- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access Options

- Why Publish with JAH?

- About Journal of American History

- About the Organization of American Historians

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Interchange: Women's Suffrage, the Nineteenth Amendment, and the Right to Vote

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Interchange: Women's Suffrage, the Nineteenth Amendment, and the Right to Vote, Journal of American History , Volume 106, Issue 3, December 2019, Pages 662–694, https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jaz506

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Soon after the U.S. Congress approved the Nineteenth Amendment in early June 1919, state legislatures began to deliberate the question of women's suffrage. Ratification proceedings, which persisted for more than a year, unfolded against a backdrop of extraordinary rage, fear, and uncertainty in the United States. After World War I the decline of manufacturing and the demobilization of soldiers contributed to a painful recession. Across the long red summer, mobs of angry whites terrorized African American communities, lynching dozens of persons and burning homes and churches. Emboldened by union activism and the specter of Bolshevist revolution, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer launched a series of brutal raids, arresting and attempting to deport thousands of immigrant workers. In Congress, the dry majority overrode President Woodrow Wilson's veto of the Volstead Act, heralding a new era of prohibition. Amid this social and political tumult, the Nineteenth Amendment wound its way toward ratification.

What did the amendment, a milestone of American democracy, mean to a nation so deeply committed to white supremacy and immigration restriction? What were its implications for an aspiring empire then exerting military power overseas? How, if at all, did it affect politics and law in the United States?

To promote critical reflection about the Nineteenth Amendment and its many complex legacies, the Journal of American History announces a new series, Sex, Suffrage, Solidarities: Centennial Reappraisals. This series, which will run throughout the coming year, will consist of research articles, special features, and reviews published across the JAH , the JAH Podcast , and Process: a blog for American history . Our theme for the project—sex, suffrage, solidarities—is intended to provoke new questions about the Nineteenth Amendment and the political, economic, and cultural transformations of which it has been a part. Our ambition is to foster creative thinking about suffrage, its discursive and material frameworks, and its often-unanticipated consequences. We intend to examine the intricate linkages among suffrage, citizenship, identities, and differences. We aim to facilitate global, transnational, and/or comparative perspectives, particularly those that compel us to reperiodize or otherwise reassess conventional ways of thinking about campaigns for women's rights and adult citizenship.

To inaugurate this series, we invited a panel of distinguished historians—Ellen Carol DuBois, Liette Gidlow, Martha S. Jones, Katherine M. Marino, Leila J. Rupp, Lisa Tetrault, and Judy Tzu-Chun Wu—to join in conversation about the Nineteenth Amendment, suffrage, and women's political activism more broadly. The Interchange that follows reads by turns as essential historiography, compelling critique, and honest personal reflection. It offers invaluable context for, and analysis of, the study of women's rights in the United States. We are grateful to the participants and to our associate editor Judith Allen for her creative direction of this project.

Ellen Carol Dubois is Distinguished Professor (Emerita) in the Department of History at the University of California, Los Angeles. She is the author or editor of numerous books, including Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women's Movement in America, 1848–1869 (1978), Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony: Correspondence, Writings, Speeches (1981; 3rd ed., forthcoming, 2020), Harriot Stanton Blatch and the Winning of Woman Suffrage (1997), and Woman Suffrage and Women's Rights: Essays (1998). Her next work, Suffrage: Women's Long Battle for the Vote , will be published in 2020. Readers may contact Dubois at [email protected] .

Liette Gidlow is the 2019–2020 Mellon-Schlesinger Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University and an associate professor of history at Wayne State University. She is the author of The Big Vote: Gender, Consumer Culture, and the Politics of Exclusion, 1890s–1920s (2004) and editor of Obama, Clinton, Palin: Making History in Election 2008 (2012). She is now preparing a book manuscript entitled The Nineteenth Amendment and the Politics of Race, 1920–1970 . Readers may contact Gidlow at [email protected] .

Martha S. Jones is the Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor and Professor of History at Johns Hopkins University. She is the author of All Bound Up Together: The Woman Question in African American Public Culture, 1830–1900 (2007) and Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America (2018), and coeditor of Toward an Intellectual History of Black Women (2015). Her next book, Vanguard: A History of African American Women's Politics , will appear in 2020. Readers may contact Jones at [email protected] .

Katherine M. Marino is an assistant professor of history at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her Stanford University dissertation won the Lerner-Scott Prize for the best dissertation in U.S. women's history from the Organization of American Historians; she has since revised and published it as Feminism for the Americas: The Making of an International Human Rights Movement (2019). Readers may contact Marino at [email protected] .

L Eila J. Rupp is Distinguished Professor of feminist studies and associate dean of the Division of Social Sciences at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She has published nine books and more than two dozen articles, among them Survival in the Doldrums: The American Women's Rights Movement, 1945 to the 1960s (1987), co-authored with Verta Taylor, and Worlds of Women: The Making of an International Women's Movement (1997). She is now researching queer college students in the contemporary United States. Readers may contact Rupp at [email protected] .

Lisa Tetrault is an associate professor of history at Carnegie Mellon University. She is the author of the Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women's Suffrage Movement, 1848–1898 (2014), which won the inaugural Mary Jurich Nickliss women's and gender history book prize awarded by the Organization of American Historians. She is working on a book about where and how women's suffrage fit into the political landscape after the American Civil War and another project tracing the genealogy of the Nineteenth Amendment. Readers may contact Tetrault at [email protected] .

J Udy Tzu-Chun Wu is a professor in the Department of Asian American Studies and director of the Humanities Center at the University of California, Irvine. Her books include Dr. Mom Chung of the Fair-Haired Bastards: The Life of a Wartime Celebrity (2005) and Radicals on the Road: Internationalism, Orientalism, and Feminism during the Vietnam Era (2013). She is now researching the career of Patsy Takemoto Mink, the first woman of color to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives. Readers may contact her at [email protected] .

JAH: U.S. historians have closely studied women's suffrage. In the 1960s and 1970s, practitioners of the new women's history wrote extensively about women's enfranchisement and citizenship, as well as the nineteenth-century reform movements that inspired support for—but also opposition to—them. These aspects of political history remained a core priority for women's historians in the 1980s and even the 1990s. The publication of numerous authoritative biographies, organizational studies, and documentary collections enriched our knowledge of these subjects.

As you think back over this field, what are your impressions? What are its distinguishing characteristics? What works, methodologies, or interventions do you find most crucial?

Leila J. Rupp : When I began my graduate work in 1972, it was pretty much possible to read all the existing scholarship on women's history. My introduction to women's suffrage began with Eleanor Flexner's Century of Struggle: The Women's Rights Movement in the United States (1959), Aileen S. Kraditor's The Ideas of the Woman Suffrage Movement, 1890–1920 (1965), Gerda Lerner's The Grimké Sisters from South Carolina: Rebels against Slavery (1967), and the less well-remembered The Puritan Ethic and Woman Suffrage by Alan P. Grimes (1967). As an undergraduate in Herbert Aptheker's class on African American history, I wrote a paper on the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840, relying heavily on Lerner's work to guide me to the sources. Then in 1978 came Barbara J. Berg's The Remembered Gate: The Origins of American Feminism and the now-classic Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women's Movement in America, 1848–1869 , by Ellen Carol DuBois. 1

When I think about this early literature and the subsequent development of the scholarship on suffrage, citizenship, and the women's movement over time, three themes come to mind. The first is the increasing attention to the importance of race, ethnicity, and class. Both Flexner and Lerner, embedded in the progressive Left, attended to issues of race and class, but the racial complexities of the suffrage movement that grew out of the abolitionist struggle did not take center stage, as they would in later literature. DuBois, also coming out of a left feminist context, detailed the failure of a joint struggle for black suffrage and woman suffrage during Reconstruction, the inability of suffragists to forge an alliance with organized labor, and the racism and class bias that underlay and were exacerbated by these failures. Yet, the point of her book is that these developments led to the emergence of an independent women's movement, a positive development in the long run. Since 1978 we have, of course, learned much more about the role that black women, with a foot in both race and gender politics, played in achieving suffrage, from works such as Rosalyn Terborg-Penn's African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850–1920 (1998). 2

A second theme that characterizes the direction of scholarship over the decades is the continuity of the struggle for women's rights in the aftermath of suffrage victory in 1920. For a time, the Nineteenth Amendment seemed to mark the end of organized efforts to win women full citizenship until the emergence of the women's movement in the 1960s. Then a flood of studies addressed the intervening decades. What happened to the women's movement? Did it die out after suffrage was won? Scholarship on the 1920s and beyond—Susan D. Becker's The Origins of the Equal Rights Amendment: American Feminism between the Wars (1981), Nancy F. Cott's The Grounding of Modern Feminism (1987), Dorothy Sue Cobble's The Other Women's Movement: Workplace Justice and Social Rights in Modern America (2004), on labor activism, Cynthia Harrison's On Account of Sex: The Politics of Women's Issues, 1945–1968 (1988), and my work with Verta Taylor, Survival in the Doldrums: The American Women's Rights Movement, 1945 to the 1960s (1987), to name just a few—argued persuasively that it did not die out, and that it took a variety of forms. We came to think of “waves” of the women's movement—the first suffrage wave giving way to the second wave in the 1960s, with third and fourth waves to follow—only to back off from that metaphor to emphasize greater continuity than the rise and fall of waves seems to suggest. 3

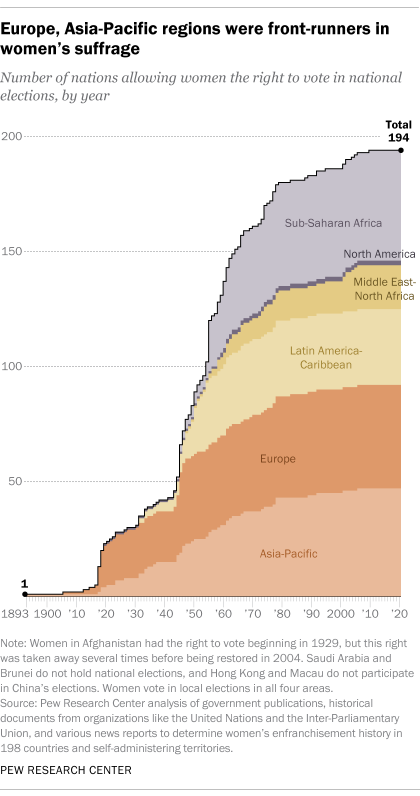

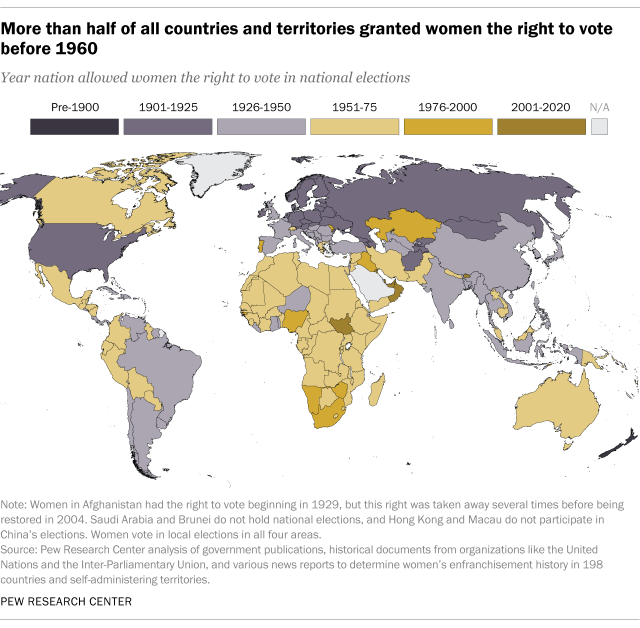

This brings me to a third theme in the scholarship: placing the U.S. suffrage movement and subsequent activism in the context of transnational developments. In my Worlds of Women: The Making of an International Women's Movement (1997), I argued that a history of what I called an international women's movement, which picked up steam in the 1920s and 1930s, showed that rather than “waves” of activism we should think of “choppy seas.” Increasingly, as in other fields of U.S. history, women's historians are paying attention to the global context. Bonnie S. Anderson's Joyous Greetings: The First International Women's Movement, 1830–1860 (2000) makes it impossible to think about the Seneca Falls Convention as a purely American event. To give just a couple of other examples, Allison L. Sneider, in Suffragists in an Imperial Age: U.S. Expansion and the Woman Question, 1870–1929 (2008), connects women's suffrage to U.S. imperialism, and Katherine M. Marino's Feminism for the Americas: The Making of an International Human Rights Movement (2019) details the ways that Latin American feminists in the 1920s and 1930s took the lead in fighting for economic, social, and legal equality on the global stage. 4

Ellen Carol Dubois : I begin by challenging the premise of the question itself. In the revival of women's history inspired by the women's liberation insurgence of the late 1960s into the 1970s, the American woman suffrage movement was not a topic of great interest. I believe that when I published Feminism and Suffrage in 1978, I was alone in reexamining the subject within a full-fledged scholarly monograph. 5

Other suffrage scholars—notably Eleanor Flexner and Aileen Kraditor—though highly influential, were not infused with the energies and the concerns of those women's liberation years. Others of my sister scholars in that pioneering women's generation addressed related subjects—I think particularly of Nancy Cott, Mari Jo Buhle, and Linda Gordon—and I was much influenced by them. But for the most part that entire generation of radical and social historians were not much interested in electoral politics. In our experience, established parties were indistinguishable and ineffective; many of us didn't even vote. Women's liberationists tended to dismiss the suffrage movement for leaving untouched the issues of women's oppression with which we were concerned. My challenge to that dismissal was reflected in the title of my first article on the subject, “The Radicalism of the Woman Suffrage Movement” (1975), published in an early issue of Feminist Studies . In it, I elaborated what I saw as the underlying premise of the suffrage movement, that women were full-fledged and rational individuals, not subservient to family. 6

Following the concerns of my late 1960s political generation, in Feminism and Suffrage I examined the emergence of the suffrage demand in the context of race and class politics. I considered at great length the terrible 1867–1869 schism between black suffrage and woman suffrage advocates. While lamenting the conflict, my conclusion, reflected in the book's title, was that the break freed suffrage leaders—Stanton and Anthony the boldest and most radically feminist of those—to pursue their own political path, no longer deferential to the concerns of racial equality dictated by the Republican party. Again, this argument reflected the experience of my own women's liberation generation as it separated itself from the influence of the male-dominated black power movement.

In my later JAH article, “Outgrowing the Compact of the Fathers: Equal Rights, Woman Suffrage, and the United States Constitution, 1820–1878” (1987), I came to a different conclusion, emphasizing what was lost in 1869, the solidarity of these two movements. By then I was influenced by the first works of black suffrage scholars. Paula Giddings's brilliant When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America (1984) was particularly important for me; I thought of it as the Century of Struggle for black women's history in its scope and bold interpretive stance. Of course, Rosalyn Terborg-Penn's “Afro-Americans in the Struggle for Woman Suffrage” (1977) was very important, but it should be remembered that it was available only as a difficult-to-access dissertation until it was published as a book in 1998. I still believe it necessary, in reconsidering suffrage history, to return to this tragic foundational conflict, especially as what we learn about the traditions of African American suffragism continues to grow. 7

While the racial dimension of the history of woman suffrage has received ever more attention, its class aspects have not, and this is unfortunate. Two of the six chapters of Feminism and Suffrage focused on Anthony's efforts to reach out to wage-earning women and forge a bond with the labor movement of the era. Mari Jo Buhle and Christine Stansell laid the basis for further exploration of these concerns and Diane Balser, Carole Turbin, and Susan Levine pursued the subject, but it has dropped off of suffrage scholars' radar in the current century. As we look over suffragism's seventy-five-year history and its impact on women's political activism after 1920, we should surely be struck by the prominence of women, many of whom began as suffragists, in the twentieth-century labor movement. As suffrage scholars, we should make it our business to dig into the deep, complex, and crucial interactions of race and class in American feminist politics. 8

Martha S. Jones : I came to women's history in the mid-1990s and am a beneficiary of so much work that predated my own. I also came to the field as a historian of African American women. Thus, my starting place was not with, for example, Flexner's Century of Struggle , though I would eventually get to that. Ellen DuBois's Feminism and Suffrage would soon join my list of essential reads. But the work of Terborg-Penn first shaped my thinking. Her 1977 Howard University Ph.D. dissertation, “Afro-Americans in the Struggle for Woman Suffrage,” defined the field long before being published as African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote . 9

Terborg-Penn's study conveyed three enduring insights for historians of black women—indeed, for historians of all women—and the vote. The first was that the work demanded painstaking recovery across an archival terrain not built to preserve black women as political thinkers or activists. Her sheer doggedness in the combing of sources was both an instruction about method and a cautionary tale. The second lesson was that we should not defer to, or trust, the often-cited sources that had long informed histories of women's suffrage. I remember locking horns with fellow graduate students in the 1990s about how to use the six-volume History of Woman Suffrage (a project initiated by Stanton and Anthony in the 1870s, with the last volume published in 1922). A nod here to Lisa Tetrault's important contribution to this point with The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women's Suffrage Movement, 1848–1898 (2014). It was from Terborg-Penn that I learned the politics that animated those volumes and then how to set them aside and avoid being misled. Finally, Terborg-Penn taught me to be unflinching about how racism had infected the minds of some of the best-remembered white women's suffrage activists. I learned that racism had been woven into the fabric of the movement's strategies and tactics. Today, thirty years later, some historians still struggle with how to write about this dimension of the movement. Terborg-Penn put that dilemma squarely in front of us. 10

I also read Paula Giddings's When and Where I Enter in the mid-1990s. It opens with the often-quoted words of the African American scholar and activist Anna Julia Cooper from 1892: “Only the BLACK WOMAN can say ‘when and where I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood … then and there the whole … race enters with me.’” This quotation told us much that we need to know about African American women's politics at the end of the nineteenth century. Cooper and others like her were charting their own way forward as women by the 1890s. Giddings anticipated, if not called into being, the field of African American women's history, which blossomed by the early 1990s. 11

Giddings begins her study with Ida B. Wells's antilynching campaign. This choice is a lesson in the history of women's suffrage. Black activist women such as Wells did not focus on a single issue in their view of women's rights, including the vote. Women's rights were in the service of human rights—rights that extended to women and to men. Giddings recognizes that black women's striving for the vote was interwoven with concerns about antilynching, temperance, the club movement, and Jim Crow. Challenging the periodization of the women's suffrage movement, Giddings's section on Fannie Lou Hamer sent a clear signal: for black women, the movement for suffrage extended to the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment (not unlike ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment) was only one stop along a hard-won route to political power. 12

Neither Deborah Gray White's Ar'n't I a Woman? Female Slaves in the Plantation South (1985) nor Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham's Righteous Discontent: The Women's Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920 (1993) was expressly about women suffrage. Still, I read them as essential studies of how, where, and when black women built political power. Rather than in parlors or conventions, the roots of black women's politics lay in labor, loss, and survival on plantations. There, cruel myths about black women were crafted; the battle against such ideas animated black women's suffrage politics. Higginbotham's study of black Baptist women runs parallel to the histories of the American Woman Suffrage Association ( Awsa ), the National Woman Suffrage Association ( Nwsa ), and the National American Woman Suffrage Association ( Nawsa ), as well as the so-called women's suffrage movement. But we see the Nineteenth Amendment's ratification from a new perspective when we take the point of view of hundreds of thousands of black Baptist women. They did their political work within religious communities. Locating black women's politics on the plantation and in the church changed forever the way we would tell the history of black women and the vote. 13

These threads and more run through my 2007 book, All Bound Up Together: The Woman Question in African American Public Culture, 1830–1900 . What I had learned from the earliest works in African American women's history was how the politics of suffrage, for black women, was always “bound up” with broad concerns, diverse institutions, and differences among and between women, black and white. 14

Lisa Tetrault : When I began reading in this field in the late 1990s, there was little published about post–Civil War women's suffrage. As a result, after I finished Ellen DuBois's necessary Feminism and Suffrage , and several of her seminal articles, I turned to History of Woman Suffrage simply to learn basic historical outlines. I was struck not only by the majesty of Stanton, Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage's recovery and preservation work, but also by their enormous silences and unmistakable emphases. 15

Also in the 1990s, Nell Painter published Sojourner Truth: A Life, a Symbol (1996), which bore heavily on themes of narrativity and power. In her articles as well as her book, she emphasized how Truth had been mythologized rather than remembered as a fully rendered human being and complex historical actor. The origin of the oft-cited “ain't I a woman speech” in primary-document readers (and increasingly online) was often the History of Woman Suffrage , which reprinted that problematic formulation from Frances Dana Gage. Painter's work on narrative and its present-day legacies were deeply influential for me. 16

Rosalyn Terborg-Penn published her highly respected dissertation in that decade as well, African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote . That book strove to unmask and rebuild a basic narrative around women and voting. It too underscored how Stanton and Anthony helped create many of the outlines around something bounded (if still vast) called women's suffrage that nevertheless left out many women and political projects. 17

Over the 1990s and into the early 2000s, scores of new works broke down the idea that women existed in a separate sphere removed from politics. Women need not be domestic and women need not be enfranchised to exercise political power, and women engaged in politics in plenty of places we hadn't thought to look. 18

At the same time, my reading of the rapidly transforming field of Reconstruction-era scholarship signaled the end to a debate that bled from the 1980s into the 1990s: Was women's suffrage radical or conservative? Consequential or inconsequential? The nuanced, fine-grained analyses of power, race, citizenship, gender, freedom, and voting in Reconstruction scholarship, combined with women's political history, underscored that there was no one fixed issue to assess. Whether women's suffrage was radical or conservative, consequential or inconsequential, now seemed beside the point.

Finally, historians such as Elsa Barkley Brown, Eric Foner, Heather Cox Richardson, and the political scientist Victoria Hattam all questioned whether the franchise was even a stable category. Did it too need to be contextualized, interrogated, and historically understood? They clearly answered, “yes.” 19

Liette Gidlow : I have always seen histories of women's suffrage as part of broad histories of political institutions, political culture, women, and gender. Perhaps this is because I came to the study of women's/gendered politics through a different door. When I arrived at my Ph.D. program in history I came with an undergraduate background in political science; work experience in the D.C. Public Defender's office, the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate, and the Ohio legislature; and a feminist consciousness sharpened on issues of campus sexual assault and workplace harassment. My first exposure to women's studies came as an undergrad through feminist literary criticism, and my early interest in race and public policy was cultivated by working with Gary Orfield on issues of racial equity in education and by serving as a staffer to Rep. Julian Dixon in the 1980s. Representative Dixon at the time was the only African American subcommittee chair on the House Appropriations Committee, meaning that all manner of policy issues related to African American constituencies found their way to his desk, and thus mine.

All of these pieces, and a few others, came together in graduate school in the 1990s in a historically grounded way when I started investigating the League of Women Voters' Get Out the Vote ( Gotv ) campaigns of the 1920s. “Politics” clearly extended beyond electoral politics to the full range of ways power was being deployed, and yet “officialness” still mattered. I was especially interested in the nexus of the politics of representation and discourse, on the one hand, and the politics of formal governmental institutions, on the other. How has civic legitimacy historically been constructed, institutionalized, and contested, and what do race, gender, class, sexual preference, religion, and other sources of identity have to do with it? In an era of ostensibly universal suffrage, why did the members of the League of Women Voters feel they needed Gotv campaigns? Why were they trying to get out the votes of middle-class whites, who had the highest turnout, and not those of the working class and/or people of color, who were much less likely to vote? And what did it mean for anyone to be a good citizen in an era in which a majority of eligible voters did not cast ballots, as was the case in 1920 and 1924? Clearly gender, class, and race had a great deal to do with the answers to these questions.

Scholarship on suffrage and Progressive Era women reformers laid crucial foundations for my explorations, and I was especially indebted to work by Paula Baker, Jean Baker, Sarah Hunter Graham, and Robyn Muncy. More theoretical works, in particular Joan W. Scott's “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis” (1986) and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham's “African-American Women's History and the Metalanguage of Race” (1992), helped me think about meaning-making, because I was interested in not only what the vote accomplished but also what enfranchisement signified and how that changed over time. Scholarship outside the conventional categories of “women's history” and “suffrage history” helped me explore the interplay between formal political institutions and processes and the politics of meaning-making. Nancy Fraser's essay on counterpublics, “Rethinking the Public Sphere” (1992), was essential in helping me think about discourse and resistance. Joseph R. Gusfield's The Culture of Public Problems: Drinking-Driving and the Symbolic Order (1981) made me think about the framing of public issues. James C. Scott's Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (1990), and John Gaventa's Power and Powerlessness: Quiescence and Rebellion in an Appalachian Valley (1980) made me think about resistance in new ways. Works by Warren Sussman, Louis Althusser, Clifford Geertz, and Antonio Gramsci made me think about power dynamics embedded in everyday processes of meaning-making. 20

It was really after graduate school that I immersed myself more deeply in historical treatments of women's politics, broadly defined—in part because I was beginning to teach women's history surveys, and in part out of a growing appreciation for the power of narrative and the richness of stories focused on people rather than political institutions. Barbara Ransby's Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (2003), Katherine Mellen Charron's Freedom's Teacher: The Life of Septima Clark (2009), Higginbotham's Righteous Discontent , and Lisa G. Materson's study of black women's electoral activism in the context of the Great Migration ( For the Freedom of Her Race: Black Women and Electoral Politics in Illinois, 1877–1932 [2009]) stand out among many books that helped open the way to my current book project, “The Nineteenth Amendment and the Politics of Race, 1920–1970.” 21

JAH: Professor Gidlow mentioned biographies of Ella Baker and Septima Clark. Are there other biographies that have particularly influenced your thinking about women's suffrage, the Nineteenth Amendment, or women's political activism more broadly?

Jones : I'd like to focus on the role of biography in writing and rewriting the history of women's suffrage. Let me digress just long enough to say that I think nomenclature is important here, so I will use the phrase “women and the vote” rather than “women's suffrage.” With this, I am signaling that my discussions are generally about the broader question of women and the vote, and not about the Nineteenth Amendment in particular. A discussion too narrowly framed by the Nineteenth Amendment relegates many American women to the margins.

African American women's history has produced a robust body of book-length, scholarly biographical works. This genre makes plain that African American women have approached voting rights through campaigns directly organized around suffrage, but they also did so through many other collectives, from clubs and churches to political parties and antislavery societies. Black women's biographies inform my understanding of how to write black women's political history, including their concern with voting rights.

For example, I've come back to Jane Rhodes's biography of Mary Ann Shadd Cary ( Mary Ann Shadd Cary: The Black Press and Protest in the Nineteenth Century , 1998). Rhodes was most interested in Cary's fascinating work as a journalist, but she takes us through a life that includes affiliation with the Nwsa and a role in suffrage campaigns in Washington, D.C. Melba Joyce Boyd's Discarded Legacy: Politics and Poetics in the Life of Frances E. W. Harper, 1825–1911 (1994) is at its heart a literary biography. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was the only African American woman to speak on the record during the fraught American Equal Rights Association meetings of the 1860s. Her interventions are essential to any telling of mid-nineteenth-century suffrage politics. When Harper told those gathered that they were “all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity,” she asserted a human rights vision that remained at the core of black women's thinking about the vote and perhaps remains there today. 22

Nell Painter's magnificent Sojourner Truth refuses to let Truth's memory merely serve the interests of others. We must grapple with Truth's complex, multifaceted life if we are to write about her at all. Painter's insight into racism—both as animus and as paternalism—is an essential lesson. Those who patronized Truth should not be understood as having wholly respected or made space for the entirety of Truth's humanity, even if they incorporated her into women's conventions, the History of Woman Suffrage , and more. 23

Add to these Jean Fagan Yellin's Harriet Jacobs: A Life (2004), which introduces sexual violence as a women's rights issue; two biographies of Harriet Tubman (Catherine Clinton, Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom [2004] and Kate Clifford Larson, Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero [2004]), which remind us that in the last years of her life Tubman stumped for women's suffrage; and Marilyn Richardson's pathbreaking Maria Stewart, America's First Black Woman Political Writer: Essays and Speeches (1987), which wholly resets our periodization of women's rights in the United States with 1832 Boston as a point of origin. Together these biographies are a rich portrait of how black women thought about and worked toward their political rights, while also laboring for human rights. 24

Biographical works often take the point of view of insurgent activists. I'd be remiss if I didn't mention the important work on Ida B. Wells-Barnett, which spans the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and is foundational to my thinking about suffrage versus the vote versus politics versus power. Wells-Barnett was frustrated by Congress and political parties in her antilynching campaign, leading her to adapt an old internationalist vision for her own times. Here, Mia Bay's To Tell the Truth Freely: The Life of Ida B. Wells (2009) and Paula J. Giddings's Ida: A Sword among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign against Lynching (2008) are must-reads. 25

But when I invoke insurgent politics, I am suggesting that the history of black women's politics and power cannot be understood without appreciating those who rejected the politics of the vote for other visions. Again, biographies let us see this clearly. Consider works from Barbara Ransby— Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement and Eslanda: The Large and Unconventional Life of Mrs. Paul Robeson (2013)—and Ula Yvette Taylor— The Veiled Garvey: The Life and Times of Amy Jacques Garvey (2002) and The Promise of Patriarchy: Women and the Nation of Islam (2017). I'd also place Sherie M. Randolph's Florynce “Flo” Kennedy: The Life of a Black Feminist Radical (2015) on a shelf of histories that call into question whether frameworks such as “suffrage” and the “vote” are even central to understanding African American women's history. These insurgent histories are counternarratives that ask hard questions about whether and to what degree women who worked for inclusion and equity in parties and at the polls might have been misled, misguided, or just plain mistaken in their objectives. 26

A few works hit a sweet spot where both the mainstream and the insurgent come together in illuminating ways. First, Barbara Winslow's Shirley Chisholm: Catalyst for Change (2013), gives us a figure who both leveled a radical challenge and worked within U.S. politics, and fought her way in with integrity. And there is Chana Kai Lee's For Freedom's Sake: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer (1999), which also manages to hold on to both the critique of and the striving to gain state power. For yet another figure who just might thread that needle, I'd add Michelle Obama's memoir Becoming (2018). I can't say that Mrs. Obama is at the end of the day an insurgent, but she tells a story about how a black woman strikes a precarious balance when she engages with the mainstream. In this respect, her autobiography reaches all the way back to figures such as Sojourner Truth, black women who tried to make themselves legible to the nation by way of an intersectional analysis of their lives and of American political culture. 27

I'll pitch some biographies still to be written (better yet if they are being written at this very moment): Sarah Mapps Douglass, Jarena Lee, Sarah Parker Remond, Anna Julia Cooper, Julia A. J. Foote, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Nannie Helen Burroughs, and Eliza Ann Gardner all come immediately to mind as women whose lives we know a good deal about and, still, whose biographies would further our understanding of how black women came to politics. There is little room left, it's safe to say, for the old view that black women were not engaged with women's issues or that they somehow placed the interests of black men above their own.

Dubois : A few crucial figures have recently received their first scholarly biographies: Alva Belmont (Sylvia Hoffert's Alva Vanderbilt Belmont: Unlikely Champion of Women's Rights [2011]) and Anna Howard Shaw (Trisha Franzen's Anna Howard Shaw: The Work of Woman Suffrage [2014]). Franzen makes a strong case that much of what we thought we knew about Shaw comes to us through the unflattering lens of Carrie Chapman Catt's evaluation. The biographies and political studies of Ida B. Wells continue to accumulate (Mia Bay's To Tell the Truth Freely , Patricia A. Schechter's Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American Reform, 1880–1930 [2001], and the very interesting work of Crystal N. Feimster in Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching [2011]). Among other leading African American suffragists, Fannie Barrier Williams (in Wanda A. Hendricks's Fannie Barrier Williams: Crossing the Borders of Region and Race [2013]) and Mary McLeod Bethune (in Joyce A. Hanson's Mary McLeod Bethune: Black Women's Political Activism [2013]) now have their first biographies. Importantly, Alison Park is forthcoming with a new biography of Mary Church Terrell. Other especially compelling twentieth-century figures are also the subject of new biographies: Jeannette Rankin (Norma Smith's Jeannette Rankin: America's Conscience [2002]) and Inez Milholland (Linda J. Lumsden's Inez: The Life and Times of Inez Milholland [2004]). 28

Ernestine Rose has a new and interesting biography (Bonnie S. Anderson's The Rabbi's Atheist Daughter: Ernestine Rose, International Feminist Pioneer [2017]). I've also dug a little into biographies of lesser-known figures such as Lillie Devereux Blake (Grace Farrell's Lillie Devereux Blake: Retracing Life Erased [2002]), Belva Lockwood (Jill Norgren's Belva Lockwood: The Woman Who Would Be President [2007]), and Emma Devoe (Jennifer M. Ross-Nazzal's Winning the West for Women: The Life of Suffragist Emma Smith DeVoe [2011]). There are several new studies of Alice Paul (Mary Walton's A Woman's Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot [2010], Christine Lunardini's Alice Paul: Equality for Women [2013], and Jill Zahniser and Amelia R. Fry's Alice Paul: Claiming Power [2014]), and one of Lucy Stone (Sally G. McMillan's Lucy Stone: An Unapologetic Life [2015]). I particularly note the absence from this list of books on working-class suffragists such as Leonora O'Reilly and Rose Schneiderman. There is now, however, a much-needed study of Mary Kenney O'Sullivan (Kathleen Nutter's The Necessity of Organization: Mary Kenney O'Sullivan and Trade Unionism for Women, 1892–1912 [2000]). 29

Two recent biographies have appeared (Lori D. Ginzberg's Elizabeth Cady Stanton: An American Life [2009], and Vivian Gornick's The Solitude of Self: Thinking about Elizabeth Cady Stanton [2005]). With the publication of Ann D. Gordon's scrupulously edited and annotated six-volume Selected Letters of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (1997–2013), hopefully more should be forthcoming. Also in the category of important biographical resources, Thomas Dublin and Kathryn Kish Sklar's incredible Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600–2000 has done spectacular work in using crowd sourcing to build biographical dictionaries of relatively unknown African American suffragists, Congressional Union/National Woman's party militants, and the moderates of Nawsa . 30

JAH: How have historians' approaches to women's suffrage and women and the vote evolved since this first effusion of scholarship? What, if anything, has changed in the early twenty-first century?

Gidlow : I see the last twenty-five-years or so of scholarship as having replaced a single dominant narrative that was constrained and bounded with a profusion of perspectives that transcend many of those limits. In its purest form, the classic interpretation treated the suffrage struggle as a self-contained American story that began in 1848 in Seneca Falls and, after many trials and tribulations, was brought to a triumphant conclusion in 1920 by heroic middle-class and elite white women with ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. Scholarship, mostly in the 1990s and early 2000s, chipped away at the temporal, geographical, racial, and class boundaries of the prevailing narrative through key works such as Ginzberg's Untidy Origins: A Story of Woman's Rights in Antebellum New York (2005), Cott's “Across the Great Divide” (1990), Anderson's Joyous Greetings (2000), Terborg-Penn's African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote (1998), Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore's Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896–1920 (1996), and DuBois's Harriot Stanton Blatch and the Winning of Woman Suffrage (1997). By the mid-2000s, the classic narrative gave way to bold new interpretations that borrowed insights from scholarship on historical memory, borders, and other fields. It was hardly possible to privilege 1848 after Tetrault's The Myth of Seneca Falls , or to see suffrage as a purely domestic political issue after Sneider's Suffragists in an Imperial Age . As the centennial of ratification approaches, more work is connecting woman suffrage to, or integrating it into, accounts of other key figures and issues in U.S. and global history, such as Charles Darwin and evolution (Kimberly A. Hamlin's From Eve to Evolution: Darwin, Science, and Women's Rights in Gilded Age America [2014]), and, in my own work, the mid-twentieth-century civil rights movement. These deep connections to other issues are powerful evidence, if any was needed, that “the” history of woman suffrage is not peripheral to national or transnational histories, but central and essential. 31

Katherine M. Marino : Numerous women's groups have pushed for the right to vote as one goal in multipronged and often-global platforms for birth control, labor rights, socialism, world peace, temperance, child welfare, freedom from sexual violence, antilynching legislation, and racial justice. Works that shine a light on the vital political work of African American women's rights activists that included and expanded beyond suffrage include Jones's All Bound Up Together ; Estelle B. Freedman's Redefining Rape: Sexual Violence in the Era of Suffrage and Segregation (2013); Feimster's Southern Horrors ; Brittney C. Cooper's Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women (2017); and Materson's For the Freedom of Her Race , in addition to already-named works by Terborg-Penn, Painter, and Giddings, and many others. 32

Vicki L. Ruiz's American Historical Review article on Luisa Capetillo and Luisa Moreno (“Class Acts: Latina Feminist Traditions, 1900–1930”), Maylei Blackwell's ¡Chicana Power! Contested Histories of Feminism in the Chicano Movement (2011), Gabriela González's Redeeming La Raza: Transborder Modernity, Race, Respectability, and Rights (2018), and Emma Pérez's The Decolonial Imaginary: Writing Chicanas into History (1999) have explored the political work of turn-of-the-century Mexican, Mexican American, Puerto Rican, and Latinx women who took up “the woman question” alongside other goals for the health, education, and safety of their communities. Works that demonstrate the interrelationship between suffrage organizing and international peace, labor, and socialist movements include Rupp's Worlds of Women ; Ellen DuBois's 1991 New Left Review essay “Woman Suffrage and the Left”; Julia L. Mickenberg's American Girls in Red Russia: Chasing the Soviet Dream (2017) and her 2014 JAH article, “Suffragettes and Soviets”; Anderson's The Rabbi's Atheist Daughter ; Annelise Orleck's Common Sense and a Little Fire: Women and Working-Class Politics in the United States, 1900–1965 (1995); and Melissa R. Klapper's Ballots, Babies, and Banners of Peace: American Jewish Women's Activism, 1890–1940 (2013), to name just a few. 33

These histories show us that suffrage was not one movement, but multiple movements. They also challenge the wave metaphor, showing us that U.S. feminism in the early twentieth century was not defined by a quest for the Nineteenth Amendment. At the same time, demands for political rights and equality have been an integral and ongoing part of U.S. feminisms.

These readings have also been useful for my own work on Pan-American feminism in the interwar years. On the heels of the Nineteenth Amendment, Anglo-American women, believing they were the global leaders of feminism because of their recent suffrage victory, sought to dictate the terms of feminism to their Latin American counterparts. U.S. leaders often instructed Latin American feminists to make a single-minded push for suffrage. However, Latin American feminists exerted their own broader meanings of feminismo , defined not only by equality under the law but also by social and economic rights, and anti-imperialism, among other goals. Anti-imperialism was a driver of suffrage activism in Latin America, especially in Central America, in the 1910s and 1920s. In the mid-1930s–1950s period, when suffrage passed in most Latin American countries, antifascism and Popular Front coalitions of socialist and labor groups vitally energized women's suffrage campaigns. This Popular Front Pan-American feminist movement was critical to developing frameworks for international human rights. It advocated a broad meaning of international human rights—for political, civil, social, and economic rights for men and women, and antidiscrimination based on race, sex, class, or religion—that it pushed into inter-American venues and eventually into the founding of the United Nations. In the Un , a group of Latin American feminists were critical to inserting women's rights in the founding 1945 Un Charter and to promoting the inclusion of both women's and human rights. This is just one example of how it can be useful to de-center the United States, while also keeping in mind the relationship between U.S. suffrage and imperial histories. 34

Dubois : I have been impressed with several clusters of recent scholarship. Political scientists are delving into the theoretical foundations of suffrage thought and the impact of enfranchisement on voting rates. Counting Women's Ballots: Female Voters from Suffrage through the New Deal (2016), by J. Kevin Corder and Christina Wolbrecht, uses sophisticated new techniques to assess how women voted in their first presidential elections. They break the vote down by state and region and thus offer an alternative to the oversimplified, long-standing, and unsubstantiated claim that women did not make use of their new voting rights. They and others have suggested that we pay attention to the role played in the political realignment of 1932 by the massive expansion of the electorate that the Nineteenth Amendment effected. Republicans had long claimed to be the party that supported woman suffrage, but that claim had grown very thin by the late 1920s. It is not without significance that while Herbert Hoover promised the first woman cabinet member, Franklin D. Roosevelt was the one who appointed her. 35

I noted in my first answer that working-class suffragism could use more research. By contrast, there is much fine scholarship on upper-class suffragism. In addition to Sylvia Hoffert's Belmont biography already noted, Johanna Neuman has written about “Gilded Age socialites” ( Gilded Suffragists: The New York Socialites Who Fought for Women's Right to Vote , 2017), and Joan Marie Johnson has done very good work on suffrage philanthropy ( Funding Feminism: Monied Women, Philanthropy, and the Women's Movement, 1870–1967 , 2017). Somewhat related is Brooke Kroeger's work on male suffrage supporters ( The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote , 2017). Note that these last three books focus on New York suffragism, as does the work of Susan Goodier ( No Votes for Women: The New York State Anti-suffrage Movement [2017] and, coauthored with Karen Pastorello, Women Will Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York State [2017]). Almost every other state has yet to receive its own study, which will be of great help in understanding the grassroots of suffragism. 36

Judy Tzu-Chun Wu : I will focus on the value of citizenship, both for those excluded from eligibility and political rights due to race and immigration status as well as for those who had citizenship forced upon them by the U.S. Empire. These perspectives illuminate how whiteness and settler colonialism underlie so-called women's suffrage. I focus my comments primarily on Asian American and Pacific Islander women, although forms of racialized exclusion and forced colonization resonate more broadly.

The ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 happened just four years before the 1924 Immigration Act, which systematically codified earlier laws and court cases that denied Asian immigrants entry into the United States and deemed them “aliens ineligible for citizenship.” This designation, a legal status that influenced social and cultural representations of Asian people in the United States, held implications not only for the right to vote but also for the right to serve on juries, own property, marry interracially, and so on. For Asian women, whose status was “covered” by that of their husbands or fathers, their alienness by association not only translated to distinctly gendered barriers at the border (where they were monitored for gender-inappropriate behavior and suspected of prostitution) but also affected their legal rights (U.S.-born women would lose their citizenship if they married men who were aliens ineligible for citizenship). The scholarship of Sucheng Chan, Martha Gardner, Judy Yung, and others reveal how U.S. citizenship fundamentally represented racialized and gendered privileges, which were out of grasp for those deemed forever foreign. This issue continues to be relevant, given the substantial undocumented population in the United States, including Asian Americans, the fastest growing segment of this community. 37

It is also important to note instances of forced incorporation into the U.S. Empire, which conferred the unwanted gift of unequal legal rights. As Allison Sneider, Kristin Hoganson, and others argue, the U.S. women's suffrage campaign blossomed in the contexts of U.S. westward expansion and overseas empire. White suffragists insisted on their political rights in response to U.S. colonial endeavors. As Susan B. Anthony stated in her 1902 testimony to the U.S. Senate Committee on Women's Suffrage, “I think we are of as much importance as are the Filipinos, Porto Ricans, Hawaiians, Cubans, and all of the different sorts of men that you have before you. When you get those men, you have an ignorant and unlettered people, who know nothing about our institutions.” As the U.S. expanded into the Caribbean and across the Pacific, Filipinos became “nationals,” neither citizens nor aliens. The last Native Hawaiian monarch, Queen Liliuokalani, was forcibly deposed by a coalition of white businessmen, U.S. military forces, and Christian missionary interests. Given this history of U.S. Empire, coerced inclusion, and racialized arguments for white women's suffrage, what is the value of attaining “equal” rights within an inherently unjust nation? 38

To help address these legacies of racial exclusion and imperial incorporation, I especially appreciate the work of Cathleen Cahill, whose forthcoming book focuses on women of color, particularly indigenous, Latina, and Asian/American women who advocated for suffrage. I'm also in awe of the substantial black women's suffrage project that Dublin and Sklar have launched as part of the Women and Social Movements in the United States journal. 39

I explore the ramifications of race and empire in a political biography of Patsy Takemoto Mink, the first woman of color U.S. congressional representative and the namesake for Title IX. Mink was elected from Hawaii and lived through the islands' transition from “territory” to “state.” She also articulated what I describe as a Pacific feminism. Mink's denizenship from islands in the middle of the Pacific framed how she understood political issues, ranging from Cold War militarism, race relations, environmentalism, and women's politics. The racial, the colonial, and the international were intertwined for Mink, a third-generation Japanese American, as they are for other racialized individuals who arrived on U.S. shores or whose homelands were crossed by U.S. borders. 40

Tetrault : I appreciate Judy Wu's reminder that extension of suffrage “rights” also implied colonization in the lives of many. In my reading about native and indigenous peoples voting “rights,” gaining citizenship and the vote meant the loss or diminishment of tribal sovereignty. We need to be careful not to reify the whiteness of the standard narrative by cheerfully adding additional dates—when native women “got” the vote, for example—or by treating voting as if it is always, on the face of it, desirable. The latter idea betrays a kind of triumphant American exceptionalism that often runs through discussions about voting “rights.” More work is needed here. Certainly, once enfranchised, colonized people creatively figure out how to leverage the ballot in their lives, for resistance and survival. And this too is an important part of the story. 41

Leila J. Rupp posed this question: Liette Gidlow's comments about the breakdown of a dominant narrative of suffrage as a self-contained and American story, along with Judy Wu's focus on the history of both systematic exclusion and imperialist incorporation of Asian and other women of color, raises for me these questions: Do we have anything to celebrate about the suffrage victory? Given the complicated history of suffrage that has emerged, are there positive developments we can point to regarding women's enfranchisement? What did women's votes bring to politics?

Gidlow : There is a sense that somehow the Nineteenth Amendment was rather a disappointment, that it doubled the electorate but didn't really change anything, in part because many women did not vote, and because those who did vote did not vote as a bloc. That is, that the Nineteenth Amendment did not produce a “women's vote.”

I argue, however, that over time a women's voting bloc did emerge, one that is cross-class and stable, with high voter turnout and a sharp preference for one party. That bloc emerged not among white women, but rather among African American women. It took the better part of a century, but by the early twenty-first century “the” black women's vote had become transformative in U.S. politics, just as southern white supremacists who had feared woman suffrage a century ago had feared.

The fear that the Anthony Amendment would enfranchise southern black women and open the door to the return of southern African American men to the polls was central to the debate over the Anthony Amendment in the late 1910s in Congress and in 1920 in Tennessee. In 1915 the Richmond ( Va ) Evening Journal editorialized that if the Anthony Amendment became law, “twenty-nine counties will go under negro rule,” a development that would force “the men of Virginia to return to defending white supremacy through fraud and violence” and “return to the slimepit from which we dug ourselves.” As I pointed out in a 2018 article in the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era , southern members of Congress routinely cited these concerns when they explained their opposition to sending the amendment to the states for ratification (“The Sequel: The Fifteenth Amendment, the Nineteenth Amendment, and Southern Black Women's Struggle to Vote”). Kimberley Hamlin develops evidence along these lines beautifully in her forthcoming book, Free Thinker: Sex, Suffrage, and the Extraordinary Life of Helen Hamilton Gardener . And Elaine Weiss's account of the ratification battle in Tennessee ( The Woman's Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote , 2018) shows frequent recourse to the fear of black women's—and men's—votes. When black women showed up in the fall of 1920 to register and vote—and they did show up—local papers reported near panic at their surging interest. 42

In some locations, the sheer number of registrants suggests that the mobilization of black women voters was cross-class. A letter writer to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ( Naacp ) noted that six hundred African American women tried to register in Caddo Parish, Louisiana—a breadth that suggests working-class mobilization—but that fewer than five succeeded, most of those, as the letter-writer states, “on account of “thair propity.” In Jacksonville, Florida, thanks to painstaking data collection by Paul Ortiz, we have direct evidence of cross-class mobilization ( Emancipation Betrayed: The Hidden History of Black Organizing and White Violence in Florida from Reconstruction to the Bloody Election of 1920 , 2005). There, the occupations with the most female registered voters were laundry workers, maids, and cooks, but the list of registrants also included dressmakers, clerks, and teachers. 43

Voter registrars employed a variety of strategies to disfranchise middle- and upper-class African American women. They had the discretion to decide how to test applicants and whether they had done well enough to pass. Class status alone did not secure voting rights for African American women in the South after ratification. Some black women turned then to gender-based strategies, trying to enlist the help of white women who had worked and sacrificed to enact woman suffrage. They quickly learned that there was little gender solidarity across racial lines. The two major suffrage groups ( Nawsa , reconstituted in the summer of 1920 as the League of Women Voters, and the National Woman's party) both declined to get involved. 44

Class-based strategies did not work, and gender-based strategies did not work, so African American women redoubled their efforts to push forward race-based strategies, working with African American men through the Naacp , churches, institutions of higher education, and other organizations. They attacked the white primary and made for themselves a place in the “Roosevelt” Democratic party. Women such as Ella Baker and Septima Clark developed educational programs that helped community members pass literacy tests. After the Voting Rights Act, despite ongoing resistance, they registered and mobilized en masse. Their votes made a difference; sometimes they made the difference. 45

It took the better part of a century, but the Nineteenth Amendment did produce a “women's vote.” Since at least the 1990s, African American women have displayed the most intense partisan preference of any demographic group. In 2008 and 2012, they had the highest voter turnout of any group and made crucial contribution to Barack Obama's historic presidential wins. When southern white supremacists opposed the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, they feared the power of black women's votes. A century later we can see that their fears were well-founded.

Marino : When I teach U.S. women's and gender history, I trouble the assumption that the Nineteenth Amendment was the major turning point that students sometimes assume it was. I ask my students to consider a question my adviser Estelle Freedman instilled in us: “Which women?”—Which women benefitted from the Nineteenth Amendment? As Judy Wu has pointed out, immigration restrictions meant that most Asian and Asian American women did not. Polling taxes, literacy requirements, and violence constricted citizenship rights for many African Americans in the South. The deportation of Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the 1930s further eroded men's and women's citizenship rights. Relatedly, the racism of white suffrage organizations, their use of U.S. imperial expansion as justification for a federal suffrage amendment, and their failure to organize intersectionally in the wake of suffrage, challenge the notion that the Nineteenth Amendment was a major turning point. 46

At the same time, I also emphasize that movements for suffrage were extremely important in chipping away at the legal exclusion of women from political citizenship, and that suffrage demands were a key part of broader movements that upheld multiple goals. To understand the stakes of women's suffrage it helps to realize that figures as diverse and as radical as Sojourner Truth, Clara Zetkin, Ida B. Wells, and Jovita Idár were demanding it and to great effect. One example: In 1913, the same year she rejected white suffragists' instructions to march at the end of the Washington, D.C., parade, Wells founded the first African American suffrage organization in Chicago, the Alpha Suffrage Club. That club registered over seven thousand new African American women voters who helped elect the city's first black alderman. It is important to understand that Wells's suffrage and electoral activism was connected to her activism against lynching and sexual violence. 47

Tetrault : I appreciate Liette Gidlow's deft summary of the field: from a dominant, contained narrative to a profusion of narratives that can no longer be contained and now spill over into so many other stories. At the same time, this centennial is causing quite a bit of confusion, as the old, contained narrative of the Nineteenth Amendment extending the “right to vote” to women keeps intruding onto how we now brand the amendment. I think the conventional story has contributed negatively in unseen ways to understandings of American history, by lulling (often white) Americans into believing that a “right to vote” exists. Historians constantly refer to suffrage activism as women pursuing and then winning “the right to vote.” That framing enshrines this right as something that has been realized, when it has not. It's no surprise, then, that a majority of white Americans today think that voter suppression is not currently underway, even as it is sharply on the rise. 48

Bringing the text of the Nineteenth Amendment into anniversary discussions helps us see a place where we are still getting tripped up by older, inherited—and triumphant—narratives. When the amendment was drafted in 1878 it might have been worded affirmatively, as a directive: the federal government shall protect the right of women to the elective franchise. But it wasn't, owing to complicated factors. Instead, the Nineteenth Amendment, like the Fifteenth Amendment upon which it was modeled, is negatively worded. The Fifteenth Amendment says states can't bar voting on grounds of “race,” while the Nineteenth Amendment says states can't bar voting on grounds of “sex.” The Nineteenth Amendment doesn't enfranchise anyone directly. It works indirectly, by removing the word “male” from state constitutions, where voting qualifications were defined. That's it. It's true that the opening of the short, thirty-nine-word amendment (like the Fifteenth Amendment) references a “right to vote,” but that right did not, in fact, exist. It's an illusory referent point, something the amendment leaves imagined rather than demanded. The Constitution leaves the appointment of voters up to individual states. It does not contain the right to vote.

Leading white suffragists could have seen how flaccid the Fifteenth Amendment turned out to be in protecting black men's votes, as southern states legally disfranchised them on other grounds—something permitted by the very narrow and negative wording of that amendment. Yet, even as the shortcomings of the Fifteenth Amendment became clear over the 1880s and 1890s, neither Stanton nor Anthony, nor any other suffragists, sought to revise the text of the proposed federal amendment. They left it modeled on the Fifteenth Amendment, even as that amendment crumbled before them.

This wording is, I think, a concession to American racism. Historians talk about the amendment's effect but rarely about its creation. Stanton, in particular, had always believed that voting should be extended to the “educated” and kept from the “ignorant” (read, immigrants and many folks of color). Stanton supported discrimination in voting, and the amendment ultimately made allowances for that (explored in my current work). Future, mainstream white suffragists made these same allowances by not revising the amendment's text.

Removing “male” from state-defined voter qualifications, by declaring that requirement unconstitutional, was a huge victory, particularly in an era when discrimination on the grounds of sex was thought not only permissible but also necessary given that women and men were understood to be vastly different biological entities. But how can we tell a story today that doesn't falsely enshrine a “right to vote” and still honor this amendment? There, I think, we still have work to do.

Finally, that we still narrate the mainstream suffrage story as a story of the federal amendment is, I think, another legacy of the earlier dominant narrative that centers Stanton and Anthony. The federal amendment was their baby, but many other suffragists—especially in the forgotten American Woman Suffrage Association—thought it was unconstitutional, because the Constitution clearly gave authority over voting to the states, something not discussed in references to their promotion of a state strategy.

When the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920, women were already voting, in some form, in all but eight states. We have very little history of how women on the ground, including women of color, were trying to create and safeguard a “right” to a ballot. What we do know is that we can't talk about women's first election as if it happened after 1920; millions of women were already voting before then.

If we broaden our focus beyond the federal amendment, we see that there is no single date when women gained ballot access. This is a more accurate, if a much less satisfying, story.

Dubois : It bears emphasis that the wording of the amendment that Lisa critiques was offered by senators, not by Stanton and Anthony. Through much of the 1870s, Stanton and Anthony advocated affirmative wording linking women's voting to universal national suffrage, but that phrasing received no support in Congress.

Should we celebrate the Nineteenth Amendment? I must say that I honestly don't understand how this question can be asked and so how to answer it. Perhaps it is intended as a productive provocation. Nonetheless, my strong position is that any significant political goal that women wished to achieve, any effort to effect social change for women or for the larger society, could not be secured without the fundamental tool of democratic society, the franchise. Would we want to envision a counterfactual history in which American women would wait, like the women of France, Italy, Mexico, Belgium, and many other countries, until after the Second World War to vote? Nor can we reasonably claim that these, or our, or virtually any other national enfranchisements of women could have occurred without the often-long-running, organized demands by women themselves.

The Fifteenth Amendment certainly did not secure African American men's right to vote against attack and required another century of struggle to fully reinstate it. Nonetheless, I doubt any of us would think it a better outcome if de jure suffrage rights had not been won during Reconstruction. In the modern world, where even autocratic leaders must make use of the popular vote, no one except an occasional far-right pundit seeking attention seriously asks whether women's enfranchisement should have happened. Women's votes are such a rich prize that all sides fight furiously to claim them.

Gidlow : Voting is hardly the whole story of American democracy and political participation. But there is a singular quality to enfranchisement because it certifies the enfranchised person's status as a legitimate decision maker in civic affairs. (Judith Shklar's classic 1991 work, American Citizenship: The Quest for Inclusion , is so valuable here.) The imprimatur of official status matters, even if the act of voting does not achieve all we might wish. This is not to say that the import of enfranchisement is merely symbolic. When women cast votes, they are helping make decisions that everyone, including men, must abide. This power remains deeply contested, in politics and well beyond, even a century after ratification. 49

Jones : Should we celebrate the Nineteenth Amendment anniversary? I don't think “celebration” is a historian's approach to the past—it leans too far in the direction of hagiography for my tastes. I don't even think, as I've written elsewhere, that commemoration is the work of historians. On this point I am indebted to Michel-Rolph Trouillot and his devastating analysis of the 1992 “celebration” of Christopher Columbus in Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (1995). Anniversary dates are an opportunity to teach history to a broader public. Some of what we teach may encourage or fuel commemoration or celebration. But if we give in to the tug of mythmaking and sanitization that these sort of rituals require, we are doing something else. 50

JAH: In what ways have histories of women and the vote contributed to our broader understanding of U.S. history? What difference has this work made to the field at large?

Dubois : Regarding the beginning and end of the suffrage period, historians of the United States have done a modestly good job of paying attention to suffrage historiography. By beginning, I mean from the period of antislavery activism to the Reconstruction era, 1836–1876. The abolitionist origins of women's rights and the controversy surrounding woman suffrage and the Fifteenth Amendment have both drawn historians' attention. I recently noticed a very good law review article by Adam Winkler on the suffrage New Departure, which made an innovative constitutional argument for women's enfranchisement largely based on the Fourteenth Amendment, as an early and underappreciated episode in the reenvisioning of the Constitution as a “living document,” an approach not recognized by virtually any jurists at the time (“A Revolution Too Soon: Woman Suffragists and the ‘Living Constitution,’” 2001). By end, I mean the Progressive Era, 1900–1920. Women's political activism in those years is so central to the social welfare dimension of state and national policies, it is hard to ignore. 51

The middle period of suffrage activism has not been integrated into general U.S. history for two reasons. First, suffrage historiography is weak in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, perhaps because there is little suffrage radicalism to inspire modern students of the movement. Second, U.S. history overall is weak in this period, with no consensus on how to narrate the era, or even what to call it: the age of class division, the age of industrialization, the woman's era, the Gilded Age, the racial nadir, post-Reconstruction reaction?

Jones : One approach to this question is to ask more directly: How have histories of women's suffrage contributed to our understanding of women's politics and power? Once we do, at least two important things happen. First, our attention is drawn away from so-called women's suffrage associations, and we focus on sites where black women were struggling over their political rights and power. This is why, for example, the Ann D. Gordon's edited collection African American Women and the Vote, 1837–1965 (1997) ranges from the 1837 Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women to the Voting Rights Act. That volume examines black women not only in suffrage associations but also throughout African American public culture: in the colored convention movement, antislavery societies, churches, the antilynching movement, the club movement, and more. To answer the question directly, the history of women's suffrage (and its shortcomings) encouraged historians of black women to rewrite the histories of black public culture as histories of women and to better understand the full range of how and where women's politics unfolded. 52

Today, in the field of African American women's history, a great deal of important work is being done on women's politics and power, but not very much of this work focuses on the history of suffrage or of voting more generally. This stands in contrast to the great interest in contemporary voter suppression, treated in Carol Anderson's excellent One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy (2018). Still, we don't think of the era before the Nineteenth Amendment as one of “voter suppression” even as many black women were barred from the polls as women after the Civil War. The histories that stick closest to black women and the vote are those that are most concerned with black women's intellectual history, such as Cooper's Beyond Respectability and Treva Lindsey's Colored No More: Reinventing Black Womanhood in Washington, D.C . (2017). 53

African American women's history opens up onto of a set of questions, we might even say a skepticism, about political histories that center too firmly on the vote, political parties, and the state. The vast, ubiquitous, and enduring ways racism and white supremacy have been woven into people, ideas, and institutions have required that the field always understand how black Americans critiqued and then worked against racism and white supremacy. That is to say that an essential counterpoint to histories of the vote are histories of how voting was not enough.

I see the exciting new work on black women's internationalism as the cutting edge of new histories of politics and power. Examples include Keisha N. Blain's Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom (2018) and the volume edited by Blain and Tiffany M. Gill, To Turn the Whole World Over: Black Women and Internationalism (2019). These histories defy conventional frameworks such as that of the nation-state or of electoral politics. As Grace V. Leslie's essay in that collection (“‘United, We Build a Free World,’”) illustrates, even a figure such as Mary McLeod Bethune, whom I associate with the National Association of Colored Women and Fdr 's “black cabinet,” must be remembered for her broad political vision, which included a critique of racism and colonialism and was aimed at linking women across the black diaspora. The vantage point of this work dovetails importantly with that of Marino's new Feminism for the Americas . 54

Has the history of black women and the vote remade U.S. political history? The answer is yes and no, and perhaps that is just right. Certainly we have made the case for black women in mainstream politics—from suffrage to the vote, parties, and the state. We've helped expand the notion of political history by making the case for insurgent politics as part of the American story. And we've even pressed on the geographies of political history, insisting on a politics rooted in the United States but transnational in its vision and its aims.

Marino : Histories of women's politics have, on a fundamental level, contributed to a recognition that to understand politics or political citizenship, we need to understand gender, race, class, and ethnicity, among other hierarchies of power. Decades of scholarship have shown that these areas of focus are not separate. (Women's and gender histories, however, too often still get tokenized.)

To point to a few useful contributions, Paula Baker's 1984 AHR essay, “The Domestication of Politics,” demonstrated that a changing understanding of what counted as “politics” in the United States was wrought by women's Progressive Era civil and social engagement and by a burgeoning welfare state. This “domestication” of politics abetted the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. More recently, Dawn Langan Teele's book, Forging the Franchise: The Political Origins of the Women's Vote (2018), provides a fine-grained comparative analysis of how women's suffrage was accomplished in England, France, and the United States. It underscores the importance of strategic maneuverings and alliances between suffragists and political parties seeking to gain power. Blain's Set the World on Fire not only explores the range of black nationalist women's engagements in the United States and transnationally around a range of goals but it also places women at the center of black nationalism. 55

These histories have also increasingly demonstrated that the “personal” is indeed “political.” Freedman's Redefining Rape argues that the definition of rape—including the race-, class-, and gender-specific notions of who can perpetuate it and who be a victim of it—is fundamental to political citizenship. Her book underscores the connections between sexual violence, gender, race, the vote, and broad meanings of political citizenship. “Suffrage” is in the subtitle, and she examines a diverse group of female and male activists, black and white, including suffragists from the mid-nineteenth century to the early twentieth century who sought to expand the definition of “rape” beyond the typical one of this period: a forcible attack on a chaste white woman by a nonwhite male perpetrator. The book explores the importance of women's voting power at the state and national levels to the passage of statutory rape laws. It also explains how the right to serve on a jury for white women and African American men and women was critical both to addressing sexual violence and to changing this narrow definition. 56