Research vs. Study

What's the difference.

Research and study are two essential components of the learning process, but they differ in their approach and purpose. Research involves a systematic investigation of a particular topic or issue, aiming to discover new knowledge or validate existing theories. It often involves collecting and analyzing data, conducting experiments, and drawing conclusions. On the other hand, study refers to the process of acquiring knowledge or understanding through reading, memorizing, and reviewing information. It is typically focused on a specific subject or discipline and aims to deepen one's understanding or mastery of that subject. While research is more exploratory and investigative, study is more focused on acquiring and retaining information. Both research and study are crucial for intellectual growth and expanding our knowledge base.

Further Detail

Introduction.

Research and study are two fundamental activities that play a crucial role in acquiring knowledge and understanding. While they share similarities, they also have distinct attributes that set them apart. In this article, we will explore the characteristics of research and study, highlighting their differences and similarities.

Definition and Purpose

Research is a systematic investigation aimed at discovering new knowledge, expanding existing knowledge, or solving specific problems. It involves gathering and analyzing data, formulating hypotheses, and drawing conclusions based on evidence. Research is often conducted in a structured and scientific manner, employing various methodologies and techniques.

On the other hand, study refers to the process of acquiring knowledge through reading, memorizing, and understanding information. It involves examining and learning from existing materials, such as textbooks, articles, or lectures. The purpose of study is to gain a comprehensive understanding of a particular subject or topic.

Approach and Methodology

Research typically follows a systematic approach, involving the formulation of research questions or hypotheses, designing experiments or surveys, collecting and analyzing data, and drawing conclusions. It often requires a rigorous methodology, including literature review, data collection, statistical analysis, and peer review. Research can be qualitative or quantitative, depending on the nature of the investigation.

Study, on the other hand, does not necessarily follow a specific methodology. It can be more flexible and personalized, allowing individuals to choose their own approach to learning. Study often involves reading and analyzing existing materials, taking notes, summarizing information, and engaging in discussions or self-reflection. While study can be structured, it is generally less formalized compared to research.

Scope and Depth

Research tends to have a broader scope and aims to contribute to the overall body of knowledge in a particular field. It often involves exploring new areas, pushing boundaries, and generating original insights. Research can be interdisciplinary, involving multiple disciplines and perspectives. The depth of research is often extensive, requiring in-depth analysis, critical thinking, and the ability to synthesize complex information.

Study, on the other hand, is usually more focused and specific. It aims to gain a comprehensive understanding of a particular subject or topic within an existing body of knowledge. Study can be deep and detailed, but it is often limited to the available resources and materials. While study may not contribute directly to the advancement of knowledge, it plays a crucial role in building a solid foundation of understanding.

Application and Output

Research is often driven by the desire to solve real-world problems or contribute to practical applications. The output of research can take various forms, including scientific papers, patents, policy recommendations, or technological advancements. Research findings are typically shared with the academic community and the public, aiming to advance knowledge and improve society.

Study, on the other hand, focuses more on personal development and learning. The application of study is often seen in academic settings, where individuals acquire knowledge to excel in their studies or careers. The output of study is usually reflected in improved understanding, enhanced critical thinking skills, and the ability to apply knowledge in practical situations.

Limitations and Challenges

Research faces several challenges, including limited resources, time constraints, ethical considerations, and the potential for bias. Conducting research requires careful planning, data collection, and analysis, which can be time-consuming and costly. Researchers must also navigate ethical guidelines and ensure the validity and reliability of their findings.

Study, on the other hand, may face challenges such as information overload, lack of motivation, or difficulty in finding reliable sources. It requires self-discipline, time management, and the ability to filter and prioritize information. Without proper guidance or structure, study can sometimes lead to superficial understanding or misconceptions.

In conclusion, research and study are both essential activities in the pursuit of knowledge and understanding. While research focuses on generating new knowledge and solving problems through a systematic approach, study aims to acquire and comprehend existing information. Research tends to be more formalized, rigorous, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge, while study is often more flexible, personalized, and focused on individual learning. Both research and study have their unique attributes and challenges, but together they form the foundation for intellectual growth and development.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

Research Methods

- Getting Started

- Literature Review Research

- Research Design

- Research Design By Discipline

- SAGE Research Methods

- Teaching with SAGE Research Methods

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is NOT a Literature Review?

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews vs. Systematic Reviews

- Systematic vs. Meta-Analysis

Literature Review is a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

Also, we can define a literature review as the collected body of scholarly works related to a topic:

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches.

- Indicates potential directions for future research.

All content in this section is from Literature Review Research from Old Dominion University

Keep in mind the following, a literature review is NOT:

Not an essay

Not an annotated bibliography in which you summarize each article that you have reviewed. A literature review goes beyond basic summarizing to focus on the critical analysis of the reviewed works and their relationship to your research question.

Not a research paper where you select resources to support one side of an issue versus another. A lit review should explain and consider all sides of an argument in order to avoid bias, and areas of agreement and disagreement should be highlighted.

A literature review serves several purposes. For example, it

- provides thorough knowledge of previous studies; introduces seminal works.

- helps focus one’s own research topic.

- identifies a conceptual framework for one’s own research questions or problems; indicates potential directions for future research.

- suggests previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, quantitative and qualitative strategies.

- identifies gaps in previous studies; identifies flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches; avoids replication of mistakes.

- helps the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research.

- suggests unexplored populations.

- determines whether past studies agree or disagree; identifies controversy in the literature.

- tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

As Kennedy (2007) notes*, it is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the original studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field. In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews.

Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are several approaches to how they can be done, depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study. Listed below are definitions of types of literature reviews:

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews.

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [content], but how they said it [method of analysis]. This approach provides a framework of understanding at different levels (i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches and data collection and analysis techniques), enables researchers to draw on a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection and data analysis, and helps highlight many ethical issues which we should be aware of and consider as we go through our study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?"

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to concretely examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review help establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

* Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147.

All content in this section is from The Literature Review created by Dr. Robert Larabee USC

Robinson, P. and Lowe, J. (2015), Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39: 103-103. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12393

What's in the name? The difference between a Systematic Review and a Literature Review, and why it matters . By Lynn Kysh from University of Southern California

Systematic review or meta-analysis?

A systematic review answers a defined research question by collecting and summarizing all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria.

A meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of these studies.

Systematic reviews, just like other research articles, can be of varying quality. They are a significant piece of work (the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York estimates that a team will take 9-24 months), and to be useful to other researchers and practitioners they should have:

- clearly stated objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies

- explicit, reproducible methodology

- a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies

- assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies (e.g. risk of bias)

- systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies

Not all systematic reviews contain meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included within a review. More information on meta-analyses can be found in Cochrane Handbook, Chapter 9 .

A meta-analysis goes beyond critique and integration and conducts secondary statistical analysis on the outcomes of similar studies. It is a systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

An advantage of a meta-analysis is the ability to be completely objective in evaluating research findings. Not all topics, however, have sufficient research evidence to allow a meta-analysis to be conducted. In that case, an integrative review is an appropriate strategy.

Some of the content in this section is from Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: step by step guide created by Kate McAllister.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Research Design >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 4:07 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.udel.edu/researchmethods

Literature Searching

Literature Searching vs. Literature Review

You may hear about conducting a literature search and literature review inter-changeably. In general, a literature search is the process of seeking out and identifying the existing literature related to a topic or question of interest, while a literature review is the organized synthesis of the information found in the existing literature.

In research, a literature search is typically the first step of a literature review. The search identifies relevant existing studies and articles, and the review is the end result of analyzing, synthesizing, and organizing the information found in the search.

When writing a research paper, the literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Show how your research addresses a knowledge gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

References/Additional Resources

Baker, J. D. (2016). T he Purpose, Process, and Methods of Writing a Literature Review . AORN Journal, 103(3), 265–269.

Patrick, L. J., & Munro, S. (2004). The Literature Review: Demystifying the Literature Search. The Diabetes Educator, 30(1), 30–38.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Major Steps in a Literature Search >>

- University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Reviewing Research: Literature Reviews, Scoping Reviews, Systematic Reviews

- Differentiating the Three Review Types

Reviewing Research: Literature Reviews, Scoping Reviews, Systematic Reviews: Differentiating the Three Review Types

- Framework, Protocol, and Writing Steps

- Working with Keywords/Subject Headings

- Citing Research

The Differences in the Review Types

Grant, M.J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. H ealth Information & Libraries Journal , 26: 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x The objective of this study is to provide descriptive insight into the most common types of reviews, with illustrative examples from health and health information domains.

- What Type of Review is Right for you (Cornell University)

Literature Reviews

Literature Review: it is a product and a process.

As a product , it is a carefully written examination, interpretation, evaluation, and synthesis of the published literature related to your topic. It focuses on what is known about your topic and what methodologies, models, theories, and concepts have been applied to it by others.

The process is what is involved in conducting a review of the literature.

- It is ongoing

- It is iterative (repetitive)

- It involves searching for and finding relevant literature.

- It includes keeping track of your references and preparing and formatting them for the bibliography of your thesis

- Literature Reviews (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) This handout will explain what literature reviews are and offer insights into the form and construction of literature reviews in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

Scoping Reviews

Scoping reviews are a " preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature . Aims to identify nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research)." Grant and Booth (2009).

Scoping reviews are not mapping reviews: Scoping reviews are more topic based and mapping reviews are more question based.

- examining emerging evidence when specific questions are unclear - clarify definitions and conceptual boundaries

- identify and map the available evidence

- a scoping review is done prior to a systematic review

- to summarize and disseminate research findings in the research literature

- identify gaps with the intention of resolution by future publications

- Scoping review timeframe and limitations (Touro College of Pharmacy

Systematic Reviews

Many evidence-based disciplines use ‘systematic reviews," this type of review is a specific methodology that aims to comprehensively identify all relevant studies on a specific topic, and to select appropriate studies based on explicit criteria . ( https://cebma.org/faq/what-is-a-systematic-review/ )

- clearly defined search criteria

- an explicit reproducible methodology

- a systematic search of the literature with the defined criteria met

- assesses validity of the findings - no risk of bias

- a comprehensive report on the findings, apparent transparency in the results

- Better evidence for a better world Browsable collection of systematic reviews

- Systematic Reviews in the Health Sciences by Molly Maloney Last Updated Apr 23, 2024 465 views this year

- Next: Framework, Protocol, and Writing Steps >>

Imperial College London Imperial College London

Latest news.

Voluntary corporate emissions targets not enough to create real climate action

Imperial and CNRS strengthen UK-France science with new partnerships

New AI startup accelerator led by Imperial opens for applications

- Educational Development Unit

- Teaching toolkit

- Educational research methods

- Before you start

Identifying literature

Before you start - Identifying literature

All educational research requires a thorough review of appropriate literature, by way of contextualising and justifying the intended study. Before you can begin conducting and writing your literature review, you need to ensure that you have systematically identified and sourced a sufficient range of relevant literature; and in doing so, maintain a sufficiently tight control over the boundaries of your search. You also need to ensure that you develop an efficient system for managing, retrieving and referencing the literature that you do use.

Savin-Baden & Howell Major (2013) provide a number of suggestions for how to proceed through each stage of the initial literature search, as summarised in the table below:

Savin-Baden, M. & Howell Major, C. (2013), Chapter 8 – “Literature Review”. In Savin-Baden, M. & Howell Major, C., Qualitative Research. The essential guide to theory and practice. Abingdon: Routledge (pp. 112-129).

Undergraduate Research Class - Module 3: Literature Review

- How to Search for KU Library Resources

Library Resources

- Engineering Standards

- Patent Research

- Institutional Resources

- How to Find Materials

- Area Libraries

- Literature Review

- Source Quality

- Summarizing Papers

- Research Questions & Hypothesis

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a comprehensive study and interpretation of literature that addresses a specific topic.

Literature reviews are generally conducted in one of two ways:

1) As a preliminary review before a larger study in order to critically evaluate the current literature and justify why further study and research is required.

2) As a project in itself that provides a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular discipline or area of research over a specified period of time.

Why conduct a literature review? They provide you with a handy guide to a particular topic. If you have limited time to conduct research, literature reviews can give you an overview or act as a stepping stone.

More: different types of literature reviews on how to conduct a literature review.

Literature Review Links

- PhD on Track: Types of Reviews Narrative & Systematic

- Purdue Owl: Literature Reviews

- Purdue OWL: Writing a Literature Review

How to Develop a Literature Review

How to develop a literature review from Academic Research Foundations: Quantitative by Rolin Moe

What is the Difference Between a Systematic Review and a Meta-analysis?

Dr. Singh discusses the difference between a systematic review and a meta-analysis.

Purpose of a Literature Review

Purpose of a literature review from Academic Research Foundations: Quantitative by Rolin Moe

- << Previous: Area Libraries

- Next: Source Quality >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 8:56 AM

- URL: https://libguides.kettering.edu/research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Korean J Anesthesiol

- v.71(2); 2018 Apr

Introduction to systematic review and meta-analysis

1 Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Inje University Seoul Paik Hospital, Seoul, Korea

2 Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Chung-Ang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses present results by combining and analyzing data from different studies conducted on similar research topics. In recent years, systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been actively performed in various fields including anesthesiology. These research methods are powerful tools that can overcome the difficulties in performing large-scale randomized controlled trials. However, the inclusion of studies with any biases or improperly assessed quality of evidence in systematic reviews and meta-analyses could yield misleading results. Therefore, various guidelines have been suggested for conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses to help standardize them and improve their quality. Nonetheless, accepting the conclusions of many studies without understanding the meta-analysis can be dangerous. Therefore, this article provides an easy introduction to clinicians on performing and understanding meta-analyses.

Introduction

A systematic review collects all possible studies related to a given topic and design, and reviews and analyzes their results [ 1 ]. During the systematic review process, the quality of studies is evaluated, and a statistical meta-analysis of the study results is conducted on the basis of their quality. A meta-analysis is a valid, objective, and scientific method of analyzing and combining different results. Usually, in order to obtain more reliable results, a meta-analysis is mainly conducted on randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which have a high level of evidence [ 2 ] ( Fig. 1 ). Since 1999, various papers have presented guidelines for reporting meta-analyses of RCTs. Following the Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses (QUORUM) statement [ 3 ], and the appearance of registers such as Cochrane Library’s Methodology Register, a large number of systematic literature reviews have been registered. In 2009, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [ 4 ] was published, and it greatly helped standardize and improve the quality of systematic reviews and meta-analyses [ 5 ].

Levels of evidence.

In anesthesiology, the importance of systematic reviews and meta-analyses has been highlighted, and they provide diagnostic and therapeutic value to various areas, including not only perioperative management but also intensive care and outpatient anesthesia [6–13]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses include various topics, such as comparing various treatments of postoperative nausea and vomiting [ 14 , 15 ], comparing general anesthesia and regional anesthesia [ 16 – 18 ], comparing airway maintenance devices [ 8 , 19 ], comparing various methods of postoperative pain control (e.g., patient-controlled analgesia pumps, nerve block, or analgesics) [ 20 – 23 ], comparing the precision of various monitoring instruments [ 7 ], and meta-analysis of dose-response in various drugs [ 12 ].

Thus, literature reviews and meta-analyses are being conducted in diverse medical fields, and the aim of highlighting their importance is to help better extract accurate, good quality data from the flood of data being produced. However, a lack of understanding about systematic reviews and meta-analyses can lead to incorrect outcomes being derived from the review and analysis processes. If readers indiscriminately accept the results of the many meta-analyses that are published, incorrect data may be obtained. Therefore, in this review, we aim to describe the contents and methods used in systematic reviews and meta-analyses in a way that is easy to understand for future authors and readers of systematic review and meta-analysis.

Study Planning

It is easy to confuse systematic reviews and meta-analyses. A systematic review is an objective, reproducible method to find answers to a certain research question, by collecting all available studies related to that question and reviewing and analyzing their results. A meta-analysis differs from a systematic review in that it uses statistical methods on estimates from two or more different studies to form a pooled estimate [ 1 ]. Following a systematic review, if it is not possible to form a pooled estimate, it can be published as is without progressing to a meta-analysis; however, if it is possible to form a pooled estimate from the extracted data, a meta-analysis can be attempted. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses usually proceed according to the flowchart presented in Fig. 2 . We explain each of the stages below.

Flowchart illustrating a systematic review.

Formulating research questions

A systematic review attempts to gather all available empirical research by using clearly defined, systematic methods to obtain answers to a specific question. A meta-analysis is the statistical process of analyzing and combining results from several similar studies. Here, the definition of the word “similar” is not made clear, but when selecting a topic for the meta-analysis, it is essential to ensure that the different studies present data that can be combined. If the studies contain data on the same topic that can be combined, a meta-analysis can even be performed using data from only two studies. However, study selection via a systematic review is a precondition for performing a meta-analysis, and it is important to clearly define the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes (PICO) parameters that are central to evidence-based research. In addition, selection of the research topic is based on logical evidence, and it is important to select a topic that is familiar to readers without clearly confirmed the evidence [ 24 ].

Protocols and registration

In systematic reviews, prior registration of a detailed research plan is very important. In order to make the research process transparent, primary/secondary outcomes and methods are set in advance, and in the event of changes to the method, other researchers and readers are informed when, how, and why. Many studies are registered with an organization like PROSPERO ( http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ ), and the registration number is recorded when reporting the study, in order to share the protocol at the time of planning.

Defining inclusion and exclusion criteria

Information is included on the study design, patient characteristics, publication status (published or unpublished), language used, and research period. If there is a discrepancy between the number of patients included in the study and the number of patients included in the analysis, this needs to be clearly explained while describing the patient characteristics, to avoid confusing the reader.

Literature search and study selection

In order to secure proper basis for evidence-based research, it is essential to perform a broad search that includes as many studies as possible that meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Typically, the three bibliographic databases Medline, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) are used. In domestic studies, the Korean databases KoreaMed, KMBASE, and RISS4U may be included. Effort is required to identify not only published studies but also abstracts, ongoing studies, and studies awaiting publication. Among the studies retrieved in the search, the researchers remove duplicate studies, select studies that meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria based on the abstracts, and then make the final selection of studies based on their full text. In order to maintain transparency and objectivity throughout this process, study selection is conducted independently by at least two investigators. When there is a inconsistency in opinions, intervention is required via debate or by a third reviewer. The methods for this process also need to be planned in advance. It is essential to ensure the reproducibility of the literature selection process [ 25 ].

Quality of evidence

However, well planned the systematic review or meta-analysis is, if the quality of evidence in the studies is low, the quality of the meta-analysis decreases and incorrect results can be obtained [ 26 ]. Even when using randomized studies with a high quality of evidence, evaluating the quality of evidence precisely helps determine the strength of recommendations in the meta-analysis. One method of evaluating the quality of evidence in non-randomized studies is the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, provided by the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute 1) . However, we are mostly focusing on meta-analyses that use randomized studies.

If the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) system ( http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/ ) is used, the quality of evidence is evaluated on the basis of the study limitations, inaccuracies, incompleteness of outcome data, indirectness of evidence, and risk of publication bias, and this is used to determine the strength of recommendations [ 27 ]. As shown in Table 1 , the study limitations are evaluated using the “risk of bias” method proposed by Cochrane 2) . This method classifies bias in randomized studies as “low,” “high,” or “unclear” on the basis of the presence or absence of six processes (random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding participants or investigators, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases) [ 28 ].

The Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool for Assessing the Risk of Bias [ 28 ]

Data extraction

Two different investigators extract data based on the objectives and form of the study; thereafter, the extracted data are reviewed. Since the size and format of each variable are different, the size and format of the outcomes are also different, and slight changes may be required when combining the data [ 29 ]. If there are differences in the size and format of the outcome variables that cause difficulties combining the data, such as the use of different evaluation instruments or different evaluation timepoints, the analysis may be limited to a systematic review. The investigators resolve differences of opinion by debate, and if they fail to reach a consensus, a third-reviewer is consulted.

Data Analysis

The aim of a meta-analysis is to derive a conclusion with increased power and accuracy than what could not be able to achieve in individual studies. Therefore, before analysis, it is crucial to evaluate the direction of effect, size of effect, homogeneity of effects among studies, and strength of evidence [ 30 ]. Thereafter, the data are reviewed qualitatively and quantitatively. If it is determined that the different research outcomes cannot be combined, all the results and characteristics of the individual studies are displayed in a table or in a descriptive form; this is referred to as a qualitative review. A meta-analysis is a quantitative review, in which the clinical effectiveness is evaluated by calculating the weighted pooled estimate for the interventions in at least two separate studies.

The pooled estimate is the outcome of the meta-analysis, and is typically explained using a forest plot ( Figs. 3 and and4). 4 ). The black squares in the forest plot are the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals in each study. The area of the squares represents the weight reflected in the meta-analysis. The black diamond represents the OR and 95% confidence interval calculated across all the included studies. The bold vertical line represents a lack of therapeutic effect (OR = 1); if the confidence interval includes OR = 1, it means no significant difference was found between the treatment and control groups.

Forest plot analyzed by two different models using the same data. (A) Fixed-effect model. (B) Random-effect model. The figure depicts individual trials as filled squares with the relative sample size and the solid line as the 95% confidence interval of the difference. The diamond shape indicates the pooled estimate and uncertainty for the combined effect. The vertical line indicates the treatment group shows no effect (OR = 1). Moreover, if the confidence interval includes 1, then the result shows no evidence of difference between the treatment and control groups.

Forest plot representing homogeneous data.

Dichotomous variables and continuous variables

In data analysis, outcome variables can be considered broadly in terms of dichotomous variables and continuous variables. When combining data from continuous variables, the mean difference (MD) and standardized mean difference (SMD) are used ( Table 2 ).

Summary of Meta-analysis Methods Available in RevMan [ 28 ]

The MD is the absolute difference in mean values between the groups, and the SMD is the mean difference between groups divided by the standard deviation. When results are presented in the same units, the MD can be used, but when results are presented in different units, the SMD should be used. When the MD is used, the combined units must be shown. A value of “0” for the MD or SMD indicates that the effects of the new treatment method and the existing treatment method are the same. A value lower than “0” means the new treatment method is less effective than the existing method, and a value greater than “0” means the new treatment is more effective than the existing method.

When combining data for dichotomous variables, the OR, risk ratio (RR), or risk difference (RD) can be used. The RR and RD can be used for RCTs, quasi-experimental studies, or cohort studies, and the OR can be used for other case-control studies or cross-sectional studies. However, because the OR is difficult to interpret, using the RR and RD, if possible, is recommended. If the outcome variable is a dichotomous variable, it can be presented as the number needed to treat (NNT), which is the minimum number of patients who need to be treated in the intervention group, compared to the control group, for a given event to occur in at least one patient. Based on Table 3 , in an RCT, if x is the probability of the event occurring in the control group and y is the probability of the event occurring in the intervention group, then x = c/(c + d), y = a/(a + b), and the absolute risk reduction (ARR) = x − y. NNT can be obtained as the reciprocal, 1/ARR.

Calculation of the Number Needed to Treat in the Dichotomous table

Fixed-effect models and random-effect models

In order to analyze effect size, two types of models can be used: a fixed-effect model or a random-effect model. A fixed-effect model assumes that the effect of treatment is the same, and that variation between results in different studies is due to random error. Thus, a fixed-effect model can be used when the studies are considered to have the same design and methodology, or when the variability in results within a study is small, and the variance is thought to be due to random error. Three common methods are used for weighted estimation in a fixed-effect model: 1) inverse variance-weighted estimation 3) , 2) Mantel-Haenszel estimation 4) , and 3) Peto estimation 5) .

A random-effect model assumes heterogeneity between the studies being combined, and these models are used when the studies are assumed different, even if a heterogeneity test does not show a significant result. Unlike a fixed-effect model, a random-effect model assumes that the size of the effect of treatment differs among studies. Thus, differences in variation among studies are thought to be due to not only random error but also between-study variability in results. Therefore, weight does not decrease greatly for studies with a small number of patients. Among methods for weighted estimation in a random-effect model, the DerSimonian and Laird method 6) is mostly used for dichotomous variables, as the simplest method, while inverse variance-weighted estimation is used for continuous variables, as with fixed-effect models. These four methods are all used in Review Manager software (The Cochrane Collaboration, UK), and are described in a study by Deeks et al. [ 31 ] ( Table 2 ). However, when the number of studies included in the analysis is less than 10, the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method 7) can better reduce the risk of type 1 error than does the DerSimonian and Laird method [ 32 ].

Fig. 3 shows the results of analyzing outcome data using a fixed-effect model (A) and a random-effect model (B). As shown in Fig. 3 , while the results from large studies are weighted more heavily in the fixed-effect model, studies are given relatively similar weights irrespective of study size in the random-effect model. Although identical data were being analyzed, as shown in Fig. 3 , the significant result in the fixed-effect model was no longer significant in the random-effect model. One representative example of the small study effect in a random-effect model is the meta-analysis by Li et al. [ 33 ]. In a large-scale study, intravenous injection of magnesium was unrelated to acute myocardial infarction, but in the random-effect model, which included numerous small studies, the small study effect resulted in an association being found between intravenous injection of magnesium and myocardial infarction. This small study effect can be controlled for by using a sensitivity analysis, which is performed to examine the contribution of each of the included studies to the final meta-analysis result. In particular, when heterogeneity is suspected in the study methods or results, by changing certain data or analytical methods, this method makes it possible to verify whether the changes affect the robustness of the results, and to examine the causes of such effects [ 34 ].

Heterogeneity

Homogeneity test is a method whether the degree of heterogeneity is greater than would be expected to occur naturally when the effect size calculated from several studies is higher than the sampling error. This makes it possible to test whether the effect size calculated from several studies is the same. Three types of homogeneity tests can be used: 1) forest plot, 2) Cochrane’s Q test (chi-squared), and 3) Higgins I 2 statistics. In the forest plot, as shown in Fig. 4 , greater overlap between the confidence intervals indicates greater homogeneity. For the Q statistic, when the P value of the chi-squared test, calculated from the forest plot in Fig. 4 , is less than 0.1, it is considered to show statistical heterogeneity and a random-effect can be used. Finally, I 2 can be used [ 35 ].

I 2 , calculated as shown above, returns a value between 0 and 100%. A value less than 25% is considered to show strong homogeneity, a value of 50% is average, and a value greater than 75% indicates strong heterogeneity.

Even when the data cannot be shown to be homogeneous, a fixed-effect model can be used, ignoring the heterogeneity, and all the study results can be presented individually, without combining them. However, in many cases, a random-effect model is applied, as described above, and a subgroup analysis or meta-regression analysis is performed to explain the heterogeneity. In a subgroup analysis, the data are divided into subgroups that are expected to be homogeneous, and these subgroups are analyzed. This needs to be planned in the predetermined protocol before starting the meta-analysis. A meta-regression analysis is similar to a normal regression analysis, except that the heterogeneity between studies is modeled. This process involves performing a regression analysis of the pooled estimate for covariance at the study level, and so it is usually not considered when the number of studies is less than 10. Here, univariate and multivariate regression analyses can both be considered.

Publication bias

Publication bias is the most common type of reporting bias in meta-analyses. This refers to the distortion of meta-analysis outcomes due to the higher likelihood of publication of statistically significant studies rather than non-significant studies. In order to test the presence or absence of publication bias, first, a funnel plot can be used ( Fig. 5 ). Studies are plotted on a scatter plot with effect size on the x-axis and precision or total sample size on the y-axis. If the points form an upside-down funnel shape, with a broad base that narrows towards the top of the plot, this indicates the absence of a publication bias ( Fig. 5A ) [ 29 , 36 ]. On the other hand, if the plot shows an asymmetric shape, with no points on one side of the graph, then publication bias can be suspected ( Fig. 5B ). Second, to test publication bias statistically, Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlation test 8) [ 37 ] or Egger’s test 9) [ 29 ] can be used. If publication bias is detected, the trim-and-fill method 10) can be used to correct the bias [ 38 ]. Fig. 6 displays results that show publication bias in Egger’s test, which has then been corrected using the trim-and-fill method using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (Biostat, USA).

Funnel plot showing the effect size on the x-axis and sample size on the y-axis as a scatter plot. (A) Funnel plot without publication bias. The individual plots are broader at the bottom and narrower at the top. (B) Funnel plot with publication bias. The individual plots are located asymmetrically.

Funnel plot adjusted using the trim-and-fill method. White circles: comparisons included. Black circles: inputted comparisons using the trim-and-fill method. White diamond: pooled observed log risk ratio. Black diamond: pooled inputted log risk ratio.

Result Presentation

When reporting the results of a systematic review or meta-analysis, the analytical content and methods should be described in detail. First, a flowchart is displayed with the literature search and selection process according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Second, a table is shown with the characteristics of the included studies. A table should also be included with information related to the quality of evidence, such as GRADE ( Table 4 ). Third, the results of data analysis are shown in a forest plot and funnel plot. Fourth, if the results use dichotomous data, the NNT values can be reported, as described above.

The GRADE Evidence Quality for Each Outcome

N: number of studies, ROB: risk of bias, PON: postoperative nausea, POV: postoperative vomiting, PONV: postoperative nausea and vomiting, CI: confidence interval, RR: risk ratio, AR: absolute risk.

When Review Manager software (The Cochrane Collaboration, UK) is used for the analysis, two types of P values are given. The first is the P value from the z-test, which tests the null hypothesis that the intervention has no effect. The second P value is from the chi-squared test, which tests the null hypothesis for a lack of heterogeneity. The statistical result for the intervention effect, which is generally considered the most important result in meta-analyses, is the z-test P value.

A common mistake when reporting results is, given a z-test P value greater than 0.05, to say there was “no statistical significance” or “no difference.” When evaluating statistical significance in a meta-analysis, a P value lower than 0.05 can be explained as “a significant difference in the effects of the two treatment methods.” However, the P value may appear non-significant whether or not there is a difference between the two treatment methods. In such a situation, it is better to announce “there was no strong evidence for an effect,” and to present the P value and confidence intervals. Another common mistake is to think that a smaller P value is indicative of a more significant effect. In meta-analyses of large-scale studies, the P value is more greatly affected by the number of studies and patients included, rather than by the significance of the results; therefore, care should be taken when interpreting the results of a meta-analysis.

When performing a systematic literature review or meta-analysis, if the quality of studies is not properly evaluated or if proper methodology is not strictly applied, the results can be biased and the outcomes can be incorrect. However, when systematic reviews and meta-analyses are properly implemented, they can yield powerful results that could usually only be achieved using large-scale RCTs, which are difficult to perform in individual studies. As our understanding of evidence-based medicine increases and its importance is better appreciated, the number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses will keep increasing. However, indiscriminate acceptance of the results of all these meta-analyses can be dangerous, and hence, we recommend that their results be received critically on the basis of a more accurate understanding.

1) http://www.ohri.ca .

2) http://methods.cochrane.org/bias/assessing-risk-bias-included-studies .

3) The inverse variance-weighted estimation method is useful if the number of studies is small with large sample sizes.

4) The Mantel-Haenszel estimation method is useful if the number of studies is large with small sample sizes.

5) The Peto estimation method is useful if the event rate is low or one of the two groups shows zero incidence.

6) The most popular and simplest statistical method used in Review Manager and Comprehensive Meta-analysis software.

7) Alternative random-effect model meta-analysis that has more adequate error rates than does the common DerSimonian and Laird method, especially when the number of studies is small. However, even with the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method, when there are less than five studies with very unequal sizes, extra caution is needed.

8) The Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation test uses the correlation between the ranks of effect sizes and the ranks of their variances [ 37 ].

9) The degree of funnel plot asymmetry as measured by the intercept from the regression of standard normal deviates against precision [ 29 ].

10) If there are more small studies on one side, we expect the suppression of studies on the other side. Trimming yields the adjusted effect size and reduces the variance of the effects by adding the original studies back into the analysis as a mirror image of each study.

Understanding Nursing Research

- Primary Research

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research

- Experimental Design

- Is it a Nursing journal?

- Is it Written by a Nurse?

Secondary Research and Systematic Reviews

Comparative table.

- Quality Improvement Plans

Secondary Research is when researchers collect lots of research that has already been published on a certain subject. They conduct searches in databases, go through lots of primary research articles, and analyze the findings in those pieces of primary research. The goal of secondary research is to pull together lots of diverse primary research (like studies and trials), with the end goal of making a generalized statement. Primary research can only make statements about the specific context in which their research was conducted (for example, this specific intervention worked in this hospital with these participants), but secondary research can make broader statements because it compiled lots of primary research together. So rather than saying, "this specific intervention worked at this specific hospital with these specific participants, a piece of secondary research can say, "This intervention works at hospitals that serve this population."

Systematic Reviews are a kind of secondary research. The creators of systematic reviews are very intentional about their inclusion/exclusion criteria, or which articles they'll include in their review and the goal is to make a generalized statement so other researchers can build upon the practices or interventions they recommend. Use the chart below to understand the differences between a systematic review and a literature review.

Check out the video below to watch the Nursing and Health Sciences librarian describe the differences between primary and secondary research.

- "Literature Reviews and Systematic Reviews: What Is the Difference?" This article explains in depth the differences between Literature Reviews and Systematic Reviews. It is from the journal RADIOLOGIC TECHNOLOGY, Nov/Dec 2013, v. 85, #2. It is one to which Bell Library subscribes and meets copyright clearance requirements through our subscription to CCC.

- << Previous: Is it Written by a Nurse?

- Next: Permalinks >>

- Last Updated: Feb 6, 2024 9:34 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.tamucc.edu/nursingresearch

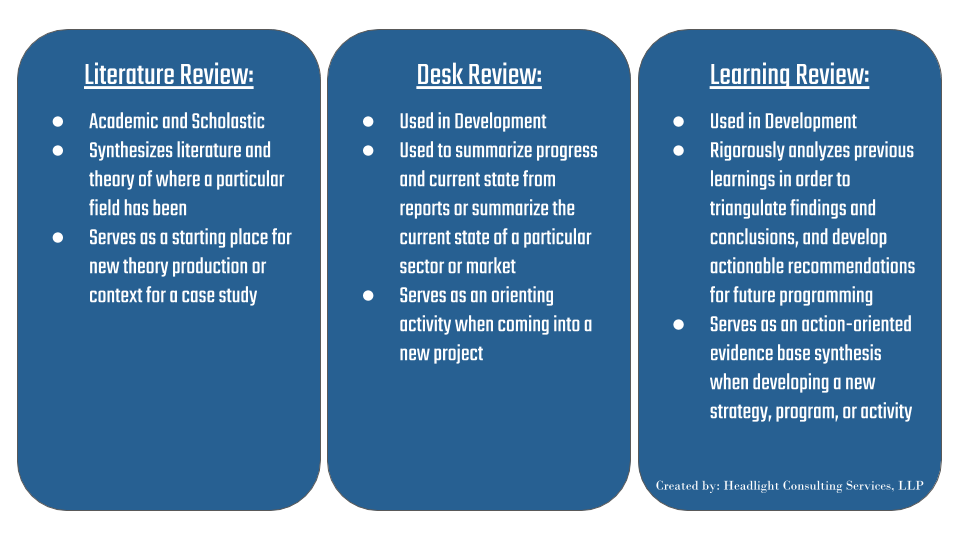

A Quick Overview: Differences Among Desk, Literature, and Learning Reviews

November 12, 2020

By: Chelsie Kuhn, MEL Associate, Headlight Consulting Services, LLP

This is the first post in a series of two about Learning Reviews .

In order to chart the wisest path forward, we need to understand where we have been. Reflecting on past learning can ensure more effective and efficient efforts in the future, regardless of discipline or field. But different information needs require different tools. Literature, Desk, and Learning Reviews are three ways to integrate evidence into decision-making and design processes. Each tool uses varying degrees of information and rigor, and each is best suited for different applications, as described in the visual below.

A Literature Review traditionally focuses on academic journal articles and published books, giving readers a theoretical or case-based frame of reference. A Literature Review may be appropriate for researchers looking to set up an experiment or randomized control trial in a location or those looking at theoretical development over time. This kind of review is all about synthesis of what we know research-wise up to the current point, and what potential gaps exist yet to be filled.

Another type of review widely known is a Desk Review, which serves to provide readers with an introduction into a project’s context and priorities, but often not the past learnings or in-depth challenges needed to inform strategy development. A Desk Review can also serve as an entry point to understanding a particular market or an effective way to organize and summarize disparate types of information. Doing a Desk Review might be appropriate to bring a new team member up to speed on projects or learn about the current state and environment concerning a particular type of intervention.

While Literature and Desk Reviews may be more commonly known, one of the offerings that Headlight specializes in is a Learning Review. A Learning Review is a way to systematically look at past assessments, evaluations, reports, and any other learning documentation in order to inform recommendations and strategy, program, or activity design efforts. Unlike Desk Reviews, Learning Reviews focus on coding and analyzing data instead of summarizing it. With layers of triangulation and secondary analysis built into the process, we can confidently draw findings and conclusions knowing that the foundation of the process is built with rigor. Recommendations stemming from these findings and conclusions serve as the best use of an existing evidence base in designing or revisiting strategies, programs, and activities. Each of these three tools are useful at different points, but as we see more and more emphasis placed on learning and adaptive management, Learning Reviews offer a more rigorous and application focused use of available evidence.

As a synthesis of past evaluations and assessments, Learning Reviews should also be used to feed into new MEL or CLA plans. Having extra information on what has worked in the past, what information was useful, and where more-nuanced information would be beneficial enables us to set better targets and understand potential barriers to measurement. Recommendations may even point to specific indicators to consider or CLA actions to integrate into programming moving forward. Learning Reviews can also be used to appropriately scope and identify future evaluative efforts that will evolve the evidence base.

In the next post in the series, we will expand further on Learning Reviews as a process and walk readers step-by-step through how to conduct one. If you need help implementing any of these above tools, but in particular a Learning Review, Headlight would love to support you! We have the breadth and depth of expertise, experience, and toolbox to tailor-meet your needs. For more information about our services please email [email protected] . Headlight Consulting Services, LLP is a certified women-owned small business and therefore eligible for sole source procurements. We can be found on the Dynamic Small Business Search or on SAM.gov via our name or DUNS number (081332548).

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

no comments found.

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address

Recent Posts

- Evaluation Rigor in Action — The Qualitative Comparative Analysis Methods Memo

- 2023 in Review: Headlight’s Values in Action

- The Small Business Chrysalis: Reflections on Becoming a Prime

- Choose Your Own Adventure: Options for Adapting the Collaborating, Learning & Adapting (CLA) Maturity Self-assessment Process

- Evaluation for Learning and Adaptive Management: Connecting the Dots between Developmental Evaluation and CLA

Recent Comments

- Maxine Secskas on What is a USAID Performance Management Plan?

- Anonymous on What is a USAID Performance Management Plan?

- Getasew Atnafu on The Small Business Chrysalis: Reflections on Becoming a Prime

- Anonymous on The Small Business Chrysalis: Reflections on Becoming a Prime

- Anonymous on Why Embeddedness Is Crucial For Use-Focused Developmental Evaluation Support

- February 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- January 2023

- November 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- December 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- Uncategorized

- Opportunities

- About WordPress

- Get Involved

- WordPress.org

- Documentation

- Learn WordPress

SRJ Student Resource

Literature review vs research articles: how are they different.

Unlock the secrets of academic writing with our guide to the key differences between a literature review and a research paper! 📚 Dive into the world of scholarly exploration as we break down how a literature review illuminates existing knowledge, identifies gaps, and sets the stage for further research. 🌐 Then, gear up for the adventure of crafting a research paper, where you become the explorer, presenting your unique insights and discoveries through independent research. 🚀 Join us on this academic journey and discover the art of synthesizing existing wisdom and creating your own scholarly masterpiece! 🎓✨

We are always accepting submissions! Submit work within SRJ’s scope anytime while you’re a graduate student.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

The act of commenting on this site is an opt-in action and San Jose State University may not be held liable for the information provided by participating in the activity.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Your go-to destination for graduate student research support

Home » Education » Difference Between Literature Review and Systematic Review

Difference Between Literature Review and Systematic Review

Main difference – literature review vs systematic review.

Literature review and systematic review are two scholarly texts that help to introduce new knowledge to various fields. A literature review, which reviews the existing research and information on a selected study area, is a crucial element of a research study. A systematic review is also a type of a literature review. The main difference between literature review and systematic review is their focus on the research question ; a systematic review is focused on a specific research question whereas a literature review is not.

This article highlights,

1. What is a Literature Review? – Definition, Features, Characteristics

2. What is a Systematic Review? – Definition, Features, Characteristics

What is a Literature Review

A literature review is an indispensable element of a research study. This is where the researcher shows his knowledge on the subject area he or she is researching on. A literature review is a discussion on the already existing material in the subject area. Thus, this will require a collection of published (in print or online) work concerning the selected research area. In simple terms, a literature is a review of the literature in the related subject area.

A good literature review is a critical discussion, displaying the writer’s knowledge on relevant theories and approaches and awareness of contrasting arguments. A literature review should have the following features (Caulley, 1992)

- Compare and contrast different researchers’ views

- Identify areas in which researchers are in disagreement

- Group researchers who have similar conclusions

- Criticize the methodology

- Highlight exemplary studies

- Highlight gaps in research

- Indicate the connection between your study and previous studies

- Indicate how your study will contribute to the literature in general

- Conclude by summarizing what the literature indicates

The structure of a literature review is similar to that of an article or essay, unlike an annotated bibliography . The information that is collected is integrated into paragraphs based on their relevance. Literature reviews help researchers to evaluate the existing literature, to identify a gap in the research area, to place their study in the existing research and identify future research.

What is a Systematic Review

A systematic review is a type of systematic review that is focused on a particular research question . The main purpose of this type of research is to identify, review, and summarize the best available research on a specific research question. Systematic reviews are used mainly because the review of existing studies is often more convenient than conducting a new study. These are mostly used in the health and medical field, but they are not rare in fields such as social sciences and environmental science. Given below are the main stages of a systematic review:

- Defining the research question and identifying an objective method

- Searching for relevant data that from existing research studies that meet certain criteria (research studies must be reliable and valid).

- Extracting data from the selected studies (data such as the participants, methods, outcomes, etc.

- Assessing the quality of information

- Analyzing and combining all the data which would give an overall result.

Literature Review is a critical evaluation of the existing published work in a selected research area.

Systematic Review is a type of literature review that is focused on a particular research question.

Literature Review aims to review the existing literature, identify the research gap, place the research study in relation to other studies, to evaluate promising research methods, and to suggest further research.

Systematic Review aims to identify, review, and summarize the best available research on a specific research question.

Research Question

In Literature Review, a r esearch question is formed after writing the literature review and identifying the research gap.

In Systematic Review, a research question is formed at the beginning of the systematic review.

Research Study

Literature Review is an essential component of a research study and is done at the beginning of the study.

Systematic Review is not followed by a separate research study.

Caulley, D. N. “Writing a critical review of the literature.” La Trobe University: Bundoora (1992).

“Animated Storyboard: What Are Systematic Reviews?” . cccrg.cochrane.org . Cochrane Consumers and Communication . Retrieved 1 June 2016.

Image Courtesy: Pixabay

About the Author: Hasa

Hasanthi is a seasoned content writer and editor with over 8 years of experience. Armed with a BA degree in English and a knack for digital marketing, she explores her passions for literature, history, culture, and food through her engaging and informative writing.

You May Also Like These

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Informative Website For Everyone

What is the difference of literature and studies?

Table of Contents

- 1 What is the difference of literature and studies?

- 2 How do you write related literature and related studies?

- 3 What is the example of literature?

- 4 What is RRL and example?

- 5 What is the meaning of related studies?

- 6 Why is a review of related literature important?

- 7 How is the literature related to the present study?

Studies are where actual experiments are performed and/or data are collected and analyzed. Literature is a more general term that includes not only published studies, but also other things like abstract theoretical discussions, opinions, policy statements by government or other agencies, etc.

What is related literature and studies?

Related literature and studies help the researcher understand his topic better because it may clarify vague points about his problem. It also guides the researcher in making comparisons between his findings with the findings of other similar studies.

How do you write related literature and related studies?

Write a Literature Review

- Narrow your topic and select papers accordingly.

- Search for literature.

- Read the selected articles thoroughly and evaluate them.

- Organize the selected papers by looking for patterns and by developing subtopics.

- Develop a thesis or purpose statement.

- Write the paper.

- Review your work.

What are related literature and studies important in research?

It establishes the authors’ in-depth understanding and knowledge of their field subject. It gives the background of the research. Portrays the scientific manuscript plan of examining the research result.

What is the example of literature?

Literature is defined as books and other written works, especially those considered to have creative or artistic merit or lasting value. Books written by Charles Dickens are an example of literature. Books written on a scientific subject are examples of scientific literature.

Is article a literature or study?

The Literature refers to the collection of scholarly writings on a topic. This includes peer-reviewed articles, books, dissertations and conference papers. When reviewing the literature, be sure to include major works as well as studies that respond to major works.

What is RRL and example?

A review of related literature (RRL) is a detailed review of existing literature related to the topic of a thesis or dissertation. In an RRL, you talk about knowledge and findings from existing literature relevant to your topic.

How are good related literature and studies characterize?

Its a process of gathering relevant information on a particular subject . A good literature review shows signs of synthesis and understanding of the topic. There should be strong evidence of analytical thinking shown through the connections you make between the literature being reviewed.

What is the meaning of related studies?

Usually, related studies is about reviewing or studying existing works carried out in your project/research field. D candidate’s related works is important constraint since pave path to entire research process. Related studies can be taken from journals, magazines, website links, government reports and other source.

Do you paraphrase RRL?

To prevent plagiarism, you must not only write your literature review properly with the suitable style manual such as APA or Harvard, but also properly manage direct quotations and paraphrasing. Paraphrasing is not acceptable if you simply copy and paste original text of literature review and alter them slightly.

Why is a review of related literature important?

What’s the difference between related literature and thesis?

How is the literature related to the present study?

Which is an example of a related literature?

Privacy Overview

- How to Contact Us

- Library & Collections

- Business School

- Things To Do

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/central-news-and-events-images/83431-1920X290.jpg)

International Dance Day: Looking at literature’s relationship to dance in 19th and 20th century modernism

- Durham news

- English Literature

.png)

On International Dance Day (Monday, 29 April) Dr Megan Girdwood from our Department of English explains how her research concentrates on late nineteenth and twentieth-century modernism, with a particular focus on literature’s relationship to performance, dance and the human body.

What is your research mainly about?

I am interested in how writing became entangled with art forms centred on the body during this period, when we begin to see experiments in new kinds of literature and similar ‘revolutions’ in the world of dance.

I am intrigued by unexpected crossovers between writers and performers: how did a non-textual art form like dance shape literary techniques and aesthetics at the turn of the century? Can the movements of the body be ‘read’ alongside the movements of language?

Where does your interest in researching dance within late 19 th and 20 th century literature come from?

My first book traced representations of the biblical figure of Salome and her ‘dance of the seven veils’ across literature, dance, and silent film from the early 1890s to the mid-twentieth century.

Researching the rich and varied history of this figure, made famous in Oscar Wilde’s play Salomé (1893/4), made me aware of the widespread fascination with dance during this period, which saw performers like Loïe Fuller, Isadora Duncan, and Vaslav Nijinsky developing new vocabularies of movement in modern dance and ballet.

Writers including Arthur Symons, W.B. Yeats, Virginia Woolf, Mina Loy, and Emily Holmes Coleman expressed a profound interest in dance and saw it as analogous to their own modernist treatment of language and narrative form.

What is the wider significance of the relationship between literature and dance during this period?

The way writers responded to dance can tell us about wider shifts in ways of thinking about the human body: as a tool for personal expression, an active creative and cultural medium, and as a biomechanical entity.

From the rigid choreography of the Tiller Girls to the freer movements of the Lindy Hop, dance made visible wider concerns with gender roles, sexual and racial expression, industrialisation and ‘nature,’ and the tension between modernisation and older cultural forms.

‘Movement,’ broadly conceived, was a keyword of modernity: ways of moving and reading movement crossed the boundaries between so-called ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ arts and presented the body as a site of profound meaning.

Find out more:

- Read about the work of Dr Megan Girdwood

- Find out more about International Dance Day

Ranked 3rd in the UK in the Guardian University Guide 2024 and 29th in the 2024 QS World University Rankings by subject, our English Department employs teachers including award-winning poets and a recently named New Generation Thinker.

Our broad subject range is made possible by our large and thriving community of more than 900 students, researchers and academics, with a busy programme of events including lectures, seminars, reading and discussion groups.

Feeling inspired? Visit our English Studies webpages for more information on our undergraduate and postgraduate programmes.

Durham University is a top 100 world university. In the QS World University Rankings 2024, we were ranked 78th globally.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

New Study Bolsters Idea of Athletic Differences Between Men and Trans Women

Research financed by the International Olympic Committee introduced new data to the unsettled and fractious debate about bans on transgender athletes.

By Jeré Longman

A new study financed by the International Olympic Committee found that transgender female athletes showed greater handgrip strength — an indicator of overall muscle strength — but lower jumping ability, lung function and relative cardiovascular fitness compared with women whose gender was assigned female at birth.

That data, which also compared trans women with men, contradicted a broad claim often made by proponents of rules that bar transgender women from competing in women’s sports. It also led the study’s authors to caution against a rush to expand such policies, which already bar transgender athletes from a handful of Olympic sports.

The study’s most important finding, according to one of its authors, Yannis Pitsiladis, a member of the I.O.C.’s medical and scientific commission, was that, given physiological differences, “Trans women are not biological men.”

Alternately praised and criticized, the study added an intriguing data set to an unsettled and often politicized debate that may only grow louder with the Paris Olympics and a U.S. presidential election approaching.

The authors cautioned against the presumption of immutable and disproportionate advantages for transgender female athletes who compete in women’s sports, and they advised against “precautionary bans and sport eligibility exclusions” that were not based on sport-specific research.

Outright bans, though, continue to proliferate. Twenty-five U.S. states now have laws or regulations barring transgender athletes from competing in girls and women’s sports, according to the Movement Advancement Project , a nonprofit that focuses on gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender parity. And the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics , the governing body for smaller colleges, this month barred transgender athletes from competing in women’s sports unless their sex was assigned female at birth and they had not undergone hormone therapy.

Two of the most visible sports at this summer’s Paris Games — swimming and track and field — along with cycling have effectively barred transgender female athletes who went through puberty as males. Rugby has instituted a total ban on trans female athletes, citing safety concerns, and those permitted to participate in other sports often face stricter requirements in suppressing their levels of testosterone.

The International Olympic Committee has left eligibility rules for transgender female athletes up to the global federations that govern individual sports. And while the Olympic committee provided financing for the study — as it does on a variety of topics through a research fund — Olympic officials had no input or influence on the results, Dr. Pitsiladis said.

In general, the argument for the bans has been that profound advantages gained from testosterone-fueled male puberty — broader shoulders, bigger hands, longer torsos, and greater muscle mass, strength, bone density and heart and lung capacity — give transgender female athletes an inequitable and largely irreversible competitive edge.

The new laboratory-based, peer-reviewed and I.O.C.-funded study at the University of Brighton, published this month in the British Journal of Sports Medicine , tested 19 cisgender men (those whose gender identity matches the sex they were assigned at birth) and 12 trans men, along with 23 trans women and 21 cisgender women.

All of the participants played competitive sports or underwent physical training at least three times a week. And all of the trans female athletes had undergone at least a year of treatment suppressing their testosterone levels and taking estrogen supplementation, the researchers said. None of the participants were athletes competing at the national or international level.

The study found that transgender female participants showed greater handgrip strength than cisgender female participants but lower lung function and relative VO2 max, the amount of oxygen used when exercising. Transgender female athletes also scored below cisgender women and men on a jumping test that measured lower-body power.