Reporting Participant Characteristics in a Research Paper

A report on a scientific study using human participants will include a description of the participant characteristics. This is included as a subsection of the “Methods” section, usually called “Participants” or “Participant Characteristics.” The purpose is to give readers information on the number and type of study participants, as a way of clarifying to whom the study findings apply and shedding light on the generalizability of the findings as well as any possible limitations. Accurate reporting is needed for replication studies that might be carried out in the future.

The “Participants” subsection should be fairly short and should tell readers about the population pool, how many participants were included in the study sample, and what kind of sample they represent, such as random, snowball, etc. There is no need to give a lengthy description of the method used to select or recruit the participants, as these topics belong in a separate “Procedures” subsection that is also under “Methods.” The subsection on “Participant Characteristics” only needs to provide facts on the participants themselves.

Report the participants’ genders (how many male and female participants) and ages (the age range and, if appropriate, the standard deviation). In particular, if you are writing for an international audience, specify the country and region or cities where the participants lived. If the study invited only participants with certain characteristics, report this, too. For example, tell readers if the participants all had autism, were left-handed, or had participated in sports within the past year.

Related: Finished preparing the methods sections for your research paper ? Find out why the “Methods” section is so important now!

Next, use your judgment to identify other pieces of information that are relevant to the study. For a detailed tutorial on reporting “Participant Characteristics,” see Alice Frye’s “Method Section: Describing participants.” Frye reminds authors to mention if only people with certain characteristics or backgrounds were included in the study. Did all the participants work at the same company? Were the students at the same school? Did they represent a range of socioeconomic backgrounds? Did they come from both urban and rural backgrounds? Were they physically and emotionally healthy? Similarly, mention if the study sample excluded people with certain characteristics.

If you are going to examine any participant characteristics as factors in the analysis, include a description of these. For instance, if you plan to examine the influence of teachers’ years of experience on their attitude toward new technology, then you should report the range of the teachers’ years of experience. If you plan to study how children’s socioeconomic level relates to their test scores, you should briefly mention that the children in the sample came from low, middle, and high-income backgrounds. Finally, mention whether the participants participated voluntarily. Include information on whether they gave informed consent (if the participants were children, mention that their parents consented to their participation). Also, mention if the participants received any sort of compensation or benefit for their participation, such as money or course credit.

Case Studies and Qualitative Reports

Case studies and qualitative reports may have only a few participants or even a single participant. If there is space to do so, you can write a brief background of each participant in the “Participants” section and include relevant information on the participant’s birthplace, current place of residence, language, and any life experience that is relevant to the study theme. If you have permission to use the participant’s name, do so. Otherwise, use a different name and add a note to readers that the name is a pseudonym. Alternatively, you might label the participants with numbers (e.g., Student 1, Student 2) or letters (e.g., Doctor A, Doctor B, etc.), or use initials to identify them (e.g., KY, JM).

Use Past Tense

Remember to use past tense when writing the “Participants” section . This is because you are describing what the participants’ characteristics were at the time of data collection . By the time your article is published, the participants’ characteristics may have changed. For example, they may be a year older and have more work experience. Their socioeconomic level may have changed since the study. In some cases, participants may even have passed away. While characteristics like gender and race are either unlikely or impossible to change, the whole section is written in the past tense to maintain a consistent style and to avoid making unsupported claims about what the participants’ current status is.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- AI in Academia

- Infographic

- Manuscripts & Grants

- Reporting Research

- Trending Now

Can AI Tools Prepare a Research Manuscript From Scratch? — A comprehensive guide

As technology continues to advance, the question of whether artificial intelligence (AI) tools can prepare…

Abstract Vs. Introduction — Do you know the difference?

Ross wants to publish his research. Feeling positive about his research outcomes, he begins to…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Demystifying Research Methodology With Field Experts

Choosing research methodology Research design and methodology Evidence-based research approach How RAxter can assist researchers

- Manuscript Preparation

- Publishing Research

How to Choose Best Research Methodology for Your Study

Successful research conduction requires proper planning and execution. While there are multiple reasons and aspects…

Top 5 Key Differences Between Methods and Methodology

While burning the midnight oil during literature review, most researchers do not realize that the…

How to Draft the Acknowledgment Section of a Manuscript

Discussion Vs. Conclusion: Know the Difference Before Drafting Manuscripts

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Audience

What are Demographic Examples

What is a demographic?

Demographics are statistical data that researchers use to study groups of humans. A demographic refers to distinct characteristics of a population. Researchers use demographic analysis to analyze whole societies or just groups of people. Some examples of demographics are age, sex, education, nationality, ethnicity, or religion, to name a few.

Select your respondents

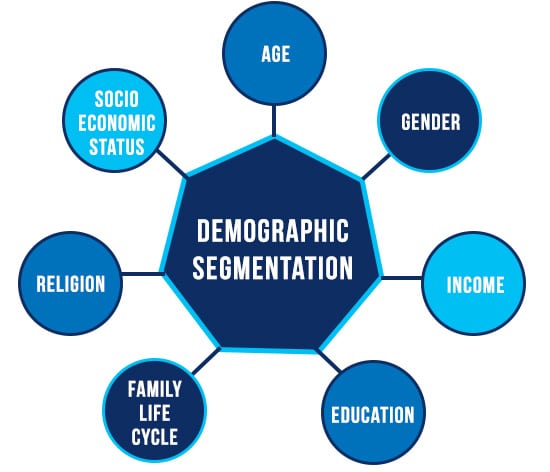

What are the various examples of demographic segmentation?

Demographic segmentation examples explain how researchers divide a market into smaller groups according to age, gender, family income, race and ethnicity, qualification, marital status, nature of employment, etc.

It is an extremely tedious task to accommodate customers belonging to different demographics and develop an exhaustive marketing plan. Demographic examples ease creating a strategy for a marketer. Thus, they are one of the most commonly implemented marketing segmentation methods compared to other techniques such as geographic segmentatio n, behavioral segmentation , or psychographic segmentation . As the details required for demographic examples are easily accessible, marketers have gained popularity to gather and analyze immense data in brief periods.

According to demographic diversity, dividing the target audience will help a marketer design an accurate marketing plan that will yield productive results. The products or services that interest a White, 13-year-old boy, might not interest a 40-year-old Asian woman.

Demographic examples:

- Age segmentation – Age is one of the most common demographic segmentation elements. Every age group has its peculiar characteristics and needs. Generally, teenagers might be more inclined towards the latest, good looking cars, but working professionals would require a vehicle that caters to his/her family and fits a particular budget. Every age group has a specific requirement, which will be extremely different from the other age groups’ needs. Babies require a constant supply of diapers, select clothing, formula, and other such products, while toddlers require educational toys, coloring books, products that stimulate their mental and physical growth. Middle-aged adults may invest a lot more in an expensive technological gadget than a teenager. An old-aged person would rather spend their money on buying health-related products. As seen in all these examples, every segment has specific requirements, and organizations can develop marketing strategies based on these requirements to obtain valid results.

- Family segmentation – There is a lot of variation in this segmentation type. A lot of families have one or multiple children. Some have single mothers or fathers; others have gay parents with one or more children; while some are child-free and straight. Child-free families will never purchase products related to children, such as baby lotion, toys, or diapers. A multinational organization that is into developing these products will conduct demographic examples based on the type of family. Single parents will be more inclined to save costs at various products that might not concern most child-free people.

- Gender segmentation – Gender is quite a primary category to conduct segmentation. Every gender has specific characteristics that are distinct and instrumental in decision-making. It is very natural for males, females, transgender people, to have different likes and dislikes. Men might not be as interested in makeup or fashion accessories in a manner that women will be. Gender defines people’s preferences. Females are usually into makeup products, and there are currently more females who show interest in the latest fashion products. Based on these characteristics, makeup, or fashion brands can create a marketing strategy that targets women to get better business results.

- Race and ethnicity segmentation – Race and ethnicity are sensitive categories. Promoting a product depends on that target race or ethnicity as it may be adapted differently by each of these races/ethnicities. People belonging to different races will have different food preferences, clothing habits, and many other attributes. Stereotypical segmentation may hurt sentiments, which may cause harm to a business.

- Family income segmentation – One of the most straightforward segmentation types is based on income. An individual or a family’s income would govern their ability to purchase different cost categories’ products/services. A person who can barely afford to provide food and shelter for his/her family would not afford an iPhone. Companies that offer luxury cars or watches must target customers who have a considerable amount of extra earnings. The most likely target audience of an organization that affordable mobile phones will be mid to low income customers.

Other demographic examples

Here are a few more demographic examples that researchers commonly use:

- Employment status: Business-owner, self-employed, unemployed, employed, retired.

- Living status: Home-owner, rented, lease.

- Education level: Graduate degree, undergrad, college degree, high school.

- Religion: Atheist, Muslim, Christian, Jew, Hindu, Buddhist

- Marital status: Single, married, separated, widow/ widower.

- The number of children: None, 1, 2, 3-5, more than 5.

- Political affiliation: Democrat, republic, independent.

- Nationality: American, Mexican, French, Indian, German

Advantages of demographic segmentation:

There are several advantages of dividing the target audience according to demographics.

- As the census is carried out regularly by the government, demographic data can be easily retrieved. An organization can easily divide data into required categories, creating an effective marketing strategy for each of these demographics.

- According to the demographic data requirement of an organization, age, gender, income, race, etc. can be adjusted and implemented.

- Factors such as family income, type of family, etc., give insights that will decide the consumers’ purchasing power. An organization can decide whether or not to target a particular group of consumers based on these classifications.

- Considering that a lot of effort goes into dividing a target audience into demographic segments, an organization modifies marketing strategies based on each segment’s requirements. There are high chances of increased customer satisfaction , loyalty, and increased retention rates due to this.

- In the longer run, demographic examples will help in reducing cost and time invested in developing and implementing a marketing strategy as all marketing efforts will be carefully calculated according to the various segments.

- This method is better at understanding a target market and creating policies that pertain to each of these markets.

MORE LIKE THIS

Customer Communication Tool: Types, Methods, Uses, & Tools

Apr 23, 2024

Top 12 Sentiment Analysis Tools for Understanding Emotions

QuestionPro BI: From research data to actionable dashboards within minutes

Apr 22, 2024

21 Best Customer Experience Management Software in 2024

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Finding Statistics and Demographics

- Searching for Articles

- Books and eBooks

- Searching the Web

- Writing & Citing

Incorporating Statistical Information into your Writing

1. Go to the original source:

Rather than relying on a blog, magazine or newspaper restating a statistic from a larger study or publication, try your best to locate the original report mentioned. If the short article you are reading cites statistics with no reference to the source, the article ought to be avoided.

For example, on January 12, 2016, a news article from KVUE in Austin mentions, "Affordability issues are expected to continue impacting the number of students within the district, and the report expecting about 600 fewer students in the district each year due to multiple factors." ( https://www.kvue.com/news/austin-isd-releases-annual-demographic-report/39601312 ; screenshot )

However, the article includes a link to the full PDF demographic report on the Austin ISD website ( https://www.austinisd.org ; screenshot ).

2. Provide context:

Introduce the data for the reader by mentioning within the text both the source of the research statistic and the survey or study that was conducted.

For example, using the above example, you might want to mention:

The Austin Independent School District conducts an annual demographics report as well as projection studies for school district planning. According to their 2015 Ten Year Student Population Projections , the district has " experienced a reduction in student population since SY 2013, primarily at the Prekindergarten and Kindergarten grade levels, and can be attributed to decreasing birth rates and lower births to kindergarten relationship (market share)."

3. Use tables or diagrams in some cases:

If you are citing numerous statistics or lots of information, provide tables or diagrams to visually present the data. You can include and cite tables from the original source or adapt to create a table or diagram from borrowed sources. Do not distort or misrepresent the original data.

You will include a caption citation under any figure, map, table, diagram, whether pulled directly from a source or adapted from one or more sources.

If you embed an image of a map, table or diagram into your paper, make sure the image quality is readable.

4. Use caution in application:

Be careful how you are applying your statistical information. Make sure it is relevant to your topic and that you apply the statistic in the correct circumstance. Do not intentionally or accidentally use statistical sources of information to make faulty assumptions of cause or potential effect.

Helpful Links

- MLA Tables, Figures, and Examples

- Quick Tips on Writing with Statistics

- Writing with Statistics: Overview and Introduction

Know Your Citation Styles

The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA) is commonly used in the social sciences. It provides two different format styles, one for students and one for professionals. Confirm which style you should use with your instructor.

Use your APA manual or the links below to learn more about APA requirements.

- APA Style Help - This link leads to the official APA website.

- APA Quick Guide for References - This link also leads to the official APA website.

- APA 7 Formatting and Style Guide - This link leads to the Purdue OWL website.

- Citing AI Image or Text Generators in APA This link leads to the official APA website.

- Citing Government Sources APA Style - This link leads to the WLU government guide.

- Citing AI Sources in APA Style - This article leads to the official APA website. Use this method to cite all AI text generators.

The Chicago Manual of Style (CMS) is commonly used in the humanities. It provides the option of two different documentation styles, so ask whether your instructor requires the author-date style or the notes-bibliography style.

Use your CMS manual or the links below to learn more about CMS requirements.

- Chicago-Style Citation Quick Guide - This link leads to the official CMS website.

- CMS Format Guide - This link leads to the Purdue OWL website.

- Citing AI Image Generators in CMS This link leads to the official CMS website. Use this method to cite all AI image generators.

- Citing AI Text Generators in CMS This link leads to the official CMS website. Use this method to cite all AI text generators.

The Modern Language Association (MLA) Handbook is commonly used in the humanities. It is particularly popular for English courses, but confirm with your instructor before using it.

Use your MLA manual or the links below to learn more about MLA requirements.

- Using MLA Format - This link leads to the official MLA website.

- MLA Works Cited Quick Guide - This link also leads to the official MLA website.

- MLA Style and Format Guide - This link leads to the Purdue OWL website.

- Citing AI Image or Text Generators in MLA This link leads to the official MLA website.

A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (called Turabian style) is a modified form of the Chicago Manual of Style (CMS) and is commonly used for student work in the humanities. Confirm with your instructor before using it.

Use your Turabian manual or the links below to learn more about Turabian requirements.

- Turabian-style Citation Quick Guide - This link leads to the official Turabian website.

- Turabian Student Paper Formatting Tips - This link also leads to the official Turabian website.

- << Previous: Searching the Web

- Last Updated: Feb 28, 2024 2:04 PM

- URL: https://mclennan.libguides.com/stats

© McLennan Community College

1400 College Drive Waco, Texas 76708, USA

+1 (254) 299-8622

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Are Demographics?

Understanding demographics, types of demographic information, special considerations.

- Demographics FAQs

The Bottom Line

Demographics: how to collect, analyze, and use demographic data.

Adam Hayes, Ph.D., CFA, is a financial writer with 15+ years Wall Street experience as a derivatives trader. Besides his extensive derivative trading expertise, Adam is an expert in economics and behavioral finance. Adam received his master's in economics from The New School for Social Research and his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in sociology. He is a CFA charterholder as well as holding FINRA Series 7, 55 & 63 licenses. He currently researches and teaches economic sociology and the social studies of finance at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/adam_hayes-5bfc262a46e0fb005118b414.jpg)

Yarilet Perez is an experienced multimedia journalist and fact-checker with a Master of Science in Journalism. She has worked in multiple cities covering breaking news, politics, education, and more. Her expertise is in personal finance and investing, and real estate.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/YariletPerez-d2289cb01c3c4f2aabf79ce6057e5078.jpg)

Demographics are statistics that describe populations and their characteristics. Demographic analysis is the study of a population-based on factors such as age, race, and sex. Demographic data refers to socioeconomic information expressed statistically, including employment, education, income, marriage rates, birth and death rates, and more.

Governments, corporations, and non-government organizations use demographics to learn more about a population's characteristics for many purposes, including policy development and economic market research . For example, a company that sells high-end RVs may want to reach people nearing or at retirement age and the percentage of those who can afford their products.

Key Takeaways

- Demographic analysis is the collection and analysis of broad characteristics about groups of people and populations.

- Demographic data is very useful for businesses to understand how to market to consumers and plan strategically for future trends in consumer demand.

- The combination of the internet, big data, and artificial intelligence is greatly amplifying the usefulness and application of demographics as a tool for marketing and business strategy.

- Market segments are often grouped by age or generation.

- Demographic information can be used in many ways to learn more about the generalities of a particular population.

Investopedia / Paige McLaughlin

Demographic analysis is the collection and study of data regarding the general characteristics of specific populations . It is frequently used as a business marketing tool to determine the best way to reach customers and assess their behavior. Segmenting a population by using demographics allows companies to determine the size of a potential market.

The use of demographics helps determine whether its products and services are being targeted to that company's most influential consumers. For example, market segments may identify a particular age group, such as baby boomers (born 1946–1964) or millennials (born 1981–1996), with specific buying patterns and characteristics.

The advent of the internet, social media, predictive algorithms, and big data has dramatic implications for collecting and using demographic information. Modern consumers give out a flood of data, sometimes unwittingly, collected and tracked through their online and offline lives by myriad apps, social media platforms, third-party data collectors, retailers, and financial transaction processors.

Combined with the growing field of artificial intelligence, this mountain of collected data can be used to predict and target consumer choices and buying preferences with uncanny accuracy based on their demographic characteristics and past behavior.

For corporate marketing goals, demographic data is collected to build a customer base profile. The common variables gathered in demographic research include age, sex, income level, race, employment, location, homeownership, and level of education. Demographical information makes certain generalizations about groups to identify customers.

Additional demographic factors include gathering data on preferences, hobbies, lifestyle, and more. Governmental agencies collect data when conducting a national census and may use that demographic data to forecast economic patterns and population growth to better manage resources.

You can gather demographic information on a large group and then break it down into smaller subsets for deeper dive into your research.

Most large companies conduct demographic research to determine how to market their product or service and best market to the target audience. It is valuable to know the current customer and where the potential customer may come from in the future. Demographic trends are also significant since the size of different demographic groups changes over time due to economic, cultural, and political circumstances.

This information helps the company decide how much capital to allocate to production and advertising. For example, the aging U.S. population has specific needs that companies want to anticipate. Each market segment can be analyzed for its consumer spending patterns. Older demographic groups spend more on healthcare products and pharmaceuticals, and communicating with these customers differs from that of their younger counterparts.

Why Do Demographics Matter?

Demographics refers to the description or distribution of characteristics of some target audience, customer base, or population. Governments use socioeconomic information to understand the age, racial makeup, and income distribution (among several other variables) in neighborhoods, cities, states, and nations in order to make better public policy decisions.

Companies look to demographics to craft more effective marketing and advertising campaigns and to understand patterns among different audiences.

Who Collects Demographic Data?

The U.S. Census Bureau collects demographic data on the American population every year through the American Community Survey (ACS) and every 10-years via an in-depth count of every American household. Companies use marketing departments or outsource to specialized marketing firms to collect demographics on users, customers, or prospective client groups. Academic researchers also collect demographic data for research purposes using various survey instruments. Political parties and campaigns also collect demographics in order to target messaging for political candidates.

Why Do Businesses Need Demographics?

Demographics are key to businesses today. They help identify the individual members of an audience by selecting key characteristics, wants, and needs. This allows companies to tailor their efforts based on particular segments of their customer base. Online advertising and marketing have made enormous headway over the past decade in using algorithms and big data analysis to micro-target ads on social media to very specific demographics.

How Are Demographic Changes Important for Economists?

Economists recognize that one of the major drivers of economic growth is population growth or decline . There is a straightforward relationship when identifying this: Growth Rate of Gross Domestic Product (GDP)=Growth Rate of Population+Growth Rate of GDP per capita , where GDP per capita is simply GDP divided by population. The more people around, the more available workers there are in the labor force, and also more people to consume items like food, energy, cars, and clothes. There are also demographic problems that lie on the horizon, such as an increasing number of retirees who, while no longer in the workforce, are nonetheless expected to live longer lives. Unfortunately, the number of new births seems to be too low to replace those retirees in the workforce.

Demographics and demographic analysis is used to describe the distribution of characteristics in a society or other population in order to understand them, make policy recommendations, and make predictions about where a society or group is headed in the future. Demographic data can come in many forms, but most often describes the distribution of characteristics found in populations such as age, sex/gender, marital status, household structure, income, wealth, education, religion, and so on - and to see how these are changing over time. Birth and death rates are also used to understand if a population is growing or not, and how this might affect things like economic growth, employment, government programs like social security, and so on.

University of North Florida. " What are Demographics? "

Pew Research Center. " Defining Generations: Where Millennials End and Generation Z Begins ."

United States Census Bureau. " What We Do ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Market-Segmenation-76c1fe9e48ff4906bc2a565bb67c6862.png)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications. If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Virtual Issues

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Journal of Pediatric Psychology

- About the Society of Pediatric Psychology

- Editorial Board

- Student Resources

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Reporting of Demographics, Methodology, and Ethical Procedures in Journals in Pediatric and Child Psychology

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Sarah K. Sifers, Richard W. Puddy, Jared S. Warren, Michael C. Roberts, Reporting of Demographics, Methodology, and Ethical Procedures in Journals in Pediatric and Child Psychology, Journal of Pediatric Psychology , Volume 27, Issue 1, January 2002, Pages 19–25, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.19

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Objective: To identify potential problems in methodology reporting that may limit research interpretations and generalization.

Methods: We examined the rates at which articles in four major journals publishing research in pediatric, clinical child, and child psychology report 18 important demographic, methodological, and ethical information variables, such as participants' gender, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and consent and assent procedures.

Results: Overall, participants' ages, genders, and ethnicity were reported at moderate to high rates, whereas socioeconomic status was reported less often. Reports of research methodology frequently did not include information on how and where participants were recruited, the participation/consent rates, or attrition rates. Consent and assent procedures were not frequently described.

Conclusions: There is wide variability in articles reporting key demographic, methodological, and ethical procedure information. Necessary information about characteristics of participation samples, important for drawing conclusions, is lacking in the flagship journals serving the child psychology field.

Among the hallmarks of the sciences, including the science of psychology, are an objective perspective and the ability to evaluate and replicate research methodology. Inherent in these is the comprehensive and accurate description of the research sample, the population from which it is drawn, and the methodology used to gather the data. In recognition of the communication requirements for science, the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association ( APA, 1994 ) states that, when the participants in a research study are human, certain information should be presented in the Method section of a manuscript considered for publication in a journal (see Section 1.09, pp. 12-15). This necessary information includes details regarding major demographic variables, the number of participants, method of selecting participants, assignment to groups, agreements made, payments made, and the number of participants who withdrew from the study and why. Additionally, this information may include, but is not limited to, ethnicity, level of educational attainment, and type of geographic area in which the participants reside.

The APA Publication Manual has assumed a leading position in dictating publication standards, not only for the primary APA journals but also for the numerous other journals in psychology and related fields. As representative of agreed-upon standards, the Publication Manual presented the reasons for fully describing the research participants:

Appropriate identification of research participants and clientele is critical to the science and practice of psychology, particularly for assessing the results (making comparisons across groups), generalizing the findings, and making comparisons in replications, literature reviews, or secondary data analyses. The sample should be adequately described. (p. 13)

Furthermore, the precise reporting of methods and demographics is especially important when determining the generalizability of research findings with children and adolescents. This is particularly important because psychologically manifested differences as a result of gender, development, or other factors may be more prominent in children and adolescents. Lack of adequate information is a methodological weakness placing considerable constraints on interpretation and conclusions in pediatric and clinical child psychology.

The Publication Manual also states that, in order to be published in an APA journal, either the manuscript or a cover letter to the editor of the journal should indicate that the researchers followed all ethical standards set forth in the APA Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct ( APA, 1992 ). These guidelines seek to ensure the protection of the interests of the participants, as well as providing important information to the consumers of the research.

Given the importance for published articles to present demographic, methodological, and ethics-related information, it is worthwhile to periodically examine psychology publications for compliance to these standards of scientific communication. A few previous reports have provided some information related to the completeness of research articles in describing the characteristics of the sample and the ethical procedures used in the study (e.g., Bernal & Enchautegui-de-Jesus, 1994 ; Betan, Roberts, & McCluskey-Fawcett, 1995 ; Graham, 1992 ; Park, Adams, & Lynch, 1998 ; Phares & Compas, 1992 ; Ponterotto, 1988 ). These reports indicate that there is considerable neglect of methodological information in published articles, with some discrepancy depending on the variable and the specialty. The research methodology literature has long called for comprehensive description of research samples (e.g., Bordens & Abbott, 1996 ; Hersen & Bellack, 1984 ).

Content analyses of journals help discern patterns in the development of a field or subdiscipline and provide objective “snapshots” useful in evaluating its science ( Elkins & Roberts, 1988 ; Peterson, 1996 ; Roberts, McNeal, Randall, & Roberts, 1996 ). They provide the field with an additional tool for assessing its past and current status. This examination is important because it allows for self-correction when oversights are detected, as well as the opportunity to set new directions. Consequently, we applied the technique of journal content analysis to determine the presence of and utility of comprehensive information reported in four publication outlets in pediatric and clinical child psychology. This study focused on the rates at which articles reported key demographic, methodological, and ethical variables such as number of participants, age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), location of participants, rewards given to participants, exclusion and inclusion criteria, attrition, and consent and assent procedures.

The database included all empirical research articles published during 1997 in Journal of Pediatric Psychology (JPP , 58 articles), Journal of Clinical Child Psychology (JCCP , 52 articles), Child Development ( CD , 94 articles), and Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology ( JACP , 56 articles). Review articles, editorial articles, addresses, case studies, and studies that did not include human participants were excluded from this review. In total, 260 articles were coded and included in this study.

Coding Procedure

The coding procedure was based on the procedure used by previous content analyses ( Betan et al., 1995 ; Elkins & Roberts, 1988 ; Roberts, 1992 ). For articles containing more than one study, the studies were coded separately. Four graduate students read and coded all the articles. Interrater reliability was calculated on over 10% of the articles. Each article was coded using a checklist with 18 items regarding characteristics of the study and its participants. Kappa interrater reliability coefficients are presented, as well as the percent agreement between rates for each coded variable: (1) ages (1.0; 100%), (2) gender (.47; 92%), (3) ethnic distribution (.92, 96%), (4) SES (.55; 77%), (5) identification/selection of sample (e.g., requested, teacher recommended, records:.38, 81%), (6) population (e.g., general/school children, physical disability: 1.0; 100%), (7) setting of sample (e.g., school, psychological clinic, hospital:.29; 77%), (8) method of contacting participants (e.g., via mail, information sent via child:.57; 81%), (9) number of contacts requested (.36; 77%), (10) total contact time (.77; 89%), (11) exclusion/inclusion criteria (.34; 69%), (12) attrition (.35; 81%), (13) reliability of dependent measures used in study (.43; 73%), (14) number of participants (1.0; 100%), (15) location (geographically where sample was recruited:.58; 85%), (16) reward offered for participation or time/expense (1.0; 100%), (17) consent rate (after solicitation, participants who agreed to study versus those who did not: (.74; 88%), and (18) child assent (.47; 92%). Lower kappa coefficients were observed on a number of variables in part due to the lack of variability observed within some variables. (A copy of the decision rules for coding can be obtained from Michael Roberts.)

The frequency and percentage of articles reporting the variables were calculated for each journal individually, as well as for the journals overall (see Table I ). As can be seen in the total column, some variables tend to get reported at a fairly high rate across journals. The number of participants is reported in all the journals at a 100% level. The participants' ages are included very close to that perfect mark, as are the types of population from which the sample is drawn. Also reported at a high rate are setting of the research, the gender of the participants, and the methods of identifying and selecting participants. At the middle levels of reporting overall are characteristics such as participants' ethnicity, SES, exclusion/inclusion criteria used, reliability reporting, number of contacts requested, and methods of contacting participants. Low rates of reporting were found overall for child assent, parent consent, attrition rates, whether rewards were used, the location of the research project, and total contact time.

Frequency and Percentages of Articles Reporting Demographic, Methodological, and Ethical Information

Within these overall trends, the journals varied as to whether each included or omitted some of the information components. One-sample t tests were conducted for each journal to determine if the frequency with which each reported study variable differed significantly from the other journals. The mean of the four journals on each variable was used as the test value (all analyses used two-tailed levels of significance). Based on these analyses, JPP reported identification/selection methods ( t [57] = -3.061, p =.003), setting of the sample ( t [57] = -3.952, p <.001), method of contacting participants ( t [57] = -3.258, p =.002), exclusion/inclusion criteria ( t [57] = -2.475, p =.016), and parental consent ( t [57] = -2.548, p =.014) significantly more frequently than the other journals. JCCP reported gender ( t [51] = -6.202, p <.001), ethnicity ( t [51] = -4.263, p <.001), and child assent procedures ( t [51] = -2.356, p =.022) significantly more frequently than the other journals, whereas it reported significantly less frequently information on total contact time ( t [51] = 2.833, p =.007). CD reported the number of contacts requested ( t [93] = -3.791, p <.001) and total contact time ( t [93] = -2.638, p =.010) significantly more frequently than the other journals, whereas it reported information less frequently than the other journals on ethnicity ( t [93] = 2.114, p =.037), identification/selection methods ( t [93] = 3.245, p =.002), setting of the sample ( t [93] = 2.573, p =.012), method of contacting participants ( t [93] = 2.575, p =.012), parental consent ( t [93] = 3.092, p =.003), and child assent procedures ( t [93] = 3.597, p =.001). The rates of reporting variables in JACP did not differ significantly from the other journals.

A basic demographic description of the participants' gender ranged from a low of 80.4 % ( JACP ) to a high of 98.1% ( JCCP ). The percentage of articles that described the ethnic distribution of the participants varied greatly from a low 52.1% ( CD ) to a high of 84.6% ( JCCP ). CD reported the low of 43.6% of the participants' SES while JPP reported the high of 51.7%. The rate at which articles in this study indicated the geographic location of the sample ranged from the low 31% of JPP to a high of 42.6% of CD . The percentage of studies reporting whether a reward was offered was small and varied from 13.5% ( JCCP ) to 25.9% ( JPP ). The percentage of articles reporting consent rate differed from the low of 27.7% ( CD ) to 58.6% ( JPP ). The rate of reporting child assent also was low and significantly varied 8.5% ( CD ) to 34.6% ( JCCP ). Although just over half of the articles reported inclusion/exclusion criteria, the rate varied significantly from 48.1% ( JCCP ) to 70.7% ( JPP ). Across journals, just over a fourth of the articles reported causes for attrition, although rates differed from 19.6% ( JACP ) to 36.2% ( JPP ).

In general, the results of this study suggest wide variability in the percentage of articles that reported key demographic, methodological, and ethical procedure items. This variability was observed across journals and across variables. The conclusion seems clear that, in general, articles published in flagship journals serving the pediatric and child psychology field do not provide needed information about characteristics of their participation samples. These journals ostensibly adhere to the APA Publication Manual for manuscript preparation, which calls for authors to include this detailed information.

The participants' ages and gender tend to be reported at a fairly high rate. This rate for age is higher than for “adult” research journals such as Health Psychology ( Park et al., 1998 ) likely because these four journals have more of a developmental focus. Ethnicity information, although left out of many articles, seems to be higher than found in previous content analyses and in other specialties in psychology. Ethnicity description is likely present in these later reports because of the many efforts to enhance recognition of diversity issues in psychology research (e.g., Iijima Hall, 1998 ). Of course, the overall percentage of 63.1% indicates only that this information was reported in some form, even if only a general statement of predominant ethnicity, not specific breakdowns. Such global information does not indicate anything about the ethnic representativeness of the sample to the larger population, degree of acculturation, or other aspects, for example. Similarly, the SES information was provided in about half of the studies. Age, gender, ethnicity, and SES are demographic characteristics important to most of the psychological variables under study in these research articles. The omission of even this basic or minimal information restricts the research consumers' ability to draw proper conclusions.

How to report ethnicity and cultural variables for research publications requires further clarification by the field, given the complexities inherent in these phenomena. Our analyses indicated only whether some information was presented, not the precision with which the information was reported. When ethnicity of the participants was indicated in the articles we analyzed, what typically was included was a general statement about race (i.e., African American, Asian American, Hispanic American, Native American, Caucasian, or Euro-American). Unfortunately, the majority of the articles did not describe elements usually included in the concept of ethnicity, such as language, religion, degree of acculturation, and nation of origin. Overall, the field likely would need a minimal standard of reporting ethnicity and culture established by a consensus or editorial degree. When ethnicity might be conceived as a major influence or related to other psychological variables under study, then more elaborate conceptualizations would be needed. Psychologists might benefit from conceptualizations arising from controversies on ethnicity and culture in anthropology and sociology ( Jenkins, 1997 ; Malik, 1996 ; Solomos & Back, 1996 ).

Knowing the rates of consent/participation helps us to discern the representativeness of the sample from the overall population and to draw generalizable conclusions. A low rate of participation may or may not be a problem, depending on the circumstances of recruitment and the psychological variables under study. Too few research articles included this information, which is needed to form any consensus for acceptable ranges of participation.

The attrition rates were significantly under-reported. This information is important in determining the representativeness of the sample. Attrition may indicate whether the procedures biased the results, for example, because participants could not complete all aspects of an experiment or data gathering through fatigue, lack of interest, or alienation. Knowledge of attrition is also critical for evaluating clinical interventions. Essentially, differential attrition can bias results and invalidate research findings or mislead consumers of the research.

Reporting of parental permission/consent and child assent procedures as ethical information remains relatively low, despite the fact that two of the journals ( JPP and JCCP ) have instructions to include these procedures. Some information on how consent/assent procedures were handled may have been conveyed in a submission letter to the editor, and for two of the journals, authors of manuscripts accepted for publication sign an ethics compliance form indicating all procedures comply with the APA ethical code. In no way do we want to imply that these investigators were unethical in their research practices by omitting reports of consent and/or assent ( Roberts & Buckloh, 1995 ), and much of the research in the United States has been reviewed by institutional review boards. We can conclude only that the authors did not report this information. Certainly, in the case where journals report research with infants (e.g., CD ), child assent would be inappropriate. Even though avowal of proper use of consent is required to be published in these journals, reporting consent/assent procedures explicitly models ethical practices in research for fellow scientists and symbolizes adherence to ethical practices in research. Furthermore, perhaps more than the presence of a consent/assent form should be reported. Perhaps researchers should include relevant information such as the power differential between researcher and participant or the information the participant was actually given about the study.

Researchers experience the “judgment calls” of editors and reviewers (and usually make such calls themselves when roles are reversed) when manuscripts are reviewed for acceptance/rejection. Such judgments may include decisions about whether a participant sample is adequate from which to draw conclusions. Missing data about a sample, however, may not be caught in the editorial review and, as evidenced here, articles will be published without important pieces of information. Of course, including some information about the sample may affect submission/publication because aspects of the report sample seemingly fall short of some ill-defined criteria (e.g., about what constitutes a currently acceptable return rate of participation or about what is a necessary ethnic distribution of participants). At this time, there is currently not enough information in the literature on which to make this type of judgment.

In the interest of fairness in the publication process, but more important, for the advancement of the science in pediatric and child psychology, we suggest that all manuscripts be held to a standard of comprehensive reporting. If this happens, the field eventually will have a more complete picture from which to draw conclusions about psychological phenomena.

Commentary on the rates at which articles within a journal report the variables explored in this study is not meant to be a judgment of the quality of the research, journal, or editor. Although not reporting the variables considered in this study does restrict the reader's ability to evaluate articles, justification for these omissions may be reasonable. For example, the researchers may believe that some variables were not crucial to understanding their study. Nonetheless, if a standard of comprehensive reporting were used, then consumers of research would be able to judge for themselves the value of these variables. Furthermore, the journals' submission requirements or editorial review might not encourage the reporting of such variables. On the other hand, the researchers may believe that the editor's or the consumer's perception of the worth of their study may be negatively affected by reporting demographic characteristics that are not consistent with those found in the population of interest or by describing less than ideal methodological variables. These variables may then be submerged or obfuscated through global statements.

A couple of examples may illustrate best the deficiencies of reporting even basic information. One coded article on the psychometric development of a screening instrument for young children failed to report anything on the variables of gender, ethnicity, SES, location, identification/selection of the sample, consent rates, attrition, or reliability. This article passed the editorial review, but we question the use of the measure when the consumer has no knowledge about the group on which it was normed. An article on cross-cultural comparison of a widely used behavior problem checklist failed to indicate the ethnicity of the sample and provided no information on location, SES, attrition, and inclusion/exclusion criteria. As the results indicate, we could describe many articles in which critical information was lacking. Although these articles seem particularly egregious, there may be some benign omissions of information. However, an article author may not know how future researchers and clinicians might use the research findings since they will lack critical aspects of a study. Interpretation of findings is limited by this lack of information.

A primary consequence of research articles failing to report demographic and methodological variables is that consumers are not able to estimate whether the sample is representative of the population of interest or if procedures were adequate. As suggested by Betan et al. ( 1995 ), the more representative a sample is of the population being studied, the more likely the findings will generalize to the desired population. We were interested here in determining generally whether information on those characteristics is being reported; therefore, dichotomous coding of presence or absence of information was used in this study, not assessing the level of detail or meticulousness. Based on these overall results, greater precision could be employed in future work to consider the actual degree of representativeness for one or more of the variables in particular lines of research.

Based on our findings, like others before us, we suggest that journal editors and reviewers require, and researchers follow through by including, more demographic and methodological information in their articles. Describing this information in journal publications would enhance the scientific development of the field and the clinical applicability of the research. We hope that, in the future, the reporting of this demographic and methodological information will attain a 100% level for reporting the key variables needed for conclusions and interpretation in pediatric and child psychology research. The “gold standard” of reporting all these variables in all journal articles is a lofty goal and would necessitate changes in common writing and reviewing processes. As certain issues are highlighted in contemporary research, needs for reporting information may change over time. For example, the recent trend toward ensuring explicit accountability in ethical procedures provides pressure to report practices that might not have been the focus of such attention in the past. Similarly, issues of culture and ethnicity in research seem to assume greater emphasis more recently. Such a higher standard of reporting would require effort on the part of researchers to include such information and diligence on the part of reviewers and editors to ensure such information is included. This time and effort seems small in comparison to other resources invested in the research enterprise, yet it has such potential for advancing scientific rigor within research in pediatric and child psychology.

This article is based on a poster presentation at the Kansas Conference in Clinical Child Psychology, Lawrence, in October 1998.

American Psychological Association (APA) ( 1992 ). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychologist , 12 , 1597 -1611.

American Psychological Association (APA) ( 1994 ). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Bernal, G., & Enchautegui-de-Jesus, N. ( 1994 ). Latinos and Latinas in community psychology: A review of the literature. American Journal of Community Psychology , 22 , 531 -558.

Betan, E. J., Roberts, M. C., & McCluskey-Fawcett, K. ( 1995 ). Rates of participation for clinical child and pediatric psychology research: Issues in methodology. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology , 24 , 227 -235.

Bordens, K. S., & Abbott, B. B. ( 1996 ). Research design and methods: A process analysis (3rd ed.). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield.

Elkins, P. D., & Roberts, M. C. ( 1988 ). Journal of Pediatric Psychology: A content analysis of articles over its first 10 years. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 13 , 575 -594.

Graham, S. ( 1992 ). “Most of the subjects were White and middle class”: Trends in published research on African Americans in selected APA journals, 1970-1989. American Psychologist , 47 , 629 -639.

Hersen, M., & Bellack, A. S. ( 1984 ). Research in clinical psychology. In A. S. Bellack & M. Hersen (Eds.), Research methods in clinical psychology (pp. 100 -138). New York: Pergamon.

Iijima Hall, C. C. ( 1998 ). Cultural malpractice: The growing obsolescence of psychology with the changing U.S. population. American Psychologist , 52 , 642 -651.

Jenkins, R. ( 1997 ). Rethinking ethnicity: Arguments and explorations . London: Sage.

Malik, K. ( 1996 ). The meaning of race: Race, history and culture in Western society . New York: New York University Press.

Park, T. L., Adams, S. G., & Lynch, J. ( 1998 ). Sociodemographic factors in health psychology research: 12 years in review. Health Psychology , 17 , 381 -383.

Peterson, L. ( 1996 ). Establishing the study of development as a dynamic force in health psychology. Health Psychology , 15 , 155 -157.

Phares, V., & Compas, B. E. ( 1992 ). The role of fathers in child and adolescent psychopathology: Make room for daddy. Psychological Bulletin , 111 , 387 -412.

Ponterotto, J. G. ( 1988 ). Racial/ethnic minority research in the Journal of Counseling Psychology: A content analysis and methodological critique. Journal of Counseling Psychology , 35 , 410 -418.

Roberts, M. C. ( 1992 ). Vale dictum: An editor's view of the field of pediatric psychology and its journal. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 17 , 785 -805.

Roberts, M. C., & Buckloh, L. M. ( 1995 ). Five points and a lament about Range and Cotton's “Reports of assent and permission in research with children: Illustrations and suggestions.” Ethics & Behavior , 5 , 333 -344.

Roberts, M. C., McNeal, R. E., Randall, C. J., & Roberts, J. C. ( 1996 ). A necessary reemphasis on integrating explicative research with the pragmatics of pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 21 , 107 -114.

Solomos, J., & Back, L. ( 1996 ). Racism and society . New York: St. Martin's Press.

- child psychology

- ethnic group

- generalization (psychology)

- socioeconomic factors

- experimental attrition

Email alerts

More on this topic, related articles in pubmed, citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-735X

- Print ISSN 0146-8693

- Copyright © 2024 Society of Pediatric Psychology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing with Descriptive Statistics

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Usually there is no good way to write a statistic. It rarely sounds good, and often interrupts the structure or flow of your writing. Oftentimes the best way to write descriptive statistics is to be direct. If you are citing several statistics about the same topic, it may be best to include them all in the same paragraph or section.

The mean of exam two is 77.7. The median is 75, and the mode is 79. Exam two had a standard deviation of 11.6.

Overall the company had another excellent year. We shipped 14.3 tons of fertilizer for the year, and averaged 1.7 tons of fertilizer during the summer months. This is an increase over last year, where we shipped only 13.1 tons of fertilizer, and averaged only 1.4 tons during the summer months. (Standard deviations were as followed: this summer .3 tons, last summer .4 tons).

Some fields prefer to put means and standard deviations in parentheses like this:

If you have lots of statistics to report, you should strongly consider presenting them in tables or some other visual form. You would then highlight statistics of interest in your text, but would not report all of the statistics. See the section on statistics and visuals for more details.

If you have a data set that you are using (such as all the scores from an exam) it would be unusual to include all of the scores in a paper or article. One of the reasons to use statistics is to condense large amounts of information into more manageable chunks; presenting your entire data set defeats this purpose.

At the bare minimum, if you are presenting statistics on a data set, it should include the mean and probably the standard deviation. This is the minimum information needed to get an idea of what the distribution of your data set might look like. How much additional information you include is entirely up to you. In general, don't include information if it is irrelevant to your argument or purpose. If you include statistics that many of your readers would not understand, consider adding the statistics in a footnote or appendix that explains it in more detail.

- Dissertation

- PowerPoint Presentation

- Book Report/Review

- Research Proposal

- Math Problems

- Proofreading

- Movie Review

- Cover Letter Writing

- Personal Statement

- Nursing Paper

- Argumentative Essay

- Research Paper

- Discussion Board Post

How To Write A Statistics Research Paper?

Table of Contents

Naturally, all-encompassing information about the slightest details of the statistical paper writing cannot be stuffed into one guideline. Still, we will provide a glimpse of the basics of the stats research paper.

What is a stats research paper?

One of the main problems of stats academic research papers is that not all students understand what it is. Put it bluntly, it is an essay that provides an analysis of the gathered statistical data to induce the key points of a specified research issue. Thus, the author of the paper creates a construct of the topic by explaining the statistical data.

Writing a statistics research paper is quite challenging because the sources of data for statistical analysis are quite numerous. These are data mining, biostatistics, quality control, surveys, statistical modelling, etc.

Collecting data for the college research paper analysis is another headache. Research papers of this type call for the data taken from the most reliable and relevant sources because no indeterminate information is inadmissible here.

How to create the perfect statistics research paper example?

If you want to create the paper that can serve as a research paper writing example of well-written statistics research paper example, then here is a guideline that will help you to master this task.

Select the topic

Obviously, work can’t be written without a topic. Therefore, it is essential to come up with the theme that promises interesting statistics, and a possibility to gather enough data for the research. Access to the reliable sources of the research data is also a must.

If you are not confident about the availability of several sources concerning the chosen topic, you’d better choose something else.

Remember to jot down all the needed information for the proper referencing when you use a resource

Data collection

The duration of this stage depends on the number of data sources and the chosen methodology of the data collection. Mind that once you have chosen the method, you should stick to it. Naturally, it is essential to explain your choice of the methodology in your statistics research paper.

Outlining the paper

Creating a rough draft of the paper is your chance to save some time and nerves. Once you’ve done it, you get a clear picture of what to write about and what points should be worked through.

The intro section

This is, perhaps, the most important part of the paper. As this is the most scientific paper from all the papers you will have to write in your studies, it calls for the most logical and clear approach. Thus, your intro should consist of:

- Opening remarks about the field of the research.

- Credits to other researchers who worked on this theme.

- The scientific motivation for the new research .

- An explanation of why existing researches are not sufficient.

- The thesis statement , aka the core idea of the text.

The body of the text (research report, as they say in statistics)