- Get started with computers

- Learn Microsoft Office

- Apply for a job

- Improve my work skills

- Design nice-looking docs

- Getting Started

- Smartphones & Tablets

- Typing Tutorial

- Online Learning

- Basic Internet Skills

- Online Safety

- Social Media

- Zoom Basics

- Google Docs

- Google Sheets

- Career Planning

- Resume Writing

- Cover Letters

- Job Search and Networking

- Business Communication

- Entrepreneurship 101

- Careers without College

- Job Hunt for Today

- 3D Printing

- Freelancing 101

- Personal Finance

- Sharing Economy

- Decision-Making

- Graphic Design

- Photography

- Image Editing

- Learning WordPress

- Language Learning

- Critical Thinking

- For Educators

- Translations

- Staff Picks

- English expand_more expand_less

Critical Thinking and Decision-Making - Logical Fallacies

Critical thinking and decision-making -, logical fallacies, critical thinking and decision-making logical fallacies.

Critical Thinking and Decision-Making: Logical Fallacies

Lesson 7: logical fallacies.

/en/problem-solving-and-decision-making/how-critical-thinking-can-change-the-game/content/

Logical fallacies

If you think about it, vegetables are bad for you. I mean, after all, the dinosaurs ate plants, and look at what happened to them...

Let's pause for a moment: That argument was pretty ridiculous. And that's because it contained a logical fallacy .

A logical fallacy is any kind of error in reasoning that renders an argument invalid . They can involve distorting or manipulating facts, drawing false conclusions, or distracting you from the issue at hand. In theory, it seems like they'd be pretty easy to spot, but this isn't always the case.

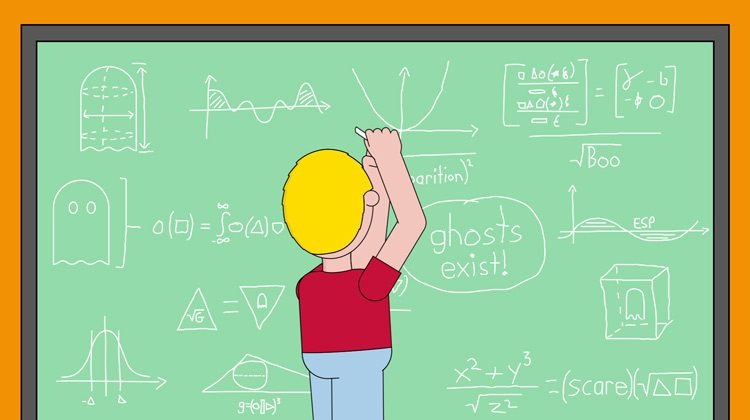

Watch the video below to learn more about logical fallacies.

Sometimes logical fallacies are intentionally used to try and win a debate. In these cases, they're often presented by the speaker with a certain level of confidence . And in doing so, they're more persuasive : If they sound like they know what they're talking about, we're more likely to believe them, even if their stance doesn't make complete logical sense.

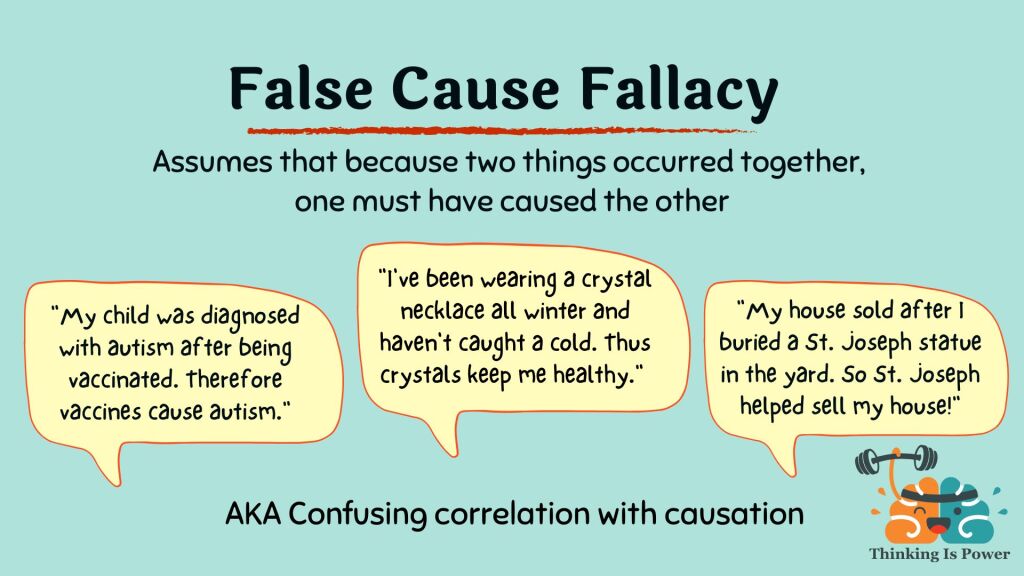

False cause

One common logical fallacy is the false cause . This is when someone incorrectly identifies the cause of something. In my argument above, I stated that dinosaurs became extinct because they ate vegetables. While these two things did happen, a diet of vegetables was not the cause of their extinction.

Maybe you've heard false cause more commonly represented by the phrase "correlation does not equal causation ", meaning that just because two things occurred around the same time, it doesn't necessarily mean that one caused the other.

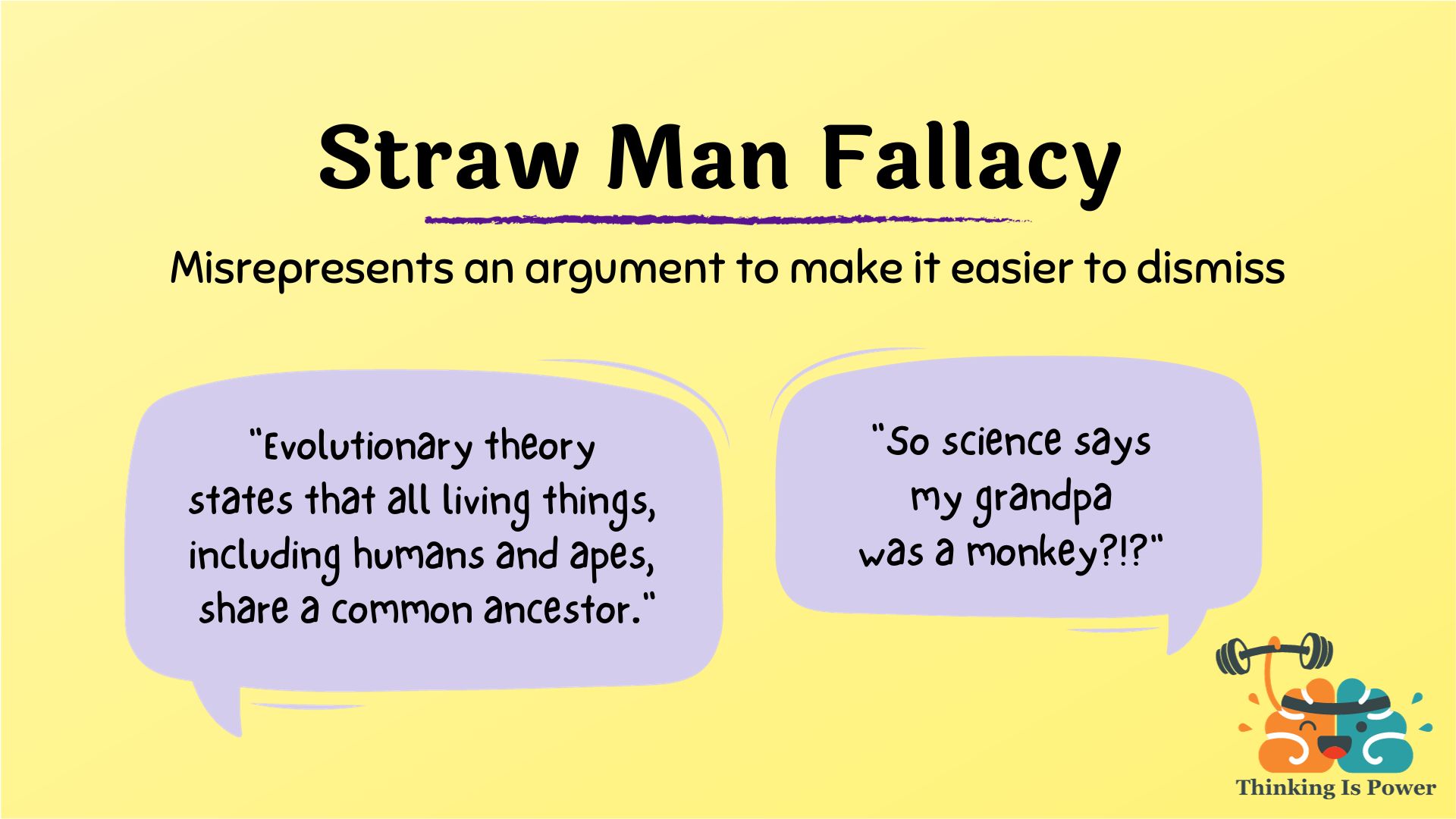

A straw man is when someone takes an argument and misrepresents it so that it's easier to attack . For example, let's say Callie is advocating that sporks should be the new standard for silverware because they're more efficient. Madeline responds that she's shocked Callie would want to outlaw spoons and forks, and put millions out of work at the fork and spoon factories.

A straw man is frequently used in politics in an effort to discredit another politician's views on a particular issue.

Begging the question

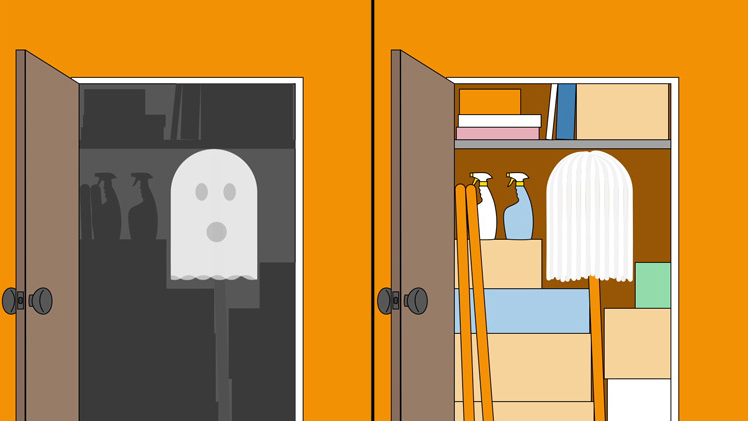

Begging the question is a type of circular argument where someone includes the conclusion as a part of their reasoning. For example, George says, “Ghosts exist because I saw a ghost in my closet!"

George concluded that “ghosts exist”. His premise also assumed that ghosts exist. Rather than assuming that ghosts exist from the outset, George should have used evidence and reasoning to try and prove that they exist.

Since George assumed that ghosts exist, he was less likely to see other explanations for what he saw. Maybe the ghost was nothing more than a mop!

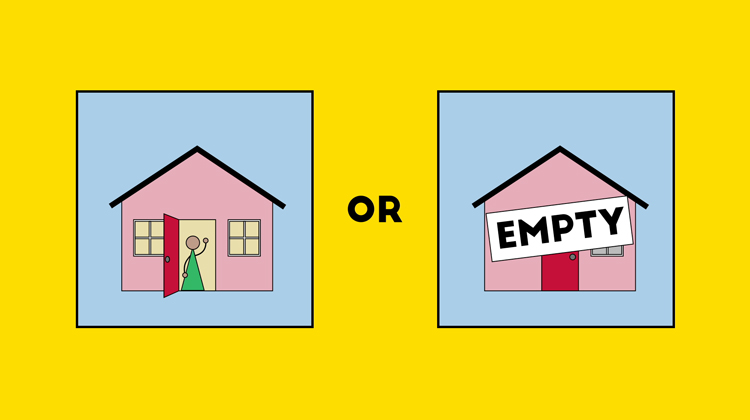

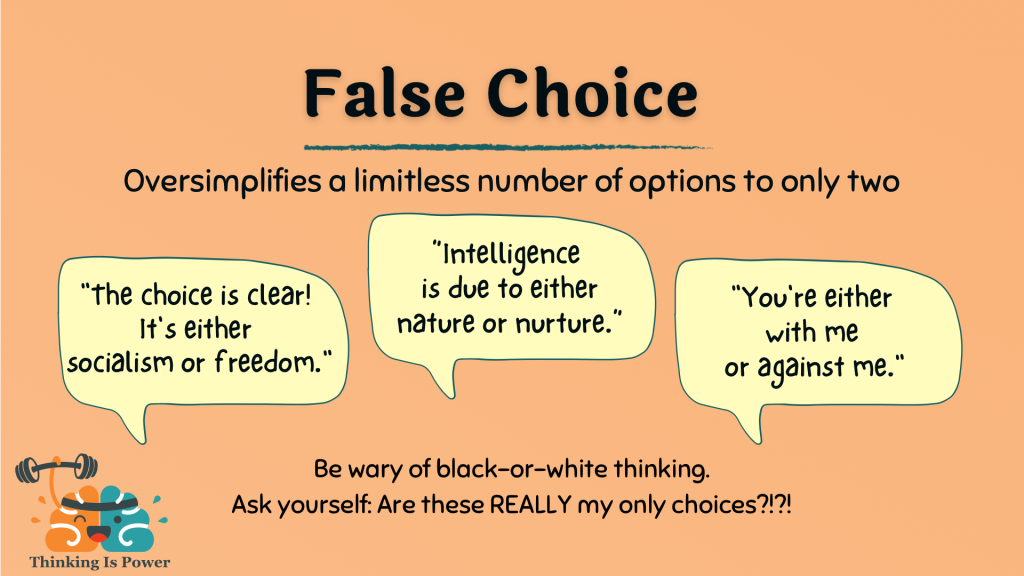

False dilemma

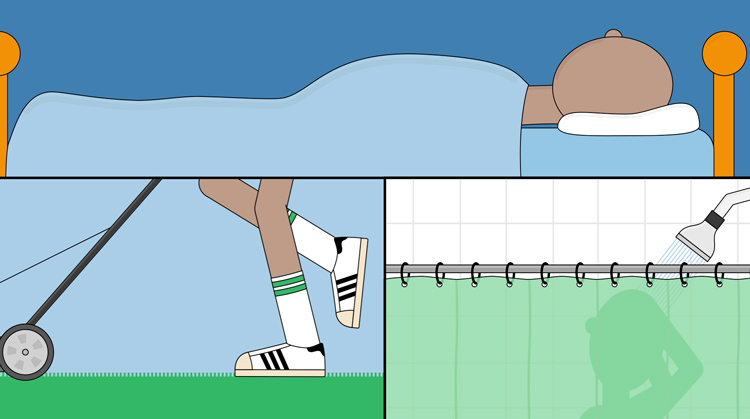

The false dilemma (or false dichotomy) is a logical fallacy where a situation is presented as being an either/or option when, in reality, there are more possible options available than just the chosen two. Here's an example: Rebecca rings the doorbell but Ethan doesn't answer. She then thinks, "Oh, Ethan must not be home."

Rebecca posits that either Ethan answers the door or he isn't home. In reality, he could be sleeping, doing some work in the backyard, or taking a shower.

Most logical fallacies can be spotted by thinking critically . Make sure to ask questions: Is logic at work here or is it simply rhetoric? Does their "proof" actually lead to the conclusion they're proposing? By applying critical thinking, you'll be able to detect logical fallacies in the world around you and prevent yourself from using them as well.

Logical Fallacies (Common List + 21 Examples)

We all talk, argue, and make choices every day. Sometimes, the things we or others say can be a bit off or don't make complete sense. These mistakes in our thinking can make our points weaker or even wrong.

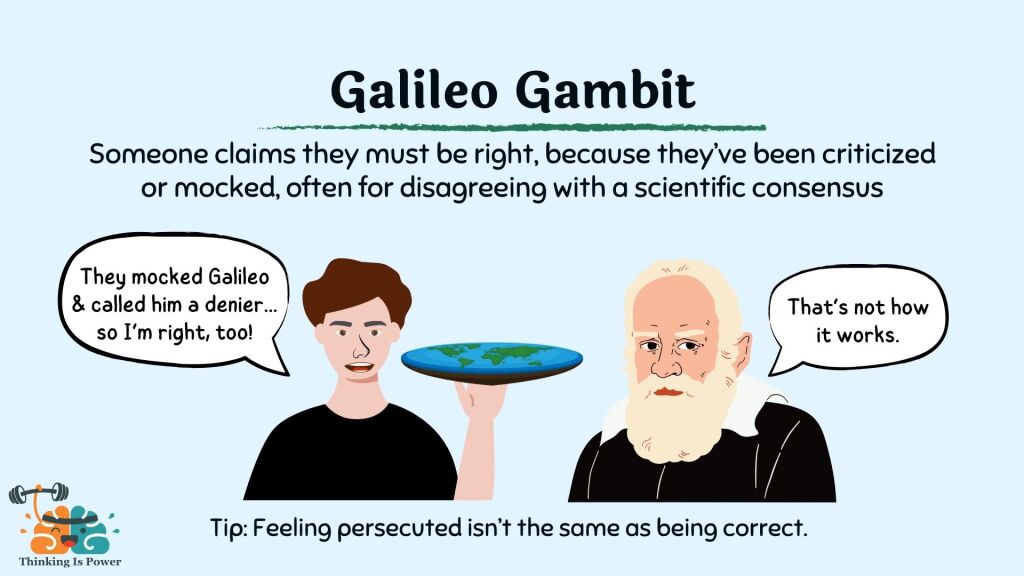

Logical fallacies are mistakes in how we reason or argue a point. They can be small mix-ups or times when someone tries to trick us on purpose.

By learning about these errors, you can better spot them when you hear or read them. As you read on, you'll learn more about these tricky mistakes and how to steer clear of them.

Introduction to Logical Fallacies

Imagine you're piecing together a puzzle. Each piece needs to fit perfectly for the whole picture to make sense. In conversations and debates, our arguments are like those puzzle pieces. They need to fit well together, making our points clear and strong.

However, sometimes, a piece might be bent or out of place, making the whole picture a bit off. That's how logical fallacies work in our discussions. They're like those misfit puzzle pieces that can make our whole argument seem less clear or even wrong.

Logical fallacies, in simple terms, are errors or mistakes in our reasoning. You might come across them when you're chatting with a friend, watching the news, or even reading a book.

Some of these mistakes happen because we don't know better, while others might be used intentionally to mislead or persuade.

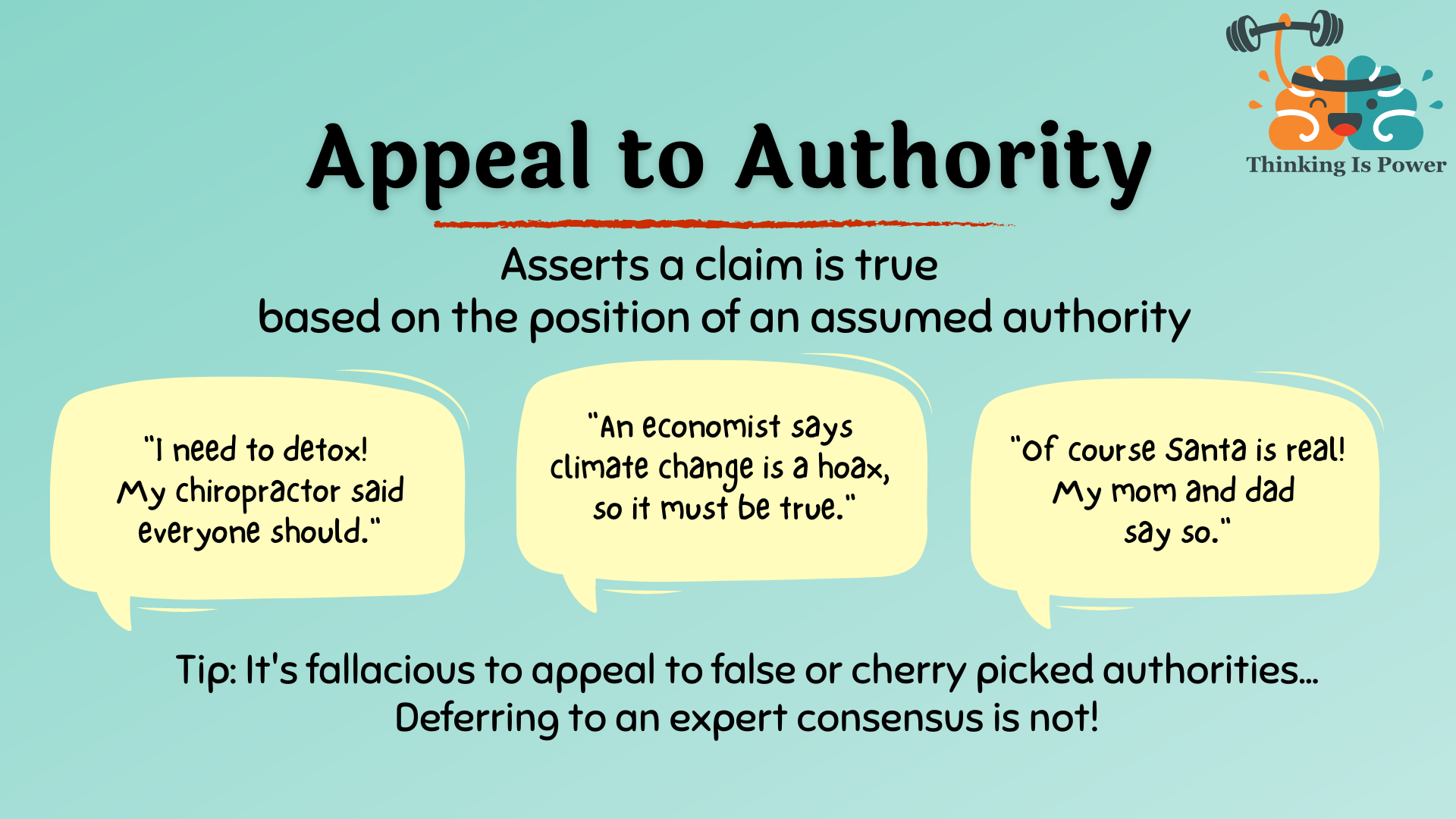

Let's say you're discussing which ice cream flavor is the best. Your friend might say, "Well, my grandma thinks vanilla is the best, so it must be!" This kind of reasoning isn't strong because one person's opinion, even if it's your grandma, doesn't prove a point for everyone.

This is an example of a fallacy called appeal to authority . It’s just one of the many logical fallacies you'll come across.

When we talk about logical fallacies, we often categorize them into two main types: informal and formal.

Informal Fallacies

Think of these as mistakes or errors in reasoning that arise from the content of the arguments rather than the structure.

They're called 'informal' because they deal with everyday language and common conversations. These fallacies often involve statements that might sound true initially, but upon closer inspection, they don't hold up.

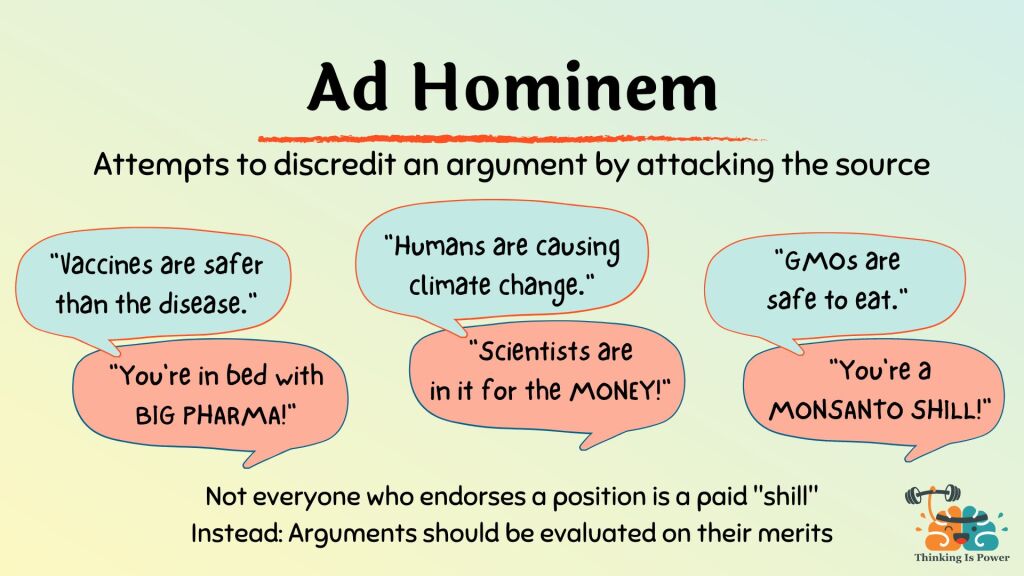

Examples include the ad hominem argument or fallacy, where someone attacks the person rather than their argument, or the appeal to authority , where someone assumes a statement is true because an expert or authority says so.

Formal Fallacies

These are a bit more, well, formal. They deal with errors in the structure or form of an argument.

It doesn't matter what the content of the argument is; if it's structured wrongly, it's a formal fallacy. You can think of these like a math problem: if you don't follow the right steps, you won't get the right answer.

An example of a formal fallacy is the affirming the consequent , which goes like this: "If it rains, the ground will be wet. The ground is wet. Therefore, it rained." While the statements might sound logical, the conclusion doesn't necessarily follow from the premises.

In a nutshell, while informal fallacies stem from the content of arguments and often arise in casual conversations, formal fallacies are all about structure, and they can be spotted regardless of the topic being discussed.

All fallacies can be proven wrong because they have flawed reasoning or insufficient supporting evidence, make an irrelevant point, or don't have an actual argument. Even if it seems like they come to a logical conclusion, they do so in an illogical way.

Common Logical Fallacies

Let's look at some of the most common logical fallacy examples.

Ad Hoc Fallacy

This is a fallacy where someone makes up a reason on the spot to support their argument, even if it doesn't make sense.

Picture this: you're debating about climate change and its causes. Your friend, instead of using scientific evidence, says, "Well, it's just a cycle the Earth goes through. My grandpa said so!" This is an Ad Hoc Fallacy. The reason is made up on the spot and doesn't hold up to scrutiny.

Ad Hominem Fallacy

This is when someone attacks the person instead of their argument.

Imagine you're chatting about which game is the best, and instead of giving reasons, someone says, "Well, you wear glasses so that you wouldn’t understand!" That's not a good reason, right?

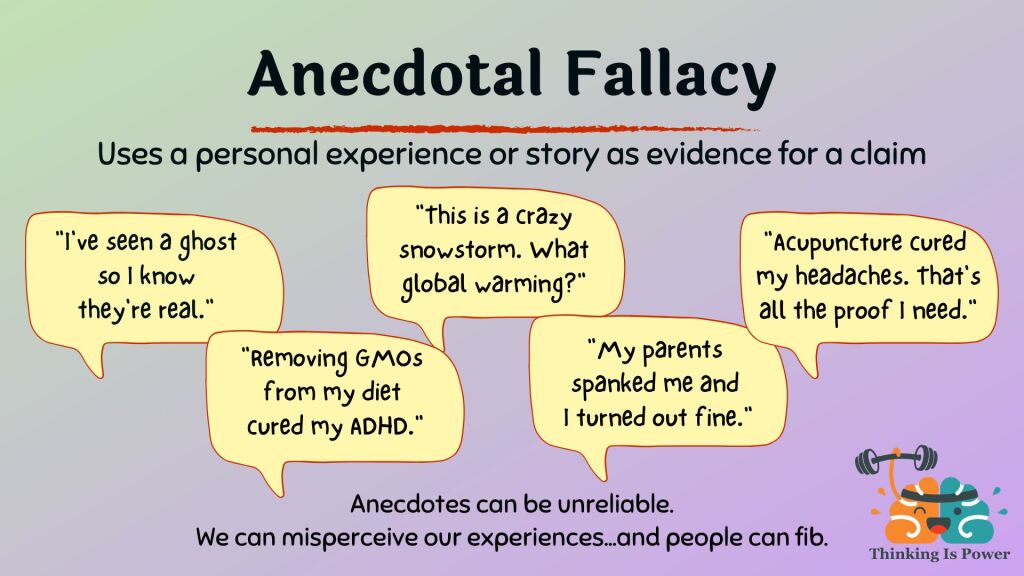

Anecdotal Fallacy

An Anecdotal Fallacy occurs when someone relies on personal experiences or individual cases as evidence for a general claim, overlooking larger and more reliable data.

Appeal to Pity

An Appeal to Pity Fallacy is an argument that attempts to win you over by eliciting your sympathy or compassion rather than relying on logical reasoning.

Straw Man Fallacy

Here, someone changes or oversimplifies another person's argument to make it easier to attack. It's like building a weak version of the original point and then knocking it down.

Person A: "I think we should have more regulations on industrial pollution to protect the environment." Person B: "Why do you want to destroy jobs and hurt our economy by shutting down all industries?" In this case, Person A never said they wanted to shut down all industries, but Person B set up a "straw man" version of Person A's argument to knock it down.

Ecological Fallacy

An Ecological Fallacy occurs when you make conclusions about individual members of a group based only on the characteristics of the group as a whole.

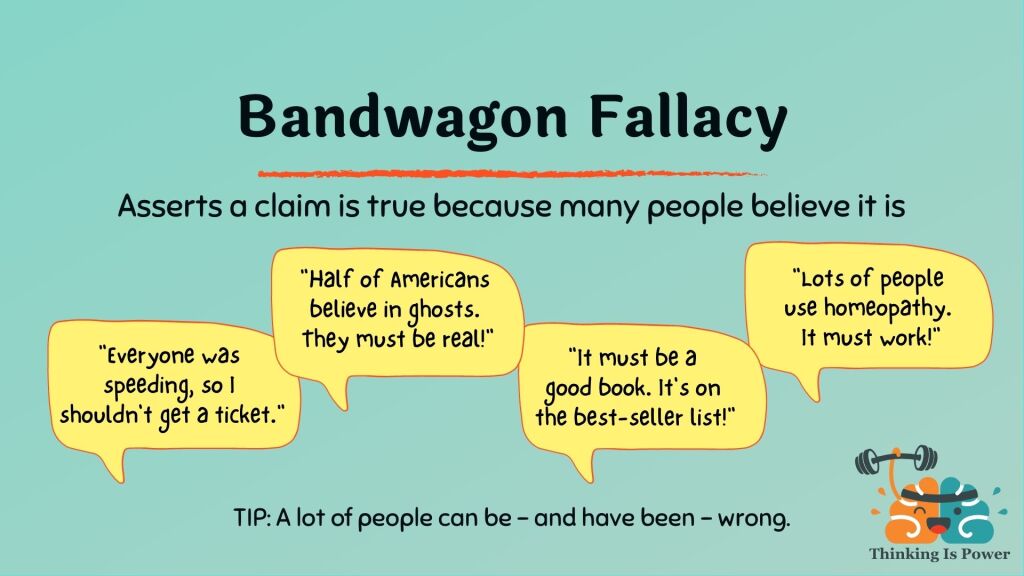

- Bandwagon Fallacy

This one's about popularity. Just because many people believe something doesn't mean it's true.

Remember when everyone believed the earth was flat? Being popular doesn't always mean being right.

Loaded Question

A loaded question fallacy is a trick question that contains an assumption or constraint that unfairly influences the answer, leading you toward a particular conclusion.

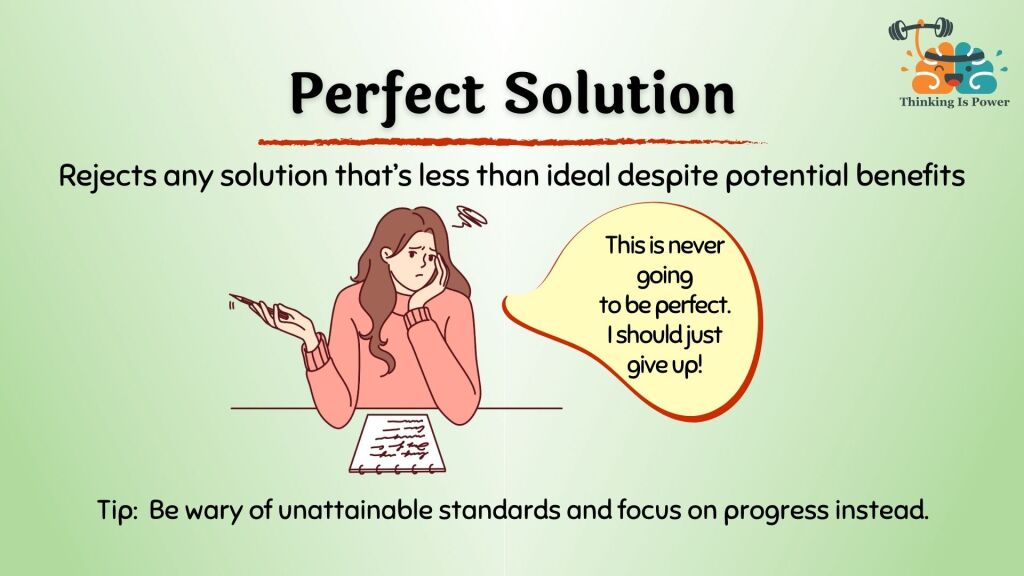

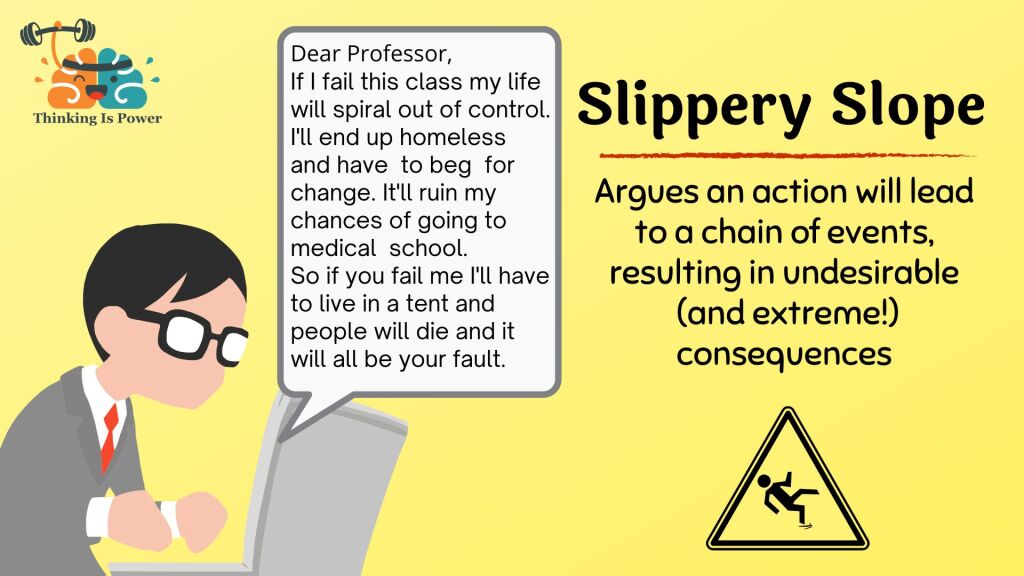

Slippery Slope Fallacy

This is when someone says that if one thing happens, other bad things will follow without good reasons.

Like if someone says, "If we let kids have phones, next they'll want to drive cars at 10 years old!" It's a big jump without clear logic connecting the two.

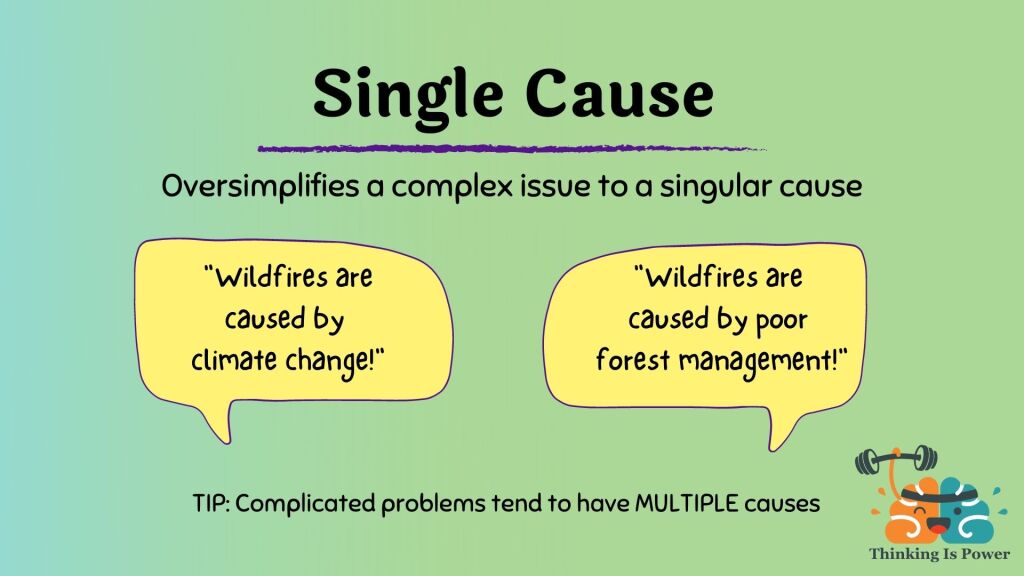

False Cause Fallacy

This is thinking one thing causes another just because they happen together.

Like believing every time you wear a certain shirt, your team wins. It's fun to think about, but the shirt probably isn't the reason for the win.

Appeal to Probability

An Appeal to Probability Fallacy is a misleading reasoning technique that assumes if something is likely, it must be certain to happen.

Appeal to Authority Fallacy

We talked about this one earlier! Just because someone famous or important believes something doesn't make it true.

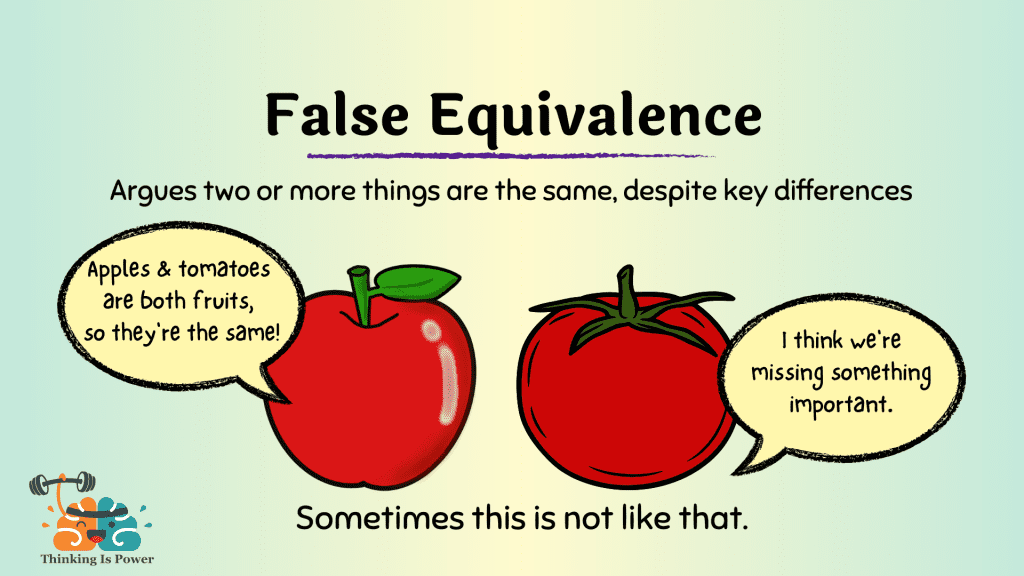

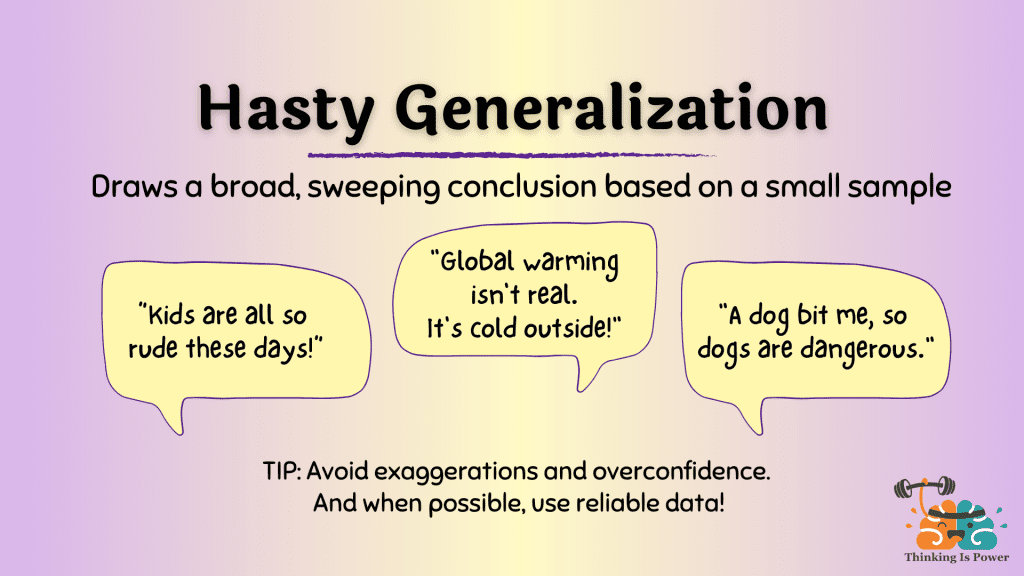

Hasty Generalization Fallacy

This is when someone makes a broad claim based on very limited evidence .

For instance, after seeing two movies with a particular actor and not liking them, you declare, "All movies with this actor are terrible."

False Dichotomy Fallacy

This fallacy occurs when someone presents only two options or solutions when more exist.

Example: "You're either with us, or you're against us." In reality, someone might be neutral or have a more nuanced opinion.

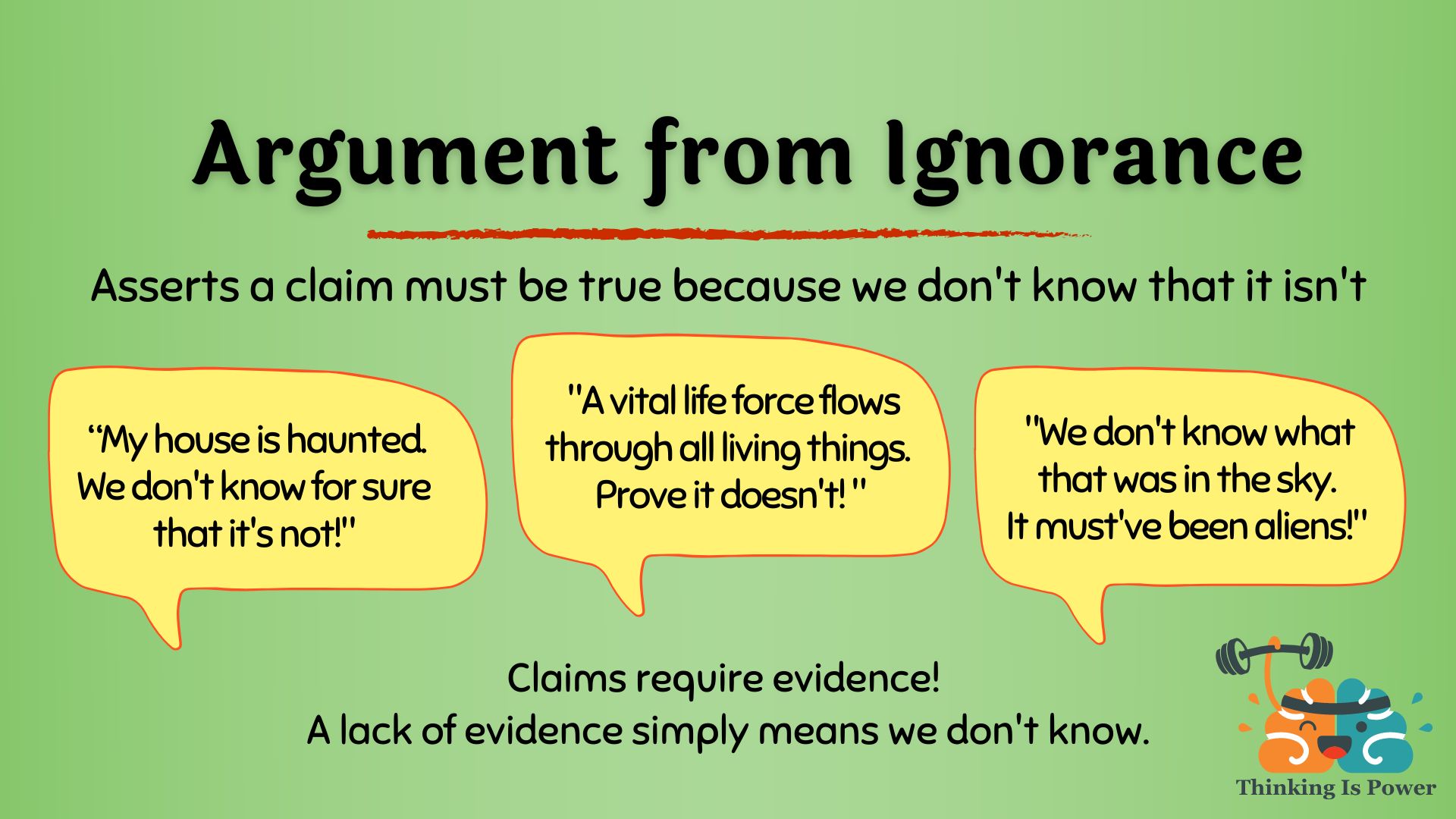

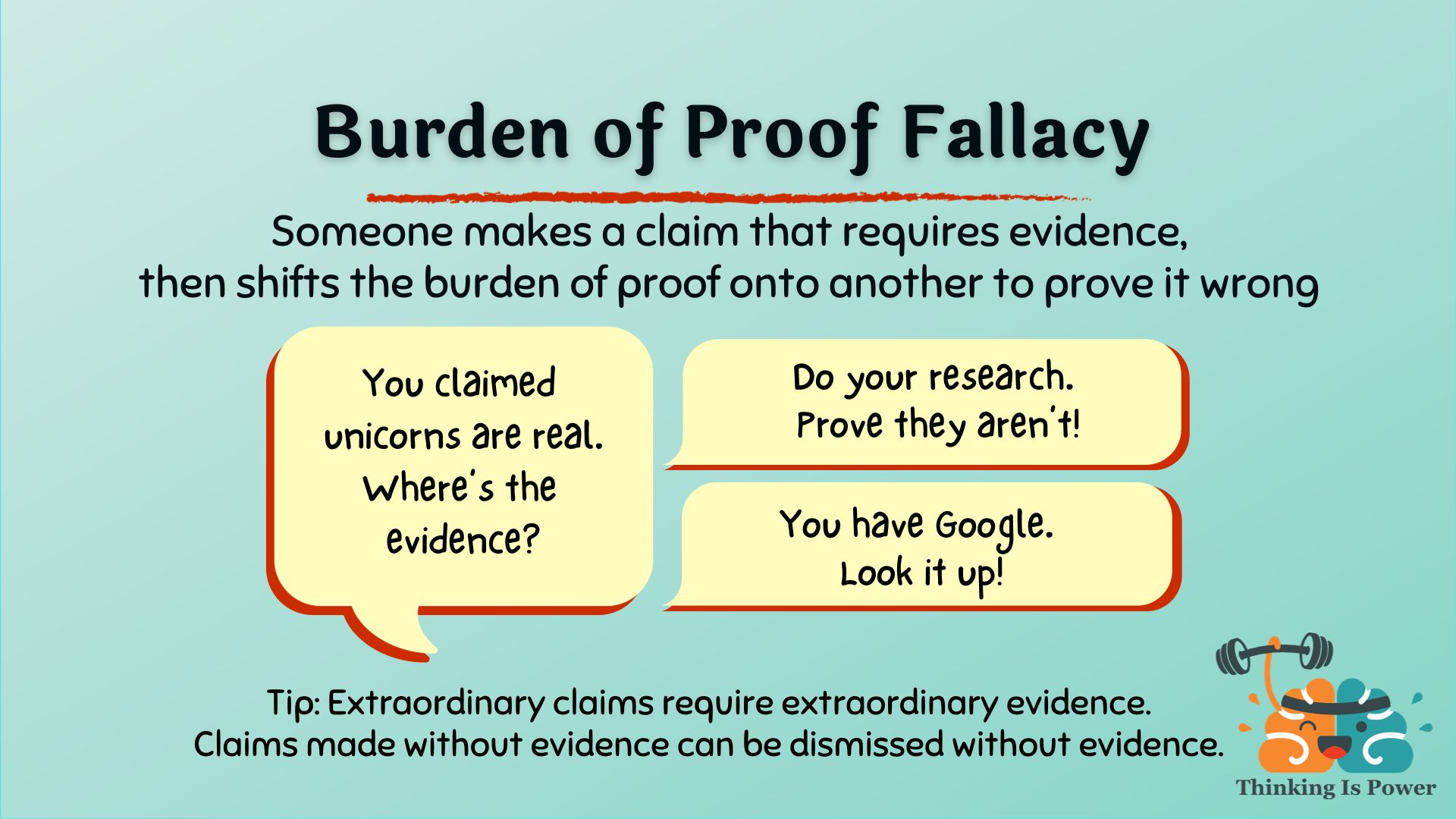

Proof Fallacy (Argument from Ignorance)

This is when someone assumes something is true because it hasn't been proven false or vice versa.

Example: "No one has ever proven that aliens don't exist, so they must be real."

Tu Quoque Fallacy

This fallacy points out hypocrisy as an argument against the claim. It's like saying, "You too!"

Example: "Why are you telling me not to smoke when you used to smoke?"

Post Hoc Fallacy ( Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc)

This fallacy assumes that if 'B' occurred after 'A', then 'A' must have caused 'B'.

Example: "I wore my lucky socks, and then passed my exam. My socks made me pass!"

No True Scotsman Fallacy

This fallacy happens when someone redefines a term to fit their own writing or argument or to exclude a counterexample.

Person A: "No Scotsman puts sugar in his porridge." Person B: "But my uncle Angus is a Scotsman, and puts sugar in his porridge." Person A: "Well, no true Scotsman puts sugar in his porridge."

Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy

This cognitive bias is when someone focuses on a subset of their data and ignores the rest to make a point.

Looking at a large set of data and only selecting the bits that support your claim, like a shooter firing randomly at a barn wall, then painting a target around the shots that are closest together.

Middle Ground Fallacy

Middle Ground is the belief that a compromise between two conflicting positions must be the truth or the best solution.

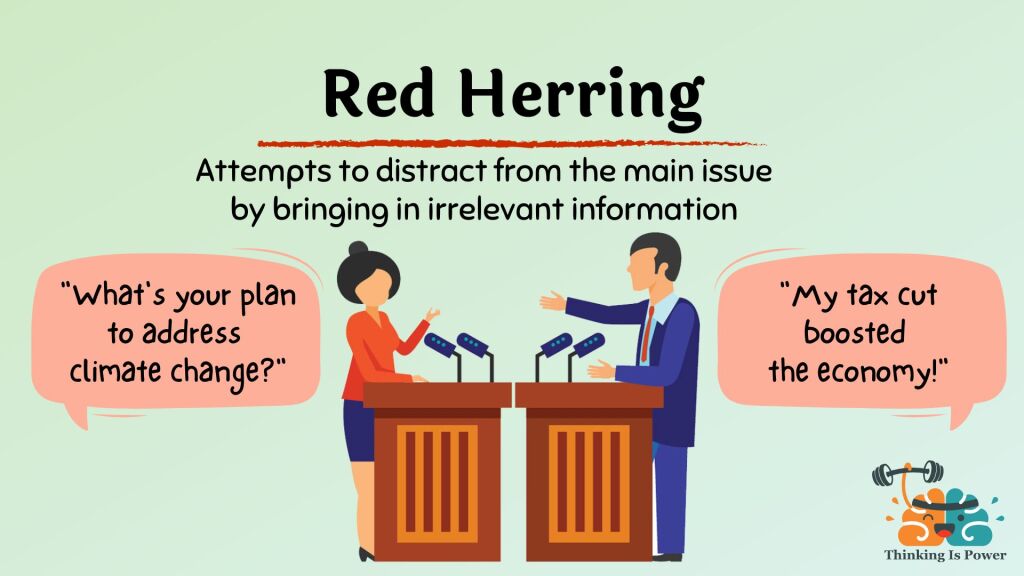

Red Herring Fallacy

This fallacy introduces an irrelevant topic to distract from the original argument.

For instance, when asked about pollution levels, a politician says, "We have some of the best parks in the country, and our citizens love spending time in nature."

False Analogy Fallacy

Any time someone says "X is like Y" to compare one thing with something else that isn't the same but does share similarities, they're making a false analogy .

For instance, saying cars and bicycles are the same because they both have wheels is an oversimplification.

Circular Reasoning Fallacy

This logical fallacy makes the mistake of using a claim to support itself . A is true because B is true.

Perhaps you've seen a commercial claiming a product is the best because so many people buy it. But when pressed on how they know so many buy it, they respond because the product is the best.

Accident Fallacy

An Accident Fallacy is the misuse of a general rule by applying it to a specific case it doesn’t properly address.

Begging the Question Fallacy

A begging-the question-fallacy occurs when the argument's conclusion is assumed in its premise. In other words, it's a form of circular reasoning where the thing you're trying to prove is already assumed to be true.

- Appeal to Ignorance

An Appeal to Ignorance Fallacy occurs when someone argues that a claim is true simply because it has not been proven false, or vice versa.

Fallacy of Composition

A fallacy of composition is the flawed reasoning that concludes what is true for individual parts must also be true for the entire group or system they belong to.

Equivocation Fallacy

An equivocation fallacy occurs when a word or phrase is used with two meanings in the same argument, leading to confusion or a misleading conclusion.

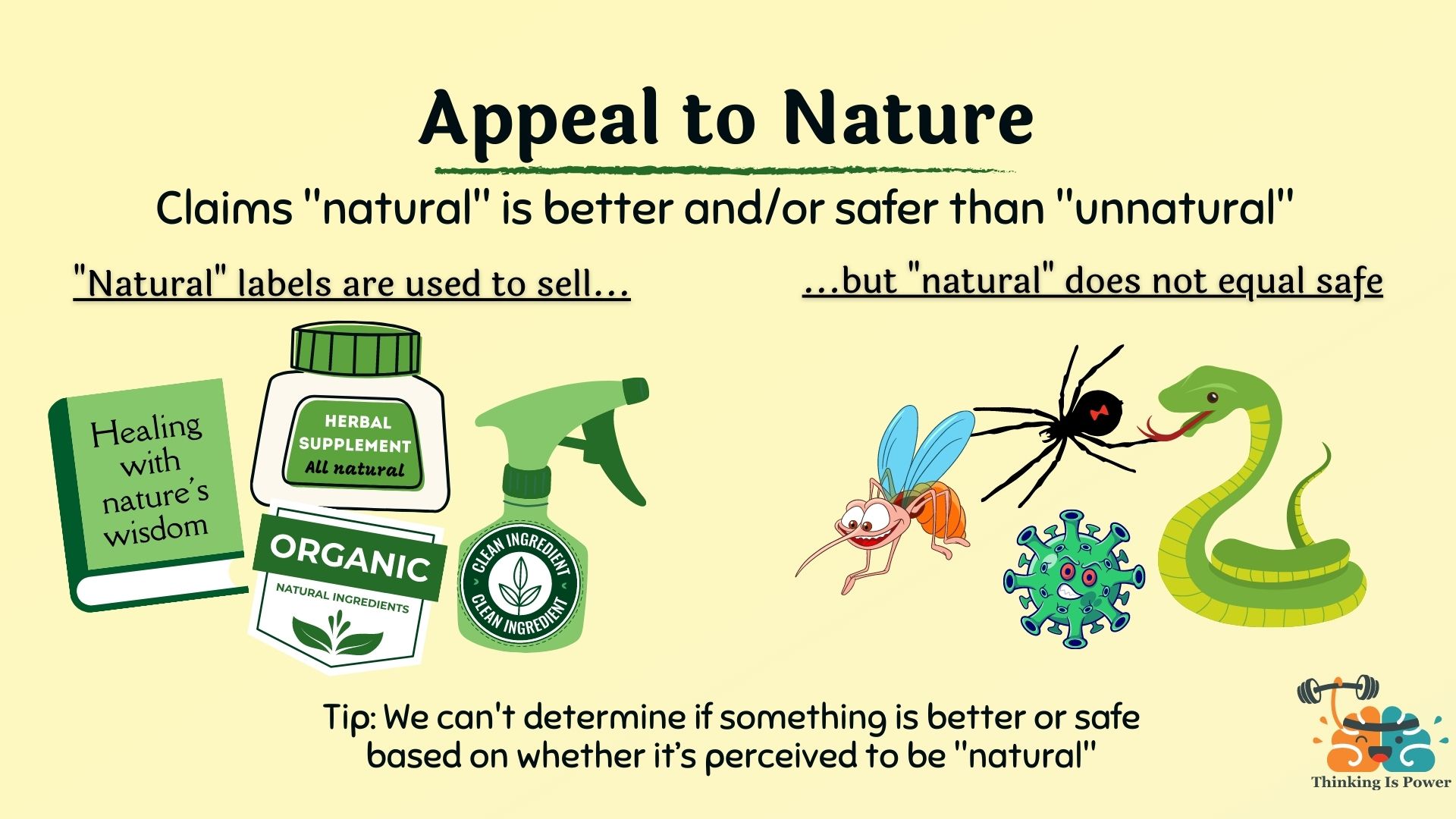

Naturalistic Fallacy

A naturalistic fallacy , also known as the appeal to nature fallacy, comes to a false conclusion by assuming that everything in nature is moral and right.

Why Do We Fall for Fallacies?

Everyone, at some point, has believed in something that turned out to be not entirely true. Just like when we believe in myths or fairy tales , there's something in our brains that can sometimes make us accept ideas without fully questioning them. This is where logical fallacies sneak in.

Firstly, our brains love shortcuts . These shortcuts, called heuristics , help us make decisions faster.

For example, if you've always had great pizza from a particular restaurant, the next time you think of pizza, your brain will likely suggest that place.

But shortcuts can also lead us astray. If someone speaks confidently, our brains might take a shortcut and believe them, even if what they're saying has mistakes.

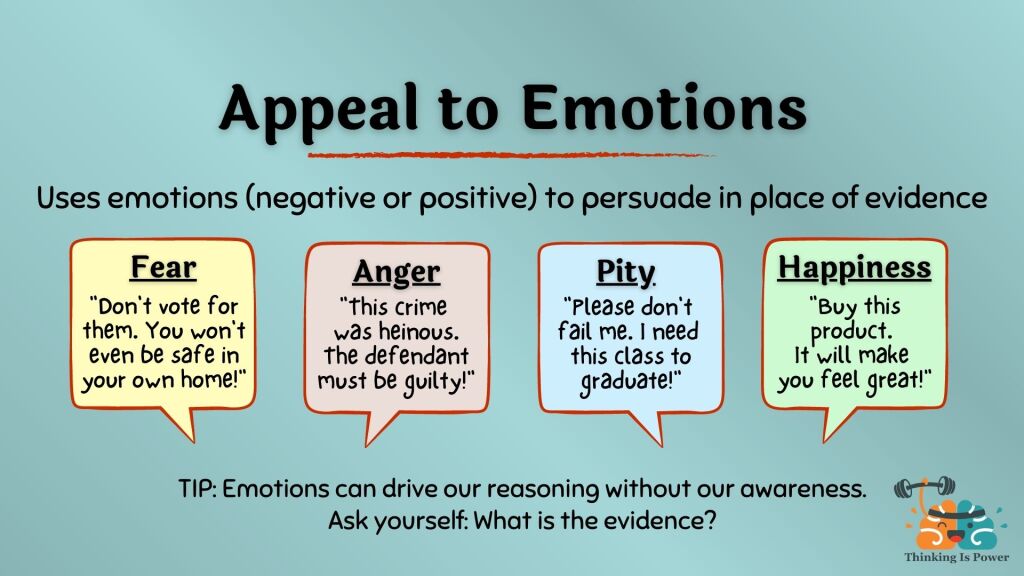

Secondly, emotions play a big role . We're humans, after all! If someone tells a sad story, we might feel so touched that we don't stop to think if the story proves the point they're making.

Or if everyone in our group believes something, we might feel the need to fit in and believe it too. This is known as groupthink , a classic trap many fall into.

Lastly, sometimes it's just easier . Questioning everything and thinking critically can be tiring. So, there are moments when we might accept something because it's simpler or because we don't want to start an argument.

But here's the good news: by learning about logical fallacies and understanding why we sometimes fall for them, you can train your brain to spot and avoid these traps.

The History of Logical Fallacies

Back in the day, long before smartphones and computers, people gathered and debated big ideas in places like Greece. One of the smartest guys around then was a man named Aristotle . He's often thought of as the first person who cared about logical thinking.

Aristotle started to notice that some arguments, even if they sounded good, had problems in them. He began to point out these mistakes and gave them names. Many of the fallacies he talked about are still recognized today!

After Aristotle, many other thinkers also became interested in how we argue and reason. They noticed that these mistakes, or fallacies, weren't just random errors. They followed patterns.

Fast forward to modern times, and this study hasn't stopped. It's become even more important.

Today, with information everywhere - on TV, the internet, and social media - it's crucial to sort out what's reliable from what's not . Teachers, writers, and even politicians study logical fallacies to communicate better and avoid misleading people.

Basic Argument Structure

A good argument is built piece by piece, ensuring each is supported by the other. Understanding how arguments are put together helps you spot when a part of the argument doesn't make sense.

At the heart of any argument are two main parts: premises and conclusions .

Think of the premises as the foundation of the argument. They're the facts or reasons you give. The conclusion is the point you're trying to make based on those reasons.

Let's use a simple example. Imagine you say:

- All dogs bark. (This is a premise.)

- Rover is a dog. (This is another premise.)

- So, Rover barks. (This is the conclusion.)

In this case, the argument is pretty solid. Both premises support the conclusion. But, if you have a shaky premise like "All cats bark," your conclusion will be off, even if it sounds right.

Sometimes, arguments have more than two premises, or they might be more complicated. But no matter how big or fancy the argument is, the same rule applies: the premises must be solid to support a good conclusion.

Logical Fallacy Examples in Life

Logical fallacies might seem small or harmless, but they can influence our decisions, beliefs, and actions in significant ways.

Advertising

Consider the world of advertising. Ads often use emotional appeals or bandwagon techniques to convince you to buy a product.

"Everyone's using this toothpaste, so you should too!" or "This celebrity loves our shoes, and you will too!"

If we don't recognize these as bandwagon or appeal to authority fallacies, we might end up spending money on things we don't need.

Social Media

Then there's the realm of social media. We've all seen heated debates in comment sections.

People might attack someone's character instead of their ideas, which is the ad hominem fallacy. Or, someone might oversimplify another person's viewpoint, setting up a straw man argument to easily tear it down.

When we're unaware of these tactics, it's easy to get dragged into unproductive or hurtful conversations.

And it's not just online. In real life, we make decisions based on information from friends, family, news, and many other sources.

If we're not careful, we might base important choices on faulty logic. Like believing a certain health remedy works just because a famous person endorses it without checking the actual science behind it.

Tips to Avoid Falling for Logical Fallacies

Understanding logical fallacies is half the battle. But how do you avoid them in real life? It's a bit like avoiding potholes on a road. Once you know where they are and what they look like, you can steer clear.

Here are some handy tips to help you navigate the landscape of logic more safely.

- Stay Curious: Always be open to learning. The more knowledge you gather, the better you'll be able to recognize when something doesn't add up.

- Question Everything: Just because something sounds right doesn't mean it is. Like a detective, look for evidence and ask yourself if an argument makes sense.

- Slow Down: Our world is fast-paced. But sometimes, taking a moment to think before responding or making a decision can save you from falling into a logical trap.

- Stay Humble: Remember, it's okay to be wrong. If someone points out a flaw in your reasoning, thank them. It's a chance to learn and grow.

- Discuss with Others: Talking things out can be a great way to spot flaws. Different perspectives can shine a light on areas you might have missed.

- Educate Yourself: There are plenty of resources, including books and courses, that can deepen your understanding of logical thinking. The more you learn, the sharper your logic skills will become.

- Practice Makes Perfect: Like any skill, spotting logical fallacies gets easier with practice. Challenge yourself by analyzing arguments in articles, shows, or conversations. The more you do it, the better you'll get.

Remember, nobody's perfect. We all slip up from time to time. But with these tips in your toolkit, you'll be well on your way to clearer, more logical thinking.

Spot the Fallacy Quiz

Try to identify each fallacy based on the examples provided. The answers are provided at the end.

- "My mom said that broccoli is good for me, so it must be true."

- "Either you stand with us, or you’re against us."

- "She can’t be a great scientist. Have you seen how disorganized her office is?"

- "We know our product is the best because it’s the top-selling item in its category."

- "He can’t be a criminal; he comes from a nice family and attended a prestigious university."

- "Well, you smoke cigarettes, so you have no right to tell me not to eat junk food."

- "We can’t let the students have extra recess time; soon, they’ll want the whole school day to be a playground."

- "Everyone’s going to the big football game, so it must be amazing."

- "No one has proven that ghosts don’t exist, so they must be real."

- "He’s never been to Asia, so he can't possibly know how to prepare Asian cuisine."

- "You can’t trust John’s political opinion because he’s just a mechanic."

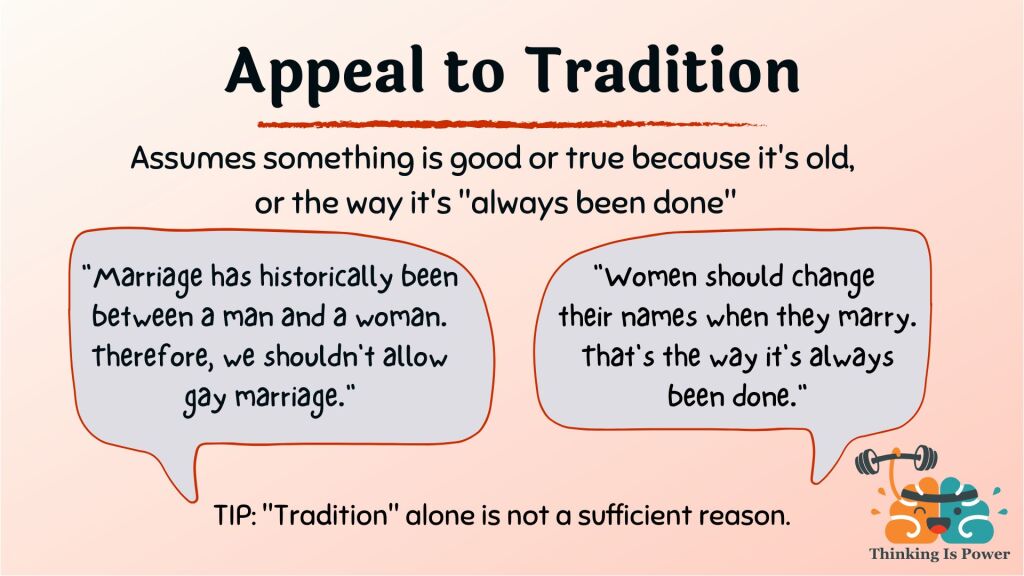

- "We’ve always done it this way, so it’s the best way to keep doing it."

- "You believe in evolution? Well, that’s just a theory!"

- "If you cared about the environment, you wouldn't drive a car."

- "Since you didn’t deny the allegations immediately, you must be guilty."

- "We don’t know what causes thunder, so it must be the gods showing their anger."

- "This anti-aging cream must work; see all these photos of people who look younger after using it!"

- "No Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge!"

- "If we allow people to protest, it will encourage lawlessness and chaos."

- "We can't believe in climate change. Think of all the jobs we will lose in traditional industries!"

- Appeal to Authority

- False Dichotomy/Black and White Fallacy

- Genetic Fallacy

- Slippery Slope

- Argument from Ignorance

- No True Scotsman

- Appeal to Tradition

- Black-and-White Fallacy

- Argument from Silence

- God of the Gaps/Argument from Ignorance

- Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc

- Appeal to Consequence

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) about Logical Fallacies

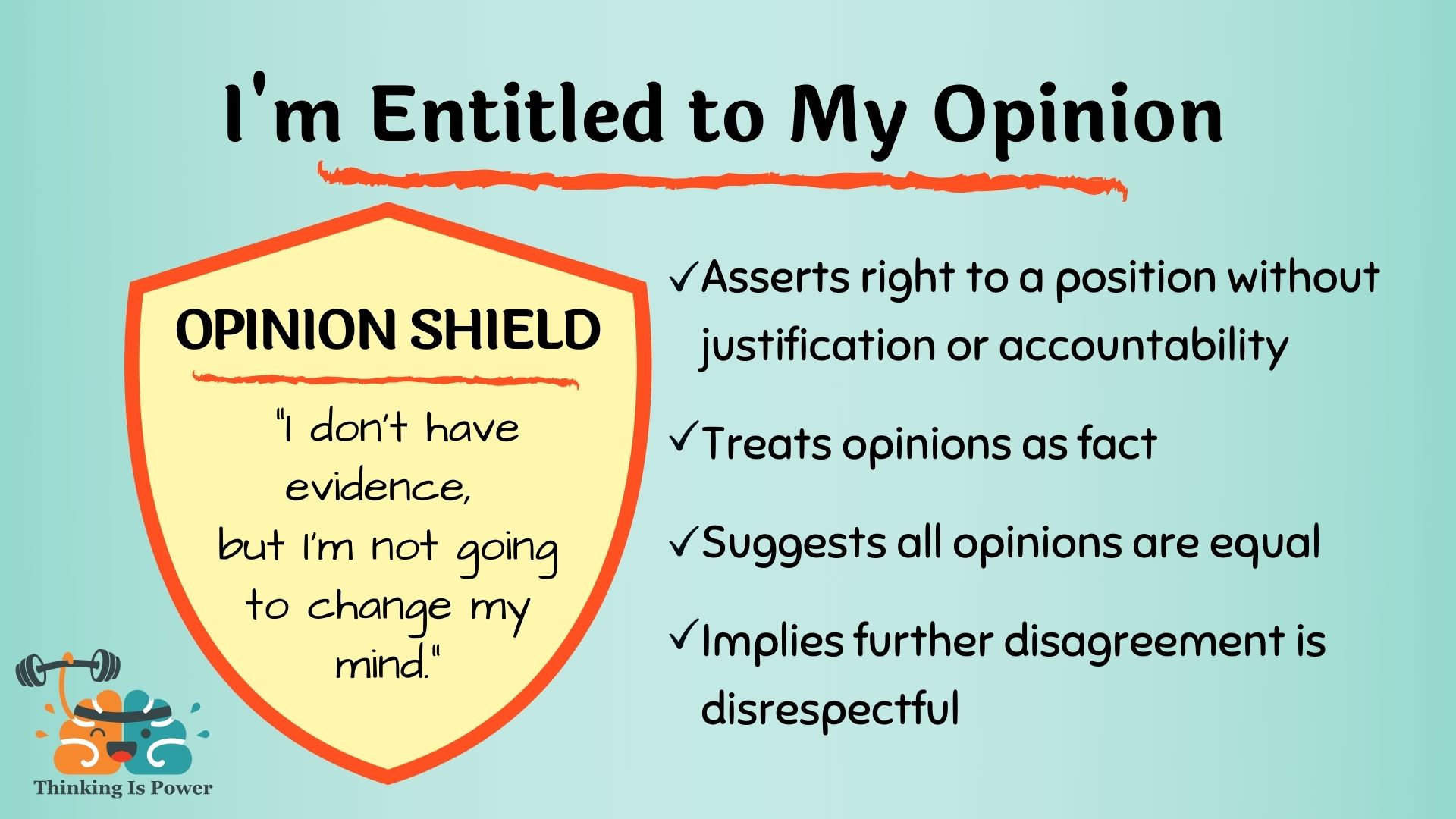

What is a logical fallacy? A logical fallacy is an error or flaw in reasoning. These errors can weaken arguments and can be intentional or unintentional. They often appear to sound convincing but are based on faulty logic.

Why do people use logical fallacies? Some people might use them unintentionally due to a lack of knowledge or clarity in thinking. Others might use them strategically to persuade or deceive, especially if they believe their audience won't recognize the fallacy.

Are all fallacies intentional? No. Many fallacies are the result of honest mistakes or oversights in reasoning. However, some can be used manipulatively in debates, advertisements, or persuasive speeches.

What’s the difference between an informal and a formal fallacy? Informal fallacies are mistakes in reasoning based on the content of an opponent's argument, often arising in everyday language. Formal fallacies are structural errors in an argument, regardless of the argument's content.

Can a statement be true even if it contains a logical fallacy? Yes. A fallacy indicates flawed reasoning, not necessarily a false conclusion. However, conclusions reached through fallacious reasoning should be critically evaluated.

How can I improve my ability to spot logical fallacies? Educate yourself on different types of fallacies, engage in discussions, analyze arguments in various media, and regularly practice identifying them. Over time, spotting most common logical fallacies will become second nature.

Are logical fallacies a modern concept? No. The study of fallacies dates back to ancient Greece, with philosophers like Aristotle detailing various types of flawed arguments.

Why is it essential to recognize logical fallacies? Recognizing fallacies can help you make better decisions, strengthen your own arguments, and avoid being misled by faulty reasoning.

Can a logical fallacy be valid in some contexts? While the reasoning may be flawed, the underlying point someone is trying to make could still be valid. However, it's essential to separate the valid point from the fallacious argument.

Grasping the nuances of logical fallacies is more than just an academic exercise—it's a life skill.

In a world saturated with information, discerning sound arguments from flawed ones is invaluable. As you continue your journey in understanding and recognizing these fallacies, you're not only refining your ability to think critically but also empowering yourself to engage more constructively in discussions and debates.

Remember, pursuing clear, logical, critical thinking is a journey, not a destination. As you grow and learn, you'll become better equipped to navigate the complex landscape of ideas and arguments that surround us daily.

Related posts:

- Ad Hoc Fallacy (29 Examples + Other Names)

- Genetic Fallacy (28 Examples + Definition)

- Appeal to Ignorance Fallacy (29 Examples + Description)

- Hasty Generalization Fallacy (31 Examples + Similar Names)

- Appeal to Force Fallacy (Description + 9 Examples)

Reference this article:

About The Author

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Jessie Ball duPont Library

Critical thinking skills, watch the fallacies.

- Need Research Help?

- Research Help

Although there are more than two dozen types and subtypes of logical fallacies, these are the most common forms that you may encounter in writing, argument, and daily life:

Example: Special education students should not be required to take standardized tests because such tests are meant for nonspecial education students.

Example: Two out of three patients who were given green tea before bedtime reported sleeping more soundly. Therefore, green tea may be used to treat insomnia.

- Sweeping generalizations are related to the problem of hasty generalizations. In the former, though, the error consists in assuming that a particular conclusion drawn from a particular situation and context applies to all situations and contexts. For example, if I research a particular problem at a private performing arts high school in a rural community, I need to be careful not to assume that my findings will be generalizable to all high schools, including public high schools in an inner city setting.

Example: Professor Berger has published numerous articles in immunology. Therefore, she is an expert in complementary medicine.

Example: Drop-out rates increased the year after NCLB was passed. Therefore, NCLB is causing kids to drop out.

Example: Japanese carmakers must implement green production practices, or Japan‘s carbon footprint will hit crisis proportions by 2025.

In addition to claims of policy, false dilemma seems to be common in claims of value. For example, claims about abortion‘s morality (or immorality) presuppose an either-or about when "life" begins. Our earlier example about sustainability (―Unsustainable business practices are unethical.‖) similarly presupposes an either/or: business practices are either ethical or they are not, it claims, whereas a moral continuum is likelier to exist.

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning

Hasty Generalization

Sweeping Generalization

Non Sequitur

Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc

False Dilemma

- << Previous: Abduction

- Next: Need Research Help? >>

- Last Updated: Jul 28, 2020 5:53 PM

- URL: https://library.sewanee.edu/critical_thinking

Research Tools

- Find Articles

- Find Research Guides

- Find Databases

- Ask a Librarian

- Learn Research Skills

- How-To Videos

- Borrow from Another Library (Sewanee ILL)

- Find Audio and Video

- Find Reserves

- Access Electronic Resources

Services for...

- College Students

- The School of Theology

- The School of Letters

- Community Members

Spaces & Places

- Center for Leadership

- Center for Speaking and Listening

- Center for Teaching

- Floor Maps & Locations

- Ralston Listening Library

- Study Spaces

- Tech Help Desk

- Writing Center

About the Library

- Where is the Library?

- Library Collections

- New Items & Themed Collections

- Library Policies

- Library Staff

- Friends of the Library

Jessie Ball duPont Library, University of the South

178 Georgia Avenue, Sewanee, TN 37383

931.598.1664

Critical Thinking - Writing Lab Tips and Strategies: Logical Fallacies

Logical fallacies.

Fallacies are fake or deceptive arguments, arguments that may sound good but prove nothing.

Ad Hominem Argumen t : Attacking the person instead of the argument.

Appeal to Closure : The argument that the issue must be decided so that those involved can have "closure."

Appeal to Heaven : Arguing that one's position or action is right because God said so. As Christians, we believe God has revealed his will through Scripture, but we can still fall into this fallacy if we attempt to justify ourselves apart from what the Bible says. Even if we are being consistent with Scripture, we may still be accused of this fallacy.

Appeal to Pity : Urging an audience to “root for the underdog” regardless of the issues at hand.

Appeal to Tradition : It's always been this way, it should continue to be this way.

Argument from Consequences : The fallacy of arguing that something cannot be true because if it were the consequences would be unacceptable.

Argument from Ignorance: The fallacy that since we don’t know whether a claim is true or false, it must be false (or that it must be true).

Argument from Inertia: The argument to continue on as before because changing would be admitting that one is wrong and that one had sacrificed needlessly.

Argument from Motives: The argument that someone must be wrong because their motives are wrong. Also, the reverse: someone is right because their motives are right.

Argumentum ad Baculam: Attempting to persuade through threats. Also applies to indirect forms of threat.

Argumentum ex Silentio: The fallacy that if sources remain silent or say nothing about a given subject or question this in itself proves something about the truth of the matter.

Bandwagon: The fallacy of arguing that because "everyone" supposedly thinks or does something, it must be right.

Begging the Question : Falsely arguing that something is true by repeating the same statement in different words.

Big Lie Technique: Repeating a lie, slogan or deceptive half-truth over and over (particularly in the media) until people believe it without further proof or evidence.

Blind Loyalty: Arguing something is right solely because a respected leader or source says it is right.

Blood is Thicker than Water: Automatically regarding something as true because one is related to (or knows and likes, or is on the same team as) the individual involved.

Bribery: Persuading with gifts instead of logic.

The Complex Question : Demanding a direct answer to a question containing acceptable and unacceptable parts. Example: "Yes or no: Have you stopped beating your wife yet?" "I never beat my--" "Just answer me: Yes or no?"

Diminished Responsibility : The argument that one is less responsible for an action because one's judgment was altered. Example: "I was high, so I shouldn't be fined for speeding; it wasn't my fault."

Either-Or Reasoning: Falsely offering only two possible alternatives even though a broad range of possible alternatives are available.

”E" for Effort: Arguing that something must be right, valuable, or worthy of credit simply because someone has put so much sincere good-faith effort or even sacrifice and bloodshed into it.

Equivocation : Deliberately failing to define one's terms, or deliberately using words in a different sense than the one the audience will understand.

Essentializing : A fallacy that proposes a person or thing “is what it is and that’s all that it is,” and at its core will always be what it is right now (E.g., "All ex-cons are criminals, and will still be criminals even if they live to be 100."). Also refers to the fallacy of arguing that something is a certain way "by nature," an empty claim that no amount of proof can refute.

False Analogy : Incorrectly comparing one thing to another in order to draw a false conclusion.

Finish the Job: Arguing that an action or standpoint may not be questioned or discussed because there is "a job to be done," falsely assuming all "jobs" are never to be questioned.

Guilt by Association: Trying to refute someone's arguments or actions by evoking the negative ethos of those with whom one associates.

The Half Truth (also Card Stacking, Incomplete Information).Telling the truth but deliberately omitting important key details in order to falsify the larger picture and support a false conclusion.

I Wish I Had a Magic Wand: Regretfully (and falsely) proclaiming oneself powerless to change a bad or objectionable situation because there is no alternative.

Just in Case : Basing one's argument on a far-fetched or imaginary worst-case scenario rather than on reality. Plays on fear rather than reason.

Lying with Statistics : Using true figures and numbers to “prove” unrelated claims.

MYOB (Mind Your Own Business) Arbitrarily prohibiting any discussion of one's own standpoints or behavior, no matter how absurd, dangerous, evil or offensive, by drawing a phony curtain of privacy around oneself and one's actions.

Name-Calling: Arguing that, simply because of who someone is, any and all arguments, disagreements or objections against his or her standpoint are automatically racist, sexist, anti-Semitic, bigoted, discriminatory or hateful.

Non Sequitur : Offering reasons or conclusions that have no logical connection to the argument at hand.

Overgeneralization: Incorrectly applying one or two examples to all cases.

The Paralysis of Analysis : Arguing that since all data is never in, no legitimate decision can ever be made and any action should always be delayed until forced by circumstances.

Playing on Emotions : Ignoring facts and calling on emotion alone.

Political Correctness ("PC"): Proposing that the nature of a thing or situation can be changed simply by changing its name.

Post Hoc Argument : Arguing that because something comes at the same time or just after something else, the first thing is caused by the second.

Red Herring : An irrelevant distraction, attempting to mislead an audience by bringing up an unrelated, but usually emotionally loaded issue.

Reductionism : Deceiving an audience by giving simple answers or slogans in response to complex questions, especially when appealing to less educated or unsophisticated audiences.

Reifying : The fallacy of treating imaginary categories as actual, material "things."

Sending the Wrong Message : Attacking a given statement or action, no matter how true, correct or necessary, because it will "send the wrong message." In effect, those who uses this fallacy are publicly confessing to fraud and admitting that the truth will destroy the fragile web of illusion that has been created by their lies.

Shifting the Burden of Proof: Challenging opponents to disprove a claim, rather than asking the person making the claim to defend his/her own argument.

Slippery Slope : The common fallacy that "one thing inevitably leads to another."

Snow Job : "Proving” a claim by overwhelming an audience with mountains of irrelevant facts, numbers, documents, graphs and statistics that they cannot be expected to understand.

Straw Man : Setting up a phony version of an opponent's argument, and then proceeding to knock it down with a wave of the hand.

Taboo : Unilaterally declaring certain arguments, standpoints or actions to be not open to discussion.

Testimonial : When a standpoint or product is supported by a well-known or respected figure who is not an expert and who was probably well paid for the endorsement.

They're Not Like Us : Arbitrarily disregarding a fact, argument, or objection because those involved "are not like us," or "don't think like us."

TINA (There Is No Alternative): Squashing critical thought by announcing that there is no realistic alternative to a given standpoint, status or action, ruling any and all other options irrelevant and any further discussion is simply a waste of time.

Transfer : Falsely associating a famous person or thing with an unrelated standpoint.

Tu Quoque: Defending a shaky or false standpoint or excusing one's own bad action by pointing out that one's opponent's acts or personal character are also open to question, or even worse.

We Have to Do Something : Arguing that in moments of crisis one must do something, anything , at once, even if it is an overreaction, is totally ineffective or makes the situation worse, rather than "just sitting there doing nothing."

Where there’s smoke, there’s fire : Quickly drawing a conclusion and/or taking action without sufficient evidence.

For more in-depth discussion of these fallacies, refer to http://utminers.utep.edu/omwilliamson/ENGL1311/fallacies.htm

Subject Guide

I'm trying to think critically, but I'm a frog

- << Previous: Home

- Last Updated: May 17, 2023 3:05 PM

- URL: https://libguides.grace.edu/CriticalThinking

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Two competing conceptions of fallacies are that they are false but popular beliefs and that they are deceptively bad arguments. These we may distinguish as the belief and argument conceptions of fallacies. Academic writers who have given the most attention to the subject of fallacies insist on, or at least prefer, the argument conception of fallacies, but the belief conception is prevalent in popular and non-scholarly discourse. As we shall see, there are yet other conceptions of what fallacies are, but the present inquiry focuses on the argument conception of fallacies.

Being able to detect and avoid fallacies has been viewed as a supplement to criteria of good reasoning. The knowledge of fallacies is needed to arm us against the most enticing missteps we might take with arguments—so thought not only Aristotle but also the early nineteenth century logicians Richard Whately and John Stuart Mill. But as the course of logical theory from the late nineteenth-century forward turned more and more to axiomatic systems and formal languages, the study of reasoning and natural language argumentation received much less attention, and hence developments in the study of fallacies almost came to a standstill. Until well past the middle of the twentieth century, discussions of fallacies were for the most part relegated to introductory level textbooks. It was only when philosophers realized the ill fit between formal logic, on the one hand, and natural language reasoning and argumentation, on the other, that the interest in fallacies has returned. Since the 1970s the utility of knowing about fallacies has been acknowledged (Johnson and Blair 1993), and the way in which fallacies are incorporated into theories of argumentation has been taken as a sign of a theory’s level of adequacy (Biro and Siegel 2007, van Eemeren 2010).

In modern fallacy studies it is common to distinguish formal and informal fallacies. Formal fallacies are those readily seen to be instances of identifiable invalid logical forms such as undistributed middle and denying the antecedent. Although many of the informal fallacies are also invalid arguments, it is generally thought to be more profitable, from the points of view of both recognition and understanding, to bring their weaknesses to light through analyses that do not involve appeal to formal languages. For this reason it has become the practice to eschew the symbolic language of formal logic in the analysis of these fallacies; hence the term ‘informal fallacy’ has gained wide currency. In the following essay, which is in four parts, it is what is considered the informal-fallacy literature that will be reviewed. Part 1 is an introduction to the core fallacies as brought to us by the tradition of the textbooks. Part 2 reviews the history of the development of the conceptions of fallacies as it is found from Aristotle to Copi. Part 3 surveys some of the most recent innovative research on fallacies, and Part 4 considers some of the current research topics in fallacy theory.

1. The core fallacies

2.1 aristotle, 2.3 arnauld and nicole, 2.6 bentham, 2.7 whately, 3.1 renewed interest, 3.2 doubts about fallacies, 3.3 the informal logic approach to fallacies, 3.4 the formal approach to informal fallacies, 3.5 the epistemic approach to fallacies, 3.6 dialectical/dialogical approaches to fallacies, 4.1 the nature of fallacies, 4.2 the appearance condition, 4.3 teaching, other internet resources, related entries.

Irving Copi’s 1961 Introduction to Logic gives a brief explanation of eighteen informal fallacies. Although there is some variation in competing textbooks, Copi’s selection captured what for many was the traditional central, core fallacies. [ 1 ] In the main, these fallacies spring from two fountainheads: Aristotle’s Sophistical Refutations and John Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690). By way of introduction, a brief review of the core fallacies, especially as they appear in introductory level textbooks, will be given. Only very general definitions and illustrations of the fallacies can be given. This proviso is necessary first, because, the definitions (or identity conditions) of each of the fallacies is often a matter of contention and so no complete or final definition can be given in an introductory survey; secondly, some researchers wish that only plausible and realistic instances of each fallacy be used for illustration. This also is not possible at this stage. The advantage of the stock examples of fallacies is that they are designed to highlight what the mistake associated with each kind of fallacy is supposed to be. Additional details about some of the fallacies are found in Sections 2 and 3. As an initial working definition of the subject matter, we may take a fallacy to be an argument that seems to be better than it really is.

1. The fallacy of equivocation is an argument which exploits the ambiguity of a term or phrase which has occurred at least twice in an argument, such that on the first occurrence it has one meaning and on the second another meaning. A familiar example is:

The end of life is death. Happiness is the end of life. So, death is happiness.

‘The end of life’ first means ceasing to live, then it means purpose. That the same set of words is used twice conceals the fact that the two distinct meanings undermine the continuity of the reasoning, resulting in a non-sequitur .

2. The fallacy of amphiboly is, like the fallacy of equivocation, a fallacy of ambiguity; but here the ambiguity is due to indeterminate syntactic structure. In the argument:

The police were told to stop drinking on campus after midnight. So, now they are able to respond to emergencies much better than before

there are several interpretations that can be given to the premise because it is grammatically ambiguous. On one reading it can be taken to mean that it is the police who have been drinking and are now to stop it; this makes for a plausible argument. On another reading what is meant is that the police were told to stop others (e.g., students) from drinking after midnight. If that is the sense in which the premise is intended, then the argument can be said to be a fallacy because despite initial appearances, it affords no support for the conclusion.

3 & 4. The fallacies of composition and division occur when the properties of parts and composites are mistakenly thought to be transferable from one to the other. Consider the two sentences:

- Every member of the investigative team was an excellent researcher.

- It was an excellent investigative team.

Here it is ‘excellence’ that is the property in question. The fallacy of composition is the inference from (a) to (b) but it need not hold if members of the team cannot work cooperatively with each other. The reverse inference from (b) to (a)—the fallacy of division—may also fail if some essential members of the team have a supportive or administrative role rather than a research role.

5. The fallacy of begging the question ( petitio principii ) can occur in a number of ways. One of them is nicely illustrated with Whately’s (1875 III §13) example: “to allow everyman an unbounded freedom of speech must always be, on the whole, advantageous to the State; for it is highly conducive to the interest of the Community, that each individual should enjoy a liberty perfectly unlimited, of expressing his sentiments.” This argument begs the question because the premise and conclusion are the very same proposition, albeit expressed in different words. It is a disguised instance of repetition which gives no reason for its apparent conclusion.

Another version of begging the question can occur in contexts of argumentation where there are unsettled questions about key terms. Suppose, for example, that everyone agrees that to murder someone requires doing something that is wrong, but not everyone agrees that capital punishment is a form of ‘murder’; some think it is justified killing. Then, should an arguer gives this argument:

Capital punishment requires an act of murdering human beings. So, capital punishment is wrong.

one could say that this is question-begging because in this context of argumentation, the arguer is smuggling in as settled a question that remains open. That is, if the premise is accepted without further justification, the arguer is assuming the answer to a controversial question without argument.

Neither of these versions of begging the question are faulted for their invalidity, so they are not charged with being non-sequitors like most of the core fallacies; they are, however, attempted proofs that do not transparently display their weakness. This consideration, plus its ancient lineage back to Aristotle, might explain begging the question’s persistent inclusion among fallacies. But, given our allegiance to the modern conception of logic as being solely concerned with the following-from relation, forms of begging the question should be thought of as epistemic rather than logical fallacies.

Some versions of begging the question are more involved and are called circular reasoning. They include more than one inference. Descartes illustrated this kind of fallacy with the example of our belief in the Bible being justified because it is the word of God, and our belief in God’s existence being justified because it is written in the Bible. [ 2 ] The two propositions lead back and forth to each other, in a circle, each having only the support of the other.

6. The fallacy known as complex question or many questions is usually explained as a fallacy associated with questioning. For example, in a context where a Yes or No answer must be given, the question, “Are you still a member of the Ku Klux Klan?” is a fallacy because either response implies that one has in the past been a member of the Klan, a proposition that may not have been established as true. Some say that this kind of mistake is not really a fallacy because to ask a question is not to make an argument.

7. There are a number of fallacies associated with causation, the most frequently discussed is post hoc ergo propter hoc , (after this, therefore because of this). This fallacy ascribes a causal relationship between two states or events on the basis of temporal succession. For example,

Unemployment decreased in the fourth quarter because the government eliminated the gasoline tax in the second quarter.

The decrease in unemployment that took place after the elimination of the tax may have been due to other causes; perhaps new industrial machinery or increased international demand for products. Other fallacies involve confusing the cause and the effect, and overlooking the possibility that two events are not directly related to each other but are both the effect of a third factor, a common cause. These fallacies are perhaps better understood as faults of explanation than faults of arguments.

8. The fallacy of ignoratio elenchi , or irrelevant conclusion, is indicative of misdirection in argumentation rather than a weak inference. The claim that Calgary is the fastest growing city in Canada, for example, is not defeated by a sound argument showing that it is not the biggest city in Canada. A variation of ignoratio elenchi , known under the name of the straw man fallacy, occurs when an opponent’s point of view is distorted in order to make it easier to refute. For example, in opposition to a proponent’s view that (a) industrialization is the cause of global warming, an opponent might substitute the proposition that (b) all ills that beset mankind are due to industrialization and then, having easily shown that (b) is false, leave the impression that (a), too, is false. Two things went wrong: the proponent does not hold (b), and even if she did, the falsity of (b) does not imply the falsity of (a).

There are a number of common fallacies that begin with the Latin prefix ‘ ad ’ (‘to’ or ‘toward’) and the most common of these will be described next.

9. The ad verecundiam fallacy concerns appeals to authority or expertise. Fundamentally, the fallacy involves accepting as evidence for a proposition the pronouncement of someone who is taken to be an authority but is not really an authority. This can happen when non-experts parade as experts in fields in which they have no special competence—when, for example, celebrities endorse commercial products or social movements. Similarly, when there is controversy, and authorities are divided, it is an error to base one’s view on the authority of just some of them. (See also 2.4 below.)

10. The fallacy ad populum is similar to the ad verecundiam , the difference being that the source appealed to is popular opinion, or common knowledge, rather than a specified authority. So, for example:

These days everyone (except you) has a car and knows how to drive; So, you too should have a car and know how to drive.

Often in arguments like this the premises aren’t true, but even if they are generally true they may provide only scant support for their conclusions because that something is widely practised or believed is not compelling evidence that it is true or that it should be done. There are few subjects on which the general public can be said to hold authoritative opinions. Another version of the ad populum fallacy is known as “playing to the gallery” in which a speaker seeks acceptance for his view by arousing relevant prejudices and emotions in his audience in lieu of presenting it with good evidence.

11. The ad baculum fallacy is one of the most controversial because it is hard to see that it is a fallacy or even that it involves bad reasoning. Ad baculum means “appeal to the stick” and is generally taken to involve a threat of injury of harm to the person addressed. So, for example,

If you don’t join our demonstration against the expansion of the park, we will evict you from your apartment; So, you should join our demonstration against the expansion of the park.

Such threats do give us reasons to act and, unpleasant as the interlocutor may be, there seems to be no fallacy here. In labour disputes, and perhaps in international relations, using threats such as going on strike, or cutting off trade routes, are not normally considered fallacies, even though they do involve intimidation and the threat of harm. However, if we change to doxastic considerations, then the argument that you should believe that candidate \(X\) is the one best suited for public office because if you do not believe this you will be evicted from your apartment, certainly is a good instance of irrelevant evidence.

12. The fallacy ad misericordiam is a companion to the ad baculum fallacy: it occurs not when threats are out of place but when appeals for sympathy or pity are mistakenly thought to be evidence. To what extent our sympathy for others should influence our actions depends on many factors, including circumstances and our ethical views. However, sympathy alone is generally not evidence for believing any proposition. Hence,

You should believe that he is not guilty of embezzling those paintings; think of how much his family suffered during the Depression.

Ad misericordiam arguments, like ad baculum arguments, have their natural home in practical reasoning; it is when they are used in theoretical (doxastic) argumentation that the possibility of fallacy is more likely.

13. The ad hominem fallacy involves bringing negative aspects of an arguer, or their situation, to bear on the view they are advancing. There are three commonly recognized versions of the fallacy. The abusive ad hominem fallacy involves saying that someone’s view should not be accepted because they have some unfavorable property.

Thompson’s proposal for the wetlands may safely be rejected because last year she was arrested for hunting without a license.

The hunter Thompson, although she broke the law, may nevertheless have a very good plan for the wetlands.

Another, more subtle version of the fallacy is the circumstantial ad hominem in which, given the circumstances in which the arguer finds him or herself, it is alleged that their position is supported by self-interest rather than by good evidence. Hence, the scientific studies produced by industrialists to show that the levels of pollution at their factories are within the law may be undeservedly rejected because they are thought to be self-serving. Yet it is possible that the studies are sound: just because what someone says is in their self-interest, does not mean it should be rejected.

The third version of the ad hominem fallacy is the tu quoque . It involves not accepting a view or a recommendation because the espouser him- or herself does not follow it. Thus, if our neighbor advises us to exercise regularly and we reject her advice on the basis that she does not exercise regularly, we commit the tu quoque fallacy: the value of advice is not wholly dependent on the integrity of the advisor.

We may finish our survey of the core fallacies by considering just two more.

14. The fallacy of faulty analogy occurs when analogies are used as arguments or explanations and the similarities between the two things compared are too remote to support the conclusion.

If a child gets a new toy he or she will want to play with it; So, if a nation gets new weapons, it will want to use them.

In this example (due to Churchill 1986, 349) there is a great difference between using (playing with) toys and using (discharging) weapons. The former is done for amusement, the latter is done to inflict harm on others. Playing with toys is a benign activity that requires little justification; using weapons against others nations is something that is usually only done after extensive deliberation and as a last resort. Hence, there is too much of a difference between using toys and using weapons to conclude that a nation, if it acquires weapons, will want to use them as readily as children will want to play with their toys.

15. The fallacy of the slippery slope generally takes the form that from a given starting point one can by a series of incremental inferences arrive at an undesirable conclusion, and because of this unwanted result, the initial starting point should be rejected. The kinds of inferences involved in the step-by-step argument can be causal, as in:

You have decided not to go to college; If you don’t go to college, you won’t get a degree; If you don’t get a degree, you won’t get a good job; If you don’t get a good job, you won’t be able to enjoy life; But you should be able to enjoy life; So, you should go to college.

The weakness in this argument, the reason why it is a fallacy, lies in the second and third causal claims. The series of small steps that lead from an acceptable starting point to an unacceptable conclusion may also depend on vague terms rather than causal relations. Lack of clear boundaries is what enables the puzzling slippery slope arguments known as “the beard” and “the heap.” In the former, a person with a full beard eventually becomes beardless as hairs of the beard are removed one-by-one; but because the term ‘beard’ is vague it is unclear at which intermediate point we are to say that the man is now beardless. Hence, at each step in the argument until the final hair-plucking, we should continue to conclude that the man is bearded. In the second case, because ‘heap’ is vague, it is unclear at what point piling scattered stones together makes them a heap of stones: if it is not a heap to begin with, adding one more stone will not make it a heap, etc. In both these cases apparently good reasoning leads to a false conclusion.

Many other fallacies have been named and discussed, some of them quite different from the ones mentioned above, others interesting and novel variations of the above. Some of these will be mentioned in the review of historical and contemporary sources that follows.

2. History of Fallacy Theory

The history of the study of fallacies begins with Aristotle’s work, On Sophistical Refutations . It is among his earlier writings and the work appears to be a continuation of the Topics , his treatise on dialectical argumentation. Although his most extensive and theoretically detailed discussion of fallacies is in the Sophistical Refutations , Aristotle also discusses fallacies in the Prior Analytics and On Rhetoric . Here we will concentrate on summarizing the account given in the Sophistical Refutations . In that work, four things are worth noting: (a) the different conceptions of fallacy; (b) the basic concepts used to explain fallacies; (c) Aristotle’s explanation of why fallacies can be deceptive; and (d) his enumeration and classification of fallacies.

2.1.1 Definitions

At the beginning of Topics (I, i), Aristotle distinguishes several kinds of deductions (syllogisms). They are distinguished first on the basis of the status of their premises. (1) Those that begin from true and primary premises, or are owed to such, are demonstrations. (2) Those which have dialectical premises—propositions acceptable to most people, or to the wise—are dialectical deductions. (3) Deductions that start from premises which only appear to be dialectical, are fallacious deductions because of their starting points, as are (4) those “deductions” that do have dialectical premises but do not really necessitate their conclusions. Other fallacies mentioned and associated with demonstrations are (5) those which only appear to start from what is true and primary ( Top ., I, i 101a5). What this classification leaves out are (6) the arguments that do start from true and primary premises but then fail to necessitate their conclusions; two of these, begging the question and non-cause are discussed in Prior Analytics (II, 16, 17). It is the “fallacious deductions” characterized in (4), however, that come closest to the focus of the Sophistical Refutations . Nevertheless, in many of the examples given what stands out is that the premises are given as answers in dialogue and are to be maintained by the answerer, not necessarily that they are dialectical in the sense of being common opinions. This variation on dialectical deductions Aristotle calls examination arguments ( SR 2 165b4).

2.1.2 The basic concepts

There are three closely related concepts needed to understand sophistical refutations. By a deduction (a syllogism [ 3 ] ) Aristotle meant an argument which satisfies three conditions: it “is based on certain statements made in such a way as necessarily to cause the assertion of things other than those statements and as a result of those statements” ( SR 1 165a1–2). Thus an argument may fail to be a syllogism in three different ways. The premises may fail to necessitate the conclusion, the conclusion may be the same as one of the premises, and the conclusion may not be caused by (grounded in) the premises. The concept of a proof underlying Sophistical Refutations is similar to what is demanded of demonstrative knowledge in Posterior Analytics (I ii 71b20), viz., that the premises must be “true, primary, immediate, better known than, prior to, and causative of the conclusion,” except that the first three conditions do not apply to deductions in which the premises are obtained through questioning. A refutation , Aristotle says, is “a proof of the contradictory” ( SR 6, 168a37)—a proof of the proposition which is the contradictory of the thesis maintained by the answerer. In a context of someone, S , maintaining a thesis, T , a dialectical refutation will consist in asking questions of S , and then taking S ’s answers and using them as the premises of a proof via a deduction of not-T : this will be a refutation of T relative to the answerer ( SR 8 170a13). The concept of contradiction can be found in Categories : it is those contraries which are related such that “one opposite needs must be true, while the other must always be false” (13b2–3). A refutation will be sophistical if either the proof is only an apparent proof or the contradiction is only an apparent contradiction. Either way, according to Aristotle, there is a fallacy. Hence, the opening of his treatise: “Let us now treat of sophistical refutations, that is, arguments which appear to be refutations but are really fallacies and not refutations” ( SR 1 164a20).

2.1.3 The appearance condition

Aristotle observed that “reasoning and refutation are sometimes real and sometimes not, but appear to be real owing to men’s inexperience; for the inexperienced are like those who view things from a distance” ( SR , 1 164b25). The ideas here are first that there are arguments that appear to be better than they really are; and second that people inexperienced in arguments may mistake the appearance for the reality and thus be taken in by a bad argument or refutation. Apparent refutations are primarily explained in terms of apparent deductions: thus, with one exception, Aristotle’s fallacies are in the main a catalogue of bad deductions that appear to be good deductions. The exception is ignoratio elenchi in which, in one of its guises, the deduction contains no fallacy but the conclusion proved only appears to contradict the answerer’s thesis.

Aristotle devotes considerable space to explaining how the appearance condition may arise. At the outset he mentions the argument that turns upon names ( SR 1 165a6), saying that it is the most prolific and usual explanation: because there are more things than names, some names will have to denote more than one thing, thereby creating the possibility of ambiguous terms and expressions. That the ambiguous use of a term goes unnoticed allows the illusion that an argument is a real deduction. The explanation of how the false appearance can arise is in the similarity of words or expressions with different meanings, and the smallness of differences in meaning between some expressions ( SR 7 169a23–169b17).

2.1.4 List and classification

Aristotle discusses thirteen ways in which refutations can be sophistical and divides them into two groups. The first group, introduced in Chapter 4 of On Sophistical Refutations , includes those Aristotle considers dependent on language ( in dictione ), and the second group, introduced in Chapter 5, includes those characterized as not being dependent on language ( extra dictionem ). Chapter 6 reviews all the fallacies from the view point of failed refutations, and Chapter 7 explains how the appearance of correctness is made possible for each fallacy. Chapters 19–30 advise answerers on how to avoid being taken in by sophistical refutations.

The fallacies dependent on language are equivocation, amphiboly, combination of words, division of words, accent and form of expression. Of these the first two have survived pretty much as Aristotle thought of them. Equivocation results from the exploitation of a term’s ambiguity and amphiboly comes about through indefinite grammatical structure. The one has to do with semantical ambiguity, the other with syntactical ambiguity. However, the way that Aristotle thought of the combination and division fallacies differs significantly from modern treatments of composition and division. Aristotle’s fallacies are the combinations and divisions of words which alter meanings, e.g., “walk while sitting” vs. “walk-while-sitting,” (i.e., to have the ability to walk while seated vs. being able to walk and sit at the same time). For division, Aristotle gives the example of the number 5: it is 2 and 3. But 2 is even and 3 is odd, so 5 is even and odd. Double meaning is also possible with those words whose meanings depend on how they are pronounced, this is the fallacy of accent, but there were no accents in written Greek in Aristotle’s day; accordingly, this fallacy would be more likely in written work. What Aristotle had in mind is something similar to the double meanings that can be given to ‘unionized’ and ‘invalid’ depending on how they are pronounced. Finally, the fallacy that Aristotle calls form of expression exploits the kind of ambiguity made possible by what we have come to call category mistakes, in this case, fitting words to the wrong categories. Aristotle’s example is the word ‘flourishing’ which may appear to be a verb because of its ‘ing’ ending (as in ‘cutting’ or ‘running’) and so belongs to the category of actions, whereas it really belongs in the category of quality. Category confusion was, for Aristotle, the key cause of metaphysical mistakes.

There are seven kinds of sophistical refutation that can occur in the category of refutations not dependent on language: accident, secundum quid , consequent, non-cause, begging the question, ignoratio elenchi and many questions.

The fallacy of accident is the most elusive of the fallacies on Aristotle’s list. It turns on his distinction between two kinds of predication, unique properties and accidents ( Top . I 5). The fallacy is defined as occurring when “it is claimed that some attribute belongs similarly to the thing and to its accident” ( SR 5 166b28). What belongs to a thing are its unique properties which are counterpredicable (Smith 1997, 60), i.e., if \(A\) is an attribute of \(B\), \(B\) is an attribute of \(A\). However, attributes that are accidents are not counterpredicates and to treat them as such is false reasoning, and can lead to paradoxical results; for example, if it is a property of triangles that they are equal to two right angles, and a triangle is accidentally a first principle, it does not follow that all first principles have two right angles (see Schreiber 2001, ch. 7).

Aristotle considers the fallacy of consequent to be a special case of the fallacy of accident, observing that consequence is not convertible, i.e., “if \(A\) is, \(B\) necessarily is, men also fancy that, if \(B\) is, \(A\) necessarily is” ( SR 5 169b3). One of Aristotle’s examples is that it does not follow that “a man who is hot must be in a fever because a man who is in a fever is hot” ( SR 5 169b19). This fallacy is sometimes claimed as being an early statement of the formal fallacy of affirming the consequent.

The fallacy of secundum quid comes about from failing to appreciate the distinction between using words absolutely and using them with qualification. Spruce trees, for example, are green with respect to their foliage (they are ‘green’ with qualification); it would be a mistake to infer that they are green absolutely because they have brown trunks and branches. It is because the difference between using words absolutely and with qualification can be minute that this fallacy is possible, thinks Aristotle.

Begging the question is explained as asking for the answer (the proposition) which one is supposed to prove, in order to avoid having to make a proof of it. Some subtlety is needed to bring about this fallacy such as a clever use of synonymy or an intermixing of particular and universal propositions ( Top . VIII, 13). If the fallacy succeeds the result is that there will be no deduction: begging the question and non-cause are directly prohibited by the second and third conditions respectively of being a deduction ( SR 6 168b23).

The fallacy of non-cause occurs in contexts of ad impossibile arguments when one of the assumed premises is superfluous for deducing the conclusion. The superfluous premise will then not be a factor in deducing the conclusion and it will be a mistake to infer that it is false since it is a non-cause of the impossibility. This is not the same fallacy mentioned by Aristotle in the Rhetoric (II 24) which is more akin to a fallacy of empirical causation and is better called false cause (see Woods and Hansen 2001).

Aristotle’s fallacy of many questions occurs when two questions are asked as if they are one proposition. A proposition is “a single predication about a single subject” ( SR 6 169a8). Thus with a single answer to two questions one has two premises for a refutation , and one of them may turn out to be idle, thus invalidating the deduction (it becomes a non-cause fallacy). Also possible is that extra-linguistic part-whole mistakes may happen when, for example, given that something is partly good and partly not-good, the double question is asked whether it is all good or all not-good? Either answer will lead to a contradiction (see Schreiber 2000, 156–59). Despite its name, this fallacy consists in the ensuing deduction, not in the question which merely triggers the fallacy.

On one interpretation ignoratio elenchi is considered to be Aristotle’s thirteenth fallacy, in which an otherwise successful deduction fails to end with the required contradictory of the answerer’s thesis. Seen this way, ignoratio elenchi is unlike all the other fallacies in that it is not an argument that fails to meet one of the criteria of a good deduction, but a genuine deduction that turns out to be irrelevant to the point at issue. On another reading, ignoratio elenchi is not a separate fallacy but an alternative to the language dependent / language independent way of classifying the other twelve fallacies: they all fail to meet, in one way or another, the requirements of a sound refutation.

[A] refutation is a contradiction of one and the same predicate, not of a name but of a thing, and not of a synonymous name but of an identical name, based on the given premises and following necessarily from them (the original point at issue not being included) in the same respect, manner and time. ( SR 5 167a23–27)

Each of the other twelve fallacies is analysed as failing to meet one of the conditions in this definition of refutation ( SR 6). Aristotle seems to favour this second reading, but it leaves the problem of explaining how refutations that miss their mark can seem like successful refutations. A possible explanation is that a failure to contradict a given thesis can be made explicit by adding the negation of the thesis as a last step of the deduction, thereby insuring the contradiction of the thesis, but only at the cost (by the last step) of introducing one of the other twelve fallacies in the deduction.

2.1.5 Different interpretations

I have given only the briefest possible explanation of Aristotle’s fallacies. To really understand them a much longer engagement with the original text and the secondary sources is necessary. The second chapter of Hamblin’s (1970) book is a useful introduction to the Sophistical Refutations , and a defence of the dialectical nature of the fallacies. Hamblin thinks that a dialectical framework is indispensable for an understanding of Aristotle’s fallacies and that part of the poverty of contemporary accounts of fallacies is due to a failure to understand their assumed dialectical setting. This approach to the fallacies is continued in contemporary research by some argumentation theorists, most notably Douglas Walton (1995) who also follows Aristotle in recognizing a number of different kinds of dialogues in which argumentation can occur; Frans van Eemeren and Rob Grootendorst (2004) who combine dialectical and pragmatic insights with an ideal model of a critical discussion; and Jaakko Hintikka who analyses the Aristotelian fallacies as mistakes in question-dialogues (Hintikka 1987; Bachman 1995.) According to Hintikka (1997) it is an outright mistake to think of Aristotle’s fallacies primarily as mistaken inferences, either deductive or inductive. A non-dialogue oriented interpretation of Aristotle fallacies is found in Woods and Hansen (1997 and 2001) who argue that the fallacies (apparent deductions) are basic to apparent refutations, and that Aristotle’s interest in the fallacies extended beyond dialectical contests, as is shown by his interest in them in the Prior Analytics and the Rhetoric (II 24). What gives unity to Aristotle’s different fallacies on this view is not a dialogue structure but rather their dependence on the concepts of deduction and proof. The most thorough recent study of these questions is in Schreiber (2003), who emphasizes Aristotle’s concern with resolving (exposing) fallacies and argues that it is Aristotelian epistemology and metaphysics that is needed for a full understanding of the fallacies in the Sophistical Refutations .

Francis Bacon deserves a brief mention in the history of fallacy theory, not because he made any direct contribution to our knowledge of the fallacies but because of his attention to prejudice and bias in scientific investigation, and the effect they could have on our beliefs. He spoke of false idols (1620, aphorisms 40–44) as having the same relation to the interpretation of nature that fallacies have to logic. The idol of the tribe is human nature which distorts our view of the natural world (it is a false mirror). The idol of the cave is the peculiarity of each individual man, our different abilities and education that affect how we interpret nature. The idols of the theatre are the acquired false philosophies, systems and methods, both new and ancient, that rule men’s minds. These three idols all fall into the category of explanations of why we may misperceive the world. A fourth of Bacon’s idols, the idol of the market place, is the one that comes closest to the Aristotelian tradition as it points to language as the source of our mistaken ideas: “words plainly force and overrule the understanding, and throw all into confusion, and lead men away into numberless empty controversies and idle fancies” (1620, aphorism 43). Although Bacon identifies no particular fallacies in Aristotle’s sense, he opens the door to the possibility that there may be false assumptions associated with the investigation of the natural world. The view of The New Organon is that just as logic is the cure for fallacies, so will the true method of induction be a cure for the false idols.