We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 1: 10 Real Cases on Acute Coronary Syndrome: Diagnosis, Management, and Follow-Up

Nisha Ali; Timothy J. Vittorio

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Case review, case discussion.

- Clinical Symptoms

- Risk Factors

- Classification

- Complications

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Case 1: Diagnostic Evaluation of Chest Pain

A 65-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a complaint of left-sided chest pain radiating to his left arm. There were no alleviating factors. His past medical history included hypertension, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia. He denied any toxic habits. His baseline exercise tolerance is 2 city blocks limited by fatigue. Upon presentation, vital signs were stable and the physical examination was unremarkable. The chest pain was partially relieved by sublingual nitroglycerin. The 12-lead ECG showed nonspecific T-wave inversions in the inferolateral leads. He was administered aspirin, and the chest pain resolved shortly thereafter. Subsequently, he was admitted to the telemetry floor for further evaluation and observation. His serial cardiac biomarkers were negative. He did not have any recurrent chest pain and remained hemodynamically stable throughout the hospital stay. How would you manage this case?

In this clinical scenario, the patient does not fit the complete picture of anginal symptoms. However, the key here is the presence of risk factors and subtle 12-lead ECG changes, which place him at an elevated risk for coronary artery disease. He can be further evaluated by stress testing for risk stratification.

Angina consists of retrosternal chest pain increased by activity or emotional stress and generally relieved by rest or administration of nitroglycerin. The evaluation of chest pain begins with a thorough history and physical examination to delineate the etiology. The list of differential diagnoses is vast, and a detailed review of systems about pertinent diagnoses can narrow down the list. The presence of comorbid conditions and risk factors might hint toward a diagnosis of coronary artery disease. Both serial 12-lead ECG and highly sensitive cardiac troponin T testing should be performed before excluding ongoing ischemic coronary artery disease. Prior to stress testing, the patient should be chest pain free for 24 hours, without dynamic 12-lead ECG changes, and the highly sensitive cardiac troponin T level should be negative or trending downward.

The differential diagnosis of chest pain includes the following:

Coronary artery disease

Aortic dissection

Pericarditis

Pulmonary embolism

Costochondritis/rib fracture

Peptic ulcer disease

Acute cholecystitis

Cervical radiculopathy

Herpes zoster

Anxiety disorder

Chest pain should be classified as anginal or nonanginal based on the history.

Anginal symptoms can be considered in the setting of risk factors and should be evaluated by an appropriate stress modality if the symptoms are vague.

Serial 12-lead ECG and highly sensitive cardiac troponin T should be performed to exclude ongoing ischemic coronary artery disease before stress testing is performed.

Case 2: Diagnosis of Acute Coronary Syndrome

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland, Starting Immediately

Due to the downward trend in respiratory viruses in Maryland, masking is no longer required but remains strongly recommended in Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. Read more .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

Center for Bloodless Medicine and Surgery

Case study: cardiac surgery, case study 1:, radial artery approach for cardiac catheterization followed by an "off-pump" coronary artery bypass surgery.

A 66-year old male Jehovah’s Witness patient was brought to the hospital with chest pain, and referred for a cardiac catheterization. He had a positive nuclear stress test that showed reduced blood flow to the left ventricle with a high suspicion for coronary artery disease.

Dr. John Resar, the director of the cardiac catheterization lab at Johns Hopkins performed the procedure. In order to reduce blood loss from the cardiac catheterization, the approach was planned through the radial artery (in the arm) rather than the femoral artery (in the groin). This approach is associated with reduced bleeding during and after the procedure. The total blood loss during the cardiac catheterization procedure was 50 mls (1% of total blood volume). As expected, the procedure revealed high-grade triple vessel disease (narrowing) that was not treatable with coronary stents. Coronary artery bypass surgery was recommended.

Dr. John Conte performed the coronary bypass surgery. Of interest is the fact that in 1999, Dr. Conte published a case report of the first ever successful bloodless lung transplant in a Jehovah’s Witness patient. In this case presented here, he decided the patient would be best served by performing an "off-pump" cardiac surgery where the heart lung bypass machine is not used. This technique reduces the blood loss that is commonly associated with the bypass machine, since with traditional bypass a substantial amount of the patient’s blood is left behind in the circuit of the machine and is unrecoverable.

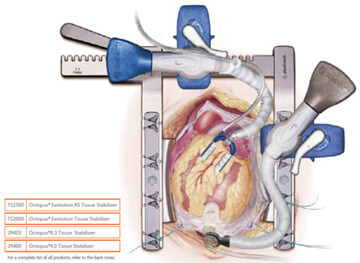

The 4-hour surgery went very well. The saphenous vein from his right leg was harvested using an endoscopic approach. Compared to the traditional technique, this method uses a smaller incision to harvest the vein. The internal mammary artery and the saphenous vein were both used to provide blood flow to the narrowed coronary arteries. A special “octopus retractor” was used to stabilize the heart because during off-pump surgery the heart continues to beat (thus the term “beating heart surgery”), unlike the traditional on-pump method where the heart is arrested and completely still. The hemoglobin level was 13.8 before surgery and 13.0 three days later when the patient was discharged from the hospital. Two weeks after the surgery, the patient attended the open house for our Bloodless Medicine and Surgery Program and looked and felt "as good as ever".

Case Study 2:

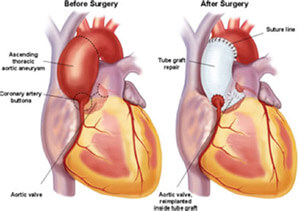

Aortic valve and aortic root replacement without blood transfusion.

A 46-year old female Jehovah’s Witness patient had severe aortic valve regurgitation along with an ascending aortic aneurysm. She had been seen at two other major academic centers in hopes of having a valve replacement along with repair of her “aortic root” (the section of aorta that joins the heart above the aortic valve), but was unable to find a team of physicians that would perform the surgery without blood transfusion.

Dr. Duke Cameron, the former Chief of Cardiac Surgery saw her along with Dr. Steven Frank, Director of the Johns Hopkins Bloodless Medicine and Surgery Program. With the patient and her family present, they reviewed the echocardiogram and cardiac catheterization report from another hospital. At the time, a discussion took place about the various methods of blood conservation and the various alternatives to transfusion. The patient and her family agreed that blood salvage (Cell Saver) and intraoperative autologous normovolemic hemodilution (IANH) were acceptable options. The patient was sent to the lab for routine blood tests and her hemoglobin level was suboptimal (13.0 g/dL) for this type of surgery. One complicating factor was the patient’s body weight of 95 lbs, which means that her total blood volume and red cell mass was about ½ that of a normal sized adult.

The patient was scheduled for a 3-week course of erythropoietin and intravenous iron at the infusion clinic at Johns Hopkins. The patient responded nicely to the treatments and her hemoglobin level increased to 15.1 g/dL, at which time the surgery was scheduled.

After the patient was under general anesthesia, 2 units of her own blood were removed as part of the IANH technique. These 2 units would be given back to her near the end of the surgery. During surgery, the Perfusionist, who operates the heart lung machine, was able to use a method called retrograde autologous prime (RAP), whereby the patient’s own blood is used to prime the circuit in an effort to conserve the patient’s blood volume.

After the surgical procedure, the patient was noted to have some cardiac ischemia (deficient blood flow to the left coronary artery). She was taken to the cardiac cath lab where a coronary stent was placed by an interventional cardiologist into her left main coronary artery. The next day she was weaned of the ventilator and she recovered nicely. Our Bloodless team Hematology consultant, Dr. Linda Resar guided her postoperative therapy which included IV iron and erythropoietin. She was discharged from the hospital with a hemoglobin of 8.0 g/dL, and she and her family had a Baltimore crab dinner before returning home to Roanoke, VA.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 106, Issue 5

- Angina: contemporary diagnosis and management

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4009-6652 Thomas Joseph Ford 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4547-8636 Colin Berry 1

- 1 BHF Cardiovascular Research Centre , University of Glasgow College of Medical Veterinary and Life Sciences , Glasgow , UK

- 2 Department of Cardiology , Gosford Hospital , Gosford , New South Wales , Australia

- 3 Faculty of Health and Medicine , The University of Newcastle , Newcastle , NSW , Australia

- Correspondence to Dr Thomas Joseph Ford, BHF Cardiovascular Research Centre, University of Glasgow College of Medical Veterinary and Life Sciences, Glasgow G128QQ, UK; tom.ford{at}health.nsw.gov.au

https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314661

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

- cardiac catheterization and angiography

- chronic coronary disease

- percutaneous coronary intervention

- coronary artery disease

Learning objectives

Around one half of angina patients have no obstructive coronary disease; many of these patients have microvascular and/or vasospastic angina.

Tests of coronary artery function empower clinicians to make a correct diagnosis (rule-in/rule-out), complementing coronary angiography.

Physician and patient education, lifestyle, medications and revascularisation are key aspects of management.

Introduction

Ischaemic heart disease (IHD) remains the leading global cause of death and lost life years in adults, notably in younger (<55 years) women. 1 Angina pectoris (derived from the Latin verb ‘angere’ to strangle) is chest discomfort of cardiac origin. It is a common clinical manifestation of IHD with an estimated prevalence of 3%–4% in UK adults. There are over 250 000 invasive coronary angiograms performed each year with over 20 000 new cases of angina. The healthcare resource utilisation is appreciable with over 110 000 inpatient episodes each year leading to substantial associated morbidity. 2 In 1809, Allen Burns (Lecturer in Anatomy, University of Glasgow) developed the thesis that myocardial ischaemia (supply:demand mismatch) could explain angina, this being first identified by William Heberden in 1768. Subsequent to Heberden’s report, coronary artery disease (CAD) was implicated in pathology and clinical case studies undertaken by John Hunter, John Fothergill, Edward Jenner and Caleb Hiller Parry. 3 Typically, angina involves a relative deficiency of myocardial oxygen supply (ie, ischaemia) and typically occurs after activity or physiological stress ( box 1 ).

Definition of angina (NICE guidelines) 32

Typical angina: (requires all three)

Constricting discomfort in the front of the chest or in the neck, shoulders, jaw or arms.

Precipitated by physical exertion.

Relieved by rest or sublingual glyceryl trinitrate within about 5 min

Presence of two of the features is defined as atypical angina.

Presence of one or none of the features is defined as non-anginal chest pain.

Stable angina may be excluded if pain is non-anginal provided clinical suspicion is not raised based on other aspects of the history and risk factors.

Do not define typical, atypical and non-anginal chest pain differently in men and women or different ethnic groups.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Reappraisal of ischaemic heart disease pathophysiology. Distinct functional and structural mechanisms can affect coronary vascular function and frequently coexist leading to myocardial ischaemia. CAD, coronary artery disease.

We begin by classifying angina according to pathophysiology. We then consider the current guidelines and their strengths and limitations for assessing patients with recent onset of stable chest pain. We review non-invasive and invasive functional tests of the coronary circulation with linked management strategies. Finally, we point to future directions providing hope for improved patient outcomes and development of targeted disease-modifying therapy. The aim of this educational review is to provide a contemporary approach to diagnosis and management of angina taking into consideration epicardial coronary disease, microcirculatory dysfunction and coronary vasospasm.

Contemporary angina classification by pathophysiology

The clinical history is of paramount importance to initially establish whether the nature of the presenting symptoms is consistent with angina ( box 1 ). Indeed, recent data supports specialist physicians under-recognise angina in up to half of their patients. 10 Furthermore, contemporary clinical trials of revascularisation in stable IHD including the ISCHEMIA trial highlight the importance of good clinical history and listening to our patients to determine the nature and frequency of symptoms which helps to plan management. We propose a classification of angina that aligns with underlying aetiology and related management ( table 1 ).

- View inline

Classification of angina by pathophysiology

Angina with obstructive coronary artery disease

2018 ESC guidelines on myocardial revascularisation define obstructive CAD as coronary stenosis with documented ischaemia, a haemodynamically relevant lesion (ie, fractional flow reserve (FFR) ≤0.80 or non-hyperaemic pressure ratio (NHPR) (eg, iwFR≤0.89)) or >90% stenosis in a major coronary vessel ( table 1 ). There is renewed interest in NHPRs (iwFR, resting full-cycle ratio (RFR) and diastolic pressure ratio (dPR)) as data have emerged in support of numerical equivalency between these indices suggesting all can be used to guide treatment strategy. 11 Angina with underlying obstructive CAD allows symptom guided myocardial revascularisation (often with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)) and is effective in reducing ischaemic burden and symptoms (in many patients). Recent studies have served evidence that functional coronary disorders overlap and may contribute to angina even in patients with obstructive epicardial CAD. Dynamic changes in lesion or vessel ‘tone’ and propensity to vasoconstriction is important and may cause rest angina that is frequently overlooked in patients with obstructive CAD. 12 During invasive physiological assessment of ischaemia during exercise, Asrress et al showed that ischaemia developed at FFR averaging≈0.76 which is not often observed with adenosine induced hyperaemia. 13 This finding implies there are other important drivers of subendocardial ischaemia (myocardial supply:demand factors). Furthermore, it reinforces that angina is not synonymous with ischaemia or flow-limiting coronary disease (eg, abnormal FFR or NHPR). Coronary anatomy and physiology should not be considered in isolation but in the context of the patient.

Angina-myocardial ischaemia discordance

Although obstructive CAD or microvascular dysfunction may be present, the link between ischaemia and angina is not clearcut. The ‘ischaemic threshold’ (the heart rate-blood pressure product at the onset of angina) has intraindividual and interindividual variability. 14 Innate differences in vascular tone and endocrine changes (eg, menopause) may influence propensity to vasospasm while environmental factors including cold environmental temperature, exertion and mental stress are relevant. The large international CLARIFY registry highlighted the importance of symptoms, showing that angina with or without concomitant ischaemia, was more predictive of adverse cardiac events compared with silent ischaemia alone. 15 Other potential drivers of discordance between angina and ischaemia include variations in pain thresholds and cardiac innervation (eg, diabetic neuropathy).

Symptoms and/or signs of ischaemia but no obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA)

Cardiologists are inclined to adopt a ‘stenosis centric’ approach to patient management; however, as clinicians we must appreciate that all factors are relevant, including coronary anatomy and function but systemic health and the psychosocial background ( figure 2 ). First, systemic factors including heart rate, blood pressure (and their product) and myocardial supply:demand ratio (Buckberg index) are relevant. 16 Reduced myocardial oxygen supply from problems such as anaemia or hypoxaemia should always be considered.

Contributing factors to myocardial ischaemia. The contributors to the physiological myocardial perfusion gradient and resultant ischaemia can be broken down at patient-level into systemic, cardiac and coronary factors. CAD, coronary artery disease; SEVR, subendocardial viability ratio.<Modified with permission from 47 >.

Second, coronary factors are well recognised but certain nuances are overlooked. In 2018, the first international consensus guidelines clarify that a definite diagnosis of MVA may be made in patients with angina with no underlying obstructive CAD, evidence of reversible ischaemia on functional testing and objective evidence of coronary microvascular dysfunction ( table 1 ). 17 ‘Probable MVA’ is defined by three of the above criteria. Coronary microvascular dysfunction may be structural (eg, small vessel rarefaction or increased media: lumen ratio) or functional (eg, endothelial impairment) and these disorders may coexist. Other coronary causes of INOCA include intramyocardial ‘tunnelled’ segments of epicardial arteries (myocardial ‘bridging’) who may have ischaemia on exercise. These segments are particularly susceptible to vasoconstriction due to endothelial impairment. 18 Coronary arteriovenous malformations are rare but may also cause of myocardial ischaemia. Vasospastic angina (‘Prinzmetal’s angina’) is typically described as recurrent rest angina with focal occlusive proximal epicardial often seen in young smokers with characteristic episodic ST segment elevation during attacks. Notably, the more common form of VSA is distal and diffuse subtotal epicardial vasospasm and is characterised by ST segment depression and may occur during exertion. Typical cardiac risk factors and endothelial impairment may be implicated. 19

The long-term (sometimes lifelong) burden of MVA and/or VSA on physical and mental well-being can be profound. Patients with these conditions commonly attend primary care and are repeatedly hospitalised with acute coronary syndromes, arrhythmias and heart failure driving up health resource utilisation, morbidity and reducing quality of life. 20 21

The third and final group of factors that drive ischaemia in patients with angina but without obstructive CAD include cardiac factors . These include left ventricular hypertrophy or restrictive cardiomyopathy where subendocardial ischaemia results impaired perfusion from arterioles penetrating deeper into myocardial tissue with shorter diastole, enhanced systolic myocardial vessel constriction and enhanced interstitial matrix. 22 Heart failure (with reduced or preserved ejection fraction) can lead to elevated left ventricular end diastolic pressure which reduces the diastolic myocardial perfusion gradient. Valvular heart disease (eg, aortic stenosis (AS)) is an important consideration in patients with INOCA. In AS, most experts support haemodynamic factors as the main cause of ischaemia, especially since symptoms and coronary flow reserve (CFR) improve immediately after valve replacement. 23 Patients with INOCA may have increased painful sensitivity to innocuous cardiac stimuli (eg, radiographic contrast) without inducible ischaemia. Furthermore, some affected patients have a lower pain threshold and tolerance to the algogenic effects of adenosine (thought to be the main effector of ischaemia mediated chest pain). 24

Gender differences and angina presentation

The WISE (Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation) study highlighted that over 2/3 of women with angina had no obstructive CAD and the majority of these had functional impairments in the coronary microcirculation associated with significant impairments in health-related quality of life. 25 Indeed, women have more non-obstructive CAD and functional IHD which are frequently overlooked and hence undertreated. 26 27 Over time and at different ages, women have a similar or slightly higher prevalence of angina than men across countries independent of diagnostic and treatment practices. 28 Different patterns of IHD may be anticipated to cause different angina symptoms between genders. Nonetheless, recent evidence moves the field away from the ‘male-typical, female-atypical’ model of angina towards a ‘gender continuum’ whereby the objective reports between men and women’s symptoms are more similar than treating physicians perceive. Interestingly, dyspnoea was a feature in around ¾ of angina presentations without any significant difference between the sexes. 29

Assessment: current guidelines

Assessment strategies in current major international guidelines focus on the detection of underlying obstructive CAD. European and American guidelines (ESC and ACC/AHA, respectively) favour a Bayesian approach whereby overall probability of obstructive CAD after testing is determined from pretest probability modified by the diagnostic test results. The ACC/AHA guidelines determine pretest risk from a modified Diamond Forrester model, 30 whereas the Europeans favour the CADC (Coronary Artery Disease Consortium) model which avoids overestimation seen with Diamond-Forrester and appears a more accurate assessment of pretest risk. 31 Both current guidelines stratify pretest risk into low, intermediate or high groups with use of non-invasive testing suggested in the intermediate group (ACC/AHA arbitrarily defined as 10%–90% or 15%–85% in ESC).

In stark contrast, the NICE CG95 2016 update ‘chest pain of recent onset: assessment and diagnosis’ discarded the Bayesian pretest risk assessment. NICE advocates first-line multidetector CT coronary angiography (CTCA) in all patients with typical or atypical chest pain ( box 1 ), those whose history does not suggest angina but who have ST changes or Q waves on a resting ECG. 32 Functional testing (eg, exercise stress echo or stress perfusion magnetic resonance—CMR) are relegated to second-line if CTCA is non-diagnostic or the clinical significance of known CAD needs clarified. Potential benefits of this approach include a much higher diagnostic accuracy for detection of atherosclerotic heart disease than functional testing which potentially carries the best long-term prognostic information for patients with CAD. 27 Extended 5-year outcomes from SCOTHEART showed a reduction in the combined endpoint of death from coronary heart disease or non-fatal myocardial infarction among the group randomised to CTCA compared with standard care (2.3% vs 3.9%; absolute risk reduction (ARR) 1.6% number needed to treat (NNT) 63). This effect was driven by better targeting of preventative therapies. The authors report that although overall prescriptions of preventive cardiovascular medications were only modestly increased (~10% higher) in the CTCA arm, changes in such therapies occurred in around one in four patients allowing more personalised treatment to patients with most coronary atheroma in the CT group.

These results should be considered in relation to design limitations of this trial. There was no control procedure (test vs no test), the threshold for prescribing preventive therapy with statins was 20%–30% likelihood of a CHD event in 10 years (much higher than many contemporary healthcare systems), CTCA was performed on top of treadmill exercise testing which has poor test accuracy in distinct patient groups, notably women, and the procedures were unblinded and open-label. Outcome reporting that is narrowly focused on CHD does not take account of other cardiovascular events, such as hospitalisation for arrhythmias and heart failure, which have implications for quality of life. In PROMISE, a ‘head-to-head’ trial of CTCA versus functional testing, there were no differences in health outcomes. 33 In the interests of providing patients and clinicians with a reliable and accurate test result, a strategy based on anatomical CTCA has fundamental limitations. SCOT-HEART identified that obstructive CAD affects the minority (one in four) patients presenting to the Chest Pain Clinic with known or suspected angina. This means that an anatomical test strategy with CTCA leaving the aetiology and treatment unexplained in the majority of affected patients, which becomes all the more relevant considering that anginal symptoms and quality of life are worse when CTCA is used. 34 Diagnostic options are enhanced by advances in technology and tests for the functional significance of CAD are now feasible, but at significant cost. 35 NICE guidelines state that HeartFlow FFR CT should be considered as an ‘option for patients with stable, recent onset chest pain who are offered CCTA as part of the NICE pathway on chest pain’. Using HeartFlow FFR CT may avoid the need for invasive coronary angiography and revascularisation; however, major randomised controlled trials are ongoing (eg, FORECAST study NCT03187639 ).

We support efforts to provide a definitive diagnosis for patients with ongoing angina symptoms after a ‘negative’ CTCA, initially using non-invasive ischaemia testing. Notably, the recent International Standardised Criteria for diagnosing ‘suspected’ MVA would be met in patients with symptoms of myocardial ischaemia, no obstructive CAD and objective evidence of myocardial ischaemia ( table 1 ). Invasive testing for diagnosis of MVA could be reserved for subjects with refractory symptoms and negative ischaemia testing or diagnostic uncertainty. The criteria for ‘definite MVA’ require the above AND objective evidence of microvascular dysfunction (eg, reduced CFR or raised microvascular resistance).

Limitations of current guidelines

There are limitations to the current NICE-95 guideline, not least the logistics and cost of service provision with an estimated 700% increase in cardiac CT required across the UK. 36 Importantly, what do we report to the majority of patients with anginal chest pain but no obstructive CAD on the CTCA? In fact, only 25% of patients had obstructive CAD and at 6 weeks based on the CTCA findings, 66% of patients were categorised as not having angina due to coronary heart disease. The possibility of false reassurance for the patients with angina and INOCA is an open question and may be one contributing factor for the lack of improvement in angina and quality of life in the CTCA group vs standard care. 34 We must strive to deliver patient-centred care, recognising that most patients seek explanation for their symptoms in combination with effective treatment options. 37 CTCA is an insensitive test for disorders of coronary vascular function, which may affect the majority of patients attending with anginal symptoms. Since the majority of affected patients have no obstructive CAD, and the majority of them are women, an anatomical strategy introduces a sex-bias into clinical practice, whereby a positive test result (obstructive CAD) is more likely to occur in men and a positive test for small vessel disease is less likely to occur in women. Furthermore, patient-reported outcomes including angina limitation, frequency and overall quality of life improve less after CTCA compared with standard care, notably in patients with no obstructive CAD. 34 Non-invasive functional testing with positron emission tomography (PET), echo and most recently stress perfusion CMR has diagnostic value for stratified medicine. Finally, stratification of patients using luminal stenosis severity on angiography overlooks the spectrum of risk associated with overall plaque burden and may miss functional consequences associated with diffuse but angiographically mild disease (particularly when subtending large myocardial mass).

Non-invasive functional testing includes myocardial perfusion scintigraphy, exercise treadmill testing (including stress echocardiography) or contrast-enhanced stress perfusion MRI depending on local availability. Novel pixel-wise absolute perfusion quantification of myocardial perfusion by CMR will likely improve the efficiency of absolute quantification of myocardial blood flow by CMR. 38 PET is the reference-standard non-invasive assessment of myocardial blood flow permitting quantitative flow derivation in mL/g/min. Clinically, PET-derived quantification of myocardial blood flow (MBF) can assist in the diagnosis of diffuse epicardial or microvascular disease; however, limitations include poor availability and exposure to ionising radiation. Non-invasive workup often provides important insights on coronary microvascular function and are reviewed in detail elsewhere. 39

With functional testing relegated to second-line testing, clinicians may forgo additional tests after a negative CTCA particularly in an era of fiscal restraint and if patients’ symptoms are viewed as atypical. One important group that will be disparately affected by an ‘anatomy first’ strategy are women—over half of all patients with suspected angina in the large prospective trials of CTCA are female. While the benefits of CTCA to diagnose CHD and prevent CHD events are similar in women and men, the large majority of patients undergoing CTCA do not have obstructive CAD potentially leading to misdiagnosis and suboptimal management in patients with INOCA. 33 Women, are most likely to have no obstructive CAD and their cardiac risk is associated with severely impaired CFR and not obstructive CAD. 40 Overall, there is growing awareness of sex-specific differences in coronary pathophysiology and potential for different patterns of CAD in women. This is a rapidly evolving fertile area for further research.

Invasive coronary angiography and physiological assessment

UK NICE guidelines suggest that invasive coronary angiography is a third-line investigation for angina when the results of non-invasive functional imaging are inconclusive. Patients with typical symptoms, particularly those in older age groups with higher probability of non-diagnostic CTCA scans, often proceed directly to invasive coronary angiography. During cardiac catheterisation, assuming that epicardial CAD is responsible for their symptoms, visual assessment for severe angiographic stenosis (>90%) is sufficient to establish significance and treatment plan for these patients. Two common pitfalls for visual interpretation of angiograms were recently highlighted by two coronary physiology pioneers Gould and Johnson. Using their quantitative myocardial perfusion database of over 5900 patients showing that occult coronary diffuse obstructive coronary disease or flush ostial stenosis may be both be overlooked on angiography and mislabelled as microvascular angina with suboptimal treatment. 41 The ischaemic potential of indeterminate coronary lesions (~40%–70% diameter stenosis) is best assessed using pressure-derived indices, such as FFR, and non-hyperaemic pressure ratios (NHPR: dPR, nstantaenous wave free ratio (iwFR) and others) to guide revascularisation decisions. However, as is the case with coronary angiography, these indices do not inform the clinician about disorders of coronary artery vasomotion.

Invasive tests of coronary artery function are the reference standard for the diagnosis of coronary microvascular dysfunction 17 and vasospastic angina ( table 1 ; figure 1 ). 42 Coronary microvascular resistance may be directly measured using guidewire-based physiological assessment during adenosine induced hyperaemia. Methods to assess this include using a pressure-temperature sensitive guidewire by thermodilution (index of microcirculatory resistance; IMR) or Doppler ‘ComboWire’ (hyperaemic microvascular resistance; HMR). These metrics have been the focus of a recent review article in Heart. 43 There are several other haemodynamic indices of microvascular function including instantaneous hyperaemic diastolic pressure velocity slope, wave intensity analysis and zero flow pressure. A detailed description of these parameters is out with the scope of this review. 41 Elevated coronary microvascular resistance (eg, IMR >25) carries prognostic utility in patients with reduced CFR but unobstructed arteries. Lee et al found over fivefold higher risk of adverse cardiac events in these subjects compared with controls with normal microvascular function. 44

CFR is the ratio of maximum hyperaemic blood flow to resting flow. CFR in the absence of obstructive CAD can signify impaired microvascular dilation. Lance Gould first introduced this concept almost 50 years ago but more recently proposed that CFR should be considered in the context of the patient and the hyperaemic flow rate. 41 The absolute threshold for abnormal CFR varies depending on the method of assessment, the patient population studies and the controversy reflects the dichotomous consideration of the continuous physiological spectrum of ischaemia. Abnormal CFR thresholds vary from ≤2.0 or ≤2.5 with more restrictive criteria for abnormal CFR (<1.6) being more specific for myocardial ischaemia and worse outcomes but at the cost of reduced sensitivity. On the other hand, studies of transthoracic Doppler derived CFR (which has less reproducibility) often use cut-offs of 2.5 with some observational evidence of worse outcomes in the INOCA population with CFR below this threshold. 45 The influence of rate-pressure product on resting flow and its correction for CFR determination should be considered.

Systolic endocardial viability ratio (SEVR) is a ratio of myocardial oxygen supply:demand derived from the aortic pressure-time integral (diastole:systole). However, it is well known that blood pressure, pulse and SEVR perturbations influence CFR more closely than microcirculatory resistance. Reduced CFR without raised microvascular resistance still portends increased cardiovascular risk 44 and may be a distinct subgroup with different drivers of ischaemia (eg, abnormal supply:demand systemic haemodynamic factors; figure 2 ). Alternatively, these patients may be at an earlier stage of disease prior to more established structural microvascular damage. Sezer et al showed the pattern of coronary microvascular dysfunction early in type II diabetes was driven by disturbed coronary regulation and high resting flow. 46 In longstanding diabetes however, elevated microvascular resistance was observed reflecting established structural microvascular disease. This process matches the paradox of microvascular disease in diabetic nephropathy where increased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) typifies the early stages of disease prior to later structural damage and reduction in GFR.

The third mechanism of microvascular dysfunction is inappropriate propensity to vasoconstriction of the small coronary arteries, typically this is assessed using intracoronary acetylcholine infusions as a pharmacological probe.

Rationale and benefit of invasive coronary function testing in INOCA

We contend that a complete diagnostic evaluation of the coronary circulation should assess structural and functional pathology. 47 The British Heart Foundation CorMicA trial provides evidence about the opportunity to provide a specific diagnosis to patients with angina using an interventional diagnostic procedure (IDP) when obstructive CAD is excluded by invasive coronary angiography. Consenting patients were randomised 1:1 to the intervention group (stratified medical therapy, IDP disclosed) or the control group (standard care, IDP sham procedure, results not disclosed). The diagnostic intervention included pressure guidewire-based assessment of FFR, CFR and IMR during adenosine induced hyperaemia (140 µg/kg/min). Vasoreactivity testing was performed by infusing incremental concentrations of acetylcholine (ACh) followed by a bolus vasospasm provocation (up to 100 µg). The diagnosis of a clinical endotype (microvascular angina, vasospastic angina, both, none) was linked to guideline-based management. The primary endpoint was the mean difference in angina severity at 6 months (as assessed by the Seattle Angina Questionnaire summary score—SAQSS) which was analysed using a regression model incorporating baseline score. A total of 391 patients were enrolled between 25/11/2016 and 11/12/2017. Coronary angiography revealed obstructive disease in 206 (53.7%). One hundred and fifty-one (39%) patients without angiographically obstructive CAD were randomised. The underlying abnormalities revealed by the IDP included: isolated microvascular angina in 78 (51.7%), isolated vasospastic angina in 25 (16.6%), mixed (both) in 31 (20.5%) and non-cardiac chest pain in 17 (11.3%). The intervention was associated with a mean improvement of 11.7 units in the SAQSS at 6 months (95% CI 5.0 to 18.4; p=0.001). In addition, the intervention led to improvements in the quality of life (EQ5D index 0.10 units; 0.01 to 0.18; p=0.024). After disclosure of the IDP result, over half of treating clinicians changed their diagnosis about the aetiology of their patients’ symptoms. There were no procedural serious adverse events and no differences in major adverse cardiac events (MACE) at 6 months. Interestingly, there were sustained quality of life benefits at one year for INOCA patients helped by correct diagnosis and linked treatment started at the index invasive procedure. 48 Future trials are anticipated to determine the wider external validity of this approach.

Medical therapy to prevent new vascular events should be considered and these include consideration of aspirin, ACE inhibitors (ACEi) and statins. The latter two agents have pleiotropic properties including beneficial effects on endothelial function and so may be helpful in treating coronary microvascular dysfunction. Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate tablets or spray should be used for the immediate relief of angina and before performing activities known to bring on angina.

Non-pharmacological

As with many cardiovascular diseases, lifestyle modification including risk factor control and patient education are key. Lifestyle recommendations are covered in detail in recent ESC guidelines. The adverse effect of angina on patient well-being and quality of life can be substantial. It is crucial that we assess for this and manage appropriately. After diagnosis with angina, cardiac rehabilitation can be useful to educate and build confidence. One useful patient led education aid is called the ‘Angina plan’. This tool is a workbook and relaxation plan delivered in primary care, which helps improve angina symptoms (frequency and limitation) while reducing anxiety and depression. 49 The ORBITA trial highlights the benefits of placebo effect and we support that the positive diagnosis may be therapeutic in itself. Angina symptoms are often subjective and multifactorial in origin, so patient education and validation of symptoms may facilitate further improvement.

Management: Non-obstructive CAD

Generic guidelines on angina management frequently overlooks the precision medicine goal whereby treatment is targeted to underlying pathophysiology. There is a lack of high-quality clinical trial data for treating microcirculatory dysfunction. The current article thus proposes a reasoned approach to management based on evaluation of pathophysiological mechanisms.

We contest that angina and INOCA are syndromes and not a precise diagnosis (akin to myocardial infarction with no obstructive CAD—MINOCA). As such, by stratifying treatment according to underlying pathophysiology, we may realise better outcomes for our patients.

Impaired coronary vasodilator capacity (reduced CFR)

Bairey Merz et al performed a randomised controlled trial of ranolazine in the WISE population. Notably, there was no net benefit effect on the INOCA population as a whole; however, in patients with reduced CFR (<2.5), there was a benefit suggestion of improved myocardial perfusion reserve index (MPRi) after established treatment. 50 Lanza and Crea highlight that subjects with reduced CFR might preferentially be treated with drugs that reduce myocardial oxygen consumption (eg, beta-blockers (BB)—for example, Nebivolol 1.25–10 mg daily). 51 There is accumulating evidence that long acting nitrates are ineffective or even detrimental in MVA. Lack of efficacy may relate to poor tolerability, steal syndromes through regions of adequately perfused myocardium and/or related to the reduced responsiveness of nitrates within the coronary microcirculation. 52 Furthermore, chronic therapy with nitrate may induce endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress, predominantly via endothelin dependent pathways. 53

Increased microvascular constriction (structurally increased microvascular resistance or functional propensity to microvascular spasm)

Subjects with increased microvascular vasoconstriction may be treated with vasodilator therapies acting on the microcirculation. These include calcium channel blockers (CCB—for example, amlodipine 2.5–10 mg daily) or nicorandil (eg, 5–30 mg two times a day). Hyper-reactivity to constrictor stimuli resulting in propensity to microvascular spasm may be provoked by endothelial dysfunction. This was first described my Mohri et al over three decades ago with recent physiological studies suggesting treatment aimed at improving endothelial function (eg, ACEi, Ramipril 2.5–10 mg) may improve the microvascular tone and/or the susceptibility to inappropriate spasm. 54 55 A detailed discussion of all potentially therapeutic options for coronary microvascular dysfunction is beyond the scope of this article; however, a systematic review by Marinescu et al may be of interest to readers wishing further information. 56

Epicardial spasm (vasospastic angina)

The poor nitrate response or tolerance seen in MVA contrasts with patients with vasospastic angina, in whom nitrates are a cornerstone of therapy and BB are relatively contraindicated. 7 Dual pathologies (VSA with underlying microvascular disease) is increasingly recognised. A diagnosis of VSA facilitates treatment using non-dihydropiridine calcium antagonists (eg, diltiazem-controlled release up to 500 mg daily). Overall, CCB are effective in treating over 90% of patients. 57 High doses of calcium antagonists (non-dihydropiridine and dihydropyridine) may be required either alone or in combination. Unfortunately, ankle swelling, constipation and other side effects may render some patients intolerant. In these cases, long-term nitrates may be used with good efficacy in this group. In about 10% of cases, coronary artery spasm may be refractory to optimal vasodilator therapy. Japanese VSA registry data shows nitrates were not associated with MACE reduction in VSA, and importantly when added to Nicorandil were potentially associated with higher rates of adverse cardiac events. 58 Alpha blockers (eg, clonidine) may be helpful in selected patients with persistent vasospasm. In patients with poor nitrate tolerance the K+-channel opener nicorandil (5–10 mg two times a day) can be tried. Consider secondary causes in refractory VSA (eg, coronary vasculitis) and in selected patients with ACS presentations, coronary angioplasty may be considered as a bailout option.

Management: Obstructive CAD

Pharmacological.

Although NICE guidelines offer either BB or CCB first line, although we support BB initially because they are generally better tolerated ( table 2 ). 59 Long-term evidence of efficacy is limited between BB and CCB and there are no proven safety concerns favouring one or the other. Dihydropyridine calcium may be added to BB if blood pressure permits. NICE CG126 states third line options can be either added on (or substituted if BB/CCB not tolerated). These include nitrates (eg, isosorbide mononitrate 30–120 mg controlled release), ivabradine (eg, 2.5–7.5 mg two times a day), nicorandil (5–30 mg two times a day) or ranolazine (375–500 mg two times a day). These are all third line medications that can be used based and combined with BB and/or CCB depending on comorbidities, contraindications, patient preference and drug costs ( figure 3 ). The RIVER-PCI study found that anti-ischaemic pharmacotherapy with ranolazine did not improve the prognosis of patients with incomplete revascularisation after percutaneous coronary intervention. 60 This was a reminder that alleviation of ischaemia may not improve ‘hard’ endpoints in patients with chronic coronary syndromes but helps us to remain focused on improving their quality of life.

Angina pharmacotherapy

Empirical pharmacological treatments for patients with angina. ACEi, Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ASP, aspirin; BB, beta-blocker; Endo, endothelial; IVA, ivabradine; MVA, microvascular angina; NIC, nicorandil; NIT, nitrate; Obs CAD, obstructive coronary artery disease;, RAN, ranolazine; RF, risk factor.

Revascularisation

Recently revised 2018 ESC guidelines suggest that myocardial revascularisation is indicated to improve symptoms in haemodynamically significant coronary stenosis with insufficient response to optimised medical therapy. Patients’ wishes should be accounted for in relation to the intensity of antianginal therapy as PCI can offer patients with angina and obstructive CAD a reduced burden from polypharmacy. Angina persists or recurs in more than one in five patients following PCI and microvascular dysfunction may be relevant. Guidelines support consideration of revascularisation for prognosis in asymptomatic ischaemia in patients with large ischaemic burden (left main/proximal left anterior descending artery stenosis >50%) or two/three vessel disease in patients with presumed ischaemia cardiomyopathy (LVEF<35%).

Refractory angina is common in patients with complex CAD including those with previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and chronic total occlusions (CTOs). Over the last decade, vast strides in technique, training and tools have delivered major increases in the success of CTO PCI. These angina patients often have incomplete revascularisation with lesions or anatomy previously considered ‘unsuitable for intervention’ but now amenable to treatment by trained operators. A recent review article in Heart summarises non-pharmacological therapeutic approaches to patients with refractory angina including cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), stellate ganglion nerve blockade, Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)/spinal cord stimulation and pain modulating antidepressants (eg, imipramine). 61 Of note, coronary sinus reducers deployed using a transcatheter venous system have shown early promise in clinical studies.

Future directions

Based on test accuracy, health and economic benefits, non-invasive and invasive functional tests should be considered a standard of care in patients with known or suspected angina, especially if obstructive CAD has been excluded by CT or invasive coronary angiography. Computational fluid dynamic modelling of the functional significance of CAD, notably with FFRct, is an emerging option and clinical trials, including FORECAST (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03187639 ) and PRECISE ( NCT03702244 ), are ongoing. The use of computational modelling as a diagnostic tool in patients with microvascular angina or coronary vasomotion disorders remains to be determined.

Systemic vascular abnormalities were recently highlighted in patients with INOCA potentially supporting a therapeutic role for targeted vascular therapy, for example, using selective endothelin-A receptor antagonists. 19 The MRC Framework for Stratified Medicine is applicable to patients with angina and we believe genetic testing with precision medicine holds future promise.

The optimal management of patients with known or suspected angina begins with establishing the correct diagnosis.Around one half of angina patients have no obstructive coronary disease; many of these patients have microvascular and/or vasospastic angina.Non-invasive assessment with CTCA is a sensitive anatomical test for plaque which assists in initial treatment and risk stratification. Anatomical imaging has fundamental limitations to rule in or rule out coronary vasomotion disorders in patients with symptoms and/or signs of ischaemia but no obstructive CAD (INOCA). Women are disproportionately represented in this group with MVA and/or VSA, the two most common causes of diagnoses. A personalised approach to invasive diagnostic testing permits a diagnosis to be made (or excluded) during the patients’ index presentation. This approach helps stratify medical therapy leading to improved patient health and quality of life. Physician appraisal of ischaemic heart disease (IHD) should consider all pathophysiology relevant to symptoms, prognosis and treatment to improve health outcomes for our patients. More research is warranted, particularly to develop disease modifying therapy.

ESC curriculum: stable CAD

Precipitants of angina.

Prognosis of chronic IHD.

Clinical assessment of known or suspected chronic IHD.

Indications for, and information derived from, diagnostic procedures including ECG, stress test in its different modalities (with or without imaging, exercise and stress drugs) and coronary angiography.

Management of chronic IHD, including lifestyle measures and pharmacological management.

Indications for coronary revascularisation including PCI/stenting and CABG.

Angina pectoris is a clinical syndrome occurring in patients with or without obstructive epicardial coronary artery disease.

Diagnostic testing in angina is symptom driven and so should provide patients and their physicians with an explanation for their symptoms and used to stratify management and offer prognostic insights.

Microvascular and/or vasospastic angina are common disorders of coronary artery function that may be overlooked by anatomical coronary testing, leading to false reassurance and adverse prognostic implications.

CME credits for Education in Heart

Education in Heart articles are accredited for CME by various providers. To answer the accompanying multiple choice questions (MCQs) and obtain your credits, click on the 'Take the Test' link on the online version of the article. The MCQs are hosted on BMJ Learning. All users must complete a one-time registration on BMJ Learning and subsequently log in on every visit using their username and password to access modules and their CME record. Accreditation is only valid for 2 years from the date of publication. Printable CME certificates are available to users that achieve the minimum pass mark.

Supplemental material

- Naghavi M ,

- Allen C , et al

- ↵ Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2018 . London : British Heart Foundation , 2018 .

- Kligfield P

- ↵ Cine-coronary arteriography . Circulation . 227 East Washington Square, Philadelphia, PA 19106. : Lippincott Williams and Wilkins , 1959 .

- Kaski J-C ,

- Gersh BJ , et al

- Saraste A , et al

- Montalescot G ,

- Sechtem U ,

- Achenbach S , et al

- Corcoran D ,

- Peterson ED ,

- Dai D , et al

- Arnold SV ,

- Grodzinsky A ,

- Gosch KL , et al

- Park J , et al

- Asrress KN ,

- Williams R ,

- Lockie T , et al

- Garber CE ,

- Carleton RA ,

- Camaione DN , et al

- Greenlaw N ,

- Tendera M , et al

- Johnson NP ,

- Nitroglycerine JNP

- Camici PG ,

- Beltrame JF , et al

- Corban MT ,

- Prasad M , et al

- Rocchiccioli P ,

- Good R , et al

- Maddox TM ,

- Stanislawski MA ,

- Grunwald GK , et al

- Tavella R ,

- Tucker G , et al

- Raphael CE ,

- Parker KH , et al

- Pasceri V ,

- Buffon A , et al

- Kelsey SF ,

- Matthews K , et al

- Stanley B ,

- ↵ Ct coronary angiography in patients with suspected angina due to coronary heart disease (SCOT-HEART): an open-label, parallel-group, multicentre trial . The Lancet 2015 ; 385 : 2383 – 91 . doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60291-4 OpenUrl

- Hemingway H ,

- Langenberg C ,

- Damant J , et al

- Kreatsoulas C ,

- Shannon HS ,

- Giacomini M , et al

- Diamond GA ,

- Forrester JS

- Bittencourt MS ,

- Polonsky TS , et al

- (NICE) NIfHaCE

- Douglas PS ,

- Hoffmann U ,

- Patel MR , et al

- Williams MC ,

- Shah A , et al

- Leipsic J ,

- Pencina MJ , et al

- Nicol EPS ,

- Roobottom C , British Society of cardiovascular Imaging/ British Society of cardiovascular computed tomography

- Richards T ,

- Coulter A ,

- Hsu L-Y , et al

- Szymonifka J ,

- Twisk JWR , et al

- Taqueti VR ,

- Cook NR , et al

- Beltrame JF ,

- Kaski JC , et al

- Aetesam-ur-Rahman M , et al

- Hwang D , et al

- Hachamovitch R ,

- Murthy VL , et al

- Kocaaga M ,

- Aslanger E , et al

- Berry C , B

- Sidik N , et al

- Robinson J , et al

- Bairey Merz CN ,

- Handberg EM ,

- Shufelt CL , et al

- Horowitz JD

- Kröller-Schön S , et al

- Koyanagi M ,

- Egashira K , et al

- Fearon WF ,

- Kobashigawa JA , et al

- Marinescu MA ,

- Löffler AI ,

- Ouellette M , et al

- Nishigaki K ,

- Yamanouchi Y , et al

- Takahashi J ,

- Takagi Y , et al

- Généreux P ,

- Iñiguez A , et al

- Sainsbury PA ,

- Jolicoeur EM

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data.

This web only file has been produced by the BMJ Publishing Group from an electronic file supplied by the author(s) and has not been edited for content.

- Data supplement 1

Twitter @tomjford

Contributors TJF devised and wrote the article and figures. CB edited and approved the final manuscript.

Funding British Heart Foundation (PG/17/2532884; RE/13/5/30177; RE/18/634217).

Competing interests CB is employed by the University of Glasgow which holds consultancy and research agreements with companies that have commercial interests in the diagnosis and treatment of angina (Abbott Vascular, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Menarini, Opsens, Philips and Siemens Healthcare.)

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Create Free Account or

- Acute Coronary Syndromes

- Anticoagulation Management

- Arrhythmias and Clinical EP

- Cardiac Surgery

- Cardio-Oncology

- Cardiovascular Care Team

- Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology

- COVID-19 Hub

- Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease

- Dyslipidemia

- Geriatric Cardiology

- Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies

- Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention

- Noninvasive Imaging

- Pericardial Disease

- Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism

- Sports and Exercise Cardiology

- Stable Ischemic Heart Disease

- Valvular Heart Disease

- Vascular Medicine

- Clinical Updates & Discoveries

- Advocacy & Policy

- Perspectives & Analysis

- Meeting Coverage

- ACC Member Publications

- ACC Podcasts

- View All Cardiology Updates

- Earn Credit

- View the Education Catalog

- ACC Anywhere: The Cardiology Video Library

- CardioSource Plus for Institutions and Practices

- ECG Drill and Practice

- Heart Songs

- Nuclear Cardiology

- Online Courses

- Collaborative Maintenance Pathway (CMP)

- Understanding MOC

- Image and Slide Gallery

- Annual Scientific Session and Related Events

- Chapter Meetings

- Live Meetings

- Live Meetings - International

- Webinars - Live

- Webinars - OnDemand

- Certificates and Certifications

- ACC Accreditation Services

- ACC Quality Improvement for Institutions Program

- CardioSmart

- National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR)

- Advocacy at the ACC

- Cardiology as a Career Path

- Cardiology Careers

- Cardiovascular Buyers Guide

- Clinical Solutions

- Clinician Well-Being Portal

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Innovation Program

- Mobile and Web Apps

A 52-Year-Old Man With Atherosclerosis

A 52-year-old executive was referred to our clinic for risk factor management after undergoing coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) as part of an Executive Physical. He has no history of coronary artery disease and exercises regularly without experiencing anginal symptoms.

His family history is notable for a myocardial infarction (MI) in his father at the age of 52 years. He is a lifelong non-smoker. He does not take medications.

His blood pressure was 110/75. His exam was notable for being overweight with a BMI of 27, but was otherwise unremarkable.

His total cholesterol is 206 mg/dL, HDL-C is 46 mg/dL, triglycerides are 178 mg/dL, calculated LDL-C is 124 mg/dL, and non HDL-C is 160 mg/dL. His fasting glucose is 86 mg/dL. His Hgb A1c is 5.6%.

His 10-year risk based on the 2013 ACC/AHA pooled ASCVD risk estimator is 3.7%.

His coronary artery calcium (CAC) score is 120, which places him in the 87th percentile for his age, gender, and ethnicity.

His coronary CTA shows the following in the proximal LAD:

In addition to maximizing therapeutic lifestyle changes (exercise, weight loss), what is the next step in this patient’s management?

- A. There is nothing more to do since his estimated 10-year risk is low.

- B. Maximize risk factor modification by starting a low-dose aspirin and statin therapy.

- C. Pursue stress testing.

- D. Pursue coronary catheterization.

- E. B and C.

Show Answer

The correct answer is: B. Maximize risk factor modification by starting a low-dose aspirin and statin therapy.

Atherosclerosis is necessary for nearly all coronary events. The development of atherosclerosis is multifactorial. There is significant heterogeneity in the contribution of common traditional modifiable risk factors including apolipoprotein B (apoB)-containing lipoproteins, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and sedentary lifestyle to atherogenesis. 1 In participants from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) without atherosclerosis as measured by coronary artery calcium (CAC), even the presence of multiple modifiable risk factors was associated with low event rates (3.1%). In contrast, in those with elevated CAC and no modifiable risk factors, the event rates were significantly higher at nearly 11%. 1

While risk estimators are improving in accuracy, 2,3 the presence of subclinical atherosclerosis (primarily by CAC) has consistently been an additive predictor of coronary events in individuals and further discriminates between those at higher and lower risk for events. 4-6 The case patient is at elevated risk because of the burden of subclinical atherosclerosis and, therefore, answer choice A is incorrect.

The recent 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines on cholesterol treatment take a risk-based approach to recommendations for statin therapy. 7 The patient in this case has a low estimated 10-year risk at 3.7%. The current guidelines suggest a risk discussion in this case based on the patient's family history of premature coronary heart disease (CHD). Subclinical atherosclerosis imaging by CAC scanning can help with this discussion. 8

Recently, eight-year follow-up from the Dallas Heart Study showed that among participants with a family history of MI, those without CAC experienced a significantly lower CHD event rate of 1.9% compared to 8.8% in those with any CAC. 9 The case patient has a CAC score >100 that places him above the 75th percentile for his age, gender, and ethnicity. We would recommend moderate- or high-intensity statin therapy during a risk discussion based on an estimated 10-year event rate that exceeds 7.5%. Furthermore, recent data support the use of aspirin in those with CAC >100. Therefore, answer choice B is the correct answer.

Subclinical atherosclerosis imaging with CAC scanning has been endorsed by several committees to assist with risk assessment. The 2010 ACC/AHA risk assessment guidelines gave CAC scanning a IIA recommendation in those deemed to be at intermediate risk for CHD events. 11 In the 2010 appropriate use criteria for cardiac CT endorsed by multiple societies, CAC scanning was deemed appropriate among low-risk asymptomatic patients with a family history of premature CHD in addition to those at intermediate risk. 12 Most recently, the 2013 ACC/AHA risk assessment guidelines gave CAC scoring a IIB recommendation. Specifically, the committee suggests that if there is uncertainty about whether to start pharmacotherapy after risk estimation, then CAC scoring could be considered. 2

An important consideration in this case is the use of CTA to identify subclinical atherosclerosis. While coronary CTA is a more specific and sensitive test for atherosclerosis, there is no evidence that CTA adds significantly to CAC scanning in an asymptomatic population. However, CTA may identify vulnerable features of plaque that are not picked up by CAC scanning, such as those present in the case example. 13 Motoyama et al. identified high-risk features for acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in asymptomatic subjects on CTA including positive remodeling and low-attenuation plaque, in addition to spotty calcification in those presenting with ACS. 14,15 A small preliminary study suggested a benefit of statin therapy on plaque volume and the amount of low-attenuation plaque. 16 The role of CTA in asymptomatic, primary prevention patients is actively under investigation. 17 The benefits of CTA should be weighed against exposure to contrast, expense, and the need to train readers. With rapidly advancing technology, CTAs can now be performed with the equivalent radiation exposure of two mammograms. 18

Currently, the use of CTA is useful in appropriate symptomatic patients, particularly in chest pain protocols in the emergency department. 19 Many of these patients have mild or moderate, non-obstructive atherosclerosis that is unlikely to be the cause of their presenting symptoms, but should be managed with aggressive preventive therapies. In symptomatic patients from the CONFIRM registry, there is an increased hazard of mortality in those with non-obstructive atherosclerosis on CTA compared to those without atherosclerosis on CTA. 20

Some have advocated for stress testing in those with CAC scores > 400; however, the patient in this case does not meet this criteria. 21,22 Therefore, answer choices C and D are incorrect as the patient is asymptomatic.

- Silverman MG, Blaha MJ, Krumholz HM, et al. Impact of coronary artery calcium on coronary heart disease events in individuals at the extremes of traditional risk factor burden: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2013 Dec 13 [Epub ahead of print].

- Goff DC, Jr., Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:2935-59.

- Muntner P, Colantonio LD, Cushman M, et al. Validation of the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease Pooled Cohort risk equations. JAMA 2014;311:1406-15.

- Polonsky TS, McClelland RL, Jorgensen NW, et al. Coronary artery calcium score and risk classification for coronary heart disease prediction. JAMA 2010;303:1610-6.

- Erbel R, Möhlenkamp S, Moebus S, et al. Coronary risk stratification, discrimination, and reclassification improvement based on quantification of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis: the Heinz Nixdorf Recall study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:1397-406.

- Yeboah J, McClelland RL, Polonsky TS, et al. Comparison of novel risk markers for improvement in cardiovascular risk assessment in intermediate-risk individuals. JAMA 2012;308:788-95.

- Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:2889–934.

- Nasir K, Budoff MJ, Wong ND, et al. Family history of premature coronary heart disease and coronary artery calcification: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation 2007;116:619-26.

- Paixao AR, Berry JD, Neeland IJ, et al. Coronary artery calcification and family history of myocardial infarction in the Dallas Heart Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging . 2014 June [Epub ahead of print].

- Miedema MD, Duprez DA, Misialek JR, et al. Use of coronary artery calcium testing to guide aspirin utilization for primary prevention: estimates from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2014;7:453-60.

- Greenland P, Alpert JS, Beller GA, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:e50-103.

- Taylor AJ, Cerqueira M, Hodgson JM, et al. ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SCMR 2010 appropriate use criteria for cardiac computed tomography. a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:1864-94.

- Voros S, Rinehart S, Qian Z, et al. Coronary atherosclerosis imaging by coronary CT angiography: current status, correlation with intravascular interrogation and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4:537-48.

- Motoyama S, Sarai M, Harigaya H, et al. Computed tomographic angiography characteristics of atherosclerotic plaques subsequently resulting in acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:49-57.

- Motoyama S, Kondo T, Sarai M et al. Multislice computed tomographic characteristics of coronary lesions in acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:319-26.

- Inoue K, Motoyama S, Sarai M, et al. Serial coronary CT angiography-verified changes in plaque characteristics as an end point: evaluation of effect of statin intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2010;3:691-8.

- U.S. National Institutes of Health.Detection of Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Asymptomatic Individuals (Decide CTA). (ClinicalTrials.gov website). 2009-2014. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00862056?term=DECIDE-CTA . Accessed June 22, 2014.

- Achenbach S, Marwan M, Ropers, D et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography with a consistent dose below 1 mSv using prospectively electrocardiogram-triggered high-pitch spiral acquisition. Eur Heart J 2010;31:340-6.

- Hoffmann U, Truong QA, Schoenfeld DA, et al. Coronary CT angiography versus standard evaluation in acute chest pain. N Engl J Med 2012;367:299-308.

- Min JK, Dunning A, Lin FY, et al. Age- and sex-related differences in all-cause mortality risk based on coronary computed tomography angiography findings results from the International Multicenter CONFIRM (Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: An International Multicenter Registry) of 23,854 patients without known coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:849-60.

- Hendel RC, Berman DS, Di Carli MF, et al. ACCF/ASNC/ACR/AHA/ASE/SCCT/SCMR/SNM 2009 appropriate use criteria for cardiac radionuclide imaging: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:2201-29.

- Berman DS, Hachamovitch R, Shaw LJ, et al. Roles of nuclear cardiology, cardiac computed tomography, and cardiac magnetic resonance: Noninvasive risk stratification and a conceptual framework for the selection of noninvasive imaging tests in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease. J Nucl Med 2006;47:1107-18.

You must be logged in to save to your library.

Jacc journals on acc.org.

- JACC: Advances

- JACC: Basic to Translational Science

- JACC: CardioOncology

- JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging

- JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions

- JACC: Case Reports

- JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology

- JACC: Heart Failure

- Current Members

- Campaign for the Future

- Become a Member

- Renew Your Membership

- Member Benefits and Resources

- Member Sections

- ACC Member Directory

- ACC Innovation Program

- Our Strategic Direction

- Our History

- Our Bylaws and Code of Ethics

- Leadership and Governance

- Annual Report

- Industry Relations

- Support the ACC

- Jobs at the ACC

- Press Releases

- Social Media

- Book Our Conference Center

Clinical Topics

- Chronic Angina

- Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology

- Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease

- Hypertriglyceridemia

- Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention

- Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism

Latest in Cardiology

Education and meetings.

- Online Learning Catalog

- Products and Resources

- Annual Scientific Session

Tools and Practice Support

- Quality Improvement for Institutions

- Accreditation Services

- Practice Solutions

Heart House

- 2400 N St. NW

- Washington , DC 20037

- Contact Member Care

- Phone: 1-202-375-6000

- Toll Free: 1-800-253-4636

- Fax: 1-202-375-6842

- Media Center

- Advertising & Sponsorship Policy

- Clinical Content Disclaimer

- Editorial Board

- Privacy Policy

- Registered User Agreement

- Terms of Service

- Cookie Policy

© 2024 American College of Cardiology Foundation. All rights reserved.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Volume 2024, Issue 5, May 2024 (In Progress)

- Volume 2024, Issue 4, April 2024

- Bariatric Surgery

- Breast Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Colorectal Surgery

- Colorectal Surgery, Upper GI Surgery

- Gynaecology

- Hepatobiliary Surgery

- Interventional Radiology

- Neurosurgery

- Ophthalmology

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Otorhinolaryngology - Head & Neck Surgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Plastic Surgery

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma & Orthopaedic Surgery

- Upper GI Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Reasons to Submit

- About Journal of Surgical Case Reports

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, conflicts of interest, giant coronary artery aneurysm occluded completely by a thrombus.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Shinichi Ishida, Genki Maeno, Aoi Kato, Yuson Wada, Hideyuki Okawa, Takahisa Sakurai, Toshimichi Nonaka, Giant coronary artery aneurysm occluded completely by a thrombus, Journal of Surgical Case Reports , Volume 2024, Issue 5, May 2024, rjae355, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae355

- Permissions Icon Permissions

A coronary artery aneurysm is an uncommon vascular disorder, and it can be a life-threatening disease when associated with rupture or an embolism. A 52-year-old man was found to have a 50-mm coronary artery aneurysm at the right coronary artery, and the aneurysm was completely occluded by a thrombus. He had no symptoms after arriving at our hospital, and his hemodynamics was stable. Therefore, initially, we administered anticoagulation therapy involving heparin. After therapy, the distal coronary artery was detected when the thrombus dissolved, and elective surgery was planned. Coronary artery bypass grafting, ligation of the inflow and outflow vessels, and resection of the aneurysm were performed. Early anticoagulation therapy and surgical aneurysm resection were effective for treating the completely occluded coronary artery aneurysm. We herein report this rare case of a giant coronary artery aneurysm occluded completely by a thrombus and treated successfully by anticoagulation therapy and surgical aneurysm resection.

A coronary artery aneurysm (CAA) is an uncommon vascular disorder, and it can be a life-threatening disease when associated with rupture or an embolism [ 1 ]. In particular, a giant CAA that >20 mm is very rare. Moreover, a CAA completely occluded by a thrombus is even more uncommon. We herein present a rare case of a patient with a 50-mm CAA at the right coronary artery (RCA), which was completely occluded by a thrombus at detection.

Case report:

A 52-year-old man with transient ischemic attack was transferred to our hospital. He had a history of hypertension and dyslipidemia. He was conscious and had no particular symptoms after arriving at our hospital; however, an electrocardiogram showed ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, aVF, and V1–4. Enhanced computed tomography revealed a giant CAA at the RCA ( Fig. 1 ). The aneurysm measured 50 mm in diameter and was completely occluded by a thrombus. Additionally, the coronary artery distal from the CAA did not show contrast. Emergency coronary angiography was performed. The RCA was occluded at segment #2 proximal to the CAA, and the CAA did not show contrast ( Fig. 2A ); however, the artery distal to the CAA showed contrast via a collateral artery from the left circumflex artery ( Fig. 2B ). Anticoagulation therapy involving intravenous heparin was started. After several hours, the ST-segment elevation disappeared quickly, and there were no particular symptoms. The creatine kinase level spiked to a maximum of 1475 IU/L, which then decreased to 432 IU/L on the next day. Four days after starting therapy, enhanced computed tomography and coronary angiography were performed again. They showed slight contrast in the CAA and the distal coronary artery ( Fig. 3 ). Thus, surgery was performed to prevent the CAA from rupturing.

Enhanced computed tomography shows a giant coronary artery aneurysm (arrow) at the right coronary artery, which is occluded completely by a thrombus.

(A) Coronary angiography shows occlusion of the right coronary artery proximal to the aneurysm (arrow). (B) The artery distal to the aneurysm shows contrast via a collateral artery from the left circumflex artery (arrow).

A second coronary artery angiography shows slight contrast in the aneurysm (arrow head) and in the distal coronary artery (arrow head).