Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Visual Rhetoric: Overview

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This section of the OWL discusses the use of rhetorical theory and rhetoric as it relates to visuals and design. "Visual rhetoric" has been used to mean anything from the use of images as argument, to the arrangement of elements on a page for rhetorical effect, to the use of typography (fonts), and more.

While we cannot hope to cover these and many other topics in depth in this resource, it will be possible for us to look at some of the common visual rhetoric problems encountered by student writers: the text elements of a page (including font choices), the use of visuals (including photographs, illustrations, and charts and graphs), and the role of overall design in composing a page rhetorically.

Note: Much of the current use of "visual rhetoric" is directed at analyzing images and other visuals that already exist. This handout is meant to help you generate visual material.

What is visual rhetoric?

The term visual rhetoric falls under an umbrella term known as visual literacy, which is generally split into three categories: visual thinking, visual learning, visual rhetoric/communication (though clearly visual thinking and visual learning must occur in order to communicate visually). The following diagram illustrates these ideas. The graphic is modified from Sandra Moriarty's diagram in her essay, "A Conceptual Map of Visual Communication" and from "Teaching Visual Literacy and Document Design in First-Year Composition" (MA Thesis) by Allen Brizee.

Visual Literacy

Essentially, a beginning definition of visual rhetoric and its applications are as follows:

- Use of images as argument

- Arrangement of elements on a page

- Use of typography (fonts, etc.)

- Analysis of existing images and visuals

Other OWL resources that are related to visual rhetoric and that may help you understand these ideas are the following:

- Visual Rhetoric Slide Presentation

- Color Theory Slide Presentation

- Using Fonts with Purpose

- Design an Effective PowerPoint Presentation

- HATS (Headings, Access, Typography, and Space) Slide Presentation: A Design Procedure for Routine Business Documents

For more information:

You may also download the pdf Works Cited and Works Referenced from "Teaching Visual Literacy and Document Design in First-Year Composition" in the Media box above. This pdf contains a number of resources on visual literacy, visual rhetoric, and document design and the uses of these concepts in composition and professional writing.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

15 Analyzing Visual Rhetoric

This chapter will describe visual rhetoric and its related fields of study so that you will be able to recognize how visual media is employed to achieve a rhetorical effect.

Below is a graphic display of a home. Some things work well (cabinetry and counters i the kitchen and a fireplace in an adjoining living area) while others don’t quite achieve the desired effect. For example, what does a fireworks sign have to do with cooking? Why is there a bust inside the fireplace? What could the designers or homeowners have used instead?

VISUAL RHETORIC DEFINED

Visual rhetoric is a special area of academic study unto its own. It has a long history in the study of art and semiotics (the study of symbols) and it has kinship to the classical study of oral rhetoric such as persuasive speeches and legal arguments.

For the purpose of our studies, we will define the phrase “visual rhetoric” as the means by which visual imagery can be used to achieve a communication goal such as to influence people’s attitudes, opinions, and beliefs. The study of visual rhetoric, therefore, is to ask the question, “How do images act rhetorically upon viewers?” (Hill, C. A., & Helmers, M., 2012, p. 1).

The techniques of visual rhetoric align with the classic pillars of rhetoric :

- Ethos – An ethical appeal meant to convince an audience of the author’s credibility or character.

- Pathos – An emotional appeal meant to persuade an audience by appealing to their emotions.

- Logos – An appeal to logic meant to convince an audience by use of logic or reason.

One of today’s most familiar uses of visual rhetoric are the memes you see in social media. Memes, in an incredibly concise and penetrating way, are able to punctuate a dialogue or issue with “likes” and shares calculating a somewhat blunt measure of their popularity.

An example of a popular meme as documented by the KnowYourMeme.com website.

From KnowYourMeme.com: “Success Kid, sometimes known as I Hate Sandcastles, is a reaction image of a baby at a beach with a smug facial expression. It has been used in image macros to designate either success or frustration. In early 2011, the original image was turned into an advice animal style image macro with captions describing a situation that goes better than expected.” © KnowYourMeme.com All Rights Reserved

So if memes are a common part of your daily communication, it is a good entry point for describing the capability of visual rhetoric.

Read Purdue OWL: Visual Rhetoric Overview

This brief resource will show a graphical representation of visual rhetoric in relation to other disciplines plus some references to other research.

Read The American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA) – Visual Rhetoric: An Introduction for Students of Visual Communication

This article provides an overview of visual rhetoric as a body of knowledge within visual literacy and graphic design.

FOUNDATIONS OF RHETORIC

In this section, we will describe the areas of foundation knowledge that surround the principles of visual rhetoric.

RHETORIC: THE TECHNIQUES OF PERSUASION

Before describing the principles of visual rhetoric, it is important to fully understand the traditions of rhetoric in speaking and writing. The video below describes the foundation elements of rhetoric – logos, pathos, and ethos (logic, emotion, and credibility).

SEMIOTICS: THE STUDY OF SIGNS AND SYMBOLS

Visual imagery is analogue , meaning that it is analogous to, or bears a similarity to, that which it represents. Authors use the power of analogy to create a symbolic message.

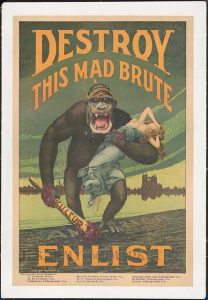

In the example below (figure 1), we see a poster used during Word War I portraying a fierce gorilla symbolizing a terrifying German enemy while the draped bare chested woman symbolizes the spirit of American liberty. The poster is intended to convey the idea that, unless you enlist in the U.S. Army, the German Kaiser’s rabid soldiers would eventually land on American soil.

A reasonable person would know that there really wasn’t any risk of an actual gorilla landing on the shores of United States who would, in one hand, scoop up a helpless woman to carry around while he whacked things with his club. Still, the rhetorical effect contributed to a larger communication strategy at the time to foster an effort to increase recruitment. This was achieved through the use of overt symbolic references to real objects combined with dramatic composition techniques (the gorilla’s feet standing on top of the word “America”, bold typefaces, blood colors, stormy green skies, and urgent text).

The study of symbols, metaphors, expressions, and signs to represent ideas, emotions, action, and information is the discipline called semiotics . Semiotics extends to other realms of communication such as color coding, art, graffiti, universal codes for public spaces, and even to the wordless assembly instructions of a piece of IKEA furniture (see figure 2).

Techniques of visual rhetoric include using symbolic references to elicit a reaction from your audience. So as you select some kind of imagery as part of your visual communication, you would be employing the psychological language of symbolism to achieve your effect.

Key Takeaway #1

Using images as symbols for ideas, expressions, ideologies, and other entities is an effective way to promote your message.

LINGUISTICS: THE STUDY OF LANGUAGE AND DISCOURSE

Language: Linguists study language in both its written and spoken form including its historical, cultural, anthropological, and political backgrounds. As described in the Introduction chapter, written language is produced in the form of a code (the alphabet). Words, as a code for a specific meaning in the dictionary, are often insufficient in conveying the intended meaning of a message unequivocally. If you have ever experienced the awkwardness of an email message or social media post that was misinterpreted by others in the worst possible way, you are familiar with this phenomenon.

The cause of this problem is rooted in the complexity of conveying a message in a medium that is too lean to punctuate how the message is to be interpreted. An example would be the difference between sending a letter to one’s beloved versus saying the same words in person. The beloved’s interpretation of the same message in the form of a letter could be different than if it were conveyed face-to-face even if the same words were used. The absence of non-verbal cues in the letter could cause a certain sarcastic or humorous passage to be errantly perceived as an insult.

Famed linguist Gregory Bateson (1968) described how a message is segmented into “content” and “relationship”. While the content could be described as the literal meaning of words as decoded by the lexicon of our language, the relationship portion of a message is the part that cues the receiver about how that message is to be taken as .

It is the author’s challenge to account for the audience’s need for both meaning and interpretation.

Discourse: We use language as the basis of human discourse, which is defined as “the production of knowledge through language” (Hall, 1997, p. 44). Hall’s inclusion of the word “production” supposes that knowledge is a process of human construction : As we communicate, we are constructing a shared sense of truth and reality while forming the contours of a social world. Our social world “… is the overall outcome of our joint processes of social – specifically, communicative – construction” (Couldry, N., 2018, p. 18).

As you construct messages through the use of oral, written, and visual media, you are, in essence, creating a shared understanding – a reality – through a social process communication.

Key Takeaway #2

You will be challenged to compose messages so that they are interpreted by your audience as you intended to create a shared sense of reality.

VISUAL RHETORIC IN PRACTICE

The traditional study of rhetoric, as the video in this chapter describes, is the study of communication in the art of persuasion. The term visual rhetoric suggests that there is kinship with traditional oral rhetoric and written rhetoric, but in a different (visual) form.

For example, in the print ad below for Pinnacle Bank, the visual element has nothing to do with banking, but has everything to do with persuading the viewer that the bank has ethos , or credibility, with respect to the individuals or businesses they are appealing to. To the audience, the selection of a farm image is intended to recognize the audience’s perspective, interests, traditions, and livelihood so that it promotes feelings of trust, connection, and mutual understanding, even though the occupations of banker and farmer couldn’t be more different.

In the example below, we see an effort to appeal to both emotion (pathos) and logic (logos) in the famous “Morning in America” TV ad from the 1984 presidential election. The emotional elements are triggered through the use of the wedding scene and the flag raising scene. The logical element, expressed in the narrator’s voiceover, is presented in the form of economic statistics and reinforced by a question that asks why we would want to return to the conditions that preceded president Reagan’s first term in office.

VISUAL RHETORIC VERSUS VISUAL DECORATION

Not all visual information in media is intended for a rhetorical purpose. In deconstructing visual media, you will be challenged to distinguish between visual imagery that is purposeful and imagery that has no particular purpose other than decoration. In the example below, the small parrot image, by itself, does not elevate the information on the chart to a higher level of meaning. Removing the image of the parrot would not take away from the meaning of the other information.

This is an example of an infographic where the image of the parrot in the bottom right corner does not promote a rhetorical effect. It is purely decorative. However, other images within this infographic DO have rhetorical effects, the parrot aside.

Globe-Trotting inforgraphic courtesy of: Commons:WikiProject Aviation/recent uploads/2016 October 1

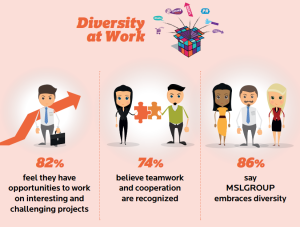

In the example below, we see another infographic, this time where different images are used for a rhetorical effect (cube, puzzle pieces, arrow pointing up). In this case, the intended message is extended beyond the literal meaning of the words below the images of the people. The audience gets the sense that the entities served by this corporation are not just those listed, but that they embrace a spirit of diversity and inclusion. The effect of this strategy should be that prospective clients of all backgrounds are welcome to do business with this organization.

Engage! MSLGROUP Employee Survey Infographic is licensed by CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED

Visual rhetoric draws upon the rhetorical traditions found in oral and written rhetoric and operates to achieve the same effect on human perception. Humans communicate using a combination of codes, symbols, analogies, and discourse to form a shared reality.

The author of visual media will need to account for the audience’s need for both information and how that information is intended to be taken as within a larger communicative context.

Bateson, G. (1968). Information and codification: A philosophical approach. In J. Ruesch, & G. Bateson (Eds.), Communication: The social matrix of psychiatry (pp. 168–211). New York, NY: Norton.

Couldry, N., & Hepp, A. (2018). The mediated construction of reality . John Wiley & Sons.

Hall, S. (1997). The work of representation. In S. Hall (Ed.), Representation: cultural representations and signifying practices (pp. 15-64). London: SAGE Publications in association with The Open University.

Hill, C. A., & Helmers, M. (Eds.). (2012). Defining visual rhetorics . Routledge.

Write What Matters Copyright © 2020 by Jonathan Lashley; Liza Long; Amy Minervini; and Joel Gladd is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

34 Understanding Visual Rhetoric

Visuals can dramatically impact our understanding of a rhetorical situation. In a writing class, students do not always think that they will need to be attentive to visuals, but visual information can be a critical component to understanding and analyzing the rhetorical impacts of a multimodal text. This chapter gives examples of what visual rhetoric looks like in everyday situations, unpacking how seemingly mundane images like a food picture on social media or a menu at a restaurant, can have a persuasive impact on the viewer. The chapter then offers students some terms to use when describing visuals in a variety of situations.

Introduction

It’s Friday night and you’re hungry. So, you corral some friends and you all decide that you’d like to go out to eat somewhere new. You hop online to explore your options, and, in the process, you find a wealth of information from menus and visitor reviews to hours and locations. But there’s one factor that has an especially strong influence on your choice: the pictures of the food.

You check out a review page for a hamburger joint and find yourself drooling over a close-up shot of a juicy burger with a slice of cheese oozing over the edge (see figure 1). You click to the next shot and see a cascade of golden french fries on a tray with an ombre-tinted iced tea and lemonade (see figure 2). You click one more time and find yet another delectable shot: a frosty milkshake with a mountain of whipped cream on top. You’re feeling increasingly convinced that this restaurant is where you’ll suggest that you and your friends go out to eat.

You decide to click through to see one more picture, expecting to see yet another culinary delight (see figure 3). But this next photo surprises you: it’s a picture of someone’s tray of food, but it’s dimly lit and a little hard to tell what’s there. The hamburger looks squished and flat, the meat greasy and paltry. The french fries curled up next to the burger look a bit dried out. There’s a mysterious puddle of sauce in a bowl next to the plate burger, and it’s not totally clear what’s in it. The meal suddenly doesn’t look so appetizing after all.

You find yourself confused. All of these pictures are supposedly of food at the same restaurant, but the pictures look so different from each other. Knowing that the images may not accurately reflect the reality of the restaurant experience, you feel angry and misled: how can you possibly know which photos capture the “real” experience at the restaurant? Why trust any photos of restaurant food at all?

The fact of the matter is that you can’t know exactly what your restauranting experience will be like when you walk in the door of a new place. But the images clearly had a persuasive impact on you as a decision-maker: the contrast between the appetizing images and the unappetizing photos made you question the quality and consistency of the restaurant’s food, a contrast that made you wonder whether the restaurant would be the kind of place where you’d like to visit.

The point here is those photos of the food you found at the restaurant impacted your decision-making, which makes them a perfect example of visual rhetoric in action. Visual rhetoric refers to any communicative moment where visuals (photographs, illustrations, cartoons, maps, diagrams, etc.) contribute to making meaning and displaying information. You’re in a writing class right now (which is probably why you’re reading this essay and wondering what hamburgers have to do with anything), and you may think of writing mostly as words on the page. However, as more writers publish and distribute their work online, the more readers expect to find that information may be communicated in multiple modes, from text to visuals and audio. As writing and rhetoric scholar Carolyn Handa puts it,

rhetoric’s association with the written word is arbitrary, a by-product of print culture rather than the epistemological limits of rhetoric itself. We use rhetoric to help us think more clearly, write more elegantly, design more logically. Rhetoric works both to scaffold our ideas for clearer understanding and to structure our critical examinations of both visual and verbal objects. (2)

What Handa means by “the epistemological limits of rhetoric itself” (and yes, that is a mouthful!) is that, when we think of making meaning, building arguments, and reaching our target audiences, we are not limited to words as a tool. In fact, if we limit ourselves to words in our arguments, we may not successfully reach our audiences at all. Some audiences need visuals to think through an idea, and using graphs and diagrams can express some ideas more clearly than text can. So, we have to take visuals into account as part of understanding communication.

You may be thinking that this all sounds good, but what about images that are just pretty for the sake of being pretty? Well, those exist too, but we call those “art.” A picture of a hamburger framed in an art museum does not exist to market hamburgers (though it might make you hungry!). However, a picture of a hamburger on an Instagram feed for a particular restaurant exists as a way to encourage visitors to come and dine at the restaurant. As composition scholar and teacher Kristen Welch describes it: “visual rhetoric is a focus on the practical, relevant, and functional as opposed to an aesthetic analysis or use of visual elements for beauty” (256). It is important to recognize when a visual exists to help us appreciate beauty (and we may even appreciate the beauty of a picture of a hamburger on an Instagram feed), but the context in which we see visuals matters an awful lot in terms of how we analyze and understand their impacts on us as viewers.

Our example of finding food photos from a restaurant online exemplifies just how accessible visual rhetoric really is in our everyday lives. Clearly, the lighting, composition, and angle of the image clearly makes a big difference in our reaction to the image and potentially our willingness to take action and respond to the image (either by going to the restaurant or not). After reading through the opening story, you may have thought of lots of other ways that you encounter other pictures of food online. On social media, for example, a lot of users post images of food they’ve cooked or eaten as a way to share eating experiences. Because of how consumer interests are driven by the platforms they use to access information, visuals are more important than ever for people to make decisions or become attracted to visiting particular spaces. But visual rhetoric is not just about persuading someone to like something or not. Visual rhetoric can also be used to help people understand a concept, break down an idea, or access important pieces of information.

We’ll explore a few more examples of what visual rhetoric can look like in a few other situations where the visuals may not just be persuasive, but they may offer necessary guidance or instruction for the viewer. After that, this chapter will offer you some advice on how you might analyze visuals in your future writing classes so that you, too, can interpret the visuals you encounter in rhetorical situations.

Why Do Visuals Matter?

Let’s think back to the restaurant example one more time. You’ve picked a restaurant for your Friday night dinner and now you’re with your friends and are seated at the dining table. A waiter hands you a menu and guess what? You’re seeing yet another example of visual rhetoric in action. This particular menu comes from a real restaurant, called Oren’s Hummus, which has locations around the San Francisco Bay Area in California (see figure 4).

This restaurant menu doesn’t have pictures on it, but it makes visual choices that may impact which food items you decide to order. For example, separating certain food items under headers, like “Hummus Bowls” and “Grilled Entrees” gives you some quick visual information about what items you can expect to find in those sections. Even more noticeably, the section titled “Dips & Sides” is separated from the other menu items by a green box. While the words “Dips & Sides” may have helped us understand that the items in that section would be smaller-sized than the menu items outside the green box, the use of the green box is a rhetorical tool; it makes it really obvious to the restaurant goer that if they order an item from the Dips & Sides section, it’s going to be smaller than the items that are not inside the green box.

Think about this particular restaurant’s context even more: the restaurant advertises its “hummus,” a Mediterranean dip made out of garbanzo beans, in its name, but for many visitors, they may not have experienced eating hummus in the way that this restaurant serves it. For many diners, they may have experienced hummus as a dip or side rather than as a main course. However, because “Hummus Bowls” appear on the menu separately from the Dips & Sides, it’s clear that the hummus bowls can actually be eaten as a main dish rather than as a side dish. This is a new situation, a subversion of expectations, for many restaurant-goers, so the menu has to do some visual work to help the visitor understand what to expect from the food they order.

Do you see how many words it took me to explain how the Dips & Sides section differs from the other menu sections? If you were a hungry diner, would you want to take the time to listen to all of that or read that long explanation? Probably not. That’s why the document design on the menu is so important: it aligns our expectations quickly, simply, and clearly. Document design is yet another example of visual rhetoric in action, as it persuades us to make particular choices (in this case, about what we order). To learn more about components of document design in particular, you may want to look to another essay in the Writing Spaces series, called “Beyond Black on White: Document Design and Formatting in the Writing Classroom” by Michael J. Klein and Kristi L. Shackleford. They make the important case that, “Good document design integrates the words on the page with appropriate imagery to fully illustrate your meaning,” a sentiment that reflects exactly what we saw happen with the menu (333).

The menu also includes some symbols to indicate which menu items may adhere to particular dietary needs, a piece of visual information that may be critical to those with allergies or sensitivities. Next to the descriptions of particular menu items, the letters “gf” and “v” indicate which items on the menu are “gluten free” (items that don’t contain binding proteins found in wheat and other grains) or “vegan” (items that don’t contain animal products, like meat or dairy); a key for these restrictions is in the bottom right-hand corner of the menu for visitors to reference if they are seeking out those indications.

Some menus will indicate these dietary restrictions using visual symbols instead; for example, other menus may include a green leaf icon next to particular items to indicate that the menu item is vegetarian or a brown-colored “G” inside a circle often indicates that the menu item is gluten-free. While you, as a reader, may have some critiques of how clearly the Oren’s Hummus menu makes these dietary restrictions clear, the point is that the visual indicators are there to guide visitors in critical ways.

You may also notice that, on the menu, the two biggest visual items are the restaurant’s logo and slogan (“Rip, Scoop, Eat!”) and the inclusion of “Gluten Free Pita” on its menu. These largest items show the restaurant’s priorities: by making its slogan and name large, the menu reminds you of its branding, while also offering you an instruction for enjoying its signature dishes: to rip a piece of pita, scoop the pita into dip, and eat it! Making the words “Gluten Free Pita” among the largest on the menu also suggests that the restaurant aims to reach a diversity of diners, even those who may be sensitive to or avoiding eating wheat-based products. The restaurant’s priorities are clear: to educate unfamiliar hummus-eaters with the process and experience of eating hummus while also convincing diners that, regardless of their dietary restrictions, there will likely be something at the restaurant that the diner will enjoy.

The point of all this analysis of the Oren’s Hummus menu is that choices in document text, color, image, and spacing matter in order to help you make choices, big and small. As you can see, visuals play a tremendous role in a) how we make decisions, b) how we receive instructions, and c) how we understand information. But let’s get a little bit more fine-grained: what elements of visual design exactly can help make certain ideas clearer than others? How do we name and define the persuasive elements of a visual? Let’s look to some elements of visual design to answer those questions.

Elements of Visual Design: Line, Color, Shape, Size, Space, Value, Texture

The elements of visual design are one way to help us understand more clearly why a visual has a particular kind of effect on its viewer. The elements of visual design may not necessarily help us understand purpose or intent, but they can help us break down different component parts of images so that we can start to puzzle out what an image might do for us as viewers and readers. We, naturally, should understand these elements in their particular contexts, and the impacts of these elements will likely differ depending on where and how we’re viewing a particular image. With that said, beginning to name what we notice is one important step to gathering more information about images so that we can articulate their meaning more clearly.

Here are six elements of visual design you may want to consider in order to understand how an image is communicating a particular idea.

Lines are visual markers that are often used to divide different sections of an image or document into multiple parts. Lines can create order in something disorderly, offering the eyes a sense of where to go or how to differentiate between different elements. Many artists and graphic designers often rely on grids of lines to help them determine where to place particular elements in a picture or a graphic to ensure that the viewer can understand where to focus their attention or where to differentiate one piece of information from another (see figure 5).

When you look at a visual, consider asking questions about line in the following ways:

- What role is the line playing in helping me understand what to emphasize? What to deemphasize?

- What role is the line playing in connecting one part of the image with the other? What relationships between the parts of the image are at play?

- What kind of pattern do I see in this image or diagram? How does the pattern help shape my understanding of the image, graph, or shape?

Color can help evoke emotions in the viewer while also helping the viewer distinguish what’s important or what should be emphasized. In fact, many designers use resources like color wheels to help them determine what kinds of color combinations complement each other and what kinds of color combinations offer contrast (see figure 6). It is generally agreed upon that particular colors evoke different emotions than others; for example, colors like orange and red tend to convey warmth or passion while colors like blue and purple tend to convey coolness or calm.

However, some colors have deep cultural associations. For example, in China, the color red tends to signify good luck, joy, and happiness; that’s why gifts given at Chinese New Year’s tend to be in red envelopes and also why wedding dresses in China are often red-colored. In Western cultures, on the other hand, red can more often signify danger or caution. In the United States, we may think of red as the color for a stop sign, for example.

Lots of resources online exist to help designers keep particular cultural associations with color in mind, especially in sensitive situations! For example, while wearing black to a funeral in the United States would be conventional and respectful, it would actually be considered quite odd to wear black to a funeral in Cambodia, where the color white is much more often worn for events of mourning.

You may not be able to account for all of the different situations where colors may signify different things to different viewers, but as a reader and composer, you will want to be attentive to how and where color is used, even if the possibilities for interpretation may vary.

When you look at a visual, consider asking questions about color in the following ways:

- What is color (or the lack of color if the visual is black-and-white) emphasizing here? What is de-emphasized?

- Given my understanding of color, what emotions does the color evoke for me? What do the colors in the image remind me of?

- How might this visual change if the color scheme was inverted? How would the impact on the viewer be altered?

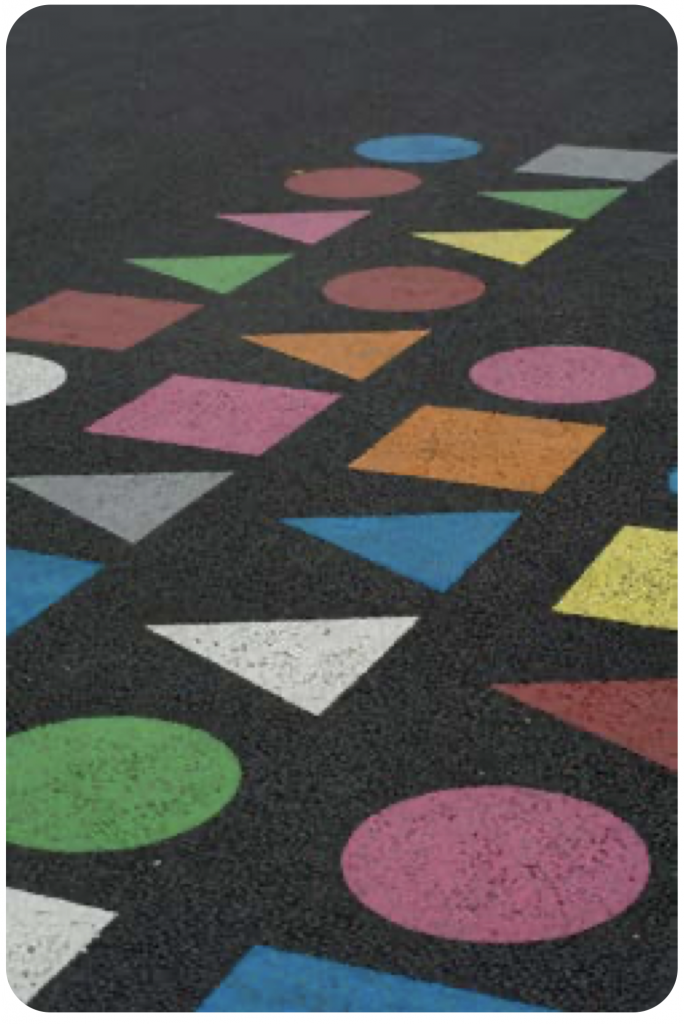

All visuals contain elements that take on different shapes (see figure 7). We probably learned about shapes at some point when we were children, especially if we played with toy blocks. Have you ever seen toy blocks in the shapes of squares, triangles, and circles? If so, congratulations, you’ve had exposure to the three basic shape types that exist in the world!

Many other shapes build off of these three fundamental shape types. For example, in the natural world, we may easily recognize shapes like clouds, trees, and water droplets. Similarly, certain man-made objects take on particular meanings through their shapes alone. For example, lightbulbs are shapes that typically symbolize new or “bright” ideas, while the shape of a rocket or airplane often signifies innovation or the accomplishment of a goal.

Shapes that come from the real world—like the clouds and trees or the light bulbs and rocket ships—tend to be culturally situated in the same way that colors can have different cultural associations. Yet as readers of visuals, we can analyze the roles that shapes play based on our own understanding of the audience’s needs and purposes when accessing the visual.

When you look at a visual, consider asking questions about shapes in the following ways:

- What does this shape typically signify? Where have I seen this kind of shape before?

- Given my understanding of this shape, what emotions does the shape evoke for me?

- What might the shape be drawing attention to?

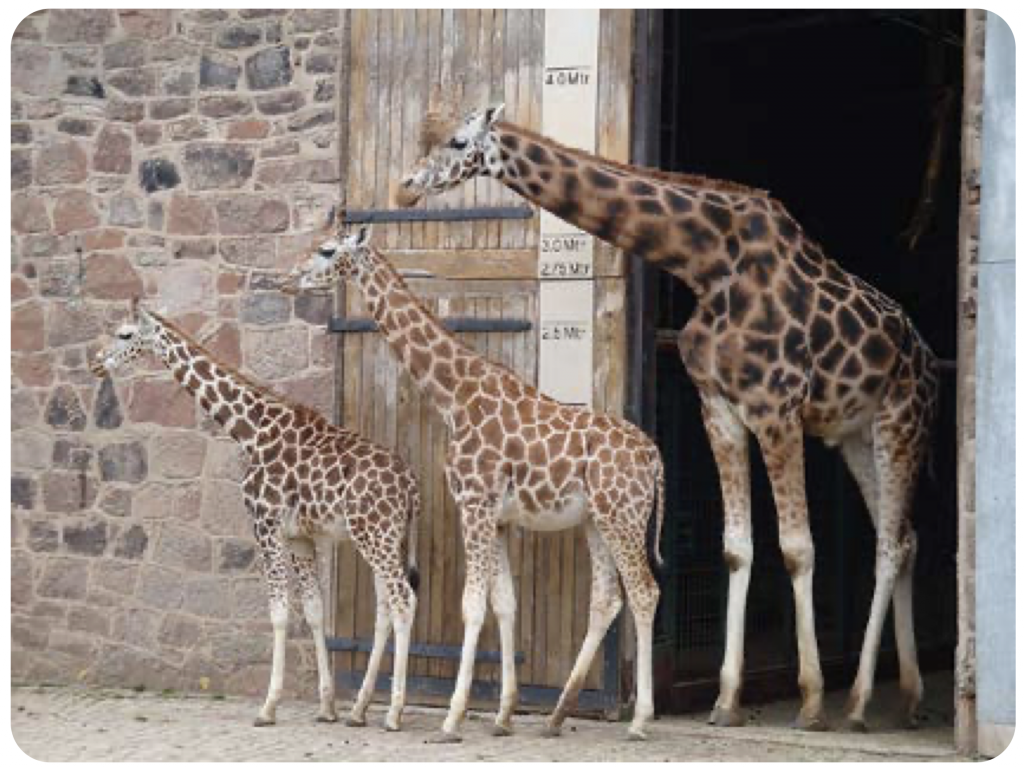

In visuals, different elements may be large while other elements may be small. Typically, the elements that are larger sizes than other elements are of greater importance than the elements that are smaller sizes. But larger things are not always more valuable; the other elements in the visual may visually draw attention to smaller-sized items so that we don’t lose sight of the smaller parts of the visual entirely. Large images next to small images may also be used to help us compare two parts so that we can see how they are related to each other (see figure 8).

When you look at a visual, consider asking questions about size in the following ways:

- Which elements in the visual are larger than the other elements?

- How do the sizes of different elements in the visual impact your understanding of what’s in the visual?

- What is your reaction to seeing the different sizes in the visual? Do any of the sizes of the elements surprise you? Why or why not?

In between or around the elements in a particular visual, there is always some empty space. Some designers call this “white space” or “neutral space.” Space is critical to help distinguish between the different elements in a visual. Without space, particular elements in the visual may be hard to distinguish or may have the effect that the visual is “busy” and, therefore, hard to read and understand.

Even in a document that is mostly text, space signifies meaning. For example, when you split paragraphs into their individual units, the space before and after the paragraph indicates that one thought is about to begin while another thought ends. Similarly, in other kinds of visuals, space might help a certain element stand out from other parts or it might help you understand where one part of the image begins and another part ends (see figure 9).

When you look at a visual, consider asking questions about space in the following ways:

- How much “white space” or “neutral space” is there in the visual? Is this space evenly distributed or are the spaces uneven?

- What effect does the space in this visual have? How does the space break up or distinguish different elements of the visual?

- What is your reaction to seeing the space in the visual?

Value refers to the lightness or darkness of a particular element in a visual. For example, think of a visual that may use different shades of the color blue; the elements that are darker blue than the lighter blue elements convey that the darker blue elements have greater value than the lighter blue elements. Just as something that is larger in size may signify greater importance than something that is smaller in size, something that is darker in color tends to signify greater value than something that is lighter in color.

Value is a comparative function by default; a dark color by itself may not mean anything unless a lighter color is present by comparison. Similarly, a “dark” visual may not necessarily have greater value than a “light” visual; however, if there are both dark and light elements in a particular visual, those shades signify differing levels of importance or attention in the visual itself. Sometimes, the dark elements may be meant to obscure information and make the lighter elements more visible. At other times, darker shades of a particular color may draw more attention to them than lighter shades of a color (see figure 10).

When you look at a visual, consider asking questions about value in the following ways:

- How do different values create importance? Depth? What is emphasized?

- What effect does value in this visual have? How does value break up or distinguish different elements of the visual?

- What is your reaction to seeing different values of visual depth in this visual?

We may think of texture primarily from a tactile perspective initially. When we touch different objects, we tend to notice texture right away: silk tend to be smooth to the touch while burlap tends to be rough and bumpy. But we can look at a picture and detect different surfaces just by the look of it too, and the conveyance of those textures may also impact our orientation and understanding of what the image conveys. For example, a visual that includes lots of tiny dots may convey a bumpy texture while a visual that includes lots of wavy lines and wavy images may convey a smoother or more “watery” texture. Textures might be used to evoke particular sensations in the viewer, but they may also be used to distinguish one visual element from another (see figure 11).

When you look at a visual, consider asking questions about texture in the following ways:

- What kinds of textures do I see in this visual? Are textures clearly implied or does the visual just include one kind of texture?

- What effect does texture (or the lack of texture) have on understanding what I should focus on in this image? How does texture break up or distinguish different elements of the visual?

- What is your reaction to seeing different textures in this visual?

Concluding Thoughts

Once we start noticing the role that visuals play all around us, we gain a greater awareness of the range of strategies that communicators use to get our attention. This chapter is just a start in helping you to recognize some examples of visual rhetoric and the roles that visuals can play to help make meaning and persuade others. There is a lot more to learn about designing and making your own visuals. But just as reading will help you become a better writer, viewing and training your eye to recognize what’s happening in images will help you to become a better designer.

As you look ahead to thinking capaciously about the strategies you might use to employ images and other media in your writing, bear in mind that not all of your readers will have equal access to all of the communicative strategies you’re employing. For visuals in particular, you may have readers who are visually impaired or blind and may not be able to understand or recognize the role that your images are playing in your text. However, as a writer, there are some strategies you can use to help your reader appreciate your use of visuals even if they are not able to see images in the same way that you can. Captions (as you saw included in this chapter) and alternative text (for Web-based images) are ways that you, as a writer, can describe what’s happening in a picture so that even if a reader cannot see the image, they can get a sense of what the picture might look like and what effect the picture is having on the document itself.

A picture is often worth a thousand words because it implies so much and can give us a lot of information quickly. Seeing may not always be believing, but visual rhetoric can be a pretty powerful way to help people understand an idea differently than they may have otherwise.

Works Cited

Handa, Carolyn. Visual Rhetoric in a Digital World: A Critical Sourcebook . Bedford/St. Martins, 2004.

Klein, Michael J., and Kristi L. Shackelford. “Beyond Black on White: Document Design and Formatting in the Writing Classroom.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing , edited by Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky, vol II, Parlor Press, 201, pp. 333-349. http://writingspaces.org/ klein-schackleford–beyond-black-on-white.

Welch, Kristen, Nicholas Lee, and Dustin Shuman. “Teaching Visual Rhetoric in the First-Year Composition Classroom.” Teaching English in the Two-Year College vol. 37, no. 3 March 2010, pp. 256-264.

Teacher Resources for Understanding Visual Rhetoric by Jenae Cohn

Overview and teaching strategies.

This essay is intended as an overview of what visual rhetoric is and how it functions alongside other rhetorical strategies that students may encounter in their composition courses. This essay could work well in a unit introducing students to definitions of “rhetoric” so that students can continue to complicate their understanding of rhetoric beyond alphabetic text. This chapter may also be useful to introduce a unit on multimodal composition, especially when students are starting to look at examples of model multimodal texts and understanding the role that visuals may play in those texts. Students may have varying degrees of abilities to describe or name the effects that visuals may have on an audience, and this reading is intended to help students articulate the rhetorical work that visuals do while also giving them some vocabulary to name the basic elements of a visual. This chapter focuses primarily on the analysis of visuals rather than on the composition of visuals, so bear in mind that this chapter does not include tool suggestions or any “how-to” tips on creating visuals. This chapter also does not cover best practices on attributing images appropriately (via Creative Commons licensing, for example) though a conversation around visual rhetoric for multimodal composing should orient students to these best practices so that students understand how to use and incorporate images legally and ethically into their work.

In this chapter, I bring in examples that are accessible to a diverse student populace. That said, it may be worth engaging in class conversation about the ways in which certain visuals may have different effects on different audiences, as particular pieces of iconography or certain photographs may be understood differently by audiences with various cultural backgrounds or experiences. When selecting images for students to choose or analyze, bringing in historical or cultural context is useful since that information may shape students’ abilities to understand the rhetorical purpose and situation for particular visuals.

Here I offer several in-class activities that I regularly use in line with the conversations offered in the textbook chapter to supplement what the chapter introduces.

- In the first section of this essay, you experienced the story of choosing a restaurant to dine out at with your friends. In this story, the different kinds of pictures shaped the decision made. When have you made a decision based on pictures or visuals? How did the pictures or visuals affect your decision exactly?

- In the discussion of the menu from Oren’s Hummus, it’s clear that the organization and design of the information may impact how a diner might decide what to eat. If you had the opportunity to re-design the menu at Oren’s, what decisions would you make? Why would you make those decisions?

- There are six elements of visual design named in this chapter. Which of these elements were new to you? Which were ones you had encountered before? Individually or in a small group, take a look at either a picture of a poster from the Works Progress Administration (www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/wpapos/) OR find a photograph from the Associated Press images database (www.apimages.com/) and see if you and your group members can identify the elements of design in one or two of the historical posters or photographs. Use the guiding questions in the “Elements of Visual Design” section of the chapter to help guide your understanding of the images.

The following are four class activities that can help support students in their development of understanding and interpreting visual rhetoric.

Three Keywords.

Pick an image, photograph, or data visualization for the whole class to look at together. You may want to pick something that is related to a topic that the class has been discussing or perhaps something that could act as a source for an upcoming research assignment that the students will conduct. Project or share the visual in a shared space and ask each student to come up with three keywords that they would use to describe the image. Students may submit their three keywords to a polling platform (like PollEverywhere, Google Forms, or a quiz feature in a learning management system) so that all of the results are anonymized and collected in one place. When every student has submitted their three keywords, display or share the results to the class. Use the keywords as conversation points to discuss the different impacts the visuals had on different users. How did the keywords overlap? Where did they differ? How might the keywords that students identified align with how they might analyze and contextualize the impact of the visual? Another discussion point may be to consider how their keywords might have changed if they encountered the visual in a different context or situation.

Extreme Makeover: Document Edition

Ask each student to identify an essay, multimodal project, or class assignment. It can be something that they produced for your class or for a different class. After they’ve picked the project they’ve made, ask them to analyze the design choices for the document. What size fonts did they choose? What kinds of pictures did they include, if any? What were some other choices in terms of the document and visual design that they made? Ask them to name the audience and purpose for the document too so that they recognize and name the full context for creating the document. Then, ask them to consider who else might have had a stake in the document they produced. Is there a different audience that they can imagine being invested in that piece of work? Once the students have each named an alternative or a secondary audience for the document, ask them to take a few minutes to do an extreme “makeover” on the document, considering how they would change the layout, organization, design, and inclusion of visuals to accommodate the new audience’s needs. An alternative for them would be to consider how they would redesign the document for publication in a particular platform or news site aggregate, like Buzzfeed or The Huffington Post. These platforms might also change the way they’re orienting the text as well, but for the purposes of this exercise, you may want to encourage students to think primarily about the visuals. After they’ve done a version of their “extreme makeover,” engage in a conversation about the makeover process. What elements of the design did they decide to change? How did their understanding of audience and purpose impact their visual choices?

Comparing Data Visualizations

Pick a few data visualizations (i.e. infographics) from sites like Information is Beautiful (https://informationisbeautiful.net/) or FlowingData (https:// flowingdata.com/) (both of which have large databases of data visualizations and infographics available). Put students into small groups and ask them to analyze what they notice in the data visualizations. What kind of information is being communicated? What is the purpose of using the infographic? How would the understanding of the information differ if it was displayed in text rather than in visuals? How does seeing the visual alter their understanding of the content? A follow-up activity may be to invite them to visualize an aspect of their own writing projects (or research projects) using one of the techniques in the example data visualizations that they explored.

Caption Contest: Creating Effective Captions and Alt-Text for Image

Asking students to write captions for images can be a really interesting moment for students to interrogate and unpack their assumptions about particular images and what they’re privileging as viewers and authors of multimodal or image-rich projects. A conversation about captions can also be a good opportunity to help students understand accessibility and ways to make images readable for a variety of audiences. To start this class activity, you will want to define two different kinds of image captions that exist for visuals published on the Web: captions and alt text. The caption is the text that displays below an image (much like what you would see in a printed textbook and in this particular textbook chapter for that matter). Alt text, on the other hand, is a short, written description of an image Web authors use to describe an image in a sentence for someone using screen reader software. For a reader using screen reader software, the alt text and the caption are both read to offer clarity on what the visual includes. For this class activity, project an image or photograph in a shared space and ask everyone in the class to write both a caption and alt text for the image. You may find it useful to show a few examples of captions and alt text to help clarify the activity. Alternatively, you could have students start with writing captions (since students may have more exposure to reading captions than alt text) and then move to alt text. After students have written their captions, ask them to share with a partner, comparing how their captions are similar or different. Each pair should then take a few minutes to decide which caption they would use for the photo or image if they were publishing the image themselves, justifying their choice as a pair. The results can then be shared with the class where the instructor can lead a longer class conversation about the impacts of captions and the challenges in writing captions to capture the impacts of visuals on the audience.

This essay is a chapter in Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing , Volume 3, a peer-reviewed open textbook series for the writing classroom: https://writingspaces.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/cohn-understanding-visual-rhetoric-1.pdf

About the author.

name: Jenae Cohn

institution: Writing Spaces

website: https://writingspaces.org

Understanding Visual Rhetoric Copyright © by Jenae Cohn is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- No category

Visual Rhetoric Essay

Related documents.

Add this document to collection(s)

You can add this document to your study collection(s)

Add this document to saved

You can add this document to your saved list

Suggest us how to improve StudyLib

(For complaints, use another form )

Input it if you want to receive answer

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This pdf contains a number of resources on visual literacy, visual rhetoric, and document design and the uses of these concepts in composition and professional writing. These resources will help students and teachers better understand the use of visual elements for rhetorical purposes.

So how do you write a visual rhetorical analysis essay? First, you’ll want to begin by examining the rhetorical strengths and weaknesses of your chosen visual.

This chapter gives examples of what visual rhetoric looks like in ev-eryday situations, unpacking how seemingly mundane images like a food picture on social media or a menu at a restaurant, can have a persuasive impact on the viewer. The chapter then offers students some terms to use when describing visuals in a variety of situations. Introduction.

The techniques of visual rhetoric align with the classic pillars of rhetoric: Ethos – An ethical appeal meant to convince an audience of the author’s credibility or character. Pathos – An emotional appeal meant to persuade an audience by appealing to their emotions.

This chapter gives examples of what visual rhetoric looks like in everyday situations, unpacking how seemingly mundane images like a food picture on social media or a menu at a restaurant, can have a persuasive impact on the viewer.

Step by step guide on writing a visual rhetorical analysis. Resources: Visual Analysis Sample - https://docs.google.com/document/d/1_... #college #university #undergraduate #highschool...

In conclusion, composing a Visual Rhetoric Essay demands a unique skill set that extends beyond traditional essay writing. It requires a fusion of visual literacy, critical thinking, and eloquent expression to decode and articulate the persuasive power of images.

The simplest definition for visual rhetoric is how/why visual images communicate meaning. Note that visual rhetoric is not just about superior design and aesthetics but also about how culture and meaning are reflected, communicated, and altered by images.