Search form

The legacy of 9/11: reflections on a global tragedy.

(Illustration by Michael S. Helfenbein)

Twenty years after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, the tragic consequences of that day continue to resonate across the world. On this somber anniversary, members of the Yale faculty reflect on the painful and complicated legacy of 9/11 and how the trauma of the event, which for a time created unity in the United States, has in the decades since led to a more divided nation and dangerous world.

Trauma, solidarity, and division

By Jeffrey Alexander Lillian Chavenson Saden Professor of Sociology, Faculty of Arts and Sciences

Societies shift between experiences of division and moments of solidarity. It is collective trauma that often triggers such shifts.

When Osama Bin Laden organized acts of horrific mass murder against civilians on September 11, 2001, he declared that “the values of this Western civilization under the leadership of America have been destroyed” because “those awesome symbolic towers that speak of liberty, human rights, and humanity have… gone up in smoke.” What happened, instead, was that Americans recast the fearful destruction as an ennobling narrative that revealed not weakness, but the strength of the nation’s democratic core.

Before 9/11, American had been experiencing a moment of severe political and cultural division. In its immediate aftermath, the national community was united by feeling, marked by the loving kindness displayed among persons who once had been friends, and by the civility and solicitude among those who once had been strangers …

Read more from Jeffrey Alexander

No clean break

By Joanne Meyerowitz Arthur Unobskey Professor of History and professor of American studies, Faculty of Arts and Sciences

Shortly after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, historians pointed to precedents: the surprise bombing of Pearl Harbor, say, and terrorist attacks — domestic and foreign — that had targeted civilians. They soon moved on to warnings against unnecessary and prolonged wars, with frequent reference to Vietnam, and to placing the security state within the long history of domestic surveillance, racial profiling, and violations of civil liberties. The common thread was that Sept. 11 did not represent a clean break with the past. It was not “one of those moments,” as The New York Times had claimed, “in which history splits” in two …

Read more from Joanne Meyerowitz

An embrace of profiling

By Zareena Grewal Associate professor American studies; ethnicity, race, and migration; and religious studies, Faculty of Arts and Sciences

In 2001, the New York City Police Department established a secret surveillance program that mapped and monitored American Muslims’ lives throughout New York City, and in neighboring states, including Connecticut. In 2011, journalists leaked internal NYPD documents which led to an outcry from public officials, activists, and American Muslim leaders who protested that such racial and religious profiling was not only an example of ineffective policing and wasteful spending of taxpayer dollars, but it collectively criminalized American Muslims. The leaked documents revealed that Yale’s Muslim Students Association was among the campus chapters targeted …

Read more from Zareena Grewal

A new outlet

By Paul Bracken Professor emeritus of management and political science, Yale School of Management

Following the Cold War, the U.S. foreign policy establishment was spoiling for another fight to overthrow tyranny. Yet there was no domestic support for such a war. Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait led to the first Gulf War. But the failure to end his regime left a good part of the establishment with a sense of unfulfilled destiny. These were the trends underway before 9/11. But there was no outlet to give them voice.

By linking a war on terror with a projection of our idea of democracy onto the Middle East, the attack on 9/11 provided that outlet …

Read more from Paul Bracken

A war game, gone terribly wrong

By Kishwar Rizvi Professor in the history of art, Faculty of Arts and Sciences

September 11, 2001, is a Tuesday. At 8:46 a.m. and 9:03 a.m., two hijacked planes fly into the towers of the World Trade Center. Six hours later, I give my first class of the year, in Street Hall. It is unclear how the afternoon will unfold, but as the class gathers, we find comfort in each other’s presence.

The unconditional empathy and bravery shown by my students that day 20 years ago is something I carry with me. It is a necessary requirement for studying and teaching about Islam today. Art and architecture, framed through social and political discourse, serve as important conduits for understanding the history and culture of the West and South Asia — the epicenter of the “War on Terror” launched soon after 9/11. I find clarity in the work of Shahzia Sikander and Lida Abdul, women artists from the region …

Read more from Kishwar Rizvi

For millions of refugees, the crisis continues

By Marcia C. Inhorn William K. Lanman, Jr. Professor of Anthropology and International Affairs; chair, Council on Middle East Studies

September 11 was a devastating event for the United States, causing the senseless deaths of nearly 3,000 Americans and the injury of more than 6,000 others. September 11 was also a tragedy for the Middle East, as the U.S. responded by initiating two wars, one in Afghanistan in 2001 and one in Iraq in 2003. These long-term and costly wars in the Middle Eastern region have killed thousands of innocent civilians and displaced millions of people.

Of the 26 million refugees and 80 million forcibly displaced people in the world today, the majority are from the Middle East, especially Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Indeed, we are now in the midst of an Afghan refugee crisis, the magnitude of which is yet to unfold …

Read more from Marcia C. Inhorn

The loss of history

By Eckart Frahm Professor of Near Eastern languages & civilizations, Faculty of Arts and Sciences

The events of 9/11 have led to actions on the part of the U.S. that have thoroughly transformed the Middle East. Unfortunately, despite an enormous investment of lives and money, the region remains deeply troubled. The world’s attention has been focused, for good reasons, on the political and humanitarian catastrophes that have befallen it. But for someone like me who is studying the civilizations of the ancient Near East, a particularly devastating aspect of the crisis has been its disastrous effect on the region’s cultural heritage …

Read more from Eckart Frahm

Tragedy for the world

By Samuel Moyn Henry R. Luce Professor of Jurisprudence and professor of history, Yale Law School

September 11 was a tragedy for America, but it prompted an American response that has been a tragedy for the world. After two decades of war, every place American force has touched has been made worse, with the risk of terrorism often exacerbated, and at the price of millions of lives and trillions of dollars.

More than this, even though Joe Biden has followed his two predecessors in withdrawing troops from Afghanistan, the authorities the American president has arrogated over two decades to send force abroad have not been reined in. Nor does the war on terror — as distinct from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq that started it — seem likely to end in the foreseeable future …

Read more from Samuel Moyn

Arts & Humanities

Campus & Community

How ‘shadow banning’ can silently shift opinion online

Ten Ph.D. students named 2023-24 Prize Teaching Fellows

The search for an affordable treatment option for liver disease

State Supreme Court sides with Yale law clinic in foreclosure case

- Show More Articles

What 9/11 Changed: Reflecting on the Cultural Legacy of the Attacks, 20 Years On

July 30, 2021 • By Caroline Newman, [email protected] Caroline Newman, [email protected]

- Caroline Newman, [email protected]

Even two decades later, the legacy of the attacks lingers not just in New York City, Washington D.C. or Pennsylvania, but around the world.

Sept. 11, 2001, is one of that those dates that divides history into a “before” and an “after.” The terrorist attacks that day tragically and permanently altered thousands of lives; they also changed the tenor of debate everywhere from the kitchen table to the halls of Congress.

Twenty years later, we asked experts from around the University of Virginia to comment on some of the biggest changes they saw, from foreign policy and immigration to literature and pop culture.

Their answers were especially interesting as the nation and the world confronts the COVID-19 pandemic, which, though different from 9/11 in many ways, will undoubtedly be another before-and-after moment in the history books.

Here’s what they had to say.

Related Story

Remembering 9/11

American political culture and campaigns.

The 9/11 attacks generated a unique political unity that seems almost impossible today, said Larry Sabato, director of UVA’s Center for Politics.

“Less than a year before, George W. Bush had been elected despite losing the popular vote, a controversial election that became even more controversial with the recount [and Supreme Court decision],” Sabato said. “There were still a lot of hard feelings, but 9/11 in many ways reunited the American people.” Bush went from losing the popular vote to having a 91% approval rating, “almost unheard-of.”

However, Sabato said, that image of unity in some ways masked discord we are still grappling with today.

President George W. Bush thanks a firefighter at Ground Zero in New York City. (Photo courtesy George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum)

“Despite Bush’s attempts to lower the temperature and direct Americans’ anger – understandable and righteous anger – toward those who actually committed the attacks, many completely innocent Muslim Americans were targeted and faced discrimination. Tragically, that is a part of human nature we are still struggling with,” Sabato said, noting the discrimination and violence Asian Americans have faced since the advent of COVID-19.

At the Center for Politics, Sabato and his team responded to 9/11 in part by increasing their global programming, eventually launching the Global Perspectives on Democracy program to host groups of all ages, from high school students to high-level government officials, for exchange programs and public events.

“We felt it was important to help Americans understand the world and the world to understand Americans and American democracy,” Sabato said. “I think that is one lasting lesson of 9/11: You cannot teach or practice American democracy in a vacuum.”

Literature & Culture

Associate professor of English Sandhya Shukla has taught her “Post 9/11 American Literature and Culture” course on and off since 2008. Immediately following the attacks, she said, many cultural representations of 9/11 focused on processing grief and trauma. But in time, the stories became more complicated, contending with all sorts of divides opened up by the events of that day.

“9/11 can be seen as both a radical rupture or shift in history, and also a flash point that really crystalized some long-held tensions in the U.S.’s relationship to the rest of the world, particularly in how we think about immigration, diasporas and religious fundamentalism,” Shukla said.

Among the materials she teaches are films like “United 93,” a documentary-style fiction about the passengers who crashed their hijacked plane into a Pennsylvania field, a sacrifice that likely prevented another attack on a U.S. landmark. Another film, “Man on Wire,” premiered in 2008, but focuses on Phillippe Petit’s 1974 high-wire walk between the towers of the World Trade Center, an event also depicted in the 2009 novel “Let the Great World Spin.” Both of these pieces use Petit’s balancing act as an allegory, Shukla said, and help students understand what has been lost culturally and politically with the physical destruction of an already contested symbol.

She also highlights “Netherland,” a 2008 novel by Joseph O’Neill about a Dutch-British immigrant’s experience in New York, which then-President Barack Obama chose as one of his favorite books in 2009.

A memorial outside of the Pentagon after the attacks. (Photo by James Harden, Library of Congress)

“To me, that novel, and especially Obama’s choice to praise it, signaled a change in how at least certain leaders wanted to see America, after seven years deep suspicion about globality. It seemed to mark a turn toward new commitments to multicultural societies and new ways of being in the world,” she said. Other texts like “The Reluctant Fundamentalist,” a 2007 novel by Mohsin Hamid about a Pakistani immigrant’s experience in post-9/11 New York and various sites of economic restructuring in Europe, Latin America and Asia, also added complexity to the cultural conversation around 9/11.

“The stories have gotten richer and more diverse in the years since the attacks, and we now have the benefit of history, seeing their longer-term effects of the attacks and America’s political responses to them play out,” she said.

Teaching the course in the fall of 2020, Shukla said she emphasized how students might think about 9/11 in relation to the pandemic and what COVID-19 has shown us about how connected we are, across all kinds of borders, but also how unequal, and the resulting opportunities and tensions.

“These two major events are not the same, obviously, but I do think 9/11 and the cultural responses to it can help us think about other crises of nationality and globality, like the one we are currently experiencing and will need to work through for many years to come,” she said.

Foreign Policy

Clearly, the terrorist attacks “greatly reduced policymakers’ tolerance for risk,” said Eric Edelman, a practitioner senior fellow at UVA’s Miller Center who retired from a U.S. Foreign Service career in 2009. Edelman held positions in the departments of State and Defense, as well as the White House, and served as undersecretary of defense for policy from 2005 to 2009.

“The tolerance for risk went down significantly, certainly for the Bush administration and I would argue for subsequent administrations as well,” Edelman said. “It may be only now, with the Biden administration, that caution has to some degree come to an end, though that is debatable as well. But choosing 9/11 as their date for withdrawing from Afghanistan, and more totally withdrawing from Afghanistan, suggests a higher tolerance for risk.”

The risks posed by terrorism might have distracted politicians and the public from other risks, Edelman said, especially those posed by other superpowers like China and Russia.

“The focus on terrorism and weapons of mass destruction, I think, may have diverted attention to some degree from China and the threat it represents,” he said. “That is now being remedied a bit, with more a focus on how the U.S. can remain competitive with China, but I do think 9/11 caused some delay in recognizing the risks posed by China and by Russia. That was an opportunity cost of the focus on counterterrorism.”

Domestic Policy

The attacks also significantly changed policymaking at home. Melody Barnes, executive director of the Karsh Institute of Democracy at UVA, was working in Congress on 9/11 as chief counsel to the late U.S. Sen. Edward M. Kennedy for his position on the Senate Judiciary Committee. She and other staff began to flee the Senate office buildings as they realized what was happening. As they gathered outside, she remembers hearing a loud, far-off explosion, likely from the attack on the Pentagon at about 9:30 a.m.

“It was surreal,” Barnes recalled. “We had no idea if the Capitol would be next.”

Barnes and her staff went to a colleague’s Capitol Hill home, where they stayed the rest of the day watching news coverage. That night, she finally drove home to Northern Virginia. She could smell the acrid smoke still coming from the Pentagon.

Still, she went back to work the next day, joining in a show of strength from Congress. However, another threat, an unknown package outside the Senate chamber, forced Senate staff to evacuate again, this time very quickly.

Melody Barnes recalled seeing smoke from the Pentagon as she finally drove home from Congress after the attacks. (Photo courtesy FBI Vault)

“I saw senators just start to run out of the Senate chamber, and someone came over and told us about a suspicious package and said every exit is open – run,” she recalled. “I remember running down the hall, wondering how long I had, if I was about to die. Those are the kinds of memories I have.”

Twenty years later, those memories have stayed with Barnes, who went on to direct the White House Domestic Policy Council under President Barack Obama before coming to UVA. She also sees through-lines in many policy issues, from the creation of the Department of Homeland Security after 9/11 to ongoing debates about privacy.

“Creating a new government department is something that is often talked about, but rarely happens,” Barnes said. “9/11 was the forcing mechanism to create the DHS and when things happen quickly, all of the rough edges don’t get smoothed out. Working through some of those issues took many years.”

9/11 also focused attention on surveillance and interagency communication, especially how law enforcement agencies communicate with each other.

“The way we think about security – how we move through airports and public spaces, how we secure our public buildings – changed significantly,” she said. With that came new privacy concerns and worries about excessive government surveillance.

“We have only rarely been threatened on American soil, and 9/11 in many ways ended a sense of innocence and freedom of movement that many Americans had,” Barnes said. “It also shifted issues of privacy and animated a renewed and more intense debate about how we balance our liberties, including privacy, with threats to the U.S., and how we do that without profiling people and generating discrimination. Those debates have not gone away; they continue to be heated and fraught.”

Those issues were particularly significant in the immigration debate, Barnes said.

Immigration Policy and Debate

On Sept. 6, 2001, Bush officials held publicized, orchestrated talks with Mexican President Vicente Fox, focused on a temporary worker visa program. Those talks, held just four days before the terrorist attacks, accurately reflect Bush’s initial stance on immigration, said David Leblang, the Ambassador Henry J. Taylor and Mrs. Marion R. Taylor Endowed Professor of Politics and professor of public policy.

“During and after the election, George W. Bush and other establishment Republicans tried to ‘rebrand’ the Republican Party as immigrant-friendly, and adopted several pro-immigration positions, especially focusing on labor and the economy,” he said.

Then, 9/11 happened and gave, as Leblang put it, “a tremendous amount of energy to border hawks,” with Americans understandably concerned about how the hijackers entered the country.

Twenty years later, Leblang said that rapid shift in sentiment has led to two lasting and influential changes. One is very concrete: the creation of the Department of Homeland Security, which absorbed control of immigration, including Customs and Border Control and Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE.

“Immigration was no longer a question about migration or who we are as a country or about labor market competition. It was a security issue; we saw the ‘securitization’ of immigration,” Leblang said. “That changed the nature of immigration enforcement quite dramatically.”

After the attacks, Bush, President Barack Obama and President Donald Trump deported record numbers of immigrants, going from about 18,000 criminal deportations in 2001 to 91,000 in 2012. That data does not include even more “voluntary departures,” when migrants are giving a choice between leaving and facing charges.

The second big change, Leblang said, came in public attitudes. “The attacks understandably injected terror into the immigration debate,” he said. “Pre-9/11, most of the conversation around immigration was about labor and the economy, not national security and terrorism. 9/11 gave energy to nativist and populist groups that did not want any immigration.”

The current wave of discrimination against Asian Americans in some ways resembles that post-9/11 shift, Leblang said, a jingoistic response to the threat of the coronavirus.

“I don’t think all of the tensions we are seeing now can be traced back to 9/11, but it is hard to talk about immigration today without talking about 9/11 and how it influenced this posture of deterrence and securitization or militarization,” he said.

Religion and Civil Religion

A December 2001 Pew Research survey found that the 9/11 attacks increased the prominence of religion in the U.S. “to an extraordinary degree,” with 78% of respondents agreeing that religion’s role in American life is growing, as opposed to 37% eight months earlier.

Matthew Hedstrom, an associate professor of religious studies specializing in modern American religion, said that bump was “a temporary spike” amid a broader trend of Americans leaving organized religion, begun in the 1990s. However, he said we are still feeling the effects of another kind of religion that grew after the attacks – what he called “civil religion.”

Across the country, religious practice spiked somewhat after 9/11, a spike that Matthew Hedstrom called temporary. Civil religion, he said, grew and lingered much longer. (Photo by Margaret M. deNeergaard, Library of Congress)

Before 9/11, the war in Vietnam and other hardships had somewhat eroded American civil religion, but the attacks gave it “a shot in the arm,” Hedstrom said.

He cites religiously influenced symbols of patriotism, such as songs like “God Bless America” or rituals like the Pledge of Allegiance, as examples. Often, those symbols had a Christian bent, Hedstrom said, fueling another question that shapes public discourse today – a divide between “Americans who see America as a Christian country with a God-given mission in the world, and Americans who do not.”

“That fault line in our politics makes it hard to compromise and easier to see people who disagree with you politically not just as political opponents, but as evil,” he said. “That is obviously one of the big challenges we face as a country, and I think 9/11 is part of the story of how those cultural and religious divides grew.”

The 2001 Pew survey also showed that respondents had a more favorable view of Muslim Americans since the attacks, indicating that efforts by Bush and others to discourage discrimination were having some effect. Hedstrom said that effect continues today to some extent, but that discrimination and hate crimes against Muslim Americans remain troubling.

“We are still seeing examples of hate crimes and discrimination today, still living in that unfortunate reality,” he said “I do think there is increased visibility of the Muslim American community, and that perhaps the attacks created a certain amount of education about Muslim Americans and Islamic beliefs. Muslim Americans have been part of this country since the earliest settlements of people from Europe and Africa, but our education and beliefs about America have not always reflected that. So, though hate crimes and profiling have unfortunately continued, there has also been greater visibility, awareness and education.”

Media Contact

Caroline Newman

Article Information

May 10, 2024

You May Also Like

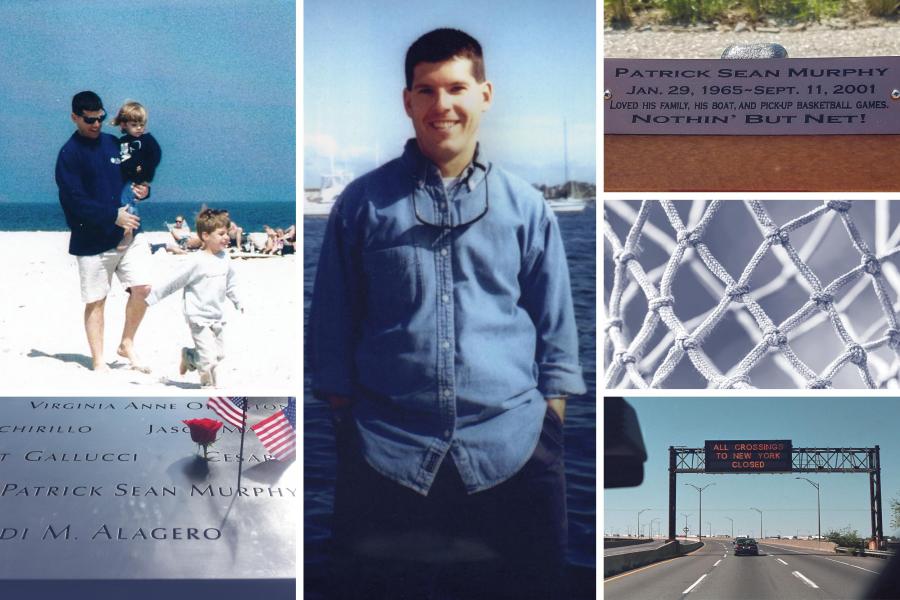

Love & Basketball: Memory of Alumnus Who Died in 9/11 Lives on Through Scholarship

Voices of 9/11: Maihan Far Alam

With the Pentagon Burning, He Thought, ‘This Is the Magnitude of Pearl Harbor’

Essays revisited: Reflecting on 9/11

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

In the days and weeks after Sept. 11, 2001, the Times ran dozens of analysis and opinion pieces examining how the events of that day might change the United States and the world. We asked some of the writers who contributed their thoughts after the tragedy to look back at what they wrote then and reflect on it from the vantage point of today.

Richard Rodriguez works at New America Media. His book on the influence of the desert on the Abrahmic religions will be published next year.

On the Sunday after 9/11, Rodriguez wrote eloquently that “it was a week when words failed us. We sensed ourselves entering some terrible epoch, but we did not have sufficient nouns and verbs.” Ten years later, the words are clearer, as is the extent of what was lost.

I believe the time has come to put away the ceremonies of 9/11—the politicians’ speeches at Ground Zero, the parade of children holding the photos of their dead fathers and mothers, the bag-pipes, the tolling bell, the roll call of the dead.

Those of us who were alive that day will always dread the annual alignment of those two numbers — nine, eleven -- the blue September sky; our thoughts will return to the ashes. Let that be the way of it. There is no moratorium on grief.

The dreadful mnemonic date has formed a seal over our minds. Something is wrong. It will not be fixed.

In generations past, America used wounds to form armies. Remember the Alamo! Remember the Maine! After the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt bore witness to December 7, “a date which will live in infamy.”

In the decade since the attacks of September 11th, Americans have turned inward. We have become a nation obsessed with guarding our borders, particularly the Mexican border, even as ghostly TSA images of our naked bodies reach upward, as though under arrest.

We eschew the international, except for the deserts from which the terrorists came. Under the banner of 9/11, President George W. Bush sent Americans to war against Iraq. We were crazed. Osama bin Laden was the leering genie within the explosions. We toppled Saddam Hussein. We ended up fighting Taliban tribesmen in Kandahar.

When American special forces killed Osama bin Laden in May (we do not remember the date), there was no pervading sense in America that the era of 9/11 was finished. Some Americans danced in the street, waved flags, honked their horns. The fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan went on.

What is maddening us is that the wars of 9/11 can have no ending, because we have no clear purpose, because they have no clear adversary. We are not fighting nations; we are fighting peasants and mercenaries and religious ideologues and millionaires. In the war against terrorism, there will never be an “eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month”; it will always be 9/11.

But an America that only guards against a dangerous world diminishes its power in the world. In the last ten years, China has usurped the noun Americans thought we held the patent to—the “future.”

While we have deployed troops backward, into the Bible, China has built dams in Africa and made trade agreements with South America. The Chinese have welcomed young men and women from the Third World to Chinese universities. While U.S. troops are killed building roads between tribal villages in Afghanistan, the Chinese sign mineral contracts in Kabul.

The “Arab spring” that began in Tunisia and spread throughout the Middle East has toppled dictators with whom our government maintained “relationships.” We want to feel encouraged by the youthful rebellions. We want to conflate rebellion with American democracy in the designs of the crowd. All the while, we worry the stage is being set for a coming Islamist revival.

Some in our national media have advanced the hope that American technology is liberating the young of the Middle East. Are Apple, Facebook and Twitter democratizing the region? My suspicion is that Americans are confusing conveyance with content. We credit the iPhone with ideological apps that the rest of the world does not necessarily buy.

Hemmed in by an adversarial world, we turn on each other: President Bush was, in the eyes of his critics on the left, a fool wound up by big business. President Barack Obama, according to his critics on the right, is a socialist and a Muslim. Our Congress has become an international scandal. Conservatives versus progressives.

About the only thing that Washington and the nation can seem to manage these days are monuments—we are monument mad, anniversary obsessed. Which leads us to Ground Zero, the tenth anniversary.

This year, put your hand on your heart for all who were lost, for all we have lost, then turn from this place and look at it no more, and see what our nation has become.

Geraldine Brooks, former Mideast correspondent and author, most recently, of the novel Caleb’s Crossing.

In a December 2001 essay titled “ Iraqi people deserve to be liberated ,” Brooks wrote: “Iraq is a far richer country than Afghanistan, gifted with oil, water, good farmland, scenic beauty, rare antiquities. Were it were not for the bleak and terrible regime of Hussein, it could be the showplace of the region. Now is the time to make some belated amends for a tragic mistake. Some in the Bush Cabinet want to strike Iraq to safeguard the West from future terrorism. That is a reason. But there is an even better one. It should be done for the sake of the Iraqis.”

When I wrote those words, I thought I knew Iraq pretty much as well as any non-Iraqi at that time could know it. I’d traveled there many times, in war and peace, visited its cities under oppression and during their brief liberation, in 1980s prosperity and 1990s decline. I’d met with dissidents and torture victims in Europe, Australia and the Mideast. I had seen the effects of Saddam’s brutal terror, but I hadn’t understood that it also acted as a vise, holding that nation together.

It might be possible to plead that in the run up to the war none of us could foresee the depth of fecklessness of the Bush/Cheney administration, or know just how profoundly the plan for the peace had been neglected. So ideological blindness begat the grim fiesta of lawlessness and looting, squandered Iraqi trust, inspired and enabled insurgency.

But the truth and the lessons of Iraq are more compelling and far simpler. Augustine knew them when he set out the basis of just war theory in the fourth century: One should never resort to war unless the threat is existential and there is no other way to answer it; success should be likely and the suffering created less than the suffering averted. Neither of the first two criteria applied to the Iraq war, and the others remain debatable.

Iraqis have had to endure a decade of fear and continue to live with a ravaged infrastructure. The birth pains of their freedom have been unnecessarily agonizing and their future remains uncertain. For us, meanwhile, the costs of war are everywhere apparent: in the shattered bodies of soldiers, in a glinting prosperity dulled by crushing debt, and in a national psyche coarsened by a war whose unequal sacrifice has demanded so much from a few and little more than jingoistic platitudes from the rest.

Peter Tomsen, U.S. special envoy and ambassador on Afghanistan from 1989 to 1992 and author of the just-published “The Wars of Afghanistan.”

In his October 2001 essay “ Past Provides Lessons for Afghanistan’s Future ,” Tomsen warned that: “If the U.S. military offensive is drawn out, and Washington lacks an overarching strategic vision for the region, Pakistan could unravel. Islamic militants would take to the streets, the already wobbly economy could fall and the army splinter into rival factions.” Today Tomsen is still worried.

We entered Afghanistan with the best of intentions, but 10 years later, it is clear that American policy toward Afghanistan and Pakistan has not succeeded.

There are those who will say we should have pressed the war harder, that we should have committed more forces. That was not the problem. Even 500,000 U.S. troops in Afghanistan could not bring peace as long as Pakistan’s army and military intelligence service, the ISI, continue to foster sanctuaries for international terrorist groups inside Pakistan.

Today, American and Afghan troops are under constant attack from a variety of Pakistan-supported organizations, including the Afghan Taliban, the Afghan Haqqani and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar networks, and three ISI-created Pakistani religio-terrorist organizations. Since 9/11, numerous international terrorists, including Faizal Shahzad, the would-be Times Square bomber, have been trained in Pakistani sanctuaries for extremists.

It is clear that Pakistan’s generals have no more intention of dismantling these safe havens now than they had before 9/11. If Washington does not finally deal with Pakistan’s duplicity, our stabilization efforts in Afghanistan will fail and the country will slip into yet another cycle of warfare.

American policy-makers must realize that the risk of taking a tougher approach to Pakistan is less, in the long run, than the risk of continuing the status quo. Ten years of inaction have not paid off. More troops and money are not the answer; nor is continuing to hope that Islamabad’s episodic cooperation with the CIA in eliminating specific terrorists will blossom into a productive working relationship. The United States needs an overarching, long-term policy toward Pakistan that would focus geo-strategic and bilateral pressure on Pakistan’s military leaders to end the Afghan war and stop international terrorism emanating from Pakistan. America and the international community could then focus on helping Afghanistan to once again become a neutral crossroads for Eurasian commerce rather than a proxy battlefield for predatory neighbors.

Naomi Klein, author most recently of “The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism”

In a September 2001 essay titled “ Game Over: The End of Warfare as Play ,” Klein noted that the United States had fought a series of wars in which it had experienced few casualties. “This is a country that has come to believe in the ultimate oxymoron: a safe war,” she wrote. The attacks of 9/11 would change that, she believed. “The illusion of war without casualties has been forever shattered.” Today, she’s not so sure.

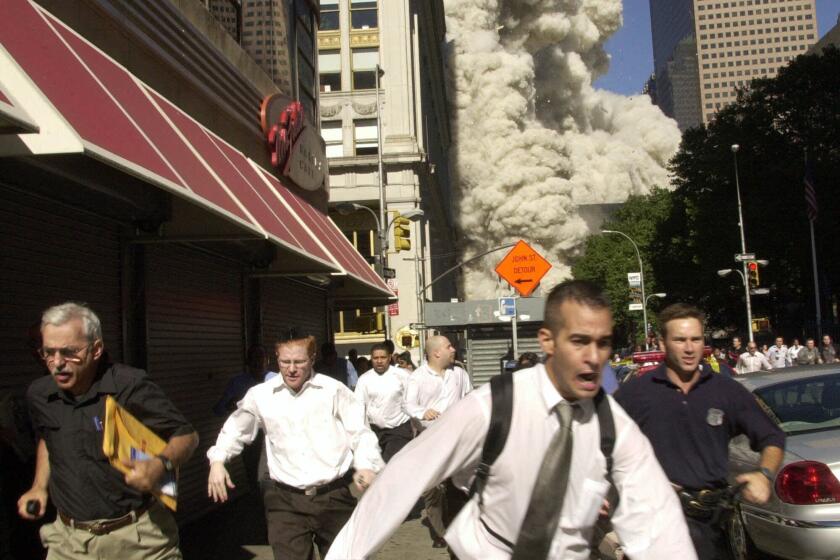

I suppose it was wishful thinking. As I watched footage of New Yorkers fleeing from the attacks, their terrified faces covered in dust from the collapsing towers, I was overwhelmed by how different these images were from the people-free videogame wars that my friends and I had grown up watching on CNN. Now that we were finally getting an unsanitized look at what it meant to be attacked from the air, I was sure it would change our hearts forever.

But the Bush Administration was determined to tightly police what we saw of the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, introducing “embedded” reporting, and banning photographs of returning caskets. They also let it be known that reporters who embedded themselves with local populations instead of with allied troops were acceptable military targets -- as attacks on Al Jazeera reporters in Afghanistan and Iraq made clear.

The wars being waged by our governments in our names are today more distant to us than ever before. . Some of the fighting is carried out by mercenaries, who die without so much as a mention in the papers. And drone attacks have ushered in something even more dangerous than the “safe war” -- the idea of “no touch” warfare. This sends a clear message to the civilians on the other side of our weapons that we consider our lives so much more valuable than theirs that we will no longer even bother showing up to kill them in person.

As we should have learned ten years ago, this is an extraordinarily dangerous message to send.

Doyle McManus, op-ed columnist

In March 2002, in a front page analysis piece titled “ U.S. Gets Back to Normal ,” McManus, then the paper’s Washington bureau chief, concluded that the news wasn’t how much the attacks had changed America, but how little.

“Six months after Sept. 11,” he wrote, “here’s what’s changed:

“The federal government, its budget and its public image. The focus of American foreign policy. Security measures at airports, seaports and border crossings. The nation’s sense of patriotism, cohesion and vulnerability. The lives of almost 1.4 million people in the armed services…. [and] the victims, their families and friends.

“Here’s what hasn’t changed much: Everything else.” Today, he says, that’s still mostly true.

Since Sept. 11, the federal government has continued to grow. Spending has mushroomed on war-fighting, intelligence-gathering and homeland security. Security measures at airports and seaports are even tighter than before – although the government promises we’ll be allowed to keep our shoes on some day.

But that hasn’t made us love the federal government more. In the frightened months after Sept. 11, polls found that Americans’ trust in the government’s ability to do the right thing soared; in the years since, that same measure has plummeted.

That’s largely because the issue that concerns Americans most is no longer terrorism, but economic stagnation – and the federal government hasn’t succeeded in overcoming that threat.

As for “the nation’s sense of patriotism [and] cohesion,” the patriotism is still there, but the cohesion we discovered in 2001 was evanescent. A divisive war in Iraq and a virtual civil war over fiscal policy quickly turned politics nasty again.

In 2002, I asked Harvard social scientist Robert D. Putnam if 9/11 could have a lasting positive effect on our sense of community, and he was skeptical – appropriately, as it turned out.

“After almost any crisis, calamity or natural disaster, there’s a sudden spike in community-mindedness, whether it’s an earthquake, a flood or a snowstorm in Buffalo,” he said. “But these spikes don’t last. Over time, the community feeling dissipates.”

The only exception, Putnam noted, was Pearl Harbor – because World War II called on every citizen to sacrifice. This time, only a few were called on; the rest of us were encouraged to go shopping.

The focus of American policy has shifted, too. Immediately after 9/11, it was stopping further terrorism; then it was managing the consequences of our Global War on Terror, especially in Iraq and Afghanistan. But now the focus is broader – and, increasingly, economic. As the just-retired chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, Adm. Mike Mullen, often said, “The single biggest threat to our national security is our debt.”

The war on terror isn’t over, even though it’s no longer called by that name. There are still almost 100,000 U.S. troops in Afghanistan, almost 50,000 in Iraq. The real cost of those wars – more than 5000 killed in action, more than 45,000 injured – changed many lives irrevocably.

But for most Americans, the most striking fact remains not how much 9/11 changed, but how little.

Graham Allison is director of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and a former assistant secretary of Defense.

In November 2001, Allison wrote that “After Sept. 11, a nuclear terrorist attack can no longer be dismissed as an analyst’s fantasy. … As the international noose tightens around Al Qaeda’s neck, the group will become more desperate and audacious.” Ten years later, he says we have made some progress in keeping nuclear weapons out of terrorist groups’ hands.

On 9/11, 19 terrorists killed more Americans than the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. If the terrorists had been in possession of a nuclear weapon, the attack might have killed 300,000.

Post 9/11, President Bush, and now President Obama, have declared nuclear terrorism the biggest threat to American national security.

The United States has taken the lead in investing more than $10 billion and countless hours in securing and eliminating nuclear weapons and material worldwide. President Obama’s Nuclear Security Summit in 2010 focused exclusively on the threat. As a result of these efforts, thousands of weapons and material that could have produced thousands more weapons are better secured today than they were a decade ago. In Russia, which has the world’s largest stockpile of nuclear weapons and material, hundreds of sensitive sites have been secured; 17 countries have eliminated their weapons-usable material stockpiles entirely.

But to prevent a nuclear 9/11, all nuclear weapons and weapons-usable material everywhere must be secured to a “gold standard” — beyond the reach of terrorists or thieves.

On that agenda, much remains to be done. The ever-more fragile state of Pakistan has the world’s most rapidly expanding nuclear arsenal. North Korea today has enough material for about 10 nuclear bombs. And Iran now has enough low enriched uranium, if further processed, for four nuclear weapons. One of these weapons in the hands of terrorists could mean an “American Hiroshima”

The price of success in preventing a nuclear 9/11 remains eternal vigilance.

James Fallows is a national correspondent for the Atlantic and an author.

In September 2001, Fallows wrote in his essay “ Step One: Station a Marshal Outside Every Cockpit Door ” that: “There may not be a next time, as everything involving air travel becomes more constrained. The tightening of security, while necessary, almost certainly will have aspects of fighting the last war. We may spend years refining passenger-screening processes, only to have the next terrorist explosive arrive by barge.

… Any system careful enough to eliminate sophisticated terrorists also would be cumbersome enough to negate the speed advantage of traveling by air.”

I wish my fears had had turned out to be wholly unfounded. And when it comes to the specific scenario of bombs aboard barges, I’m glad to say that they have been, at least so far.

Unfortunately, there was a much broader challenge that many people, including me, foresaw from the very beginning of the push toward a sweeping emphasis on “homeland security” and the “global war on terror.” This was the risk that, in the name of “protecting” ourselves against future threats, we might ultimately give up, distort or sacrifice the values that made a free society most worth defending. I am sorry to say that this fear has largely been realized.

We can’t be sure of much when it comes to future acts of terrorism, but one certainty is that there will never be “another 9/11.” That attack depended for its shocking success on people not imagining that airliners would be used as large-scale urban bombs. Everyone in the world now understands that possibility, which is why a “9/11-style” attack simply cannot be pulled off again. If the passengers and crew on a plane did not stop future hijackers from flying a fuel-laden plane into a city, the Air Force would.

We also know that our reflexive response to threats has given tremendous leverage to any handful of people who conceive of a new means of attack. Because of one foiled shoe-bombing attempt, hundreds of millions of air passengers worldwide continue removing their shoes before boarding planes. Osama bin Laden’s associates spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on their attacks. America’s chosen response has cost the nation trillions of dollars in direct military and security expenditures, not to mention the other costs.

The long-standing truth about terrorism is that the worst damage it inflicts is not through the initial attack but rather through the self-defeating and extreme response it often evokes. It is past time for America to consider a security response that does more damage to potential attackers and less to ourselves.

Shireen T. Hunter is a visiting professor at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service .

In her September 2001 OpEd (“ Wake-Up Call for the Islamic World ”), Hunter argued that Muslims themselves have been the ones most adversely affected by the extremist ideas and groups that have sprung up amid them, “giving credence to the worst perceptions of Islam as a rigid, aggressive, reactionary and xenophobic creed.” She recommended that Muslim nations “stop using Islam as an instrument of foreign policy” and to “abandon outdated utopian and expansionist schemes.”

Unfortunately, in the intervening years, Muslim nations have continued this behavior. Thus, in their bids to expand their regional influence, countries such as Saudi Arabia, Iran and Pakistan have stoked the fires of sectarianism in Iraq, Bahrain, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Yemen. Saudi Arabia has even resorted to manipulating sectarian divisions in Lebanon and Syria in its attempt to eliminate the Iranian influence. Meanwhile, Iran has continued to support its Shiite co-religionists in Lebanon.

The upshot of this situation is that in the Muslim world today, sectarian divisions and hatreds are even deeper. This seriously hampers the establishment of peace and even a modicum of stability, and dims the prospect of consensual politics. Instead, the manipulation of sectarian divides and rivalries for power and influence, notably between Iran and Saudi Arabia, has led to new tragedies such as that in Bahrain where the Shiite majority is being brutally repressed by the Sunni rulership.

Meanwhile, Al Qaeda Inc. branches have sprung up in Iraq, Yemen and elsewhere, and remain strong, despite the deaths of Osama bin Laden and other top leaders; the Taliban are resurgent in Afghanistan; and the ultra-conservative Salafists have developed strong footholds in Egypt, Tunisia and Jordan.

All this time, the needs and aspirations of the people have been ignored, leading them to revolt as we have seen during the “Arab spring.” Yet revolts and revolutions seldom lead to democracy. Generally they result in politics of revenge, chaos and eventually another form of dictatorship. Muslim countries have missed an opportunity.

Alexander Cockburn coedits the CounterPunch website and writes for the Nation and other publications.

“The lust for retaliation traditionally outstrips precision in identifying the actual assailant,” Cockburn wrote in September 2001 (“ The Next Casualty: Bill of Rights? ”). “The targets abroad will be all the usual suspects -- the Taliban or Saddam Hussein, who started off as creatures of U.S. intelligence. The target at home will be the Bill of Rights.”

It was maybe an hour after the north tower of the World Trade Center collapsed that I heard the first of a thousand pundits that day saying that America might soon have to sacrifice “some of those freedoms we have taken for granted.” They said this with grave relish, as though the Bill of Rights – the first 10 amendments to the U.S. Constitution — was somehow responsible for the onslaught, and should join the rubble of the towers, carted off to New Jersey and exported to China for recycling into abutments for the Three Gorges Dam.

Of course it didn’t take 9/11 to give the Bill of Rights a battering. It is always under duress and erosion. Where there’s emergency, there’s opportunity for the enemies of freedom. The Patriot Act, passed in October 2001 and periodically renewed in most of its essentials in the Bush and Obama years, kicked new holes in at least six of our Bill of Rights protections.

The government can search and seize citizens’ papers and effects without probable cause, spy on their electronic communications, and has, amid ongoing court battles on the issue, eavesdropped on their conversations without a warrant. Goodbye to the right to a speedy public trial with assistance of counsel. Welcome indefinite incarceration without charges, denial of the assistance of legal counsel and of the right to confront witnesses or even have a trial. Until beaten back by the courts, the Patriot Act gave a sound whack at the 1st Amendment, too, since the government could now prosecute librarians or keepers of any records if they told anyone the government had subpoenaed information related to a terror investigation.

Let’s not forget that a suspect may be in no position to do any confronting or waiting for trial since American citizens deemed a threat to their country can be extrajudicially and summarily executed by order of the president, with the reasons for the order shielded from the light of day as “state secrets”. That takes us back to the bills of attainder the Framers expressly banned in Article One of the U.S. Constitution, about as far from the Bill of Rights as you can get. We can thank the War on Terror, launched after 9/11, for it.

Jonathan Turley is a law professor at George Washington University.

In his September 13 Op Ed (“ Cries of “war” stumble over the law ”), Turley warned against the government seeking “greater flexibility” in responding to terrorists by treating criminal attacks “as a matter of war.” “Our system,” he wrote, “requires that legal means be used to achieve legal ends. We decide those means and ends within the general confines of the Constitution.” How has the founding document fared?

As the smoke was still rising from the Pentagon and World Trade Center, it became quickly evident that some of the greatest damage from the September 11th attacks would not come from without but from within our nation.

There was an almost immediate effort by Bush officials to change the definition of war. Rather than declare war on Afghanistan (where Bin Laden was sheltered), President George W. Bush wanted to declare war on terrorism. It was no rhetorical triviality. Bush decided to invoke the heightened constitutional powers of a wartime president by declaring war on what was a category of crime. Because there could never be a total, final defeat of terrorism, this “war” would become permanent – as would the heightened powers of the president.

Ten years later, the country remains “at war,” with President Barack Obama expanding many of the national security powers of his predecessor and, in the Libyan war, claiming his own re-definition of war: “a time-limited, scope-limited military action.”

Of course, the ominous signs in 2001 were realized in a myriad of other ways, from the establishment of the first American torture program to the widespread use of targeted assassinations, including operations killing American citizens. Ironically, I wrote then of the possibility of a new law that could govern the use of assassination, one that would deny a president unilateral authority to kill individuals and would reduce the need to invoke war powers. Instead, the Bush administration claimed full wartime authority as well as radically expanding the use of assassination as an unchecked presidential power. The claim of unilateral presidential authority to kill even United States citizens has been embraced by Obama.

What ultimately fell on that terrible day proved to be some of our most important constitutional structures. Tragically, it is a degree of damage that cannot be claimed by Al Qaeda alone.

Laila Al-Marayati, Los Angeles physician

In a January 2002 essay titled “ An Identity Reduced to a Burka ,” Al-Marayati wrote: “It should be obvious that the critical element Muslim women need is freedom, especially the freedom to make choices that enable them to be independent agents of positive change.”

After the tragic events of 9/11, there were some genuine attempts to improve understanding and awareness between peoples. But that good will has given way in recent years to increased anti-Muslim sentiment in the U.S. and around the world, prejudices that were reflected in a recent Gallup poll. Muslim women who choose to wear hijab take the brunt of the hostility. They are subject to verbal assault and to misdirected legal actions such as in the ban on the headscarf imposed in France. For centuries, Muslim women have been in the crosshairs of the supposed conflict between Islam and the West. Shortly before the invasion of Afghanistan, we saw images, almost daily, of burqa-clad women who had been suffering under the Taliban. But what most people forget is that they were suffering long before 9/11 and that they continue to experience hardship today in most parts of the country. In 2001, their plight was exploited for political expediency, to help drum up support among freedom-loving Americans for a war that has yet to make life better for the common Afghan woman. Over the past decade, Muslim women around the world have continued to demand their rights and claim their position alongside their Muslim brothers by advocating for changes in legal systems that discriminate against them, by educating their daughters, and by challenging harmful traditions that have no basis in Islam. Many of them are now engaged in the struggle of their lives to achieve the kind of freedom that Muslims living in the U.S. appreciate. It is too soon to predict the outcome, but we should have no doubt that women will be at the forefront of positive change. We should support their efforts, not for political expediency, but because it is the right thing to do.

More to Read

Opinion: Why did Israel miss so many warnings of the Hamas attack? Here’s one answer

Dec. 11, 2023

Opinion: We were one nation, united in mourning, when President Kennedy died. Not anymore

Nov. 25, 2023

Opinion: 9/11 offers awful lessons for what could happen with a Gaza ground invasion

Oct. 16, 2023

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Granderson: Biden is right to nudge Israel toward protecting civilians in Rafah

Claire Messud mixes truth and invention to tell her French Algerian family’s story

May 10, 2024

Opinion: Struggling to find meaning and happiness at work? Here’s where you may have gone wrong

Editorial: Biden’s plan to reschedule marijuana may finally end ‘Reefer Madness’

How 9/11 Changed the World

The World Trade Center buildings in New York City collapsed on September 11, 2001, after two airplanes slammed into the twin towers in a terrorist attack. Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images

BU faculty reflect on how that day’s events have reshaped our lives over the last 20 years

Bu today staff.

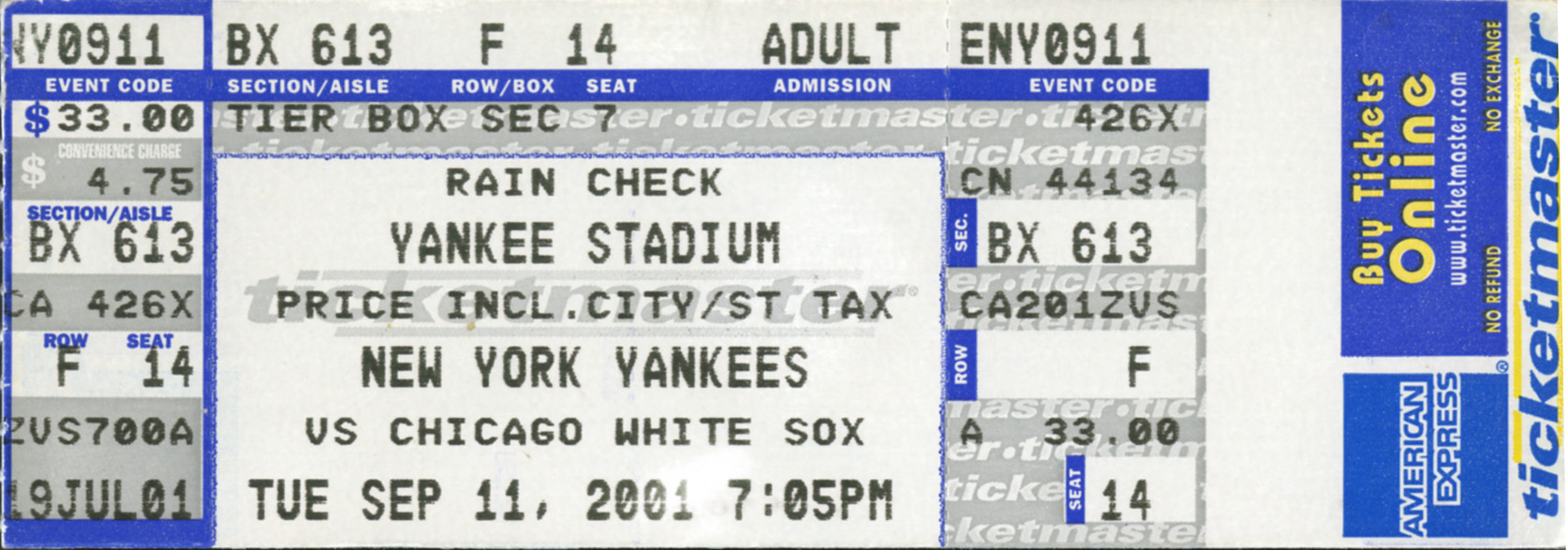

Saturday, September 11, 2021, marks the 20th anniversary of 9/11, the largest terrorist attack in history. On that Tuesday morning, 19 al-Qaeda terrorists hijacked four American commercial flights destined for the West Coast and intentionally crashed them. Two planes—American Airlines Flight 11 and United Airlines Flight 175—departed from Boston and Flight 11 struck New York City’s World Trade Center North Tower at 8:46 am and Flight 175 the South Tower at 9:03 am, resulting in the collapse of both towers. A third plane, American Airlines Flight 77, leaving from Dulles International Airport in Virginia, crashed into the Pentagon at 9:37 am, and the final plane, United Airlines Flight 93, departing from Newark, N.J., crashed in a field in Shanksville, Pa., at 10:03 am, after passengers stormed the cockpit and tried to subdue the hijackers.

In the space of less than 90 minutes on a late summer morning, the world changed. Nearly 3,000 people were killed that day and the United States soon found itself mired in what would become the longest war in its history, a war that cost an estimated $8 trillion . The events of 9/11 not only reshaped the global response to terrorism, but raised new and troubling questions about security, privacy, and treatment of prisoners. It reshaped US immigration policies and led to a surge in discrimination, racial profiling, and hate crimes.

In observance of the anniversary, BU Today reached out to faculty across Boston University—experts in international relations, international security, immigration law, global health, terrorism, and ethics—and asked each to address this question: “How has the world changed as a result of 9/11?”

Find a list of all those with ties to the BU community killed on 9/11 here.

Explore Related Topics:

- Immigration

- International Relations

- Pardee School of Global Studies

- Public Policy

- Share this story

- 43 Comments Add

BU Today staff Profile

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

There are 43 comments on How 9/11 Changed the World

this is very scary to me.

Yes this is very scary

This was a very sad moment in time but we need to remember the people that sacrificed themselves to save us and the people that died during this event. It was sad but at least it brought us closer together. I wonder what the world would be like if 9/11 never happened?..

Yes that is a good thing to rember…

We will all remember 9/11, a very important moment in our life, and we honor the ones who sacrificed their lives to save others in there.

It changed the world forever, it is infact a painful memory to remember

I feel bad for all the families that had family and friends die.

i feel bad for all the people and their family and friends that died

9/11 is tragic and it will always be remembered though I have to say that saying 9/11 changed the word is quite an overstatement. More like how it changes America in certain ways and the ones responsible for it but saying something like what you said makes it sound like it was Armageddon or something.

Whether or not those of us in other countries like it, for the last several decades and certainly still in the current time, when something changes the USA in significant ways that impact policy, legislation, education, the economy, health care, etc. (not to mention the ways in which public opinion drives the American political machine), the US’s presence on the international stage means those changes ripple outward through their foreign policy, treatment of both residents/citizens of the USA and local people where the USA has a military, economic and/or other presence around the world.

The complex web of international agreements, alliances, organizational memberships, and financial interdependency means that events that happen locally often have both direct and indirect implications, short and long term, around the world, for individuals and for entire segments of society.

As for the direct results of 20 years of military response to 9/11 on civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan, it certainly changed their world.

The original BU 9/11 Memorial webpage is still up: https://www.bu.edu/remember/index.html

Reading through the remembrances from that day onward …

Omg scary .

I honor them all.

I wonder how much time people had to get out before the building collapsed

the south tower collapsed in 10 seconds.

Yes but it didnt colapse untill 56 minutes after it was hit

Shall all the people who risked their lives, never be forgotten.

am i blind or was there no mention of how it actually affected the world afterwards??

I know right?

My dad died in 9/11, He was a great pilot

Wow. I’m really sorry for your loss I hope you can still go far in life even without your dad. Sometimes you just have to go with your gut and let them go.

i dont really think you understood that comment

i just read the story and im so sade for the dad that died . If i was there i wouls of creiyed and i saw someone in the chare that someone dad died and i felt so bad when i saw the comment but i dont know if that is real but if it is i feal bad for you if my dad died or my mom i woulld been so sade i would never get over it but this story changed my life when i read it.Also 1 thing i hoop not to any dads diead because i feel bad fo thos kids.

yo all the dads and moms died all of them will never get forgoten every single one of them

Never forget, always remember

everyone is talking about the twin towers but what about the pentagon.

I know, right?

it is super scary

Sorry for all the people who Lost their family

Thanks for helping me with this report, and yes so sorry for all yall who lost family

So, so sorry to all y’all who lost family

I am deeply sorry for anyone who lost family, friends, co workers, or anybody you once knew. This really was a tragedy to so many.

my dad almost died from the tower

very scary but needs too be remembered!

I have to say this is most definitely a U.S. American write up. Saying the word is an overstatement in many ways. It would be more better if you were to specifically point out you mean the US and those others involved with the attacks. Overall if we are going to be completely factual “people/individuals” are the ones who change things depending on whatever. The world changes every day since the start of time.

While I agree with your first point, I would say that the attacks did in fact change the world. At the very least, they changed the way airline security is done everywhere.

great article,

I believe that the people, who sacrificed their lives in flight 93, the one that crashed in Pennsylvania, resonated the most with me, as it could have gone anywhere, and they sacrificed themselves to save more. I am deeply sorry for all losses, but I hope we remember this crucial moment in history to learn from our mistakes in global affairs, but also honor those who sacrificed themselves in all the attacks.

Post a comment. Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Latest from BU Today

Commencement 2024: what you need to know, pov: decision to reclassify marijuana as a less dangerous drug is long overdue, esl classes offered to bu dining services workers, sargent senior gives back to his native nairobi—through sports, providing better support to disabled survivors of sexual assault, class of 2024: songs that remind you of your last four years at boston university, cloud computing platform cloudweaver wins at spring 2024 spark demo day, a birder’s guide to boston university, boston teens pitch biotech concepts to bu “investors” at biological design center’s stem pathways event, the weekender: may 9 to 12, dean sandro galea leaving bu’s school of public health for washu opportunity, meet the 2024 john s. perkins award winners, comm ave runway: may edition, stitching together the past, two bu faculty honored with outstanding teaching awards, advice to the class of 2024: “say thank you”, school of visual arts annual bfa thesis exhibitions celebrate works by 33 bfa seniors, q&a: why are so many people leaving massachusetts, killers of the flower moon author, and bu alum, david grann will be bu’s 151st commencement speaker, photos of the month: a look back at april at bu.

- RUSSO-UKRAINIAN WAR

- BECOME A MEMBER

Reflections on 9/11 Twenty Years After

Post title post title post title post title.

We all have our own memories associated with the tragedy of 9/11. In my case I can remember going to Ground Zero shortly after the attacks and noticing that awful, pungent smell of the place, as if the terrorists had opened up some special, sulfurous path to hell. Later, directing the commission investigating what happened, I have vivid memories of tramping through the Tarnak Farms camp in Afghanistan where Osama bin Laden had once had a headquarters. Or there we were in a Washington office, leaning toward a loudspeaker to listen one more time to the cockpit voice recording recovered from United Flight 93, matched up with our reconstruction of the behavior of the aircraft, painstakingly trying to reconstruct moments of agony and astonishing courage.

We all have a need to construct meaning from occasions like these. In the rare cases when a historical event, especially a traumatic event, stirs emotions on a massive scale, touching many millions of people, it enters popular culture. Great numbers of people soon form beliefs about what happened and why. People usually try to make sense of events in ways that fit their prior understanding of how the world works. But sometimes a catalytic event opens their mind to new possibilities — in this case the scale of danger that might be posed by an organization of zealots based on the other side of the planet in one of the most primitive countries on earth.

At its core, though, the 9/11 operation was an effort to deform the actual nature of the struggle going on within the Muslim world. These extremists, relatively powerless within their world, sought to elevate themselves by waging war against the United States, launching an attack that Americans could not ignore. In that sense, they were successful. That success was meant to elevate their faction of violent Islamists in their local struggles for cultural power. But every characterization of this war that reinforces a “United States versus Islamists” picture can divert and distract from the main story.

Consider the faces that the Muslim world has presented to the world. During the 1990s and culminating on 9/11, some Islamist extremists preferred to place the root of their troubles elsewhere, in America or Europe. This agenda was sometimes attractive to clusters of alienated expatriates living overseas and others whose restless energy is displaced onto a distant, enemy abstraction. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed , for instance, was truly a man without a country. On 9/11 the world was introduced to one face of this struggle: a set of fanatical mass killers. That image lingers.

But flash forward ten years later, to September 2011, when for six months the world watched Syrians protest against their tyranny. These unarmed men and women gathering in the streets faced every horror that a clever, malignant regime and its creatures could devise. They suffered the deaths and terrifying disappearances of family members and friends, a toll then numbered in the thousands. Then — against all odds — they turned out again the next Friday, and the next. For this American, raised to black-and-white television images of civil rights protesters facing their oppressors, the smuggled, fragmentary images of what the Syrian protesters endured, week after week, month after month, presented as astonishing and heroic a display of raw, sustained civic courage as I have ever seen, anywhere in the world. This image should linger too.

Flash forward again, ten years after that, to September 2021. Amid the recent chaos in Afghanistan, a global view of the continuing civil conflicts wracking the Muslim world, from Niger to Indonesia , invites a broader historical perspective. My lifetime has coincided with a generational struggle in the Muslim world about how to cope with modernity and globalization. The contemporary and most violent phase of this struggle began in 1979, with revolts and revolutions in Iran, Afghanistan, and Saudi Arabia. These immediately ignited major wars and defined often violent contests for leadership in the Muslim world.

Over the past 42 years these struggles have flamed or merely smoldered — they never ended. As a historian, I am reminded of the struggles — internal and transnational — that wracked the Christian world for more than a hundred years across the 16th and 17th centuries, or the long 19th and 20th century struggles about how to organize modern industrial societies. It took a long time for those struggles to subside. The Muslim world has not yet found the ingredients of civilizational peace.

The United States was always secondary to this primary struggle in the Muslim world. The main participants sought America as villain or as ally. For a time, reacting understandably to the 9/11 attacks but then adding the catastrophically misjudged invasion and occupation of Iraq, the United States seemed to place itself at the center of this struggle. But now, as the United States has receded from such a central place in the Muslim struggles, there are fresh opportunities to reassess whether, where, and how the United States and other outsiders can play some constructive role in helping the Muslim world find that civilizational peace.

A terrible crisis is also an occasion for discovering more about ourselves, about the worst and the best that it brings out in our society. We saw that Americans can produce the war crimes symbolized by the 2003 abuses of prisoners at Abu Ghraib . And Americans produced the daring professionalism displayed by an “ Abbottabad ,” the May 2011 operation that killed bin Laden. Thus we can use the anniversary of 9/11 to reflect once again on who we are, about who we can be, when our society confronts violent extremism.

Before the 9/11 attack there was a classic paradox in thinking about the terrorist danger, a paradox of prevention. As the 9/11 Commission observed in its 2004 report : “It is hardest to mount a major effort while a problem still seems minor. Once the danger has fully materialized, evident to all, mobilizing action is easier — but it then may be too late.” Al-Qaeda was most vulnerable in the years before 9/11. But before the catastrophic scale of the potential threat was manifest, massive action to counter it — like serious U.S. military efforts against the Afghan sanctuary — seemed so disproportionate as to be inconceivable. This was a genuine paradox. It did not have an easy or obvious solution.

That pre-9/11 paradox of prevention about the Islamist danger is long gone. (It now applies to other problems, like the global response to the pandemic danger.) A different kind of paradox has now taken its place: a paradox of adjustment.

The danger of global Islamist terrorism is greatly reduced from what it was on 9/11. An attack could still happen at any time. A really large-scale gun massacre — like that in Mumbai in 2008 or in Norway in 2011 or Paris in 2015 — is another obvious danger. Any attack will be publicized sensationally.

Thus any president who downplays the danger, trying to right-size the enemy and put the danger into a more normal proportion, invites humiliation if there is an attack. If there is no attack, public acts of reassurance invite an unwanted dulling of concern.

For both these reasons, the cultural momentum of 9/11 rolls forward. The result in 2021 is the public image of the enemy that the commission described in 2004: “Al Qaeda and its affiliates are popularly described as being all over the world, adaptable, resilient, needing little higher-level organization, and capable of anything. The American people are thus given the picture of an omnipotent, unslayable hydra of destruction.” The paradox of adjustment is that efforts to right-size, to normalize, a reduced risk seem … too risky.

Yet the reality is that the most serious threats are posed by a relatively tiny number of people, fewer in number and less well-organized than the production crew of any one of Hollywood’s larger films. A handful of deluded people derive most of their power not from their strength or the power of their ideals. They get their power from us — from our society and our culture.

This paradox of adjustment also is genuinely tough to solve. If there is a way out, it may just be a gradual process of the kind that has slowly unfolded during the last ten years. A catalytic event noticed by many millions, like the death of bin Laden, helped politicians to turn the page.

Contemporary societies will remain vulnerable to the abilities of even a few people to do terribly disruptive things. As the Jan. 6 assault by American extremists on the U.S. Capitol illustrated so well, that feature of our age is not unique to the danger posed by Islamist fanatics. A principal function of 21st century government will be to manage a process of healthy adjustment to the kinds of risks that are endemic to this generation, developing more systemic and transnational defenses to more systemic and transnational threats, which include other kinds of transnational criminal organizations.

At the cultural level, a process of adjustment includes adjustment to failures. For there will be failures. The supreme measure of a mature, professional institution — or government — is how it handles failure: its capacity for honest self-examination and thoughtful accountability. This is one reason why my commission colleagues and I took a hard view of the poor quality of work exhibited by parts of the government in their initial reconstructions of what happened on the morning of the 9/11 attacks. This dimension of institutional integrity is, in the long run, vital to the country’s well-being.

In air travel, for example, where societies have adjusted to constant risks of catastrophic failures, maybe the greatest virtues of America’s National Transportation Safety Board are cultural and political. Aside from the particular talents of its employees, the board represents a habit of thought and earned trust. Something goes horribly wrong, and many people lose their lives. A respected institution will examine what happened professionally, rigorously. It will explain to the community what it learned. The community will further reduce the risks. And millions of people will board airplanes each day. They go on with their lives.

Philip Zelikow, a dean and historian at the University of Virginia, was the executive director of the 9/11 Commission.

Image: U.S. Coast Guard (Photo by Tom Sperduto)

A Plan to Revitalize the Arsenal of Democracy

Rewind and reconnoiter: is america still born to rule the seas with claude berube, the east and south china seas: one sea, near seas, whose seas.

Opinion: Reflections on 9/11 20 years later

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

The San Diego Union-Tribune will share essays about 9/11 all week long from a variety of local voices.

Readers React

Opinion: Your Say on 9/11 memories and the lessons learned from the attacks

We asked readers: Where were you on 9/11? What went through your mind that day and how has it changed your view of the world, then and now?

Sept. 10, 2021

Opinion: My son was killed by the 9/11 attack. His last moments still haunt me.

When I look back, I realize how much I lost, his sister lost and his father lost, but, mostly, I think of all Ted lost.

Sept. 3, 2021

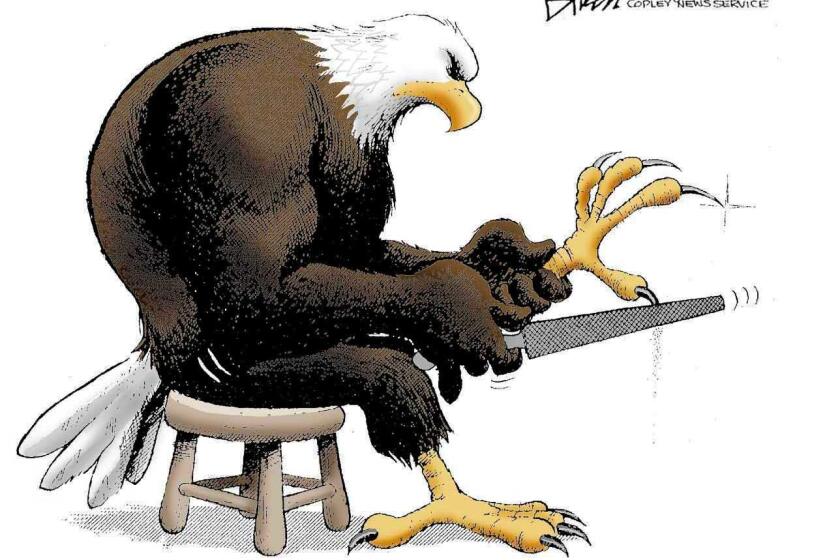

I wanted my Sept. 11 cartoon to be unique. I didn’t expect it to take on a life of its own.

The cartoon was put on everything from T-shirts to hats to military patches. Someone even hung a copy of it at Ground Zero.

Opinion: The effect of 9/11 on the U.S.-Mexico border is still evident today

We built a massive new government apparatus and shrouded the whole thing in secrecy.

Sept. 9, 2021

Opinion: I thought we were safe in Washington, D.C. I was wrong.

I saw chaos and confusion with bumper-to-bumper cars and people frantically walking or running to get anywhere else but Capitol Hill.

Sept. 7, 2021

Opinion: Two decades after 9/11, many questions are left unanswered

Moral panics leave a trail of catastrophic results.

Opinion: In school, they teach us about the time before 9/11. What about the time after?

Hopefully, when the time comes, we will be able to tell them that we made a better America.

Opinion: After 9/11, something inside me changed. I knew I wanted to serve in the Armed Forces.

My story is not dissimilar from many of my friends who joined the Marine Corps post-9/11.

Opinion: We need to consider Muslim students when teaching 9/11 in the classroom

Muslim students attending public school are targets of social and school community stereotypes.

Sept. 8, 2021

Opinion: Forgetting the ‘war on terror’ makes us susceptible to repeating history

In the end, the war on terror wasted more than $2 trillion of public money while the U.S. is unable to provide for so many people.

Opinion: The longest U.S. war ended amid feelings of confusion and fright

America’s system of justice and Congress failed to hold accountable the sordid civilians who instigated an illegal war and blundered the war on terror.

Opinion: Instagram posts and donations are great, but we must do more for Afghan refugees

If we ever want to be trusted by the rest of the world again, we have to bring home all of our allies.

Sept. 2, 2021

Opinion: California lawmakers erase Arab American issues. We want to be acknowledged.

Since 9/11, Arab Americans have been whitewashed from America’s collective consciousness, only existing when the topic is terrorism.

Opinion: How 9/11 led to the largest pro bono program in the history of American law

San Diego had the largest number of volunteer lawyers outside of New York City.

Opinion: I escaped the Taliban in Afghanistan, but my thoughts are with those I left behind

I kept looking for the American troops to get help. But they were nowhere to be found.

Opinion: In post-9/11 America, my ethnicity and religious identity are political

Why am I, as a woman, a Muslim, and an Arab, still radioactive in “neutral” environments?

Opinion: As a deaf person traveling on 9/11, I was the last to know what was going on

Twenty years later, I’m still haunted every time I fly and wonder if tragedy will strike.

Opinion: Two decades after 9/11, it’s not any better for Arabs and Muslims

Now is the time, 20 years later, to finally step into learning about everyone

Opinion: Being in New York City on 9/11 taught me about the power of community

Sometimes great adversity brings out our better selves.

Opinion: As a Vietnamese refugee, the crisis in Kabul reminds me of the Fall of Saigon

And I am hopeful for the people who were evacuated from Afghanistan and might arrive in San Diego

Opinion: I was babysitting my friend’s children on 9/11. I never asked them what they recall until now.

Eventually, I picked up the boys from school. I was an emotional wreck inside.

Opinion: ‘If they could hit the U.S., then they could target any city or country’

All day in Tijuana you could feel the city brace for the possibility of an attack.