- Air Transport

- Defense and Space

- Business Aviation

- Aircraft & Propulsion

- Connected Aerospace

- Emerging Technologies

- Manufacturing & Supply Chain

- Advanced Air Mobility

- Commercial Space

- Sustainability

- Interiors & Connectivity

- Airports & Networks

- Airlines & Lessors

- Safety, Ops & Regulation

- Maintenance & Training

- Supply Chain

- Workforce & Training

- Sensors & Electronic Warfare

- Missile Defense & Weapons

- Budget, Policy & Operations

- Airports, FBOs & Suppliers

- Flight Deck

- Marketplace

- Advertising

- Marketing Services

- Fleet, Data & APIs

- Research & Consulting

- Network and Route Planning

Market Sector

- AWIN - Premium

- AWIN - Aerospace and Defense

- AWIN - Business Aviation

- AWIN - Commercial Aviation

- Advanced Air Mobility Report - NEW!

- Aerospace Daily & Defense Report

- Aviation Daily

- The Weekly of Business Aviation

- Air Charter Guide

- Aviation Week Marketplace

- Route Exchange

- The Engine Yearbook

- Aircraft Bluebook

- Airportdata.com

- Airport Strategy and Marketing (ASM)

- CAPA – Centre for Aviation

- Fleet Discovery Civil

- Fleet Discovery Military

- Fleet & MRO Forecast

- MRO Prospector

- Air Transport World

- Aviation Week & Space Technology

- Aviation Week & Space Technology - Inside MRO

- Business & Commercial Aviation

- CAPA - Airline Leader

- Routes magazine

- Downloadable Reports

- Recent webinars

- MRO Americas

- MRO Australasia

- MRO Baltics & Eastern Europe Region

- MRO Latin America

- MRO Middle East

- Military Aviation Logistics and Maintenance Symposium (MALMS)

- Asia Aerospace Leadership Forum & MRO Asia-Pacific Awards

- A&D Mergers and Acquisitions

- A&D Programs

- A&D Manufacturing

- A&D Raw Materials

- A&D SupplyChain

- A&D SupplyChain Europe

- Aero-Engines Americas

- Aero-Engines Europe

- Aero-Engines Asia-Pacific

- Digital Transformation Summit

- Engine Leasing Trading & Finance Europe

- Engine Leasing, Trading & Finance Americas

- Routes Americas

- Routes Europe

- Routes World

- CAPA Airline Leader Summit - Airlines in Transition

- CAPA Airline Leader Summit - Americas

- CAPA Airline Leader Summit - Latin America & Caribbean

- CAPA Airline Leader Summit - Australia Pacific

- CAPA Airline Leader Summit - Asia & Sustainability Awards

- CAPA Airline Leader Summit - World & Awards for Excellence

- GAD Americas

- A&D Mergers and Acquisitions Conference (ADMA)

- A&D Manufacturing Conference

- Aerospace Raw Materials & Manufacturers Supply Chain Conference (RMC)

- Aviation Week 20 Twenties

- Aviation Week Laureate Awards

- ATW Airline Awards

- Program Excellence Awards and Banquet

- CAPA Asia Aviation Summit & Awards for Excellence

- Content and Data Team

- Aviation Week & Space Technology 100-Year

- Subscriber Services

- Advertising, Marketing Services & List Rentals

- Content Sales

- PR & Communications

- Content Licensing and Reprints

- AWIN Access

What Went Wrong With The Airbus A380?

The last Airbus A380 ever produced is slated to be handed over to Emirates imminently. The delivery will close one of the most spectacular chapters in European aerospace history.

It was spectacular in many ways: The A380 was the largest commercial aircraft ever produced, intended to eclipse Boeing ’s 747; passengers and pilots loved its comfort and ease of flying, even if airline finance departments were less enamored with it. The aircraft’s production run, spanning just 14 years, was drama-filled, including the expensive redesign of its wings and increasingly desperate campaigns to sell more of the giant aircraft and extend its life. They were full of negotiations about even larger versions and Neos, after the reengining concept had worked so well for the A320 family.

But after Emirates finally pulled the plug on a large follow-up order that would have saved the program in the winter of 2018, it was up to departing Airbus CEO Tom Enders to finally decide the ending for the A380. It had become clear that Airbus would never recover the €25 billon ($30 billion) or so in research and development costs sunk into the program over the years. And with no new orders keeping production open even at minimal rates, it became unsustainable. Europe’s most ambitious commercial aircraft program post-Concorde had become a gigantic failure and a prime example of management reading the market improperly.

Was it a misreading, though? Was there ever a chance of it continuing until demand recovery?

In the weeks before that final delivery, Aviation Week ShowNews spoke with many insiders who shared their views and memories. Among them were Enders and former Airbus sales chief John Leahy as well as Nico Buchholz, himself a former Airbus sales executive who later ordered the aircraft for Lufthansa as its head of fleet strategy. Some still think the program could have been rescued. But the look back into its history also shows that industry doubts about the A380’s viability had begun even before first delivery.

Paradigm Shift

Enders was head of strategy at Airbus’ German shareholder DASA in the 1990s—the manufacturer was still a loose economic interest group (French acronym GIE), a consortium of shareholders that was nowhere near being integrated. Much later, of course, the A380 was the key factor in fundamentally changing that. In the 1990s, discussions about the risks and opportunities of building an A3XX were intensifying after years of studies. “Airbus did not stumble into [building] the A380; we were very aware of the project’s risks,” Enders says. “But then, technology and the market changed faster than everyone had thought.”

In hindsight, the writing may have been on the wall for the A380 even before its own entry into service—even as early as four years before. In December 2003, Boeing decided to launch the 787, a revolutionary aircraft in many ways, particularly in its use of lightweight composites for structural weight savings. By contrast, “Airbus’ achievement in the A380 was mainly to be able to build something that big,” says Buchholz. Other than that, the A380 was structurally fairly conventional.

Of equal importance was engine manufacturers’ commitment to build powerplants for the Boeing 787 that were significantly better than those of the A380.

The consequences were fundamental: Suddenly, the paradigm of building larger aircraft to cut unit costs was broken. The unit costs of 787—and later the A350—were comparable to or even better than those of the much larger A380, but with a considerably lower risk of not being able to fill the aircraft. Unit revenues were the other side of the coin: There was greater pressure on yields, with literally hundreds of additional seats to fill on every flight. Once Lufthansa started flying the A380 across the Atlantic, the airline found that the yield on its Frankfurt-New York route fell by almost as much as unit costs.

Looking back, Leahy has harsh words for Rolls-Royce and GE Aviation. “Airbus was blindsided by the engine manufacturers in 2000, when we were getting ready to launch it,” he says. “Our program people had assurances [from] the engine OEMs that there was nothing on the horizon with better specific fuel consumption [SFC] for years to come. And three years later, when we had not even delivered the first aircraft, GE and Rolls had engines with 15% better SFCs that they were bringing out for the 787. That left Airbus at a commercial disadvantage that was very unfortunate.”

The aircraft’s most important customer, Emirates Airline President Tim Clark, agrees to an extent. “I regret that it was not reengined, that the weight was not taken out,” he says. However, he also points to the many problems the A350and the 787 have had since the market introductions of the next generation of engines, issues the A380 has not faced to the same degree. He asks whether the A380 may have had the same reliability issues, which are hard enough to handle on a 150-seat narrowbody but could require large sums for passenger compensation and handling for just one canceled A380 flight. The tradeoff between efficiency and reliability was a big consideration.

When Airbus decided to launch the A380, it was still chasing another idea, and therefore the wrong target. “In the 1990s, not only Airbus but also many airlines were still very focused on four engines when it came to widebodies,” Enders recalls. And Airbus thought it had to build an aircraft that would compete with the 747 and break into the Boeing monopoly on very large jets. In 2015, in the midst of increasingly desperate struggles to find new customers, then-CEO Fabrice Bregier conceded that the A380 had been launched “at least 10 years too soon.”

Perhaps it was not launched too soon but too late: In 1990, Boeing received orders for 122 747-400s and delivered 70. Ten years later, when Airbuscommitted to building the A380, 747 orders were down to 26 and deliveries to 25. And with few exceptions since, 747 production has continuously declined.

Airbus’ growing problem was not just the 787, or later its own A350, which further deepened the market shift. In April 2004, it was none other than Air France, in Airbus’ backyard, that took delivery of the first two Boeing 777-300ERs. That aircraft, and not the A380, replaced the 747 as the reference on long-haul trunk routes before slowly being superseded by even more efficient twins.

“We all have misjudged the future of the twins, and that led to the efficiency problem of the A380,” Enders says. “I only admit this reluctantly, but Boeinghas largely been right with its point-to-point argument.” He is referencing the idea that passengers, when having the choice, prefer nonstop flights over hub connections. Both Leahy and Clark disagree with the idea that the hub concept has weakened. “I don’t share the view that the days of the superhub are over at all,” Clark says.

Missed Opportunities

The two-year phase from 2005 to 2007 was crucial to the A380’s early demise, not only because of the growing threat from more efficient twins. In those years, billions of euros in extra costs were added to the program, and important decisions that could have been made were not.

The aircraft had performed its first flight at the end of April 2005, a milestone for the entire aviation industry. Airbus garnered applause from around the world for the achievement. But a little over a month later, the company was forced to announce the first (six-month) delay in the program. As it turned out, different parts of the consortium had used different versions of the CATIA design software and, infamously, as a result many of the cables inside the fuselage were too short.

An almost incomprehensible struggle followed. Airbus threw literally thousands of technicians and engineers at the problem. Many in charge burned out—and many left, but those who stayed learned tough lessons that were incredibly valuable for their later careers. Airbus had to announce two more delays before finally regaining control of the situation toward the end of 2006.

The crisis was so deep that management considered the most radical moves. “We asked ourselves whether we should terminate the program,” Enders reveals. “But that would not have been right back then. Development was very far advanced, and the reputational damage would have been huge.”

There were still consequences. EADS had been formed in 2000 along with the launch of the A380. The former Airbus GIE was converted into a real company a year later. But in 2006, EADS acquired the remaining 20% in Airbus SAS previously held by BAE Systems and proceeded with much deeper integration. “We pushed through relatively brutal integration in 2006-07,” Enders says. “Before that there had been a lot of talk about it but no real action.”

Airlines had their own perspective, which changed substantially between the 2000 launch and entry into service seven years later. “In 2000, you could not predict what crystallized in 2005—that the aircraft was technically outdated,” says Buchholz, who ordered the A380s for Lufthansa. After all, the aircraft’s unit costs were advertised to be 13% better than those of the 747-400. But then things started to move.

Japan opened up Tokyo Haneda Airport for international flights, weakening the argument that the A380 was needed for slot-constrained Narita International Airport. China built new international airports at a record pace and encouraged long-haul service to them. “You could get a feeling that the A380 was going to be too large,” remembers Buchholz. “But you could not really prove it.”

Buchholz contends that it might have been possible to rescue the A380, but it would have required early, decisive and painful action. When the program was delayed bya cabin installation disaster, Airbus should have used the opportunity to modernize the aircraft with a better engine based on ongoing development programs for the 787 and later the A350. “With a better engine, the A380 would have had a longer life,” he says.

“With new engines, it would have been an unbeatable aircraft in the marketplace,” Leahy asserts. “We came close to pulling it off. Had we had the right engines, we would probably have rewritten history.”

But he does not think Buchholz’s idea of pushing for an early reengining then would have been possible. “There were commitments made; the engines were being developed. It would have pushed back the thing a couple of years, [and] there would have been big fights with the engine manufacturers. They had invested a lot of money into that generation of engines.”

On Oct. 15, 2007, Airbus finally delivered the first A380 to Singapore Airlines. A little over a week later, the aircraft flew its first commercial service from Singapore to Sydney. It was a major milestone that, Airbus hoped, would pave the way for a less eventful future and a ramp-up of production to 45 aircraft a year, a rate of just under four aircraft per month. Of course, Airbus never reached rate 45. Production peaked at 30 aircraft in both 2012 and 2014. The last relatively big year for the type was 2016, when Airbus again managed to deliver 28. However, the turning point that likely sealed the aircraft’s fate also occurred in 2016 and led to the end of production five years later.

Weighty Issues

The nine years between 2007 and 2016 continued to be drama-filled. Emirates, by far the type’s most important and loyal operator, had just taken delivery of its first aircraft in early 2008 when the U.S. subprime and global financial crisis unfolded and heavily affected demand for international air travel. Airbus delivered 12 A380s in 2008 and only 10 a year later, a step in the wrong direction. It was not able to expand production in a significant manner until 2010, when it decided to shelve plans for the A380-900 in light of the huge financial burdens accumulated and development work on the A350, A320neoand A400M.

The stretched A380 version was what the Airbus designers really had in mind when they built a wing much larger than necessary for the baseline A380-800. It made that version heavier and so significantly less efficient than would have been possible with a smaller wing optimized for its fuselage size. “The [A380-800] was not the aircraft that we actually wanted to build,” Enders says.

“The design was optimized for larger variants,” Buchholz says. Airlines knew that, of course. But some, like Lufthansa, decided right from the beginning that the -900 would have been too large. The problem with the -800—“you can’t send the upper deck somewhere else when a route does not perform as planned,” as Bucholz puts it—would only have become worse with a larger aircraft, he says. The lack of flexibility was frightening airline planners.

On the other hand, Emirates was foremost of a number of airlines that were very much in favor of the -900. They pointed out that the larger version would be much more efficient and could reinstate the unit-cost advantage over smaller long-haul aircraft, including the A350 and 787. They also saw a market for it on their busiest routes. “We wanted the -900, not the -800,” Clark says. “The aircraft would have had another 120 seats. But when the idea was discussed, there was a slowing down in appetite [at other airlines]. We did not share [their] view.”

The real problem with the A380-900 plan was not that the stretch was never built, it was that it made the -800 a much worse version. “The fact that from the very beginning they built weight into the airplane so they could do the -900 was a program mistake,” Leahy points out. “You just don’t build extra weight into the airplane so you can stretch it. You optimize the aircraft, and then you figure out how to stretch it by taking some of the margin that you did not need. When you build in the capacity for another 100 seats from Day 1, you are going to build a heavy airplane.”

Clark says it still worked well for Emirates. “In the years after the financial crisis, 80% of our profits came from the A380,” he notes. “The A380 is still a hugely efficient aircraft, even though it has old-technology engines.” According to his calculations, a two-class A380 has 4% lower fuel burn per seat than a 787-9 at equivalent space allocation, which would mean putting 670 seats onto the aircraft. Emirates’ two-class A380s currently have 617 seats.

The airline went above and beyond anyone else in the industry to make the aircraft the core of its brand. “It was a wonderful, exciting challenge to deal with this enormous amount of space,” Clark remembers somewhat wistfully. “We put in the bars and the showers. We created a Ritz Carlton.”

But that Ritz Carlton was hugely complex to build. “The showers caused a lot of issues,” Clark says. Pumping hot water up to the upper deck with sufficient pressure was just one of them.

‘ A Brick Wall’

One of the biggest misunderstandings in the history of the A380 was its true market potential in China. “If small Dubai can take more than 100 aircraft, we should be able to place a lot more of them into China,” a senior Airbusexecutive recalls thinking. But in the entire production run of the aircraft, only five were actually delivered to a Chinese airline, China Southern, the first of which arrived in October 2011. So why did China not work out?

When Airbus tried to sell the A380 to the nation’s big three—Air China, China Eastern and China Southern—some factors worked against them. Given their relatively poor reputation for customer service and product quality, the carriers lacked confidence that they could compete with their U.S. and European rivals on long-haul routes, let alone with an aircraft that big.

Long-haul flying was also a much smaller part of their business at the time, as opposed to the late 2010s. Being very conservative, the Chinese airlines also disliked launching a new aircraft, or even taking delivery of one, until performance was proven well after market introduction. The odds for Chinese business were always much lower than some in Toulouse had imagined.

“The obvious target [for A380s] should have been Air China,” says one insider. Of the three airlines, it was the one with a base in the country’s capital, and in many ways it was perceived as the flag carrier. But, unfortunately, the airline always had been close to Boeing and ended up being one of the few carriers around the world that ordered the 747-8.

For Leahy, the case is clear. “There was an enormous amount of politics involved in this from the U.S. and Boeing ,” he says. “There was a lot of pressure on Beijing to not go with the airplane and stay with the 747. There was a lot of ingrained inertia with the old team in Beijing. That’s where we hit a brick wall.”

Some China experts believe it was still possible at some stage to have placed the A380 with Air China. “If Cathay Pacific had gone for the A380, Air Chinawould have followed,” says a source with knowledge of past talks.“ Cathay certainly would have helped,” Leahy agrees.

Although the carrier’s former CEO Tony Tyler has always been skeptical about the aircraft, Cathay was nonetheless close to an order at various points, particularly in 2010. One time, according to an insider, a deal failed only because Toulouse was not willing to accept some last-minute concessions demanded by the airline.The Hong Kong-based carrier was perceived as a role model for strategy, fleet and product quality by Air China, which has since also become a big shareholder. But Cathay did not jump.

The only order for the A380 ever placed by a Chinese carrier also played a role, notes one executive. “You could argue that selling to China Southern was a mistake,” he says. “It really enraged Air China, because they viewed themselves as the flag carrier. There was also a lot of personal rivalry between the CEOs, and when China Southern went for [the A380], Air China had to show it was the wrong move.”

A fleet of just five aircraft was also suboptimal and a compromise that did not work, particularly from China Southern’s main base in Guangzhou. The airline always planned to base the aircraft at Beijing but was not allowed to deploy them on routes from Air China’s hub. The two carriers tried to negotiate a joint A380 operation but in the end could not come to an agreement.

At one point, Hong Kong Airlines placed an order for 10 A380s, but insiders say the commitment was “never very credible.”

Had Airbus succeeded in breaking into the Chinese market, would it really have been literally with hundreds of aircraft, as some hoped? One executive with deep knowledge of the situation says Air China could have taken no more than 15 A380s and China Eastern and China Southern possibly 10 each. Even if the Hong Kong Airlines deal had gone through, only about 50 aircraft across all Chinese and Hong Kong-based airlines seemed feasible, the executive says. “Two-hundred was never going to be realistic,” he asserts.

In the meantime, the A380 went through its first safety and second industrial crisis. On Nov. 4, 2010, Qantas Flight 32 (QF32), an A380 registered VH-OQA, took off from Singapore Changi Airport bound for Sydney, just like the type’s first commercial flight three years earlier. But this time, the flight did not go smoothly. VH-OQA suffered an uncontained failure of engine No. 2, a Rolls-Royce Trent 900, 4 min. after takeoff, causing extensive damage to the airframe, wings, tanks and one hydraulic system. Two other engines continued to operate, but only in degraded mode.

QF32 landed back in Singapore and no one was hurt, but both Qantas and Singapore Airlines temporarily grounded their A380 fleets. According to a 2011 preliminary report by the Australian Transport Safety Board, 55 Trent 900 engines had to be replaced across the world fleet.

As dramatic as the incident was, the type’s most serious since commercial service had begun also demonstrated the resilency of the aircraft—and the flight’s crew. Redundancy had paid off.

VH-OQA was repaired in Singapore and returned to Australia in April 2012. During the repairs, tiny cracks in the wings were discovered. They turned out to be the start of the next industrial crisis: Airbus had to strengthen certain areas of the wings for in-service aircraft and use a new aluminum alloy for some parts going forward. The problem was eventually fixed, and it is not among the main causes of the premature end of production. But it made the program’s economics even worse. It was becoming increasingly clear that Airbus would never make a profit on the A380.

The Last Stand

But the airframer was still a long way from giving up. About a year after the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) had made mandatory checks for wing cracks, Airbus delivered the 100th A380 to Malaysia Airlines. With the industry now fully out of the global financial crisis, the air transport sector entered an unprecedented period of strong growth, helped by expanding global trade, low interest rates and—for the most part--—relatively low fuel prices. Those in charge in Toulouse were still hopeful the A380 could benefit and somehow turn the corner.

In November 2013, Emirates gave the program another boost: With 39 of the aircraft in service and another 51 on firm order, the airline bought 50 more at the Dubai Airshow. The three big Gulf carriers were peaking—they also placed massive commitments for the new Boeing 777X at the time. The Emirates deal was for the existing aircraft, but the A380neo concept was also discussed. After all, Airbus had launched the A320neo in 2010 and had received much better market feedback than expected.

A year after that Dubai Airshow, Airbus’ then-CEO Fabrice Bregier said the company would “one day” launch an A380neo and a stretch—and the bigger aircraft would get new engines. Six months later, he talked about an A380neo that would enter service around 2020. But in June 2016, Clark announced that the talks about an A380neo had “lapsed.”

“It was becoming apparent that we weren’t getting a customer on board for a Neo or a stretch,” Leahy says. “They were looking at some strong commitments from the engine manufacturers, as well as Airbus, about what the capability was going to be of a reengined airplane.”

Potential customers did not get what they wanted. Only one month later, in July 2016, Airbus made a U-turn by announcing a massive production cut from 28 aircraft that year to just 12 in 2018. The company was trying to buy time, as well as looking for alternatives.

In June 2017, Airbus presented the A380plus concept—the same airframe as before but with a more efficient cabin, around 80 more seats. Space was going to be made available, among other ways, by eliminating the rear staircase that was taking up a lot of room. But, again, customer response was lukewarm. Notably, Emirates did not like the idea since the A380’s luxury—the first-class shower and the bar at the back of the upper deck—had become part of its iconic brand.

Emirates stuck with the aircraft nonetheless. With the A380 deep in crisis mode and questions about its viability (and residual value) swirling, the airline agreed to buy another 36 aircraft at the beginning of 2018. The decision was preceded by months of tense negotiations with both Airbus and Rolls-Royce. The Engine Alliance of General Electric and Pratt & Whitney had long lost interest in further A380 business.

The deal, Airbus hoped, would enable it to sustain production at low but justifiable levels long enough for demand from other airlines to kick in eventually. It was also Leahy’s last marquee deal, a final exclamation point at the end of a very successful decades-spanning career as an aircraft salesman. Almost exactly one year after Leahy returned from the contract talks in Dubai, though, Enders pulled the plug on the project, announcing that production would cease in 2022, a date that would later be pulled forward to November 2021.

When Enders decided to end the program, Leahy had already retired, and the CEO had also announced his own departure. “Tom was leaving the company. He felt the A380 was not selling well, and he wanted to clear the deck for the new team and shut down the program,” the former sales chief says. “That is just the way Tom is.”

Leahy saw things differently. “I fully expected the A380 program to continue with Emirates’ support after I retired,” he says. “I left around February, handed over to a new commercial director and expected to have that deal finalized.”

So why didn’t that happen? “I never really managed to get to the bottom of why they were not able to do it,” he says. “I think it was a combination of Airbus and Rolls-Royce factors. Emirates still wanted to do the deal. I still believe it to this day.”

The case may be more nuanced. Clark remembers that Emirates was going through another round of fleet strategy planning in late 2018 and was coming to the conclusion that a fleet of 120 A380s was going to be “optimal.” At least a large part of that fleet is to be flown “well into the 2030s,” Clark notes.

However, in the end, even Emirates found that it did not want more of the aircraft and instead decided that a supplemental fleet of smaller A350s and 787-9s made more sense.

Based in Frankfurt, Germany, Jens is executive editor and leads Aviation Week Network’s global team of journalists covering commercial aviation.

Related Content

Brought to you by:

The Rise and Demise of Airbus A380

By: Xuesong Geng, Lipika Bhattacharya

Set in July 2021, this case talks about the launch and discontinuation of the very large aircraft, A380, by leading aircraft manufacturer Airbus. The development of the A380 had been motivated by two…

- Length: 24 page(s)

- Publication Date: Oct 4, 2021

- Discipline: Strategy

- Product #: SMU990-PDF-ENG

What's included:

- Teaching Note

- Educator Copy

$4.95 per student

degree granting course

$8.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

Set in July 2021, this case talks about the launch and discontinuation of the very large aircraft, A380, by leading aircraft manufacturer Airbus. The development of the A380 had been motivated by two key factors - the projected market trend of increased hub-and-spoke travel and the success of Boeing 747 - a very large aircraft by Boeing. Although the A380 was the biggest passenger aircraft ever built, with avant-garde technology and reconfigurable design, it failed to succeed due to changing industry trends. Hub airports were witnessing increasing traffic congestion, and more and more airlines were switching to point-to-point travel to avoid hubs altogether. Demand for very large aircrafts like the A380 fell by almost 92% from 2010 to 2020, and Airbus had to make the harsh decision of shutting down the aircraft's production in 2021. The case describes the high stake decision behind the development of the A380 and how it fared after its launch. It also elaborates the duopoly between Boeing and Airbus, which accounted for 91% of the commercial aircraft market share. The case ends with forward-looking questions on what strategies Airbus can implement after the demise of the A380 to compete with long-standing rival Boeing and new entrants like Chinese aircraft manufacturers in a cut-throat market that was witnessing the commencement of environmentally friendly aircraft projects by the two leading players as the new battlefield.

Learning Objectives

Although one might intuitively blame the low demand for A380 on the changing market environment and the shift from hub-and-spoke to point-to-point model, the analysis in this teaching note shows that it is also partly due to the deliberate strategic moves made by Boeing after the launch of the A380. By providing rich information on Airbus and Boeing's product portfolio, market information, and financial information of A380, this case allows instructors to teach topics such as strategic management, strategic change, and competitive strategies.

Oct 4, 2021 (Revised: Oct 10, 2021)

Discipline:

Geographies:

Industries:

Aerospace sector

Singapore Management University

SMU990-PDF-ENG

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- Backchannel

- Newsletters

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Will Bedingfield

Why did the Airbus A380 fail?

The rapid demise of the Airbus A380 is a complex tale of missed connections, a changing market and, ultimately, a staggering lack of demand for the largest commercial airplane ever built. And, as a result, this giant of the skies could well be the last of its kind.

The decision to stop production on the A380 came after Emirates, which operates more than half of all flights using the plane, halved its latest order. After being in production for a little over 12 years, the A380 will go down as one of the shortest-lived models in aviation history. But why did it fail?

To understand that, you first need to understand how Airbus hoped it would succeed. The thought process behind the aircraft’s design – specifically, its size – had two major threads. The first, argues John Grant, director of JG Aviation Consultants, was “a strategic desire to distance themselves from being just another Boeing.” (Boeing had released a smaller aircraft, the 787 Dreamliner, at the same time back in 2007). To an extent, that worked. So far so good.

The second problem was a gamble on the future of the market. “It was designed to solve an expected problem”, says Keith Mason, Professor of Air Transport Management at Cranfield University, who assessed Boeing and Airbus’s differences in philosophy back in 2007. Airbus’s logic here was simple: if the industry continued to grow at the expected rate – Mason says passenger numbers typically double every 15 years – then airports would be overwhelmed by the sheer number of people. A large plane, so the argument went, would help ease this bottleneck by picking up more people per flight while also maximising value for pricey landing slots. This prediction proved to be wrong. “Airport congestion hasn’t happened,” says Mason. In fact, airport capacity in many markets, especially Asia, has grown.

The A380’s failure is also a result of a switch in the aviation world towards smaller, more efficient aircraft. Boeing’s B787, for example, seats around half as many passengers as the A380. In fact, Emirates, as it cut back on the A380, placed a large order of Airbus’s own saller A350 and A330. Grant points out that these aircraft offer “better operating economics, lower costs, smaller capacity and therefore less pressure to fill every seat”.

The sheer size and luxury of the A380 also played a role in its undoing. The plane, which is estimated to have cost $25bn (£19.4bn) to develop, runs on a capacity of 320,000 litres of fuel, packs four 70,000lb thrust engines, carries 555 passengers over two decks and 500 square meters of floor space, and has a duty free shop, bar restaurant and beauty salon.

By Justin Pot

By Nena Farrell

By Charlie Wood

By Angela Watercutter

Mason points out that while this type of “hotel in sky” superjumbo was seen as a technological marvel at the time, “it is now considered an overly expensive aircraft, with four engines that are less efficient than newer engines found on late model, twin-engined aircraft.” He also explains that filling an aircraft with more than 500 seats demands selling at least some of the tickets at low prices. Overall yield is therefore lower than a smaller aircraft, which are easier to fill up. “Airlines have been nervous to commit to very large aircraft”, says Mason. “They often cannot find a sufficient number of suitable routes where demand is high enough to fill the aircraft at a decent yield.”

Airbus was correct in one prediction. It envisaged that flights would continue to be hub-to-hub, involving passenger transfers in major airports. (Think of a flight from Europe to Japan, for example, that requires a stopover in Dubai.) Boeing, in contrast, positioned its 787 as a hub-bypass, made for direct “point-to-point” flights. Here, it's Airbus that has been proven correct. As a Centre for Aviation study puts it, “hubs dominate, yet most airlines prefer medium/large aircraft and not the very large aircraft category, consisting of A380s and 747-8s.” In Boeing’s case, figures show that in 2016 a whopping 73 per cent of 787 flights were made between hubs. Yet, for the reason Mason outlines, this has not been enough to save the A380.

In fact, the sheer lack of demand for the A380 is astonishing, says Grant: “Today over half of all fights operated on the A380 are operated by Emirates and less than 20 carriers globally operate the aircraft type. That in itself tells you how little interest there was from other airlines ” In the end, Grant argues, the “egos” of Emirates and Airbus got the better of sound business decisions. "They got carried away in placing too much emphasis on this idea when others, such as Boeing, felt that we would see longer, thinner long-haul routes emerge with new aircraft technology.”

Tom Enders, Airbus’s chief executive, said the decision was “painful”, but promised customers that the A380 will still “roam the skies for many years to come”. Little over a decade ago, the A380 was seen as the future of aviation. But for Airbus, and the airline industry it relies on, the numbers no longer add up.

This article was originally published by WIRED UK

Paresh Dave

Morgan Meaker

Will Knight

Amanda Hoover

Matt Reynolds

Reece Rogers

Lauren Goode

Project Accounting

- Project Invoicing

Project Resources

Time and Expense

- Business Intelligence

- Architecture

- Contractors

- Engineering

- Management Consulting

- Software Development

- Strategic Consulting

- Technology Consulting

- About Beyond

Customer Resources

Partner Resources

Beyond Software Blog

Failed Project Series - What Went Wrong with the A380?

Project Profitability , Failed Project Series

This post is part of a series of posts on some of the most prominent failed projects and how you can avoid the same pitfalls.

At a cost of over US $6 billion, the Airbus A380 fiasco was extraordinarily expensive considering that its cause was the simple reality of a failure of communication.

Noble Intent Based on an Optimistic Perspective

Since the beginning of the European Union in 1957 (which was called the European Economic Community - EEC or EC - until 1993), the many separate countries have worked to unify their activities for the good of the continent as a whole.

The Airbus aircraft company was one of the first significant attempts at collectivizing international efforts under a single industrial umbrella. In 1967, to "strengthen European cooperation in the field of aviation technology," political leaders from Germany, France, and Britain agreed to participate in the development of an "airbus" that would revolutionize transportation on their continent and around the world.

The international "consortia" also eventually added leaders from both Holland and Spain and had as its goal to be the primary competitor to America's burgeoning airliner industry. Their first project: the A300.

Accessing the Assets of Each

Philosophically, the project offered a virtually unlimited palette of resources from each of the participating countries. The efforts of high industrial achievers in one country, when combined with exceptional contributions from the other countries would, of course, result in unmatched quality and service in any industry they tackled together.

By 1968, each contributing country had identified its experts as leaders for the company and had developed a workshare program that identified who would do what, when, and (most notably) where:

- The French would produce the cockpit, control systems, and the lower center section of the fuselage;

- the British would make the wings;

- the Germans would tackle the rear and forward fuselage sections;

- the Dutch would make the moving parts, such as wing flaps and spoilers, and

- the Spanish were in charge of the horizontal tailplane.

German engineer Felix Kracht was responsible for making "all the pieces come together," regardless of the related flag or language of the separate manufacturers.

Organizationally, the group formed the "Groupe d'Interet Economique" (GIE) under French law with the plan being that each country would have a voice at the top level of the company while maintaining separate business entities within the separate jurisdictions.

Remarkably, from the 1970's through to the 2000's, Airbus built on its original A300 framework, adding innovations and improvements as the industry evolved. By 2004, the company had reorganized into a newly "integrated" company, "Airbus Societe par Actions Simplifee," and established a series of "centers of excellence" at its varied manufacturing sites located around the world, while maintaining its “leadership” board of Directors in France.

Its A380 project, which began in 2000, became a "truly global program" which involved as many as 1,000 companies worldwide. With an anticipated release date of 2002, the company accepted over 50 A380 orders from buyers all over the world. When, by summer 2006, those orders were still not filled, those customers demanded to know what was causing the delays. It turned out to be a culture of miscommunication and territorial divides.

.jpg?width=600&name=airbus%20(1).jpg)

Reorganization Failed to Address the Cultural Problem

The fundamental challenge with Airbus was its broad international straddle, which hampered communications and injected politics and territoriality into corporate actions and decisions. While the company's reorganization had brought leadership into a single location, it did not also relocate management into a single team. Instead, individual teams, located in separate countries and speaking different languages, did not communicate with each other about what they were doing or, more importantly, the changes they had made to plans, methodologies, and schematics.

Consequently, in Germany, engineers used a legacy version of CATIA (a design software program) to develop the miles of wiring for the wings. In France, however, engineers used the updated version of the same software to create the wing structures. The two versions were not compatible with each other. As a result, the German-manufactured wiring did not fit into the French-manufactured wing configuration , and both elements required a complete overhaul before the wings operated correctly.

In all, that single (although monumental) glitch cost the company over US $6 billion to repair and set back production by another two years. Airbus wasn't able to deliver its first A380 to its first customer, Singapore Airlines, until October 2007.

Related - A Lesson in Project Failure

Why was Sydney's National Opera House delivered nearly $100 million over budget and ten years later than expected?

Experts Identify Project Issues

Industry analysts identified several elements that contributed to the debacle:

- A convoluted management structure riddled with managers loyal to national constituents, not to the international conglomerate, slowed decision making (Wall Street Journal, July 9, 2007);

- The "surprisingly Balkanized organizational structure" (Business Week Online, October 5, 2006);

- Unresolved internal disputes (The Economist, January 13, 2007).

In the end, and in consideration of other failures of the company to meet customer expectations, the fundamental challenge presented by the A380 was the fundamentally flawed culture of a company that lacked a single vision and a shared set of values and beliefs. Without a doubt, Airbus enjoyed access to the world's most evolved and innovative aeronautical and aviation experts, but even that couldn't save this project from the squabbling and divisions that occurred across multiple corporate and national borders.

Today, Airbus remains Europe's top airline manufacturer. It survived the A380 disaster because its smaller, less ostentatious planes continued to satisfy customers, and because it revamped its A380 production processes to avoid further delays. In total, Airbus has delivered 215 A380s to customers around the globe. It seems to have learned the two fundamental rules of project management that were so woefully missing prior to the A380 disaster:

- Insist on a single system of truth across all project elements, and

- Insist on communication and collaboration across all project sectors.

For additional information on Beyond Software please contact:

Nicole Holliday [email protected] 866-510-7839

Topics: Project Profitability , Failed Project Series

Subscribe to Our Blog

Recent posts.

© 2023 Beyond Software

BEYOND SOFTWARE is a registered trademark of Beyond Software, Inc. in the U.S.

Privacy Policy

PSA Software

Financial Management

Project Billing

Reports and Dashboards

Integrations

Partner Program

What is resource management?

News & Events

Scholars' Bank

Investigating the airbus a380: was it a success, failure, or combination, description:.

Show full item record

Files in this item

This item appears in the following Collection(s)

- Clark Honors College Theses [1307]

Search Scholars' Bank

All of scholars' bank.

- By Issue Date

This Collection

- Most Popular Items

- Statistics by Country

- Most Popular Authors

Simple Flying

The rise and fall of the airbus a380.

The A380 is out of production but still well in use.

- The A380 has been a great aircraft despite challenges, with 251 orders and a significant impact on the aviation industry.

- Airbus designed the A380 for hub-based travel, a concept that didn't align with the shift to point-to-point operations.

- While the A380 has faced setbacks and retirements, it remains in service with some airlines until the 2040s, with potential future uses explored.

The Airbus A380 has had a fascinating history since its launch in 2005. With a higher capacity than any other aircraft, it offered new opportunities for many airlines. There have been operating and cost challenges, though, which have led to concerns and retirements. The pandemic nearly saw the end for the type, but it has re-entered service extensively since.

Despite its challenges, the A380 remains a great aircraft and an impressive engineering achievement. We are unlikely to see anything this size again in the commercial market for some time. And with 251 orders, it has been far from a failure.

This article takes a look back at the history of the Airbus A380 to date . We focus on the concept, development, and potential of the aircraft and how it has worked well for some airlines but not so well for others. We will also consider its future amidst a difficult secondhand market.

The origins of the A380

The concept of the A380 goes back to the 1970s and the Boeing 747 . The iconic Jumbo Jet was a great success for Boeing (and was its highest-selling widebody until the Boeing 777 took over in 2018). It changed aviation in many ways. Its higher capacity led to shifts in airline economics and lower airfares. And the extra onboard space was used for more luxurious cabin space and new classes of service.

The Boeing 747 - Everything You Need To Know

Airbus was formed in 1970, with several European manufacturers coming together to compete against the larger US companies. Its initial A300 (competing with the Boeing 707) sold well, and Airbus launched the dual A330/A340 program in 1986. It designed a twin-engine and four-engine aircraft together, bringing them to market faster and more cost-effectively than launching two separate aircraft.

But it also wanted to go big and take on Boeing with a high-capacity aircraft. Plans for this began early in the 1980s. Airbus announced it formally at the Farnborough Air Show in 1990, with a proposed target of 15% lower operating costs than the 747.

Airbus looked at several different concepts, eventually settling on a full two-deck, known at the start as the A3XX. Interestingly, Boeing had also looked at this concept for the 747 but failed to make it work for emergency exit and evacuation requirements.

The A380 was designed for hub-based travel

The A380 was not just designed to be bigger than the 747. Airbus believed in the idea of creating high-capacity aircraft for hub-based travel. This would be of interest to airlines with hub and spoke based operations, with flights connecting in hubs and carrying high numbers of passengers on key routes. It would also help with growing congestion at airports.

Want answers to more key questions in aviation? Check out the rest of our guides here .

We know now that this was not the best strategy. Boeing, at the time, was moving forward with the lower capacity 777, an aircraft that would appeal much more for point-to-point operations.

However, Airbus was not alone in thinking that high-capacity aircraft would be popular. Several other manufacturers looked at such development around the same time, including:

- McDonnell Douglas launched a two-deck proposal, the MD-12, in 1992. Despite interest from airlines, there were no orders.

- Lockheed Martin released plans for a Large Subsonic Transport aircraft in 1996. This offered two decks, four aisles, and a capacity of over 900. It failed to get going, though, with too many engineering challenges.

- And Boeing tried twice to launch a larger 747 . This would have stretched the upper deck and introduced upgrades from the 777.

Offering a freighter version and a higher capacity option

At its outset, there was more on offer than just the passenger version we know today. Airbus offered a freighter version, which could have been a great opportunity to grow in the Boeing-dominated freighter market. There were 27 orders from Emirates, FedEx, UPS, and ILFC (International Lease Finance Corporation). However, it was never developed.

The Airbus A380F - The Freighter Plane That Got Scrapped

The A380 was also designed with larger versions in mind. Its wings were designed to support a larger fuselage if required. A larger fuselage version was proposed at launch, with an increased capacity of around 100. There was limited interest (and crucially no orders), though. Nor was there when Airbus tried several times again to offer something larger.

The launch of the A380

The A380 was launched at a ceremony in Toulouse in January 2005. It made its first flight in April 2005 and received certification in December 2006. Early problems crept in, however. Singapore Airlines took delivery of the first A380 in October 2007. Emirates followed it, but not until August 2008.

These delays were costly for Airbus and the A380 program. Its parent company's share price dropped 26% and led to a €5 billion ($5.7 billion) loss. This was also a major factor in the failure of the freighter. As Airbus prioritized the troubled passenger aircraft, freighter customers lost interest.

Love aviation history ? Discover more of our stories here

The A380 is the largest commercial aircraft ever built

With the launch of the A380, Airbus succeeded where several other manufacturers had failed and built the largest commercial aircraft to date. With the current shifts in preference, it is likely to hold this accolade for a long time. It will always stand as a great example of technical achievement and a milestone in aviation.

It is the largest commercial aircraft ever built, by capacity or volume, but not the longest. The 747-8 is 79.95 meters long, compared with 72.72 meters for the A380. The upcoming Boeing 777X will also be longer, with the larger 777-9 reaching 76.7 meters.

And for passenger capacity, it is a clear leader. The typical capacity is around 550, but the maximum (the safety exit limit) is an incredible 853 (no airline has done this). To compare, the 747-8 offers an exit limit of 605 and a typical capacity of 467. Emirates offers the highest capacity with its two-class layout of 615. The 777X will offer a typical capacity of 426.

Read more about the upcoming Boeing 777X

Orders from 14 airlines for the A380

To see the success of the A380, consider its total sales. It has a total of 251 orders from 14 airlines (from Airbus data ). Production, of course, has now ended with the last aircraft delivered to Emirates in December 2021.

That's A Wrap: Emirates Takes The Last Ever Airbus A380

This may be the lowest among current widebodies, but it is still far from unsuccessful for specialized aircraft. Had the freighter version worked out, this would likely have been much higher.

The following airlines ordered the A380:

- Emirates, 123 aircraft

- Singapore Airlines, 19 aircraft. Singapore Airlines was the launch customer for the A380 and also the first to start to retire aircraft.

- Qantas, 12 aircraft.

- British Airways, 12 aircraft.

- Lufthansa, 14 aircraft.

- Etihad, ten aircraft.

- Qatar Airways, ten aircraft.

- Air France, ten aircraft. Air France was the first European airline to take delivery of the A380 in 2009.

- Korean Air, ten aircraft.

- Asiana Airlines , six aircraft

- Thai Airways, six aircraft.

- Malaysian Airlines, six aircraft.

- China Southern, five aircraft

- ANA, three aircraft. ANA was the last airline to start flying the A380, in March 2019.

Emirates and the A380

We can't discuss the success of the A380 without talking about Emirates. It accounts for 123 out of the 251 aircraft ordered and relies on a fleet of just these and the Boeing 777. This has been a great boost for the A380, and the main reason that the program has lasted so long. Put simply, this is because Emirates has made the hub and spoke concept work.

Emirates is a true hub operator, carrying passengers on medium and long-haul flights with connections in Dubai. Emirates senior vice president for operations Hubert Frach explained how this model has worked for the airline. In an interview with Business Insider , he said:

"It works great for our network structure’s long-haul to long-haul connections. It allows us to offer efficient connections between developing economies with well-established economies."

By making such a commitment, Emirates also benefits from operational advantages and cost savings. With any aircraft type, there are advantages in crewing, maintenance, and flight operations due to simplified fleets. Airlines with smaller fleets have struggled with higher costs. Emirates CEO Tim Clark discussed this in comparison with Air France in an interview with Airline Ratings :

“The A380 was a misfit for Air France. They never scaled; they only have ten aircraft. Yes, we faced the same teething problems, but we dealt with them because we were scaled enough to deal with it. If you’ve got a sub fleet of 10 it’s a bloody nightmare, and the costs go through the roof… But if you got a hundred of them, it’s a bit different. Your unit costs in operating with that number are a lot lower than having just ten.”

The decline of the A380

There were several signs of problems even several years before the end of the A380 program. Several airlines had orders but never took delivery, including Virgin Atlantic (six), Transaero (four), Kingfisher (ten), and Hong Kong Airlines (ten). In addition, leasing company Amedeo placed an order for 20 aircraft in 2014 but canceled it in 2019 after failing to find any customers.

5 Carriers That Ordered But Never Received The Airbus A380

Other customers reduced orders. Qantas ordered eight additional aircraft in 2006 but later canceled them. Emirates cut back its order in 2019, canceling 39 aircraft and ordering twin-engine A350 and A330neo aircraft.

It was not just the main production model that suffered declining orders - there were other proposed variants that never reached orders or production.

- An A380 stretched version. At launch, Airbus proposed the A380-200, seating around an extra 100 passengers. Again, in 2007, it proposed a similar-sized A380-900.

- A380neo . This was proposed in 2015, with a stretched fuselage and efficiency improvements. Lufthansa came close to ordering, but it never happened.

- A380plus. This was the last attempt in 2017 to improve the A380. It offered increased capacity (by increasing maximum take-off weight) or range, alongside other improvements.

The A380 program never made a profit

Despite 251 orders, the overall project never made a profit. The development cost of €25 billion ($29.7 billion) was more than twice the original development estimate. One positive is that the volume was high enough that by the end, it was producing each aircraft higher than cost. Bloomberg reported in an analysis of the A380 in 2015:

"One modest success that Airbus aims to celebrate this year is that it no longer produces each A380 at a loss, though the company admits the overall program itself will never recoup its $25 billion investment."

Of course, the pandemic was rough for the A380 - but its end was decided before then. Airbus announced the end of the A380 program in early 2019, with production to end in 2021. This came quickly following a reduction in orders from Emirates. Just one year before, it had expected the program to last at least another ten years.

Why has the A380 lost popularity?

What then went wrong with the A380? Several factors combined to hurt the A380 - both with initial take-up and decline in popularity since.

Improvement in twin engines. A major factor in the decline of the A380 has been the improvement in twin-engine aircraft . Of course, this has affected the A340 and the Boeing 747 as well. At the time of its design, four engines were still an advantage for long-haul over-water flights.ETOPS has changed this, with twins now able to fly much further from diversion airports, opening up more routes. This started with 120 minutes for the Boeing 767, rising to 180 minutes for the 777, and the A350 now has a rating of 370 minutes.

Is There Anywhere You Still Can't Fly With ETOPS?

Move away from hub-based operations. The A380 was designed for hub and spoke operations. Airbus bet big on this working, but there has been more of a shift in preference to point-to-point operations. And with this, a lower-capacity aircraft makes more sense. US airlines are a good example of this - no US airline ordered the A380. China, to a certain extent, has gone the same way. Only China Southern has found a role for the A380 (operating it on busy routes to Los Angeles and domestically from Beijing to Guangzhou).

Limitations in operation . The aircraft is placed in the highest size category, and as such, there are many airports where it cannot operate. This was a major consideration in Boeing’s development of the 777X. It has folding wingtips to ensure it is categorized lower than the A380 and can access more airports.

Failure of the freighter version. The failure of the freighter version was potentially a big setback for the A380. Boeing dominates the freighter market, and the A380 could have worked well for Airbus. The freighter received 27 orders but was never developed. Program delays caused a switch in priority to the passenger version. There were also technical issues with its loading.

Slowdown and retirements from 2020

The past few years have been very significant for the A380. Production ended in 2021 with Emirates' last aircraft being delivered. Retirements have already begun. Singapore Airlines was the first to retire aircraft in 2017. Emirates retired its first aircraft in October 2020 (it was planned before the 2020 slowdown).

The pandemic was a tough time for all aircraft - but worst for the largest ones. There were significant retirements at this time (as there was for the Boeing 747 too).

- Air France retired the whole A380 fleet in 2020.

- Malaysia Airlines retired its aircraft by the end of 2022.

- China South announced full retirement in November 2023 (but it had not operated the aircraft commercially for a year before that).

Many airlines grounded fleets during the pandemic, and for some time, its future was quite uncertain. Flights dropped to almost nothing at the height of the shutdowns, although there were some attempts to keep aircraft flying in freight use.

Since the pandemic, the type has come well back into service. Lufthansa made the decision in late 2022 to reactivate its stored A380 fleet. As with Emirates' large-scale return of the type and plans to keep it much longer, this was partly motivated by delays with new aircraft.

The A380 today and going forward

In 2024, ten airlines are still operating the A380 (based on current data from ch-aviation ):

- All Nippon Airways (ANA) has three

- Asiana has six (five active and one inactive)

- British Airways has 12 (nine active and three inactive)

- Emirates has 119 (90 active and 29 inactive)

- Etihad Airways 10 (four active and six inactive)

- Korean Air has 10 (four active and six inactive)

- Lufthansa has 8 (four active and four inactive)

- Qatar Airways has 10 (six active and four inactive)

- Qantas has 10 (six active and four inactive)

- Singapore Airlines has 13 (10 active and three inactive)

How To Fly On An Airbus A380 In 2024

We will likely still see it in service for some time to come. Many aircraft remain young, and many operators are seeing the benefits again of a large widebody. Emirates has already confirmed that it expects the A380 to remain in service until the 2040s . It has new aircraft on order (the 777X as well as the Boeing 787 and Airbus A350).

There have been retirements, though, and these will continue. With many aircraft coming out of service well before the end of their service life, potential future use is key. Secondhand aircraft available for a good price may be tempting. We are yet to see any current - or new - major operators switch the type in, but there are other uses:

Second-hand airline use. This has happened but has been very limited to date. With a potentially low price for used aircraft, the appeal is clear. The Malta-based charter airline purchased one A380 in 2018. This has seen many different uses, including charter by low-cost airline Norwegian and relief flights during the coronavirus pandemic. At one point, the airline intended to take a second A380, but this did not work out. The one aircraft was retired in 2020.

The next attempt comes from UK startup Global Airlines. So far, it plans to operate four A380s, with routes and other plans not yet announced. It registered its first aircraft (an ex-China Southern A380) in early 2024, and plans to work with Hi Fly to operate initially.

Airbus A380 Startup Global Airlines: Everything You Need To Know

Cargo conversion. As the freighter version's failure showed, the A380 airframe has limitations for freight use. But it remains a high-capacity aircraft, and this is possible. We have seen this done by Hi Fly in 2020, and it could be an option for another operator.

Conversion for private use . While it would be amazing to see a private A380 and all the features it could offer, this has not happened to date. There was reportedly one ordered, but it never led to development (plans included a car garage, Turkish bath, concert hall with stage and grand piano, and several conference rooms).

Read more about the private A380 that was planned by a Saudi prince.

It is unlikely that it will happen - but you never know. In general, the aircraft is just too big. The largest twin-engine aircraft already offer plenty of space for private users, and at a more appealing operating cost. The same challenges of high cost and limited airport operations that have hampered commercial use would also affect private use.

Get the latest aviation news straight to your inbox: Sign up for our newsletters today.

Would you like to share any thoughts on the A380? Are you hopeful airlines will continue to find uses for it, or has it had its day? Let us know your thoughts in the comments section below.

A review of the development of Airbus A380

1. overview.

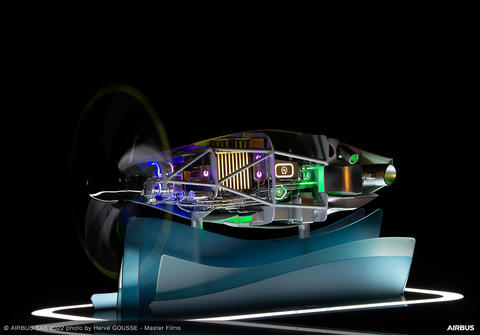

The Airbus A380 is a double-deck, wide-body, four-engine jet airliner manufactured by Airbus. It is the world's largest passenger airliner. The A380 made its maiden flight on 27 April 2005 and entered commercial service on 25 October 2007 with Singapore Airlines. While the airliner created history when it took to flight, its development phase was riddled with issues that brought Airbus to its knees.

Photo: Airbus A380 taking a flight

In this report, we'll examine the project that was undertaken to develop this behemoth of the skies.

2. Timeline

1991: Market demand researched

1993: Boeing cancels large aircraft project

1996: Airbus “Large Aircraft Division” formed

2000: Commercial launch of the A3XX

2002: Component manufacturing begins

Feb: Engine Delivered

May: Assembly begins in the giant £240m factory.

18 Jan: First Press Display – A380 Reveal

27 Apr: Maiden flight/Flight testing and certification begins

Jun: SCHEDULE: Airbus announces that the plane's delivery schedule will slip by six months.

26 Mar: QUALITY: The plane passes a key evacuation test, with 850 passengers and 20 crew managing to leave the aircraft within 78 seconds, even though half the exits were blocked.

29 Mar: EASA and FAA Certification and delays

Jul: SCHEDULE: 6 – 7 months of production delay

Oct: SCHEDULE: Additional 12 months of delay

15 Oct: First A380-800 delivered to Singapore Airlines

25 Oct: Introduction flight with Singapore Airlines

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

“perceived failures” in the projects_ Airbus A380

Analysis on the percieved failures in project, the underlying reasons for these “perceived failures” A case study of Airbus A380. Recommendations on how effective project management could have helped to avoid the problems.

Related Papers

The report investigates factors that led to the A380 project crisis. Analysis of the project revealed that Airbus did not integrate an effective project management model into the project lifecycle leading the project to be two years behind schedule, which eventually led to the costs escalations. The report reveals several lessons to be learned from the A380 project crisis. A project management needs to integrate effective cost management, time management and risk management in the project lifecycle. A mega project such as A380 needs to integrate a detailed risk management, cost and time management plan before project's implementation.

David Pritchard

Introduction The goal of this dissertation is to describe the main economic and political factors underlying the post-1970 decline of the US as a manufacturer of large commercial passenger jets (i.e. aircraft with 100 seats or more). A further goal is to identify the likely sources of future foreign competition in this industry. The main thesis of the dissertation is that foreign producers have acquired a competitive advantage over the US as a result of supportive public policies (e.g. production subsidies), industrial offset agreements (compensatory trade), investment in new manufacturing procedures (e.g. automation), and lower costs. From an industrial futures perspective, the dissertation argues that the US is moving toward a systems integration mode of production (i.e. buy parts from abroad, and assemble at home). This trend implies continued employment losses among US aerospace suppliers, as well as among US aircraft manufacturers. Data for the study come from two main sources. The first source consists of secondary data from corporate reports, industry websites, trade journals, and Federal agencies (e.g. the US Department of Commerce). The second source comes from personal interviews with US and foreign industry representatives, as well as from visits to several aircraft factories in the European Union, Russia, China and the US. The dissertation is organized around three interconnected propositions. First, US aircraft manufacturers must offer industrial offset packages to compete internationally (Offsets are typically organized as production-sharing agreements where the seller transfers part of the manufacturing work to the buyer). Secondly, offset packages deliver aircraft production capability (technology and skills) to potential competitors. Third, Russia, China, and several other newly emerging markets (NEMs) are likely to become serious players in the global aircraft market over the next 10 years or so. Taken together, these three propositions serve as the thematic basis for the dissertation. While the dissertation does not seek to test any particular theory with regard to international business and/or industrial location, some of the empirical findings suggest that certain aspects of Vernon’s (1969) product-life-cycle (PLC) hypothesis are relevant to the US commercial aircraft industry. In particular, the emergence of global subcontracting linkages has in some cases entailed a geographic dispersal of production from high-cost US locations to lower-cost foreign sites (these cases are examined later). In other cases, however, the international decentralization of US production has also included high-cost foreign sites (e.g. Canada, Britain and Japan). This renders the PLC model less pertinent. Some of the dissertation’s findings are also relevant to recent theoretical developments in the field of strategic trade policy (Krugman, 1986). Specifically, the US commercial aircraft industry satisfies all of the current theoretical criteria that define a “strategic industry”. These theoretical considerations, among others, are discussed in the concluding chapter of the dissertation.

Joleber Busa

mustefa mensur

Emmanuel Tyongbea

Hassan H Bodicha

Problem background: The problem of this research paper is centered on project risk management process and its relation to the success of construction projects. Organizations, project managers and all other stakeholders have been complaining of myriads of challenges on how to identify critical factors that can lead to project success. This issue has made these scholars and practitioners to concern themselves with the issue of project success and try to establish some other appropriate factors that measure project success from early as 1960s.These scholars have identified different critical success factors of construction project but how it is impacted on by risk management process is a research gap that this study will try to fill. Purpose: The purpose of this research paper is to establish the effect of project risk management process on the success of construction project. Methodology: The study empirically review literatures on the theoretical framework of project risk management process and its relation to project success in construction industry Conclusions: The study found out that risk factors have significant impact on the success of constructions project success regardless of the type or complexity of the project. This means that the traditional success factors of cost, scope, time and quality are universally inherent in all construction projects and should always be considered as a base for all other forms of critical success factors however this is not a guarantee of project success since the main weakness of project success is not from the traditional success factors but rather the society that is pressurizing project managers to succeed in all tasks. Therefore, critical success factors are necessities aimed at supporting projects managers in tracking various risk factors associated with projects and make an informed decision. Recommendations: Therefore, project managers need to develop a more appropriate critical success factor identification technique in order to avoid the problem of over planning or under planning at the start of the project. When the construction project is being planned, an appropriate measuring tool for critical success factor analysis may need to be identified and defined; this is a gap that needs further research. Also, the literature review on was limited to construction projects only and it is not exhaustive thus confirmation of this work may be done in other sectors. Keywords: Project, risk, risk factors, risk management, project management, project success, success criteria and critical success factors.

Aftab Hameed Memon

Construction projects in Malaysia are currently facing a severe problem of time and cost overrun. It is increasing with the rapid growth in development. The problem of time and cost overrun in resulted from various factors. These factors occur in construction projects at various phases and have different level of risk which is very essential to determine. Hence, this study is carried out through risk matrix for assessing risk level of various factors of time and cost overrun throughout the life cycle of a construction project. This research work involved 35 common factors of time and cost overrun identified from reviewing previous studies published worldwide. For assessing the relatively of those factors and determining their occurrence in various phase of project lifecycle, structured interviews were conducted with 5 experts from construction industry. Experts were asked about the occurrence and severity level of each factor along each phase which were analyzed with average index calculation and risk matrix. The findings revealed that the factors have low and medium risk on time and cost overrun during planning and design phase. While, in the construction phase majority of factors have medium risks and 5 factors have a high risk on time overrun while 6 factors have a high risk on cost overrun. The findings of this study give a better understanding to construction practitioners for risk level of the factors causing time and cost overrun in each phase of construction projects. This will help the practitioners in taking proper actions for improving construction time and cost performance.

ALPAY TARALP

Mostyn Jones

Computational neuroscience attributes coloured areas and other perceptual qualia to calculations that are (as recently argued) realizable in multiple cellular forms. This faces serious issues in explaining how the various qualia arise and how they bind to form overall perceptions. Qualia may instead be neuroelectrical. Growing evidence indicates that (1) perceptions correlate with neuroelectrical activity spotted by locally activated EEGs, (2) the different qualia correlate with the different electrochemistries of unique detector cells, (3) a unified neural-electromagnetic field binds this activity to form overall perceptions, and (4) this field interacts with sensory circuits to help attentively guide perception. The coloured areas in images may thus be seated in the electrochemistry of unique cells, while constancy mechanisms and other multiply realizable computations just help refine these images behind the scenes. This theory is ultimately testable. 1. Computationalist Approache...

RELATED PAPERS

Maria Cristina Biasuz

Bmc Bioinformatics

Broto Chakrabarty

Revue Européenne de Psychologie Appliquée

Mathieu Bessin

ronald flores

Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, 71, 2023/3, 390–421

Anca Filipovici

Hak İş Uluslararası Emek ve Toplum Dergisi

Abdurrahman Sefa ULU

hbgjfgf hyetgwerf

Experimental Brain Research

Shahina Pardhan

Computational Biology and Chemistry

Düzce Üniversitesi bilim ve teknoloji dergisi

Meral Kekecoglu

Onkologia W Praktyce Klinicznej

Jan Walewski

Editorial Universitaria de la Patagonia

Miriam Solis

Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity

Dwi Astiani

Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu

Krystyna Brzozowska

indah lestari

RSC Advances

Eduardo Chamorro

MedEdPORTAL

Todd Cassese

Kirjallisuudentutkimuksen aikakauslehti Avain

Kaisa Kortekallio

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

4 Lessons Learned from the Weirdest Cases of Project Failure

In our previous article in this series, we introduced you to lessons learned from top project failures in construction . But we also want to highlight the weirdest cases of project failure. We shouldn’t forget what can stall our projects, and we should be prepared for anything.

Lesson #1: You never know what will stand in the way

David Millward, a contributor to The Telegraph, recently reported that the stakeholders of a flagship German rail project, Stuttgart 21, have been plagued by yet another project controversy. It turns out that two endangered species of lizard were found on the potential construction site, delaying the prestigious $7.06 billion rail project in southern Germany. The plan was to build the Intercity Express line, a high-speed 35-mile line between Ulm and Stuttgart. But construction was put on hold the moment experts found out that the land on which the line was to be built is also the habitat for thousands of sand and wall lizards, both protected by European Union environmental law. This surprise is expected to cost Deutsche Bahn $16.3 million – this cost will go to relocating the species to a safe and appropriate place some miles away that will be conditioned as their habitat.

Kate Connolly from The Guardian points out that the “costs involved cover the rescue teams, transporting the lizards, planning their new habitats and monitoring their wellbeing.” The stakeholders in this project have already lost 18 months from their schedule, and it remains unknown how much longer they’re going to wait.

Read More: What Questions Await You at the PM Door?