Semi-structured Interviews

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 13 July 2018

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Danielle Magaldi 3 &

- Matthew Berler 4

2191 Accesses

6 Citations

Open-ended interview ; Qualitative interview ; Systematic exploratory interview ; Thematic interview

The semi-structured interview is an exploratory interview used most often in the social sciences for qualitative research purposes or to gather clinical data. While it generally follows a guide or protocol that is devised prior to the interview and is focused on a core topic to provide a general structure, the semi-structured interview also allows for discovery, with space to follow topical trajectories as the conversation unfolds.

Introduction

Qualitative interviews exist on a continuum, ranging from free-ranging, exploratory discussions to highly structured interviews. On one end is unstructured interviewing, deployed by approaches such as ethnography, grounded theory, and phenomenology. This style of interview involves a changing protocol that evolves based on participants’ responses and will differ from one participant to the next. On the other end of the continuum...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Baumbusch, J. (2010). Semi-structured interviewing in practice-close research. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing; Hoboken, 15 (3), 255–258.

Article Google Scholar

Clarkin, A. J., Ammaniti, M., & Fontana, A. (2015). The use of a psychodynamic semi-structured personality assessment interview in school settings. Adolescent Psychiatry, 5 (4), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.2174/2210676606666160502125435 .

Cooper, Z., & Fairburn, C. (1987). The Eating Disorder Examination: A semi-structured interview for the assessment of the specific psychopathology of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6 (1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198701)6:1<1::AID-EAT2260060102>3.0.CO;2-9 .

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Google Scholar

Dearnley, C. (2005). A reflection on the use of semi-structured interviews. Nurse Researcher, 13 (1), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2005.07.13.1.19.c5997 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

DiCicco-Bloom, B., & Crabtree, B. F. (2006). The qualitative research interview. Medical Education, 40 (4), 314–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x .

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38 (3), 215–229.

Fylan, F. (2005). Semi-structured interviewing. In A handbook of research methods for clinical and health psychology (pp. 65–77). New York: Oxford University Press.

Galanter, C. A., & Patel, V. L. (2005). Medical decision making: A selective review for child psychiatrists and psychologists. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46 (7), 675–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01452.x .

Galletta, A. (2013). Mastering the semi-structured interview and beyond: From research design to analysis and publication . New York: New York University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Gibbs, L., Kealy, M., Willis, K., Green, J., Welch, N., & Daly, J. (2007). What have sampling and data collection got to do with good qualitative research? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 31 (6), 291–295. https://doi.org/10.1028/bdj.2008.192 .

Glenn, C. R., Weinberg, A., & Klonsky, E. D. (2009). Relationship of the Borderline Symptom List to DSM-IV borderline personality disorder criteria assessed by semi-structured interview. Psychopathology; Basel, 42 (6), 394–398.

Haverkamp, B. E. (2005). Ethical perspectives on qualitative research in applied psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52 (2), 146.

Hill, C., Knox, S., Thompson, B., Williams, E., Hess, S., & Ladany, N. (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology . Retrieved from http://epublications.marquette.edu/edu_fac/18

Hutsebaut, J., Kamphuis, J. H., Feenstra, D. J., Weekers, L. C., & De Saeger, H. (2017). Assessing DSM–5-oriented level of personality functioning: Development and psychometric evaluation of the Semi-Structured Interview for Personality Functioning DSM–5 (STiP-5.1). Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 8 (1), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000197 .

Kallio, H., Pietilä, A., Johnson, M., & Kangasniemi, M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72 (12), 2954–2965. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13031 .

Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Brent, D., Rao, U., Flynn, C., Moreci, P., … Ryan, N. (1997). Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36 (7), 980–988. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021 .

Knox, S., & Burkard, A. W. (2014). Qualitative research interviews: An update. In W. Lutz, S. Knox, W. Lutz, & S. Knox (Eds.), Quantitative and qualitative methods in psychotherapy research (pp. 342–354). New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Kraus, S. E., Hamzah, A., Omar, Z., Suandi, T., Ismail, I. A., & Zahari, M. Z. (2009). Preliminary investigation and interview guide development for studying how Malaysian farmers form their mental models of farming. The Qualitative Report, 14 (2), 245–260.

McTate, E. A., & Leffler, J. M. (2017). Diagnosing disruptive mood dysregulation disorder: Integrating semi-structured and unstructured interviews. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 22 (2), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104516658190 .

Pierucci-Lagha, A., Gelernter, J., Chan, G., Arias, A., Cubells, J. F., Farrer, L., & Kranzler, H. R. (2007). Reliability of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria using the semi-structured assessment for drug dependence and alcoholism (SSADDA). Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 91 (1), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.014 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2010a). Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice . Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Polit, D. S., & Beck, C. T. (2010b). Essentials of nursing research. Appraising evidence for nursing practice (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers.

Ramos-Quiroga, J. A., Nasillo, V., Richarte, V., Corrales, M., Palma, F., Ibáñez, P., … Kooij, J. J. S. (2016). Criteria and concurrent validity of DIVA 2.0: A semi-structured diagnostic interview for adult ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders . https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716646451 .

Rennie, D. L. (2004). Reflexivity and person-centered counseling. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 44 , 182–203.

Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (2005). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Ryan, A. B. (2006). Post-positivist approaches to research. In Researching and writing your thesis: A guide for postgraduate students (pp. 12–26). Ireland: MACE: Maynooth Adult and Community Education.

Turner, D. W. (2010). Qualitative interview design: A practical guide for novice researcher. The Qualitative Report, 15 (3), 754–760.

Whiting, L. S. (2008). Semi-structured interviews: Guidance for novice researchers. Nursing Standard, 22 (23), 35–40.

Williams, E. N., & Morrow, S. L. (2009). Achieving trustworthiness in qualitative research: A pan-paradigmatic perspective. Psychotherapy Research, 19 (4–5), 576–582.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

City University of New York, Lehman College, New York City, NY, USA

Danielle Magaldi

Pace University, New York City, NY, USA

Matthew Berler

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Danielle Magaldi .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Oakland University, Rochester, USA

Virgil Zeigler-Hill

Todd K. Shackelford

Section Editor information

Department of Educational Sciences, University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy

Patrizia Velotti

Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Magaldi, D., Berler, M. (2018). Semi-structured Interviews. In: Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T. (eds) Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_857-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_857-1

Received : 10 August 2017

Accepted : 18 December 2017

Published : 13 July 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-28099-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-28099-8

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- What is a semi-structured interview?

Last updated

5 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

When designed correctly, user interviews go much deeper than surface-level survey responses. They can provide new information about how people interact with your products and services, and shed light on the underlying reasons behind these habits.

Semi-structured user interviews are widely considered one of the most effective tools for doing this kind of qualitative research , depending on your specific goals. As the name suggests, the semi-structured format allows for a more natural, conversational flow, while still being organized enough to collect plenty of actionable data .

Analyze semi-structured interviews

Bring all your semi-structured interviews into one place to analyze and understand

A semi-structured interview is a qualitative research method used to gain an in-depth understanding of the respondent's feelings and beliefs on specific topics. As the interviewer prepares the questions ahead of time, they can adjust the order, skip any that are redundant, or create new ones. Additionally, the interviewer should be prepared to ask follow-up questions and probe for more detail.

Semi-structured interviews typically last between 30 and 60 minutes and are usually conducted either in person or via a video call. Ideally, the interviewer can observe the participant's verbal and non-verbal cues in real-time, allowing them to adjust their approach accordingly. The interviewer aims for a conversational flow that helps the participant talk openly while still focusing on the primary topics being researched.

Once the interview is over, the researcher analyzes the data in detail to draw meaningful results. This involves sorting the data into categories and looking for patterns and trends. This semi-structured interview approach provides an ideal framework for obtaining open-ended data and insights.

- When to use a semi-structured interview?

Semi-structured interviews are considered the "best of both worlds" as they tap into the strengths of structured and unstructured methods. Researchers can gather reliable data while also getting unexpected insights from in-depth user feedback.

Semi-structured interviews can be useful during any stage of the UX product-development process, including exploratory research to better understand a new market or service. Further down the line, this approach is ideal for refining existing designs and discovering areas for improvement. Semi-structured interviews can even be the first step when planning future research projects using another method of data collection.

- Advantages of semi-structured interviews

Flexibility

This style of interview is meant to be adapted according to the answers and reactions of the respondent, which gives a lot of flexibility. Semi-structured interviews encourage two-way communication, allowing themes and ideas to emerge organically.

Respondent comfort

The semi-structured format feels more natural and casual for participants than a formal interview. This can help to build rapport and more meaningful dialogue.

Semi-structured interviews are excellent for user experience research because they provide rich, qualitative data about how people really experience your products and services.

Open-ended questions allow the respondent to provide nuanced answers, with the potential for more valuable insights than other forms of data collection, like structured interviews , surveys , or questionnaires.

- Disadvantages of semi-structured interviews

Can be unpredictable

Less structure brings less control, especially if the respondent goes off tangent or doesn't provide useful information. If the conversation derails, it can take a lot of effort to bring the focus back to the relevant topics.

Lack of standardization

Every semi-structured interview is unique, including potentially different questions, so the responses collected are very subjective. This can make it difficult to draw meaningful conclusions from the data unless your team invests the time in a comprehensive analysis.

Compared to other research methods, unstructured interviews are not as consistent or "ready to use."

- Best practices when preparing for a semi-structured interview

While semi-structured interviews provide a lot of flexibility, they still require thoughtful planning. Maximizing the potential of this research method will depend on having clear goals that help you narrow the focus of the interviews and keep each session on track.

After taking the time to specify these parameters, create an interview guide to serve as a framework for each conversation. This involves crafting a range of questions that can explore the necessary themes and steer the conversation in the right direction. Everything in your interview guide is optional (that's the beauty of being "semi" structured), but it's still an essential tool to help the conversation flow and collect useful data.

Best practices to consider while designing your interview questions include:

Prioritize open-ended questions

Promote a more interactive, meaningful dialogue by avoiding questions that can be answered with a simple yes or no, otherwise known as close-ended questions.

Stick with "what," "when," "who," "where," "why," and "how" questions, which allow the participant to go beyond the superficial to express their ideas and opinions. This approach also helps avoid jargon and needless complexity in your questions.

Open-ended questions help the interviewer uncover richer, qualitative details, which they can build on to get even more valuable insights.

Plan some follow-up questions

When preparing questions for the interview guide, consider the responses you're likely to get and pair them up with some effective, relevant follow-up questions. Factual questions should be followed by ones that ask an opinion.

Planning potential follow-up questions will help you to get the most out of a semi-structured interview. They allow you to delve deeper into the participant's responses or hone in on the most important themes of your research focus.

Follow-up questions are also invaluable when the interviewer feels stuck and needs a meaningful prompt to continue the conversation.

Avoid leading questions

Leading questions are framed toward a predetermined answer. This makes them likely to result in data that is biased, inaccurate, or otherwise unreliable.

For example, asking "Why do you think our services are a good solution?" or "How satisfied have you been with our services?" will leave the interviewee feeling pressured to agree with some baseline assumptions.

Interviewers must take the time to evaluate their questions and make a conscious effort to remove any potential bias that could get in the way of authentic feedback.

Asking neutral questions is key to encouraging honest responses in a semi-structured interview. For example, "What do you consider to be the advantages of using our services?" or simply "What has been your experience with using our services?"

Neutral questions are effective in capturing a broader range of opinions than closed questions, which is ultimately one of the biggest benefits of using semi-structured interviews for research.

Use the critical incident method

The critical incident method is an approach to interviewing that focuses on the past behavior of respondents, as opposed to hypothetical scenarios. One of the challenges of all interview research methods is that people are not great at accurately recalling past experiences, or answering future-facing, abstract questions.

The critical incident method helps avoid these limitations by asking participants to recall extreme situations or 'critical incidents' which stand out in their memory as either particularly positive or negative. Extreme situations are more vivid so they can be recalled more accurately, potentially providing more meaningful insights into the interviewee’s experience with your products or services.

- Best practices while conducting semi-structured interviews

Encouraging interaction is the key to collecting more specific data than is typically possible during a formal interview. Facilitating an effective semi-structured interview is a balancing act between asking prepared questions and creating the space for organic conversation. Here are some guidelines for striking the right tone.

Beginning the interview

Make participants feel comfortable by introducing yourself and your role at the organization and displaying appropriate body language.

Outline the purpose of the interview to give them an idea of what to expect. For example, explain that you want to learn more about how people use your product or service.

It's also important to thank them for their time in advance and emphasize there are no right or wrong answers.

Practice active listening

Build trust and rapport throughout the interview with active listening techniques, focusing on being present and demonstrating that you're paying attention by responding thoughtfully. Engage with the participant by making eye contact, nodding, and giving verbal cues like "Okay, I see," "I understand," and "M-hm."

Avoid the temptation to rush to fill any silences while they're in the middle of responding, even if it feels awkward. Give them time to finish their train of thought before interrupting with feedback or another prompt. Embracing these silences is essential for active listening because it's a sign of a productive interview with meaningful, candid responses.

Practicing these techniques will ensure the respondent feels heard and respected, which is critical for gathering high-quality information.

Ask clarifying questions in real time

In a semi-structured interview, the researcher should always be on the lookout for opportunities to probe into the participant's thoughts and opinions.

Along with preparing follow-up questions, get in the habit of asking clarifying questions whenever possible. Clarifying questions are especially important for user interviews because people often provide vague responses when discussing how they interact with products and services.

Being asked to go deeper will encourage them to give more detail and show them you’re taking their opinions seriously and are genuinely interested in understanding their experiences.

Some clarifying questions that can be asked in real-time include:

"That's interesting. Could you give me some examples of X?"

"What do you mean when you say "X"?"

"Why is that?"

"It sounds like you're saying [rephrase their response], is that correct?"

Minimize note-taking

In a wide-ranging conversation, it's easy to miss out on potentially valuable insights by not staying focused on the user. This is why semi-structured interviews are generally recorded (audio or video), and it's common to have a second researcher present to take notes.

The person conducting the interview should avoid taking notes because it's a distraction from:

Keeping track of the conversation

Engaging with the user

Asking thought-provoking questions

Watching you take notes can also have the unintended effect of making the participant feel pressured to give shallower, shorter responses—the opposite of what you want.

Concluding the interview

Semi-structured interviews don't come with a set number of questions, so it can be tricky to bring them to an end. Give the participant a sense of closure by asking whether they have anything to add before wrapping up, or if they want to ask you any questions, and then give sincere thanks for providing honest feedback.

Don't stop abruptly once all the relevant topics have been discussed or you're nearing the end of the time that was set aside. Make them feel appreciated!

- Analyzing the data from semi-structured interviews

In some ways, the real work of semi-structured interviews begins after all the conversations are over, and it's time to analyze the data you've collected. This process will focus on sorting and coding each interview to identify patterns, often using a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods.

Some of the strategies for making sense of semi-structured interviews include:

Thematic analysis : focuses on the content of the interviews and identifying common themes

Discourse analysis : looks at how people express feelings about themes such as those involving politics, culture, and power

Qualitative data mapping: a visual way to map out the correlations between different elements of the data

Narrative analysis : uses stories and language to unlock perspectives on an issue

Grounded theory : can be applied when there is no existing theory that could explain a new phenomenon

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 13 April 2023

Last updated: 14 February 2024

Last updated: 27 January 2024

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 8 February 2023

Last updated: 23 January 2024

Last updated: 30 January 2024

Last updated: 7 February 2023

Last updated: 7 March 2023

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

- Open access

- Published: 23 May 2024

Older people’s perception of being frail – a qualitative exploration

- Abigail J. Hall 1 ,

- Silviya Nikolova 2 ,

- Matthew Prescott 3 &

- Victoria A. Goodwin 1

BMC Geriatrics volume 24 , Article number: 453 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

150 Accesses

Metrics details

Frailty is a suggested consequence of ageing, but with a variety of different definitions the understanding of what it means to be frail is challenging. There is a common belief that frailty results in a reduction of physical functioning and ability and therefore is likely to significantly affect a person’s quality of life. The aim of this study was to explore the understanding of older people about the meaning of frailty and the potential consequences of being classified as frail.

This paper forms a secondary analysis of a process evaluation of a complex intervention that was embedded within the individually randomised Home-based Extended Rehabilitation of Older people (HERO) trial. A maximum variation, purposive sampling strategy sought to recruit participants with a wide range of characteristics. Data collection included observations of the delivery of the intervention, documentary analysis and semi-structured interviews with participants. Thematic analysis was used to make sense of the observational and interview data, adopting both inductive and deductive approaches.

Ninety three HERO trial participants were sampled for the process evaluation with a total of 60 observational home visits and 35 interviews were undertaken. There was a wide range in perceptions about what it meant to be classified as frail with no clear understanding from our participants. However, there was a negative attitude towards frailty with it being considered something that needed to be avoided where possible. Frailty was seen as part of a negative decline that people struggled to associate with. There was discussion about frailty being temporary and that it could be reduced or avoided with sufficient physical exercise and activity.

Our study provides insight into how older people perceive and understand the concept of frailty. Frailty is a concept that is difficult for patients to understand, with most associating the term with an extreme degree of physical and cognitive decline. Having a label of being “frail” was deemed to be negative and something to be avoided, suggesting the term needs to be used cautiously.

Trial registration

ISRCTN 13927531. Registered on April 19, 2017.

Peer Review reports

Frailty is a clinical condition suggested to be an inevitable consequence of ageing [ 1 ] and despite no universally accepted definition, there is consensus that it involves susceptibility to external stressors such as physical, psychological and social factors [ 2 ], alongside a loss of biological reserve [ 3 ]. As such, even minor stressors can result in significant changes in health status [ 4 ]. A global ageing population, with an expected 2 billion of the world’s population predicted to be over 60 years of age by 2050 [ 5 ], will only exacerbate the challenges of conditions, such as frailty, with an increased prevalence in older populations. Therefore, understanding the challenges and consequences of frailty could be considered vital to improve healthy ageing and health and social care outcomes at an individual and societal level.

The multifaceted concept of frailty emphasises impacts on a person’s physical and psychological health and therefore the potential influence this has on social functioning – which are all factors reported to affect a person’s quality of life (QoL). Indeed, those living with frailty themselves have highlighted the importance in maintaining QoL rather than a focus on biomedical measures of outcomes relating to disease [ 6 ]. Therefore, the importance of understanding a person’s perception of their level of frailty and their resultant QoL is vital to understand how to target interventions to manage frailty alongside the medical management.

Existing literature focuses on older adults’ perceptions of frailty rather than the perceptions of those who are classified as being frail [ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ] as well as the difference between actually “being” frail and “feeling” frail [ 12 ]. There is a plethora of qualitative literature exploring perceptions of ageing in general, but with little focus specifically on frailty [ 13 ]. Similarly, there is literature exploring the perceptions of frailty from healthcare professionals [ 14 , 15 ].

This paper forms a secondary analysis of a process evaluation (PE) of a complex intervention that was embedded within the Home-based Extended Rehabilitation of Older people (HERO) randomised controlled trial involving 742 participants living with frailty following a hospital admission for an acute illness or injury [ 16 ]. The process evaluation explored the community delivery of a complex intervention and involved a variety of different interacting components. This individualised, graded, and progressive 24-week exercise programme was delivered by National Health Service (NHS) physiotherapy teams to people aged 65 and older living with frailty. Frailty as an inclusion criteria for the HERO trial was identified using the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) [ 17 ] following discharge from hospital (+/- rehabilitation) after an acute illness or injury. The intervention incorporated behaviour change techniques based on social cognitive theory, including providing information on benefits of exercise; setting graded tasks; goal setting, problem solving, reorganising the physical environment to facilitate exercise, encouragement, feedback, prompting self-monitoring and rewards.

Evidence from the HERO trial suggests that there is incongruity between older people “being frail” and “feeling frail” [ 9 , 12 ], and that feeling frail can have a large detrimental effect on the person’s wellbeing [ 18 ]. Thus, the person’s perception of their level of frailty has the potential to directly impact on their physical and psychological wellbeing. The aim of this paper was to explore the perceptions of frailty for those who were assessed to be frail. It will also consider how these perceptions of frailty affect an individual’s everyday functioning and QoL.

The qualitative PE for the HERO trial employed a qualitative mixed methods approach [ 19 ] including a variety of data collection methods such as non-participant observations, semi-structured interviews, and documentary analysis. The data for this paper was obtained from the interviews with participants as the focus is on individual’s own perception of their frailty. Carers were often present at these interviews but contributed little to the data and the non-participant observations which allowed the researcher to observe the delivery of the intervention.

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [ 18 ] was used to explore the intervention and perceptions of frailty from the perspective of the participant and guided the development of the topic guides and subsequent analysis. SCT is extensively used in health and social care research and explains how individuals within social systems enact multiple human processes, including the acquisition and adoption of information and knowledge. Its focus was the interplay between personal factors, their behaviour, and their environments. The COREQ checklist [ 20 ] was used to report the study.

Research ethics committee approval was obtained from the Health Research Authority Yorkshire & The Humber – Bradford Leeds Research Ethics Committee – reference 17/YH/0097. All participants gave written informed consent to take part in the study.

Recruitment

Inclusion criteria.

HERO trial inclusion criteria are detailed in the trial protocol [ 16 ], but broadly included individuals who were:

Age ≥ 65 years of age

Community dwelling

Acutely admitted to hospital with acute illness or injury then discharged home from hospital or associated rehabilitation

Classified as mild, moderate, or severe frailty, defined as a score of 5–7 on the 9-item (CFS)

Able to complete the Timed Up and Go test independently (i.e. stand from a chair and three meters before turning to return and sit in the chair)

HERO trial participants were asked to optionally consent to the trial PE. Those people consenting to PE activity were then purposively sampled to ensure all types of data collection included participants with a wide variety of experiences, demographics, and contexts to represent a wider perspective of the population under study. The researchers had no prior relationship with the participants. Participants were aware of the purpose of the research and the aims of the interviews. Participants were contacted via letter to request their involvement in the interviews. A maximum variation, purposive sampling strategy was used for the following characteristics:

levels of frailty (Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) levels 5–7)

level of intervention (Home-based Older People’s Exercise (HOPE) programme levels 1–3)

intervention delivery site (NHS trust)

Recruitment to the process evaluation continued until it was felt no new themes were emerging and thus, we had sufficient information power [ 21 ] to answer our overall research questions and objectives.

HERO trial participants consenting to PE activity and randomised to receive the trial intervention were sampled and approached to participate in intervention delivery. These observations were scheduled to observe a variety of different participants at various stages of the intervention (from the first face to face home visit to the final face to face visit). While trial participants sampled for the PE had already consented to their involvement, permission to observe a therapy session was sought ahead of every observation from both the therapist and the participant.

Participant and carer interviews included trial participants in both the intervention and usual care arms of the trial. These interviews were scheduled approximately six months after an individual entered the HERO trial, and were timed to correspond with the intervention finishing for those randomised to receive it. Due to the lapse of time between consenting to participate in the HERO trial, and the scheduling of the process evaluation interviews, additional process evaluation participant information was provided and participants were asked to confirm consent prior to interview. Sampled participants were approached via a letter of invitation which was then followed up by a telephone call to discuss their potential involvement in a face-to-face interview. The interviews were all conducted in the participant’s own home and lasted for an average of 60 min. Two of the sampled participants refused an interview at this point – both reporting that they were unwell. Several of the participants we interviewed had carers or relatives present for the interview – the majority did not contribute to the interview and simply listened to the conversation.

Data collection

Topic guides were developed by the research team and used when undertaking interviews and used SCT to structure the lines of enquiry. All questions on the topic guide were used in every interview to ensure breadth of discussion. The two interviewers (AH and FZ) were both post-doctoral academics with extensive experience of qualitative research, including multiple publications and have both undertaken extensive training in qualitative research. The topic guides were developed to ensure that interviewees’ experiences were explored in relation to the underpinning theory relating to behaviour change. The topic guides were developed to explore many components of the intervention, but there were specific questions which related to frailty and the participants’ perception of what this meant to them. The topic guide and questions were initially piloted with several participants and after making small typographic changes, were then used for all other participants. Interviews were audio recorded, encrypted and later transcribed. Field notes were taken where appropriate. At the end of the interview, the participant was asked if they were happy for all their data to be included in the analysis. All data were pseudo-anonymised, and unique identification numbers associated with participants removed. All data were stored electronically on password protected secure servers. In order to ensure that each non-participation observation was explored consistently, a checklist and template was developed. This included observations of the delivery of the intervention, the environment as well as the interaction and relationship between the therapist(s) and the participant and carers.

Types of data collected

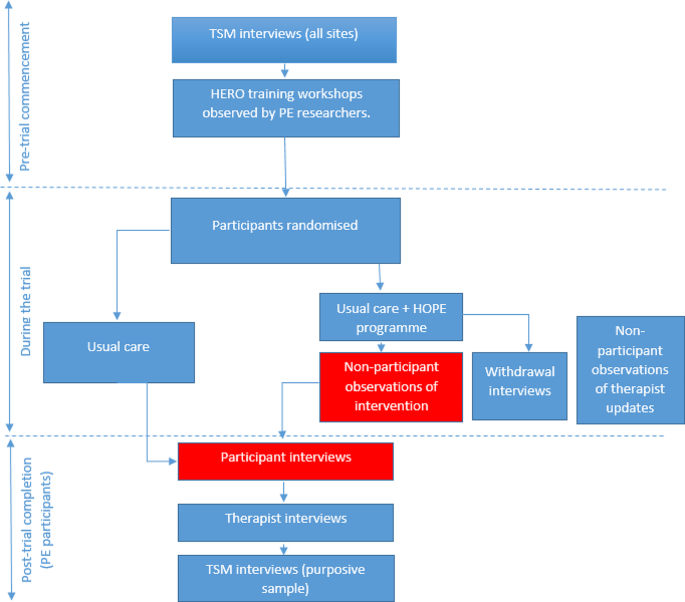

Figure 1 depicts the data that were collected for the whole of the process evaluation, with the red boxes demonstrating the sources of data for this study. Data were collected as per the description in the trial protocol [ 16 ].

HERO trial Process evaluation activities (PE = process evaluation, TSM = therapy service manager, HOPE programme = The Home-based Older People’s Exercise programme)

An approach based on thematic analysis [ 22 ] was used to interpret the observational and interview data, adopting both inductive and deductive approaches. The first stage of data analysis involved the two researchers (AH and FZ) collecting the raw data from interview transcripts, field notes and patient observations. NVivo 11 (QSR International) was used to organise and store the data with all transcripts, observational frameworks and field notes uploaded to the software. Following completion of data collection, a first stage of coding was undertaken independently by each researcher. This resulted in preliminary codes for each set of participant data being generated and was reviewed jointly by the researchers and discussed with a third reviewer (DJC). This was part of a process of consensus building around the generation of themes. The themes that were being developed were continually reviewed in the context of the intervention logic model and used to develop a framework. Data were triangulated from all data sources to gain a clear understanding about any conflicting themes – for example, the observational data was compared to the data from the interviews and therapy record to determine if there was any conflicting data in what was observed and what was reported.

In total, 93 HERO trial participants were sampled for the process evaluation, and their characteristics are detailed in Table 1 . 38 intervention participants had their intervention delivery observed with a total of 60 observational home visits (the majority of participants had two observations) and 35 interviews were undertaken.

One of the main criteria for inclusion in the HERO trial was an individual being classified as frail, however the main trial did not specifically inform people that they had been classified as ‘frail’ or discuss the CFS classification in such terms. As part of the PE data collection, we sought to determine general attitudes towards frailty as a term and concept, and determine whether those interviewed considered themselves as being frail. While some participants realised that they could be characterised as being frail and saw it as an inevitable consequence of ageing, others disputed it, feeling that it was a negative characteristic they didn’t wish to be associated with. There was also a feeling that frailty was a state that could fluctuate, it was a fluid state that could improve or worsen. Some participants felt they could control their level of frailty, others felt overwhelmed by it and daunted by the prospect of becoming frailer.

Perception of frailty

Despite all our older main trial participants being classified as frail, there were very different attitudes towards frailty and perceptions of what being frail meant to them and to others. When asked to define what they understood “frail” to mean, the vast majority related frailty to a person’s physical abilities, thus if they felt they were physically able they would not perceive themselves to be frail.

Others related frailty to an image of what a frail individual might look like, often describing the image to be a thin, “fragile”, person who might look malnourished and be described to be “cognitively poor”. None of our participants described themselves as looking frail, indeed frailty wasn’t a concept that most found easy to identify with.

While participants often related frailty to physical difficulties, there was a belief expressed by a few of our participants that cognitive deficits (or lack of) contributed to their perception of frailty. Often, where an interviewee had some physically difficulties, if they perceived themselves to be cognitively sound, they didn’t feel they were frail – thus for some there is an element of needing both physical and cognitive deficits in determining whether somebody feels frail.

Your abilities. Things that you can’t do that you used to do. I’m not frail in my mind….But when you know the things that, up to possibly a year ago, you could do and suddenly you’re unable to do them, and I had a dramatic weight loss. I mean, I’ve lost three stone. – (156, mild frailty)

Pre-existing disabilities appeared to play a role in considering whether somebody was frail or not. Functional limitations relating to long standing disability were seen as separate when considering frailty, and thus did not predispose a person to being considered frail.

While some participants reported that their carers or family supported them to do functional tasks to aid building confidence, others were cautious about doing so and were fearful that enabling the person in this way may lead to over-confidence, which could pose a risk to their safety.

There was a common belief that frailty related to a limitation in being able to do the tasks or activities that they wanted to be able to do. These tasks varied from simple activities of daily living that had become harder to more vigorous activities such as running. This inability to undertake a task provided very clear evidence that a person was physically deteriorating and often people related to a reduction in QoL and thus to an onset of frailty.

You know when you want to run and you can’t run, and I think, I’m getting very frail now. (283 moderate frailty) Just not being able to do things. Not being able to get on the bus and go to the supermarket, and being tired halfway around, and falling asleep all the time, I fall asleep through the day, I’ve… I’ll be watching something or doing something and my eyes just go, and I’m asleep for about an hour, which is a long time, and then when I go to bed I’m wide awake. – (18 mild frailty)

Challenges undertaking functional tasks led people to seeking or accepting help. While some people felt that this inability to undertake functional activities classified them as being frail, others simply found the challenges associated with it frustrating, but didn’t feel this classified them as frail.

Yes, well I mean I have needed help, I’ve got things that help in your kitchen and things like that, you know, to do different jobs that you can’t do anymore, you know, there’s certain things I can’t do, like even the things like the bleach bottles, you know where they have those locks on, I’m up a gum tree with them, I can’t press and do, my hands just aren’t doing it, so but I don’t think, I’ve never thought of that as frail, I just thought of that as a blooming nuisance, I have to get [son] to come, or somebody to come and do it you see (368 moderate frailty)

Identifying as ’frail’ was problematic for many of our participants, however, there was evidence to suggest that their relatives and carers often told them that they were frail – frequently relating this to things that they were unable to do.

P : He’s always saying “I can’t do this, I can’t do that”. (283 moderate frailty)

Despite our participants all being classified as being “frail”, none of them overtly recognised themselves as being frail.

Denial / avoidance

Our data indicated multiple negative connotations towards the term “frailty”. It was something that people perceived to be a negative characteristic and was something that they wanted to avoid, despite an acceptance that with increased age, came increased risk of frailty. The majority of participants we sampled in the process evaluation were classified as mild to moderately frail (CFS level 5 and 6), however, even the participants with severe frailty wished to avoid considering themselves as being frail.

I know I must be getting frailer but I try not to think about it to be quite honest. I think, well if I can still do it I can’t be that frail can I. And that’s what I say to myself you see, I can’t be so bad if I can still do it so I’m going to try. – (154, severe frailty)

There was an element of comparing themselves to other people who were less functionally able, and this appeared to give them comfort that they weren’t as frail as somebody else, or frail at all. If they knew people who were less physically able, this gave them confidence that they were doing well.

I don’t think that frailty is, as such is an issue, and you know, see elderly people who are much less able than I am. – (321 mild frailty) .

Participants related confidence to feelings of frailty. This confidence was important to enable them to undertake daily activities or things they enjoyed. Being unable to do these things was found to be associated with a reduction in QoL. Where they had lost confidence to undertake a task they previously could do, or participate in certain activities, they related this to a feeling of being frail. This loss of confidence was reported to have been as a result of injury or illness, or in some cases just as a result of general decline.

I suppose I did, but then it comes back to confidence, if you’re not confident in doing something, whether that is a sign of frailty I don’t know, - (321 mild frailty)

The participant often pointed out their cognitive abilities as a means to indicate they were not frail. The participant, in some cases, didn’t realise how many physical tasks they struggled to achieve until they were discussed and led them to reconsider whether they were indeed frail.

Many participants felt shame associated with classification of frailty and tried to mentally justify to themselves the reasons why they were not frail. It was perceived to be something to try and avoid as much as possible as it had significant negative connotations for a person’s QoL. The concept of QoL was raised by several participants and it was felt that frailty had a direct relationship with QoL – thus as a person got frailer, their QoL reduced.

Well they wouldn’t be able to do anything at all would they, that’s how I feel, if you’re so frail. I mean, life’s not worth living if you get that frail is it. – (154 severe frailty)

Reversibility

While participants frequently struggled to accept being classified as frail, they could often relate to feelings of frailty at different stages of their life and how these were temporary. Several participants reflected on a specific period of ill-health or an injury and a perception of frailty, but as a transient problem. During this time they accepted that their functional ability and QoL would temporarily reduce, but this would only be short lived. Thus, the transient nature of frailty meant that they felt they had a level of control over it.

I have been [frail] this last few months, because I’ve been in and out of the hospital, but normally I’m not a frail person, I’m not… (18 mild frailty)

Other participants, despite being classified as frail, did not feel that such events should result in a classification of frailty and the temporal nature of deterioration didn’t relate to being frail and to be classified as frail required a long period of time.

There was a general belief that there were positive actions that could be taken to reduce frailty which most commonly was reported to be the use of exercise. Within the intervention participants, perceived improvements in physical ability relating to undertaking the HOPE programme led some people to believe that their level of frailty was being reduced.

Um, well before I started doing the programme I felt really frail and then once I actually got into the programme itself I could feel meself getting stronger and stronger each time I were doing it and, but personally I really enjoyed doing it. – (235 mild frailty)

Where people engaged with exercise, they noted improvements in functional ability which allowed them to do more activities that they enjoyed and thus resulted in an improvement in their QoL. Examples given included being able to engage more with their grandchildren or going out to cafes with friends and families. While exercise was seen to reduce frailty, there was a common theme that participants wanted to delay the onset or progression of frailty as much as possible. The negative connotations that people described related to ‘frail older people’ invoked fear about a reduction in their QoL and functional abilities and was something they wanted to avoid for themselves, thus there was a difficulty accepting a classification of frailty.

Well I think when you can’t do what you used to do, I do think now, sometimes, I must admit sometimes I do feel a bit frail because I can’t do what I used to do … but it don’t go, but I do try. And I make meself go, I don’t sit and feel sorry for meself, I’ve never been that type, so I do try and make meself go as much as I can. – (33 mild frailty)

The aim of this paper was to explore the perception of frailty from those who are classified as being frail. It also considered how individuals’ perception of frailty, may affect their everyday functioning and QoL. Our participants were all recruited to a large randomised controlled trial, with inclusion requiring classification as frail (score of 5–7 on the 9-item (CFS) [ 17 ]. Thus all our trial participants had at least a degree of functional dependence due to physical or cognitive deficits, yet their perceptions of what it meant to be frail varied and the effect this had on their attitudes to their QoL and physical abilities was also inconsistent. Most participants sampled in the process evaluation were either mild or moderately frail, however, those that were severely frail appeared to have greatest disconnect from considering themselves frail than those with lesser levels of frailty. While being frail reduces the ability to undertake functional tasks, participants reported getting help to undertake activities which allowed them to maintain their QoL.

One of the main findings of our study was a noted disconnect that people felt between being classified as frail and identifying as frail. The majority did not realise that they were classified as frail and reasoned why they should not be. Unanimously, our participants described frailty as being a negative state from both a physical and a psychological aspect, which is consistent with existing literature [ 7 , 8 , 9 , 12 , 23 ]. However, most participants did not have a clear idea what it meant to be frail, but still felt it was something they wanted to avoid.

In their study, Warmoth and colleagues [ 9 ] reported that participants felt that their frailty was “beyond their control”, however, many of our participants felt that frailty was actually transient in its nature and there were measures that could be undertaken to reduce the likelihood of becoming frail or to reverse it. These mainly revolved around undertaking exercise, or from ensuring that they continue to do activities – regardless of how difficult they found them. It is conceivable that our trial participants allocated to receive the HOPE programme had positive experiences of exercise impacting upon their feelings of control relating to frailty levels. Indeed, out trial population were rather self-selecting in that they had volunteered to participate in an RCT involving an exercise programme as extended rehabilitation. One might assume therefore that the participants valued rehabilitation and exercise as a component there of. Literature supports the notion of reversible frailty. A systematic review [ 24 ] of 46 studies with an included 15,690 participants suggests that frailty is reversible with a combination of muscle strength training and protein supplementation. A further systematic review and network meta- analysis [ 25 ] including 66 RCTs concluded that physical activity interventions, when compared to placebo and standard care, were associated with reductions in frailty.

Despite our participants reporting that physical frailty was potentially reversible, there was a belief that cognitive frailty was not. Cognitive frailty was believed to be a strong indicator as to classifying somebody as frail. Indeed, despite recognising their own physical difficulties, some of our participants relied on their cognitive abilities as a reason to not self-identify as frail. Wang and colleagues [ 26 ] explored the interdependency between cognitive frailty and physical frailty and suggested that early identification of cognitive frailty could facilitate specific interventions which could increase (or delay decline of) independence in older adults. The importance of maintaining independence was key to our participants. A person being classified as frail on the CFS, and them identifying as frail were often not consistent. The maintenance of physical abilities – and thus independence - appeared to reduce their feelings of being frail, participants had a tendency to focus on the preservation of abilities in reasoning why they we not frail, rather than recognising lost abilities. In instances where carers highlighted areas of dependence, some participants began to recognise a state of frailty.

Our participants were classified as being frail according to the CFS [ 17 ]. Although an interplay between physical frailty and dementia/cognitive decline is well recognised [ 27 ], the CFS focuses on function, an individual’s limitation of functions and dependence on others without differentiation between specific physical and cognitive deficits impacting the functional status. It is beyond the scope of this paper to compare measured cognitive and physical abilities of the HERO trial participants. Accepting that the status of individuals may have changed through the first 6 months involved in the trial pre-interview, all trial participants were sufficiently cognisant to provide informed consent to trial participation, and all scored ≥ 20 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment as an eligibility criterion. Exercise has been suggested to be beneficial to improve both physical and cognitive frailty [ 28 ]. Furthermore, frailty is defined as a vulnerability to external stressors [ 3 ], however, there was no indication from our data that people perceived it to be about vulnerability, suggesting further disconnect between health care professionals’ classification of frailty and older people’s beliefs around a state of frailty.

Implications

This study highlights several important factors for frailty research and engaging frail older people in healthcare services. Firstly, our data has highlighted how people find it hard to relate to the terminology around frailty, with many perceiving frailty to be an extreme near end of life state. However, in the UK, many services are termed “frailty” services, thus if people do not relate themselves to this term, it may result in a failure to engage with services that could be of benefit to them. Furthermore, our participants believed that frailty could be reversed or delayed with targeted interventions such as exercise. This has important implications for describing the benefits of exercise to this population.

Frailty is a term used by healthcare professionals to describe a state of physical and mental vulnerability, however, there is a disconnect with how older people and health care professionals understand the term. Frailty as a concept used in healthcare, is difficult for older people to understand and identify with, with most frail older adults associating the term with an extreme degree of physical and cognitive decline. Having a label of being “frail” was something that was deemed to be negative and something to be avoided, suggesting the use of the term needs to be used cautiously. Some frail older people could recognise transient periods where they would identify themselves as frail, but felt able to control their level of frailty to some extent (particularly via exercise). A strong desire to avoid frailty was driven by negative attitudes towards their perceptions of frailty and the association with lower QoL.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Clinical frailty scale

Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research

Home-based Extended Rehabilitation for Older people

Home-based Older People’s Exercise

General Practitioner

National Health Service

Normalisation Process Theory

Process evaluation

Quality of life

Randomised controlled trial

Social cognitive theory

Therapy service manager

Society BG. Frailty- What’s it all about 2018 [Available from: www.bgs.org.uk/resources/frailty-what%E2%80%99s-it-all-about .

Mulla E, Montgomery U. Frailty: an overview. InnovAiT. 2020;13(2):71–9.

Article Google Scholar

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–62.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Hale M, Shah S, Clegg A. Frailty, inequality and resilience. Clin Med. 2019;19(3):219.

World Health Organisation. Ageing and health 2018 [ https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health#:~:text=People%20worldwide%20are%20living%20longer.%20Today%2C%20for%20the,million%20people%20are%20aged%2080%20years%20or%20older .

Costanza R, Fisher B, Ali S, Beer C, Bond L, Boumans R, et al. Quality of life: an approach integrating opportunities, human needs, and subjective well-being. Ecol Econ. 2007;61(2–3):267–76.

Grenier AM. The contextual and social locations of older women’s experiences of disability and decline. J Aging Stud. 2005;19(2):131–46.

Grenier A. Constructions of frailty in the English language, care practice and the lived experience. Ageing Soc. 2007;27(3):425–45.

Warmoth K, Lang IA, Phoenix C, Abraham C, Andrew MK, Hubbard RE, et al. Thinking you’re old and frail’: a qualitative study of frailty in older adults. Ageing Soc. 2016;36(7):1483–500.

Nicholson C, Gordon AL, Tinker A. Changing the way we. view talk about frailty… Age Ageing. 2017;46(3):349–51.

Schoenborn NL, Rasmussen SEVP, Xue Q-L, Walston JD, McAdams-Demarco MA, Segev DL, et al. Older adults’ perceptions and informational needs regarding frailty. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):1–7.

Grenier A. The distinction between being and feeling frail: exploring emotional experiences in health and social care. J Social Work Pract. 2006;20(3):299–313.

Cotter VT, Gonzalez EW. Self-concept in older adults: an integrative review of empirical literature. Holist Nurs Pract. 2009;23(6):335–48.

Ambagtsheer RC, Archibald MM, Lawless M, Mills D, Yu S, Beilby JJ. General practitioners’ perceptions, attitudes and experiences of frailty and frailty screening. Australian J Gen Pract. 2019;48(7):426–33.

Archibald MM, Lawless M, Gill TK, Chehade MJ. Orthopaedic surgeons’ perceptions of frailty and frailty screening. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):1–11.

Prescott M, Lilley-Kelly A, Cundill B, Clarke D, Drake S, Farrin AJ, et al. Home-based Extended Rehabilitation for older people (HERO): study protocol for an individually randomised controlled multi-centre trial to determine the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a home-based exercise intervention for older people with frailty as extended rehabilitation following acute illness or injury, including embedded process evaluation. Trials. 2021;22(1):1–17.

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489–95.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Andrew MK, Fisk JD, Rockwood K. Psychological well-being in relation to frailty: a frailty identity crisis? Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(8):1347–53.

Plano Clark VL. Mixed methods research. J Posit Psychol. 2017;12(3):305–6.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.

Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–60.

Clarke V, Braun V, Hayfield N. Thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology: Practical Guide Res Methods. 2015;3:222–48.

Google Scholar

Puts MT, Shekary N, Widdershoven G, Heldens J, Deeg DJ. The meaning of frailty according to Dutch older frail and non-frail persons. J Aging Stud. 2009;23(4):258–66.

Travers J, Romero-Ortuno R, Bailey J, Cooney M-T. Delaying and reversing frailty: a systematic review of primary care interventions. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(678):e61–9.

Negm AM, Kennedy CC, Thabane L, Veroniki A-A, Adachi JD, Richardson J, et al. Management of frailty: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(10):1190–8.

Wang W, Si H, Yu R, Qiao X, Jin Y, Ji L et al. Effects of reversible cognitive frailty on disability, quality of life, depression, and hospitalization: a prospective cohort study. Aging Ment Health. 2021:1–8.

Robertson DA, Savva GM, Kenny RA. Frailty and cognitive impairment—a review of the evidence and causal mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(4):840–51.

Dulac M, Aubertin-Leheudre M. Exercise: an important key to prevent physical and cognitive frailty. Frailty. 2016:107.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants who took part in this study.

The study is funded by the National Institute for Health Research - Health Technology Assessment programme (15/47/07). The study funder is not involved nor has any responsibility in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and decision to submit the report for publication. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Public Health and Sports Science Department, University of Exeter, Heavitree Road, Exeter, EX1 2LU, UK

Abigail J. Hall & Victoria A. Goodwin

Real World Methods & Evidence Generation, IQVIA, Reading, UK

Silviya Nikolova

Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Bristol, UK

Matthew Prescott

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AH wrote the main manuscript text. All authors contributed to the analysis. All authors contributed to the reviewing and drafting of the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Abigail J. Hall .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Research ethics committee approval was obtained from HRA Yorkshire & The Humber – Bradford Leeds Research Ethics Committee – reference 17/YH/0097. All participants gave written informed consent to take part in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hall, A.J., Nikolova, S., Prescott, M. et al. Older people’s perception of being frail – a qualitative exploration. BMC Geriatr 24 , 453 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05079-x

Download citation

Received : 20 July 2023

Accepted : 14 May 2024

Published : 23 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05079-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Older people

- Qualitative

BMC Geriatrics

ISSN: 1471-2318

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Example of the semi-‐structured interview guide. Viral Hepatitis: Semi-structured interview. M / F Provider / community member / both Age Region. 1. Qualitative interview introduction. Length: 45-60 minutes. Primary goal: To see things the way you see them... more like a conversation with a focus on your experience, your opinions and what you ...

health research: a qualitative study protocol 1 Appendix 1: Semi-structured interview guide Date: Interviewer: Archival #: In person: Teleconference: Start Time: End Time: ... and your views of methods for identifying and display research gaps. The interviews will last approximately 20

First, the semi-structured interview is more powerful than other types of interviews for qualitative research because it allows for researchers to acquire in-depth information and evidence from ...

A semi-structured interview is a data collection method that relies on asking questions within a predetermined thematic framework. However, the questions are not set in order or in phrasing. In research, semi-structured interviews are often qualitative in nature. They are generally used as an exploratory tool in marketing, social science ...

Abstract. Conducted conversationally with one respondent at a time, the semi-structured interview (SSI) employs a blend of closed- and open-ended questions, often accompanied by follow-up why or ...

type of interview process. Therefore, we detail different types of interviews for use in qualitative research. Interviews can be categorized as structured, semi-structured, and unstructured (Neergaard & Leitch, 2015; Nicholls, 2009), and choosing the right type of interview is critical in qualitative research. Types of interviews

Semi-structured Interview Questions for Experiencing Participants (Scholars/Life-long Learners) 1. Describe the things you enjoy doing with technology and the web each week. This is a conversational start in order to put the interviewees at their ease. We are trying to get a sense of their overall digital literacy so that we can set their ...

The semi-structured interview is an exploratory interview used most often in the social sciences for qualitative research purposes or to gather clinical data. While it generally follows a guide or protocol that is devised prior to the interview and is focused on a core topic to provide a general structure, the semi-structured interview also ...

What Is a Semi-structured Interview? Semi-structured interviews are flexible and versa-tile, making them a popular choice for collecting qualitative data (Kallio et al. 2016). They are a conversation in which the researcher knows what she/he wants to cover and has a set of questions and a foundation of knowledge to help guide the

Semi-structured interviews are often preceded by observation, informal and unstructured interviewing in order to allow the researchers to develop a good understanding of the topic of interest necessary for developing relevant and meaningful semi-structured questions. Developing an interview guide often starts with outlining the issues/topics ...

Characteristics of the semi-structured interview: • Involves the implementation of a number of predetermined questions and/or special topics. • These predetermined questions are typically asked of each interviewee in a systematic way and consistent order, but the interviewers are permitted (in fact expected) to probe far beyond the answers to their prepared and standardized questions.

In qualitative research, researchers often conduct semi-structured interviews with people familiar to them, but there are limited guidelines for researchers who conduct interviews to obtain curriculum-related information with academic colleagues who work in the same area of practice but at different higher education institutions.

Semi-Structured Interview and its Methodological Perspectives The semi-structured interview is a method of research commonly used in social sciences. Hyman et al. (1954) describe interviewing as a method of enquiry that is universal in social sciences. Magaldi and Berler (2020) define the semi-structured interview as an exploratory interview.

A semi-structured interview is a qualitative research method used to gain an in-depth understanding of the respondent's feelings and beliefs on specific topics. As the interviewer prepares the questions ahead of time, they can adjust the order, skip any that are redundant, or create new ones. Additionally, the interviewer should be prepared to ...

Qualitative interview is a broad term uniting semi-structured and unstructured interviews. Quali-tative interviewing is less structured and more likely to evolve as a natural conversation; it is of-ten conducted in the form of respondents narrating their personal experiences or life histories. Qualitative interviews can be part of ethnography ...

the question further. In a semi-structured interview, the interviewer also has the freedom to probe the interviewee to elaborate on the original response or to follow a line of inquiry introduced by the interviewee. An example would be: Interviewer: "I'd like to hear your thoughts on whether changes in government policy have

Semi-. structured interview is part of qualitative data collection technique. 3. There are few types of. sampling that we can use to collect qualitative data such as purposive sampling ...

times called a semi-structured interview. Here, the interviewer works from a list of topics that need to be covered with each respondent, but the order and exact wording of questions is not important. Generally, such interviews gather qualitative data, although this can be coded into categories to be made amenable to statistical analysis.

Here is an example of a semi-structured interview guide, for research on ocean data visualization interpretation (Stofer, 2016). I used this guide while presenting global spatial data visualizations to participants in a series with various levels of scaffolding in each visualization as well as two different topics of ocean data.

There are several types of interviews, often differentiated by their level of structure. Structured interviews have predetermined questions asked in a predetermined order. Unstructured interviews are more free-flowing. Semi-structured interviews fall in between. Interviews are commonly used in market research, social science, and ethnographic ...

The Qualitative Report 2020 Volume 25, Number 9, How To Article 1, 3185-3203. Qualitative Interview Questions: Guidance for Novice Researchers. Rosanne E. Roberts. Capella University, Minneapolis ...

• Understand the foundational terminology and purpose of qualitative inquiry • Gain proficiency in field work: mining existing documents, conducting observations, and semi-structured interviews. • Recruit interview participants and develop a semi-structured interview protocol. • Analyzing and validating qualitative data.

Data collection was performed through individual face-to-face interviews using a semi-structured interview guide between one and three months after completion of the RCT study (Mourad et al., 2022). Participants had the opportunity to choose the time and place of the interview.

A semi-structured interview (SSI) is one of the essential tools in conduction qualitative research. This essay draws upon the pros and cons of applying semi-structured interviews (SSI) in the ...

The qualitative PE for the HERO trial employed a qualitative mixed methods approach [] including a variety of data collection methods such as non-participant observations, semi-structured interviews, and documentary analysis.The data for this paper was obtained from the interviews with participants as the focus is on individual's own perception of their frailty.