Enable JavaScript and refresh the page to view the Center for Hellenic Studies website.

See how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

- Current Residential Fellows

- Previous Fellows

- Library Visitor Policies

- Research Guides

- Seminars and Workshops

- Current Exhibits

- Student Opportunities

- Faculty Programs

- Introduction to Online Publications

- Primary Texts

- Research Bulletin

- Prospective Authors

- Community Values

Fellowships

- Fellowships in Hellenic Studies

- Early Career Fellowships

- Summer Fellowships

- CHS-IHR Joint Fellowship

- Previous Fellows Previous Fellows – Chronological Lists

The Library

- Publications Articles Books Prospective Authors Primary Texts Serials

Old Norse Mythology—Comparative Perspectives

Citation: Hermann, Pernille, Stephen A. Mitchell, and Jens Peter Schjødt, eds., with Amber J. Rose. 2017. Old Norse Mythology—Comparative Perspectives . Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature 3. Cambridge, MA: Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_HermannP_etal_eds.Old_Norse_Mythology.2017 .

Methodological Challenges to the Study of Old Norse Myths: The Orality and Literacy Debate Reframed

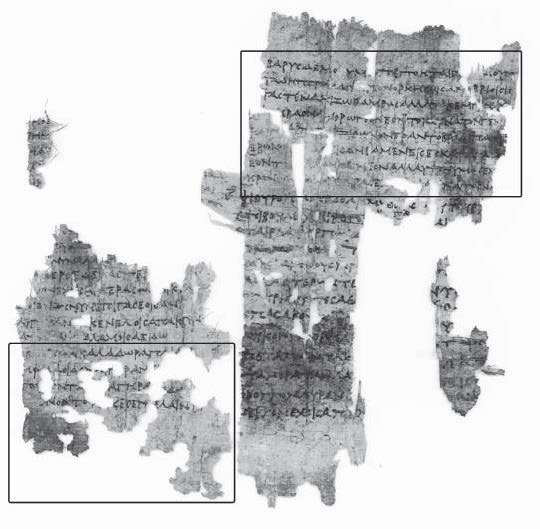

Source evaluation, oral-derived texts.

The resigned conclusion of this passage about the elusory character of eddic poems may very well be an implication of a lack of methodological concern and of a textually-biased view of the texts. Implicit to the questions of age and provenance are text-bound ideas of “works” as finalized textual units, and ideas about the possibility of exact dating and arranging the poems in chronological order are organizing principles that are not readily adaptable to oral texts nor, most likely, to oral-derived texts.

Text-Context

Parallel with an increased awareness of “performance” and “living orality”, it becomes relevant not merely to reconstruct the myths themselves, but also to recontextualize them. Thus, in acknowledging that in an oral situation, meaning emerges as much from the context as from the text itself, it becomes increasingly important to scrutinize in which ways it is possible to recontextualize the myths.

However, some new pathways have been laid out (see Jochens 1993), implying that dichotomizing tendencies that have otherwise been dominant, say, between genres like history and fiction (Clunies Ross 1998; Hermann 2010) or between pagan traits and Christian influence (Lönnroth 1969; Vésteinn Ólason 1998), are not as firm as they may appear. For instance, Jürg Glauser has proposed that less focus on genre distinctions, that is, on textual classification and chronology, as well as an increased focus on alternative “concepts of text” (Glauser 2000a, 2007) may break down classifications that otherwise have guided our understanding of the source value of the texts. Studies in saga-texts increasingly turn attention to the number of ways in which these texts are discursively indebted to cultural, historical, and ideological forces at the time of each text witness, as well as to the reception of texts (Quinn and Lethbridge 2010). In having other foci than those literary approaches that emphasize author, literary borrowings, and the question of origins, future studies that follow up on such pathways may very likely bring to light new aspects of the textual material, aspects that will also inspire the study of myths in context.

Myth performance

Books with non-ecclesiastical content were also read aloud in front of audiences. It has long been emphasized, and it is generally accepted, that this was the case for saga-texts; and it has been argued as well that eddic poems were intended to be read out loud and possibly even to be acted dramatically (Lönnroth 1979; Mitchell 1991; Gunnell 1995a, 1995b; Mundal 2010). This argument shows that when transferred to written form, the narrative material was potentially realized and received in a context that retained dimensions that otherwise confine themselves to oral situations. This observation thus locates the written texts in multi-media and multidimensional situations, where books and visible signs on the page would have been accompanied by such features as voice and bodily orientation.

Words and images

Diachronic and synchronic approaches

Works cited, primary sources, secondary sources.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Ph.D. Thesis: Asgard Revisited. Old Norse Mythology and Icelandic National Culture 1820-1918

Related Papers

Ólöf Pétursdóttir

A reflexion on the evolution of Old Norse to what we call Modern Icelandic, astonishingly close to the former.

Aurelijus Vijūnas

Historiographia Linguistica

Giovanni Verri , Matteo Tarsi

This article presents two essays by the renowned Icelandic manuscript collector Árni Magnússon (1663‒1730): De gothicæ lingvæ nomine [On the expression ‘the Gothic language’] and Annotationes aliqvot de lingvis et migrationibus gentium septentrionalium [Some notes on the languages and migrations of the northern peoples]. The two essays are here edited and published in their original language, Latin. Moreover, an English translation is also presented for ease of access. After a short introduction ( § 1 ), a historical overview of the academic strife between Denmark and Sweden is given ( § 2 ). Subsequently ( § 3 ), Árni Magnússon’s life and work are presented. In the following Section ( § 4 ), the manuscript containing the two essays, AM 436 4to, is described. The two essays are then edited and translated in Section 5 . In the last Section ( § 6 ), the two works are commented and Árni Magnússon’s scholarly thought evaluated.

Ég Víkingur

Acta Scientific Agriculture

João Vicente Ganzarolli de Oliveira

Guðvarður Már Gunnlaugsson

Anja Ute Blode

Programme for the 4th International Conference for East Norse Philology June 2019

Katie Thorn

Scandinavian Philology

Anatoly Liberman

Viking Language 2: The Old Norse Reader

Jesse Byock

Viking Language 2: The Old Norse Reader immerses the learner in the legends, folklore, and myths of the Vikings. The readings are drawn from sagas, runes and eddas. They take the student into the world of Old Norse heroes, gods, and goddesses. There is a separate chapter on the ‘Creation of the World’ and another on ‘The Battle at the World’s End,’ where the gods meet their doom. Other readings and maps focus on Viking Age Iceland, Greenland, and Vínland. A series of chapters tackles eddic and skaldic verse with their ancient stories from the old Scandinavian past. Runic inscriptions and explanations of how to read runes form a major component of the book. Where there are exercises, the answers are given at the end of the chapter. Both Viking Language 1 and 2 are structured as workbooks. Students learns quickly and interactively. More information on our website: vikinglanguage.com

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Íslenskt mál og almenn málfræði

Matteo Tarsi

Lyonel Perabo

Václav Blažek

Mediaevistik: Internationale Zeitschrift für …

Daniel Sävborg

Jeffrey Turco

Rein Amundsen

Chad Laidlaw

Íslendingabók and the Birth of the Icelandic culture

Nicolas Jaramillo

Gottskálk Jensson

Michael Knudson

Jeffrey Turco , Joseph C Harris , Thomas D Hill , Richard L Harris , Russell Poole , Paul Acker , Torfi Tulinius

Miscellanea Geographica – Regional Studies on Development

Tatjana Jackson

Philip Lavender

Wiley-Blackwell

Stephen Pax Leonard

Studia Linguistica

Richard Demers , James E Cathey

Linguistic Institute, University of Iceland, Reykjavik

Eiríkur Rögnvaldsson

in Northern Myths, Modern Identities, ed. Simon Halink (Leiden: Brill)

Gylfi Gunnlaugsson

Oxford Handbooks in Archaeology

Davide Zori

New Norse Studies: Essays on the Literature and Culture of Medieval Scandinavia

The Linguistic Review

Charles Reiss

Arkiv för Nordisk Filologi

Takahiro Narikawa

Old Norse-Icelandic Literature

Heather O'Donoghue

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Norse Mythology for Smart People

Our current knowledge of the pre-Christian mythology and religion of the Norse and other Germanic peoples has been painstakingly pieced together from a large assortment of sources over the past few centuries.

The most significant category among these sources is without a doubt the literature concerning mythological and historical subjects written in the Old Norse language from about 800 to 1400 CE, a span that includes the epochs we now refer to as the Viking Age and the Medieval Period. The Scandinavians and Icelanders held onto their traditional religion far longer than the more southerly Germanic peoples, and the Icelanders in particular did a remarkable job of preserving their heathen lore long after Christianity became the island’s official religion in 1000 CE. Were it not for the body of poems, treatises, and sagas that they’ve handed down to us, the pre-Christian worldview of the Germanic peoples would now be almost entirely lost.

The Poetic Edda

Old Norse-speaking poets have left us countless valuable clues regarding their religious perspective, but the collection of poems known today as the “Poetic Edda” or “Elder Edda” contains the most mythologically rich and thorough of these. Two of these poems, Völuspá (“The Insight of the Seeress”) and Grímnismál (“The Song of the Hooded One”) are the closest things we have to systematic accounts of the pre-Christian Norse cosmology and mythology.

The name “Edda” has been retroactively applied to this set of poems and is a reference to the Edda of Snorri Sturluson (see below). The authors of the poems are all anonymous. Debates have raged over the dates and locations of the poems’ composition; all we can really be certain about is that, due to the fact that some of the poems are obviously written in a manner that places them in dialogue with Christian ideas (especially the aforementioned Völuspá ), the poems must have been composed sometime between the tenth and thirteenth centuries, when Iceland and Scandinavia were being gradually Christianized.

The Poetic Edda is likely the single most important of all of our sources.

The Prose Edda

Among the prose Old Norse sources, the Prose Edda , or simply the “Edda,” contains the greatest quantity of information concerning our topic. This treatise on Norse poetics was written in the thirteenth century by the Icelandic scholar and politician Snorri Sturluson, long after Christianity had become the official religion of Iceland and the old perception of the world and its attendant practices had long been fading into ever more distant memory. The etymology and meaning of the title “Edda” have puzzled scholars, and none of the explanations offered so far have gained any particularly widespread acceptance.

Snorri made use of the poems in the Poetic Edda, but added to his account a considerable amount of information that can’t be found in those poems. In some cases he quotes from other poems that have been lost over the course of the centuries, but in other cases he offers nothing but his naked assertions. Some of these can be confirmed by other sources, and many of his uncorroborated claims are in keeping with the general worldview he describes, which makes scholars more inclined to accept them. Others of these assertions, however, appear to be simple rationalizations, attempts to reconcile the old mythos with Christianity, or other sorts of fabrications. Modern readers of Snorri have advanced widely differing appraisals of the value of his work.

While it would be rash to simply dismiss everything in the Prose Edda that the earlier poems haven’t already told us, it would be equally presumptuous to accept every statement of Snorri’s at face value. Unfortunately, the latter approach was common throughout much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and as a result most popular introductions to Norse mythology uncritically rehash Snorri’s contentions and thereby present a skewed portrait of the old gods and tales.

Even though their definition of “history,” or at least what constitutes a reliable piece of historical information, might diverge considerably from our present understanding, the Icelanders of the Middle Ages have left us with numerous historical texts that add mightily to our knowledge of pre-Christian Norse religious traditions. While many of these, such as the priest Ari Thorgilsson’s Íslendingabók (“Book of Icelanders”) and the anonymous Landnámabók (“Book of Settlements”), don’t fit into the saga genre, the majority of these historical works are Icelandic sagas.

The sagas were written primarily in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and recount the lives of famous Icelanders, Scandinavian kings, and Germanic folk heroes. Their literary style is as stark as the landscape of Iceland; events are described in a terse, matter-of-fact way that leaves much to the imagination and intuition. When elements of pre-Christian religion are mentioned, it’s almost invariably casually and in passing, as opposed to the more direct manner of Snorri and the poets. The most notable exception to this is the first several chapters of the Saga of the Ynglings , which give a thorough exposition of the character and deeds of many of the Norse deities, albeit in a euhemerized (trying to rationalize mythology by casting it as an exaggerated account of ordinary historical events) context. This same technique is used in the Prose Edda , which should be unsurprising, since the Saga of the Ynglings and the collection of sagas to which it belongs, the Heimskringla or History of the Kings of Norway , were also written by Snorri. Virtually all of the other sagas, however, are anonymous.

Other Sources

Indispensable as it is, Old Norse literature isn’t our only source of information concerning the pre-Christian religion of the Germanic peoples.

The Danish scholar Saxo Grammaticus wrote a Latin history of the Danes ( Gesta Danorum , The History of the Danes ) in the twelfth century that includes variants of many of the tales found in the Old Norse sources and even a few otherwise unattested ones. As with Snorri, these are presented in a highly euhemerized form.

Late in the first century CE, the Roman historian Tacitus wrote a book on the Germanic tribes who dwelt north of the Empire. This work, De origine et situ Germanorum , “The Origin and Situation of the Germanic Peoples,” commonly referred to simply as Germania , contains many vivid descriptions of the religious views and practices of the tribes.

The literature of the Anglo-Saxons, another branch of the Germanic family, contains several mythological parallels to some of the narratives and themes dealt with in the Old Norse sources. The epic poem Beowulf is the most significant Old English source, and the Latin work Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (“The Ecclesiastical History of the English People”) by the eighth century monk Bede contains numerous pieces of information concerning the pre-Christian religious traditions of the Anglo-Saxons.

The continental Germans have also bequeathed to us accounts of their heathen traditions such as those found in the so-called Merseburg Charms, which are medieval prayers or spells composed in Old High German, and the Middle High German epic poem Nibelungenlied .

Medieval law codes from the Germanic countries are another valuable source; many of them describe, or at least reference, particular animistic folk traditions in the process of outlawing them for being “pagan” and “abominable.”

Archaeology is the most significant of our non-literary sources. A plenitude of archaeological finds have provided striking corroborations of elements from the written sources, as well as offering new data that can’t necessarily be explained by the written sources, reminding us of how incomplete a picture the literary sources contain.

The study of place-names has also yielded valuable evidence. Many sites throughout the Germanic lands are named after heathen deities, often combined with words that indicate a sacral significance such as “temple” or “grove.” This allows us to trace the popularity of devotion to specific deities across space and time, and often yields additional clues about the gods’ personalities and attributes, as well as those of their worshipers.

Finally, the study of comparative religion has illuminated our understanding of the pre-Christian religion of the Germanic peoples by intelligently filling in some of the gaps in our other sources by connecting the known themes, figures, and tales from the Germanic peoples with those of other, related peoples. For example, esteemed historian of religion Georges Dumézil has shown how the Germanic myths are in many ways representative of much older Indo-European models, and others such as Mircea Eliade and Neil Price have analyzed the profound similarities between Norse shamanism and that of other circumpolar and Eurasian societies.

The Present State of Our Knowledge

Based on the above, you might be tempted to think that we currently have a very full picture of heathen Germanic mythology and religion. But such is certainly not the case. As I try to make clear in various articles on this site, the knowledge provided to us on these topics by our sources is actually very fragmentary. We do, of course, know many things about the ancient Germanic religion, but there are also gaps in our knowledge that sometimes seem as vast as Ginnungagap itself. To fill in these lacunae, we can avail ourselves of the time-honored techniques of informed guesswork and intuition, but there will always be frayed and broken threads that dangle tantalizingly at the outer edges of our knowledge, reminding us of the missing pieces that might still be available to us today were it not for the intervening centuries of the more or less malign neglect of that information.

Looking for more great information on Norse mythology and religion? While this site provides the ultimate online introduction to the topic, my book The Viking Spirit provides the ultimate introduction to Norse mythology and religion period . I’ve also written a popular list of The 10 Best Norse Mythology Books , which you’ll probably find helpful in your pursuit.

The Ultimate Online Guide to Norse Mythology and Religion

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Abstract: In pointing to a theme of importance for source evaluation, this essay gives an overview of the study of Old Norse myths from the perspective of the orality/literacy debate. It seeks to provide a picture of emerging tendencies and directions in scholarship.

This collection of eight essays plus an overview of contemporary research on Old Norse mythology includes papers presented at a symposium at the University of Aarhus in 2005, and then...

Consisting of more than 70 papers written by scholars concerned with pre-Christian Norse religion, the articles discuss subjects such as archaeology, art histor...

It owes its awareness to its history, geography and geopolitical position and mythology. In our study, we would like to state the role of mythology as a cultural identity through the samples of the Phrygian mythology.

The objective and outcome of the paper are to explore the Norse community in the Nordic region, and t heir relationship with continental Europe (E.U.), through documentary analysis of its ...

The starting point of this research comprises a close reading of Georges Dumézil’s system of understanding myth, followed by an analysis of Jerold C. Frakes’s attempt to explain the position of Loki in Norse mythology and religion.

The paper here focuses on the association of the Scandinavian imaginary with specific moments in A. S. Byatt’s personal history, and highlights the use of certain patterns and ideas that are ...

The paper provides a brief summary of the Old Norse Grettis Saga and examines it in terms of research aspects outside of the field of literary studies. It highlights the historical, cultural, social, and religious contexts of the work, giving explanation as to where indications of them can be found in the saga.

A reflexion on the evolution of Old Norse to what we call Modern Icelandic, astonishingly close to the former. Download Free PDF View PDF Byock, Jesse L.: Viking Language 1: Learn Old Norse, Runes, and Icelandic Sagas

Our current knowledge of the pre-Christian mythology and religion of the Norse and other Germanic peoples has been painstakingly pieced together from a large assortment of sources over the past few centuries.