One of the ironies of modern Western societies, with their emphasis on meritocratic values that promote the notion that people can achieve what they want if they have enough talent and are prepared to work hard, is that the divisions between social classes are becoming wider, not narrower. In the United Kingdom, for example, figures from the Equality Trust ( 2017 ) show that the top one‐fifth of households have 40% of national income, whereas the bottom one‐fifth have just 8%. These figures are based on 2012 data. Between 1938 and 1979, income inequality in the United Kingdom did reduce to some extent, but in subsequent decades, this process has reversed. Between 1979 and 2009/2010, the top 10% of the population increased its share of national income from 21% to 31%, whereas the share received by the bottom 10% fell from 4% to 1%. Wealth inequality is even starker than income inequality. Figures from the UK's Office for National Statistics (ONS, 2014 ) show that in the period 2012–2014, the wealthiest 10% of households in Great Britain owned 45% of household wealth, whereas the least wealthy 50% of households owned <9%. How can these very large divisions in material income and wealth be reconciled with the view that the class structure that used to prevail in the United Kingdom until at least the mid‐20th century is no longer relevant, because the traditional working class has ‘disappeared’, as asserted by John Prescott in one of the opening quotes, and reflected in the thesis of embourgeoisement analysed by Goldthorpe and Lockwood ( 1963 )? More pertinently for the present article, what implications do these changing patterns of wealth and income distribution have for class identity, social cognition, and social behaviour?

The first point to address concerns the supposed disappearance of the class system. As recent sociological research has conclusively shown, the class system in the United Kingdom is very much still in existence, albeit in a way that differs from the more traditional forms that were based primarily on occupation. In one of the more comprehensive recent studies, Savage et al . ( 2013 ) analysed the results of a large survey of social class in the United Kingdom, the BBC's 2011 Great British Class Survey, which involved 161,400 web respondents, along with the results of a nationally representative sample survey. Using latent class analysis, the authors identified seven classes, ranging from an ‘elite’, with an average annual household income of £89,000, to a ‘precariat’ with an average annual household income of £8,000. Among the many interesting results is the fact that the ‘traditional working‐class’ category formed only 14% of the population. This undoubtedly reflects the impact of de‐industrialization and is almost certainly the basis of the widely held view that the ‘old’ class system in the United Kingdom no longer applies. As Savage et al .'s research clearly shows, the old class system has been reconfigured as a result of economic and political developments, but it is patently true that the members of the different classes identified by these researchers inhabit worlds that rarely intersect, let alone overlap. The research by Savage et al . revealed that the differences between the social classes they identified extended beyond differences in financial circumstances. There were also marked differences in social and cultural capital, as indexed by size of social network and extent of engagement with different cultural activities, respectively. From a social psychological perspective, it seems likely that growing up and living under such different social and economic contexts would have a considerable impact on people's thoughts, feelings and behaviours. The central aim of this article was to examine the nature of this impact.

One interesting reflection of the complicated ways in which objective and subjective indicators of social class intersect can be found in an analysis of data from the British Social Attitudes survey (Evans & Mellon, 2016 ). Despite the fact that there has been a dramatic decline in traditional working‐class occupations, large numbers of UK citizens still describe themselves as being ‘working class’. Overall, around 60% of respondents define themselves as working class, and the proportion of people who do so has hardly changed during the past 33 years. One might reasonably ask whether and how much it matters that many people whose occupational status suggests that they are middle class describe themselves as working class. Evans and Mellon ( 2016 ) show quite persuasively that this self‐identification does matter. In all occupational classes other than managerial and professional, whether respondents identified themselves as working class or middle class made a substantial difference to their political attitudes, with those identifying as working class being less likely to be classed as right‐wing. No wonder Margaret Thatcher was keen to dispense with the concept of class, as evidenced by the quotation at the start of this paper. Moreover, self‐identification as working class was significantly associated with social attitudes in all occupational classes. For example, these respondents were more likely to have authoritarian attitudes and less likely to be in favour of immigration, a point I will return to later. It is clear from this research that subjective class identity is linked to quite marked differences in socio‐political attitudes.

A note on terminology

In what follows, I will refer to a set of concepts that are related but by no means interchangeable. As we have already seen, there is a distinction to be drawn between objective and subjective indicators of social class. In Marxist terms, class is defined objectively in terms of one's relationship to the means of production. You either have ownership of the means of production, in which case you belong to the bourgeoisie, or you sell your labour, in which case you belong to the proletariat, and there is a clear qualitative difference between the two classes. This worked well when most people could be classified either as owners or as workers. As we have seen, such an approach has become harder to sustain in an era when traditional occupations have been shrinking or have already disappeared, a sizeable middle‐class of managers and professionals has emerged, and class divisions are based on wealth and social and cultural capital.

An alternative approach is one that focuses on quantitative differences in socioeconomic status (SES), which is generally defined in terms of an individual's economic position and educational attainment, relative to others, as well as his or her occupation. As will be shown below, when people are asked about their identities, they think more readily in terms of SES than in terms of social class. This is probably because they have a reasonable sense of where they stand, relative to others, in terms of economic factors and educational attainment, and perhaps recognize that traditional boundaries between social classes have become less distinct. For these reasons, much of the social psychological literature on social class has focused on SES as indexed by income and educational attainment, and/or on subjective social class, rather than social class defined in terms of relationship to the means of production. For present purposes, the terms ‘working class’, which tends to be used more by European researchers, and ‘lower class’, which tends to be used by US researchers, are used interchangeably. Similarly, the terms ‘middle class’ and ‘upper class’ will be used interchangeably, despite the different connotations of the latter term in the United States and in Europe, where it tends to be reserved for members of the land‐owning aristocracy. A final point about terminology concerns ‘ideology’, which will here be used to refer to a set of beliefs, norms and values, examples being the meritocratic ideology that pervades most education systems and the (related) ideology of social mobility that is prominent in the United States.

Socioeconomic status and identity

Social psychological analyses of identity have traditionally not paid much attention to social class or SES as a component of identity. Instead, the focus has been on categories such as race, gender, sexual orientation, nationality and age. Easterbrook, Kuppens, and Manstead ( 2018 ) analysed data from two large, representative samples of British adults and showed that respondents placed high subjective importance on their identities that are indicative of SES. Indeed, they attached at least as much importance to their SES identities as they did to identities (such as ethnicity or gender) more commonly studied by self and identity researchers. Easterbrook and colleagues also showed that objective indicators of a person's SES were robust and powerful predictors of the importance they placed on different types of identities within their self‐concepts: Those with higher SES attached more importance to identities that are indicative of their SES position, but less importance on identities that are rooted in basic demographics or related to their sociocultural orientation (and vice versa).

To arrive at these conclusions, Easterbook and colleagues analysed data from two large British surveys: The Citizenship Survey (CS; Department for Communities and Local Government, 2012 ); and Understanding Society: The UK Household Longitudinal Study (USS; Buck & McFall, 2012 ). The CS is a (now discontinued) biannual survey of a regionally representative sample of around 10,000 adults in England and Wales, with an ethnic minority boost sample of around 5,000. The researchers analysed the most recent data, collected via interviews in 2010–2011. The USS is an annual longitudinal household panel survey that began in 2009. Easterbrook and colleagues analysed Wave 5 (2013–2014), the more recent of the two waves in which the majority of respondents answered questions relevant to class and other social identities.

Both the CS and the USS included a question about the extent to which respondents incorporated different identities into their sense of self. Respondents were asked how important these identities were ‘to your sense of who you are’. The CS included a broad range of identities, including profession, ethnic background, family, gender, age/life stage, income and education. The USS included a shorter list of identities, including profession, education, ethnic background, family, gender and age/life stage. When the responses to these questions were factor analysed, Easterbrook and colleagues found three factors that were common to the two datasets: SES‐based identities (e.g., income), basic‐demographic identities (e.g., age), and identities based on sociocultural orientation (e.g., ethnic background). In both datasets, the importance of each of these three identities was systematically related to objective indicators of the respondents’ SES: As the respondent's SES increased, the subjective importance of SES‐related identities increased, whereas the importance of basic‐demographic and (to a lesser extent) sociocultural identities decreased. Interestingly, these findings echo those of a qualitative, interview‐based study conducted with American college students: Aries and Seider ( 2007 ) found that affluent respondents were more likely than their less affluent counterparts to acknowledge the importance of social class in shaping their identities. As the researchers put it, ‘The affluent students were well aware of the educational benefits that had accrued from their economically privileged status and of the opportunities that they had to travel and pursue their interests. The lower‐income students were more likely to downplay class in their conception of their own identities than were the affluent students’ (p. 151).

Thus, despite SES receiving relatively scant attention from self and identity researchers, there is converging quantitative and qualitative evidence that SES plays an important role in structuring the self‐concept.

Contexts that shape self‐construal: Home, school, and work

Stephens, Markus, and Phillips ( 2014 ) have analysed the ways in which social class shapes the self‐concept through the ‘gateway contexts’ of home, school, and work. With a focus on the United States, but with broader implications, they argue that social class gives rise to culture‐specific selves and patterns of thinking, feeling, and acting. One type of self they label ‘hard interdependence.’ This, they argue, is characteristic of those who grow up in low‐income, working‐class environments. As the authors put it, ‘With higher levels of material constraints and fewer opportunities for influence, choice, and control, working‐class contexts tend to afford an understanding of the self and behavior as interdependent with others and the social context’ (p. 615). The ‘hard’ aspect of this self derives from the resilience that is needed to cope with adversity. The other type of self the authors identify is ‘expressive independence’, which is argued to be typical of those who grow up in affluent, middle‐class contexts. By comparison with working‐class people, those who grow up in middle‐class households ‘need to worry far less about making ends meet or overcoming persistent threats … Instead, middle‐class contexts enable people to act in ways that reflect and further reinforce the independent cultural ideal – expressing their personal preferences, influencing their social contexts, standing out from others, and developing and exploring their own interests’ (p. 615). Stephens and colleagues review a wide range of work on socialization that supports their argument that the contexts of home, school and workplace foster these different self‐conceptions. They also argue that middle‐class schools and workplaces use expressive independence as a standard for measuring success, and thereby create institutional barriers to upward social mobility.

The idea that schools are contexts in which social class inequalities are reinforced may initially seem puzzling, given that schools are supposed to be meritocratic environments in which achievement is shaped by ability and effort, rather than by any advantage conferred by class background. However, as Bourdieu and Passeron ( 1990 ) have argued, the school system reproduces social inequalities by promoting norms and values that are more familiar to children from middle‐class backgrounds. To the extent that this helps middle‐class children to outperform their working‐class peers, the ‘meritocratic’ belief that such performance differences are due to differences in ability and/or effort will serve to ‘explain’ and legitimate unequal performance. Consistent with this argument, Darnon, Wiederkehr, Dompnier, and Martinot ( 2018 ) primed the concept of merit in French fifth‐grade schoolchildren and found that this led to lower scores on language and mathematics tests – but that this only applied to low‐SES children. Moreover, the effect of the merit prime on test performance was mediated by the extent to which the children endorsed meritocratic beliefs. Here, then, is evidence that the ideology of meritocracy helps to reproduce social class differences in school settings.

Subjective social class

Stephens et al .’s ( 2014 ) conceptualization of culture‐specific selves that vary as a function of social class is compatible with the ‘subjective social rank’ argument advanced by Kraus, Piff, and Keltner ( 2011 ). The latter authors argue that the differences in material resources available to working‐ and middle‐class people create cultural identities that are based on subjective perceptions of social rank in relation to others. These perceptions are based on distinctive patterns of observable behaviour arising from differences in wealth, education, and occupation. ‘To the extent that these patterns of behavior are both observable and reliably associated with individual wealth, occupational prestige, and education, they become potential signals to others of a person's social class’ (Kraus et al ., 2011 , p. 246). Among the signals of social class is non‐verbal behaviour. Kraus and Keltner ( 2009 ) studied non‐verbal behaviour in pairs of people from different social class backgrounds and found that whereas upper‐class individuals were more disengaged non‐verbally, lower‐class individuals exhibited more socially engaged eye contact, head nods, and laughter. Furthermore, when naïve observers were shown 60‐s excerpts of these interactions, they used these disengaged versus engaged non‐verbal behavioural styles to make judgements of the educational and income backgrounds of the people they had seen with above‐chance accuracy. In other words, social class differences are reflected in social signals, and these signals can be used by individuals to assess their subjective social rank. By comparing their wealth, education, occupation, aesthetic tastes, and behaviour with those of others, individuals can determine where they stand in the social hierarchy, and this subjective social rank then shapes other aspects of their social behaviour. More recent research has confirmed these findings. Becker, Kraus, and Rheinschmidt‐Same ( 2017 ) found that people's social class could be judged with above‐chance accuracy from uploaded Facebook photographs, while Kraus, Park, and Tan ( 2017 ) found that when Americans were asked to judge a speaker's social class from just seven spoken words, the accuracy of their judgments was again above chance.

The fact that there are behavioural signals of social class also opens up the potential for others to hold prejudiced attitudes and to engage in discriminatory behaviour towards those from a lower social class, although Kraus et al . ( 2011 ) focus is on how the social comparison process affects the self‐perception of social rank, and how this in turn affects other aspects of social behaviour. These authors argue that subjective social rank ‘exerts broad influences on thought, emotion, and social behavior independently of the substance of objective social class’ (p. 248). The relation between objective and subjective social class is an interesting issue in its own right. Objective social class is generally operationalized in terms of wealth and income, educational attainment, and occupation. These are the three ‘gateway contexts’ identified by Stephens et al . ( 2014 ). As argued by them, these contexts have a powerful influence on individual cognition and behaviour who operate within them, but they do not fully determine how individuals developing and living in these contexts think, feel, and act. Likewise, there will be circumstances in which individuals who objectively are, say, middle‐class construe themselves as having low subjective social rank as a result of the context in which they live.

There is evidence from health psychology that measures of objective and subjective social class have independent effects on health outcomes, with subjective social class explaining variation in health outcomes over and above what can be accounted for in terms of objective social class (Adler, Epel, Castellazzo, & Ickovics, 2000 ; Cohen et al ., 2008 ). For example, in the prospective study by Cohen et al . ( 2008 ), 193 volunteers were exposed to a cold or influenza virus and monitored in quarantine for objective and subjective signs of illness. Higher subjective class was associated with less risk of becoming ill as a result of virus exposure, and this relation was independent of objective social class. Additional analyses suggested that the impact of subjective social class on likelihood of becoming ill was due in part to differences in sleep quantity and quality. The most plausible explanation for such findings is that low subjective social class is associated with greater stress. It may be that seeing oneself as being low in subjective class is itself a source of stress, or that it increases vulnerability to the effects of stress.

Below I organize the social psychological literature on social class in terms of the impact of class on three types of outcome: thought , encompassing social cognition and attitudes; emotion , with a focus on moral emotions and prosocial behaviour; and behaviour in high‐prestige educational and workplace settings. I will show that these impacts of social class are consistent with the view that the different construals of the self that are fostered by growing up in low versus high social class contexts have lasting psychological consequences.

Social cognition and attitudes

The ways in which these differences in self‐construal shape social cognition have been synthesized into a theoretical model by Kraus, Piff, Mendoza‐Denton, Rheinschmidt, and Keltner ( 2012 ). This model is shown in Figure 1 . They characterize the way lower‐class individuals think about the social environment as ‘contextualism’, meaning a psychological orientation that is motivated by the need to deal with external constraints and threats; and the way that upper‐class people think about the social environment as ‘solipsism’, meaning an orientation that is motivated by internal states such as emotion and by personal goals. One way in which these different orientations manifest themselves is in differences in responses to threat. The premise here is that lower‐class contexts are objectively characterized by greater levels of threat, as reflected in less security in employment, housing, personal safety, and health. These chronic threats foster the development of a ‘threat detection system’, with the result that people who grow up in such environments have a heightened vigilance to threat.

Model of the way in which middle‐ and working‐class contexts shape social cognition, as proposed by Kraus et al . ( 2012 ). From Kraus et al . ( 2012 ), published by the American Psychological Association. Reprinted with permission.

Another important difference between the contextualist lower‐class orientation and the solipsistic upper‐class one, according to Kraus et al . ( 2012 ), is in perceived control. Perceived control is closely related to other key psychological constructs, such as attributions. The evidence shows very clearly that those with lower subjective social class are also lower in their sense of personal control, and it also suggests that this reduced sense of control is related to a preference for situational (rather than dispositional) attributions for a range of social phenomena, including social inequality. The logic connecting social class to perceptions of control is straightforward: Those who grow up in middle‐ or upper‐class environments are likely to have more material and psychological resources available to them, and as a result have stronger beliefs about the extent to which they can shape their own social outcomes; by contrast, those who grow up in lower‐class environments are likely to have fewer resources available to them, and as a result have weaker beliefs about their ability to control their outcomes. There is good empirical support for these linkages. In a series of four studies, Kraus, Piff, and Keltner ( 2009 ) found that, by comparison with their higher subjective social class counterparts, lower subjective social class individuals (1) reported lower perceived control and (2) were more likely to explain various phenomena, ranging from income inequality to broader social outcomes like getting into medical school, contracting HIV, or being obese, as caused by external factors, ones that are beyond the control of the individual. Moreover, consistent with the authors’ reasoning, there was a significant indirect effect of subjective social class on the tendency to see phenomena as caused by external factors, via perceived control.

Another important social cognition measure in relation to social class is prejudice. There are two aspects of prejudice in this context. One is prejudice against people of a different class than one's own and especially attitudes towards those who are poor or unemployed; the other is the degree to which people's prejudiced attitudes about other social groups are associated with their own social class. Regarding attitudes to people who belong to a different social class, the UK evidence clearly shows that attitudes to poverty have changed over the last three decades, in that there is a rising trend for people to believe that those who live in need do so because of a lack of willpower, or because of laziness, accompanied by a corresponding decline in the belief that people live in need because of societal injustice (Clery, Lee, & Kunz, 2013 ). Interestingly, in their analysis of British Social Attitudes data over a period of 28 years, Clery et al . conclude that ‘there are no clear patterns of change in the views of different social classes, suggesting changing economic circumstances exert an impact on attitudes to poverty across society, not just among those most likely to be affected by them’ (p. 18). Given the changing attitudes to poverty, it is unsurprising to find that public attitudes to welfare spending and to redistributive taxation have also changed in a way that reflects less sympathy for those living in poverty. For example, attitudes to benefits for the unemployed have changed sharply in the United Kingdom since 1997, when a majority of respondents still believed that benefits were too low. By 2008, an overwhelming majority of respondents believed that these benefits were too high (Taylor‐Gooby, 2013 ). The way in which economic austerity has affected attitudes to these issues was the subject of qualitative research conducted by Valentine ( 2014 ). Interviews with 90 people in northern England, drawn from a range of social and ethnic backgrounds, showed that many respondents believed that unemployment is due to personal, rather than structural, failings, and that it is a ‘lifestyle choice’, leading interviewees to blame the unemployed for their lack of work and to have negative attitudes to welfare provision. Valentine ( 2014 , p. 2) observed that ‘a moralised sense of poverty as the result of individual choice, rather than structural disadvantage and inequality, was in evidence across the majority of respondents’, and that ‘Negative attitudes to welfare provision were identified across a variety of social positions and were not exclusively reserved to individuals from either working class or middle class backgrounds’.

Turning to the attitudes to broader social issues held by members of different social classes, there is a long tradition in social science of arguing that working‐class people are more prejudiced on a number of issues, especially with respect to ethnic minorities and immigrants (e.g., Lipset, 1959 ). Indeed, there is no shortage of evidence showing that working‐class white people do express more negative attitudes towards these groups. One explanation for this association is that working‐class people tend to be more authoritarian – a view that can be traced back to the early research on the authoritarian personality (Adorno, Frenkel‐Brunswik, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950 ). Recent research providing evidence in favour of this view is reported by Carvacho et al . ( 2013 ). Using a combination of cross‐sectional surveys and longitudinal studies conducted in Europe and Chile, these authors focused on the role of ideological attitudes, in the shape of right‐wing authoritarianism (RWA; Altemeyer, 1998 ) and social dominance orientation (SDO; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999 ), as mediators of the relation between social class and prejudice. To test their predictions, the researchers analysed four public opinion datasets: one based on eight representative samples in Germany; a second based on representative samples from four European countries (France, Germany, Great Britain, and the Netherlands); a third based on longitudinal research in Germany; and a fourth based on longitudinal research in Chile. Consistent with previous research, the researchers found that income and education, the two indices of social class that they used, predicted higher scores on a range of measures of prejudice, such that lower income and education were associated with greater prejudice – although education proved to be a more consistently significant predictor of prejudice than income did. RWA and SDO were negatively associated with income and education, such that higher scores on income and education predicted lower scores on RWA and SDO. Finally, there was also evidence consistent with the mediation hypothesis: The associations between income and education, on the one hand, and measures of prejudice, on the other, were often (but not always) mediated by SDO and (more consistently) RWA. Carvacho and colleagues concluded that ‘the working class seems to develop and reproduce an ideological configuration that is generally well suited for legitimating the social system’ (p. 283).

Indeed, a theme that emerges from research on social class and attitudes is that ideological factors have a powerful influence on attitudes. The neoliberal ideology that has dominated political discourse in most Western, industrialized societies in the past three decades has influenced attitudes to such an extent that even supporters of left‐of‐centre political parties, such as the Labour Party in the United Kingdom, regard poverty as arising from individual factors and tend to hold negative beliefs about the level of welfare benefits for the unemployed. Such attitudes are shared to a perhaps surprising extent by working‐class people (Clery et al ., 2013 ) and, as we have seen, the research by Carvacho et al . ( 2013 ) suggests that working‐class people endorse ideologies that endorse and preserve a social system that materially disadvantages them.

The notion that people who are disadvantaged by a social system are especially likely to support it is known as the ‘system justification hypothesis’, which holds that ‘people who suffer the most from a given state of affairs are paradoxically the least likely to question, challenge, reject, or change it’ (Jost, Pelham, Sheldon, & Sullivan, 2003 , p. 13). The rationale for this prediction derives in part from cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957 ), the idea being that it is psychologically inconsistent to experience oppression but not to protest against the system that causes it. One way to reduce the resulting dissonance is to support the system even more strongly, in the same way that those who have to go through an unpleasant initiation rite in order to join a group or organization become more strongly committed to it.

Two large‐scale studies of survey data (Brandt, 2013 ; Caricati, 2017 ) have cast considerable doubt on the validity of this hypothesis, showing that any tendency for people who are at the bottom of a social system to be more likely to support the system than are their advantaged counterparts is, at best, far from robust. Moreover, it has been argued that there is in any case a basic theoretical inconsistency between system justification theory and cognitive dissonance theory (Owuamalam, Rubin, & Spears, 2016 ). However, the fact that working‐class people may not be more supportive of the capitalist system than their middle‐ and upper‐class counterparts does not mean that they do not support the system. Thus, the importance of Carvacho et al .'s ( 2013 ) findings is not necessarily undermined by the results reported by Brandt ( 2013 ) and Caricati ( 2017 ). Being willing to legitimate the system is not the same thing as having a stronger tendency to do this than people who derive greater advantages from the system.

The finding that there is an association between social class and prejudice has also been explained in terms of economic threat. The idea here is that members of ethnic minorities and immigrants also tend to be low in social status and are therefore more likely to be competing with working‐class people than with middle‐class people for jobs, housing, and other services. A strong way to test the economic threat explanation would be to assess whether higher‐class people are prejudiced when confronted with immigrants who are highly educated and likely to be competing with them for access to employment and housing. Such a test was conducted by Kuppens, Spears, Manstead, and Tausch ( 2018 ). These researchers examined whether more highly educated participants would express negative attitudes towards highly educated immigrants, especially when threat to the respondents’ own jobs was made salient, either by drawing attention to the negative economic outlook or by subtly implying that the respondents’ own qualifications might be insufficient in the current job market. Consistent with the economic threat hypothesis, a series of experimental studies with student participants in different European countries showed that attitudes to immigrants were most negative when the immigrants also had a university education.

The same researchers also combined US census data with American National Election Study survey data to examine whether symbolic racism was higher in areas where there was a higher number of Blacks with a similar education to that of the White participants. In areas where Blacks were on average less educated, a higher number Blacks was associated with more symbolic racism among Whites who had less education, but in areas where Blacks were on average highly educated, a higher number of Blacks was associated with more symbolic racism on the part of highly educated White people. Again, these findings are consistent with the view that prejudice arises from economic threat.

Research reported by Jetten, Mols, Healy, and Spears ( 2017 ) is also relevant to this issue. These authors examined how economic instability affects low‐SES and high‐SES people. Unsurprisingly, they found that collective angst was higher among low‐SES participants. However, they also found that high‐SES participants expressed anxiety when they were presented with information suggesting that there was high economic instability, that is, that the ‘economic bubble’ might be about to burst. Moreover, they were more likely to oppose immigration when economic instability was said to be high, rather than low. These results reflect the fact that high‐SES people have a lot to lose in times of economic crisis, and that this ‘fear of falling’ is associated with opposition to immigration.

Together, these results provide good support for an explanation of the association between social class and prejudice in terms of differential threat to the group (see also Brandt & Henry, 2012 ; Brandt & Van Tongeren, 2017 ). Ethnic minorities and immigrants typically pose most threat to the economic well‐being of working‐class people who have low educational qualifications, and this provides the basis for the observation that working‐class people are more likely to be prejudiced. The fact that higher‐educated and high‐SES people express negative views towards ethnic minorities and immigrants when their economic well‐being is threatened shows that it is perceived threat to one's group's interests that underpins this prejudice. It is also worth noting that the perception of threat to a group's economic interests is likely to be greater during times of economic recession.

Emotion and prosocial behaviour

A strong theme emerging from research investigating the relation between social class and emotion is that lower‐class individuals score more highly on measures of empathy. The rationale for expecting such a link is that because lower‐class individuals are more inclined to explain events in terms of external factors, they should be more sensitive to the ways in which external events shape the emotions of others, and therefore better at judging other people's emotions. A complementary rationale is that the tendency for lower social class individuals to be more socially engaged and to have more interdependent social relationships should result in greater awareness of the emotions experienced by others. This reasoning was tested in three studies reported by Kraus, Côté, and Keltner ( 2010 ).

In the first of these studies, the authors examined the relation between educational attainment (a proxy for social class) and scores on the emotion recognition subscale of the Mayer‐Salovey‐Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2002 ). High‐school‐educated participants attained a higher score than did their college‐educated counterparts. In a second study, pairs of participants took part in a hypothetical job interview in which an experimenter asked each of them a set of standard questions. This interaction provided the basis for the measure of empathic accuracy, in that each participant was asked to rate both their own emotions and their partner's emotions during the interview. Subjective social class was again related to empathic accuracy, with lower‐class participants achieving a higher score. Moreover, lower‐class participants were more inclined to explain decisions they made in terms of situational rather than dispositional factors, and the relation between subjective social class and empathy was found to be mediated by this tendency to explain decisions in terms of situational factors. The researchers conducted a third study in which they manipulated subjective social class. This time they assessed empathic accuracy using the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (Baron‐Cohen, Wheelwright, Hill, Raste, & Plumb, 2001 ). Participants who were temporarily induced to experience lower social class were better at recognizing emotions from the subtle cues available from the eye region of the face.

These findings are compatible with the view that lower social class individuals are more sensitive to contextual variation and more inclined to explain events in situational terms. However, some aspects of the results are quite surprising. For example, there seems to be no compelling reason to predict that greater sensitivity to contextual variation would be helpful in judging static facial expressions, which were the stimuli in Studies 1 and 3 of Kraus et al .'s ( 2010 ) research. Thus, the relation between social class and emotion recognition in these studies would seem to depend on the notion that the greater interdependence that is characteristic of lower‐class social environments fosters greater experience with, and therefore knowledge of, the relation between facial movement and subjective emotion, although it still seems surprising that a temporary induction of lower subjective social class, as used in Study 3, should elicit the same effect as extensive real‐life experience of inhabiting lower‐class environments.

If lower‐class individuals are more empathic than their higher‐class counterparts, and are therefore better at recognizing the distress or need of others, this is likely to influence their behaviour in settings where people are distressed and/or in need. This, indeed, is what the evidence suggests. In a series of four studies, Piff, Kraus, Côté, Cheng, and Keltner ( 2010 ) found a consistent tendency for higher‐class individuals to be less inclined to help others than were their lower‐class counterparts. In Study 1, participants low in subjective social class made larger allocations in a dictator game (a game where you are free to allocate as much or as little of a resource to another person as you want) played with an anonymous other than did participants high in subjective social class. In Study 2, subjective social class was manipulated by asking participants to compare themselves to people either at the very top or very bottom of the status hierarchy ladder, the idea being that subjective social class should be lower for those making upward comparisons and higher for those making downward comparisons. Prosocial behaviour was measured by asking participants to indicate the percentage of income that people should spend on a variety of goods and services, one of which was charitable donations. Participants who were induced to experience lower subjective social class indicated that a greater percentage of people's annual salary should be spent on charitable donations compared to participants who were induced to experience higher subjective social class. In Study 3, the researchers used a combination of educational attainment and household income to assess social class and used social value orientation (Van Lange, De Bruin, Otten, & Joireman, 1997 ) as a measure of egalitarian values. These two variables were used to predict behaviour in a trust game. Consistent with predictions, lower‐class participants showed greater trust in their anonymous partner than did their higher‐class counterparts, and this relation was mediated by egalitarian values. In their final study, the researchers manipulated compassion by asking participants in the compassion condition to view a 46‐s video about child poverty. Higher‐ and lower‐class participants were then given the chance to help someone in need. The researchers predicted that helping would only be moderated by compassion among higher‐class participants, on the grounds that lower‐class participants would already be disposed to help, and the results were consistent with this prediction. Overall, these four studies are consistent in showing that, relative to higher‐class people, lower‐class people are more generous, support charity to a greater extent, are more trusting towards a stranger, and more likely to help a person in distress.

The reliability of this finding has been called into question by Korndörfer, Egloff, and Schmukle ( 2015 ), who found contrary evidence in a series of studies. One way to resolve these apparently discrepant findings is to argue, as Kraus and Callaghan ( 2016 ) did, that the relation between social class and prosocial behaviour is moderated by a number of factors, including whether the context is a public or private one. To test this idea, Kraus and Callaghan ( 2016 ) conducted a series of studies in which they manipulated whether donations made to an anonymous other in a dictator game were made in a private or public context. In the private context, the donor remained anonymous. In the public context, the donor's name and city of residence were announced, along with the donation. Lower‐class participants were more generous in private than in public, whereas the reverse was true for higher‐class participants. Interestingly, higher‐class participants were more likely to expect to feel proud about acting prosocially, and this difference in anticipated pride mediated the effect of social class on the difference between public and private donations.

The fact that lower‐class people have been found to hold more egalitarian values and to be more likely to help regardless of compassion level suggests that it is the greater resources of higher‐class participants that makes them more selfish and therefore less likely to help others. This ‘selfishness’ account of the social class effect on prosocial behaviour is supported by another series of studies reported by Piff, Stancato, Côté, Mendoza‐Denton, and Keltner ( 2012 ), who found that, relative to lower‐class individuals, higher‐class people were more likely to show unethical decision‐making tendencies, to take valued goods from others, to lie in a negotiation, to cheat to increase their chances of winning a prize and to endorse unethical behaviour at work. There was also evidence that these unethical tendencies were partly accounted for by more favourable attitudes towards greed among higher‐class people. Later research shows that the relation between social class and unethical behaviour is moderated by whether the behaviour benefits the self or others. Dubois, Rucker, and Galinsky ( 2015 ) varied who benefited from unethical behaviour and showed that the previously reported tendency for higher‐class people to make more unethical decisions was only observed when the outcome was beneficial to the self. These findings are consistent with the view that the greater resources enjoyed by higher‐class individuals result in a stronger focus on the self and a reduced concern for the welfare of others.

Interestingly, this stronger self‐focus and lesser concern for others’ welfare on the part of higher‐class people are more evident in contexts characterized by high economic inequality. This was shown by Côté, House, and Willer ( 2015 ), who analysed results from a nationally representative US survey and showed that higher‐income respondents were only less generous in the offers they made to an anonymous other in a dictator game than their lower‐income counterparts in areas that were high in economic inequality, as reflected in the Gini coefficient. Indeed, in low inequality areas, there was evidence that higher‐income respondents were more generous than their lower‐income counterparts. To test the causality of this differential association between income and generosity in high and low inequality areas, the authors conducted an experiment in which participants were led to believe that their home state was characterized by high or low degree of economic inequality and then played a dictator game with an anonymous other. High‐income participants were less generous than their low‐income counterparts in the high inequality condition but not in the low inequality condition.

A possible issue with Côté et al . ( 2015 ) research in the current context is that it focuses on income rather than class. Although these variables are clearly connected, class is generally thought to be indexed by more than income. The research nevertheless suggests that economic inequality plays a key role in shaping the attitudes and behaviours of higher‐class individuals. There are at least three (not mutually exclusive) explanations for this influence of inequality. One is that inequality increases the sense of entitlement in higher‐class people, because they engage more often in downward social comparisons. Another is that higher‐class people may be more concerned about losing their privileged position in society if they perceive a large gap between the rich and the poor. A final explanation is that higher‐class people may be more highly motivated to justify their privileged position in society when the gap between rich and poor is a large one. Whichever of these explanations is correct – and they may all be to some extent – the fact that prosocial behaviour on the part of higher‐class individuals decreases under conditions of high economic inequality is important, given that the United States is one of the most economically unequal societies in the industrialized world. In unequal societies, then, it seems safe to conclude that on average, higher‐class individuals are less likely than their lower‐class counterparts to behave prosocially, especially where the prosocial behaviour is not public in nature.

Universities and workplaces

The selective nature of higher education (HE), involving economic and/or qualification requirements to gain entry, makes a university a high‐status context. Working‐class people seeking to attain university‐level qualifications are therefore faced with working in an environment in which they may feel out of place. Highly selective universities such as Oxford and Cambridge in the United Kingdom, or Harvard, Stanford, and Yale in the United States, are especially likely to appear to be high in status and therefore out of reach. Indeed, the proportion of working‐class students at Oxford and Cambridge is strikingly low. According to the UK's Higher Education Statistics Agency , the percentage of students at Oxford and Cambridge who were from routine/manual occupational backgrounds was 11.5 and 12.6, respectively, in the academic year 2008/9. This compares with an ONS figure of 37% of all people aged between 16 and 63 in the United Kingdom being classified with such backgrounds. The figures for Oxford and Cambridge are extreme, but they illustrate a more general phenomenon, both in the United Kingdom and internationally: students at elite, research‐led universities are more likely to come from middle‐ and upper‐class backgrounds than from working‐class backgrounds (Jerrim, 2013 ).

The reasons for the very low representation of working‐class students at these elite institutions are complex (Chowdry, Crawford, Dearden, Goodman, & Vignoles, 2013 ), but at least one factor is that many working‐class students do not consider applying because they do not see themselves as feeling at home there. They see a mismatch between the identity conferred by their social backgrounds and the identity they associate with being a student at an elite university. This is evident from ethnographic research. For example, Reay, Crozier, and Clayton ( 2010 ) interviewed students from working‐class backgrounds who were attending one of four HE institutions, including an elite university (named Southern in the report). A student at Southern said this about her mother's reaction to her attending this elite university: ‘I don't think my mother really approves of me going to Southern. It's not what her daughter should be doing so I don't really mention it when I go home. It's kind of uncomfortable to talk about it’ (p. 116). In a separate paper, Reay, Crozier, and Clayton ( 2009 ) focus on the nine students attending Southern, examining whether these students felt like ‘fish out of water’. Indeed, there was evidence of difficulty in adjusting to the new environment, both socially and academically. One student said, ‘I wasn't keen on Southern as a place and all my preconceptions were “Oh, it's full of posh boarding school types”. And it was all true … it was a bit of a culture shock’ (p. 1111), while another said, ‘If you were the best at your secondary school … you're certainly not going to be the best here’ (p. 1112). A similar picture emerges from research in Canada by Lehmann ( 2009 , 2013 ), who interviewed working‐class students attending a research‐intensive university, and found that the students experienced uncomfortable conflicts between their new identities as university students and the ties they had with family members and non‐student friends.

Such is the reputation of elite, research‐intensive universities that working‐class high‐school students are unlikely to imagine themselves attending such institutions, even if they are academically able. Perceptions of these universities as elitist are likely to deter such students from applying. Evidence of this deterrence comes from research conducted by Nieuwenhuis, Easterbrook, and Manstead ( 2018 ). They report two studies in which 16‐ to 18‐year‐old secondary school students in the United Kingdom were asked about the universities they intended to apply to. The studies were designed to test the theoretical model shown in Figure 2 , which was influenced by prior work on the role of identity compatibility conducted by Jetten, Iyer, Tsivrikos, and Young ( 2008 ). According to the model in Figure 2 , SES influences university choice partly through its impact on perceived identity compatibility and anticipated acceptance at low‐ and high‐status universities.

Theoretical model of the way in which the socioeconomic status ( SES ) influences application to high‐status universities as a result of social identity factors and academic achievement, as proposed by Nieuwenhuis et al . ( 2018 ).

In the first study conducted by Nieuwenhuis and colleagues, students who were 6 months away from making their university applications responded to questions about their perceptions of two universities, one a research‐intensive, selective university (SU), the other a less selective university (LSU). Both universities were located in the same geographical region, not far from the schools where the participants were recruited. In the second study, students who were 6 weeks away from making their university applications responded to similar questions, but this time about three universities in the region, two of which were the same as those in Study 1, while the third was a highly selective institution (HSU). The questions put to respondents measured their perceptions of identity compatibility (e.g., consistency between family background and decision to go to university) and anticipated acceptance (e.g., anticipated identification with students at the university in question). Measures of parental education and academic achievement in previous examinations were taken, as well as the three universities to which they would most like to apply, which were scored in accordance with a published national league table.

In both studies, it was found that relatively disadvantaged students (whose parents had low levels of educational attainment) scored lower on identity compatibility and that low scores on identity compatibility were associated with lower anticipated acceptance at the SU (Study 1) or at the HSU (Study 2). These anticipated acceptance scores, in turn, predicted the type of university to which participants wanted to apply, with those who anticipated feeling accepted at more selective universities being more likely to apply to higher status universities. All of these relations were significant while controlling for academic achievement. Together, the results of these studies show that perceptions of acceptance at different types of university are associated with HE choices independently of students’ academic ability. This helps to explain why highly able students from socially disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to settle for less prestigious universities.

Alternatively, working‐class students may opt out of HE altogether. Hutchings and Archer ( 2001 ) interviewed young working‐class people who were not participating in HE and found that a key reason for their non‐participation was a perception that the kinds of HE institutions that were realistically available to them were second‐rate: ‘[O]ur respondents constructed two very different pictures of HE. One was of Oxbridge and campus universities, pleasant environments in which middle‐class students … can look forward to achieving prestigious degrees and careers. The second construction was of rather unattractive buildings in which “skint” working‐class students … have to work hard under considerable pressure, combining study with a job and having little time for social life. This second picture was the sort of HE that our respondents generally talked about as available to them, and they saw it as inferior to ‘real’ HE’ (p. 87).

Despite the deterrent effect of perceived identity incompatibility and lack of psychological fit, some working‐class students do gain entry to high‐status universities. Once there, they are confronted with the same issues of fit. Stephens, Fryberg, Markus, Johnson, and Covarrubias ( 2012 ) describe this as ‘cultural mismatch’, arguing that the interdependent norms that characterize the working‐class backgrounds of most first‐generation college students in the United States do not match the middle‐class independent norms that prevail in universities offering 4‐year degrees and that this mismatch leads to greater discomfort and poorer academic performance. Their cultural mismatch model is summarized in Figure 3 .

Model of cultural mismatch proposed by Stephens, Fryberg, Markus, et al . ( 2012 ). The mismatch is between first‐generation college students’ norms, which are more interdependent than those of continuing‐generation students, and the norms of independence that prevail in universities. From Stephens, Fryberg, Markus, et al . ( 2012 ), published by the American Psychological Association. Reprinted with permission.

To test this model, Stephens, Fryberg, Markus, et al . ( 2012 ) surveyed university administrators at the top 50 national universities and the top 25 liberal arts colleges. The majority of the 261 respondents were deans. They were asked to respond to items expressing interdependent (e.g., learn to work together with others) or independent (e.g., learn to express oneself) norms, selecting those that characterized their institution's culture or choosing statements reflecting what was more often emphasized by the institution. More than 70% of the respondents chose items reflecting a greater emphasis on independence than on interdependence. Similar results were found in a follow‐up study involving 50 administrators at second‐tier universities and liberal arts colleges, showing that this stronger focus on independence was not only true of elite institutions. Moreover, a longitudinal study of first‐generation students found that this focus on independence did not match the students’ interdependent motives for going to college, in that first‐generation students selected fewer independent motives (e.g., become an independent thinker) and twice as many interdependent motives (e.g., give back to the community), compared to their continuing‐generation counterparts, and that this greater focus on interdependent motives was associated with lower grades in the first 2 years of study, even after controlling for race and SAT scores.

As Stephens and her colleagues have shown elsewhere (e.g., Stephens, Brannon, Markus, & Nelson, 2015 ), there are steps that can be taken to reduce working‐class students’ perception that they do not fit with their university environment. These authors argue that ‘a key goal of interventions should be to fortify and to elaborate school‐relevant selves – the understanding that getting a college degree is central to “who I am”, “who I hope to become”, and “the future I envision for myself”’ (p. 3). Among the interventions that they advocate as ways of creating a more inclusive culture at university are: providing working‐class role models; diversifying the way in which university experience is represented, so that university culture also provides ways of achieving interdependent goals that may be more compatible with working‐class students’ values; and ensuring that working‐class students have a voice, for example, by providing forums in which they can express shared interests and concerns.

Although there is a less well‐developed line of work on the ways in which high‐status places of work affect the aspirations and behaviours of working‐class employees, there is good reason to assume that the effects and processes identified in research on universities as places to study generalize to prestigious employment organizations as places to work (Côté, 2011 ). To the extent that many workplaces are dominated by middle‐class values and practices, working‐class employees are likely to feel out of place (Ridgway & Fisk, 2012 ). This applies both to gaining entry to the workplace, by negotiating the application and selection process (Rivera, 2012 ), and (if successful) to the daily interactions between employees in the workplace. In the view of Stephens, Fryberg, and Markus ( 2012 ), many workplaces are characterized by cultures of expressive independence, where working‐class employees are less likely to feel at home. As Stephens et al . ( 2014 , p. 626) argue, ‘This mismatch between working‐class employees and their middle‐class colleagues and institutions could also reduce employees’ job security and satisfaction, continuing the cycle of disadvantage for working‐class employees.’

Towards an integrative model

The work reviewed here provides the basis for an integrative model of how social class affects thoughts, feelings, and behaviour. The model is shown in Figure 4 and builds on the work of others, especially that of Nicole Stephens and colleagues and that of Michael Kraus and colleagues. At the base of the model are differences in the material circumstances of working‐class and middle‐class people. These differences in income and wealth are associated with differences in social capital, in the form of friendship networks, and cultural capital, in the form of tacit knowledge about how systems work, that have a profound effect on the ways in which individuals who grow up in these different contexts construe themselves and their social environments. For example, if you have family members or friends who have university degrees and/or professional qualifications, you are more likely to entertain these as possible futures than if you do not have these networks; and if through these networks you have been exposed to libraries, museums, interviews, and so on, you are more likely to know how these cultural institutions work, less likely to be intimidated by them, and more likely to make use of them. In sum, a middle‐class upbringing is more likely to promote the perception that the environment is one full of challenges that can be met rather than threats that need to be avoided. These differences in self‐construal and models of interpersonal relations translate into differences in social emotions and behaviours that are noticeable to self and others, creating the opportunity for people to rank themselves and others, and for differences in norms and values to emerge. To the extent that high‐status institutions in society, such as elite universities and prestigious employers, are characterized by norms and values that are different from those that are familiar to working‐class people, the latter will feel uncomfortable in such institutions and will perform below their true potential.

Integrative model of how differences in material conditions generate social class differences and differences in social cognition, emotion, and behaviour.