Quick links

- Make a Gift

- Directories

Why Study Philosophy?

What is philosophy, and why should i study it.

“Philosophy” comes from Greek words meaning “love of wisdom.” Philosophy uses the tools of logic and reason to analyze the ways in which humans experience the world. It teaches critical thinking, close reading, clear writing, and logical analysis; it uses these to understand the language we use to describe the world, and our place within it. Different areas of philosophy are distinguished by the questions they ask. Do our senses accurately describe reality? What makes wrong actions wrong? How should we live? These are philosophical questions, and philosophy teaches the ways in which we might begin to answer them.

Students who learn philosophy get a great many benefits from doing so. The tools taught by philosophy are of great use in further education, and in employment. Despite the seemingly abstract nature of the questions philosophers ask, the tools philosophy teaches tend to be highly sought-after by employers. Philosophy students learn how to write clearly, and to read closely, with a critical eye; they are taught to spot bad reasoning, and how to avoid it in their writing and in their work. It is therefore not surprising that philosophy students have historically scored more highly on tests like the LSAT and GRE, on average, than almost any other discipline. Many of our students combine studying philosophy with studying other disciplines.

The most important reason to study philosophy is that it is of enormous and enduring interest. All of us have to answer, for ourselves, the questions asked by philosophers. In this department, students can learn how to ask the questions well, and how we might begin to develop responses. Philosophy is important, but it is also enormously enjoyable, and our faculty contains many award-winning teachers who make the process of learning about philosophy fun. Our faculty are committed to a participatory style of teaching, in which students are provided with the tools and the opportunity to develop and express their own philosophical views.

Critical Thinking “It was in philosophy where I learned rigorous critical thinking, a skill that is invaluable when creating art.” - Donald Daedalus, BA ‘05, Visual Artist “Philosophy taught me to think critically and was the perfect major for law school, giving me an excellent start to law school and my career.” - Rod Nelson, BA ‘75, Lawyer

Tools for Assessing Ethical Issues “The courses I took for my minor in philosophy ... have provided a valuable framework for my career work in the field of global health and have given me a strong foundation for developing a structured, logical argument in various contexts.” - Aubrey Batchelor, Minor ‘09, Global Health Worker “Bioethics is an everyday part of medicine, and my philosophy degree has helped me to work through real-world patient issues and dilemmas.” - Teresa Lee, BA ‘08 Medical Student “The ability to apply an ethical framework to questions that have developed in my career, in taking care of patients ... has been a gift and something that I highly value.” - Natalie Nunes, BA ‘91, Family Physician Analytic Reasoning “... philosophy provided me with the analytical tools necessary to understand a variety of unconventional problems characteristic of the security environment of the last decade.” - Chris Grubb, BA ‘98, US Marine “Philosophy provides intellectual resources, critical and creative thinking capacity that are indispensable for success in contemporary international security environment “ - Richard Paz, BA ‘87, US Military Officer

Understanding Others’ Perspectives “... philosophy grounds us in an intellectual tradition larger than our own personal opinions. ... *making+ it is easier to be respectful of and accommodating to individual differences in clients (and colleagues)...” - Diane Fructher Strother, BA ‘00, Clinical Psychologist “... comprehensive exposure to numerous alternative world/ethical views has helped me with my daily interaction with all different types of people of ethnic, cultural, and political orientation backgrounds.” - David Prestin, BA ‘07, Engineer

Evaluating Information “Analyzing information and using it to form logical conclusions is a huge part of philosophy and was thus vital to my success in this position.” - Kevin Duchmann, BA ‘07, Inventory Control Analyst

Writing Skills “My philosophy degree has been incredibly important in developing my analytical and writing skills.” - Teresa Lee, BA ‘08, Medical Student

- YouTube

- Newsletter

- More ways to connect

Characteristics of Philosophy: A Deep Dive into Critical Thinking

- April 17, 2024

Philosophy, derived from the Greek words “philo” (love) and “sophia” (wisdom), embodies the relentless pursuit of knowledge and understanding about the most fundamental aspects of existence. It’s an intellectual discipline that has intrigued and challenged some of history’s greatest minds. If you’ve ever pondered questions about the nature of reality, the meaning of life, or how we can know anything at all, you’ve already embarked on a philosophical journey.

What are the characteristics in philosophy?

This article delves into the core characteristics that define philosophical thinking, making it a potent force for refining knowledge and transforming the way we perceive the world around us.

1. Wonder and Curiosity: The Fuel of Philosophy

At its heart, philosophy is ignited by a sense of wonder. This childlike curiosity encourages us to move beyond taking things for granted and question even the most basic assumptions. Philosophers marvel at the seemingly ordinary, recognizing the extraordinary depth hidden within everyday concepts and questions like:

- Existence: What does it mean to exist?

- Reality: What is the true nature of reality? Is the world as we perceive it an accurate representation?

- Knowledge: How do we know things? What are the limits of human knowledge?

- Morality: What is right and wrong? How should we live our lives?

- Beauty: What is beauty? Why do certain things appeal to our sense of aesthetics?

2. Contemplation and Critical Analysis: The Philosopher’s Toolbox

Philosophers don’t just ask questions – they rigorously analyze them. Contemplation, the act of deep and focused thought, is one of their most vital tools. Through contemplation, philosophers dissect and scrutinize concepts, ideas, and arguments.

Critical analysis lies at the core of philosophical thinking. It involves several elements:

- Breaking Down Ideas: Philosophers decompose complex ideas into smaller, more manageable components for a clearer understanding.

- Identifying Assumptions: Every argument or line of reasoning rests on assumptions. Philosophers uncover these assumptions and test their validity.

- Logic and Argumentation: Philosophy heavily emphasizes the use of logic to build sound arguments and assess the strength of existing ones.

- Examining Evidence: When applicable, philosophers evaluate the reliability and quality of evidence supporting particular perspectives.

3. Rationality: The Guiding Principle

Unlike blind faith or reliance on mere intuition, philosophy prioritizes reason. This means:

- Emphasis on Justifications: Philosophers strive to provide reasoned justifications for their beliefs rather than relying on tradition, authority figures, or unchecked emotions.

- Rigorous Evaluation: Philosophical arguments are subjected to meticulous scrutiny, ensuring they are logically sound and consistent with available evidence.

- Open to Revision: As new information or stronger arguments emerge, philosophers remain open-minded and willing to change their positions.

4. Intellectual Independence: Thinking for Yourself

While philosophers learn from and engage with the ideas of others, philosophical thinking demands taking ownership of your own thoughts. True philosophical inquiry necessitates:

- Questioning Dogma: Taking a critical stance towards received wisdom or commonly held beliefs.

- Forming Your Own Beliefs: Analyzing various perspectives and ultimately crafting your own well-reasoned arguments and conclusions.

- Standing By Your Convictions: Defending your ideas with intellectual rigor, even if they may clash with popular sentiment.

5. Holistic and Systematic Approach: Connecting the Dots

Philosophy doesn’t just tackle isolated questions. It endeavors to create a comprehensive and coherent understanding of the world and how various aspects relate to each other. Philosophers seek to build systematic frameworks of thought that integrate concepts and theories across different domains.

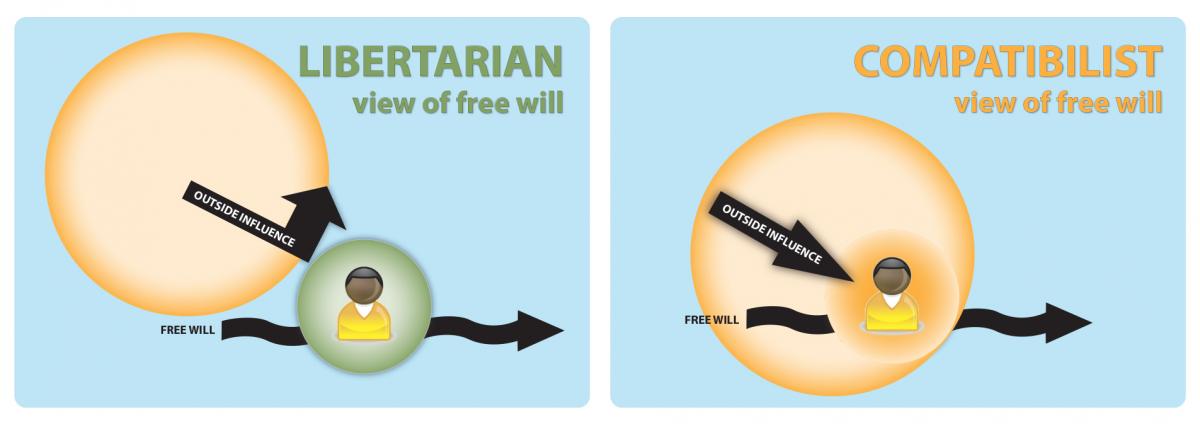

For instance, a philosopher contemplating morality wouldn’t just consider individual ethical dilemmas. They might also connect their ideas about morality to their views on human nature, free will, and the structure of society as a whole.

6. The Search for Clarity: Unpacking Ambiguity

The language we use every day is often filled with vague or ambiguous terms. Philosophers strive for clarity in their thinking and communication by:

- Conceptual Analysis: Philosophers dissect and analyze the meaning of key concepts. Consider the concept of justice—what qualities or conditions must be present for something to be called “just”?

- Defining Terms: Precise definitions are essential to avoid misunderstandings and ensure arguments are based on a shared understanding.

- Distinguishing Nuances: By drawing fine distinctions between similar concepts, philosophers reveal shades of meaning that might otherwise be overlooked.

7. Universal Questions: The Heart of Philosophical Inquiry

While philosophy tackles diverse issues, certain fundamental questions continually resurface throughout its history. These enduring universal inquiries often fall within core branches of philosophy:

- Metaphysics: The study of the fundamental nature of reality. Questions include: Does the world exist independently of our minds? Is there a single underlying substance? Do we have free will?

- Epistemology: The study of knowledge. Key questions are: What is knowledge? How do we acquire it? What can we truly know?

- Ethics: The study of morality. Questions focus on: How should we live? What is right and wrong? What does it mean to live a good life?

- Aesthetics: The study of beauty and art. Philosophers contemplate: What makes something beautiful? Can art have objective value? What is the purpose of art?

- Logic: The study of reasoning and argumentation. Its questions address: What makes an argument valid? What are the principles of sound reasoning? What are common fallacies (errors in reasoning)?

8. A Dialogue Through Time: Engaging with the Great Thinkers

Philosophy is an ongoing conversation across centuries. Today’s philosophers build upon, critique, and refine the ideas of past luminaries like:

- Ancient Greek Philosophers: Socrates, Plato, Aristotle

- Enlightenment Thinkers: Rene Descartes, John Locke, Immanuel Kant

- Existentialists: Soren Kierkegaard, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir

- Contemporary Philosophers: A diverse range of thinkers working on issues of logic, language, mind, ethics, and social and political philosophy.

Studying the rich history of philosophical thought provides a wealth of perspectives and expands our intellectual horizons.

The Benefits of Philosophical Thinking

Cultivating a philosophical mindset isn’t merely an abstract intellectual exercise. It has practical benefits for our daily lives. Philosophy helps us to:

- Become Better Problem Solvers: By breaking down problems, analyzing arguments, and exploring alternative perspectives, we enhance our problem-solving skills.

- Make Informed Decisions: Philosophical reflection helps us weigh evidence, question assumptions, and make decisions guided by reason rather than impulse.

- Develop Intellectual Humility: Recognizing the limits of our knowledge and the complexity of issues fosters a sense of humility and an eagerness to keep learning.

- Communicate Effectively: The emphasis on clarity and logical argumentation makes us more persuasive and articulate communicators.

- Tolerate Ambiguity: Philosophy helps us navigate complex issues where easy answers might not exist, increasing our comfort with uncertainty

- Live an Examined Life: Ultimately, philosophy encourages us to become more mindful and intentional about our values, beliefs, and how we choose to live.

How to Start Your Philosophical Journey

You don’t need a formal philosophy degree to embark on a philosophical adventure. Here’s how to get started:

- Read Introductions to Philosophy: Look for books or online resources that offer an overview of key philosophical ideas and concepts.

- Explore Online Resources: Websites like the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy provide in-depth articles on various philosophical topics.

- Take Philosophy Courses: Many universities offer online or in-person philosophy courses for the general public.

- Join Discussion Groups : Engage in thoughtful discussions with like-minded individuals in online forums or local philosophy meetups.

Remember: Philosophy is not about finding definitive answers but rather, asking better questions.

Let me know if you’d like to explore any specific aspects of philosophy or delve into the work of particular philosophers in more detail. I’m here to support your journey!

Related Posts

The Optimist’s Guide to the Future: Why Humanity’s Best Days Are Ahead

- April 13, 2024

Conversation Between Jordan Peterson and Lex Fridman

- March 3, 2023

Who Proposed the Philosophical Idea of “I Think, Therefore I Am” (Cogito ergo sum)

- August 11, 2021

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from curiosity guide.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

#1 Victorian uni for graduate employment 1

#1 in the world for sport science 2

#1 Victorian uni for course satisfaction 3

For career and life, this. gives you practical advice to help you on your journey.

- Self-improvement

Subscribe now to this. by Deakin University for a monthly dose of career and life advice.

Curious about this. ? Find out more

Have something to share? Contact us

Why study philosophy? Learn critical thinking skills for life

Related articles.

What is compassion fatigue and how can it affect your career?

What’s it really like to be an architect?

The fight for gender equity in STEM

What is truth? What is knowledge? Do people have free will? What makes our actions or personality traits good or bad ? Is there a God? These are just some of the brain-bending questions you might ask as a student of philosophy.

‘Questions like these might look straightforward, but when you start to explore them it’s clear they’re really complicated questions that require careful and thoughtful argument to try and get some answers,’ says Associate Professor Patrick Stokes, a senior lecturer in philosophy at Deakin.

Philosophy teaches critical thinking skills that will help you navigate life and work. And in the age of fake news and post-truth, the study of philosophy is especially important, says Assoc. Prof. Stokes.

‘Knowing who to believe and who to listen to, and being able to tell a good claim from a bad claim or a good argument from a bad argument, is more urgent now than it’s ever been.’

Here are some of the most compelling reasons to study philosophy and ask those big, bold questions.

Learn to think critically

Philosophy is an activity of thought more than a body of settled knowledge, so much so that even questions of, ‘what is philosophy?’ and, ‘what does philosophy mean?’ are themselves philosophical questions. ‘One of the fun things about philosophy is philosophers can’t even agree on what it is,’ Assoc. Prof. Stokes says.

So what is philosophy according to Assoc. Prof. Stokes? Here’s his take: ‘Philosophy is a discipline that rigorously investigates some of the deepest and most fundamental questions of human existence – questions about the nature of being, right and wrong, and good and bad. It’s concerned with a number of really basic problems that other disciplines might generate but can’t answer.’

Studying philosophy not only involves asking the big questions – it also teaches important critical thinking skills as you work to find the answers. Assoc. Prof. Stokes says seminar teaching is one of the most important modes of learning in philosophy because it’s an opportunity for students to debate, argue and workshop ideas .

‘A lot of students are initially a little surprised that when we study philosophy, we want to know what you think. We want you to articulate your own view as a philosopher and, crucially, we also expect you to be able to defend that view and to argue for your position.

‘You come into the classroom as a philosopher, pretty much from day one.’

'Philosophy is a discipline that rigorously investigates some of the deepest and most fundamental questions of human existence – questions about the nature of being, right and wrong, and good and bad.' Associate Professor Patrick Stokes, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Deakin University

Channel intellectual curiosity

There’s perhaps no better answer to the quandary of why study philosophy than ‘sheer intellectual curiosity’, says Assoc. Prof. Stokes. ‘It’s a really open, broad field for anyone who wants to stretch their legs intellectually and try out some new things.’

Philosophy degrees will introduce you to the many and varied philosophy schools of thought, like ethics and logic. What is ethics in philosophy? What is logic in philosophy? These are complicated and intriguing questions, says Assoc. Prof. Stokes.

‘Ethics is concerned with how we should live and what should govern the way in which we behave in relation to other people and to ourselves. It centres on questions of right and wrong, good and bad.’

Logic is the study of principles of reasoning. ‘It’s about trying to find the necessary, almost mathematical, structure of argument and reason, and trying to explain why certain statements have to be true and why certain statements can’t be true,’ Assoc. Prof. Stokes says.

Other fascinating branches of philosophy include phenomenology – the study of human experience – and stoicism, which examines strategies to ‘live a good life by making ourselves less vulnerable to suffering’, says Assoc. Prof. Stokes.

Kickstart your career

If you’re wondering why study philosophy in a practical, career-focused sense, there are a lot of less abstract benefits.

‘Regardless of which profession you go into or which career path you end up choosing, critical reasoning skills, the ability to identify and interrogate assumptions, being comfortable with challenging your own assumptions, spotting a bad argument, being able to construct a good argument – all of these things are really important life skills and really important employability skills,’ Assoc. Prof. Stokes says. ‘They will all carry you through whatever you choose to do in life.’

He says many philosophy students study the discipline as part of an arts degree , and there’s a significant cohort from other backgrounds like creative arts, nursing and teaching.

‘Students like the idea that philosophy will give them a greater ethical grounding and a deeper understanding of different cultures and fundamental assumptions about the way the world is, which will help them in their chosen field of work.’

Want to explore life’s big questions? Study philosophy as a major or minor in your degree.

Associate Professor of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts and Education, Deakin University

Read profile

Share this.

Explore more.

Subscribe for a regular dose of technology, innovation, culture and personal development.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

13.7 Cosmos & Culture

How (and when) to think like a philosopher.

Tania Lombrozo

As an undergraduate, I majored in philosophy — a purportedly useless major, except that it teaches you how to think, write and speak.

The skills I was learning from working through papers and arguments extended well beyond the coursework itself, yielding habitual patterns of reasoning that made me a more discerning scientist, a more careful writer and a better thinker all around. Within and beyond philosophy, I was learning to spot poor arguments, uncover hidden assumptions, tease out subtle implications and recognize false dichotomies. (It was around this time that my then boyfriend, now husband, jokingly gifted me a modified light box with a button that I could press to light up the damning message: "Distinction blurred!")

Of course, good thinking isn't the sole province of philosophy. Training in any discipline or area of expertise teaches you habits of mind that — hopefully — lead to better performance in that domain. But philosophy is unusual in its explicit focus on the structure of arguments across a broad range of topics, from the meaning of words to the nature of knowledge, from ethics to animal minds. It makes sense, then, that training in philosophy might be unusual in its potential to yield general-purpose tools for better thinking.

So what do these tools for better thinking look like?

In a new article published in Aeon , philosopher Alan Hájek presents a "philosophy tool kit," sharing some common philosophical moves that apply both within and beyond academic philosophy. What Hájek offers isn't logic or probability theory (though that's useful, too), but rather common heuristics or "rules of thumb" that help philosophers quickly identify problematic claims or assumptions. These heuristics are intended to make difficult reasoning tasks easier for the philosophically untrained, though Hájek is clear that "there are no shortcuts to profundity" — the tools are a starter set, not a complete kit nor blueprints for the construction of worthwhile arguments.

Several of Hájek's tools involve questioning assumptions in the way a claim or question is posed. For instance, asking what the right thing to do is presupposes that there is a single right thing to do. In some cases, that presupposition is wrong: There could be no right thing to do, or there could be many right things to do. Encountering "the" should therefore set off a minor alarm, prompting you to consider whether the presupposition is warranted.

A second tool comes in handy when evaluating a claim that is supposed to apply to many cases. Here it's appropriate to look for counterexamples that might disconfirm or limit the scope of the claim, but where might such counterexamples be found? It's often effective to consider extreme or "edge" cases. For instance, in considering whether there are counterexamples to the claim that everything has a cause, one might consider what caused the first cause, or the set of all causes. As a more pedestrian example, evaluating the claim that "everyone likes a good book" might prompt you to consider extremes in age (do newborns like a good book?) or kinds of people (do supervillains like a good book?).

For additional tools, and a more complete exposition, readers are encouraged to read Hájek's article . But I want to end with a final reflection for readers of 13.7 . If these thinking tools are so useful, why do we need special training to acquire them? Why aren't they built into our cognitive machinery, or acquired through our years of experience evaluating claims and arguments in everyday life?

Hájek identifies one reason in his discussion of what he calls the "contrastive-stress heuristic": We fall prey to various cognitive biases that can lead us astray. One example is confirmation bias, the tendency to seek and favor evidence that supports, rather than challenges, the hypotheses we (prefer to) believe. A strategy like systematically considering alternative possibilities — common to both philosophical and scientific thinking — is useful, in part, because it helps overcome this bias.

But here's a second (and more speculative) hypothesis for why many habits of philosophical thinking might not come naturally. The hypothesis is that some tools for critical evaluation run counter to another valuable set of tools: our tools for effective social engagement. These tools help us make sense of what someone is saying by encouraging us to interpret underspecified claims in the most positive light; they help us coordinate conversation by establishing common ground.

When someone asks us for "the right thing to do," we're inclined to engage in the conversation they've invited us to engage in: one in which we assume there is a right thing to do, and we help them to find it. When someone says "everyone likes a good book," we understand them to be telling us something about the kinds of people relevant to our current conversational context, not something true of every single person.

If this is right, then some forms of critical evaluation and philosophical thinking are hard because they force us to suspend other habits of mind; habits that serve us well when our goal is to engage or persuade or befriend, but less well when our goal is to arrive at a precise characterization of what's true, or of what follows from what. The trick, then, is not only to acquire Hájek's philosophy tool kit, but to know when to use it.

Tania Lombrozo is a psychology professor at the University of California, Berkeley. She writes about psychology, cognitive science and philosophy, with occasional forays into parenting and veganism. You can keep up with more of what she is thinking on Twitter: @TaniaLombrozo

- critical evaluation

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Back to Entry

- Entry Contents

- Entry Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Supplement to Critical Thinking

This supplement elaborates on the history of the articulation, promotion and adoption of critical thinking as an educational goal.

John Dewey (1910: 74, 82) introduced the term ‘critical thinking’ as the name of an educational goal, which he identified with a scientific attitude of mind. More commonly, he called the goal ‘reflective thought’, ‘reflective thinking’, ‘reflection’, or just ‘thought’ or ‘thinking’. He describes his book as written for two purposes. The first was to help people to appreciate the kinship of children’s native curiosity, fertile imagination and love of experimental inquiry to the scientific attitude. The second was to help people to consider how recognizing this kinship in educational practice “would make for individual happiness and the reduction of social waste” (iii). He notes that the ideas in the book obtained concreteness in the Laboratory School in Chicago.

Dewey’s ideas were put into practice by some of the schools that participated in the Eight-Year Study in the 1930s sponsored by the Progressive Education Association in the United States. For this study, 300 colleges agreed to consider for admission graduates of 30 selected secondary schools or school systems from around the country who experimented with the content and methods of teaching, even if the graduates had not completed the then-prescribed secondary school curriculum. One purpose of the study was to discover through exploration and experimentation how secondary schools in the United States could serve youth more effectively (Aikin 1942). Each experimental school was free to change the curriculum as it saw fit, but the schools agreed that teaching methods and the life of the school should conform to the idea (previously advocated by Dewey) that people develop through doing things that are meaningful to them, and that the main purpose of the secondary school was to lead young people to understand, appreciate and live the democratic way of life characteristic of the United States (Aikin 1942: 17–18). In particular, school officials believed that young people in a democracy should develop the habit of reflective thinking and skill in solving problems (Aikin 1942: 81). Students’ work in the classroom thus consisted more often of a problem to be solved than a lesson to be learned. Especially in mathematics and science, the schools made a point of giving students experience in clear, logical thinking as they solved problems. The report of one experimental school, the University School of Ohio State University, articulated this goal of improving students’ thinking:

Critical or reflective thinking originates with the sensing of a problem. It is a quality of thought operating in an effort to solve the problem and to reach a tentative conclusion which is supported by all available data. It is really a process of problem solving requiring the use of creative insight, intellectual honesty, and sound judgment. It is the basis of the method of scientific inquiry. The success of democracy depends to a large extent on the disposition and ability of citizens to think critically and reflectively about the problems which must of necessity confront them, and to improve the quality of their thinking is one of the major goals of education. (Commission on the Relation of School and College of the Progressive Education Association 1943: 745–746)

The Eight-Year Study had an evaluation staff, which developed, in consultation with the schools, tests to measure aspects of student progress that fell outside the focus of the traditional curriculum. The evaluation staff classified many of the schools’ stated objectives under the generic heading “clear thinking” or “critical thinking” (Smith, Tyler, & Evaluation Staff 1942: 35–36). To develop tests of achievement of this broad goal, they distinguished five overlapping aspects of it: ability to interpret data, abilities associated with an understanding of the nature of proof, and the abilities to apply principles of science, of social studies and of logical reasoning. The Eight-Year Study also had a college staff, directed by a committee of college administrators, whose task was to determine how well the experimental schools had prepared their graduates for college. The college staff compared the performance of 1,475 college students from the experimental schools with an equal number of graduates from conventional schools, matched in pairs by sex, age, race, scholastic aptitude scores, home and community background, interests, and probable future. They concluded that, on 18 measures of student success, the graduates of the experimental schools did a somewhat better job than the comparison group. The graduates from the six most traditional of the experimental schools showed no large or consistent differences. The graduates from the six most experimental schools, on the other hand, had much greater differences in their favour. The graduates of the two most experimental schools, the college staff reported:

… surpassed their comparison groups by wide margins in academic achievement, intellectual curiosity, scientific approach to problems, and interest in contemporary affairs. The differences in their favor were even greater in general resourcefulness, in enjoyment of reading, [in] participation in the arts, in winning non-academic honors, and in all aspects of college life except possibly participation in sports and social activities. (Aikin 1942: 114)

One of these schools was a private school with students from privileged families and the other the experimental section of a public school with students from non-privileged families. The college staff reported that the graduates of the two schools were indistinguishable from each other in terms of college success.

In 1933 Dewey issued an extensively rewritten edition of his How We Think (Dewey 1910), with the sub-title “A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process”. Although the restatement retains the basic structure and content of the original book, Dewey made a number of changes. He rewrote and simplified his logical analysis of the process of reflection, made his ideas clearer and more definite, replaced the terms ‘induction’ and ‘deduction’ by the phrases ‘control of data and evidence’ and ‘control of reasoning and concepts’, added more illustrations, rearranged chapters, and revised the parts on teaching to reflect changes in schools since 1910. In particular, he objected to one-sided practices of some “experimental” and “progressive” schools that allowed children freedom but gave them no guidance, citing as objectionable practices novelty and variety for their own sake, experiences and activities with real materials but of no educational significance, treating random and disconnected activity as if it were an experiment, failure to summarize net accomplishment at the end of an inquiry, non-educative projects, and treatment of the teacher as a negligible factor rather than as “the intellectual leader of a social group” (Dewey 1933: 273). Without explaining his reasons, Dewey eliminated the previous edition’s uses of the words ‘critical’ and ‘uncritical’, thus settling firmly on ‘reflection’ or ‘reflective thinking’ as the preferred term for his subject-matter. In the revised edition, the word ‘critical’ occurs only once, where Dewey writes that “a person may not be sufficiently critical about the ideas that occur to him” (1933: 16, italics in original); being critical is thus a component of reflection, not the whole of it. In contrast, the Eight-Year Study by the Progressive Education Association treated ‘critical thinking’ and ‘reflective thinking’ as synonyms.

In the same period, Dewey collaborated on a history of the Laboratory School in Chicago with two former teachers from the school (Mayhew & Edwards 1936). The history describes the school’s curriculum and organization, activities aimed at developing skills, parents’ involvement, and the habits of mind that the children acquired. A concluding chapter evaluates the school’s achievements, counting as a success its staging of the curriculum to correspond to the natural development of the growing child. In two appendices, the authors describe the evolution of Dewey’s principles of education and Dewey himself describes the theory of the Chicago experiment (Dewey 1936).

Glaser (1941) reports in his doctoral dissertation the method and results of an experiment in the development of critical thinking conducted in the fall of 1938. He defines critical thinking as Dewey defined reflective thinking:

Critical thinking calls for a persistent effort to examine any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the evidence that supports it and the further conclusions to which it tends. (Glaser 1941: 6; cf. Dewey 1910: 6; Dewey 1933: 9)

In the experiment, eight lesson units directed at improving critical thinking abilities were taught to four grade 12 high school classes, with pre-test and post-test of the students using the Otis Quick-Scoring Mental Ability Test and the Watson-Glaser Tests of Critical Thinking (developed in collaboration with Glaser’s dissertation sponsor, Goodwin Watson). The average gain in scores on these tests was greater to a statistically significant degree among the students who received the lessons in critical thinking than among the students in a control group of four grade 12 high school classes taking the usual curriculum in English. Glaser concludes:

The aspect of critical thinking which appears most susceptible to general improvement is the attitude of being disposed to consider in a thoughtful way the problems and subjects that come within the range of one’s experience. An attitude of wanting evidence for beliefs is more subject to general transfer. Development of skill in applying the methods of logical inquiry and reasoning, however, appears to be specifically related to, and in fact limited by, the acquisition of pertinent knowledge and facts concerning the problem or subject matter toward which the thinking is to be directed. (Glaser 1941: 175)

Retest scores and observable behaviour indicated that students in the intervention group retained their growth in ability to think critically for at least six months after the special instruction.

In 1948 a group of U.S. college examiners decided to develop taxonomies of educational objectives with a common vocabulary that they could use for communicating with each other about test items. The first of these taxonomies, for the cognitive domain, appeared in 1956 (Bloom et al. 1956), and included critical thinking objectives. It has become known as Bloom’s taxonomy. A second taxonomy, for the affective domain (Krathwohl, Bloom, & Masia 1964), and a third taxonomy, for the psychomotor domain (Simpson 1966–67), appeared later. Each of the taxonomies is hierarchical, with achievement of a higher educational objective alleged to require achievement of corresponding lower educational objectives.

Bloom’s taxonomy has six major categories. From lowest to highest, they are knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Within each category, there are sub-categories, also arranged hierarchically from the educationally prior to the educationally posterior. The lowest category, though called ‘knowledge’, is confined to objectives of remembering information and being able to recall or recognize it, without much transformation beyond organizing it (Bloom et al. 1956: 28–29). The five higher categories are collectively termed “intellectual abilities and skills” (Bloom et al. 1956: 204). The term is simply another name for critical thinking abilities and skills:

Although information or knowledge is recognized as an important outcome of education, very few teachers would be satisfied to regard this as the primary or the sole outcome of instruction. What is needed is some evidence that the students can do something with their knowledge, that is, that they can apply the information to new situations and problems. It is also expected that students will acquire generalized techniques for dealing with new problems and new materials. Thus, it is expected that when the student encounters a new problem or situation, he will select an appropriate technique for attacking it and will bring to bear the necessary information, both facts and principles. This has been labeled “critical thinking” by some, “reflective thinking” by Dewey and others, and “problem solving” by still others. In the taxonomy, we have used the term “intellectual abilities and skills”. (Bloom et al. 1956: 38)

Comprehension and application objectives, as their names imply, involve understanding and applying information. Critical thinking abilities and skills show up in the three highest categories of analysis, synthesis and evaluation. The condensed version of Bloom’s taxonomy (Bloom et al. 1956: 201–207) gives the following examples of objectives at these levels:

- analysis objectives : ability to recognize unstated assumptions, ability to check the consistency of hypotheses with given information and assumptions, ability to recognize the general techniques used in advertising, propaganda and other persuasive materials

- synthesis objectives : organizing ideas and statements in writing, ability to propose ways of testing a hypothesis, ability to formulate and modify hypotheses

- evaluation objectives : ability to indicate logical fallacies, comparison of major theories about particular cultures

The analysis, synthesis and evaluation objectives in Bloom’s taxonomy collectively came to be called the “higher-order thinking skills” (Tankersley 2005: chap. 5). Although the analysis-synthesis-evaluation sequence mimics phases in Dewey’s (1933) logical analysis of the reflective thinking process, it has not generally been adopted as a model of a critical thinking process. While commending the inspirational value of its ratio of five categories of thinking objectives to one category of recall objectives, Ennis (1981b) points out that the categories lack criteria applicable across topics and domains. For example, analysis in chemistry is so different from analysis in literature that there is not much point in teaching analysis as a general type of thinking. Further, the postulated hierarchy seems questionable at the higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. For example, ability to indicate logical fallacies hardly seems more complex than the ability to organize statements and ideas in writing.

A revised version of Bloom’s taxonomy (Anderson et al. 2001) distinguishes the intended cognitive process in an educational objective (such as being able to recall, to compare or to check) from the objective’s informational content (“knowledge”), which may be factual, conceptual, procedural, or metacognitive. The result is a so-called “Taxonomy Table” with four rows for the kinds of informational content and six columns for the six main types of cognitive process. The authors name the types of cognitive process by verbs, to indicate their status as mental activities. They change the name of the ‘comprehension’ category to ‘understand’ and of the ‘synthesis’ category to ’create’, and switch the order of synthesis and evaluation. The result is a list of six main types of cognitive process aimed at by teachers: remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, and create. The authors retain the idea of a hierarchy of increasing complexity, but acknowledge some overlap, for example between understanding and applying. And they retain the idea that critical thinking and problem solving cut across the more complex cognitive processes. The terms ‘critical thinking’ and ‘problem solving’, they write:

are widely used and tend to become touchstones of curriculum emphasis. Both generally include a variety of activities that might be classified in disparate cells of the Taxonomy Table. That is, in any given instance, objectives that involve problem solving and critical thinking most likely call for cognitive processes in several categories on the process dimension. For example, to think critically about an issue probably involves some Conceptual knowledge to Analyze the issue. Then, one can Evaluate different perspectives in terms of the criteria and, perhaps, Create a novel, yet defensible perspective on this issue. (Anderson et al. 2001: 269–270; italics in original)

In the revised taxonomy, only a few sub-categories, such as inferring, have enough commonality to be treated as a distinct critical thinking ability that could be taught and assessed as a general ability.

A landmark contribution to philosophical scholarship on the concept of critical thinking was a 1962 article in the Harvard Educational Review by Robert H. Ennis, with the title “A concept of critical thinking: A proposed basis for research in the teaching and evaluation of critical thinking ability” (Ennis 1962). Ennis took as his starting-point a conception of critical thinking put forward by B. Othanel Smith:

We shall consider thinking in terms of the operations involved in the examination of statements which we, or others, may believe. A speaker declares, for example, that “Freedom means that the decisions in America’s productive effort are made not in the minds of a bureaucracy but in the free market”. Now if we set about to find out what this statement means and to determine whether to accept or reject it, we would be engaged in thinking which, for lack of a better term, we shall call critical thinking. If one wishes to say that this is only a form of problem-solving in which the purpose is to decide whether or not what is said is dependable, we shall not object. But for our purposes we choose to call it critical thinking. (Smith 1953: 130)

Adding a normative component to this conception, Ennis defined critical thinking as “the correct assessing of statements” (Ennis 1962: 83). On the basis of this definition, he distinguished 12 “aspects” of critical thinking corresponding to types or aspects of statements, such as judging whether an observation statement is reliable and grasping the meaning of a statement. He noted that he did not include judging value statements. Cutting across the 12 aspects, he distinguished three dimensions of critical thinking: logical (judging relationships between meanings of words and statements), criterial (knowledge of the criteria for judging statements), and pragmatic (the impression of the background purpose). For each aspect, Ennis described the applicable dimensions, including criteria. He proposed the resulting construct as a basis for developing specifications for critical thinking tests and for research on instructional methods and levels.

In the 1970s and 1980s there was an upsurge of attention to the development of thinking skills. The annual International Conference on Critical Thinking and Educational Reform has attracted since its start in 1980 tens of thousands of educators from all levels. In 1983 the College Entrance Examination Board proclaimed reasoning as one of six basic academic competencies needed by college students (College Board 1983). Departments of education in the United States and around the world began to include thinking objectives in their curriculum guidelines for school subjects. For example, Ontario’s social sciences and humanities curriculum guideline for secondary schools requires “the use of critical and creative thinking skills and/or processes” as a goal of instruction and assessment in each subject and course (Ontario Ministry of Education 2013: 30). The document describes critical thinking as follows:

Critical thinking is the process of thinking about ideas or situations in order to understand them fully, identify their implications, make a judgement, and/or guide decision making. Critical thinking includes skills such as questioning, predicting, analysing, synthesizing, examining opinions, identifying values and issues, detecting bias, and distinguishing between alternatives. Students who are taught these skills become critical thinkers who can move beyond superficial conclusions to a deeper understanding of the issues they are examining. They are able to engage in an inquiry process in which they explore complex and multifaceted issues, and questions for which there may be no clear-cut answers (Ontario Ministry of Education 2013: 46).

Sweden makes schools responsible for ensuring that each pupil who completes compulsory school “can make use of critical thinking and independently formulate standpoints based on knowledge and ethical considerations” (Skolverket 2018: 12). Subject syllabi incorporate this requirement, and items testing critical thinking skills appear on national tests that are a required step toward university admission. For example, the core content of biology, physics and chemistry in years 7-9 includes critical examination of sources of information and arguments encountered by pupils in different sources and social discussions related to these sciences, in both digital and other media. (Skolverket 2018: 170, 181, 192). Correspondingly, in year 9 the national tests require using knowledge of biology, physics or chemistry “to investigate information, communicate and come to a decision on issues concerning health, energy, technology, the environment, use of natural resources and ecological sustainability” (see the message from the School Board ). Other jurisdictions similarly embed critical thinking objectives in curriculum guidelines.

At the college level, a new wave of introductory logic textbooks, pioneered by Kahane (1971), applied the tools of logic to contemporary social and political issues. Popular contemporary textbooks of this sort include those by Bailin and Battersby (2016b), Boardman, Cavender and Kahane (2018), Browne and Keeley (2018), Groarke and Tindale (2012), and Moore and Parker (2020). In their wake, colleges and universities in North America transformed their introductory logic course into a general education service course with a title like ‘critical thinking’ or ‘reasoning’. In 1980, the trustees of California’s state university and colleges approved as a general education requirement a course in critical thinking, described as follows:

Instruction in critical thinking is to be designed to achieve an understanding of the relationship of language to logic, which should lead to the ability to analyze, criticize, and advocate ideas, to reason inductively and deductively, and to reach factual or judgmental conclusions based on sound inferences drawn from unambiguous statements of knowledge or belief. The minimal competence to be expected at the successful conclusion of instruction in critical thinking should be the ability to distinguish fact from judgment, belief from knowledge, and skills in elementary inductive and deductive processes, including an understanding of the formal and informal fallacies of language and thought. (Dumke 1980)

Since December 1983, the Association for Informal Logic and Critical Thinking has sponsored sessions at the three annual divisional meetings of the American Philosophical Association. In December 1987, the Committee on Pre-College Philosophy of the American Philosophical Association invited Peter Facione to make a systematic inquiry into the current state of critical thinking and critical thinking assessment. Facione assembled a group of 46 other academic philosophers and psychologists to participate in a multi-round Delphi process, whose product was entitled Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction (Facione 1990a). The statement listed abilities and dispositions that should be the goals of a lower-level undergraduate course in critical thinking. Researchers in nine European countries determined which of these skills and dispositions employers expect of university graduates (Dominguez 2018 a), compared those expectations to critical thinking educational practices in post-secondary educational institutions (Dominguez 2018b), developed a course on critical thinking education for university teachers (Dominguez 2018c) and proposed in response to identified gaps between expectations and practices an “educational protocol” that post-secondary educational institutions in Europe could use to develop critical thinking (Elen et al. 2019).

Copyright © 2022 by David Hitchcock < hitchckd @ mcmaster . ca >

- Accessibility

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2024 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

- Français

- No results found.

- Preparatory

Lesson Explainer: Benefits of Philosophical Thinking Philosophy • First Year of Secondary School

In this explainer, we will learn how to recognize the benefits of philosophical thinking.

- Philosophical thinking has numerous benefits, for both the individual and society.

Philosophical thinking can enable us to develop our own worldview. A worldview is a system of beliefs and attitudes that shapes the way a person perceives, understands, and lives in the world.

Key Term: Worldview

A worldview is a system of beliefs and attitudes that shapes the way a person perceives and understands the world.

For example, suppose your friend, Fares, tells you that your other friend, Dina, had a party and did not invite you. What you think about this bit of news may have a lot to do with your worldview.

If according to your worldview, humans are caring and generous by nature, you will probably assume that Dina had a good reason not to invite you to her party. Maybe she was planning activities that she knew you would not enjoy, or maybe she was trying to protect someone else’s feelings.

On the other hand, if according to your worldview, human nature is selfish and cruel, you may think that Dina did not have any admirable reasons not to invite you.

We all have worldviews, but they are not always coherent; sometimes, they are full of contradictions. Philosophy can help us to better understand our own minds and be more consistent.

Another benefit of philosophical thinking is critical thinking. Critical thinking involves providing reasons for what we believe and do and refusing to accept beliefs without examining them.

The ancient Greek philosopher Socrates emphasized the importance of critical examination when he said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.”

Key Term: Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is a type of thinking in which beliefs are not accepted unless they are examined.

You might be able to think of times that you have used critical thinking in everyday life.

For example, you can use critical thinking to understand the situation involving your friends Fares and Dina. You might think about whether Fares tends to tell the truth or whether it seems out of character for Dina not to want you at her party.

Critical thinking can help us avoid hasty judgments, unfounded beliefs, and habits or traditions that are not helpful or rational.

Example 1: Defining Critical Thinking

What does critical thinking mean?

- Refusing to accept beliefs without examining them

- Judging the behavior of others

- Assuming that other people are wrong

- Complaining about the food at a restaurant

Because critical thinking contains the word “critical,” it is easy to confuse it for holding negative beliefs about, or making negative statements regarding, the behavior and actions of other people.

However, “critical” does not refer to negative statements or beliefs.

In the sense of the term used in critical thinking, criticism means careful examination. It is for this reason that critical thinking means refusing to adopt beliefs without examination.

Therefore, the correct answer is A.

Philosophical thinking involves pursuing knowledge and searching for truth. This profound investigation is not limited, like the sciences, to the boundaries between subjects.

This means that the investigation of something like the origin and composition of the universe might lead to the investigation of another question entirely, such as the meaning of life.

On the other hand, a physicist studying the origin of the universe would avoid any question regarding the meaning of the universe. Questions like that would fall outside the boundaries of physics.

Example 2: Identifying Indications of Philosophical Thinking

What is the best indication that a person has taken up philosophy and the pursuit of truth?

- They only believe what they perceive with their own senses.

- They involve themselves in profound investigations.

- They suspend judgment on everything.

- They involve themselves in superficial investigations.

- They only believe what can be experimentally proven.

Philosophy and the pursuit of truth are investigations without any limits.

For that reason, someone who has taken up the pursuit of truth will not limit themselves to only believing what they can perceive with their own senses or what can be experimentally proven. That is because there are sources of truth other than what we perceive with our senses or prove in experiments.

They will not suspend judgment on everything because to suspend judgment would be to give up pursuing the truth.

Because philosophy and the pursuit of truth are investigations without any natural limit, they are not limited to superficial investigations, but involve profound investigations.

Therefore, the correct answer is B.

Philosophy allows us to understand our own values. Our values are what matters to us. They make the difference between what we consider good and bad, and they are reflected in what we consider worth doing with our lives.

Suppose you choose to join a junior football team. There are many values that could be behind that choice—it might be because you love the game or it might be because you want to exercise, make friends, or please your parents. It might be some combination of these.

Many values could be expressed by the choice to join a sports team.

By giving us ways to examine our values, philosophy helps us to find meaning in our lives and live in harmony with ourselves.

Key Term: Values

Our values are what matters to us. They make the difference between what we consider good and bad, and they are reflected in what we consider worth doing with our lives.

The philosophical examination of values also plays a vital role in the progress of human societies.

Different societies promote different values. For example, capitalist societies encourage increasing wealth, whereas religious societies often encourage faith and the avoidance of sin.

Philosophical thinking involves the evaluation, criticism, and defense of the values held by a particular society.

For example, the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates asked his friends to explain what they meant by one of the values that the ancient Greek society held highest: justice.

His friend Polemarchus defined justice as helping one’s friends and harming one’s enemies. However, Socrates showed him and his friends that this definition was not adequate. How could it be just to help a friend who is themself unjust or harm a just enemy?

In this way, Socrates showed the need for his friends to revise their understanding of justice.

Example 3: Recalling Socrates’s Criticism of Values

Why did Socrates keep questioning his friends about justice?

- He loved asking meaningless questions.

- He knew asking questions would make him look smart.

- He wanted to make his friends look like fools.

- He was a sophist.

- He wanted to find the true meaning of justice.

Socrates wanted to provoke his friends to examine their own values.

He believed that this kind of examination is necessary because we often accept the values that we are taught without thinking about what they really mean.

Instead of unthinkingly accepting taught values, Socrates encouraged people to critically examine them in order to understand their true meaning.

Therefore, the correct answer is E.

- Sometimes, philosophers also introduce new values into society.

For example, John Locke and other seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English philosophers helped to develop the ideas of liberalism. Liberalism is the idea that individual rights and freedoms, including freedom of speech and freedom of religion, should not be limited by any government.

These philosophers introduced a new social value—freedom—that was crucial in providing the justification for the American and French revolutions.

The relationship between philosophers and the societies that they live in is a complex one. Philosophers have an impact on society, as we can see in the example of liberalism. At the same time, the social context in which philosophers live has an effect on their philosophy.

For example, it was because the ancient Greek society considered justice one of its highest values that this is the value that Socrates chose to question his friends about.

What values does our society place highest today? They may not be the same values that the ancient Greeks considered highest. When society’s values change over time, philosophers can help us reconcile newer values with the older ones we inherit.

Let’s summarize some of the key points we have covered in this explainer.

- Philosophical thinking can enable us to develop our own worldview.

- Philosophy involves thinking critically.

- Philosophical thinking involves pursuing knowledge and searching for truth.

- Philosophy allows us to understand our own values.

- Philosophical thinking involves the evaluation, criticism, and defense of the values that a particular society holds.

- This philosophical examination of values plays a vital role in the progress of human societies.

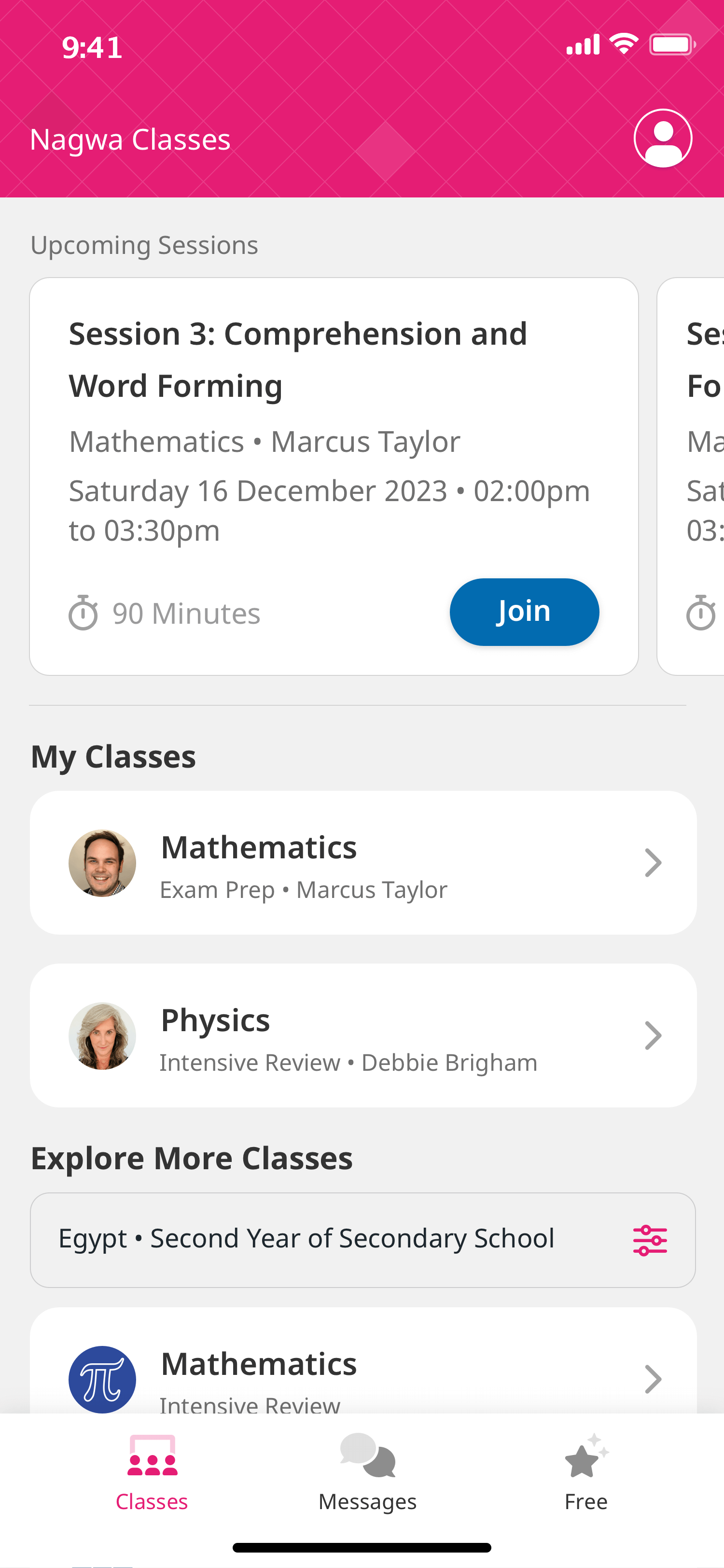

Join Nagwa Classes

Attend live sessions on Nagwa Classes to boost your learning with guidance and advice from an expert teacher!

- Interactive Sessions

- Chat & Messaging

- Realistic Exam Questions

- macOS Apple Silicon

- macOS Intel

Nagwa uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Learn more about our Privacy Policy

2.2 Overcoming Cognitive Biases and Engaging in Critical Reflection

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Label the conditions that make critical thinking possible.

- Classify and describe cognitive biases.

- Apply critical reflection strategies to resist cognitive biases.

To resist the potential pitfalls of cognitive biases, we have taken some time to recognize why we fall prey to them. Now we need to understand how to resist easy, automatic, and error-prone thinking in favor of more reflective, critical thinking.

Critical Reflection and Metacognition

To promote good critical thinking, put yourself in a frame of mind that allows critical reflection. Recall from the previous section that rational thinking requires effort and takes longer. However, it will likely result in more accurate thinking and decision-making. As a result, reflective thought can be a valuable tool in correcting cognitive biases. The critical aspect of critical reflection involves a willingness to be skeptical of your own beliefs, your gut reactions, and your intuitions. Additionally, the critical aspect engages in a more analytic approach to the problem or situation you are considering. You should assess the facts, consider the evidence, try to employ logic, and resist the quick, immediate, and likely conclusion you want to draw. By reflecting critically on your own thinking, you can become aware of the natural tendency for your mind to slide into mental shortcuts.

This process of critical reflection is often called metacognition in the literature of pedagogy and psychology. Metacognition means thinking about thinking and involves the kind of self-awareness that engages higher-order thinking skills. Cognition, or the way we typically engage with the world around us, is first-order thinking, while metacognition is higher-order thinking. From a metacognitive frame, we can critically assess our thought process, become skeptical of our gut reactions and intuitions, and reconsider our cognitive tendencies and biases.

To improve metacognition and critical reflection, we need to encourage the kind of self-aware, conscious, and effortful attention that may feel unnatural and may be tiring. Typical activities associated with metacognition include checking, planning, selecting, inferring, self-interrogating, interpreting an ongoing experience, and making judgments about what one does and does not know (Hackner, Dunlosky, and Graesser 1998). By practicing metacognitive behaviors, you are preparing yourself to engage in the kind of rational, abstract thought that will be required for philosophy.

Good study habits, including managing your workspace, giving yourself plenty of time, and working through a checklist, can promote metacognition. When you feel stressed out or pressed for time, you are more likely to make quick decisions that lead to error. Stress and lack of time also discourage critical reflection because they rob your brain of the resources necessary to engage in rational, attention-filled thought. By contrast, when you relax and give yourself time to think through problems, you will be clearer, more thoughtful, and less likely to rush to the first conclusion that leaps to mind. Similarly, background noise, distracting activity, and interruptions will prevent you from paying attention. You can use this checklist to try to encourage metacognition when you study:

- Check your work.

- Plan ahead.

- Select the most useful material.

- Infer from your past grades to focus on what you need to study.

- Ask yourself how well you understand the concepts.

- Check your weaknesses.

- Assess whether you are following the arguments and claims you are working on.

Cognitive Biases

In this section, we will examine some of the most common cognitive biases so that you can be aware of traps in thought that can lead you astray. Cognitive biases are closely related to informal fallacies. Both fallacies and biases provide examples of the ways we make errors in reasoning.

Connections

See the chapter on logic and reasoning for an in-depth exploration of informal fallacies.

Watch the video to orient yourself before reading the text that follows.

Cognitive Biases 101, with Peter Bauman

Confirmation bias.

One of the most common cognitive biases is confirmation bias , which is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information that confirms or supports your prior beliefs. Like all cognitive biases, confirmation bias serves an important function. For instance, one of the most reliable forms of confirmation bias is the belief in our shared reality. Suppose it is raining. When you first hear the patter of raindrops on your roof or window, you may think it is raining. You then look for additional signs to confirm your conclusion, and when you look out the window, you see rain falling and puddles of water accumulating. Most likely, you will not be looking for irrelevant or contradictory information. You will be looking for information that confirms your belief that it is raining. Thus, you can see how confirmation bias—based on the idea that the world does not change dramatically over time—is an important tool for navigating in our environment.

Unfortunately, as with most heuristics, we tend to apply this sort of thinking inappropriately. One example that has recently received a lot of attention is the way in which confirmation bias has increased political polarization. When searching for information on the internet about an event or topic, most people look for information that confirms their prior beliefs rather than what undercuts them. The pervasive presence of social media in our lives is exacerbating the effects of confirmation bias since the computer algorithms used by social media platforms steer people toward content that reinforces their current beliefs and predispositions. These multimedia tools are especially problematic when our beliefs are incorrect (for example, they contradict scientific knowledge) or antisocial (for example, they support violent or illegal behavior). Thus, social media and the internet have created a situation in which confirmation bias can be “turbocharged” in ways that are destructive for society.

Confirmation bias is a result of the brain’s limited ability to process information. Peter Wason (1960) conducted early experiments identifying this kind of bias. He asked subjects to identify the rule that applies to a sequence of numbers—for instance, 2, 4, 8. Subjects were told to generate examples to test their hypothesis. What he found is that once a subject settled on a particular hypothesis, they were much more likely to select examples that confirmed their hypothesis rather than negated it. As a result, they were unable to identify the real rule (any ascending sequence of numbers) and failed to “falsify” their initial assumptions. Falsification is an important tool in the scientist’s toolkit when they are testing hypotheses and is an effective way to avoid confirmation bias.

In philosophy, you will be presented with different arguments on issues, such as the nature of the mind or the best way to act in a given situation. You should take your time to reason through these issues carefully and consider alternative views. What you believe to be the case may be right, but you may also fall into the trap of confirmation bias, seeing confirming evidence as better and more convincing than evidence that calls your beliefs into question.

Anchoring Bias

Confirmation bias is closely related to another bias known as anchoring. Anchoring bias refers to our tendency to rely on initial values, prices, or quantities when estimating the actual value, price, or quantity of something. If you are presented with a quantity, even if that number is clearly arbitrary, you will have a hard discounting it in your subsequent calculations; the initial value “anchors” subsequent estimates. For instance, Tversky and Kahneman (1974) reported an experiment in which subjects were asked to estimate the number of African nations in the United Nations. First, the experimenters spun a wheel of fortune in front of the subjects that produced a random number between 0 and 100. Let’s say the wheel landed on 79. Subjects were asked whether the number of nations was higher or lower than the random number. Subjects were then asked to estimate the real number of nations. Even though the initial anchoring value was random, people in the study found it difficult to deviate far from that number. For subjects receiving an initial value of 10, the median estimate of nations was 25, while for subjects receiving an initial value of 65, the median estimate was 45.

In the same paper, Tversky and Kahneman described the way that anchoring bias interferes with statistical reasoning. In a number of scenarios, subjects made irrational judgments about statistics because of the way the question was phrased (i.e., they were tricked when an anchor was inserted into the question). Instead of expending the cognitive energy needed to solve the statistical problem, subjects were much more likely to “go with their gut,” or think intuitively. That type of reasoning generates anchoring bias. When you do philosophy, you will be confronted with some formal and abstract problems that will challenge you to engage in thinking that feels difficult and unnatural. Resist the urge to latch on to the first thought that jumps into your head, and try to think the problem through with all the cognitive resources at your disposal.

Availability Heuristic

The availability heuristic refers to the tendency to evaluate new information based on the most recent or most easily recalled examples. The availability heuristic occurs when people take easily remembered instances as being more representative than they objectively are (i.e., based on statistical probabilities). In very simple situations, the availability of instances is a good guide to judgments. Suppose you are wondering whether you should plan for rain. It may make sense to anticipate rain if it has been raining a lot in the last few days since weather patterns tend to linger in most climates. More generally, scenarios that are well-known to us, dramatic, recent, or easy to imagine are more available for retrieval from memory. Therefore, if we easily remember an instance or scenario, we may incorrectly think that the chances are high that the scenario will be repeated. For instance, people in the United States estimate the probability of dying by violent crime or terrorism much more highly than they ought to. In fact, these are extremely rare occurrences compared to death by heart disease, cancer, or car accidents. But stories of violent crime and terrorism are prominent in the news media and fiction. Because these vivid stories are dramatic and easily recalled, we have a skewed view of how frequently violent crime occurs.

Another more loosely defined category of cognitive bias is the tendency for human beings to align themselves with groups with whom they share values and practices. The tendency toward tribalism is an evolutionary advantage for social creatures like human beings. By forming groups to share knowledge and distribute work, we are much more likely to survive. Not surprisingly, human beings with pro-social behaviors persist in the population at higher rates than human beings with antisocial tendencies. Pro-social behaviors, however, go beyond wanting to communicate and align ourselves with other human beings; we also tend to see outsiders as a threat. As a result, tribalistic tendencies both reinforce allegiances among in-group members and increase animosity toward out-group members.

Tribal thinking makes it hard for us to objectively evaluate information that either aligns with or contradicts the beliefs held by our group or tribe. This effect can be demonstrated even when in-group membership is not real or is based on some superficial feature of the person—for instance, the way they look or an article of clothing they are wearing. A related bias is called the bandwagon fallacy . The bandwagon fallacy can lead you to conclude that you ought to do something or believe something because many other people do or believe the same thing. While other people can provide guidance, they are not always reliable. Furthermore, just because many people believe something doesn’t make it true. Watch the video below to improve your “tribal literacy” and understand the dangers of this type of thinking.

The Dangers of Tribalism, Kevin deLaplante

Sunk cost fallacy.

Sunk costs refer to the time, energy, money, or other costs that have been paid in the past. These costs are “sunk” because they cannot be recovered. The sunk cost fallacy is thinking that attaches a value to things in which you have already invested resources that is greater than the value those things have today. Human beings have a natural tendency to hang on to whatever they invest in and are loath to give something up even after it has been proven to be a liability. For example, a person may have sunk a lot of money into a business over time, and the business may clearly be failing. Nonetheless, the businessperson will be reluctant to close shop or sell the business because of the time, money, and emotional energy they have spent on the venture. This is the behavior of “throwing good money after bad” by continuing to irrationally invest in something that has lost its worth because of emotional attachment to the failed enterprise. People will engage in this kind of behavior in all kinds of situations and may continue a friendship, a job, or a marriage for the same reason—they don’t want to lose their investment even when they are clearly headed for failure and ought to cut their losses.

A similar type of faulty reasoning leads to the gambler’s fallacy , in which a person reasons that future chance events will be more likely if they have not happened recently. For instance, if I flip a coin many times in a row, I may get a string of heads. But even if I flip several heads in a row, that does not make it more likely I will flip tails on the next coin flip. Each coin flip is statistically independent, and there is an equal chance of turning up heads or tails. The gambler, like the reasoner from sunk costs, is tied to the past when they should be reasoning about the present and future.

There are important social and evolutionary purposes for past-looking thinking. Sunk-cost thinking keeps parents engaged in the growth and development of their children after they are born. Sunk-cost thinking builds loyalty and affection among friends and family. More generally, a commitment to sunk costs encourages us to engage in long-term projects, and this type of thinking has the evolutionary purpose of fostering culture and community. Nevertheless, it is important to periodically reevaluate our investments in both people and things.

In recent ethical scholarship, there is some debate about how to assess the sunk costs of moral decisions. Consider the case of war. Just-war theory dictates that wars may be justified in cases where the harm imposed on the adversary is proportional to the good gained by the act of defense or deterrence. It may be that, at the start of the war, those costs seemed proportional. But after the war has dragged on for some time, it may seem that the objective cannot be obtained without a greater quantity of harm than had been initially imagined. Should the evaluation of whether a war is justified estimate the total amount of harm done or prospective harm that will be done going forward (Lazar 2018)? Such questions do not have easy answers.

Table 2.1 summarizes these common cognitive biases.

| Bias | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Confirmation bias | The tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information that confirms or supports prior beliefs | As part of their morning routine, a person scans news headlines on the internet and chooses to read only those stories that confirm views they already hold. |

| Anchoring bias | The tendency to rely on initial values, prices, or quantities when estimating the actual value, price, or quantity of something | When supplied with a random number and then asked to provide a number estimate in response to a question, people supply a number close to the random number they were initially given. |

| Availability heuristic | The tendency to evaluate new information based on the most recent or most easily recalled examples | People in the United States overestimate the probability of dying in a criminal attack, since these types of stories are easy to vividly recall. |

| Tribalism | The tendency for human beings to align themselves with groups with whom they share values and practices | People with a strong commitment to one political party often struggle to objectively evaluate the political positions of those who are members of the opposing party. |

| Bandwagon fallacy | The tendency to do something or believe something because many other people do or believe the same thing | Advertisers often rely on the bandwagon fallacy, attempting to create the impression that “everyone” is buying a new product, in order to inspire others to buy it. |

| Sunk cost fallacy | The tendency to attach a value to things in which resources have been invested that is greater than the value those things actually have | A business person continues to invest money in a failing venture, “throwing good money after bad.” |