What are Cultural Values? A Comprehensive Guide for All

Cultural values are the shared beliefs, norms, and practices that guide the behavior and attitudes of a group of people. They influence how people communicate, interact, and cooperate. They also shape how people view themselves, their identity, and their place in the world. Cultural values are not fixed or static; they can change over time and vary across different contexts and situations.

Sanju Pradeepa

You know cultural values shape so much of how we see the world, yet we rarely stop to ponder their meaning and influence. Cultural values are the beliefs and ideals that bind groups together and guide behavior. They influence everything from etiquette to ethics, holidays to habits. Understanding cultural values—both your own and those of others—is key to navigating our increasingly global society.

In this article, we’ll unpack the meaning of cultural values, explore how they form and spread, see how they differ around the world, and discuss why they matter in today’s world. By the end, you’ll have a deeper appreciation for the cultural values that make us who we are. So find a comfy seat, grab a cup of your favorite beverage, and let’s dive in.

Table of Contents

What are cultural values.

Cultural values are the principles and standards of a society that guide the way people think, feel, and behave. They shape our beliefs, attitudes, and actions.

Some key cultural values include:

- Individualism vs. collectivism: Individualist cultures value independence and personal achievement, while collectivist cultures emphasize group harmony and loyalty.

- Power Distance: This refers to how much inequality people accept in a culture. High power distance means hierarchy and unequal power distribution are accepted, while low power distance means people value equality and decentralization of power.

- Uncertainty Avoidance: Cultures with high uncertainty avoidance prefer rules, structure, and predictability. Those with low uncertainty avoidance are more tolerant of ambiguity and chaos.

- Masculinity vs. Femininity: Masculine cultures value competitiveness, ambition, and achievement, while feminine cultures emphasize quality of life, relationships, and work-life balance.

- Long-term vs. short-term Orientation: Long-term-oriented cultures value thrift, perseverance , and adaptation to changing circumstances. Short-term-oriented cultures emphasize tradition, personal stability, and fulfilling social obligations.

- Indulgence vs. Restraint: Indulgent cultures allow relatively free gratification of natural human drives related to enjoying life, while restrained cultures suppress gratification of needs and regulate it by means of strict social norms.

Cultural values shape how we see the world, interact with each other, and go about our daily lives. Understanding them leads to more effective cross-cultural communication and cooperation. What values does your culture hold dear?

The Origins and Evolution of Cultural Values

Cultural values shape societies in profound ways. They originate from a mix of influences: religion, language, ethnicity, history, and environment. As cultures evolve, values adapt to changing circumstances.

The role of religion

Many cultural values stem from religious beliefs. For example, Christian societies often emphasize kindness, forgiveness, and charity. Buddhist cultures promote harmony, patience, and humility and also value concepts like dharma (duty), karma (cause and effect), and ahimsa (non-violence).

Language and ethnicity

Shared language and ethnicity strengthen cultural connections and shape values within groups. Concepts like hospitality, family loyalty, or honor are commonly emphasized. Minority ethnic groups may highlight values that strengthen their identity.

Historical experiences

A culture’s history significantly impacts its values. Societies that have endured hardships like famine, war, or oppression frequently value qualities like perseverance , courage , or independence. Values can also be influenced by interactions with other groups as cultures blend together over time through trade, migration, or colonization.

Environmental factors

Geography and climate shape cultural values by necessitating certain qualities for survival. For example, cultures in harsh, resource-scarce environments often emphasize self-reliance , hard work, and thriftiness. Coastal societies frequently value concepts related to fishing, sailing, and trade. Agricultural communities tend to value harmony with the land and seasons.

Cultural values provide a shared sense of meaning , purpose, and identity within societies. While values originate from a culture’s unique circumstances, there are also universal values common to humanity—things like love, compassion, justice, and wisdom—that transcend cultural differences and unite us all.

Why Cultural Values Matter

Cultural values are the beliefs and ideals that shape how a group views themselves and the world around them. They govern behavior, shape attitudes, and influence important life decisions. Understanding cultural values—both your own and those of others—is key to effective communication and building meaningful relationships.

Shared Identity

Cultural values connect us to others in our group, creating a sense of shared identity. When we uphold the same values as our peers, it strengthens our bonds and reinforces our place within the community. However, this can also lead to an “us vs. them” mentality towards those with differing values. It’s important to balance cultural pride with openness to other perspectives.

Influence Outlook

The cultural values we absorb from an early age shape how we interpret the world around us . They act as a lens, filtering our perceptions and judgments. We tend to see those who share our values as “right” or “normal,” while perceiving those with opposing values as “strange” or even “wrong.” Recognizing this tendency in ourselves and others can help promote understanding.

Guide Behavior

Cultural values are not just abstract ideals. They directly impact how we live our lives and interact with others. The values we hold dear shape the choices we make, the way we communicate, and our unquestioned habits and routines. When values come into conflict, it can lead to misunderstandings and tensions. Navigating these differences with empathy, respect , and an open mind is key to overcoming cultural barriers.

In an increasingly connected world, understanding cultural values—both shared and diverse—is crucial. Appreciating both the uniting and distinguishing power of values allows us to build common ground while also honoring what makes each culture unique. By understanding why cultural values matter, we can work to promote inclusion, foster meaningful connections across perceived divides, and make progress together.

Examples of Common Cultural Values

Cultural values refer to the ideals and beliefs that shape how people in a society live and interact. They influence attitudes, priorities, and behaviors within a culture. Here are some of the most common cultural values found around the world:

Individualism vs. collectivism

Some cultures emphasize individualism, prioritizing individual goals and achievements. Others focus on collectivism, valuing group cohesion and harmony. Individualistic cultures like those in the US and Western Europe encourage uniqueness , while collectivist cultures in Asia, Africa, and Latin America stress community and social bonds.

Power Distance

This refers to how much inequality people accept in a culture. High-power distance cultures like China and India accept an unequal distribution of power, while low-power distance cultures such as Australia aim for equality and less hierarchy.

Uncertainty Avoidance

Cultures with high uncertainty avoidance, like Japan and Germany, value rules, order, and clear expectations. They prefer to avoid ambiguity and minimize risk. Cultures low in uncertainty avoidance, such as the US and UK, are more tolerant of uncertainty and open to unstructured ideas or situations.

Masculinity vs. Femininity

Masculine cultures value competitiveness , achievement, and material success. Feminine cultures emphasize quality of life, caring for others, and social relationships. Japan and Austria rank high in masculinity, while Scandinavian countries like Sweden are more feminine.

Long-term vs. short-term orientation

Long-term-oriented cultures such as China and Japan focus on perseverance, thrift, and future rewards. Short-term-oriented cultures like the US and France value immediate gratification, consumption, and quick results.

Cultural values shape how we interpret the world around us and interact with each other. Recognizing these values in yourself and others can help promote cross-cultural understanding and bring greater harmony between people from diverse backgrounds.

How Cultural Values Shape Society

Cultural values are the ideals and beliefs within a society that shape behaviors and social norms. They influence how people think, communicate, and interact with one another in their daily lives. Cultural values also help determine what is considered right or wrong, good or bad, and important or unimportant in a society.

Tradition and Change

Cultural values often represent a balance between tradition and change. Societies value tradition by passing down beliefs and practices between generations. However, as societies evolve, cultural values also adapt to fit the times. Older generations may cling to more traditional values, while younger generations push for progressive changes. Finding the right balance between honoring tradition and embracing change is key to the growth and prosperity of any culture.

Morality and ethics

Cultural values shape a society’s morality and sense of ethics. They determine views on fundamental issues like life and death, family and relationships, and justice and human rights. Societies grapple with moral questions of what constitutes virtuous behavior and how to achieve “the good life.” Cultural values provide a moral compass for navigating these complex questions.

Cooperation and conflict

Cultural values influence how people in a society interact and relate to one another. Values like individualism versus communalism, competition versus cooperation, and harmony versus confrontation shape the nature of social relationships. Societies that emphasize cooperation and communalism tend to have more collectivist cultures , while those that emphasize individualism and competition tend to have more individualistic cultures. A society’s orientation towards cooperation or conflict impacts social cohesion and quality of life.

In summary, cultural values are the DNA of society. They shape how people think and act, determine morality and ethics, influence tradition and change, and affect cooperation and conflict. Cultural values reflect what really matters in a society, so understanding them is key to understanding the society itself.

Cultural Values Across Different Cultures

Cultural values represent the collective beliefs and ideals that shape a society. They are passed down through generations and influence how people think and behave. Cultural values can vary widely between different groups of people.

Individualism versus collectivism

Some cultures promote individualism, emphasizing personal achievement and independence. Others are more collectivist, focusing on group harmony and loyalty.

- Individualist cultures like those in the U.S. and Western Europe value personal freedom and achievement. People see themselves as autonomous individuals.

- Collective cultures in Asia, Africa, and South America value community over the individual. People see themselves as interdependent and define themselves by group membership. Loyalty to family and community is key.

This refers to how cultures view power hierarchies and inequality. High power distance means people accept an unequal distribution of power as normal. Low power distance means people value equality and challenges to authority.

- High power distance: Cultures in the Middle East, Asia, and Latin America accept hierarchy and authority. People respect age, status, and titles.

- Low power distance: Western cultures question authority and value egalitarianism. People see themselves as equals, regardless of age, status, or gender.

This refers to how cultures view uncertainty and ambiguity . High uncertainty avoidance means people prefer order, rules, and security. Low uncertainty avoidance means greater tolerance for ambiguity and risk.

- High uncertainty avoidance: Cultures in East Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America prefer structure, rules, and traditions. People seek security and conformity.

- Low uncertainty avoidance: U.S. and Western European cultures are comfortable with ambiguity and risk. People value independence, creativity, and openness to change.

In summary, cultural values shape how people think, communicate, and behave in profound ways. Recognizing these differences can help promote cross-cultural understanding and bring people together, despite their diverse beliefs and worldviews.

The Impact of Cultural Values on Business

Cultural values shape how businesses operate and interact with customers in society. Understanding the cultural values of your target market is key to success.

Communication

How people communicate varies across cultures. Some prefer direct, blunt communication, while others rely more on context and reading between the lines. When marketing or providing customer service, adapt your communication style to match your audience. For indirect cultures, focus on building relationships and trust. For direct cultures, get straight to the point.

Time Orientation

Cultures also differ in their view of time. Some see time as rigid and unchanging, while others see it as fluid. In monochronic cultures like Germany or the US, people value punctuality and efficiency . In polychronic cultures like Brazil or Egypt, flexibility and relationships are more important. Accommodate these differences when scheduling meetings or deadlines.

Some cultures emphasize individual goals and achievements (individualism), while others focus on group harmony and loyalty (collectivism). In individualist cultures, highlight personal benefits and freedom of choice in your messaging. In collectivist cultures, the focus is on the benefits to families, communities, and society.

Risk Tolerance

The level of uncertainty and risk deemed acceptable varies across cultures. Some cultures, like the US, tend to be more risk-tolerant, while others, like Japan, are more risk-averse. When introducing new products or services, determine the risk profile of your target market and adjust accordingly. In risk-averse cultures, the focus is on stability, security, and risk mitigation. In risk-tolerant cultures, highlight opportunities for reward and status.

Understanding cultural values provides insight into your target customers and how to best serve them. Adapt your business practices, marketing, and customer service to align with the values of your audience. Respecting cultural differences will lead to greater success in today’s global marketplace.

Promoting cross-cultural understanding

To truly understand different cultures, you need to recognize and respect their values. Cultural values are the ideals and beliefs that shape how a group thinks and acts. Promoting cross-cultural understanding means appreciating how values differ between societies.

Openness and Curiosity

The first step is developing an open and curious mindset . Try to understand cultural values from an insider’s perspective, not an outsider looking in. Ask questions, do research, and seek to learn why certain values are meaningful to that group. For example, many Western cultures value independence, while other societies put more emphasis on interdependence and community. Neither is right nor wrong; they are just different.

Recognize Differences

Don’t assume all cultures share your values. What you consider normal or ethical may be viewed very differently elsewhere. For instance:

- Views on family and gender roles can vary widely between cultures.

- Concepts of personal space and privacy are culturally dependent.

- The importance placed on traits like assertiveness , competitiveness, and ambition differs across societies.

Appreciating these differences will help you avoid insensitive or disrespectful behavior. Make an effort to understand values in the proper cultural context.

Find common ground.

While values may differ between groups, all cultures share some universal values like compassion, kindness , and fairness. Focus on the values you have in common rather than those that divide you. Look for opportunities to build connections and foster mutual understanding. Engage in open and honest dialog to promote cooperation and trust between cultures.

Promoting cross-cultural understanding is a lifelong process that requires patience, empathy, and a willingness to step outside your comfort zone . But by making the effort to learn about different cultural values, you can help create a more inclusive society where diversity is celebrated rather than feared. Understanding each other’s differences is the first step to overcoming them.

How to Uphold and Strengthen Cultural Values

To uphold and strengthen cultural values within a society, community, or organization, there are several effective strategies you can implement:

Promote understanding

Educate others about the origins and meaning behind your cultural values. Explain how they shape attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. Increase insight into why certain traditions, rituals, or practices are important. The more people comprehend the significance, the more they will appreciate and support the values.

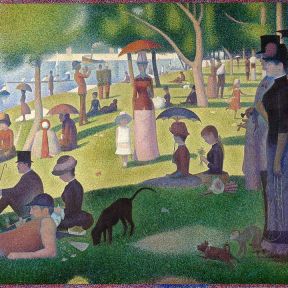

Honor traditions

Continue established customs, ceremonies, and celebrations that highlight meaningful cultural values. Participate in cultural events and invite others to join in. Make cultural values visible through symbolic representations like flags, statues, paintings, or clothing.

Share stories

Pass down cultural values through narratives, folklore, music, or art. Stories are a powerful way to convey morals, lessons, and wisdom to future generations. Share stories of role models or key historical figures who embodied important cultural values.

Set an example.

Model the behaviors and attitudes you want to see in others. Practice the cultural values in your own words, actions, and decisions. Be a mentor for those who want to strengthen their connection to the culture. Your passion and commitment will inspire others.

Reward and recognize

Provide positive reinforcement by acknowledging those who demonstrate cultural values. Thank them for their efforts and contributions. Highlight their achievements within the community. Recognition motivates people to continue promoting cultural values.

Strengthening cultural values requires ongoing dedication and teamwork. But by making the values a central part of individual and community identity, you ensure they endure and remain a source of meaning for generations to come. Focus on understanding, tradition, storytelling, leading by example, and positive reinforcement. Together, these strategies will keep cultural values alive and thriving.

Attitude and Mindset: Intersection, Importance & Difference

Threats to cultural values in today’s world.

Globalization and access to technology have exposed most of the world’s cultures to outside influences, which can threaten traditional cultural values. Some of the biggest threats to cultural values today include:

Cultural appropriation

When aspects of a minority culture are adopted by members of the dominant culture, it can feel disrespectful or like the meaning and importance are lost. Cultural appropriation of clothing, hairstyles, music, or religious practices can damage or dilute cultural values when done without proper understanding, respect, or permission.

Spread of misinformation

The internet and social media have enabled the rapid spread of both information and misinformation. False or misleading information about cultural beliefs , practices, or histories can undermine and distort cultural values. It’s important we educate ourselves about cultures different from our own to avoid perpetuating stereotypes or spreading misinformation, even unintentionally.

Globalization of media.

Access to media from around the world through streaming services and the internet exposes us to cultures different from our own. While cultural exchange can be positive, the globalization of media does threaten local cultural values by promoting more western or American ideologies. Local media, arts, music, and entertainment industries struggle to compete, and traditions can be lost.

While tourism promotes cultural appreciation and economic benefits, uncontrolled tourism can be damaging. Disrespectful tourists who treat cultural sites and practices as spectacles rather than with reverence can degrade sacred values. Overtourism leads to overcrowding, environmental damage, and a loss of authenticity. Regulations and sustainable tourism practices are needed to protect cultural values from the threats of tourism.

Overall, protecting cultural values in today’s connected world requires education, open-mindedness, cultural sensitivity, and a willingness to listen and understand each other, even when we don’t see eye to eye. Promoting inclusiveness, fighting misinformation, and encouraging cultural diversity will help ensure traditional values survive and thrive. But change is inevitable, and cultural values will continue to evolve and adapt to the modern world, as they always have.

Looking Ahead: The Future of Cultural Values in a Globalized World

Cultural values shape societies and bring people together, but in today’s globalized world, cultural identities are evolving. As cultures blend and ideas spread, cultural values are adapting to reflect more inclusive and progressive ways of thinking.

Looking ahead, cultural values will likely drift in a more humanitarian direction. There will be a greater emphasis on human rights, empathy, and mutual understanding between groups. Discrimination based on attributes like ethnicity, gender, sensual orientation, and religion will continue to decline. People will value diversity and push for equal treatment of all individuals.

Interconnectedness will be highly prized. Things that divide us, like nationalism and tribalism, will be discouraged in favor of a shared human identity. There will be more appreciation for how our fates are bound together in an increasingly global community. Cooperation and collaboration across borders will be seen as vital to solving problems that affect us all.

Environmentalism will likely feature more prominently in cultural values. As the impacts of climate change intensify, cultures will promote more sustainable ways of living that reduce humanity’s ecological footprint. Protecting biodiversity and natural habitats will be seen as keys to ensuring a livable planet for future generations. An ethic of environmental stewardship will spread.

Even as cultures blend, cultural traditions will still be honored. While globalization exposes us to outside influences, people will continue to value the histories, languages, arts, and other hallmarks that make their cultural identities unique. The trick will be balancing cultural preservation with a spirit of openness, inclusion, and shared progress.

The future of cultural values looks bright if we make the well-being of all people and our planet central to how cultures evolve in the decades ahead. By embracing diversity, championing human rights, and protecting our environment, cultural values can help create a more just, sustainable, and prosperous world for all.

You now have a sense of what cultural values are and how deeply they shape society. But cultural values are complex; they evolve over time and differ across groups. The values you hold dear say a lot about your identity and experiences. At their best, cultural values bind communities together and give life deeper meaning. At their worst, they can promote close-mindedness and conflict with others.

Understanding cultural values—both your own and those of others—is so important in today’s global world. So keep exploring, questioning assumptions, and seeking to understand people who are different. That’s the only way we’ll build a future filled with more connection and less division. Cultural values matter, so make the effort to understand them.

- Cultural exchange: Embracing Cultural Exchange in a Globalized World by FasterCapital

- 38 Cultural Values Examples By Pernilla Stammler Jaliff (MSSc)

- Understanding How Culture Impacts Local Business Practices

- Behav Sci (Basel) , Individualism, Collectivism, and Allocation Behavior: Evidence from the Ultimatum Game and Dictator Game Jingjing Jiao , – doi: 10.3390/bs13020169 from An official website of the United States government.

- Cross-Cultural Communication and Cultural Understanding Written by MasterClass

- PhD Assoc. Prof. Natalia Bogoliubova, PhD Assoc. Prof. Julia Nikolaev, – Cultural Ties in a Globalization World: The Threats and Challenge (PDF)

Let’s boost your self-growth with Believe in Mind.

Interested in self-reflection tips, learning hacks, and knowing ways to calm down your mind? We offer you the best content which you have been looking for.

Follow Me on

You May Like Also

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

APPLY NOW --> REQUEST INFO

Apply Today

Ready to apply to Penn LPS Online? Apply Now

Learn more about Penn LPS Online

Request More Information

Why cross-cultural communication is important—and how to practice it effectively

Many bachelor’s degree programs require students to complete a few courses in a foreign language; learning another language can be a vital skill in many careers as well as a way to gain broader perspective on culture and global connections. But language instruction often requires an immersive and intensive classroom schedule that isn’t well-suited to part-time study or the flexible online platform offered by Penn LPS Online’s Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences (BAAS) degree.

“When we were thinking about what the new Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences would look like, we thought that the residential language program didn’t work as well to address the needs of a very diverse student body which might not even be located here in Philadelphia,” recalls Dr. Christina Frei, Academic Director of the Penn Language Center . “We needed to figure out a way to still have a discussion about language in the degree. I proposed that we offer a course that focuses on the role that language plays in intercultural communication.”

The resulting course is one of the foundational requirements of the BAAS degree. The purpose of ICOM 100: Intercultural Communication is to develop effective communication skills and cultural understanding globally as well as within diverse communities. While the Intercultural Communication course does not replace the intensive language instruction necessary to speak and read in another language, it does develop the intercultural perspective, which is vital to learning a new language and engaging meaningfully with people across language and cultural differences. “Language is embedded and highly connected to culture. One cannot understand language outside of cultural or vice versa,” says Frei. “I designed the course to pique students' interest in the power of language and the complexities of language and culture.”

What is intercultural communication?

Intercultural communication has become a key concept in language instruction, but only recently. “In the last 20 years—and particularly in the last 10 years—we really understand more about the role that language plays in identity,” says Frei. In her many roles at Penn, Frei ensures that language and cultural studies meet the standards of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL), which has started to center identity and culture. At the Penn Language Center, which houses language instruction that falls outside of established foreign language departments such as the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures (for which Frei is the Undergraduate Chair), Frei oversees course offerings and learning opportunities in languages spoken in Africa and South Asia as well as American Sign Language and even language instruction for professional use (such as Spanish for health professionals and Chinese for business). Frei is also the Executive Director of Language Instruction for the School of Arts and Sciences, and in that capacity, she oversees language education across Penn to ensure professional standards are met and a cohesive pedagogical approach is achieved. “Over the last 10 years, the best practices have changed, and ACTFL really has begun to look towards intercultural communication,” says Frei.

To understand what intercultural communication is, it helps to understand culture as something active and pervasive. “Culture is a verb,” says Frei, citing one of the assigned texts from her course: Intercultural Communication: A Critical Introduction by Ingrid Piller. “You’re doing culture all the time,” explains Frei. “In order to become aware of what culture actually is, you have to really develop a critical eye to look at your perceptions and your surroundings.” Doing culture can include ways of speaking and acting but also thoughts and beliefs you’re not even aware of—although you’re most likely to become aware of how you “do culture” when you interact with someone who “does culture” differently. Intercultural communication encompasses a vast array of verbal and nonverbal interactions that may take place on such occasions: learning a new language or visiting another country are common examples but joining a new workplace or participating in a community organization with members of diverse backgrounds can also engage intercultural communication skills.

“If you want to do culture interculturally, you cannot do it by exclusion,” adds Frei. “Inclusivity, to me, is the new word for being truly multicultural, to really be open-minded and understanding about the differences that human beings have in their lives, their languages, and in their beliefs and cultural practices.”

The importance of intercultural communication

Intercultural communication plays a pivotal role in our increasingly globalized world, where people from various cultural backgrounds interact regularly. It is of paramount importance as it facilitates understanding and collaboration among individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds, helping to break down the walls of stereotypes and assumptions that can hinder effective communication. In a world where cultural diversity is the norm, effective intercultural communication fosters empathy, reduces misunderstandings arising from differing cultural norms, and promotes tolerance. By embracing the nuances of different cultures, we bridge divides and harness the rich tapestry of perspectives, ideas, and talents that diverse populations bring to the table. It is a cornerstone for successful diplomacy, international business, and peaceful coexistence. Intercultural communication promotes unity in diversity, enhancing our collective capacity to address global challenges and build a more inclusive and harmonious global community.

How do you develop intercultural understanding in the classroom?

To provide a broad range of opportunities for students to analyze examples of “doing culture,” the Intercultural Communication course incorporates an array of readings, videos, and websites to explore different ways of expressing and interpreting culture through language. There are recorded interviews with scholars and activists who have compelling perspectives on how to “do culture” as a member of a minority population: a Lakota historian who protested the construction of a pipeline in the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, an applied linguist involved in a social impact project with a Bangladeshi community in Philadelphia, and the director of the American Sign Language program at Penn who shares insight about language and culture within the deaf community. In addition to the Intercultural Communication textbook and assorted reading assignments, the students read The Enigma of Arrival , V.S. Naipaul’s autobiographical novel about his journey from the island of Trinidad to the countryside of England. “It’s a fabulous book that I hope the students enjoy reading,” says Frei. “It’s one person’s story about coming to a new place and doing culture from the outside, so to speak. There is a lot of self-observation and self-reflectivity about how, as he is doing culture, he begins to understand himself and the place differently.”

Students analyze and reflect on these cultural artifacts in class discussions and written assignments. “The workshops that I usually offer here at Penn and the courses I teach have a communicative approach with a lot of reflection, so that's part of the Intercultural Communication course as well,” says Frei. “We do tons of personal reflection because it’s important to know what your own prejudices are, what your own value system is, what your own sense-making is, and what your own analysis is, and what your own observations are.” In particular, students are asked to step back and observe how they communicate with others, from workplace and religious communities to interactions with friends and family to brief encounters at the supermarket. “It's almost like an anthropological journal, if you wish,” says Frei. ”It builds a particular kind of sensitivity to observe without judgment what you’re thinking and how you react, which helps you to be inclusive, to have empathy, and to understand the people you engage with.”

Though the course is asynchronous, Frei says, discussion boards and reflective practices bring students into the discussion and require them to communicate clearly and thoughtfully with one another. “Perhaps that’s the beauty of an online course,” says Frei. “You really do need to listen or read and pay attention to what your peers are saying. I think they really will gain an understanding of what intercultural communication means to each of them.”

“The students are actually creating the knowledge of the course,” she adds. “I'm giving them a tool kit, but what they actually do with it is up to them—and that’s very exciting.”

Tips for effective cross-cultural communication

To succeed in the course, Frei emphasizes that students need to pace themselves and schedule themselves plenty of time to think, reflect, and feel as they go through the coursework. “These are not just assignments where you can just check a box and you're done. These are thinking pieces,” says Frei. “Students need to really make sure to put some time aside because they have to think in order to do the work. They need to allow themselves to be open-minded about themselves and perhaps, in their own thinking, surprise themselves.”

Time management gives students the space needed to develop their practice of reflection, which is an important skill for communication in any context. For Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences students, Frei notes, reflection is built-in throughout the entire degree, culminating in the ePortfolio degree requirement . “It makes complete sense,” she says. “The ePortfolio is not just a curated collection of your best work. It’s a curated collection that you thought about and where you reflected on your benchmarks, your rubrics, your qualifiers for your best work.” Likewise, reflection is a vital step in thinking about culture and language.

But to Frei, reflection is deeply entwined with the concept of self-care. “Ask yourself: How can I be healthy emotionally, intellectually, physically? How does that all come into the mix?” says Frei. In her German classes, Frei will often ask students to complete a self-assessment of their reading practices: where do they typically sit, how focused do they usually feel, what kinds of emotions to do they experience and when. By being attuned to those details, says Frei, a student can make choices that will help them both enjoy and absorb more in their reading. Likewise, when it comes to language and culture, “self-care is key,” she says. “Self-reflection and understanding your own practices, your own cultural beliefs, your own cultural practices and perspectives will help you to sensitize you.”

“This is a course that shares knowledge through books and instructional design. You’ll gain insights into minority discourses and you’ll learn about communication and language. Those skills are transferable to other courses,” says Frei. “But it’s also a place where you can get to know yourself a little bit more. I think that could be really helpful.”

For more information about this unique online degree and its requirements, visit the Penn LPS Online feature “What is a Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences degree? ”

Dive deeper into all the opportunities available through Penn LPS Online by visiting our homepage .

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Cross-cultural differences and similarities in human value instantiation.

- 1 School of Psychology, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom

- 2 Department of Psychology, University of Bath, Bath, United Kingdom

- 3 Departamento de Psicologia, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande, Brazil

- 4 Department of Psychology, University of Derby, Derby, United Kingdom

- 5 Departamento de Psicologia, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Joao Pessoa, Brazil

- 6 Department of Psychology, Karnatak University, Dharwad, India

Previous research found that the within-country variability of human values (e.g., equality and helpfulness) clearly outweighs between-country variability. Across three countries (Brazil, India, and the United Kingdom), the present research tested in student samples whether between-nation differences reside more in the behaviors used to concretely instantiate (i.e., exemplify or understand) values than in their importance as abstract ideals. In Study 1 ( N = 630), we found several meaningful between-country differences in the behaviors that were used to concretely instantiate values, alongside high within-country variability. In Study 2 ( N = 677), we found that participants were able to match instantiations back to the values from which they were derived, even if the behavior instantiations were spontaneously produced only by participants from another country or were created by us. Together, these results support the hypothesis that people in different nations can differ in the behaviors that are seen as typical as instantiations of values, while holding similar ideas about the abstract meaning of the values and their importance.

Introduction

In recent years, many Western countries have accepted once again tens or even hundreds of thousands of immigrants into their country. This has sparked widespread discussions of how well immigrants are able to acculturate (e.g., The Economist, 2016 ). For example, a recent Canadian survey found that three quarters of Ontarians feel that Muslim immigrants have fundamentally different values than themselves ( Keung, 2016 ). This feeling is in contrast to large international surveys of human values in which it was found that people from more than 55 nations are consistent in valuing some values more and others less ( Schwartz and Bardi, 2001 ). How then is it the case that people from different countries appear to be so different? The present research follows up this train of thought by testing whether people in different nations differ in the behaviors that are seen as typical instantiations (i.e., examples) of values, while holding similar ideas about the abstract meaning of the values and their importance.

Conceptualizing Values and Value Differences

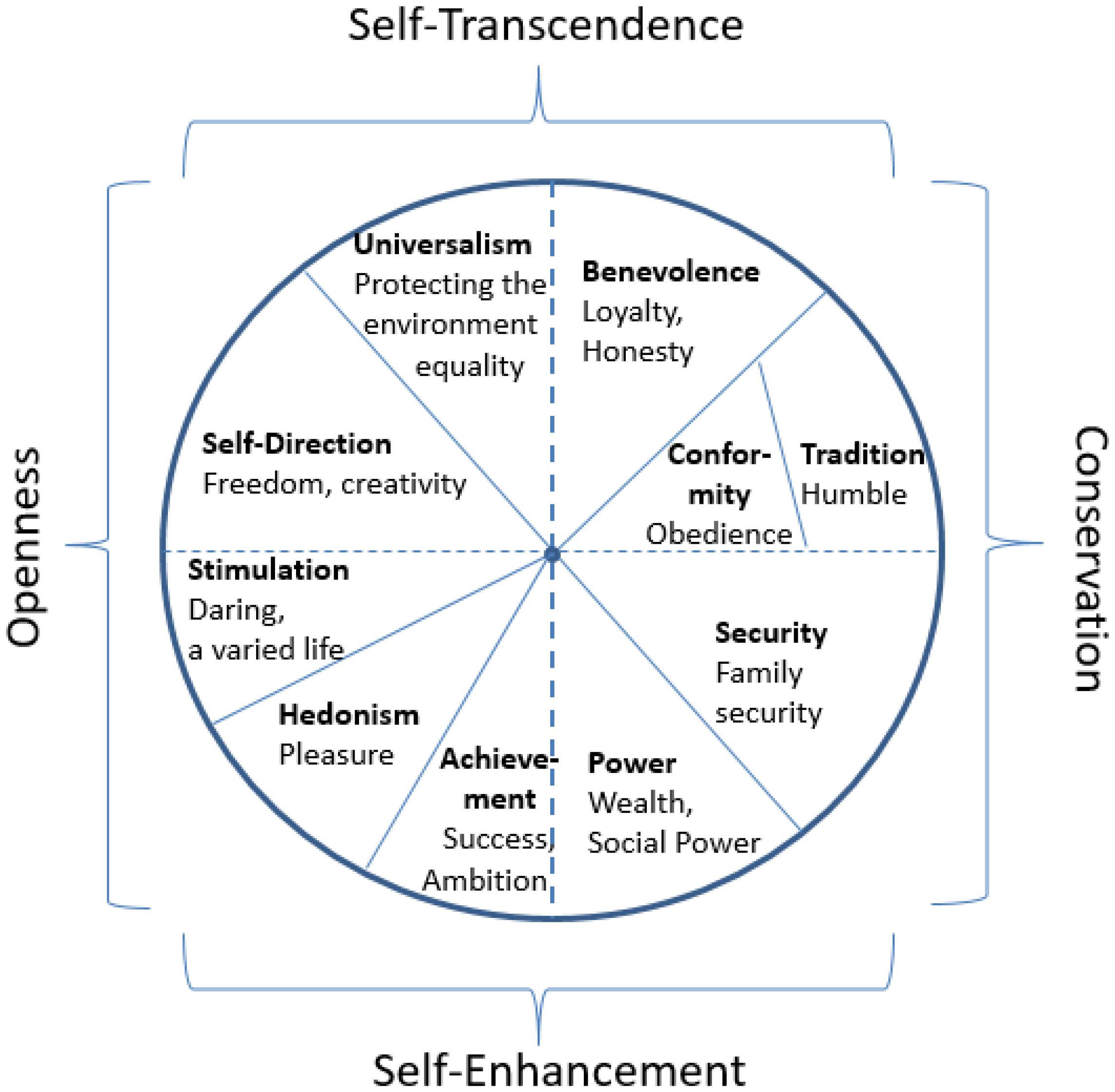

Values, abstract guiding principles, have gained a lot of attention, not just within psychology, but also in neighboring fields such as sociology, economics, philosophy, and political science ( Schwartz, 1992 ; Gouveia, 2013 ; Maio, 2016 ). In the last three decades, researchers have asked people to rate diverse values in terms of their importance as guiding principles in their lives. Analyses of these ratings have taught us that the structure of human values is very similar across more than 80 countries ( Schwartz, 1992 ; Bilsky et al., 2011 ; Schwartz et al., 2012 ). That is, the same values have been grouped together in most countries, resulting in the view that values within a cluster are motivationally compatible. More specifically, in the predominant value model ( Schwartz, 1992 ) 10 value types are distinguished: power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, and security. The 10 value types can be combined into four higher order value types, which form the endpoints of two orthogonal dimensions: openness values vs. conservation values, and self-transcendence values vs. self-enhancement values (see Figure 1 ). Adjacent value types are motivationally compatible and hence positively correlated, whereas opposing value types are expected to be motivationally incompatible and negatively related.

FIGURE 1. Schwartz’ (1992) circumplex model of human values displaying 10 value types (bold font) and examples of values in each type (normal font) along two dimensions.

In addition, there is similarity in value hierarchies ( Schwartz and Bardi, 2001 ). Benevolence, universalism, and self-direction values are regarded as the most important across more than 50 countries, whereas tradition and power are valued least. Country of origin explains on average only 2–12% of inter-individual variance ( Fischer and Schwartz, 2011 ). Thus, there is high consensus on value priorities across countries.

Given these findings, how is it that people often persist in believing that people from different countries hold different values? Some factors are likely to be motivational: abundant evidence points to the roles of realistic group conflict ( Bobo, 1983 ), social identification ( Tajfel and Turner, 1986 ), symbolic racism ( Kinder and Sears, 1981 ), and various biases (e.g., symbolic self-completion, Gollwitzer et al., 1982 , or system justification, Jost and Banaji, 1994 ) that can lead us to feel that our own group is superior to other groups in numerous characteristics, including values. Other factors are cognitive: social learning ( Bandura et al., 1961 ) and stereotyping processes (e.g., illusory correlation, Hamilton and Rose, 1980 ) may lead us to encode other groups’ characteristics in ways that magnify the differences between groups. More relevant to the present research, however, is the nature of the values concept itself. Specifically, as abstract ideals, values subsume a wide range of behaviors as exemplars of the concepts. People may perceive differences between social groups because of the differences between groups in the specific behaviors that are seen as exemplars of different values, even if other behaviors that are exemplars of the values do not differ. Thus, by thinking about groups in terms of concrete instances, differences may be stronger than similarities.

In other words, people in different social groups may endorse the same values but associate different behaviors with them ( Maio, 2010 ). For example, the value of equality may be linked to comparisons between men and women in countries where gender equality is promoted, but not in countries where gender equality is not part of the political agenda. Indeed, Turkish people value equality as much as people in other European countries, but endorse gender equality less strongly ( Hanel et al., 2017 ). Furthermore, equality on an abstract level and gender equality were slightly negatively associated in Turkey, but positively in most other European countries.

These differences are not as evident if “meaning” is understood only as abstract conceptualizations of values, which tend to be vague in nature. The concrete actions that people link to values are value instantiations ( Hanel et al., 2017 ). The concept of instantiations originates from cognitive psychology. Instantiating a rule or concept involves applying it to a concrete exemplar ( Anderson et al., 1976 ). ‘Instantiation’ thus refers to a particular realization or instance of an abstraction or to the process of producing such an instance. Instantiation is therefore based on the relationship between general and specific, as in different levels of a conceptual hierarchy. For instance, football is an instantiation of the category sport , fork is an instantiation of cutlery , and pear is an instantiation of fruits (see Hanel et al., 2017 , for a more extensive overview).

Maio (2010) suggested that values can be modeled as mental representations on three levels. The first level is the system level, on which values are connected to each other, as in Schwartz’s (1992) model. The second level is the level of specific abstract values (e.g., equality and wealth), which comprise the importance that people attach to the abstract concepts. Finally, the third level is the instantiation level, which includes specific situations, issues, and behaviors relevant to the values.

Similar to instantiations of animals and other categories, research has found that value instantiations can vary in typicality, with important ramifications. For example, Maio et al. (2009) found that contemplation of typical, concrete examples of a value increased subsequent value-related behavior more than did contemplation of atypical examples. That is, the act of thinking about a typical, concrete example of a value led people to be more likely to spontaneously apply the value in a subsequent situation. This finding illustrates the importance of finding typical instantiations over a range of values (perhaps due to their greater familiarity or fit with the ideal or central tendency), which is another aim of Study 1. Based on this finding, Maio (2010) indicated that value instantiations could operate in different ways. More specifically, concrete value instantiations “could (1) affect a strength-related property of the abstract value itself (e.g., value certainty), (2) act as metaphors that we apply to subsequent situations through analogical reasoning, or (3) affect our perceptual readiness to detect the value in subsequent situations” ( Maio, 2010 , p. 27).

The Present Studies

In Study 1 we used a qualitative approach to measure (behavior) instantiations of 23 values from Schwartz’s (1992) value model, while comparing them in a systematic way across three countries. To help us examine the value instantiations, participants were asked to report situations in which they considered a value to be relevant, including the people in this situation and their actions . This method was an extension of previous concept-mapping approaches used in the study of attitudes (e.g., Lord et al., 1994 ), creativity research ( Sternberg, 1985 ), and values ( Maio et al., 2009 ).

We expected that people in different countries would differ in their concrete (behavior) instantiations of values, because we assumed that personal experiences and the socio-cultural environment exert a strong influence at the concrete level ( Morris, 2014 ; Hanel et al., 2017 ). To test this hypothesis, we collected data from regions of three countries: north-east Brazil, south-west India, and south Wales. These countries differ on various dimensions. In terms of years of schooling, GNP, and life expectancy ( United Nations Developmental Programme, 2014 ), India is the least developed of the three countries, and the United Kingdom is the most developed. Brazil and India are perceived to be much more corrupt than the United Kingdom ( Transparency International, 2014 ), and the homicide rate in Brazil is 25 times higher than in the United Kingdom and almost eight times higher than in India ( United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2014 ). Thus, corruption may be more spontaneously associated with equality as a value and protections against physical violence may be more strongly associated with family security in Brazil than in the United Kingdom. There are also marked differences in climate and natural resources. These differences may well be reflected in differences in value instantiation between the nations. For example, water conservation may be more spontaneously associated with the value of protecting the environment in places where water is scarce (e.g., north-eastern Brazil) than where it is abundant (e.g., most of the United Kingdom). Similarly, waste recycling may be more spontaneously associated with protecting the environment in places where recycling is possible and promoted than where it is not possible and/or not promoted. This difference could emerge even if the absolute or relative importance of the value protecting the environment – a key value relevant to these behaviors – is the same in both types of location. Furthermore, such differences may emerge even if people in both regions recognize the behaviors as potential ways to promote the environment (see Study 2). That is, people in both types of location may recognize that water conservation and recycling protect the environment, but they may simply differ in how strongly they spontaneously associate these behaviors with the value in day-to-day life.

With the results of this study in hand, the next substantive issue was whether the (behavior) instantiations that were most frequent in each nation would fit the value as it is conceived in the other nations. That is, even if we focus on the instantiations that appeared only in one nation but not in another, could the instantiations be matched to values (i.e., ‘back-translated’). Study 2 examined the degree to which instantiations could be recognized as belonging to the values from which they originated. For example, would participants recognize recycling as an example of protecting the environment and keeping secrets as an example of loyalty to an equal extent across countries? This step was important because it would reveal the conceptual relevance of the instantiations to the values. In other words, people should be able to recognize the value that a behavioral instantiation promotes, even if the instantiation is atypical for the participant’s own region. This matching would show that the instantiations vary merely in their spontaneous natural activation by values, but not in their conceptual relevance to values. Both studies were approved by the ethics committee of the School of Psychology, Cardiff University. That means that informed consent was obtained by the participants, which included that their participation was voluntarily, they could withdraw at any time without providing a reason, and that the information participants provided would be held anonymously. At the end of each study, participants were fully debriefed. The English versions of the questionnaires used in both studies, along with the two datasets, can be found on https://osf.io/s5vwa/?view_only=6803c67e69af48278640fbcbb2a7b3ea .

Study 1: Exploring Value Instantiations

This study aimed to find typical value instantiations in Brazil, India, and the United Kingdom and estimate the degree of similarity between them. This aim was achieved using a paradigm that has been used to examine exemplars of natural categories (e.g., Collins and Quillian, 1969 ), as well as in later research on typicality effects ( Fehr and Russell, 1984 ; Lord et al., 1994 ; Maio et al., 2009 ) and on the strength of associations between categories and their members ( Fazio et al., 2000 ). For example, Maio et al. (2009 , p. 601) asked participants “to list situations in which they considered equality to be important”. A different approach was chosen by Lord et al. (1994) , who asked their participants to complete attitude concept maps on capital punishment and social welfare in order to identify how participants refer to people who are affected by each of those social policies. Specifically, participants were asked to construct a concept map by adding nodes to a central node that stated “capital punishment” or “social welfare,” and the added nodes were generated in response to questions asking “what,” “where,” “when,” “who,” “why,” and “how”.

Following those examples, in Study 1 participants were asked to list situations in which they considered a value to be important and to include people and their actions. These responses were then used to create a conceptual map representing values and value instantiations for each country. These maps were similar to those created by Lord et al. (1994 , p. 661), except that our method maps values, rather than natural concepts (see the 23 figures in the Supplementary Materials for such ‘value maps,’ one for each of the 23 value investigated in this study).

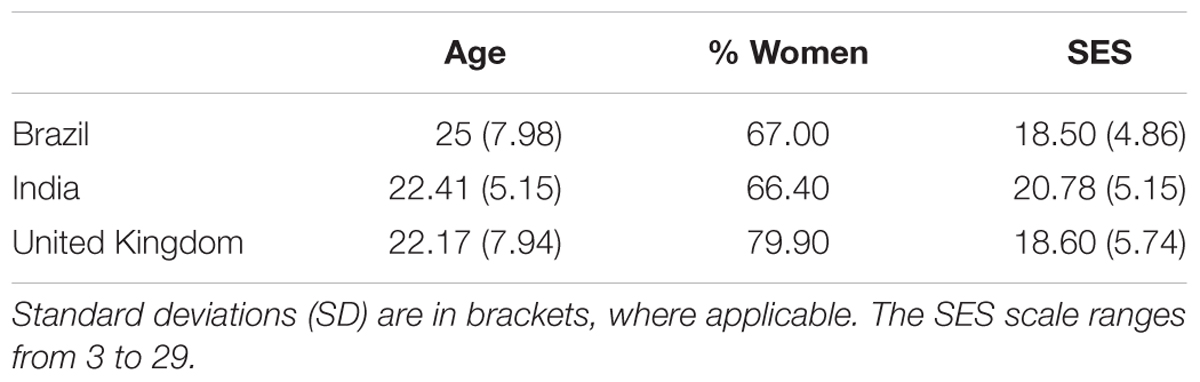

Participants in Brazil

Participants were 189 mostly postgraduate students from João Pessoa, a coastal city from north-east in Brazil. Participants were not compensated. The average socioeconomic status (SES; Sharma et al., 2012 ) of 18.50 indicates that the average participant was part of the Brazilian upper-middle class (see Table 3 for details).

Participants in India

Participants were 214 undergraduate and graduate students from Dharwad, south-west India. Participants were not compensated. The mean SES was 20.78, indicating that the average participant was part of the Indian upper-middle class (see Table 3 for details).

Participants in the United Kingdom

Of the 227 participants in the United Kingdom, 122 were psychology undergraduate students, and 105 were other members of Cardiff University (students or staff). The students received course credits in exchange for their participation, and other university members could add their name to a raffle of three cash prizes of $30, $20, and $10. The participants’ SES was similar to the SES of participants in the two other countries (Table 1 ).

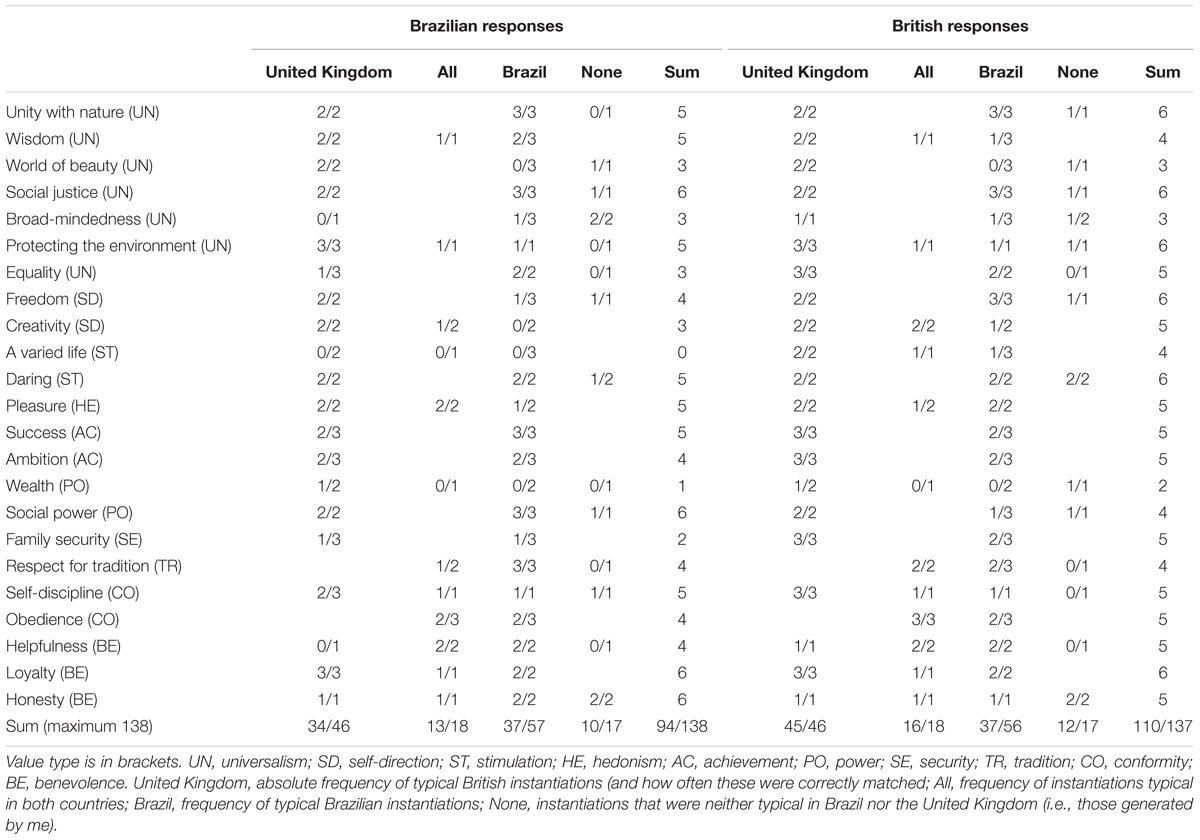

TABLE 1. Demographic details of the two samples.

The design was qualitative and entailed the use of open questions.

We examined 23 out of the 56 values of Schwartz (1992) value model (see Table 2 ). The values were selected according to their perceived relevance for explaining cross-cultural differences. That is, we expected the instantiations for the chosen values to be more varied than for some other, non-chosen values. From most value types, two values were selected. The exception was the value type universalism, for which seven values were selected, with an eye to potential future research. To measure socioeconomic status, Kuppuswamy’s Socioeconomic Scale ( Sharma et al., 2012 ) was used; it consists of three items, assessing education, occupation, and family income per month. Responses were summed up to one score. To adjust the income classes, the most recent available official income distribution from all countries was used. The questionnaire was translated to Portuguese from the original English version for the Brazilian sample by an experienced translator. The translation was double-checked by others who are fluent in both languages. The questionnaire was in English for the Indian and British samples.

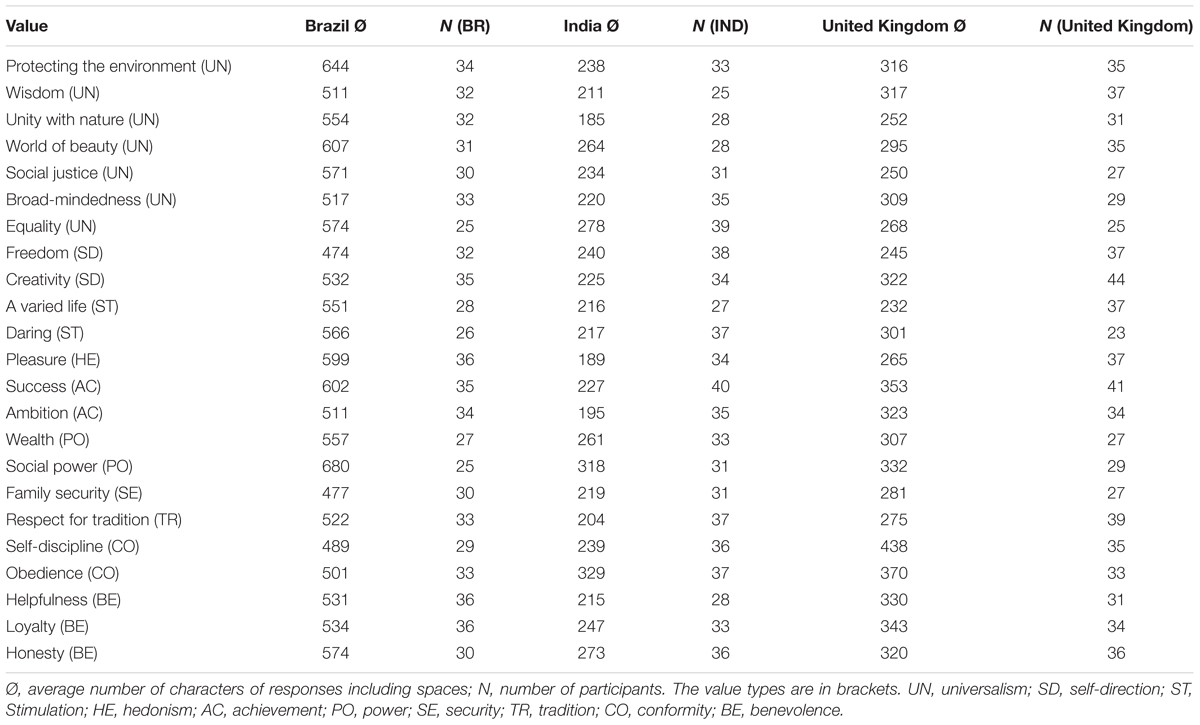

TABLE 2. Length of average responses for each value and number of participants.

Participants were asked to list typical situations in which they considered each value to be important. Furthermore, they were asked to include a “short description of the people in the situation and what they do.” The instructions provided two examples that pertained to two values not included in our measures or in Schwartz’s value model: “For example, the value ‘enjoyment’ could be relevant during leisure time. Relevant people in the situation can be friends and the family. They could spend time together at the beach or playing games at home.”

Participants were asked to list at least two to three situations, people, and actions for each value, up to a total of seven. To reduce the risk of fatigue, each participant responded to four out of the 23 values (see Table 2 for the sample size for each value), resulting in approximately 30 to 40 participants per value. Subsequently, participants completed socio-demographic items. Brazilian and British participants completed the survey online, while Indian participants used a pen-and-paper version.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed with the open access program Iramuteq, which is built on R and Python and designed for content and frequency analyzes (version 0.6 alpha 3; Ratinaud, 2009 ). The data were analyzed separately for each value and country. For all analyses, very similar words (e.g., people and person) as well as different verb forms (e.g., advice, advises, and advised) were treated as equivalent. Additionally, we grouped together certain words that seemed very similar (e.g., parents, dad/father, and mother/mum), but in general this was generally avoided because participants may have used the words in different ways even if they seemed similar to us. Furthermore, only nouns, verbs, and adjectives were analyzed.

To analyze the data, we conducted an explicit and implicit content analysis, because both the length (see Table 2 ) and the comprehensibility of the responses differed across countries. We struggled to interpret some of the responses, especially those made by Indian respondents. Therefore, an explicit content analysis seemed to be appropriate, because the meaning of a single word is usually easier to understand than the meaning of a sentence. Explicit content analysis “locates what words or phrases are explicitly in the text, or the frequency with which they occur” ( Carley, 1990 , p. 2). This analysis is straightforward and easy to reproduce, but can miss out the meaning. In contrast, an implicit content analysis aims to detect the meaning of what is said ( Carley, 1990 ). However, because the responses of British and Indian participants were much shorter than those of Brazilian participants, an implicit content analysis was difficult to produce. The British and Indian responses often consisted of only one word (e.g., “recycling” for a situation in which protecting the environment is relevant for British participants). This problem was identified after carefully reading all responses.

Next, we conducted an automated explicit content analysis with Iramuteq by counting the frequencies. We then re-read all responses which contained words that were mentioned at least by 20% of the participants to get a better understanding of the context in which the word was mentioned (i.e., implicit content analysis). The cut-off point was set to identify prospective typical instantiations, and we noted which behaviors were mentioned 10 times or more by at least five participants in one country. This threshold was selected because it enabled us to consider between 5 and 10 instantiations as candidates in each country. This procedure was not intended to definitively identify the typical instantiations, but to identify a range of instantiations that are potentially typical exemplars. In the concept mapping approach ( Lord et al., 1994 ), instantiations that are mentioned very rarely or not at all are regarded as unlikely to be core aspects of the concept, whereas frequent instantiations are seen as plausible candidates. These were then compared between the nations and considered for future study.

Finally, we re-read all responses to ensure that we had not missed any meaning or theme which was not flagged up in the frequency analysis conducted with Iramuteq, which was rarely the case. Below we report and discuss instantiations that were mentioned by at least 50% of the participants per value in each country and in the Supplementary Materials we also list 5 to 10 other instantiations per value and country that were mentioned by around 20% of the participants.

Because hardly any negations (e.g., “recycling is not relevant”) were used by Brazilian and British participants, the absolute frequencies of specific words and their connections are meaningful. Indian participants used more negations, which itself is an interesting finding, reflecting the fact that they seemed to focus more on what a value does not mean. However, we do not consider this to be an issue for the analysis, because such occurrences were still rare and they appear to have been used to express the same points as if the affirmative had been used. For example, one instantiation for the value helpfulness, “people do not come forward and rescue the victim, though they can,” was reported as an example of action antithetical to helpfulness, and was therefore judged to be equal to the hypothetical positive version (“rescue the victim”). The Brazilian instantiations were first identified by a native speaker and then translated by an experienced translator (Portuguese native speaker), who ensured that the meaning was correctly translated.

Because the three different facets of a given response – “situation,” “people in the situation,” and “what are they doing” – were all part of the instantiation, they were analyzed together. Furthermore, family, friends, and people or person were mentioned for most values at least 10 times as the “relevant people in the situation.” The value itself was also very frequently mentioned. Therefore, these responses are not informative and are not discussed further. The frequencies of these words are nevertheless listed in the Supplementary Materials.

All authors contributed to the data analysis and interpretation: The Brazilian data were analyzed and interpreted by the Brazilian authors of this paper and the authors based in the United Kingdom. The Indian data were analyzed and interpreted by the Indian authors of this paper and the authors based in the United Kingdom. The British data were analyzed and interpreted by the authors based in the United Kingdom.

Results and Discussion

The responses of the Brazilian participants for each value were on average nearly twice as long as the responses from Indian and British participants (see Table 2 ). The number of words mentioned at least 10 times barely differed between the Brazilian and the British sample. The number of words mentioned by at least 20% of the sample was lower in the Indian sample, resulting in fewer potentially typical instantiations in this sample.

Detailed analyses for each value can be found in the Supplementary Materials. There we list how often the most common instantiations of each country were mentioned and by how many participants. To address the question of whether value instantiations are more influenced by culture than values on an abstract level, we counted the number of instantiations that were mentioned by at least 50% of the participants in each country. If culture shapes how values are instantiated, people in each country should have a common understanding of values. We used 50% as an admittedly arbitrary threshold to define common understanding because of our relatively small sample sizes for each value (around 35 participants responded to each value in each country). This approach also allowed us to focus on larger effects, thus reducing the probability of a Type-I error.

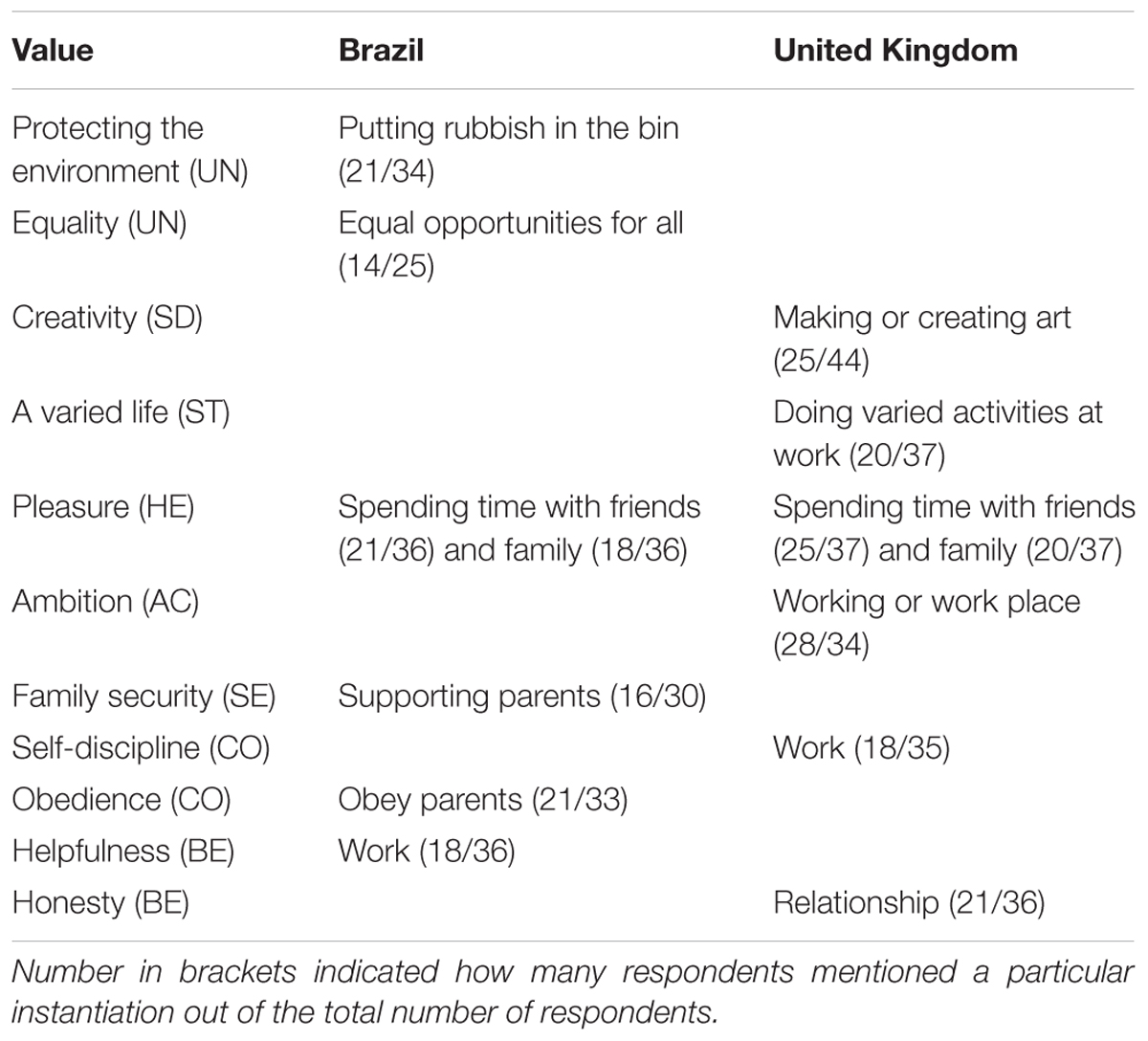

As can be seen in Table 3 , for 11 out of the 23 values, 7 instantiations mentioned by at least 50% of the participants were found in Brazil, and another 7 in the United Kingdom. For example, 50% (18 out of 36) Brazilian participants mentioned spending time with the family as an instantiation for the value ‘pleasure’ and 58% (21 out of 36) British participants considered relationships as an instantiation of ‘honesty’ (mainly in the sense that honesty is important in a relationship). In India, no instantiation was mentioned by at least 50% of the participants.

TABLE 3. Instantiations mentioned by ≥50% of the participants in each country.

In a next step, we computed the number of instantiations mentioned by at least 50% more participants in one nation than in another country. However, because the majority of all instantiations in all countries were mentioned by less than 50% of the participants, only two instantiations revealed large differences: 62% of the Brazilian participants considered throwing garbage into a bin as typical for ‘protecting the environment,’ whereas only 3% of the Indian participants did so. Also, 57% of the British participants mentioned art as a typical instantiation of ‘creativity,’ whereas only 6% of the Indian participants did so.

Finally, we looked for similar instantiations in different values across all samples. In the descriptive analyses above and the Supplementary Materials, it is easy to discern a number of instances in which participants in one nation used the same example for a different value than was used in another nation. To illustrate this diversity with only the relatively frequent examples, we list here four words which were mentioned at least 10 times for different value types. New was relevant for ambition (self-enhancement) and daring, varied life, creativity, broad-mindedness (openness and self-transcendence); support was relevant for family security (conservation) as well as loyalty (self-transcendence); and work was relevant for success and ambition (self-enhancement) and creativity (openness).

Some other examples of overlap were found in the Brazilian sample. In particular, typical instantiations of wealth in this sample often focused on a good family life, thereby overlapping wealth with family security. In addition, Brazilian participants understood social power more as social responsibility.

While Study 1 focused on the comparison of Brazil, India, and the United Kingdom, in Study 2 we focused only on Brazil and the United Kingdom. This was done because the quality of the responses of the Indian participants was overall low. This finding was surprising because some of the authors of this paper have successfully conducted multiple quantitative studies with student samples from the same departments of the Indian university with overall reliable results. This suggests that the English proficiency of most students might have been adequate for quantitative research, but not for qualitative research.

Study 2: Matching Instantiations to Values

In Study 1 we found that, although few instantiations were mentioned by more than 50% of the participants in each country, some were mentioned more frequently by participants in one country than in one or both of the other countries. Of importance, these instantiations were produced spontaneously as examples of the values. If they are valid examples of the values, then these spontaneously produced exemplars should be correctly regarded as value instantiations; that is, when presented with an exemplar, people should be able to identify the value that elicited it. More importantly, we wanted to establish whether the examples would be seen as valid even in a country in which they had not been frequently generated. Should this be the case, it would indicate that the nations differ primarily with respect to the nature of the spontaneously produced examples, but not with respect to whether the examples are regarded as valid and therefore defining of the value. In other words, such a finding would show that the concrete examples of values that spontaneously come to mind in the mental representations differ between countries, but that the abstract meaning of the values is similar enough that even examples that do not spontaneously come to mind are seen as valid instances of a given value. The aim of Study 2 was therefore to test whether instantiations can be reliably matched to the values from which they were derived.

In Brazil, 427 under- and postgraduate students (mainly in psychology), from João Pessoa participated ( M age = 23.42, SD age = 6.96, 64.60% women). They were not compensated.

British participants were 250 psychology undergraduate students ( M age = 19.32, SD age = 2.25, 89.00% women) from Cardiff University. They received course credits in exchange for their participation. Prior to data analysis, 42 non-British participants were excluded, to be consistent with the homogeneous Brazilian sample.

Material and Procedure

One-hundred thirty-eight instantiations were chosen to be matched to values, six for each of the 23 values. The instantiations were chosen mainly based on the results of Study 1, but also for exploratory purposes. The instantiations used were a priori categorized as either typical (i.e., mentioned frequently) in the United Kingdom, typical in both countries, typical in Brazil, or not typical in either country. The latter group were instantiations that we generated for exploratory purposes, based on their perceived relevance to the present research and also based on previous studies. They were used when there were fewer than six instantiations that seemed suitable in the first three categories. For example, Maio et al. (2009) found that discrimination against left-handed people is an atypical (albeit highly unacceptable) instantiation for equality for British participants. Thus, we expected that this atypical example would be recognized as an instantiation of equality by British participants and also, presumably, by Brazilian participants.

The instantiations selected from Study 1 were chosen based on the frequency with which they were mentioned in each country, while balancing the instantiations that were mentioned in both countries with those mentioned in only one country but not the other. Typical instantiations for protecting the environment, for example, were (1) “Putting certain rubbish in recycle bins rather than general waste,” (2) “Making sure the lights are off,” (3) “Walk instead of using car for short distances,” (4) “Throwing garbage in the bin,” (5) “Saving water,” and (6) “Installing heat insulation in the house.” The first three instantiations were considered as more typical by British than Brazilian participants (Study 1, see Supplementary Materials), whereas the fifth instantiation was considered more typical by Brazilian participants. The fourth instantiation was frequently mentioned by participants in both countries, and the sixth instantiation was added for exploratory purposes. Given the differences in climate between João Pessoa and Cardiff, we expected this last instantiation to be more reliably matched to the value ‘protecting the environment’ by British than by Brazilian participants. A list of all 138 (137 in the United Kingdom) instantiations can be found in the Supplementary Table S70, including the values they were derived from and whether they were mentioned by participants in both countries, just one country, or were added by us. 1

The instruction to the participants was: “Your task in this study is simple: You will be given a specific situation and you are asked to choose the most suitable value in this situation.” This was followed by an example: “Leisure time is promoted most by valuing …”. This stem was followed by six values (in the current example: success, equality, ambition, wisdom, enjoyment, and respect for tradition), and a seventh “don’t know” option. Our example then stated a possible solution: “A possible answer is the value enjoyment: Leisure time is more related to the value enjoyment than to any other value in this set.” For this example, we intentionally selected a value that is not part of Schwartz’s value model. Both the ordinal position of the ‘correct value’ 2 among the response alternatives and the five alternative values were chosen randomly. The five alternative values were a subset of the 23 values from Schwartz’s 56 values listed in Study 1. Within the six instantiations of one value, both the order and the alternatives were kept constant. The five alternative values were kept constant across both countries. All participants then completed further scales, unrelated to the present study. On average, each instantiation was matched with values by 71 Brazilian and 41 British respondents.

Brazilian participants completed a paper version of the survey in classroom settings of 10 to 40 people. British participants completed the survey online. To reduce fatigue, each participant completed only one-sixth of the items, with each participant responding to one instantiation per value.

To perform the principal analyses, we first counted how often each value was identified as being promoted by an instantiation, separately for each country (see Supplementary Table S70). Next, we compared for each instantiation and each country whether the most frequently chosen response option (whether this was a value or don’t know) was chosen significantly more often than the second-most commonly chosen option, using χ 2 -tests. This is a conservative approach, which partly takes the research design (multiple choice) and the influence of the response alternatives into account. For example, if the ‘correct’ value was chosen by 20 out of 40 British participants, another value by 12, and a third by 8 participants, we would not count it as correctly matched, because the difference between 20 and 12 is not significant, χ 2 = 2.00, p = 0.16.

Overall, in both countries, most instantiations were correctly matched with the value from which they were derived (see Supplementary Table S70). Of the 138 (137 in the United Kingdom) instantiations, 94 were correctly matched by the Brazilian participants and 110 by the British participants. This difference (94 vs. 110) did not reach statistical significance, χ 2 (1) = 0.63, p = 0.43. Indeed, the similarities were much larger: both British and Brazilian participants were significantly more likely to choose the same, ‘correct’ value 86 out of 137 times. That is, they chose the same value significantly more often than any other value (or the ‘don’t know’ response). For another 12 instantiations, no value was chosen significantly more often than the second most frequent value in both countries.

For example, the instantiation “Putting certain rubbish in recycle bins rather than general waste” was correctly identified in both countries by the majority of participants as being promoted by the value protecting the environment (54 out of 67 Brazilian participants did so and 42 out of 43 British participants). In the Brazilian sample, the number of participants who chose protecting the environment differed significantly from the number of participants who chose the second-most frequently chosen value, helpfulness (54 vs. 9, χ 2 = 32.14, p < 0.001). Overall, Brazilian participants correctly matched five out of the six instantiations for protecting the environment, and British participants correctly matched all six instantiations to protecting the environment. As can be seen in Table 4 , participants from both countries were approximately equally likely to match instantiations that had been mentioned in both countries (columns 3 and 8), mentioned more frequently in Brazil, and also the exploratory instantiations. Brazilian participants had somewhat more difficulty in matching British instantiations, compared to their British counterparts (34 vs. 45, respectively), although this difference did not reach statistical significance, χ 2 = 1.53, p = 0.22.

TABLE 4. Frequencies of correctly matched instantiations for all values combined and depending on the origin of the instantiation.

In a final step, we computed how often differences occurred based on the taxonomy proposed in Study 1, while taking the unequal sample sizes into account. We compared all values that were mentioned by at least half the participants in one country with the percentage of participants choosing the same value in the other country. We focused on differences where one option was chosen by at least 50% more of the participants in one group than the other. Fifty percent was chosen as a cut-off value because it allowed us to focus on larger effects while reducing the probability of a Type-I error. For example, if 20% of the Brazilian participants reported that they thought that a specific instantiation is best promoted by wealth, at least 70% of the British participants (a difference of 50%) needed to choose wealth before we would call it a difference. This 50% cut-off value also aligns approximately with a p -value of 0.001 of a χ 2 -test, which in our view adequately controls for multiple-comparisons.

Differences were found for five instantiations (see Supplementary Table S70): ‘Traveling’ was considered to be best promoted by the value of ‘pleasure’ in the Brazilian sample and by ‘freedom’ in the British sample (84% of the Brazilian participants chose pleasure vs. 25% of the British participants and 13% of the Brazilian participants chose freedom vs. 75% in the British sample; see Supplementary Table S70). ‘Maintaining a good work life balance’ was considered to be promoted by ‘success’ in the Brazilian sample, but not in the British sample (73% vs. 12%), whereas British participants correctly matched this instantiation to ‘a varied life’ more often than Brazilian participants did (79% vs. 6%). ‘Being able to buy organic food’ was considered to be promoted by ‘wealth’ by British participants, but not by their Brazilian counterparts (61% vs. 6%). ‘Living your own life and not following the crowd’ was considered to be promoted by ‘self-discipline’ by Brazilian participants, but not by their British counterparts (84% vs. 13%), whereas the reverse applied for the value of ‘freedom’ (1% vs. 83%). This is an interesting finding because freedom and self-discipline are thought to be motivationally incongruent ( Schwartz, 1992 ), but nevertheless appear to be related in the Brazilian respondents’ views of their social relationships. Finally, ‘customer service’ was thought to be promoted by ‘social justice’ by Brazilian participants (61% vs. 7%), whose country is one where cultural issues of corruption are relevant, but was correctly matched to ‘helpfulness’ by British participants (83% vs. 21%).

General Discussion

The aim of this research was to explore whether value instantiations vary across countries, despite there being similarities in values at an abstract level ( Fischer and Schwartz, 2011 ). We first discuss the implications and limitations of Study 1, before turning to Study 2.

Implications of Study 1