Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as you go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

Whether you’re exploring a new research field or finding new angles to develop an existing topic, sifting through hundreds of papers can take more time than you have to spare. But what if you could find science-backed insights with verified citations in seconds? That’s the power of Paperpal’s new Research feature!

How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Paperpal, an AI writing assistant, integrates powerful academic search capabilities within its writing platform. With the Research feature, you get 100% factual insights, with citations backed by 250M+ verified research articles, directly within your writing interface with the option to save relevant references in your Citation Library. By eliminating the need to switch tabs to find answers to all your research questions, Paperpal saves time and helps you stay focused on your writing.

Here’s how to use the Research feature:

- Ask a question: Get started with a new document on paperpal.com. Click on the “Research” feature and type your question in plain English. Paperpal will scour over 250 million research articles, including conference papers and preprints, to provide you with accurate insights and citations.

- Review and Save: Paperpal summarizes the information, while citing sources and listing relevant reads. You can quickly scan the results to identify relevant references and save these directly to your built-in citations library for later access.

- Cite with Confidence: Paperpal makes it easy to incorporate relevant citations and references into your writing, ensuring your arguments are well-supported by credible sources. This translates to a polished, well-researched literature review.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a good literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses. By combining effortless research with an easy citation process, Paperpal Research streamlines the literature review process and empowers you to write faster and with more confidence. Try Paperpal Research now and see for yourself.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

- How to Use Paperpal to Generate Emails & Cover Letters?

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, how to write a high-quality conference paper, how paperpal’s research feature helps you develop and..., how paperpal is enhancing academic productivity and accelerating..., how to write a successful book chapter for..., academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., 4 ways paperpal encourages responsible writing with ai, what are scholarly sources and where can you..., how to write a hypothesis types and examples , measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, what is academic writing: tips for students.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Writing a Literature Review

Hundreds of original investigation research articles on health science topics are published each year. It is becoming harder and harder to keep on top of all new findings in a topic area and – more importantly – to work out how they all fit together to determine our current understanding of a topic. This is where literature reviews come in.

In this chapter, we explain what a literature review is and outline the stages involved in writing one. We also provide practical tips on how to communicate the results of a review of current literature on a topic in the format of a literature review.

7.1 What is a literature review?

Literature reviews provide a synthesis and evaluation of the existing literature on a particular topic with the aim of gaining a new, deeper understanding of the topic.

Published literature reviews are typically written by scientists who are experts in that particular area of science. Usually, they will be widely published as authors of their own original work, making them highly qualified to author a literature review.

However, literature reviews are still subject to peer review before being published. Literature reviews provide an important bridge between the expert scientific community and many other communities, such as science journalists, teachers, and medical and allied health professionals. When the most up-to-date knowledge reaches such audiences, it is more likely that this information will find its way to the general public. When this happens, – the ultimate good of science can be realised.

A literature review is structured differently from an original research article. It is developed based on themes, rather than stages of the scientific method.

In the article Ten simple rules for writing a literature review , Marco Pautasso explains the importance of literature reviews:

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications. For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively. Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests. Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read. For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way (Pautasso, 2013, para. 1).

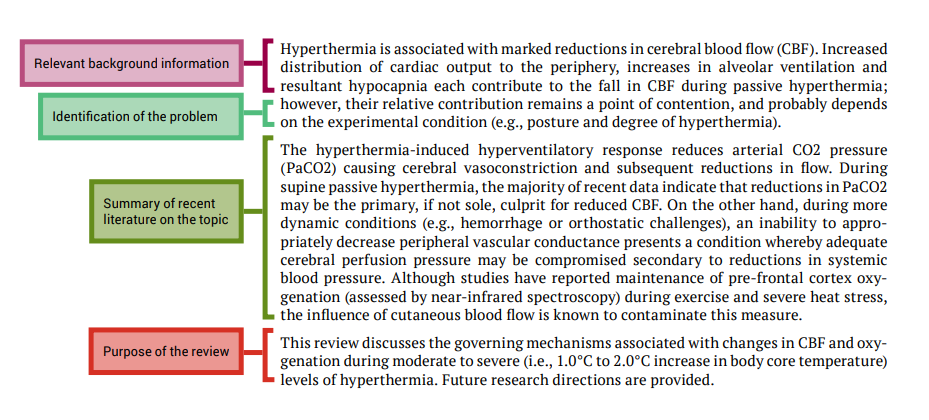

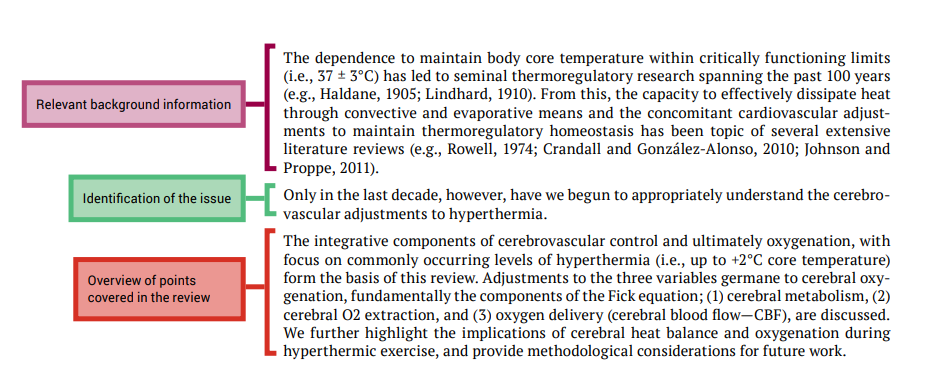

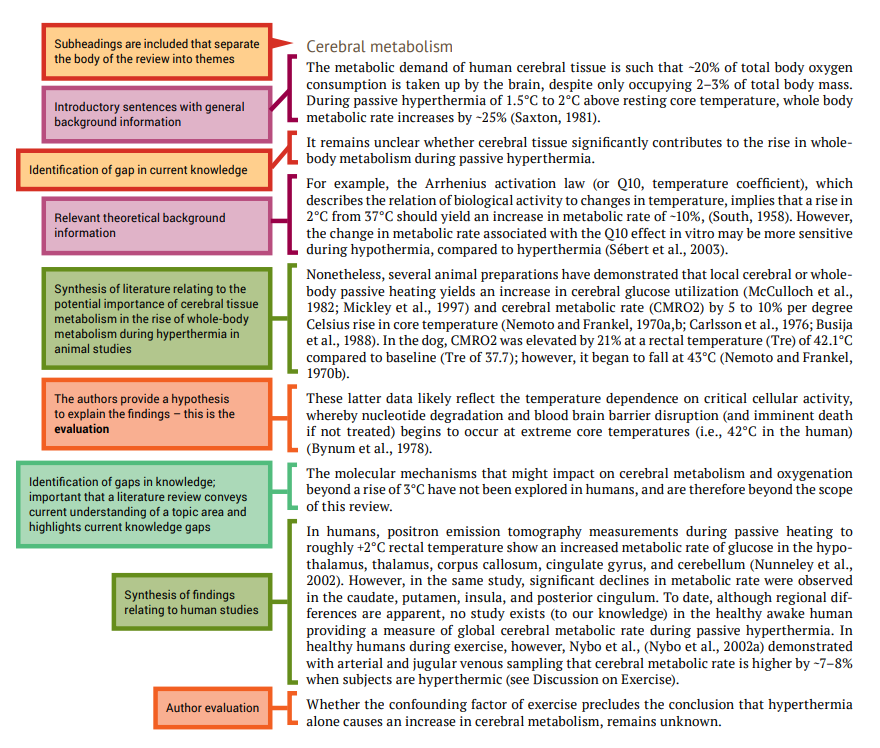

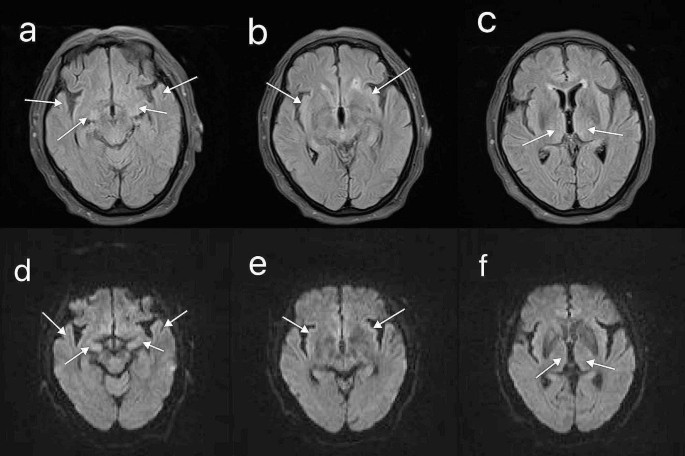

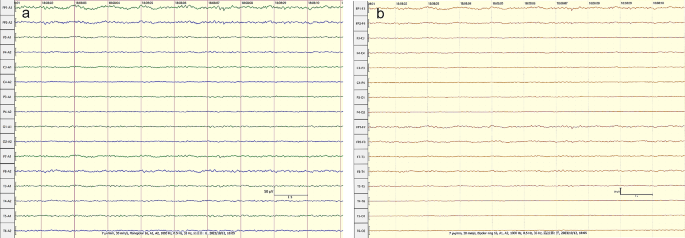

An example of a literature review is shown in Figure 7.1.

Video 7.1: What is a literature review? [2 mins, 11 secs]

Watch this video created by Steely Library at Northern Kentucky Library called ‘ What is a literature review? Note: Closed captions are available by clicking on the CC button below.

Examples of published literature reviews

- Strength training alone, exercise therapy alone, and exercise therapy with passive manual mobilisation each reduce pain and disability in people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review

- Traveler’s diarrhea: a clinical review

- Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: literature review and research recommendations for global mental health epidemiology

7.2 Steps of writing a literature review

Writing a literature review is a very challenging task. Figure 7.2 summarises the steps of writing a literature review. Depending on why you are writing your literature review, you may be given a topic area, or may choose a topic that particularly interests you or is related to a research project that you wish to undertake.

Chapter 6 provides instructions on finding scientific literature that would form the basis for your literature review.

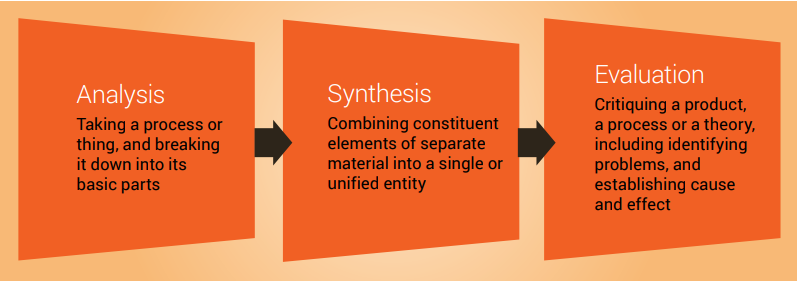

Once you have your topic and have accessed the literature, the next stages (analysis, synthesis and evaluation) are challenging. Next, we look at these important cognitive skills student scientists will need to develop and employ to successfully write a literature review, and provide some guidance for navigating these stages.

Analysis, synthesis and evaluation

Analysis, synthesis and evaluation are three essential skills required by scientists and you will need to develop these skills if you are to write a good literature review ( Figure 7.3 ). These important cognitive skills are discussed in more detail in Chapter 9.

The first step in writing a literature review is to analyse the original investigation research papers that you have gathered related to your topic.

Analysis requires examining the papers methodically and in detail, so you can understand and interpret aspects of the study described in each research article.

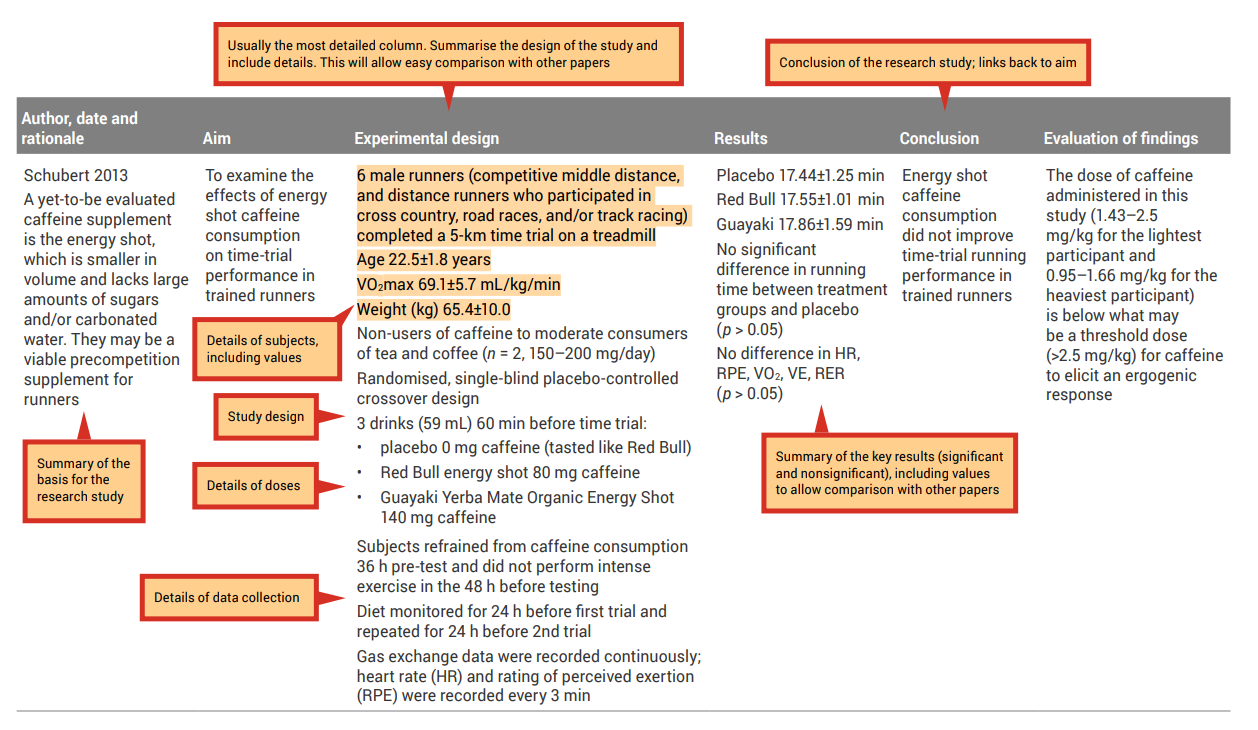

An analysis grid is a simple tool you can use to help with the careful examination and breakdown of each paper. This tool will allow you to create a concise summary of each research paper; see Table 7.1 for an example of an analysis grid. When filling in the grid, the aim is to draw out key aspects of each research paper. Use a different row for each paper, and a different column for each aspect of the paper ( Tables 7.2 and 7.3 show how completed analysis grid may look).

Before completing your own grid, look at these examples and note the types of information that have been included, as well as the level of detail. Completing an analysis grid with a sufficient level of detail will help you to complete the synthesis and evaluation stages effectively. This grid will allow you to more easily observe similarities and differences across the findings of the research papers and to identify possible explanations (e.g., differences in methodologies employed) for observed differences between the findings of different research papers.

Table 7.1: Example of an analysis grid

Table 7.3: Sample filled-in analysis grid for research article by Ping and colleagues

Source: Ping, WC, Keong, CC & Bandyopadhyay, A 2010, ‘Effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in a hot and humid climate’, Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 132, pp. 36–41. Used under a CC-BY-NC-SA licence.

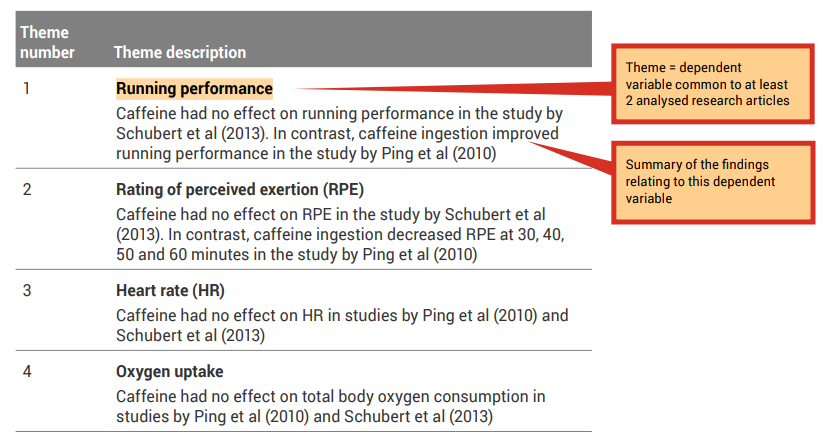

Step two of writing a literature review is synthesis.

Synthesis describes combining separate components or elements to form a connected whole.

You will use the results of your analysis to find themes to build your literature review around. Each of the themes identified will become a subheading within the body of your literature review.

A good place to start when identifying themes is with the dependent variables (results/findings) that were investigated in the research studies.

Because all of the research articles you are incorporating into your literature review are related to your topic, it is likely that they have similar study designs and have measured similar dependent variables. Review the ‘Results’ column of your analysis grid. You may like to collate the common themes in a synthesis grid (see, for example Table 7.4 ).

Step three of writing a literature review is evaluation, which can only be done after carefully analysing your research papers and synthesising the common themes (findings).

During the evaluation stage, you are making judgements on the themes presented in the research articles that you have read. This includes providing physiological explanations for the findings. It may be useful to refer to the discussion section of published original investigation research papers, or another literature review, where the authors may mention tested or hypothetical physiological mechanisms that may explain their findings.

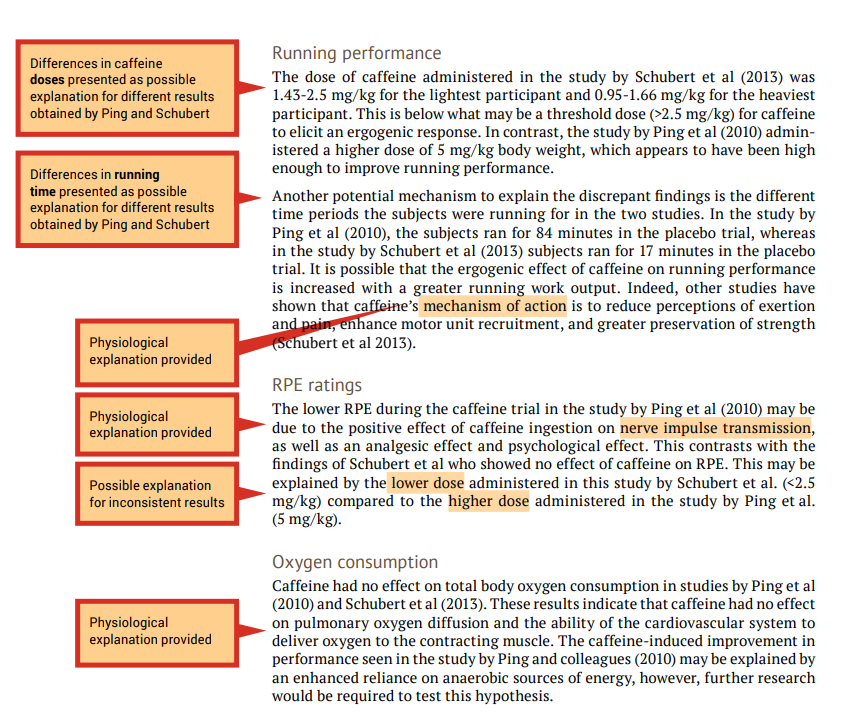

When the findings of the investigations related to a particular theme are inconsistent (e.g., one study shows that caffeine effects performance and another study shows that caffeine had no effect on performance) you should attempt to provide explanations of why the results differ, including physiological explanations. A good place to start is by comparing the methodologies to determine if there are any differences that may explain the differences in the findings (see the ‘Experimental design’ column of your analysis grid). An example of evaluation is shown in the examples that follow in this section, under ‘Running performance’ and ‘RPE ratings’.

When the findings of the papers related to a particular theme are consistent (e.g., caffeine had no effect on oxygen uptake in both studies) an evaluation should include an explanation of why the results are similar. Once again, include physiological explanations. It is still a good idea to compare methodologies as a background to the evaluation. An example of evaluation is shown in the following under ‘Oxygen consumption’.

7.3 Writing your literature review

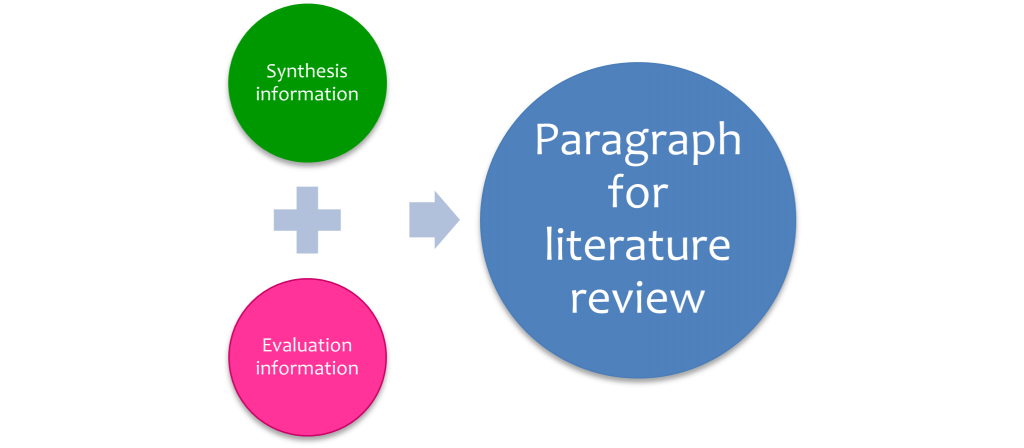

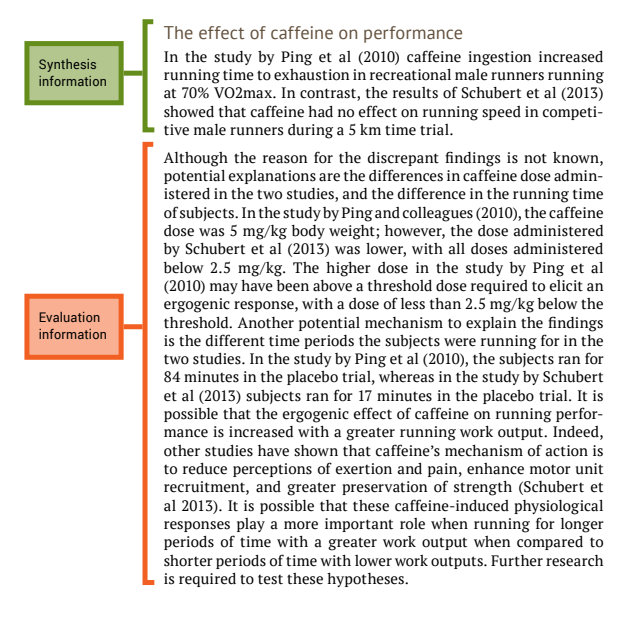

Once you have completed the analysis, and synthesis grids and written your evaluation of the research papers , you can combine synthesis and evaluation information to create a paragraph for a literature review ( Figure 7.4 ).

The following paragraphs are an example of combining the outcome of the synthesis and evaluation stages to produce a paragraph for a literature review.

Note that this is an example using only two papers – most literature reviews would be presenting information on many more papers than this ( (e.g., 106 papers in the review article by Bain and colleagues discussed later in this chapter). However, the same principle applies regardless of the number of papers reviewed.

The next part of this chapter looks at the each section of a literature review and explains how to write them by referring to a review article that was published in Frontiers in Physiology and shown in Figure 7.1. Each section from the published article is annotated to highlight important features of the format of the review article, and identifies the synthesis and evaluation information.

In the examination of each review article section we will point out examples of how the authors have presented certain information and where they display application of important cognitive processes; we will use the colour code shown below:

This should be one paragraph that accurately reflects the contents of the review article.

Introduction

The introduction should establish the context and importance of the review

Body of literature review

The reference section provides a list of the references that you cited in the body of your review article. The format will depend on the journal of publication as each journal has their own specific referencing format.

It is important to accurately cite references in research papers to acknowledge your sources and ensure credit is appropriately given to authors of work you have referred to. An accurate and comprehensive reference list also shows your readers that you are well-read in your topic area and are aware of the key papers that provide the context to your research.

It is important to keep track of your resources and to reference them consistently in the format required by the publication in which your work will appear. Most scientists will use reference management software to store details of all of the journal articles (and other sources) they use while writing their review article. This software also automates the process of adding in-text references and creating a reference list. In the review article by Bain et al. (2014) used as an example in this chapter, the reference list contains 106 items, so you can imagine how much help referencing software would be. Chapter 5 shows you how to use EndNote, one example of reference management software.

Click the drop down below to review the terms learned from this chapter.

Copyright note:

- The quotation from Pautasso, M 2013, ‘Ten simple rules for writing a literature review’, PLoS Computational Biology is use under a CC-BY licence.

- Content from the annotated article and tables are based on Schubert, MM, Astorino, TA & Azevedo, JJL 2013, ‘The effects of caffeinated ‘energy shots’ on time trial performance’, Nutrients, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 2062–2075 (used under a CC-BY 3.0 licence ) and P ing, WC, Keong , CC & Bandyopadhyay, A 2010, ‘Effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in a hot and humid climate’, Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 132, pp. 36–41 (used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence ).

Bain, A.R., Morrison, S.A., & Ainslie, P.N. (2014). Cerebral oxygenation and hyperthermia. Frontiers in Physiology, 5 , 92.

Pautasso, M. (2013). Ten simple rules for writing a literature review. PLoS Computational Biology, 9 (7), e1003149.

How To Do Science Copyright © 2022 by University of Southern Queensland is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

I’m worried I’ve been contacted by a predatory publisher — how do I find out?

Career Feature 15 MAY 24

How I fled bombed Aleppo to continue my career in science

Career Feature 08 MAY 24

Illuminating ‘the ugly side of science’: fresh incentives for reporting negative results

US halts funding to controversial virus-hunting group: what researchers think

News 16 MAY 24

Japan can embrace open science — but flexible approaches are key

Correspondence 07 MAY 24

US funders to tighten oversight of controversial ‘gain of function’ research

News 07 MAY 24

Mount Etna’s spectacular smoke rings and more — April’s best science images

News 03 MAY 24

Senior Postdoctoral Research Fellow

Senior Postdoctoral Research Fellow required to lead exciting projects in Cancer Cell Cycle Biology and Cancer Epigenetics.

Melbourne University, Melbourne (AU)

University of Melbourne & Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre

Overseas Talent, Embarking on a New Journey Together at Tianjin University

We cordially invite outstanding young individuals from overseas to apply for the Excellent Young Scientists Fund Program (Overseas).

Tianjin, China

Tianjin University (TJU)

Chair Professor Positions in the School of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology

SPST seeks top Faculty scholars in Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Chair Professor Positions in the School of Precision Instruments and Optoelectronic Engineering

We are committed to accomplishing the mission of achieving a world-top-class engineering school.

Chair Professor Positions in the School of Mechanical Engineering

Aims to cultivate top talents, train a top-ranking faculty team, construct first-class disciplines and foster a favorable academic environment.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.9(7); 2013 Jul

Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review

Marco pautasso.

1 Centre for Functional and Evolutionary Ecology (CEFE), CNRS, Montpellier, France

2 Centre for Biodiversity Synthesis and Analysis (CESAB), FRB, Aix-en-Provence, France

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications [1] . For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively [2] . Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests [3] . Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read [4] . For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way [5] .

When starting from scratch, reviewing the literature can require a titanic amount of work. That is why researchers who have spent their career working on a certain research issue are in a perfect position to review that literature. Some graduate schools are now offering courses in reviewing the literature, given that most research students start their project by producing an overview of what has already been done on their research issue [6] . However, it is likely that most scientists have not thought in detail about how to approach and carry out a literature review.

Reviewing the literature requires the ability to juggle multiple tasks, from finding and evaluating relevant material to synthesising information from various sources, from critical thinking to paraphrasing, evaluating, and citation skills [7] . In this contribution, I share ten simple rules I learned working on about 25 literature reviews as a PhD and postdoctoral student. Ideas and insights also come from discussions with coauthors and colleagues, as well as feedback from reviewers and editors.

Rule 1: Define a Topic and Audience

How to choose which topic to review? There are so many issues in contemporary science that you could spend a lifetime of attending conferences and reading the literature just pondering what to review. On the one hand, if you take several years to choose, several other people may have had the same idea in the meantime. On the other hand, only a well-considered topic is likely to lead to a brilliant literature review [8] . The topic must at least be:

- interesting to you (ideally, you should have come across a series of recent papers related to your line of work that call for a critical summary),

- an important aspect of the field (so that many readers will be interested in the review and there will be enough material to write it), and

- a well-defined issue (otherwise you could potentially include thousands of publications, which would make the review unhelpful).

Ideas for potential reviews may come from papers providing lists of key research questions to be answered [9] , but also from serendipitous moments during desultory reading and discussions. In addition to choosing your topic, you should also select a target audience. In many cases, the topic (e.g., web services in computational biology) will automatically define an audience (e.g., computational biologists), but that same topic may also be of interest to neighbouring fields (e.g., computer science, biology, etc.).

Rule 2: Search and Re-search the Literature

After having chosen your topic and audience, start by checking the literature and downloading relevant papers. Five pieces of advice here:

- keep track of the search items you use (so that your search can be replicated [10] ),

- keep a list of papers whose pdfs you cannot access immediately (so as to retrieve them later with alternative strategies),

- use a paper management system (e.g., Mendeley, Papers, Qiqqa, Sente),

- define early in the process some criteria for exclusion of irrelevant papers (these criteria can then be described in the review to help define its scope), and

- do not just look for research papers in the area you wish to review, but also seek previous reviews.

The chances are high that someone will already have published a literature review ( Figure 1 ), if not exactly on the issue you are planning to tackle, at least on a related topic. If there are already a few or several reviews of the literature on your issue, my advice is not to give up, but to carry on with your own literature review,

The bottom-right situation (many literature reviews but few research papers) is not just a theoretical situation; it applies, for example, to the study of the impacts of climate change on plant diseases, where there appear to be more literature reviews than research studies [33] .

- discussing in your review the approaches, limitations, and conclusions of past reviews,

- trying to find a new angle that has not been covered adequately in the previous reviews, and

- incorporating new material that has inevitably accumulated since their appearance.

When searching the literature for pertinent papers and reviews, the usual rules apply:

- be thorough,

- use different keywords and database sources (e.g., DBLP, Google Scholar, ISI Proceedings, JSTOR Search, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science), and

- look at who has cited past relevant papers and book chapters.

Rule 3: Take Notes While Reading

If you read the papers first, and only afterwards start writing the review, you will need a very good memory to remember who wrote what, and what your impressions and associations were while reading each single paper. My advice is, while reading, to start writing down interesting pieces of information, insights about how to organize the review, and thoughts on what to write. This way, by the time you have read the literature you selected, you will already have a rough draft of the review.

Of course, this draft will still need much rewriting, restructuring, and rethinking to obtain a text with a coherent argument [11] , but you will have avoided the danger posed by staring at a blank document. Be careful when taking notes to use quotation marks if you are provisionally copying verbatim from the literature. It is advisable then to reformulate such quotes with your own words in the final draft. It is important to be careful in noting the references already at this stage, so as to avoid misattributions. Using referencing software from the very beginning of your endeavour will save you time.

Rule 4: Choose the Type of Review You Wish to Write

After having taken notes while reading the literature, you will have a rough idea of the amount of material available for the review. This is probably a good time to decide whether to go for a mini- or a full review. Some journals are now favouring the publication of rather short reviews focusing on the last few years, with a limit on the number of words and citations. A mini-review is not necessarily a minor review: it may well attract more attention from busy readers, although it will inevitably simplify some issues and leave out some relevant material due to space limitations. A full review will have the advantage of more freedom to cover in detail the complexities of a particular scientific development, but may then be left in the pile of the very important papers “to be read” by readers with little time to spare for major monographs.

There is probably a continuum between mini- and full reviews. The same point applies to the dichotomy of descriptive vs. integrative reviews. While descriptive reviews focus on the methodology, findings, and interpretation of each reviewed study, integrative reviews attempt to find common ideas and concepts from the reviewed material [12] . A similar distinction exists between narrative and systematic reviews: while narrative reviews are qualitative, systematic reviews attempt to test a hypothesis based on the published evidence, which is gathered using a predefined protocol to reduce bias [13] , [14] . When systematic reviews analyse quantitative results in a quantitative way, they become meta-analyses. The choice between different review types will have to be made on a case-by-case basis, depending not just on the nature of the material found and the preferences of the target journal(s), but also on the time available to write the review and the number of coauthors [15] .

Rule 5: Keep the Review Focused, but Make It of Broad Interest

Whether your plan is to write a mini- or a full review, it is good advice to keep it focused 16 , 17 . Including material just for the sake of it can easily lead to reviews that are trying to do too many things at once. The need to keep a review focused can be problematic for interdisciplinary reviews, where the aim is to bridge the gap between fields [18] . If you are writing a review on, for example, how epidemiological approaches are used in modelling the spread of ideas, you may be inclined to include material from both parent fields, epidemiology and the study of cultural diffusion. This may be necessary to some extent, but in this case a focused review would only deal in detail with those studies at the interface between epidemiology and the spread of ideas.

While focus is an important feature of a successful review, this requirement has to be balanced with the need to make the review relevant to a broad audience. This square may be circled by discussing the wider implications of the reviewed topic for other disciplines.

Rule 6: Be Critical and Consistent

Reviewing the literature is not stamp collecting. A good review does not just summarize the literature, but discusses it critically, identifies methodological problems, and points out research gaps [19] . After having read a review of the literature, a reader should have a rough idea of:

- the major achievements in the reviewed field,

- the main areas of debate, and

- the outstanding research questions.

It is challenging to achieve a successful review on all these fronts. A solution can be to involve a set of complementary coauthors: some people are excellent at mapping what has been achieved, some others are very good at identifying dark clouds on the horizon, and some have instead a knack at predicting where solutions are going to come from. If your journal club has exactly this sort of team, then you should definitely write a review of the literature! In addition to critical thinking, a literature review needs consistency, for example in the choice of passive vs. active voice and present vs. past tense.

Rule 7: Find a Logical Structure

Like a well-baked cake, a good review has a number of telling features: it is worth the reader's time, timely, systematic, well written, focused, and critical. It also needs a good structure. With reviews, the usual subdivision of research papers into introduction, methods, results, and discussion does not work or is rarely used. However, a general introduction of the context and, toward the end, a recapitulation of the main points covered and take-home messages make sense also in the case of reviews. For systematic reviews, there is a trend towards including information about how the literature was searched (database, keywords, time limits) [20] .

How can you organize the flow of the main body of the review so that the reader will be drawn into and guided through it? It is generally helpful to draw a conceptual scheme of the review, e.g., with mind-mapping techniques. Such diagrams can help recognize a logical way to order and link the various sections of a review [21] . This is the case not just at the writing stage, but also for readers if the diagram is included in the review as a figure. A careful selection of diagrams and figures relevant to the reviewed topic can be very helpful to structure the text too [22] .

Rule 8: Make Use of Feedback

Reviews of the literature are normally peer-reviewed in the same way as research papers, and rightly so [23] . As a rule, incorporating feedback from reviewers greatly helps improve a review draft. Having read the review with a fresh mind, reviewers may spot inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and ambiguities that had not been noticed by the writers due to rereading the typescript too many times. It is however advisable to reread the draft one more time before submission, as a last-minute correction of typos, leaps, and muddled sentences may enable the reviewers to focus on providing advice on the content rather than the form.

Feedback is vital to writing a good review, and should be sought from a variety of colleagues, so as to obtain a diversity of views on the draft. This may lead in some cases to conflicting views on the merits of the paper, and on how to improve it, but such a situation is better than the absence of feedback. A diversity of feedback perspectives on a literature review can help identify where the consensus view stands in the landscape of the current scientific understanding of an issue [24] .

Rule 9: Include Your Own Relevant Research, but Be Objective

In many cases, reviewers of the literature will have published studies relevant to the review they are writing. This could create a conflict of interest: how can reviewers report objectively on their own work [25] ? Some scientists may be overly enthusiastic about what they have published, and thus risk giving too much importance to their own findings in the review. However, bias could also occur in the other direction: some scientists may be unduly dismissive of their own achievements, so that they will tend to downplay their contribution (if any) to a field when reviewing it.

In general, a review of the literature should neither be a public relations brochure nor an exercise in competitive self-denial. If a reviewer is up to the job of producing a well-organized and methodical review, which flows well and provides a service to the readership, then it should be possible to be objective in reviewing one's own relevant findings. In reviews written by multiple authors, this may be achieved by assigning the review of the results of a coauthor to different coauthors.

Rule 10: Be Up-to-Date, but Do Not Forget Older Studies

Given the progressive acceleration in the publication of scientific papers, today's reviews of the literature need awareness not just of the overall direction and achievements of a field of inquiry, but also of the latest studies, so as not to become out-of-date before they have been published. Ideally, a literature review should not identify as a major research gap an issue that has just been addressed in a series of papers in press (the same applies, of course, to older, overlooked studies (“sleeping beauties” [26] )). This implies that literature reviewers would do well to keep an eye on electronic lists of papers in press, given that it can take months before these appear in scientific databases. Some reviews declare that they have scanned the literature up to a certain point in time, but given that peer review can be a rather lengthy process, a full search for newly appeared literature at the revision stage may be worthwhile. Assessing the contribution of papers that have just appeared is particularly challenging, because there is little perspective with which to gauge their significance and impact on further research and society.

Inevitably, new papers on the reviewed topic (including independently written literature reviews) will appear from all quarters after the review has been published, so that there may soon be the need for an updated review. But this is the nature of science [27] – [32] . I wish everybody good luck with writing a review of the literature.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to M. Barbosa, K. Dehnen-Schmutz, T. Döring, D. Fontaneto, M. Garbelotto, O. Holdenrieder, M. Jeger, D. Lonsdale, A. MacLeod, P. Mills, M. Moslonka-Lefebvre, G. Stancanelli, P. Weisberg, and X. Xu for insights and discussions, and to P. Bourne, T. Matoni, and D. Smith for helpful comments on a previous draft.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB) through its Centre for Synthesis and Analysis of Biodiversity data (CESAB), as part of the NETSEED research project. The funders had no role in the preparation of the manuscript.

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

Literature Reviews

What this handout is about.

This handout will explain what literature reviews are and offer insights into the form and construction of literature reviews in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

Introduction

OK. You’ve got to write a literature review. You dust off a novel and a book of poetry, settle down in your chair, and get ready to issue a “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” as you leaf through the pages. “Literature review” done. Right?

Wrong! The “literature” of a literature review refers to any collection of materials on a topic, not necessarily the great literary texts of the world. “Literature” could be anything from a set of government pamphlets on British colonial methods in Africa to scholarly articles on the treatment of a torn ACL. And a review does not necessarily mean that your reader wants you to give your personal opinion on whether or not you liked these sources.

What is a literature review, then?

A literature review discusses published information in a particular subject area, and sometimes information in a particular subject area within a certain time period.

A literature review can be just a simple summary of the sources, but it usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis. A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information. It might give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations. Or it might trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates. And depending on the situation, the literature review may evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant.

But how is a literature review different from an academic research paper?

The main focus of an academic research paper is to develop a new argument, and a research paper is likely to contain a literature review as one of its parts. In a research paper, you use the literature as a foundation and as support for a new insight that you contribute. The focus of a literature review, however, is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of others without adding new contributions.

Why do we write literature reviews?

Literature reviews provide you with a handy guide to a particular topic. If you have limited time to conduct research, literature reviews can give you an overview or act as a stepping stone. For professionals, they are useful reports that keep them up to date with what is current in the field. For scholars, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the writer in his or her field. Literature reviews also provide a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. Comprehensive knowledge of the literature of the field is essential to most research papers.

Who writes these things, anyway?

Literature reviews are written occasionally in the humanities, but mostly in the sciences and social sciences; in experiment and lab reports, they constitute a section of the paper. Sometimes a literature review is written as a paper in itself.

Let’s get to it! What should I do before writing the literature review?

If your assignment is not very specific, seek clarification from your instructor:

- Roughly how many sources should you include?

- What types of sources (books, journal articles, websites)?

- Should you summarize, synthesize, or critique your sources by discussing a common theme or issue?

- Should you evaluate your sources?

- Should you provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history?

Find models

Look for other literature reviews in your area of interest or in the discipline and read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or ways to organize your final review. You can simply put the word “review” in your search engine along with your other topic terms to find articles of this type on the Internet or in an electronic database. The bibliography or reference section of sources you’ve already read are also excellent entry points into your own research.

Narrow your topic

There are hundreds or even thousands of articles and books on most areas of study. The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to get a good survey of the material. Your instructor will probably not expect you to read everything that’s out there on the topic, but you’ll make your job easier if you first limit your scope.

Keep in mind that UNC Libraries have research guides and to databases relevant to many fields of study. You can reach out to the subject librarian for a consultation: https://library.unc.edu/support/consultations/ .

And don’t forget to tap into your professor’s (or other professors’) knowledge in the field. Ask your professor questions such as: “If you had to read only one book from the 90’s on topic X, what would it be?” Questions such as this help you to find and determine quickly the most seminal pieces in the field.

Consider whether your sources are current

Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. In the sciences, for instance, treatments for medical problems are constantly changing according to the latest studies. Information even two years old could be obsolete. However, if you are writing a review in the humanities, history, or social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be what is needed, because what is important is how perspectives have changed through the years or within a certain time period. Try sorting through some other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to consider what is currently of interest to scholars in this field and what is not.

Strategies for writing the literature review

Find a focus.

A literature review, like a term paper, is usually organized around ideas, not the sources themselves as an annotated bibliography would be organized. This means that you will not just simply list your sources and go into detail about each one of them, one at a time. No. As you read widely but selectively in your topic area, consider instead what themes or issues connect your sources together. Do they present one or different solutions? Is there an aspect of the field that is missing? How well do they present the material and do they portray it according to an appropriate theory? Do they reveal a trend in the field? A raging debate? Pick one of these themes to focus the organization of your review.

Convey it to your reader

A literature review may not have a traditional thesis statement (one that makes an argument), but you do need to tell readers what to expect. Try writing a simple statement that lets the reader know what is your main organizing principle. Here are a couple of examples:

The current trend in treatment for congestive heart failure combines surgery and medicine. More and more cultural studies scholars are accepting popular media as a subject worthy of academic consideration.

Consider organization

You’ve got a focus, and you’ve stated it clearly and directly. Now what is the most effective way of presenting the information? What are the most important topics, subtopics, etc., that your review needs to include? And in what order should you present them? Develop an organization for your review at both a global and local level:

First, cover the basic categories

Just like most academic papers, literature reviews also must contain at least three basic elements: an introduction or background information section; the body of the review containing the discussion of sources; and, finally, a conclusion and/or recommendations section to end the paper. The following provides a brief description of the content of each:

- Introduction: Gives a quick idea of the topic of the literature review, such as the central theme or organizational pattern.

- Body: Contains your discussion of sources and is organized either chronologically, thematically, or methodologically (see below for more information on each).

- Conclusions/Recommendations: Discuss what you have drawn from reviewing literature so far. Where might the discussion proceed?

Organizing the body

Once you have the basic categories in place, then you must consider how you will present the sources themselves within the body of your paper. Create an organizational method to focus this section even further.

To help you come up with an overall organizational framework for your review, consider the following scenario:

You’ve decided to focus your literature review on materials dealing with sperm whales. This is because you’ve just finished reading Moby Dick, and you wonder if that whale’s portrayal is really real. You start with some articles about the physiology of sperm whales in biology journals written in the 1980’s. But these articles refer to some British biological studies performed on whales in the early 18th century. So you check those out. Then you look up a book written in 1968 with information on how sperm whales have been portrayed in other forms of art, such as in Alaskan poetry, in French painting, or on whale bone, as the whale hunters in the late 19th century used to do. This makes you wonder about American whaling methods during the time portrayed in Moby Dick, so you find some academic articles published in the last five years on how accurately Herman Melville portrayed the whaling scene in his novel.

Now consider some typical ways of organizing the sources into a review:

- Chronological: If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials above according to when they were published. For instance, first you would talk about the British biological studies of the 18th century, then about Moby Dick, published in 1851, then the book on sperm whales in other art (1968), and finally the biology articles (1980s) and the recent articles on American whaling of the 19th century. But there is relatively no continuity among subjects here. And notice that even though the sources on sperm whales in other art and on American whaling are written recently, they are about other subjects/objects that were created much earlier. Thus, the review loses its chronological focus.

- By publication: Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on biological studies of sperm whales if the progression revealed a change in dissection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies.

- By trend: A better way to organize the above sources chronologically is to examine the sources under another trend, such as the history of whaling. Then your review would have subsections according to eras within this period. For instance, the review might examine whaling from pre-1600-1699, 1700-1799, and 1800-1899. Under this method, you would combine the recent studies on American whaling in the 19th century with Moby Dick itself in the 1800-1899 category, even though the authors wrote a century apart.

- Thematic: Thematic reviews of literature are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time. However, progression of time may still be an important factor in a thematic review. For instance, the sperm whale review could focus on the development of the harpoon for whale hunting. While the study focuses on one topic, harpoon technology, it will still be organized chronologically. The only difference here between a “chronological” and a “thematic” approach is what is emphasized the most: the development of the harpoon or the harpoon technology.But more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. For instance, a thematic review of material on sperm whales might examine how they are portrayed as “evil” in cultural documents. The subsections might include how they are personified, how their proportions are exaggerated, and their behaviors misunderstood. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point made.

- Methodological: A methodological approach differs from the two above in that the focusing factor usually does not have to do with the content of the material. Instead, it focuses on the “methods” of the researcher or writer. For the sperm whale project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of whales in American, British, and French art work. Or the review might focus on the economic impact of whaling on a community. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed. Once you’ve decided on the organizational method for the body of the review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out. They should arise out of your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period. A thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue.

Sometimes, though, you might need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. Put in only what is necessary. Here are a few other sections you might want to consider:

- Current Situation: Information necessary to understand the topic or focus of the literature review.

- History: The chronological progression of the field, the literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Methods and/or Standards: The criteria you used to select the sources in your literature review or the way in which you present your information. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed articles and journals.

Questions for Further Research: What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

Begin composing

Once you’ve settled on a general pattern of organization, you’re ready to write each section. There are a few guidelines you should follow during the writing stage as well. Here is a sample paragraph from a literature review about sexism and language to illuminate the following discussion:

However, other studies have shown that even gender-neutral antecedents are more likely to produce masculine images than feminine ones (Gastil, 1990). Hamilton (1988) asked students to complete sentences that required them to fill in pronouns that agreed with gender-neutral antecedents such as “writer,” “pedestrian,” and “persons.” The students were asked to describe any image they had when writing the sentence. Hamilton found that people imagined 3.3 men to each woman in the masculine “generic” condition and 1.5 men per woman in the unbiased condition. Thus, while ambient sexism accounted for some of the masculine bias, sexist language amplified the effect. (Source: Erika Falk and Jordan Mills, “Why Sexist Language Affects Persuasion: The Role of Homophily, Intended Audience, and Offense,” Women and Language19:2).

Use evidence

In the example above, the writers refer to several other sources when making their point. A literature review in this sense is just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence to show that what you are saying is valid.

Be selective

Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the review’s focus, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological.

Use quotes sparingly

Falk and Mills do not use any direct quotes. That is because the survey nature of the literature review does not allow for in-depth discussion or detailed quotes from the text. Some short quotes here and there are okay, though, if you want to emphasize a point, or if what the author said just cannot be rewritten in your own words. Notice that Falk and Mills do quote certain terms that were coined by the author, not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. But if you find yourself wanting to put in more quotes, check with your instructor.

Summarize and synthesize

Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each paragraph as well as throughout the review. The authors here recapitulate important features of Hamilton’s study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study’s significance and relating it to their own work.

Keep your own voice

While the literature review presents others’ ideas, your voice (the writer’s) should remain front and center. Notice that Falk and Mills weave references to other sources into their own text, but they still maintain their own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with their own ideas and their own words. The sources support what Falk and Mills are saying.

Use caution when paraphrasing