An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Anxiety, depression and stress in pregnancy: implications for mothers, children, research, and practice

Purpose of review.

To briefly review results of the latest research on the contributions of depression, anxiety, and stress exposures in pregnancy to adverse maternal and child outcomes, and to direct attention to new findings on pregnancy anxiety, a potent maternal risk factor.

Recent findings

Anxiety, depression, and stress in pregnancy are risk factors for adverse outcomes for mothers and children. Anxiety in pregnancy is associated with shorter gestation and has adverse implications for fetal neurodevelopment and child outcomes. Anxiety about a particular pregnancy is especially potent. Chronic strain, exposure to racism, and depressive symptoms in mothers during pregnancy are associated with lower birth weight infants with consequences for infant development. These distinguishable risk factors and related pathways to distinct birth outcomes merit further investigation.

This body of evidence, and the developing consensus regarding biological and behavioral mechanisms, sets the stage for a next era of psychiatric and collaborative interdisciplinary research on pregnancy to reduce the burden of maternal stress, depression, and anxiety in the perinatal period. It is critical to identify the signs, symptoms, and diagnostic thresholds that warrant prenatal intervention and to develop efficient, effective and ecologically valid screening and intervention strategies to be used widely.

INTRODUCTION

For more than a decade, psychiatry and related disciplines have been concerned about women experiencing symptoms of anxiety and depression during pregnancy and in the months following a birth. Current Opinion in Psychiatry alone published relevant reviews in 1998, 2000, 2004, 2007, 2008, 2009, and 2011, usually addressing the clinical management of postpartum depression or the effects of antidepressant use on mothers and their babies. Meanwhile, a parallel literature has grown rapidly in other health disciplines, especially behavioral medicine, health psychology, and social epidemiology, regarding stress in pregnancy and the implications for mothers, infants, and development over the life course. The purpose of this article is to briefly review results of the latest research on effects of negative affective states (referring throughout to anxiety and depression) and stress exposures in pregnancy, mainly regarding effects on birth outcomes. We direct attention specifically to recent research on pregnancy anxiety, a newer concept that is among the most potent maternal risk factors for adverse maternal and child outcomes [ 1■■ ]. By highlighting these developments, we hope to encourage synthesis and new directions in research and to facilitate evidence-based practices in screening and clinical protocols.

Psychiatric research on pregnancy focuses mostly on diagnosable mental disorders, primarily anxiety, and depressive disorders [ 2 , 3 ] and somewhat on posttraumatic stress disorder following adverse life events or childbirth experiences. However, a large body of scientific research outside psychiatry provides extensive information on a wide range of clinical symptoms during pregnancy, as measured with screening tools such as the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), for example, the Beck Depression Inventory, or the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. Scores on these measures are sometimes dichotomized in order to create depressed/nondepressed groups of women as a proxy for diagnostic categories, but continuous scores of symptom severity are more often used in research. Symptoms typically show linear or dose–response associations with outcomes such as preterm birth (PTB), low birth weight (LBW), or infant abnormalities. Our current understanding of negative affective states in pregnancy is based largely on these studies of symptomatology, not investigations of confirmed diagnoses, perhaps because investigators lacked clinical expertise or funding to conduct diagnostic interviews. More studies of confirmed diagnoses would be helpful, particularly with larger samples and controlling for antidepressant medications and other relevant variables. Nonetheless, research findings on symptoms of anxiety and depression in pregnancy are informative for clinicians regarding prenatal screening, early detection, prevention, and treatment of perinatal mood disturbances among expecting and new mothers.

Estimates of the prevalence of depression during pregnancy vary depending on the criteria used, but can be as high as 16% or more women symptomatic and 5% with major depression [ 2 ]. Firm estimates for prenatal anxiety do not exist, nor is there agreement about appropriate screening tools, but past studies suggest that a significant portion of women experience prenatal anxiety both in general and about their pregnancy [ 1■■ , 3 ]. Evidence of high exposure to stress in pregnancy is more widely available, at least for certain subgroups of women. For example, a recent study of a diverse urban sample found that 78% experienced low-to-moderate antenatal psychosocial stress and 6% experienced high levels [ 4 ]. Some of the stressors that commonly affect women in pregnancy around the globe are low material resources, unfavorable employment conditions, heavy family and household responsibilities, strain in intimate relationships, and pregnancy complications.

A large body of research is now available regarding stress and affective states during pregnancy as predictors of specific pregnancy conditions and birth outcomes [ 5 , 6 ]. The most commonly studied are PTB (<37 weeks gestation) and LBW (≤2500 g). Both are of US and international significance due to high incidence in many parts of the world and also consequences for infant mortality and morbidity. It has been estimated that two-thirds of LBW infants are born preterm. Thus, there are likely to be both common and unique etiological pathways [ 1■■ , 7■■ ]. Current theoretical models emphasize biopsychosocial and cultural determinants and interactions of multiple determinants in understanding these birth outcomes [ 8 , 9■■ , 10 – 12 ].

STRESS IN PREGNANCY

The literature on stress in pregnancy and birth outcomes is reviewed in two subsections, one on PTB and the other on LBW.

Stress and preterm birth

More than 80 scientific investigations on stress and PTB were recently reviewed by Dunkel Schetter and Glynn [ 7■■ ], of which a majority had prospective designs, large samples, and validated measures, and were fairly well controlled for confounds such as medical risks, smoking, education, income, and parity. These studies can be grouped by the type of stress examined. Of the more than a dozen published studies assessing `major life events in pregnancy', a majority found significant effects; women who experienced major life events such as the death of a family member were at 1.4 to 1.8 times greater risk of PTB, with strongest effects when events occurred early in pregnancy. The majority of a second, smaller group of studies on catastrophic, community-wide disasters (e.g., earthquakes or terrorist attacks) also showed significant effects on gestational age at birth or PTB. A third small set of studies on chronic stressors, such as household strain or homelessness, all reported significant effects on PTB. Finally, a majority of past investigations on neighborhood stressors such as poverty and crime indicated significant effects on gestational age or PTB. In comparison, studies on daily hassles and perceived stress did not consistently predict PTB. Thus, of the many distinguishable forms of stress, many (but not all) contribute to the risk of PTB.

Stress and low birth weight

A second area of developing convergence concerns the effects of stress on infant birth weight and/or LBW, reviewed recently by Dunkel Schetter and Lobel [ 9■■ ]. Again these studies can be organized by type of stressor. Evidence suggests that `major life events' somewhat consistently predicted fetal growth or birth weight, whereas measures of `perceived stress' had small or nonsignificant effects. `Chronic stressors', however, have been even more robust predictors of birth weight. For example, unemployment and crowding predicted 2.0 to 3.8 times the risk of LBW among low-income women in one study [ 13 ]. An important source of chronic stress is `racism or discrimination' occurring both during the pregnancy and over a woman's lifetime [ 14 ]. Racism and discrimination contribute to birth outcomes independently of other types of stress [ 15 ]. A growing number of studies have demonstrated that racism and discrimination prospectively predict birth weight, particularly in African–American women [ 16 ]. Although this literature has focused mainly on women in the USA, it is relevant to minority women in other countries [ 17 ].

In summary, chronic strain, racism, and related factors such as neighborhood segregation are significant risk factors for LBW [ 18 ]. Of note, investigations of chronic stress and racism do not usually take into account depressive symptoms. Yet, depression may be an important mechanism whereby the effects of exposure to chronic stress and racism influence fetal growth and birth weight, likely via downstream physiological and behavioral mechanisms [ 9■■ ].

ANXIOUS AND DEPRESSED AFFECT IN PREGNANCY

Recent research on symptoms of anxiety and depression during pregnancy is reviewed similarly within two subsections distinguishing findings on PTB from those on LBW.

Affect and preterm birth

State anxiety during pregnancy significantly predicted gestational age and/or PTB in seven of 11 studies recently reviewed [ 7■■ ], but only in combination with other measures or in subgroups of the sample. More consistent effects have been found for `pregnancy anxiety' (also known as `pregnancy-specific anxiety' and similar to `pregnancy distress'). Pregnancy anxiety appears to be a distinct and definable syndrome reflecting fears about the health and well being of one's baby, of hospital and health-care experiences (including one's own health and survival in pregnancy), of impending childbirth and its aftermath, and of parenting or the maternal role [ 1■■ , 19 ]. It represents a particular emotional state that is closely associated with state anxiety but more contextually based, that is, tied specifically to concerns about a current pregnancy. Assessment of pregnancy anxiety has entailed ratings of four adjectives combined into an index (`feeling anxious, concerned, afraid, or panicky about the pregnancy [ 20 ]' or use of a 10-item scale reflecting anxiety about the baby's growth, loss of the baby, and harm during delivery, as well as a few reverse-coded items concerning confidence in having a normal childbirth) [ 21 ]. Other measures exist as well.

There is remarkably convergent empirical evidence across studies of diverse populations regarding the adverse effects of pregnancy anxiety on PTB or gestational age at birth [ 7■■ , 19 ]. More than 10 prospective studies have been conducted on this topic, all of which report significant effects on the timing of birth. An early study found that the 10-item scale scores combined with a standard measure of state anxiety predicted gestational age of the infant at birth, controlling for medical risk factors, ethnicity, education, and income; these results were also independent of the effects of a woman's personal resources (sense of mastery, self-esteem, and dispositional optimism) [ 21 ]. Use of multidimensional modeling techniques later revealed that state anxiety, pregnancy anxiety, and perceived stress all predicted the length of gestation, but pregnancy anxiety (as early as 18 weeks into pregnancy) was the only significant predictor when all three indicators were tested together with medical and demographic risks controlled [ 20 ]. At least three large, well controlled, prospective studies have replicated these results using similar pregnancy anxiety measures [ 22 – 24 ]. The largest of these was a prospective study of 4 885 births finding that women with high pregnancy anxiety were at 1.5 times greater risk of a PTB, controlling for socio-demographic covariates, medical and obstetric risks, and specific worries over a high-risk condition in pregnancy [ 23 ].

In sum, recent evidence is remarkably convergent, indicating that pregnancy anxiety predicts the timing of delivery in a linear manner. Further, pregnancy anxiety predicts risk of spontaneous PTB with meaningful effect sizes across studies, comparable to or larger than effects of known risk factors such as smoking and medical risk. These effects hold for diverse income and ethnic groups in the USA and in Canada. The consistency of these findings paves the way for investigating the antecedents and correlates of pregnancy anxiety, mechanisms of effects, and available treatments.

In contrast, relatively few of the more than a dozen studies on depressed mood or symptoms of trauma found significant effects on gestational age or PTB [ 9■■ ]. A Swedish study found that elevated antenatal depressive symptoms predicted increased risk for PTB [odds ratio (OR) = 1.56] [ 25 ], and a recent meta-analysis concluded that PTB was associated with depression across 11 studies. However, in general, effect sizes were relatively small across studies with an average OR of 1.13 [confidence interval (CI 1.07–1.30)] [ 26 ].

Affect and low birth weight

Recent evidence points more often to the role of maternal depressive symptoms in the etiology of LBW as compared with the etiology of PTB [ 27■■ ]. The recent meta-analysis on depression in pregnancy, cited earlier, evaluated 20 studies and found that high depressive symptoms were associated with 1.4 to 2.9 times higher risk of LBW in undeveloped countries, and 1.2 times higher risk on average in the USA [ 26 ]. Another recent review found relatively large effects of maternal depressive symptoms on infant birth weight across several studies, with the largest effects for low-income or low social status women and women of color [ 9■■ ]. Furthermore, although there are few studies on diagnosed disorders, one study reported that mothers with a depressive disorder had 1.8 times greater risk of giving birth to a LBW infant [ 28 ]. Thus, evidence appears to be stronger for contributions of depressive symptoms or disorder to slower growth of the fetus and LBW than to the timing of delivery or PTB, and these effects are pronounced for disadvantaged women [ 29 ]. In contrast, very few studies have demonstrated any effects of anxiety on LBW, with rare exceptions [ 30 ].

STRESS AND NEGATIVE AFFECTIVE STATES IN PREGNANCY AND INFANT OR CHILD OUTCOMES

Evidence for effects of maternal stress, depression, and anxiety in pregnancy on adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes for the child is substantial [ 31 ], through a process known as `fetal programming' [ 5 , 32 ]. Research utilizing animal models indicates that maternal distress negatively influences long-term learning, motor development, and behavior in offspring [ 33 , 34 ]. Evidence suggests that this occurs via effects on development of the fetal nervous system and alterations in functioning of the maternal and fetal hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axes [ 34 – 36 ]. Maternal mood disorders have also been shown to activate the maternal HPA axis and program the HPA axis and physiology of the fetus [ 37 , 38 ]. In short, a mother's stress exposure and her affective states in pregnancy may have significant consequences for her child's subsequent development and health [ 5 , 39 – 43 ]. This evidence has been reviewed in many articles and spans effects on attention regulation, cognitive and motor development, fearful temperament, and negative reactivity to novelty in the first year of life; behavioral and emotional problems and decreased gray matter density in childhood; and impulsivity, externalizing, and processing speed in adolescents [ 44 – 47 ]. Of note, many of these findings involve the effects of prenatal pregnancy anxiety on infant, child, or adolescent outcomes. Maternal stress has also been linked to major mental disorders in offspring [ 40 , 47 ].

SUMMARY AND KEY ISSUES

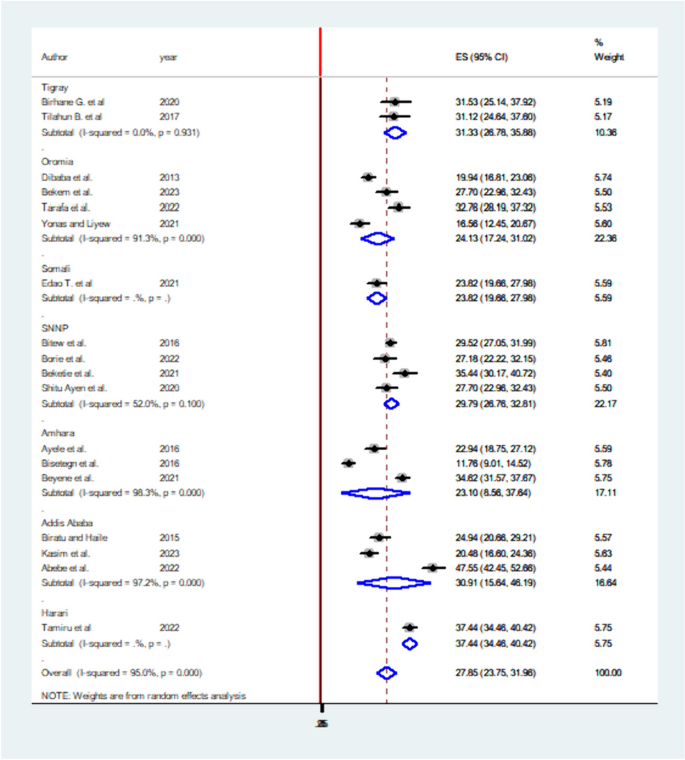

In summary, there is substantial evidence that anxiety, depression, and stress in pregnancy are risk factors for adverse outcomes for mothers and children. More specifically, anxiety in pregnancy is associated with shorter gestation and has adverse implications for fetal neurodevelopment and child outcomes. Furthermore, anxiety about a particular pregnancy seems to be especially potent. Finally, chronic strain, exposure to racism, and depressive symptoms in mothers during pregnancy are associated with lower birth weight infants with consequences for development as well. These differential risk factors and related pathways to PTB and LBW deserve further investigation. Beyond this, women with high stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in pregnancy are more likely to be impaired during the postpartum period. Postpartum affective disturbance and stress in turn impair parenting quality and effectiveness [ 48 ]. Figure 1 summarizes the evidence that has been briefly reviewed in a simple schematic with connections in bold representing those with notably stronger and more consistent evidence. This simple diagram can be elaborated further to include associations among the various types or forms of stress and to include mediated pathways to birth outcomes. For example, major life events or community catastrophes can be hypothesized to increase pregnancy anxiety, and long-term chronic strain to increase risk of depression. The effects of chronic strain on LBW via depression are also not depicted but are worthy of further research. Together, the evidence and developing consensus that biological and behavioral mechanisms explain these findings lay the groundwork for a next era of psychiatric and collaborative interdisciplinary research on pregnancy.

Summary of evidence on depression, anxiety and stress. GA, gestational age at birth; LBW, low birth weight; PTB, preterm birth.

Why pregnancy anxiety?

It is not clear why `pregnancy anxiety' has such powerful effects on mothers and their babies. In fact, the nature of this concept has not yet received sufficient attention to be fully explicated. Possibly what makes it potent is that measures of pregnancy anxiety capture both dispositional characteristics, or traits, and environmentally influenced states. For example, women who are most anxious about a pregnancy seem to be more insecurely attached, of certain cultural backgrounds, more likely to have a history of infertility or to be carrying unplanned pregnancies, and have fewer psychosocial resources [ 49 ]. These results suggest that existing vulnerabilities that predate pregnancy may interact with the social, familial, cultural, societal, and environmental conditions of pregnancy to increase levels of pregnancy anxiety, producing effects on the maternal–fetal–placental systems, especially during sensitive periods such as early pregnancy. This process can then adversely influence fetal development by programming the fetus's HPA axis and also have effects on the initiation of labor via maternal, fetal, and placental hormonal exchanges. Although there is much we do not know, a worthwhile future goal for clinical researchers may be to identify women high in anxiety before conception, as well as women high in anxiety during pregnancy, and especially those women who are anxious about specific aspects of their pregnancies – about this child and this birth, and about competently parenting with this partner. These women would appear to be targets for early intervention such as evidence-based interventions for stress reduction, mood regulation treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapies, pharmacological treatments, and follow-up care during postpartum to prevent a range of adverse outcomes for mother, child, and family.

Clinical screening for affective symptoms in pregnancy

Clinical screening for depression or anxiety in prenatal and postpartum healthcare has been widely recommended but is also potentially problematic. The issues concern what screening tools to use; what cutoffs to adopt for identifying women at risk; the need for expert clinicians to follow up on those women who score above thresholds to make diagnoses; and, for those who have established diagnoses, the availability of affordable and efficacious treatments [ 50 ]. These issues must be resolved for prenatal (and postpartum) clinical screening to be recommended widely. For example, the EPDS, which is a gold standard used widely in clinic settings for depression screening both prepartum and postpartum, actually measures both depressive and anxiety symptoms, which may contribute to confusion about risks [ 51 ]. In addition, experts have questioned the validity of a diagnosis of depressive disorders using standard diagnostic criteria for mood disturbance because they include typical somatic symptoms of pregnancy such as fatigue, sleep disturbance, and appetite changes [ 52 ]. Also relevant is one recent study reporting that women with both depression and anxiety disorders were at highest risk of LBW, as compared with those with only depressive or anxious symptoms or none [ 53 ]. Combinations of symptoms have received very little research attention. Furthermore, little research thus far has examined the feasibility and utility of screening for prenatal stress or pregnancy anxiety.

If broad screening for affective symptoms during pregnancy results in high rates of false-positive results, low rates of clinical follow-up and referral, insufficient or ineffective education for women about the meaning of screening results, lack of treatment, and/or absence of proven evidence-based interventions, then clinical screening as a standard procedure in specific prenatal settings is of questionable value. Nonetheless, if important preconditions can be met, screening for pregnancy anxiety, state anxiety, depressive symptoms, and stress in pregnancy stands to provide potentially important clinical benefits for mothers and their children [ 54 , 55 ].

The broader context of pregnancy

An essential consideration in implementing widespread effective prenatal screening, diagnosis, and treatment is the context of a woman's pregnancy. The context includes her partner, family, friends, neighborhood, and larger community, all of which are known to influence a woman's mental health and responses to a diagnosis of disorder. Therefore, attention must be paid to these levels of influence in any attempts to screen and treat depression, anxiety, pregnancy anxiety, or stress in pregnancy. For example, a woman's ability to understand or respond to a diagnosis of a mood or anxiety disorder and accept treatment may be facilitated by involving her partner, closest relative, or friend in follow-up after screening. Families and communities can undermine or enhance efforts to screen and treat women in pregnancy as a result of their beliefs, values, and level of information (or misinformation). Although these issues are known barriers to community mental health treatment in diverse populations, they have not yet been addressed in establishing appropriate clinical procedures in pregnancy for follow-up of widespread screening for affective disorders. It may also be useful to identify a range of protective and resilience factors such as mastery, self-efficacy and social support in women for the purpose of intervention planning [ 2 , 56■■ ]. If efforts are directed to strengthening women's psychosocial resources as early as possible, ideally before conception, it is possible that prenatal health and outcomes could be better optimized.

In conclusion, although considerable, rigorous research now demonstrates the potential deleterious effects of negative affective states and stress during pregnancy on birth outcomes, fetal and infant development, and family health, we do not yet have a clear grasp on the specific implications of these facts. Key issues for the next wave of research are as follows: disentangling the independent and comorbid effects of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, pregnancy anxiety, and various forms of stress on maternal and infant outcomes; better understanding the concept of pregnancy anxiety and how to address it clinically; and further investigating effects of clinically significant affective disturbances on maternal and child outcomes, taking into account a mother's broad socio-environmental context. As our knowledge increases, it will be critical to identify the signs, symptoms, and diagnostic thresholds that warrant prenatal intervention and to develop efficient, effective, and ecologically valid screening and intervention strategies to be used widely. If risk factors can be identified prior to pregnancy and interventions designed for preconception, many believe this window of opportunity is our best bet [ 57 ]. Interdisciplinary research and collaboration will be crucial, however, to meeting these objectives and in order to reduce the burden of maternal stress, depression, and anxiety in the perinatal period.

- Anxiety, depression, and stress in pregnancy are risk factors for adverse outcomes for mothers and children.

- Anxiety regarding a current pregnancy (`pregnancy anxiety') is associated with shorter gestation and has adverse implications for preterm birth, fetal neurodevelopment and child outcomes.

- Chronic strain (including long-term exposure to racism) and depressive symptoms in mothers during pregnancy are associated with lower birth weight with many potential adverse consequences.

- These distinguishable risk factors and related pathways to distinct birth outcomes merit further investigation.

- It is critical to agree upon the signs, symptoms and diagnostic thresholds that warrant prenatal intervention and to develop efficient, effective, and ecologically valid screening and intervention strategies that can be used widely.

Acknowledgements

The contributions of collaborators Laura Glynn, PhD, Calvin Hobel, MD, and Heidi Kane, PhD to this program of work are gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of interest There are no conflicts of interest .

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as: ■ of special interest ■■ of outstanding interest Additional references related to this topic can also be found in the Current World Literature section in this issue (p. 162).

Depression During Pregnancy

Medical review policy, latest update:.

Updates throughout to text, information, and sources, plus a new medical review.

Recommended Reading

What are the risk factors for depression in pregnancy, what causes depression during pregnancy, what are the symptoms of depression during pregnancy, can depression during pregnancy affect your baby, treatments for pregnancy depression, 1. non-drug treatments, 2. antidepressants, can you prevent pregnancy depression.

Taking action is the first step towards protecting your mental health so you can feel better — and give you and your baby the best possible start together.

Updates history

Jump to your week of pregnancy, trending on what to expect, signs of labor, pregnancy calculator, ⚠️ you can't see this cool content because you have ad block enabled., top 1,000 baby girl names in the u.s., top 1,000 baby boy names in the u.s., braxton hicks contractions and false labor.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Depression During and After Pregnancy Can Be Prevented, National Panel Says. Here’s How.

The task force of experts recommended at-risk women seek certain types of counseling, and it cited two specific programs that have been particularly effective.

By Pam Belluck

As many as one in seven women experience depression during pregnancy or in the year after giving birth. Now, for the first time, a national panel of health experts says there is a way to prevent it.

Some kinds of counseling can keep some women from developing debilitating symptoms that can harm not only them but their babies, the panel reported on Tuesday. Its report amounted to a public call for health providers to seek out women with certain risk factors and guide them to counseling programs. The recommendation, by the United States Preventive Services Task Force , means that insurers will be required to cover those services — with no co-payments — under the Affordable Care Act.

“We really need to find these women before they get depressed,” said Karina Davidson, a task force member and senior vice president for research for Northwell Health.

[ Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter. ]

Perinatal depression , as it is called, is estimated to affect between 180,000 and 800,000 American mothers each year and up to 13 percent of women worldwide . The condition increases a woman’s risk of becoming suicidal or harming her infant, the panel reported. It also increases the likelihood that babies will be born premature or have low birth weight, and can impair a mother’s ability to bond with or care for her child. The panel reported that children of mothers who had perinatal depression have more behavior problems, cognitive difficulties and mental illness.

The panel emphasized that perinatal depression is shouldn’t be confused with “baby blues” — the tears, irritability, fatigue, and anxiety that many women experience after delivery but which evaporates within 10 days.

The panel evaluated research on numerous possible prevention methods , including physical activity, education, infant sleep advice, yoga, expressive writing, omega-3 fatty acids and antidepressants. Several showed some promise, including physical activity and programs in Britain and the Netherlands involving home visits by midwives or other providers. But only counseling demonstrated enough scientific evidence of benefit.

Women receiving one of two forms of counseling were 39 percent less likely than those who didn’t to develop perinatal depression. One approach involved cognitive behavioral therapy, helping women navigate their feelings and expectations to create healthy, supportive environments for their children. The other involved interpersonal therapy, including coping skills and role-playing exercises to help manage stress and relationship conflicts.

“This recommendation is really important,” said Jennifer Felder, an assistant professor of psychiatry at University of California, San Francisco, who was not on the panel. “This focuses on identifying women who are at risk for depression and proactively preventing its onset, using concrete guidelines.”

The panel recommended counseling for women with one or more of a broad range of risk factors, including a personal or family history of depression; recent stresses like divorce or economic strain; traumatic experiences like domestic violence; or depressive symptom s that don’t constitute a full-blown diagnosis. Others include being a single mother, a teenager, low-income, lacking a high school diploma, or having an unplanned or unwanted pregnancy, panel members said.

It highlighted two specific programs, which were similarly successful, Dr. Davidson said. They counsel first-time mothers and those who already have children. They are available in Spanish and focus on low-income women, about 30 percent of whom develop perinatal depression, experts say.

One program, “ Mothers and Babies ,” includes cognitive behavioral therapy in eight to 17 group sessions, often delivered in clinics or community health centers, primarily during pregnancy with at least two sessions postpartum.

“It’s really meant to break down this idea that talking about your thoughts and behaviors is scary,” said Darius Tandon, an associate professor at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and principal investigator of several “Mothers and Babies” studies.

So far, health and human service agencies in over 175 counties in 21 states have been trained to implement the program. It is also being evaluated in Florida and the Midwest to see if it works when administered one-on-one by home visiting caseworkers instead of groups run by psychologists or social workers, Dr. Tandon said.

The other program, “ Reach Out, Stay Strong, Essentials for New Moms ” or ROSE, typically delivered in four sessions during pregnancy and one postpartum, can be administered in groups or one-on-one by nurses, midwives or anyone trained to follow the manual, said Jennifer Johnson, a professor of public health at Michigan State University.

So far, women in Rhode Island, Mississippi and Japan have participated, said ROSE’s creator, Caron Zlotnick, a professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University. She and Dr. Johnson are testing its expansion to 90 clinics throughout the country.

Karla Manica, 30, a single mother of four in Detroit, participated in “Mothers and Babies” when pregnant with her youngest, who is now 1. She said she experienced abuse as a child and in relationships, attempted suicide by drinking cleaner, lived in homeless shelters after being laid off from her job as a dementia caregiver, and has had bipolar depression.

“It was good to come to the table and share,” Ms. Manica said. The counselor texted uplifting messages between sessions, and “homework assignments” to engage in stress-relieving activities were useful. When Ms. Manica learned her baby’s father had another girlfriend, she said, the group “gave me hope.”

After her daughter Kathryn was born, “I was well,” Ms. Manica said. “If I hadn’t got with the Mothers and Babies, would I have been prepared, would I have gotten the confidence I have now? No.”

Experts and leaders of the programs, whose curriculums and counselor training are free, said financial and other obstacles exist.

“Cost is definitely still an issue,” said Dr. Tandon. He said one prenatal session costs clinics delivering the counseling $40 to $50 to provide mothers’ transportation and child care, and Medicaid doesn’t have a reimbursement code for preventive counseling, so clinics often absorb the cost of staff time to provide it.

Access to counseling also can be difficult. “Especially when you’re pregnant and you have competing demands on your time and energy, or if you have a little one at home,” said Dr. Felder, who wrote an editorial about the recommendation. Offering it online or through apps may help.

Even in some cases in which it doesn’t prevent depression, counseling may be beneficial, said Dr. Melissa Simon, a task force member and vice chairwoman of research at Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine’s obstetrics and gynecology department. “It provides the pregnant person with education and coping strategies,” she said, and can encourage those who develop depression to seek treatment faster.

Captoria Porter, 28, of Bolingbrook, Ill., who has seven children, ages 2 months to 11, experienced no depression during or after her first five pregnancies. But during her sixth, life became more tumultuous, with marital problems and the need to move in with her sister because the housing project where she was living was closing.

After the birth of Myla, now 1, “I think I had symptoms of depression,” said Ms. Porter, who has worked as a telemarketer selling sanitizer dispensers. “I was really sad.”

Fortunately, the pre-birth “Mothers and Babies” sessions helped her recognize signs like “you don’t want to brush your hair or you don’t want to be bothered with the baby,” she said. “I would find myself feeling that way.”

Ms. Porter met twice with a community center counselor, but realized the program had already taught her the practices he recommended: “Reaching out to family and friends. Learning that I can’t control everything. Eating when the baby eats, sleeping when the baby sleeps, laying the kids down for a nap and calling it ‘me time.’”

That warded off full-blown depression. “I caught it early,” she said.

The panel encouraged more research on all prevention approaches. In reviewing 50 studies of various methods, it found negative effects only in the two small studies with antidepressants. One study reported instances of dizziness and drowsiness among women who took Zoloft. The other reported that more women taking Pamelor experienced constipation.

“Some people have asked, ‘Why aren’t you just recommending antidepressants?’” Dr. Davidson said. “Of course, antidepressants were developed and studied for someone who has depression. We need to consider possible benefits and possible harms to parent and fetus when someone is not depressed and you’re giving them a drug to treat depression on the off-chance it prevents depression.”

Beth Sanfratel, 43, a preschool teacher in Birmingham, Ala., said she wished she’d had a counseling program when pregnant with the second of three sons, Mac, now 10.

“I don’t even think postpartum depression was mentioned,” she said. Several months after Mac was born, Ms. Sanfratel, usually upbeat and social, said she began having crying spells. “I was having trouble getting up and in general just being really bummed out.”

Ultimately, Ms. Sanfratel, a former social worker, recognized she needed help and took antidepressants for about a year, resuming them shortly before her third son, Beau, was born in 2011.

“Getting moms figuring out what’s going on ahead of the actual delivery, it’s a great, great thing,” she said.

Pam Belluck is a health and science writer whose honors include sharing a Pulitzer Prize and winning the Nellie Bly Award for Best Front Page Story. She is the author of Island Practice, a book about an unusual doctor. More about Pam Belluck

Pregnancy, Childbirth and Postpartum Experiences

Aspirin’s Benefits: Not enough pregnant women at risk of developing pre-eclampsia, life-threatening high blood pressure, know that low-dose aspirin can help lower that risk. Leading experts are hoping to change that.

‘A Chance to Live’: Cases of trisomy 18 may rise as many states restrict abortion. Some women have chosen to have these babies , love them tenderly and care for them devotedly.

Teen Pregnancies: A large study in Canada found that women who were pregnant as teenagers were more likely to die before turning 31 .

Weight-Loss Drugs: Doctors say they are seeing more women try weight-loss medications in the hopes of having a healthy pregnancy. But little is known about the impact of those drugs on a fetus.

Premature Births: After years of steady decline, premature births rose sharply in the United States between 2014 and 2022. Experts said the shift might be partly the result of a growing prevalence of health complications among mothers .

Depression and Suicide: Women who experience depression during pregnancy or in the year after giving birth have a greater risk of suicide and attempted suicide .

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

7 Depression During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period

Shaila Misri, M.D., Reproductive Mental Health Program, B.C. Children’s and Women’s Hospital, St. Paul’s Hospital; Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia; and B.C. Mental Health and Addiction Services, Provincial Health Services Authority.

Jasmin Abizadeh, Reproductive Mental Health Program, B.C. Children’s and Women’s Hospital, St. Paul’s Hospital; Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia; and B.C. Mental Health and Addiction Services, Provincial Health Services Authority.

Sonya Nirwan, Reproductive Mental Health Program, B.C. Children’s and Women’s Hospital, St. Paul’s Hospital.

- Published: 05 December 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Depression affects 9–13% of pregnant women and 12–16% of postpartum women. Rates vary depending on whether depressive symptoms or DSM diagnoses of depression are considered. Risk factors of perinatal depression include socioeconomic status, social support, personality style, personal and family history of depression, and hormonal changes. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) is a self-report instrument commonly used to assess for perinatal depression. The treatment of perinatal depression with antidepressant medication is controversial. Most guidelines recommend psychotherapy for mild to moderate depression and medication for moderate to severe depression. Established psychotherapies include interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy, as well as alternative therapies such as infant massage in the postpartum. Although extensive research on perinatal depression has been conducted over the past two decades, future research could include designing prospective, methodologically sound studies with larger samples to compare treatment modalities, teratogenicity associated with pharmacotherapy, and prevalence of perinatal depression in various cultures.

Although the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) includes the specifier “with peripartum onset” for a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD), it does not acknowledge postpartum depression (PPD) with an onset beyond 4 weeks ( American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013 ). The revisions however from the DSM-IV to the DSM-5 now account for MDD during pregnancy compared to just a postpartum onset before. In clinical practice, PPD has been noted to occur at any time within the first 12 months following childbirth. Terms used synonymously to describe perinatal depressive illness include antenatal or prenatal depression (i.e., depression during pregnancy) and postpartum or postnatal depression (i.e., depression after childbirth). In this chapter, we use all of these terms.

Perinatal Prevalence Rates

In pregnancy, depressive symptoms generally have a prevalence rate of 20%, whereas MDD during this time period ranges from 9–13% ( Bowen & Muhajarine, 2006 ; Faisal-Cury & Rossi Menezes, 2007 ; Marcus, Flynn, Blow, & Barry, 2003 ). The rate of 13% in pregnancy is based on a meta-analysis of 30 studies by Gaynes et al. (2005) . The National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) yielded a figure of 12.4% in 1,524 women, whereas the lower rate of 9% was found in a smaller study of 326 women ( Benute et al., 2010 ; Le Strat, Dubertret, & Le Foll, 2011 ). Although the rates of subclinical depressive symptoms may be higher in the pregnant population, the reported rates of MDD in pregnancy are not dissimilar to those reported in the non-childbearing population (7–13% of the global female population; Blehar, 2001 ; Berardi et al., 2002 ; Lepine, Gastpar, Mendlewicz, & Tylee, 1997 ; Statistics Canada, 2002 ).

Furthermore, some studies have described a variation of rate in each trimester, whereas others do not. In their systematic review of the literature, Bennett, Einarson, Taddio, Koren, and Einarson (2004) described a depression prevalence rate of 7.4% in the first, 12.8% in the second, and 12.0% in the third trimesters on the basis of observational studies and surveys using validated screening instruments. The authors cautioned interpretation of the lower rate of 7.4% in the first trimester due to the availability of few studies and the small number of study participants. Clinically, the underreporting of depression in the first trimester is not uncommon due to the symptom overlap between signs of pregnancy and symptoms of depressive illness specifically in primiparous women. The higher prevalence rates in the second and third trimester may be a reflection of greater demands of advancing pregnancy being responsible for increasing the risk of depression. Another explanation for why depression rates may peak in the second and third trimester is that women are more likely to seek medical care in the second and third trimester than in the first, so those at risk may be more easily identified ( Kelly et al., 1999 ). Other authors have found a peak in the first trimester only, including findings from two longitudinal studies by Kitamura, Shima, Sugawara, and Toda (1993 ; n = 120), which used a structured diagnostic interview to identify depression, and Kumar and Robson (1984 ; n = 119), which used a semistructured interview as well as a self-rated questionnaire. Lastly, a study by Ancill, Hilton, Carr, Tooley, and McKenzie (1986) found a peak only in the third trimester using a similar sample size ( n = 108) and a prospective longitudinal design. Authors of this paper cautioned that the higher prevalence of third-trimester depression could have resulted from the misidentification of physical discomforts of pregnancy as somatic signs of depression in pregnancy, as identified with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D; Hamilton, 1960 ).

There is an increased rate of depressive symptoms in the postpartum period (i.e., 19.2%) in comparison to MDD, where the most commonly cited rate is between 12% and 16% ( Gavin et al. 2005 ; Mori et al., 2011 ; O’Hara & Swain, 1996 ). Variability in prevalence rates depends on whether researchers report depressive symptoms or the diagnosis of MDD. Additional factors that affect the variation of the reported rate in postpartum women include methodological differences (e.g., prospective vs. retrospective design), the use of different screening measures, differences in the definition of depression, and the onset of the episode. PPD can occur early or late in the first 12 months after childbirth. In a prospective study, Mori et al. (2011) showed that the prevalence rate of PPD was 11% for early onset and 4% for late onset when using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987 ) as the screening instrument.

PPD rates also fluctuate as a function of the country in which the epidemiological data are collected ( Goldbort, 2006 ; Halbreich & Karkun, 2006 ). Halbreich and Karkun (2006) reviewed 143 studies of postpartum prevalence in 40 countries and found a range of 0% to 60%, concluding that the frequently reported range of 10–15% is not representative of the rates worldwide. Researchers examining depression in countries such as Singapore (0.5%), Malta (3.9%), Malaysia (3.9%), Austria (5.0%), and Denmark (5.5%) reported a much lower rate in comparison to researchers examining depression in Brazil (42.8%), Guyana (57.0%), Costa Rica (34.0–48.0%), Italy (38.1%), Chile (37.4%), South Africa (36.5%), Taiwan (34.5%), and Korea (36.1–48.0%).

The disparity in findings may have been due to cultural issues surrounding the conceptualization of mental illness, accompanying stigma, differences in reporting style, and socioeconomic/biological vulnerability factors; for example, the term PPD may be unknown or unacceptable to some non-Western cultures, and the Western diagnostic standards may not be applicable to other cultures ( Posmontier & Horowitz, 2004 ). Specifically, Asian women tend to express depression in somatic terms versus affective symptoms. This may contribute to overdiagnosis if a questionnaire is used that assesses affective and somatic symptoms; it may lead to underdiagnosis if the clinician does not interpret the somatic symptoms as an expression of PPD ( Lee, Yip, Chiu, Leung, & Chung, 2001 ; Park & Dimigen, 1995 ; Yoshida et al., 1997 ). For example, Japanese women may be more likely to focus on their physical problems instead of their depression, and Chinese women may be more likely to complain about physical symptoms, such as “wind inside the head” or head numbness, to describe their depression ( Lee et al., 2001 ; Yoshida et al., 1997 ). Reported rates of depression may vary from one culture to another depending on the perceived stigma, the reporting style, and varying cutoff scores on a screening tool ( Dankner, Goldberg, Fisch, & Crum, 2000 ; Stuchbery, Matthey, & Barnett, 1998 ). In addition, in their view, Halbreich and Karkun (2006) concluded that certain rituals, recognition of role transition, and the mobilization of support and help for the new mother may serve as protective factors for PPD, as seen among Koreans, Chinese, Japanese, Mexicans, Nigerians, and others. In Western culture, mothers have little time to recover from childbirth, are often socially isolated, and are expected to juggle multiple roles soon after delivery, which could contribute to an increased prevalence of PPD.

The course of perinatal depression is affected by the age of onset, time of onset, hormonal changes, severity of symptoms, duration of illness, and the number of previous episodes. In addition, psychiatric and medical/obstetric comorbidities govern the course of perinatal depression. The age of onset of MDD for females is in their early 20s to 30s, and peak incidence occurs at 30 years, which falls during the childbearing years ( Eaton et al., 1997 ; Weissman et al., 1996 ). Early onset of the disease leads to repeated relapses and recurrences throughout life and the reproductive period, particularly if the first episode occurs before 18 years of age ( Coryell et al., 2009 ; Klein et al., 1999 ; Zisook et al., 2007 ).

Hormonal changes throughout the female life cycle have a crucial effect on the emergence and progression of the mood disorder. After menarche, the mood changes can present as premenstrual symptoms and, in severe cases, may meet the DSM-5 criteria for a mood disorder called premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD; Biggs & Demuth, 2011 ; Gonda et al., 2008 ). PMDD may increase the risk of PPD and affect the course of depression in the perinatal period as a result. One study prospectively diagnosed postpartum mood disorders in women and also retrospectively reported PMDD in two groups of women, identified as either at low risk ( n = 109) or at high risk of postpartum mood disorders ( n = 133; Bloch, Rotenberg, Koren, & Klein, 2005 ). Results showed that 23% of women with PMDD also experienced depression in the postpartum period. Pregnancy and childbirth is a time of highest vulnerability, with rapid hormonal escalation and decline ( Marcus, 2009 ). Repeated pregnancies and childbirths increase the frequency and duration of the illness. Those with a history of PPD with the first child have a 25–50% recurrence of the disease with their second pregnancy ( Altshuler, Hendrick, & Cohen, 1998 ). In one study, multiparous depressed women were found to be at an increased risk for experiencing the depressive episode more intensely than primiparous women ( Righetti-Veltema, Conne-Perréard, Bousquet, & Manzano, 2002 ).

Another important factor that impacts the course of perinatal depressive illness is the presence of a personality disorder. Women with MDD and a personality disorder have more frequent episodes lasting more than 1 year, inadequate response to pharmacotherapy, and poorer recovery after hospital discharge compared to those with MDD but no personality disorder ( Black, Bell, Hulbert, & Nasrallah, 1988 ; Newton-Howes, Tyrer, & Johnson, 2006 ). In another study in which depressive symptoms and personality disorder were assessed in postpartum women at 6 weeks and 12 months after childbirth, those with dependent and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (71.4%) were more depressed compared to those without these disorders (5%; Uguz, Akman, Sahingoz, Kaya, & Kucur, 2009 ). In this study, the presence of the personality disorder alone was an independent predictor of PPD at 1-year follow-up. Thus, it seems that women with personality disorders have more severe and persistent depression than do those without personality disorders.

Treatment of depression also impacts its course. The average length of an untreated episode can last between 6 and 12 months, as shown by a cross-national epidemiologic survey involving about 38,000 community subjects across 10 different countries ( Weissman et al., 1996 ). Even after treatment, relapse rates may be high and occur quickly. In a naturalistic study of depressed patients, 12% relapsed within 4 weeks after recovery from an episode of depression and 25% relapsed within 12 weeks ( Keller, Shapiro, Lavori, & Wolfe, 1982 ).

Correlates and Risk Factors

Demographic and socioeconomic risk factors.

The NESARC reported that relationship status significantly correlates with perinatal depression. Specifically, depressed pregnant women were 2.05 times more likely to be never married and 3.30 times more likely to be widowed, divorced, or separated ( Le Strat et al., 2011 ).

In addition, socioeconomic status (SES) is an important risk factor related to depression. However, not all aspects of SES are associated with depressive illness, as findings have been mixed. For example, lower income and lower educational level were related to depressive symptoms, whereas unemployment was not related to depressive symptoms in a meta-analysis of studies that evaluated associations between prenatal depressive symptoms and risk factors ( Lancaster et al., 2010 ).

Melville, Gavin, Guo, Fan, and Katon (2010) found ethnicity to be also a major risk factor in pregnant women, with Asian and African Americans having a 2.98- to 5.81-fold increased risk. There was a 2.50-fold greater propensity for Hispanic women. In addition, age is another factor that can impact PPD, with a U-shaped pattern showing an increased association of PPD with younger and older maternal age ( Milgrom et al., 2008 ; Mori et al., 2011 ).

Thus, the existing literature suggests that whereas the correlation between SES and depression is mixed, ethnicity, age, and relationship status appear to have a clearer association. It is important to be aware of demographic and socioeconomic variables as potential risk factors for perinatal depression and evaluate their impact for each patient.

Psychosocial Risk Factors

Numerous psychological and social factors that can affect perinatal depression include life stressors, situational stressors, presence of social support, quality of relationships, and personality traits. With regard to life stressors, one study reported that depressed women who were pregnant in the past year had a 2.59 to 9.15 greater likelihood of reporting at least one stressful life event during their pregnancy compared to women who were pregnant but not depressed ( Le Strat et al., 2011 ). In their review, Lancaster et al. (2010) also found a medium association between increased life stress and antenatal depression in 18 studies assessing life events and daily hassles.