Critical Essay

Definition of critical essay.

Contrary to the literal name of “critical,” this type of essay is not only an interpretation, but also an evaluation of a literary piece. It is written for a specific audience , who are academically mature enough to understand the points raised in such essays. A literary essay could revolve around major motifs, themes, literary devices and terms, directions, meanings, and above all – structure of a literary piece.

Evolution of the Critical Essay

Critical essays in English started with Samuel Johnson. He kept the critical essays limited to his personal opinion, comprising praise, admiration, and censure of the merits and demerits of literary pieces discussed in them. It was, however, Matthew Arnold, who laid down the canons of literary critical essays. He claimed that critical essays should be interpretative, and that there should not be any bias or sympathy in criticism.

Examples of Critical Essay in Literature

Example #1: jack and gill: a mock criticism (by joseph dennie).

“The personages being now seen, their situation is next to be discovered. Of this we are immediately informed in the subsequent line, when we are told, Jack and Gill Went up a hill. Here the imagery is distinct, yet the description concise. We instantly figure to ourselves the two persons traveling up an ascent, which we may accommodate to our own ideas of declivity, barrenness, rockiness, sandiness, etc. all which, as they exercise the imagination, are beauties of a high order. The reader will pardon my presumption, if I here attempt to broach a new principle which no critic, with whom I am acquainted, has ever mentioned. It is this, that poetic beauties may be divided into negative and positive, the former consisting of mere absence of fault, the latter in the presence of excellence; the first of an inferior order, but requiring considerable critical acumen to discover them, the latter of a higher rank, but obvious to the meanest capacity.”

This is an excerpt from the critical essay of Joseph Dennie. It is an interpretative type of essay in which Dennie has interpreted the structure and content of Jack and Jill.

Example #2: On the Knocking at the Gate in Macbeth (by Thomas De Quincey)

“But to return from this digression , my understanding could furnish no reason why the knocking at the gate in Macbeth should produce any effect, direct or reflected. In fact, my understanding said positively that it could not produce any effect. But I knew better; I felt that it did; and I waited and clung to the problem until further knowledge should enable me to solve it. At length, in 1812, Mr. Williams made his debut on the stage of Ratcliffe Highway, and executed those unparalleled murders which have procured for him such a brilliant and undying reputation. On which murders, by the way, I must observe, that in one respect they have had an ill effect, by making the connoisseur in murder very fastidious in his taste, and dissatisfied by anything that has been since done in that line.”

This is an excerpt from Thomas De Quincey about his criticism of Macbeth, a play by William Shakespeare. This essay sheds light on Macbeth and Lady Macbeth and their thinking. This is an interpretative type of essay .

Example #3: A Sample Critical Essay on Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (by Richard Nordquist)

“To keep Jake Barnes drunk, fed, clean, mobile, and distracted in The Sun Also Rises, Ernest Hemingway employs a large retinue of minor functionaries: maids, cab drivers, bartenders, porters, tailors, bootblacks, barbers, policemen, and one village idiot. But of all the retainers seen working quietly in the background of the novel, the most familiar figure by far is the waiter. In cafés from Paris to Madrid, from one sunrise to the next, over two dozen waiters deliver drinks and relay messages to Barnes and his compatriots. As frequently in attendance and as indistinguishable from one another as they are, these various waiters seem to merge into a single emblematic figure as the novel progresses. A detached observer of human vanity, this figure does more than serve food and drink: he serves to illuminate the character of Jake Barnes.”

This is an excerpt from an essay written about Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises . This paragraph mentions all the characters of the novel in an interpretative way. It also highlights the major motif of the essay .

Functions of a Critical Essay

A critical essay intends to convey specific meanings of a literary text to specific audiences. These specific audiences are knowledgeable people. They not only learn the merits and demerits of the literary texts, but also learn different shades and nuances of meanings. The major function of a literary essay is to convince people to read a literary text for reasons described.

beginner's guide to literary analysis

Understanding literature & how to write literary analysis.

Literary analysis is the foundation of every college and high school English class. Once you can comprehend written work and respond to it, the next step is to learn how to think critically and complexly about a work of literature in order to analyze its elements and establish ideas about its meaning.

If that sounds daunting, it shouldn’t. Literary analysis is really just a way of thinking creatively about what you read. The practice takes you beyond the storyline and into the motives behind it.

While an author might have had a specific intention when they wrote their book, there’s still no right or wrong way to analyze a literary text—just your way. You can use literary theories, which act as “lenses” through which you can view a text. Or you can use your own creativity and critical thinking to identify a literary device or pattern in a text and weave that insight into your own argument about the text’s underlying meaning.

Now, if that sounds fun, it should , because it is. Here, we’ll lay the groundwork for performing literary analysis, including when writing analytical essays, to help you read books like a critic.

What Is Literary Analysis?

As the name suggests, literary analysis is an analysis of a work, whether that’s a novel, play, short story, or poem. Any analysis requires breaking the content into its component parts and then examining how those parts operate independently and as a whole. In literary analysis, those parts can be different devices and elements—such as plot, setting, themes, symbols, etcetera—as well as elements of style, like point of view or tone.

When performing analysis, you consider some of these different elements of the text and then form an argument for why the author chose to use them. You can do so while reading and during class discussion, but it’s particularly important when writing essays.

Literary analysis is notably distinct from summary. When you write a summary , you efficiently describe the work’s main ideas or plot points in order to establish an overview of the work. While you might use elements of summary when writing analysis, you should do so minimally. You can reference a plot line to make a point, but it should be done so quickly so you can focus on why that plot line matters . In summary (see what we did there?), a summary focuses on the “ what ” of a text, while analysis turns attention to the “ how ” and “ why .”

While literary analysis can be broad, covering themes across an entire work, it can also be very specific, and sometimes the best analysis is just that. Literary critics have written thousands of words about the meaning of an author’s single word choice; while you might not want to be quite that particular, there’s a lot to be said for digging deep in literary analysis, rather than wide.

Although you’re forming your own argument about the work, it’s not your opinion . You should avoid passing judgment on the piece and instead objectively consider what the author intended, how they went about executing it, and whether or not they were successful in doing so. Literary criticism is similar to literary analysis, but it is different in that it does pass judgement on the work. Criticism can also consider literature more broadly, without focusing on a singular work.

Once you understand what constitutes (and doesn’t constitute) literary analysis, it’s easy to identify it. Here are some examples of literary analysis and its oft-confused counterparts:

Summary: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” the narrator visits his friend Roderick Usher and witnesses his sister escape a horrible fate.

Opinion: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Poe uses his great Gothic writing to establish a sense of spookiness that is enjoyable to read.

Literary Analysis: “Throughout ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ Poe foreshadows the fate of Madeline by creating a sense of claustrophobia for the reader through symbols, such as in the narrator’s inability to leave and the labyrinthine nature of the house.

In summary, literary analysis is:

- Breaking a work into its components

- Identifying what those components are and how they work in the text

- Developing an understanding of how they work together to achieve a goal

- Not an opinion, but subjective

- Not a summary, though summary can be used in passing

- Best when it deeply, rather than broadly, analyzes a literary element

Literary Analysis and Other Works

As discussed above, literary analysis is often performed upon a single work—but it doesn’t have to be. It can also be performed across works to consider the interplay of two or more texts. Regardless of whether or not the works were written about the same thing, or even within the same time period, they can have an influence on one another or a connection that’s worth exploring. And reading two or more texts side by side can help you to develop insights through comparison and contrast.

For example, Paradise Lost is an epic poem written in the 17th century, based largely on biblical narratives written some 700 years before and which later influenced 19th century poet John Keats. The interplay of works can be obvious, as here, or entirely the inspiration of the analyst. As an example of the latter, you could compare and contrast the writing styles of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Allan Poe who, while contemporaries in terms of time, were vastly different in their content.

Additionally, literary analysis can be performed between a work and its context. Authors are often speaking to the larger context of their times, be that social, political, religious, economic, or artistic. A valid and interesting form is to compare the author’s context to the work, which is done by identifying and analyzing elements that are used to make an argument about the writer’s time or experience.

For example, you could write an essay about how Hemingway’s struggles with mental health and paranoia influenced his later work, or how his involvement in the Spanish Civil War influenced his early work. One approach focuses more on his personal experience, while the other turns to the context of his times—both are valid.

Why Does Literary Analysis Matter?

Sometimes an author wrote a work of literature strictly for entertainment’s sake, but more often than not, they meant something more. Whether that was a missive on world peace, commentary about femininity, or an allusion to their experience as an only child, the author probably wrote their work for a reason, and understanding that reason—or the many reasons—can actually make reading a lot more meaningful.

Performing literary analysis as a form of study unquestionably makes you a better reader. It’s also likely that it will improve other skills, too, like critical thinking, creativity, debate, and reasoning.

At its grandest and most idealistic, literary analysis even has the ability to make the world a better place. By reading and analyzing works of literature, you are able to more fully comprehend the perspectives of others. Cumulatively, you’ll broaden your own perspectives and contribute more effectively to the things that matter to you.

Literary Terms to Know for Literary Analysis

There are hundreds of literary devices you could consider during your literary analysis, but there are some key tools most writers utilize to achieve their purpose—and therefore you need to know in order to understand that purpose. These common devices include:

- Characters: The people (or entities) who play roles in the work. The protagonist is the main character in the work.

- Conflict: The conflict is the driving force behind the plot, the event that causes action in the narrative, usually on the part of the protagonist

- Context : The broader circumstances surrounding the work political and social climate in which it was written or the experience of the author. It can also refer to internal context, and the details presented by the narrator

- Diction : The word choice used by the narrator or characters

- Genre: A category of literature characterized by agreed upon similarities in the works, such as subject matter and tone

- Imagery : The descriptive or figurative language used to paint a picture in the reader’s mind so they can picture the story’s plot, characters, and setting

- Metaphor: A figure of speech that uses comparison between two unlike objects for dramatic or poetic effect

- Narrator: The person who tells the story. Sometimes they are a character within the story, but sometimes they are omniscient and removed from the plot.

- Plot : The storyline of the work

- Point of view: The perspective taken by the narrator, which skews the perspective of the reader

- Setting : The time and place in which the story takes place. This can include elements like the time period, weather, time of year or day, and social or economic conditions

- Symbol : An object, person, or place that represents an abstract idea that is greater than its literal meaning

- Syntax : The structure of a sentence, either narration or dialogue, and the tone it implies

- Theme : A recurring subject or message within the work, often commentary on larger societal or cultural ideas

- Tone : The feeling, attitude, or mood the text presents

How to Perform Literary Analysis

Step 1: read the text thoroughly.

Literary analysis begins with the literature itself, which means performing a close reading of the text. As you read, you should focus on the work. That means putting away distractions (sorry, smartphone) and dedicating a period of time to the task at hand.

It’s also important that you don’t skim or speed read. While those are helpful skills, they don’t apply to literary analysis—or at least not this stage.

Step 2: Take Notes as You Read

As you read the work, take notes about different literary elements and devices that stand out to you. Whether you highlight or underline in text, use sticky note tabs to mark pages and passages, or handwrite your thoughts in a notebook, you should capture your thoughts and the parts of the text to which they correspond. This—the act of noticing things about a literary work—is literary analysis.

Step 3: Notice Patterns

As you read the work, you’ll begin to notice patterns in the way the author deploys language, themes, and symbols to build their plot and characters. As you read and these patterns take shape, begin to consider what they could mean and how they might fit together.

As you identify these patterns, as well as other elements that catch your interest, be sure to record them in your notes or text. Some examples include:

- Circle or underline words or terms that you notice the author uses frequently, whether those are nouns (like “eyes” or “road”) or adjectives (like “yellow” or “lush”).

- Highlight phrases that give you the same kind of feeling. For example, if the narrator describes an “overcast sky,” a “dreary morning,” and a “dark, quiet room,” the words aren’t the same, but the feeling they impart and setting they develop are similar.

- Underline quotes or prose that define a character’s personality or their role in the text.

- Use sticky tabs to color code different elements of the text, such as specific settings or a shift in the point of view.

By noting these patterns, comprehensive symbols, metaphors, and ideas will begin to come into focus.

Step 4: Consider the Work as a Whole, and Ask Questions

This is a step that you can do either as you read, or after you finish the text. The point is to begin to identify the aspects of the work that most interest you, and you could therefore analyze in writing or discussion.

Questions you could ask yourself include:

- What aspects of the text do I not understand?

- What parts of the narrative or writing struck me most?

- What patterns did I notice?

- What did the author accomplish really well?

- What did I find lacking?

- Did I notice any contradictions or anything that felt out of place?

- What was the purpose of the minor characters?

- What tone did the author choose, and why?

The answers to these and more questions will lead you to your arguments about the text.

Step 5: Return to Your Notes and the Text for Evidence

As you identify the argument you want to make (especially if you’re preparing for an essay), return to your notes to see if you already have supporting evidence for your argument. That’s why it’s so important to take notes or mark passages as you read—you’ll thank yourself later!

If you’re preparing to write an essay, you’ll use these passages and ideas to bolster your argument—aka, your thesis. There will likely be multiple different passages you can use to strengthen multiple different aspects of your argument. Just be sure to cite the text correctly!

If you’re preparing for class, your notes will also be invaluable. When your teacher or professor leads the conversation in the direction of your ideas or arguments, you’ll be able to not only proffer that idea but back it up with textual evidence. That’s an A+ in class participation.

Step 6: Connect These Ideas Across the Narrative

Whether you’re in class or writing an essay, literary analysis isn’t complete until you’ve considered the way these ideas interact and contribute to the work as a whole. You can find and present evidence, but you still have to explain how those elements work together and make up your argument.

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay

When conducting literary analysis while reading a text or discussing it in class, you can pivot easily from one argument to another (or even switch sides if a classmate or teacher makes a compelling enough argument).

But when writing literary analysis, your objective is to propose a specific, arguable thesis and convincingly defend it. In order to do so, you need to fortify your argument with evidence from the text (and perhaps secondary sources) and an authoritative tone.

A successful literary analysis essay depends equally on a thoughtful thesis, supportive analysis, and presenting these elements masterfully. We’ll review how to accomplish these objectives below.

Step 1: Read the Text. Maybe Read It Again.

Constructing an astute analytical essay requires a thorough knowledge of the text. As you read, be sure to note any passages, quotes, or ideas that stand out. These could serve as the future foundation of your thesis statement. Noting these sections now will help you when you need to gather evidence.

The more familiar you become with the text, the better (and easier!) your essay will be. Familiarity with the text allows you to speak (or in this case, write) to it confidently. If you only skim the book, your lack of rich understanding will be evident in your essay. Alternatively, if you read the text closely—especially if you read it more than once, or at least carefully revisit important passages—your own writing will be filled with insight that goes beyond a basic understanding of the storyline.

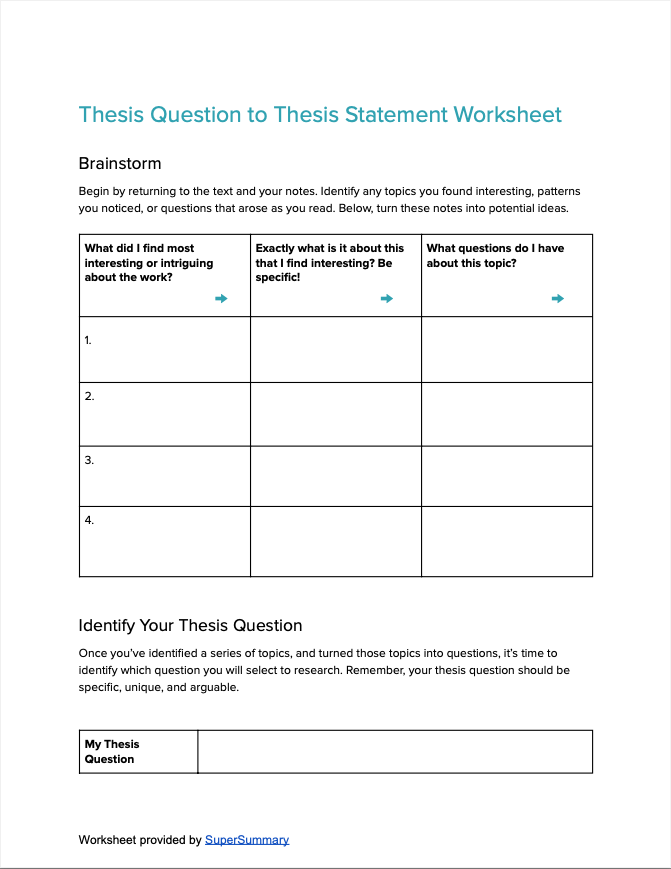

Step 2: Brainstorm Potential Topics

Because you took detailed notes while reading the text, you should have a list of potential topics at the ready. Take time to review your notes, highlighting any ideas or questions you had that feel interesting. You should also return to the text and look for any passages that stand out to you.

When considering potential topics, you should prioritize ideas that you find interesting. It won’t only make the whole process of writing an essay more fun, your enthusiasm for the topic will probably improve the quality of your argument, and maybe even your writing. Just like it’s obvious when a topic interests you in a conversation, it’s obvious when a topic interests the writer of an essay (and even more obvious when it doesn’t).

Your topic ideas should also be specific, unique, and arguable. A good way to think of topics is that they’re the answer to fairly specific questions. As you begin to brainstorm, first think of questions you have about the text. Questions might focus on the plot, such as: Why did the author choose to deviate from the projected storyline? Or why did a character’s role in the narrative shift? Questions might also consider the use of a literary device, such as: Why does the narrator frequently repeat a phrase or comment on a symbol? Or why did the author choose to switch points of view each chapter?

Once you have a thesis question , you can begin brainstorming answers—aka, potential thesis statements . At this point, your answers can be fairly broad. Once you land on a question-statement combination that feels right, you’ll then look for evidence in the text that supports your answer (and helps you define and narrow your thesis statement).

For example, after reading “ The Fall of the House of Usher ,” you might be wondering, Why are Roderick and Madeline twins?, Or even: Why does their relationship feel so creepy?” Maybe you noticed (and noted) that the narrator was surprised to find out they were twins, or perhaps you found that the narrator’s tone tended to shift and become more anxious when discussing the interactions of the twins.

Once you come up with your thesis question, you can identify a broad answer, which will become the basis for your thesis statement. In response to the questions above, your answer might be, “Poe emphasizes the close relationship of Roderick and Madeline to foreshadow that their deaths will be close, too.”

Step 3: Gather Evidence

Once you have your topic (or you’ve narrowed it down to two or three), return to the text (yes, again) to see what evidence you can find to support it. If you’re thinking of writing about the relationship between Roderick and Madeline in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” look for instances where they engaged in the text.

This is when your knowledge of literary devices comes in clutch. Carefully study the language around each event in the text that might be relevant to your topic. How does Poe’s diction or syntax change during the interactions of the siblings? How does the setting reflect or contribute to their relationship? What imagery or symbols appear when Roderick and Madeline are together?

By finding and studying evidence within the text, you’ll strengthen your topic argument—or, just as valuably, discount the topics that aren’t strong enough for analysis.

Step 4: Consider Secondary Sources

In addition to returning to the literary work you’re studying for evidence, you can also consider secondary sources that reference or speak to the work. These can be articles from journals you find on JSTOR, books that consider the work or its context, or articles your teacher shared in class.

While you can use these secondary sources to further support your idea, you should not overuse them. Make sure your topic remains entirely differentiated from that presented in the source.

Step 5: Write a Working Thesis Statement

Once you’ve gathered evidence and narrowed down your topic, you’re ready to refine that topic into a thesis statement. As you continue to outline and write your paper, this thesis statement will likely change slightly, but this initial draft will serve as the foundation of your essay. It’s like your north star: Everything you write in your essay is leading you back to your thesis.

Writing a great thesis statement requires some real finesse. A successful thesis statement is:

- Debatable : You shouldn’t simply summarize or make an obvious statement about the work. Instead, your thesis statement should take a stand on an issue or make a claim that is open to argument. You’ll spend your essay debating—and proving—your argument.

- Demonstrable : You need to be able to prove, through evidence, that your thesis statement is true. That means you have to have passages from the text and correlative analysis ready to convince the reader that you’re right.

- Specific : In most cases, successfully addressing a theme that encompasses a work in its entirety would require a book-length essay. Instead, identify a thesis statement that addresses specific elements of the work, such as a relationship between characters, a repeating symbol, a key setting, or even something really specific like the speaking style of a character.

Example: By depicting the relationship between Roderick and Madeline to be stifling and almost otherworldly in its closeness, Poe foreshadows both Madeline’s fate and Roderick’s inability to choose a different fate for himself.

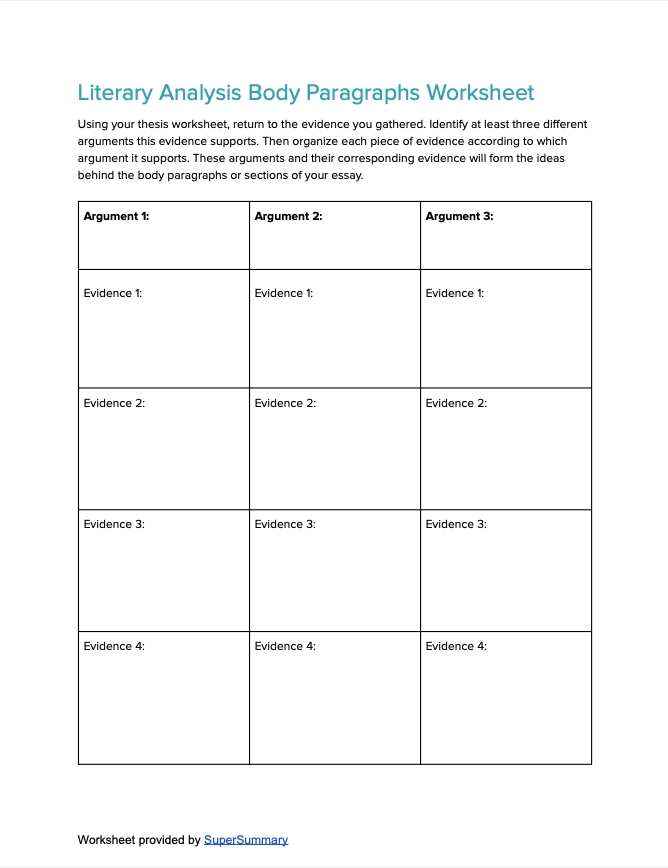

Step 6: Write an Outline

You have your thesis, you have your evidence—but how do you put them together? A great thesis statement (and therefore a great essay) will have multiple arguments supporting it, presenting different kinds of evidence that all contribute to the singular, main idea presented in your thesis.

Review your evidence and identify these different arguments, then organize the evidence into categories based on the argument they support. These ideas and evidence will become the body paragraphs of your essay.

For example, if you were writing about Roderick and Madeline as in the example above, you would pull evidence from the text, such as the narrator’s realization of their relationship as twins; examples where the narrator’s tone of voice shifts when discussing their relationship; imagery, like the sounds Roderick hears as Madeline tries to escape; and Poe’s tendency to use doubles and twins in his other writings to create the same spooky effect. All of these are separate strains of the same argument, and can be clearly organized into sections of an outline.

Step 7: Write Your Introduction

Your introduction serves a few very important purposes that essentially set the scene for the reader:

- Establish context. Sure, your reader has probably read the work. But you still want to remind them of the scene, characters, or elements you’ll be discussing.

- Present your thesis statement. Your thesis statement is the backbone of your analytical paper. You need to present it clearly at the outset so that the reader understands what every argument you make is aimed at.

- Offer a mini-outline. While you don’t want to show all your cards just yet, you do want to preview some of the evidence you’ll be using to support your thesis so that the reader has a roadmap of where they’re going.

Step 8: Write Your Body Paragraphs

Thanks to steps one through seven, you’ve already set yourself up for success. You have clearly outlined arguments and evidence to support them. Now it’s time to translate those into authoritative and confident prose.

When presenting each idea, begin with a topic sentence that encapsulates the argument you’re about to make (sort of like a mini-thesis statement). Then present your evidence and explanations of that evidence that contribute to that argument. Present enough material to prove your point, but don’t feel like you necessarily have to point out every single instance in the text where this element takes place. For example, if you’re highlighting a symbol that repeats throughout the narrative, choose two or three passages where it is used most effectively, rather than trying to squeeze in all ten times it appears.

While you should have clearly defined arguments, the essay should still move logically and fluidly from one argument to the next. Try to avoid choppy paragraphs that feel disjointed; every idea and argument should feel connected to the last, and, as a group, connected to your thesis. A great way to connect the ideas from one paragraph to the next is with transition words and phrases, such as:

- Furthermore

- In addition

- On the other hand

- Conversely

Step 9: Write Your Conclusion

Your conclusion is more than a summary of your essay's parts, but it’s also not a place to present brand new ideas not already discussed in your essay. Instead, your conclusion should return to your thesis (without repeating it verbatim) and point to why this all matters. If writing about the siblings in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” for example, you could point out that the utilization of twins and doubles is a common literary element of Poe’s work that contributes to the definitive eeriness of Gothic literature.

While you might speak to larger ideas in your conclusion, be wary of getting too macro. Your conclusion should still be supported by all of the ideas that preceded it.

Step 10: Revise, Revise, Revise

Of course you should proofread your literary analysis essay before you turn it in. But you should also edit the content to make sure every piece of evidence and every explanation directly supports your thesis as effectively and efficiently as possible.

Sometimes, this might mean actually adapting your thesis a bit to the rest of your essay. At other times, it means removing redundant examples or paraphrasing quotations. Make sure every sentence is valuable, and remove those that aren’t.

Other Resources for Literary Analysis

With these skills and suggestions, you’re well on your way to practicing and writing literary analysis. But if you don’t have a firm grasp on the concepts discussed above—such as literary devices or even the content of the text you’re analyzing—it will still feel difficult to produce insightful analysis.

If you’d like to sharpen the tools in your literature toolbox, there are plenty of other resources to help you do so:

- Check out our expansive library of Literary Devices . These could provide you with a deeper understanding of the basic devices discussed above or introduce you to new concepts sure to impress your professors ( anagnorisis , anyone?).

- This Academic Citation Resource Guide ensures you properly cite any work you reference in your analytical essay.

- Our English Homework Help Guide will point you to dozens of resources that can help you perform analysis, from critical reading strategies to poetry helpers.

- This Grammar Education Resource Guide will direct you to plenty of resources to refine your grammar and writing (definitely important for getting an A+ on that paper).

Of course, you should know the text inside and out before you begin writing your analysis. In order to develop a true understanding of the work, read through its corresponding SuperSummary study guide . Doing so will help you truly comprehend the plot, as well as provide some inspirational ideas for your analysis.

- Our Writers

- How to Order

- Assignment Writing Service

- Report Writing Service

- Buy Coursework

- Dissertation Writing Service

- Research Paper Writing Service

- All Essay Services

- Buy Research Paper

- Buy Term Paper

- Buy Dissertation

- Buy Case study

- Buy Presentation

- Buy Personal statement

Critical Essay Writing

Critical Essay - A Step by Step Guide & Examples

11 min read

People also read

A Comprehensive List of 260+ Inspiring Critical Essay Topics

Critical Essay Outline - Writing Guide With Examples

Many students find it tough to write a good critical essay because it's different from other essays. Understanding the deeper meanings in literature and creating a strong essay can be tricky.

This confusion makes it hard for students to analyze and explain literary works effectively. They struggle to create essays that show a strong understanding of the topic.

But don't worry! This guide will help. It gives step-by-step instructions, examples, and tips to make writing a great critical essay easier. By learning the key parts and looking at examples, students can master the skill of writing these essays.

- 1. Critical Essay Definition

- 2. Techniques in Literary Critical Essays

- 3. How to Write a Critical Essay?

- 4. Critical Essay Examples

- 5. Critical Essay Topics

- 6. Tips For Writing a Critical Essay

Critical Essay Definition

A critical is a form of analytical essay that analyzes, evaluates, and interprets a piece of literature, movie, book, play, etc.

The writer signifies the meaning of the text by claiming the themes. The claims are then supported by facts using primary and secondary sources of information.

What Makes An Essay Critical?

People often confuse this type of essay with an argumentative essay. It is because they both deal with claims and provide evidence on the subject matter.

An argumentative essay uses evidence to persuade the reader. On the other hand, a critical analysis essay discusses the themes, analyzes, and interprets them for its audience.

Here are the key characteristics of a critical essay:

- Looking Beyond the Surface: In a critical essay, it's not just about summarizing. It goes deeper, looking into the hidden meanings and themes of the text.

- Sharing Opinions with Evidence: It's not only about what you think. You need to back up your ideas with proof from the text or other sources.

- Examining from Different Angles: A critical essay doesn't just focus on one side. It looks at different viewpoints and examines things from various perspectives.

- Finding Strengths and Weaknesses: It's about discussing what's good and what's not so good in the text or artwork. This helps in forming a balanced opinion.

- Staying Objective: Instead of being emotional, it stays fair and objective, using facts and examples to support arguments.

- Creating a Strong Argument: A critical essay builds a strong argument by analyzing the content and forming a clear opinion that's well-supported.

- Analyzing the 'Why' and 'How': It's not just about what happens in the text but why it happens and how it influences the overall meaning.

Techniques in Literary Critical Essays

Analyzing literature involves a set of techniques that form the backbone of literary criticism. Let's delve into these techniques, providing a comprehensive understanding before exploring illustrative examples:

Formalism in literary criticism directs attention to the inherent structure, style, and linguistic elements within a text. It is concerned with the way a work is crafted, examining how literary devices contribute to its overall impact.

Example: In Emily Brontë's "Wuthering Heights," a formalist analysis might emphasize the novel's intricate narrative structure and the use of Gothic elements.

Psychoanalytic Criticism

Psychoanalytic Criticism delves into the psychological motivations and subconscious elements of characters and authors. It often draws on psychoanalytic theories, such as those developed by Sigmund Freud, to explore the deeper layers of the human psyche reflected in literature.

Example: In "Orlando," Virginia Woolf employs psychoanalytic elements to symbolically explore identity and gender fluidity. The protagonist's centuries-spanning transformation reflects Woolf's subconscious struggles, using fantasy as a lens to navigate psychological complexities.

Feminist Criticism

Feminist Criticism evaluates how gender roles, stereotypes, and power dynamics are portrayed in literature. It seeks to uncover and challenge representations that may perpetuate gender inequalities or reinforce stereotypes.

Example: Applying feminist criticism to Charlotte Perkins Gilman's "The Yellow Wallpaper" involves scrutinizing the representation of women's mental health and societal expectations.

Marxist Criticism

Marxist Criticism focuses on economic and social aspects, exploring how literature reflects and critiques class structures. It examines how power dynamics, societal hierarchies, and economic systems are portrayed in literary works.

Example: Analyzing George Orwell's "Animal Farm" through a Marxist lens involves examining its allegorical representation of societal class struggles.

Cultural Criticism

Cultural Criticism considers the cultural context and societal influences shaping the creation and reception of literature. It examines how cultural norms, values, and historical contexts impact the meaning and interpretation of a work.

Example: Cultural criticism of Chinua Achebe's "Things Fall Apart" may delve into the impact of colonialism on African identity.

Postcolonial Criticism

Postcolonial Criticism examines the representation of colonial and postcolonial experiences in literature. It explores how authors engage with and respond to the legacy of colonialism, addressing issues of identity, cultural hybridity, and power.

Example: A postcolonial analysis of Salman Rushdie's "Midnight's Children" may explore themes of identity and cultural hybridity.

Understanding these techniques provides a comprehensive toolkit for navigating the diverse landscape of literary criticism.

How to Write a Critical Essay?

Crafting a critical essay involves a step-by-step process that every student can follow to create a compelling piece of analysis.

Step 1: Explore the Subject in Depth

Start by diving into the primary subject of the work. When critically reading the original text, focus on identifying key elements:

- Main themes: Discover the central ideas explored in the work.

- Different features: Examine the distinctive components and specific details in the story.

- Style: Observe the techniques and writing style used to persuade the audience.

- Strengths and weaknesses: Evaluate notable aspects and potential shortcomings.

Step 2: Conduct Research

To support your insights, conduct thorough research using credible sources.

Take detailed notes as you read, highlighting key points and interesting quotes. Also make sure you’re paying attention to the specific points that directly support and strengthen your analysis of the work.

Step 3: Create an Outline

After you have gathered the sources and information, organize what you have in an outline. This will serve as a roadmap for your writing process, ensuring a structured essay.

Here is a standard critical essay outline:

Make sure to structure and organize your critical essay with this in-depth guide on creating a critical essay outline !

Step 4: Develop Your Thesis Statement

Create a strong thesis statement encapsulating your stance on the subject. This statement will guide the content in the body sections.

A good thesis keeps your essay clear and organized, making sure all your points fit together. To make a strong thesis, first, be clear about what main idea you want to talk about. Avoid being vague and clearly state your key arguments and analysis.

Here's what a typical thesis statement for a critical essay looks like:

"In [Title/Author/Work], [Your Main Claim] because [Brief Overview of Reasons/Key Points] . Through a focused analysis of [Specific Aspects or Elements] , this essay aims to [Purpose of the Critical Examination] ."

Step 5: Decide on Supporting Material

While reading the text, select compelling pieces of evidence that strongly support your thesis statement. Ask yourself:

- Which information is recognized by authorities in the subject?

- Which information is supported by other authors?

- Which information best defines and supports the thesis statement?

Step 6: Include an Opposing Argument

Present an opposing argument that challenges your thesis statement. This step requires you critically read your own analysis and find counterarguments so you can refute them.

This not only makes your discussion richer but also makes your own argument stronger by addressing different opinions.

Step 7: Critical Essay Introduction

Begin your critical essay with an introduction that clearly suggests the reader what they should expect from the rest of the essay. Here are the essential elements of an introduction paragraph:

- Hook: Start with a compelling opening line that captivates your reader's interest.

- Background Information: Provide essential context to ensure your readers grasp the subject matter. Add brief context of the story that contributes to a better understanding.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude with a clear thesis statement, summarizing the core argument of your critical essay. This serves as a roadmap, guiding the reader through the main focus of your analysis.

Step 8: Critical Essay Body Paragraphs

The body presents arguments and supporting evidence. Each paragraph starts with a topic sentence, addressing a specific idea. Use transitional words to guide the reader seamlessly through your analysis.

Here’s the standard format for a critical essay body paragraph:

- Topic Sentence: Introduces the central idea of the paragraph, acting as a roadmap for the reader.

- Analysis: Objectively examines data, facts, theories, and approaches used in the work.

- Evaluation: Assesses the work based on earlier claims and evidence, establishing logical consistency.

- Relate Back to Topic Sentence: Reinforces how the analyzed details connect to the main idea introduced at the beginning of the paragraph.

- Transition: Creates a seamless transition from one body paragraph to the next.

Step 9: Critical Essay Conclusion

Summarize your key points in the conclusion. Reiterate the validity of your thesis statement, the main point of your essay.

Finally, offer an objective analysis in your conclusion. Look at the broader picture and discuss the larger implications or significance of your critique. Consider how your analysis fits into the larger context and what it contributes to the understanding of the subject.

Step 10: Proofread and Edit

Allocate time for meticulous revision. Scrutinize your essay for errors. Rectify all mistakes to ensure a polished academic piece.

Following these steps will empower you to dissect a work critically and present your insights persuasively.

Critical Essay Examples

Writing a critical essay about any theme requires you take on different approaches. Here are some examples of critical essays about literary works and movies exploring different themes:

Critical Essay About A Movie

Equality By Maya Angelou Critical Essay

Higher English Critical Essay

Analysis Critical Essay Example

Critical Essay on Joseph Conrad's Heart Of Darkness

Critical Essay On Tess Of The d'Urbervilles

Critical Essay Topics

A strong critical essay topic is both interesting and relevant, encouraging in-depth analysis and unique perspectives.

A good critical essay topic tackles current issues, questions established ideas, and has enough existing literature for thorough research. Here are some critical analysis topic:

- The Representation of Diversity in Modern Literature

- Impact of Social Media on Character Relationships in Novels

- Challenging Stereotypes: Gender Portrayal in Contemporary Fiction

- Exploring Economic Disparities in Urban Novels

- Postcolonial Themes in Global Literature

- Mental Health Narratives: Realism vs. Romanticism

- Ecocriticism: Nature's Role in Classic Literature

- Unveiling Power Struggles in Family Dynamics in Literary Works

- Satire and Political Commentary in Modern Fiction

- Quest for Identity: Coming-of-Age Novels in the 21st Century

Need more topic ideas? Check out these interesting and unique critical essay topics and get inspired!

Tips For Writing a Critical Essay

Become a skilled critical essay writer by following these practical tips:

- Dig deep into your topic. Understand themes, characters, and literary elements thoroughly.

- Think about different opinions to make your argument stronger and show you understand the whole picture.

- Get information from reliable places like books, academic journals, and experts to make your essay more trustworthy.

- Make a straightforward and strong statement that sums up your main point.

- Support your ideas with solid proof from the text or other sources. Use quotes, examples, and references wisely.

- Keep a neutral and academic tone. Avoid sharing too many personal opinions and focus on analyzing the facts.

- Arrange your essay logically with a clear beginning, middle, and end. Make sure your ideas flow well.

- Go beyond just summarizing. Think deeply about the strengths, weaknesses, and overall impact of the work.

- Read through your essay multiple times to fix mistakes and make sure it's clear. A well-edited essay shows you care about the details.

You can use these tips to make your critical essays more insightful and well-written. Now that you have this helpful guide, you can start working on your critical essay.

If it seems too much, no worries. Our essay writing website is here to help.

Our experienced writers can handle critical essays on any topic, making it easier for you. Just reach out, and we've got your back throughout your essay journey.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many paragraphs is a critical essay.

Keep in mind that every sentence should communicate the point. Every paragraph must support your thesis statement either by offering a claim or presenting an argument, and these are followed up with evidence for success! Most critical essays will have three to six paragraphs unless otherwise specified on examinations so make sure you follow them closely if applicable.

Can critical essays be in the first person?

The critical essay is an informative and persuasive work that stresses the importance of your argument. You need to support any claims or observations with evidence, so in order for it to be most effective, you should avoid using first-person pronouns like I/me when writing this type of paper.

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Cathy has been been working as an author on our platform for over five years now. She has a Masters degree in mass communication and is well-versed in the art of writing. Cathy is a professional who takes her work seriously and is widely appreciated by clients for her excellent writing skills.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

How to write a critical essay

Part of English Critical essay writing

- It is important to plan your critical essay before you start writing.

- An essay has a clear structure with an introduction, paragraphs with evidence and a conclusion.

- Evidence , in the form of quotations and examples is the foundation of an effective essay and provides proof for your points.

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Learn how to plan, structure and use evidence in your essays

It is important to plan before you start writing an essay.

The essay question or title should provide a clear focus for your plan. Exploring this will help you make decisions about what points are relevant to the essay. What are you being asked to consider?

Organise your thoughts. Researching, mind mapping and making notes will help sort and prioritise your ideas. If you are writing a critical essay, planning will help you decide which parts of the text to focus on and what points to make.

How to use the passive voice to sound more objective

- count 3 of 3

Critical Analysis in Composition

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In composition , critical analysis is a careful examination and evaluation of a text , image, or other work or performance.

Performing a critical analysis does not necessarily involve finding fault with a work. On the contrary, a thoughtful critical analysis may help us understand the interaction of the particular elements that contribute to a work's power and effectiveness. For this reason, critical analysis is a central component of academic training; the skill of critical analysis is most often thought of in the context of analyzing a work of art or literature, but the same techniques are useful to build an understanding of texts and resources in any discipline.

In this context, the word "critical" carries a different connotation than in vernacular, everyday speech. "Critical" here does not simply mean pointing out a work's flaws or arguing why it is objectionable by some standard. Instead, it points towards a close reading of that work to gather meaning, as well as to evaluate its merits. The evaluation is not the sole point of critical analysis, which is where it differs from the colloquial meaning of "criticize."

Examples of Critical Essays

- "Jack and Gill: A Mock Criticism" by Joseph Dennie

- "Miss Brill's Fragile Fantasy": A Critical Essay About Katherine Mansfield's Short Story "Miss Brill" and "Poor, Pitiful Miss Brill"

- "On the Knocking at the Gate in Macbeth " by Thomas De Quincey

- A Rhetorical Analysis of Claude McKay's "Africa"

- A Rhetorical Analysis of E B. White's Essay "The Ring of Time"

- A Rhetorical Analysis of U2's "Sunday Bloody Sunday"

- "Saloonio: A Study in Shakespearean Criticism" by Stephen Leacock

- Writing About Fiction: A Critical Essay on Hemingway's Novel The Sun Also Rises

Quotes About Critical Analysis

- " [C]ritical analysis involves breaking down an idea or a statement, such as a claim , and subjecting it to critical thinking in order to test its validity." (Eric Henderson, The Active Reader: Strategies for Academic Reading and Writing . Oxford University Press, 2007)

- "To write an effective critical analysis, you need to understand the difference between analysis and summary . . . . [A] critical analysis looks beyond the surface of a text—it does far more than summarize a work. A critical analysis isn't simply dashing off a few words about the work in general." ( Why Write?: A Guide to BYU Honors Intensive Writing . Brigham Young University, 2006)

- "Although the main purpose of a critical analysis is not to persuade , you do have the responsibility of organizing a discussion that convinces readers that your analysis is astute." (Robert Frew et al., Survival: A Sequential Program for College Writing . Peek, 1985)

Critical Thinking and Research

"[I]n response to the challenge that a lack of time precludes good, critical analysis , we say that good, critical analysis saves time. How? By helping you be more efficient in terms of the information you gather. Starting from the premise that no practitioner can claim to collect all the available information, there must always be a degree of selection that takes place. By thinking analytically from the outset, you will be in a better position to 'know' which information to collect, which information is likely to be more or less significant and to be clearer about what questions you are seeking to answer." (David Wilkins and Godfred Boahen, Critical Analysis Skills For Social Workers . McGraw-Hill, 2013)

How to Read Text Critically

"Being critical in academic enquiry means: - adopting an attitude of skepticism or reasoned doubt towards your own and others' knowledge in the field of enquiry . . . - habitually questioning the quality of your own and others' specific claims to knowledge about the field and the means by which these claims were generated; - scrutinizing claims to see how far they are convincing . . .; - respecting others as people at all times. Challenging others' work is acceptable, but challenging their worth as people is not; - being open-minded , willing to be convinced if scrutiny removes your doubts, or to remain unconvinced if it does not; - being constructive by putting your attitude of skepticism and your open-mindedness to work in attempting to achieve a worthwhile goal." (Mike Wallace and Louise Poulson, "Becoming a Critical Consumer of the Literature." Learning to Read Critically in Teaching and Learning , ed. by Louise Poulson and Mike Wallace. SAGE, 2004)

Critically Analyzing Persuasive Ads

"[I]n my first-year composition class, I teach a four-week advertisement analysis project as a way to not only heighten students' awareness of the advertisements they encounter and create on a daily basis but also to encourage students to actively engage in a discussion about critical analysis by examining rhetorical appeals in persuasive contexts. In other words, I ask students to pay closer attention to a part of the pop culture in which they live. " . . . Taken as a whole, my ad analysis project calls for several writing opportunities in which students write essays , responses, reflections, and peer assessments . In the four weeks, we spend a great deal of time discussing the images and texts that make up advertisements, and through writing about them, students are able to heighten their awareness of the cultural 'norms' and stereotypes which are represented and reproduced in this type of communication ." (Allison Smith, Trixie Smith, and Rebecca Bobbitt, Teaching in the Pop Culture Zone: Using Popular Culture in the Composition Classroom . Wadsworth Cengage, 2009)

Critically Analyzing Video Games

"When dealing with a game's significance, one could analyze the themes of the game be they social, cultural, or even political messages. Most current reviews seem to focus on a game's success: why it is successful, how successful it will be, etc. Although this is an important aspect of what defines the game, it is not critical analysis . Furthermore, the reviewer should dedicate some to time to speaking about what the game has to contribute to its genre (Is it doing something new? Does it present the player with unusual choices? Can it set a new standard for what games of this type should include?)." (Mark Mullen, "On Second Thought . . ." Rhetoric/Composition/Play Through Video Games: Reshaping Theory and Practice , ed. by Richard Colby, Matthew S.S. Johnson, and Rebekah Shultz Colby. Palgrave Macmillan, 2013)

Critical Thinking and Visuals

"The current critical turn in rhetoric and composition studies underscores the role of the visual, especially the image artifact, in agency. For instance, in Just Advocacy? a collection of essays focusing on the representation of women and children in international advocacy efforts, coeditors Wendy S. Hesford and Wendy Kozol open their introduction with a critical analysis of a documentary based on a picture: the photograph of an unknown Afghan girl taken by Steve McCurry and gracing the cover of National Geographic in 1985. Through an examination of the ideology of the photo's appeal as well as the 'politics of pity' circulating through the documentary, Hesford and Kozol emphasize the power of individual images to shape perceptions, beliefs, actions, and agency." (Kristie S. Fleckenstein, Vision, Rhetoric, and Social Action in the Composition Classroom . Southern Illinois University Press, 2010)

Related Concepts

- Analysis and Critical Essay

- Book Report

- Close Reading

- Critical Thinking

- Discourse Analysis

- Evaluation Essay

- Explication

- Problem-Solution

- Rhetorical Analysis

- Definition and Examples of Explication (Analysis)

- Rhetorical Analysis Definition and Examples

- Quotes About Close Reading

- How to Write a Critical Essay

- What Is a Critique in Composition?

- Definition and Examples of Evaluation Essays

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- Understanding the Use of Language Through Discourse Analysis

- Critical Thinking in Reading and Composition

- What Is a Written Summary?

- Critical Thinking Definition, Skills, and Examples

- Miss Brill's Fragile Fantasy

- 6 Skills Students Need to Succeed in Social Studies Classes

- Stylistics and Elements of Style in Literature

- Informal Logic

- Rhetorical Move

Authors & Literary Criticism: What is Literary Criticism?

What is literary criticism.

- Literature Databases, Websites, & Academic Journals

- Related Library Books

Literary Criticism is the process of:

A nalyzing,

E valuating,

D escribing, or

I nterpreting literature.

Literary criticism can be based on:

one author's entire body of work, or

the works of different authors.

Critical Analysis Defined

CRITICAL ANALYSIS

by Elisabetta LeJeune

A Monroe College Research Guide

THIS RESEARCH OR "LIBGUIDE" WAS PRODUCED BY THE LIBRARIANS OF MONROE COLLEGE

- Next: Literature Databases, Websites, & Academic Journals >>

- Last Updated: Mar 13, 2024 10:12 AM

- URL: https://monroecollege.libguides.com/literarycriticism

- Research Guides |

- Databases |

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 What Is Literature and Why Do We Study It?

In this book created for my English 211 Literary Analysis introductory course for English literature and creative writing majors at the College of Western Idaho, I’ll introduce several different critical approaches that literary scholars may use to answer these questions. The critical method we apply to a text can provide us with different perspectives as we learn to interpret a text and appreciate its meaning and beauty.

The existence of literature, however we define it, implies that we study literature. While people have been “studying” literature as long as literature has existed, the formal study of literature as we know it in college English literature courses began in the 1940s with the advent of New Criticism. The New Critics were formalists with a vested interest in defining literature–they were, after all, both creating and teaching about literary works. For them, literary criticism was, in fact, as John Crowe Ransom wrote in his 1942 essay “ Criticism, Inc., ” nothing less than “the business of literature.”

Responding to the concern that the study of literature at the university level was often more concerned with the history and life of the author than with the text itself, Ransom responded, “the students of the future must be permitted to study literature, and not merely about literature. But I think this is what the good students have always wanted to do. The wonder is that they have allowed themselves so long to be denied.”

We’ll learn more about New Criticism in Section Three. For now, let’s return to the two questions I posed earlier.

What is literature?

First, what is literature ? I know your high school teacher told you never to look up things on Wikipedia, but for the purposes of literary studies, Wikipedia can actually be an effective resource. You’ll notice that I link to Wikipedia articles occasionally in this book. Here’s how Wikipedia defines literature :

“ Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction , drama , and poetry . [1] In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include oral literature , much of which has been transcribed. [2] Literature is a method of recording, preserving, and transmitting knowledge and entertainment, and can also have a social, psychological, spiritual, or political role.”

This definition is well-suited for our purposes here because throughout this course, we will be considering several types of literary texts in a variety of contexts.

I’m a Classicist—a student of Greece and Rome and everything they touched—so I am always interested in words with Latin roots. The Latin root of our modern word literature is litera , or “letter.” Literature, then, is inextricably intertwined with the act of writing. But what kind of writing?

Who decides which texts are “literature”?

The second question is at least as important as the first one. If we agree that literature is somehow special and different from ordinary writing, then who decides which writings count as literature? Are English professors the only people who get to decide? What qualifications and training does someone need to determine whether or not a text is literature? What role do you as the reader play in this decision about a text?

Let’s consider a few examples of things that we would all probably classify as literature. I think we can all (probably) agree that the works of William Shakespeare are literature. We can look at Toni Morrison’s outstanding ouvre of work and conclude, along with the Nobel Prize Committee, that books such as Beloved and Song of Solomon are literature. And if you’re taking a creative writing course and have been assigned the short stories of Raymond Carver or the poems of Joy Harjo , you’re probably convinced that these texts are literature too.

In each of these three cases, a different “deciding” mechanism is at play. First, with Shakespeare, there’s history and tradition. These plays that were written 500 years ago are still performed around the world and taught in high school and college English classes today. It seems we have consensus about the tragedies, histories, comedies, and sonnets of the Bard of Avon (or whoever wrote the plays).

In the second case, if you haven’t heard of Toni Morrison (and I am very sorry if you haven’t), you probably have heard of the Nobel Prize. This is one of the most prestigious awards given in literature, and since she’s a winner, we can safely assume that Toni Morrison’s works are literature.

Finally, your creative writing professor is an expert in their field. You know they have an MFA (and worked hard for it), so when they share their favorite short stories or poems with you, you trust that they are sharing works considered to be literature, even if you haven’t heard of Raymond Carver or Joy Harjo before taking their class.

(Aside: What about fanfiction? Is fanfiction literature?)

We may have to save the debate about fan fiction for another day, though I introduced it because there’s some fascinating and even literary award-winning fan fiction out there.

Returning to our question, what role do we as readers play in deciding whether something is literature? Like John Crowe Ransom quoted above, I think that the definition of literature should depend on more than the opinions of literary critics and literature professors.

I also want to note that contrary to some opinions, plenty of so-called genre fiction can also be classified as literature. The Nobel Prize winning author Kazuo Ishiguro has written both science fiction and historical fiction. Iain Banks , the British author of the critically acclaimed novel The Wasp Factory , published popular science fiction novels under the name Iain M. Banks. In other words, genre alone can’t tell us whether something is literature or not.

In this book, I want to give you the tools to decide for yourself. We’ll do this by exploring several different critical approaches that we can take to determine how a text functions and whether it is literature. These lenses can reveal different truths about the text, about our culture, and about ourselves as readers and scholars.

“Turf Wars”: Literary criticism vs. authors

It’s important to keep in mind that literature and literary theory have existed in conversation with each other since Aristotle used Sophocles’s play Oedipus Rex to define tragedy. We’ll look at how critical theory and literature complement and disagree with each other throughout this book. For most of literary history, the conversation was largely a friendly one.

But in the twenty-first century, there’s a rising tension between literature and criticism. In his 2016 book Literature Against Criticism: University English and Contemporary Fiction in Conflict, literary scholar Martin Paul Eve argues that twenty-first century authors have developed

a series of novelistic techniques that, whether deliberate or not on the part of the author, function to outmanoeuvre, contain, and determine academic reading practices. This desire to discipline university English through the manipulation and restriction of possible hermeneutic paths is, I contend, a result firstly of the fact that the metafictional paradigm of the high-postmodern era has pitched critical and creative discourses into a type of productive competition with one another. Such tensions and overlaps (or ‘turf wars’) have only increased in light of the ongoing breakdown of coherent theoretical definitions of ‘literature’ as distinct from ‘criticism’ (15).

One of Eve’s points is that by narrowly and rigidly defining the boundaries of literature, university English professors have inadvertently created a situation where the market increasingly defines what “literature” is, despite the protestations of the academy. In other words, the gatekeeper role that literary criticism once played is no longer as important to authors. For example, (almost) no one would call 50 Shades of Grey literature—but the salacious E.L James novel was the bestselling book of the decade from 2010-2019, with more than 35 million copies sold worldwide.

If anyone with a blog can get a six-figure publishing deal , does it still matter that students know how to recognize and analyze literature? I think so, for a few reasons.

- First, the practice of reading critically helps you to become a better reader and writer, which will help you to succeed not only in college English courses but throughout your academic and professional career.

- Second, analysis is a highly sought after and transferable skill. By learning to analyze literature, you’ll practice the same skills you would use to analyze anything important. “Data analyst” is one of the most sought after job positions in the New Economy—and if you can analyze Shakespeare, you can analyze data. Indeed.com’s list of top 10 transferable skills includes analytical skills , which they define as “the traits and abilities that allow you to observe, research and interpret a subject in order to develop complex ideas and solutions.”

- Finally, and for me personally, most importantly, reading and understanding literature makes life make sense. As we read literature, we expand our sense of what is possible for ourselves and for humanity. In the challenges we collectively face today, understanding the world and our place in it will be important for imagining new futures.

A note about using generative artificial intelligence

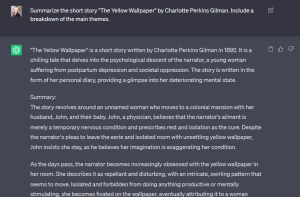

As I was working on creating this textbook, ChatGPT exploded into academic consciousness. Excited about the possibilities of this new tool, I immediately began incorporating it into my classroom teaching. In this book, I have used ChatGPT to help me with outlining content in chapters. I also used ChatGPT to create sample essays for each critical lens we will study in the course. These essays are dry and rather soulless, but they do a good job of modeling how to apply a specific theory to a literary text. I chose John Donne’s poem “The Canonization” as the text for these essays so that you can see how the different theories illuminate different aspects of the text.

I encourage students in my courses to use ChatGPT in the following ways:

- To generate ideas about an approach to a text.

- To better understand basic concepts.

- To assist with outlining an essay.

- To check grammar, punctuation, spelling, paragraphing, and other grammar/syntax issues.

If you choose to use Chat GPT, please include a brief acknowledgment statement as an appendix to your paper after your Works Cited page explaining how you have used the tool in your work. Here is an example of how to do this from Monash University’s “ Acknowledging the Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence .”

I acknowledge the use of [insert AI system(s) and link] to [specific use of generative artificial intelligence]. The prompts used include [list of prompts]. The output from these prompts was used to [explain use].

Here is more information about how to cite the use of generative AI like ChatGPT in your work. The information below was adapted from “Acknowledging and Citing Generative AI in Academic Work” by Liza Long (CC BY 4.0).

The Modern Language Association (MLA) uses a template of core elements to create citations for a Works Cited page. MLA asks students to apply this approach when citing any type of generative AI in their work. They provide the following guidelines:

Cite a generative AI tool whenever you paraphrase, quote, or incorporate into your own work any content (whether text, image, data, or other) that was created by it. Acknowledge all functional uses of the tool (like editing your prose or translating words) in a note, your text, or another suitable location. Take care to vet the secondary sources it cites. (MLA)

Here are some examples of how to use and cite generative AI with MLA style:

Example One: Paraphrasing Text

Let’s say that I am trying to generate ideas for a paper on Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story “The Yellow Wallpaper.” I ask ChatGPT to provide me with a summary and identify the story’s main themes. Here’s a link to the chat . I decide that I will explore the problem of identity and self-expression in my paper.

My Paraphrase of ChatGPT with In-Text Citation

The problem of identity and self expression, especially for nineteenth-century women, is a major theme in “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (“Summarize the short story”).

Works Cited Entry

“Summarize the short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Include a breakdown of the main themes” prompt. ChatGPT. 24 May Version, OpenAI, 20 Jul. 2023, https://chat.openai.com/share/d1526b95-920c-48fc-a9be-83cd7dfa4be5

Example Two: Quoting Text

In the same chat, I continue to ask ChatGPT about the theme of identity and self expression. Here’s an example of how I could quote the response in the body of my paper:

When I asked ChatGPT to describe the theme of identity and self expression, it noted that the eponymous yellow wallpaper acts as a symbol of the narrator’s self-repression. However, when prompted to share the scholarly sources that formed the basis of this observation, ChatGPT responded, “As an AI language model, I don’t have access to my training data, but I was trained on a mixture of licensed data, data created by human trainers, and publicly available data. OpenAI, the organization behind my development, has not publicly disclosed the specifics of the individual datasets used, including whether scholarly sources were specifically used” (“Summarize the short story”).

It’s worth noting here that ChatGPT can “ hallucinate ” fake sources. As a Microsoft training manual notes, these chatbots are “built to be persuasive, not truthful” (Weiss &Metz, 2023). The May 24, 2023 version will no longer respond to direct requests for references; however, I was able to get around this restriction fairly easily by asking for “resources” instead.

When I ask for resources to learn more about “The Yellow Wallpaper,” here is one source it recommends:

“Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper: A Symptomatic Reading” by Elaine R. Hedges: This scholarly article delves into the psychological and feminist themes of the story, analyzing the narrator’s experience and the implications of the yellow wallpaper on her mental state. It’s available in the journal “Studies in Short Fiction.” (“Summarize the short story”).

Using Google Scholar, I look up this source to see if it’s real. Unsurprisingly, this source is not a real one, but it does lead me to another (real) source: Kasmer, Lisa. “Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s’ The Yellow Wallpaper’: A Symptomatic Reading.” Literature and Psychology 36.3 (1990): 1.

Note: ALWAYS check any sources that ChatGPT or other generative AI tools recommend.

For more information about integrating and citing generative artificial intelligence tools such as ChatGPT, please see this section of Write What Matters.

I acknowledge that ChatGPT does not respect the individual rights of authors and artists and ignores concerns over copyright and intellectual property in its training; additionally, I acknowledge that the system was trained in part through the exploitation of precarious workers in the global south. In this work I specifically used ChatGPT to assist with outlining chapters, providing background information about critical lenses, and creating “model” essays for the critical lenses we will learn about together. I have included links to my chats in an appendix to this book.

Critical theories: A targeted approach to writing about literature

Ultimately, there’s not one “right” way to read a text. In this book. we will explore a variety of critical theories that scholars use to analyze literature. The book is organized around different targets that are associated with the approach introduced in each chapter. In the introduction, for example, our target is literature. In future chapters you’ll explore these targeted analysis techniques:

- Author: Biographical Criticism

- Text: New Criticism

- Reader: Reader Response Criticism

- Gap: Deconstruction (Post-Structuralism)

- Context: New Historicism and Cultural Studies

- Power: Marxist and Postcolonial Criticism

- Mind: Psychological Criticism

- Gender: Feminist, Post Feminist, and Queer Theory

- Nature: Ecocriticism

Each chapter will feature the target image with the central approach in the center. You’ll read a brief introduction about the theory, explore some primary texts (both critical and literary), watch a video, and apply the theory to a primary text. Each one of these theories could be the subject of its own entire course, so keep in mind that our goal in this book is to introduce these theories and give you a basic familiarity with these tools for literary analysis. For more information and practice, I recommend Steven Lynn’s excellent Texts and Contexts: Writing about Literature with Critical Theory , which provides a similar introductory framework.

I am so excited to share these tools with you and see you grow as a literary scholar. As we explore each of these critical worlds, you’ll likely find that some critical theories feel more natural or logical to you than others. I find myself much more comfortable with deconstruction than with psychological criticism, for example. Pay attention to how these theories work for you because this will help you to expand your approaches to texts and prepare you for more advanced courses in literature.

P.S. If you want to know what my favorite book is, I usually tell people it’s Herman Melville’s Moby Dick . And I do love that book! But I really have no idea what my “favorite” book of all time is, let alone what my favorite book was last year. Every new book that I read is a window into another world and a template for me to make sense out of my own experience and better empathize with others. That’s why I love literature. I hope you’ll love this experience too.

writings in prose or verse, especially : writings having excellence of form or expression and expressing ideas of permanent or universal interest (Merriam Webster)

Critical Worlds Copyright © 2024 by Liza Long is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Pellissippi HOME | Library Site A-Z

Literary Criticism: Critical Literary Lenses

- Getting Started

- 1. What is Literary Criticism

Critical Literary Lenses

- Literary Elements

- Comparing/Contrasting Works, Characters, or Authors

- 3. Find Literary Criticism

- 4. Write Your Paper

- MLA Citation This link opens in a new window

A Critical Literary Lens influences how you look at a work. A great example that is often used, is the idea of putting on a pair of glasses, and the glasses affecting how you view your surroundings. The lens you choose is essentially a new way to focus on the work and is a great tool for analyzing works from different viewpoints. There are many approaches, but we will look at four common ones.

Socio-Economic (Marxist Criticism)

Questions to ask:

- What role does class play in the text?

- How does class affect the characters and the actions they choose?

- Maybe a character moves from one class to a new one, what are the implications?

- What characters have money? What characters are poor? What are the differences?

- Does money equate to power?

- Perhaps a rich character is a villainess and poor character is morally rich, why is this? What causes this?

Explore more:

- Marxist Criticism

Feminist/Gender

- Is the author male or female? How do they connect with the text?

- Are there traditional gender roles? Do characters follow these roles? How would they view a character that did not follow traditional roles?

- Are women minor characters in the text or do they take on a prominent role? What roles do they have? Does it relate back to the gender of the author?

- How does the author define gender roles?

- What role does society/culture play in gender roles/sexuality in the text?

- Would an LGBTQIA character be accepted in the text? Why or why not?

Explore More:

- Feminist Criticism

- Gender Studies and Queer Theory

Historical

- What time period was the work written, and what time period is the literary work taking place in? Is there a connection?