When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

PLOS Pathogens

PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

Food Security

PLOS publishes a broad range of Open food security research that is essential to global food availability, access, utilization, and stability. Explore pivotal interdisciplinary research across key food security fields including crop science, nutrition, and food systems.

Explore food security research from PLOS

PLOS food security research addresses the global issues of food availability, exacerbated by the compounding impacts of climate change, demographic change, geopolitics and economic shocks.

Our Open Access multidisciplinary research papers showcase innovative approaches and technologies that help address key research areas in line with relevant United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including overcoming boundaries in both crop sciences and food systems.

Through rigorous academic research and engagement with a broad range of societal stakeholders, we aim to effect systemic, evidence-based transformation across all aspects of global food access and security.

Stay up-to-date on food security research from PLOS

Research spotlights

As a leading publisher in the field, these articles showcase research that has influenced academia, industry and/or policy.

Potential of breadfruit cultivation to contribute to climate-resilient low latitude food systems

Factors associated with dietary diversity among pregnant women in the western hill region of Nepal: A community based cross-sectional study

Food security and small holder farming in Pacific Island countries and territories: A scoping review

Food security research topics.

PLOS publishes research across a broad range of topics. Take a look at the latest work in your field.

Climate-smart agriculture

Food prices

Food loss and waste

Sustainable agriculture

Water use in agriculture

Crop science

Crop and livestock disease

Supply chains

Explore the latest research developments in your field

Our commitment to Open Science means others can build on PLOS precision food security research and data to advance the food security field. Discover selected popular food security research below:

A meta-analysis of the adoption of agricultural technology in Sub-Saharan Africa

Climate smart agriculture and global food-crop production

A novel intervention combining supplementary food and infection control measures to improve birth outcomes in undernourished pregnant women in Sierra Leone: A randomized, controlled clinical effectiveness trial

Does agricultural cooperative membership impact technical efficiency of maize production in Nigeria: An analysis correcting for biases from observed and unobserved attributes

Saltwater intrusion and climate change impact on coastal agriculture

Uncontained spread of Fusarium wilt of banana threatens African food security

Estimating impact of food choices on life expectancy: A modeling study

Maximising sustainable nutrient production from coupled fisheries-aquaculture systems

Rapid global phaseout of animal agriculture has the potential to stabilize greenhouse gas levels for 30 years and offset 68 percent of CO 2 emissions this century

Assessment of drinking water access and household water insecurity: A cross sectional study in three rural communities of the Menoua division, West Cameroon

Levels of heavy metals in soil and vegetables and associated health risks in Mojo area, Ethiopia

Combining viral genetic and animal mobility network data to unravel peste des petits ruminants transmission dynamics in West Africa

Browse the full PLOS portfolio of Open Access food security articles

38,630 authors from 175 countries chose PLOS to publish their food security research*

Reaching a global audience, this research has received over 24,887 news and blog mentions ^ , research in this field has been cited 219,213 times after authors published in a plos journal*, related plos research collections.

Covering a connected body of work and evaluated by leading experts in their respective fields, our Collections make it easier to delve deeper into specific research topics from across the breadth of the PLOS portfolio.

Check out our highlighted PLOS research Collections:

Sustainable Cropping

Domestic Animal Genetics

Future Crops

Stay up-to-date on the latest food security research from PLOS

Related journals in food security

We provide a platform for food security research across various PLOS journals, allowing interdisciplinary researchers to explore food security research at all preclinical, translational and clinical research stages.

*Data source: Web of Science . © Copyright Clarivate 2024 | January 2004 – February 2024 ^Data source: Altmetric.com | January 2004 – February 2024

Breaking boundaries. Empowering researchers. Opening science.

PLOS is a nonprofit, Open Access publisher empowering researchers to accelerate progress in science and medicine by leading a transformation in research communication.

Open Access

All PLOS journals are fully Open Access, which means the latest published research is immediately available for all to learn from, share, and reuse with attribution. No subscription fees, no delays, no barriers.

Leading responsibly

PLOS is working to eliminate financial barriers to Open Access publishing, facilitate diversity and broad participation of voices in knowledge-sharing, and ensure inclusive policies shape our journals. We’re committed to openness and transparency, whether it’s peer review, our data policy, or sharing our annual financial statement with the community.

Breaking boundaries in Open Science

We push the boundaries of “Open” to create a more equitable system of scientific knowledge and understanding. All PLOS articles are backed by our Data Availability policy, and encourage the sharing of preprints, code, protocols, and peer review reports so that readers get more context.

Interdisciplinary

PLOS journals publish research from every discipline across science and medicine and related social sciences. Many of our journals are interdisciplinary in nature to facilitate an exchange of knowledge across disciplines, encourage global collaboration, and influence policy and decision-making at all levels

Community expertise

Our Editorial Boards represent the full diversity of the research and researchers in the field. They work in partnership with expert peer reviewers to evaluate each manuscript against the highest methodological and ethical standards in the field.

Rigorous peer review

Our rigorous editorial screening and assessment process is made up of several stages. All PLOS journals use anonymous peer review by default, but we also offer authors and reviewers options to make the peer review process more transparent.

Food security and nutrition and sustainable agriculture

Related sdgs, end hunger, achieve food security and improve ....

Description

Publications.

As the world population continues to grow, much more effort and innovation will be urgently needed in order to sustainably increase agricultural production, improve the global supply chain, decrease food losses and waste, and ensure that all who are suffering from hunger and malnutrition have access to nutritious food. Many in the international community believe that it is possible to eradicate hunger within the next generation, and are working together to achieve this goal.

World leaders at the 2012 Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) reaffirmed the right of everyone to have access to safe and nutritious food, consistent with the right to adequate food and the fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger. The UN Secretary-General’s Zero Hunger Challenge launched at Rio+20 called on governments, civil society, faith communities, the private sector, and research institutions to unite to end hunger and eliminate the worst forms of malnutrition.

The Zero Hunger Challenge has since garnered widespread support from many member States and other entities. It calls for:

- Zero stunted children under the age of two

- 100% access to adequate food all year round

- All food systems are sustainable

- 100% increase in smallholder productivity and income

- Zero loss or waste of food

The Sustainable Development Goal to “End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture” (SDG2) recognizes the inter linkages among supporting sustainable agriculture, empowering small farmers, promoting gender equality, ending rural poverty, ensuring healthy lifestyles, tackling climate change, and other issues addressed within the set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals in the Post-2015 Development Agenda.

Beyond adequate calories intake, proper nutrition has other dimensions that deserve attention, including micronutrient availability and healthy diets. Inadequate micronutrient intake of mothers and infants can have long-term developmental impacts. Unhealthy diets and lifestyles are closely linked to the growing incidence of non-communicable diseases in both developed and developing countries.

Adequate nutrition during the critical 1,000 days from beginning of pregnancy through a child’s second birthday merits a particular focus. The Scaling-Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement has made great progress since its creation five years ago in incorporating strategies that link nutrition to agriculture, clean water, sanitation, education, employment, social protection, health care and support for resilience.

Extreme poverty and hunger are predominantly rural, with smallholder farmers and their families making up a very significant proportion of the poor and hungry. Thus, eradicating poverty and hunger are integrally linked to boosting food production, agricultural productivity and rural incomes.

Agriculture systems worldwide must become more productive and less wasteful. Sustainable agricultural practices and food systems, including both production and consumption, must be pursued from a holistic and integrated perspective.

Land, healthy soils, water and plant genetic resources are key inputs into food production, and their growing scarcity in many parts of the world makes it imperative to use and manage them sustainably. Boosting yields on existing agricultural lands, including restoration of degraded lands, through sustainable agricultural practices would also relieve pressure to clear forests for agricultural production. Wise management of scarce water through improved irrigation and storage technologies, combined with development of new drought-resistant crop varieties, can contribute to sustaining drylands productivity.

Halting and reversing land degradation will also be critical to meeting future food needs. The Rio+20 outcome document calls for achieving a land-degradation-neutral world in the context of sustainable development. Given the current extent of land degradation globally, the potential benefits from land restoration for food security and for mitigating climate change are enormous. However, there is also recognition that scientific understanding of the drivers of desertification, land degradation and drought is still evolving.

There are many elements of traditional farmer knowledge that, enriched by the latest scientific knowledge, can support productive food systems through sound and sustainable soil, land, water, nutrient and pest management, and the more extensive use of organic fertilizers.

An increase in integrated decision-making processes at national and regional levels are needed to achieve synergies and adequately address trade-offs among agriculture, water, energy, land and climate change.

Given expected changes in temperatures, precipitation and pests associated with climate change, the global community is called upon to increase investment in research, development and demonstration of technologies to improve the sustainability of food systems everywhere. Building resilience of local food systems will be critical to averting large-scale future shortages and to ensuring food security and good nutrition for all.

State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020

Updates for many countries have made it possible to estimate hunger in the world with greater accuracy this year. In particular, newly accessible data enabled the revision of the entire series of undernourishment estimates for China back to 2000, resulting in a substantial downward shift of the seri...

Food and Agriculture

Our planet faces multiple and complex challenges in the 21st century. The new 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development commits the international community to act together to surmount them and transform our world for today’s and future generations....

Food Security and Nutrition in Small Island Developing States (SIDS)

The outcome document of Rio+20, “The Future We Want” (United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, June 2012) acknowledged that SIDS remains a special case for sustainable development. Building on the Barbados Programme of Action and the Mauritius Strategy, the document calls for the conv...

Global Blue Growth Initiative and Small Island Developing States (SIDS)

Three-quarters of the Earth’s surface is covered by oceans and seas which are an engine for global economic growth and a key source of food security. The global ocean economic activity is estimated to be USD 3–5 trillion. Ninety percent of global trade moves by marine transport. Over 30 percent of g...

FAO Strategy for Partnerships with the Private Sector

The fight against hunger can only be won in partnership with governments and other non-state actors, among which the private sector plays a fundamental role. FAO is actively pursuing these partnerships to meet the Zero Hunger Challenge together with UN partners and other committed stakeholders. We ...

FAO Strategy for Partnerships with Civil Society Organizations

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) is convinced that hunger and malnutrition can be eradicated in our lifetime. To meet the Zero Hunger Challenge, political commitment and major alliances with key stakeholders are crucial. Only through effective collaboration with go...

FAO and the 17 Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals offer a vision of a fairer, more prosperous, peaceful and sustainable world in which no one is left behind. In food - the way it is grown, produced, consumed, traded, transported, stored and marketed - lies the fundamental connection between people and the planet, ...

Emerging Issues for Small Island Developing States

The 2012 UNEP Foresight Process on Emerging Global Environmental Issues primarily identified emerging environmental issues and possible solutions on a global scale and perspective. In 2013, UNEP carried out a similar exercise to identify priority emerging environmental issues that are of concern to ...

Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

This Agenda is a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity. It also seeks to strengthen universal peace in larger freedom, We recognize that eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including extreme poverty, is the greatest global challenge and an indispensable requirement for su...

Farmer’s organizations in Bangladesh: a mapping and capacity assessment

Farmers’ organizations (FOs) in Bangladesh have the potential to be true partners in, rather than “beneficiaries” of, the development process. FOs bring to the table a deep knowledge of the local context, a nuanced understanding of the needs of their communities and strong social capital. Increasing...

Good practices in building innovative rural institutions to increase food security

Continued population growth, urbanization and rising incomes are likely to continue to put pressure on food demand. International prices for most agricultural commodities are set to remain at 2010 levels or higher, at least for the next decade (OECD-FAO, 2010). Small-scale producers in many developi...

The State of Food Insecurity in the World

When the 69th United Nations General Assembly begins its General Debate on 23 September 2014, 464 days will remain to the end of 2015, the target date for achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDG). A stock-taking of where we stand on reducing hunger and malnutrition shows that progress in hu...

SDG Global Business Forum 2024

The 2024 SDG Global Business Forum will take place virtually as a special event alongside the 2024 High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF), the United Nations central platform for the follow-up and review of the SDGs. The Forum will place special emphasis on the SDGs under

Expert Group Meeting on SDG2 and its interlinkages with other SDGs

The theme of the 2024 High-Level Political Forum (HLPF) is “Reinforcing the 2030 Agenda and eradicating poverty in times of multiple crises: the effective delivery of sustainable, resilient and innovative solutions”. The 2024 HLPF will have an in-depth review of Sustainable Development Goa

Expert Group Meetings for 2024 HLPF Thematic Review

The theme of the 2024 High Level Political Forum (HLPF) is “Reinforcing the 2030 Agenda and eradicating poverty in times of multiple crisis: the effective delivery of sustainable, resilient and innovative solutions”. The 2024 HLPF will have an in-depth review of SDG 1 on No Poverty, SDG 2 on Zero Hu

International Workshop on “Applications of Juncao Technology and its contribution to alleviating poverty, promoting employment and protecting the environment”

According to the United Nations Food Systems Summit that was held in 2021, many of the world’s food systems are fragile and not fulfilling the right to adequate food for all. Hunger and malnutrition are on the rise again. According to FAO’s “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023

Second Regional Workshop on “Applications of Juncao Technology and its Contribution to the Achievement of Sustainable Agriculture and the Sustainable Development Goals in Africa” 18 - 19 December 2023

Ⅰ. Purpose of the Workshop At the halfway point of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the application of science and technology in developing sustainable agricultural practices has the potential to accelerate transformative change in support of the Sustainable Development Goals. In that r

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) 2023 Launch

On 12 July 2023 from 10 AM to 12 PM (EDT), FAO and its co-publishing partners will be launching, for the fifth time, the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) report at a Special Event in the margins of the ECOSOC High-Level Political Forum (HLPF). The 2023 edition

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022 (SOFI) Launch

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World is an annual flagship report to inform on progress towards ending hunger, achieving food security and improving nutrition and to provide in-depth analysis on key challenges for achieving this goal in the context of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021 (SOFI)

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021 (SOFI 2021) report presents the first evidence-based global assessment of chronic food insecurity in the year the COVID-19 pandemic emerged and spread across the globe. The SOFI 2021 report will also focus on complementary food system solu

Committee on World Food Security (CFS 46)

Ministerial meeting on food security and climate adaptation in small island developing states.

The proposed meeting will offer SIDS Ministers and Ambassadors the opportunity to explore the implications of the SAMOA Pathway as it relates to food security and nutrition and climate change adaptation. The ultimate objective is to enhance food security, health and wellbeing in SIDS. Ministers an

- January 2015 SDG 2 SDG2 focuses on ending hunger, achieving food security and improved nutrition and promoting sustainable agriculture. In particular, its targets aims to: end hunger and ensure access by all people, in particular the poor and people in vulnerable situations, including infants, to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round by 2030 (2.1); end all forms of malnutrition by 2030, including achieving, by 2025, the internationally agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under 5 years of age, and address the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women and older persons (2.2.); double,by 2030, double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists and fishers, including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment (2.3); ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices that increase productivity and production, that help maintain ecosystems, that strengthen capacity for adaptation to climate change, extreme weather, drought, flooding and other disasters and that progressively improve land and soil quality (2.4); by 2020, maintain the genetic diversity of seeds, cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and their related wild species, including through soundly managed and diversified seed and plant banks at the national, regional and international levels, and promote access to and fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge, as internationally agreed (2.5); The alphabetical goals aim to: increase investment in rural infrastructure, agricultural research and extension services, technology development and plant and livestock gene banks , correct and prevent trade restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets as well as adopt measures to ensure the proper functioning of food commodity markets and their derivatives and facilitate timely access to market information, including on food reserves, in order to help limit extreme food price volatility.

- January 2014 Rome Decl. on Nutrition and Framework for Action The Second International Conference on Nutrition (ICN2) took place at FAO Headquarters, in Rome in November 2014. The Conference resulted in the Rome Declaration on Nutrition and the Framework for Action, a political commitment document and a flexible policy framework, respectively, aimed at addressing the current major nutrition challenges and identifying priorities for enhanced international cooperation on nutrition.

- January 2012 Future We Want (Para 108-118) In Future We Want, Member States reaffirm their commitments regarding "the right of everyone to have access to safe, sufficient and nutritious food, consistent with the right to adequate food and the fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger". Member States also acknowledge that food security and nutrition has become a pressing global challenge. At Rio +20, the UN Secretary-General’s Zero Hunger Challenge was launched in order to call on governments, civil society, faith communities, the private sector, and research institutions to unite to end hunger and eliminate the worst forms of malnutrition.

- January 2009 UN SG HLTF on Food and Nutrition Security The UN SG HLTF on Food and Nutrition Security was established by the UN SG, Mr Ban Ki-moon in 2008 and since then has aimed at promoting a comprehensive and unified response of the international community to the challenge of achieving global food and nutrition security. It has also been responsible for building joint positions among its members around the five elements of the Zero Hunger Challenge.

- January 2002 Report World Food Summit +5 The World Food Summit +5 adopted a declaration, calling on the international community to fulfill the pledge, made at the original World Food Summit in 1996, to reduce the number of hungry people to about 400 million by 2015.

- January 2000 MDG 1 MDG 1 aims at eradicating extreme poverty and hunger. Its three targets respectively read: halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people whose income is less than $1.25 a day (1.A), achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all, including women and young people (1.B), halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people who suffer from hunger (1.C).

- January 1996 Rome Decl. on World Food Security The Summit aimed to reaffirm global commitment, at the highest political level, to eliminate hunger and malnutrition, and to achieve sustainable food security for all. Thank to its high visibility, the Summit contributed to raise further awareness on agriculture capacity, food insecurity and malnutrition among decision-makers in the public and private sectors, in the media and with the public at large. It also set the political, conceptual and technical blueprint for an ongoing effort to eradicate hunger at global level with the target of reducing by half the number of undernourished people by no later than the year 2015. The Rome Declaration defined seven commitments as main pillars for the achievement of sustainable food security for all whereas its Plan of Action identified the objectives and actions relevant for practical implementation of these seven commitments.

- January 1992 1st ICN The first International Conference on Nutrition (ICN) convened at the FAO's Headquarters in Rome to identify common strategies and methods to eradicate hunger and malnutrition. The conference was organized by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) and was attended by delegations from 159 countries as well as the European Economic Community, 16 United Nations organizations, 11 intergovernmental organizations, and 144 non-governmental organizations.

- January 1986 Creation of AGROSTAT (now FAOSTAT) Since 1986, AGROSTAT, now known as FAOSTAT, has provided cross sectional data relating to food and agriculture as well as time-series for some 200 countries.

- January 1979 1st World Food Day World Food Day is celebrated each year on 16 October to commemorate the day on which FAO was founded in 1945. Established on the occasion of FAO Twentieth General Conference held in November 1979, the first World Food Day was celebrated in 1981 and was devoted to the theme "Food Comes First".

- Food Security and Nutrition - A Global Issue

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- Research Guides

- Introduction

- UN Milestones

- Key UN Bodies

- Consulting the Experts

- UN Publications

- Non-UN Publications

- Databases & E-resources

About this Guide

The Food Security and Nutrition Guide provides a platform for available, UN and non-UN resources on Food Security, Nutrition and related topics.

2022 Global Report on Food Crises

Launch of the 2022 Global Report on Food Crises - Hybrid Press Conference.

Briefing by Arif Husain, World Food Programme’s Chief Economist, and Rein Paulsen, the Food and Agriculture Organization’s Director of Emergencies.

Related Library Research Guides

- Climate Change: A Global Issue

- UN Documentation: Environment

Definition - Food Security

The 1974 World Food Summit defined food security as:

... availability at all times of adequate world food supplies of basic foodstuffs to sustain a steady expansion of food consumption and to offset fluctuations in production and prices. ( Report of the World Food Conference, Rome 5-16 November 1974. New York )

In chapter 2 of the FAO publication, Trade Reforms and Food Security: conceptualizing the linkages, the definition of the term Food Security is presented as a flexible concept which has evolved over time.

The Committee on World Food Security in document CFS 2012/39/4 has provided further official definition to Food Security and related terms.

For more information on how the definition has evolved, see the FAO publication: Trade Reforms and Food Security: Conceptualizing the Linkages- Chapter 2:2

The Food Loss and Waste Accounting and Reporting Standard , (FLW) provide the first-ever set of global definitions and reporting requirements to quantify and report on food loss and waste.

- Next: UN Milestones >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 3:49 PM

- URL: https://research.un.org/en/foodsecurity

Advertisement

Exploring food security as a multidimensional topic: twenty years of scientific publications and recent developments

- Open access

- Published: 09 August 2022

- Volume 57 , pages 2739–2758, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Maria Stella Righettini 1 &

- Elisa Bordin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0308-1742 2

3537 Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The scientific literature dealing with food security is vast and fragmented, making it difficult to understand the state of the art and potential development of scientific research on a central theme within sustainable development.

The current article, starting from some milestone publications during the 1980s and 1990s about food poverty and good nutrition programmes, sets out the quantitative and qualitative aspects of a vast scientific production that could generate future food security research. It offers an overview of the topics that characterize the theoretical and empirical dimensions of food security, maps the state of the art, and highlights trends in publications’ ascending and descending themes. To this end the paper applies quantitative/qualitative methods to analyse more than 20,000 scientific articles published in Scopus between 2000 and 2020.

Evidence suggests the need to find more robust links between micro studies on food safety and nutrition poverty and macro changes in food security, such as the impact of climate change on agricultural production and global food crises. However, the potential inherent in the extensive and multidisciplinary research on food safety encounters limitations, particularly the difficulty of theoretically and empirically connecting the global and regional dimensions of change (crisis) with meso (policy) and micro (individual behaviour) dimensions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

Agroecological principles and elements and their implications for transitioning to sustainable food systems. A review

What is a framework? Understanding their purpose, value, development and use

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Food insecurity is a timely and multidimensional problem positioned at the crossroads between the right to food and health in developing and rich, industrialized countries. However, it is unclear how scientific production reflects this multidimensionality overall and whether the recent COVID-19 pandemic has shed new light on the issues at stake. The analysis presented in this article aims to give a systematic review and meta-analysis of the vast amount of scientific food security research produced over the past twenty years. This work aims to offer an overview of the topics that characterize food security’s theoretical and empirical dimensions, map state of the art, and highlight trends in scientific publications’ ascending and descending themes. A systematic literature review sets out quantitative and qualitative aspects which could generate future food security research.

Since the 1960s, with the approval of precursor USA federal anti-poverty programs (Esobi et al. 2021 ; Nestle 2019 ; Swann 2017 ), interest in preventing the adverse effects of poverty has broadened and deepened scientific interest in the field of how to guarantee food access to the neediest people. Since then, various framings, reflecting differences in meaning and problem formulation and coming from different territorial and disciplinary perspectives, have highlighted the contested relationship between social, economic, and environmental circumstances to food access and nutrition experiences (Dowler and O’Connor 2012 ). In the 1960s, creating the World Food Program (WFP) was a prominent example of the institutionalization of the ‘food for development’ framework. The food crisis of 1972–74 marked a turning point in food security insurance schemes and led to better coordination between donor countries. Then, the first official mention of food security was in the United Nations report presented at the World Food Conference in 1974 (McKeon 2014 ). In the 1980s and 1990s, food security was broadened to include physical and economic access to food and consider women’s role in poverty alleviation. Therefore, what has come to be termed food security and nutrition security has been controversial, reflecting multiple, not always coordinated, governmental policies and multifaceted theoretical and research fields.

The most used definition of food security was developed during the 1996 World Food Summit organized by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (Mechlem 2004 ). It resembles the definition of the right to food (Maxwell and Smith 1992 ; Smith et al. 1993 ). Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life (FAO 2003). Food security has become a priority focus for donor states and cooperation with developing countries to reduce poverty and systemic environmental, economic, and social causes of hunger. It has five conceptual dimensions: nutritional status, utilization, accessibility, availability, and stability (Gross et al. 2000). However, unlike food security, nutrition security refers only to the individual’s (mal)nutritional status due to diet regime, food intake, and health status (Gross et al. 2000).

Academic research developed many approaches to food insecurity during the 1980s and 1990s. The right-to-food-based approach to food security suggests that human dignity, rights acknowledgment, transparency, government accountability, citizens’ empowerment, food, and wellbeing should be considered in welfare programs. The right-to-food approach required governments to adopt specific programs and meet precise obligations to combat poverty (Maxwell 1996 ). The right to food was not merely a means to achieve food security; rather, it was seen as a broader, more encompassing, and distinct objective. The seminal works of Amartya Sen on poverty during the 1980s (Sen 1980 , 1981 , 1982 ) raised controversy over nutritional norms and intensified the debate on the interrelations between food access and poverty reduction interventions. Food security is seen as an integral part of social security, understood as the “prevention by social means, of a deficient standard of living irrespectively of whether these are the results of chronic deprivation or temporary adversity” (Burgess and Stern 1991 :4). We should point out that this debate regarded achieving food security in the poorest developing countries and the richest developed ones, where obesity and malnutrition among low-income people increased. The multifaceted nature of food security is entrenched in its measurement complexity (in terms of life expectancy or income). To understand the causes of deprivation and fragility associated with the lives of increasing portions of the population, food security scholars have striven to assess the validity of tools measuring food safety/insecurity and provide valid indications and suggestions to policymakers.

In the 2000 Plan for Action regarding food and diet in Europe, the World Health Organization (WHO) argued that nutrition security in the 21st century depends on production that meets dietary needs and enables equal access to appropriate food while controlling misleading promotional messages (Carlson et al. 1999 ). In addition, food prices, policies, and education can significantly reduce malnutrition risks (Wekerle 2004 ).

Even though rising poverty and hunger levels have been a concern for many countries, acknowledgment and quantification of hunger have been disputed and hindered by the lack of an accepted definition and measure of food security. Before food security can be measured, the potential target of the intervention must be identified.

The first food security measure based on household experiences at the individual level was developed in 1990 by Radimer and colleagues ( 1992 ) and based on a 12-item questionnaire. The ‘hunger index’ was developed through qualitative interviews with women from low-income households (Kendall, Olson, and Frongillo 1995 ). Since 1992, the literature has indicated that food security measurements may vary in their performance across different population groups and cultures and that good practice and policy instruments are difficult to transfer across different contexts (Kendall, Olson, and Frongillo 1995 ; Leyna et al. 2008 ; Radimer and Radimer 2002 ; Zerafati Shoae et al. 2007 ). One of the main problems in rolling out food security interventions is that it is not easy to identify the target (households below the poverty line) (Carlson et al. 1999 ). Although such identification usually lacks accuracy, generalized subsidies (food stamps) – on commodities consumed by both the rich and the poor – have often been an attractive option for policymakers (Besley and Kanbur 1988 ).

The more recent Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES), developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), focuses on food consumption experience, living conditions, and individual contexts (Cafiero et al. 2018 ). It consists of eight dimensions regarding people’s access to adequate food, and it is based on various kinds of population surveys. Its global reference scale is based on results from the application of the FIES survey module in countries covered by the Gallup World Poll in 2014, 2015, and 2016. In addition, food insecurity prevalence rates allow comparison between different countries, and the FIES is designed to measure unobservable traits such as aptitude/intelligence, personality, and a broad range of social psychology- and health-related conditions (Cafiero et al. 2018 ).

The food security issue has gained greater cross-cutting relevance in academic and policy circles in connection to public health issues related to the economic and social crises raised by the COVID-19 pandemic (Ahn and Norwood 2020 ; Arouna et al. 2020 ; Béné 2020 ; Cable et al. 2021 ; Mishra and Rampal 2020 ; Moseley and Battersby 2020 ; O’Hara and Toussaint 2021). Economic and social stresses generated by the pandemic led to the formulation of renewed public interventions in response to food insecurity in developing and rich countries.

The literature review presented in the following sections aims to fill a gap in our knowledge of the vast amount of scientific food security research produced, its theoretical and research dimensions, and trends in the last twenty years. Furthermore, the fully electronic search intends to illustrate the main lines of scientific interest within the topic and indicate the most transversal issues and promising areas of scientific interaction. Therefore, this article is organized as follows.

Section 2 illustrates the research questions and methods adopted to build the dataset of articles addressing food security. Section 3 presents research results regarding publications over time and across scientific areas. Section 4 describes the most recurrent topics and clusters of issues addressed by the food security literature. Section 5 shows their inter-relations and evolution over time. Section 6 presents an in-depth analysis of the thematic cluster on domestic programs. Section 7 shows the impact of COVID-19 in the thematic focus of publications. Finally, Section 8 discusses the main findings and limits of the meta-analysis and evaluates the contribution of the food security literature to unlocking the future research potential of transboundary policies and governance.

2 Research questions and methods

This article aims to answer the three main research questions: in a systematic literature review, what are the main thematic dimensions linked to the issue of food security? How do these dimensions evolve, and how do they relate? Furthermore, does the literature highlight new dimensions of the problem concerning the COVID-19 pandemic?

To achieve its scope, this article combines bibliographic analysis, semi-automatic content analysis, and topic detection to explore the literature on food security. Following research domain analysis (RDA), applied to all publications in a given research domain (Janssen 2007 ; Janssen et al. 2006 ; Janssen and Ostrom 2006 ), we describe multiple strands of literature, in particular interdisciplinary and inter-sectoral ones, to highlight dimensions and research agendas linked to the food security theme. An overview of the scholarly production and its evolution is essential to account for its achievements and gaps and identify the way forward.

There is not a comprehensive literature review on food security so far, but only partial reviews (Candel 2014 ; Chan et al. 2006 ; Haddad et al. 1996 ; Nosratabadi et al. 2020 ; Thompson et al. 2010 ). Therefore, our objective is to conduct an exploratory literature review investigating the multidisciplinary approaches to the issue. Thus, when choosing the most appropriate data source to construct the database of articles, the comprehensiveness of content coverage was the most important criterion to evaluate. Bibliographic databases (DBs) are the leading providers of publication metadata and bibliometric indicators (Pranckute 2021 ). Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) are widely acknowledged as the two most comprehensive DBs (see Pranckute 2021 for a comprehensive review of the studies). However, multiple studies confirmed that Scopus has a more comprehensive overall coverage than WoS. In addition, while the content of the two databases is generally overlapping, Scopus indexes a more significant number of unique sources not covered by WoS, though this variation differs across specific subject fields (Pranckute 2021 ). Hence, we deemed Scopus the most appropriate data source for our literature review given its greater comprehensiveness.

To conduct our bibliometric analysis, we started by compiling a list of words and concepts related to food security based on seminal works in the literature and the authors’ knowledge of the topic. The list included the following terms: food security, food insecurity, food aid, food poverty, nutrition quality, food solidarity, and food stamps. Subsequently, we compiled a list of possible combinations of these terms using Boolean operators, and we used them as search strings to explore the title, abstract, or keywords of publications within the Scopus database. The choice of “food security” (in quotation marks) as a keyword resulted from an iterative process that involved multiple searches using all the compiled combinations and discussions among the authors. As a result, this keyword returned the highest number of articles (over 20,000 results, as opposed to less than 10,000 results for other combinations). Moreover, the articles citing the term “food security” also covered all the other terms and combinations, while the reverse was not valid. Hence, we verified that the concept of “food security” is the most comprehensive and that it contains other relevant frames, such as food poverty, nutrition poverty, and, to a lesser extent, food safety.

Due to the database consistency and the marked increase in the number of articles per year, we decided to focus on literature published during the last two decades, thus analyzing the articles produced between 2000 and 2020. Furthermore, we decided to analyze separately the literature published between January and July 2021 (the current year) to avoid a misinterpretation of the results. The 2021 literature is relevant for identifying a variation in themes and focuses after the COVID-19 pandemic.

A first search using the selected keywords returned 34,931 documents. To narrow the analysis, we decided to focus the search on peer-reviewed articles written in English, as they constitute the core of the international literature. In addition, we cleaned the resulting database by removing articles with no abstract and duplicates. To select which duplicate would be kept in the database, we respected the following criteria: the most recent, the longest abstract, and correct formatting. The final database contained 21,574 articles. For the first fundamental analysis of the database, we used the automatic analyses provided by Scopus and complemented them with analyses made through Microsoft Excel. The aim was to list the academic journals, countries, and scientific areas of the articles published.

The second step of the analysis focused on the thematic dimensions covered in the food security literature. We performed a topic detection on the articles’ abstracts to achieve this aim, using automatic content analysis. Automatic and semi-automatic content analyses are evolving trends in the literature. These methods exploit algorithms and software to apply statistical analysis to textual data in electronic format (Sbalchiero 2018 ). They automate the process of data encoding and analysis, thus combining the advantage of timesaving with the possibility to investigate the main topics and issues discussed in the literature without any prior theoretical or analytical constraints (Sbalchiero and Eder 2020 ; Righettini and Lizzi 2021 ). However, while their application to the analysis of social media and political documents is growing, they remain marginal in literature reviews. Still, this kind of analysis allows researchers to overcome the biases involved in literature reviews when the authors select and analyze articles. In many cases, the selection criteria for the articles are not specified, so there is a risk that essential studies will be left out, and a self-reinforcing mechanism will be perpetuated around a limited number of articles. Conversely, the automatic and semi-automatic analysis considers the whole body of literature, thus allowing researchers to explore the variety of theoretical frameworks and methodologies that unravel undetected patterns.

Topic detection is a text mining technique that allows detecting these patterns in large document corpora and classifying them as recurring topics and themes. The “latent” topics within the corpus’ documents are unveiled through algorithms that use statistical modeling and programming language to analyze the correlation among terms, i.e., words or phrases (El-Taliawi et al. 2021 ). This study employs Reinert’s method (Reinert 1990 , 2001 ), which uses the R-based software Iramuteq to analyze “the co-occurrences of words as they appear in portions of text, and thereby identify lexical worlds, or semantic classes” (Sbalchiero 2018 , p. 202). This method automatically performs most of the operations required to prepare the corpora (lemmatization, spelling harmonization, etc.). It allows for saving time in the process and increasing precision. Moreover, it does not require specifying the number of topics a priori (Sbalchiero and Eder 2020 ). Thus, it appears more fitted for explorative analysis of the literature we aim to do in this study.

The algorithm implemented by Iramuteq constructs a contingency matrix of words-per-abstract based on the co-occurrences of words in each abstract. It then uses a clustering procedure that hierarchically identifies the “factors (clusters) that best represent a lexical world from the distance of the chi-square between the classes” (Sbalchiero 2018 , p. 203). Pearson’s chi-square test (statistical hypothesis test) allows measuring the strength of association between the terms and topics. The greater the Pearson’s chi-square, the more likely the hypothesis of dependence between terms and topic (Carvalho et al. 2020 ). Co-occurrences of words are analyzed in such a way as to understand their relationships in the contexts of scientific discourse and to construct vocabularies of co-occurring words that are specific to each semantic class. Through this analysis, we were able to identify the different thematic dimensions discussed in the literature and the topics covered, and the relationships among different clusters. This analysis allowed us to answer the first research question.

In a subsequent step, we used the semi-automatic text analysis to measure the association grade between the topics and publication year variable. Again, a positive difference, and a threshold of significance set at chi-square, indicated that a topic had received greater attention in a particular year. Hence, by looking at the grade of association between year and clusters, we were able to determine the evolution of the topics over time and, thus, answer the second research question.

To strengthen these analyses, we also studied the keywords authors had listed in the articles. The keywords analysis helped identify the most studied issues related to food security and geographic focuses.

Finally, we investigated the articles published in Scopus between January 2021 and July 11, 2021 (the last search conducted) using the same procedure applied to the main corpus. After the cleaning procedure, the 2021 database consisted of 2,533 articles (out of 3,672 documents resulting from the search). As for the main corpus, we performed the analysis using both Microsoft Excel and Iramuteq software. However, in this case, the application of Reinert’s ( 1983 ) method did not result in a statistically significant analysis, as the percentage of text segments retained (69.16%) was lower than the minimum retention indicated by the literature (70 – 75%). Still, it was possible to use the analysis to identify new topics and trends in the literature on food security after the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the analysis of the keywords complemented this analysis and allowed us to answer the third research question.

Due to the high number of articles included in the dataset, this review did not aim to investigate the specific content of articles. Instead, it aimed to identify the main trends in the literature and the topics that constitute the core of the theoretical and methodological debate around food security.

3 Publications over time and across scientific areas

The present section describes some characteristics of the dataset analyzed, namely the corpus dimension, science areas, and journals most interested in food security, as well as how food security articles published between 2000 and 2020 developed over time.

Table 1 shows a first analysis of the database on food security. Between 2000 and 2020, 21,574 articles were published in English in 3,817 different journals. The high number of both articles and journals is representative of the attention that this topic has received over the last two decades and the multiple angles adopted for its analysis. The multidisciplinary of the literature is also evident in the distribution among different scientific areas. Agricultural and biological science (ABS) is the most prominent subject area, closely followed by social sciences (SS) and environmental science (ES). An important percentage of articles also deals with medicine and health (MH) and economics (E). Therefore, we can affirm that the issue of food security cuts across disciplinary boundaries. Authors have analyzed the issue from a variety of theoretical and methodological perspectives.

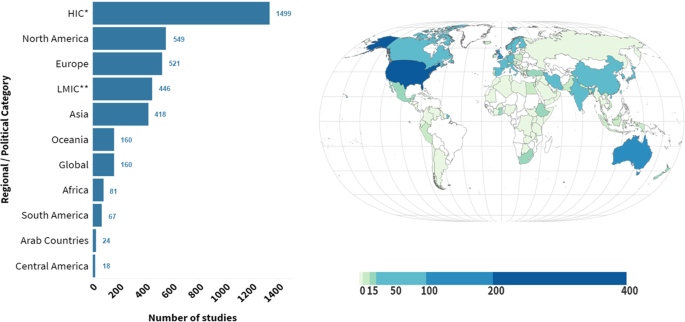

It is also worth noting that geographically, the publications are mainly concentrated in the Anglo-Saxon countries, with U.S. academia producing almost 30% of the literature. Other than the obvious issue of the English language, the strong preponderance of articles published by British and U.S. universities can be linked to the long tradition of these countries in food security and food assistance programs and evaluation. The automatic analyses performed by the Scopus website allowed us to identify the most relevant scientific areas explored in each country. Both the USA and UK distribute their production rather evenly among different scientific areas (USA: 18.3% ABS, 17.7% SS, 14.9% ES, 13.3% MH; UK: 21.4% ABS, 18.9% ES, 18.5% SS).

China represents an exception to the English-speaking countries, being the third most prolific producer. China has seen a rapid increase in articles published since 2009, with more than half of the studies focusing on ES and ABS. This timing in Chinese scientific production may be due both to the first major food security policy document released by the Chinese central government in 2004 to combat food poverty (Ghose 2014 ) and the effects of the global food crisis after the global increase in food prices in 2007. The instability was due to smaller amounts of food being available for human consumption because farmers devoted more of their crops to biofuel production in the USA and Europe (Bohstedt 2016 ).

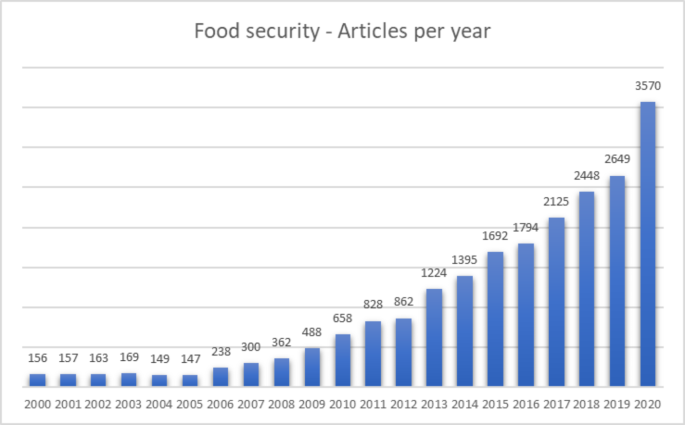

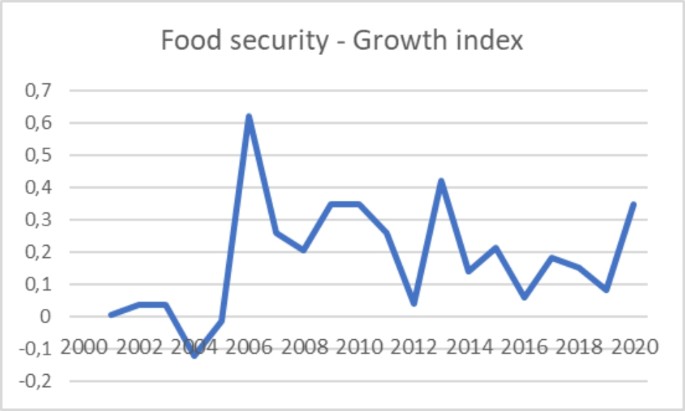

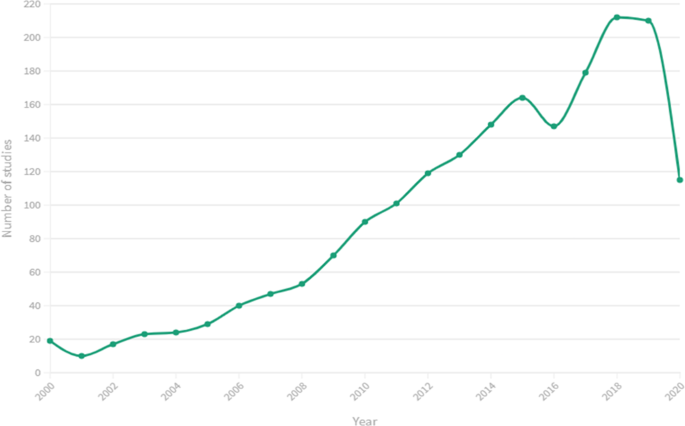

As shown in Fig. 1 , the number of articles published every year has strongly and steadily increased since the beginning of the century, with rapid growth in the last decade. The number of publications grew from 156 to 2,000 to 658 in 2010 to over 3,500 in 2020. The growth index represented in Fig. 2 (calculated as [(PresentValue – Past Value)/PastValue] *100) shows more clearly a substantial increase in 2006 (global food crisis) and two peaks in 2013 (effects of the second financial crisis) and 2020 (COVID-19 crisis). These figures show how the food security issue has been gaining importance in the literature over time, a trend confirmed by the number of articles published in 2021. In addition, they confirm the critical link between economic and social crises and food security. These crises increase food insecurity, thus sparking new debates and studies on the issue of food security.

Articles on food security published per year (2000–2020)

Yearly growth index of articles on food security (2000–2020)

The attention to food security observed in Fig. 2 gained momentum due to a sharp rise in alimentary prices in 2006 and 2013. The first rise was caused by global financial speculation in agricultural commodities futures (McKeon 2014 ). Moreover, the food crisis that broke out between 2007 and 2008 focused the interest of a broad international scientific debate on agricultural policies, the gaps between the north and the southern countries, and the adequacy of global food security governance’s primary tool: food aids. The second momentum of interest for food insecurity was in 2013. It converges with the new rise in food prices and a growing interest in the social movements and civil society organizations’ role in mitigating the social and health consequences of financial speculation and global food market dynamics on local communities. Finally, from 2019 onwards, the scientific literature has increased interest in the connections between the unstoppable growth of food prices, climate change, and the COVID-19 pandemic on food security. The scientific articles concern, among the others, the challenges posed by climate change on the resilience of local agricultural systems, and finally, the negative impact of policies to combat the COVID-19 pandemic on poverty and the growing fragility of individuals and families in accessing quality food both in developed and developing countries and regions.

As observed in Section 2 , the issue of food security results in many different journals and from various perspectives. The plurality of approaches to the problem is also evident in ranking the journals that have published the most articles. As we can see in Table 2 , the ten most active journals publish literature which is either interdisciplinary or pertaining to different scientific areas. It is interesting to observe that the first journal is Sustainability , thus reflecting the strong link between the issue of food security and sustainability, in particular with regard to the environmental and social aspects of the latter. In addition, food security has a dedicated journal, thus confirming once again its importance in the academic world.

4 Food security thematic dimensions

After mapping publications on food security, we can observe the empirical data that allow us to answer the first research question:

RQ1: What are the main thematic dimensions linked to the theme of food security?

A first attempt to identify the most recurrent issues analyzed by the food security literature can be made by looking at the keywords proposed by the authors, which outline the focus of the articles. As we can see from Table 3 , the focus proposed by the keywords is rather composite. The presence of climate change as the second most frequently used keyword is significant of the importance that adaptation (n. 13), resilience to climate change (n. 15), and the sustainability (n. 6) of food systems play in the academic discourse. Food production, represented by words such as agriculture (n. 4), rice (n. 11), and maize (n. 16), is also an important element of food security. It is also important to note the countries that appear as keywords and, thus, represent the main geographical focuses of the literature. The African continent is represented by three keywords: Africa (n. 8), sub-Saharan Africa (n. 12), and Ethiopia (n. 14). The strong presence of Africa in the literature can be linked to both the problem of food security in the continent and the FAO’s strong focus on the region. It is also interesting to observe that China (n.9) is the first country to appear as a keyword. This finding is in line with the fact that China is among the most prolific publishers and among the most studied countries, alongside Africa and India.

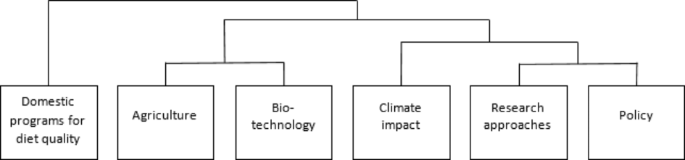

After a first analysis of the most discussed topics in the literature, we proceed to the analysis of the thematic clusters. The application of Reinert’s ( 1983 ) method to the corpus of food security articles resulted in a division into six thematic clusters that represent six different focuses of the literature. As shown in Fig. 3 , the division into clusters follows a hierarchical procedure which divides the texts based on their semantic classes, until the homogeneity of the texts makes a further division impossible. Hence, we can observe a first cluster (domestic programs for diet) isolated from a second macro-cluster that unfolds in three separate sub-clusters (agriculture and biotechnology; research approaches and policy; climate impact).

Descending hierarchy of thematic clusters in the food security literature (2000–2020)

Table 4 shows the percentage of texts that belong to each cluster and the words that best characterize it. The titles were assigned to each cluster by the authors based on the analysis of the content, to simplify their identification.

Below is a short description of the content of each cluster and its perspective on food security:

Cluster 1: “Domestic programs for diet quality” is the biggest thematic cluster in the literature. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 3 , this cluster stands as a separate stream of the literature. It deals with food security programs and diet quality, linking food security to household food security. It focuses on programs designed to secure a good dietary intake, with a specific focus on low-income Footnote 1 families, gender ( woman, female) , and schools . The American Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) receives considerable attention within this cluster, as one of the oldest and broadest national food security programs. Hence, food security is analyzed in its dimension related to nutritional quality ( nutritional status, dietary diversity) , observing the impact of different factors ( income, education, age) on food insecurity at the individual level. The measurement of food insecurity is central in this cluster, as highlighted by words such as survey, score, questionnaire , and interview . Through these methods, the literature aims to measure the impact of food security programs in contrasting food insecurity and improving the nutritional status of the participants. Due to its size and its separateness from the rest of the literature, we analyze this cluster in greater depth in the next section.

Cluster 2: “Agriculture” focuses specifically on agricultural production, investigating the influence of different factors on food production. Specifically, it observes the impact of climatic events ( temperature, season, rainfall ) and agricultural practices ( fertilizers, manure, experiment) on the yield productivity of different crops ( maize, wheat, rice, grains). The approach to food security in this cluster is purely scientific, and it aims to increase and improve food production to guarantee access to food.

Cluster 3: “Bio-technology” is closely related to Cluster 4, as it deals with the genetic and biological aspects of food and its production. The analysis focuses on the genetic modification of plants and species to improve their resistance and tolerance to pathogens and external stress. The approach is purely scientific, and it focuses on improving the resistance of food production to the impact of climate change.

Cluster 4: “Climate impact” relates to a dimension of global demand for food production , mostly related to the impact of climate change and population growth . Agricultural production is essential for ensuring food security and global access to food. However, it is facing challenges on two fronts. On the one hand, it needs to deal with the impact of climate change and how it threatens productivity, biodiversity , and water resources. On the other, it is challenged by changes in land use , both under the pressure of urbanization and about land conversion for producing energy , in the form of biofuel. Thus, this cluster focuses on improving food security through the adoption of strategies that mainly aim to strengthen the resilience, productivity, and sustainability of food production.

Cluster 5: “Research approaches” is a rather composite cluster which includes the different frameworks and perspectives adopted by the food security literature. The approaches and methodologies are very diverse, ranging from political discussions and debates (agenda, discourse) , to social and justice perspectives ( movement, human rights) , to food systems and food sovereignty ( governance). It uses both empirical case studies and theoretical approaches ( theory) to discuss the issue and concept of food security. The diversity of approaches reflects the multidisciplinarity of the literature, as previously observed.

Cluster 6: “Policy” deals with the strategies and policies that governments adopt for food security and adaptation . Agricultural policies are central in this cluster, with natural resources and land management as essential elements of adaptation strategies and farmers’ support. The cluster analyses all phases involved in the policy process, examining the definition of an agenda , the decision-making process, the planning of a strategy , the identification of tools , and the adoption phase, which includes the implementation, strengthening , and building of capacities. Participatory practices, as well as technology and innovation , receive much attention within the cluster. Thus, this cluster focuses on the improvement of food security through the adoption of strategies that mainly aim at strengthening the resilience, productivity, and sustainability of food production.

It is interesting to observe the role “poverty” plays in the food security literature. While it is one of the most used keywords listed by authors, it does not appear as a frequent word in any clusters (Cluster 2 is the one in which it first appears, n. 223). This difference in importance could be that while poverty is considered a central issue in the food security literature, the articles focus on the causes, effects, and different dimensions of poverty, rather than on poverty itself. Causes and effects are treated in different clusters within the literature. Cluster 2 deals with climate change’s impact on the increasing number of people falling into poverty globally. Cluster 6 and, to a lesser extent, Cluster 5 deal with its effects through programs that aim to alleviate food and nutrition poverty.

5 Evolution over time and relation between thematic dimensions

After the analysis of the thematic clusters and their evolution over time, we can answer the second research question:

RQ2: How do these dimensions evolve, and how do they relate?

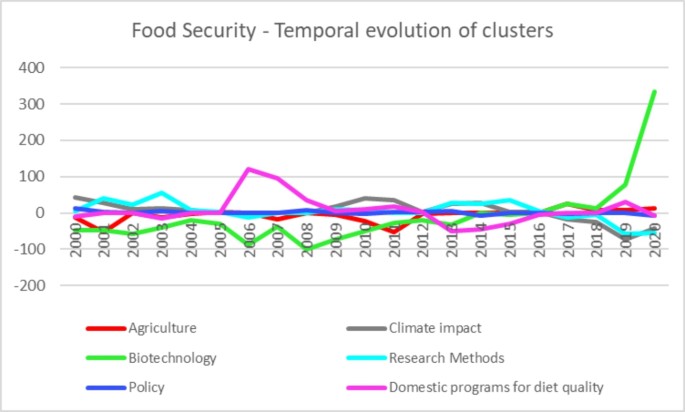

Figure 4 shows the evolution over time of the different thematic clusters. We can see a relatively stable trend in the evolution of the clusters.

Refer to Sect. 2 for the general meaning of the chi-square value. In the temporal evolution of topics, Pearson’s chi-square indicates the association between the term “year_year of publication” (e.g., “year_2020”) related to each article and the topics. A positive value in the graph suggests over-representation of a topic in a specific year (highly discussed in the literature), while negative values indicate under-representation of the topic in that year (seldomly discussed in the literature)

Figure compiled by authors .

Still, we can observe how the “biotechnology” cluster has started to receive increased attention in the past five years, with a growing trend. Likewise, the “domestic programs for diet quality” cluster saw a spike in attention between 2006 and 2007. This increase is likely to be linked to the global food crisis caused by a shift in land use, from food production for human consumption to biomass production for biofuel. The drop-in food production caused a spike in the prices and a consequent increase in food insecurity, thus putting programs to improve food security high on the policy and scholarly agenda.

The food security literature has seen multiple topics co-exist in the last two decades. The “policy” cluster has had the most stable presence in the literature, while other clusters have seen fluctuating trends. It is worth noting that the “diet quality” cluster received considerable attention in 2006 – 2007 and that a growing strand of literature focuses on the technological and biological aspects of food production for food security.

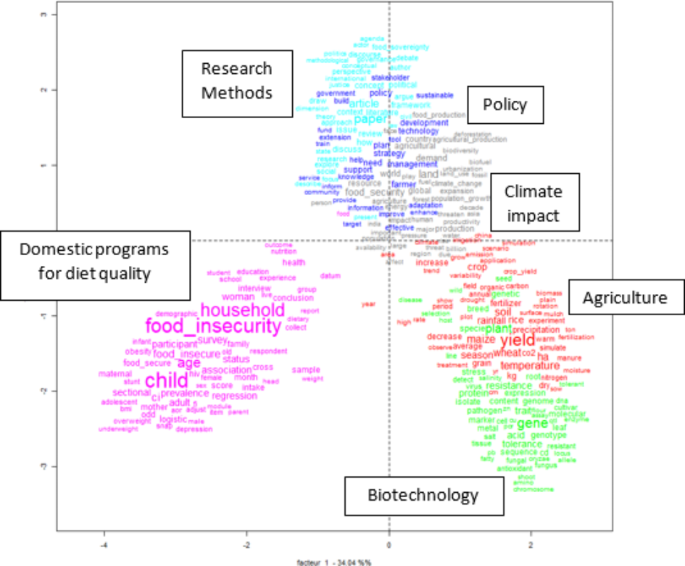

The Cartesian planes (Fig. 5 ) reflect the relationships between different clusters and among the most frequent words belonging to the clusters themselves. The zero value on the X-axis allows for distinguishing between topics that show a positive correlation among terms and topics that tend to be more isolated. Clusters with a higher co-occurrence appear graphically close, while graphically distant clusters are treated as separate issues in the literature. Moreover, words used most frequently within a cluster appear more prominent in the graph.

Distance and interconnections between thematic clusters related to food security (2000–2020)

As already observed in the descending hierarchy of the cluster (Fig. 3), the six clusters can be grouped into three macro-clusters. The cluster “diet quality programs” stands alone, with little integration with the other clusters. The “agriculture” and “biotechnology” clusters form a macro-cluster dealing with food production. The articles about this macro-cluster focus on improving agricultural production, increasing its resistance to the changing climate, and guaranteeing food security in a world with a fast-growing population. The third macro-cluster includes the methodological aspects and combines the thematic dimension with the impact of global warming. The articles in the macro-cluster, then, focus on the policies that have been implemented to face the challenges proposed by climate change, mainly concerning land management and strategies to prevent and adapt to climate change. The second and third macro-clusters show similarities, but while the second one adopts a techno-biological perspective on the issue, the third employs a socioeconomic perspective.

Hence, the thematic dimensions that can be identified in the food security literature comprise (a) domestic programs to tackle food insecurity; (b) policies to fight the challenges posed to global food security by climate change; and (c) analysis and technological improvements in food production to guarantee global food security.

6 Domestic programs for diet quality: an in-depth analysis

It is interesting to observe Cluster 6 in greater depth, as it represents a consistent part of the literature and a stand-alone cluster. To better understand its content, we applied Reinert’s ( 1983 ) analysis method to its sub-corpus of text segments. The analysis showed a division into five clusters, two dedicated to methodologies and three dedicated to an analytical dimension.

The methodological clusters show a clear division between qualitative methods, which focus on nutrition security (i.e., dietary diversity) at the individual level, and quantitative ones, which deal with food security (i.e., access to food and poverty) at a more macro level. The qualitative methods, which represent the majority, present a solid link to interviews and participatory approaches and a temporal dimension (name of months), highlighting that attention is given to developing countries and the impact of seasonal cycles on agricultural production. Conversely, the quantitative methods investigate the statistical correlation among different phenomena (e.g., food security and obesity) at the macro, and national level.

The analytical clusters unfold into two different streams in the literature: one develops methodological strategies and techniques, and the other devises in-depth substantive analyses of the issue of food security. The first stream of articles analyses how to measure food security and which instruments to assess its causes and effects ought to be used, including the comparative approach. The second stream adopts a policy approach that aims to answer how to intervene by considering food insecurity programs organizational and institutional contexts. Intervention strategies are defined by analyzing of food security’s risk factors, which can be semantically attributed to a health dimension (i.e., obesity, diseases, and mental health), and a behavioral and social dimension (i.e., purchasing habits, income, and education). These two dimensions are discussed together within the literature, showing how they are intrinsically connected in determining food security.

The relevance of the methodological dimension and the attention to risk factors confirm the importance of developing appropriate tools to measure food security, both in terms of causes and effects, to design more appropriate food security programs.

7 New thematic dimensions in the aftermath of COVID-19

The global COVID-19 pandemic has had a consistent impact, from a socioeconomic standpoint and on academic production. Consequently, the COVID-19 impacts (direct and indirect) on the global and local scale increased scholars’ engagement and attention. Hence, it is interesting to analyze the 2021 literature on food security to observe whether the crisis has impacted academic production on the issue and new thematic dimensions have emerged.

Thus, we can answer our third research question:

RQ 3: What new dimensions of the issue do the literature highlight concerning the COVID-19 pandemic?

The articles published in 2021 provide us insights into the COVID-19 impact on the issue of food security and whether the pandemic caused a change in focus in the literature.

In the first six months of 2021, 2,533 food security articles were published in 977 journals. The 2021 data also confirm the saliency of the topic and its multidisciplinary. However, while ABS remains the central area of focus (21.9%), we observed increased attention paid to ES (19%) and a decrease in focus on SS (13.8%). This result is in line with the growing trend in the cluster that deals with biotechnological aspects of food security and emerged by the journals publishing the highest number of articles on food security in 2021. Four out of five of the most active journals deal with ES ( Sustainability , International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , Science of the Total Environment , and Journal of Cleaner Production ). However, it is more likely that these trends are linked to the increased scholarly and public attention paid to climate change. In addition, China has confirmed its importance as a publisher of food security literature.

COVID-19 appears as the fourth most frequent keyword proposed by the authors, after food security, food insecurity, and climate change. This result shows how COVID-19 has become the focus of many articles. Still, climate change remains a more substantial concern for academics dealing with food security, as highlighted by the subject areas and journals.

Reinert’s ( 1983 ) analysis method can better enlighten the impact of COVID-19 on the literature, showing how the topic is treated in articles and how the clusters have changed in the aftermath of the pandemic. Although the disappearance of the methodological cluster, the thematic clusters of 2021 present many similarities with those of the period 2000 – 2020. However, we observe significant differences in topics within the “policy” and “climate impact” clusters. While the 2000 – 2020 “policy” cluster focused on support policies for agricultural adaptation to climate change, the 2021 “policy” cluster has a stronger focus on sustainability policies, with governments seeming to have more importance and the social and environmental dimension being more directly debated. In addition, the 2000 – 2020 “climate impact” cluster became broader in 2021, including different global challenges.

On the one hand, we saw attention paid to the COVID-19 pandemic. On the other, we saw a switch in attention from agriculture to fishery, as an essential source of food for the global population that is currently under threat due to climate change and unsustainable fishing practices. In addition, a warming planet has disrupted and depleted fisheries worldwide, drawing scientific attention to overfishing as a factor increasing the vulnerability of fisheries.

In terms of relations among the different thematic clusters, we can observe that the “bio-technology” cluster has become more separate from the “agriculture” cluster, while the latter has become more closely linked to the “policy” and “climate impact” clusters. The closer link between food production and the global political dimension may be due to the increased public and political attention paid to the issue of climate change, as well as the growing impact of extreme climate events on food production.

Moreover, we observed that the “domestic programs for diet quality” cluster remains an isolated theme in the literature, confirming the silo approach to food insecurity on a domestic scale and the global issue of food production for a growing population and in a warming planet.

8 Discussion and conclusions

The systematic literature analysis addressed by the current article increases our knowledge of the vast and multidisciplinary food security scientific production and its theoretical and research dimensions and trends during the last twenty years. Furthermore, it traces the main lines of scientific interest in the topic and indicates the most transversal issues, weaknesses, and opportunities for future development.

In the period considered, food security becomes increasingly relevant in conjunction with and due to the impact of the economic and financial crises and climate change on the weakest segments of the population, both in developing and rich countries.

The main literature trends highlighted by our research can be summarized as follows:

The number of articles published has increased enormously in the last two decades, with peaks in 2006, 2013, and 2020, all linked to the outbreak of financial and social crises and their effects on agricultural commodities prices and food system dynamics. The place of the issue of food security within the literature has grown in importance over time. This is because it has become sensitive to the increasingly frequent global economic and health crises (Dodds et al. 2020 ; Galanakis 2020 ; O’Hara and Toussaint 2021 ) and the local environmental impact of climate change (Bohle et al. 1994 ; Lang et al. 2009 ).

Domestic programs for diet quality are the most explored dimension of food security and stand as a separate branch of the literature, considerably ahead of the most discussed macro-dimension of food production, which addresses policies, climate impact, and agriculture.

Despite a relatively stable trend in the evolution of the main topics detected, we can observe how the “biotechnology” cluster has started to receive increased attention in the past five years.

The general scientific attention to the “diet quality” issue was highly concentrated in 2006–2007, along with a growing strand of literature focused on the technological and biological aspect of food production for food security.

The household food security measurement and indicators are the most important scientific topics and, at the same time, separate from other arguments addressed by scholars. This separation indicates the difficulty of theoretically and empirically linking the micro nutritional aspects of food security to meso and macro elements, such as government agricultural policy and climatic impact on local diet change. Thus, even though food security is widely recognized as a multidimensional and cross-sectoral issue, academic analyses still seem affected by silo approaches in one of the most important fields of scientific analysis and public intervention.