- Teaching Resources

- Upcoming Events

- On-demand Events

Introduction: Early Apartheid: 1948-1970

- facebook sharing

- email sharing

At a Glance

- Social Studies

- Democracy & Civic Engagement

Table of contents:

Triumph of the National Party

- Science, God and Race

Many Nations

The passbook system, the defiance campaign, the freedom charter, women protest, the sharpeville massacre, the rivonia trial, shut down at home, organizing overseas.

The roots of apartheid can be found in the history of colonialism in South Africa and the complicated relationship among the Europeans that took up residence, but the elaborate system of racial laws was not formalized into a political vision until the late 1940s. That system, called apartheid (“apartness”), remained in place until the early 1990s and set the country apart, eventually making South Africa a pariah state shunned by much of the world.

Having aggressively promoted an ideology of Afrikaner nationalism for a decade, the National Party won South Africa’s 1948 election by promising to clamp down on non-white groups. Once in office, the National Party promptly began to institute racial laws and regulations it called apartheid (a word that means “apartness” in Afrikaans). Led by Daniel Malan, a former pastor in the Dutch Reformed Church turned politician, the National Party described apartheid in a pamphlet produced for the election as “a concept historically derived from the experience of the established White population of the country, and in harmony with such Christian principles as justice and equity. It is a policy which sets itself the task of preserving and safeguarding the racial identity of the White population of the country; of likewise preserving and safeguarding the identity of the indigenous peoples as separate racial groups.” 1

- 1 D. W. Kruger, ed., South African Parties and Policies 1910–1960 (London: Bowes and Bowes, 1960), available at Politicsweb, accessed July 29, 2015.

Apartheid Era Sign

The Reservation of Separate Amenities Act (passed in 1953) led to signs such as the one shown above. The Act prohibited people of different races from using the same public amenities.

By 1948, segregation of the races had long been the norm. But as journalist Allister Sparks noted, apartheid, drawing on racist anthropology and racist theology, “substituted enforcement for convention. What happened automatically before was now codified in law and intensified when possible. . . . [Racism] became a matter of doctrine, of ideology, of theologized faith infused with a special fanaticism, a religious zeal.” 1

Religion was an important aspect of Afrikaner identity. Most Afrikaners were members of the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa, a strict and conservative Calvinist church that promoted the belief that the Afrikaners were a new “chosen people” to whom God had given South Africa. Journalist Terry Bell explained the role of religion in the outlook of those who supported the National Party: “Afrikaners [saw themselves] as players in the unfolding of the Book of Revelations, upholding the light of Christian civilization against an advancing wall of darkness. . . . It was God’s will that the ‘Afrikaner nation’ . . . linked by language and a narrow Calvinism, had been placed on the southern tip of the African continent.” 2 As a result, they saw themselves as a select group whose right to the land was greater than any other group’s.

The new National Party administration offered a stark view of ethnic categories. As laid out in the Population Registration Act of 1950, these categories were as follows: “white” (“a person who in appearance obviously is, or who is generally accepted as a white person, but does not include a person who, although in appearance obviously a white person, is generally accepted as a coloured person”), “native” (“a person who in fact is or is generally accepted as a member of any aboriginal race or tribe of Africa”), and “coloured” (“a person who is not a white person or a native”). 3 “Indian” was soon added as a fourth group. The groups were not only portrayed as distinct and fundamentally different; drawing on principles of Social Darwinism, they were ranked hierarchically in terms of supposed intellectual capacity and other attributes. The white population stood at the pinnacle of the South African racial hierarchy, with the National Party ideology claiming that they should dominate the other groups because of their natural superiority. Their control of the state guaranteed whites superior access to education, healthcare, employment, and housing. “Natives,” or black South Africans, stood at the very bottom of this steep hierarchy—a necessity in the eyes of Afrikaners, who believed not only that their livelihoods depended on depriving black South Africans of land, voting rights, the right to marry freely, and, above all, the right to participate freely in the labor market but also that Africans were not as deserving as whites of these privileges. Indian and “coloured” groups were “ranked” above black South Africans, allowing them some employment and mobility privileges denied to black South Africans yet still making them subservient to the white South African population.

| nationality | Percent of Population |

|---|---|

| Native | 68.3% |

| White | 19.3% |

| Colored | 9.4% |

| Indian | 3% |

Science, God, and Race

The triumph of the National Party pushed to the forefront of South African racism the ideas fostered by church leaders and scholars in Afrikaner institutions. During the 1930s, scientific books and articles, some written by scholars at Stellenbosch University and the University of Pretoria, lent credence to the idea that white populations were of superior intelligence to nonwhite groups. The Dutch Reformed Church, whose congregations had been segregated since 1857, also preached that, following the Tower of Babel, God had ordained that different cultures be distinct and sovereign. The church’s ideas combined with the pseudoscience of race to give rise to a secular theology of Christian nationalism. If groups were to develop as God intended, they needed to live separately.

Because they conceived of blacks and whites as fundamentally different, Afrikaners concluded that contact between the groups fostered conflict. Each group would prosper most if left to develop on its own; to impose segregation was to protect and promote black culture, they argued. The 1947 National Party campaign pamphlet explained:

The party holds that a positive application of apartheid between the white and non-white racial groups and the application of the policy of separation also in the case of the non-White racial groups is the only sound basis on which the identity and the survival of each race can be assured and by means of which each race can be stimulated to develop in accordance with its own character, potentialities and calling. Hence inter marriage between the two groups will be prohibited. Within their own areas the non-white communities will be afforded full opportunity to develop, implying the establishment of their own institutions and social services, which will enable progressive non-Whites to take an active part in the development of their own peoples. The policy of our country should envisage total apartheid as the ultimate goal of a natural process of separate development. 4

The reading Apartheid Policies offers a more extended explanation of the ideas behind apartheid, as publicly articulated by the party.

A contradiction arose, however, because if black South African labor had been subtracted from the white South African economy, the latter would have immediately collapsed. While the theory of apartheid argued that the races should be kept separate, the economy of the South African state depended heavily on black South African labor. Therefore, the apartheid state had to permit black South African laborers to come and go between white and black territories.

After the National Party took power, it implemented a series of laws designed both to separate each of the country’s racial groups and to divide and weaken the black South African population and allow for the easy exploitation of its labor. The Population Registration Act created a national system of racial classification that gave every citizen a single identification number and racial label that determined exactly what privileges this person would be able to enjoy. Where one could live, whether one had to carry a passbook to travel, and what sort of education one could receive depended on one’s racial classification. While white South Africans enjoyed every conceivable right, black South Africans could not vote for South African officials, and coloured South Africans could only vote for white representatives—they could not run for office themselves. The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act of 1949 banned interracial marriage, while the Immorality Act of 1950 “prohibited sex between whites and non-whites.”

| Law | Year | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Prohibition of Mixed Marriages | 1949 | Banned marriage between whites and non-whites. |

| Population Registration Act | 1950 | Created a national register in which every individual’s race was officially recorded. |

| Group Areas Act | 1950 | Legally codified segregation by creating distinct residential areas for each race. |

| Immorality Act | 1950 | Prohibited sex between whites and non-whites. |

| Suppression of Communism Act | 1950 | Outlawed communism. Allowed detention on communism charges of those who objected to or protested apartheid. |

| Bantu Authorities Act | 1951 | Created black homelands and governments. |

| Separate Representation of Voters Act | 1951 | Removed coloureds from voter rolls. |

| Bantu Education Act | 1953 | Set up a separate educational system for black South Africans, charged with creating an “appropriate” curriculum. |

| Native Resettlement Act | 1954 | Allowed the removal of black South Africans from areas reserved for whites. |

| Extension of Education Act | 1956 | Excluded black South Africans from white universities. Set up separate universities for each racial group. |

| Terrorism Act | 1967 | Allowed indefinite detention without trial of opponents of apartheid and created a security force. |

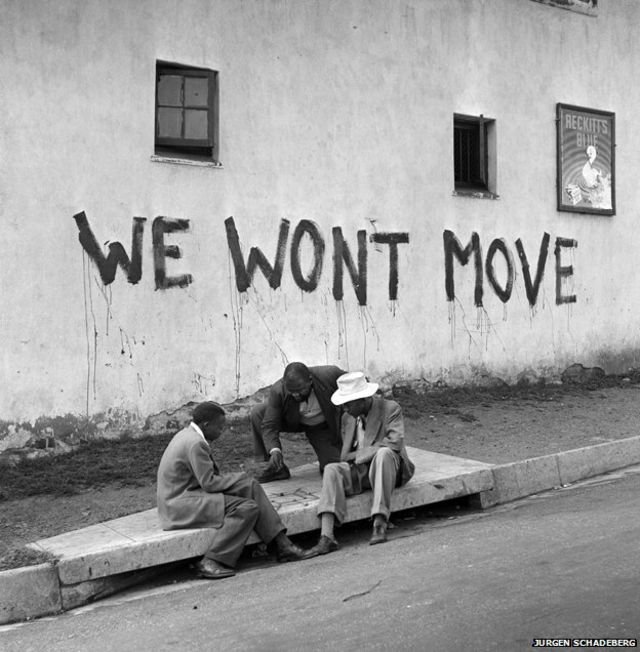

The Group Areas Act of 1950 was the Malan government’s first attempt to increase the separation between white and black urban residential areas. The law was both a continuation of earlier laws of segregation and a realization of an apartheid ideal that cultures should be allowed to develop separately. The law declared many historically black urban areas officially white. The Native Resettlement Act of 1954 authorized the government to force out longtime residents and knock down buildings to make room for white-owned homes and businesses. Whole neighborhoods were destroyed under the authority of this act. For example, on February 9, 1955, Prime Minister Malan sent in 2,000 police officers to remove the 60,000 residents of Sophiatown, a vibrant African neighborhood in central Johannesburg. Black South African residents were forcibly resettled in the Meadowlands neighborhood of Soweto, where they were expected to move into houses without electricity, water, or toilets. In Durban, Indian neighborhoods faced a similar fate. City centers became enclaves for the white South African population, while black, coloured, and Indian South Africans were relegated to townships at the periphery of the urban areas, which were often far removed from centers of employment and resources such as hospitals and recreation spaces. Generally, the townships were intended to contain the black South African population by restricting movement through urban planning while ensuring that black South Africans had permission to leave these areas in order to work.

- 1 Allister Sparks, The Mind of South Africa: The Story of the Rise and Fall of Apartheid (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2006), 190.

- 2 Terry Bell, Unfinished Business: South Africa, Apartheid and Truth (London: Verso, 2003), 23.

- 3 Population Registration Act (1950) , Wikisource entry, accessed July 27, 2015.

- 4 D. W. Kruger, ed., South African Parties and Policies 1910–1960 (London: Bowes and Bowes, 1960), available at Politicsweb, accessed July 29, 2015.

Bantustans in South Africa

With the passing of the Bantu Authorities Act in 1951, the apartheid set in motion the creation of ten bantustans in South Africa, illustrated in this map.

Apartheid laws treated black South Africans not as citizens of South Africa but rather as members of assigned ethnic communities. The Bantu Authorities Act (1951) and the Bantu Self-Government Act (1959) created ten “homelands” for black South Africans, known as Bantustans, and established new authorities in the Bantustans. While the apartheid state portrayed the Bantustans as a system that offered black South Africans independence, giving the appearance of self-government, the leaders of the homelands were appointed by the apartheid state. Furthermore, black South Africans were assigned these ethnic identities and corresponding “homelands” even if they did not see this as a central aspect of their identity. Black South Africans were essentially stripped of their South African citizenship.

By making black South Africans citizens of Bantustans, the government deflected any possible criticisms of refusing them the right to vote in South Africa. But this arrangement also very deliberately created a system of migrant labor. Since the homeland areas, which were mostly rural and underdeveloped, offered inhabitants few employment opportunities, most had to search for work in cities and live temporarily in townships. Given the desperate situation in the homelands, the apartheid state was ensured of a regular source of cheap labor for white-owned businesses and homes.

Although they were said by apartheid authorities to bear a historical association with the different kingdoms, Bantustans were scattered around the fringes of the country without any consideration for the well-being of their residents. KwaZulu in Natal, for example, was divided into many pieces, separated by large areas designated as white. The apartheid government reserved urban areas, the most desirable farmland, and regions rich in natural resources for white South Africans, while it allocated the least arable land for the Bantustans. Although black South Africans constituted nearly 70% of the population, only 13% of South Africa’s territory was allocated to the Bantustans. The reading A Wife’s Lament offers a look at how the creation of the homelands affected black South African families.

Girl Walking to School, Mthatha

A child walks to school through the barren village of Qunu, South Africa, located just outside of the town of Mthatha.

Dividing the black South African population into Bantustans was in part intended to break the solidarity that had formed between groups of black South Africans in the face of white oppression. By cultivating a false sense of “tribal” belonging, the government sought to reduce the black South African population to many small, ineffective groups, channeling discontent from resistance to apartheid into internal bickering.

A decade after the rise of the National Party, many black South Africans found themselves effectively stateless. They could only enter white areas to work, and they needed documents authorizing them to do so.

By the middle of the twentieth century, vast numbers of black South Africans commuted daily from Bantustans and townships to the white areas where they worked. Various forms of internal passports had existed in South Africa since the early twentieth century, but the apartheid government expanded and formalized the pass system. Designed to satisfy both the need for black labor and the need to protect white advantages, “pass” laws required every black male over the age of 16 to carry a passbook, which contained a photograph, fingerprints, a racial classification, place of work, and the bearer’s police record.

Additionally, the passbook had to have a current signature from an employer and proof that the bearer had paid income taxes. The passbook bureaucracy was so convoluted that few people were able keep their records current, providing authorities with an excuse for detaining black South African men at will. Anyone living in a black township on the outskirts of a white city who did not possess appropriate papers was effectively treated as an illegal alien and subject to arrest. Those found in violation were sometimes imprisoned, often forced to pay fines, and sometimes sent back to their homelands. Eventually, black South African women were also required to carry passes, an act that had a tragic impact on the lives of tens of thousands of families who were not allowed to live together. Only a few of these women with formal salaried employment were able to secure the necessary passes and keep them current, thereby satisfying the authorities’ requirements to be legally living in the same house as their husbands. Most black South African women were forced to remain in the homelands, raising their children and eking out a living off the land while their husbands worked in the cities or on white-owned farms.

Most black South Africans were obliged to leave “white areas” by sunset. At the country’s many checkpoints and roadblocks, black South Africans were at the mercy of the police and could summarily be stopped, arrested, and deported to homelands. Thousands of black South Africans were forced to break the law on a daily basis as they searched for work or attempted to keep their families together.

Police carried out daily raids on black residences, bursting in at midnight, forcing residents to show their passes, and arresting those out who did not have them. Police brutality was rife; hundreds of thousands of black South Africans were arrested, thousands disappeared from their homes without a trace, and hundreds lost their lives to the guns and batons of law enforcement officials. The government recruited black South Africans to join the police force and serve as informants, torturers, and, in some cases, executioners, and for a variety of reasons (bribes, economic pressures, and scare tactics), some black South Africans helped the government enforce apartheid. The reading Experiencing Apartheid gives an account of how the draconian enforcement of apartheid laws could affect black South Africans.

As apartheid laws were implemented, South Africa’s black leaders looked for a way to protest the changes imposed by the minority white government. Denied the right to vote, they had to find other means of expressing opposition outside the formal political system. From 1950 to 1952, the African National Congress (ANC) organized mass actions, which included boycotts, civil disobedience, demonstrations, and strikes.

A group of resisters proudly pose after their release from prison in Durban during the Defiance Campaign Against Unjust Laws, 1952.

Launched in April 1952, on the 300th anniversary of the arrival of the first Dutch colonists, this Defiance Campaign became the largest campaign of civil disobedience in South Africa’s history up to that point. It was also the first multiracial mass-resistance campaign, and its unified leadership included representatives from the African National Congress, the South African Indian Congress, and the Coloured People’s Congress. Together with other groups, these organizations formed the Congress Alliance, which forged a multiracial front against the implementation of apartheid. 1 Following heavily attended demonstrations in a number of towns, defiance of the newly erected racial laws commenced on June 26, 1953. Ten thousand volunteers, organized by the leader of the ANC Youth League, 34-year-old Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, were instructed to enter forbidden areas without passes, use entrances designated “Europeans only,” and occupy “white only” counters and waiting rooms. 2 These violations were designed to flood the prison system, rendering law enforcement impossible.

- 1 For Nelson Mandela’s description of the first months of the campaign and the unity between the different groups, see “ We Defy—10,000 Volunteers Protest Against Unjust Laws ,” August 30, 1952, African National Congress website, accessed July 27, 2015.

- 2 Reader’s Digest Illustrated History of South Africa: The Real Story , 3rd ed. (Cape Town: The Reader’s Digest Association Limited, 1994), 385.

Nelson Mandela, 1937

A young Nelson Mandela poses for a photograph in Umtata shortly before moving to Fort Beaufort to attend Healdtown Comprehensive School.

A decade later, Mandela reflected on the goals and strategies behind the Defiance Campaign:

Even after 1949, the ANC remained determined to avoid violence. At this time, however, there was a change from the strictly constitutional means of protest which had been employed in the past. The change was embodied in a decision which was taken to protest against apartheid legislation by peaceful, but unlawful, demonstrations against certain laws. Pursuant to this policy the ANC launched the Defiance Campaign, in which I was placed in charge of volunteers. This campaign was based on the principles of passive resistance. More than 8,500 people defied apartheid laws and went to jail. Yet there was not a single instance of violence in the course of this campaign on the part of any defier. I and nineteen colleagues were convicted for the role which we played in organising the campaign, but our sentences were suspended mainly because the judge found that discipline and non-violence had been stressed throughout. 1

The government lashed out, arresting over 8,000 South Africans and handing out stiff penalties and long prison sentences to those who had broken apartheid laws. It adopted the Public Safety Act (1953), which allowed the president to suspend all existing laws, stripping away basic civil liberties. “The government saw the campaign,” Mandela later recalled, “as a threat to its security and its policy of apartheid. They regarded civil disobedience not as a form of protest but as a crime, and were perturbed by the growing partnership between Africans and Indians. Apartheid was designed to divide racial groups, and we showed that different groups could work together. The prospect of a united front between Africans and Indians, between moderates and radicals, greatly worried them.” 2

While the Defiance Campaign lost momentum after a few months, and it did not achieve many concessions from the government, it was a turning point for South Africa. For the liberation movement, it was the first mass campaign, swelling the membership ranks of the ANC from just 7,000 to 100,000 and helping to transform the group from an elite organization into a mass movement. 3

In early 1955, the ANC organized a listening campaign, in which they sent out 50,000 volunteers to talk with people across the country about their political hopes for South Africa. In June 1955, the ANC, along with several other anti-apartheid political organizations—the South African Indian Congress, the Coloured People’s Congress, the South African Congress of Trade Unions, and the Congress of Democrats—developed a set of political demands that drew on the results of these interviews. The “Freedom Charter,” as it became known, called for a nonracial South Africa, in which people of all races would have equal rights and would share in the country’s wealth.

The Freedom Charter became the political agenda for the ANC, shaping its actions over the next several decades. The charter called for rights for all South Africans, not just black South Africans, and this concept of nonracialism became an important principle behind the ANC’s approach to political change. The Freedom Charter served as the guiding document for the ANC in its struggle against apartheid and beyond, as its nonracialism ultimately became a basis for ANC policies after the fall of apartheid. The reading The Freedom Charter includes the text of this foundational document.

Although their role has often been overlooked in historical accounts of resistance to apartheid, black South African women played an important part in opposing the system of racial segregation. (White and “coloured” women were part of the resistance, but the vast majority were black South Africans.) In the early 1900s, black South African women successfully resisted proposed legislation that would require them to carry passbooks. After a setback in 1918, women organized again to end the practice altogether under the leadership of Charlotte Maxeke, a gifted singer, social worker, and activist—a hero of the early days of protest. She was called “the mother of African freedom in this country” by A. B. Xuma, who served as the president of the ANC in the 1940s. 4

- 1 Nelson Mandela, “ An Ideal for Which I Am Prepared to Die ,” The Guardian , April 22, 2007, accessed July 27, 2015.

- 2 Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1994), 116.

- 3 For a full and vivid description of the campaign, see Monty Naicker, “The Defiance Campaign Recalled,” June 30, 1972, African National Congress website, accessed July 27, 2015.

- 4 Andile Mnyandu, “ Charlotte Maxeke ,” eThekwini Municipality website, accessed July 27, 2015.

Woman Showing Her Passbook

An unidentified black South African woman defiantly shows her passbook.

The multiracial Federation of South African Women was formed in the 1950s, representing hundreds of thousands of women. Together with the ANC Women’s League, the federation organized many local demonstrations against the pass laws, culminating in the March on Pretoria. On August 9, 1956, about 20,000 women peacefully gathered in front of the city’s Union Buildings. They stood in silence for 30 minutes and then, breaking the quiet, chanted a call to the prime minister: “Wathint’ abafazi, wathint’ imbokodo!” (Now that you have touched the women, you have struck a rock!) Alerted to the protest ahead of time, the prime minister, J. G. Strijdom, had slipped out of town. Before they concluded their protest, activists left on the prime minister’s door a petition bearing the signatures of 100,000 women. Their chant became the slogan for future women’s protests. The reading Women Rise Up against Apartheid and Change the Movement features a firsthand account of the 1956 women’s march.

By the late 1950s, a growing number of activists questioned the tactics of the African National Congress. The young founders of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), formed in 1959, believed that only an all-black African organization, in league with anti-colonial Africans throughout the continent, could adopt the forceful posture necessary to overcome apartheid. The time had come, these firebrands believed, to reclaim the land stolen by whites. In his inaugural speech, Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, head of the PAC, outlined their approach:

[W]e reject both apartheid and so-called multi-racialism as solutions of our socio-economic problems. . . . To us the term “multi-racialism” implies that there are such basic insuperable differences between the various national groups here that the best course is to keep them permanently distinctive in a kind of democratic apartheid. That to us is racialism multiplied, which probably is what the term connotes. We aim, politically, at government of the Africans by the Africans, for the Africans, everybody who owes his only loyalty to Afrika and who is prepared to accept the democratic rule of an African majority being regarded as an African. 1

Questioning the effectiveness of nonviolence against apartheid, the PAC set up a military wing, Poqo, that was feared by the white establishment.

The PAC announced to authorities that it would lead a peaceful demonstration against pass laws in the township of Sharpeville on March 21, 1960. Some 5,000 protesters gathered in the town center and then marched toward the police station to turn themselves in for defying pass laws. 2 Around midday, the police panicked and opened fire on the demonstrators, killing 69 people and wounding another 180. Most were shot in the back as they fled.

Black South African leaders called for a day of mourning and a “stay-at-home” strike on March 28, 1960. Hundreds of thousands of black South Africans did not show up for work that day, making it the first successful national strike in the nation’s history. Marches took place in Johannesburg, Durban, and Cape Town; the largest included a group of 30,000 who marched from Langa to Cape Town, led by 23-year-old Philip Kgosana. Fearing that black protests might spread, the government acted decisively in the aftermath of the Sharpeville massacre. It declared a state of emergency and arrested more than 11,000 people, including the leaders of both the ANC and the PAC. On April 8, the government banned both organizations. This put an abrupt end to the protests and ushered in a period of harsh repression that lasted for more than a decade.

During the 1960s, the government intensified its policies against the anti-apartheid movement by severely restricting the ability of the movement’s leaders to speak in public and to mobilize the population. The government went on to scrap what few rights non-white workers had, including the rights to organize, bargain, and strike, and it also intensified efforts to shut down surviving black urban neighborhoods and move the black population to the townships and homelands.

Although officially banned, the ANC continued to function clandestinely. The young leadership of the ANC, having seen their hopes for change dashed so violently, began to discuss a new approach to resistance. Despite opposition from the old guard, in 1961 the young upstarts prevailed: while there would never be official ANC approval, the creation of an armed wing was tacitly accepted. Named Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation,” known as MK), the clandestine group had Nelson Mandela as its commander.

Such a group needed new skills and new partners. Mandela and the other militant ANC members formed an alliance with the South African Communist Party, a multiracial political organization with ties to the Soviet Union that had been banned in 1950 but remained active underground, working primarily to support the interests of workers. They based MK operations at a farm in Rivonia, not far from Johannesburg. Setting up a network of operatives committed to terror permitted MK, over a year and a half, to carry out approximately 200 attacks on government facilities. By January 1962, Mandela had traveled to Algeria, where he learned the basics of guerrilla warfare from members of that nation’s National Liberation Front. A fortnight after his return to South Africa, he was arrested on the charges of inciting workers to strike and leaving the country without a passport. A year later, Mandela’s MK comrades were arrested at their Rivonia training camp.

In 1963, three years after the terror of the Sharpeville massacre carried out by government forces, the Rivonia Trial began with the government seeking to accuse its opponents of fomenting violence. Ten defendants, including six black Africans, three white Jews, and the son of an Indian immigrant, were charged with sabotage and attempting to violently overthrow the government of South Africa.

During the trial, the defendants decided not to deny the charge of sabotage. They wanted the world to know what they had done and why. Their lawyers expressed misgivings about their decision, because it meant that they could be put to death for treason. But the revolutionaries felt that they had to take the risk, using the trial to make their positions known to every person in South Africa.

When he took the stand at the Pretoria Supreme Court, Mandela described his personal journey within the resistance movement, explaining the reasoning behind the adoption of a militant approach. (The reading Mandela on Trial includes the text of this testimony.) The prosecutor attempted to prove that the group, which he labeled communist, was plotting to overthrow the government of South Africa. He played on Afrikaner fears of Soviet revolutionary plots. The government had long presented itself as a true ally of the West, securing generous financial and military support—a position unusual among African states, many of which adopted socialism as a reaction against the colonial powers they had thrown off.

When the trial ended in June 1964, two men had been acquitted. Six of the remaining eight, including Mandela, were found guilty on all counts and sentenced to life in prison.

In the aftermath of the Sharpeville massacre and the government crackdown that followed, the ANC leadership charged Oliver Tambo, the organization's deputy president, with the task of beginning to organize overseas. With protest nearly impossible within the country and so many top ANC leaders in prison, Tambo looked for new ways to fight against the apartheid regime. Making use of a home base in London, he lobbied international leaders to speak out against the brutality in his homeland. Almost immediately, Tambo and British anti-apartheid movement activists organized to have South Africa removed from the British Commonwealth, an intergovernmental organization made up of countries that were formerly part of the British Empire—a move that succeeded in 1961. At the same time, activists began to lobby against South Africa in the United Nations, winning a 1962 vote at the UN General Assembly for a trade ban on South Africa. A partial arms ban followed a year later. Further international pressure against South Africa’s discriminatory policies came from the International Olympic Committee, which first suspended South Africa from participating in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and then formally banned the country from the Olympics in 1970. The ANC, with Tambo’s leadership, eventually set up 27 overseas missions.

However, diplomacy was only one part of the strategy. In 1965, the countries of Tanzania and Zambia agreed to let the ANC’s unofficial armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), set up paramilitary training camps. Under the leadership of Abongz Mbede and Joe Slovo, a South African Jew whose family emigrated from Lithuania, the MK sought to bring what they called an “armed struggle” to South Africa. In the late 1960s, though, South Africa was surrounded by neighbors that were allies of the apartheid government, making it difficult for fighters to make it into the country. An official history of the ANC describes the situation:

The ANC consultative conference at Morogoro, Tanzania in 1969 looked for solutions to this problem. . . .The Morogoro Conference called for an all-round struggle. Both armed struggle and mass political struggle had to be used to defeat the enemy. But the armed struggle and the revival of mass struggle depended on building ANC underground structures within the country. A fourth aspect of the all-round struggle was the campaign for international support and assistance from the rest of the world. These four aspects were often called the four pillars of struggle. The non-racial character of the ANC was further consolidated by the opening up of the ANC membership to non-Africans. 3

- 1 “ Robert Sobukwe Inaugural Speech, April 1959 ,” African National Congress website, accessed June 2018.

- 2 David James Smith, Young Mandela: The Revolutionary Years (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2010), 210.

- 3 “ A Brief History of the African National Congress ,” African National Congress website, accessed June 2018.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, “ Introduction: Early Apartheid: 1948-1970 ,” last updated August 3, 2018.

This reading contains text not authored by Facing History & Ourselves. See footnotes for source information.

You might also be interested in…

10 questions for the future: student action project, 10 questions for the present: parkland student activism, the union as it was, radical reconstruction and the birth of civil rights, expanding democracy, voting rights in the united states, my part of the story: exploring identity in the united states, the struggle over women’s rights, equality for all, protesting discrimination in bristol, how to read the news like a fact checker, the 1963 chicago public school boycott, inspiration, insights, & ways to get involved.

- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

Forced Removals in South Africa

Forced removals refer to the moving of people from their homes against their will. This may not always involve physical threat or force, but sometimes coercion or other tactics against which the evictees are not in a position to challenge are employed [i] . Examples of the types of tactics used to move people against their will from their homes will be illustrated further below.

South Africa has experienced a long history of forcible removal of people as the result of racist legislation. It is incredibly difficult to calculate precise numbers of people who experienced forced removal in the country It is equally difficult to pinpoint a specific origin for the legislation, that segregated South Africa’s cities into racially constructed group areas. Earlier discriminatory laws were often used as platforms for building new ones during the apartheid era, [ii] so to understand those which famously occurred under the Group Areas Act (and heavily influence urban landscapes today), it is important to consider the legislation preceding that which occurred under apartheid rule. It is also worth noting that economic conditions in South Africa today have seen forced removals continue across the country. [iii]

While apartheid saw the rigorous implementation of removals on a massive scale, segregation and forced removals occurred before the National Party came into power and introduced apartheid legislation [iv] . Examples of pre-apartheid legislation include the 1913 Native Land Act , the 1906 and 1908 Asiatic Law Amendment Ordinance 29 , and the 1936 Native Trust Land Act . [v] These items of legislation served to limit the freedom of all people not classified as White)living in South Africa by controlling their movement, limiting their power to own land or businesses and exploiting their labour to the benefit of White South Africans [vi] .Some of apartheid’s most oppressive legislation (such as the Group Areas Act ) was built upon these earlier regulations that sought to control the movements and rights of all who were not White (for example, the 1925 Areas Reservation Bill sought to restrict Indians). [vii] However, it was the Group Areas Act of 1950 that formalised and rigorously implemented forced removals on an enormous scale; from its promulgation on the 7th of July 1950 to its repeal in 1991 under the Abolition of Racially Based Land Measures Act .

For a concise overview of segregationist legislation dating back to 1856, view South African History Online’s timeline on segregationist legislation .

Pre-cursors to the Group Areas Act

“ You can’t say there is an unfair division of land, because land was divided by history… we’ve pegged it down and that’s final.” – The Deputy Minister of Bantu Administration and Development, 1975. [viii]

While the Group Areas Act legislated the forced segregation of people according to the ethnic groupings they ‘belonged to’ (these identities were assigned to people by the apartheid government).Segregation existed long before apartheid was implemented and was already instituted by colonial authorities through various urban planning efforts. [ix] The earliest evidence of forced removal on this landscape dates to the seventeenth century when San and Khoi inhabitants were dispossessed at the Cape by European settlers under the leadership of Jan Van Riebeeck, when the Dutch East India Company elected to create a permanent settlement at the Cape. While the dispossession of indigenous people during the time of early European settlement differed in nature to forced removals under the Group Areas Act, a similarity is reflected in the entrenched attitudes of those in power many centuries later, resulting in large-scale forced removals throughout the country. [x] Colonial authorities, having established control and discrimination by White people over all those who were not classified as White, passed legislation that reflected the efforts of the authorities to retain this control, resulting in people being forced from one location to another. Examples include the series of acts promulgated in the early 1900s in order to restrict the freedom of Asian South Africans who saw their rights to trade within the areas referred to as Asiatic Bazaars removed, as legislation became more and more discriminatory toward them.

See South African History Online’s Timeline of Anti-Indian legislation for a closer look at this series of discriminatory laws.

Other attempts to legally segregate the populace by ethnic distinction included a long list of discriminatory laws that can be traced back as far as the nineteenth century.Legislation such as the 1920 Native Affairs Act, the 1924 Class Areas Bill, the 1934 Slums Act and many more, led up to the eventual enforcement of separate 'Group Areas' from 1950 onward, resulting in mass evictions and forced removals. A good example of one of the ways that legislation forced people unjustly from their homes is the anti-squatting legislation in 1880 and 1908. Driven by White farmers to fulfil needs for cheap labour, they successfully lobbied for legislation. This forced cash-tenants (people who rented their land from farmers) to become labour tenants (people who worked for 3-9 months per year without pay on farms in exchange for being allowed to live there).The people in question were Black people for who opportunities to own land were severely restricted. Those affected by these anti-squatting laws had the following options: to accept the farmer’s offer of taking labour tenancy over cash tenancy, move out, or be prosecuted as a squatter. Legal tenants could be considered ‘squatters’ because farmers had power to label them as such. Farmers would coerce them into changing their status to labour tenants. In this way many people were forced to move from their homes. Similarly, under the 1913 Land Act, many Black people living as cash tenants and share-croppers on White-owned land were restricted from owning land and forced off of land that they rented. In areas like the Free State Black people were coerced to accept labour tenancy over cash. Not only did this lead to the disempowerment and dispossession of a large number of Black people, it also provided White farmers with increased power and access to labour from people made vulnerable by the new legislation. [xi]

For a full list of segregationist legislation, visit South African History Online's timeline, which documents the laws put in place to enforce segregation along racial lines in South Africa .

By the time the Group Areas Act was promulgated, Black South Africans were already officially restricted from living or moving within most areas not designated to them throughout South Africa. This was as a result of legislation such as the 1923 Natives (Urban Areas) Act. [xii] However, it was difficult for authorities to enforce regulations to ensure the racial segregation of neighbourhoods. Many areas, particularly those in close proximity to areas with employment opportunities, were ethnically diverse despite attempts to restrict this diversity. In the Western Cape, areas such as Windermere grew out of the increasing need for people to find housing closer to work opportunities, resulting in multi-ethnic living spaces that was home to many families before the eventual removal of its Black residents from 1953 onward.

In 1931, the Cape Province Municipal Association (CPMA) requested that the limitations on freedom already enforced upon the Black population as part of the 1923 Natives (Urban Areas) Act, be extended to apply to Coloured people as well. [xiii] This included determining where people were allowed to live, which amenities they were to use and in many ways was similar to the later restrictions implemented by the Group Areas Act. Efforts to legislate this segregation saw an upsurge of large-scale protest by members of the public and the recommended amendments were referred instead to national authorities by provincial decision makers, [xiv] thus temporarily thwarting the CPMA attempts to implement segregationist legislation against Coloured people.

In another step toward enforced segregation, the late 1930s and early 1940s saw the implementation of pegging laws which limited the freedom of Indian South Africans. Pegging refers to the prevention of free selling or purchasing of land, meaning that Indian land owners were neither allowed to sell land already owned nor have the freedom to purchase new land.

The examples listed above are some of the measures implemented prior to the drafting and enforcement of the Group Areas Act, which paved the way for forced segregation under apartheid. However, until 1950no comprehensive legislation was in place that would allow the government to institute segregation of its populace according to their ethnic classification at national level. People found ways to live and work among one another as urban areas expanded and circumstances created by World War II brought increased urbanisation and industrialisation. The resultant increased need for labour necessitated some leniency of segregationist laws. [xv] This was of concern to those in powers and to members of the White population who did not wish to share their living environments with those from other population groups. They apparently did not want to have their neighbourhoods and communities encroached upon by what was referred to as 'irregular settlements’ in government documentation [xvi] . As a result, legislation was created to limit the freedom of all non-white residents. [xvii]

After World War II, the South African government under Jan Smuts made attempts at managing the growing urban populations through careful urban planning. This included the creation of distinct and separate areas for different population groups, as indicated by correspondence between planning officials at the time. [xviii]

In 1946 the Asiatic Land Tenure Act was promulgated and is considered to be a “direct precursor to the Group Areas Act” [xix] . Informally known as the 'Ghetto Act', this enforced further limitations upon Indian people living in Natal . They were denied the right to purchase property in areas defined as ‘controlled’ [A1] where only Whites were allowed to own land. Furthermore they were only allowed to lease land in these controlled areas on condition that they were using the land for trading purposes.

Forced removals under the Group Areas Act

“We make no apologies for the Group Areas Act, and for its application. And if 600 000 Indians and Coloureds are affected by the implementation of that Act, we do not apologise for that either. I think the world must simply accept it. The Nationalist Party came to power in 1948 and it said it would implement residential segregation in South Africa… We put that Act on the Statute Book and as a result we have in South Africa, out of the chaos which prevailed when we came to power, created order and established decent, separate residential areas for our people.” Senator PZ van Vuuren, speaking in parliament in 1977 [xx]

By 1982, under the Group Areas Act of 1950, over 3.5 million people were forcibly removed and many more faced removals thereafter. [xxi] These removals were documented by activist research projects such as the Surplus People’s Project [T2] (SPP) under the co-ordination of Laurine Platzky [xxii] as well as The Discarded People by Cosmas Desmond [xxiii] . To date, millionsof people have experienced forced removals at the hands of state authorities and countless numbers asa result of private evictions by landowners in rural areas. [xxiv] Black farm labourers make up the biggest group of people to have been forcibly removed from their homes. [xxv]

The Group Areas Act stated that its purpose was to “provide for the establishment of group areas, for the control of the acquisition of immovable property and the occupation of land and premises, and for matters incidental thereto”. [xxvi] Essentially, this Act prevented people from purchasing or selling property between racial groups and ensured that members of these designated groups were limited to living within certain urban spaces. Urban areas were divided into zones according to racial grouping and people were prevented from owning or leasing residential or commercial property in areas where their designated racial group was not legally allowed to live. Central urban areas deemed attractive to live in were designated as White-only zones (e.g. seaside locations, attractive suburban spaces, lucrative farming locations), whilst areas further away from the suburbs were zoned for use by Black, Coloured or people of Asian heritage (e.g. the Cape Flats in Cape Town and areas such as KwaMashu in Durban and Soweto in Gauteng). The board that administered the Group Areas Act was modelled after the Asiatic Land Tenure Board, = headed by the Minister of the Interior. This board had up to seven members who determined which areas would be proclaimed group areas or not.

There were a number of different types of removals that occurred under the act. According to Gerhard Maré [xxvii] , removals could be divided into 11 categories: farm removals, black spot removals, ‘badly situated’ area removals, urban relocation, informal settlement removals, influx control, group areas removals, removals that occurred because of the development of infrastructure, military/strategic removals, political removals (e.g. banishment) and Bantustan betterment scheme removals.

For a full glossary of terms [T3] , including those listed above, please visit the Surplus People’s Project’s glossary of terms relating to forced removals in South Africa available on South African History Online.

Methods of forcing people from areas where they were not desired included violent action (bulldozing homes, threatening people with weapons), as well as seemingly non-violent methods (spreading fear, bribing community leadership, intimidating residents, imposing unfair building restrictions as well as closing schools and stores). [xxviii] When people moved away from their neighbourhoods as the result of non-violent action as described above, the government frequently described this movement as ‘voluntary’, because they were not physically threatened out of the area. This allowed the government to declare that forced removals were no longer occurring in South Africa, despite the fact that people were moving out of declared areas against their will. [xxix]

People affected by removals under the Group Areas Act

Apart from a small number of White people, the majority of those affected by removals under the Group Areas Act have been Black, Coloured and Asian (largely Indian). While popular opinion has it that there were few Black people living in urban centres because of earlier legislation that prevented this, there were many Black people living in what would later become ‘controlled’ areas. They were evicted under the Group Areas Act along with Coloured and Indian people. Frequently areas where Black people resided were declared Coloured or Indian group areas and Black people were forced out. In Durban, for example, an estimated 80 000 Black people were forcibly removed in 1961 as the result of group areas proclamations. [xxx]

In the 1950s, after the National Party came into power and instituted fierce segregationist legislation, a series of campaigns including the Defiance Campaign , boycotts, strikes and anti-pass campaigns were launched by the ANC and its allies. This further fuelled the Nationalist government efforts to remove all Black people from urban areas and allow the government more control over them. [xxxi] By the 1990s, a very small number of Black people remained in areas that were declared White, where they resided as service workers to White employers (e.g. domestic cleaners, gardeners, etc.). They remained socially segregated, however, and were forced to live in domestic/servants’ quarters on white-owned properties. [xxxii]

Once people were forcibly removed and ‘resettled’, the communities that they once belonged to were destroyed, leaving their members scattered across a variety of areas with little opportunity to reconnect and re-establish their former relationships. Some families broke apart when certain members of the family used the opportunity to take on different ethnic identities from other family members (e.g. some light-skinned Coloured people could sometimes assume White ethnic identities and therefore the same rights as White people). Oral history testimonies offer further insight into such experiences and reveal the difficulties and traumas experienced by individuals and groups who were forced to separate from their homes and community members.

“I tell my children about Simon’s Town; swimming, the mountain! You know what my children tell me? And you brought us up in this hole! They can’t understand that I had such a happy childhood. Here they can’t go anywhere. There is nothing for them… They don’t like Ocean View… They don’t even have friends, their family is their friends.” Mrs J.O. Ocean View, Western Cape [xxxiii]

Each province experienced forced removals in unique ways that were affected by the area’s industry, as well as the ethnic groups of the people who lived there. For example, the Transvaal and Eastern Cape saw the increasingly devastating effects of forced migrant labour. The Eastern Cape too saw growing tensions between its Black and Coloured populations,brought about by apartheid legislation such as the Coloured Labour Preference Policy, which resulted in some forced removals. Between Bantustans too there grew increased conflict, with segregation enforced by legislation and the under-resourced and overwhelmed Bantustans struggling to provide employment, services and opportunities to their rapidly growing populations; made up of people who were forced from their homes to their ‘homelands’. Indian people found their economic prosperity diminished by the increased restrictions of segregation and were often driven into poverty when they were forced out of their homes and businesses.

Some people experienced removals from their homes to make way for leisure spaces for White people only while others were evicted in order to build infrastructure such as electricity or water supply that they had no access to. [xxxiv] There was no limit to the reasons behind forced removals or the ferocity of its implementation.

In addition, White people made large profits out of the Group Areas Act and forced removals, particularly developers and speculators, from people who were forced to sell their homes cheaply out of intimidation and fear of the law. Suburbs such as Mowbray and Harfield Village in Cape Town are examples where gentrification of the neighbourhoods arrived on the backs of forced removals, resulting in enormous profit for buyers and sellers of property. [xxxv]

Forced removals in modern times

The numerous latter instances of removals have been little-studied and documented; although evidence has shown that they continue into current times. [xxxvi] Unlike the evictions enforced by government action, these types of removals are hard to trace or tallybecause they occur on private farms and residences across the country. They are often initiated for economic reasons (e.g. mechanisation or industry changes), but because of the entrenched disparities among ethnic groups in South Africa, have a serious effect on racial inequality in the country. [xxxvii]

Economic conditions influence access to land and property the world over and protests against evictions in the face of gentrification projects or industry are common in many countries that experience economic diversity or poverty. [xxxviii] South Africa, however, because of forced racial segregation, has a unique landscape upon which this new tool of forced removal is occurring, and this has inspired much conversation and protest around continued further divides (physical, economic, social, and more) in the country. Dispossession has affected a number of generations of people in South Africa as a result of earlier racist laws from the colonial era to modern timesand this is therefore an important issue to the majority of South Africans; some of whom are being forced out of homes or neighbourhoods today for economic reasons.

For an overview of Land Dispossession and Segregation in South Africa for the first half of the 20th century (legislation which served as pre-cursors to apartheid laws), please view South African History Online’s timeline .

As the result of the wealth of discriminatory laws placing restrictions on where people in South Africa were allowed to move and live; many people were forcibly removed from one place to another – sometimes multiple times, depending on changes in the legislation. In some cases, such as Hangberg in the Western Cape, people who were forcibly removed under apartheid legislation are now facing the threat of removal because of economic pressure (diminished job and housing opportunities, increased rates, opportunistic development schemes).

Many generations of South Africans have either directly experienced, or have been under threat of, forced removals under unjust legislation and the often violent implementation thereof. While violence may not always have been a marker of a forced eviction or ‘resettlement’, the evictions and ‘resettlements’ were no less forced owing to the power of intimidation, economic pressure and other threats placed upon the victims of removals. Millions of South Africans were moved, sometimes more than once, in order to create segregated living and working conditions in which one ethnicity was favoured at the expense of others. Land and labour were extracted from those who were rendered vulnerable by these restrictions to their rights; leaving the South African landscape demarcated by racial and class segregation, causing animosity between ethnic groups and extreme division between wealthy and poverty-stricken areas. The legacy of forced removals continues to affect South Africans because of this favouring of some people and some areas over others. Protest action in South Africa often centres on the structural inequality and racial tensions to which forced removals contributed.

[i]Surplus People Project (South Africa), 1983. Forced removals in South Africa: Volume 1[-5] of the Surplus People Project report, Pietermaritzburg: The Surplus People Project. ↵

[ii]Maylam, P. 1995. Explaining the Apartheid City: 20 Years of South African Urban Historiography. Special Issue: Urban Studies and Urban Change in Southern Africa, Vol. 21, No. 1, 19-38. ↵

[iii]Serino, K. 2015. Gentrification in Johannesburg isn’t good news for everyone. Aljazeera America, [Accessed 21 April 2016]. http://america.aljazeera.com/multimedia/2015/3/Gentrification-in-Johannesburg.html. ↵

[iv]Surplus People Project (South Africa), 1983. Forced removals in South Africa: Volume 1[-5] of the Surplus People Project report, p 31. ↵

[v]Baldwin, A. 1975. Mass Removals and Separate Development. Journal of Southern African Studies [Online]. Vol. 1, No. 2, 215-227. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2636572 [Accessed 22 April 2016]. ↵

[vi]Surplus People Project (South Africa), 1983. Forced removals in South Africa: Volume 1[-5] of the Surplus People Project report. Surplus People Project. p 31. ↵

[vii]Mabin, A. 1992. Comprehensive Segregation: The Origins of the Group Areas Act and Its Planning Apparatuses. Journal of Southern African Studies, [Online]. Vol. 18, No. 2, 405-429. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2637274?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed 19 April 2016]. This url number does not work??? ↵

[viii]Rand Daily Mail, 7 November 1975; in Platzky, L. 1985.The surplus people: forced removals in South Africa. Johannesburg : Ravan Press. ↵

[ix]Mabin, A. 1992. Comprehensive Segregation: The Origins of the Group Areas Act and Its Planning Apparatuses. Journal of Southern African Studies, [Online]. Vol. 18, No. 2, 405-429. Available at:http://www.jstor.org/stable/2637274?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed 19 April 2016]. P 408. This url number does not link me to the site ↵

[x]Platzky, L. 1985. The surplus people: forced removals in South Africa. Johannesburg :Ravan Press, p 71. ↵

[xi]Surplus People Project (South Africa), 1983. Forced removals in South Africa: Volume 1[-5] Surplus People Project report. Surplus People Project. p 36. ↵

[xii]Mabin, A. 1992. Comprehensive Segregation: The Origins of the Group Areas Act and Its Planning Apparatuses. Journal of Southern African Studies, [Online]. Vol. 18, No. 2, 405-429. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2637274?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed 19 April 2016]. p 408. ↵

[xiii]Mabin, A. 1992. Comprehensive Segregation: The Origins of the Group Areas Act and Its Planning Apparatuses. Journal of Southern African Studies, [Online]. Vol. 18, No. 2, 405-429. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2637274?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed 19 April 2016]. p 409. ↵

[xiv]Mabin, A. 1992. Comprehensive Segregation: The Origins of the Group Areas Act and Its Planning Apparatuses. Journal of Southern African Studies, [Online]. Vol. 18, No. 2, 405-429. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2637274?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed 19 April 2016]. p 410. ↵

[xv]Mabin, A. 1992. Comprehensive Segregation: The Origins of the Group Areas Act and Its Planning Apparatuses. Journal of Southern African Studies, [Online]. Vol. 18, No. 2, 405-429. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2637274?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed 19 April 2016]. p 412. ↵

[xvi]Surplus People Project (South Africa), 1983. Forced removals in South Africa: Volume 1[-5] of the Surplus People Project report ↵

[xvii]Christopher, A.J. 1990. Apartheid and Urban Segregation Levels in SouthAfrica, Urban Studies, Vol. 27, No. 3, 1990 421-440, p 428. ↵

[xviii]Mabin, A. 1992. Comprehensive Segregation: The Origins of the Group Areas Act and Its Planning Apparatuses. Journal of Southern African Studies, [Online]. Vol. 18, No. 2, 405-429. Available at:http://www.jstor.org/stable/2637274?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed 19 April 2016]. p 416. ↵

[xix]Mabin, A. 1992. Comprehensive Segregation: The Origins of the Group Areas Act and Its Planning Apparatuses. Journal of Southern African Studies, [Online]. Vol. 18, No. 2, 405-429. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2637274?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed 19 April 2016]. p 417. ↵

[xx]Western, 1981.P85, in Platzky, L. 1985. The surplus people : forced removals in South Africa. Johannesburg :Ravan Press, p 100. ↵

[xxi]Surplus People Project (South Africa), 1983. Forced removals in South Africa: Volume 1[-5] of the Surplus People Project report. ↵

[xxii]Platzky, L. 1985. The surplus people : forced removals in South Africa. Johannesburg :Ravan Press. ↵

[xxiii]Desmond, C. 1972. The discarded people : an account of African resettlement in South Africa Baltimore: Penguin Books. ↵

[xxiv]Mabin, A. 1987.The Land Clearances at Pilgrim's Rest. Journal of Southern African Studies, [Online]. Vol. 13, No. 3, 400-416. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2636389 [Accessed 19 April 2016]. ↵

[xxv]South Africa: Overcoming Apartheid. 2016. South Africa: Overcoming Apartheid. [ONLINE] Available at: http://overcomingapartheid.msu.edu/multimedia.php?id=65-259-6. [Accessed 22 April 2016]. ↵

[xxvi]Statutes of the Union of South Africa, 1950, Act no. 41 of 1950. ↵

[xxvii]Mare, G. 1981.“African Population Relocation” http://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/DC/ChMay81.1024.8196.000.005.May1981.8/ChMay81.1024.8196.000.005.May1981.8.pdf. ↵

[xxviii]Surplus People Project (South Africa), 1983. Forced removals in South Africa: Volume 1[-5] of the Surplus People Project report, p 1. ↵

[xxix]Surplus People Project (South Africa), 1983. Forced removals in South Africa: Volume 1[-5] of the Surplus People Project report, p 1. ↵

[xxx]Platzky, L. 1985. The surplus people: forced removals in South Africa. Johannesburg :Ravan Press, p 100. ↵

[xxxi]Platzky, L. 1985. The surplus people: forced removals in South Africa. Johannesburg : Ravan Press, p 104. ↵

[xxxii]Christopher, A.J. 1990. Apartheid and Urban Segregation Levels in South Africa, Urban Studies, Vol. 27, No. 3, 1990 421-440 p 438. ↵

[xxxiii]Thomas, A. 2001 “It changed everybody’s lives: the Simon’s Town Group Areas Removals” in Field, S. Lost Communities, Living Memories: Remembering Forced Removals in Cape Town. 1st Edition.Cape Town:David Philip Publishers.p 96. ↵

[xxxiv]The Surplus People's Project, The SPP Reports Vol 4, p238. ↵

[xxxv]Platzky, L. 1985. The surplus people: forced removals in South Africa. Johannesburg :Ravan Press, p 102. ↵

[xxxvi]Kinnear, J. 2015. Farmworkers battle widespread evictions. IOL, 5 April 2015. http://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/western-cape/farmworkers-battle-widespread-evictions-1841165. ↵

[xxxvii]Turok, I. 2001. Persistent Polarisation Post-Apartheid? Progress towards Urban Integration in Cape Town. Urban Studies, [Online]. 38, 13, 2349–2377. Available at: http://usj.sagepub.com.ezproxy.uct.ac.za/content/38/13/2349.full.pdf [Accessed 25 April 2016]. ↵

[xxxviii] Brenner, N., 2011. Cities for People, Not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City. 1 Edition.Routledge. ↵

Surplus People Project (South Africa), 1983. Forced removals in South Africa: Volume 1[-5] of the Surplus People Project report, Pietermaritzburg: The Surplus People Project. |Baldwin, A. 1975. Mass Removals and Separate Development. Journal of Southern African Studies, [Online]. Vol. 1, No. 2, 215-227. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2636572 [Accessed 22 April 2016]. |Brenner, N. 2011. Cities for People, Not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City. 1st Edition.Abingdon/New York: Routledge. |Christopher, A.J. 1990. Apartheid and Urban Segregation Levels in South Africa, Urban Studies, Vol. 27, No. 3, 1990 421-440. |Desmond, C. 1971. The discarded people: an account of African resettlement in South Africa. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd |Kinnear, J. 2015. Farmworkers battle widespread evictions. IOL, 5 April 2015. http://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/western-cape/farmworkers-battle-widespread-evictions-1841165 |Mabin, A. 1987.The Land Clearances at Pilgrim's Rest. Journal of Southern African Studies, [Online]. Vol. 13, No. 3, 400-416. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2636389 [Accessed 19 April 2016] |Mabin, A. 1992. Comprehensive Segregation: The Origins of the Group Areas Act and Its Planning Apparatuses. Journal of Southern African Studies, [Online]. Vol. 18, No. 2, 405-429. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2637274?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed 19 April 2016]. |Mare, G. 1981.“African Population Relocation” http://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/DC/ChMay81.1024.8196.000.005.May1981.8/ChMay81.1024.8196.000.005.May1981.8.pdf [Accessed 10 April 2016] |Maylam, P. 1995. Explaining the Apartheid City: 20 Years of South African Urban Historiography. Special Issue: Urban Studies and Urban Change in Southern Africa, Vol. 21, No. 1, 19-38 . |Platzky, L. 1985. The surplus people: forced removals in South Africa. Johannesburg: Ravan Press |Rand Daily Mail, 7 November 1975; in Platzky, L. 1985.The surplus people: forced removals in South Africa. Johannesburg:Ravan Press. |Serino, K. 2015. Gentrification in Johannesburg isn’t good news for everyone. Al Jazeera America, http://america.aljazeera.com/multimedia/2015/3/Gentrification-in-Johannesburg.html [Accessed 21 April 2016]. |South Africa: Overcoming Apartheid. 2016. . [ONLINE] Available at: http://overcomingapartheid.msu.edu/multimedia.php?id=65-259-6. [Accessed 22 April 2016]. |Statutes of the Union of South Africa, 1950, Act no. 41 of 1950. |Thomas, A. 2001 “It changed everybody’s lives: the Simon’s Town Group Areas Removals” in Field, S. 2002.Lost Communities, Living Memories: Remembering Forced Removals in Cape Town. 1st Edition. Cape Town:David Philip Publishers. p96 |Turok, I. 2001. Persistent Polarisation Post-Apartheid?Progress towards Urban Integration in Cape Town. Urban Studies, [Online]. 38, 13, 2349–2377. Available at: http://usj.sagepub.com.ezproxy.uct.ac.za/content/38/13/2349.short [Accessed 25 April 2016]. |Western, in Platzky, L. 1985.The surplus people: forced removals in South Africa. Johannesburg: Ravan Press.

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

- DOI: 10.1080/03057079208708320

- Corpus ID: 145512406

Comprehensive Segregation: The Origins of the Group Areas Act and Its Planning Apparatuses

- Published 1 June 1992

- Journal of Southern African Studies

147 Citations

Apartheid, urban segregation, and the local state: durban and the group areas act in south africa, rethinking urban south africa, deviances and the construction of a 'healthy nation' in south africa :, re-building amongst ruins : the pursuit of urban integration in south africa (1994-2001), the cambridge history of south africa: south african society and culture, 1910–1948, the politics of difference and the forging of a political ‘community’: discourses and practices of the charterist civic movement in the vaal triangle, south africa, 1980–84 *, a discourse of modernity: the social and economic planning council's fifth report on regional and town planning, 1944, urban peace building in divided societies, the apartheid project, 1948–1970, planning as a principle of vision and division: a bourdieusian view of tel aviv's urban development, 1920s—1950s, 21 references, race class and the apartheid state, apartheid planning in south africa: the case of port elizabeth, “progressive port elizabeth”: liberal politics, local economic development and the territorial basis of racial domination, 1923–1935, race zoning in south africa: board, court, parliament, public, the meaning of apartheid before 1948: conflicting interests and forces within the afrikaner nationalist alliance, racial segregation in johannesburg, problems of planning for urbanization and development in south africa: the case of natal's coastal margins, the rise and decline of urban apartheid in south africa, outcast cape town, social conflicts over african education in south africa from the 1940's to 1976, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

- Archival descriptions

- Authority records

- Archival institutions

- Digital objects

- Clear all selections

- Go to clipboard

- Load clipboard

- Save clipboard

Quick links

- Privacy Policy

Have an account?

- Quick search

- Fonds A1485 - Group Areas Act (Act No. 41 of 1950) Records

Fonds A1485 - Group Areas Act (Act No. 41 of 1950) Records

Identity area, reference code.

- 1950 - 1962 (Creation)

Level of description

Extent and medium.

Extent1 box

Context area

Archival history, immediate source of acquisition or transfer, content and structure area, scope and content.

Records on the effects of the Act on the Indian community.

The collection includes the following:

- Administration of the Act, including a copy of the Act and guidelines for its administration

- Agenda book of the 20th session of the South African Indian Congress Conference, Johannesburg, 25-27 January 1952

- Memoranda, Flyers and appeals on the Group Areas Act

- Draft resolutions and papers presented to the Conference on the Group Areas Act convened by the Natal Indian Congress, Durban, 5-6 May 1956

- Agenda book and papers presented to the All-in Group Areas Conference of the Transvaal Indian Congress, 25-26 August 1956

- Press clippings 1953-1962

Appraisal, destruction and scheduling

System of arrangement, conditions of access and use area, conditions governing access, conditions governing reproduction, language of material, script of material, language and script notes, physical characteristics and technical requirements, finding aids, allied materials area, existence and location of originals, existence and location of copies, related units of description, related descriptions, alternative identifier(s), access points, subject access points, place access points, name access points, genre access points, description control area, description identifier, institution identifier, rules and/or conventions used, level of detail, dates of creation revision deletion, language(s), accession area.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Apartheid legislation

- Opposition to apartheid

- The end of legislated apartheid

What is apartheid?

When did apartheid start, how did apartheid end, what is the apartheid era in south african history.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Khan Academy - Apartheid

- Academia - A Social History of the University Presses in Apartheid South Africa

- Gresham College - The Gospel of Apartheid

- Stanford University - The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute - Apartheid

- South African History Online - Apartheid and Reactions to It

- BlackPast - Apartheid

- Al Jazeera - South Africa: 30 years after apartheid, what has changed?

- GlobalSecurity.org - South Africa - Apartheid

- The Library of Economics and Liberty - Apartheid

- apartheid - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- apartheid - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Apartheid ( Afrikaans : “apartness”) is the name of the policy that governed relations between the white minority and the nonwhite majority of South Africa during the 20th century. Although racial segregation had long been in practice there, the apartheid name was first used about 1948 to describe the racial segregation policies embraced by the white minority government. Apartheid dictated where South Africans, on the basis of their race, could live and work, the type of education they could receive, and whether they could vote. Events in the early 1990s marked the end of legislated apartheid, but the social and economic effects remained deeply entrenched.

Racial segregation had long existed in white minority-governed South Africa , but the practice was extended under the government led by the National Party (1948–94), and the party named its racial segregation policies apartheid ( Afrikaans : “apartness”). The Population Registration Act of 1950 classified South Africans as Bantu (black Africans), Coloured (those of mixed race), or white; an Asian (Indian and Pakistani) category was later added. Other apartheid acts dictated where South Africans, on the basis of their racial classification, could live and work, the type of education they could receive, whether they could vote, who they could associate with, and which segregated public facilities they could use.

Under the administration of the South African president F.W. de Klerk , legislation supporting apartheid was repealed in the early 1990s, and a new constitution—one that enfranchised blacks and other racial groups—was adopted in 1993. All-race national elections held in 1994 resulted in a black majority government led by prominent anti-apartheid activist Nelson Mandela of the African National Congress party. Although these developments marked the end of legislated apartheid, the social and economic effects of apartheid remained deeply entrenched in South African society.

The apartheid era in South African history refers to the time that the National Party led the country’s white minority government, from 1948 to 1994. Apartheid ( Afrikaans : “apartness”) was the name that the party gave to its racial segregation policies, which built upon the country’s history of racial segregation between the ruling white minority and the nonwhite majority. During this time, apartheid policy determined where South Africans, on the basis of their race, could live and work, the type of education they could receive, whether they could vote, who they could associate with, and which segregated public facilities they could use.

Recent News

Trusted Britannica articles, summarized using artificial intelligence, to provide a quicker and simpler reading experience. This is a beta feature. Please verify important information in our full article.

This summary was created from our Britannica article using AI. Please verify important information in our full article.

apartheid , policy that governed relations between South Africa ’s white minority and nonwhite majority for much of the latter half of the 20th century, sanctioning racial segregation and political and economic discrimination against nonwhites. Although the legislation that formed the foundation of apartheid had been repealed by the early 1990s, the social and economic repercussions of the discriminatory policy persisted into the 21st century.

(Read Desmond Tutu’s Britannica entry on the apartheid commission.)