Radical Feminism: Definition, Theory & Examples

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Radical feminism is a perspective within feminism that calls for a radical reordering of society in order to eliminate patriarchy, which it sees as fundamental to the oppression of women. It analyses the role of the sex and gender systems in the systemic oppression of women and argues that the eradication of patriarchy is necessary to liberate women.

Key Takeaways

- Radical feminists believe that men are the enemy and that marriage and family are the key institutions that allow patriarchy to exist.

- For radical feminists in order for equality to be achieved patriarchy needs to be overturned. They argue that the family needs to be abolished and a system of gender separatism needs to be instituted for this to happen.

- Sommerville argues that radical feminists fail to see the improvements that have been made to women’s experiences of the family. With better access to divorce and control over their fertility women are no longer trapped by family. She also argues that separatism is unobtainable due to heterosexual attraction.

What Is Radical Feminism?

Radical feminism is a branch of feminism that seeks to dismantle the traditional patriarchal power and gender roles that keep women oppressed.

Radical feminists believe that the cause of gender inequality is based on men’s need or desire to control women. The definition of the word ‘radical’ means ‘of or relating to the root’.

Radical feminists thus see patriarchy as the root cause of inequality between men and women and they seek to up-root this. They aim to address the root causes of oppression through systemic change and activism, rather than through legislative or economic change.

Radical feminism requires a global change of the system. Radical feminists theorize new ways to think and apprehend the relationships between men and women so that women can be liberated.

Radical feminism sees women as a collective group that has been and is still being oppressed by men. Its intent is focused on being women-centered, with women’s experiences and interests being at the forefront of the theory and practice. It is argued by some to be the only theory by and for women (Rowland & Klein, 1996).

What Are The Principles Of Radical Feminism?

Below are some of the key areas of focus which are essential to understanding radical feminism:

Patriarchal institutions

Radical feminists believe that there are existing political, social, and other institutions that are inherently tied to the patriarchy.

This can include government laws and legislature which restricts what women can do with their bodies, and the church, which has long restricted women to the maternal role, and rejects the idea of non-reproductive sexuality.

Traditional marriage is also defined as a patriarchal institution according to radical feminists since it makes women part of men’s private property.

Even today, marriage can be seen as an institution perpetuating inequalities through unpaid domestic work, most of which is still done by women.

Control over women’s bodies

According to radical feminists, patriarchal systems attempt to gain control over women’s bodies. Patriarchal institutions control the laws of reproduction where they determine whether women have the right to an abortion and contraception.

Thus, women have less autonomy over their own bodies. Kathleen Barry stated in her book Female Sexual Slavery (1979) that women in marriage are seen to be ‘owned’ by their husband.

She also suggested that women’s bodies are used in advertising and pornography alike for the male use.

Women are objectified

From a radical feminist standpoint, the patriarchy, societal sexism, sexual violence, and sex work all contribute to the objectification of women.

They accuse pornography of objectifying and degrading women, displaying unequal male-female power relations. With prostitution, radical feminists argue that it trivializes rape in return for payment and that prostitutes are sexually exploited.

The struggle against pornography has come to occupy such a central position in the radical feminist critique of male supremacist relations of power.

Campaigns against this are intended to tell women how men are willingly being trained to view and objectify them (Thompson, 2001).

Violence against women

Radical feminists believe that women experience violence by men physically and sexually, but also through prostitution and pornography.

They believe that violence is a way for men to gain control, dominate, and perpetuate women’s subordination. According to radical feminists, violence against women is not down to a few perpetrators, but it is a wider, societal problem.

They claim there is a rape culture that is enabled and encouraged by a patriarchal society.

Transgender disagreement

There is disagreement about transgender identity in the radical feminist community. While some radical feminists support the rights of transgender people, some are against the existence of transgender individuals, especially transgender women.

Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists (TERF) are members of the radical feminist community who do not acknowledge that transgender women are real women and often want to exclude them from ‘women-only’ groups.

For this reason, TERFs often reduce gender down to biological sex differences and do not support the rights of all those who identify as being a woman.

What Are The Goals Of Radical Feminism?

Structural change.

Radical feminists aim to dismantle the entire system of patriarchy, rather than adjust the existing system through legal or social efforts, which they claim does not go far enough.

They desire this structural change since they argue that women’s oppression is systemic, meaning it is produced by how society functions and is found in all institutions.

They believe that institutions including the government and religion are centered historically in patriarchal power and thus need to be dismantled.

They also criticize motherhood, marriage, the nuclear family , and sexuality, questioning how much culture is based on patriarchal assumptions. They would like to see changes in how these other institutions function.

Bodily autonomy

Radical feminists emphasize the theme of the body, specifically on the reappropriation of the body by women, as well as on the freedom of choice. They want to reclaim their bodies and choose to be able to do what they want with their bodies.

They have argued for reproductive rights for women which would give them the freedom to make choices about whether they want to give birth.

This also includes having access to safe abortions, birth control, and getting sterilized if this is what a woman wants to do.

End violence against women

Radical feminists aim to shed light on the disproportionate amount of violence that women face at the hands of men. They argue that rape and sexual abuse are an expression of patriarchal power and must be stopped.

Through dismantling the patriarchy and having justice for victims of violence on the basis of sex, radical feminists believe there will be less instances of this violence.

Many also argue that pornography and other types of sex work are harmful and encourage violence and domination of men over women and should be stopped. They believe that sex work falls under the patriarchal oppression of women and is exploitative, although some radical feminists disagree with this position.

Women-centered strategies

A main part of radical feminism is that they want strategies to be put in place to help women. This can include the creation of shelters for abused women and better sex education to raise awareness of consent.

Many radical feminists strive for establishing women-centered social institutions and women-only organizations so that women are separated from men who may cause them harm.

For instance, they may be against having gender neutral public bathrooms as this increases women’s risk of being abused by a man.

This is also where TERFs can be critical of transgender people as they do not want them in women-only spaces since they do not see a transwoman as a woman.

The History Of Radical Feminism

Radical feminism mainly developed during the second wave of feminism from the 1960s onwards, primarily in Western countries. It is influenced by left-wing social movements such as the civil rights movement.

It is thought to have been constructed in opposition to other feminist movements at the time: Liberal and Marxist feminism. Liberal feminism only demanded equal rights within the system of society and is criticized for not going far enough to make actual change.

Marxist feminism , on the other hand, confined itself to an economic analysis of women’s oppression and believed that women’s liberation comes from abolishing capitalism.

Although becoming popularized in the 1960’s there are believed to be radical feminists decades before this time.

For example, some of the actions of the women in the women’s suffrage movement in the early 20th century can be considered radical.

Likewise, a 1911 radical feminist review in England titled The Free Woman published weekly writings about revolutionary ideas about women, marriage, politics, prostitution, sexual relations, and issues concerning women’s oppression and strategies for ending it.

It was eventually banned by booksellers and many suffragists at the time objected to it because of its critical position on the right to vote as the single issue which would ensure women’s equality (Rowland & Klein, 1996).

Radical feminism as a movement is thought to have emerged in 1968 as a response to deeper understandings of women’s oppression (Atkinson, 2014). The early years of second wave feminism were marked by the efforts of young radical feminists to establish an identity for their growing movement.

They argued that women needed to engage in a revolutionary movement which goes beyond liberal and Marxist movements.

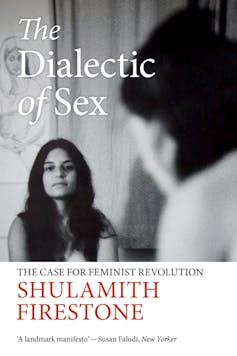

A significant radical feminist group which emerged around this time is the New York Radical Women group, founded by Shulamith Firestone and Pam Allen.

They attempted to spread the message that ‘sisterhood is powerful’. A well-known protest of this group occurred during the Miss America Pageant in 1968.

Hundreds of women marched with signs proclaiming that the pageant was a ‘cattle auction’. During the live broadcast of this event, the women displayed a banner that read ‘Women’s Liberation’, which brought a great deal of public awareness of the radical feminist movement.

A noteworthy writing prior to this time which may have been influential to the movement is Simone de Beauvoir’s 1949 book titled The Second Sex .

In this book, she understands women’s oppression by analyzing the particular institutions which define women’s lives, such as marriage, family, and motherhood.

Another influential writing is Betty Friedan’s 1963 book titled The Feminine Mystique which addresses women’s dissatisfaction with societal standards and expectations.

Her book gave a voice to women’s frustrations with their limited gender roles and helped to spark widespread activism for gender equality.

Strengths And Criticisms Of Radical Feminism

Radical feminism is thought to expand on earlier branches of feminism since it seeks to understand and dismantle the roots of women’s oppression. It is considered stronger than liberal feminism which only seeks to make changes within the already established system, which is considered not enough to make actual change.

Radical feminism has also been responsible for many of the advances made during the second wave of feminism . This is particularly true when it comes to women’s choice over their bodies and violence against women.

Due to the activism of radical feminists, sexual violence such as rape and domestic violence are now considered crimes in most Western countries.

It has also been recognized that violence against women is not a series of isolated cases, but rather a societal phenomenon. Radical feminists have thus increased awareness of this issue.

A prominent criticism of radical feminism is the transphobia associated with TERFs. Many people who relate to a lot of the original ideas of radical feminism may have stopped identifying as a radical feminist due to its association with TERFs.

It is not only transphobic but is part of a wider movement which encompasses its feminist stance to partner with conservatives, with a goal to endanger and get rid of transgender people.

While radical feminism may have been progressive during its peak, the movement can be criticized for lacking an intersectional lens. It views gender as the most important axis of oppression and sees women as a homogenous group collectively oppressed by men.

It does not always take into consideration the different experiences of oppression suffered by women with disabilities, women of color, or migrant women for instance.

As with a lot of branches of feminism, radical feminism is often dominated by white women. Radical feminists are often criticized for their paradoxical views of bodily autonomy.

They promote freedom of choice when it comes to women and what they do with their bodies, but they do not support women who choose to engage in sex work. They argue that all sex workers are oppressed, without recognizing that a good number of them use this work to reappropriate their own bodies or even to play on male domination.

The critical view that radical feminists have about sex work has contributed to the further stigmatization of this industry and it contradicts their message of ‘my body, my choice’ and their opposition to conservative views of sexuality.

If they supported bodily autonomy, then they should be happy to see a woman choosing to engage in sex work, as long as this is what she is choosing to do.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are there different types of radical feminists.

According to Rosemarie Tong (2003), there are two types of radical feminism: libertarian and cultural.Radical libertarian feminists assert that an exclusively feminine gender identity limits a woman’s development, so they encourage women to become androgynous, who embody both masculine and feminine characteristics.

Radical cultural feminists argue that women should be strictly female and feminine and should not try to be like men. However, not all radical feminists fit into one of these categories.

What are radical feminists’ views on crime?

Radical feminists recognize that there is a disproportionate amount of violence against women, including domestic abuse. In the 1970’s radical feminists labored to reform the public’s response to crimes such as rape and domestic violence.

Before the revision of policies and laws, rape victims were often blamed for their victimization. Due to the help of radical feminists, there is more justice for victims of gender-based violence.

What are radical feminists’ views on the family?

Adrienne Rich (1980) analyzed the compulsory nature of heterosexuality and claims that men fear that women could be indifferent to them and only allow them emotional and economic access on their own terms.

She suggests that the compulsory nature of heterosexual relationships allows men access to women as natural and their right. The family is considered to be an institution, which starts off with marriage and a legal contract where the reproduction of children naturally follows.

Many radical feminists may engage in political lesbianism, refuse to marry, and remain child-free as a way to not feel tied down by patriarchal institutions.

Atkinson, T. G. (2014). The Descent from Radical Feminism to Postmodernism. In presentation at the conference “ A Revolutionary Moment: Women’s Liberation in the Late 1960s and the Early 1970s,” Boston University.

Barry, K. (1979). Female sexual slavery . NyU Press.

Cottais, C. (2020). Radical Feminism. Gender in Geopolitics Institute. Retrieved 2022, August 19, from: https://igg-geo.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Technical-Sheet-Radical-feminism.pdf

De Beauvoir, S. (2010). The second sex . Knopf.

Friedan, B. (2010). The feminine mystique . WW Norton & Company.

Greer, G. (1971). The female eunuch .

Greer, G. (2007). The whole woman . Random House.

Nachescu, V. (2009). Radical feminism and the nation: History and space in the political imagination of second-wave feminism. Journal for the Study of Radicalism, 3 (1), 29-59.

Rich, A. (1980). Compulsory heterosexuality and lesbian existence. Signs: Journal of women in culture and society, 5 (4), 631-660.

Rowland, R., & Klein, R. (1996). Radical feminism: History, politics, action. Radically speaking: Feminism reclaimed , 9-36.

Thompson, D. (2001). Radical feminism today . Sage.

Tong, R., & Botts, T. F. (2003). Radical Feminism. Encyclopedia of Feminist Theories . London: Routledge.

Related Articles

Latour’s Actor Network Theory

Cultural Lag: 10 Examples & Easy Definition

Value Free in Sociology

Cultural Capital Theory Of Pierre Bourdieu

Pierre Bourdieu & Habitus (Sociology): Definition & Examples

Two-Step Flow Theory Of Media Communication

ROBERT JENSEN

VIEW ARTICLES BY YEAR 2024 2023 2022 2021 2020 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 1994 1993 1992 1991

Getting Radical: Feminism, Patriarchy, and the Sexual-Exploitation Industries

By Robert Jensen

Published in Dignity: A Journal of Sexual Exploitation and Violence · March, 2021

Begin with the body.

In an analysis of pornography and prostitution in a patriarchal society, it’s crucial not to lose sight of basic biology. A coherent feminist analysis of the ideology and practice of patriarchy starts with human bodies.

We are all Homo sapiens. Genus Homo, species sapiens. We are primates. We are mammals. We are part of the animal kingdom.

We are organic entities, carbon-based creatures of flesh and blood. Whatever one thinks about the concepts of soul and mind—and I assume that in any diverse group there will be widely varying ideas—we are animals, which means we are bodies. The kind of animal that we are reproduces sexually, the interaction of bodies that are either male or female (with a very small percentage of people born intersex, who have anomalies that may complicate reproductive status).

Every one of us—and every human who has ever lived—is the product of the union of an egg produced by a female human and a sperm produced by a male human. Although it also can be accomplished with technology, in the vast majority of cases the fertilization of an egg by a sperm happens through the act of sexual intercourse, which in addition to its role in reproduction is potentially pleasurable.

I emphasize these elementary facts not to reduce the rich complexity of human interaction to a story about nothing but bodies, but if we are to understand sex/gender politics, we can’t ignore our bodies. That may seem self-evident, but some postmodern-inflected theories that float through some academic spaces, intellectual salons, and political movements these days seem to have detached from that reality.

If we take evolutionary biology seriously, we should recognize the centrality of reproduction to all living things and the importance of sexuality to a species that reproduces sexually, such as Homo sapiens. Reproduction and sexuality involve our bodies.

Female and male are stable biological categories. If they weren’t, we wouldn’t be here. But femininity and masculinity are not stable social categories. Ideas about what male and female mean—what meaning we attach to those differences in our bodies—vary from culture to culture and change over time.

That brings us to patriarchy, radical feminism, a radical feminist critique of the sexual-exploitation industries in patriarchy, and why all of this is important, not only for women but for men. I’m here as a man to make a pitch to men: Radical feminism is especially important for us.

Patriarchy Patriarchy—an idea about sex differences that institutionalizes male dominance throughout a society—has a history. Though many assume that humans have always lived with male dominance, such systems became widespread only a few thousand years ago, coming after the invention of agriculture and a dramatic shift in humans’ relationship with the larger living world. Historian Gerda Lerner argues that patriarchy began when “men discovered how to turn ‘difference’ into dominance” and “laid the ideological foundation for all systems of hierarchy, inequality, and exploitation” (Lerner, 1997, p. 133). Patriarchy takes different forms depending on time and place, but it reserves for men most of the power in the institutions of society and limits women’s access to such power. However, Lerner reminds us, “It does not imply that women are either totally powerless or totally deprived of rights, influence and resources” (Lerner, 1986, p. 239). The world is complicated, but we identify patterns to help us understand that complexity.

Patriarchy is not the only hierarchal system that enhances the power of some and limits the life chances of others—it exists alongside white supremacy, legally enforced or informal; various unjust and inhumane economic systems, including capitalism; and imperialism and colonialism, including the past 500 years of exploitation primarily by Europe and its offshoots such as the United States.

Because of those systems, all women do not have the same experience in patriarchy, but the pattern of women’s relative disadvantage vis-à-vis men is clear. As historian Judith Bennett writes, “Almost every girl born today will face more constraints and restrictions than will be encountered by a boy who is born today into the same social circumstances as that girl.” (Bennett, 2006, p. 10).

Over thousands of years, patriarchal societies have developed justifications, both theological and secular, to maintain this inequality and make it seem to be common sense, “just the way the world is.” Patriarchy has proved tenacious, at times conceding to challenges but blocking women from reaching full equality to men. Women’s status can change over time, and there are differences in status accorded to women depending on other variables. But Bennett argues that these ups and downs have not transformed women as a group in relationship to men—societies operate within a “patriarchal equilibrium,” in which only privileged men can lay claim to that full humanity, defined as the ability to develop fully their human potential (Bennett, 2009). Men with less privilege must settle for less, and some will even be accorded less status than some women (especially men who lack race and/or class privilege). But in this kind of dynamically stable system of power, women are never safe and can always be made “less than,” especially by men willing to wield threats, coercion, and violence.

Although all the systems based on domination cause immense suffering and are difficult to dislodge, patriarchy has been part of human experience longer and is deeply woven into the fabric of everyday life. We should remember: White supremacy has never existed without patriarchy. Capitalism has never existed without patriarchy. Imperialism has never existed without patriarchy. From patriarchy’s claim that male domination and female subordination are natural and inevitable have emerged other illegitimate hierarchies that also rest on attempts to naturalize, and hence render invisible, other domination/subordination dynamics.

Radical Feminism Feminism, at its most basic, challenges patriarchy. However as with any human endeavor, including movements for social justice, there are different intellectual and political strands. What in the United States is typically called “second wave” feminism, that emerged out of the social ferment of the 1960s and ‘70s, produced competing frameworks: radical, Marxist, socialist, liberal, psychoanalytical, existential, postmodern, eco-feminist. When non-white women challenged the white character of early second-wave feminism, movements struggled to correct the distortions; some women of color choose to identify as womanist rather than feminist. Radical lesbian feminists challenged the overwhelmingly heterosexual character of liberal feminism, and different feminisms went in varying directions as other challenges arose concerning every-thing from global politics to disability.

Since my first serious engagement with feminism in the late 1980s, I have found radical feminist analyses to be a source of inspiration. Radical feminism highlights men’s violence and coercion—rape, child sexual assault, domestic violence, sexual harassment—and the routine nature of this abuse for women, children, and vulnerable men in patriarchy. In patriarchal societies, men claim a right to own or control women’s reproductive power and women’s sexuality, with that threat of violence and coercion always in the background. In the harshest forms of patriarchy, men own wives and their children, and men can claim women’s bodies for sex constrained only by agreements with other men. In contemporary liberal societies, men’s dominance takes more subtle forms.

Radical feminism forces us to think about male and female bodies, about how men use, abuse, and exploit women in the realms of reproduction and sexuality. But in the contemporary United States, the radical approach has been eclipsed by the more common liberal (in mainstream politics) and postmodern (in academic and activist circles) strands of feminism. A liberal approach focuses on gaining equality for women within existing political, legal, and economic institutions. While notoriously difficult to define, postmodernism challenges the stability and coherence not only of existing institutions but of the very concepts that we use within them and tends to focus on language and performance as key to identity and experience. Liberalism and postmodernism come out of very different sets of assumptions but are similar in their practical commitment to individualism in politics, tending to evaluate a proposal based on whether it maximizes choices for individual women rather than whether it resists patriarchy’s hierarchy and challenges the power of men as a class. On issues such as pornography and prostitution, both liberal and postmodern feminism avoid or downplay a critique of the patriarchal system and reduce the issue to support for women’s choices, sometimes even claiming that women can be empowered through the sexual-exploitation industries.

Radical feminism’s ultimate goal is the end of patriarchy’s gender system, not merely expanding women’s choices within patriarchy. But radical feminism also recognizes the larger problem of hierarchy and the domination/subordination dynamics in other arenas of human life. While not sufficient by itself, the end of patriarchy is a necessary condition for liberation more generally.

Today there’s a broad consensus that any form of feminism must be “intersectional,” Kimberlé Crenshaw’s (1989) term to describe about how black women could be marginalized by movements for both racial and gender justice when their concerns did not conform to either group’s ideology or strategy. While the term is fairly new, the idea goes back further. For example, the statement of the Combahee River Collective, a group of black lesbian feminists in the late 1970s, named not only sexism and racism but also capitalism and imperialism as forces constraining their lives: [W]e are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives (Combahee River Collective, 2000, p. 264).

Intersectional approaches like these help us better understand the complex results of what radical feminists argue is a central feature of patriarchy: Men’s efforts to control women’s reproductive power and sexuality. As philosopher Marilyn Frye puts it: For females to be subordinated and subjugated to males on a global scale, and for males to organize themselves and each other as they do, billions of female individuals, virtually all who see life on this planet, must be reduced to a more-or-less willing toleration of subordination and servitude to men. The primary sites of this reduction are the sites of heterosexual relation and encounter—courtship and marriage-arrangement, romance, sexual liaisons, fucking, marriage, prostitution, the normative family, incest and child sexual assault. It is on this terrain of heterosexual connection that girls and women are habituated to abuse, insult, degradation, that girls are reduced to women—to wives, to whores, to mistresses, to sex slaves, to clerical workers and textile workers, to the mothers of men’s children (Frye, 1992, p. 130).

This analysis doesn’t suggest that every man treats every woman as a sex slave, of course. Each individual man in patriarchy is not at every moment actively engaged in the oppression of women, but men routinely act in ways that perpetuate patriarchy and harm women. It’s also true that patriarchy’s obsession with hierarchy, including a harsh system of ranking men, means that most men lose out in the game to acquire significant wealth and power. Complex systems produce complex results, and still there are identifiable patterns. Patriarchy is a system that delivers material benefits to men—unequally depending on men’s other attributes (such as race, class, sexual orientation, nationality, immigration status) and on men’s willingness to embrace, or at least adapt to, patriarchal values. But patriarchy constrains all women. The physical, psychological, and spiritual suffering endured by women varies widely, again depending on other attributes and sometimes just on the luck of the draw, but no woman escapes some level of that suffering. And at the core of that system is men’s assertion of a right to control women’s reproductive power and sexuality.

The Radical Feminist Critique of the Sexual-Exploitation Industries I use the term “sexual-exploitation industries” to include prostitution, pornography, stripping, massage parlors, escort services—all the ways that men routinely buy and sell objectified female bodies for sexual pleasure. Boys and vulnerable men are also exploited in these industries, but the majority of these businesses are about men buying women and girls.

Not all feminists or progressive people critique this exploitation, and in some feminist circles—especially those rooted in liberalism or postmodernism—so-called “sex work” is celebrated as empowering for women. Let’s start with simple questions for those who claim to want to end sexism and foster sex/gender justice: –Is it possible to imagine any society achieving a meaningful level of any kind of justice if people from one sex/gender class could be routinely bought and sold for sexual services by people from another sex/gender class? –Is justice possible when the most intimate spaces of the bodies of people in one group can be purchased by people in another group? –If our goal is to maintain stable, decent human societies defined by mutuality rather than dominance, do the sexual-exploitation industries foster or impede our efforts? –If we were creating a just society from the ground up, is it likely that anyone would say, “Let’s make sure that men have ready access to the bodies of women in commercial transactions”?

These questions are both moral and political. Radical feminists reject dominance, and the violence and coercion that comes with a domination/subordination dynamic, out of moral commitments to human dignity, solidarity, and equality. But nothing I’ve said is moralistic, in the sense of imposing a narrow, subjective conception of sexuality on others. Rejecting the sexual-exploitation industries isn’t about constraining people’s sexual expression, but rather is part of the struggle to create the conditions for meaningful sexual freedom.

So why is this radical feminist critique, which has proved so accurate in its assessment of the consequences of mainstreaming the commercial sex industry, so often denounced not only by men who embrace patriarchy but also by liberal and left men, and in recent years even by feminists in the liberal and postmodern camps?

Take the issue I know best, pornography. Starting in the 1970s, women such as Andrea Dworkin (2002) argued that the appeal of pornography was not just explicit sex but sex presented in the context of that domination/subordination dynamic. Since Dworkin’s articulation of that critique (1979), the abuse and exploitation of women in the industry has been more thoroughly documented. The content of pornography has become more overtly cruel and degrading to women and more overtly racist. Pornography’s role in promoting corrosive sexual practices, especially among young people, is more evident. As the power of the radical feminist critique has become clearer, why is the critique more marginalized today than when it was first articulated?

Part of the answer is that the radical feminist critique of pornography goes to the heart of the claim of men in patriarchy to own or control women’s sexuality. Feminism won some gains for women in public, such as more expansive access to education and a place in politics. But like any system of social control, patriarchy does not quietly accept change, pushing back against women’s struggle for sexual autonomy. Sociologist Kathleen Barry describes this process: [W]hen women achieve the potential for economic independence, men are threatened with loss of control over women as their legal and economic property in marriage. To regain control, patriarchal domination reconfigures around sex by producing a social and public condition of sexual sub-ordination that follows women into the public world (Barry, 1995, p. 53).

Why Should Men Care? Barry is not suggesting that men got together to plot such a strategy. Rather, it’s in the nature of patriarchy to respond to challenges to male power with new strategies. That’s how systems of illegitimate authority, including white supremacy and capitalism, have always operated.

Men can no longer claim outright ownership of women, as they once did. Men cannot always assert control over women using old tactics. But they can mark women as always available for men’s sexual pleasure. They can reduce women’s sexuality—and therefore can reduce women—to a commodity that can be bought and sold. They can try to regain an experience of power lost in the public realm in a more private arena.

This analysis challenges the liberal/postmodern individualist story that says women’s rights are enhanced when a society allows them to choose sex work. Almost every word in that sentence should be in scare-quotes, to mark the libertarian illusions on which the argument depends. I’m not suggesting that no woman in the sexual-exploitation industries ever makes a real choice but am merely pointing out the complexity of those choices, which typically are made under conditions of considerable constraint and reduced opportunities. And whatever the motivation of any one woman, the validation and normalization of the sexual-exploitation industries continues to reduce women and girls to objectified female bodies available to men for sexual pleasure.

If we men really believe in the values most of us claim to hold—dignity, solidarity, and equality—that is reason enough to embrace radical feminism. That’s the argument from justice. Radical feminists have shown how the sexual-exploitation industries harm women, children, and vulnerable men used in the industry. But if men need additional motivation, do it not only for women and girls. Do it for yourself. Recognize an argument from self-interest.

Radical feminism is essential for any man who wants to move beyond “being a man” in patriarchy and seeks to live the values of dignity, solidarity, and equality as fully as possible (Jensen, 2019). Radical feminism’s critique of masculinity in patriarchy is often assumed to be a challenge to men’s self-esteem but just the opposite is true—it’s essential for men’s self-esteem.

Consider a claim that men sometimes make when asked if they have ever used a woman being prostituted. “I’ve never had to pay for it,” a man will say, implying that he is skilled enough in procuring sex from women that money is unnecessary. In other situations, a man might brag about having sex with a woman being prostituted, especially if that woman is seen as a high-class “call girl” or is somehow “exotic,” or if the exploitation of women takes place in a male-bonding activity such as a bachelor party.

All these responses are patriarchal, and all reveal men’s fear of vulnerability and hence of intimacy. That’s why pornography is so popular. It offers men quick-and-easy sexual pleasure with no risk, no need to be a real person in the presence of another real person who might see through the sad chest-puffing pretense of masculinity in patriarchy.

One of the most common questions I get after public presentations from women is “why do men like pornography?” We can put aside the inane explanations designed to avoid the feminist challenge, such as “Men are just more sexual than women” or “Men are more stimulated visually than women.” I think the real answer is more disturbing: In patriarchy, men are often so intensely socialized to run from the vulnerability that comes with intimacy that they find comfort in the illusory control over women that pornography offers. Pornography may give men a sense of power over women temporarily, but it does not provide what men—what all people—need, which is human connection. The pornographers play on men’s fears—not a fear of women so much as a fear of facing the fragility of our lives in patriarchy.

When we assert masculinity in patriarchy—when we desperately try to “be a man”—we are valuing dominance over mutuality, choosing empty pleasure over intimacy, seeking control to avoid vulnerability. When we assert masculinity in patriarchy, we make the world more dangerous for women and children, and in the process deny ourselves the chance to be fully human.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This article draws on The End of Patriarchy: Radical Feminism for Men (Jensen, 2017). Special thanks to Renate Klein and Susan Hawthorne of Spinifex Press. An edited version of this article was recorded for presentation at the online Canadian Sexual Exploitation Summit hosted by Defend Dignity, May 6-7, 2021. Dignity thanks the following people for their time and expertise to review this article: Lisa Thompson, Vice President of Research and Education, National Center on Sexual Exploitation, USA; and Andrea Heinz, exited woman and activist, Canada.

RECOMMENDED CITATION Jensen, Robert. (2021). Getting radical: Feminism, patriarchy, and the sexual-exploitation industries. Dignity: A Journal of Sexual Exploitation and Violence. Vol. 6, Issue 2, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.23860/dignity.2021.06.02.06 Available at http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/dignity/vol6/iss2/6

REFERENCES Barry, Kathleen. (1995). The prostitution of sexuality. New York University Press. Bennett, Judith M. (2009, March 29). “History matters: The grand finale.” The Adventures of Notorious Ph.D., Girl Scholar. http://girlscholar.blogspot.com/2009/03/history-matters-grand-finale-guest-post.html Bennett, Judith M. (2006). History matters: Patriarchy and the challenge of feminism. University of Pennsylvania Press. Combahee River Collective. (2000). The Combahee River Collective statement. In Barbara Smith (Ed.), Home girls: A black feminist anthology (pp. 264-274). Rutgers University Press. Crenshaw, Kimberlé. (1989). “Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1, 139-167. Dworkin, Andrea. (2002). Heartbreak: The political memoir of a feminist militant. Basic Books. Dworkin, Andrea. (1979). Pornography: Men possessing women. Perigee. Frye, Marilyn. (1992). Willful virgin: Essays in feminism 1976-1992. Crossing Press. Jensen, Robert. (2019, fall). Radical feminism: A gift to men. Voice Male. https://voicemalemagazine.org/radical-feminism-a-gift-to-men/ Jensen, Robert. (2017). The end of patriarchy: Radical feminism for men. Spinifex. Lerner, Gerda (1997). Why history matters: Life and thought. Oxford University Press. Lerner, Gerda (1986). The creation of patriarchy. Oxford University Press.

View Articles by Topic

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Perspective

With the death of bell hooks, a generation of feminists lost a foundational figure.

Lisa B. Thompson

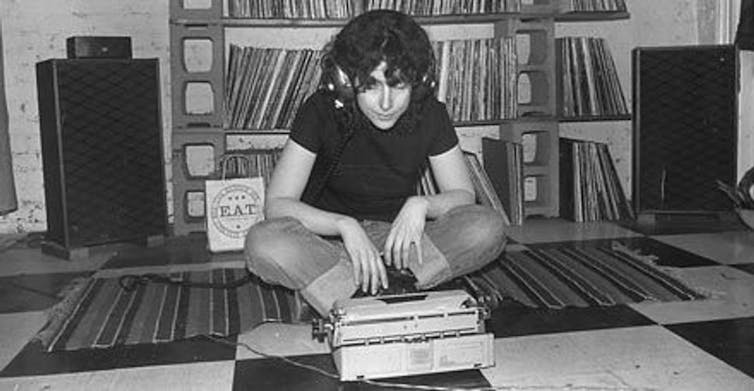

Author and cultural critic bell hooks poses for a portrait on December 16, 1996 in New York City, New York. Karjean Levine/Getty Images hide caption

Author and cultural critic bell hooks poses for a portrait on December 16, 1996 in New York City, New York.

"We black women who advocate feminist ideology, are pioneers. We are clearing a path for ourselves and our sisters. We hope that as they see us reach our goal – no longer victimized, no longer unrecognized, no longer afraid – they will take courage and follow." bell hooks, Ain't I a Woman

Arts & Life

Trailblazing feminist author, critic and activist bell hooks has died at 69.

There are well-worn bell hooks books scattered throughout my library. She's in nearly every section – race, class, film, cultural studies – and, as expected, her books take up an entire shelf in the feminism section. I doubt I would have survived this long without her work, and the work of other Black feminist thinkers of her generation, to guide me. I've retrieved every bell hooks book today, and the unwieldy stack comforts me as I assess the impact of her loss.

If you ever heard hooks speak, it would come as no surprise that she first attended college to study drama, as she recounted in a 1992 essay. In the 1990s she blessed my college campus for a week, and I was mesmerized by lectures that were deliciously brilliant yet full of humor. Her banter with the audience during the Q&A floated easily between thoughtful answers, deep questioning and sly quips that kept us at rapt attention. Her words garner just as much attention on the page. She was a prolific writer, and her intellectual curiosity was boundless.

Discovering bell hooks changed the lives of countless Black women and girls. After picking up one of her many titles – Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center; Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics; Ain't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism – the world suddenly made sense. She reordered the universe by boldly gifting us with the language and theories to understand who we were in an often hostile and alienating society.

She also made clear that, as Black women, we belonged to no one but ourselves. A bad feminist from the start, hooks was clearly uninterested in being safe, respectable or acceptable, and charted a career on her own terms. She implored us to transgress and struggle, but to do so with love and fearlessness. Her brave, bold and beautiful words not only spoke truth to power, but also risked speaking that same truth to and about our beloved icons and culture.

As we traversed hostile spaces in academia, corporate America, the arts, medicine and sometimes our own families, hooks not only taught us how to love ourselves, but also insisted that we seek justice. She helped us to better understand and, if necessary, forgive the women who birthed and raised us. She claimed feminism without apology, and encouraged Black women in particular to embrace feminism, and to do more than simply identify their oppression, but to envision new ways of being in the world. She called on us to honor early pioneers such as Anna Julia Cooper and Mary Church Terrell, who first claimed the mantle of women's rights.

The lower-case name bell hooks published under challenged a system of academic writing that historically belittled and ignored the work of Black scholars. She also used language that was as plain and as clear as her politics. While her writing was deeply personal, often carved from her own experiences, her ideas were relentlessly rigorous and full of citations—even though she eschewed footnotes, another refusal of the academy's standards that endeared her to those of us determined to remake intellectual traditions that denied our very humanity.

Rejecting footnotes seemed to symbolize the fact that the knowledge hooks most valued could not fit into those tiny spaces. Her writing style hinted at the fact that her ideas were always more expansive than even her books could hold. While there were no footnotes, her books were love notes to a people she loved fiercely.

No matter where she taught or lived, bell hooks always kept Kentucky and her family ties close. She frequently claimed her southern Black working-class background and an abiding love for her home. Although she was educated at prestigious schools, she always spoke with the wisdom and wit of our mothers, grandmothers and aunties. Her return to the Bluegrass State and Berea College towards the end of her career has a narrative elegance. A generation of feminists has lost a foundational figure and a beloved icon, but her legacy lives on in her writing, which will provide sustenance for generations to come.

Lisa B. Thompson is a playwright and the Bobby and Sherri Patton Professor of African & African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. Follow her @drlisabthompson on Twitter and Instagram .

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Liberal vs Radical Feminism Revisited

1994, Journal of Applied Philosophy

This essay considers the movement away from a feminism based upon liberal political principles, such as John Stuart Mill espoused, and towards a radical feminism which seeks to build upon more recent explorations of psychology, biology and sexuality. It argues that some of these moves are philosophically suspect and that liberal feminism can accommodate the more substantial elements in these radical lines of thought.

Related Papers

Ingrid Holme

Being radical in feminist thought: countering a reductive and deterministic biological manifesto. Abstract Genetic sex is often understood in a deterministic and reductive way; acting as an essential marker true sex, as if sex were a philosophical 'natural kind' (see Dupré, 2002). Feminism is seen as having contentious history which such ideas however this paper argues that the ontological focus of the particular feminisms must be taken into account. The paper examines the splitting of two research fouces; sex development from sex determination, and sex determination from gender development. Reviewing the existing social science work in this area, and drawing on the examples of sex testing in the Olympics and David Reimer, the paper seeks to make visible the complex nature of social scientists seeking to engage with the fast moving research within genetics and genomics.

Renee Heberle & Benjamin Pryor, eds., Imagining Law: On Drucilla Cornell (SUNY Press,

Adam Thurschwell

mariana szapuova

Wendy Lynne Lee

Published, 2015: The International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2nd Edition, Elsevier. Emerging from mainstream liberal feminism of the late 1960s and early 1970s, radical feminists challenge the prevailing view that liberating women consists in reforming social institutions such as marriage, family, or the organization of work. They argued that insofar as a deeper analysis of marriage, family, and work shows the extent to which these institutions continue to privilege some men (white, middle-class, predominantly Christian, and educated) over other men and virtually all women, reform alone cannot achieve the equality liberal feminists envisioned. Radical feminists promote not reform but revolutionary change in the ways we conceive gender, sexual identity, and sexuality. The aim is to end the oppression of women by creating first awareness and then resistance not only to male-dominated or patriarchal institutions, but to the conceptual frameworks that sustain them. However, if the radical lesbian feminist critique of what has grown well-beyond capitalist heteropatriarchy, AKA, corporatist and globalist heteropatriarchy, is correct, this endeavor is more than just important; it is necessary to the emancipation of women. Why? Because in a world confronted by the possibility of ecological apocalypse, critique which represents those most affected--especially women and minorities among women--may be that which offers the most hope.

New Political Science

Sara Wenger

Contemporary Sociology

Lynda Birke

The Yale Law Journal

Anne C. Dailey

Psychology of Women Quarterly

RELATED PAPERS

Jocivan Rangel Leandro

Ioan Mărculeț

Journal of Molecular Endocrinology

KRISHNANAND Dhruw

Clara Salazar

Muhammad Kivly Firdaus

Gazi Medical Journal

DOGUS VURALLI

Sanja Matković

Endocrine Abstracts

Mirjana Stojkovic

Fluid Phase Equilibria

G.Ali Mansoori

Raško Ramadanski

International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health

Yogesh Singhal

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Julio C Bai

The Canadian journal of gastroenterology

Nitin Sarin

The Proceedings of Mechanical Engineering Congress, Japan

TRAN QUANG DAT

Kaushik Banerjee

Ponto E Virgula Revista De Ciencias Sociais Issn 1982 4807

Noêmia Lazzareschi

Procedia Engineering

Rozmarína Dubovská

Journal of Food Science and Technology

sunil Kumar C

Journal of Voice

Amal Quriba

Academic Journal of Islamic Principles and Philosophy

Raha Bistara

Anwendungen und Konzepte der Wirtschaftsinformatik

Frank Morelli

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Radical Feminist essays

Jo Brew’s Easy Way to Give up Patriarchy

Is Barbie a Feminist Movie?

Pronouns are Digital Lipstick

A Three-Way War over Women

Fratriotism

Is Virginia Woolf’s Three Guineas Radical Feminist?

The making of the global feminine class, women don’t celebrate the soccer world cup. it's a global celebration of rape..

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Feminist Political Philosophy

This entry turns to how feminist philosophers have intervened in and, to a great extent, transformed the intellectual field known as political philosophy, which for millennia had largely ignored matters of sex and gender. Traditional political philosophy largely sidelined and excluded the private sphere and civil society from political theorizing, the very realms in which women were largely sequestered. It focused instead on matters of state and governance. The rise of liberalism since the seventeenth century abetted this tendency by drawing a sharp line between the public and the private realms. What happened in the household, it held, were not matters of political concern. Today, thanks largely to feminist interventions, political philosophy is a far richer field of philosophical inquiry. It understands power and governance much more broadly.

In its own right, feminist political philosophy is a branch of both feminist philosophy and political philosophy. As a branch of feminist philosophy, it serves as a form of critique or a hermeneutics of suspicion (Ricœur 1970). That is, it serves as a way of opening up or looking at the political world as it is usually understood and uncovering ways in which women and their current and historical concerns are poorly depicted, represented, and addressed. As a branch of political philosophy, feminist political philosophy serves as a field for developing new ideals, practices, and justifications for how political institutions and practices should be organized and reconstructed. Indeed, the feminist refrain that “the personal is political” speaks to the fact that feminist political philosophy is not only concerned with concepts that have always been mainstays in political philosophy (e.g., justice, equality, freedom), but with redefining and expanding what is considered “political” in the first place (e.g., the family, the workplace, reproduction; Hirschmann 2007). In this sense, feminist political philosophy may be the paradigmatic branch of feminist philosophy.

While feminist philosophy has been instrumental in critiquing and reconstructing many branches of philosophy, from aesthetics to philosophy of science, feminist political philosophy is also paradigmatic because it best exemplifies the point of feminist theory, which is, to borrow a phrase from Marx, not only to understand the world but to change it (Marx 1845). And, though other fields have effects that may change the world, feminist political philosophy focuses most directly on understanding ways in which collective life can be improved. This project involves understanding the ways in which power emerges and is used or misused in public life (see the entry on feminist perspectives on power ). As with other kinds of feminist theory, common themes have emerged for discussion and critique, but there has been little in the way of consensus among feminist theorists on what is the best way to understand them. This introductory article lays out the areas of concern that have occupied this vibrant field of philosophy for the past forty years. It understands feminist philosophy broadly to include work conducted by feminist theorists doing this philosophical work from other disciplines, especially political science but also anthropology, comparative literature, law, and other programs in the humanities and social sciences.

1. Historical Context and Developments

2.1 feminist engagements with liberalism and neoliberalism, 2.2 radical feminism, 2.3 socialist, marxist, and materialist feminisms, 2.4 poststructuralist feminisms, 2.5 care, vulnerability, affect, 2.6 intersectional feminisms, 2.7 transnational, decolonial, and indigenous feminisms, 2.8 feminist democratic theory, 3. new directions in feminist political philosophy, other internet resources, related entries.

Historically, political philosophy focused on the state and various forms of governance. It largely ignored other realms as outside the scope of the political. In general, political thought presumed that political actors were necessarily male and that politics was a masculine enterprise (Okin 1979). It sharply distinguished the public realm of the state from the purportedly non-political realms of civil society and the household, hence forgoing any serious scrutiny of relations of domination in the private sphere. It presumed that women were naturally inferior to men and lacked the capacity to rule themselves. Hence traditional political thought deemed that it was appropriate for them to be ruled by their fathers or husbands, all in the sanctity of the home, immune from public scrutiny. These presuppositions went largely unremarked upon until some women began to demand the same “universal” human dignity that men were proclaiming in newly republican and democratic states of the eighteenth century (Gouges 1791). The first feminist theorists— avant la lettre of feminism—began questioning the tenets of political thought not as an abstract exercise but out of their very real, lived experience. As feminist activists and theorists entered the fray, they quickly pointed out how many of political theory’s presuppositions were thoroughly gendered. Over millennia, feminists noted, political thought coded the public realm as masculine and the private one as feminine; there was the public world of men’s work and the private domain of women’s labor. Political claims of universality were usually quite particular: for men alone.

As they did this work, drawing on their own experience, feminist political thinkers began creating new philosophical concepts. Early feminist thinkers pointed out how social conditions (such as the lack of education) diminished women’s capacities. Later, other theorists pointed to the ways that women and their concerns were excluded or sidelined. Already in the nineteenth century they were noticing how people are socially constituted. By the mid-twentieth century, again drawing from their experience and collective “consciousness-raising” groups, they began challenging norms that countenanced women being harassed on the street by catcalls and whistles. They created new concepts like “sexual harassment” and “objectification”. Over time feminist political philosophers began to notice deeper metaphysical presuppositions underlying gender divisions and to comment on how philosophy had long construed such fundamental concepts as reason, universality, and nature in thoroughly gendered and hence suspect ways. In doing this work, feminist philosophers began to transform the field of political philosophy itself, moving it from its narrow focus on governance to a broader focus on philosophical questions of identity, essence, equity, difference, justice, and the good life.

In the European and U.S. context, earlier generations of feminist scholarship and activism, including the first wave of feminism in the English-speaking world from the 1840s to the 1920s, focused on improving the political, educational, and economic system primarily for middle-class white women. Its greatest achievements were to develop a language of equal rights for women and to garner women the right to vote. Beginning in the 1960s, second wave feminists made further interventions in political theory by drawing on the language of the civil rights movements (e.g., the language of liberation) and on a new feminist consciousness that emerged through women’s solidarity movements and new forms of reflection that uncovered sexist attitudes and impediments throughout the whole of society.

These advances opened up new questions, namely: is there anything that unites women across cultures, time, and contexts? Just as Marxist theory sought out a universal subject in the person of the worker, feminists theorists sought out a commonality that united women across cultures, someone for whom feminist theory could speak. No sooner had that question been posed than it got taken down, as in the title of a paper co-written by the Latina feminist philosopher María Lugones and the white philosopher Elizabeth Spelman: “Have We Got A Theory For You: Feminist Theory, Cultural Imperialism, and the Demand for ‘The Woman’s Voice” (1986). This notion of a universal womanhood was also interrupted by other thinkers, such as bell hooks, saying that it excluded non-white and non-middle-class women’s experience and concerns. Hooks’ 1981 book titled Ain’t I a Woman? exposed mainstream feminism as a movement of a small group of middle- and upper-class white women whose experience was very particular, hardly universal. The work of Lugones, Spelman, hooks and also Cherríe Moraga, Gloria Anzaldúa, Audre Lorde, and others foregrounded the need to account for women’s multiple and complex identities and experiences. By the 1990s the debates about whether there was a coherent concept of woman that could underlie feminist politics was further challenged by non-Western women challenging the Western women’s movement as caught up in Eurocentric ideals that led to the colonization and domination of “Third World” people. What is now known as postcolonial and decolonial theories further heighten the debate between feminists who wanted to identify a universal feminist subject of woman (e.g., Okin, Nussbaum, and Ackerly) and those who call for recognizing multiplicity, diversity, and intersectionality (e.g., Spivak, Narayan, Mahmood, and Jaggar).

As a branch of political philosophy, feminist political philosophy has often mirrored the various divisions at work in political philosophy more broadly. Prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, political philosophy was usually divided into categories such as liberal, conservative, socialist, and Marxist. Except for conservatism, for each category there were often feminists working and critiquing alongside it. Hence, as Alison Jaggar’s classic text, Feminist Politics and Human Nature , spelled out, each ideological approach drew feminist scholars who would both take their cue from and borrow the language of a particular ideology (Jaggar 1983). Jaggar’s text grouped feminist political philosophy into four camps: liberal feminism, socialist feminism, Marxist feminism, and radical feminism. The first three groups followed the lines of Cold War global political divisions: American liberalism, European socialism, and a revolutionary communism (though few in the west would embrace Soviet-style communism). Radical feminism was the most rooted in specifically feminist approaches and activism, developing its own political vocabulary with its roots in the deep criticisms of patriarchy that feminist consciousness had produced in its first and second waves. Otherwise, feminist political philosophy largely followed the lines of traditional political philosophy. But this has never been an uncritical following. As a field bent on changing the world, even liberal feminist theorists tended to criticize liberalism as much or more than they embraced it, and to embrace socialism and other more radical points of view more than to reject them. Still, on the whole, these theorists generally operated within the language and framework of their chosen approach to political philosophy.

Political philosophy began to change enormously in the late 1980s, just before the end of the Cold War, with a new invocation of an old Hegelian category: civil society, an arena of political life intermediate between the state and the household. This was the arena of associations, churches, labor unions, book clubs, choral societies and manifold other nongovernmental yet still public organizations. In the 1980s political theorists began to turn their focus from the state to this intermediate realm, which suddenly took center stage in Eastern Europe in organizations that challenged the power of the state and ultimately led to the downfall of communist regimes. It also opened up more avenues, beyond the state, for feminist political theorizing.

After the end of the Cold War, political philosophy along with political life radically realigned. New attention focused on civil society and the public sphere, especially with the timely translation of Jürgen Habermas’s early work, the Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (Habermas 1962 [1989]). Volumes soon appeared on civil society and the public sphere, focusing on the ways that people organized themselves and developed public power rather than on the ways that the state garnered and exerted its power. In fact, there arose a sense that the public sphere ultimately might exert more power than the state, at least in the fundamental way in which public will is formed and serves to legitimate—or not—state power. In the latter respect, John Rawls’s work was influential by developing a theory of justice that tied the legitimacy of institutions to the normative judgments that a reflective and deliberative people might make (Rawls 1971). By the early 1990s, Marxists seemed to have disappeared or at least become very circumspect (though the downfall of communist regimes needn’t have had any effect on Marxist analysis proper, which never subscribed to Leninist or Maoist thought). Socialists also retreated or transformed themselves into “radical democrats” (Mouffe [ed.] 1992a, 1993, 2000).

Now the old schema of liberal, radical, socialist, and Marxist feminisms were much less relevant. There were fewer debates about what kind of state organization and economic structure would be better for women and more debates about the value of the private sphere of the household and the nongovernmental space of associations. Along with political philosophy more broadly, more feminist political philosophers began to turn to the meaning and interpretation of civil society, the public sphere, and democracy itself. At this point in the early 1990s new work in political theory turning to civil society converged with feminist political theory that was rendering “political” realms that heretofore had been excluded from mainstream political theory. A synergy arose between those studying communitarianisms and feminists working in an ethics-of-care tradition: both pointed to how particular care relations and communal ties were as or more important than abstract principles of justice. They also began to question the binary and hierarchical divisions of justice over care, universality over particularity, and the right over the good, all metaphysical suppositions that were hardly neutral.

2. Contemporary Approaches and Debates

Political philosophy today is significantly more interesting, complex, and capacious thanks to feminist interventions in the field. While the previous section traces these interventions in broad terms, showing how political philosophy has been transformed as a result, this section will provide more detailed descriptions of some of the major sites of concern, debate, and critique animating feminist political philosophy. Because feminist political philosophy is often distinguished by its attention to the concrete realities shaping the lives of women, differences among women (cultural, social, economic, experiential) drive the rich diversity of work being done in this field, and difference itself is a major topic for theorizing with respect to foundational concepts like justice, freedom, and equality. Thus, it is important to emphasize that there is no one feminist perspective shaping work in feminist political philosophy, but a rich variety of perspectives emerging from particular contexts, histories, and traditions. They are sometimes in tension with each other.

Now in the second decade of the twenty-first century, feminist theorists are doing an extraordinary variety of work on matters political and democratic that confront new and/or pressing challenges. Similar developments in the areas of global ethics, public policy, human rights, disabilities studies, bioethics, climate change, and international development blur the distinction between theory and practice in philosophically generative ways.

For example, in global ethics there is a debate over whether there are universal values of justice and freedom that should be intentionally cultivated for women in the developing world or whether cultural diversity should be prioritized. Feminist theorists have sought to answer this question in a number of different and compelling ways. (For some examples see Ackerly 2000; Ackerly & Okin 1999; Benhabib 2002 and 2006; Butler 2000; Gould 2004; Khader 2019; Abu-Lughod 2013; Nussbaum 1999a; and Zerilli 2009; see also the entry on feminist perspectives on globalization .)

Modern abolitionist feminism is driven by the contributions of Black feminist philosophers like Angela Davis (2003, 2005, 2016, and in Davis, Dent, Meiners, & Richie 2022), whose work on the racialized prison industrial complex has helped spur the social-political movement to abolish prisons and develop new theories of restorative justice. Contemporary feminist theories of abolitionism have also built on Michel Foucault ’s critique of the prison, generating new work on political resistance to social structures of incarceration, as well as new ways of exploring foundational political concepts like privacy, freedom, and justice (Pitts 2021b; Zurn & Dilts [ed.] 2016; Zurn 2021). (See also Ruth Wilson Gilmore 2007 and 2022; Davis, Dent, Meiners, & Richie 2022; Guenther 2013; Montford & Taylor [eds] 2022.)

The work of feminist legal theorists (see the entry on feminist philosophy of law ) has been transformative on both the theory and policy fronts. In her 1989 article “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex” Kimberlé Crenshaw critiqued “single-axis” legal frameworks for failing to address race- and gender-based discrimination occurring at the intersection of multiple identities (Crenshaw 1989). Instead, she promoted an intersectional framework and, along with many others, developed a theory of intersectionality as an analytic framework for understanding how compounded and intermeshed systems of privilege and oppression structure experience (see also section 2.6 below). Along with Crenshaw, Anita Allen (2011), Martha Fineman (2008 [2011]), Catherine MacKinnon (1987, 1989), Mari J. Matsuda (1986, 1996), and Patricia J. Williams (1991) are prominent legal scholars whose work has made significant contributions to debates in feminist political philosophy.

Feminists contributions in ethics and moral psychology that emphasize relations of care have also had a major impact on political philosophy. This intervention has challenged masculinist characterizations of political subjects as highly independent and rational, as well as core concepts within political philosophy (e.g., justice, freedom, rights, sovereignty, and autonomy) derived from that characterization (see also section 2.5 below).

Likewise, new philosophical work on disabilities, as the entry on feminist perspectives on disability explains, is informed by a great deal of feminist theory, from standpoint philosophy to feminist phenomenology and feminist care ethics, as well as political philosophical questions of identity, difference, and diversity (see also Kittay & Carlson [ed.] 2010). Feminist political philosophers like Martha Nussbaum (2006) have drawn on the insights of philosophers of disability to offer new conceptions of justice (i.e., the capabilities approach).

Ultimately, the number of approaches that can be taken on any of these issues are as many as the number of philosophers there are working on them. The remainder of this entry will outline a variety of approaches to central concerns in feminist political philosophy, noting general family resemblances among these approaches (i.e., liberal feminist, radical feminist, Marxist feminist, socialist feminist) and highlighting new constellations that have emerged (e.g., intersectional feminisms).

Liberal feminism remains a strong current in feminist political thought. Following liberalism’s focus on freedom and equality, liberal feminism’s primary concern is to protect and enhance women’s personal and political autonomy, the first being the freedom to live one’s life as one chooses and the second being the freedom to help decide the direction of the political community. This follows from Enlightenment liberalism’s core norm of equal respect for personhood, where personhood is tied to moral equality, or the equal worth of persons as moral choosers (Nussbaum 1999a). This approach was invigorated with the publication of John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice (1971) and subsequently his Political Liberalism (1993). Susan Moller Okin (1989, 1979, 1999), Eva Kittay (1999), Martha Nussbaum (2006), and Amy Baehr (2017) have used Rawls’s work productively to extend his theory to attend to women’s concerns.

Perhaps more than any other approach, liberal feminist theory parallels developments in liberal feminist activism. While feminist activists have waged legal and political battles to criminalize, as just one example, violence against women (which previously, in marital relations, hadn’t been considered a crime), feminist political philosophers who have engaged the liberal lexicon have shown how the distinction between private and public realms has served to uphold male domination of women by rendering power relations within the household as “natural” and immune from political regulation. Such political philosophy uncovers how seemingly innocuous and “commonsensical” categories have covert power agendas. For instance, Clare Chambers has critiqued the institution of marriage, arguing that it violates liberal political principles of equality and liberty (Chambers 2017a). Feminist critiques of the public/private split supported legal advances that finally led in the 1980s to the criminalization in the United States of spousal rape (Sigler & Haygood 1988). Efforts to politicize the private sphere have also challenged the capitalist economic system that relies on women’s unpaid labor. As the entry on feminist perspectives on class and work explains, scholars like Silvia Federici have argued that women’s unpaid housework and reproductive labor is essential to the social reproduction of capitalism that exploits women. The “wages for housework” movement led by scholar-activists like Federici is an attempt to demand remuneration for women’s unpaid work (Federici 2012, 2021; more on this Marxist feminist lineage in section 2.3 ). Reproductive justice, pornography, and sex work are yet more issues of convergence for feminist proponents and critics of liberalism alike (see the section on Reproductive Rights in the entry on feminist philosophy of law ; Altman & Watson 2019; Watson & Flanigan 2020). While the U.S. legal tradition has typically grounded abortion rights in the right to privacy, feminist political philosophers such as Shatema Threadcraft (2016) have understood reproductive justice as more fundamentally having to do with the freedom to choose one’s destiny. As such, it is connected to the history of other struggles for race and gender equality in earlier eras.

Carole Pateman and Charles Mills have worked within the liberal tradition to show the limits and faults of social contract theory, and Enlightenment liberalism more broadly, for women and people of color. Their jointly authored book, Contract & Domination , levels a devastating critique against systems of sexual and racial domination. This work engages and critiques some of the most dominant strains of political philosophy. Martha Nussbaum has defended liberalism from some of its critics, arguing that the most appealing versions of liberalism successfully avoid feminist criticisms that liberalism is overly individualistic, abstract, and rationalist (Nussbaum 1999a). She does however take seriously two deep and unresolved problems within liberalism “exposed by feminist thinkers”: (1) the fact of dependency and the need for care and (2) gender inequality and the family (Nussbaum 2004). With respect to dependency—the reality of human dependency and thus the need for care throughout the course of life—Asha Bhandary (2020) has developed a Rawlsian social contract framework to expose and address systemic inequalities in who receives and provides care (see also Bhandary & Baehr [eds] 2021 and section 2.5 below). With respect to the second issue, which deals with the social institution of the family as a site of gender hierarchy and oppression, Marxist, socialist, and materialist feminists have analyzed the material conditions under which these social arrangements (the family and gender hierarchy) have developed. These feminists typically critique liberalism for entrenching social arrangements (such as the public/private split and the system of wage labor) that arise with capitalism and marginalize and disempower women as a social group (see section 2.3 below).

As other feminist critics have argued, many of the central categories of liberalism occlude women’s lived concerns. For example, the right to privacy coveted by classical liberals is a major source of contention for feminists: the private realm, understood as a domain free from state intervention, has historically been the domain where women and children have experienced the bulk of everyday forms of oppression. The liberal private/public distinction sequesters the private sphere, and any harm that may occur there to women, away from political scrutiny (Pateman 1988). Other feminist critics note that liberalism continues to treat as unproblematic concepts that theorists in the 1990s and since have problematized, such as “woman” as a stable and identifiable category and the univocity of the self underlying self-rule or autonomy. Decolonial feminists like María Lugones have exposed the Eurocentric foundations of this view of the self (Lugones 2003; see also section 2.7 ). While Mari Matsuda develops a feminist critique of the methodological abstraction in liberal theories such as Rawls’ A Theory of Justice (Matsuda 1986), others (such as Zerilli 2009) have argued that the universal values that liberal feminists such as Okin invoked were really expanded particulars, with liberal theorists mistaking their ethnocentrically derived values as universal ones. In this vein, Falguni Sheth, focusing on the treatment of Muslim women in the contemporary United States, argues that despite liberal claims to secular neutrality, liberal states actively exclude and discriminate against racialized and marginalized populations (Sheth 2022).