Understanding Global Change

Discover why the climate and environment changes, your place in the Earth system, and paths to a resilient future.

Population growth

Population growth is the increase in the number of humans on Earth. For most of human history our population size was relatively stable. But with innovation and industrialization, energy, food , water , and medical care became more available and reliable. Consequently, global human population rapidly increased, and continues to do so, with dramatic impacts on global climate and ecosystems. We will need technological and social innovation to help us support the world’s population as we adapt to and mitigate climate and environmental changes.

World human population growth from 10,000 BC to 2019 AD. Data from: The United Nations

Human population growth impacts the Earth system in a variety of ways, including:

- Increasing the extraction of resources from the environment. These resources include fossil fuels (oil, gas, and coal), minerals, trees , water , and wildlife , especially in the oceans. The process of removing resources, in turn, often releases pollutants and waste that reduce air and water quality , and harm the health of humans and other species.

- Increasing the burning of fossil fuels for energy to generate electricity, and to power transportation (for example, cars and planes) and industrial processes.

- Increase in freshwater use for drinking, agriculture , recreation, and industrial processes. Freshwater is extracted from lakes, rivers, the ground, and man-made reservoirs.

- Increasing ecological impacts on environments. Forests and other habitats are disturbed or destroyed to construct urban areas including the construction of homes, businesses, and roads to accommodate growing populations. Additionally, as populations increase, more land is used for agricultural activities to grow crops and support livestock. This, in turn, can decrease species populations , geographic ranges , biodiversity , and alter interactions among organisms.

- Increasing fishing and hunting , which reduces species populations of the exploited species. Fishing and hunting can also indirectly increase numbers of species that are not fished or hunted if more resources become available for the species that remain in the ecosystem.

- Increasing the transport of invasive species , either intentionally or by accident, as people travel and import and export supplies. Urbanization also creates disturbed environments where invasive species often thrive and outcompete native species. For example, many invasive plant species thrive along strips of land next to roads and highways.

- The transmission of diseases . Humans living in densely populated areas can rapidly spread diseases within and among populations. Additionally, because transportation has become easier and more frequent, diseases can spread quickly to new regions.

Can you think of additional cause and effect relationships between human population growth and other parts of the Earth system?

Visit the burning of fossil fuels , agricultural activities , and urbanization pages to learn more about how processes and phenomena related to the size and distribution of human populations affect global climate and ecosystems.

Investigate

Learn more in these real-world examples, and challenge yourself to construct a model that explains the Earth system relationships.

- The Ecology of Human Populations: Thomas Malthus

- A Pleistocene Puzzle: Extinction in South America

Links to Learn More

- United Nations World Population Maps

- Scientific American: Does Population Growth Impact Climate Change?

Globalization: Definition, Benefits, Effects, Examples – What is Globalization?

- Publié le 21 January 2019

- Mis à jour le 25 March 2024

Globalization – what is it? What is the definition of globalization? Benefits and negative effects? What are the top examples of globalization? What famous quotes have been said about globalization?

What is Globalization? All Definitions of Globalization

A simple globalization definition.

Globalization means the speedup of movements and exchanges (of human beings, goods, and services, capital, technologies or cultural practices) all over the planet. One of the effects of globalization is that it promotes and increases interactions between different regions and populations around the globe.

- Related: Traveling Today And Tomorrow: Cities And Countries With More Travelers

An Official Definition of Globalization by the World Health Organization (WHO)

According to WHO , globalization can be defined as ” the increased interconnectedness and interdependence of peoples and countries. It is generally understood to include two inter-related elements: the opening of international borders to increasingly fast flows of goods, services, finance, people and ideas; and the changes in institutions and policies at national and international levels that facilitate or promote such flows.”

What Is Globalization in the Economy?

According to the Committee for Development Policy (a subsidiary body of the United Nations), from an economic point of view, globalization can be defined as: “(…) the increasing interdependence of world economies as a result of the growing scale of cross-border trade of commodities and services, the flow of international capital and the wide and rapid spread of technologies. It reflects the continuing expansion and mutual integration of market frontiers (…) and the rapid growing significance of information in all types of productive activities and marketization are the two major driving forces for economic globalization.”

- Related: Planet VS Economy: How Coronavirus Is Unraveling A Dysfunctional System

What Is Globalization in Geography?

In geography, globalization is defined as the set of processes (economic, social, cultural, technological, institutional) that contribute to the relationship between societies and individuals around the world. It is a progressive process by which exchanges and flows between different parts of the world are intensified.

Globalization and the G20: What is the G20?

The G20 is a global bloc composed by the governments and central bank governors from 19 countries and the European Union (EU). Established in 1999, the G20 gathers the most important industrialized and developing economies to discuss international economic and financial stability. Together, the nations of the G20 account for around 80% of global economic output, nearly 75 percent of all global trade, and about two-thirds of the world’s population.

G20 leaders get together in an annual summit to discuss and coordinate pressing global issues of mutual interest. Though economics and trade are usually the centerpieces of each summit’s agenda, issues like climate change, migration policies, terrorism, the future of work, or global wealth are recurring focuses too. Since the G20 leaders represent the “ political backbone of the global financial architecture that secures open markets, orderly capital flows, and a safety net for countries in difficulty”, it is often thanks to bilateral meetings during summits that major international agreements are achieved and that globalization is able to move forward.

The joint action of G20 leaders has unquestionably been useful to save the global financial system in the 2008/2009 crisis, thanks to trade barriers removal and the implementation of huge financial reforms. Nonetheless, the G20 was been struggling to be successful at coordinating monetary and fiscal policies and unable to root out tax evasion and corruption, among other downsides of globalization. As a result of this and other failures from the G20 in coordinating globalization, popular, nationalist movements across the world have been defending countries should pursue their interests alone or form fruitful coalitions.

How Do We Make Globalization More Just?

The ability of countries to rise above narrow self-interest has brought unprecedented economic wealth and plenty of applicable scientific progress. However, for different reasons, not everyone has been benefiting the same from globalization and technological change: wealth is unfairly distributed and economic growth came at huge environmental costs. How can countries rise above narrow self-interest and act together or designing fairer societies and a healthier planet? How do we make globalization more just?

According to Christine Lagarde , former President of the International Monetary Fund, “ debates about trade and access to foreign goods are as old as society itself ” and history tells us that closing borders or protectionism policies are not the way to go, as many countries doing it have failed.

Lagarde defends we should pursue globalization policies that extend the benefits of openness and integration while alleviating their side effects. How to make globalization more just is a very complex question that involves redesigning economic systems. But how? That’s the question.

Globalization is deeply connected with economic systems and markets, which, on their turn, impact and are impacted by social issues, cultural factors that are hard to overcome, regional specificities, timings of action and collaborative networks. All of this requires, on one hand, global consensus and cooperation, and on the other, country-specific solutions, apart from a good definition of the adjective “just”.

When Did Globalization Begin? The History of Globalization

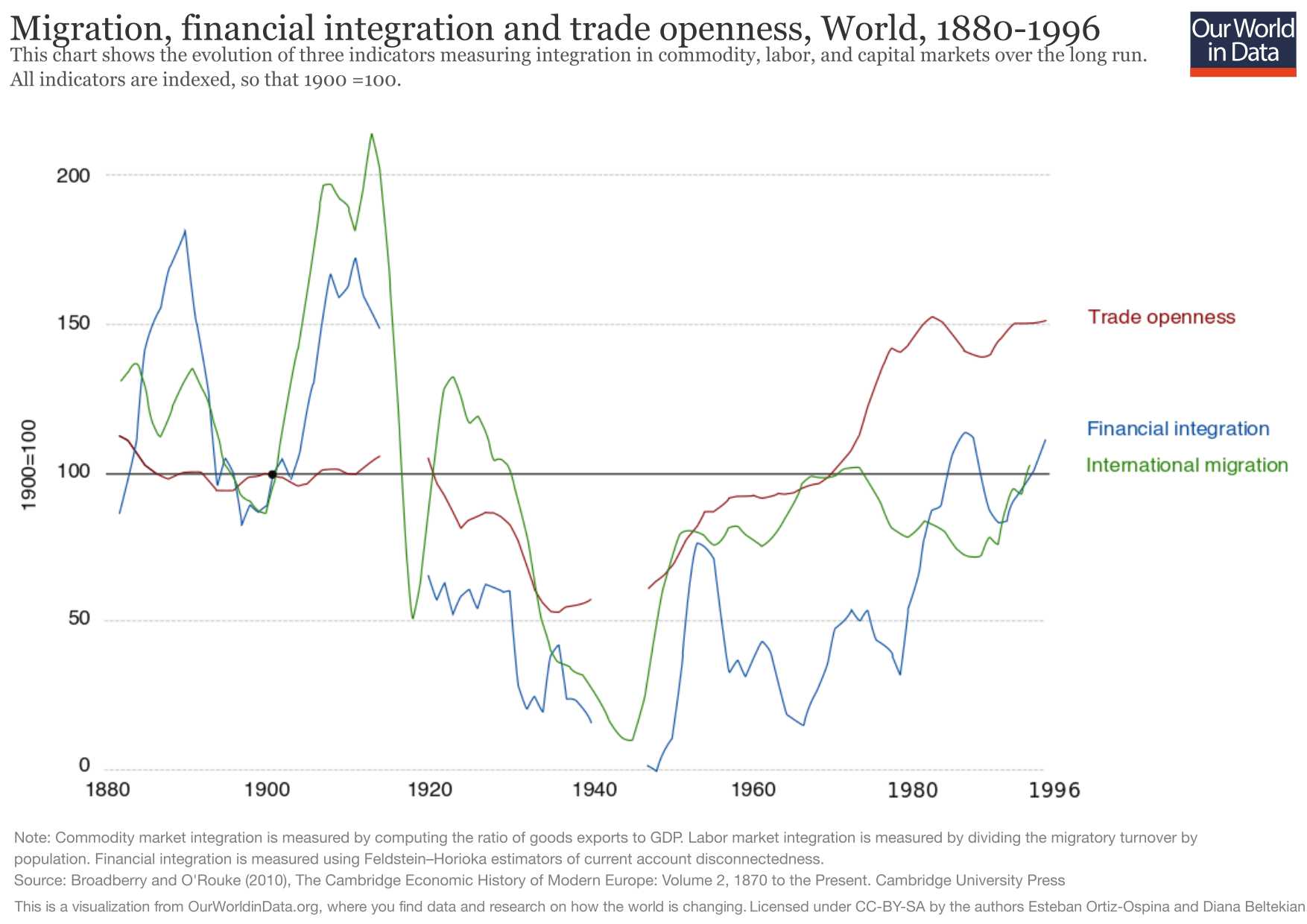

For some people, this global phenomenon is inherent to human nature. Because of this, some say globalization begun about 60,000 years ago, at the beginning of human history. Throughout time, human societies’ exchanging trade has been growing. Since the old times, different civilizations have developed commercial trade routes and experienced cultural exchanges. And as well, the migratory phenomenon has also been contributing to these populational exchanges. Especially nowadays, since traveling became quicker, more comfortable, and more affordable.

This phenomenon has continued throughout history, notably through military conquests and exploration expeditions. But it wasn’t until technological advances in transportation and communication that globalization speeded up. It was particularly after the second half of the 20th century that world trades accelerated in such a dimension and speed that the term “globalization” started to be commonly used.

- Are we living oppositely to sustainable development?

Examples of Globalization (Concept Map)

Because of trade developments and financial exchanges, we often think of globalization as an economic and financial phenomenon. Nonetheless, it includes a much wider field than just flowing of goods, services or capital. Often referred to as the globalization concept map, s ome examples of globalization are:

- Economic globalization : is the development of trade systems within transnational actors such as corporations or NGOs;

- Financial globalization : can be linked with the rise of a global financial system with international financial exchanges and monetary exchanges. Stock markets, for instance, are a great example of the financially connected global world since when one stock market has a decline, it affects other markets negatively as well as the economy as a whole.

- Cultural globalization : refers to the interpenetration of cultures which, as a consequence, means nations adopt principles, beliefs, and costumes of other nations, losing their unique culture to a unique, globalized supra-culture;

- Political globalization : the development and growing influence of international organizations such as the UN or WHO means governmental action takes place at an international level. There are other bodies operating a global level such as NGOs like Doctors without borders or Oxfam ;

- Sociological globalization : information moves almost in real-time, together with the interconnection and interdependence of events and their consequences. People move all the time too, mixing and integrating different societies;

- Technological globalization: the phenomenon by which millions of people are interconnected thanks to the power of the digital world via platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Skype or Youtube.

- Geographic globalization: is the new organization and hierarchy of different regions of the world that is constantly changing. Moreover, with transportation and flying made so easy and affordable, apart from a few countries with demanding visas, it is possible to travel the world without barely any restrictions;

- Ecological globalization: accounts for the idea of considering planet Earth as a single global entity – a common good all societies should protect since the weather affects everyone and we are all protected by the same atmosphere. To this regard, it is often said that the poorest countries that have been polluting the least will suffer the most from climate change .

The Benefits of Globalization

Globalization has benefits that cover many different areas. It reciprocally developed economies all over the world and increased cultural exchanges. It also allowed financial exchanges between companies, changing the paradigm of work. Many people are nowadays citizens of the world. The origin of goods became secondary and geographic distance is no longer a barrier for many services to happen. Let’s dig deeper.

The Engine of Globalization – An Economic Example

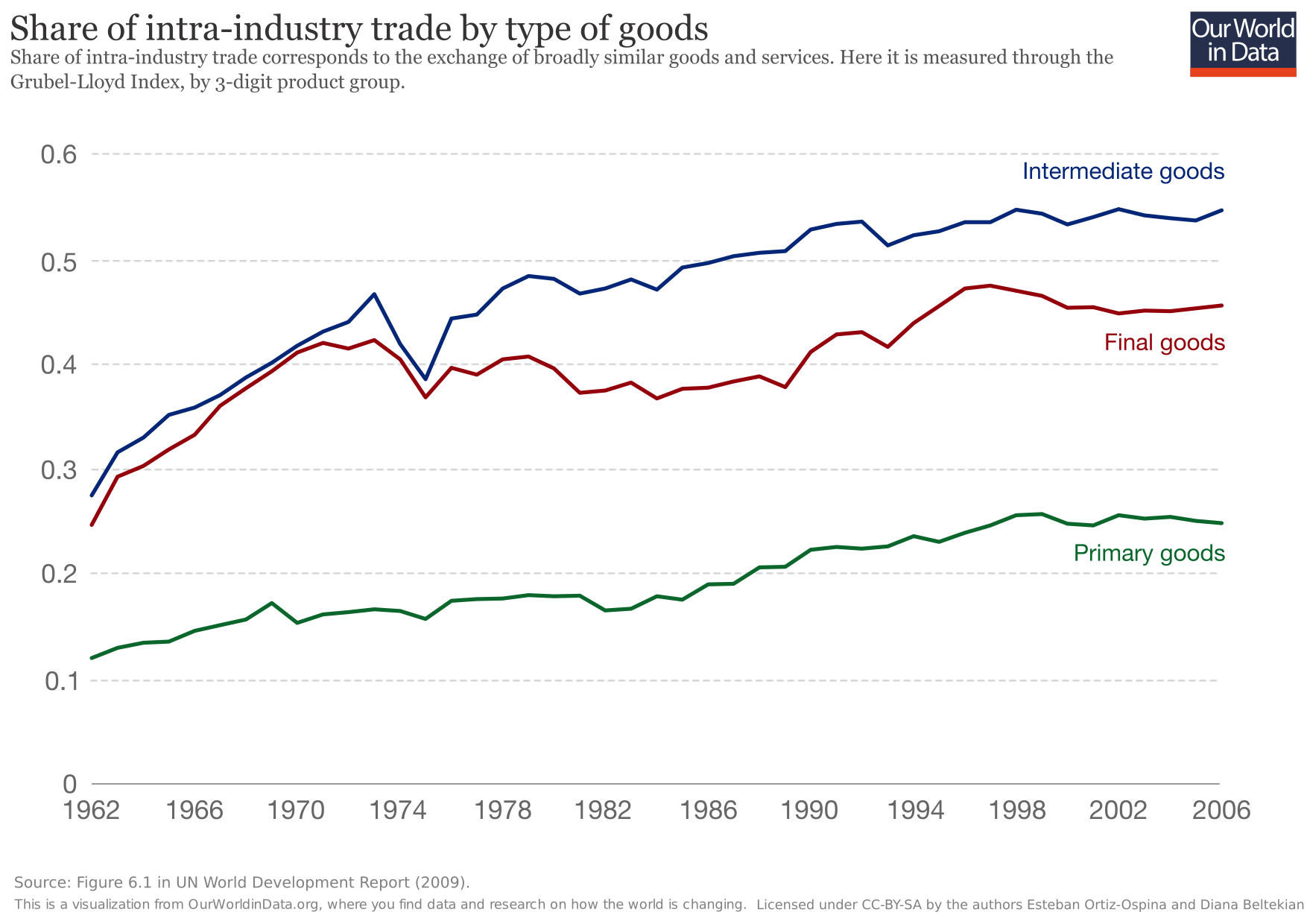

The most visible impacts of globalization are definitely the ones affecting the economic world. Globalization has led to a sharp increase in trade and economic exchanges, but also to a multiplication of financial exchanges.

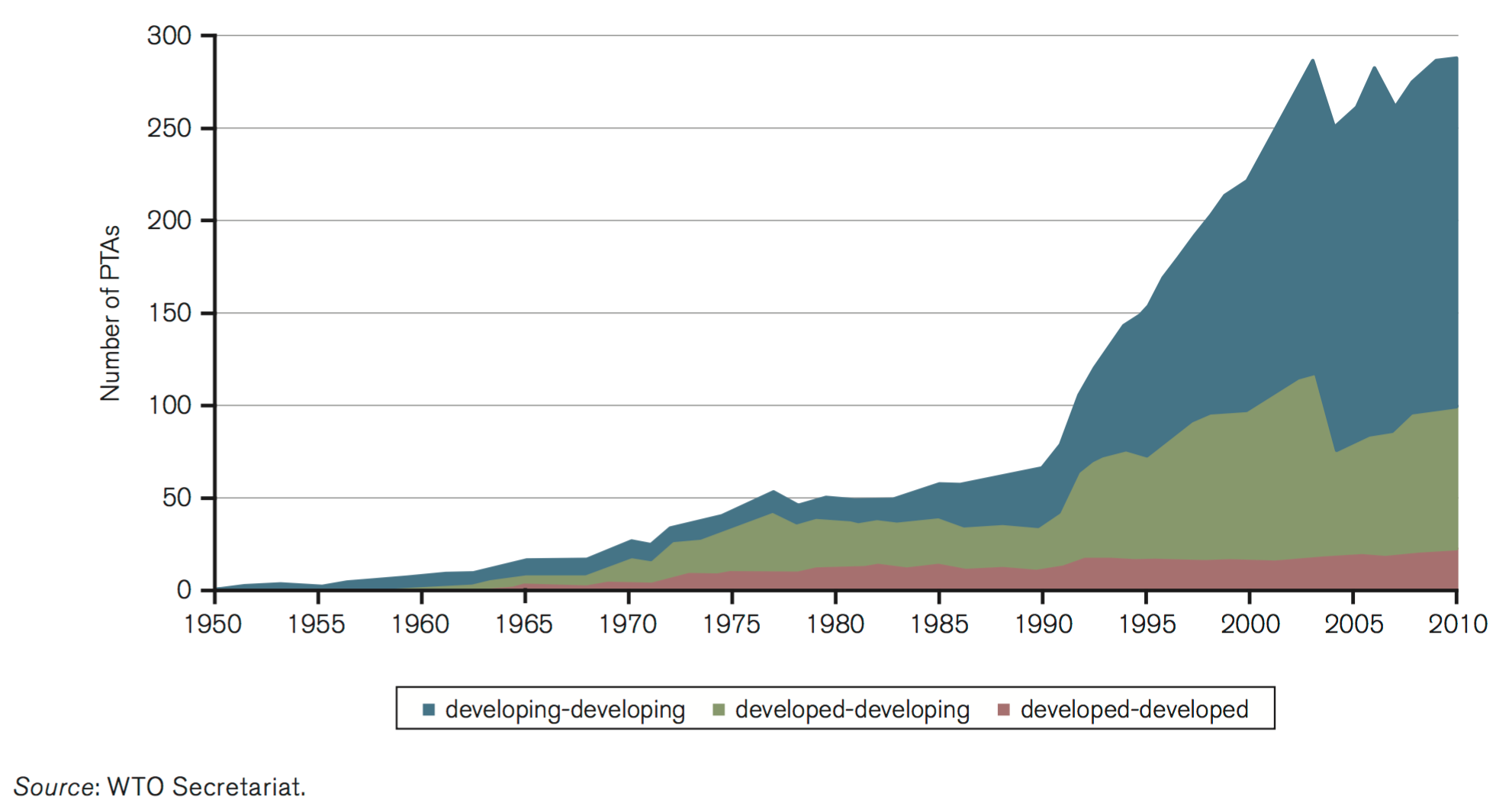

In the 1970s world economies opened up and the development of free trade policies accelerated the globalization phenomenon. Between 1950 and 2010, world exports increased 33-fold. This significantly contributed to increasing the interactions between different regions of the world.

This acceleration of economic exchanges has led to strong global economic growth. It fostered as well a rapid global industrial development that allowed the rapid development of many of the technologies and commodities we have available nowadays.

Knowledge became easily shared and international cooperation among the brightest minds speeded things up. According to some analysts, globalization has also contributed to improving global economic conditions, creating much economic wealth (thas was, nevertheless, unequally distributed – more information ahead).

Globalization Benefits – A Financial Example

At the same time, finance also became globalized. From the 1980s, driven by neo-liberal policies, the world of finance gradually opened. Many states, particularly the US under Ronald Reagan and the UK under Margaret Thatcher introduced the famous “3D Policy”: Disintermediation, Decommissioning, Deregulation.

The idea was to simplify finance regulations, eliminate mediators and break down the barriers between the world’s financial centers. And the goal was to make it easier to exchange capital between the world’s financial players. This financial globalization has contributed to the rise of a global financial market in which contracts and capital exchanges have multiplied.

Globalization – A Cultural Example

Together with economic and financial globalization, there has obviously also been cultural globalization. Indeed, the multiplication of economic and financial exchanges has been followed by an increase in human exchanges such as migration, expatriation or traveling. These human exchanges have contributed to the development of cultural exchanges. This means that different customs and habits shared among local communities have been shared among communities that (used to) have different procedures and even different beliefs.

Good examples of cultural globalization are, for instance, the trading of commodities such as coffee or avocados. Coffee is said to be originally from Ethiopia and consumed in the Arabid region. Nonetheless, due to commercial trades after the 11th century, it is nowadays known as a globally consumed commodity. Avocados , for instance, grown mostly under the tropical temperatures of Mexico, the Dominican Republic or Peru. They started by being produced in small quantities to supply the local populations but today guacamole or avocado toasts are common in meals all over the world.

At the same time, books, movies, and music are now instantaneously available all around the world thanks to the development of the digital world and the power of the internet. These are perhaps the greatest contributors to the speed at which cultural exchanges and globalization are happening. There are also other examples of globalization regarding traditions like Black Friday in the US , the Brazilian Carnival or the Indian Holi Festival. They all were originally created following their countries’ local traditions and beliefs but as the world got to know them, they are now common traditions in other countries too.

Why Is Globalization Bad? The Negative Effects of Globalization

Globalization is a complex phenomenon. As such, it has a considerable influence on several areas of contemporary societies. Let’s take a look at some of the main negative effects globalization has had so far.

The Negative Effects of Globalization on Cultural Loss

Apart from all the benefits globalization has had on allowing cultural exchanges it also homogenized the world’s cultures. That’s why specific cultural characteristics from some countries are disappearing. From languages to traditions or even specific industries. That’s why according to UNESCO , the mix between the benefits of globalization and the protection of local culture’s uniqueness requires a careful approach.

The Economic Negative Effects of Globalization

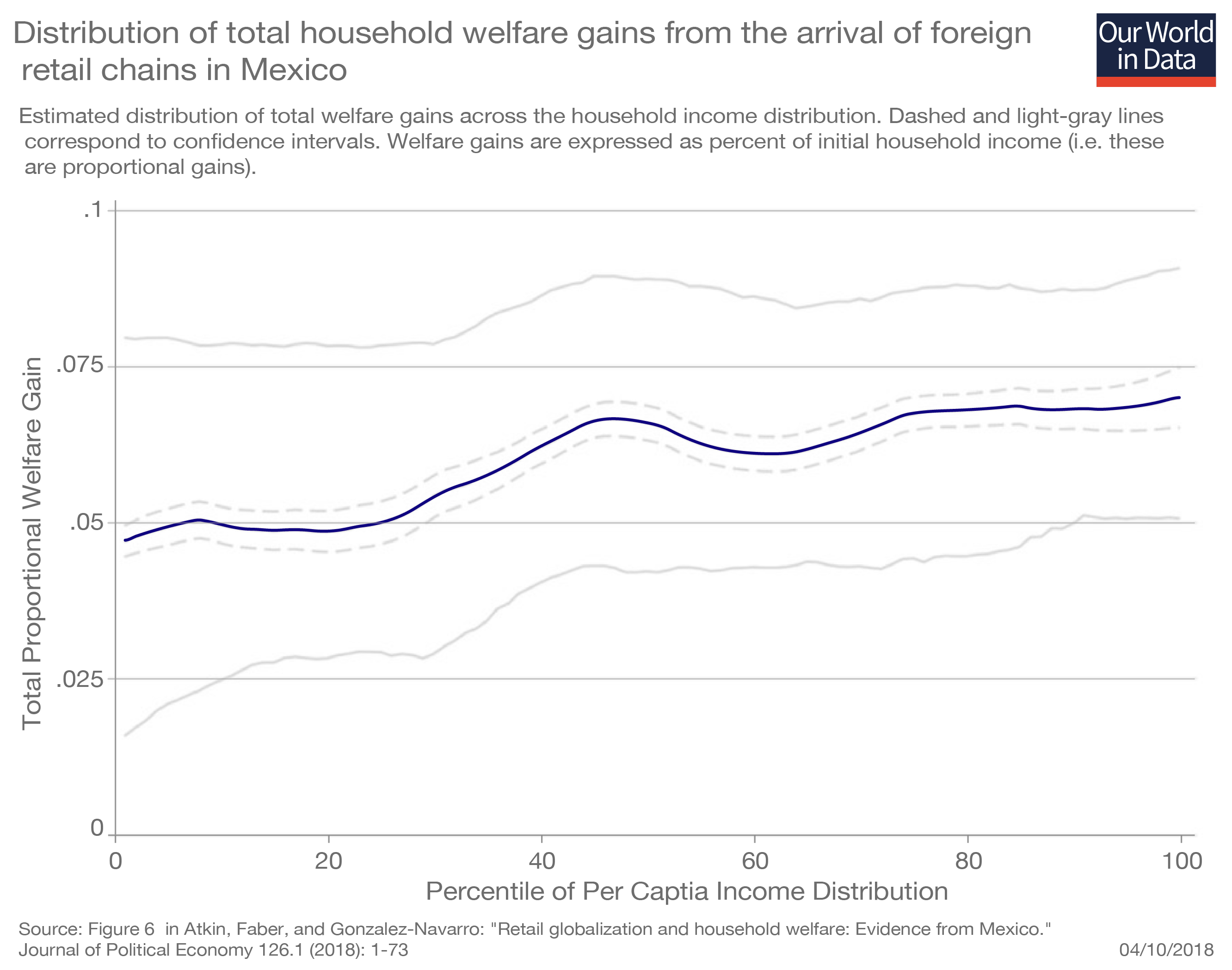

Despite its benefits, the economic growth driven by globalization has not been done without awakening criticism. The consequences of globalization are far from homogeneous: income inequalities, disproportional wealth and trades that benefit parties differently. In the end, one of the criticisms is that some actors (countries, companies, individuals) benefit more from the phenomena of globalization, while others are sometimes perceived as the “losers” of globalization. As a matter of fact, a recent report from Oxfam says that 82% of the world’s generated wealth goes to 1% of the population.

- Related: Globally, Business And Government Lack Trust, A New Survey Shows

The Negative Effects of Globalization on the Environment

At the same time, global economic growth and industrial productivity are both the driving force and the major consequences of globalization. They also have big environmental consequences as they contribute to the depletion of natural resources, deforestation and the destruction of ecosystems and loss of biodiversity . The worldwide distribution of goods is also creating a big garbage problem, especially on what concerns plastic pollution .

- How Air Pollution And Diabetes Kill Millions Every Year

- Changing Aircrafts’ Altitude To Reduce The Climatic Impact Of Contrails

- Are Avocados Truly Sustainable?

Globalization, Sustainable Development, and CSR

Globalization affects all sectors of activity to a greater or lesser extent. By doing so, its gap with issues that have to do with sustainable development and corporate social responsibility is short.

By promoting large-scale industrial production and the globalized circulation of goods, globalization is sometimes opposed to concepts such as resource savings, energy savings or the limitation of greenhouse gases . As a result, critics of globalization often argue that it contributes to accelerating climate change and that it does not respect the principles of ecology. At the same time, big companies that don’t give local jobs and choose instead to use the manpower of countries with low wages (to have lower costs) or pay taxes in countries with more favorable regulations is also opposed to the criteria of a CSR approach. Moreover, the ideologies of economic growth and the constant pursuit of productivity that come along with globalization, also make it difficult to design a sustainable economy based on resilience .

On the other hand, globalization is also needed for the transitioning to a more sustainable world, since only a global synergy would really be able to allow a real ecological transition. Issues such as global warming indeed require a coordinated response from all global players: fight against CO2 emissions, reduction of waste, a transition to renewable energies . The same goes for ocean or air pollution, or ocean acidification, problems that can’t be solved without global action. The dissemination of green ideas also depends on the ability of committed actors to make them heard globally.

- What Are The Benefits Of Having A Network Of CSR Ambassadors?

- 5 Tips For Organizations To Develop Their CSR Strategy In 2020

- Top 10 Companies With The Best Corporate (CSR) Reputation In 2020

The Road From Globalization to Regionalization

Regionalization can also be analyzed from a corporate perspective. For instance, businesses such as McDonald’s or Starbucks don’t sell exactly the same products everywhere. In some specific stores, they consider people’s regional habits. That’s why the McChicken isn’t sold in India, whereas in Portugal there’s a steak sandwich menu like the ones you can get in a typical Portuguese restaurant.

Politically speaking, when left-wing parties are in power they tend to focus on their country’s people, goods and services. Exchanges with the outside world aren’t seen as very valuable and importations are often left aside.

- Related: Why Is It Important To Support Local And Small Businesses?

Globalization Quotes by World Influencers

Many world leaders, decision-makers and influential people have spoken about globalization. Some stand out its positive benefits and others focus deeper on its negative effects. Find below some of the most interesting quotes on this issue.

Politic Globalization Quotes

Globalization quote by the former U.S President Bill Clinton ??

No generation has had the opportunity, as we now have, to build a global economy that leaves no-one behind. It is a wonderful opportunity, but also a profound responsibility.

Globalization quote by Barack Obama , former U.S. president ??

Globalization is a fact, because of technology, because of an integrated global supply chain, because of changes in transportation. And we’re not going to be able to build a wall around that.

Globalization quote by Dominique Strauss-Kahn, former International Monetary Fund Managing Director ??

“We can’t speak day after day about globalization without at the same time having in mind that…we need multilateral solutions.”

Globalization quote by Stephen Harper , former Prime Minister of Canada ??

“We have to remember we’re in a global economy. The purpose of fiscal stimulus is not simply to sustain activity in our national economies but to help the global economy as well, and that’s why it’s so critical that measures in those packages avoid anything that smacks of protectionism.”

Globalization quote by Julia Gillard , Prime Minister of Australia ??

“My guiding principle is that prosperity can be shared. We can create wealth together. The global economy is not a zero-sum game.”

Other Globalization Quotes

Globalization quote by the spiritual leader Dalai Lama ??

“I find that because of modern technological evolution and our global economy, and as a result of the great increase in population, our world has greatly changed: it has become much smaller. However, our perceptions have not evolved at the same pace; we continue to cling to old national demarcations and the old feelings of ‘us’ and ‘them’.”

The famous German sociologist Ulrich Beck also spoke of globalization ??

“Globalization is not only something that will concern and threaten us in the future, but something that is taking place in the present and to which we must first open our eyes.”

Globalization quote by Bill Gates, owner and former CEO of Microsoft ??

“The fact is that as living standards have risen around the world, world trade has been the mechanism allowing poor countries to increasingly take care of really basic needs, things like vaccination.”

Globalization quote by John Lennon, member of the music band The Beatles ??

Imagine there’s no countries. It isn’t hard to do. Nothing to kill or die for. And no religion, too. Imagine all the people. Living life in peace. You, you may say I’m a dreamer. But I’m not the only one. I hope someday you will join us. And the world will be as one

Effects of Economic Globalization

Globalization has led to increases in standards of living around the world, but not all of its effects are positive for everyone.

Social Studies, Economics, World History

Bangladesh Garment Workers

The garment industry in Bangladesh makes clothes that are then shipped out across the world. It employs as many as four million people, but the average worker earns less in a month than a U.S. worker earns in a day.

Photograph by Mushfiqul Alam

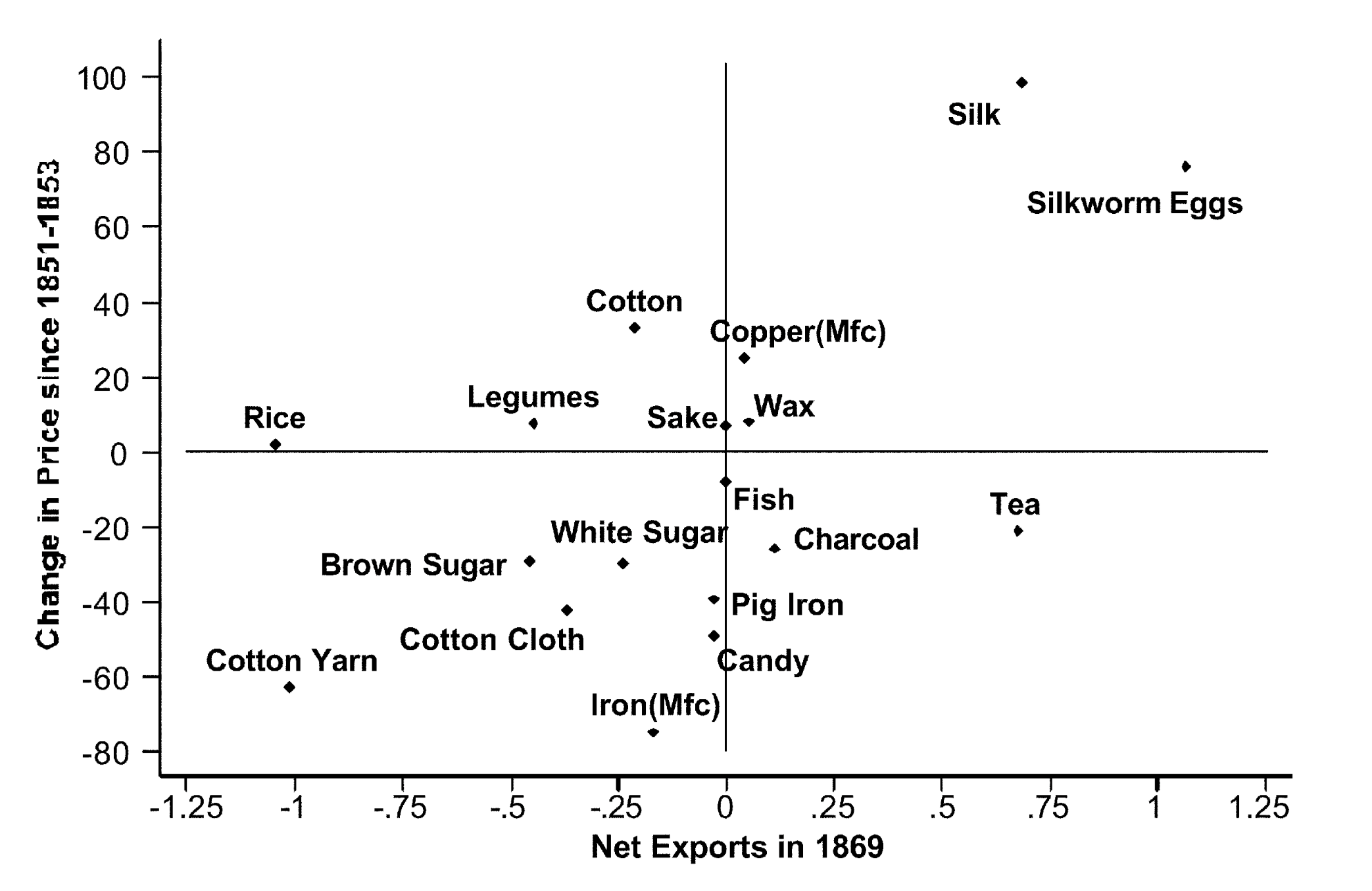

Put simply, globalization is the connection of different parts of the world. In economics, globalization can be defined as the process in which businesses, organizations, and countries begin operating on an international scale. Globalization is most often used in an economic context, but it also affects and is affected by politics and culture. In general, globalization has been shown to increase the standard of living in developing countries, but some analysts warn that globalization can have a negative effect on local or emerging economies and individual workers. A Historical View Globalization is not new. Since the start of civilization, people have traded goods with their neighbors. As cultures advanced, they were able to travel farther afield to trade their own goods for desirable products found elsewhere. The Silk Road, an ancient network of trade routes used between Europe, North Africa, East Africa, Central Asia, South Asia, and the Far East, is an example of early globalization. For more than 1,500 years, Europeans traded glass and manufactured goods for Chinese silk and spices, contributing to a global economy in which both Europe and Asia became accustomed to goods from far away. Following the European exploration of the New World, globalization occurred on a grand scale; the widespread transfer of plants, animals, foods, cultures, and ideas became known as the Columbian Exchange. The Triangular Trade network in which ships carried manufactured goods from Europe to Africa, enslaved Africans to the Americas, and raw materials back to Europe is another example of globalization. The resulting spread of slavery demonstrates that globalization can hurt people just as easily as it can connect people. The rate of globalization has increased in recent years, a result of rapid advancements in communication and transportation. Advances in communication enable businesses to identify opportunities for investment. At the same time, innovations in information technology enable immediate communication and the rapid transfer of financial assets across national borders. Improved fiscal policies within countries and international trade agreements between them also facilitate globalization. Political and economic stability facilitate globalization as well. The relative instability of many African nations is cited by experts as one of the reasons why Africa has not benefited from globalization as much as countries in Asia and Latin America. Benefits of Globalization Globalization provides businesses with a competitive advantage by allowing them to source raw materials where they are inexpensive. Globalization also gives organizations the opportunity to take advantage of lower labor costs in developing countries, while leveraging the technical expertise and experience of more developed economies. With globalization, different parts of a product may be made in different regions of the world. Globalization has long been used by the automotive industry , for instance, where different parts of a car may be manufactured in different countries. Businesses in several different countries may be involved in producing even seemingly simple products such as cotton T-shirts. Globalization affects services, too. Many businesses located in the United States have outsourced their call centers or information technology services to companies in India. As part of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), U.S. automobile companies relocated their operations to Mexico, where labor costs are lower. The result is more jobs in countries where jobs are needed, which can have a positive effect on the national economy and result in a higher standard of living. China is a prime example of a country that has benefited immensely from globalization. Another example is Vietnam, where globalization has contributed to an increase in the prices for rice, lifting many poor rice farmers out of poverty. As the standard of living increased, more children of poor families left work and attended school. Consumers benefit also. In general, globalization decreases the cost of manufacturing . This means that companies can offer goods at a lower price to consumers. The average cost of goods is a key aspect that contributes to increases in the standard of living. Consumers also have access to a wider variety of goods. In some cases, this may contribute to improved health by enabling a more varied and healthier diet; in others, it is blamed for increases in unhealthy food consumption and diabetes. Downsides Not everything about globalization is beneficial. Any change has winners and losers, and the people living in communities that had been dependent on jobs outsourced elsewhere often suffer. Effectively, this means that workers in the developed world must compete with lower-cost markets for jobs; unions and workers may be unable to defend against the threat of corporations that offer the alternative between lower pay or losing jobs to a supplier in a less expensive labor market. The situation is more complex in the developing world, where economies are undergoing rapid change. Indeed, the working conditions of people at some points in the supply chain are deplorable. The garment industry in Bangladesh, for instance, employs an estimated four million people, but the average worker earns less in a month than a U.S. worker earns in a day. In 2013, a textile factory building collapsed, killing more than 1,100 workers. Critics also suggest that employment opportunities for children in poor countries may increase negative impacts of child labor and lure children of poor families away from school. In general, critics blame the pressures of globalization for encouraging an environment that exploits workers in countries that do not offer sufficient protections. Studies also suggest that globalization may contribute to income disparity and inequality between the more educated and less educated members of a society. This means that unskilled workers may be affected by declining wages, which are under constant pressure from globalization. Into the Future Regardless of the downsides, globalization is here to stay. The result is a smaller, more connected world. Socially, globalization has facilitated the exchange of ideas and cultures, contributing to a world view in which people are more open and tolerant of one another.

Articles & Profiles

Media credits.

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

February 20, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The State of Globalization in 2021

- Steven A. Altman

- Caroline R. Bastian

Trade, capital, and information flows have stabilized, recovered, and even grown in the past year.

As the coronavirus swept the world, closing borders and halting international trade and capital flows, there were questions about the pandemic’s lasting impact on globalization. But a close look at the recent data paints a much more optimistic picture. While international travel remains significantly down and is not expected to rebound until 2023, cross-border trade, capital, and information flows have largely stabilized, recovered, or even grown over the last year. The bottom line for business is that Covid-19 has not knocked globalization down to anywhere close to what would be required for strategists to narrow their focus to their home countries or regions.

Cross-border flows plummeted in 2020 as the Covid-19 pandemic swept the world, reinforcing doubts about the future of globalization. As we move into 2021, the latest data paint a clearer — and more hopeful — picture. Global business is not going away, but the landscape is shifting, with important implications for strategy and management.

- Steven A. Altman is a senior research scholar, adjunct assistant professor, and director of the DHL Initiative on Globalization at the NYU Stern Center for the Future of Management .

- CB Caroline R. Bastian is a research scholar at the DHL Initiative on Globalization.

Partner Center

The Effect of Globalization on a World Culture Essay

Introduction, globalization and culture.

Scientific innovations and inventions have accelerated the growth of globalization. Nations can easily trade, socialize, share ideas, and assist each other in different spheres of life.

Improved international relations have enabled the movement of factors of production among nations with minimal barriers to trade. The cooperation has led to social, political, and economical globalization; although neither of the above three classifications of globalization have been fully attained, their effects can be felt in economic, political, and social spheres of life.

Critics of globalization appreciate that it has positive effect on economic wellbeing of countries. However they are quick to point out that globalization has high culture and identity loss/costs (Sheila 56). They are of the opinion that modernization has the potential of running roughshod over the world’s distinctive cultures and creates a single world which resembles a tawdry mall. This paper discuses the effect of globalization on a world culture.

Culture is the identity of people that any member adheres to. It has some defined attributes, some of them are written and others are not. The set way of operation that is governed by some cultural, communal, and societal goals assists in holding people together and creates a norm in the community.

When people trade, socialize or interact with each other in a way it has been enabled by globalization, there is the tendency that they will lose their identity and inherit a system of operation or a certain mode of conduct that is generally accepted by the community (in this instance, the word community has been used to refer to the larger global community created by globalization).

According to Tyler Cowen, modernization and cultural globalization have resulted into the growth of creativity, innovation, and invention among communities. When people interact, they tend to learn the other parties’ way of operation and the difference is likely to trigger some creative mind for the benefit of the two parties.

The above observation by Tyler Cowen can be interpolated either negatively or positively; from a positive angle, modernization has created a room for invention and innovation. On a negative note, the world is utilizing the differences it has as failing to create more differences that future generation is likely to run out of creative mind, as there will be lack of motivation in the form of current culture differences.

For example, in the 1950s, Cuban Music and Reggae was produced in Cuba with the target consumers as American Tourists who visited the country. In Cuba, the style of music was part of their tradition that the Americans loved to sing along. With diffusion of culture and more exposure, the style of music has been adopted by the Americans, and today it is played in modern clubs and bars.

Today, if a Cuban was to visit the United States, he or she was likely to feel accommodated by the structures as there are some similar attributes that he/she gets. In either French or German restaurants, a shopper is able to buy Sushi (Japanese foods consisting of cooked vinegared rice (shari) combined with other ingredients (neta)). Such a move shows how Japanese have been accommodated in both European countries (Sheila 256).

With cultural globalization, people of different cultures, ethnicities, nationalities, religions, and values find themselves in the same atmosphere where no one has the freedom to fully adhere or practice his culture. With such kind of setting, the most probable thing that can happen is people to develop a set of culture that will assist them transact business despite their differences.

The net result is a global culture; the effect and extent that global culture has gone in the world varied among nations and continents; developed countries have their culture more diffused and uniformity can be seen from their way of operation. In developing countries, there is a tendency of resistance to change the culture, but the force therein is strong. Efforts to change the culture of people are not deliberate, but they are necessitated by the prevailing condition in the world.

In contemporary business environments, organizations hire employees of different nationalities, ethnic backgrounds, cultural believes, intellectual capacity, and age. The nature and mix of employees calls for management to develop policies and management mechanisms that will gain from the differences in their human capital; to manage the diverse personnel, business leaders need to adopt international human resources management strategy (IHRM).

The policies that organizations embark on should entail policies that address diverse human resource issues; organization stands to benefit from diversity if the right management policies are set in place, but there is the risk that the differences create uniform business practice. With diffusion of cultures, management can enact some common human resource policies that cut across its diverse human capital. However, care should be exercised since chances of repellence in the event policies seem to be confronting with culture of people.

When managing human capital of different nationalities, businesses leaders should make policies that can assist in tapping their organization’s personnel’s intellectual capacity, as it grows their talents and skills. Culture is likely to affect people in different spheres, thus when companies have diverse human resources, they have to ensure that their programs are sensitive to the differences in culture and beliefs.

When working in different countries, management should never assume that the human management style adopted in the country is fully-effective and applicable to another country; they should take their time, understand what the other country’s employee value and consider best. Management gurus continue to offer insights of how culture and ethnicity of a people affect their performance in their works; they have suggested culture intelligence to assist organization handle their employees effectively regardless of their nationality.

When making business decisions, the culture and exposure that someone has is likely to affect the kind of decision that he is going to make; people who are exposed to the right materials through televisions, the internet, and print media are likely to make more informed decisions. With culture globalization, there has been exposure to different settings and information is available through the assistance of communication channels; the resultant community is an informed community that can make quality decisions for the exploitation of available resources effectively.

Differences in norms and culture among different ethnicity, nationalities, and communities has been a hindrance to effective trade, to some extent, the differences have acted as non tariff barriers that has hindered the development of trade.

When people interact and change their cultural beliefs to adopt a uniform set of beliefs, they are breaking the unseen barriers of trade and create a room for more business, ideas, equality, and economic development. For example, among the Muslims, Women had been regarded as inferior to men and they could hardly be allowed to take leadership positions.

With the interaction with Christians and getting their take on the same, there has been a wave in the community that has enabled them to seek leadership positions like men have. The above case has shown how culture globalization has created opportunities to different people and enabled women to get more opportunities. In the developed worlds, the state and position of the woman had been respected long before the same was done in developing worlds.

As the developed and developing countries trade among each other, the developing countries are getting into the system and women have started to have their positions in the communities. Gender differences has been minimized by globalization, there has been the reduction on gender differences among communities were human beings can now relate more as people not on gender grounds as the case had been when culture globalization was not adhered to.

The rights of girl child campaigns have gained roots in different countries as culture diffuses to reinforce and create awareness to the need to protect women and reduce gender differences that have prevailed among communities for a lengthy duration.

When people of different cultures interact, they develop the sense of togetherness and there are shared common interests that are developed; globalization has enabled the interaction, as well as sharing of ideas, opinions, view points and ways of doing things in a way that facilitates trade. Trade prevails better when the trading partners have some common values, attributes, and beliefs.

Culture globalization has enabled people to have the same perception and attitude towards similar products; with the similarity, peace and harmony in doing and handling issues have been developed. When there is peace and harmony, business and trade prevail effectively.

When people share culture, it means that when someone is in a geographical location different from his or hers, coping will be easy as there will be likelihood that the person will get something that is the same with what he or she beliefs.

For example, although the Chinese food is different from American food, a Chinese visiting the United States only need to establish the restaurant selling Chinese food as the nature and the diversity has been accepted by both the communities. Sales and marketers have much to benefit from globalized world, they can easily develop new formats and marketing strategies developed can be similar and message passed remains the same.

According to Benjamin Barber, one of the main challenges that have been brought about by globalization is culture borrowing and culture mimicry; with the borrowing and mimicry people have lost their sense of identity that someone can manage to treat his brother wrongly and hide under the new system of global culture.

Although culture globalization has not been fully attained, there are moves that indicate that its full operation cannot happen. In areas like religion (religion is an aspect of culture), changing people’s religious believes have been a challenge. The existence of some elements that can hardly change results to the notion of global culture being a mere statement by advocators of the integration, the situation cannot be attained.

Some industries in the globe exist because of differences in culture of people, for example, the tourism industry is much dependent on the cultural differences of people in different places. With culture diffusion, the industry is likely to suffer a huge blow.

In Kenya, the East African country whose tourism is the second earner of the foreign exchange has multicultural where the tourisms from different countries visit to enjoy and learn the diversity of the country’s population.

The move to global culture is thus likely to injure some industries while supporting others. Culture within communities is supported by generally agreed attributes that passes from one generation to another. The “nature of passing” of modern global culture is challenging as people or the global community has not set mechanisms to pass the culture, reinforce, or even punish offender.

To pass the global culture, the materials that young generation become exposed to modern methods of passing information like television, radio, the internet, peers, and written materials. When such materials have been used to pass culture, there are high chances that young generation will get reinforcement of culture which is not good. Global culture is more likely to be for the larger global community benefit, but rarely does it address issue of an individual.

With the structures and development of global culture, there cannot be said to have an effective method of culture reinforcement or a system to punish offender. This means that the culture is vulnerable to changes and hicks ups. Any small attribute or change in the global world is likely to shake the culture of the people since it’s not based on a strong foundation.

With globalization, companies can work in different parts of the world as multinationals; however they have to be sensitive to the nature of products, services, and structure of employees they deploy. Multinationals generally have three main methods to get their employees on board, they use a localization approach, expatriates approach, and a third country approach.

To maintain quality and quantity workforce, the management should ensure that they are aware of the culture of people and manage them effectively. The challenge that multinationals have is putting the notion that with culture globalization, there is uniformity, thus there is no need to have culture intelligence and culture awareness programs.

For example, Pepsi has been a major competitor in the American industry as its style is more American, however the brand has not maintained strong competitiveness in African countries since its style of marketing and sales fails to meet the needs of the continents culture. The above example shows how the notion of global culture has been mis-interpolated (Sheila 256).

Other than human resources, department maintaining qualified and efficient human capital at the most affordable cost possible, they have the role of ensuring they combine their human capital in a manner that will benefit the entire organization.

Diversity and difference in culture by itself offers an organization rich knowledge, opinions, values, and experience, with culture globalization such important attributes to business competitiveness are lost; before an organization decides to fill a certain vacancy in its system, the human resources should liaise with the departmental heads to know exactly the kind of qualification that are sort for, in some instances, the management may advice for some age gap, nationality, gender, and experience.

It is through effective recruitment that an organization can build an effective team that meets its personnel requirement needs. When enacting empowerment and motivational policies or schemes, the management should ensure that the diversity of its employees has been considered.

There are people who are generally team-players, others prefer individualism, and others are charismatic leaders. When making decision, it is important to consider the diversity. Management gurus has continually advised companies to have culture coaches when operating in a country they are not very sure of the nature and the culture of the people; with the coaches, they can develop orchestrate teams and make products that meet the requirement of customers in the country.

Diverse human resource can be biennial to an organization is managed effectively; failure to manage diversity effectively means exposure to risks. Management gurus have continued to support the use of culture intelligence and culture awareness programs to support the culture awareness within organizations; those companies that have undertaken the advice are doing better than those who have not.

Although cultural globalization has build strong operating base through which trade can prevail, it has brought some challenges to the world and the people in general. The lack of identity has resulted into sharing of values likely to dilute societal values and norms.

When the community lacks strong values that are maintained with a certain mechanism, the result is a disintegrated society were social evils are the order of the day. For example, in developed countries, one of the vises that the countries are dealing with is use of drugs and substance abuse by young people.

Although this is taken as a normal condition or social evil, psychologists have suggested that lack of strong values and low behavior standards by young people can be to blame. When the blame is further analyzed, it is seen that parents are not able to raise morally upright children as they have less regard to their cultural beliefs and practices which they consider to have been eroded by globalization.

With diffusion of cultures, there is less emphasis on family and societal values, parents and the community in general seem to ignore the need to maintain, pass and transfer culture to younger generations. When culture is not transferred, children are exposed to new global culture that might be different from the norm.

The results are the families that have low moral standards and which values are questionable. Generally, organizations require physical, human, and informational resources for their operation; business-leaders should realize that human capital is the most crucial capital their organizations have.

In a modern globalized world, organizations have diverse human capital; to manage the capital effectively, companies need to adopt international human resources management strategy. The strategy assists an organization benefit from its personnel diversity as it mitigates risks associated with a diverse workforce. With culture globalization the workforce seems to have the same ideologies an attributes that hinder creativity, innovation, and invention (Sheila 56-78).

Globalization has resulted into culture diffusion, culture sharing, and multiculturalism; the uniformity in culture facilitates trade among nations and promotes international relations and understanding.

However, multiculturalism has been blamed of dilution of people’s cultural values, norms, and virtues. Multiculturalism has also been challenged as a mere statement by business philosophers that will not be attained in the near future as family structures vary among different parts of the globe.

Sheila, Lucy. Globalization and Belonging: The Politics of Identity in a Changing World . London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, October 25). The Effect of Globalization on a World Culture. https://ivypanda.com/essays/globalization-and-culture/

"The Effect of Globalization on a World Culture." IvyPanda , 25 Oct. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/globalization-and-culture/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'The Effect of Globalization on a World Culture'. 25 October.

IvyPanda . 2018. "The Effect of Globalization on a World Culture." October 25, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/globalization-and-culture/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Effect of Globalization on a World Culture." October 25, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/globalization-and-culture/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Effect of Globalization on a World Culture." October 25, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/globalization-and-culture/.

- Android Platform and Diffusion of Innovations

- Diffusion of Innovation: Key Aspects

- Discussion about diffusion of innovation

- Clothing and Culture

- Coping With Cultural Shock and Adaptation to a New Culture

- American Cultural Imperialism in the Film Industry Is Beneficial to the Canadian Society

- Popular Culture: The Use of Phones and Texting While Driving

- Culture Jamming

- Open access

- Published: 03 August 2005

The health impacts of globalisation: a conceptual framework

- Maud MTE Huynen 1 ,

- Pim Martens 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Henk BM Hilderink 4

Globalization and Health volume 1 , Article number: 14 ( 2005 ) Cite this article

391k Accesses

116 Citations

24 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper describes a conceptual framework for the health implications of globalisation. The framework is developed by first identifying the main determinants of population health and the main features of the globalisation process. The resulting conceptual model explicitly visualises that globalisation affects the institutional, economic, social-cultural and ecological determinants of population health, and that the globalisation process mainly operates at the contextual level, while influencing health through its more distal and proximal determinants. The developed framework provides valuable insights in how to organise the complexity involved in studying the health effects resulting from globalisation. It could, therefore, give a meaningful contribution to further empirical research by serving as a 'think-model' and provides a basis for the development of future scenarios on health.

Introduction

Good health for all populations has become an accepted international goal and we can state that there have been broad gains in life expectancy over the past century. But health inequalities between rich and poor persist, while the prospects for future health depend increasingly on the relative new processes of globalisation. In the past globalisation has often been seen as a more or less economic process. Nowadays it is increasingly perceived as a more comprehensive phenomenon, which is shaped by a multitude of factors and events that are reshaping our society rapidly. This paper describes a conceptual framework for the effects of globalisation on population health. The framework has two functions: serving as 'think-model', and providing a basis for the development of future scenarios on health.

Two recent and comprehensive frameworks concerning globalisation and health are the ones developed by Woodward et al. [ 1 ], and by Labonte and Togerson [ 2 ]. The effects that are identified by Woodward et al. [ 1 ] as most critical for health are mainly mediated by economic factors. Labonte and Torgerson [ 2 ] primarily focus on the effects of economic globalisation and international governance. In our view, however, the pathways from globalisation to health are more complex. Therefore, a conceptual framework for the health effects of the globalisation process requires a more holistic approach and should be rooted in a broad conception of both population health and globalisation. The presented framework is developed in the following three steps: 1) defining the concept of population health and identifying its main determinants, 2) defining the concept of globalisation and identifying its main features and 3) constructing the conceptual model for globalisation and population health.

Population health

As the world around us is becoming progressively interconnected and complex, human health is increasingly perceived as the integrated outcome of its ecological, social-cultural, economic and institutional determinants. Therefore, it can be seen as an important high-level integrating index that reflects the state-and, in the long term, the sustainability-of our natural and socio-economic environments [ 3 ]. This paper primarily focuses on the physical aspects of population health like mortality and physical morbidity.

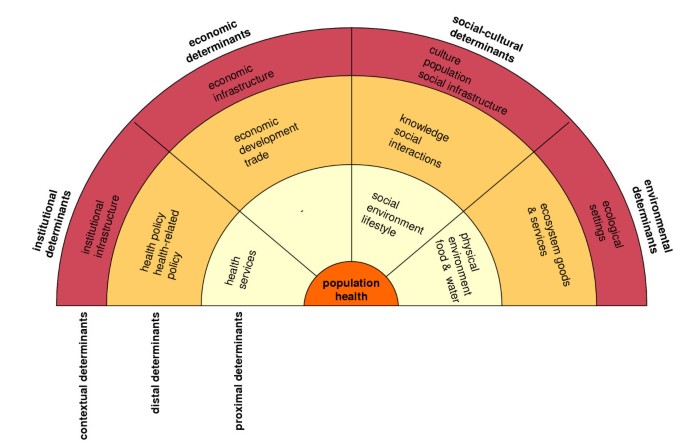

Our identification of the most important factors influencing health is primarily based on a comprehensive analysis of a diverse selection of existing health models (see Huynen et al [ 4 ] for more details). We argue that the nature of the determinants and their level of causality can be combined into a basic framework that conceptualises the complex multi-causality of population health. In order to differentiate between health determinants of different nature, we will make the traditional distinction between social-cultural, economic, environmental and institutional factors. These factors operate at different hierarchical levels of causality, because they have different positions in the causal chain. The chain of events leading to a certain health outcome includes both proximal and distal causes; proximal factors act directly to cause disease or health gains, and distal determinants are further back in the causal chain and act via (a number of) intermediary causes [ 5 ]. In addition, we also distinguish contextual determinants. These can be seen as the macro-level conditions shaping the distal and proximal health determinants; they form the context in which the distal and proximal factors operate and develop.

Subsequently, a further analysis of the selected health models and an intensive literature study resulted in a wide-ranging overview of the health determinants that can be fitted within this framework (Figure 1 and Table 1 ). We must keep in mind, however, that determinants within and between different domains and levels interact along complex and dynamic pathways to 'produce' health at the population level. Additionally, health in itself can also influence its multi-level, multi-nature determinants; for example, ill health can have a negative impact on economic development.

Multi-nature and multi-level framework for population health.

Globalisation

There is more and more agreement on the fact that globalisation is an extremely complex phenomenon; it is the interactive co-evolution of multiple technological, cultural, economic, institutional, social and environmental trends at all conceivable spatiotemporal scales. Hence, Rennen and Martens [ 6 ] define contemporary globalisation as an intensification of cross-national cultural, economic, political, social and technological interactions that lead to the establishment of transnational structures and the global integration of cultural, economic, environmental, political and social processes on global, supranational, national, regional and local levels. Although somewhat complex, this definition is in line with the view on globalisation in terms of deterritorialisation and explicitly acknowledges the multiple dimensions involved.

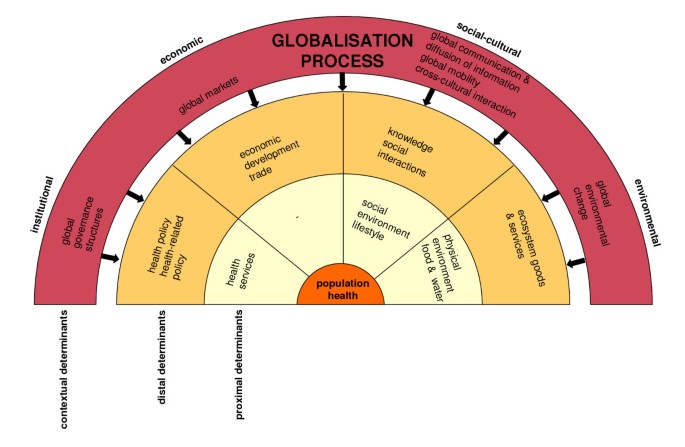

However, the identification of all possible health effects of the globalisation process goes far beyond the current capacity of our mental ability to capture the dynamics of our global system; due to our ignorance and interdeterminacy of the global system that may be out of reach forever [ 7 ]. In order to focus our conceptual framework, we distinguish-with the broader definition of globalisation in mind-the following important features of the globalisation process: (the need for) new global governance structures, global markets, global communication and diffusion of information, global mobility, cross-cultural interaction, and global environmental changes (Table 2 ) (see Huynen et al. [ 4 ] for more details).

Conceptual model for globalisation and health

We have identified (the need for) global governance structures, global markets, global communication and the diffusion of information, global mobility, cross-cultural interaction, and global environmental changes as important features of globalisation. Based on Figure 1 and Table 1 , it can be concluded that these features all operate at the contextual level of health determination and influence distal factors such as health(-related) policies, economic development, trade, social interactions, knowledge, and the provision of ecosystem goods and services. In turn, these changes in distal factors have the potential to affect the proximal health determinants and, consequently, health. Our conceptual framework for globalisation and health links the above-mentioned features of the globalisation process with the identified health determinants. This exercise results in Figure 2 .

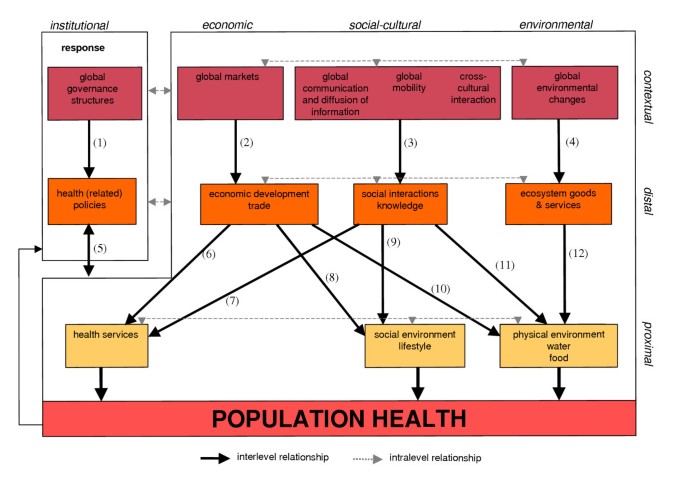

Conceptual framework for globalisation and population health.

Figure 3 , subsequently, shows that within the developed framework, several links between the specific features of globalisation and health can be derived. These important links between globalisation and health are discussed in the following sections. It is important to note that Figure 3 primarily focuses on the relationships in the direction from globalisation to health. This does not mean, however, that globalisation is an autonomous process: globalisation is influenced by many developments at the other levels, although these associations are not included in the Figure for reasons of simplification. In addition, the only feedback that is included in Figure 3 concerns the institutional response. One also has to keep in mind that determinants within the distal level and within the proximal level also interact with each other, adding complexity to our model (see Huynen et al. 4 for more details and examples of important intralevel relationships).

Conceptual model for globalisation and population health.

Globalisation and distal health determinants

Figure 3 shows that the processes of globalisation can have an impact on all identified distal determinants (Figure 3 ; arrows 1–4). Below, the implications of the globalisation process on these distal determinants will be discussed in more detail.

Health(-related) policies

Global governance structures are gaining more and more importance in formulating health(-related) policies (Figure 3 ; arrow 1). According to Dodgson et al. [ 8 ], the most important organisations in global health governance are the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Bank (WB). The latter plays an important role in the field of global health governance as it acknowledges the importance of good health for economic development and focuses on reaching the Millennium Development Goals [ 9 ]. The WB also influenced health(-related) policies together with the International Monetary Funds (IMF) through the Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) (e.g. see Hong [ 10 ]). In order to give a more central role to pro-poor growth considerations in providing assistance to low-income countries, the IMF and WB introduced the Poverty Reduction Strategy approach in 1999 [ 11 ]. In addition, the policies of the World Trade Organization (WTO) are also increasingly influencing population health [ 10 , 12 – 14 ]. Fidler [ 15 ] argues that 'from the international legal perspective, the centre of power for global health governance has shifted from WHO to the WTO'. Opinions differ with regard to whether the WTO agreements provide sufficient possibilities to protect the population from the adverse (health) effects of free trade or not [ 16 ]. In 2002, the WTO ruled that the French ban on the import of all products containing asbestos was legal on health grounds, despite protests from Canada [ 17 , 18 ]. However, protecting citizens against health risks remains difficult, as health standards often need to be supported by sound scientific evidence before trade can be restricted (see e.g. the WTO ruling against the European trade barrier concerning hormone-treated meat [ 19 , 20 ]).

Another important development is the growing number of public-private partnerships for health, as governments increasingly attract private sector companies to undertake tasks that were formerly the responsibility of the public sector. At the global level, public-private partnerships are more and more perceived as a possible new form of global governance [ 12 ] and could have important implications for health polices, but also for health-related policies.

Economic development

Opinions differ with regard to the economic benefits of economic globalisation (Figure 3 ; arrow 2). On the one side, 'optimists' argue that global markets facilitate economic growth and economic security, which would benefit health. They base themselves on the results of several studies that argue that inequities between and within countries have decreased due to globalisation (e.g. see Frankel [ 21 ], Ben David [ 22 ], Dollar and Kraay [ 23 ]). Additionally, it is argued that although other nations or households might become richer, absolute poverty is reduced and that this is beneficial for the health of the poor [ 24 ]. On the other side, 'pessimists' are worried about the health effects of the exclusion of nations and persons from the global market. They argue that the risk of exclusion from the growth dynamics of economic globalisation is significant in the developing world [ 25 ]. In fact, notwithstanding some spectacular growth rates in the 1980's, especially in east Asia, incomes per capita declined in almost 70 countries during the same period [ 26 ]. Many worry about what will happen to the countries that cannot participate in the global market as successful as others.

Due to the establishment of global markets and a global trading system, there has been a continuing increase in world trade (Figure 3 ; arrow 2). According to the WTO, total trade multiplied by a factor 14 between 1950 and 1997 [ 27 ]. Today all countries trade internationally and they trade significant proportions of their national income; around 20 percent of world output is being traded. The array of products being traded is wide-ranging; from primary commodities to manufactured goods. Besides goods, services are increasingly being traded as well [ 28 ]. In addition to legal trade transactions, illegal drug trade is also globalising, as it circumvents national and international authority and takes advantage of the global finance systems, new information technologies and transportation.

Social interactions: migration

Due to the changes in the infrastructures of transportation and communication, human migration has increased at unprecedented rates (Figure 3 ; arrow 3) [ 28 ]. According to Held et al. [ 28 ] tourism is one of the most obvious forms of cultural globalisation and it illustrates the increasing time-space compression of current societies. However, travel for business and pleasure constitutes only a fraction of total human movement. Other examples of people migrating are missionaries, merchant marines, students, pilgrims, militaries, migrant workers and Peace Corps workers [ 28 , 29 ]. Besides these forms of voluntary migration, resettlement by refugees is also an important issue. However, since the late 1970s, the concerns regarding the economic, political, social and environmental consequences of migration has been growing and many governments are moving towards more restrictive immigration policies [ 30 ].

Social interactions: conflicts

The tragic terrorist attacks in New York and Washington D.C. in September 2001 fuelled the already ongoing discussions on the link between globalisation and conflicts. Globalisation can decrease the risk on tensions and conflicts, as societies become more and more dependent on each other due the worldwide increase in global communication, global mobility and cross-cultural interactions (Figure 3 ; arrow 3). Others argue that the resistance to globalisation has resulted in religious fundamentalism and to worldwide tensions and intolerance [ 31 ]. In addition, the intralevel relationships at the distal level play a very important role, because many developments in other distal factors that have been associated with the globalisation process are also believed to increase the risk on conflicts. In other words, the globalisation-induced risk on conflict is often mediated by changes in other factors at the distal level [ 4 ].

Social interactions: social equity and social networks

Cultural globalisation (global communication, global mobility, cross-cultural interaction) can also influence cultural norms and values about social solidarity and social equity (Figure 3 ; arrow 3). It is feared that the self-interested individualism of the marketplace spills over into cultural norms and values resulting in increasing social exclusion and social inequity. Exclusion involves disintegration from common cultural processes, lack of participation in social activities, alienation from decision-making and civic participation and barriers to employment and material sources [ 32 ]. Alternatively, a socially integrated individual has many social connections, in the form of both intimate social contacts as well as more distal connections [ 33 ]. On the other hand, however, the geographical scale of social networks is increasing due to global communications and global media. The women's movement, the peace movement, organized religion and the environmental movement are good examples of such transnational social networks. Besides these more formal networks, informal social networks are also gaining importance, as like-minded people are now able to interact at distance through, for example, the Internet. In addition, the global diffusion of radio and television plays an important role in establishing such global networks [ 28 ]. The digital divide between poor and rich, however, can result in social exclusion from the global civil society.

The knowledge capital within a population is increasingly affected by developments in global communication and global mobility (Figure 3 : arrow 3). The term 'globalisation of education' suggests getting education into every nook and cranny of the globe. Millions of people now acquire part of their knowledge from transworld textbooks, due to the supraterritoriality in publishing. Because of new technologies, most colleges and universities are able to work together with academics from different countries, students have ample opportunities to study abroad and 'virtual campuses' have been developed. The diffusion of new technologies has enabled researchers to gather and process data in no time resulting in increased amounts of empirical data [ 34 ]. New technologies have even broadened the character of literacy. Scholte [ 34 ] argues that 'in many line of work the ability to use computer applications has become as important as the ability to read and write with pen and paper. In addition, television, film and computer graphics have greatly enlarged the visual dimensions of communication. Many people today 'read' the globalised world without a book'. Overall, it is expected that the above-discussed developments will also improve health training and health education (e.g. see Feachem [ 24 ] and Lee [ 35 ]).

Ecosystem goods and services

Global environmental changes can have profound effects on the provision of ecosystem goods and services to mankind (Figure 3 ; arrow 4). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [ 36 ] concludes that it is expected that climate change can result in significant ecosystem disruptions and threatens substantial damage to the earth's natural systems. In addition, several authors have addressed the link between biodiversity and ecosystem functioning and it is agued that maintaining a certain level of biodiversity is necessary for the proper provision of ecosystem goods and services [ 37 – 40 ]. However, it is still unclear which ecosystem functions are primarily important to sustain our physical health. Basically, the following types of 'health functions' can be distinguished. First, ecosystems provide us with basic human needs like food, clean air, clean water and clean soils. Second, they prevent the spread of diseases through biological control. Finally, ecosystems provide us with medical and genetic resources, which are necessary to prevent or cure diseases [ 41 ].

Globalisation and proximal health determinants

Figure 3 shows that the impact of globalisation on each proximal health determinant is mediated by changes in several distal factors (Figure 3 ; arrows 5–12). The most important relationships will be discussed in more detail below. It is important to note that health policies and health-related policies can have an influence on all proximal factors (Figure 3 ; arrow 5).

Health services

Health services are increasingly influenced by globalisation-induced changes in health care policy (Figure 3 ; arrow 5), economic development and trade (Figure 3 : arrow 6), and knowledge (Figure 3 ; arrow 7), but also by migration (3: arrow 7). Although the WHO aims to assist governments to strengthen health services, government involvement in health care policies has been decreasing and, subsequently, medical institutions are more and more confronted with the neoliberal economic model. Health is increasingly perceived as a private good leaving the law of the market to determine whose health is profitable for investment and whose health is not [ 10 ]. According to Collins [ 42 ] populations of transitional economies are no longer protected by a centralized health sector that provides universal access to everyone and some groups are even denied the most basic medical services. The U.S. and several Latin American countries have witnessed a decline in the accessibility of health care following the privatisation of health services [ 43 ].

The increasing trade in health services can have profound implications for provision of proper health care. Although it is perceived as to improve the consumer's choice, some developments are believed to have long-term dangers, such as establishing a two-tier health system, movement of health professionals from the public sector to the private sector, inequitable access to health care and the undermining of national health systems [ 10 , 12 ]. The illegal trading of drugs and the provision of access to controlled drugs via the Internet are potential health risks [ 44 ]. In addition, the globalisation process can also result in a 'brain-drain' in the health sector as a result of labour migration from developing to developed regions.

However, increased economic growth is generally believed to enhance improvements in health care. Increased (technological) knowledge resulting from the diffusion of information can further improve the treatment and prevention of all kinds of illnesses and diseases.

Social environment

The central mechanism that links personal affiliations to health is 'social support,' the transfer from one person to another of instrumental, emotional and informational assistance [ 45 ]. Social networks and social integration are closely related to social support [ 46 ] and, as a result, globalisation-induced changes in social cohesion, integration and interaction can influence the degree of social support in a population (Figure 3 ; arrow 9). This link is, for example, demonstrated by Reeves [ 47 ], who discussed that social interactions through the Internet influenced the coping ability of HIV-positive individuals through promoting empowerment, augmenting social support and facilitating helping others. Alternatively, social exclusion is negatively associated with social support.

Another important factor in the social environment is violence, which often is the result of the complex interplay of many factors (Figure 3 ; arrows 5, 8 and 9). The WHO [ 48 ] argues that globalisation gives rise to obstacles as well as benefits for violence prevention. It induces changes in protective factors like social cohesion and solidarity, knowledge and education levels, and global violence prevention activities such as the implementation of international law and treaties designed to reduce violence (e.g. social protection). On the other hand, it also influences important risk factors associated with violence such as social exclusion, income inequality, collective conflict, and trade in alcohol, drugs or firearms.

Due to the widespread flow of people, information and ideas, lifestyles also spread throughout the world. It is already widely acknowledged and demonstrated that several modern behavioural factors such as an unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol misuse and the use of illicit drugs are having a profound impact on human health [ 49 – 52 ] (Table 3 ). Individuals respond to the range of healthy as well as unhealthy lifestyle options and choices available in a community [ 53 ], which are in turn determined by global trade (Figure 3 ; arrow 8), economic development (Figure 3 ; arrow 8) and social interactions (Figure 3 ; arrow 9).