An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Narcissistic personality disorder.

Paroma Mitra ; Tyler J. Torrico ; Dimy Fluyau .

Affiliations

Last Update: March 1, 2024 .

- Continuing Education Activity

Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) is a complex psychological condition that presents with a pervasive pattern of grandiosity, need for admiration, and lack of empathy. NPD can cause significant social and occupational impairment and often has complications of comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders. This course discussion explores the historical evolution of the concept of narcissism, as well as the etiology, assessment, and treatment of NPD.

Structured within the context of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and its cluster-based classification, this activity navigates through Cluster B personality disorders, emphasizing the distinct characteristics shared among disorders like NPD, antisocial personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, and histrionic personality disorder. The session also critically examines the limitations of the DSM's clustering framework in effectively capturing the multifaceted nature of personality disorders. The integration of an interprofessional team is underscored, emphasizing a comprehensive approach to evaluation and treatment, aiming to mitigate the significant social and occupational impairments linked with NPD. The scarcity of effective treatment options for NPD is addressed, emphasizing the importance of early recognition and collaborative interventions for improved patient outcomes in the face of this challenging condition.

- Implement the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders diagnostic criteria for narcissistic personality disorder (NPD).

- Assess temperament and its specific characteristics in NPD.

- Determine the common history and mental status examination findings for a patient with NPD.

- Collaborate with the interprofessional team to enhance clinical outcomes for patients with NPD.

- Introduction

Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) is a pervasive pattern of grandiosity, a need for admiration, a lack of empathy, and a heightened sense of self-importance. Individuals with NPD may present to others as boastful, arrogant, or even unlikeable. [1] NPD is a pattern of behavior persisting over a long period and through a variety of situations or social contexts and can result in significant impairment in social and occupational functioning. [2] Additionally, NPD is often comorbid with other psychiatric illnesses, which may further worsen independent functioning. Unfortunately, treatment modalities for NPD are limited in both availability and efficacy. [1]

The term narcissism was first described by the Roman poet Ovid in his work Metamorphoses: Book III . This myth centers around Narcissus, a character cursed to fall in love with his reflection. However, it was not until the late 1800s that narcissism was used to define a psychological mind state.

The psychologist Havelock Ellis first used the term narcissism in 1898 to link the description of Narcissus to behaviors he observed in his patient. [3] Shortly after, Sigmund Freud labeled "narcissistic libido" in his book Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality . [4] Psychoanalyst Ernest Jones described narcissism as a character flaw. [5] In 1925, Robert Waelder published the first case report of pathological narcissism and described it as "narcissistic personality." [6] Despite these developments, NPD was not included in the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-I). It was not until 1968, during the era of the second edition of the DSM (DSM-II), that Heinz Kohut termed narcissism. [7]

In the DSM, personality disorders have been categorized into clusters based on shared characteristics; this model persists into the current DSM (fifth edition, text review) (DSM-5-TR). This categorization includes cluster A, cluster B, and cluster C personality disorders.

- Cluster A: Personality disorders with odd or eccentric characteristics, including paranoid personality disorder, schizoid personality disorder, and schizotypal personality disorder

- Cluster B: Personality disorders with dramatic, emotional, or erratic features, including antisocial personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, histrionic personality disorder, and narcissistic personality disorder

- Cluster C: Personality disorders with anxious and fearful characteristics, including avoidant personality disorder, dependent personality disorder, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder

Despite the historical context of using the cluster system, there are limitations when approaching personality disorders in this manner, and it is not consistently validated in the literature. [8]

There are very limited investigations and understandings of the etiology of NPD. A few behavioral genetic studies have demonstrated that NPD (and other cluster B personality disorders) is highly heritable. [9] [10] Medical conditions are often associated with personality disorders or personality changes, specifically including those with pathology that may damage neurons. This includes but is not limited to head trauma, cerebrovascular diseases, cerebral tumors, epilepsy, Huntington disease, multiple sclerosis, endocrine disorders, heavy metal poisoning, neurosyphilis, and AIDS. [11]

Psychoanalytic factors contribute to the development of personality traits and disorders; however, narcissistic qualities are not implicity pathological, as narcissistic traits are a normal part of human development. Narcissism manifests around age 8, increases in adolescence, and decreases in adulthood. [12] Still, individuals with a high degree of narcissism early in life tend to maintain a high degree of narcissism in later years. [13]

Psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich described "character armor" as defense mechanisms that develop with personality types to relieve cognitive conflict from internal impulses and interpersonal anxiety (eg, those with narcissistic tendencies have fantasy, projection defense, and splitting mechanisms). [14] Negative developmental experiences such as being rejected as a child and ego fragility during early childhood may contribute to the development of NPD in adulthood. [15] In contrast, excessive praise in childhood, including the belief that a child may have extraordinary abilities, may also develop into a lifetime need for constant praise and admiration. [16]

Personality is a complex summation of biological, psychological, social, and developmental factors; therefore, each personality is unique, even amongst those labeled with a personality disorder. Personality is a pattern of behaviors that an individual adapts uniquely to address constantly changing internal and external stimuli. This is more broadly described as temperament, which is a heritable and innate psychobiological characteristic. [17] [18] However, temperament is further shaped through epigenetic mechanisms, namely through life experiences such as trauma and socioeconomic conditions, referred to as adaptive etiological factors in personality development. [19] [20] Temperament traits include harm avoidance, novelty seeking, reward dependence, and persistence.

Harm Avoidance

Harm avoidance involves a bias towards inhibiting behavior that would result in punishment or nonreward. [21] Individuals with NPD have relatively low harm avoidance; instead, they may act in general disregard for the consequences of their actions or view the potential gain from risky behavior as far outweighing the gamble of any potential harm that may result. Further, individuals with NPD are generally outgoing and have few social inhibitions.

Novelty Seeking

Novelty seeking describes an inherent desire to initiate novel activities likely to produce a reward signal. [22] Individuals with NPD have moderate-to-high novelty-seeking behaviors. They tend to be hot-tempered and social; some are thrill-seeking.

Reward Dependence

Reward dependence describes the amount of desire to cater to behaviors in response to social reward cues. [23] Individuals with NPD have high reward dependence, to the point of demanding praise when completing tasks or forming new relationships. Individuals with NPD try to be social but for the sake of receiving praise or being seen in association with others of high status, which provides them with internal reward and validation.

Persistence

Persistence describes the ability to maintain behaviors despite frustration, fatigue, and limited reinforcement. Interestingly, individuals with NPD are quite persistent, with an extreme desire to seek out a reward. They will persist in certain behaviors; however, this is generally one of their most major maladaptive traits, particularly when combined with their tendency for low harm avoidance. These individuals strive for higher accomplishments and social status worthy of praise. [23]

- Epidemiology

There are significant challenges in diagnosing NPD, as these individuals may not often present for psychiatric evaluation. High-quality and multipopulation measures are lacking. Prevalence rates from United States community samples have been estimated from 0% to 6.2% of the population. [24] Interviews of 34,653 adults who participated in the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions revealed a lifetime prevalence for NPD of 6.2% (7.7% for men, 4.8% for women). [2]

- Pathophysiology

There are limited investigations for neuroimaging in persons diagnosed with NPD. A voxel-based morphometry (VBM) study conducted in Germany with a small sample size showed gray matter decreased volumes in the prefrontal and insular regions. [25] Another voxel-based morphometry and diffuse tensor imaging study showed grey matter reduction in the right prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices. [26] Notably, these brain regions are associated with empathy, compassion, cognition, and emotional regulation processing.

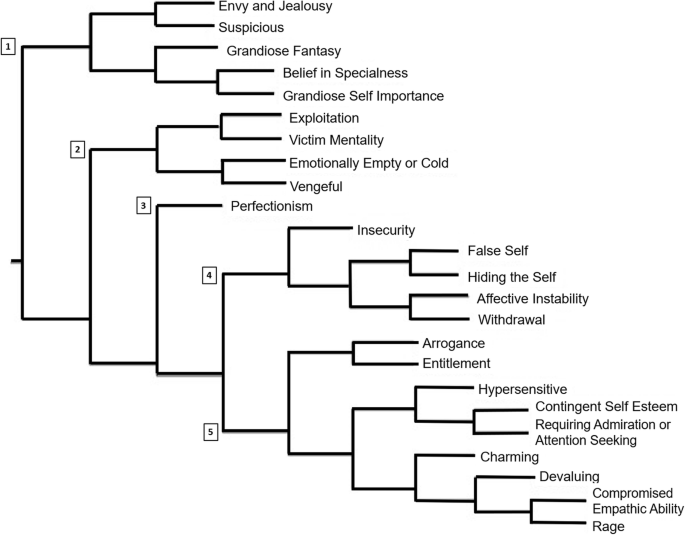

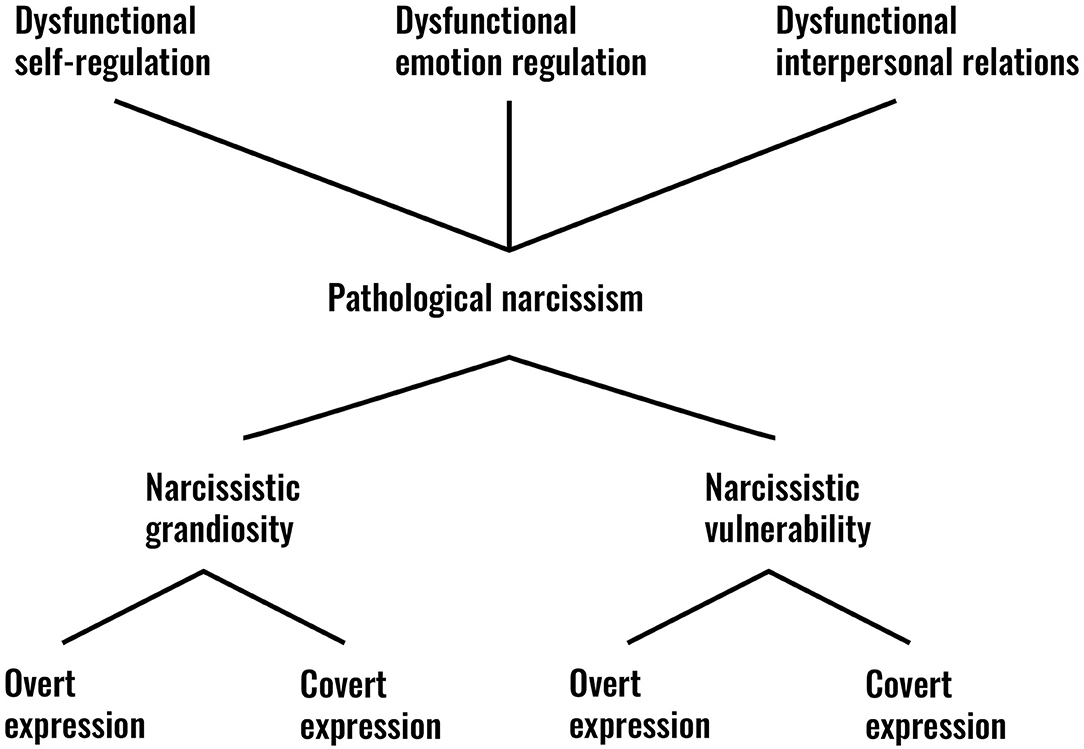

There is also a limited understanding of the psychological pathology in NPD. There are 2 proposed subtypes of NP: grandiose NPD and vulnerable NPD. [27] The grandiose subtype includes overt grandiosity, aggression, a profound lack of empathy, exploitation, and boldness. The vulnerable subtype presents with hypersensitivity and defensiveness and may be overlooked; these individuals may be more susceptible to affective disorders due to a fragile ego. [28]

- History and Physical

The presentation of NPD is highly variable. Persons with NPD generally speak from a place of self-importance and may demand or expect special treatment. In the clinical setting, amongst physicians, managers, and other high-ranking professionals, a patient with NPD may present as friendly while simultaneously presenting as cruel and bitter towards other staff not viewed as high-ranking. They may try to brag about their credentials and friends they view as having high status (ie, name-dropping). They are generally unable to handle criticism from peers or staff and frequently become enraged. [29] [30]

The clinical history is likely to reveal tumultuous relationships. Often, these individuals become increasingly isolated as they grow older due to others having difficulty maintaining their friendships with those who suffer from severe NPD. Additionally, legal charges are often present in the clinical history, as individuals with NPD have difficulty following rules (or believing rules apply to them). [30] Descriptions of empathy are limited when discussing failed relationships. Although many individuals with NPD deny feelings of depression or any signs of perceived weakness, they often suffer symptoms of depression due to an underlying fragile ego perpetuated by socio-occupational impairment from their maladaptive behaviors. [31]

The mental status examination is completed in psychiatric evaluations and varies amongst each case of NPD. Still, the following areas should be carefully considered in the psychiatric evaluation of NPD. [32]

- Appearance: The clinician should note the patient's general grooming and fashion choices. Clothing, accessories, hairstyles, or tattoos that are provoking may suggest NPD, as there is a sense of grandiosity and attention-seeking behavior characteristic of the disorder.

- Behavior: The clinician should monitor for disinhibited behaviors, grandiose postures, smirking, and scoffing. The context of the patient's cooperation should be paid particular attention to, as it may vary greatly depending on who the individual interacts with (depending on their perceived status).

- Speech: NPD may present with an increased amount of speech due to feelings of needing to prove oneself or brag about achievements and friendships, but there are no expected concerns with speech initiation, volume, or vocabulary.

- Affect: Affect is highly variable but may fluctuate greatly depending on the conversation topic, particularly if the patient with NPD feels challenged or threatened by the interviewer. More lability is expected than usual, with more frequent irritability.

- Thought content: It is essential to assess for delusions in patients with NPD. The level of grandiose thought may border between nondelusional grandiose thoughts and delusional (psychotic) grandiose thoughts. Although this distinction does not impact the treatment plan, it does help the clinician assess the severity of NPD.

- Thought process: The thought process in NPD is generally concrete, with grandiosity being unchallengeable. Still, individuals with NPD have the capability for linear and logical thought, often used to achieve their initial accomplishments (higher education, careers, relationships of status).

- Cognition: General cognition and orientation are not expected to be impaired in NPD but should be evaluated to rule out other psychiatric conditions.

- Insight: NPD is an egosyntonic disorder; therefore, a patient's understanding of their NPD is generally poor. Accepting self-deficit is usually not congruent with NPD.

- Judgment: The severity of NPD will impact a patient's judgment. This can often be assessed by inquiring of the patient's legal and relationship histories.

- Impulse control: The underlying temperament of NPD is classic for high reward dependence and low harm avoidance behaviors, which generally results in poor impulse control. This can also be assessed by inquiring about past legal and relationship history.

Diagnosis of a personality disorder benefits from longitudinal observation of a patient's behaviors over various circumstances to give a broader understanding of long-term functioning. Because many personality disorder features overlap with symptoms during another acute psychiatric condition, personality disorders should generally be diagnosed when no acute psychiatric process is concurrently occurring. [33] However, this is not always possible or required, as in the cases of an underlying personality disorder contributing significantly to hospitalizations or relapse of another psychiatric condition (ie, major depressive episode). [34] Still, it may take several visits with a patient to finally establish a firm diagnosis of NPD.

Patients with cluster B personality disorders often display transference, which is a projection of their prior conflicts onto the clinician. Clinicians often develop counter-transference, which is when the clinician projects unresolved conflicts onto the patient. This frequently occurs due to the nature of the patient encounters for individuals who have personality disorders, as they may be aggressive, unreasonable to logic, or rude. [35]

Clinicians must recognize signs of counter-transference when they occur to remove any treatment bias that may impact the clinical care of a patient with NPD. [36] Sublimation is a psychological defense mechanism that helps individuals transform unwanted or unhelpful impulses into less harmful or helpful ones. When clinicians begin to feel frustrated with patients who may be suffering from a personality disorder, it is useful (when possible) to sublimate the negative feelings of counter-transference and use those feelings instead as an evaluation tool to guide the differential diagnosis towards a personality disorder, which may ultimately direct the treatment plan. [37]

Various structured interviews and inventories have been developed to assist in evaluating NPD. Otto Kernberg's structured clinical interview, created in 1981, has continued to undergo revisions and restructuring as a structured clinical interview for personality disorders. The current version is a semistructured diagnostic interview with questions about personality organization, defenses, object relations, and coping skills. This interview focuses on interpersonal relationships. The Personality Institute at the Weill Cornell Institute copyrights the current version. The interview is based on psychodynamic principles and is expected to be used by persons with previous training in psychoanalytical work. [38]

Other instruments may measure the severity of NPD, such as the five-factor narcissism inventory that looks at the 5 aspects of general personality. There are about 148 questions on the measure. [39] Another measure that may be useful is the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. [40] For formal diagnosis, the conglomerate of information provided by personal history, collateral information, mental status examination, and psychometric tools, individuals must meet the DSM-5-TR diagnostic criteria for NPD.

NPD DSM-5-TR Criteria

In interpersonal settings, there is a pervasive pattern of grandiosity, need for admiration, and lack of empathy. This pattern of behaviors onsets in early adulthood and persists through various contexts. Clinical features include at least 5 of the following:

- Having a grandiose sense of self-importance, such as exaggerating achievements and talents, expecting to be recognized as superior even without commensurate achievements

- Preoccupation with fantasies of success, power, beauty, and idealization

- Belief in being "special" and that they can only be understood by or associated with other high-status people (or institutions)

- Demanding excessive admiration

- Sense of entitlement

- Exploitation behaviors

- Lack of empathy

- Envy towards others or belief that others are envious of them

- Arrogant, haughty behaviors and attitudes [1]

- Treatment / Management

Individuals with NPD may not recognize their illness as it is generally egosyntonic. The presentation is commonly at the behest of a first-degree relative or friend. Typically, this occurs after maladaptive behaviors have created stress on another rather than internal distress from the individual with NPD. Therefore, assessing the treatment goals in each specific NPD case is essential. As NPD is unlikely to remit with or without treatment, the focus of therapy may be aimed at reducing interpersonal conflict and stabilizing psychosocial functioning. [41]

There is minimal evidence that pharmacotherapy helps treat NPD unless there is a comorbid psychiatric illness. There are no FDA-approved medications for the treatment of NPD [42] . Psychotherapy is likely the most preferable treatment for NPD despite there also being limited evidence for its efficacy. Transfered-focused therapy may have more success than other types of therapies. [43] [44] Case management can help assist patients with NPD in maintaining income, shelter, and connection to medical and mental health services, as well as assistance with other basic needs.

- Differential Diagnosis

NPD should be considered when a long-term pattern of rigid behaviors is observed over various internal and external stimuli. Many behaviors observed in NPD may overlap with symptoms of other psychiatric illnesses, so it is crucial to assess if NPD occurs in isolation or conjunction with another psychiatric condition. Grandiosity, irritability, and increased goal-directed activities are common symptoms of a manic or hypomanic episode in bipolar spectrum illness. However, there is no decreased need for sleep in isolated NPD. Additionally, manic and hypomanic episodes are acute episodes that are relatively short-lived and respond to medication treatment. In contrast, NPD is chronic and rigid and does not respond well to medication treatments. [27]

Other differential diagnoses include the other cluster B personality disorders, antisocial personality disorder, histrionic personality disorder, and borderline personality disorder. It bears mention that persons with NPD do not show overt signs of impulsivity and self-destructiveness associated with borderline personality disorder. [45] Similarly, apparent emotional responses are associated with histrionic personality disorder. NPD is most similar to antisocial personality disorder, with a lack of empathy and superficial charm. However, people with an antisocial personality disorder would show a lack of morals compared with people with NPD and have a past diagnosis of conduct disorder from adolescence. [46]

- Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

There is a generally limited understanding of NPD, with high-quality population studies lacking. Most of our current knowledge is based on small sample-size investigations, case reports, or case series. Additionally, there are significant limitations to the existing models for describing all personality disorders. The cluster system has been most commonly utilized due to its implementation in the DSM. Despite behavioral similarity patterns that have been best attempted to be classified into syndromes (personality disorders), the individual uniqueness of each personality remains a problem for the diagnosis and research into each specific personality disorder. [8]

Experts in personality disorders have suggested switching to a dimensional model of personality rather than a cluster model. The proposed dimensional models describe temperament, utilization of defense mechanisms, and identification of pathological personality traits. [47] Although the DSM-5 did not incorporate these recommendations due to the sudden radical change it would imply for clinical use, the paradigm will likely shift in the coming decades as further research solidifies in congruence with evolving clinical guidelines. This evolution is particularly evident as the DSM-5-TR incorporated this research into publication under the "emerging measures and models" section. Notably, in this section of the DSM-5-TR, some of the cluster model personality disorders have been removed, but NPD remains a named personality disorder.

Limited studies report and predict the outcome of NPD, although there is a consensus that the disorder usually lasts for life. [27] An investigation from DSM-III era criteria found that NPD was less likely to have long-term impairment of global functioning compared to schizoid, antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and avoidant personality disorders. [48] Ultimately, NPD is unlikely to resolve on its own or with treatment. Still, interventions to optimize quality of life, including reducing psychiatric comorbidity and stabilizing social factors, are likely to improve the prognosis of NPD. [42]

- Complications

Substance use disorders are common among personality disorders but with limited implications into which specific personality disorders pose the most risk for a particular substance use disorder. [49] Personality disorders have an increased likelihood of suicide and suicide attempts compared to those without personality disorders, and individuals with NPD should be screened for suicidal ideation regularly. [42] [50]

- Deterrence and Patient Education

The treatment of NPD is dependent on developing and maintaining therapeutic rapport, particularly as these individuals may be highly sensitive to any suggestions or advice. Patients are encouraged to vocalize symptoms they would like addressed or any psychosocial stressors a treatment team can alleviate, rather than clinicians focusing on reducing behaviors if the patient is not in clinical distress or if they do not have a socio-occupational impairment.

Further, patients are encouraged to utilize support networks through their remaining social relationships. Involving the patient's family is another way of monitoring for decompensation and providing education on how to deliver stable social factors for the patient. [42] Utilizing standardized assessments for quality of life may reveal ways to optimize the ability to function in significant areas of life for an individual with NPD. [51]

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and treatment of NPD is a complicated topic and is ultimately an area of psychiatric research that requires more study. As diagnostic and treatment models are shifting away from a cluster system and towards a dimensional model of personality, the implications that this will have on clinical practice will need close observation. Still, when a treatment team suspects NPD, a comprehensive history in conjunction with collateral information is recommended before formally diagnosing NPD. Including the patient's perspective and determining the appropriate goals of care for an individual with NPD is essential to prevent overmedicalization or iatrogenic harm to a patient who may not be suffering from any treatable symptoms. Collaboration with social workers, case managers, therapists, and family to optimize the social factors in a patient's life can offer stability to individuals with NPD.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Paroma Mitra declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Tyler Torrico declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Dimy Fluyau declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Mitra P, Torrico TJ, Fluyau D. Narcissistic Personality Disorder. [Updated 2024 Mar 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Validity aspects of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, narcissistic personality disorder construct. [Compr Psychiatry. 2011] Validity aspects of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, narcissistic personality disorder construct. Karterud S, Øien M, Pedersen G. Compr Psychiatry. 2011 Sep-Oct; 52(5):517-26. Epub 2010 Dec 28.

- Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV narcissistic personality disorder: results from the wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. [J Clin Psychiatry. 2008] Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV narcissistic personality disorder: results from the wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Smith SM, Ruan WJ, Pulay AJ, Saha TD, Pickering RP, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008 Jul; 69(7):1033-45.

- Clinical Characteristics of Comorbid Narcissistic Personality Disorder in Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder. [J Pers Disord. 2018] Clinical Characteristics of Comorbid Narcissistic Personality Disorder in Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder. Hörz-Sagstetter S, Diamond D, Clarkin JF, Levy KN, Rentrop M, Fischer-Kern M, Cain NM, Doering S. J Pers Disord. 2018 Aug; 32(4):562-575. Epub 2017 Jul 31.

- Review Empathy in narcissistic personality disorder: from clinical and empirical perspectives. [Personal Disord. 2014] Review Empathy in narcissistic personality disorder: from clinical and empirical perspectives. Baskin-Sommers A, Krusemark E, Ronningstam E. Personal Disord. 2014 Jul; 5(3):323-33. Epub 2014 Feb 10.

- Review Delay discounting and narcissism: A meta-analysis with implications for narcissistic personality disorder. [Personal Disord. 2022] Review Delay discounting and narcissism: A meta-analysis with implications for narcissistic personality disorder. Coleman SRM, Oliver AC, Klemperer EM, DeSarno MJ, Atwood GS, Higgins ST. Personal Disord. 2022 May; 13(3):210-220. Epub 2022 Jan 6.

Recent Activity

- Narcissistic Personality Disorder - StatPearls Narcissistic Personality Disorder - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Narcissism Driven by Insecurity, Not Grandiose Sense of Self, New Psychology Research Shows

Narcissism is driven by insecurity, and not an inflated sense of self, finds a new study, which offers a more detailed understanding of this long-examined phenomenon and may also explain what motivates the self-focused nature of social media activity.

Narcissism is driven by insecurity, and not an inflated sense of self, finds a new study by a team of psychology researchers. Its research, which offers a more detailed understanding of this long-examined phenomenon, may also explain what motivates the self-focused nature of social media activity.

“For a long time, it was unclear why narcissists engage in unpleasant behaviors, such as self-congratulation, as it actually makes others think less of them,” explains Pascal Wallisch, a clinical associate professor in both New York University’s Department of Psychology and Center for Data Science and the senior author of the paper , which appears in the journal Personality and Individual Differences . “This has become quite prevalent in the age of social media—a behavior that’s been coined ‘flexing’.

“Our work reveals that these narcissists are not grandiose, but rather insecure, and this is how they seem to cope with their insecurities.”

“More specifically, the results suggest that narcissism is better understood as a compensatory adaptation to overcome and cover up low self-worth,” adds Mary Kowalchyk, the paper’s lead author and an NYU graduate student at the time of the study. “Narcissists are insecure, and they cope with these insecurities by flexing. This makes others like them less in the long run, thus further aggravating their insecurities, which then leads to a vicious cycle of flexing behaviors.”

The survey’s nearly 300 participants—approximately 60 percent female and 40 percent male—had a median age of 20 and answered 151 questions via computer.

The researchers examined Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD), conceptualized as excessive self-love and consisting of two subtypes, known as grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. A related affliction, psychopathy, is also characterized by a grandiose sense of self. They sought to refine the understanding of how these conditions relate.

To do so, they designed a novel measure, called PRISN ( P erformative R efinement to soothe I nsecurities about S ophisticatio N ), which produced FLEX (per F ormative se L f- E levation inde X ). FLEX captures insecurity-driven self-conceptualizations that are manifested as impression management, leading to self-elevating tendencies.

The PRISN scale includes commonly used measures to investigate social desirability (“No matter who I am talking to I am a good listener”), self-esteem (“On the whole, I am satisfied with myself”), and psychopathy (“I tend to lack remorse”). FLEX was shown to be made up of four components: impression management (“I am likely to show off if I get the chance”), the need for social validation (“It matters that I am seen at important events''), self-elevation (“I have exquisite taste”), and social dominance (“I like knowing more than other people”).

Overall, the results showed high correlations between FLEX and narcissism—but not with psychopathy. For example, the need for social validation (a FLEX metric) correlated with the reported tendency to engage in performative self-elevation (a characteristic of vulnerable narcissism). By contrast, measures of psychopathy, such as elevated levels of self-esteem, showed low correlation levels with vulnerable narcissism, implying a lack of insecurity. These findings suggest that genuine narcissists are insecure and are best described by the vulnerable narcissism subtype, whereas grandiose narcissism might be better understood as a manifestation of psychopathy.

The paper’s other authors were Helena Palmieri, an NYU psychology doctoral student at the time of the study, and Elena Conte, an NYU psychology undergraduate student.

DOI: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110780

Press Contact

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Narcissistic personality disorder

Some features of narcissistic personality disorder are like those of other personality disorders. Also, it's possible to be diagnosed with more than one personality disorder at the same time. This can make diagnosis more challenging.

Diagnosis of narcissistic personality disorder usually is based on:

- Your symptoms and how they impact your life.

- A physical exam to make sure you don't have a physical problem causing your symptoms.

- A thorough psychological evaluation that may include filling out questionnaires.

- Guidelines in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association.

Treatment for narcissistic personality disorder is talk therapy, also called psychotherapy. Medicines may be included in your treatment if you have other mental health conditions, such as depression.

Psychotherapy

Narcissistic personality disorder treatment is centered around psychotherapy. Psychotherapy can help you:

- Learn to relate better with others so your relationships are closer, more enjoyable and more rewarding.

- Understand the causes of your emotions and what drives you to compete, to distrust others, and to dislike others and possibly yourself.

The focus is to help you accept responsibility and learn to

- Accept and maintain real personal relationships and work together with co-workers.

- Recognize and accept your actual abilities, skills and potential so you can tolerate criticism or failures.

- Increase your ability to understand and manage your feelings.

- Understand and learn how to handle issues related to your self-esteem.

- Learn to set and accept goals that you can reach instead of wanting goals that are not realistic.

Therapy can be short term to help you manage during times of stress or crisis. Therapy also can be provided on an ongoing basis to help you achieve and maintain your goals. Often, including family members or others in therapy can be helpful.

There are no medicines specifically used to treat narcissistic personality disorder. But if you have symptoms of depression, anxiety or other conditions, medicines such as antidepressants or anti-anxiety medicines may be helpful.

More Information

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

Lifestyle and home remedies

You may feel defensive about treatment or think it's unnecessary. The nature of narcissistic personality disorder also can leave you feeling that therapy is not worth your time and attention, and you may be tempted to quit. But it's important to:

- Keep an open mind. Focus on the rewards of treatment.

- Follow your treatment plan. Attend scheduled therapy sessions and take any medicines as directed. Remember, it can be hard work and you may have occasional setbacks.

- Get treatment for alcohol or drug misuse or other mental health problems. Addiction, depression, anxiety and stress can lead to a cycle of emotional pain and unhealthy behavior.

- Stay focused on your goals. Stay motivated by keeping your goals in mind and reminding yourself that you can work to repair damaged relationships and become more content with your life.

Preparing for your appointment

You may start by seeing your health care provider, or you may be referred you to a mental health provider, such as a psychiatrist or psychologist.

What you can do

Before your appointment, make a list of:

- Any symptoms you have and how long you've had them, to help determine what kinds of events are likely to make you feel angry or upset.

- Key personal information, including traumatic events in your past and any current major stressors.

- Your medical information, including other physical or mental health conditions you have.

- Any medicines, vitamins, herbs or other supplements you're taking, and the doses.

- Questions to ask your mental health provider so that you can make the most of your appointment.

Consider taking a trusted family member or friend along to help remember the details. In addition, someone who has known you for a long time may be able to ask helpful questions or share important information.

Some basic questions to ask your mental health provider include:

- What do you think may be causing my symptoms?

- What are the goals of treatment?

- What treatments are most likely to be effective for me?

- In what ways do you think my quality of life could improve with treatment?

- How often will I need therapy sessions, and for how long?

- Would family or group therapy be helpful in my case?

- Are there medicines that can help my symptoms?

- I have other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

- Are there any brochures or other printed materials that I can have? What websites do you recommend?

Don't hesitate to ask any other questions during your appointment.

What to expect from your mental health provider

To better understand your symptoms and how they're affecting your life, your mental health provider may ask:

- What are your symptoms?

- How do your symptoms affect your life, including school, work and personal relationships?

- How do you feel — and act — when others seem to criticize or reject you?

- Do you have any close personal relationships? If not, why do you think that is?

- What are your major accomplishments?

- What are your major goals for the future?

- How do you feel when someone needs your help?

- How do you feel when someone expresses difficult feelings, such as fear or sadness, to you?

- How would you describe your childhood, including your relationship with your parents?

- Have any of your close relatives been diagnosed with a mental health disorder, such as a personality disorder?

- Have you been treated for any other mental health problems? If yes, what treatments were most effective?

- Do you use alcohol or recreational drugs? If so, what do you use and how often?

- Are you currently being treated for any other medical conditions?

- Narcissistic personality disorder. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5-TR. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2022. https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org. Accessed Sept. 9, 2022.

- Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD). Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/psychiatric-disorders/personality-disorders/narcissistic-personality-disorder-npd. Accessed Sept. 8, 2022.

- Overview of personality disorders. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/psychiatric-disorders/personality-disorders/overview-of-personality-disorders#v25246292. Accessed Sept. 9, 2022.

- What are personality disorders. American Psychiatric Association. https://psychiatry.org/patients-families/personality-disorders/what-are-personality-disorders. Accessed Sept. 8, 2022.

- Lee RJ, et al. Narcissistic and borderline personality disorders: Relationship with oxidative stress. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2020; doi:10.1521/pedi.2020.34.supp.6.

- Fjermestad-Noll J, et al. Perfectionism, shame, and aggression in depressive patients with narcissistic personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorder. 2020; doi:10.1521/pedi.2020.34.supp.25.

- Maillard P, et al. Process of change in psychotherapy for narcissistic personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2020; doi:10.1521/pedi.2020.34.supp.63.

- Scrandis DA. Narcissistic personality disorder: Challenges and therapeutic alliance in primary care. The Nurse Practitioner. 2020; doi:10.1097/01.NPR.0000653968.96547.e7.

- Caligor E, et al. Narcissistic personality disorder: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Sept. 9, 2022.

- Caligor E, et al. Treatment of narcissistic personality disorder. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Sept. 9, 2022.

- Allen ND (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Sept. 27, 2022.

Associated Procedures

Products & services.

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 28 May 2024

Linking grandiose and vulnerable narcissism to managerial work performance, through the lens of core personality traits and social desirability

- Anna M. Dåderman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8562-5610 1 &

- Petri J. Kajonius ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0629-353X 1 , 2

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 12213 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

361 Accesses

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

- Risk factors

While grandiose narcissism is well-studied, vulnerable narcissism remains largely unexplored in the workplace context. Our study aimed to compare grandiose and vulnerable narcissism among managers and people from the general population. Within the managerial sample, our objective was to examine how these traits diverge concerning core personality traits and socially desirable responses. Furthermore, we endeavored to explore their associations with individual managerial performance, encompassing task performance, contextual performance, and counterproductive work behavior (CWB). Involving a pool of managerial participants ( N = 344), we found that compared to the general population, managers exhibited higher levels of grandiose narcissism and lower levels of vulnerable narcissism. While both narcissistic variants had a minimal correlation ( r = .02) with each other, they differentially predicted work performance. Notably, grandiose narcissism did not significantly predict any work performance dimension, whereas vulnerable narcissism, along with neuroticism, predicted higher CWB and lower task performance. Conscientiousness emerged as the strongest predictor of task performance. This study suggests that organizations might not benefit from managers with vulnerable narcissism. Understanding these distinct narcissistic variants offers insights into their impacts on managerial performance in work settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Effect of breathwork on stress and mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised-controlled trials

Ethics and discrimination in artificial intelligence-enabled recruitment practices

Introduction.

Our comprehension of the impact of vulnerable narcissism on leadership remains in its nascent stages, and this study aimed to establish a data-driven foundation for further understanding. This endeavor is crucial for empirically examining vulnerable narcissism within organizational contexts. Research on CEOs personality predominantly centers on grandiose narcissism 1 , 2 , 3 or core personality traits such as conscientiousness and neuroticism 4 , but not on vulnerable narcissism. Recent work by Miller et al. 5 underscores the current knowledge and gaps in our understanding of various narcissistic constructs, emphasizing the necessity for additional exploration of narcissistic vulnerability itself.

While extensive research exists on grandiose narcissism among managers, the focus on vulnerable narcissism in managerial roles remains scant. Our aim was to explore two variants of narcissism—grandiose and vulnerable—within managerial roles, comparing and contrasting these traits with those observed in the general population. Moreover, within the managerial sample, we aimed to investigate the divergent correlations between both forms of narcissism and core personality traits, alongside examining their correlations with socially desirable responding. Additionally, we aimed to explore the associations between both variants of narcissism and managerial performance, encompassing task performance, contextual performance, and counterproductive work behavior.

To our knowledge, comparative analyses between managers and the general population regarding the level of these two narcissistic variants are lacking. However, it is recognized that employees in senior leadership positions tend to exhibit elevated scores of narcissism, as evaluated both by self-ratings and ratings provided by their subordinates 6 . Are managers more prone to grandiose narcissism and less susceptible to vulnerability compared to the general population? Would we anticipate observing a comparable pattern of divergent correlations between these two narcissistic variants and core personality traits in a sample of managers as is typically observed in the general population?

The focal point of managerial research, applying intricate methodologies encompassing numerous scales, predominantly centers on task performance 7 , 8 . Conversely, less attention is allocated to exploring alternative facets of individual performance, such as contextual performance. Previous studies have primarily examined the grandiose variant of narcissism in relation to work performance, revealing that narcissistic managers often overestimate their performance 9 , which may be related to socially desirable responding. However, it remains unclear whether this overestimation extends to other form of performance, including contextual performance. It would be intriguing to explore whether vulnerable narcissism predicts counterproductive work behavior, potentially indicating a need to prioritize the recruitment of managers with lower levels of vulnerable narcissism.

Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism defined

Morf et al. 10 offered a comprehensive delineation of the background and historical context surrounding the construct of narcissism. They traced its origins back to early depictions by scholars such as Havelock Ellis and Freud, who characterized narcissistic individuals as those excessively preoccupied with self-investment and the preservation of their ego, often to the detriment of others. Morf et al. 10 described narcissism as “self-enhancer personality” (p. 399). According to Morf and Rhodewalt 11 persons with narcissism are full of paradoxes, characterized by self-aggrandizement and self-absorption, yet paradoxically susceptible to perceived threats and overly sensitive to feedback. They exhibit emotional volatility across a spectrum from euphoria to despair and rage, whether in the role of a friend, boss, or romantic partner. Despite their charm and social adeptness, they display a marked insensitivity towards the feelings, desires, and needs of others. Initial attraction to such personalities may be common, only to be overshadowed by exhaustion from their incessant cravings for admiration and attention.

Narcissism, when considered at more formal and heightened levels, is classified as a personality disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 12 (DSM-5; APA). However, it is crucial to note that this study focuses on narcissism as a personality trait rather than as a diagnosable disorder.

For the last few decades, the Dark Triad traits—narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy, representing three socially aversive personality traits as outlined by Paulhus and Williams 13 —have garnered considerable attention as a focal point in research. This study focuses on narcissism, often regarded as comparatively less socially aversive in the workplace compared to other traits within the Dark Triad. Narcissism is a personality trait characterized by an inflated sense of self-importance and a need for excessive admiration 11 . There are two, at least in nonclinical samples unrelated, main variants of narcissism: grandiose and vulnerable (see review by Jauk and Kanske 14 ). Grandiose narcissists exaggerate their abilities, are arrogant, and seek power, while vulnerable narcissists are insecure yet still feel important.

In addition to the entitled behavior often associated with the grandiose variant of narcissism, vulnerable narcissism manifests in hypersensitivity and anxiety 15 , 16 . It tends to correlate with deflated self-esteem, depression, anxiety, and a lack of concern for others’ needs. Unlike the grandiose variant, vulnerable narcissism is not linked theoretically or empirically to overt self-reporting, such as bragging about successful organizational behaviors in the past 17 , 18 . Displaying proactive behaviors at work stems from a drive for status and power within the organization, rather than the characteristics of vulnerable narcissism.

The dichotomy of narcissistic grandiosity in organizational environments

In organizational settings, grandiose narcissism exhibits a dual nature, correlating with outcomes that can be either advantageous or detrimental. Employees with grandiose narcissistic tendencies demonstrate elevated confidence levels, a strong inclination toward achievement, and a readiness to assume leadership roles. These traits, particularly confidence and assertiveness, often facilitate their selection for managerial positions 6 . Kaiser 19 outlined that an abundance of narcissistic traits is often perceived as highly detrimental within managerial positions. The literature highlights narcissistic leaders as penchant for exploiting others, making impulsive decisions, and engaging in unethical behavior adversely impacts relationships and team performance 20 , 21 . For instance, CEOs narcissism is positively related to the likelihood that an organization will be subjected to a lawsuit 22 , to the manipulation of the reported earnings 9 , to incurring significantly higher audit fees from external auditors 23 , and tending to be bold in their actions and often engage in substantial risk-taking so as to demonstrate their self-perceived superiority to others 24 , 25 . Moreover, research has identified a negative correlation between grandiose narcissism and crowdfunding success. Specifically, it suggests that the higher the level of narcissistic personality traits in an entrepreneur, the lower the likelihood of successfully funding their crowdfunding campaign 26 .

However, the literature also underscores that grandiose narcissism possesses a dual nature, with certain positive attributes. For instance, research indicates that narcissistic entrepreneurs tend to gravitate towards more innovative and risky venture opportunities 27 . Additionally, within entrepreneurial teams, higher levels of narcissism are linked to improved business planning performance 28 . Previous research indicates that narcissistic managers exhibit various favorable traits that yield tangible benefits for organizations. They often embody charismatic leadership qualities, effectively navigating organizations through crises 24 , 29 , 30 , strive for higher performance by stimulating innovation 31 , and fostering a heightened entrepreneurial spirit 32 . Recent studies, such as that by Böhm and Blickle 29 , suggest that narcissistic leaders, particularly those high in political skill, possess the self-discipline to regulate aggressive tendencies while skillfully presenting their desire for admiration, thereby garnering acceptance from subordinates.

Narcissistic CEOs often emerge as visionary leaders 30 , partly due to their consistently optimistic communication with stakeholders 33 . Their narcissism correlates positively with engagement in corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives 34 , 35 , likely driven by the desire to garner heightened admiration for both them and their organizations through increased CSR investment.

Individual work performance

Work performance involves behaviors relevant to organizational goals and differs from productivity, which focuses on tangible outcomes. An employee’s effectiveness doesn’t always translate into high productivity due to various contextual factors. Evaluating individual performance encompasses goal-centric attitudes and actions like goal setting, time management, skill acquisition, and professional development. This multidimensional concept prioritizes observable behaviors over outcomes and spans task performance, contextual behaviors, and counterproductive work behaviors 36 .

Task performance refers to meeting job expectations in quantity, quality, essential skills, and professional knowledge. It includes planning, problem-solving, accuracy, knowledge maintenance, goal setting, and timely goal achievement. Contextual performance, also known as organizational citizenship behavior, goes beyond duties, encompassing actions like taking on extra tasks, initiating projects, engaging in collaborations, offering advice, and showing enthusiasm. However, counterproductive work behaviors (CWB) harm an organization, including complaints, negativity, off-task behavior, presentism, intentional mistakes, misuse of privileges, and exaggerating challenges.

Limited research has explored how narcissism influences individual work performance dimensions 37 , 38 , 39 . In managerial positions, the examination of narcissism primarily has focused on its correlation with task performance 40 . This study also considered other trait-based resources like effective coping strategies. Vulnerable narcissists struggle with self-worth, leading to sensitivity to criticism, social withdrawal, and engaging in CWB. Grandiose narcissists exhibit inflated self-importance, seeking admiration, and might display arrogant or exploitative behaviors 41 . Surprisingly, despite their traits, grandiose narcissists are less inclined to engage in CWB. Theoretically, shaping a distinct dynamic in their work performance, neurotic, vulnerable narcissists could potentially engage in CWB; however, this relationship has yet to be explored.

Narcissists generally tend to exaggerate their knowledge and possess an inflated self-centered view 42 . This would facilitate correlating positively with self-reported performance ratings among managers. However, challenges persist in task performance studies, prompting further investigation into social desirability responding in self-reported work performance.

The role of core personality traits

One popular dimensional model of core personality traits is the Five Factor Model (FFM/Big Five) 43 , breaking down personality into five broad domains 44 : extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness. Another model is HEXACO model 45 , which in addition of the traits encompassing Big Five also reflects honesty-humility. The consideration of whether narcissism contributes to the prediction of individual work performance beyond the core personality traits holds significance for two main reasons. Firstly, the Big Five traits are widely acknowledged to cover a substantial portion of the personality domain, with several of these traits demonstrating predictive power for leadership 46 and work-related ratings 47 , 48 . The trait most strongly predictive of job performance and a significant predictor of leadership, conscientiousness, generally shows little association with narcissism 49 .

Secondly, narcissism itself shares variability with some of the core traits, raising concerns about conceptual overlap. Specifically, grandiose narcissism exhibits positive correlations with extraversion and negative correlations with agreeableness and neuroticism 50 . In contrast, vulnerable narcissism is positively associated with neuroticism 14 , 50 . Both variants share aspects of exploiting others, relating negatively to honesty-humility 51 . Consequently, while controlling for the core traits may not diminish the impact of narcissism notably, it remains essential to include these traits particularly in work-related analyses for understanding the power of personality 52 .

The current study

Our study’s first objective was to compare two variants of narcissism in managers and people from the general population. Theoretical underpinnings and empirical evidence, aligning the grandiose variant with extraversion and the vulnerable variant with neuroticism, were considered. Given the complexity of managerial roles, where grandiose traits tend toward dominance and vulnerability manifests as defensiveness and insecurity, the anticipation was that managers would exhibit higher levels of grandiose narcissism and lower levels of vulnerable narcissism compared to counterparts in the workplace and the general population 53 .

Our study’s second objective was, within the managerial sample, to investigate the divergent correlations between both forms of narcissism and core personality traits, alongside examining their correlations with socially desirable responding. Assuming universality of core personality traits in humans 54 , and considering personality theory and past research 15 , 38 , 39 , 50 , 55 , 56 , we expected grandiose narcissism to show a positive correlation with extraversion and a negative one with neuroticism and agreeableness, while vulnerable narcissism to be positively correlated with neuroticism and negatively with extraversion and agreeableness 57 . Previous studies 50 , 51 , 58 have shown no notable link between conscientiousness and either form of narcissism. Therefore, we do not anticipate a significant relationship between conscientiousness and narcissism in our study. Moreover, we expected both grandiose narcissism 29 , 37 , 55 , 59 and vulnerable narcissism 51 to have negative correlations with honesty-humility. Narcissistic grandiosity may correlate with diminished levels of honesty-humility due to a proclivity for exploiting others. Conversely, narcissistic vulnerability is associated with abusive (aggressive) supervision tendencies 60 . Leaders harboring a vulnerable self-concept might resort to aggression against their followers, driven by internal attributions of failure and feelings of shame.

Our study’s third objective was to explore the associations between both variants of narcissism and managerial performance, encompassing task performance, contextual performance, and counterproductive work behavior. Different relationships with core personality traits would have implications for managers’ self-reports of their individual work performance. Acknowledging the limitations of self-reported work performance, our study aimed to control for core personality traits and socially desirable responses in these reports, ensuring a more comprehensive investigation. For instance, Ramos-Villagrasa et al. 39 demonstrated that while grandiose narcissism moderately correlated with contextual performance, it showed no relation to task performance or CWB. Relationships between vulnerable narcissism and the three individual work performance dimensions among managers have not been previously explored.

We formulated the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

Managers, due to their role in leading others, were expected to demonstrate elevated levels of grandiose narcissism and decreased levels of vulnerable narcissism compared to persons in non-managerial roles.

Hypothesis 2

Grandiose narcissism would correlate positively with extraversion and negatively with agreeableness and neuroticism. It was also expected to exhibit a negative correlation with honesty-humility.

Vulnerable narcissism would correlate positively with neuroticism and negatively with extraversion and agreeableness. Similar to grandiose narcissism, it was anticipated to exhibit a negative correlation with honesty-humility.

It was not anticipated that conscientiousness would exhibit a significant correlation with either variant of narcissism.

Hypothesis 3

Grandiose narcissism, linked positively with extraversion, was predicted to be associated with higher levels of contextual performance in managerial roles.

Vulnerable narcissism, positively correlated with neuroticism, was expected to predict lower task performance and higher CWB among managers.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure.

The study involved 344 managers, 57.8% being women, employed in various sectors in Sweden. On average, they were 49 years old, with around five years of managerial experience in their current roles. The dataset comprised managers from nine distinct organizations, with 70% in human-oriented sectors and the remaining 30% in manufacturing industries with positions ranging from superior (19.4%), intermediate (68.6%), to lower levels like group leaders (12%). These managers worked across fields like industrial production, social services, nursing, care services, and education. They were employed by privately-owned companies (45%), or municipalities and state organizations (55%). Eight organizations were situated in western Sweden, with one privately-owned municipality situated in Stockholm.

The data for this study were gathered within a leadership-focused project led by the first author. They engaged Human Resources (HR) managers from both municipal and private sectors throughout western Sweden, extending invitations to managers within these organizations to partake in the study. The HR managers received comprehensive project information, including details about the questionnaires and their measurement criteria, alongside an ethics statement. Subsequently, they relayed this information to their organizations’ CEOs. Upon agreement to participate, the HR managers supplied mailing lists containing potential participants.

Managers were asked to complete a web-based questionnaire using Google Forms, a free Internet-based software. Given the anonymous nature of the survey, researchers were unaware of which managers had already responded. To ensure adequate participation, all managers on the mailing lists received three reminder emails. Data collection occurred over a five-week period.

The response rates from the participating organizations were satisfactory, averaging 73% with a range between 65 and 81%.

Instruments

Aware of managers’ time constraints for lengthy surveys on psychological measures 61 , we opted for abbreviated versions of self-report instruments. A high scale score indicates a high value of the measured variable. We kept all items within the utilized instruments, even though this action may have slightly reduced the reliability measured by the scales’ Cronbach's alpha. Our goal was to enable a direct comparison of mean scale scores with other sample data. Notably, two variables (grandiose narcissism and openness) contained a few items that impacted their reliability. However, upon re-running the regression analyses, the results remained largely unchanged, showing only minor discrepancies.

Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale (HSNS)

The HSNS 57 measures vulnerable narcissism using responses ranging 1–5, Very uncharacteristic or untrue, strongly disagree to Very characteristic or true, strongly agree. The index is derived from the sum of items, resulting in a possible range between 10 and 50. The Swedish version (translated by Björkman and Kajonius, revised by Hellström) was used (see Supplementary Information for HSNS in both English and Swedish).

Short dark triad (SD3)

The SD3 62 comprises three scales, but only items from the subclinical Narcissism (the grandiose variant) scale were sampled. The SD3 uses responses ranging 1–5, from Strongly disagree to Strongly agree . The Swedish version (translated and adapted by Lindén and Dåderman) is published 63 .

Individual Work Performance Questionnaire (IWPQ)

The IWPQ 64 comprises three scales: task performance, contextual performance, and counterproductive work behavior (CWB). IWPQ measures individual work performance using responses ranging 1–5, from Seldom to Always for task and contextual performance, and from Never to Often for CWB. All items have a recall period of 3 months. The Swedish version is published 7 .

Mini international personality item pool-6 inventory (Mini-IPIP6)

The Mini-IPIP6 65 measures core personality traits comprising six scales: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and honesty-humility. The Mini-IPIP6 uses responses ranging 1–7, from Strongly disagree to Strongly agree . The Swedish version (translated and adapted by Backström, Dåderman, Grankvist, Kajonius, and Lundin) is published 63 .

Balanced inventory of desirable responding (BIDR 6) 66 , 67

BIDR 6 comprises two measures for socially desirable responding using responses ranging 1–7, from Not true at all to Completely true . These can be separated into unconscious self-deceptive enhancement and conscious impression management 68 , 69 . Self-deceptive enhancement is a stable personality characteristic, while impression management depends on the characteristics of the situation a person is in 69 . The Swedish version (translated by Grankvist and Lundin) was used (see Supplementary Information for BIDR 6 in both English and Swedish).

Data management and statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed in SPSS 28. Single missing values (< 1%) were replaced by the mean for all cases. We computed means and standard deviations of the variables. Internal consistency of the scales was determined using Cronbach’s alpha 70 . Because we used short scales comprising a few items, we also calculated mean inter-item correlations.

To evaluate Hypothesis 1 , aimed at distinguishing between two distinct variants of narcissism among managers and the general population, we conducted one-sample t -tests across several samples. Data on narcissism were sourced from published studies or directly obtained from the authors of the Swedish versions of the SD3 and the HSNS. The weighted mean differences were calculated for the SD3 and HSNS narcissism average scores obtained by the authors of the citied studies (see Table 1 for details), and compared to our sample’s average score using one sample t -tests. In line with Erkoreka and Navarro 71 , it was imperative to recalculate the data collected from Hendin and Check’s 57 samples.

To evaluate Hypothesis 2 , how the variants of narcissism relate to core personality traits, we employed Pearson correlation coefficients (see Table 2 ).

To evaluate Hypothesis 3 , how these predict managerial work-related performance, we performed three hierarchical regression analyses. Both variants of narcissism were entered as predictors in the first step. Subsequently, all six core personality traits were included in the second step, followed by the two scales measuring socially desirable responding in the final step.

We adhered to effect size guidelines in individual differences research, such as considering r = 0.20–0.30 as indicative of a medium effect 72 . Cohen’s d values are typically interpreted as follows: 0.20 represents a small effect (might not be discernible to the naked eye), 0.50 signifies a medium effect, and 0.80 indicates a large effect (are easily visible without aid) 73 .

Ethical statement

This study adhered to the Swedish Research Council’s guidelines. Data were collected in 2017 in accordance with Swedish law (2003:460, §2). Approval was secured from participating organization leaders, and the project’s data handling was officially sanctioned by Municipal Academy West (Diary no. 100127). All experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee at Lund University. Prior to accessing the questionnaire, participants were informed about purpose of this study, and that their participation was voluntary and confidential, with guaranteed anonymity and the option to withdraw at any time. The questionnaire did not inquire about sensitive personal data. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants following the Declaration of Helsinki.

How does narcissism vary between managers and people from the general population?

Table 1 demonstrates a notable distinction between the present group of managers and samples from the general population. Particularly, these managers showcased significantly higher mean scores in measuring grandiose narcissism and notably lower scores in vulnerable narcissism. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 finds support. The observed variance ranged from small to considerable for grandiose narcissism and notably substantial for vulnerable narcissism.

Table 2 illustrates the correlations between core personality traits, socially desirable responding, and the two observed variants of narcissism within our manager sample. In line with Hypothesis 2a, grandiose narcissism showed a strong positive correlation with extraversion. However, contrary to Hypothesis 2a, grandiose narcissism did not display the expected negative correlations with neuroticism and agreeableness. Similarly, in line with Hypothesis 2b, vulnerable narcissism showed strong positive correlations with neuroticism and negative correlations with extraversion and agreeableness. Both narcissism variants demonstrated clear negative correlations with honesty-humility, aligning with Hypotheses 2a and 2b. Contrary to Hypothesis 2c, which posited that conscientiousness would not significantly correlate with either variant of narcissism, it is notable that grandiose narcissism unexpectedly displayed a negative significant correlation with conscientiousness. However, in line with Hypothesis 2c, vulnerable narcissism did not exhibit a significant correlation with conscientiousness. Consistent with Hypotheses 3a and 3b, the correlations between the two narcissism variants and the three dimensions of individual work performance revealed contrasting trends, prompting further investigation through regression analyses in subsequent steps.

We incorporated measures to account for socially desirable responses. Notably, impression management, reflecting conscious misrepresentation, strongly correlated negatively with vulnerable narcissism, CWB, and neuroticism, while positively correlating with honesty-humility. Meanwhile, self-deceptive enhancement, a subconscious positivity bias in responses, displayed a strong positive correlation solely with conscientiousness.

Predictions of managerial work performance

In order to test hypothesis 3, we performed regression analyses on work performance (IWPQ), using the dimensions of task performance, contextual performance, and CWB as dependent variables. To isolate the distinct impact of narcissism while accounting for core personality traits and socially desirable responding, we conducted three separate hierarchical linear regressions, one for each dependent variable. The detailed outcomes of these analyses can be found in Table 3 .

In summary, after controlling for the role of core personality traits and socially desirable responding, grandiose narcissism didn’t predict work performance variables, while vulnerable narcissism and neuroticism predicted higher CWB and lower task performance. Conscientiousness stood out as the most influential predictor of task performance, while extraversion as the most influential predictor of contextual performance. These findings were adjusted for self-deceptive enhancement, a variable found to have no significant influence on any dimension of individual work performance. Impression management, however, negatively influenced CWB.

This study aimed to bridge existing gaps in managerial literature by shedding light on the comparison of mean values of narcissistic variants among managers with people from the general population. It examined their divergent correlations with core personality traits, while also considering socially desirable responding. Furthermore, it explored their associations with various forms of managerial performance, encompassing task performance, contextual performance and counterproductive work behavior.

Only a few studies 37 , 38 , 39 have investigated narcissism’s relationships with the three dimensions of individual work performance 36 . However, these studies encompassed broader participant groups beyond managerial roles and didn’t specifically target vulnerable narcissism. Among these, Ramos-Villagrasa et al. 39 revealed a noteworthy correlation ( r = 0.23) between task performance and grandiose narcissism. Interestingly, existing findings consistently showed a moderate correlation (approximately r ~ 0.20) between grandiose narcissism and contextual performance, including our study. However, after controlling for core personality traits and social desirability responding, this significant association disappeared (Table 3 ), which other studies have not analyzed. Notably, our study unveiled consciousness as the most influential predictor of contextual performance, a novel but not surprising discovery. Aligning with prior research, our study corroborated the minimal impact of grandiose narcissism on CWB.

Our study expanded upon prior research, particularly Miller et al. 50 , by examining a sample comprised exclusively of managers, revealing an absence of significant correlation between grandiose leadership and vulnerable narcissism (Table 2 ). The table highlights a novel finding within the managerial sample: contrary to Hypothesis 2a, grandiose narcissism did not exhibit the anticipated negative correlations with neuroticism and agreeableness. Additionally, it is noteworthy that grandiose narcissism unexpectedly demonstrated a negative significant correlation with conscientiousness. These results diverge from those observed in the general population 50 , 56 . We will endeavor to elucidate these inconsistencies. These findings may be illuminated by the distinct differences in narcissistic tendencies observed between our manager-only sample and samples drawn from the general population. Specifically, managers exhibited higher levels of grandiose narcissism and lower levels of vulnerable narcissism (see Table 1 ). Another potential explanation for the lack of a negative correlation between grandiose narcissism in managers and agreeableness could be attributed to a prevalent cultural norm in Swedish workplaces known as “jäntelagen,” which emphasizes a tendency to agree and maintain politeness with coworkers. Agreeableness reflects a disposition towards trust, compassion, and kindness. Managers high in agreeableness tend to foster positive interpersonal connections, prioritize cooperation, and seek to prevent conflicts. The majority of the participants are women, and it is well-documented that women typically exhibit higher levels of agreeableness compared to men 44 . Likewise, the absence of a negative correlation between high grandiose narcissism and neuroticism may be attributed to a cultural norm prevalent in Swedish workplaces, characterized by strong employment regulations that ensure job security.

A final notable contribution of our study was the exploration of vulnerable narcissism’s impact on the three dimensions of individual work performance (see Table 3 ). Through regression analyses, while adjusting for core personality traits and socially desirable responding, our results indicated that only vulnerable narcissism and neuroticism emerged as significant predictors of CWB. Vulnerable narcissism also negatively predicted task performance, although the strength of this association was limited. Furthermore, our study unveiled that grandiose narcissism related positively to self-deceptive enhancement, while vulnerable narcissism related negatively with impression management—a novel finding likely unreported in prior literature.